Holly Robinson's Blog

May 19, 2025

Graduation Weekend Set My Hair on Fire

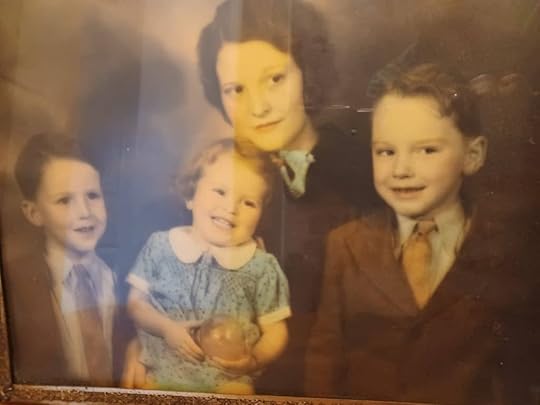

Like many in the U.S., my family immigrated here. My great-grandfather left England by ship to work in the woolen mills in Massachusetts. My grandmother, pictured above with my mom and two uncles, came with him. She favored wool skirts and regular cups of tea until she died at age 99.

Like many in this country, too, I attended a university graduation this weekend. I won’t say where or who it was for, because that’s not the point. The point is that it set my hair on fire. Not the graduation itself, but the contrast between that ceremony, with its earnest speakers and hopeful graduates from all over the world, and the news feed on my phone.

That Friday evening, after my husband and I celebrated the graduation with two Latin American students and a recent Chinese graduate, I opened my phone to a news story about ICE agents rounding up a dozen men who were waiting at a gas station for vans to pick them up for roofing jobs. This news headline came on the heels of a story about more than 1800 international students having their student visas revoked, often without warning. Some have been arrested and deported.

Trump made an election promise to initiate “the largest deportation program of criminals in the history of America.” But it looks to me like ICE is mostly targeting people who came here to support themselves and their families by roofing our buildings, preparing our food, cleaning our houses, mowing our lawns, taking care of our sickly grandparents, or studying to become the next generation of professionals.

I am not a divisive person. Nor am I typically politically outspoken. As the daughter of a Navy commander and a mother who wanted nothing more than Trump for President, my extended family includes kneejerk liberals who were Kamala all the way and Evangelical Christians who think JD Vance was doing the right goddamn thing when he made up stories about Haitians eating pets. But what can you do when your hair is on fire except scream?

Would Trump and Vance allow my white British family into the country now to work in the mills? Probably. I mean, look at the refugee resettlement program they suspended, then made an exception for, allowing white South Africans into this country because they’re allegedly facing “genocide.” Hello, people. What about the Congolese and Sudanese who are facing actual genocide? Is there any expedited program for them?

And what about the Afghans who came to this country legally, with protective status because they helped the U.S. military during the war, only to see that protective status rescinded despite their country being governed by the Taliban?

If the tariffs don’t sink the Republicans, their nutty deportation strategies will. Never mind the damage these strategies have already done to our global reputation as a compassionate, inclusive democracy where freedom rings.

With so few legal pathways open, people who immigrate here will be forced to live even more on the margins. Instead of diligently doing the paperwork required to be here legally, paying their social security, or sending their kids to school, immigrants will hide because they’re afraid. It’s already happening.

And those bright, ambitious young people? They’ll choose to study somewhere else, in countries where they won’t have to worry about being deported halfway through their graduate studies or, worse, arrested because they published an opinion that didn’t match the administration’s. Who can blame them for going elsewhere?

But it will be our country’s great loss, economically and morally.

The post Graduation Weekend Set My Hair on Fire appeared first on Holly Robinson.

March 30, 2025

How Are You Showing Up?

Recently, I streamed “Showing Up,” a movie starring Michelle Williams as a glum, frumpy sculptor working at the Oregon College of Arts and Crafts in Portland. My husband was so bored that he walked out, grumbling, “There’s no plot.”

