Geoffrey A. Moore's Blog

July 5, 2022

Starting the Dialogue: Discussing the Infinite Staircase via Book Review

In his review of The Infinite Staircase, Bill Bartlett has done me the honor every author most cherishes—he has read my book thoughtfully and has engaged directly with its claims. He and I don’t see eye to eye on many of these claims, but we both have deep respect for Western philosophy and religion, so I welcome the opportunity to do a kind of Point/Counterpoint with his review. In this context, I am reproducing what he says first and then interspersing my commentary in a different font color. Here goes.

Book Review: The Infinite Staircase

When I first came across The Infinite Staircase, I was intrigued for two reasons: The title suggested that the book was not in the same vein as the author’s previous work and that it would tackle morality from a secular viewpoint. As such the title was extremely well chosen.

The Infinite Staircase is the latest from Geoffrey Moore, who is famous for books such as Crossing the Chasm and Zone to Win, which I quote quite frequently when talking about product management. It is a departure from those books as it deals with the strategy for something larger than products and companies: life itself. It attempts to give a description of the universe and human life in it, and then derive from that a framework for grounding ethics and morality. Moore remarks that the world is becoming less and less religious which is eroding the foundations that fostered ethical behavior. Moore sees the need for a secular foundation in order to regain the stability that society needs and that ethics provides.

I don’t want to quarrel with this representation, but I do think it is a bit one-sided when it comes to my commitment to a secular metaphysics. I am blown away by the magnitude and wonder that the secular story of creation tells. The fact that humanity has been able to develop such a complete and verifiable explanation of how we got from a Big Bang to the present day astounds me. So, I do not want to set it aside when it comes to establishing the grounds for ethical behavior. It is not, in other words, that I am disappointed with religion, although I do take it to task from time to time, but rather that I am unwilling to sideline what I consider to be some of humanity’s best work when it comes to tackling issues of spiritual and moral importance.

Moore’s proposed foundation for ethics is the various sciences which he places on consecutive steps of a staircase. Each stair emerges out of the previous one: it is constrained by the previous stair but not wholly predicted by it. For example, chemistry emerges from physics because physics applies a constraint on what chemical entities can do without being able to predict every behavior that they have. It is a shame that Moore does not explain the concept of emergence and assumes the reader is familiar with it. I myself was skeptical that chemistry emerges from physics and was glad to be able to find a well-researched article on the subject.

I confess to being guilty as charged here. I am in awe of emergence and how it generates complexity, and it certainly deserves a strong foundation. In the bibliography of The Infinite Staircase, I do reference some works on the topic, of which I think John Holland’s Complexity: A Short Introduction is the best one to start with.

Because of emergence, there is no single science that completely describes and predicts everything in the universe. Therefore any unifying theory must contain all of them. In fact, it must contain many other sciences, some of which have not been explored yet. Hence the fact that the staircase is assumed to be infinite in both directions. In spite of this, Moore feels that we have enough of a grasp on the “middle” of the infinite staircase in order to ground ethics.

In fact, Moore focuses on a smaller subset of the staircase he describes by stating that goodness begins with desire. This is surprising given that many points of contention in today’s society have a biological component.

Unfortunately, Moore’s proposed framework for ethics is flawed for several reasons that I would like to discuss.

Deriving an “ought” from an “is”

From the beginning, Moore had his work cut out for him. Many have tried and failed to do what Moore attempts, that is to ground a theory of what ought to be in a theory of what can be. Many philosophers have weighed in on this problem. David Hume is famously credited for suggesting that one cannot derive an “ought” from an “is”. Jean-Paul Sartre, quoting Dostoevsky, affirmed that since God does not exist, anything is justifiable.

the distinction of vice and virtue is not founded merely on the relations of objects, nor is perceived by reason.

— David Hume. A Treatise of Human Nature (1739)

Bill is correct that I do believe you can derive an ought from an is, that this is an important objective for the book, and that it does put me at odds with Messers Hume, Sartre, and Dostoevsky. My claim is that consciousness emerges from desire (this aligns with Hume’s famous comment that reason is in service to, and not the master of, the passions). I take this relationship between desire and consciousness to establish the is. Desire is driving behavior, and we have no choice in that matter. We are compelled to desire. The vehicle we are riding on is irresistibly in motion—all we can do is seek to steer it.

That’s where values come in. They emerge from conscious beings interacting socially with one another, specifically within the context of raising families and interacting with neighbors, something we can see in higher order mammals who nurture their young, discipline their peers, court their mates, and defend their group. All four of these behavioral domains entail oughts, even among pre-linguistic animals, and certainly within human society. These oughts emerge from the prior is. We may see this as mysterious, perhaps, but it is not complicated. We are all acting out strategies for living that seek out what I have termed a Darwinian Mean between desire and values.

Some of the most recent attempts are from Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris and Daniel Dennett, collectively known as the Four Horsemen of New Atheism. In particular, Sam Harris wrote The Moral Landscape, a Ph.D. thesis that was turned into a popular book, where he attempted to ground morality in neuroscience and an evaluation of the mental states of human beings. He posited that moral action is anything that promotes human flourishing as defined by the allegedly factual self-reporting of each person’s well-being. Harris’ work was criticised by both religious and atheist people. Harris called for a competition of essays critiquing the book and the winning essay was posted on his blog. Many critical responses state that Harris never escapes the problem of deriving an “ought” from an “is”.

My claim is that Sam and others fail because they seek to ground values in language when in fact they emerge prior to language. That said, to explore the nature of morality via self-reporting of well being is an interesting idea. Psychological well being could plausibly be a signal of what one might call social homeostasis, in the same way as good health is a signal of biological homeostasis. I believe that the “value of values” is to support social homeostasis, the well being of the group, and that is why they emerged among social animals (and not among asocial ones).

It appears to me that Moore’s work falls into the same chasm. The “turn” in Chapter 6 is jarring. After having extolled the benefits of Transcendental Meditation as providing easily accessible spiritual support, Moore goes on to ground goodness in a series of archetypes found in society: maternal love, paternal love, sibling love and communal friendship. Moore also defines a way of measuring goodness, a sort of set of KPIs: Is Good, Feels Good, Works Good.

It is a bit humbling to have one’s ideas summarized so baldly, but Bill has me exactly right.

These proposals have several problems. First of all, they are not universal, rather they are very culturally specific. Moore may provide evidence that many animal species exhibit these archetypes and a certain level of ethical behavior that is beneficial to the species, but there is nothing that shows that all human cultures across the world do.

Here Bill and I part company. Yes, any given set of values are culturally specific—indeed, they have to be if they are to serve the community that embraces them. But values per se are universal, at least among mammals. Thus, when it comes to maternal values, for example, all mammals nurture their young. That is a universal value. It is not negotiable. There is no viable human culture that does not commit to it. Sadly, there was a famously horrific societal experiment conducted in Romania during the 1950s in which a generation of infants were not nurtured, and the results were predictably catastrophic. The same holds for the other values I cite. They all have different manifestations, but since they are mammalian in origin, and since all humans are mammals, they are universal.

Secondly, Moore’s measure of goodness never manages to distinguish itself from moral relativism.

That is because Moore does not want to distinguish goodness from moral relativism! Moral absolutism, to my mind, causes much more societal damage than moral relativism. This is my biggest beef with religion. I love the values, but I do not support the absolutism. It is a human invention that is designed to confer power onto selected individuals, too many of whom have shown a propensity to abuse that power.

