Colleen Higgs's Blog

September 16, 2013

Judging poetry

Recently I was asked to be the judge for 2013 DALRO prize for poems published in New Coin in 2012. I hesitated because I am not sure about the idea of choosing the best poem, and I am aware of how subjective I am in what I like and respond to. Two things swayed me, the first was that why not allow my aesthetic to be the one that gets to decide? And secondly, in recent years I have tried to follow the advice, I think it was Eleanor Roosevelt’s, “You must do the thing you think you cannot do”.

Recently I was asked to be the judge for 2013 DALRO prize for poems published in New Coin in 2012. I hesitated because I am not sure about the idea of choosing the best poem, and I am aware of how subjective I am in what I like and respond to. Two things swayed me, the first was that why not allow my aesthetic to be the one that gets to decide? And secondly, in recent years I have tried to follow the advice, I think it was Eleanor Roosevelt’s, “You must do the thing you think you cannot do”.

Here are my conclusions, written up in the citation below, after I spent time carefully reading the poems in question several times.

New Coin DALRO prize for 2012 issues

As Harry Owen said of the last DALRO prize, it is a subjective exercise for one person to choose the “best” or winning” poems. The poems I have chosen are the ones that I like best now in April/May 2012; these poems speak to me. This includes how they speak, I prefer shorter poems mostly, and I like poems that surprise and/or delight me, in voice, use of words and language, images, and craft.

First prize – “The Pot” by Genna Gardini

Second Prize – Village Potter’s Wife by Jim Pascual Agustin

Third prize – – “on a June day that I spent on the beach with two children” by Megan Tennant

I like the singularity of “The Pot”, the strangeness, the sharp decisive ending. Genna Gardini’s voice is playful and witty, and while easy to read and follow, further layers of meaning and association rise from the poem, the more times I read it. Her voice is strong and somewhat triumphant here, although there is humour and a slight sense of self ridicule.

“Village Potter’s Wife” is a short, striking poem, full of painful contrasts. At the heart of the poem is the joyful creation of pots, measured against death, destruction, grinding poverty. The poet manages to say a great deal about the life of this woman in three quick brush strokes, and to evoke deep sorrow and loss in this reader.

I like the particularity and ordinariness of “on a June day that I spent on the beach with two children”, the vivid and telling detail and the way the first stanza speaks to the second, and the combination of joy and bleakness, passion and ennui.

I also liked these poems very much:

All three of the poems by Deidre Byrne in Vol 48, no 1.

“How I make love” by David Wa Maahlamela

“Pretoria” and “voice” by Marike Beyers

“The 1st psalm for my dead ghetto” by Adorn Ka Mashigo

A man stabs a woman by Adriaan Coetzee

“spoon” by Elme Vivier

“Galaxies” by Jeannie Wallace McKeown

“Baby”by Thabo Jijane

June 17, 2013

The interview

For Short Story Day Africa 2013, here’s my take:

Do you actually enjoy writing, or do you write because you like the finished product?

I like to turn back

it’s a compulsion

to look back with longing and regret.

I’ve been a writer since I was eight

but mostly too afraid to admit it

What are you reading right now? And are you enjoying it? (No cheating and saying something that makes you sound like the intelligensia).

Most Saturday afternoons she finds herself alone, reading the Weekly Mail from cover to cover, ironing, or listlessly reading a novel on her unmade bed as though her imagination stretches no further than reading.

Have you ever killed off a character and regretted it?

My eyes die of hunger

as I make up my life

look for forgiveness, dream onward

my face is sour, her face is hungry

for a cup of tea, for enlightenment

I’d choke her, make a stew of her carcass if I could

she has no name, she hurts all over

her teeth bleed, her memory hurts like logic

her life hurts like liquor, like broken dinner plate

If you could have any of your characters over for dinner, which would it be and why?

How I miss your arm

and red fly music.

…

Here dust tastes like a man

who appears unexpectedly in the distance.

Which one of your characters would you never invite into your home and why?

blue Boadicea riding a chariot

naked into battle

heroic and foolish

Ernest Hemingway said: write drunk, edit sober. For or against?

Whisper your name to me

I’ll tell you mine in return

get drunk with me

and let’s feel no remorse

If against, are you for any other mind altering drug?

being happy is not a thread or a quilt or a road

it’s like bees buzzing on a hot afternoon

separately, then disappearing

Our adult competition theme if Feast, Famine and Potluck. Have you ever put food in your fiction? If so, what part did it play in the story?

It’s easier to travel by foot.

People take time to greet each other.

The only food is mealie meal and vegetables.

It’s a poor country.

What’s the most annoying question anyone’s ever asked you in an interview?

Will you love me forever?

Will I love you beyond your death?

Will you die before me?

If you could be any author other than yourself, who would you be?

I’d like to polish the words of your poems with beeswax,

hold them close to my nose, sniff them like fresh washing, like an early peach.

If you could go back in time and erase one thing you had written from your writing history, what would it be and why?

Women of all shapes and sizes and races have bruises on their faces. Once or twice I’ve wanted to say something, but what? I see you?

What’s the most blatant lie you’ve ever told?

Lying isn’t always bad, but mostly it isn’t good

for the digestion, it’s like white sugar

or mixing your drinks

If someone reviews you badly, do you write them into your next book/story and kill them?

My mother is slowly forgetting her life

Who she is and what holds her together.

She forgets more each day

as though forgetting were a job.

What’s your favourite bad reviewer revenge fantasy?

The extra wors with the Sunrise breakfast – vocabulary of intimacy?

