David M. Schwartz's Blog

July 19, 2013

The Next Big Thing

The Next Big Thing? This “next big thing” is not a new social networking site or a wearable computer that cooks dinner when you get hungry. It is an author blog tour.

A blog tour? A blog tour gives those on the tour a chance to meet different authors by way of their blogs. The Next Big Thing began in Australia. Each week a different author answers specific questions about his or her upcoming book. The answers are posted on the author’s blog. Then we get to tag another author (or two or three). On and on it goes.

The tour came to me from my friend, a former member of my critique group (before she abandoned us by moving from northern California to the Georgia coast) and the author of a wide range of charming and informative books, Nancy Raines Day. I am hereby tagging three outstanding authors and friends Matthew Gollub, Vicki Cobb and Rosalyn Schanzer.

All of the authors on the blog tour have answered the same questions. Here they are, with my answers

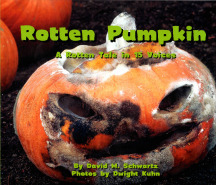

What is the title of your next book?

It’s my rottenest book yet. It’s called Rotten Pumpkin. This is a Halloween book for November, not October because it’s about what happens to the Jack O’Lantern after Halloween. The book has great, gory revolting pictures (and a lot of cute ones, too) by master nature photographer Dwight Kuhn.

It’s my rottenest book yet. It’s called Rotten Pumpkin. This is a Halloween book for November, not October because it’s about what happens to the Jack O’Lantern after Halloween. The book has great, gory revolting pictures (and a lot of cute ones, too) by master nature photographer Dwight Kuhn.

Where did the idea come from for the book?

I have to give credit to Dwight, the photographer, who has been my collaborator on many books including the In the Wild? camouflage books (Where in the Wild?, Where Else in the Wild? and What In the Wild?). Dwight put a Jack O’Lantern out on his porch in Maine one Halloween eve and left it there. After it started to slump a little, and then a lot, and it got covered with fuzzy organisms, his granddaughter discovered at it and started to cry. “What happened to my pumpkin?” she demanded. “I want my pumpkin back?” Dwight realized he had not just a teachable moment but a book about decomposition in the making. So he took a lot of photos — capturing not just the revolting stuff, but also the furry and feathery creatures and the mollusks and arthropods that visit the pumpkin and aid in its decay. And he asked if I wanted to write it. How could I decline such a rotten opportunity?

What genre does your book fall under?

Photographic science picture book. Not sure if that’s an official genre, but you get the idea.

What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

Movie rendition? You’ve got to be kidding. Somebody is going to play a slime mold? And a sow bug? Well, if you insist I’ll pick one to play Jack. It’s another Jack. Jack Nicholson. His crusty personality would be perfect for the part. All the critters and molds will just have to play themselves. Jack will be right at home with them.

Who is publishing your book?

This book is on the very first list of a new publisher, Creston Books, owned and managed by author/illustrator/now publisher extraordinaire, Marissa Moss. She started a new publishing company to produce new-fashioned picture books the old-fashioned way. Now, most major publishers are motivated not by the quality of a book but by the quantity of dollars it can earn, which rules out a wide range of wonderful work that would appeal to many eager eyes and minds. “The golden age of picture books, when fine books were edited and published despite not being blockbusters, does not have to be over,”proclaims the Creston Books website.

How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

I don’t think of it as a first draft, a second draft, etc. I did it that way in the typewriter days, but now I revise constantly as my research uncovers new things I want to put in the book. However, this book did have two lives. I spent about a year researching and writing it for Tricycle press, a division of Ten Speed Press, and it was almost ready to go to the printer when the new parent company, Random House, announced it was scuttling Tricycle. So the manuscript sat gathering mold for a couple of years while I sought a new publisher. When Marissa told me about Creston and signed me up for publication this year, I worked on the book for a few more months.

What other books would you compare this book to within its genre?

There are a few fine picture books on decomposition including Rotters! by John Townsend, Lots of Rot by Vicki Cobb and The MagicSchool Bus Meets the Rot Squad by Joanna Cole. Very few are illustrated with photographs and none are about pumpkins even though, as it turns out, pumpkins are great rotters! And of course tying the book to a kid-friendly holiday is an added plus.

Who or what inspired you to write this book?

I got the idea from Dwight, as I said above, and I loved the idea of getting into something that many people say, “Ewwww! Grosssss!” So I could say I was inspired by the fascination and beauty of decomposing organisms and the opportunity to produce a photography book about them. Scientists are usually articulate and passionate about their own area of study, and mycologists (who study fungi) are no exception. While most folks regard molds and other rotters with disgust, the many mycologists I spoke to while researching the book passed on their passion to me.

What else about the book might pique the reader’s interest?

I find the ecological lessons fascinating. Organisms of all size (including the weirdest living things I know, slime molds) visit pumpkins and contribute in one way or another to their demise, and their effects interact with each other. For example, Penicillium (yes, that one — the superstar mold responsible for the famous drug that has saved so many human lives) produces its antibiotic to keep competing bacteria away. You can actually see bare spots on the surface of the pumpkin where a growth of Penicillium’s exudates have dripped. I think that’s way cool! And then there’s the feel-good lesson about the next generation’s pumpkin plant coming up the next spring from a seed left behind inside the pumpkin, now fertilized by the nutrient-rich goo that last year’s Jack has become.

January 26, 2013

Googol On!

I had just given an evening program for families at a school in Berkeley when a parent named Steven Birenbaum came up to tell me something remarkable. During the presentation I had introduced my book G Is for Googol: A Math Alphabet Book by projecting this inequality on the screen. (The slashed equal sign means “does not equal.”)

No one who has tapped a computer keyboard in the past ten years needs an explanation of the word on the right. The less-known word on the left is the name for the number one followed by one hundred zeros and it appears in the title of my book.Googol, the number, is of enduring interest to myself, to many children and adults who love thinking about big numbers, and to Steven Birenbaum. He is the great-great nephew of Edward Kassner, the mathematician in the story I had told about how this un-numberlike name had been invented:

“A mathematician wrote a one with a hundred zeros after it and showed it to his nine-year old nephew. ‘What do you think we should call this number?’ he said. The nephew thought a minute and said, ‘Googol!” I have no idea why the mathematician asked the question or why the boy answered the way he did, but his name stuck and ever since then we’ve called this giant number ‘googol.’”

After speaking with Mr. Birenbaum I now know why the storied mathematician was seeking a fanciful name for this enormous number and I have a pretty good idea of why the winning name was “googol.”