Thirdly, while all of this may be nice, and I would love for more people to aspire to many of the ideals that Moore provides, there is little to no argument as to why anyone must buy into it. There is nothing compelling enough to stop a genocidal maniac and his followers from truly believing that their race is better than others.

I agree with Bill. Nothing I say is compelling enough to stop a genocidal maniac. But there is more to it than that. Implicit in his critique is the idea that a proper morality would supply such an argument, and this is where we really do part company.

The conventional view of morality is that it can be captured in a moral code, and that where that code is authorized, proper moral judgment is based on applying it to the situation at hand. This implies that morality comes from above, a product of applying analytics to metaphysics to determine the right way to act. My position is the exact opposite. I claim that morality comes from below, from our mammalian heritage, and our moral sense is initially non-verbal, only later to be rationalized. In other words, we know the difference between right and wrong not through the application of reason but rather through our intuitive assessment of behavior based on the social norms we were raised with. Bill wants something more definitive than that, and I don’t blame him. I just don’t think it exists. Worse, when people insist on asserting such claims as absolute, they have the capacity to generate genocides of their own, genocides in the name of all that is holy. It is a travesty, to be sure, but it is not an unfamiliar one.

Mortality driving behavior

In fact, Moore seems to undermine his own premise when bringing mortality into the equation.

Mortality, like immortality, sets the ultimate context for ethics. Whereas belief in immortality typically implies an ethic of ultimate obedience, belief in mortality typically aligns with a journey of self-realization.

Mortality is the ultimate statute of limitations on behavior. While this isn’t entirely true, since many people care about the future of the loved ones they will leave behind, I agree with the statement in general. Mortality reduces the consequences of one’s actions and therefore provides less urgency to fully comply with any ethical framework. Mortality does however seem to push people to think about what they will leave behind and to seek self-realization, a potentially selfish pursuit.

Bill and I do not see mortality through the same lens. I do not see it as a statute of limitations on behavior. I see it as the fundamental enabler of our existence. Evolution is based on natural selection which in turn is powered by mortality. Without death, there is no evolution, hence no you, no me, nor anyone or anything else we love.

But set all that aside, and I still will argue that mortality if foundational to our identity. Death makes life precious. It also positions us in relation to an enterprise far greater than ourselves, one that precedes our arrival and will continue on long after we are gone. Our identity is tied to our participation in this enterprise, enabled by the narratives which our culture has transmitted to us. The only question is, how we will enact our participation, and to what end. That is where ethics comes in.

Self-realization is not selfish. Ego-realization is selfish. This is where mindfulness and meditation come in. These practices allow consciousness to experience self as connected to a source of spiritual connection and refreshment, thereby giving the ego the energy and centeredness it needs to act ethically under challenging conditions.

On the other hand, immortality doesn’t necessarily carry with it a moral imperative. In order for that, one must believe in some force that will ensure that all immoral behavior will eventually and inescapably lead to unwanted consequences.

Logically, this makes sense, but I have never heard of an immortality narrative that did not incorporate some form of divine judgment.

Genes and memes

There is not much to say about Moore’s reference to Richard Dawkins’ concept of memes. Meme theory and memetics have been heavily criticised by experts from many different fields. For instance, Dr Luis Benitez-Bribiesca pointed to various differences between genes and memes including the high rate of mutation, the lack of a code script, and instability. For this reason memes cannot account for the observed emergence of common narratives and culture.

Sorry, but I am not willing to cede the field here. My claim is that memes are like genes in the following ways:

Both encode strategies for living that are communicated across generations, the one biologically, the other socially. Both are subject to natural selection, leading to the spread of increasingly successful strategies for living while weeding out the unsuccessful ones.Both are also subject to sexual selection, leading to the spread of increasingly appealing strategies for living while weeding out the unattractive ones.Now, as to the objections raised by Dr. Benitex-Bribiesca, here are my replies:

There is no clear-cut definition of a meme. I claim that memes are properly defined as strategies for living that inform behaviors and are spread through imitation—something we can see emerging in social animals but made fully manifest with the arrival of language.Memes cannot be subjected to rigorous scientific investigation because they are too heterogenous to study in a systematic way. I claim that there are a number of widely disseminated academic disciplines devoted entirely to the study of memes, of which history, philosophy, and literary studies are three.The mutation of memes is unconstrained in ways that are so different from genes that the metaphor is not useful. I agree that the mechanisms for transmission are quite different. But both are ultimately selected for or against based on the behavior of the organism enacting the strategy. To be sure, each individual embracing a given strategy will put their individual spin on it—that’s the source of mutation. Some of these mutations will have more success either in propagating (winning the war of sexual selection) or succeeding (winning the war of natural selection)—that’s what leads to the evolution of increasingly complex and inclusive strategies for living, the sciences being a particularly impressive example thereof.Memetics is nothing more than pseudoscientific dogma encased in itself. Frankly, this is just name-calling. Still, to be fair, I agree that memetics is not a science, certainly not in the way that genetics is. I believe, however, it is can be useful to describe forces that act on human beings, to develop an understanding of the opportunities and threats they pose, and to propose tactics for capitalizing on the former and defending oneself against the latter.Given the above, I think it is wrong to say that memes cannot account for the observed emergence of common narratives and culture.

Epigenetics provide a more coherent description of how culture is inherited. Linguistics, complex systems theory and the works of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari provide better explanations for how narratives propagate and influence culture.

I am not familiar with this body of work, but I expect I would find it congenial. I am not seeking to proselytize memetics per se. I do think they are a useful vehicle for understanding the impact of narratives and analytics on human experience, and I take that to be the reason they generate so much analysis.

Religion fails as a grounds for moral behavior

Peppered throughout the book there are jabs at religion’s alleged shortcomings to provide suitable grounds for ethics.

This is the only comment in this entire dialog that I truly take exception to. I make the point several times throughout The Infinite Staircase that religion is indeed very well suited to authorize ethics and that committing to a religious tradition is a time-tested way to living an ethical life. My issue is that I do not find the metaphysics embedded in religious narratives credible. The story is compelling, but the evidence is missing. On the other hand, I find secular metaphysics to be very credible. Here there is a surprising amount of consensus across a broad range of evidence. The challenge is that secular metaphysics do not authorize ethics anywhere near as clearly or effectively as religion does. That’s why I wrote the book. I hold that the function of ethics is to align human behavior with metaphysics, and I seek to build that connection as best I can.

Most of these arguments use The Great Chain of Being as a strawman. Others are a weak form of the problem of evil that many have countered, including William Lane Craig and Tim Keller. A few are easily pushed aside by exploiting gaping holes in the Staircase. For instance, Moore states that the Staircase removes the need for a God to explain the universe, yet he never proves that God could never be encountered at either end of the Infinite Staircase, nor does he answer the question of why the laws of physics, chemistry, biology etc. are the way they are and not something else. This question seems to be swept under the rug of emergentism, which is arguably insufficient. The theory of evolution had this problem for many years, because many traits seemed to have evolved too quickly. The concept of exaptation, the process under which a trait that evolved for one purpose is radically repurposed for another, was the key to solving this problem. Still, this does not solve the problem of why the constants that appear in the laws of physics are so fine-tuned. Small variations in these constants would not have permitted any order to arise in the universe. Many scientists have attempted to solve this, some by positing that our universe is one of many in a multi-verse, each universe a different set of physical laws. Also, while physics describes much of what happened since the Big Bang, it says nothing of what happened before. This was Stephen Hawking’s nemesis. After having shown that the universe started as a singularity, or black hole, he spent a good part of the rest of his life coming up with various theories about what caused the Big Bang without relying on the super-natural.

