Pete Mesling's Blog

August 10, 2019

Glad Men from Happy Boys ... or Else: A Review of Thomas Tryon's THE NIGHT OF THE MOONBOW

Some things in life make absolutely no sense. That Thomas Tryon isn’t a household name is one of them. I’m too young to know what it was like to watch him transition from film actor to man of letters, but it must have been deeply satisfying for him to make the transition as admirably as he did. There had to be doubters. It’s easy to imagine the cynicism that might have accompanied the shift. Maybe I would have been a bit skeptical myself. The Night of the Moonbow should have been enough to put such concerns to bed, for those not already convinced by Tryon's previous books, such as The Other and Harvest Home. It is one of the finest books I remember reading in my teenage years. I recently read it again, and it was a rare pleasure. Not only did the novel live up to every one of my fondest memories. It surpassed them all.Welcome to Camp Friend-Indeed, which proudly claims to make “Glad Men from Happy Boys.” What the slogan leaves out, of course, is what can be expected of not-so-happy boys who arrive at the Connecticut summer camp several years before the United States would enter the fray of World War II. The paperback that was my first encounter with Moonbow was marketed as a horror novel, right down to the garish raised lettering on the front cover and the hyperbole on the back. But this is no horror novel.Except that it is—kind of. The term “psychological horror” can get us out of a lot of tight squeezes, so maybe that’s the file drawer I’ll slip Moonbow into for now. Still, there is a sense that if The Night of the Moonbow can be called a horror novel, damn near anything can. Really it’s a novel about friendship, adolescence, courage, and trauma—though of course a horror novel can be about all of those things as well. Moonbow also happens to be beautifully written, with characters so lovingly wrought it’s easy to feel that you’re moving among them as you follow them from cabin to lodge to “haunted” house to dining hall to campfire to lake (Tryon’s map at the beginning of the book only intensifies this effect). I suppose that’s what all the best books do, put you smack dab in the action, where you can live and breathe the setting right along with the characters. But I feel that the boys at Camp Friend-Indeed gather in a bit closer than the characters of many books. You can almost tousle their hair as they run past, and feel the breeze that stirs in their wake. You certainly wish you could step in to take corrective action on more than one occasion.I guess what I’m trying to say is that The Night of the Moonbow has powerful magic coursing through its pages, like all great books. I’ve done a bit of literary prestidigitation myself, and part of the process remains as mysterious to me as ever. The closest I’ve come to unraveling its secrets is to understand that you have to open yourself up to the magic. At least that way, if it does come, it will have a way in. And of course some tricks are easier to pull off than others. Plenty of writers can separate the occasional Chinese linking rings or make a dove disappear behind a handkerchief, but the illusion in Moonbow is more prodigious than that. In it, Thomas Tryon levitates the so-called real world so you can see the one beneath it. Some of what you see there is beautiful, while some of it is, yes, horrifying. All of it feels true.Abracadabra, ladies and gentlemen. That’s a neat trick.

The Night of the Moonbow should have been enough to put such concerns to bed, for those not already convinced by Tryon's previous books, such as The Other and Harvest Home. It is one of the finest books I remember reading in my teenage years. I recently read it again, and it was a rare pleasure. Not only did the novel live up to every one of my fondest memories. It surpassed them all.Welcome to Camp Friend-Indeed, which proudly claims to make “Glad Men from Happy Boys.” What the slogan leaves out, of course, is what can be expected of not-so-happy boys who arrive at the Connecticut summer camp several years before the United States would enter the fray of World War II. The paperback that was my first encounter with Moonbow was marketed as a horror novel, right down to the garish raised lettering on the front cover and the hyperbole on the back. But this is no horror novel.Except that it is—kind of. The term “psychological horror” can get us out of a lot of tight squeezes, so maybe that’s the file drawer I’ll slip Moonbow into for now. Still, there is a sense that if The Night of the Moonbow can be called a horror novel, damn near anything can. Really it’s a novel about friendship, adolescence, courage, and trauma—though of course a horror novel can be about all of those things as well. Moonbow also happens to be beautifully written, with characters so lovingly wrought it’s easy to feel that you’re moving among them as you follow them from cabin to lodge to “haunted” house to dining hall to campfire to lake (Tryon’s map at the beginning of the book only intensifies this effect). I suppose that’s what all the best books do, put you smack dab in the action, where you can live and breathe the setting right along with the characters. But I feel that the boys at Camp Friend-Indeed gather in a bit closer than the characters of many books. You can almost tousle their hair as they run past, and feel the breeze that stirs in their wake. You certainly wish you could step in to take corrective action on more than one occasion.I guess what I’m trying to say is that The Night of the Moonbow has powerful magic coursing through its pages, like all great books. I’ve done a bit of literary prestidigitation myself, and part of the process remains as mysterious to me as ever. The closest I’ve come to unraveling its secrets is to understand that you have to open yourself up to the magic. At least that way, if it does come, it will have a way in. And of course some tricks are easier to pull off than others. Plenty of writers can separate the occasional Chinese linking rings or make a dove disappear behind a handkerchief, but the illusion in Moonbow is more prodigious than that. In it, Thomas Tryon levitates the so-called real world so you can see the one beneath it. Some of what you see there is beautiful, while some of it is, yes, horrifying. All of it feels true.Abracadabra, ladies and gentlemen. That’s a neat trick.

The Night of the Moonbow should have been enough to put such concerns to bed, for those not already convinced by Tryon's previous books, such as The Other and Harvest Home. It is one of the finest books I remember reading in my teenage years. I recently read it again, and it was a rare pleasure. Not only did the novel live up to every one of my fondest memories. It surpassed them all.Welcome to Camp Friend-Indeed, which proudly claims to make “Glad Men from Happy Boys.” What the slogan leaves out, of course, is what can be expected of not-so-happy boys who arrive at the Connecticut summer camp several years before the United States would enter the fray of World War II. The paperback that was my first encounter with Moonbow was marketed as a horror novel, right down to the garish raised lettering on the front cover and the hyperbole on the back. But this is no horror novel.Except that it is—kind of. The term “psychological horror” can get us out of a lot of tight squeezes, so maybe that’s the file drawer I’ll slip Moonbow into for now. Still, there is a sense that if The Night of the Moonbow can be called a horror novel, damn near anything can. Really it’s a novel about friendship, adolescence, courage, and trauma—though of course a horror novel can be about all of those things as well. Moonbow also happens to be beautifully written, with characters so lovingly wrought it’s easy to feel that you’re moving among them as you follow them from cabin to lodge to “haunted” house to dining hall to campfire to lake (Tryon’s map at the beginning of the book only intensifies this effect). I suppose that’s what all the best books do, put you smack dab in the action, where you can live and breathe the setting right along with the characters. But I feel that the boys at Camp Friend-Indeed gather in a bit closer than the characters of many books. You can almost tousle their hair as they run past, and feel the breeze that stirs in their wake. You certainly wish you could step in to take corrective action on more than one occasion.I guess what I’m trying to say is that The Night of the Moonbow has powerful magic coursing through its pages, like all great books. I’ve done a bit of literary prestidigitation myself, and part of the process remains as mysterious to me as ever. The closest I’ve come to unraveling its secrets is to understand that you have to open yourself up to the magic. At least that way, if it does come, it will have a way in. And of course some tricks are easier to pull off than others. Plenty of writers can separate the occasional Chinese linking rings or make a dove disappear behind a handkerchief, but the illusion in Moonbow is more prodigious than that. In it, Thomas Tryon levitates the so-called real world so you can see the one beneath it. Some of what you see there is beautiful, while some of it is, yes, horrifying. All of it feels true.Abracadabra, ladies and gentlemen. That’s a neat trick.

