W. Bradford Littlejohn's Blog

October 26, 2014

Time to Move On...

For those who have been following this blog for a long time, or who have just stumbled upon it via a Google search, you may want to know that this blog has found a new home, bradlittlejohn.com. From now on, any new posts will appear there, not here, and I am also gradually migrating the archives from this blog—or rather, the best posts that are still worth reading—to the blog there. However, you will also find there a constantly-updated index to stuff that I'm publishing elsewhere, whether journal articles and such or online articles on other blogs.

Thanks to all those who have faithfully followed this blog for the last 4+ years; you've been a fantastic audience!

August 28, 2014

Dismissing Jesus: A Study Guide, Pts. 2-3

(See the Intro and Pt. 1 here.)

Pt. II: Special Blinders to the Way of the Cross

Ch. 9: Superficial Providence

How would you summarize Jones’s main object of criticism in this chapter?

To what extent do his critiques reflect your own experiences in Reformed or evangelical churches?

How have you used the doctrine of providence in your own life? Has it been a comfort in true adversity, or a way of complacently avoiding self-examination?

How have Christians misused the doctrine of providence in interpreting American history? Has it blinded us against a truthful examination of our nation’s history?

Ch. 10: Unconquerable Sin

How would you summarize Jones’s main object of criticism in this chapter?

To what extent do his critiques reflect your own experiences in Reformed or evangelical churches?

Jones complains that “individual sin” “gets all the attention,” thus leading us to ignore “communal sin.” Is this a fair diagnosis of our tradition? What might it mean to “deal with communal sin first, or at least at the same time” (141)?

Is it historically true that Protestantism developed this obsession with individual sin, or was Protestantism rather a response to this obsession as it appeared in the late medieval church?

Jones describes the Reformed confessions as denying the possibility of any virtue prior to conversion, and as describing us as “just as trapped by sin before as after conversion” (140). Is this an accurate description of the Reformed doctrine of total depravity?

On pp. 144-145, Jones appears to deny the doctrine of universal depravity, arguing that Scripture only describes certain wicked leaders as deprvaed sinners, and others as “trapped under the corporate domination of sin without each person needing to be utterly depraved.” Many people are “genuinely decent people” (145) who are not alienated from God. What are the implications of this view? Is this different than age-old Pelagianism?

Ch. 11: Automatic Heaven

How would you summarize Jones’s main object of criticism in this chapter?

To what extent do his critiques reflect your own experiences in Reformed or evangelical churches?

One of Jones’s concerns in this chapter is an idea of “heaven” that sees the fulfillment of so many Biblical prophecies as totally otherworldly. Is there a danger in the other direction, of insisting that they describe the “here and now” (149)

In discussing the classic problem of faith and works, Jones critiques Protestantism for separating faith as a standalone thing? However, his description of works as “the incarnation of faith” (154) is similar to classic Protestant teaching. What then is the difference between what he is saying and classic Protestantism? (Hint: see the top of p. 155)

While it certainly makes sense to say that if it does not manifest itself in works, faith is dead, Jones goes further and says that faith is “invisible,” even to God, on its own (152). This seems a problematic way of expressing the matter, to say the least. Why would Jones put things this way?

Ch. 12: God the Accuser

How would you summarize Jones’s main object of criticism in this chapter?

To what extent do his critiques reflect your own experiences in Reformed or evangelical churches?

The first full paragraph on p. 158 states neatly the larger issue at stake in this chapter, one that arose in ch. 4 as well: is Christ’s work on the cross a unique event that is the only ground of our response, or is it an example that we imitate, a beginning that we finish? Or rather, since it is clearly both in some sense, in what senses is it each? Keep this problem in mind as you reflect on this chapter.

Jones posits a disjunction between the Cross as a solution to alienation from God (penal substitution) and as a solution to the problem of death and Satan (Christus Victor), and argues that these “produce two different faiths.” Do we need to oppose these two emphases? Particularly given that death, and the dominion of Satan, are the consequences of sin and alienation from God?

Jones seems alarmed by any suggestion that we are saved from the just judgment of God. Does this idea reflect biblical language or not?

Jones worries that the language of penal substitution transforms “God into the giant Pharisee in the sky.” Likewise, he complains that it makes God “too holy to be around sinners.” Do these complaints ring true to you? Or is this sketch only possibly by isolating the “penal” from the “substitution”? That is to say, given that penal substitution teaches that God himself took upon himself the sin and the punishment, how does this make him out to be a Pharisee or too holy to touch sinners?

At the top of p. 163, Jones connects his concerns about penal substitution with the “way of the cross” themes outlined earlier in the book, arguing that in penal substitution, “the Father is first and foremost angry with the weak,” and so there is little reason to deliver the weak. Is this accurate

On p. 170, Jones argues that penal atonement theory sounds dangerously close to pagan models of appeasement. He summarizes John Stott’s three distinctions between the two models, and dismisses them as inadequate. Do you agree or disagree? (Particularly crucial is Stott’s #3: that God did not demand something or someone else, but offered himself. Jones denies this and asserts that the Father “got his child to do it,” apparently denying the unity of the Trinity.)

Isaiah 53 is crucial in any conversation about penal atonement. Jones offers a re-reading of this passage on p. 173. Read Isaiah 53 carefully and decide what you think of Jones’s reading.

How might it (or might it not) help contemporary Reformed churches to change the emphasis of their atonement theology?

Ch. 13: The Left-Right Political Distinction

How would you summarize Jones’s main object of criticism in this chapter

To what extent do his critiques reflect your own experiences in Reformed or evangelical churches

In what ways does the modern Left manifest its worship of a false God?

In what ways does the modern Right manifest its worship of a false God?

Do you find it persuasive that the failed modern political ideals stem from an inadequate grasp of the Trinity

What does Jones man when he says that to overcome the Left-Right political distinction, “we just need to imitate the community of Father, Son, and Spirit within the church”? Does the Trinity provide us with a political model? What might that mean in practice? Do you find this way of approaching the problem helpful?

How might it help today’s churches to overcome the Left/Right political distinction?

Ch. 14: Impersonal Conservatism

How would you summarize Jones’s main object of criticism in this chapter?

To what extent do his critiques reflect your own experiences in Reformed or evangelical churches?

Jones’s seems to begin by complaining that the problem with “conservatism” as a political philosophy is its empirical nature and attention to history, its refusal to be a settled ideology or set of dogmas, but then goes on to claim that it is too much of an ideology or set of “impersonal principles.” What do you think Jones is trying to say here? Do you find these complaints persuasive?

Based on the conservative thinkers surveyed in ths chapter, do you think that “conservatism” is a single coherent body of thought, or are there several different versions that each warrant distinct criticisms?

Jones draws attention to several different problems that one tends to find in “conservatism”: impersonalism, fear-mongering, individualism. In what ways have these problems infected contemporary American conservative churches?

Ch. 15: Absolute Property

How would you summarize Jones’s main object of criticism in this chapter?

To what extent do his critiques reflect your own experiences in Reformed or evangelical churches?

Reflect on ways in which the sacralization of private property dominates American political discourse and the way that Christian churches talk about charity and related issues.

Contrast the way we often think about private property in modern America with the concepts of proper ownership and use in Scripture (what it means for God to be sole owner, the Jubilee system of ancestral family ownership, the various forms of sharing built into Israel’s property law, etc.)

As in chapter 13, Jones attempts to counter our modern political problem by an appeal to the Trinity, arguing that we should approach property ownership the way that each member of the Trinity owns things vis-à-vis one another (pp. 193-94). What is Jones trying to say here? Is this clarifying or confusing? Does Jones’s language here avoid the heresy of tritheism?

If appealing to the inner life of the Trinity is not the best way to reject “absolute property,” are there other theological resources for making a similar point?

At the bottom of p. 196, Jones declares that Christians have nothing to do with worldly institutions and governments, and are supposed to let them crumble and die, so that “the church” can replace them. What would such sectarianism mean in practice? Contrast this with biblical and traditional Christian teaching on civil authority.