But I stuck it out. For me, the movie’s shots of Williams’s character painstakingly creating sculptures, along with footage of other artists at the college engaged in painting, throwing pots on a wheel, or just struggling with giant pieces of foam, served as a great reminder of the ordinariness of an artist’s daily life, and of the vast number of hours it takes to complete a project that will likely be unpaid, all while the world keeps throwing obstacles in your way.

The movie hit home because it has been nine years since I published my last novel, leading to uncomfortable remarks from friends and strangers, like, “Are you still writing?”

I am still writing, and joyfully so. But here’s the thing: writing and publishing are two different beasts. Sure, if you self-publish, you can take charge of your own publishing calendar. Some indie authors publish several novels a year, or even several novels each month. There is even chatter online about certain authors using AI tools to help them generate hundreds of novels a year. Good for them if they’ve figured out how to make a living as writers.

For better or worse, I am not one of those writers. My novels have been traditionally published, which means having an agent accept your work and shop it around to find an editor who wants to publish it. This process, as anyone knows who has tried it, is so damn daunting that it’s tempting to lie down and give up. Just querying agents can feel like a full-time job. And the rejections? Let’s not even talk about those.

Or no, let’s talk about them, because rejections in any artistic field are typically more common than acceptances. Since my last published novel, I have researched and written a novel based on the life of a 19th-century poet, a psychological suspense novel set in San Francisco, and a suspense novel set along El Camino in Spain. None of them sold. My previous agent and I parted ways (amicably), which meant I had to find another agent.

My new agent, whose opinion is gold to me, liked the Spain novel but had suggestions for revisions. Another three months went by at my desk. Finally, the manuscript was ready to submit to my editor. She liked the first half of the novel, but saw problems in the second half, so it was back to my desk for another few months. Then I sent the book to the agent again.

And guess what? He made yet more suggestions, so I’ve revised it again. Now I’m hopeful that the book is ready. But if not, I will return to my desk and chew on it some more. Showing up in art, as in life, is everything. We must be accountable, present, and engaged in our daily lives, earning enough money to pay the mortgage, taking the kids to soccer practice, driving a friend to chemo, or volunteering in our communities. Our lives are made up of these tiny, seemingly inconsequential moments, as are the books we write, the music and paintings we create, and the sweaters we knit. Every time you show up, you are making progress, even if it doesn’t always feel that way.

The post How Are You Showing Up? appeared first on Holly Robinson.

December 16, 2024

Making New Holiday Traditions When the Old Ones Break

My youngest son called yesterday with an apology. “I’m sorry, Mom, but do you mind if I don’t spend Christmas with you?”

He had a valid reason: his girlfriend’s parents are coming to their apartment for Christmas, and she asked him to stay and share the holiday.

“No. I don’t mind at all,” I said. “Of course you should stay.” Then we hung up and I cried.

Why was I so sad? It was stupid. I know I should be ecstatic—and let’s be clear, I am—that my children are fully fledged, with partners, jobs, apartments, and busy lives. But like most of us, holidays are weighed down with an absurd amount of emotional baggage for me. I am a child of divorced parents. My childhood Christmases were fraught with tension. When I got divorced and was a single mom with two kids, then got remarried to a man with two kids of his own, I swore that our family Christmases would always be holidays of joy and abundance.

Our holidays have changed now that everyone is older and partnered. One or more kids have been missing from the Christmas table in past years. Sometimes that’s easier. Like all families, ours is full of Personalities with a capital “P.” There have been rifts, slights, and silences. But this is the first time I’m celebrating Christmas without a single child on the holiday itself, and it feels wrong.

To be fair, it’s partly our fault. For the first time in 30 years of marriage, my husband and I are not hosting Christmas. We are, instead, going to New York to my niece’s place because her parents, my brother and his wife, will be visiting from England. When we first hatched this plan, it was partly because two kids had already announced they would be on the West Coast for the holiday, visiting their in-laws.

So when we got the invitation from my niece, my husband looked at me and said, “Wouldn’t it be nice to be guests, just this once? No buying a stupidly expensive roast and tree this year!” he added gleefully.