The Night of the Moonbow should have been enough to put such concerns to bed, for those not already convinced by Tryon's previous books, such as The Other and Harvest Home. It is one of the finest books I remember reading in my teenage years. I recently read it again, and it was a rare pleasure. Not only did the novel live up to every one of my fondest memories. It surpassed them all.Welcome to Camp Friend-Indeed, which proudly claims to make “Glad Men from Happy Boys.” What the slogan leaves out, of course, is what can be expected of not-so-happy boys who arrive at the Connecticut summer camp several years before the United States would enter the fray of World War II. The paperback that was my first encounter with Moonbow was marketed as a horror novel, right down to the garish raised lettering on the front cover and the hyperbole on the back. But this is no horror novel.Except that it is—kind of. The term “psychological horror” can get us out of a lot of tight squeezes, so maybe that’s the file drawer I’ll slip Moonbow into for now. Still, there is a sense that if The Night of the Moonbow can be called a horror novel, damn near anything can. Really it’s a novel about friendship, adolescence, courage, and trauma—though of course a horror novel can be about all of those things as well. Moonbow also happens to be beautifully written, with characters so lovingly wrought it’s easy to feel that you’re moving among them as you follow them from cabin to lodge to “haunted” house to dining hall to campfire to lake (Tryon’s map at the beginning of the book only intensifies this effect). I suppose that’s what all the best books do, put you smack dab in the action, where you can live and breathe the setting right along with the characters. But I feel that the boys at Camp Friend-Indeed gather in a bit closer than the characters of many books. You can almost tousle their hair as they run past, and feel the breeze that stirs in their wake. You certainly wish you could step in to take corrective action on more than one occasion.I guess what I’m trying to say is that The Night of the Moonbow has powerful magic coursing through its pages, like all great books. I’ve done a bit of literary prestidigitation myself, and part of the process remains as mysterious to me as ever. The closest I’ve come to unraveling its secrets is to understand that you have to open yourself up to the magic. At least that way, if it does come, it will have a way in. And of course some tricks are easier to pull off than others. Plenty of writers can separate the occasional Chinese linking rings or make a dove disappear behind a handkerchief, but the illusion in Moonbow is more prodigious than that. In it, Thomas Tryon levitates the so-called real world so you can see the one beneath it. Some of what you see there is beautiful, while some of it is, yes, horrifying. All of it feels true.Abracadabra, ladies and gentlemen. That’s a neat trick.

Published on August 10, 2019 15:42

August 7, 2019

If YouTube, ITube: Introducing the New Pete Mesling Video Channel

As some of you may recall, I tried my hand at a podcast several years ago. Had a lot of fun with it, honestly. But it swallowed my time. Well, I think I’ve found a compromise. In addition to my PaleSister YouTube channel, which is where you can find an assortment of my no-budget guitar videos, I now have a second channel under the name Pete Mesling. This channel will be devoted to writerly matters, ranging from publishing news to live readings and who knows what all. I only have two videos up so far, but two more will follow pretty quickly, since I have a story and a poem coming out in separate publications very soon.I expect all of this to be as fun as the podcast was, once I get my video legs (be restrained in your early judgments, I implore you). In fact, if it ever stops being fun, that will be the end of it. I appreciate that it’s a good tool for getting the word out about my publishing efforts, but people can tell when self-promotion is delivered with a sense of joy and when it’s delivered out of a sense of duty. At least that’s true of the discerning folks who take an interest in my writing.I’ve posted previously about my friend’s reading of my poem “Black Skull,” so I won’t go into a lot of detail here, but since it is the first video to live on the new YouTube channel, here it is again:As for video number two, it’s the quickest of updates about my story “InPerson,” which is out now in the Dig Two Graves, Vol. II anthology from Death’s Head Press. If you have a couple of minutes to spare, here’s that video:Don’t forget to subscribe to the channel if you’d like to be kept abreast of my writing news. And feel free to say hello in the comments. Till next time ...

Published on August 07, 2019 20:31

July 31, 2019

Inevitability and the One-Way Mirror of Social Media

I honestly don’t know how some writers are able to post as much as they do on social media, not to mention get good at it. I work a full-time job and have a family—not to mention other interests—yet I make sure I write every day (yes, of course I miss a day here and there to sickness or despair, but mostly it’s every day). That means every lunch break, every weekend, and as many weeknights as possible are spent toiling away at my craft. This has made me good at what I do, and it’s allowed me to produce two (so far unpublished) novels and a veritable slew of short stories and poems (many published, many not).What my dedication and sacrifice have not done is leave me with the wherewithal to engage in a lot of online monkeyshines at the end of the day. My best writing goes into the work that pays (be it ever so little). My second best writing go into this blog. What I post elsewhere is largely an effort to keep my name in front of people, because recognition can fade fast in the world of letters—especially now that anyone with a smidge of computer literacy can make yet another shitty book appear in the world and distract eyeballs from work of merit (whether self-published or not).Part of the problem is that you have to enjoy social media to use it well, as with anything. Well, sometimes I can love social media a little bit, but only a little bit … and not very often, or for very long. That’s a problem, because its value to writers is obvious. You can use it to peddle your wares, of course. It also connects you with books and writers you want to be made aware of. It brings to your attention potential markets for submitting your work. It even allows you to interact with the occasional bigwig. And of course there truly is a sense of community lurking beneath the surface of snide puffery and popularity-contest congeniality that dominates.But is social media good for us as human beings? I’m not sure this question matters very much when it comes to technology. Launch first and ask questions later. That’s the 21st-century mindset. Whatever comes as a consequence can be written off as inevitable. Change comes too quickly for much to be done about it. How can this not be leading us to a precipice? It reminds me of a line that Robin Williams once delivered in an interview with David Letterman (maybe one of his stock lines at the time): “I was violating my standards faster than I could lower them.” Is that inevitability or simply the shunning of responsibility (even if only for comic effect)?Maybe, in the end, social media truly is an inevitable by-product of the Internet, though. Remember when everyone in the late ’90s was hollering about what a game-changer the Internet was? Well, it turns out they were right. Social media is part of the changed game, just like one-click purchasing from our phones, 24/7 streaming of music and movies, and open access to most of the world’s greatest literature. You know, content. (That’s become inevitable, too.)Anyway, you don’t like the glitz and glaze of the technological era? Go ahead and carry on without social media. But can you? Can you really, as a writer, make it without Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, at a minimum? Who would spread the word of your accomplishments? Your mom? Your cat? Some days I think I’m on the brink of finding out for myself. Part of me wants to leave it all behind and continue scribbling away in obscurity until I stumble upon the agent/editor/publisher who places as little value on my “social media platform” as I do.Hell, maybe I’m just getting old. I guess it was inevitable.

I honestly don’t know how some writers are able to post as much as they do on social media, not to mention get good at it. I work a full-time job and have a family—not to mention other interests—yet I make sure I write every day (yes, of course I miss a day here and there to sickness or despair, but mostly it’s every day). That means every lunch break, every weekend, and as many weeknights as possible are spent toiling away at my craft. This has made me good at what I do, and it’s allowed me to produce two (so far unpublished) novels and a veritable slew of short stories and poems (many published, many not).What my dedication and sacrifice have not done is leave me with the wherewithal to engage in a lot of online monkeyshines at the end of the day. My best writing goes into the work that pays (be it ever so little). My second best writing go into this blog. What I post elsewhere is largely an effort to keep my name in front of people, because recognition can fade fast in the world of letters—especially now that anyone with a smidge of computer literacy can make yet another shitty book appear in the world and distract eyeballs from work of merit (whether self-published or not).Part of the problem is that you have to enjoy social media to use it well, as with anything. Well, sometimes I can love social media a little bit, but only a little bit … and not very often, or for very long. That’s a problem, because its value to writers is obvious. You can use it to peddle your wares, of course. It also connects you with books and writers you want to be made aware of. It brings to your attention potential markets for submitting your work. It even allows you to interact with the occasional bigwig. And of course there truly is a sense of community lurking beneath the surface of snide puffery and popularity-contest congeniality that dominates.But is social media good for us as human beings? I’m not sure this question matters very much when it comes to technology. Launch first and ask questions later. That’s the 21st-century mindset. Whatever comes as a consequence can be written off as inevitable. Change comes too quickly for much to be done about it. How can this not be leading us to a precipice? It reminds me of a line that Robin Williams once delivered in an interview with David Letterman (maybe one of his stock lines at the time): “I was violating my standards faster than I could lower them.” Is that inevitability or simply the shunning of responsibility (even if only for comic effect)?Maybe, in the end, social media truly is an inevitable by-product of the Internet, though. Remember when everyone in the late ’90s was hollering about what a game-changer the Internet was? Well, it turns out they were right. Social media is part of the changed game, just like one-click purchasing from our phones, 24/7 streaming of music and movies, and open access to most of the world’s greatest literature. You know, content. (That’s become inevitable, too.)Anyway, you don’t like the glitz and glaze of the technological era? Go ahead and carry on without social media. But can you? Can you really, as a writer, make it without Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, at a minimum? Who would spread the word of your accomplishments? Your mom? Your cat? Some days I think I’m on the brink of finding out for myself. Part of me wants to leave it all behind and continue scribbling away in obscurity until I stumble upon the agent/editor/publisher who places as little value on my “social media platform” as I do.Hell, maybe I’m just getting old. I guess it was inevitable.