What are practical ways in which we can we live out a biblical view of property as intended for sharing?

Ch. 16: Nice Mammon

How would you summarize Jones’s main object of criticism in this chapter?

To what extent do his critiques reflect your own experiences in Reformed or evangelical churches?

Jones paints a disconcerting picture of economic and political realities in western capitalism on pp. 201-203. Is this a realistic portrait? How might it change the way we talked about “the market” and politics if this were true?

Modern conservatives usually dismiss any worries about inequality and poverty by saying that these depend on “zero sum thinking” and that in the real market, everyone wins. Jones argues (pp. 204-206) that this strategy ignores reality. What do you think?

Likewise, one frequently hears on the Right that talk of inequality or redistribution is based on envy. Jones counters this charge on pp. 206-208. What do you think?

Discuss Jones’s distinction of “capitalism” and “the free market” at the end of this chapter.

How do the issues in this chapter tie in with the fundamental “way of the cross” issues discussed in this book?

Ch. 17: American Mars

How would you summarize Jones’s main object of criticism in this chapter?

To what extent do his critiques reflect your own experiences in Reformed or evangelical churches?

On p. 213 Jones charges that respect for the American military for many rises to the level of “a religious devotion.” Does this description ring true? Reflect on how often Christian nations have fallen into this trap throughout history.

Does Jones’s re-narration of American military history surprise you? Which bits were most surprising? Does this change your perspective on American military action today, or is this a one-sided portrait?

In what ways does devotion to Mars undermine our Christian discipleship and witness in American churches? What benfits might a healthier sense of perspective bring?

Ch. 18: Broad Way Illusions

How would you summarize Jones’s main object of criticism in this chapter?

To what extent do his critiques reflect your own experiences in Reformed or evangelical churches?

On p. 227, Jones asks whether Jesus allows us to live “normal middle-class lives” or whether these are necessarily on the broad way which leads to destruction. What do you think he means by this? What elements of “middle class life” does he think we are called to give up?

On p. 230, Jones notes the tendency to intellectualize the “broad way” and “narrow way,” assuming that those with the hardest, least accepted doctrines are on the narrow way. Have you noticed this tendency in Reformed churches? What are its consequences?

If few find the narrow way, the “lunatic minority,” that Jones has in mind, what does this say about most churches that we find ourselves in? What does this mean for the “church” that Jones describes in such grand terms as the alternative city that is living out heaven on earth?

Pt. III: Constructing the Way of the Cross

Ch. 19: Being the Kingdom-Church

Although Jones points to one of the most radical examples of Christian charity taking institutional form, Basil of Caesarea’s Basiliad, as a model of what he wants the church to do, there still seems to be a disconnect in his rhetoric. It is one thing to call for Christians to create particular institutions for sharing and deliverance, another thing for the institutional church as such to be a “whole competing city” to all earthly institutions, something Basil never had in mind. Is this just rhetorical overreach, or what does Jones practically have in mind in this chapter—such as when he calls for churches to get involved in “manufacturing” (240)?

Does Jones want Christians to withdraw from their various occupations in businesses where they work alongside unbelievers and to create separate church-run businesses? Is this a good idea?

Does there need to be a dichotomy between Christians modeling Christlike practices and institutions in their own churches on the one hand and at the same time working for broader social and political change in their earthly occupations and communities?

Ch. 20: Getting There

What are some of Jones’s practical suggestions in this chapter for a more cross-centered church? What do you think of these? How might we go about putting some of these into practice in our own communities?

Did the tone and approach of this chapter surprise you? In many preceding chapters, one could get the impression that only immediate, uncompromising, wholesale implementation of “the way of the cross” was acceptable. But here Jones suggests a model of prudent incremental change. Are there tensions between this chapter and other parts of the book?

What do you think of Jones’s suggestion that Christians need to abandon their various occupational vocations and start doing their work “within the activities of the church”? What might this mean in practice?

Jones argues that too often our mercy ministries are “risk-free,” just sending a check thousands of miles away to poor people in Africa at a safe distance. He suggests the need to get involved in a hands-on way with nearby needs. Would this be practical in your church setting? If so, discuss how to implement such goals.

Jones suggests that churches might better live the way of the cross by creating large funds to bear one another’s medical burdens, debts, etc. Would this be practical in your church setting? If so, discuss how to implement such goals.

Jones suggests the goal of learning to live on half our incomes, and supplying the rest to the church and the needs of the community. Would this be practical in your church setting? If so, discuss how to implement such goals.

Jones concludes this chapter by reasserting that solving “the problem of evil and injustice in the world . . . [is] not the Trinity’s job. That’ the church’s job. . . . Like Christ, the church is to feed on evil and absorb it” (252). Does such a ratcheting up of the church’s mission beyond its apparent means undermine the centrality of Christ’s work or our assurance in him? Is it an invigorating challenge or a crushing burden?

Ch. 21: The Spirituality of Descent

In previous chapters, Jones has emphasized repeatedly the problems with individualism, and criticized the Protestant tendency to prioritize individual sin before communal problems can be dealt with. And yet in this chapter, he turns around to say, “we can’t hope to wrestle with Mammon in the world around us without first conquering the Mammon that has so long gripped our souls. It’s futile and pointless. Unless we exorcise the Mammon that shapes our normal habits, we will fail to overcome it in our communities” (254). Is this that different, after all, from the traditional Protestant emphasis—that evil begins in the heart, and must be rooted out there if we are to really conquer injustice on a larger scale?

Likewise, in previous chapters (notably ch. 10), Jones has critiqued the idea that we remain entangled by sin throughout our lives, even as believers. But here, he insists that “the battle between flesh and spirit is a battle Christians fight their entire lives” (258) and that we carry within us the old self of sin and the new self of the spirit. Is this really that different, after all, from Luther’s classic teaching of simul justus et peccator? And if not, why has Jones gone out of his way elsewhere in the book to critique that teaching?

The emphases in this chapter suggest that what Jones is really worried about is a theology of justification that forgets the doctrine of sanctification, a theology of forgiveness of sins that forgets our union with the indwelling Christ. Have your own church communities been characterized by these omissions? How much would it help us in addressing “way of the cross” issues to recover this balance?

At the top of p. 264, Jones declares unambiguously that without Christ’s once-for-all victory over sin, we would be “miserable and lost” unable “to break the hold of the false self on us,” and that by virtue of Christ’s work alone “we now live in a new cosmos, a new heaven and earth, promising freedom and indwelling now.” Does this stand in tension with declarations elsewhere in the book that Christ’s work is incomplete unless we carry it out, that it is our job to bring in the new heaven and earth?

Reflect on ways that the false priorities of Mammon—power, prestige, and possessions—have captured your soul, and those in your community.

What spiritual practices might you engage in to cultivate a “spirituality of descent,” overcoming the bondage of Mammon in your life and freeing you for selfless service of others?

August 25, 2014

Dismissing Jesus: A Study Guide, Intro and Pt. I

Long-time readers will recall that last year around this time I embarked on a gargantuan endeavor to offer a thorough critical review of my erstwhile teacher and mentor, Doug Jones's, long-awaited book, Dismissing Jesus: How We Evade the Way of the Cross. After seven installments and some abortive interaction from Mr. Jones, I had to abandon the project for lack of time, and repeated intentions to resume it have never come to fruition.

In lieu of a full review, then, I am offering here, in two parts, an extended set of discussion questions that I prepared for a book group this past month. In these questions, I attempt, as I did in my reviews, to capture both the positives and the negatives of the book: on the one hand, prodding readers to take the book's challenges seriously and try to apply them in our own churches, but on the other hand, critically examining the deep theological and ethical ambiguities of the book and how it might hinder, rather than help, the task of Christian discipleship. I hope these will be of service to individuals and churches as they wrestle with these important issues.