The paragraph above, to my mind, is unnecessarily belligerent. Removing the need for a God to explain the universe need not be taken as an attack on the validity of religious faith. I would position it instead as exploring the possibility of exploring life from a radically different perspective. I do not think it is possible to prove there is no God—how do you prove a negative? We are better served if we seek to advance the case for whatever positive captures our allegiance.

As for why all the laws are as they are, and why key constants are tuned so precisely to support order to arise in the universe, I support the argument from anthropomorphism that says things have to be as they are or we would not be having this conversation. As for the claim that evolution is flawed because many traits seemed to have evolved too quickly, that implies all innovation must unfold linearly, that course-correcting through exaptation is improbable, that an exponential rate of change is not possible, all assertions that advocate for punctuated equilibrium would take exception to. As for multiverses, I find one universe far more than I can comprehend—I have no interest in taking on more than one. Ditto for what happened before the Big Bang—I don’t even have a placeholder for what caused that, nor do I believe we need one.

In fact, the existence of God and the veracity of the Bible form a very simple and coherent grounding for ethics. Goodness is based on God’s nature revealed by his actions and commands. Every human has fallen short, yet Jesus’ sacrifice and resurrection assure the salvation of all who believe. The only thing lacking is incontrovertible proof of the premises.

Despite all the disagreement Bill and I have about metaphysics, I support him in the above paragraph. At the end of the day, the point is not who is right or wrong about the nature of the universe, the point is to live an ethical life. This is no easy task, and we all fall short in one way or another. We need spiritual support to keep on going. Religious faith may lack incontrovertible proof of its premises, but it sure has a heck of a track record, and it would be foolish to repudiate it.

Conclusion

All in all, the first two-thirds of Moore’s book are very interesting but the final third falls short. The construction of the Infinite Staircase is compelling. Apart from the reference to meme theory, there is a trove of information to be dug into. The inclusion of values, culture and narrative in the staircase is an important one. Narrative is a powerful, misunderstood and underused tool for corporate and societal change. John Seely Brown said that “we have moved from the age of enlightenment to the age of entanglement.” The turn towards deriving ethics falls flat. Many of the proposed ideals are commendable but remain wishful thinking and are culturally specific.

As a former academic, I am deeply committed to the marketplace of ideas and the kinds of dialog that make it work. I am honored that Bill has taken my book seriously, and I hope this exchange will be of value to both of our readerships.

Geoffrey Moore

Starting the Dialogue: Discussing the Infinite Staircase via Book Review

In his review of The Infinite Staircase, Bill Bartlett has done me the honor every author most cherishes—he has read my book thoughtfully and has engaged directly with its claims. He and I don’t see eye to eye on many of these claims, but we both have deep respect for Western philosophy and religion, so I welcome the opportunity to do a kind of Point/Counterpoint with his review. In this context, I am reproducing what he says first and then interspersing my commentary in a different font color. Here goes.

Book Review: The Infinite Staircase

Book Review: The Infinite Staircase

When I first came across The Infinite Staircase, I was intrigued for two reasons: The title suggested that the book was not in the same vein as the author’s previous work and that it would tackle morality from a secular viewpoint. As such the title was extremely well chosen.

The Infinite Staircase is the latest from Geoffrey Moore, who is famous for books such as Crossing the Chasm and Zone to Win, which I quote quite frequently when talking about product management. It is a departure from those books as it deals with the strategy for something larger than products and companies: life itself. It attempts to give a description of the universe and human life in it, and then derive from that a framework for grounding ethics and morality. Moore remarks that the world is becoming less and less religious which is eroding the foundations that fostered ethical behavior. Moore sees the need for a secular foundation in order to regain the stability that society needs and that ethics provides.

I don’t want to quarrel with this representation, but I do think it is a bit one-sided when it comes to my commitment to a secular metaphysics. I am blown away by the magnitude and wonder that the secular story of creation tells. The fact that humanity has been able to develop such a complete and verifiable explanation of how we got from a Big Bang to the present day astounds me. So, I do not want to set it aside when it comes to establishing the grounds for ethical behavior. It is not, in other words, that I am disappointed with religion, although I do take it to task from time to time, but rather that I am unwilling to sideline what I consider to be some of humanity’s best work when it comes to tackling issues of spiritual and moral importance.

Moore’s proposed foundation for ethics is the various sciences which he places on consecutive steps of a staircase. Each stair emerges out of the previous one: it is constrained by the previous stair but not wholly predicted by it. For example, chemistry emerges from physics because physics applies a constraint on what chemical entities can do without being able to predict every behavior that they have. It is a shame that Moore does not explain the concept of emergence and assumes the reader is familiar with it. I myself was skeptical that chemistry emerges from physics and was glad to be able to find a well-researched article on the subject.

I confess to being guilty as charged here. I am in awe of emergence and how it generates complexity, and it certainly deserves a strong foundation. In the bibliography of The Infinite Staircase, I do reference some works on the topic, of which I think John Holland’s Complexity: A Short Introduction is the best one to start with.

Because of emergence, there is no single science that completely describes and predicts everything in the universe. Therefore any unifying theory must contain all of them. In fact, it must contain many other sciences, some of which have not been explored yet. Hence the fact that the staircase is assumed to be infinite in both directions. In spite of this, Moore feels that we have enough of a grasp on the “middle” of the infinite staircase in order to ground ethics.

In fact, Moore focuses on a smaller subset of the staircase he describes by stating that goodness begins with desire. This is surprising given that many points of contention in today’s society have a biological component.

Unfortunately, Moore’s proposed framework for ethics is flawed for several reasons that I would like to discuss.

Deriving an “ought” from an “is”

From the beginning, Moore had his work cut out for him. Many have tried and failed to do what Moore attempts, that is to ground a theory of what ought to be in a theory of what can be. Many philosophers have weighed in on this problem. David Hume is famously credited for suggesting that one cannot derive an “ought” from an “is”. Jean-Paul Sartre, quoting Dostoevsky, affirmed that since God does not exist, anything is justifiable.

the distinction of vice and virtue is not founded merely on the relations of objects, nor is perceived by reason.

— David Hume. A Treatise of Human Nature (1739)

Bill is correct that I do believe you can derive an ought from an is, that this is an important objective for the book, and that it does put me at odds with Messers Hume, Sartre, and Dostoevsky. My claim is that consciousness emerges from desire (this aligns with Hume’s famous comment that reason is in service to, and not the master of, the passions). I take this relationship between desire and consciousness to establish the is. Desire is driving behavior, and we have no choice in that matter. We are compelled to desire. The vehicle we are riding on is irresistibly in motion—all we can do is seek to steer it.

That’s where values come in. They emerge from conscious beings interacting socially with one another, specifically within the context of raising families and interacting with neighbors, something we can see in higher order mammals who nurture their young, discipline their peers, court their mates, and defend their group. All four of these behavioral domains entail oughts, even among pre-linguistic animals, and certainly within human society. These oughts emerge from the prior is. We may see this as mysterious, perhaps, but it is not complicated. We are all acting out strategies for living that seek out what I have termed a Darwinian Mean between desire and values.