Published on July 31, 2019 11:22

June 26, 2019

Publishing Updates

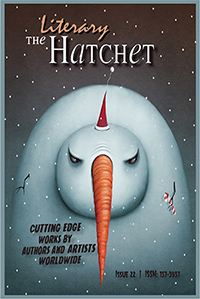

Since there are some neat writerly things around the corner for me—and more neat writerly things that might maybe possibly be around the next corner soonish if the stars align—I thought I’d sit down and post an update for you good and loyal people. Here’s the nutshell version of my 2019 so far: Why not start with January 2. You can already read the publication deets on my narrative poem, “Black Skull,” because it came out in issue 22 of The Literary Hatchet. Click on the image to the left for my post about that.The only additional news about “Black Skull” is that exclusivity with The Literary Hatchet ends at the beginning of August. I’m kind of looking forward to that because it means I’ll be able to re-post a video I made with my radio-announcer friend reading the poem in voiceover. I think it turned out pretty good, in a no-budget, heartfelt, atmospheric way. You’ll be the first to know when that video is available again.Moving on, I sold a revenge story to the anthology Dig Two Graves, Vol. 2 from Death’s Head Press. Volume 1 is already available as an e-book and as a paperback, so volume 2 should be landing pretty soon (they read for both volumes simultaneously). I have a fun blog idea in mind for these books, too. This is the first I’ve hinted at it, but it would be fun to interview some of my fellow contributors. Because there are quite a few stories in each book, my choices would seem to be A) pick a handful of favorites from each and interview those authors; or B) skip volume 1 and try to interview all contributors for volume 2. Either way I’ll be leaving out a lot of great contributors, so I’m not sure how to proceed. While you’re waiting for me to decide, have a look at the covers:

Why not start with January 2. You can already read the publication deets on my narrative poem, “Black Skull,” because it came out in issue 22 of The Literary Hatchet. Click on the image to the left for my post about that.The only additional news about “Black Skull” is that exclusivity with The Literary Hatchet ends at the beginning of August. I’m kind of looking forward to that because it means I’ll be able to re-post a video I made with my radio-announcer friend reading the poem in voiceover. I think it turned out pretty good, in a no-budget, heartfelt, atmospheric way. You’ll be the first to know when that video is available again.Moving on, I sold a revenge story to the anthology Dig Two Graves, Vol. 2 from Death’s Head Press. Volume 1 is already available as an e-book and as a paperback, so volume 2 should be landing pretty soon (they read for both volumes simultaneously). I have a fun blog idea in mind for these books, too. This is the first I’ve hinted at it, but it would be fun to interview some of my fellow contributors. Because there are quite a few stories in each book, my choices would seem to be A) pick a handful of favorites from each and interview those authors; or B) skip volume 1 and try to interview all contributors for volume 2. Either way I’ll be leaving out a lot of great contributors, so I’m not sure how to proceed. While you’re waiting for me to decide, have a look at the covers:

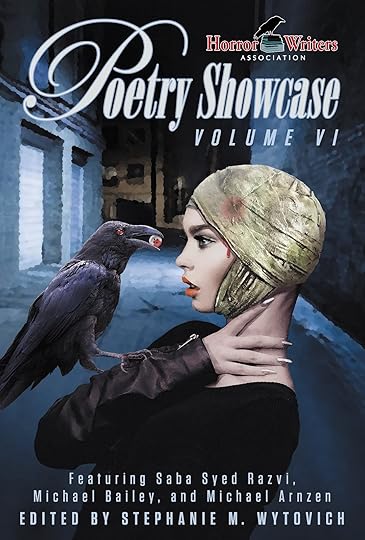

My most recent sale was another poem: “A Return to Chaos.” This one found a home in the forthcoming sixth volume of the Poetry Showcase series from the Horror Writers Association. Here’s a look at the eye-catching cover:

My most recent sale was another poem: “A Return to Chaos.” This one found a home in the forthcoming sixth volume of the Poetry Showcase series from the Horror Writers Association. Here’s a look at the eye-catching cover:

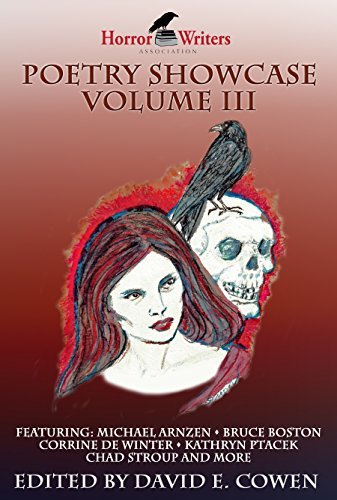

It’s pleasing to have a second poem in the series, my first being “Gratitude” in volume 3. If you’re wondering why I don’t have more short stories floating around out there right now, it’s because I’m trying to be a bit more collection-centric. It’s kind of tricky to balance a desire to publish stand-alone stories with continuing to own the rights to enough material to publish a collection if the opportunity arises. Well, the pay off is that I have my next three collections planned out. Two of them are complete, while the third still needs some work. And I do have some excellent stories out in the marketplace as well, so I’m very excited to see where some of these threads lead.You know where to check back for updates. Of course, I'm also on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Until next time ...

It’s pleasing to have a second poem in the series, my first being “Gratitude” in volume 3. If you’re wondering why I don’t have more short stories floating around out there right now, it’s because I’m trying to be a bit more collection-centric. It’s kind of tricky to balance a desire to publish stand-alone stories with continuing to own the rights to enough material to publish a collection if the opportunity arises. Well, the pay off is that I have my next three collections planned out. Two of them are complete, while the third still needs some work. And I do have some excellent stories out in the marketplace as well, so I’m very excited to see where some of these threads lead.You know where to check back for updates. Of course, I'm also on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Until next time ...