General Questions

1) How does Doug Jones understand his vocation in the book? How does this shape his rhetorical approach? In what ways is this helpful and/or harmful?

2) Although he does seek to positively outline seven pillars that make up “the Way of the Cross,” on the whole, Jones sets up his book more as a negative critique against bad models of discipleship than as a positive exposition of true discipleship (this is evident in the title itself). This being the case, what is it that Jones is critiquing? How specific is the object of criticism? Moscow? Right-wing contemporary American evangelicals? American Christianity generally? Modern Christianity generally? Protestantism? Try to find examples.

3) Are his criticisms fair, or is he resorting to straw men? Provide examples.

4) How is Scripture used in the argument? Does he build his arguments out of exegesis, or are Scriptural texts used more for illustrative or rhetorical purposes? How does he understand the relative authority of the Old and New Testaments? Hermeneutically, he privileges the sayings and actions of Jesus as interpretive keys to the rest of the biblical text (see for instance pp. 86-87). Is this problematic?

5) There is a recurrent tension in the book between the language of “inward” and “outward.” On the one hand, he will say (for instance, pp. 39, 42, pp. 240-41) that the problem with Mammon-based institutions is that they are concerned with externals and outward behavior, whereas the way of Christ is based on “an obedience of the heart, a faith of internal virtues grounded in love” (42).

Yet elsewhere, paradoxically, he will criticize traditional Protestant emphases on the inwardness of true virtue, on inward faith rather than outward behavior as the heart of Christian virtue; thus he will call for a re-prioritization of actions over words, of works over faith (pp. 46-47, 152-54). How are we to make sense of this tension?

6) Jones is fond of appealing to Jesus’ statement “Narrow is the way, and few find it.” Taken together with his insistence that we have fundamentally misunderstood the Gospel, what does this imply about the status of most American churches? Or about the spiritual status of most professing believers? Does this tend to undermine assurance of salvation? Is that a problem? Does Jones propose a way for us to gain assurance?

7) A frequent objection to arguments like Jones’s is that they rely on an “over-realized eschatology,” that is, demanding that we behave now as if Christ’s kingdom were already finally consummated, or applying Scripture passages that refer to that future time as if they described present realities. Look for some examples of this in the text. Does this pose a genuine problem? If so, what are practical problems it could generate?

8) A constant danger in the Christian tradition is the heresy of Manichaeanism, a tendency to elevate the powers of evil into a power equal and opposite to God. This manifests itself often in a dualism that treats swaths of the created order as fundamentally evil and irredeemable. Does Jones’s personification of “Mammon” fall into this trap? Is the resulting dualism evident anywhere?

9) What does Jones mean by the word “church”? What role does it play in his arguments?

See for instance:

“the church, an alternative city-kingdom here and now on earth” (5)

“a social order sufficient to itself, ultimately without the need of a civil realm” (91)

“a political body” (121), which “lives an entirely different life from the world. And because of this it aims to be more and more complete and whole and self-sufficient to itself, a real city, not dependent on or mixed [with] the world, though not out of the world.” (123; indeed, see all of pp. 121-23)

Do such descriptions refer to any real-world reality, or to a future ideal? Do they refer to individual congregations? Denominations? The church as a transnational institution? The communion of all believers in a given place?

10) Does Jones view the State as intrinsically evil, or contrary to the way of Christ? Does it have any legitimate role in society? Is this view biblical? How does it compare to traditional Christian teaching on the State?

See for instance:

“God is love, after all, but nations and empires don’t even attempt to do that. States slice and bomb. They are institutions that by their nature focus on external obedience and order. They cannot look on the heart. They do not attempt to live by love, especially not love of enemies that was so central to Jesus’s life. States excel at breaking things and people, pushing them into outward order, forcing surface conformity.” (42)

“For [Paul], those outside the church don’t fall under the jurisdiction of a conceivable Christian state or civil magistrate. They don’t fall under Christian jurisdiction at all. . . . The Corinthians had given legitimacy to pagan civil magistrates outside the church, and Paul found this scandalous. The realm outside the church was virtually nothing” (p. 90).

“The church is supposed to be able to do it all. The church has no need of an unbelieving or so-called neutral state. The church is a kingdom unto itself. Like Christ, Paul divided between God and Mammon, the church and Mammon, not Christian church-state vs. non-Christian church-state. The church is to be a fully-functioning city.” (90-91)

Contrast this to:

“Magistracy of every kind is instituted by God himself for the peace and tranquillity of the human race, and thus it should have the chief place in the world. If the magistrate is opposed to the Church, he can hinder and disturb it very much; but if he is a friend and even a member of the Church, he is a most useful and excellent member of it, who is able to benefit it greatly, and to assist it best of all.

“The chief duty of the magistrate is to secure and preserve peace and public tranquillity. Doubtless he will never do this more successfully than when he is truly God-fearing and religious; that is to say, when, according to the example of the most holy kings and princes of the people of the Lord, he promotes the preaching of the truth and sincere faith, roots out lies and all superstition, together with all impiety and idolatry, and defends the Church of God. We certainly teach that the care of religion belongs especially to the holy magistrate.

“Let him, therefore, hold the Word of God in his hands, and take care lest anything contrary to it is taught. Likewise let him govern the people entrusted to him by God with good laws made according to the Word of God, and let him keep them in discipline, duty and obedience. Let him exercise judgment by judging uprightly. Let him not respect any man's person or accept bribes. Let him protect widows, orphans and the afflicted. Let him punish and even banish criminals, impostors and barbarians. For he does not bear the sword in vain (Rom. 13:4).

“Therefore, let him draw this sword of God against all malefactors, seditious persons, thieves, murderers, oppressors, blasphemers, perjured persons, and all those whom God has commanded him to punish and even to execute. Let him suppress stubborn heretics (who are truly heretics), who do not cease to blaspheme the majesty of God and to trouble, and even to destroy the Church of God.

“And if it is necessary to preserve the safety of the people by war, let him wage war in the name of God; provided he has first sought peace by all means possible, and cannot save his people in any other way except by war. And when the magistrate does these things in faith, he serves God by those very works which are truly good, and receives a blessing from the Lord.

“We condemn the Anabaptists, who when they deny that a Christian may hold the office of a magistrate, deny also that a man may be justly put to death by the magistrate, or that the magistrate may wage war, or that oaths are to be rendered to a magistrate, and such like things.” (Second Helvetic Confession, 1566)

11) Jones frequently appeals to the Trinity as a model of Christian community or interpersonal ethics. Why is this theologically problematic?

See for instance top of p. 69, middle of p. 113, and most strikingly pp. 193-94.

Contrast to the teaching of the Athanasian Creed:

“7. Such as the Father is, such is the Son, and such is the Holy Spirit.

8. The Father uncreated, the Son uncreated, and the Holy Spirit uncreated.

9. The Father incomprehensible, the Son incomprehensible, and the Holy Spirit incomprehensible.

10. The Father eternal, the Son eternal, and the Holy Spirit eternal.

11. And yet they are not three eternals but one eternal.

12. As also there are not three uncreated nor three incomprehensible, but one uncreated and one incomprehensible.

13. So likewise the Father is almighty, the Son almighty, and the Holy Spirit almighty.

14. And yet they are not three almighties, but one almighty.

15. So the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God;

16. And yet they are not three Gods, but one God.

17. So likewise the Father is Lord, the Son Lord, and the Holy Spirit Lord;

18. And yet they are not three Lords but one Lord.

19. For like as we are compelled by the Christian verity to acknowledge every Person by himself to be God and Lord;

20. So are we forbidden by the catholic religion to say; There are three Gods or three Lords.”

Pt. I: What is the Way of the Cross?

Ch. 1: Overview of the Way of the Cross

(note: this chapter should be read alongside ch. 18, “Broad Way Illusions”)

A prominent theme here, and in the book as a whole, is the theme of “blindness,” and the corresponding contention that “Christ’s message is pretty straightforward and obvious.” Is Jones’s use of this theme helpful or harmful?