“No beds to change or sheets to wash. I’m not even putting up the lights,” I declared. “And forget wreaths.”

“Yup. Mr. and Mrs. Scrooge, that’s us,” my husband said.

Except then our youngest daughter, who lives abroad and has a two-year-old, was upset that we weren’t having Christmas. We hated disappointing them, so they got on a plane and came here for a Christmas celebration the second week of December. Yup, the whole she-bang: a tree, stockings, presents, a Christmas roast, and a wreath. And you know what? It was lovely, introducing the two-year-old to Santa and stockings, and seeing her face on “Christmas morning.”

Now our oldest daughter might come for an early Christmas, too. It’s a good thing we got the tree and I put those lights up after all. (All these years, I’m the one who wanted lights. I can admit that now.)

I’m adjusting to my new reality. The children will gather with us, and with each other, too—my oldest son and daughter just had an early Christmas dinner together in New York with their spouses—but on their timetable. And, on Christmas Eve, my husband and I will travel alone to New York, and maybe I’ll talk him into walking around Rockefeller Center and Central Park. Or we’ll see the light show at the Brooklyn Botanical Garden. It won’t be the postcard-perfect holiday of an entire family gathered under the tree, but I’m discovering that the trick to feeling joyful lies in celebrating the moments we have, not the moments expected.

The post Making New Holiday Traditions When the Old Ones Break appeared first on Holly Robinson.

December 11, 2024

How to Take a Writing Retreat without Breaking the Bank

Nothing is on the oak desk except my humming laptop and notebook. Every window is an art installation with mobiles and colored glass bottles. The house is silent except for the dogs occasionally turning over in their sleep with soft snorts. I’m in heaven.

Thanks to my artist friend Tom, who needed someone to walk his dog today, I have a place to bring my dogs and write outside my house. You’d think I wouldn’t need a writing retreat to put words on the page. My kids are grown and I’m a seasoned writer with many published books. But you would be wrong.

Writing any book takes more head space than most of us have at home. Facing a blank page can spark a flurry of panic brought on by the steady drumbeat of “I’m writing crap.” It’s easy to let people or chores interrupt your concentration. A writing retreat can keep your manuscript moving forward.

There are many writing conferences where you can meet other writers, attend craft classes, and workshop your manuscripts. These serve a purpose. You might network and meet your dream agent, or a mentor might critique your manuscript in a way that lets in some fresh air. But you won’t put many words on the page at these conferences with so much stimulation.

If you’re lucky, you might qualify for one of the “real” writing residencies in a place like Yaddo, MacDowell, or Ragdale. These provide ideal spaces and quiet time for writing, but they’re often tough to get into and require a lengthy stay. And, if you don’t qualify for a scholarship, these residences can be expensive.

Luckily, there’s a solution: Create your own writing retreat. Borrow a friend’s empty house or rent a cheap place off-season (like in a beach town in the dead of winter or a ski area during mud season.)

If you don’t have friends with spare houses and can’t afford a rental, another solution is to join a site like TrustedHousesitters.com. In exchange for taking care of someone else’s pets, you can have a quiet retreat.

Religious retreats are also an option. One place near me provides inexpensive private retreats to anyone in a contemplative mood; it’s an ensuite bedroom in a rambling house on a reservoir. For a few extra dollars I can take my meals in the cafeteria with the Unitarians and Episcopalians gathered for group retreats.

If none of these options are available, make use of your public library. Most offer tutorial rooms with doors that close, or you can find a quiet study carrel among the stacks of books. I’ve even driven to certain libraries outside of my town because they offer cafes or indoor atriums.

The toughest part of creating a retreat is believing in yourself enough to make it happen. If you make a habit of writing retreats, you’ll write more, guaranteed, because you’ll also start thinking of yourself as a writer.

The post How to Take a Writing Retreat without Breaking the Bank appeared first on Holly Robinson.

November 19, 2024

Whoa, I’m in a Waymo

I gasped as the car navigated a hairpin turn and confronted new obstacles: a parked Amazon truck, a double-parked Toyota, and a woman pushing a stroller. To complicate matters, we were on such a steep San Francisco hill that I instinctively leaned forward in a misguided effort to keep the car from rolling backward.