The mathematician was Edward Kasner, who taught at Columbia University for 39 years during the first half of the 20th Century. He was looking for a striking way to make a point about all whole numbers, no matter how large, because he had been irked by the way people (even scientists) used the words “infinite” and “infinitely” as synonyms for “enormous” or “numerous.” In a published lecture, Kasner observed ruefully that people commonly said things like, “It is so large that it is infinite.”

Kasner wanted the world to know that no matter how large something may be, “large” cannot mean infinite!

I am reminded of my sixth grade teacher who said, “Tell me any number and I’ll tell you one bigger.” Whatever number we proffered, he just appended “and one” to it, and he had a bigger number. If you thought the biggest number was “gazillion,” he would ask, “What about gazillion and one?” His point was that there is no such thing as the biggest number. Infinity, on the other hand, is not countable and is not a number. As I sometimes tell upper elementary kids in presentations, “Infinity is not a number but numbers are infinite.”

Back to Kasner. He wanted an easily-remembered monicker for a gigantic number so he could talk about it. He presented the challenge of naming it to his two young nephews Milton and Edwin Sirotta during a walk in Palisades Park, near Manhattan. As the story goes, Milton blurted out “Googol!”

A few years ago, when the internet company Google* was holding its initial public stock offering, the Wall Street Journalran a profile of Kasner by Carl Bialik. (You can read it here.) From the article I learned that some of Kasner’s living relatives believe that the two brothers should be given equal credit for a collaborative effort. (A number that big can stand to have two namers, I guess.) Denise Sirotta, daughter of Edwin, not only makes that case based on family lore, but shesheds light on the question of why “googol”? She says her father told her that Kasner wanted “a word with a sound that had a lot of O’s in it.”

Think about it: “googol.” Not only is the sound rich with O’s but so is the look. Notice those letters. Every one of them except the “l” has an “O” in it (yep, even the “g’s”).

So, thanks to the serendipity of my encounter with Steven Birenbaum, both of my public musings earlier in the evening—why did Kasner want a name for this basically useless number and why did the boy(s) say “googol”?— have been answered.

I have to mention one other thing about Kasner, which I learned from the Wall Street Journal article. The mathematician never had children but he was adored by his nieces and nephews. It is said that on a walk with some of them in the Palisades, the party encountered tea kettles and matches that he had hidden under rocks and teabags that he had hung from trees. They stopped to make tea!

No wonder Kasner was described by Time magazine in 1940 as a mathematician who was “distinguished but whimsical.” What a noble combination!

Googol on!

* Google, the company, is said to have derived its name from “googol,” as an implicit reference to the enormous amount of information on the internet. Whether of not the founders changed the spelling deliberately or mistakenly is an open question. But there is no question that the company’s headquarter complex is named for another number that the Sirotta boy or boys named: The Googleplex. A googolplex (note the spelling) is a one followed by a googol zeros. Try writing them all.

September 24, 2012

The Problem with Word Problems

Greetings from Lima, Peru. I’m here for a tour of three international schools (in Caracas, Lima and Santa Cruz, Bolivia). I had an experience in Caracas that I’ve had many times before in the USA and it has me thinking… and now blogging.

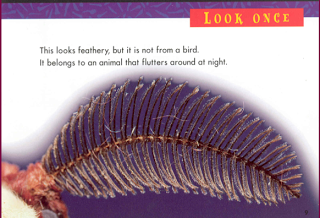

On a screen, I showed a group of 2nd graders a page from one of my “Look Once, Look Again” books. The idea of that series is that you see a close-up photo of part of an animal (or plant) and text that hints about its identity. Then you turn the page to see the whole organism, and learn a bit about it.

On a screen, I showed a group of 2nd graders a page from one of my “Look Once, Look Again” books. The idea of that series is that you see a close-up photo of part of an animal (or plant) and text that hints about its identity. Then you turn the page to see the whole organism, and learn a bit about it.

Here’s the text: “This looks feathery but it is not from a bird. It belongs to an animal that flutters around at night.”

Many of the second graders at Escuela Campo Alegre in Caracas said the same exact thing that second (and other) graders at schools all over the United States have said: “Owl.” If I ask what kind of animal an owl is (and I always do), the same child will quickly answer, “A bird.” And if I ask, “What did the book say about it being from a bird,” he or she will recall, “It is not from a bird.”

Yet, they almost always say that this is from an “owl.” The “flutters around at night” seems to overpower the “is not from a bird.”

Why? I have no answer.

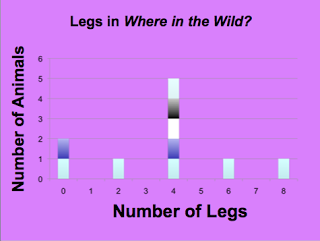

Here’s another one, also shown to second graders. It’s a graph showing how many legs are on the various animals in my book Where In the Wild? Camouflage Creatures Concealed…and Revealed. I’m happy to say that, by and large, with a little guidance second graders everywhere can understand the basics of the graph. When I say, “What number of legs appears most often,” they usually answer, “Four.” My next question, “How many animals in the book have four legs?” usually generates the correct answer, “Five.” Good, they do seem to get it that you look along the “X” (horizontal) axis to see how many legs and you look on the “Y” (vertical) axis to see how many animals have that number of legs. Correct answers to other questions confirm that they get it.

Here’s another one, also shown to second graders. It’s a graph showing how many legs are on the various animals in my book Where In the Wild? Camouflage Creatures Concealed…and Revealed. I’m happy to say that, by and large, with a little guidance second graders everywhere can understand the basics of the graph. When I say, “What number of legs appears most often,” they usually answer, “Four.” My next question, “How many animals in the book have four legs?” usually generates the correct answer, “Five.” Good, they do seem to get it that you look along the “X” (horizontal) axis to see how many legs and you look on the “Y” (vertical) axis to see how many animals have that number of legs. Correct answers to other questions confirm that they get it.

Then comes the stumper. I designed it to be a little harder, but not that hard. “Are there any animals in the book with an odd number of legs?” They almost always say, “Yes.” (I have confirmed that in most cases, they do know the odd numbers from the even numbers.) When I ask a follow-up question, like “How many?” or “What odd number of legs does an animal in the book have?” there is no clear answer. They don’t have one, yet they were quick to say “Yes.”

Why? I have no answer.

I do have a hunch, though. My hunch is that they fail to understand the question, not the graph. I am reminded of a professional book by Char Forsten called The Problem With Word Problems Is the Words. Great title. And so true. Students need to understand the words, deeply and fully, before they can answer word problems.