Why not start with January 2. You can already read the publication deets on my narrative poem, “Black Skull,” because it came out in issue 22 of The Literary Hatchet. Click on the image to the left for my post about that.The only additional news about “Black Skull” is that exclusivity with The Literary Hatchet ends at the beginning of August. I’m kind of looking forward to that because it means I’ll be able to re-post a video I made with my radio-announcer friend reading the poem in voiceover. I think it turned out pretty good, in a no-budget, heartfelt, atmospheric way. You’ll be the first to know when that video is available again.Moving on, I sold a revenge story to the anthology Dig Two Graves, Vol. 2 from Death’s Head Press. Volume 1 is already available as an e-book and as a paperback, so volume 2 should be landing pretty soon (they read for both volumes simultaneously). I have a fun blog idea in mind for these books, too. This is the first I’ve hinted at it, but it would be fun to interview some of my fellow contributors. Because there are quite a few stories in each book, my choices would seem to be A) pick a handful of favorites from each and interview those authors; or B) skip volume 1 and try to interview all contributors for volume 2. Either way I’ll be leaving out a lot of great contributors, so I’m not sure how to proceed. While you’re waiting for me to decide, have a look at the covers:

Why not start with January 2. You can already read the publication deets on my narrative poem, “Black Skull,” because it came out in issue 22 of The Literary Hatchet. Click on the image to the left for my post about that.The only additional news about “Black Skull” is that exclusivity with The Literary Hatchet ends at the beginning of August. I’m kind of looking forward to that because it means I’ll be able to re-post a video I made with my radio-announcer friend reading the poem in voiceover. I think it turned out pretty good, in a no-budget, heartfelt, atmospheric way. You’ll be the first to know when that video is available again.Moving on, I sold a revenge story to the anthology Dig Two Graves, Vol. 2 from Death’s Head Press. Volume 1 is already available as an e-book and as a paperback, so volume 2 should be landing pretty soon (they read for both volumes simultaneously). I have a fun blog idea in mind for these books, too. This is the first I’ve hinted at it, but it would be fun to interview some of my fellow contributors. Because there are quite a few stories in each book, my choices would seem to be A) pick a handful of favorites from each and interview those authors; or B) skip volume 1 and try to interview all contributors for volume 2. Either way I’ll be leaving out a lot of great contributors, so I’m not sure how to proceed. While you’re waiting for me to decide, have a look at the covers:

My most recent sale was another poem: “A Return to Chaos.” This one found a home in the forthcoming sixth volume of the Poetry Showcase series from the Horror Writers Association. Here’s a look at the eye-catching cover:

My most recent sale was another poem: “A Return to Chaos.” This one found a home in the forthcoming sixth volume of the Poetry Showcase series from the Horror Writers Association. Here’s a look at the eye-catching cover:

It’s pleasing to have a second poem in the series, my first being “Gratitude” in volume 3. If you’re wondering why I don’t have more short stories floating around out there right now, it’s because I’m trying to be a bit more collection-centric. It’s kind of tricky to balance a desire to publish stand-alone stories with continuing to own the rights to enough material to publish a collection if the opportunity arises. Well, the pay off is that I have my next three collections planned out. Two of them are complete, while the third still needs some work. And I do have some excellent stories out in the marketplace as well, so I’m very excited to see where some of these threads lead.You know where to check back for updates. Of course, I'm also on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Until next time ...

It’s pleasing to have a second poem in the series, my first being “Gratitude” in volume 3. If you’re wondering why I don’t have more short stories floating around out there right now, it’s because I’m trying to be a bit more collection-centric. It’s kind of tricky to balance a desire to publish stand-alone stories with continuing to own the rights to enough material to publish a collection if the opportunity arises. Well, the pay off is that I have my next three collections planned out. Two of them are complete, while the third still needs some work. And I do have some excellent stories out in the marketplace as well, so I’m very excited to see where some of these threads lead.You know where to check back for updates. Of course, I'm also on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Until next time ...

Published on June 26, 2019 17:33

March 2, 2019

The Films of Richard Matheson, Part 4 of 4

In the 1970s, Richard Matheson became associated with director Dan Curtis for a number of television movies, much as he had become inseparable from Roger Corman's Poe films in the '60s. But there was another co-conspirator this time around, maybe the musical equivalent of Vincent Price during the Poe period. Robert Cobert, who also worked with Curtis on the Dark Shadows program, composed the music for six of the television films that Matheson and Curtis worked on together, and the music was terribly important in all of them. The theme from The Night Stalker (produced but not directed by Curtis) and The Night Strangler (produced and directed by Curtis) alternates between a driving, disco-rock beat (very of its time) and an eerie kind of spatial thrum: an aural representation of the horrors that lurk beneath the sarcasm of those films. This sensation of things being chaotic under the thin ice of false security is brought across even more effectively in Cobert's score for Scream of the Wolf, though the theme itself isn't as memorable as the one used for the Kolchak films. Cobert captures something in these scores that goes beyond mere aptness for the individual films. His music has an awareness to it that hints of the very methods by which Richard Matheson operates in his fiction as well as his scripts. Yes, this is Las Vegas, the music assures us in The Night Stalker. Yes, this is Seattle, it concurs in The Night Strangler. But something is very, very wrong.Cobert's other three scores for Curtis and Matheson were Dracula, Trilogy of Terror, and Dead of Night. Of course, Dracula demanded a very different style of music, and Cobert came through with an elaborate orchestral score, punctuated here and there with great savagery. And the eerily quiet music that plays over the closing credits is a haunting coda to a highly effective adaptation of the famous vampire story. In Trilogy of Terror and Dead of Night we hear the most traditional horror music of the bunch. Notes leap from various woodwind instruments at crazy intervals, creating a slow, creeping mood that goes along very nicely with the psychological terror of the films.In a special feature for the DVD of Dracula, director Dan Curtis states emphatically that Jack Palance is the scariest screen count that ever was. [RM: Except (I feel) for his over-size fangs.] I'm not inclined to argue. Christopher Lee brought a certain sophistication to the role that will never be topped. And Frank Langella captured the romantic inclinations of the character. But Jack Palance is good and scary, for sure. Matheson's script for Dracula introduces a love story between Dracula and Mina, and it's amazing to see how much better it works here than in Francis Ford Coppola's overwrought rendition. [RM: We originated the idea. Coppola's film copied it.] There's great pain in Matheson's Dracula, but it only fuels his rage. When the count discovers that Mina has been staked in her coffin, his reaction runs the emotional gamut from grief to inhuman hatred. It's not only one of the most effective scenes of the film, but of any Dracula film I've seen. Part of this, again, is owing to Cobert's startling music, but it's really a clear case of all things coming together in harmony: writing, direction, acting and music. [RM: It should have been three-hours long—which the original cut was.]

