Paulette Bates Alden's Blog

March 10, 2021

The Empty Cell ChainofIslands/OneBook Selection

The Empty Cell is going to be the ChainofIslands/OneBook selection for the Key West library/Monroe County FL libraries. There was a virtual event on March 31.

October 29, 2020

Greenville native pens novel based on Willie Earle lynching

It wasn’t until 2011 that Paulette Alden first learned about the lynching of Willie Earle in the pages of the New Yorker.

The piece was written by British journalist Rebecca West, who was sent to cover the trial in Greenville in 1947. Earle, a 24-year-old Black man, had been charged in the death of a white Greenville cab driver who was found bleeding and beaten on the side of the road after being robbed by a Black passenger. Earle was arrested and taken to the Pickens County jail, where he was seized by a mob of angry cab drivers and brutally killed.

October 8, 2020

Greenville author explores city’s past racial injustice with new novel, The Empty Cell

Paulette Alden was born the same month in the same year in the same city that the Willie Earle trial took place. But it would be more than 70 years before the Greenville native would fully examine her hometown’s most infamous case to better understand the present with her new novel of historical fiction, The Empty Cell.

May 5, 2014

A Writer Learns about Creative Process from Two Artists: Hopper and O’Keeffe

“So much of every art is an expression of the subconscious, that it seems to me most of all the important qualities are put there unconsciously, and little of importance by the conscious intellect. But these are things for the psychologist to untangle.” —Edward Hopper

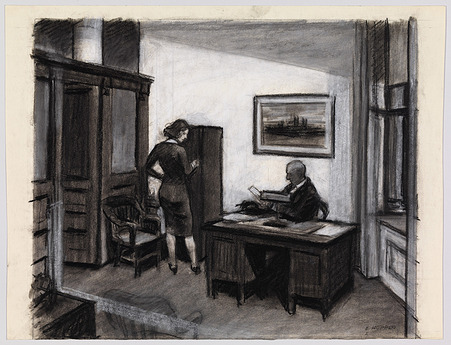

Hopper study for Office at Night

Whenever I’m trying to write something, it helps to remember that most works go through stages of a creative process. Even something like this blog post—and I’m not saying I’m penning War and Peace here—follows a somewhat predictable series of steps. I never get what I’m after the first time through, as much as I’d like to. With a long, complex project like a novel, I especially have to keep in mind that I’m going to go through a lot of process. It helps to remember this, and to recognize what stage I’m in. I’ve posted about Louise DeSalvo’s excellent “Stages of the Writing Process,” but many other people have described how a creative work proceeds from the initial impulse through the finished form.

The basic progression goes something like this: A project starts with some intimation, idea, image, hunch, object, experience or desire to bring something into being; it then evolves through a germination period as the writer or artist gets to work, going through drafts, sketches, and approximations in an effort to get closer to whatever the vision is. Perhaps he or she encounters technical problems or simply isn’t satisfied, without knowing what to do or how to “fix” the piece. The person may ask for feedback from others at some point. Often time must pass as the subconscious wrestles with the problem, and the artist simply has to wait. Eventually (God help us) the artist or writer comes to know what the piece wants to do and be, and is able to complete it. I find it helpful to keep this process in mind as I try to create something, be it a blog or a book. Doing so allows me to be more patient and accept that the time it takes to move through various stages is often necessary to bring a creative piece to fruition.

The Walker Art Center’s current exhibit, “Hopper Drawings: A Painter’s Process,” on loan from

Hopper study for Office at Night

the Whitney Museum of American Art, provided me not only an opportunity to view some of Hopper’s paintings and drawings, but also the opportunity to learn something about his creative process. It’s always interesting and valuable for me to see how the creative process works in another medium. The Hopper exhibit also reinforced the notion that in art the real or concrete is transformed by the artist’s (or writer’s) imagination—and process— into something new and different. That brought to mind something similar I had read about Georgia O’Keeffe’s creative process, which I’ll tell you about in a moment.