…

You always remember too much of what doesn’t really matter to anyone but you.

What’s the most frustrating thing about being a writer in Africa?

The past was too bright, too hot, too white

What’s left over, left behind

is a long piece of string

Have you ever written naked?

You asked me if we’d closed the gate.

I would remember if I had closed it, the memory would be in my body

the metal cold on my hands, the heaviness of the gate.

Does writing sex scenes make you blush?

Your body is heavy. I ache and long to go to sleep. That is how it is between us.

Who would play you in the film of your life?

The room is full of moths, beautiful velvety ones.

If you won the Caine Prize for African Fiction, what would you do with the money?

Sometimes we sit on the couch and watch the lava lamp.

It’s not like watching TV

What do you consider your best piece of work to date?

I vow to do it better

not to hesitate to bring a child downstream

like gold floating in

a bowl

or a cup

What are you doing on 21 June 2013, to celebrate Short Story Day Africa?

sticking all the bits together, painstakingly gluing each piece in the dark.

As a poet, many of the questions weren’t relevant, so I decided to answer with lines from my poems and a couple from short stories.

Halfborn Woman by modjajibooks

Book details

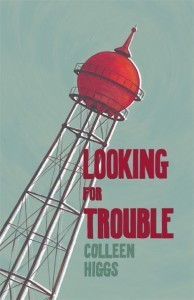

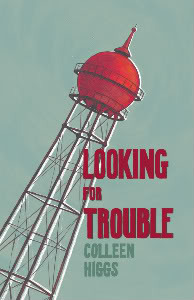

Looking for Trouble by Colleen Higgs

Book homepage

EAN: 9781920397425

Find this book with BOOK Finder!

eBook options – Download now!

eBook:

eBook type:

EAN:

[image error]Find this book with BOOK Finder!

Lava Lamp Poems: Colleen Higgs by

EAN: 9781920397258

Find this book with BOOK Finder!

Scribd.com book preview:

Not loading? View in the Little White Bakkie e-books store

eBook options – Download now!

eBook:

eBook type:

EAN:

[image error]Find this book with BOOK Finder!

August 10, 2012

Looking for Trouble reviewed in Rapport

Always cool to get a review, especially one where you feel the reviewer read the book carefully and gets it.

Always cool to get a review, especially one where you feel the reviewer read the book carefully and gets it.

Verhale spesifiek én transendentaal

Resensent: Christell Stander

Colleen Higgs se Looking for Trouble is een van die verrassendste boeke wat ek in ’n lang tyd gelees het. ’n Uiters gesofistikeerde balans tussen eenvoud en selfversekering straal uit elke verhaal én uit die samevoeging van die verhale.

Dit is Higgs se eerste volledige prosabundel, maar sy het al twee digbundels en kortprosa in literêre tydskrifte gepubliseer. Van die tien verhale in Looking for Trouble is sewe al elders opgeneem.

Haar bundel word opgedra aan almal wat al in Yeoville gewoon het, maar dis ’n versameling stories oor ’n tydperk in die Suid-Afrikaanse geskiedenis.

Dit is die tyd van PW Botha en sy vingerwysing; waarin die uitrol van die staat se militêre masjien tot sterker ondergrondse organisering gelei het. Dit was die tyd van die UDF, vrouegroepe, feministiese politiek, polities relevante navorsing en aktivisme.

To read the whole review in Afrikaans click here

Here is the translated into English version of the review (thanks to Karen Jennings):

Colleen Higgs’s Looking for Trouble is one the most surprising books that I have read in a long time. A greatly sophisticated balance of simplicity and confidence emanates from each short story, as well as out of the collection as a whole.

This is Higgs’s first complete prose collection, however she has published two poetry collections as well as short prose in literary journals. Of the ten short stories in Looking for Trouble, seven have been published elsewhere.

Her collection is dedicated to everyone who has lived in Yeoville, yet it is a collection about a specific time period in South Africa’s history.

It is the time of PW Botha and his finger-pointing; a time during which the rolling out of the state’s military machine led to stronger underground organisations. It was the time of the UDF, women’s organisations, feminist politics, politically relevant research and activism.

To read the rest of the review click here

Looking for Trouble by Colleen Higgs

Book homepage

EAN: 9781920397425

Find this book with BOOK Finder!

eBook options – Download now!

eBook: Looking for Trouble: And Other Mostly Yeoville Stories by Colleen Higgs

eBook type: PDF

EAN: 9781920397425

Download this eBook at LittleWhiteBakkie.com

Download this eBook at LittleWhiteBakkie.com

May 29, 2012

“Everything by heart” from Jacana’s Just Keep Breathing collection

My daughter turns ten today and as a way of acknowledging her birthday for myself, and what a milestone it is for me, I am re-publishing the story I wrote for the Jacana collection, Just Keep Breathing edited by Rosamund Haden and Sandra Dodson.

Everything by heart

I was so much older than most first time mothers-to-be. I wandered into bookshops and fingered through countless books about babies, feeling like an impostor. The world of motherhood a foreign country; I didn’t belong to it, nor it to me. I was hoping for a story to guide me into this hinterland, to teach me its customs and folkways. Little did I know that I would have to learn everything by heart.

At 29 weeks I thought I was having a stroke. I felt unbearably hot and nauseous, and the pain was excruciating – especially intense under my right rib. It was difficult to breathe, my skin felt too tight, I felt I might implode. It turned out that these were all symptoms of pre-eclampsia.