In the 1970s, Richard Matheson became associated with director Dan Curtis for a number of television movies, much as he had become inseparable from Roger Corman's Poe films in the '60s. But there was another co-conspirator this time around, maybe the musical equivalent of Vincent Price during the Poe period. Robert Cobert, who also worked with Curtis on the Dark Shadows program, composed the music for six of the television films that Matheson and Curtis worked on together, and the music was terribly important in all of them. The theme from The Night Stalker (produced but not directed by Curtis) and The Night Strangler (produced and directed by Curtis) alternates between a driving, disco-rock beat (very of its time) and an eerie kind of spatial thrum: an aural representation of the horrors that lurk beneath the sarcasm of those films. This sensation of things being chaotic under the thin ice of false security is brought across even more effectively in Cobert's score for Scream of the Wolf, though the theme itself isn't as memorable as the one used for the Kolchak films. Cobert captures something in these scores that goes beyond mere aptness for the individual films. His music has an awareness to it that hints of the very methods by which Richard Matheson operates in his fiction as well as his scripts. Yes, this is Las Vegas, the music assures us in The Night Stalker. Yes, this is Seattle, it concurs in The Night Strangler. But something is very, very wrong.Cobert's other three scores for Curtis and Matheson were Dracula, Trilogy of Terror, and Dead of Night. Of course, Dracula demanded a very different style of music, and Cobert came through with an elaborate orchestral score, punctuated here and there with great savagery. And the eerily quiet music that plays over the closing credits is a haunting coda to a highly effective adaptation of the famous vampire story. In Trilogy of Terror and Dead of Night we hear the most traditional horror music of the bunch. Notes leap from various woodwind instruments at crazy intervals, creating a slow, creeping mood that goes along very nicely with the psychological terror of the films.In a special feature for the DVD of Dracula, director Dan Curtis states emphatically that Jack Palance is the scariest screen count that ever was. [RM: Except (I feel) for his over-size fangs.] I'm not inclined to argue. Christopher Lee brought a certain sophistication to the role that will never be topped. And Frank Langella captured the romantic inclinations of the character. But Jack Palance is good and scary, for sure. Matheson's script for Dracula introduces a love story between Dracula and Mina, and it's amazing to see how much better it works here than in Francis Ford Coppola's overwrought rendition. [RM: We originated the idea. Coppola's film copied it.] There's great pain in Matheson's Dracula, but it only fuels his rage. When the count discovers that Mina has been staked in her coffin, his reaction runs the emotional gamut from grief to inhuman hatred. It's not only one of the most effective scenes of the film, but of any Dracula film I've seen. Part of this, again, is owing to Cobert's startling music, but it's really a clear case of all things coming together in harmony: writing, direction, acting and music. [RM: It should have been three-hours long—which the original cut was.] Trilogy of Terror and Dead of Night are both made up of short segments. Karen Black stars in all three of the stories in Trilogy of Terror, the last being a terrifying adaptation of Matheson's story, "Prey," in which the protagonist brings home a Zuni fetish doll with the intention of giving it to her boyfriend as a gift, only to discover that it has a life of its own. The pacing of "Prey," both as a story and a short film, is enough to thin the blood. "Amelia," as the segment is called for the film, is the only one of the three that was actually scripted by Matheson. The other two, "Julie" and "Millicent and Therese," were based on his stories but adapted by William F. Nolan.The first story in Dead of Night is called "Second Chance." It stars Ed Begley, Jr., and though not necessarily cleverer than "No Such Thing as a Vampire" or "Bobby"—the stories that follow—it serves as a fascinating prelude to a Matheson film discussed in more detail below: 1980's Somewhere in Time. Both are concerned with a protagonist who must travel back in time in order to meet the love of his life. Matheson adapted his own novel for Somewhere in Time, while his script for "Second Chance" was actually based on a Jack Finney story. Somewhere in Time is a more complicated affair, but "Second Chance" draws its considerable charm from the same well.The Legend of Hell House, released in 1973, is another one of the oddities in Matheson's career, set apart from his collaborative periods. It's based on one of his most cherished books, Hell House, and though it's not perhaps as faithful an adaptation as it could have been, it stands on its own marvelously. [RM: Too much censorship at the time—pre-Exorcist.] But even as a Richard Matheson novel, Hell House is somewhat odd. Famous for scaring the daylights out of readers without relying on Gothic trappings, here the author has written an honest-to-God haunted house story. And oh my, what a house. I think it's safe to say that Matheson's title is a nod to Shirley Jackson, [RM: Of course.] but the scientific realism of the story is all his own.What the film version of Matheson's novel lacks is the orgiastic hedonism that was so strong a part of Belasco House's past in the book. Emeric Belasco was (is) the master of Hell House, and his carousal in life has left certain indelible traces in the woodwork. In that regard, the film could have used a touch of the eroticism found all over De Sade. [RM: I don't know why Hell House was tamed compared to De Sade, although I don't think De Sade was all that erotic anyway. But maybe it was because Hell House was made in England, and maybe because they were more fastidious. Maybe because it was James Nicholson's first production upon leaving American International and he didn't want to do anything offensive. I don't know, but as I said, I don't really think De Sade was all that erotic anyway.]Yet The Legend of Hell House remains one of the great all-time haunted-house movies. John Hough's direction and Alan Hume's photography are meticulous in balancing the characterization of the house with the characterization of the people who arrive there to put an end to its legacy of terror. And the cast plays its collective role with dreadful certainty. Roddy McDowall is especially enjoyable as Benjamin Franklin Fischer, who has previously done battle with Hell House and carries with him the unseen scars of that experience.A career as long and productive as Richard Matheson's is bound to include at least one film that becomes something of a phenomenon. In Matheson's case that film is the already alluded to Somewhere in Time. And there really is a kind of magic to the film. In fact, writing about it feels a little like yelling, "MacBeth!" in an empty theater. There are certain spells that just shouldn't be broken. But surely a few words ...Perhaps no other film with Matheson's name attached to it illustrates as clearly the acrobatic ease with which he navigates the borderland between realism and romanticism. And seldom is a novel adapted for the screen so brilliantly. The novel, originally titled Bid Time Return but since renamed to match the movie, is a very accomplished piece of writing, [RM: My best, I think.] and by 1980, of course, Matheson was no stranger to the differences between writing prose fiction and writing for motion pictures, so the disparities that exist between the novel and the film version of Somewhere in Time are easily swallowed.There's a simple kind of perfection to the casting of Jane Seymour and Christopher Reeve as lovers who must reach across time in order to unite. And Jeannot Szwarc seems ideally suited to the subject matter as the director of the film. [RM: Absolutely!] Who, watching the Matheson-penned Night Gallery episode that Szwarc directed in 1970 ("The Big Surprise"), would have guessed that the two would collaborate a decade later on one of the greatest screen romances ever filmed?

