Nancy K. Miller's Blog

March 14, 2024

March 1997 / March 2024, Part 9: In Plain Sight

“I was not, and would never be, in love with her, nor she with me.

I was the stuff of which literary executors, not muses, are made.”

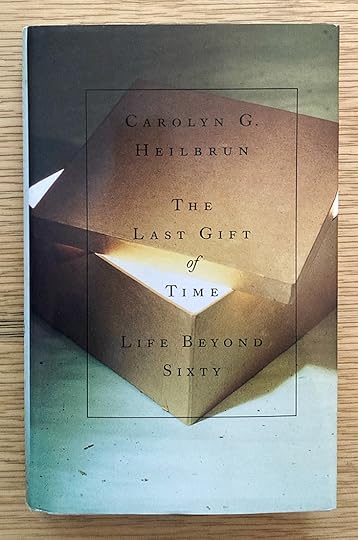

— Carolyn Heilbrun, The Last Gift of Time: Life After Sixty

I’ve placed my copy of Carolyn’s first letter to May Sarton on my desk, next to the published account of her long friendship with Sarton: “A Unique Person.” I’m puzzling over the contrast in tone between the language of the Carolyn I did not know in 1968 and the author of a memoir published in 1997 whom I thought I knew quite well.

Almost 20 years after sending that letter, Carolyn revisits her initial excitement about Sarton’s writing.

My reading of her 1968 memoir, Plant Dreaming Deep, a work that quite literally caught me in its spell, was the beginning of our friendship. Rereading that book today, I still encounter what excited me; I still hear her voice speaking to me of life’s possibilities. ‘We have to make myths of our lives,’ she wrote. ‘It is the only way to live without despair.’ Sarton’s wisdom was, for me as for many, a support and a promise offered by someone who had been there before and could explain the journey.

I want to understand the story of these two women’s friendship as it evolved between those dates, the bookends, so to speak, of a literary relationship. Who was forty-something Carolyn in 1968? Why did Sarton’s work seem so compelling at that stage of her life? Most of all, what for her was the journey that needed explaining?

I doubt that it occurred to any of us, the many women who were mentored by Carolyn, and for whom she was the one “who had been there before,” that she herself might have wished for, not to say needed, that someone. “They will know that there are books waiting for them,” she observed in late career, “as there were no books waiting for me.” The absence of books, however, was not the only resource Carolyn knew she lacked when embarking on the journey of a writer’s life. At Columbia, during her long years teaching there, she found neither support nor wisdom, egregiously no mentorship, no guidance for the journey at all.

What was it exactly about Plant Dreaming Deep that so captivated Carolyn, as she would write, decades later: “…. at the time I read it, I was beguiled, bewitched. I wrote to her and we met.” How the relationship between the two women evolved from those initial magical feelings — “beguiled” and “bewitched” — I do not pretend to know. What, beyond the literary executor narrative, is in fact knowable? Should it be? Nonetheless, this is what I’ve embarked on, inching my way through their long correspondence: from Carolyn’s electrifying encounter with Plant Dreaming Deep in 1968 to her memorializing Sarton in The Last Gift of Time in 1997. In other words, my journey. (Oh, so is this all about me again?)

“Her place in my life was simply in being May Sarton.” Does unique necessarily mean simple? Isn’t theirs rather exactly the kind of story of friendship between women, between women writers, which In Writing a Woman’s Life, Carolyn declared sadly missing from the annals of biography? Recall, for example, her account of the intense and intimate bond between Winifred Holtby and Vera Brittain, a literary and loving friendship that she celebrated, not to say idealized. It feels a little scary, maybe even wrong to keep wondering, wandering through the archive, as if I were expecting to unveil the meaning of a relationship I had so completely missed during Carolyn’s life time, during the years of our long friendship. It’s equally hard to resist.

Dear Readers, in the end I aspire only to share with you how I got here, how I’ve come to see in these letters something like what Carolyn used to call a subtext.

I’m also haunted, not to say warned off, by the sealing of the narrative condensed in Carolyn’s last words: “The journey is over. Love to all.” That journey.

The post March 1997 / March 2024, Part 9: In Plain Sight appeared first on Nancy K. Miller.

February 20, 2024

1970 / February 2024, Part 8: “Dear woman”

In her reply to Carolyn’s harsh critique of her novels, Sarton takes the high road: “Dear woman,” she protests (and I love this), “you simply cannot use the categorical imperative,” with her. She’s a writer, after all, and goes on to defend her aim as a fiction writer: to portray “a positive vision of life” in contrast to the “homosexual novel” that shows “deviance through its most degraded aspect.” It takes courage and “a stubborn will to survive,” she proudly declares, and in “survival there is triumph.”

Two years after her original fan mail, Carolyn explains her impulsive gesture: “it was written because I wanted to reach you, I guess…” Carolyn continues, almost surprised by her expression of need: “you would never guess from it how reticent and ungiven to personal remarks I usually am,” adding that she “regretted the letter as soon as it was gone.” Then a step further in this uncharacteristic mode of insecurity, she admits to her fear that Sarton would write her off “as a mistake.”

The effect of reading these letters for the first time jarred me out of any conviction I had enjoyed in thinking I knew my friend well, even intimately. I could not recognize the tone of this writing. I still cannot. Carolyn fearing she’d be written off as a mistake—a mistake! —was not the woman whose unapologetic confidence I had spent more than twenty years admiring.