Some of the most recent attempts are from Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris and Daniel Dennett, collectively known as the Four Horsemen of New Atheism. In particular, Sam Harris wrote The Moral Landscape, a Ph.D. thesis that was turned into a popular book, where he attempted to ground morality in neuroscience and an evaluation of the mental states of human beings. He posited that moral action is anything that promotes human flourishing as defined by the allegedly factual self-reporting of each person’s well-being. Harris’ work was criticised by both religious and atheist people. Harris called for a competition of essays critiquing the book and the winning essay was posted on his blog. Many critical responses state that Harris never escapes the problem of deriving an “ought” from an “is”.

My claim is that Sam and others fail because they seek to ground values in language when in fact they emerge prior to language. That said, to explore the nature of morality via self-reporting of well being is an interesting idea. Psychological well being could plausibly be a signal of what one might call social homeostasis, in the same way as good health is a signal of biological homeostasis. I believe that the “value of values” is to support social homeostasis, the well being of the group, and that is why they emerged among social animals (and not among asocial ones).

It appears to me that Moore’s work falls into the same chasm. The “turn” in Chapter 6 is jarring. After having extolled the benefits of Transcendental Meditation as providing easily accessible spiritual support, Moore goes on to ground goodness in a series of archetypes found in society: maternal love, paternal love, sibling love and communal friendship. Moore also defines a way of measuring goodness, a sort of set of KPIs: Is Good, Feels Good, Works Good.

It is a bit humbling to have one’s ideas summarized so baldly, but Bill has me exactly right.

These proposals have several problems. First of all, they are not universal, rather they are very culturally specific. Moore may provide evidence that many animal species exhibit these archetypes and a certain level of ethical behavior that is beneficial to the species, but there is nothing that shows that all human cultures across the world do.

Here Bill and I part company. Yes, any given set of values are culturally specific—indeed, they have to be if they are to serve the community that embraces them. But values per se are universal, at least among mammals. Thus, when it comes to maternal values, for example, all mammals nurture their young. That is a universal value. It is not negotiable. There is no viable human culture that does not commit to it. Sadly, there was a famously horrific societal experiment conducted in Romania during the 1950s in which a generation of infants were not nurtured, and the results were predictably catastrophic. The same holds for the other values I cite. They all have different manifestations, but since they are mammalian in origin, and since all humans are mammals, they are universal.

Secondly, Moore’s measure of goodness never manages to distinguish itself from moral relativism.

That is because Moore does not want to distinguish goodness from moral relativism! Moral absolutism, to my mind, causes much more societal damage than moral relativism. This is my biggest beef with religion. I love the values, but I do not support the absolutism. It is a human invention that is designed to confer power onto selected individuals, too many of whom have shown a propensity to abuse that power.

Thirdly, while all of this may be nice, and I would love for more people to aspire to many of the ideals that Moore provides, there is little to no argument as to why anyone must buy into it. There is nothing compelling enough to stop a genocidal maniac and his followers from truly believing that their race is better than others.

I agree with Bill. Nothing I say is compelling enough to stop a genocidal maniac. But there is more to it than that. Implicit in his critique is the idea that a proper morality would supply such an argument, and this is where we really do part company.

The conventional view of morality is that it can be captured in a moral code, and that where that code is authorized, proper moral judgment is based on applying it to the situation at hand. This implies that morality comes from above, a product of applying analytics to metaphysics to determine the right way to act. My position is the exact opposite. I claim that morality comes from below, from our mammalian heritage, and our moral sense is initially non-verbal, only later to be rationalized. In other words, we know the difference between right and wrong not through the application of reason but rather through our intuitive assessment of behavior based on the social norms we were raised with. Bill wants something more definitive than that, and I don’t blame him. I just don’t think it exists. Worse, when people insist on asserting such claims as absolute, they have the capacity to generate genocides of their own, genocides in the name of all that is holy. It is a travesty, to be sure, but it is not an unfamiliar one.

Mortality driving behavior

In fact, Moore seems to undermine his own premise when bringing mortality into the equation.

Mortality, like immortality, sets the ultimate context for ethics. Whereas belief in immortality typically implies an ethic of ultimate obedience, belief in mortality typically aligns with a journey of self-realization.

Mortality is the ultimate statute of limitations on behavior. While this isn’t entirely true, since many people care about the future of the loved ones they will leave behind, I agree with the statement in general. Mortality reduces the consequences of one’s actions and therefore provides less urgency to fully comply with any ethical framework. Mortality does however seem to push people to think about what they will leave behind and to seek self-realization, a potentially selfish pursuit.

Bill and I do not see mortality through the same lens. I do not see it as a statute of limitations on behavior. I see it as the fundamental enabler of our existence. Evolution is based on natural selection which in turn is powered by mortality. Without death, there is no evolution, hence no you, no me, nor anyone or anything else we love.

But set all that aside, and I still will argue that mortality if foundational to our identity. Death makes life precious. It also positions us in relation to an enterprise far greater than ourselves, one that precedes our arrival and will continue on long after we are gone. Our identity is tied to our participation in this enterprise, enabled by the narratives which our culture has transmitted to us. The only question is, how we will enact our participation, and to what end. That is where ethics comes in.

Self-realization is not selfish. Ego-realization is selfish. This is where mindfulness and meditation come in. These practices allow consciousness to experience self as connected to a source of spiritual connection and refreshment, thereby giving the ego the energy and centeredness it needs to act ethically under challenging conditions.

On the other hand, immortality doesn’t necessarily carry with it a moral imperative. In order for that, one must believe in some force that will ensure that all immoral behavior will eventually and inescapably lead to unwanted consequences.

Logically, this makes sense, but I have never heard of an immortality narrative that did not incorporate some form of divine judgment.

Genes and memes

There is not much to say about Moore’s reference to Richard Dawkins’ concept of memes. Meme theory and memetics have been heavily criticised by experts from many different fields. For instance, Dr Luis Benitez-Bribiesca pointed to various differences between genes and memes including the high rate of mutation, the lack of a code script, and instability. For this reason memes cannot account for the observed emergence of common narratives and culture.

Sorry, but I am not willing to cede the field here. My claim is that memes are like genes in the following ways:

Both encode strategies for living that are communicated across generations, the one biologically, the other socially. Both are subject to natural selection, leading to the spread of increasingly successful strategies for living while weeding out the unsuccessful ones.Both are also subject to sexual selection, leading to the spread of increasingly appealing strategies for living while weeding out the unattractive ones.Now, as to the objections raised by Dr. Benitex-Bribiesca, here are my replies:

There is no clear-cut definition of a meme. I claim that memes are properly defined as strategies for living that inform behaviors and are spread through imitation—something we can see emerging in social animals but made fully manifest with the arrival of language.Memes cannot be subjected to rigorous scientific investigation because they are too heterogenous to study in a systematic way. I claim that there are a number of widely disseminated academic disciplines devoted entirely to the study of memes, of which history, philosophy, and literary studies are three.The mutation of memes is unconstrained in ways that are so different from genes that the metaphor is not useful. I agree that the mechanisms for transmission are quite different. But both are ultimately selected for or against based on the behavior of the organism enacting the strategy. To be sure, each individual embracing a given strategy will put their individual spin on it—that’s the source of mutation. Some of these mutations will have more success either in propagating (winning the war of sexual selection) or succeeding (winning the war of natural selection)—that’s what leads to the evolution of increasingly complex and inclusive strategies for living, the sciences being a particularly impressive example thereof.Memetics is nothing more than pseudoscientific dogma encased in itself. Frankly, this is just name-calling. Still, to be fair, I agree that memetics is not a science, certainly not in the way that genetics is. I believe, however, it is can be useful to describe forces that act on human beings, to develop an understanding of the opportunities and threats they pose, and to propose tactics for capitalizing on the former and defending oneself against the latter.Given the above, I think it is wrong to say that memes cannot account for the observed emergence of common narratives and culture.