“What will Waymo do?” I asked my husband.

“The system is trained to calculate situations like this. Relax.”

Waymo, in case you haven’t visited San Francisco, Los Angeles, or Phoenix lately, is Google’s fully self-driving robotaxi, and on a recent trip to San Francisco, we rode in one every day. To be clear, I’m more accustomed to robots than most people. My husband is a robotics engineer, and so is my son. I’m familiar with robots that do everything from climbing stairs in dog-shaped bodies to growing plants or loading boxes onto conveyor belts. Some have even become part of our family, like the little robot vacuum that committed Hari Kari when it swallowed one of my scarves in the closet.

Still, even for me, riding in a driverless car was a freaky experience. With Waymo, you use your phone to summon it the way you call an Uber or Lyft. When your sparkling white chariot arrives, it’s equipped with a swirly gadget on the roof and other protrusions. These are the lidar, cameras, and sensors that allow the car to “see” objects around it. You can see them, too, as a weird little video game playing out on screens inside the car. The pictures are fairly accurate: if a man is walking a dog on the sidewalk beside your Waymo, there’s a little cartoon man with a dog on a leash. Ditto with kids on skateboards and bikes.

There’s music, too. Entering a Waymo, you’re greeted by name, reminded to fasten your seatbelt, and then you hear space-age elevator music, enhancing that feeling of being caught in a Jetsons cartoon with flying cars. (Those, too, are coming soon.)

The Waymo, as my husband predicted, smoothly navigated the narrow channel between the two vehicles clogging the road and summited the hill with ease. Well done, Waymo.

After a few more rides, I trusted the vehicles not to lose their brakes on steep hills or hit anything, so it took me a while to realize why I still felt uneasy. Just to compare, we also called an Uber while we were in San Francisco. The driver was from Nigeria and we chatted as he drove. He told us about his three daughters: a lawyer, a nurse, and an engineer. “I miss my country, but it was worth coming to the U.S. to educate my girls,” he said.

For someone like my husband, who is fascinated by technology, Waymo was the transportation winner. For me, not so much.

Sure, Waymo cars are electric, and if people take Waymo, they don’t need to bring their cars into the city. The air is cleaner as a result. That’s great. But robotaxis also keep us separate from other people. Do we need to isolate ourselves even more than we do?

Think about it. Many of us no longer work in offices, thanks to remote work options. In the evenings, most of us aren’t out socializing, either, because we’re playing video games or streaming shows. (Okay, a few of us are still reading books.) Instead of walking, we ride around in our private cars or, increasingly, in robotaxis like Waymo. Even if we go to a bar or a diner, we’re apt to be on our phones instead of chatting up the strangers on either side of us. We like being in our safe bubbles.

Safe bubbles take the stress out of life. But the problem with being in a bubble is that you can’t feel the beat of a city. You might argue in favor of avoiding urban decay—I’ll admit that walking in downtown San Francisco can be a hellishly unpleasant experience at times– but, if we avoid seeing the people around us, and I mean all of the people, we’re less inclined to get involved with the humans sharing this planet. It takes all kinds of people to make the world go around. We need to acknowledge, and embrace, this shared humanity if we’re going to work toward making the planet better for everyone.

For me, the best option in any city is still to walk its streets or take public transportation and chat with the people I meet who are willing to lift their heads from their phones. Barring that, I’ll choose a conversation with an Uber driver over a car that drives itself.

The post Whoa, I’m in a Waymo appeared first on Holly Robinson.

November 5, 2024

Running and Crying in Brooklyn

I visited my son and his wife in Brooklyn a few days before the election and went for an early run. The run took me through the projects and down along Broadway, beneath the screeching subway tracks, then to Domino Park, where I ran beneath the Williamsburg Bridge and watched tugboats and commuter ferries gliding through the molten-looking water.