And how do students get fluent in understanding words? The answer is no secret and no surprise: by reading. And especially by reading non-fiction. Complex non-fiction. The Common Core State Standards place a great emphasis on reading complex non-fiction and informational texts, reading them deeply and integrating related works on the same subject. It is estimated (though no hard data exists) that in elementary schools, children read 80% fiction and 20% non-fiction. Perhaps moving that ratio closer to 50:50, as the CCSS suggests, would help students figure out that the thing that looks feathery but is not from a bird cannot be from an owl but is, in fact, an antenna of a moth … or that no animal inWhere in the Wild? (or anywhere, as far as I know) has an odd number of legs.

June 27, 2012

The Little Darlings

I was going to call this post “Kill the Little Darlings.” It sounded oh so ghastly that I decided to drop the first part, but killing them is what this is about. Don’t worry, I’m talking words, not people.

Years ago, someone told me that Somerset Maugham, the British novelist and playwright, had said, by way of advice to writers, “Murder the Little Darlings.” I’ve referred to this quote many times but always with the caveat that I have not able to confirm the source or the exact wording. The only Maughamism I could find on writing, courtesy of www.brainyquote.com, is this: “Habits in writing as in life are only useful if they are broken as soon as they cease to be advantageous.” Well, I guess it’s true but it doesn’t have quite the shock value of the non-quote I’ve been attributing to him all these years.

Shock value is certainly the provenance of a contemporary American novelst, Stephen King who, I’ve just discovered, has admonished authors to “kill the little darlings.” Who better than Mr. King for that? Some say that William Faulkner beat King to it by a few decades, that the iconic Southern writer has been quoted similarly. Who knows. What’s more important than attribution right now is the murderous concept at hand.

The “little darlings” are those favored words, turns of phrase, even entire paragraphs or chapters that do not earn their keep, no matter how they may please the ear or eye. They might do wonders for a 64-page book of 4,000 words, but not for a 32-page 600-word picture book. They might stimulate the reader’s intellect, which is fine but could be a problem if the intent at that moment is to make her laugh (or cry) — or vice versa. They might sound good but just not quite fit or they might needlessly extend the text into the realm of verbosity when nothing else can be cut. There are myriad justifications for killing the little darlings, but kill you must.

This all came to mind recently in the editing of my book about what happens to the pumpkin after Halloween. My editor and publisher (and friend), Marissa Moss, committed homicide on my title. I had called it I Rot: The Fall and Rise of a Halloween Pumpkin. All authors realize that titles are tentative but I rather liked it. I thought the “I Rot” part (since the book is written the first person from the voices of the characters in the drama, starring the pumpkin itself) was catchy. And the “Fall and Rise” bit seemed a nice twist on the usual phrase by reversing it. No, I wasn’t in love with it, but I was pretty satisfied. And then Marissa came along.

“I think we should call it Rotten Pumpkin,” she declared.

“Rotten Pumpkin? That’s all?” I said. “Do you mean we should just refer to it as the “rotten pumpkin” book?” I’d been doing that all along.

“No, the title. Rotten Pumpkin. That says it all, don’t you think?”

Well, I hadn’t… but maybe I could. Maybe I would. MaybeRotten Pumpkin would jump off the shelf and grab the browser and say “READ ME!” in a way that my ten-word title would not. Maybe it would make a potential reader into a reader who wants to know why in the world a book would be called Rotten Pumpkin. “What kind of rotten book is that? I have to find out!” By contrast, my ten-word title probably doesn’t have much jumping power. Maybe it just says, “Here’s something for you to think about if you happen to be in the mood to think about it. Which might be tomorrow. Or the next day. Or maybe in time to write that report.”

So I’ve been killing little darlings for the past few days. It’s a hard job but someone’s got to do it. And once I get through the mourning, it feels really good.

Happy summer everyone. My all your edits be satisfying, whether or not they are murderous.

May 27, 2012

Saguaro by the Numbers. Maybe

I’m going to install a little window in my mind so you can see how it works. At least how it is working at this moment. It may not work in quite the same way at any future time. Here’s my promise: other than having decided on the overall idea, I have not planned the specifics of what I’m about to write. Instead, I will record my thought processes (if there are any) as they occur, to see if something interesting, useful or otherwise worthwhile happens. And if not, you’ll get to see that, too. Ready?

I’m going to install a little window in my mind so you can see how it works. At least how it is working at this moment. It may not work in quite the same way at any future time. Here’s my promise: other than having decided on the overall idea, I have not planned the specifics of what I’m about to write. Instead, I will record my thought processes (if there are any) as they occur, to see if something interesting, useful or otherwise worthwhile happens. And if not, you’ll get to see that, too. Ready?

Here’s the context. It happened earlier this month. I was in Phoenix for school visits, and I had a free afternoon so I went to the Desert Botanical Garden. Great place! I was looking at an exhibit on saguaro cacti, the Sonoran Desert’s quintessential plant. A mental image of this charismatic cactus with upcurving arms may be the first association many people have with the word “desert,” although saguaros grow only in this relatively small desert of southern Arizona, northwestern Mexico and a sliver of southeastern California. I knew these are very cool plants from a very hot place, but of course I was eager to know more.

So I read the interpretive signs and I was bowled over… with numbers. That is to say, numerical facts about saguaros. Being a numbers guy and a math author, the hairs on the back of my neck stuck up like cactus thorns. Here are a few of those numbers:

— a single saguaro plant releases up to 40 million seeds in its lifetime

— a single saguaro plant releases up to 40 million seeds in its lifetime

— saguraros grow incredibly slowly: about ½ inch in the first year and one foot in the first 15 years. Then they start cruising: in 40 or 50 years, they may reach ten feet and it is not until they are 50-100 years old that they begin to sprout arm buds. Some live up to 300. Their maximum height is 40-60 feet. When a cactus poacher (oh yes, they do exist) digs up a six-foot saguaro to plant in front of his house, a replacement in the wild will take about 30 years reach the size of the poached plant (which will probably die).

— one mature saguaro can store 1,500 gallons of water (that’s 6 tons) in its spongy pulp — enough to last several months. It can lose 2/3 of its stored water and survive.

There were many other numbers but that’s enough for now.