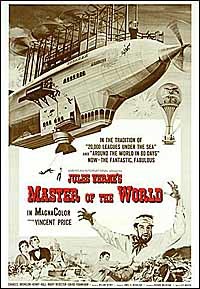

Trilogy of Terror and Dead of Night are both made up of short segments. Karen Black stars in all three of the stories in Trilogy of Terror, the last being a terrifying adaptation of Matheson's story, "Prey," in which the protagonist brings home a Zuni fetish doll with the intention of giving it to her boyfriend as a gift, only to discover that it has a life of its own. The pacing of "Prey," both as a story and a short film, is enough to thin the blood. "Amelia," as the segment is called for the film, is the only one of the three that was actually scripted by Matheson. The other two, "Julie" and "Millicent and Therese," were based on his stories but adapted by William F. Nolan.The first story in Dead of Night is called "Second Chance." It stars Ed Begley, Jr., and though not necessarily cleverer than "No Such Thing as a Vampire" or "Bobby"—the stories that follow—it serves as a fascinating prelude to a Matheson film discussed in more detail below: 1980's Somewhere in Time. Both are concerned with a protagonist who must travel back in time in order to meet the love of his life. Matheson adapted his own novel for Somewhere in Time, while his script for "Second Chance" was actually based on a Jack Finney story. Somewhere in Time is a more complicated affair, but "Second Chance" draws its considerable charm from the same well.The Legend of Hell House, released in 1973, is another one of the oddities in Matheson's career, set apart from his collaborative periods. It's based on one of his most cherished books, Hell House, and though it's not perhaps as faithful an adaptation as it could have been, it stands on its own marvelously. [RM: Too much censorship at the time—pre-Exorcist.] But even as a Richard Matheson novel, Hell House is somewhat odd. Famous for scaring the daylights out of readers without relying on Gothic trappings, here the author has written an honest-to-God haunted house story. And oh my, what a house. I think it's safe to say that Matheson's title is a nod to Shirley Jackson, [RM: Of course.] but the scientific realism of the story is all his own.What the film version of Matheson's novel lacks is the orgiastic hedonism that was so strong a part of Belasco House's past in the book. Emeric Belasco was (is) the master of Hell House, and his carousal in life has left certain indelible traces in the woodwork. In that regard, the film could have used a touch of the eroticism found all over De Sade. [RM: I don't know why Hell House was tamed compared to De Sade, although I don't think De Sade was all that erotic anyway. But maybe it was because Hell House was made in England, and maybe because they were more fastidious. Maybe because it was James Nicholson's first production upon leaving American International and he didn't want to do anything offensive. I don't know, but as I said, I don't really think De Sade was all that erotic anyway.]Yet The Legend of Hell House remains one of the great all-time haunted-house movies. John Hough's direction and Alan Hume's photography are meticulous in balancing the characterization of the house with the characterization of the people who arrive there to put an end to its legacy of terror. And the cast plays its collective role with dreadful certainty. Roddy McDowall is especially enjoyable as Benjamin Franklin Fischer, who has previously done battle with Hell House and carries with him the unseen scars of that experience.A career as long and productive as Richard Matheson's is bound to include at least one film that becomes something of a phenomenon. In Matheson's case that film is the already alluded to Somewhere in Time. And there really is a kind of magic to the film. In fact, writing about it feels a little like yelling, "MacBeth!" in an empty theater. There are certain spells that just shouldn't be broken. But surely a few words ...Perhaps no other film with Matheson's name attached to it illustrates as clearly the acrobatic ease with which he navigates the borderland between realism and romanticism. And seldom is a novel adapted for the screen so brilliantly. The novel, originally titled Bid Time Return but since renamed to match the movie, is a very accomplished piece of writing, [RM: My best, I think.] and by 1980, of course, Matheson was no stranger to the differences between writing prose fiction and writing for motion pictures, so the disparities that exist between the novel and the film version of Somewhere in Time are easily swallowed.There's a simple kind of perfection to the casting of Jane Seymour and Christopher Reeve as lovers who must reach across time in order to unite. And Jeannot Szwarc seems ideally suited to the subject matter as the director of the film. [RM: Absolutely!] Who, watching the Matheson-penned Night Gallery episode that Szwarc directed in 1970 ("The Big Surprise"), would have guessed that the two would collaborate a decade later on one of the greatest screen romances ever filmed? Though Somewhere in Time is a fantasy that cleverly avoids the use of any kind of machinery to achieve the time travel necessary for the story to be told, science fiction buffs—particularly time-travel buffs—may treasure the central paradox of the film. Elise McKenna, as an old woman, approaches Robert Collier (Reeve) in the present time of the story, presses a pocket watch into his hand, and urgently whispers, "Come back to me," before leaving him forever. Later, when Collier has successfully traveled back in time to be with the young Elise (Seymour), with whose photograph he has by this time fallen in love, he gives her the very same pocket watch as a gift. The question of when and where that watch was crafted is a tantalizing one. [RM: I knew it was an impossibility as soon as I wrote it but my producer and director loved it.]Believe it or not, there are a handful of Matheson's films and television movies that have not been discussed here. Some, like Dying Room Only, Cold Sweat, and Stir of Echoes, are excellent but resisted inclusion for logistical reasons. Others, like It's Alive (the Larry Buchanan-directed film, not the Larry Cohen one), simply do not bear the Matheson mark, to put it kindly. Still others couldn't be tracked down in a timely fashion, if at all. [RM: The two best of the non-fantasy films are The Morning After and The Dreamer of Oz.]But what thread runs through the films that have been discussed? What is it exactly that gives Richard Matheson such a distinctive cinematic voice? Perhaps the strongest theme to emerge from a survey of his work in television and motion pictures is that some lessons can only be learned in captivity. [RM: Good point.] It's an idea he returns to again and again in his fiction as well. For some of his characters, imprisonment is an obvious physical reality. Scott Carey is trapped in his own cellar. Robert Neville becomes a prisoner in his own home. Patricia, in Die! Die! My Darling!, is incarcerated in Mrs. Trefoille's house. Master of the World's John Strock is held against his will aboard The Albatross. Others are caught up in prisons of conscience. Karl Kolchak in The Night Stalker and The Night Strangler, for instance, is forced into the role of Cassandra, and though it means he's bound to be ridiculed and ignored, he will not relent in his pursuit of the truth.But to dwell on thematic concerns is to miss the point of what Matheson has proven so many times. Art can, indeed must, entertain. And conversely, entertainment doesn't have to eschew artistic value. It doesn't matter if a piece of fiction is firmly rooted in reality or set entirely on a foreign planet; whether horrifying or sad, thought provoking or humorous, it's all fantasy. And good writing is the only thing that will give it life. Matheson simply knows where our buttons are and how to push them. When someone can do that, his power over us knows few boundaries. We are clay for his wheel. Luckily for us, Richard Matheson's intentions have been benevolent. He just wants to show us the pieces of ourselves that we are too often unwilling to unearth on our own. [RM: Again, thank you, thank you for the kind words.]<< Previous: Part 3<>

Though Somewhere in Time is a fantasy that cleverly avoids the use of any kind of machinery to achieve the time travel necessary for the story to be told, science fiction buffs—particularly time-travel buffs—may treasure the central paradox of the film. Elise McKenna, as an old woman, approaches Robert Collier (Reeve) in the present time of the story, presses a pocket watch into his hand, and urgently whispers, "Come back to me," before leaving him forever. Later, when Collier has successfully traveled back in time to be with the young Elise (Seymour), with whose photograph he has by this time fallen in love, he gives her the very same pocket watch as a gift. The question of when and where that watch was crafted is a tantalizing one. [RM: I knew it was an impossibility as soon as I wrote it but my producer and director loved it.]Believe it or not, there are a handful of Matheson's films and television movies that have not been discussed here. Some, like Dying Room Only, Cold Sweat, and Stir of Echoes, are excellent but resisted inclusion for logistical reasons. Others, like It's Alive (the Larry Buchanan-directed film, not the Larry Cohen one), simply do not bear the Matheson mark, to put it kindly. Still others couldn't be tracked down in a timely fashion, if at all. [RM: The two best of the non-fantasy films are The Morning After and The Dreamer of Oz.]But what thread runs through the films that have been discussed? What is it exactly that gives Richard Matheson such a distinctive cinematic voice? Perhaps the strongest theme to emerge from a survey of his work in television and motion pictures is that some lessons can only be learned in captivity. [RM: Good point.] It's an idea he returns to again and again in his fiction as well. For some of his characters, imprisonment is an obvious physical reality. Scott Carey is trapped in his own cellar. Robert Neville becomes a prisoner in his own home. Patricia, in Die! Die! My Darling!, is incarcerated in Mrs. Trefoille's house. Master of the World's John Strock is held against his will aboard The Albatross. Others are caught up in prisons of conscience. Karl Kolchak in The Night Stalker and The Night Strangler, for instance, is forced into the role of Cassandra, and though it means he's bound to be ridiculed and ignored, he will not relent in his pursuit of the truth.But to dwell on thematic concerns is to miss the point of what Matheson has proven so many times. Art can, indeed must, entertain. And conversely, entertainment doesn't have to eschew artistic value. It doesn't matter if a piece of fiction is firmly rooted in reality or set entirely on a foreign planet; whether horrifying or sad, thought provoking or humorous, it's all fantasy. And good writing is the only thing that will give it life. Matheson simply knows where our buttons are and how to push them. When someone can do that, his power over us knows few boundaries. We are clay for his wheel. Luckily for us, Richard Matheson's intentions have been benevolent. He just wants to show us the pieces of ourselves that we are too often unwilling to unearth on our own. [RM: Again, thank you, thank you for the kind words.]<< Previous: Part 3<>

Published on March 02, 2019 10:56

The Films of Richard Matheson, Part 3 of 4

It's discouraging that one of Richard Matheson's greatest novels, I Am Legend, has yet to be turned into a wholly satisfying film (unless one counts Night of the Living Dead, which doesn't officially credit Matheson's book as a source, but ...). Two attempts have been made, however. The first came in 1964 and starred Vincent Price as Robert Neville, the reluctant vampire-hunter of the story. Matheson wrote the script—which was re-written by William P. Leicester—but is credited under the pen name Logan Swanson. This version, filmed in Italy, comes much closer than the 1971 Charlton Heston vehicle, Omega Man, to capturing the oppressive atmosphere of the novel, but Price proves an unfortunate choice for Matheson's masculine hero, and The Last Man on Earth ends up being ill served by the stagnancy of its direction. As for Omega Man, its primary appeal is for those with an interest in Heston's science fiction period, which also included Soylent Green and The Planet of the Apes. In the end, neither adaptation of I Am Legend is able to convey the sense from the novel that hope itself is outmoded in Neville's apocalyptic world, that a beaten man's only recourse is to fill his hours as productively as possible. But again, The Last Man on Earth comes much closer than Omega Man. [I Am Legend, starring Will Smith, wasn't out yet when this article appeared originally, but sadly it only makes a trilogy of the unsatisfying attempts to adapt the novel.—ed.]In 1965, Matheson scripted the first of two films for the legendary British film studio, Hammer Films. Based on an Anne Blaisdell novel and directed by Silvio Narizzano, Die! Die! My Darling! is the claustrophobic tale of a young woman held prisoner in the house of her one-time fiance's mother. Stephen died before the two were married, and the ancient Mrs. Trefoille (Tallulah Bankhead) blames Patricia for his death. The ending of the film is a bit soft for a Matheson-scripted effort, but you'd have to try pretty hard to care, because overall it's one of Hammer's most successful films in terms of drawing out suspense. And besides, we can't expect every suspense thriller to deliver the kind of satisfying payoff that we get in, say, the film version of Misery—though I must admit that Die! Die! My Darling! could have used a little good old-fashioned revenge in the wrap-up.Patricia, played by a young Stephanie Powers, has returned to London after a prolonged absence to be with her new fiance, Alan. She decides, despite his protests, that her being in England again provides a good opportunity to visit Mrs. Trefoille, who lives in an old country mansion. Think Carrie, The Collector, and Psycho, and you begin to understand the kind of situation into which poor Patricia is about to insert herself, except that Mrs. Trefoille makes Carrie White's mother look rather loose by comparison.