Carolyn highlights Sarton’s “need to ‘fight it out’” as expressed in her works, which she shares: “I want to fight about conventions sometime too.” Which conventions? And what exactly of Sarton’s universe fascinates Carolyn? “You affirm life and reveal what has not been seen before.” Here is what she finds exciting: Sarton’s “ability to affirm, to embody, new loves” and experiences, “relationships for which the language has not yet been found.”

In what feels now unbearably touching to me, Carolyn (now Carol to May) in a postscript offers to send Sarton a detective novel she had published under the pseudonym Amanda Cross, without naming herself as its author. A coy moment.

Two letters from Sarton to Carolyn at the Berg came in a separate folder from Carolyn’s letters but along with them. (I believe that Sarton kept the originals of Carolyn’s letters and that the ones in the NYPL belong to the Sarton archive. Carolyn’s papers are at Smith.) These look to be battered copies of carbons on paper that had turned brown with age. Sarton begins her reply to Carolyn’s most recent letter, explaining that she had had house guests and no time for letter writing. After an anecdote about her furnace on the blink and her parrot shivering with cold (these details of country living will continue to punctuate the correspondence), Sarton plunges into the epistolary exchange with enthusiasm and admiration. She dismisses Carolyn’s anxiety that she’d be rejected or ignored (“written off”). On the contrary, her arrival on the scene, Sarton reassures her, was “one of the very best things” that could have happened and looks forward to their meeting “face to face.”

Carolyn never hides her reservations about Sarton’s novels, which, unlike the poems and autobiographical works do not, she feels, “fully embody” Sarton’s vision. And tacitly accepts Sarton’s resistance to her categorical imperative. “I cannot tell you what to write,” she acknowledges, almost reluctantly, but “what a relief to be categorical for once and get away with it.” (When did Carolyn not get away with being categorical, one of her major modes?)

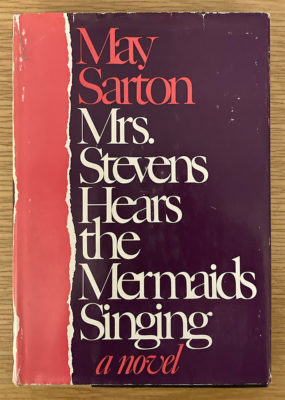

In turn, Sarton, defends her work as a novelist, with references to Jane Austen and Turgenev, reminding Carolyn that a lot takes place “between the lines.” Then with no segue, in the very same paragraph, she shares her view of the Amanda Cross detective novel Carolyn had sent her. Sarton does not mince words: she found the book “terribly boring,” not to mention “pretentious” and “academic.” By contrast, in a long single spaced second page, she goes on to celebrate her accomplishments as a writer, praising her own 1965 novel, Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing, as a triumph. Sarton then compares her accomplishment at having created a portrait of “the woman as homosexual artist in a fictional form” that is more successful than Woolf’s in A Room of One’s Own. (!) Modesty is never her strong suit.

Sarton finally signs off expressing her desire to continue working on what will become the “journal of solitude,” and wishing Carolyn the same for the book she is working on, the book on androgyny. (Both books would be published in 1973.)

The post 1970 / February 2024, Part 8: “Dear woman” appeared first on Nancy K. Miller.

February 7, 2024

December 1970 / January 2024, Part 7: Epistolary Fervor

Over the past decade, students have been thrilled by their forays into the archive. I’ve been skeptical but also intrigued by their fascination — both what hooks them and why, especially when lured by the siren song of the epistolary. And so here I am limply following in their path, intrigued by the promises of truth and revelation that letters seem to hold. I’m also drifted back in memory, caught in the nets of the 18th-century epistolary novel, where my own graduate student days began. But it’s as though I had not remembered that those correspondences were fictional. I’m reading in full flush of naiveté, almost forgetting that my 20th-century characters both wrote fiction themselves.

Were the letters I composed for over sixty pre-email years a wholly veracious account of what I felt at the time? I may well have thought so in the moment of writing. I hope so now.

Dear Reader, please bear with me: I’m taking these letters between two prolific women writers à la lettre, as if I were I’m following the traces of a transparently true story. A story whose origins were first retrieved here, in the archive.

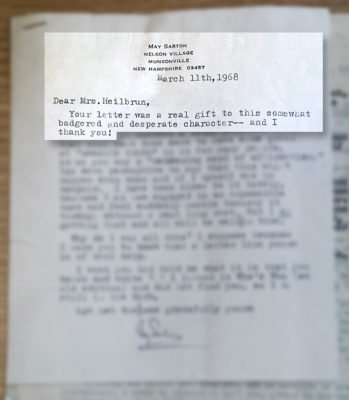

“Dear Mrs. Heilbrun,” Sarton writes, March 11th, 1968, answering Carolyn’s first letter almost immediately. Her reply arrives typed on personalized note paper with the identical format as Carolyn’s with the home address printed in blue ink at the top of the page. Sarton thanks Carolyn for her letter and responds to her flattering comments about Plant Dreaming Deep. Carolyn had been “perceptive,” about her writing, she acknowledges, adding that she found the letter “of real help.” But wait. Who exactly is this new correspondent? Sarton had hadn’t found Carolyn up in an “old edition” of Who’s Who (how important could she be?). Despite feeling herself “still in the dark” about Carolyn’s status, Sarton signs off with expressions of gratitude.