I gave scant attention to information in the pregnancy guides about complications relating to pre-eclampsia, out of a vague superstition that my full attention would only bring on this or one of the other dangerous illnesses outlined there. Pre-eclampsia is a potentially life-threatening condition for mother and child, which usually strikes late in pregnancy. Older mothers, especially those having their first baby, are more likely to develop it. Little is known about the causes of the disease or possible preventative measures partly because the window for studying it is very small; however, the best treatment is to deliver the baby.

At 29 weeks I thought I was having a stroke. I felt unbearably hot and nauseous, and the pain was excruciating – especially intense under my right rib. It was difficult to breathe, my skin felt too tight, I felt I might implode. It turned out that these were all symptoms of pre-eclampsia. [[I’d put this para before the previous one and leave out the first sentence of the previous one]]

I realised in retrospect that there had been signs in my pregnancy that something was not right. I’d been ill and tired throughout the 29 weeks, and had none of the positive symptoms described in the books. I’d had several serious migraines, but this pain so was extreme it was like an extended convulsion. All of these episodes seemed to happen on Sundays or public holidays, which meant house calls and paying extra for the heavenly relief of the 3 in 1 injection cocktail of Voltaren, tranquiliser and anti-nausea medication, that would blissfully ease the intense, prolonged pain and vomiting and finally bring sleep.

I was admitted to hospital on a Monday, and told by Dr J, my gynaecologist/ obstetrician, that he would try to keep my baby inside me for as long as possible. I wore a belt across my chest to monitor the baby’s heartbeat. She seemed to be doing OK. After the third pre-eclamptic episode, Dr J decided to do an emergency Caesar on the Thursday – May 30th, 2002, which would make Kate, my baby girl, 11 weeks early. When I first realised that my baby was going to be premature, that I was unable to incubate her inside my body where she belonged, I cried with guilt and sadness, feeling that I had let her down.

At the delivery, André, my husband, was at my head with the anesthetist, while the lower half of my body was hidden behind a curtain. Being very tall, André could see over the screen and witnessed the entire procedure, from Dr J cutting me open to the extraordinary moment when he pulled the tiny, bloody creature out. Kate looked nothing like the pictures of newborn babies in the books. She was tiny, almost fleshless, a newly hatched bird that belonged firmly in its nest. She seemed old and wise, unearthly. My entire being flooded with tenderness as I held and kissed her for a few seconds before she was taken away from me. André followed her and the paediatrician out of the room to the Neo-natal ICU. I saw her again only hours later, in the early evening, when I had recovered from the operation a little.

It’s easy enough, now, to give a factual account of what I experienced in hospital, but it’s not so easy to write about the inside of the experience, even less so to convey anything of what it might have been like for Kate. She underwent numerous blood tests in the form of pinpricks to her heels; she received several doses of antibiotics, iron drops to ward off anaemia, caffeine drops to make her heart beat faster, oxygen too, although she didn’t ever have to be on a ventilator. She had jaundice and spent 3 days and nights under UV lights in the first week of her life. She was given Surfactin to strengthen her lungs. She weighed 1080 grams – just over a kilo – when she was born and then her weight dropped down to under a kilo for a week or two.

The first day or so of Kate’s life I was sore from the Caesar, and my neck was painfully stiff from leaning over the incubator, from the tension of the whole experience. My breasts were enormous and tender and the only relief I got was from expressing my milk, which was pale brown when it first came in. At once it was sent off to the lab to be tested in case there was something wrong with it. I was ashamed as I waited for the results, unsure of myself, of my milk, of my role. When the lab determined that it was fit for Kate’s consumption, I was relieved, filled with joy. I had dreaded the worst. She was initially given 1 ml at a time from a tiny syringe suspended cleverly above her with an elastic band that led into a tube down her nose straight into her stomach. I became adept at filling the syringe, at feeding my baby in this way.

In the first ten days or so she lay in plain sight in an elevated open incubator against the back wall of the NICU. She was kept warm by the heated incubator and covered with a miniature space blanket when she wasn’t being held. She was naked except for a tiny nappy and a great number of tubes and monitors attached to her body. She cried seldom, but when she did it was a peculiar sheep-like bleat.

One morning, while sitting in the plastic chair next to the incubator holding her next to my skin, I looked down at her and noticed that she had turned very white, almost blue. She was cold too. Time stopped for me. The paediatrician was called and she was given a life-saving blood transfusion. I can’t remember what it felt like to be in the moment of the ordeal. I have forgotten how hard it was. At the time, I coped by taking everything one day at a time, one hour at a time. I didn’t plan or think ahead about next week or next month, or the end of my maternity leave.

While in the NICU, I watched other mothers who skillfully changed nappies and used special cotton buds and lotions and wipes. I hadn’t bought anything for my baby, not wanting to tempt fate. While we were in hospital André did the first baby shopping: prem nappies and Kate’s first toy, a small, soft purple Eeyore. I was shell-shocked, unprepared. It was enough witnessing her incubation from the outside. With the help of nurses, the paediatrician and other mothers, but mostly just by watching her closely, I began to figure out what she needed minute by minute. And what I was able to do.

Kate’s birth brought an overflowing of gifts: babygros, vests – even an embroidered one – hats, blankets, hand-knitted jerseys, booties, dungarees, miniature sheepskin slippers, a plastic bath chair, a pram, a cot and a house full of flowers. All who knew us seemed to welcome her into the world.

I remember sitting in the NICU next to the incubator drinking tea about a week after Kate was born when the convener of the antenatal classes phoned to tell me that the date of the first meeting was postponed. At first I didn’t know what she was talking about, then I started to cry. “My baby has been born already,” I told her. She was kind and sympathetic, which made me cry even more.