According to the Walker’s exhibit notes, “More than anything else, Hopper’s drawings reveal the continually evolving relationship between observation and invention in the artist’s work . . . The show surveys Hopper’s significant and underappreciated achievements as a draftsman, and pairs many of his greatest oil paintings—including Office at Night (1940), an important piece from the Walker Art Center’s collection—with their preparatory drawings and related works.” It’s this connection between observation and invention that interests me the most. As Carter Foster, the curator of the drawings for the Whitney Museum said in an interview, “Hopper had to have real details. He had to go out and look for it in the world. He was walking the streets of New York constantly, absorbing the world and putting it into his paintings. So the real was very important. But to turn it into something poetic, he had to do something to it.”

Because Office at Night is one of Hopper’s most iconic paintings, I’ll focus on that particular piece here.

According to Gail Levin in Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography, diary entries kept by his wife Jo describe a “creative dry spell” that Hopper had in December, 1939 and early January, 1940. At her insistence they attended an exhibition of Italian masters at the Museum of Modern Art, paying particular attention to Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. She enthused about the painting, but Hopper dismissed it as “only another pretty girl picture” [!]. Levin comments that perhaps this dismissive characterization betrayed “some deeper stir.”

Hopper study for Office at Night

Levin recounts how the next evening Hopper declared that “he needed to go out to ‘meditate’ a new picture.” Apparently his journey around New York that night included a trip on the elevated train. As we see in the finished Office at Night, the angle at which the viewer sees the office suggests that one is looking in from a passing elevated train. Indeed, Hopper later informed Norman Geske, the curator of the Walker at the time it acquired the painting in 1948 [for $1,500], that the idea for the painting was “probably first suggested by many rides on the ‘L’ train in New York City after dark glimpses of office interiors that were so fleeting as to leave fresh and vivid impressions on my mind.”

The next day Hopper purchased canvas for a new painting. Jo noted in her diary, again according to Levin, that “he has a black and white drawing of a man at a desk in an office and a girl to the left side of the room and an effect of lighting.” He continued to make sketches to adjust the image on paper to more closely match his vision of the painting. Jo served as his model for the female figure, as she often did. In her journal she writes:

E. has his new picture drawn in charcoal. He is doing things with no end of preparation–had 2 brightly finished crayon sketches. Seems to seek delays for beginning a canvas. It’s a business office with older man at his desk & a secretary, female fishing in a filing cabinet. I’m to pose for the same tonight in a tight skirt–short to show legs. Nice that I have good legs & up & coming stockings.

Go, Jo!

He worked on the painting every day, and by February 19, Jo observed, “Each day I don’t see how E. can add another stroke” but that his changes were making “this picture . . . more palpable—not fussy . . . reduced to essentials . . . so realized.”

Hopper’s Office at Night

People read different narratives into Office at Night, which has about it something strange, mysterious, unspoken. The relationship between the two figures, the voluptuous woman in blue, and the man at the desk, provokes speculation and suggestion. The tilt of the painting, almost as if the room will slide off the canvas, is a brilliant touch. It’s interesting to note that in an earlier sketch, the floor is not at the angle depicted in the final painting. It seems to have developed through his drafts.

The lighting is also worth noting. Wieland Schmeid, in Edward Hopper: Portraits of America, notes that as in other nighttime scenes, in Office . . . Hopper had to realistically recreate the complexity of a room lit by multiple, overlapping sources of varying brightness. In Office at Night, the light comes from three sources: an overhead light, the lamp on the man’s desk, which sheds a small puddle of intense light, and from a street-light shining in the open window on the right-hand side. Hopper reported that the overlap of the light from the ceiling fixture and the light from the exterior created particular technical difficulties, since they required him to use different shades of white to convey the idea of degrees of shadow.