The correspondence picks up again in the winter of 1970. Carolyn reminds Sarton that she had sent a letter praising Plant Dreaming Deep, the previous March. She has since been busy reading everything that Sarton has written (a lot) and confesses to feeling “seized with a desire” to write about her work. To that end, Carolyn sends articles and reviews already published by her that she hopes will persuade Sarton that this is a good idea. Carolyn describes herself, in response to Sarton’s earlier request to know more about her, noting her book contract and advance with Knopf, and a grant from the Guggenheim to finish the book. Nonetheless, despite these previous commitments, she wants to write about Sarton, and proposes that they meet. She’d even travel to New Hampshire if Sarton doesn’t plan to come to New York.

Sarton not surprisingly admits to being “thrilled” at the idea that Carolyn would write about her work. And launches the complaint she will continue to make for the rest of her very successful career: Despite having received some flattering reviews, she has “suffered from having had almost no serious critical attention.” Carolyn, she’s convinced, will change all this, get Sarton the recognition she deserves.

Carolyn’s letter of December 7, addressed this time to May Sarton (the Miss is gone), is almost two office size single-spaced pages filled with suggestions on how Sarton might improve her novel writing technique. Carolyn does not tread lightly. Sarton’s next novel, she insists “must not make use of a narrative voice.” Rather, she suggests, Sarton should follow Henry James’s narrative practice of “single consciousness in The Ambassadors.” The reader’s “awareness” should align with that of the central character, that is to say, Strether’s.

(Very near Carolyn’s suicide, in a last and posthumous essay about reading, rereading, and how to live, Strether and The Ambassadors return. It’s as though for Carolyn, that novel almost literally names the inner quandary at the heart of a writer’s life, and she refers to James elsewhere in writing to Sarton. While I find it hard to recognize anything remotely “Jamesian” in Sarton’s fiction — or in Carolyn’s detective fiction, for that matter — I can only ponder Carolyn’s own long, fervent attachment to the author.)

Carolyn’s letter is filled with as much praise as critique. The autobiographical works, she declares (no hedging), are “superb because of the voice you have found,” and that what Sarton says in that voice is something completely new and important especially for women artists. “You are a poet, and with a poet’s voice”; Sarton should “construct a novel as though it were a poem, as you have done with the autobiographical works.” The letter ends both with an apology for the comments and an expression of faith in Sarton’s future: “You will become quite a figure, before you’re done.”

The seeds of transaction are planted deep, very deep.

The post December 1970 / January 2024, Part 7: Epistolary Fervor appeared first on Nancy K. Miller.

January 29, 2024

1968 / 2024, Part 6: Ulysses Redux

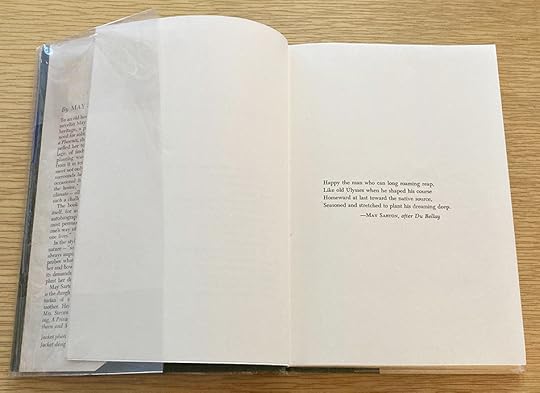

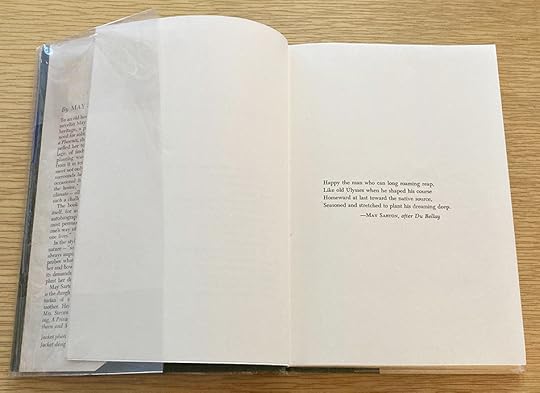

A thought experiment. Suppose I had read Brooks Atkinson’s review (see part 5) and bought May Sarton’s memoir Plant Dreaming Deep. I would certainly have been arrested at the door by the author’s use of a famous sixteenth-century French poem as an epigraph to situate her project: “Heureux celui qui, comme Ulysse, a fait un beau voyage.” The poem’s title is also its first line in which Du Bellay imagines the return of Ulysses to Ithaca: “Happy the man who…”

Sarton translates freely the first 3 lines and then invents the 4th. That line contains the phrase that gives her memoir its title. In Du Bellay’s 4th line, the hero returns to the land of his ancestors: “To live with his parents the rest of his life.” In Sarton’s version, “old Ulysses” returns: “Seasoned and stretched to plant his dreaming deep.” Sarton has made other changes in her translation to serve her own journey, but this line is the most deeply transformed.