The first night I had to leave Kate in the hospital and go home was particularly bleak, the world wet and cold, the drive up Hospital Bend to Woodstock too far. My whole being resisted leaving, my arms felt too empty, too light. For two months I lived in a nether-world of driving up and down to the hospital and sitting next to her incubator, holding her or simply being with her while observing the goings-on in the NICU, seeing babies leave and new babies arrive. All the time I was away from Kate I felt like I was in a transit lounge – unreal, in-between. I felt present only when I was with her. Everything else was preparing, recovering, gearing up for, resting.

Every time you enter the NICU you have to wash your hands in order to cross the threshold into the sacred place, the place beyond the glass windows, beyond ordinary daily life. Friends came to see Kate when she was a little bigger and I was allowed to carry her to the window for a few minutes to show her to them. Once, when a dear friend came to see Kate, a nurse who had become quite possessive of her took her away from me, and held her up to my friend. I insisted on taking her back into my own arms. As soon as I did so the nurse in turn insisted that Kate be taken back into the NICU as she had been out of it long enough. In those first weeks I had to submit to the authority of the NICU nurses, and had no option but to give Kate back to them when they told me to. I wasn’t allowed to hold her for too long in the beginning. When she was sick with a gastric infection in the first weeks, I wasn’t allowed to pick her up at all. I could touch her, but only with my hands through the little doors in the side of the incubator. My back and upper arms tired and stiffened from the odd positioning.

Those early months were about existing in the present, not thinking, but observing, listening, sitting still, learning a slow, meditative patience while she grew gradually bigger and stronger. Almost imperceptibly she gained a few grams each day and took in a little more milk while I sat at her side, her attendant mother, guardian angel, witness, nurse. It became a meditation — being there for her. Being. There.

I remember drinking coffee in disposable cups from the hospital coffee shop. I remember the smell of popcorn, which the nurses often bought to eat at quieter moments. I remember how long the nurses’ shifts were – 12 hours. One older nurse told me, “The best way to be a mother is to learn to trust yourself. Listen to that inner voice. Trust it.” She told me this late one night when we were the only adults in the NICU. All the sick and premature babies were in their cots and incubators and it was dark and quiet except for a beep now and then and the humming sound from the electronic equipment.

Twice a day I visited her, every morning from about 8 till about 3 in the afternoon and then again at night. Before my night visit I would sit close to the fire in my great grandmother’s chair, deriving some comfort from it. André bought coal and wood and made the fire in the small Victorian fireplace in our Woodstock home each cold, wet night that winter. I would relax slightly as I stared silently into the flames between mouthfuls of supper, bracing myself for the drive back to the hospital. Our dogs lay next to the fire all night. The wooden floorboards near the fireplace were pocked with black scorch-marks from decades of popping coal. I would leave André and the dogs and head out into the rain. Cape Town winter rain is more than just weather – it can feel endless, a permanent submersion, frightening for a non-native. No matter how cold or wet it was outside as soon as I entered the NICU, I would overheat.

Almost daily, new faces, new mothers arrived. I became a fixture, nearly invisible, in my daily vigil. In three days the other women gave birth, got the hang of things and went out into the world with their babies who were kitted out in new clothes and receiving blankets, matching baby bags and new car seats. I stayed on and on. After several weeks of sitting there day after day, I knew most of the routines; I could have acted as an NICU assistant. I remember the nurses gossiping crossly about a twenty-something mother who only visited her baby every two or three days. I also saw that there were far more challenging misfortunes than being premature. There were babies who had to be ventilated; there were babies who were much sicker than Kate. A baby with spina bifida came to the NICU in preparation for a long and highly specialized operation. She was much older than the other babies in the ward.

One of my most traumatic experiences was attempting to breastfeed Kate in the hospital under strict supervision. She had to learn to feed before she could be released from her hospital sentence. I would try and fail. Well-meaning nurses weighed her before and after a feed, and there would be regretful shakes of the head, no – she didn’t take anything in. Other nurses, many of whom hadn’t ever had a baby of their own, offered me nipple caps, suggested different positions for her head, demonstrated how latching is supposed to work, but between us all we couldn’t get it right. Eventually, thanks to a kind word from an older nurse who had two of her own children, I realised that Kate needed to bottle-feed or we would be in hospital much, much longer. I pumped my breasts, milked myself several times a day and stored the milk either at the NICU or at home in the freezer. Determinedly, I taught my baby to drink from a bottle.

Kate’s first bath was in a 2-litre ice-cream container. Before then I washed her body inch by inch with cotton wool and warm water. How light she was and how small, so small she fitted into my hand. I’ve forgotten or mostly forgotten those tiny nappies and knitted caps and what being on red alert was like.

When we brought Kate home she weighed just two kilograms, still smaller and lighter than most babies are when they are born. I had been deeply apprehensive that I would need to monitor her breathing constantly, that I would need a gadget to tell me that my baby was still alive. But when the time came I trusted the connection between us enough; I knew that she knew how to breathe. She slept in our bed, snuggled between us, and, tiny as she was, I knew that I wouldn’t roll over onto her. I had the strangest sensation of both sleeping and being aware of her at the same time, cradled next to my body. I felt archetypal, animal, like a great lioness with my cub at my side, my body a source of warmth and food and comfort.

As I write this Kate is five and a half. She delights me every day with her passionate will and her own particular self, the same powerful creature who was evident from the first moments in the incubator. Together we got through. She was a survivor then and she is a survivor now.