Ch. 2: The Way of Weakness

(note: this chapter should be read alongside ch. 17, “American Mars”)

What does Jones mean by “weakness”?

Do the various Biblical examples of “weakness” have any common elements? If so, what are they?

What errors is Jones trying to critique in this chapter?

What are some practical applications?

When Jones says that the wealthy and middle-class are supposed to be “second-class citizens in the kingdom,” what might this mean?

Ch. 3: The Way of Renunciation

(note: this chapter should be read alongside ch. 16, “Nice Mammon”)

What does Jones mean by “renunciation”?

What errors is Jones trying to critique in this chapter?

What are some practical applications?

This is one place where some of the concerns about Manichaeanism might crop up. Jones treats many structures and areas of earthly life as being completely under the dominion of “Mammon.” Does this mean Christians must withdraw from these altogether, seek to destroy them, or seek to win them back to the Lordship of Christ (see pp. 41-42)?

This is also a chapter where we see the language of “inward” and “outward” cropping up. Jones complains that the “outward” is the domain of Mammon. Does this imply that Christian renunciation consists in a reorientation of inward attitudes, overcoming our clingy dependence on material goods? Or does it imply that Christian renunciation consists in outward renunciation?

Ch. 4: The Way of Deliverance

(note: this chapter should be read alongside chs. 10-12)

What does Jones mean by “deliverance”?

What errors is Jones trying to critique in this chapter?

What are some practical applications?

Is it significant that Jones describes the way of deliverance as part of “the way of the Cross”? It makes sense for “weakness” and “renunciation” to be part of taking up one’s cross, but should “deliverance” have such a negative orientation? Does this have any practical ramifications?

Is our work of deliverance a response to Christ’s work of deliverance, or part of it, a continuation of it? What are the theological and pastoral implications of this?

A prominent theme in this chapter is the opposition of “words” and “actions”, of “believing” and “doing.” What is Jones trying to accomplish with this? Is this a biblical emphasis?

Ch. 5: The Way of Sharing

(note: this chapter should be read alongside ch. 15, “Absolute Property”)

What does Jones mean by “sharing”?

What errors is Jones trying to critique in this chapter?

What are some practical applications?

As above with “Deliverance,” does it help or hurt Jones’s agenda to describe “sharing” under the negative heading of “the way of the cross”?

The different biblical passages that Jones draws on here seem to point toward several different practical applications—holding one’s property in a generous way, renouncing property altogether, giving away “half,” etc. Which of these, if any, is Jones trying to point us to?

Ch. 6: The Way of Enemy Love

(note: this chapter should be read alongside ch. 17, “American Mars”)

What does Jones mean by “enemy love”?

What errors is Jones trying to critique in this chapter?

What are some practical applications?

Are Jones’s representations of traditional Christian views on enemy love fair? (see pp. 75-78)

What does Jones mean by the word “violence” in this chapter? What does the word mean in the string of biblical references he gives on pp. 80-81? Does this support or undermine the way he is using it?

What sort of eschatology underlies Jones’s vision in this chapter?

Jones say he is not pacifist? Why not? What is he then, and how does this differ from traditional Christian views?

Ch. 7: The Way of Foolishness

(note: this chapter should be read alongside ch. 11, “Automatic Heaven”)

What does Jones mean by “foolishness”?

What errors is Jones trying to critique in this chapter?

What are some practical applications?

Is Jones’s description of Protestant doctrines of faith (pp. 99-100) fair and accurate?

What is Jones trying to accomplish with his redefinition of “faith”? How different is this from what Luther was trying to accomplish?

If we emphasize that “the Gospel is foolishness,” how do we avoid the converse, “foolishness is the Gospel”? That is, how do we know when it is legitimate to criticize things for being irrational, if faith should lead us to expect the truth to be irrational or counterintuitive?

Ch. 8: The Way of Community

(note: this chapter should be read alongside ch. 10, “Unconquerable Sin”)

What does Jones mean by “community”?

What errors is Jones trying to critique in this chapter?

What are some practical applications?

Jones critiques traditional Protestant ideas of salvation as being “selfish” (114-16). Is this a fair and accurate critique?

Jones sets up an opposition in this chapter between the “individual” and “social”/“communal,” and says that we need to emphasize the latter more than the former, that the individual needs to “take second place” (117). What does this mean, concretely? How might this change our theology and practice?

This chapter rests a great deal of weight on the concept of the “church,” and the church as the “kingdom.” This raises important questions about what Jones means by the concept “church” (see general question #9 above) and what eschatology governs his application of it (see general question #7 above).

July 28, 2014

Remembering the Great and Holy War, 1914-1918

One hundred years ago today marked the onset of what was then known only as “The Great War.” As Philip Jenkins’ new book The Great and Holy War shows, however, perhaps we ought still to dignify it with that awful title. Although WWII looms vastly larger in our cultural consciousness, this is due partly to its greater proximity in time, and to the much greater role that America played in the hostilities. Yet most people would be surprised to learn that the bloodiest battle in US military history remains the Battle of Meuse-Argonne, which took place over the final 47 days of WWI, in which 26,277 perished. And the toll suffered by US troops is immeasurably dwarfed by that of the European nations. Jenkins puts things in perspective for us:

“The full horror of the war was obvious in its opening weeks. . . . On one single day, August 22, the French lost twenty-seven thousand men killed in battles in the Ardennes and at Charleroi, in what became known as the Battle of the Frontiers. . . . To put these casualty figures in context, the French suffered more fatalities on that one sultry day than U.S. forces lost in the two 1945 battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa combined, although these later engagements were spread over a period of four months. One single August day cost half as many lives as the United States lost in the whole Vietnam War.

During August and September 1914, four hundred thousand French soldiers perished, and already by year’s end, the war had in all claimed two million lives on both sides. The former chapel of the elite French military academy of Saint-Cyr systematically listed its dead for various wars, but for 1914 it offered only one brief entry: ‘The Class of 1914”—all of it.” (pp. 29-31)

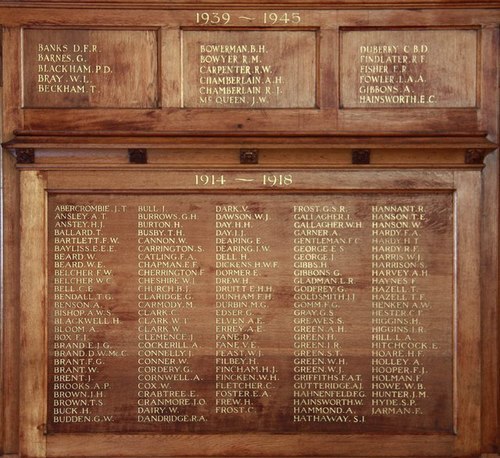

Britain lost 1.75% of its pre-war population to military deaths alone, not to mention the hundreds of thousands maimed for life; Germany, 3%; France, 3.5%. The Western Front of WWI would claim ten times as many lives as the Western Front of WWII, a statistic borne out by the somber lists of names that can be found in any parish church in Britain. Given that Europe in 1914 was the unquestioned leader of world civilization, and still the center of global Christianity, such trauma could not fail to reshape the course of world religion as well as politics, remaking the world order more comprehensively even than its more global successor, WWII, could do. It is this cataclysmic shift, in all its varied manifestations, that Jenkins seeks to chronicle in The Great and Holy War.

This book is extraordinarily wide-ranging, even by the standards of Jenkins’ impressive oeuvre thus far, and is difficult to summarize neatly. This is in part due to the sense one gets that Jenkins was working to a deadline (the centenary of World War One) and hence lacked the time to fully organize the immense array of material his research had assembled. The book thus perhaps lacks at some points the clear focus and compelling readability that has characterized much of Jenkins’ other work, though it remains a fascinating read, and one hopes any such handicaps will not prevent readers from engaging with its remarkable insights and theses.