Here’s where I stumbled: Sarton is not returning home to live the rest of her life in her parents’ ancestral land. It’s just the opposite. In the first chapter of the memoir, Sarton describes in detail, the importance of transporting her deceased parents’ furniture (originally from Belgium, where she was born) to her new chosen home in New Hampshire. Sarton’s “ancestor” is the portrait of an eighteenth-century gentleman, with a posh name: Duvet de la Tour. According to Sarton’s parents, he was “the ancestor, as if there had been no others” (17).

In 1968, I suspect that I would have wanted to save Du Bellay from Sarton’s recreation, not least because that line “Seasoned and stretched to plant his dreaming deep” simply does not scan for me. In his review, Atkinson comments that “the esoteric title derives from one of her own verses” (well, she does sign, “after Du Bellay”). Esoteric is one way of reading it. That line still doesn’t make any sense to me, whether the planting is material (i.e. a function of gardening) or symbolic, imagined. Certainly, it has nothing to do with Ulysses.

So, ok, I imagine I would have, frowned at Sarton’s gesture. What, she has rewritten the meaning of this classic poem to cast herself as the hero of her life, only in reverse? I’m sure that had I encountered the lines in 1968, I would have rebelled. Why frame your very American project with a classic of 16th-century French literature?

I was nothing if not a rabid Francophile.

She has violated the original.

But that was before French feminists transformed the classics in the 1970s: Hélène Cixous’ “The Laugh of the Medusa,” for example, in which feminists liberate the language and its ancient myths to suit their own needs. Now (post 1968), I can freely ponder the wholly invented fourth line: What might it mean to plant your dreaming deep? I might even embrace the innovation, as Carolyn did, and try to understand why Sarton created this metaphor to account for her project. I’m not there yet, though, I’ve begun to see through the correspondence, how deeply (that word) self-mythification attracts the Carolyn of 1968.

Better Ulysses than Penelope?

The post 1968 / 2024, Part 6: Ulysses Redux appeared first on Nancy K. Miller.

1968 / 2024: Part 6: Ulysses Redux

A thought experiment. Suppose I had read Brooks Atkinson’s review (see part 5) and bought May Sarton’s memoir Plant Dreaming Deep. I would certainly have been arrested at the door by the author’s use of a famous sixteenth-century French poem as an epigraph to situate her project: “Heureux celui qui, comme Ulysse, a fait un beau voyage.” The poem’s title is also its first line in which Du Bellay imagines the return of Ulysses to Ithaca: “Happy the man who…”

Sarton translates freely the first 3 lines and then invents the 4th. That line contains the phrase that gives her memoir its title. In Du Bellay’s 4th line, the hero returns to the land of his ancestors: “To live with his parents the rest of his life.” In Sarton’s version, “old Ulysses” returns: “Seasoned and stretched to plant his dreaming deep.” Sarton has made other changes in her translation to serve her own journey, but this line is the most deeply transformed.

Here’s where I stumbled: Sarton is not returning home to live the rest of her life in her parents’ ancestral land. It’s just the opposite. In the first chapter of the memoir, Sarton describes in detail, the importance of transporting her deceased parents’ furniture (originally from Belgium, where she was born) to her new chosen home in New Hampshire. Sarton’s “ancestor” is the portrait of an eighteenth-century gentleman, with a posh name: Duvet de la Tour. According to Sarton’s parents, he was “the ancestor, as if there had been no others” (17).

In 1968, I suspect that I would have wanted to save Du Bellay from Sarton’s recreation, not least because that line “Seasoned and stretched to plant his dreaming deep” simply does not scan for me. In his review, Atkinson comments that “the esoteric title derives from one of her own verses” (well, she does sign, “after Du Bellay”). Esoteric is one way of reading it. That line still doesn’t make any sense to me, whether the planting is material (i.e. a function of gardening) or symbolic, imagined. Certainly, it has nothing to do with Ulysses.

So, ok, I imagine I would have, frowned at Sarton’s gesture. What, she has rewritten the meaning of this classic poem to cast herself as the hero of her life, only in reverse? I’m sure that had I encountered the lines in 1968, I would have rebelled. Why frame your very American project with a classic of 16th-century French literature?

I was nothing if not a rabid Francophile.

She has violated the original.

But that was before French feminists transformed the classics in the 1970s: Hélène Cixous’ “The Laugh of the Medusa,” for example, in which feminists liberate the language and its ancient myths to suit their own needs. Now (post 1968), I can freely ponder the wholly invented fourth line: What might it mean to plant your dreaming deep? I might even embrace the innovation, as Carolyn did, and try to understand why Sarton created this metaphor to account for her project. I’m not there yet, though, I’ve begun to see through the correspondence, how deeply (that word) self-mythification attracts the Carolyn of 1968.

Better Ulysses than Penelope?

The post 1968 / 2024: Part 6: Ulysses Redux appeared first on Nancy K. Miller.

1968/2024: Interlude, 5–6: Ulysses Redux

A thought experiment. Suppose I had read Brooks Atkinson’s review (see part 5) and bought May Sarton’s memoir Plant Dreaming Deep. I would certainly have been arrested at the door by the author’s use of a famous sixteenth-century French poem as an epigraph to situate her project: “Heureux celui qui, comme Ulysse, a fait un beau voyage.” The poem’s title is also its first line in which Du Bellay imagines the return of Ulysses to Ithaca: “Happy the man who…”

Sarton translates freely the first 3 lines and then invents the 4th. That line contains the phrase that gives her memoir its title. In Du Bellay’s 4th line, the hero returns to the land of his ancestors: “To live with his parents the rest of his life.” In Sarton’s version, “old Ulysses” returns: “Seasoned and stretched to plant his dreaming deep.” Sarton has made other changes in her translation to serve her own journey, but this line is the most deeply transformed.