So here’s what happened. I thought to myself, “Hey, how about a book about saguaros and their numbers?” Saguro Numbers or Saguaros by the Numbers or Number the Saguaros or something like that. Or maybe not like that. But let’s not get hung up on the title. The thought did not evade me that if I could pull it off, sequel possibilities would be countless: Elephants by the Numbers, Great White Sharks, Dinosaurs … even Oceans, Earth, The Solar System, etc.

So what about it? Having an idea for a book (or a series) is the easy part. Figuring out a way to execute the idea is another matter. It’s kind of like the business plan for a book. Without it, all you’ve got is something to talk about at cocktail parties. With it, you’re in business. Maybe. So what should I do with this inchoate idea of saguaros and numbers? Let’s see…

First thought out of the gate: like Harper’s Index. You know, “Rank of Portland, Oregon, of all cities in per capita consumption of Grape-Nuts: 1” or “Number of incidents worldwide last Christmas (2005) of ‘Santanarchy,’ which involves roving mobs of unruly Santas: 29”

So, instead we could have, “Number of seeds a saguaro cactus produces in its lifetime: 40,000,000.”

OK. Possible. But a bit dry, and it seems a bit too much like, well, Harper’s Index. A derivative work. Heaven forbid. And it might get tedious. But with additional text to explain and fill out the saguaro’s story, it could work.

So, maybe this instead: I’ll build the book around a number line. One gargantuan number line could extend across all the pages. Number lines are an important way for children to understand number concepts, and along the number line I could mark numbers of importance in understanding saguaros. At the number 10, there could be an arrow or an indicator that you can follow to an explanation that in 10 years, if all goes well, the saguaro will reach a height of one foot. (I suppose I could just as well put the marker at the number 1 and say that one foot is the height of the saguaro after ten years.) At 1,500, you’d have the number of gallons of water a plant can store. (Or it could be 6 for 6 tons.) And at 40,000,000 the number of seeds produced in a lifetime. Of course there would be many opportunities to add supplemental information to fill out the picture. (Let me not discuss right now the question of whether to use metric units of American units or both. We’ll save that for another day. We’re just brainstormin’ here.)

OK, but a few problems with my number line idea come to mind. For one, how can I set up a number line on a scale that shows 1 and 6 as well as 1,500 and 40,000,000 and plenty of points in between? I guess there are ways. I could leave out sections (showing jagged lines to indicate discontinuities). Yeah, that’s possible. Or how about this: multiple number lines on different scales. One for growth. That would work. Another for production of things like seeds. Forty million. But what else could go on that number line? Maybe nothing else. Does it make sense to create a number line with only one point on it? Maybe not.

But wait a minute, suppose I created a bunch of number lines, on different scales, and I showed not only the saguaro-relevant numbers (example: 1,500 gallons of water stored) but other values that could put it into perspective, such as how much water is found in a large watermelon, in the body of a human, in an Olympic-size swimming pool.

That could work. But let’s think about it. Do I really want a book of number lines to tell the story of a saguaro cactus? Maybe. Maybe not.

How about a book of math problems related to saguaros? “It has rained for 30 hours in the Sonoran Desert. A 40-foot saguaro’s roots spread 40 feet in all directions, and in the area above the roots, 100 gallons of water fall each hour. The saguaro can absorb half of that water. How much water can this giant cactus absorbed?” (Do you need the Teachers Edition? The answer is 1,500 gallons.) Then some narrative can explain that these plants really do this, how amazing they are, etc., etc. Nah, too much like a math textbook.

OK, how about a book with chapters that are numbered in an odd way. Instead of Chapters 1, 2, 3, etc., we can number the chapters according to the number being discussed. So it could start with Chapter 1 in which we feature the number 1. All the things about saguaros that come in ones. Or just one thing: in one year it grows half an inch. But then we might skip to chapter 10. That’s how many years it takes for the saguaro to grow to a height of one foot. And I would talk about water absorption in Chapter 1,500. Chapter 40,000,000 is for the seeds. (Hey, I could start with Chapter ½ because it grows half an inch in the first year.)

Hmmm. Not bad. Original (I think). Maybe I could pull it off. Maybe not. That’s all I’m coming up with right now: lots of maybes and maybe nots.

And maybe, since the great horned owl of my bird clock just hooted (as the clock’s little hand reached the number 12), I’ll sleep on it. Tomorrow is another day for a few more maybes. And then maybe I’ll start writing to see which of these maybes I like best. Or maybe I’ll think of a better one. (In the meantime, feel free to vote for your favorite or suggest your own maybe.)

March 27, 2012

New Hope for Old-Fashion Books

Exactly one month ago I received an email from my friend and colleague (and fellow East Bay resident), Marissa Moss. It began almost apologetically:

Exactly one month ago I received an email from my friend and colleague (and fellow East Bay resident), Marissa Moss. It began almost apologetically:

“I know this probably comes out of thin air, but I’ve heard from so many talented writers and illustrators that they have problems getting contracts now from the major NY publishers who only want books with mass market appeal …”

Sounds like an understatement in these days of publishing uncertainty (aka “crisis”) but I was hooked. Marissa is a versatile writer and illustrator of both fiction and non-fiction, full of ambition and creativity, who has enjoyed considerable success. What was she up to?

“The golden age of picture books, when fine books were edited and published despite not being blockbusters, doesn’t have to be over,” she wrote.

Instead of lamenting the demise of publishing as we knew it, Marissa announced that she is going to turn the dearth of publishers seeking to put out beautiful books into an opportunity. She has found financial backers who share her values, and she is starting a new publishing house intended to turn back the clock by producing “quality books the old-fashioned way.” Golden Gate Books will make its mark with children’s fiction and non-fiction that book-lovers will want to hold, admire and read repeatedly.

This is actually the second recent blast of publishing news to gust my way. Our own INK is becoming a publisher of e-books, starting with the out-of-print titles of our members. I have four titles ready to go, as soon as I do the necessary scans and we work out the contract details to sell our books on the iTunes store and perhaps other e-marketplaces. This is exciting news not only because it gives authors a chance to immortalize our books and make them available at very low cost to interested readers, however many or few they may be. I am also thrilled because it is the impetus I need to enter this new world of publishing and experiment with its myriad possibilities.

While INK, for starters at least, will be e-publishing out-of-print titles (which, in the current reality of publishing, does notmean out-of-life or out-of-value titles), Golden Gate Books, despite valuing the paper-in-hand approach to reading, may also enter the e-realm by releasing all of its titles as e-books within months of their print debut.