The title of the book declares Jenkins’ most remarkable thesis: that the Great War, what we often consider the pinnacle of cynical nationalistic realpolitik, was perceived at the time as a deeply religious conflict, indeed, a “holy war,” by all the combatants. Such a thesis strikes deeply at the roots of much modern secularization theory, which sees the de-Christianization of Europe as a long gradual process set in motion by science, the Enlightenment, and modern industry, a process very far underway by the 20th century. On the contrary, shows Jenkins, Europe in 1914 was still steeped in religion, perhaps as much as at any point in its history—mostly Christianity of course, but even freethinkers and secularists were more likely than not to follow strange alternative religions like Theosophy, and to dabble in the occult. Against the traditional narrative, Jenkins concludes his book with a new theory of religious development that he calls “punctuated equilibrium,” echoing the leading current view in evolutionary science: long periods of relative stasis (such as 1815-1914) followed by short periods of cataclysmic change (such as 1914-1918). Jenkins’ thesis undermines any claim to comfortable self-assurance on the part of the modern West that technological and political progress necessarily leads to a cool scientific rationality; on the contrary, the years of the Great War were a time of superstitition, apocalypticism, and mass hysteria in all the combatant nations.

However, Jenkins’ thesis also strikes deeply at any comfortable self-assurance on the part of western Christians: we like to think that our religion has long been a force for peace in the world, or at worst, essentially disengaged from the secular rationality that drives global conflict; Islam, on the other hand, is a primitive and violent religion that seeks to discern the divine will in every historical incident and to pursue expansion by merciless jihad, or “holy war.” Jenkins neatly inverts this narrative: “enlightened” western Christianity was responsible for some of the most shocking rhetoric of holy war that we can imagine, at a time when global Islam was diffuse and relatively passive and apolitical; the events of World War One, in fact, set in motion the radicalization of Islam and its current appetite for “holy war” thinking. A few quotations will illustrate just how fully and frighteningly “holy war” rhetoric took hold in 1914 Christendom:

“It’s not a saint or a bishop, it’s Our Lady herself, it’s the Mother of God-made-Man for us, who endures the violence and the fire. She’s the one we saw burning at the center of our lines, like the virgin of Rouen once upon a time, She’s the one they’re trying to slaughter, the old Mother, the one who gives us her body as a rampart. At the center of our lines, she’s the one who stands as the rampart and the flag against Black Luther’s dark hordes.” —Paul Claudel, La Nuit de Noël de 1914

“Kill Germans—do kill them; not for the sake of killing, but to save the world, to kill the good as well as the bad, to kill the young as well as the old, to kill those who have shown kindness to our wounded as well as those fiends. . . . As I have said a thousand times, I look upon it as a war for purity, I look upon everyone who died in it as a martyr.” —Rt. Rev. Arthur Winnington-Ingram, Bishop of London

“It is God who has summoned us to this war. It is his war we are fighting. . . . This conflict is indeed a crusade. The greatest in history—the holiest. It is in the profoundest and truest sense a Holy War. . . . Yes, it is Christ, the King of Righteousness, who calls us to grapple in deadly strife with this unholy and blasphemous power." —Rev. Randolph McKim, Rector of Church of the Epiphany, Washington, DC

“There is not an opportunity to deal death to the enemy that [Jesus] would shirk from or delay in seizing! He would take bayonet and grenade and bomb and rifle.” —Albert Dieffenbach, American Unitarian pastor (of German heritage!)

“Our Father, from the height of heaven, make haste to succor thy German people. Help us in the holy war, let your name, like a star, guide us: lead Thy German Reich to glorious victories. . . . Smite the foe each day, with death and tenfold woes. In thy merciful patience, forgive each bullet and each blow that misses its mark. Lead us not into the temptation of letting our wrath be too gentle in carrying out Thy divine judgment. . . . Thine is the kingdom, the German land. May we, through Thy mailed hand come to power and glory.” —Rev. Dietrich Vorwerk (German pastor), Hurrah and Hallelujah

As this last quote suggests, German Protestants were perhaps the most extreme in such blasphemous rhetoric (so that their defeat seems indeed like an act of divine judgment), but they were scarcely to be outdone by any of the combatant powers. Indeed, similar language and pervasive attitudes could be found in Orthodox Russia, Catholic Italy, etc., as Jenkins shows. Liberals and conservatives, clergy and laymen, educated and uneducated, established and disestablished churches, Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox alike participated in the crusading mood of the time (though a few prominent leaders, such as Abp. of Canterbury William Temple, and Pope Benedict XV, stand apart as noble exceptions). If there is anything for modern Christians to take comfort in, it is that at least contemporary examples of Christian nationalism, which many of us have so lamented, pale in comparison to anything a century ago; we have perhaps learned a few lessons.

The story Jenkins recounts does not neatly fit any of the leading narratives of secularism or modernity-criticism. The “secular nationalism causes violence” narrative of William Cavanaugh and company is as thoroughly contravened as the “religion causes violence” thesis that he seeks to overturn. (Also, it should be noted, simplistic Catholic attempts to pin nationalistic violence on Protestantism per se, or Anabaptist attempts to pin it on church establishment per se, just do not fit the evidence). On the one hand, it seems clear that for all the appalling Christian baptism of violence that the Great War witnessed, Christian convictions could hardly have caused the war, given the patchwork of religious allegiances represented among its combatants: Lutheran, Calvinist, and Catholic Germany allied with Catholic Austria-Hungary, Eastern Orthodox Bulgaria and the Muslim (!) Ottoman Empire against Orthodox Russia, secular/Catholic France, Catholic Italy, Protestant Britain, and secular/Protestant/Catholic America. Indeed, it is a testament to the incredible power of self-deception in wartime that any of the combatants could have plausibly narrated their struggle as a sectarian one (i.e., in the first in the sequence of bloc quotations above, the French managed to portray their struggle as one against “black Luther’s dark hordes” despite the fact that their leading ally, Great Britain, was staunchly Protestant). This, together with the fact that non-Christian minorities (notably Jews) in the various nations enthusiastically supported each national cause, suggests that idolatrous nationalism, rather than any genuine Christian conviction, was the real motivating force behind the war. And yet at the same time, it is important to note that most of the “holy war” rhetoric, far from being stoked by cynical political leaders, was carefully disclaimed and even in cases systematically censored by many of them, especially the British. On the whole, while the impetus for the conflict itself may have come from the politicians, the impetus for its sacralization came straight from the churches.

Against any simplistic attempts to trace the relation of “religion” or “nationalism” or “secularism” to violence, then, Jenkins’ narrative invites us to see just how slippery these terms are, how inextricable they become in the actual heat of conflict. But inasmuch as we might venture a thesis, it might be this: although violent conflict itself usually stems from worldly causes, it is human nature to imbue such conflicts with other-worldly significance, thus intensifying them. In short, religion, unfortunately including Christianity serves as a means of explaining and legitimating violence, regardless of the original grounds of that violence (or of the logical coherence of the religious explanation). Of course, the word explaining is key here; it should not surprise us at all that in times of almost inconceivable suffering and trauma, people should reach out for any explanation that can try to make sense of the enormity of events, and often only supernatural explanations are equal to the task. As Jenkins says, immediately following the passage quoted above about the scale of the human cost in the war’s opening months, “Confronted with such horrors, it would be amazing if contemporaries had not believed they were entering some apocalyptic era. How could anyone understand such hideous numbers except in supernatural terms?” (31)

Of course, there is much more that might be said of Jenkins’ book. In a nutshell, he attempts to explain how so much of the world as we know it today, both politically and religiously, was a product of those tumultuous four years. The crucible of war destroyed ancient empires and launched fledgling modern democracies or else dictatorships, it forged the Soviet communism that would drive so much of 20th century history, and laid the foundation for Nazism and all its horrors (as Jenkins chillingly comments at one point, “of necessity, messianic nations must have Satanic foes”; for humiliated Germany, the failure of such a grand messianic vocation could only be explained by a scapegoating of correspondingly Satanic dimensions). For other nations, such as Britain, the disillusionment with the “holy war” mood of the Great War, rather than being re-cast in purely nationalistic terms, led to a rapid secularization of the public square and a general decline in religious commitment. In the Third World, meanwhile, the events of the war stirred explosive religious growth, both Christian and Muslim, including apocalyptic forms of faith that Europe was now trying to leave behind. For Jews, the war helped launch the Zionist movement, which together with the post-war revival of Islamic fundamentalism, drives so much geopolitics today.