Here’s where I stumbled: Sarton is not returning home to live the rest of her life in her parents’ ancestral land. It’s just the opposite. In the first chapter of the memoir, Sarton describes in detail, the importance of transporting her deceased parents’ furniture (originally from Belgium, where she was born) to her new chosen home in New Hampshire. Sarton’s “ancestor” is the portrait of an eighteenth-century gentleman, with a posh name: Duvet de la Tour. According to Sarton’s parents, he was “the ancestor, as if there had been no others” (17).

In 1968, I suspect that I would have wanted to save Du Bellay from Sarton’s recreation, not least because that line “Seasoned and stretched to plant his dreaming deep” simply does not scan for me. In his review, Atkinson comments that “the esoteric title derives from one of her own verses” (well, she does sign, “after Du Bellay”). Esoteric is one way of reading it. That line still doesn’t make any sense to me, whether the planting is material (i.e. a function of gardening) or symbolic, imagined. Certainly, it has nothing to do with Ulysses.

So, ok, I imagine I would have, frowned at Sarton’s gesture. What, she has rewritten the meaning of this classic poem to cast herself as the hero of her life, only in reverse? I’m sure that had I encountered the lines in 1968, I would have rebelled. Why frame your very American project with a classic of 16th-century French literature?

I was nothing if not a rabid Francophile.

She has violated the original.

But that was before French feminists transformed the classics in the 1970s: Hélène Cixous’ “The Laugh of the Medusa,” for example, in which feminists liberate the language and its ancient myths to suit their own needs. Now (post 1968), I can freely ponder the wholly invented fourth line: What might it mean to plant your dreaming deep? I might even embrace the innovation, as Carolyn did, and try to understand why Sarton created this metaphor to account for her project. I’m not there yet, though, I’ve begun to see through the correspondence, how deeply (that word) self-mythification attracts the Carolyn of 1968.

Better Ulysses than Penelope?

The post 1968/2024: Interlude, 5–6: Ulysses Redux appeared first on Nancy K. Miller.

January 16, 2024

March 1968 Encore / January 2024

Admission: About me.

I’ve been stuck for over a month, unable to continue the narrative, still troubled, almost paralyzed by my late life discovery about my friend Carolyn Heilbrun’s fan letter to May Sarton.

What did this mean and why did it matter to me? Or why did it seem to matter so much? Enough to send me down a rabbit hole of archival research and self-doubt. After all, Carolyn and I didn’t agree on everything. We in fact enjoyed our obvious differences in taste and style. Carolyn had celebrated, even exaggerated those differences in the preface we co-wrote to an anthology we republished in the book series during the early ‘90s. And I hope I’m not naïve enough to have imagined that she couldn’t surprise me. Since she often did. Well, clearly, I was.

We tended to acknowledge and understand what we liked and didn’t like about books and writers. I always deferred to Carolyn about British modernism, of course, and understood, if did not always share her tastes. Not only had Carolyn and I talked about books by other writers and by ourselves, but we had taught together, published a book series together, and I had witnessed over and over the acuity of her judgment. It’s also true that by the time I began to know Carolyn, in real life as we say now, almost a decade later she was in a different phase of her life.

So why care? Why care so much?

Worse still, how stupid am I to cling doggedly to the truth available in the archive since the chances are that I will in the end be no further advanced than when I started? If it’s the truth? Let’s be postmodern about this. Or why not just follow along in a critical voyage of discovery. Now in the spirit of docility and academic perseverance, and to offer another token of good faith, I will add these two pages to the reading I proposed earlier of Carolyn’s first fan letter to May Sarton. I return to my baby steps as a student in French, a dogged explication de texte, keeping myself out of it. And then try to move on to understand the power of the evolving relationship between these two women.

I have the sense that I will continue to fail but I’m equally compelled to continue without being happy. (She persisted.) Here’s an embarrassing nugget: I don’t want Carolyn to like May Sarton. Their Chloe and Olivia show makes me feel lonely.

Enough about me.

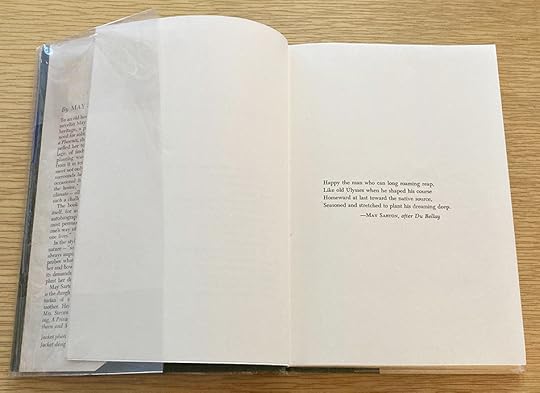

NB: Reminder: the entire collection of Carolyn’s letters can be consulted at the Berg (NYPL). For posting online I will follow the practice of fair use, limiting myself to snippets as in the letter attached here.