May 3, 2012

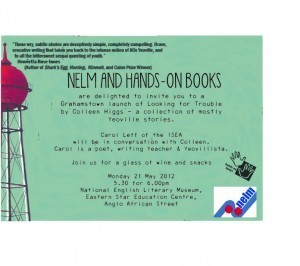

Book Launch: Looking for Trouble by Colleen Higgs

NELM and Hands-On Books are delighted to invite you to a Grahamstown launch of Looking for Trouble – a collection of mostly Yeoville stories.

NELM and Hands-On Books are delighted to invite you to a Grahamstown launch of Looking for Trouble – a collection of mostly Yeoville stories.

Looking for Trouble is a collection of short stories set in Yeoville from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s. The stories capture with a dark humour the lives of young people trying to make a go of things, given the constraints of the country and the volatile period. Most of the stories have been published in literary magazines; one of the stories was published by Femrite (Uganda) in a collection called World of our Own. A slightly earlier version of the title story was published in a collection of stories by South African women edited by Maggie Davey, Dinaane, Telegraph Books, London.

Comments about the collection:

“These wry, subtle stories are deceptively simple, completely compelling. Brave, evocative writing that takes you back to the intense milieu of 80s Yeoville, and to all the bittersweet sexual questing of youth.” Henrietta Rose-Innes (Author of Shark’s Egg, Homing, Nineveh, and Caine Prize Winner)

“Looking for Trouble is a book that will make you late for work. Like an unexpected fist in the stomach. Words that will stay with you long after you turned the last page.” Melinda Ferguson (Author of Smacked and Hooked)

“These stories awakened in me a sense of nostalgia, not only for Yeoville in the early nineties, but for being young, love’s fool and sexually reckless. At some point, experience forces us to lose our illusions and come of age, damaged by love but wiser. This spot-on collection captures that arc of life and, as I turned the last page, I felt we had lived well, if imperfectly.” Rachel Zadok (Author of Gem Squash Tokoloshe)

Event Details

Date: Monday, 21 May 2012

Time: 5:30 PM for 6:00 PM

Venue: National English Literary Museum, Eastern Star Education Centre, Anglo African Street, Grahamstown

Guest Speaker: Carol Leff

Refreshments: Come and join us for a glass of wine

RSVP: Colleen Higgs, Hands-On Books, cdhiggs@gmail.com

Looking for Trouble by Colleen Higgs

EAN: 9781920397425

Find this book with BOOK Finder!

April 12, 2012

Launch of Looking for Trouble by Colleen Higgs at Love Books

[image error]

[image error]

Love Books and Hands-On Books are delighted to invite you to the Joburg launch of Looking for Trouble by Colleen Higgs. Melinda Ferguson will introduce Colleen and be in conversation with her. Colleen will read from the collection too. Join us for a glass of wine and a snack.

Love Books and Hands-On Books are delighted to invite you to the Joburg launch of Looking for Trouble by Colleen Higgs. Melinda Ferguson will introduce Colleen and be in conversation with her. Colleen will read from the collection too. Join us for a glass of wine and a snack.

Looking for Trouble is a collection of short stories set in Yeoville from the mid-1980′s and early 90s. The stories capture with a dark humour the lives of young people trying to make a go of things, given the constraints of the country and the volative period.

Most of the stories have been published in literary magazines or in collections both here, the UK and in Uganda.

Event Details

Date: Wednesday, 25 April 2012

Time: 5:30 PM for 6:00 PM

Venue: Love Books,

Bamboo Centre,

53 Rustenburg Rd,

Melville | Map

Guest Speaker: Melinda Ferguson

Refreshments: Come and join us for a glass of wine

RSVP: Love Books,

info@lovebooks.co.za, 011 7267408

www.lovebooks.co.za

Praise for Looking for Trouble

“These wry, subtle stories are deceptively simple, completely compelling. Brave, evocative writing that takes you back to the intense milieu of 80s Yeoville, and to all the bittersweet sexual questing of youth.” – Henrietta Rose-Innes, author of Shark’s Egg, Homing, Nineveh, and 2008 Caine Prize Winner

“These stories awakened in me a sense of nostalgia, not only for Yeoville in the early nineties, but for being young, love’s fool and sexually reckless. At some point, experience forces us to lose our illusions and come of age, damaged by love but wiser. This spot-on collection captures that arc of life and, as I turned the last page, I felt we had lived well, if imperfectly.” – Rachel Zadok

“Looking for Trouble is a book that will make you late for work. Like an unexpected fist in the stomach. Words that will stay with you long after you turned the last page.” – Melinda Ferguson

About Colleen Higgs

As well as being a writer, Colleen Higgs is also a publisher, she started the ground-breaking independent southern African women’s press, Modjaji Books in 2007. She lives in Cape Town with her daughter and cat. Looking for Trouble is her first collection of short stories. She also has two collections of poetry Lava Lamp Poems (2011) and Halfborn Woman (2004) all published by Hands-On Books.

Book Details

Looking for Trouble by Colleen Higgs

EAN: 9781920397425

Find this book with BOOK Finder!

Photo of Colleen Higgs by Liesl Jobson

April 7, 2012

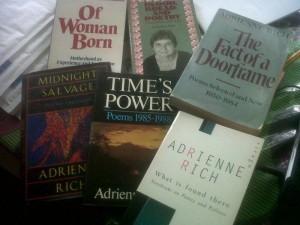

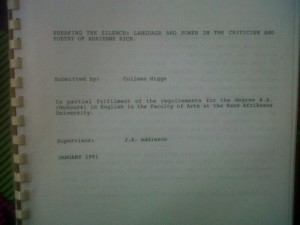

A personal tribute Adrienne Rich

Adrienne Rich died last week, now you see her name on the internet and it says, “Adrienne Rich 1929 – 2012″. A great poet has died. She’s left a legacy of poems and prose and the example of a life well lived, an engaged life, someone who walked her talk. If you google her name, you will find out all the facts that are known about her, the books she wrote and had published, the prizes and honours she received, the ones she declined or shared and so on.