No doubt, in a book so wide-ranging, there are numerous details that specialist scholars in various fields might dispute, and many points that call for elaboration. But the overall lessons for today are clear enough. For one, Christians in the West today have much to repent for, and need to think twice before so casually demonizing the jihadist Islam which they helped created in their own image a century ago. For another, history can change quickly and dramatically; our future will not necessarily resemble our past anymore than the future of Europe in 1914 would resemble its long Hundred Years’ Peace. And yet out of these changes, however disastrous at the time, God often achieves remarkable renewals of his church. Jenkins’ conclusion is an invitation to be alert and ready for whatever mighty works both the forces of evil and the Lord might have in store in the decades to come:

“In religion, as in politics and culture, we should see the pace of change not as steady, gradual evolution but as what biologists call punctuated equilibrium—long periods of relative stasis and stability interrupted by rare but very fast-moving moments of revolutionary or cataclysmic transformation. These radical innovations then take decades or centuries for the mainstream to absorb fully, until they are in their turn overthrown by a new wave of turmoil. . . . Might another such realignment occur at some future point, a new moment of tectonic faith, with all that implies for innovation and transformation? . . . When we trace the southward movement of Christianity, we also see faith becoming synonymous with the most volatile and ecologically threatened area of the world. . . . Catastrophe might once more precipitate a worldwide religious transformation.” (pp. 375-76)

July 25, 2014

Private Property, Aquinas, and Legal Realism

Earlier this week, two leading Catholic political bloggers, Elizabeth Stoker Bruenig and Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry (better known as Pegobry, or just PEG), engaged in a short but sharp exchange on one of my favorite subjects, property rights (see here, here, here, and here). Although I can hardly claim to be an expert on the subject, I’ve long lamented the absence of substantive discourse on the subject among political theologians and Christian ethicists, so Liz Bruenig’s recent attempts to foreground the issue have been a breath of fresh air. Pegobry, however, raised some rather important questions, or at the very least the sorts of questions that most conservatives are likely to raise, and given the frequency with which I encounter such questions, I think they deserve to be explored a bit further than they were in the inconclusive interchange.

So although I am told that a day is as a thousand years on the internet and a four-day-old discussion is too stale to bother resurrecting, I will venture some reflections of my own.

First, though, a bit of quick review for those of you just joining us. Liz Bruenig kicked things off with a little discussion of St. Augustine (of whom she is a fan and perhaps something of an expert) and legal realism, which is to say the idea that property rights are nothing more than creations of the law, and thus in principle alterable at the law’s discretion. The context for Augustine’s affirmation of legal realism that she identified was, unhappily, one of his anti-Donatist writings, in which he dismissed their complaint against the state’s confiscation of their property. She notes that Augustine was somewhat prescient here in rejecting Lockean “labor-desert” theory, which is to say the idea that property rights are created and become morally binding as the just fruits of labor. Pegobry objected, perhaps unsurprisingly, that this is precisely why conservatives object to anything like “legal realism” and insist that property rights are “sacred” and must be respected by the state, and not tampered with—legal realism encourages and justifies abominations like arbitrary state confiscation of property from people it doesn’t like. To this Ms. Bruenig replied that of course the state often does terrible and unjust things with its power to define property rights, but the fact that you don’t like that power doesn’t make it untrue. Legal realism is merely a descriptive account of how property rights are in fact generated, not a normative account of how they are generated, and the simple fact of the matter is that without the state’s determination to prevent me from taking your computer for my own purposes, your ownership of it is meaningless.

At this point Pegobry complained that Ms. Bruenig had now defined legal realism so minimalistically as to be useless. If all it means is that laws are, well, laws, and determine what will and won’t be enforced, then so what? By the same token, one could note that descriptively, the state’s determination of what counts as human life worthy of protection (slaves? the unborn? infants?) does in fact determine who gets protection, and thus perhaps who may end up dying, and thus in this somewhat perverse sense “rights to life” are generated by law. But of course the important question at hand, he insisted, is whether the law is acting rightly, which is to say whether in its legal determinations it is respecting pre-existing moral rights and duties that need to be honored. Accordingly, Pegobry challenged Ms. Bruenig to clarify whether on her view there were such moral restraints in the case of property, whether she would have any principled objection to “a total redistribution of property.” Ms. Bruenig’s response (in an addendum to her previous response) to these challenges was probably not fully satisfactory to many readers. As far as pre-existing moral constraints that should normatively guide property law, she briefly pointed back to Augustine’s view of God’s ordination of creation (which He alone truly owns) for the common use of all. The question about redistribution she dodged somewhat by saying “If a Christian community wanted to live in this way, communally, that would be fine.” This sounds like a harmonious mutual decision, like the community in Acts 4, rather than a top-down legal imposition, which is what Pegobry worries about. She concludes by explaining that the main purpose of legal realism in these discussions is simply to parry the common libertarian talking-point that taxes are a form of theft, or at least redistributive taxes are. That is certainly an assertion I have sought to debunk a number of times myself, but I wonder if Ms. Bruenig is right that it can be dismissed with a merely descriptive theory; while not technically theft, taxes or other property arrangements that are unjust might fairly be described as *like* theft.

So I take it that, at the end of this brief exchange, the fundamental conservative worries were not answered as clearly and fully as they need to be. So let me first restate those objections as clearly as possible, then attempt to clarify why at least Pegobry’s statement of them fails (though this does not mean that, suitably nuanced, the line of objection might not be more compelling, though that will mostly be a subject for another post).

The objection, then, from an intelligent conservative who avoids some of the more naïve ideas about private property rights, would run something like this:

To be sure property rights, as binding and enforceable social arrangements, depend on law. Indeed, in various areas such as intellectual property, it is difficult to see how such rights could be given any generally-agreed upon content without being created by law. However, law ought to be moral, not arbitrary. And to be moral, law ought to serve not merely utilitarian ends, doing whatever works best for the greatest number, but principles of justice, which limit in advance the range of fair and acceptable actions the law may undertake. (Never mind for now whether we construe these principles as some form of ‘natural law’ or another source of moral authority.) This is why the law cannot simply decree the death of an innocent person to satisfy the whims of a majority. This is why, to pick a more contentious example, many Christians will argue that the law cannot grant “marriage” to anyone who wants it, regardless of whether they fit the criteria for the institution. (Indeed, marriage law represents an interesting analogy on several levels to property law, inasmuch as much of what gives it its distinctive shape in particular societies, and what makes it meaningful and binding, is provided by law; but we do not thereby reduce it wholly to a creature of law.)

To be sure property is not like life; we do not come into the world with it, nor is there any natural way simply to unite it to ourselves. Nonetheless, the principles for its distribution cannot be wholly arbitrary, and they ought to have something to do with desert. In determining just property relations, states must have an eye to considerations like: who already has it (de facto)? Have they done anything to deserve having it taken away? Who has worked hard for it, and who has merely passively reaped the benefit of another’s labor? (Of course, it does not follow that the consistent application of such principles will necessarily favor the traditional property-owning class; quite the contrary.) Each generation does not have a clean slate with which they can say, “OK, who do we want to give this stuff to? Let’s redistribute it as follows…”

This, I take it, is the substance of Pegobry’s objection—if I may say so myself, a better-stated version than he himself provided. A closer look at Pegobry’s claims will, I hope, make clearer just what this sort of objection needs to deal with in order to get properly off the ground.