Epigenetics provide a more coherent description of how culture is inherited. Linguistics, complex systems theory and the works of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari provide better explanations for how narratives propagate and influence culture.

I am not familiar with this body of work, but I expect I would find it congenial. I am not seeking to proselytize memetics per se. I do think they are a useful vehicle for understanding the impact of narratives and analytics on human experience, and I take that to be the reason they generate so much analysis.

Religion fails as a grounds for moral behavior

Peppered throughout the book there are jabs at religion’s alleged shortcomings to provide suitable grounds for ethics.

This is the only comment in this entire dialog that I truly take exception to. I make the point several times throughout The Infinite Staircase that religion is indeed very well suited to authorize ethics and that committing to a religious tradition is a time-tested way to living an ethical life. My issue is that I do not find the metaphysics embedded in religious narratives credible. The story is compelling, but the evidence is missing. On the other hand, I find secular metaphysics to be very credible. Here there is a surprising amount of consensus across a broad range of evidence. The challenge is that secular metaphysics do not authorize ethics anywhere near as clearly or effectively as religion does. That’s why I wrote the book. I hold that the function of ethics is to align human behavior with metaphysics, and I seek to build that connection as best I can.

Most of these arguments use The Great Chain of Being as a strawman. Others are a weak form of the problem of evil that many have countered, including William Lane Craig and Tim Keller. A few are easily pushed aside by exploiting gaping holes in the Staircase. For instance, Moore states that the Staircase removes the need for a God to explain the universe, yet he never proves that God could never be encountered at either end of the Infinite Staircase, nor does he answer the question of why the laws of physics, chemistry, biology etc. are the way they are and not something else. This question seems to be swept under the rug of emergentism, which is arguably insufficient. The theory of evolution had this problem for many years, because many traits seemed to have evolved too quickly. The concept of exaptation, the process under which a trait that evolved for one purpose is radically repurposed for another, was the key to solving this problem. Still, this does not solve the problem of why the constants that appear in the laws of physics are so fine-tuned. Small variations in these constants would not have permitted any order to arise in the universe. Many scientists have attempted to solve this, some by positing that our universe is one of many in a multi-verse, each universe a different set of physical laws. Also, while physics describes much of what happened since the Big Bang, it says nothing of what happened before. This was Stephen Hawking’s nemesis. After having shown that the universe started as a singularity, or black hole, he spent a good part of the rest of his life coming up with various theories about what caused the Big Bang without relying on the super-natural.

The paragraph above, to my mind, is unnecessarily belligerent. Removing the need for a God to explain the universe need not be taken as an attack on the validity of religious faith. I would position it instead as exploring the possibility of exploring life from a radically different perspective. I do not think it is possible to prove there is no God—how do you prove a negative? We are better served if we seek to advance the case for whatever positive captures our allegiance.

As for why all the laws are as they are, and why key constants are tuned so precisely to support order to arise in the universe, I support the argument from anthropomorphism that says things have to be as they are or we would not be having this conversation. As for the claim that evolution is flawed because many traits seemed to have evolved too quickly, that implies all innovation must unfold linearly, that course-correcting through exaptation is improbable, that an exponential rate of change is not possible, all assertions that advocate for punctuated equilibrium would take exception to. As for multiverses, I find one universe far more than I can comprehend—I have no interest in taking on more than one. Ditto for what happened before the Big Bang—I don’t even have a placeholder for what caused that, nor do I believe we need one.

In fact, the existence of God and the veracity of the Bible form a very simple and coherent grounding for ethics. Goodness is based on God’s nature revealed by his actions and commands. Every human has fallen short, yet Jesus’ sacrifice and resurrection assure the salvation of all who believe. The only thing lacking is incontrovertible proof of the premises.

Despite all the disagreement Bill and I have about metaphysics, I support him in the above paragraph. At the end of the day, the point is not who is right or wrong about the nature of the universe, the point is to live an ethical life. This is no easy task, and we all fall short in one way or another. We need spiritual support to keep on going. Religious faith may lack incontrovertible proof of its premises, but it sure has a heck of a track record, and it would be foolish to repudiate it.

Conclusion

All in all, the first two-thirds of Moore’s book are very interesting but the final third falls short. The construction of the Infinite Staircase is compelling. Apart from the reference to meme theory, there is a trove of information to be dug into. The inclusion of values, culture and narrative in the staircase is an important one. Narrative is a powerful, misunderstood and underused tool for corporate and societal change. John Seely Brown said that “we have moved from the age of enlightenment to the age of entanglement.” The turn towards deriving ethics falls flat. Many of the proposed ideals are commendable but remain wishful thinking and are culturally specific.

As a former academic, I am deeply committed to the marketplace of ideas and the kinds of dialog that make it work. I am honored that Bill has taken my book seriously, and I hope this exchange will be of value to both of our readerships.

Geoffrey Moore

May 8, 2022

Testing for Truth

It is more than commonplace these days to lament that truth has become a casualty of our digital era. It is also baloney. There are clear tests for truth that have served humankind for centuries, and there is no reason to abandon them now. We just need to bring them back into focus.

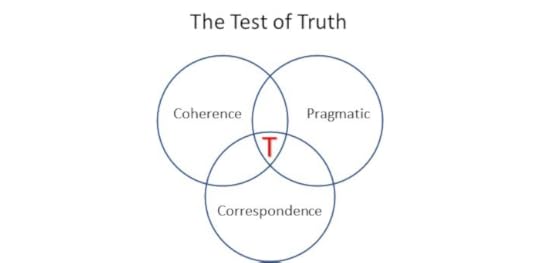

Among philosophers there are three broad schools of truth, each foregrounding a different attribute, as follows:

The Correspondence theory of truth, which says that if a statement can be verified by a large number of observations undertaken by a diverse population of observers, then it is true. Water boils at 100 degrees centigrade at sea level.The Coherence theory of truth, which says that if a statement is consistent with one’s time-tested system of beliefs, then it is true. Pigs cannot fly.The Pragmatic theory of truth, which says that if a statement enables successful action in the world, then it is true. Wikipedia is a trustworthy source of information.Unfortunately, any one of these theories of truth can be co-opted by the forces of disinformation. Thus, by selecting a small number of observations that have been pre-selected to back up your claim, you can assert correspondence truth because these facts do indeed correspond to the claim. Similarly, by creating a conspiracy theory and recruiting people who are predisposed to want to believe it, you can assert coherence truth because your claims are indeed consistent with the theory. And finally, if you are able to use whatever claims you make to get elected to public office, then you can assert pragmatic truth because you were indeed successful in winning the election.

It is much harder, on the other hand, to subvert an integrated understanding of truth that combines all three schools into one battery of tests:

As represented by this Venn diagram, the area where all three circles overlap represents our best testing ground for truth. That is, to be reliably true, a claim must be correspondent, coherent, and pragmatic—and not, which two do you want?

Let us apply this test to the claim that the 2020 election was stolen from Donald Trump. For people who believe in the relevant conspiracy theories, this claim is completely coherent. However, it is neither correspondent nor pragmatic. That is, there has been little if any credible evidence produced in support of the claim, and over fifty state and federal judges have dismissed lawsuits filed in support of it. We can say with confidence therefore that the claim is untrue.