Adrienne Rich died last week, now you see her name on the internet and it says, “Adrienne Rich 1929 – 2012″. A great poet has died. She’s left a legacy of poems and prose and the example of a life well lived, an engaged life, someone who walked her talk. If you google her name, you will find out all the facts that are known about her, the books she wrote and had published, the prizes and honours she received, the ones she declined or shared and so on.

…

4.

Every drought-resistant plant has its own story

each had to learn to live

with less and less water, each would have loved

to laze in long soft rains, in the quiet drip

after the thunderstorm

each could do without deprivation

but where drought is epic then there must be some

who persist, not by species betrayal

but by changing themselves

minutely, by a constant study

of the price of continuity

a steady bargain with the way things are

From “The desert as a garden of paradise’ by Adrienne Rich

I want to tell you something of what she meant to me. In 1989, I was a high school English teacher, doing my English Honours degree part time, at what was then RAU (now the University of Johannesburg). In the Poetry course we did, Jenny Addleson introduced us to Adrienne Rich; I felt my inner world shift, subtly, deeply, dramatically. She articulated so clearly and exquisitely thoughts I barely knew I harboured, feelings I was disturbed by. I began to realise that things were not as they seemed. There was more choice, and it had to be actively claimed. More than anything I had read before I began to really understand the impact and effect of patriarchy.

I want to tell you something of what she meant to me. In 1989, I was a high school English teacher, doing my English Honours degree part time, at what was then RAU (now the University of Johannesburg). In the Poetry course we did, Jenny Addleson introduced us to Adrienne Rich; I felt my inner world shift, subtly, deeply, dramatically. She articulated so clearly and exquisitely thoughts I barely knew I harboured, feelings I was disturbed by. I began to realise that things were not as they seemed. There was more choice, and it had to be actively claimed. More than anything I had read before I began to really understand the impact and effect of patriarchy.

I went on to read as much of her work I could lay my hands on.

My long paper was on her prose and poetry in general with a detailed examination of three poems, all classic Rich. “Diving into the Wreck”, “The Burning of Paper instead of Children”, and From an “Old House in America”.

Some of Rich’s ideas, principles and poetic strategies that have stayed with me all these years:

Her identifying and validating the ‘invisible’ work that women do that recreates the world endlessly and that is perceived by patriarchal society as trivial and insignificant – have a look at a poem like “Natural Resources” to see how she describes this:

My heart is moved by all I cannot save:

so much has been destroyed

I have to cast my lot with those

who age after age, perversely,

with no extraordinary power,

reconstitute the world.

Her memorialising of and rehabilitating women who have done important work, such as suffragettes, anti-slavery activists, early women doctors. In some poems she just lists the names of women, in the way that one sees names on war memorials. It is partly a futile exercise, but better than the alternative, which is silence. She also acknowledged the isolation women often feel as they do their work, and she encouraged women to connect with each other to militate against this isolation. For Rich, part of her work as a feminist scholar and writer was to be a cultural archeologist.

She highlighted the multiple ways (that continue today in 2012) in which women’s writing and scholarship is mocked, trivialised, treated as the exception that proves the rule. The style and content of their work is criticised as too personal and not about important enough issues (see the chick lit debates that have raged on BooksLive and the Vida Lit statistics about women in literary magazines, the number of reviews that women writers get and so on).

Some of the stylistic tactics that Rich employs in her poetry is to avoid “quasi-liturgical” diction which evokes awe and reverence in the reader. She re-enters older or existing texts and re-visions them from new perspectives. She points out opportunities for choosing, in other words resisting being a victim, and recovering agency.

Rich’s use of punctuation and textual layout as a way of referring to the half-said, the silences and the other layers of meaning.

She had a definite political agenda in her poetry. She didn’t want her work to be elitist, and she struggled with the idea of “poetry as language and poetry as a kind of action, probing, burning, stripping, placing itself in dialogue with others out beyond the individual self” (Blood, Bread and Poetry).

I titled my first collection of poems Halfborn Woman, as a way of acknowledging her influence on me. I realise that my desire to start Modjaji Books, my commitment to feminism, my desire to publish the writings of southern African women writers who might not otherwise have a chance to get their writing published, all of this can be linked back to my connection to the powerful mind and writings and example of Adrienne Rich. Her brilliant articulations of what poetry is about and why it is necessary have been one of the strong encouragements I’ve felt to continue publishing poetry, and to allow a range of women’s voices the opportunity to be heard.

She continually paid tribute to women she saw as foremothers, I want to pay tribute to her too. It has been gratifying for me to see how many people were also deeply touched and influenced by her and how widespread the discussion and tributes to Adrienne Rich have been since she died.

Today’s UK Guardian has Eve Ensler and Jackie Kay paying tribute

“The moment when a feeling enters the body is political. This touch is political.”

I must have read and reread those particular words from Adrienne Rich’s poem “The Blue Ghazals” thousands of times, as if the repetition would somehow dissolve the lines drawn between the personal and political, the singular and the collective, the private and the public, the body and the earth.