On the other side of the river, the Empire State Building’s iconic silhouette reflected the morning sun, and the Chrysler Building, the queen jewel of Manhattan’s skyline, stood tall and elegant. From the water I looped back through Bushwick, running through Williamsburg’s tree-lined streets past vintage stores, coffee shops, and yoga studios.

Running through a different city is one of my favorite things to do. That day, though, midway through the route, I felt tears streaming down my face as I watched people walking their kids to school, climbing the daunting metal staircase to the overhead train, and sweeping the stoops of their corner stores. I cried when I passed a girl with pink hair smoking a cigarette, a sleeping woman sitting in her shopping cart of worldly belongings, and a pair of men in expensive jackets.

It took me another mile or so before I recognized that I was crying not because I was sad, but because I was so honored to be here, “on the green side of the sod,” as my Uncle Pete used to say. I felt privileged, ecstatic, even, to see the tattooed artist going into his studio, the guys in safety vests stopping at the corner store for their egg sandwiches, and the mom nursing her baby on a park bench. Life was flowing all around me on the streets of Brooklyn, people of all colors and sizes and histories, and I was flowing with it, one more speck of humanity being carried by her own feet, yes, but also by all of the lives around me.

Here’s the thing: whenever people talk about a divided nation, they forget that all of us are in this together. We live and work and raise our children the best we can alongside our neighbors. In Brooklyn, in San Francisco and Chicago, in Dallas and Portland, and every place in between, we are all doing our best to feed and house our families, and to do work that matters or at least a job that pays the rent. We are keeping our cars running and worrying about whether our sports teams will win or not, and maybe planning a special celebration for someone we love.

As the poet Mary Oliver wrote:

“Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.”

The world will go on after today’s election, and even if there is chaos in the days to come, and you and I will still belong to it. So go ahead and dare to be hopeful about the future.

The post Running and Crying in Brooklyn appeared first on Holly Robinson.

August 18, 2024

The Pleasure of Being Lost

The tree branches tunnel above me as I run down the path. The sky is growing darker. The rain, when it comes, whispers through the leaves at first, then falls hard enough to mask the sound of my footsteps.

Ahead of me a robin flits along the path, then is joined by another bird and another. Soon there’s a flock of robins flying ahead of me, close to the ground. I never knew robins gathered like this, but here they are, a dozen orange-bellied birds darting swiftly across the path as the rain comes down so hard that I have to take off my glasses to see.

I’m lost, but happy, running along this trail through the rain. I’m in a park near my in-laws’ house in suburban Minneapolis; it would be easy enough to whip out my phone and use a map to get back, but I don’t. Mini adventures like these fuel my days.

Before becoming a wife and mother in my thirties, I had much grander adventures: trekking through Nepal, taking trains alone through India, snorkeling in Bali, horseback riding in Mexico, climbing in the Andes. I was often lost. We had no cell phones then and my paper maps were constantly getting shredded in my backpack. Map folding is not my forte.

These days, my adventures are more curated. My husband Dan and I walk sections of El Camino in northern Spain every year. We’ve hiked in New Zealand and biked through the San Juan Islands. But, even in the most remote areas, even on the original pilgrimage path through the Pyrenees Mountains, Dan has maps downloaded on his phone. He’s an engineer and takes no joy in being lost.

The thing is, when you always know where you are, a part of your brain falls asleep. You pay less attention because you don’t have to remember that tree you passed with the crooked trunk, or that odd white fungus that people call “ghost pipe.” You just happily plod on by.

The same is true in a city. If you always look down at the map on your phone—something I see people doing not only in cities, but even here in our own small town—you aren’t observing your surroundings. You miss admiring the ornate door knockers in Back Bay or the lush wisteria on someone’s backyard trellis because you’re too busy navigating to your destination to notice any of it. And you never, ever have to ask for directions, which of course is a relief for many people who loathe talking to strangers.

I love asking for directions, because that often leads to impromptu conversations. These conversations with strangers have led to invitations to tea or even a walking companion. Once, in New York City, I stopped to ask directions and ended up talking about politics in Paris with a French diplomat who not only gave me directions, but carried my suitcase up three flights of stairs because the subway escalator was broken.