It's discouraging that one of Richard Matheson's greatest novels, I Am Legend, has yet to be turned into a wholly satisfying film (unless one counts Night of the Living Dead, which doesn't officially credit Matheson's book as a source, but ...). Two attempts have been made, however. The first came in 1964 and starred Vincent Price as Robert Neville, the reluctant vampire-hunter of the story. Matheson wrote the script—which was re-written by William P. Leicester—but is credited under the pen name Logan Swanson. This version, filmed in Italy, comes much closer than the 1971 Charlton Heston vehicle, Omega Man, to capturing the oppressive atmosphere of the novel, but Price proves an unfortunate choice for Matheson's masculine hero, and The Last Man on Earth ends up being ill served by the stagnancy of its direction. As for Omega Man, its primary appeal is for those with an interest in Heston's science fiction period, which also included Soylent Green and The Planet of the Apes. In the end, neither adaptation of I Am Legend is able to convey the sense from the novel that hope itself is outmoded in Neville's apocalyptic world, that a beaten man's only recourse is to fill his hours as productively as possible. But again, The Last Man on Earth comes much closer than Omega Man. [I Am Legend, starring Will Smith, wasn't out yet when this article appeared originally, but sadly it only makes a trilogy of the unsatisfying attempts to adapt the novel.—ed.]In 1965, Matheson scripted the first of two films for the legendary British film studio, Hammer Films. Based on an Anne Blaisdell novel and directed by Silvio Narizzano, Die! Die! My Darling! is the claustrophobic tale of a young woman held prisoner in the house of her one-time fiance's mother. Stephen died before the two were married, and the ancient Mrs. Trefoille (Tallulah Bankhead) blames Patricia for his death. The ending of the film is a bit soft for a Matheson-scripted effort, but you'd have to try pretty hard to care, because overall it's one of Hammer's most successful films in terms of drawing out suspense. And besides, we can't expect every suspense thriller to deliver the kind of satisfying payoff that we get in, say, the film version of Misery—though I must admit that Die! Die! My Darling! could have used a little good old-fashioned revenge in the wrap-up.Patricia, played by a young Stephanie Powers, has returned to London after a prolonged absence to be with her new fiance, Alan. She decides, despite his protests, that her being in England again provides a good opportunity to visit Mrs. Trefoille, who lives in an old country mansion. Think Carrie, The Collector, and Psycho, and you begin to understand the kind of situation into which poor Patricia is about to insert herself, except that Mrs. Trefoille makes Carrie White's mother look rather loose by comparison. What is Mrs. Trefoille's problem, exactly, apart from the loss of her son? Well, she doesn't appear to have gotten over her husband's passing some years ago, for one thing. He died the year Stephen was born, incidentally. There's mention of an acting career in the stern woman's past, too. But mostly Mrs. Trefoille has found religion, and one aspect of her interpretation of that religion is that she views marital engagement to be as strong a bond as marriage itself. Poor, poor Patricia. She's forced to give up lipstick, and the color red is strictly verboten. Only the plainest fare is served in the Trefoille household, and breakfast every morning is laid out only after an interminable Biblical sermon has been read by the lady of the house.In the beginning, Patricia isn't aware that she won't be allowed to leave, and the dynamic between her and Mrs. Trefoille is almost playful. But we're usually kept a step ahead of Patricia, so dread is never out of reach as we watch the story unfold. Once Patricia starts to appreciate the gravity of her situation, however, a new element of fun is introduced. Seeing that she has nothing to lose, the heroine acts with increasing boldness toward Mrs. Trefoille, whose reactions range from incredulous shock to outbursts of wickedness.What the film does best is to make the audience believe repeatedly that maybe this time Patricia is going to escape from the clutches of Mrs. Trefoille, only to dash our hopes again and again. There's a particularly effective moment after Mrs. Trefoille leaves Patricia alone in her room and takes the captive's untouched meal with her out of anger. Patricia finds a scrap of food on the floor and lunges for it like a hungry dog. She brings it to her lips before realizing what she's been reduced to. Disgusted, she tosses the scrap aside and gathers the resolve to make her first escape attempt.By the time Alan finally gets around to searching for his intended, we've begun to wonder if he'll ever get the job done. In a scene that foreshadows that painful close-up in Halloween when Dr. Loomis looks first one way and then the other while Michael Myers glides behind him in his dirty green station wagon, Alan walks right past Mrs. Trefoille's servant, Anna, on his way into a grocery store not far from the Trefoille estate. He tries to insist on interrupting a business transaction at the counter in order to ask the cashier where exactly Mrs. Trefoille's house is located. But the cashier takes the upper hand and forces him to wait his turn. Anna overhears Alan try to interrogate the cashier and manages to rush back to the house ahead of him. Again Patricia is denied reprieve, for Mrs. Trefoille is given just enough warning of Alan's imminent arrival to gag her prisoner, compose herself and, when he does show up, convince Alan that Patricia has left several days ago. Alan's apple-red roadster almost cracks the old lady's veneer of sanity, but she manages to hold it together long enough to watch him drive off into the sunset. As already mentioned, the ending beyond this point might have been stronger, but there's no good reason to reveal every last detail to the curious reader.