Ms Magazine reminds us that her writings were a call to action, needed now more than ever

Last week we lost feminist foremother Adrienne Rich, to whom we owe boundless gratitude. Her poetry and prose guided many of us through the “anger and tenderness” of motherhood, helped us challenge countless “unexamined assumptions” and promised us that “we’re not simply trapped in the present… we can make … history with many others.”

There is much more I could say, but for now this will have to be enough.

December 12, 2011

Review of Lava Lamp Poems in latest Scrutiny 2

The December 2011 edition of Scrutiny 2, the UNISA literary journal, includes a review of Lava Lamp Poems by Deidre Byrne. As reviews of poetry are few and far between, it is thrilling to get a review, and even more thrilling to have one by a reviewer who ‘gets’ your work and takes the time and space to write about it as fully as Byrne has done.

The December 2011 edition of Scrutiny 2, the UNISA literary journal, includes a review of Lava Lamp Poems by Deidre Byrne. As reviews of poetry are few and far between, it is thrilling to get a review, and even more thrilling to have one by a reviewer who ‘gets’ your work and takes the time and space to write about it as fully as Byrne has done.

Almost the first aspect of the volume to strike the reader is its profound South African-ness. For example, “the comfort of parquet” lists a series of iconic places in Johannesburg that the speaker misses, including “the Market Theatre, Jamesons, Kippies, Rumours, Scandalos / the Black Sun” (17), and each of them conjures, for the reader who is literate in Johannesburg landscape and culture, a particular, unique shade of feeling that is skilfully associated with a period in South African history. This is more than a mere list of places the speaker has visited; each is thoughtfully selected to form a pencil-stroke in a sketch of a period in history that is contrasted with “the too finely tuned / anxiety of all that was going on around / and within me — crushing, brutal, oppressive” (17). The accumulated negatives at the end of the line form a powerful contrast with the remembered ease of the speaker’s past precisely because of the poet’s care in choosing the spaces she mentions.

For the full review click here

Book details

Lava Lamp Poems: Colleen Higgs by

EAN: 9781920397258

Find this book with BOOK Finder!

Scribd.com book preview:

Not loading? View in the Little White Bakkie e-books store

July 22, 2011

Lynette Paterson on Lava Lamp Poems at the Grahamstown launch

As some of you know, Ingrid Andersen and I had a Grahamstown launch of our books, >Piece Work and Lava Lamp Poems during the Festival. NELM kindly hosted the event and I loved the evening. My friend, Lynette Paterson, introduced me and my poems, and Phillippa Yaa de Villiers did the honours for Ingrid.

As some of you know, Ingrid Andersen and I had a Grahamstown launch of our books, >Piece Work and Lava Lamp Poems during the Festival. NELM kindly hosted the event and I loved the evening. My friend, Lynette Paterson, introduced me and my poems, and Phillippa Yaa de Villiers did the honours for Ingrid.

It was wonderful for to hear Lynette speak about my work at NELM. I felt as though I was basking in warmth and light; and that the best of me is truly seen by her. I couldn’t take it all in, so I asked her if she would send me what she said, which she did and she gave me permission to publish her introduction. So here it is.

Launch of Lava Lamp Poems by Colleen Higgs, at NELM, 7 July 2011

Lava Lamp Poems is Colleen Higgs’ second collection of poems, published by Hands-On Books. Halfborn Woman was launched in this same venue in 2004.

First I want to pay tribute to Colleen for her hands-on involvement with writing and books – her own and others’. As a writing teacher in Grahamstown, the manager of community publishing at the Centre for the Book in Cape Town,

and the founding director of Modjaji Books, she has consistently turned her hand to the task of nurturing writers and writing, and latterly, women writers in particular. Modjaji has published 27 titles (and counting) in its first four years, with already several prize nominations and winners among them. Colleen’s vision and enterprising spirit are remarkable and inspirational.

In the midst of this, Colleen pursues her own life and her own art, and now brings us her second collection. Colleen’s personal life is the ground of her art. The chatter of her daughter; the silence of her partner; memories of others she has loved; places that have shaped her – these are the sources of her poems, and progressively they unfold an ever more fully born woman. From a high balcony in Troyeville, the girl with the pert new haircut and the “finely tuned anxiety” (17) sees into the far, firework-illuminated distance, but cannot discern the precipice she is on (20). The mother on the living-room couch with her small daughter watches the lamp in the darkened room, and discerns the meaning of present, past and future with a “slowed down, profound” wisdom that rises and sinks like the warm yellow wax in the lava lamp (47).

Perhaps more than anything, what the writer of this collection discerns is how short is the journey between the long-boned, smooth-skinned child, and the grandmother whose baggy skin is glimpsed as the faded blue nighty rides up her thighs. “You can’t pretend it won’t happen to you.”(12) “The birds have all gone, the river is fuller / the days are shorter, the rain is coming. My life will end. I’ve seen it now.” (39)

From such epiphanies, memories and workaday incidents, the poet examines who she is. The child asleep in bed with her pushes against her with her legs, as if to launch herself: “as if you’re eager to push away. I am your ground.” (40) The poet ‘pushes against’ each memory, each incident, testing, risking, launching. She writes to find her own ground.

And she writes against forgetfulness, towards wholeness. “My mother is slowly forgetting her life, / who she is and what holds her together. … I want to / remember enough to follow the pebbles all the way / back into the dark forest.” (30) (Incidentally, the presence of fairy tales lends both charm and a searing incisiveness to the collection – as is the way with fairy tales.)