But the mini adventures I love best involve getting lost on a trail through the woods, where my senses have to kick into high gear to find my way. These are the times I’m most connected to the planet, to the small ferns quivering bright green beneath the trees, to the robins darting along the path and the sound of a creek tumbling over rocks. When we are lost, we have no choice but to be fully present.

Eventually the path forks and I recognize the uphill slope by a pair of park trash cans that I noticed on the way into the woods when I arrived. Back at my in-laws’ house, my husband looks relieved. “We were worried about you running through the park in all this rain,” he says.

“It was great,” I say, and toe off my sodden shoes, happy to be in a warm dry place, and happier still for having felt the wet earth beneath my feet.

The post The Pleasure of Being Lost appeared first on Holly Robinson.

July 25, 2024

Parenthood: A Shipwreck of Memories

I’m at our house on Prince Edward Island, and yesterday morning I went down to the beach for a run. It’s a beautiful beach, one you access by a red dirt road. The sand is the singing sort. It’s a joy to run here at low tide when the beach is wide and flat, with tide pools that make you feel ten years old again as you splash through them.

This morning I was feeling energetic, maintaining a decent (for me) pace, and feeling good about life in general. I’m here with a friend on a writing retreat and we have similar rhythms; we work toward pesky book deadlines and take beach breaks, share our writing, and live in t-shirts and sweatpants. So I was all smiles, even while running and panting, until I saw the shipwreck.

I mean that literally: it’s an actual shipwreck, the remains of which I have observed at low tide on this beach since my youngest son was eleven years old. That’s the year we bought this house, the year we found the shipwreck together; he’s twenty-six now. Aidan and I made up stories about pirates and mermaids as we examined the remains together. We talked about the engine and the wood, how the ship was made, and what could have caused it to sink and run aground. Every day at low tide, for many summers, Aidan wanted to walk to the shipwreck, and whenever we brought his friends to the island, that was often the first thing he wanted to show them.

Now, seeing the shipwreck at low tide, and spotting another young boy examining it with his mother, the two of them squatting in the sand, heads close together as they imagine what brought this lichen-covered vessel with its rusty engine to our beach, memories clamor to be seen and heard. Aidan hasn’t come to the island with me in years, nor have my other adult children.

I keep running past the shipwreck to banish the memories, but of course that’s impossible. That is the joy and the grief of parenthood, isn’t it? We bring children into the world and devote ourselves to giving them the love, knowledge, and dreams we believe will lead them into a world where they will thrive and be better people than we are. My children are, thankfully, doing just that, but at times it’s a painful pleasure to see them live so independently. A few years ago, I traveled to Alaska to visit my daughter, who was a forester there at the time, and she packed our things for a hike, including homemade granola bars and bear spray. It was clear to me then that our roles had reversed: this curly-headed beautiful creature, who I once made hold my hand while crossing the street, was taking care of me in a vast, bear-infested wilderness. Yet still I can feel that little phantom hand in mine.

My oldest son is now in his thirties and married, with a successful career and a passion for music and writing. He was a peaceful child, observant early on. When he was a toddler I’d sometimes bring him to the library to do research and spread a blanket at my feet with toys. He’d sit there for as long as I wanted to write, playing and entertaining himself. A few weeks ago, this son and I met at a Boston WeWork space to hang out and work on our separate writing projects. At one point I turned to him and saw not his bearded, Brooklyn-dwelling self, but the bald and quizzical baby he once was, flipping through cloth books long before he could read. That, too, was a joyful memory that brought the sharp sting of time passing.

Recently, I asked a young friend how he felt about being a father himself now that he had a baby. He thought for a minute and said, “I am no longer the main protagonist of my own story.”

This is true for a time. When children are young, good parents put them first in most things. But then the children leave and you are left with the old art portfolios from third grade, bins of Legos and stuffed toys, base amps that work, and forgotten hoodies. Your story is your own again, as you continue working in your often empty house or making vacation plans that no longer involve booking multiple hotel rooms. It is a new sort of freedom, one you treasure because it’s a novelty.