What autobiographical work by women writers, I’ve wondered, might Carolyn have read that made Plant Dreaming Deep feel to her like a shock, a revelation of something entirely new? Mary McCarthy’s experimental Memories of a Catholic Girlhood, for example, was well received in 1957 and McCarthy seen as a writer to take seriously. Here’s a line from Charles Poore in The New York Times: “her book is the most incisive contribution to the story of her development as an artist that we shall ever have.” (May 18, 1957). He is dazzled by the tour de force of the form itself. Carolyn would no doubt have demurred. Among other things, McCarthy was famously no feminist, and, as we used to say in the 70s, male identified.

I’ve also been struggling to figure out how I might have read Sarton’s memoir in 1968, had I been aware of her work. What would I have been reading in the sixties? I was pretty male identified myself.

I had lived in France throughout most of the sixties. I left Paris in the summer of 1967 in a state of abject failure six years after my arrival — if only. What I had been reading, and trying to enact, in those years, was the erotic literature of Georges Bataille, on the heels of writing a master’s essay on Les Liaisons dangereuses. Inspired by my reading, sex with men was my main preoccupation, in literature as in life, and in a city. So was structuralism and narratology in their critical popularity.

The books by women that I remember reading and feeling that I was encountering something entirely new were Doris Lessing’s 1962 The Golden Notebook and the first volume of Simone de Beauvoir’s memoirs, Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, that I read in French in a friend’s heavily underlined pocket edition in 1964. The story of Beauvoir’s quest for independence in the memoir inspired me: that was exactly what I was in the process of doing, trying my best, and generally failing to break the hold my parents had over me, even at a distance. I envied Beauvoir’s friendship with Zaza, a relationship that powerfully shaped her future thinking about women’s lives.

The Golden Notebook fascinated me, both because of its style — the four notebooks — and its portraits of independent women living lives away from home in London. Lessing for years resisted and outright rejected the label “feminist” for the book, though finally accepted its legacy decades later — a book passed on between women, between generations—but feminist was not a word on my critical or emotional horizon either.

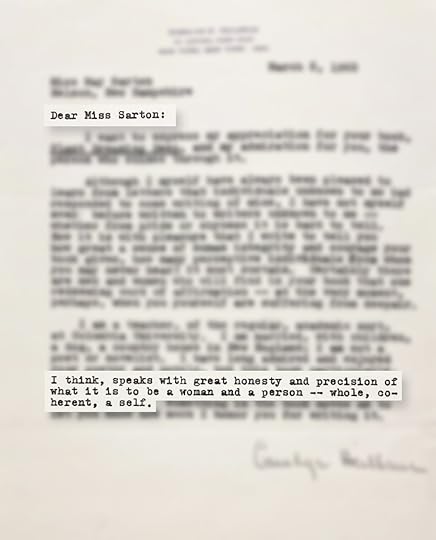

When I try to imagine what it would have felt like to discover Plant Dreaming Deep in 1968, I turn to the concluding lines of an enthusiastic review by Brooks Atkinson in the New York Times: “Love is the genius of this small, but tender and often poignant, book by a woman of many insights.” (February 4, 1968). Atkinson was a well-respected and well-known critic of that era, sometimes referred to as the “Dean” of theater critics. Would his glowing review have persuaded me to read a memoir about a woman in mid-life who moves to the country alone and renovates an 18th-century house? Through writing and gardening in solitude (there are, however, cats and a parrot, not to mention the contractors, workers, and a few friends who visit), she creates a vita nuova. Depressed as I was to be back in New York, my expat life a ruined dream, I would have remained unmoved by a paean to country life. I still am.

The post March 1968 Encore / January 2024 appeared first on Nancy K. Miller.

December 1, 2023

1968 / 2023 Friendship Stories, Part 4: Fan Mail

This past April, I read, in a state of shock, the first letter my friend Carolyn G. Heilbrun sent to the writer May Sarton. Dated March 8, 1968, it was a typed, single-spaced letter on personalized stationery, with Carolyn’s name (no title) and the enviable Central Park address. From its very first line, the letter unsettled almost everything I thought I knew about my friend’s literary tastes and enthusiasms. (For the backstory on this correspondence between Carolyn Heilbrun and May Sarton, view Parts 1, 2, 3)

“Dear Miss Sarton:

I want to express my appreciation for your book, Plant Dreaming Deep,” and “admiration for you, the person who shines through it.” (Plant Dreaming Deep had been published in January of that year.) Carolyn explains that while she had received fan mail herself, she had never written to “writers unknown to me.” She had long been a fan of Sarton’s poetry and novels, she adds, but this new book moved her to act wholly out of character.

Notes on quotations from the archive: I will be following the method adopted by the biographer Diane Middlebrook. To comply with fair use, and not depend on permission from literary estates, Diane would use “snippets” when quoting in her biographies, especially strategic in Her Husband, the story of the Plath/Hughes marriage and careers.