A similar approach can be taken to claims that the Covid vaccine is too dangerous to be used. Again, this is based on a coherence theory of truth anchored in political or metaphysical narratives that are deeply compelling to its proponents. They believe this to be true, and they are acting accordingly. However, from a correspondence theory perspective, after two and a half years, there is overwhelming evidence that the vaccine is safe to administer. And from a pragmatic perspective, there is tragic mortality data testifying to the fates of those who were not vaccinated. Again, we can say with confidence that the claim that the vaccine is too dangerous to use is untrue.

Truth, however, can be decidedly unpopular, so there will always be strong social pressures to acquiesce to alternative claims, which, while untrue, are more palatable. Such pressures play into the hands of the autocratic and the righteous across the entirety of the political spectrum. This is not a new challenge. Demagogues and dictators have played this game throughout history. And history teaches us that allowing such people to exploit their narratives without contradiction undermines the rule of law and the foundations of liberal democracy. Today, as Americans, we are privileged to live under rule of law, but much as we would like it to be, that does not make it an entitlement. Rather it is a freedom we must commit to preserving. As citizens, therefore, regardless of party or persuasion, we must make ourselves competent in the tests for truth and ensure that our children are well trained in them as well. That’s what I think. What do you think?

Testing for Truth

It is more than commonplace these days to lament that truth has become a casualty of our digital era. It is also baloney. There are clear tests for truth that have served humankind for centuries, and there is no reason to abandon them now. We just need to bring them back into focus.

Among philosophers there are three broad schools of truth, each foregrounding a different attribute, as follows:

The Correspondence theory of truth, which says that if a statement can be verified by a large number of observations undertaken by a diverse population of observers, then it is true. Water boils at 100 degrees centigrade at sea level.The Coherence theory of truth, which says that if a statement is consistent with one’s time-tested system of beliefs, then it is true. Pigs cannot fly.The Pragmatic theory of truth, which says that if a statement enables successful action in the world, then it is true. Wikipedia is a trustworthy source of information.Unfortunately, any one of these theories of truth can be co-opted by the forces of disinformation. Thus, by selecting a small number of observations that have been pre-selected to back up your claim, you can assert correspondence truth because these facts do indeed correspond to the claim. Similarly, by creating a conspiracy theory and recruiting people who are predisposed to want to believe it, you can assert coherence truth because your claims are indeed consistent with the theory. And finally, if you are able to use whatever claims you make to get elected to public office, then you can assert pragmatic truth because you were indeed successful in winning the election.

It is much harder, on the other hand, to subvert an integrated understanding of truth that combines all three schools into one battery of tests:

As represented by this Venn diagram, the area where all three circles overlap represents our best testing ground for truth. That is, to be reliably true, a claim must be correspondent, coherent, and pragmatic—and not, which two do you want?

Let us apply this test to the claim that the 2020 election was stolen from Donald Trump. For people who believe in the relevant conspiracy theories, this claim is completely coherent. However, it is neither correspondent nor pragmatic. That is, there has been little if any credible evidence produced in support of the claim, and over fifty state and federal judges have dismissed lawsuits filed in support of it. We can say with confidence therefore that the claim is untrue.

A similar approach can be taken to claims that the Covid vaccine is too dangerous to be used. Again, this is based on a coherence theory of truth anchored in political or metaphysical narratives that are deeply compelling to its proponents. They believe this to be true, and they are acting accordingly. However, from a correspondence theory perspective, after two and a half years, there is overwhelming evidence that the vaccine is safe to administer. And from a pragmatic perspective, there is tragic mortality data testifying to the fates of those who were not vaccinated. Again, we can say with confidence that the claim that the vaccine is too dangerous to use is untrue.

Truth, however, can be decidedly unpopular, so there will always be strong social pressures to acquiesce to alternative claims, which, while untrue, are more palatable. Such pressures play into the hands of the autocratic and the righteous across the entirety of the political spectrum. This is not a new challenge. Demagogues and dictators have played this game throughout history. And history teaches us that allowing such people to exploit their narratives without contradiction undermines the rule of law and the foundations of liberal democracy. Today, as Americans, we are privileged to live under rule of law, but much as we would like it to be, that does not make it an entitlement. Rather it is a freedom we must commit to preserving. As citizens, therefore, regardless of party or persuasion, we must make ourselves competent in the tests for truth and ensure that our children are well trained in them as well. That’s what I think. What do you think?

April 27, 2022

Some Inflection Points in the Philosophy of Mind

This post, like those that precede it, is based on reacting to an article that one way or another has captured my imagination. In this case, the article was actually about Artificial Intelligence and whether it could really be called intelligence or not. What interested me, however, was the way it organized itself around a set of philosophical positions that evolved historically. What I have done, therefore, is to cut and paste those bits in order to create a context for discussing my own philosophy of mind. This is, of course, totally unfair to the authors of the article, hence I post a link at the end where you can go read their work for its own sake. For the time being, however, please bear with my approach, at least long enough to see if you think it bears any fruit.

The 17th-century French philosopher René Descartes was combating materialism, which explains the world, and everything in it, as entirely made up of matter.[2] Descartes separated the mind and body to create a neutral space to discuss nonmaterial substances like consciousness, the soul, and even God. This philosophy of the mind was named cartesian dualism.[3]

Dualism argues that the body and mind are not one thing but separate and opposite things made of different matter that inexplicitly interact.[4] Descartes’s methodology to doubt everything, even his own body, in favor of his thoughts, to find something “indubitable,” which he encapsulated in his famous dictum Cogito, ergo sum, I think, therefore I am.

Where Descartes gets off track is in believing his mind to be independent of his social history. We know from the examples of feral children that without socialization, there is no language, there are no narratives, there are no analytics, and hence there is no mind. Because he was using words to communicate, words that he did not invent but were taught to him by his mother and others, what Descartes should have said was, I think, therefore we are.

Mind, in other words, emerges from brain under conditions of socialization. As described in The Infinite Staircase, consciousness comes into being with brain, whereas mind comes into being with language and narrative. Even though our mental experience is private, our mind is not. This touches on our very identity which can never be completely independent of our social situation. There simply can be no mind and no self, without social underpinnings. Thus, it is that mind can never be reduced to brain any more than life can be reduced to a handful of elements from the Periodic Table.

It wasn’t until the early 20th century that dualism was legitimately challenged.[6][7] So-called behaviorism argued that mental states could be reduced to physical states, which were nothing more than behavior.[8] Aside from the reductionism that results from treating humans as behaviors, the issue with behaviorism is that it ignores mental phenomena and explains the brain’s activity as producing a collection of behaviors that can only be observed. Concepts like thought, intelligence, feelings, beliefs, desires, and even hereditary genetics are eliminated in favor of environmental stimuli and behavioral responses.

Consequently, one can never use behaviorism to explain mental phenomena since the focus is on external observable behavior. Philosophers like to joke about two behaviorists evaluating their performance after sex: “It was great for you, how was it for me?” says one to the other.[9][10] By concentrating on the observable behavior of the body and not the origin of the behavior in the brain, behaviorism became less and less a source of knowledge about intelligence.

It is easy to patronize behaviorism, but we learn nothing by so doing. Instead, we should note first that behaviorism arose from a desire in the social sciences to become more like the physical sciences. It was specifically interested in coopting the latter’s ability to apply mathematics to measurable data as a means for expanding the domain of verifiable knowledge. That desire itself was prompted by a prior era’s unacknowledged reliance on narratives and anecdotes, especially in psychology, ethics, and metaphysics, all of which could be compelling, none of which could be conclusively tested. In such situations, research cannot build reliably upon prior findings, and so knowledge can only develop through dialectical disagreement as opposed to linear extrapolation. Thus, Newton could build upon Copernicus in ways that Aristotle could never build upon Plato.