Yet there is this thing you carry, this box or suitcase or shipwreck of memories, of the person you were when the children were young, as well as the person you were before parenthood and the person you are now. It’s a many-layered self, and sometimes you wish you could go back in time, peel back some of those layers, and have your children hold your hand one more time when you cross the street because you didn’t realize that last time was, in fact, the last.

I am still running on our beach as I think about this, until eventually I turn around at the Basin Head bridge where my children, as teens, used to jump off into the river below. As I run back, a man jogs toward me. He’s about my oldest son’s age, bearded, too, and for a moment my heart leaps.

Then the man gives me a “V” sign with his fingers, and I do the same to him in return, acknowledging that, by running, we are accomplishing something, achieving a small victory by moving our bodies through space and time, even as we are awash with memories we can’t, and shouldn’t, try to outrun.

The post Parenthood: A Shipwreck of Memories appeared first on Holly Robinson.

June 5, 2024

The Deathbed Promise Dog

Bella is cowering beneath my desk because a motorcycle roared by. This dog’s list of fears knows no bounds: plastic bags, umbrellas, rolling trash can lids, inflatable holiday decorations, trucks, bicycles, car rides. Oh, and brooms.

Yet, if you put this knee-high animal–a chihuahua/rat terrier/Jack Russell mix—on a leash, she morphs into Cujo, threatening pit bulls and horses with noisy bravado.

I’ve never owned a dog like this. My dogs tend to be calm. Even laconic. Merlin, the dog I had before I inherited Bella, is as Zen as they come, rolling onto his back for a belly scratch whether he’s greeting the Amazon delivery person or a bunch of shrieking kids.

Bella was my mother’s dog, an ill-considered pandemic choice made in 20 seconds in a church parking lot, after my mom’s previous dog, also a trembling chihuahua, died suddenly of a heart attack.

“I know I shouldn’t get another dog, but I hate being without one,” Mom said as we waited in the parking lot for some stranger who claimed she had a dog to give away—free.

“I understand,” I said, and I did.

My mother was in her late eighties and still living independently during the pandemic, which meant she was completely isolated. Other than seeing me, her world had shut down. She wasn’t isolated in a nursing home, thank God, but her beloved senior center activities had all been curtailed. The days stretched out, long and lonely, in her tiny apartment. She needed a companion.

Bella, we discovered when the woman arrived, had been rescued three times already, first from Puerto Rico and most recently from the woman’s own daughter, who was moving into an apartment that didn’t take dogs.

“She’s not too friendly with other dogs,” the woman said when I tried to bring Merlin over to greet Bella.

That was an understatement. Bella lunged at Merlin and acted like she’d tear him to pieces, nearly pulling over her owner in the process.

“Mom, this dog is a bad idea,” I said.

“Oh, nonsense. I can handle her,” Mom said. “And look at the poor thing. She just needs love.”

Bella needed a lot more than that. With her hyperactivity level she needed a race track, but my mom suffered from chronic lung disease and couldn’t walk more than a few feet outside her apartment. The dog was clearly going crazy, so one day I let her loose in my back yard with Merlin. Bella raced around the yard in dizzying circles. To my surprise, when I called her name, Bella trotted right over to me.

She was happiest off-leash, clearly, so I started taking Bella on hikes with Merlin and me. (Pekingese are surprisingly good hikers if you don’t treat them like lap dogs.) Bella loved these woodsy runs and gradually relaxed. Off leash, she sometimes barked at other dogs, but she quickly became more social. Our dog-walking neighbors gradually stopped having to cross the street when they saw us coming as Bella learned she could have friends.

The only problem was that, when I took Bella back to my Mom’s apartment, I’d hear the dog fling herself against the door when I left; clearly, Bella had decided that she was meant to live with Merlin and me. Even when I visited at the apartment, Bella would sit in my lap or, worse, curl up behind me, hiding from my mother.