While the life-content of her poems is processed in the writing, and the form is carefully crafted, Colleen’s poems tend not to have answers, points of arrival, or definitive conclusions. In form and content, the poems swell, undulate, “bubble and loop” (47). Like the yellow wax in the lamp, they rise and fall as the density of thought and feeling freely changes. On the whole they have the viscous quality of real lava – which may be why the flow of the prose poem is a favoured form. But even when form congeals into a surface crust, the inner fluid is restless, moving, seeking, asking – and sometimes shocking the reader (and probably the writer herself) with a hiss of steam as it encounters something unexpected: “sometimes I feel I could even slap strangers, / for no apparent reason” (9).

I’ve said nothing about the more ‘public’ sequence entitled, Notes from a New Country, in which the writer very tentatively, and humorously, ‘pushes against’ a new order of things, testing, looking to find new ground. Perhaps we can prevail upon her to include an extract in her reading.

It is with pleasure that I present Colleen Higgs and invite her to read from Lava Lamp Poems.

Lynette Paterson

07/07/2011

May 17, 2011

The fabulous, the dark and the hilarious #flf2011

This is my fourth or fifth time of going to the FLF. I always go with my close friend and it becomes a weekend of relaxing, pleasure and work. Thankfully this year I did not have a launch organised, so was able to be much more chilled.

Over the past few years Jenny Hobbs has asked me to chair a session and I always say yes. Even when I am overwhelmed or know absolutely nothing about the topic, I say yes.

This year I chaired the session entitled Love Stories; panelists were Lindsay van Rensburg, editor from Kwela; Nani Mahlanga – Sapphire romance author and the inimitable Fiona Snyckers, who needs no introduction to BookSA readers. I was bemused to be asked to do this one as I am probably the least romantically inclined, the person least likely to have read a romance that I can imagine. But I stuck to my rule and said yes. I learnt the following: South African romance readers require a little more challenge than the straightforward Mills and Boon formulaic stories, otherwise they get bored. Sapphire promotes responsible sex, there will be a condom in the story at a strategic point. Romance is seen to be a gateway to other kinds of literacy, so could be a way of ‘growing more readers’. I was left with a number of questions, such as; is there a tradition of gay/lesbian romance fiction? I wonder why the ‘rape fantasy’ is becoming more prevalent in international romances? Where will this all lead? I was hugely encouraged by the way our writers and publishers this genre are approaching this opportunity. I look forward to hearing more as they see how sales go and how readers and new writers develop.

The fabulous

Seeing and greeting and chatting with friends and colleagues that one normally only has online contact with, meeting new people, eating divine meals in various Franschoek eateries with fascinating friendly folk, the weather, seeing Modjaji authors looking pleased with their Franschoek experience.

Lauren Beukes‘s sloth draped over her shoulders, she looks like a real celebrity!

Listening to Janice Galloway’s talk; I was fortunate to have read her memoir, This is not about me before the festival. Galloway was brilliant, vivacious, confident and I loved her Scottish accent. Her writing is dark, funny, devastating and brilliantly written.

In the Masculinities session, Melinda Ferguson carried off her “counterpoint” role with enormous charm and aplomb. What was puzzling was that the issue discussed by the panelists was race rather than masculinities. Maybe it was that the panelists were seated on a stage looking over a sea of middle-aged to elderly (mostly) white faces, and race is what came up for them?

the dark

My bag was snatched while I was at the BookSA celebration organised by Louis Greenberg and Sarah Lotz. During the main course, a waitress noticed a bag lying on the ground just outside of where we were sitting. My wallet was open and all my cash – which wasn’t much was taken. And then I noticed my cellphone was gone. A few minutes later the manager had security and the police on the case and my things were retrieved. I had to go to the police station to identify my belongings. It turned out that a gang of boys, between ten and fifteen years old were the culprits. My friend and I sat at the police station, we had to wait for the detective to arrive. Eventually we asked if we could go back to the restaurant and have our dessert and coffee and pay. This we did and then when we came back to the station the boys were in the front of the charge office sitting in row. They were apparently well known to the police. Feral boys. They had to wait for the parents to fetch them. By the time we left the station at about 12.30 only one mother had arrived. We heard that there were two armed robberies in the squatter settlement. A group of Somalians arrived at the station to lay the charge regarding the first armed robbery.

I decided to lay a charge against the boys, as this would mean that some of them might go before a magistrate and be put into a diversion programme for youth at risk. I will have to go through to Franschoek at some point and spend a day in court waiting for this case to come before the magistrate.

I saw the boys again on the streets on Saturday and Sunday, drifting up and down the main drag.

Sigh.

the hilarious

Justin Cartwright’s anecdote “Iris Murdoch’s method of writing was to lie on her back for three months on the floor and then get up and write the novel in a week.”

Zakes Mda saying something like this:

“I had never read a memoir or autobiography, so I thought I better read one or two. I started with Gunther Grass, after about ten pages or so, I thought nahhh, I am a storyteller, I have written all these novels, I can do this.” He then proceeded to write it in three months and refused editing suggestions, he wanted it to be shaggy (I think that is what he said).

Khaya Dlanga’s wonderful story, that I hope he will write one day, told us with how To Kill a Mockingbird hampered his love life.

Michiel Heyns’s dry humour as he spoke about reviews in that session, see below:

[48]: Critical Factors (Hospice Hall)

Is author hagiography taking the place of informed literary comment? Regular book reviewers Imraan Coovadia, Michiel Heyns and Tymon Smith discuss the rise and rise of the personal versus the critical with Cape TimesBooks Editor Karin Schimke.

The toilet saga and looming elections as a backdrop to the FLF. The toilet humour in the Sunday papers, particularly Ben Trovato’s Whipping Boy.