The fatal flaw in behaviorism is that it is impossible to explain human behavior without reference to narrative. All societies convert their competence in language into storytelling, and the stories they tell are core to everyone’s self-understanding. These stories are simply too central to human affairs to eliminate as relevant data. To be fair, they may not be reliable sources of data about the topics they address, so instead, we need to treat them as data in and of themselves. That is, they may not accurately represent the phenomena they purport to describe, but they are nonetheless a force in the world they occupy, and for that reason, we need to include them if we are to gain a full understanding of what is going on around us.

Behaviorism saw a decline in influence that directly resulted in the inability to explain intelligence. It was displaced by a reorientation of psychology toward the brain dubbed the cognitive revolution. The revolution produced modern cognitive science, and functionalism became the new dominant theory of the mind. Functionalism views intelligence (i.e., mental phenomenon) as the brain’s functional organization where individuated functions like language and vision are understood by their causal roles.

Unlike behaviorism, functionalism focuses on what the brain does and where brain function happens.[16] However, functionalism is not interested in how something works or if it is made of the same material. It doesn’t care if the thing that thinks is a brain or if that brain has a body. If it functions like intelligence, it is intelligent like anything that tells time is a clock. It doesn’t matter what the clock is made of as long as it keeps time.

Functional organization is an important step forward because it aligns both brain and mind with strategies for living. All living beings manifest strategies for living—that’s what unites us all. One of the functions of language is that it enables us humans, through the mechanisms of narratives and analytics, to explore strategic possibilities, both in fictional and historical terms, and to critique them through analytics, using natural language and/or mathematics. It also allows us to engage and enlist others in our undertakings by communicating, both intellectually and emotionally, the strategic rewards of so doing. Functional organization, in this context, bridges the gap between private mental experience and public social interactions, both of which are required for intelligence to be operational in the world.

The American philosopher and computer scientist Hilary Putnam evolved functionalism in Psychological Predicates with computational concepts to form computational functionalism.[17][18] Computationalism, for short, views the mental world as grounded in a physical system (i.e., computer) using concepts such as information, computation (i.e., thinking), memory (i.e., storage), and feedback.[19][20][21] Today, artificial intelligence research relies heavily on computational functionalism, where intelligence is organized by functions such as computer vision and natural language processing and explained in computational terms.

Unfortunately, functions do not think. They are aspects of thought. The issue with functionalism — aside from the reductionism that results from treating thinking as a collection of functions (and humans as brains) — is that it ignores thinking. While the brain has localized functions with input–output pairs (e.g., perception) that can be represented as a physical system inside a computer, thinking is not a loose collection of localized functions.

The meaning of the word think in the paragraph above is unclear, and as a result, the rest of the paragraph does not lead to any useful conclusion. But there is another dimension of computational functionalism that is important to note: it is entirely analytic. Indeed, the whole of both AI and machine learning is entirely analytic. We need to ask ourselves, what might that be leaving out?

The short answer is, biochemistry. The analytic model of mental activity, with its embedded metaphor of computers and computing, is based entirely on electronic signaling. There are no hormones at work. But among living things, long before there were any nerves to carry sensory information, there were chemical signals that served the same end. Such signals circulate from cell to cell, activating receptors that, in turn, generate some response out of which behavior emerges, something we see every day in the way flowers turn to the sun or the way sleepiness takes over our minds.

Now, to be fair, you won’t survive very long as a mobile animal if you don’t have an electric nervous system, so we are talking about an and here, not an or. But it is an incredibly important and because biochemical signals are the mechanism by which homeostasis is maintained. Homeostasis is what the AI/ML models leave out. It is a big miss.

Homeostasis is a condition of equilibrium in which an organism is best fit to operate. All living things seek homeostasis all the time. Thus, both emotionally and intellectually, we humans are wired to seek it, and it shapes everything we do. Strategies for living, in this context, are simply mechanisms for achieving a more desirable condition of equilibrium, one in which we are better fit to operate. We can experience this phenomenon as desire or need or fear or hope, but by way of one emotion or another, we will be motivated to act. That is what separates human intelligence from all forms of computational functionalism.

John Searle’s famous Chinese Room thought experiment is one of the strongest attacks on computational functionalism. The former philosopher and professor at the University of California, Berkley, thought it impossible to build an intelligent computer because intelligence is a biological phenomenon that presupposes a thinker who has consciousness. This argument is counter to functionalism, which treats intelligence as realizable if anything can mimic the causal role of specific mental states with computational processes.

If you are not familiar with this thought experiment, click on the URL in the paragraph above before reading further. While Searle’s argument is correct as far as it goes, it is misleading because it does not honor the idea that a competence achieved without understanding could convert to true understanding at some later date. That is contradicted by many commonplace experiences. Think of the way you learn multiplication tables. You don’t need to understand why 8 X 6 = 48. You just have to memorize that it does. But sometime later on you do realize that a rectangle that is 8 inches on one side and 6 inches on the other actually does contain 48 square inches, and the world becomes a little less mysterious. Now, to be fair to Searle, this may be exactly his point, that the two are not the same, and I of course, would agree. But I would argue that the two are connected more closely than he implies. And that leads me to believe that a computationally functional system might be able to evolve future understanding from current competence by hypothesizing strategies and testing to see if they can be fulfilled by using the mechanisms it has already mastered. At minimum, I think AI and ML will eventually want to develop a philosophy of mind in order to take their discipline to the next level.

That’s what I think. What do you think? P.S. You can read the original article here .

Some Inflection Points in the Philosophy of Mind

This post, like those that precede it, is based on reacting to an article that one way or another has captured my imagination. In this case, the article was actually about Artificial Intelligence and whether it could really be called intelligence or not. What interested me, however, was the way it organized itself around a set of philosophical positions that evolved historically. What I have done, therefore, is to cut and paste those bits in order to create a context for discussing my own philosophy of mind. This is, of course, totally unfair to the authors of the article, hence I post a link at the end where you can go read their work for its own sake. For the time being, however, please bear with my approach, at least long enough to see if you think it bears any fruit.

The 17th-century French philosopher René Descartes was combating materialism, which explains the world, and everything in it, as entirely made up of matter.[2] Descartes separated the mind and body to create a neutral space to discuss nonmaterial substances like consciousness, the soul, and even God. This philosophy of the mind was named cartesian dualism.[3]

Dualism argues that the body and mind are not one thing but separate and opposite things made of different matter that inexplicitly interact.[4] Descartes’s methodology to doubt everything, even his own body, in favor of his thoughts, to find something “indubitable,” which he encapsulated in his famous dictum Cogito, ergo sum, I think, therefore I am.

Where Descartes gets off track is in believing his mind to be independent of his social history. We know from the examples of feral children that without socialization, there is no language, there are no narratives, there are no analytics, and hence there is no mind. Because he was using words to communicate, words that he did not invent but were taught to him by his mother and others, what Descartes should have said was, I think, therefore we are.

Mind, in other words, emerges from brain under conditions of socialization. As described in The Infinite Staircase, consciousness comes into being with brain, whereas mind comes into being with language and narrative. Even though our mental experience is private, our mind is not. This touches on our very identity which can never be completely independent of our social situation. There simply can be no mind and no self, without social underpinnings. Thus, it is that mind can never be reduced to brain any more than life can be reduced to a handful of elements from the Periodic Table.