“Well,” my mother sniffed, “I guess you’ve got another dog.”

I didn’t want another dog, especially not such a high-maintenance one, but a year after the world opened up again, my mother’s health declined and she moved in with us. Now Bella could sleep on my mom’s bed and sit on her lap, but still hang out with Merlin in the living room. She flourished.

“You’ll take care of Bella for me, won’t you,” Mom said a few days before she died. It wasn’t a question.

“Of course,” I promised.

After Mom was gone, friends who’d heard me joke about “Little Miss High Anxiety” suggested that I find another home for Bella. I love to travel, and Bella hates car rides and freaks out in hotels. Having two dogs is expensive as well. Several people offered to take her for me and would have given Bella a good home, but I couldn’t do it. Mine was the lap Bella always chose in the TV room, and Bella followed me everywhere in the house, upstairs and down, no matter what I was doing. She had become my shadow.

I thought I was simply keeping my promise by putting up with Bella. Recently, however, I lost her on a hike and started to cry when I thought I might not find her. When Bella came running back to me a few minutes later, I laughed at the sight of her tiny body flattened out like a greyhound’s in her hurry to return. My mom was right after all: I’ve got another dog.

The post The Deathbed Promise Dog appeared first on Holly Robinson.

May 24, 2024

Am I Cool Enough for a Stanley Cup?

My husband is staring at me in astonishment. “Are you actually carrying that around?”

“Of course.” I cocked a hip, trying to look extra cool as I heaved my new orange Stanley cup off the counter.

If you don’t know what a Stanley cup is, you probably aren’t hanging around people in their twenties who are all toting around 40-ounce metal mugs with straws like they’re about to trudge across the Sahara.

Those who swear by Stanleys believe you should drink two full Stanley cups of water per day. To be fair, the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine say men should drink 125 oz. of liquid daily, and women should be downing 91 oz. But I grew up during a time when we never drank water. Sure, we might sip it from a trickling fountain at school, but we did sports and watched TV, partied, and joined protest marches on Washington with nary a water bottle in sight, never mind a manly Stanley mug. And guess what? We survived—even though we never put protein powder in our smoothies, either.

But that’s not the point. The real question on my mind is whether I’m cool enough to carry the Stanley in public. Because guess what? I, too, am now addicted to the Stanley. Maybe it’s because my son gave it to me and I love him. Or maybe it’s because the color orange makes me happy, or because lifting a Stanley all day means I feel justified skipping the dumbells at the gym. Whatever the reason, I’m carrying my Stanley everywhere: to my office, out to the screen porch, in my car. I just haven’t yet dared let anyone see me do it.

Here’s the thing. This winter, I bought a warm jacket on sale that happens to be bright teal with flowers, and everywhere I went, people would say, “I love you in that jacket!” or, “That’s an adorable coat.”

Slowly, it’s dawning on me that I am at the “adorable” stage of womanhood. Not cute, as in girlish, and not pretty or beautiful or elegant, as in being a good-looking woman, but adorable, aka, nonthreatening.

I’ve heard lots of women talk about feeling invisible once they cross a certain age threshold, but I haven’t heard anybody complain about being called “adorable,” so I started asking around.

“Oh, God yes,” said one friend.

“Absolutely,” said another, adding, “The only thing worse than being called adorable is when they call you ‘spry.’”

True. On the other hand, why not embrace the possibilities?

Recently I had a complete loss of sanity in a clothing store and bought a pair of black denim overalls that make me look like a toddler, and my rainhat has a lining of brightly-colored birds. I also own a bunch of striped headbands for running that made my brother say I look like Richard Simmons. Can a sparkly gold romper be far behind?

“Eccentric lady writer,” I told my husband as I headed out to my office with my Stanley cup and two dogs in tow. “That’s the look I’m going for now.”

It’s a good look, right? After all, I’m one of the lucky ones, having reached an age of grace where I can relax and be exactly who I am, navigating the world in a way that gives me joy.

The post Am I Cool Enough for a Stanley Cup? appeared first on Holly Robinson.