What is Mrs. Trefoille's problem, exactly, apart from the loss of her son? Well, she doesn't appear to have gotten over her husband's passing some years ago, for one thing. He died the year Stephen was born, incidentally. There's mention of an acting career in the stern woman's past, too. But mostly Mrs. Trefoille has found religion, and one aspect of her interpretation of that religion is that she views marital engagement to be as strong a bond as marriage itself. Poor, poor Patricia. She's forced to give up lipstick, and the color red is strictly verboten. Only the plainest fare is served in the Trefoille household, and breakfast every morning is laid out only after an interminable Biblical sermon has been read by the lady of the house.In the beginning, Patricia isn't aware that she won't be allowed to leave, and the dynamic between her and Mrs. Trefoille is almost playful. But we're usually kept a step ahead of Patricia, so dread is never out of reach as we watch the story unfold. Once Patricia starts to appreciate the gravity of her situation, however, a new element of fun is introduced. Seeing that she has nothing to lose, the heroine acts with increasing boldness toward Mrs. Trefoille, whose reactions range from incredulous shock to outbursts of wickedness.What the film does best is to make the audience believe repeatedly that maybe this time Patricia is going to escape from the clutches of Mrs. Trefoille, only to dash our hopes again and again. There's a particularly effective moment after Mrs. Trefoille leaves Patricia alone in her room and takes the captive's untouched meal with her out of anger. Patricia finds a scrap of food on the floor and lunges for it like a hungry dog. She brings it to her lips before realizing what she's been reduced to. Disgusted, she tosses the scrap aside and gathers the resolve to make her first escape attempt.By the time Alan finally gets around to searching for his intended, we've begun to wonder if he'll ever get the job done. In a scene that foreshadows that painful close-up in Halloween when Dr. Loomis looks first one way and then the other while Michael Myers glides behind him in his dirty green station wagon, Alan walks right past Mrs. Trefoille's servant, Anna, on his way into a grocery store not far from the Trefoille estate. He tries to insist on interrupting a business transaction at the counter in order to ask the cashier where exactly Mrs. Trefoille's house is located. But the cashier takes the upper hand and forces him to wait his turn. Anna overhears Alan try to interrogate the cashier and manages to rush back to the house ahead of him. Again Patricia is denied reprieve, for Mrs. Trefoille is given just enough warning of Alan's imminent arrival to gag her prisoner, compose herself and, when he does show up, convince Alan that Patricia has left several days ago. Alan's apple-red roadster almost cracks the old lady's veneer of sanity, but she manages to hold it together long enough to watch him drive off into the sunset. As already mentioned, the ending beyond this point might have been stronger, but there's no good reason to reveal every last detail to the curious reader. The other Hammer film that Matheson worked on is The Devil Rides Out, a beloved Christopher Lee vehicle from Dennis Wheatley's novel, directed by the inimitable Terence Fisher. When we think of Satanic horror films these days, "Rosemary's Baby" seems the obvious progenitor, but "The Devil Rides Out" was released the same year as Roman Polanski's literal translation of the Ira Levin classic (1968). It is, of course, required viewing (the novel is also highly engrossing).I suppose we can call De Sade Matheson's art film, put out by AIP in 1969. In an interview on the DVD, Matheson clarifies a very important point about the film: his script did not indicate for it to be shot as a linear narrative, but rather as a series of mental flashbacks from the infamous Marquis de Sade's deathbed. The powers that be felt Matheson's approach would be too hard to follow and so they changed the structure of the story. The biggest problem with this is that virtually every scene was written to be a distortion of reality at the hands of de Sade's disjointed memory of events, which director Cy Endfield captures beautifully, but without cluing the audience in to the reasons behind the disjointedness until the very end of the film. It's a wonderful example of how the writer's role in the filmmaking process is easily overlooked, or misunderstood.1971 saw the airing of Duel, which has made white-knuckle drivers out of countless late night television viewers ever since. Dennis Weaver plays a man—David Mann, actually—terrorized nearly to death by an 18-wheeler on a desolate stretch of California highway. I say he's pursued by the truck itself because we never see more than the hirsute arm of the driver.The plot is really that simple, proving that just about any idea can be sculpted into a story, but a good film is more than the sum of its ideas. A universe needs to be crafted in which the story is allowed to unfold. That universe doesn't have to play by our rules, but hopefully it plays by its own. Otherwise there's bound to be a lack of consistency to the picture. The desert universe of Duel is documented with a pretty busy camera. When it's important that we see the speedometer, director Steven Spielberg shows it to us. When we need to see Mann slap at the steering wheel out of frustration and terror, Spielberg shows us that. And just when you think a moment's reprieve from the tension might be in sight, there's a new threat for Mann to overcome. But it's amazing how many shots in the film are precisely indicated in Matheson's original story. I imagine that the script served as a very clear blueprint indeed. [RM: It did.]

The other Hammer film that Matheson worked on is The Devil Rides Out, a beloved Christopher Lee vehicle from Dennis Wheatley's novel, directed by the inimitable Terence Fisher. When we think of Satanic horror films these days, "Rosemary's Baby" seems the obvious progenitor, but "The Devil Rides Out" was released the same year as Roman Polanski's literal translation of the Ira Levin classic (1968). It is, of course, required viewing (the novel is also highly engrossing).I suppose we can call De Sade Matheson's art film, put out by AIP in 1969. In an interview on the DVD, Matheson clarifies a very important point about the film: his script did not indicate for it to be shot as a linear narrative, but rather as a series of mental flashbacks from the infamous Marquis de Sade's deathbed. The powers that be felt Matheson's approach would be too hard to follow and so they changed the structure of the story. The biggest problem with this is that virtually every scene was written to be a distortion of reality at the hands of de Sade's disjointed memory of events, which director Cy Endfield captures beautifully, but without cluing the audience in to the reasons behind the disjointedness until the very end of the film. It's a wonderful example of how the writer's role in the filmmaking process is easily overlooked, or misunderstood.1971 saw the airing of Duel, which has made white-knuckle drivers out of countless late night television viewers ever since. Dennis Weaver plays a man—David Mann, actually—terrorized nearly to death by an 18-wheeler on a desolate stretch of California highway. I say he's pursued by the truck itself because we never see more than the hirsute arm of the driver.The plot is really that simple, proving that just about any idea can be sculpted into a story, but a good film is more than the sum of its ideas. A universe needs to be crafted in which the story is allowed to unfold. That universe doesn't have to play by our rules, but hopefully it plays by its own. Otherwise there's bound to be a lack of consistency to the picture. The desert universe of Duel is documented with a pretty busy camera. When it's important that we see the speedometer, director Steven Spielberg shows it to us. When we need to see Mann slap at the steering wheel out of frustration and terror, Spielberg shows us that. And just when you think a moment's reprieve from the tension might be in sight, there's a new threat for Mann to overcome. But it's amazing how many shots in the film are precisely indicated in Matheson's original story. I imagine that the script served as a very clear blueprint indeed. [RM: It did.] Interestingly, Spielberg has said that he views Jaws as a kind of sequel to Duel. Matheson is credited as one of the screenwriters for Jaws 3, but that's pretty much the end of that unnecessary sequel's appeal. [RM: It could have been a lot better if my script had been left alone.]Critics have not been as kind to the work Spielberg and Matheson put into Twilight Zone: The Movie in 1983 as they have to Duel. When the film is mentioned at all, it's often in terms of the tragedy that befell the shooting of one of its segments. But the very fact that it's a collage film is of interest to Matheson fans who have long associated him with the form. The segment with the strongest attachment to Matheson is the remake of the famous episode from the original series, "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet," which in both cases was scripted by Matheson and based on his story. So similar is the remake to the original that it amounts to little more than a case of bringing certain things up to date, especially the look of the creature on the wing, which has always been the Achilles heel of the otherwise superb original. John Lithgow is terrific as the horrified passenger and sole witness to the elusive monster in the 1983 version, but so was William Shatner in the classic Twilight Zone episode. [RM: Far more interesting in that Shatner's character, newly and only partially recovered from a mental breakdown, is resisting the experience as much as he can.] In an age when sequels and remakes have become the earmark of Hollywood's aversion to risk, I suppose it's pointless to fret over Spielberg and Matheson's mild retelling of what is often touted by Twilight Zone fans as their favorite episode. Both versions are great fun in their own way. [I'm cautiously optimistic about Jordan Peele's forthcoming adaptation of this same story for his Twilight Zone reboot.—ed.]<<>Next: Part 4 >>

Interestingly, Spielberg has said that he views Jaws as a kind of sequel to Duel. Matheson is credited as one of the screenwriters for Jaws 3, but that's pretty much the end of that unnecessary sequel's appeal. [RM: It could have been a lot better if my script had been left alone.]Critics have not been as kind to the work Spielberg and Matheson put into Twilight Zone: The Movie in 1983 as they have to Duel. When the film is mentioned at all, it's often in terms of the tragedy that befell the shooting of one of its segments. But the very fact that it's a collage film is of interest to Matheson fans who have long associated him with the form. The segment with the strongest attachment to Matheson is the remake of the famous episode from the original series, "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet," which in both cases was scripted by Matheson and based on his story. So similar is the remake to the original that it amounts to little more than a case of bringing certain things up to date, especially the look of the creature on the wing, which has always been the Achilles heel of the otherwise superb original. John Lithgow is terrific as the horrified passenger and sole witness to the elusive monster in the 1983 version, but so was William Shatner in the classic Twilight Zone episode. [RM: Far more interesting in that Shatner's character, newly and only partially recovered from a mental breakdown, is resisting the experience as much as he can.] In an age when sequels and remakes have become the earmark of Hollywood's aversion to risk, I suppose it's pointless to fret over Spielberg and Matheson's mild retelling of what is often touted by Twilight Zone fans as their favorite episode. Both versions are great fun in their own way. [I'm cautiously optimistic about Jordan Peele's forthcoming adaptation of this same story for his Twilight Zone reboot.—ed.]<<>Next: Part 4 >>

Published on March 02, 2019 10:56

The Films of Richard Matheson, Part 2 of 4