First, a historical point. Pegobry frankly admits his own unfamiliarity with Augustine; I am sorry to say that I am little better off myself. This is one of the reasons I am very glad that Ms. Bruenig is doing so much to disseminate a better understanding of his political thought. Unfortunately, however, Pegobry implies that, whatever Augustine may have thought regarding property and legal realism, we would do well to disregard it in favor of the medieval and post-medieval Catholic teaching on the subject:

“I find myself much more at home with what I take to be the ‘generic’ Catholic understanding, heavily influenced by Scholasticism, of private property as a kind of God-granted stewardship, which issues in both a natural right of private property and a moral duty to use this faculty in accord with the will of God.”

Presumably, in declaring himself “at home with” this understanding, Pegobry means to imply that he is quite familiar with it. And yet I must confess I am not at all sure he knows what he’s talking about. Indeed, the appeal to a “‘generic’ understanding,” with a vague nod in the direction of “Scholasticism” (isn’t Scholasticism always involved in these things, one way or another), does little to instill confidence. The first thing to say here is that there is not really a “generic” understanding—that is rarely so in the history of thought. Rather, you have the common Patristic view that private property is a dubious product of the Fall,[1] which Christian communities ought to strive to transcend (Augustine is of course somewhat more pessimistic and “realist” on this point), then in the High and late Middle Ages, ferocious conflict (including real-world conflict) between the modified-Aristotelian Thomist view, the radical-Patristic Franciscan view, and a sort of proto-modern papalist view,[2] with diversity increasing as we move into modernity. Even the papal encyclicals that undergird Catholic Social Teaching do not speak with one voice on the subject. Rerum Novarum is notoriously influenced by Lockean ideas, but later encyclicals have moved away from this.[3] All of this to say that we need thorough and thoughtful wrestling with these issues nowadays, rather than blithe reassurances that there is some basic common-sense view that surely every sane person must share and that more or less settles the issue.

However, to the extent that we could speak of a “‘generic’ Catholic understanding” it would have to be that of Thomas Aquinas, whose synthesis was enormously influential on succeeding centuries and is generally given at least lipservice in Catholic treatments of the subject today, even when it is not carefully attended to. Indeed, I would hazard the claim that properly understood, the Thomist view could be taken as a rough consensus statement for most serious Christian reflection on property through the centuries.

Space cannot permit anything like a full statement of Thomas’s doctrine here, but I will say enough to try to show the nub of the problem with Pegobry’s formulation, a problem which affects his whole line of argument. He is right to highlight the theme of “God-granted stewardship” in the Thomistic understanding of private property, but just what does he mean when he says that it “issues in … a natural right of private property”? That, after all, is what this whole discussion is really about: is there such a thing, and whence does it arise?

Thomas, actually, is really not all that opaque on the question. He offers a rather clear distinction between use (usum) and administration (potestas procurandi et dispensandi). This generates two distinct sets of rights. First is the right of humankind to take, use, and enjoy the fruits of the earth. This is a natural right in the fullest sense of the term—pure and simple, everyone is born into the world with the right to take some fruit off a fruit tree if they’re hungry, just as they’re born free to speak, marry, etc. But of course, this right is common and universal, and so is not really what we would call a property right; in fact, it is kind of the opposite.[4] It is what we could call a pre-political right, and can of course be modified some by subsequent arrangements, but is always there in the backdrop (so that Aquinas contends that in cases of necessity—if you really need that apple or that loaf of bread—this natural right reasserts itself and trumps all others).

The second is the institution of property rights, whether private or public.[5] This is where Aquinas parts company somewhat from many of the Fathers. Whereas they asserted the primordial right of common use, and judged that only sin could account for compromising such a thing with the distinction between meum and teum, Aquinas was more Aristotelian. Even without sin, property rights might be a good and useful thing, although perhaps only sin made them necessary (this is one point where Aquinas could be a bit more clear). This was because, he deemed, a distinction between who administered what could actually help further the original natural right of common use—that is to say, by avoiding confusion and promoting a sense of personal responsibility (to use an unfortunately now-hackneyed term), property rights could actually help more effectively bring the fruits of the earth into general circulation. Thus, Aquinas could speak of property rights in this sense as natural in the sense of being not contrary to nature, or even in accord with nature, but they were not natural in the fullest sense, because they were not spontaneously present in nature, but “derivatory and secondary” (in the words of Anthony Parel), arising out of subsequent human arrangements. Conversely, although common ownership is natural in the sense that it comes first and supplies the backdrop for future ownership arrangements, it is not natural in the sense that the natural law

“dictates that all things should be possessed in common and that nothing should be possessed as one’s own, but because the division of possessions is not according to natural right, but, rather, according to human agreement, which belongs to positive right, as stated above. Hence the ownership of possessions is not contrary to natural right; rather, it is an addition to natural right derived by human reason.”[6]

Derived by human reason. According to human agreement. As John Finnis summarizes,

“The moral or juridical relationships to such an entity that we call property rights are relationships to other people. They are matters of interpersonal justice. Arguments for founding property rights on alleged ‘metaphysical’ relationships between persons and the things with which they have ‘mixed their labour’, or to which craftsmen have ‘extended their personality’, are foreign to Aquinas.[7]”

Thus Aquinas, too, is among the legal realists. “Your list of allies grows thin,” Elrond might say to Pegobry.

This will afford us some of the needed clarity to sort through some of Pegobry’s other comments. He does not seem clear on why it is that property rights should be subject to “legal realism” in a way any different from other rights that we hold dear. For instance, he describes Ms. Bruenig’s position as “the position that human beings have no intrinsic rights (at least in the domain of property, although why this should be true about property and not other rights is unclear) that human institutions and laws are bound by higher laws to respect, and that such rights are “totally” fictitious creations of the sovereign.” Later he uses the analogy of the right to life, and the state’s responsibility to protect it, and he also appeals to “the declaration of the Ecumenical Council of Vatican II that every human being, as an image-bearer of God, has transcendent dignity, one consequence of which is the existence of natural rights that human institutions are bound by divine law to respect.” He also asks,

“is it correct to say that people have a right to private property in the same way that we say they have a right to speak freely, or assemble peaceably, or any of those rights the recognition of which we typically take to be a mark of civilization? That is to say, rights, that (conceptually rather than historically) ‘preexist’ the state in the sense that the state is duty-bound to respect them not on grounds of expediency but on grounds of higher law.”

This is slippery stuff. In particular, one worries about the invocation of “those rights the recognition of which we typically take to be a mark of civilization,” given the way in which human rights discourse has been used in increasingly imperialistic fashion by national and international authorities. But leaving those aside, what about the specific rights here asserted—life, liberty of speech, liberty of assembly? All of these we might quite justly associate with the “transcendent dignity” that we have as “image-bearers of God,” because they all seem to essential to a basic realization of our human nature. Obviously we were born into the world for the purpose of living, and without that right we have no others. And rational thought, and speech to share that thought, are essential to what it means to be human. Likewise, as fundamentally social animals, we must be able to assemble together with others in pursuit of common ends. For the state to legislate against such rights in general would indeed be intrinsically unjust, a violation of natural rights, because such rights arise not out of means to an end, but as part of the end of being human.

But is there anything equivalent in the neighborhood of property rights? Well only, it would appear, in the domain of common use. This, Aquinas is clear, is a fundamental right of being human, because without it, without the power to appropriate to our use such fruits of the earth as we need for health and flourishing, we could not live at all. And thus it is the case that there are natural, intrinsic, pre-political rights pertaining to the “transcendent dignity” of human beings as image-bearers which states are bound, as a matter of principle, to respect. The problem is they are not the rights of existing de facto property owners, or would-be Lockean property-acquirers, but rights prior to these, which will condition and limit these.[8] This, presumably, is what Ms. Bruenig is up to when she explains that the normative feature in the property picture is to “make sure the poor are supported.” (While she follows this with, “Because Christ commands it,” it is clear more generally from her exposition of Augustine that it is because God created the world and intends it for the use of all, as Aquinas also argued.)