Whether or not its titles have an e-life, Marissa is embracing web-based promotion and even fund-raising. Right now she has enough money committed to plan eight books during GGB’s first year, but if she can raise an additional $50,000 she will go for twelve with a larger marketing bang for all of them. She is using www.kickstarter.com, a fund-raising website that follows the NPR model to seek pledges from donors who receive premiums at different levels depending on how much they give. No pledges are actually collected unless the goal is achieved. In this case, it’s $50,000 in pledges by April 19, 2012. Check it out and please feel free to choose your premium:

http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/404352146/golden-gate-books-a-childrens-book-revival

Here is one piece of the pitch, where Marissa (writing from the future) summarizes the mind-set of today’s typical publishers:

“Instead of taking risks on new voices or subjects, they focused on what had already sold well – one Harry Potter book led to a slew of imitators. One Twilight book created a wake of supernatural novels. Instead of looking for the great books of the future, they looked for books that were like great books of the past.”

I would make one edit: change “great books of the past” to “successful books of the past.” I recall my appearance at the Texas Library Association conference in April, 2000, after my book If You Hopped Like a Frog had just come out with Scholastic. It put forth a new, enjoyable approach to proportional thinking in which human abilities were compared, proportionally, to those of animals. Proportion is an important concept in algebraic thinking, taught in various ways (most of them confusing, boring or both) throughout the upper elementary and middle school grades. The Scholastic team was out in force at TLA giving away, waving and wearing a plethora of promotional items in various shapes, sizes and levels of extravagance. Did even one of these marketing pieces reference my book or that of any other up-and-coming author? Not on your life! Every single one was about Harry Potter, whose third (or was it fourth?) installment was hitting the American market. Harry really needed the help, didn’t he?

I recall my appearance at the Texas Library Association conference in April, 2000, after my book If You Hopped Like a Frog had just come out with Scholastic. It put forth a new, enjoyable approach to proportional thinking in which human abilities were compared, proportionally, to those of animals. Proportion is an important concept in algebraic thinking, taught in various ways (most of them confusing, boring or both) throughout the upper elementary and middle school grades. The Scholastic team was out in force at TLA giving away, waving and wearing a plethora of promotional items in various shapes, sizes and levels of extravagance. Did even one of these marketing pieces reference my book or that of any other up-and-coming author? Not on your life! Every single one was about Harry Potter, whose third (or was it fourth?) installment was hitting the American market. Harry really needed the help, didn’t he?

On May 25, 2009, I wrote a blog post here called “Paen to a Publisher,” in which I paid tribute to one of my publishers, Tricycle Press, which (along with its parent company, Ten Speed Press) had just been bought by Random House. I wondered aloud whether the many uncommon practices that had made Tricycle my favorite, if smallest, publisher would be retained once it became part of the world’s largest media conglomerate. (For example, Tricycle ignored a near-universal convention in publishing by allowing an author to have a voice in selecting the illustrator for his or her book. Tricycle even allowed authors and illustrators to influence editing decisions and sometimes gave them the final say. Can you believe?)

I have never written a postscript to that discussion and here it is: in January, 2011, Random House announced that it was scuttling Tricycle Press. My favorite publisher is history. One of the many pieces of flotsam left adrift by the maelstrom of that decision was my manuscript I Rot: The Fall and Rise of a Halloween Pumpkin, which I described in my May 24, 2010, INK blog post called “Researching With Researchers.” Since then, I have been seeking a new publisher for my rotten manuscript (and the revolting photos by Dwight Kuhn that accompany it).

I have never written a postscript to that discussion and here it is: in January, 2011, Random House announced that it was scuttling Tricycle Press. My favorite publisher is history. One of the many pieces of flotsam left adrift by the maelstrom of that decision was my manuscript I Rot: The Fall and Rise of a Halloween Pumpkin, which I described in my May 24, 2010, INK blog post called “Researching With Researchers.” Since then, I have been seeking a new publisher for my rotten manuscript (and the revolting photos by Dwight Kuhn that accompany it).

Along comes Golden Gate Book, seeking authors and illustrators with worthy manuscripts in search of a publisher, authors who have established relationships with booksellers and who effectively promote their own books through school visits and other appearances. . . Along comes Golden Gate Books, promising to give the creators of books an unusual amount of control over their projects. . . Along comes Golden Gate Books, “a company that cares about the magic that happens when a parent reads a picture book to a child.”

And I am now delighted to announce that the magic of a decomposing pumpkin (and it is magical in its own transformative, regenerative way) will be featured on Golden Gate Books’ first list in the Fall of 2013.

at 6:00 AM

January 26, 2012

Got a Second

You’d better use your extra second while you can, because it might just disappear.

You’d better use your extra second while you can, because it might just disappear.

I’m talking about the leap second. Leap seconds are a little like leap years but shorter. A lot shorter. (Actually, a “leap year” really should be called a “leap day,” IMHO.) And they are an endangered species.

It’ll take me just a few leap seconds to explain. Once upon a time, time itself was measured by the rotation of the earth. There are 24 hours in a complete rotation (aka one day), 60 minutes in an hour and 60 seconds in a minute, so a little arithmetic tells you there are 24 X 60 X 60 = 86,400 seconds in a day. You could set your clock by it. Actually, your clock was made to show it. This was all fine and well and if anyone was late for church on his wedding day, he really couldn’t blame the clock. But scientists weren’t satisfied because it was hard to be sure of the precise duration of a second, so in 1967 they put official timekeeping in the hands of the hand-less atomic clock. An atomic clock relies on the oscillation frequency of a certain type of atom known as cesium-133. Atomic clocks may be cumbersome on your nightstand, but they sure are accurate. After 100 million years, give or take, an atomic clock will be off by one second. In the techno-world beginning to emerge in the 1960’s, precision in timekeeping was of great importance. Imagine how grumpy networked computers might get if different parts of the network were off by a second here, a second there. Atomic clocks solved that problem, and traditionalists couldn’t complain because the atomic clocks were pegged to the earth’s rotation. A“day” on an atomic clock and a “day” defined as a single rotation of the earth were the same. All was well in timekeeping.

Eventually, something was found to be rotten in Denmark and everywhere else on the planet: the Earth does not run like clockwork. Its rotation is gradually slowing down. Rather than losing a second in 100 million years, it loses a second every few years. In an average human lifetime, the earth might lose 15 or 20 seconds. (Think of what that poor average human could have accomplished with an extra time.) So to keep the world’s atomic clocks in sync with the actual earth, the leap second was born. Because the rate of slow-down is not perfectly predictable, the insertion of a leap second is not on a regular schedule like leap years, which synchronize our calendar’s annual cycle with the earth’s revolution around the Sun by inserting February 29th every four years (with some carefully worked out exceptions). The International Telecommunications Union, an agency of the United Nations, announces leap seconds on an as-needed basis. The last one was in 2008 and there will be another on the night of June 30th of this year. The extra second will be added before July 1st rolls around. Start planning this gift of time before the summer rush.