It wasn’t until the early 20th century that dualism was legitimately challenged.[6][7] So-called behaviorism argued that mental states could be reduced to physical states, which were nothing more than behavior.[8] Aside from the reductionism that results from treating humans as behaviors, the issue with behaviorism is that it ignores mental phenomena and explains the brain’s activity as producing a collection of behaviors that can only be observed. Concepts like thought, intelligence, feelings, beliefs, desires, and even hereditary genetics are eliminated in favor of environmental stimuli and behavioral responses.

Consequently, one can never use behaviorism to explain mental phenomena since the focus is on external observable behavior. Philosophers like to joke about two behaviorists evaluating their performance after sex: “It was great for you, how was it for me?” says one to the other.[9][10] By concentrating on the observable behavior of the body and not the origin of the behavior in the brain, behaviorism became less and less a source of knowledge about intelligence.

It is easy to patronize behaviorism, but we learn nothing by so doing. Instead, we should note first that behaviorism arose from a desire in the social sciences to become more like the physical sciences. It was specifically interested in coopting the latter’s ability to apply mathematics to measurable data as a means for expanding the domain of verifiable knowledge. That desire itself was prompted by a prior era’s unacknowledged reliance on narratives and anecdotes, especially in psychology, ethics, and metaphysics, all of which could be compelling, none of which could be conclusively tested. In such situations, research cannot build reliably upon prior findings, and so knowledge can only develop through dialectical disagreement as opposed to linear extrapolation. Thus, Newton could build upon Copernicus in ways that Aristotle could never build upon Plato.

The fatal flaw in behaviorism is that it is impossible to explain human behavior without reference to narrative. All societies convert their competence in language into storytelling, and the stories they tell are core to everyone’s self-understanding. These stories are simply too central to human affairs to eliminate as relevant data. To be fair, they may not be reliable sources of data about the topics they address, so instead, we need to treat them as data in and of themselves. That is, they may not accurately represent the phenomena they purport to describe, but they are nonetheless a force in the world they occupy, and for that reason, we need to include them if we are to gain a full understanding of what is going on around us.

Behaviorism saw a decline in influence that directly resulted in the inability to explain intelligence. It was displaced by a reorientation of psychology toward the brain dubbed the cognitive revolution. The revolution produced modern cognitive science, and functionalism became the new dominant theory of the mind. Functionalism views intelligence (i.e., mental phenomenon) as the brain’s functional organization where individuated functions like language and vision are understood by their causal roles.

Unlike behaviorism, functionalism focuses on what the brain does and where brain function happens.[16] However, functionalism is not interested in how something works or if it is made of the same material. It doesn’t care if the thing that thinks is a brain or if that brain has a body. If it functions like intelligence, it is intelligent like anything that tells time is a clock. It doesn’t matter what the clock is made of as long as it keeps time.

Functional organization is an important step forward because it aligns both brain and mind with strategies for living. All living beings manifest strategies for living—that’s what unites us all. One of the functions of language is that it enables us humans, through the mechanisms of narratives and analytics, to explore strategic possibilities, both in fictional and historical terms, and to critique them through analytics, using natural language and/or mathematics. It also allows us to engage and enlist others in our undertakings by communicating, both intellectually and emotionally, the strategic rewards of so doing. Functional organization, in this context, bridges the gap between private mental experience and public social interactions, both of which are required for intelligence to be operational in the world.

The American philosopher and computer scientist Hilary Putnam evolved functionalism in Psychological Predicates with computational concepts to form computational functionalism.[17][18] Computationalism, for short, views the mental world as grounded in a physical system (i.e., computer) using concepts such as information, computation (i.e., thinking), memory (i.e., storage), and feedback.[19][20][21] Today, artificial intelligence research relies heavily on computational functionalism, where intelligence is organized by functions such as computer vision and natural language processing and explained in computational terms.

Unfortunately, functions do not think. They are aspects of thought. The issue with functionalism — aside from the reductionism that results from treating thinking as a collection of functions (and humans as brains) — is that it ignores thinking. While the brain has localized functions with input–output pairs (e.g., perception) that can be represented as a physical system inside a computer, thinking is not a loose collection of localized functions.

The meaning of the word think in the paragraph above is unclear, and as a result, the rest of the paragraph does not lead to any useful conclusion. But there is another dimension of computational functionalism that is important to note: it is entirely analytic. Indeed, the whole of both AI and machine learning is entirely analytic. We need to ask ourselves, what might that be leaving out?

The short answer is, biochemistry. The analytic model of mental activity, with its embedded metaphor of computers and computing, is based entirely on electronic signaling. There are no hormones at work. But among living things, long before there were any nerves to carry sensory information, there were chemical signals that served the same end. Such signals circulate from cell to cell, activating receptors that, in turn, generate some response out of which behavior emerges, something we see every day in the way flowers turn to the sun or the way sleepiness takes over our minds.

Now, to be fair, you won’t survive very long as a mobile animal if you don’t have an electric nervous system, so we are talking about an and here, not an or. But it is an incredibly important and because biochemical signals are the mechanism by which homeostasis is maintained. Homeostasis is what the AI/ML models leave out. It is a big miss.

Homeostasis is a condition of equilibrium in which an organism is best fit to operate. All living things seek homeostasis all the time. Thus, both emotionally and intellectually, we humans are wired to seek it, and it shapes everything we do. Strategies for living, in this context, are simply mechanisms for achieving a more desirable condition of equilibrium, one in which we are better fit to operate. We can experience this phenomenon as desire or need or fear or hope, but by way of one emotion or another, we will be motivated to act. That is what separates human intelligence from all forms of computational functionalism.

John Searle’s famous Chinese Room thought experiment is one of the strongest attacks on computational functionalism. The former philosopher and professor at the University of California, Berkley, thought it impossible to build an intelligent computer because intelligence is a biological phenomenon that presupposes a thinker who has consciousness. This argument is counter to functionalism, which treats intelligence as realizable if anything can mimic the causal role of specific mental states with computational processes.

If you are not familiar with this thought experiment, click on the URL in the paragraph above before reading further. While Searle’s argument is correct as far as it goes, it is misleading because it does not honor the idea that a competence achieved without understanding could convert to true understanding at some later date. That is contradicted by many commonplace experiences. Think of the way you learn multiplication tables. You don’t need to understand why 8 X 6 = 48. You just have to memorize that it does. But sometime later on you do realize that a rectangle that is 8 inches on one side and 6 inches on the other actually does contain 48 square inches, and the world becomes a little less mysterious. Now, to be fair to Searle, this may be exactly his point, that the two are not the same, and I of course, would agree. But I would argue that the two are connected more closely than he implies. And that leads me to believe that a computationally functional system might be able to evolve future understanding from current competence by hypothesizing strategies and testing to see if they can be fulfilled by using the mechanisms it has already mastered. At minimum, I think AI and ML will eventually want to develop a philosophy of mind in order to take their discipline to the next level.

That’s what I think. What do you think? P.S. You can read the original article here .

April 6, 2022

The Hard Problem—It’s Not That Hard

We human beings like to believe we are special—and we are, but not as special as we might like to think. One manifestation of our need to be exceptional is the way we privilege our experience of consciousness. This has led to a raft of philosophizing which can be organized around David Chalmers’ formulation of “the hard problem.”