Thus, to Pegobry’s insistent question as to whether, according to Ms. Bruenig, “under correct Christian ethics, all property is contingent and rights of property . . . have only instrumental and not intrinsic value,” it must be answered, in Thomistic terms at least, “Yes, instrumental to the service of the common use of humankind.” Indeed, it is difficult to conceive, within such a framework, of just what sort of “intrinsic value” such rights could have.

However, this is not to say that Pegobry’s worries are entirely unreasonable. In fact, the quest to identify an “intrinsic value” to private property ownership, more directly rooted in human nature, is not necessarily a fool’s errand. For instance, we might well argue that the fundamental value of human freedom requires a certain self-sufficiency which requires, or at least is best secured by, property rights. Or with a bit more sophistication, we might say that freedom in fact requires responsibility to be truly realized, or in more Scriptural terms, that taking dominion and exercising stewardship is part of what it means to bear God’s image, and thus something like private property ownership is naturally necessary for human beings, and must be protected by law as a pre-political right. Hegel and Hilaire Belloc are two have offered something like this sort of reasoning. The problem, as Jeremy Waldron has masterfully shown in The Right to Private Property, is that these arguments as well argue for a re-distribution of property, indeed, more dramatically so than the Thomist—they compel the conclusion that property is something that everyone should have, not merely enough for sustenance, but for freedom and self-realization.

What we really would need, then, is an argument that the fruit of labor must not be separated from the labor, that just as the children that one brings into the world, are, by natural right, your children, not the state’s to do with as it wishes, so the products that you create or enrich by your labor are justly yours. Of course, the analogy conceals the fact that the products of labor just don’t seem to have a metaphysical relationship to labor in the way that children do to conception (not to mention the fact that in laboring, one must make use of much more pre-existing material). Unless a convincing metaphysical argument can be brought, then (and while I am not wholly dismissive of the attempt, most existing attempts have been quite unsatisfactory), then the analogy really falls back on some version of desert theory. There are of course very substantial problems with building a property distribution on desert theory, as not merely Liz, but Matt Bruenig has argued. However, this does not mean that relative assessments of desert cannot and should not play any role in legal determinations of just property relations. It is this intuition—that it would be unjust for the law to suddenly deprive me of something I have worked hard for (assumign I’ve worked justly) even for good utilitarian ends—that drives Pegobry’s (and most conservatives’) worry about legal realism, and redistributional policies based on it. And while I would be rash to make any promises at this juncture, I would hope to explore this further in a subsequent post or two, to outline what a good conservative version of legal realism might look like.

[1] See for instance Anton Herman Chroust and Robert J Affeldt, “The Problem of Private Property According to St. Thomas Aquinas,” Marquette Law Review 34:3 (1950), 155-75.

[2] See Joan Lockwood O’Donovan, “Christian Platonism and Non-proprietary Community,” in Bonds of Imperfection (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 97-120 for a particularly insightful discussion.

[3] Matthew Habiger, Papal Teaching on Private Property, 1891 to 1981 (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1990), provides a useful, though not altogether reliable, discussion.

[4] See ST II-II q. 66 a. 1 for Aquinas’s exposition of this right.

[5] This occupies Aquinas in ST II q. 66 a. 2.

[6] ST II-II q. 66 a. 2 ad 1.

[7] John Finnis, Aquinas : Moral, Political, and Legal Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 189.

[8] Anthony Parel notes that for Aquinas, private property is “derivatory and secondary” right, with “the obligation to realize the primary purpose of property, namely, use,” so that, “if there is conflict between use and ownership, there was no doubt in Aquinas’ mind which should prevail.” (“Aquinas' Theory of Property,” in Theories of Property, ed. Anthony Parel and Thomas Flanagan [Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1979], 96.)

June 3, 2014

The National Debt: A Guide for the Perplexed (and Alarmed)

Since coming back to the US, I have been surprised how often the national debt comes up in conversations about most any political topic. In discussions about inequality, for instance, I hear that we can hardly trust the government to address inequality given its own financial incompetence, and that if there is financial injustice about, surely the greatest injustice is the government’s systematic stealing from our children and grandchildren, whom we are saddling with an intolerable burden of debt. The theme of the travesty and looming catastrophe of US government debt has fueled the rise of the Tea Party, and played a role in the ridiculous fiscal standoffs in Congress over the past couple years. Of course, it is an important fiscal concern that both parties should be attentive to, but this is not usually how one hears it discussed—i.e., in the context of particular policies for fiscal responsibility. Rather, it is used as a universal putdown—a way of claiming, no matter what the particular point is under discussion, that the government cannot be trusted because its debt is both irresponsible and immoral, and that only a radical overhaul (one might almost say “overthrow” from some of the rhetoric) of our government can save us from imminent disaster.

As someone who used to be something of a national debt alarmist myself, I thought it might be helpful to put the issue in the proper context. The following is an expanded form of a little explanation I gave to a friend on the question after a political discussion last week.

1) Use real numbers

For one thing, inflation is generally ignored. All you have to do is yell out $16 trillion—an obviously immense sum—and point proven, right? "Over the last forty years, the debt has risen from $500 billion to $16 trillion—our debt is spiraling out of control.” Adjust for inflation, though, and it’s only risen from $2.4 trillion to $16.8 trillion. Obviously, however, that’s still a pretty substantial increase. That’s why it’s important to:

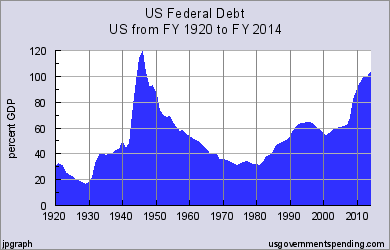

2) Use percentage-of-GDP numbers

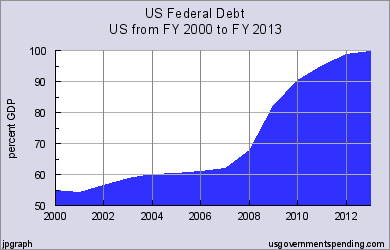

This really should be pretty obvious. A household that earns $50,000 a year but has a $100,000 debt is in a lot worse shape than a household that earns $200,000 a year but has the same debt. GDP is analogous in one sense, designating the total economic production of a country. Of course, it’s also not quite analogous, because 100% of a country’s GDP can’t go to the government (excluding communism, that is); even in the most extreme cases, such as Sweden, only a bit over 50% does. But as a way of measuring the burden of a debt relative to a country’s likely ability to repay it, debt-to-GDP is a good ratio to track over time. Using this ratio, we find that over the last forty years, the debt burden has not risen 32-fold or even 7-fold, but has a little more than tripled, from 31% of GDP to 99% of GDP. See this chart:

Of course, that is still a fairly substantial rise, but looking at things this way still puts things in a much less apocalyptic light. Why? Because:

3) The debt burden has risen and fallen over time.

After WWII, national debt rose over 120% of GDP, but was paid down quickly by high growth and high taxes. It rose again substantially under Reagan and Bush I to 63% of GDP, but was then paid down a good deal under Clinton to 54%. All of this was done without some radical restructuring of the government. All it took was sensible tax policy, good economic growth, and a modicum of fiscal responsibility. Current debt levels are not yet, by historic standards, out of control, and if politicians in Washington can agree to simple, common-sense measures, there is every reason to believe that they can be brought back down substantially again.

4) It’s not the Democrats’ fault.

Something else that jumps out at one from the chart above is how, since the resignation of Richard Nixon, increases in the debt have tended to coincide with Republican presidencies, and decreases with Democrat presidencies. The exception has been Obama’s presidency, though the vast majority of the increase there took place in the apocalyptic year of 2009, when the Great Recession crushed tax receipts and raised expenditures immensely. This points to the important fact that

5) Deficits are decreasing.