But now there’s talk of the leap second’s demise. The extra second on June 30, 2012, is secure, but the ITU will meet in Geneva next month to decide whether to keep or kill future leap seconds. The United States wants to do away with it but the leap second has some heavyweight defenders including Canada, Britain, China and a few other countries that consider extremely punctuality in their national interest. I won’t go into the arguments pro and con, but there was a good article about it in the New York Times last week (Jan 18, 2012). I must say I am leaning toward the side of leap second defenders because leap seconds tie the time of day to the rising and setting of the sun (quaint as that notion may be). If we abandon the leap second and just let those atomic clocks run nilly-willy while the hapless earth slows down, we will get to a point when sunrise would come at the strike of noon. (It’s impossible to predict exactly when this disruption to your lunch plans will occur because, according to the Times, it will be “not more than 100,000 years from now” so please be forewarned.)

So what, if anything, does this have to do with children’s books? For one thing, I am not aware of any book on the leap second or even a book on time that mentions it. (OK, commenters — tell me about all the books I missed.) More importantly, I have confession: In all of my non-fiction science and math books I have simplified some concepts to make them age-appropriate for what I see as the book’s readership. Or I have left them out altogether if I thought an adequate explanation would be too long, too difficult or too uninteresting. This is a judgment call, of course.

Sometimes I have regretted my judgment. There are millions of things you can measure, and time is one of them but inMillions to Measure I did not include the measurement of time. This isprobably because I had an axe to grind about the archaic system of measurement still used in the United States. I wanted to concentrate on showing how the metric system works and how much more sensible it is than our uncoordinated system of feet, pounds and fluid ounces. (In fairness, I should disclose that we aren’t the only country using this system. Last I checked, it was also the norm in Liberia and Myanmar.) So in a book comparing metric (technically known as Système International, or SI) units with “customary” (American) units, there was no need to talk about time because — guess what — time is measured the same way in all nations. Amazing but true: everyone uses the same years, days, hours, minutes and seconds! But now that there’s a brouhaha brewing over the leap second, I wish my book had prepared users to understand it. I wish I had included cesium clocks because they are kinda cool (and wouldn’t kids think so, too?).

Sometimes I have regretted my judgment. There are millions of things you can measure, and time is one of them but inMillions to Measure I did not include the measurement of time. This isprobably because I had an axe to grind about the archaic system of measurement still used in the United States. I wanted to concentrate on showing how the metric system works and how much more sensible it is than our uncoordinated system of feet, pounds and fluid ounces. (In fairness, I should disclose that we aren’t the only country using this system. Last I checked, it was also the norm in Liberia and Myanmar.) So in a book comparing metric (technically known as Système International, or SI) units with “customary” (American) units, there was no need to talk about time because — guess what — time is measured the same way in all nations. Amazing but true: everyone uses the same years, days, hours, minutes and seconds! But now that there’s a brouhaha brewing over the leap second, I wish my book had prepared users to understand it. I wish I had included cesium clocks because they are kinda cool (and wouldn’t kids think so, too?).

And one more mea culpa: I even wish I had come completely clean on the mighty meter itself. I stuck with the original definition — one ten millionth the distance from the equator to the North Pole. Eventually, the meter was standardized to a very special piece of metal kept at a constant temperature in Paris, available to be measured any time you needed to check it against your own meter stick (if you had train fare and the right ID). But for much the same reason that time is now measured by atomic oscillations, the world’s leading unit of length is now tied to a measurement that labs around the world can perform if they want to: the wavelength of emissions from atoms of krypton-86. (Common sense tells us that krypton must be related to Superman’s kryptonite, and if it’s good for Superman, it’s got to be good for you and me, dontchathink?)

I imagine all authors of non-fiction for young readers must decide whether content is “too hard” or “not too hard”? It might be an interesting panel discussion subject: how do you decide? Do you just have a hunch or do you use guidelines of some kind? Is there such a thing as “too hard” at all? Can any subject be made accessible in the hands of a master?

While you’re pondering that, I’m going to think about what I’ll do with my leap second on June 30th because it may be my last.

November 28, 2011

Numbers In the News

A few years ago I was greeted at a school by more than the usual “Welcome” banner. A bulletin board shouted, “Mr. Schwartz, We love BIG numbers, too!” Some of the numbers in articles from newspapers, magazines and websites had been highlighted, and children had written about the significance of the numbers in the context of the news items.

I appreciate it when a teacher guides students to the confluence of math and social studies where numbers and current events meet — which they do every day. Numbers are always in the news.

I recently explored some of the many youtube videos and web pages devoted to “explaining” big numbers, especially when they have $ signs in front of them, and I found that most have a covert (or overt) right wing anti-tax message. Someone should catalog the comparatively few whose political undercurrents run the opposite way (illustrating $s for the military budget in comparison with, say, education or hunger programs). This could be the subject of a future post, but right now I am going to examine three newsworthy numbers that have invited my musings.

“The 99%” Three months ago, no one would have understood the numerical reference but now it needs no introduction. On October 10 in the Economix column of the New York Times, Catherine Rampell provided some statistical analysis. Here’s a sampling:

If your household were right at the cutoff for the 99thpercentile in income, your family’s annual income would be $506,533. You and your fellow Americans of equal or greater income in the top 1% would, in fact, be earning 20%, or one-fifth, of all American income. But what you earn alone is not what determines your wealth. Your wealth is what you’ve accumulated. The top 1% holds about one-third of America’s riches — an average of just over $19 million. Nice going! Tough luck for the rest of us.

To me the most interesting thing about wealth distribution is how unequally divided it is even within that top 1%. The mathematically minded might say that the income curve rises steeply above the 99% level. So, while you (at the 99thpercentile, remember?) are earning a mere $506,533, your neighbor (in the mansion down the street) is at the 99.9thpercentile. He or she is earning $2,075,574. You’re both in the top one-hundredth of all earners but your neighbor is also in the top one-thousandth. Nobel-winning economist Paul Krugman calls this group the “super elite,” a term we should throw in the face of Republicans who use the word “elite” to besmirch the character of anyone with a Master’s degree or a taste for latte. These “elite”-bashers who control of our political agenda have devoted themselves to cutting the taxes of the super elites with the same blade that, on the back stroke, is meant to slash Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. Hence, Krugman advises the Occupy movement to expand (by an important 0.9%) the scope of its rallying cry to “We are the 99.9%!”