Carolyn was not the book’s only fan. In her 1997 biography May Sarton, Margot Peters notes: “readers loved the book, reread it, talked about it, passed it along to friends. By mid-November 1968, Plant Dreaming Deep had sold 11,145 copies and was still moving nicely. Not a runaway success, but a success.” The story in its bare bones: May Sarton, a poet and writer on the cusp of her fifties, buys a house on her own in New Hampshire, situated in a tiny village called Nelson. The book, one might say, is quite literally the detailed story of the house, its repairs and renovations, painting and furnishing, along with portraits of Sarton’s colorful local neighbors, and nature’s transformative effects on her spirit. “Gardens and gardening are central to this myth,” Margot Peters observes, the myth of this amazing village and its inhabitants. “What lifts Plant Dreaming Deep out of the realm of ordinary memoir,” she continues, “is Sarton’s genius for using nature as a metaphor for human life.” The book charts the “creation, of a female cultural heroine.” Carolyn strikes much the same note in her assessment. The book “speaks with great honesty” about what it means to be “a woman and a person — whole, coherent, a self.” She goes further, suggesting that readers may feel sustained by the book, finding words of “affirmation” in the prose of Sarton’s emotional landscape, uplift in the face of despair.

This lyrical Carolyn to me was suddenly an unmet friend, according to her definition, literally and metaphorically. Addressed to a woman its author had not in fact met, the letter struck a note quite different from the typically cool critical discourse that had characterized the essays and reviews of the friend I had followed and read for decades. I had not read Sarton’s memoir when I first read the letter, and so was not, on the moment, able to make my own judgment of the book’s power, to fathom why it had meant so much to Carolyn.

When writing to Sarton for the first time in 1968, Carolyn herself had already created something new, not a memoir like Plant, or the 1965 novel Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing, that Carolyn would write about — and celebrate — many years later as a critic. When describing herself in the letter she states that unlike Sarton, she is neither poet nor novelist, but a “teacher, of the regular, academic sort,” at Columbia University. But what about the detective novels she had been publishing since 1964? Many years later, in Writing a Woman’s Life, Carolyn describes what she needed and wanted to do in her Amanda Cross books, in creating a character, Kate Fansler, a woman unlike herself, thin, rich, and beautiful — a witty, female detective. (She eventually will reveal her identity as Amanda Cross to Sarton, after sending her a copy of Poetic Justice.) Carolyn in this first self-portrait, is married, with children, a husband, “a country house in New England,” and a dog.

When I met Carolyn almost ten years after her first letter to May Sarton, she was married, with a husband (the same one), children, an 18th-century house in the Berkshires, and a dog — maybe a different one. But I would not have guessed who Sarton had been to her then and, as I’m learning, when we met, still was.

More than what I would ever have imagined.

The post 1968 / 2023 Friendship Stories, Part 4: Fan Mail appeared first on Nancy K. Miller.

1968 / 2023 Friendship Stories Part 4: Fan Mail

This past April, I read, in a state of shock, the first letter my friend Carolyn G. Heilbrun sent to the writer May Sarton. Dated March 8, 1968, it was a typed, single-spaced letter on personalized stationery, with Carolyn’s name (no title) and the enviable Central Park address. From its very first line, the letter unsettled almost everything I thought I knew about my friend’s literary tastes and enthusiasms. (For the backstory on this correspondence between Carolyn Heilbrun and May Sarton, view Parts 1, 2, 3)

“Dear Miss Sarton:

I want to express my appreciation for your book, Plant Dreaming Deep,” and “admiration for you, the person who shines through it.” (Plant Dreaming Deep had been published in January of that year.) Carolyn explains that while she had received fan mail herself, she had never written to “writers unknown to me.” She had long been a fan of Sarton’s poetry and novels, she adds, but this new book moved her to act wholly out of character.

Notes on quotations from the archive: I will be following the method adopted by the biographer Diane Middlebrook. To comply with fair use, and not depend on permission from literary estates, Diane would use “snippets” when quoting in her biographies, especially strategic in Her Husband, the story of the Plath/Hughes marriage and careers.

Carolyn was not the book’s only fan. In her 1997 biography May Sarton, Margot Peters notes: “readers loved the book, reread it, talked about it, passed it along to friends. By mid-November 1968, Plant Dreaming Deep had sold 11,145 copies and was still moving nicely. Not a runaway success, but a success.” The story in its bare bones: May Sarton, a poet and writer on the cusp of her fifties, buys a house on her own in New Hampshire, situated in a tiny village called Nelson. The book, one might say, is quite literally the detailed story of the house, its repairs and renovations, painting and furnishing, along with portraits of Sarton’s colorful local neighbors, and nature’s transformative effects on her spirit. “Gardens and gardening are central to this myth,” Margot Peters observes, the myth of this amazing village and its inhabitants. “What lifts Plant Dreaming Deep out of the realm of ordinary memoir,” she continues, “is Sarton’s genius for using nature as a metaphor for human life.” The book charts the “creation, of a female cultural heroine.” Carolyn strikes much the same note in her assessment. The book “speaks with great honesty” about what it means to be “a woman and a person — whole, coherent, a self.” She goes further, suggesting that readers may feel sustained by the book, finding words of “affirmation” in the prose of Sarton’s emotional landscape, uplift in the face of despair.

This lyrical Carolyn to me was suddenly an unmet friend, according to her definition, literally and metaphorically. Addressed to a woman its author had not in fact met, the letter struck a note quite different from the typically cool critical discourse that had characterized the essays and reviews of the friend I had followed and read for decades. I had not read Sarton’s memoir when I first read the letter, and so was not, on the moment, able to make my own judgment of the book’s power, to fathom why it had meant so much to Carolyn.

When writing to Sarton for the first time in 1968, Carolyn herself had already created something new, not a memoir like Plant, or the 1965 novel Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing, that Carolyn would write about — and celebrate — many years later as a critic. When describing herself in the letter she states that unlike Sarton, she is neither poet nor novelist, but a “teacher, of the regular, academic sort,” at Columbia University. But what about the detective novels she had been publishing since 1964? Many years later, in Writing a Woman’s Life, Carolyn describes what she needed and wanted to do in her Amanda Cross books, in creating a character, Kate Fansler, a woman unlike herself, thin, rich, and beautiful — a witty, female detective. (She eventually will reveal her identity as Amanda Cross to Sarton, after sending her a copy of Poetic Justice.) Carolyn in this first self-portrait, is married, with children, a husband, “a country house in New England,” and a dog.

When I met Carolyn almost ten years after her first letter to May Sarton, she was married, with a husband (the same one), children, an 18th-century house in the Berkshires, and a dog — maybe a different one. But I would not have guessed who Sarton had been to her then and, as I’m learning, when we met, still was.

More than what I would ever have imagined.

The post 1968 / 2023 Friendship Stories Part 4: Fan Mail appeared first on Nancy K. Miller.

1968/2023 Friendship Stories Part 4: Fan Mail

This past April, I read, in a state of shock, the first letter my friend Carolyn G. Heilbrun sent to the writer May Sarton. Dated March 8, 1968, it was a typed, single-spaced letter on personalized stationery, with Carolyn’s name (no title) and the enviable Central Park address. From its very first line, the letter unsettled almost everything I thought I knew about my friend’s literary tastes and enthusiasms. (For the backstory on this correspondence between Carolyn Heilbrun and May Sarton, view Parts 1, 2, 3)

“Dear Miss Sarton:

I want to express my appreciation for your book, Plant Dreaming Deep,” and “admiration for you, the person who shines through it.” (Plant Dreaming Deep had been published in January of that year.) Carolyn explains that while she had received fan mail herself, she had never written to “writers unknown to me.” She had long been a fan of Sarton’s poetry and novels, she adds, but this new book moved her to act wholly out of character.

Notes on quotations from the archive: I will be following the method adopted by the biographer Diane Middlebrook. To comply with fair use, and not depend on permission from literary estates, Diane would use “snippets” when quoting in her biographies, especially strategic in Her Husband, the story of the Plath/Hughes marriage and careers.

Carolyn was not the book’s only fan. In her 1997 biography May Sarton, Margot Peters notes: “readers loved the book, reread it, talked about it, passed it along to friends. By mid-November 1968, Plant Dreaming Deep had sold 11,145 copies and was still moving nicely. Not a runaway success, but a success.” The story in its bare bones: May Sarton, a poet and writer on the cusp of her fifties, buys a house on her own in New Hampshire, situated in a tiny village called Nelson. The book, one might say, is quite literally the detailed story of the house, its repairs and renovations, painting and furnishing, along with portraits of Sarton’s colorful local neighbors, and nature’s transformative effects on her spirit. “Gardens and gardening are central to this myth,” Margot Peters observes, the myth of this amazing village and its inhabitants. “What lifts Plant Dreaming Deep out of the realm of ordinary memoir,” she continues, “is Sarton’s genius for using nature as a metaphor for human life.” The book charts the “creation, of a female cultural heroine.” Carolyn strikes much the same note in her assessment. The book “speaks with great honesty” about what it means to be “a woman and a person — whole, coherent, a self.” She goes further, suggesting that readers may feel sustained by the book, finding words of “affirmation” in the prose of Sarton’s emotional landscape, uplift in the face of despair.

This lyrical Carolyn to me was suddenly an unmet friend, according to her definition, literally and metaphorically. Addressed to a woman its author had not in fact met, the letter struck a note quite different from the typically cool critical discourse that had characterized the essays and reviews of the friend I had followed and read for decades. I had not read Sarton’s memoir when I first read the letter, and so was not, on the moment, able to make my own judgment of the book’s power, to fathom why it had meant so much to Carolyn.

When writing to Sarton for the first time in 1968, Carolyn herself had already created something new, not a memoir like Plant, or the 1965 novel Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing, that Carolyn would write about — and celebrate — many years later as a critic. When describing herself in the letter she states that unlike Sarton, she is neither poet nor novelist, but a “teacher, of the regular, academic sort,” at Columbia University. But what about the detective novels she had been publishing since 1964? Many years later, in Writing a Woman’s Life, Carolyn describes what she needed and wanted to do in her Amanda Cross books, in creating a character, Kate Fansler, a woman unlike herself, thin, rich, and beautiful — a witty, female detective. (She eventually will reveal her identity as Amanda Cross to Sarton, after sending her a copy of Poetic Justice.) Carolyn in this first self-portrait, is married, with children, a husband, “a country house in New England,” and a dog.

When I met Carolyn almost ten years after her first letter to May Sarton, she was married, with a husband (the same one), children, an 18th-century house in the Berkshires, and a dog — maybe a different one. But I would not have guessed who Sarton had been to her then and, as I’m learning, when we met, still was.

More than what I would ever have imagined.

The post 1968/2023 Friendship Stories Part 4: Fan Mail appeared first on Nancy K. Miller.