7,000,000,000 (aka 7 Billion) I’m looking at a scan I made of a newspaper article from October about the earth’s population reaching a milestone population — a billion multiple. But it’s not seven billion. It’s just six billion. I scanned it in October, 1999. At that time, the 6 billionth human was getting ready to be born. Last month — October, 2011 — the media were again abuzz about the earth’s population reaching a billion multiple: 7 billion. That means our planet added one billion people in a mere dozen years. Demographers have been stunned. But our growth rate is slowing. By 2050, we’re predicted to add only another 2.3 billion — an amount that nearly matches the number of people who inhabited the planet in 1950.

Explainers from Ann Landers to President Reagan to David Schwartz have tried to put big numbers into micro-narratives for public consumption. “If you wanted to count from one to one billion,” I wrote in my first book, How Much Is a Million?, “it would take you about 95 years.” Hence, it would take almost 700 years to count every person on earth today. Of course you’d never be able to keep up with the population as it grows.

As with so many genres of digestible information, the current catchphrase is “There’s an app for that.” Apps are the snack food of the information age, and the current population of the earth is no exception. This app, from National Geographic, is called “7 Billion.” Free from the Apple App Store, it’s full of photos, videos, charts and infographics. Here are a few gleaned factoids:

— Every second five people are born and two die. (Can you see the problem?)

— In 1975 there were three cities with populations over 10 million; now there are 21.

— There’s plenty of space for 7 billion people on earth. We could all fit shoulder to shoulder in Los Angeles. (If you thought rush hour on the Harbor Freeway could get no worse, think again!)

The app also says it would take you 200 years to count to 7 billion. I disagree. That would be possible only if you averaged about one number per second. Try saying a few of the big ones and you’ll see it’s impossible to whiz through them that fast.

17.2 million You may have missed this stat, which I share in the wake of Thanksgiving weekend. It’s the number of households in the US who are “food insecure,” the euphemism du jour for “hungry.” Representing 14.5% of households (one in seven), it’s the lowest level of food security in our nation’s history and it encompasses 48.8 million people.

The following figures are reported by Pat Garofalo, Economic Policy Editor for ThinkProgress.org. Food insecurity has grown by 30% during the Great Recession. Almost 4 million of food insecure households have children. Fifty-five percent of the households participate in one or more of the three largest Federal food and nutrition programs — SNAP (formerly Food Stamps), WIC and the School Lunch Program — yet 10.5 million eligible children do not participate. Last year, nearly half of the households seeking emergency food assistance reported that they had to choose between paying for heating fuel or food.

These are not cheerful statistics to contemplate as we conclude the Thanksgiving weekend, but ignoring them would be about as appropriate as further tax cuts for billionaires.

October 31, 2011

Real World, Unreal School

When I walked into Masha Albrecht's geometry class at Berkeley High School last week, her students were holding hands. It wasn't budding romance. It was math. Before I explain, I have to tell you about Masha.

I met her when I was a senior at Cornell in the 1970s. I decided to do an independent study that involved working with students in an elementary school classroom and she was the most eager, bright-eyed fourth grader in the class. Masha's brother Bobby was in an adjacent room and the two classes were team-taught. I hit it off with both siblings, and before the end of the semester I had been to their house several times, met their parents, and spent some enjoyable after-school hours together—doing math. The three of us had delved into Harold Jacobs's masterful Mathematics: A Human Endeavor, then in its first edition, and we tackled the mind-stretching, often funny, problem sets with gusto. "This is how math should be taught in school," exclaimed Mrs. Albrecht.

I re-met Masha Albrecht at a conference for math educators in northern California last December. We were both speakers. Good thing her name is an unusual one because I recognized it immediately on the program, and I sought her out. And just to close the triangle of delightful coincidence: Harold Jacobs was also a speaker at the conference.

So now Masha teaches math in school the way it should be taught. Her mother would be proud. In groups of three, four, five and six, her students were creating polygons on the day I visited. Their bodies were the vertices and their arms were the sides. In this kinesthetic approach, they were learning the vocabulary and some mathematical principles of polygons. "Now shake hands with a non-consecutive vertex," their teacher requested. Later she told me, "They don't get 'non-consecutive vertex' unless we do it this way. Now they'll get it and remember it."

What a teacher! Actually, I had gone to the class to see an entirely different class project she had told me about. She had decided to use hubcaps to illustrate reflexive and rotational symmetry. Here is a quick a primer on symmetry so you don't have to wait for Loreen's new book (see her post of Sept. 21st). It is my hope is that once you learn about this, walking past parked cars will never be the same.

[image error]If one half of an object mirrors its other half across an imaginary line, we say it has reflexive symmetry. Think of a human face, at least an idealized one. The imaginary line is the "line of symmetry." Whether or not an object has reflexive symmetry, it might (or might not) have rotational symmetry. Imagine rotating the object partway through a full 360-degree rotation. If you can get it to a place where it looks identical to how it looked before, in the same exact orientation, it has rotational symmetry. If you can rotate it into three positions that look identical, it has three-fold rotational symmetry. Four positions gives it four-fold rotational symmetry and so on. Clearly, human faces do not have rotational symmetry.

But start looking at hubcaps. Do you see reflexive symmetry? Sometimes, always or never? Do you see rotational symmetry? Sometimes, always or never? Do you ever see both in the same hubcap? Are there hubcaps with neither? (Disregard scratches or imperfections.) The answers may surprise you. They sure surprised me. In fact, I now think hubcaps are way cool, way beautiful and full of subtle surprises. (I don't know why it took so long for me to realize this, but— as with so many epiphanies— a teacher was the catalyst.) And here's just one of the many discoveries that I, and Masha's students, made: there are hubcaps with what I'll call "dual foldedness." This could mean a pattern that is neatly subdivided (imagine five rays emanating from a central disk, with each ray subdivided into three branches). That's interesting enough in an orderly sort of way. But imagine a cap whose central disk has fivefold rotational symmetry and whose periphery has six-fold. Now that's cool! Think about it, draw it, or go out and look for a hubcap bearing it (try a Toyota Prius — some years) and decide whether that cap as a whole has any symmetry at all.

Devoted to finding real world applications to help Berkeley High students understand mathematics, Masha had a great idea. Two, actually. One was to connect "dual-foldedness" (like the 5 vs. 6 example) to polyrhythms in music. She didn't actually end up exploring this with her students, but she did ask them to start taking photos of hubcaps and putting them into a grid she'd created at the back of the room. They would identify the photo's symmetrical properties by pasting it into the appropriate cell of the grid. Across the top, columns were labeled for foldedness— 2-fold, 3-fold, 4-fold, etc., up to 8-fold. The rows were labeled "Reflexive," "Reflexive and Rotational" and "Rotational But Not Reflexive."

After a week, the grid boasted merely one hubcap picture and Masha was ready to take it down. "The project didn't light a fire under them," she told me on the phone. Later, in an email, she wrote, "I think once they are walking down the street all thoughts of academics are far away. I myself continue to be amazed by the variety of symmetries in hubcaps."

She did invite me to see some lovely posters the same students had made to illustrate geometry in the real world — seashore organisms, springtime flowers, quilts and so forth. And indeed they were lovely posters, caringly created. But to me, the hubcap project was a little different because it required discovery in the real three-dimensional world using the students' own eyes and minds, rather than research from second-hand resources like books or the internet.

Masha didn't seem surprised at the disappointing level of participation of the hubcap project. "I will defend my students," she wrote in another email. "I think the school environment doesn't connect to their world, so by high school they have stopped bothering to believe in any connections."

Wow. What an indictment! It's not hard to see how the drill-and-kill/teach-to-the test/scripted-lesson regimen that so many schools now call education would drive out any hope of connecting math to the real world. Did Masha hit the hubcap on the head with that conjecture?

Let me propose an experiment. Teachers of intermediate grade students may be able to test Masha's statement if they can break away from the stranglehold of teaching-to-the test long enough to try this:

I believe the symmetrical properties of hubcaps are accessible to 4th or 5th graders, who have had 4-6 years less schooling than Masha's high schoolers. So how about teaching them about symmetry and trying a similar project? (You can find a short exposition on the subject in my book G Is for Googol on the page "S is for Symmetry." Masha likes the superbly untextbooky textbook Discovering Geometry by Michael Serra.) Your students could draw the hubcaps in the grid if they don't have cameras. Would a project like this light a brighter fire under 4th graders than it did under 9th and 10th graders? I'd love to know. If your students can shed any light, please let it shine in the comment section here.

In the meantime, I'm going out to photograph more hubcaps.

[image error]

October 24, 2011

Guest Blogger Marissa Moss: “Finding the Story in History”

This month I am taking a break from blogging. In my slot, I am proud to present my friend and collaborator (on G Is for Googol: A Math Alphabet Book), an esteemed author and illustrator of both fiction and non-fiction, Marissa Moss. You may be familiar with Marissa’s popular Amelia’s Notebook series or her other fictional series including Max Disaster and Daphne’s Diary. She is also the author of several highly-praised (and highly-researched) journal-style historical fiction novels and a half-dozen non-fiction biographical picture books telling the remarkable stories of remarkable women. Here, Marissa shares the backstory of the history she writes.

I love stumbling on little-known stories that grab my imagination and sense of history. Those are the stories I turn into books, the tales of courage and achievement against the odds that deserve to be widely known. Is it a coincidence that many of these undiscovered gems are about women?

Women have mostly been absent from the grand epic of history. The ones that are recognized are an elite few, Queen Elizabeth I, Cleopatra, Marie Curie. Much more fascinating to me are the ordinary women doing extraordinary things.

Maggie Gee is one such woman. I found her in a local newspaper story about WWII veterans, published naturally on veteran’s day. I didn’t know that women had flown warplanes in WWII and it seemed like an important story for kids (and adults) to know about.

I looked Maggie up in the phone book, called her and asked for an interview. That interview and the many conversations that followed became SKY HIGH: THE TRUE STORY OF MAGGIE GEE. What impressed me about Maggie was her drive, her optimism, her courage. She didn’t see barriers, but opportunities. Sure, there was discrimination against her, both as a woman, and as a Chinese-American, but she barely mentioned such problems when she talked about her life. Although her mother had lost her U.S. citizenship when she married Maggie’s father, a Chinese immigrant, that didn’t deter her from working as a welder on Liberty ships during the war, nor from encouraging her daughter to join the Women’s Army Service Pilots. After the WASP were disbanded, Maggie went on to charge through more doors, becoming a physicist and working on weapon systems at the Lawrence Livermore labs, another job that was rare for a woman, let alone an Asian-American woman.

I thought of Maggie’s grit, her enthusiasm for taking risks and following her dreams, when I started looking for a Civil War story. I wanted to find a woman who had made similar daring choices, but I wasn’t sure where to look. So I read widely, about both the North and the South. I learned that more than 400 women had disguised themselves as men and fought as soldiers for one side or the other. Could one of those women be the story I wanted?

I plowed through books about nurses, soldiers, spies, but they all lacked some essential characteristic. Some were there to be with a husband, brother, father, or fiancé. Some were adventurous, but not particularly patriotic or admirable. Very few cared about the issue of slavery.

Sorting through all these women, I found one that seemed promising. The first book I read about her didn’t tell me much, but it gave me enough of a sense that I wanted to learn more.When I saw she’d written her own memoir of her soldiering life, that I could hear in her own voice her motives and intentions, it was like finding a treasure trove.

That woman was Sara Emma Edmonds, aka Frank Thompson.She was everything I’d hoped for – she had integrity, bravery, loyalty to the Union. As a bonus, she wrote movingly about the horrors and wrongs of slavery. But there was more. Edmonds was the only woman to successfully petition the government after the war for status as a veteran. She wanted her charge of desertion changed to an honorable discharge, and she wanted a pension for her years of service. Suffering from malaria she’d caught in the Virgina peninsula campaign early in the war, she needed medical care she couldn’t afford without it.

It took several years and two separate acts of Congress, but Edmonds received the legal recognition she so richly deserved.Men she’d served with testified on her behalf, praising her steadiness under fire, her work as a battlefield nurse, a general’s adjutant, a postmaster, and even a spy.

Hers was a great story, a vast canvas that covered many of the pivotal battles of the war. Now that I’d found my subject, I had to shape this big life into a book. And a short book at that. I first wrote about Sara Emma Edmonds for a picture book, choosing to showcase her first spy mission, one emblematic event to stand for such a complicated life. That text became NURSE, SOLDIER, SPY, beautifully illustrated by John Hendrix, and published this past April by Abrams.