Reading about and viewing Hopper’s creative process in his drawings reminded me of something I had read about Georgia O’Keeffe in the “Introduction” to Creativity and the Writing Process, by Olivia Bertagnolli and Jeff Rackham. It’s fascinating to read what O’Keeffe described regarding the stages her own work progressed through as she moved from painting actual objects, through various drafts that didn’t satisfy her, to a period in which her subconscious worked on the problem, to a breakthrough in which her imagination transformed the original material into something new and more creatively satisfying to her.

This from Bertagnolli and Rackham’s “Introduction”:

Analogies between the process of writing and the process of painting are not uncommon. Our own understanding of creative process may be clarified by American artist Georgia O’Keeffe’s journal description of her particular process written after she had worked on a series of paintings titled Shell and Old Shingle. As writers collect experiences, artists collect objects. Georgia O’Keeffe gathers bones, rocks, pieces of wood—all subjects of her paintings. Once, rather absentmindedly, she recalls, she picked up an old barn shingle and took it home where she placed it next to a clam shell. A few days later she noticed the shell against the shingle and began painting. She painted what she saw: the literal shingle and shell. Dissatisfied with the results, she painted the shingle and shell over and over, much as a writer might move through several drafts or revisions. But in each painting the shell remained a shell, the shingle a shingle; nothing emerged with any sense of spirit. Being the true artist, O’Keefe didn’t give up. After painting the shingle and shell a fourth time, she sensed herself moving beyond the literal subject and painted instead the imagined one. This time the shingle became a dark space floating above a white space. ‘The shapes,’ she writes, ‘seemed to sing.’ Months later, O’Keeffe painted a misty landscape of a mountain outside her window and realized sometime afterward that the mountain in the painting had taken on the shape of the shingle on the table. She had allowed the literal shingle and shell to become fictionalized by her imagination. Her early attempts to capture the literal material, conscious and controlled attempts, failed to satisfy her. The final painting was an uncontrolled, spontaneous act, the result of allowing the experience to incubate, and of having the patience and trust to allow the imagination to discover for itself the mountain in the shape of the shingle. A similar process happens to most artists—painters or writers—although never in quite the same way, even for the same person. The process cannot be hurried or forced or willed, but when the fictionalized memories of our experiences surface, when the image begins to sing, we must be ready.

I find keeping Hopper’s and O’Keefee’s creative processes in mind as I struggle with the new novel I’m writing reassuring–and inspiring.

Shell and Old Shingle VI

March 26, 2014

Examining a Passage from The Goldfinch

I posted earlier on the brilliant, beautiful novel The Goldfinch. I had to do so in broad swaths, given how dense in character and plot the novel is, just to give you a taste of it. But now I want to go back and drill down on just one passage, to analyze what makes the writing—to me, at least—so marvelous. There are so many paragraphs I could choose, but I was particularly taken with the following description of how Hobie, the furniture restorer who takes in the young, homeless Theo, trains him in the art and craft of fine furniture repair.

As you read the passage, make a mental note of how you respond to it, and what you notice in particular (There will be a test . . .).

Auction houses all over the city called him, as well as private clients; he restored furniture for Sotheby’s, for Christie’s, for Tepper, for Doyle. After school, amidst the drowsy tick of the tall-case clocks, he taught me the pore and luster of different woods, their colors, the ripple and gloss of tiger maple and the frothed grain of burled walnut, their weights in my hand and even their different scents—”sometimes, when you’re not sure what you have, it’s easiest just to take a sniff”—spicy mahogany, dusty-smelling oak, black cherry with its characteristic tang and the flowery, amber-resin smell of rosewood. Saws and counter-sinks, rasps and rifflers, bent blades and spoon blades, braces and mitre-blocks. I learned about veneers and gilding, what a mortise and tenon was, the difference between ebonized wood and true ebony, between Newport and Connecticut and Philadelphia crest rails, how the blocky design and close-cropped top of one Chippendale bureau rendered it inferior to another bracket-foot of the same vintage with its fluted quarter columns and what he liked to call the “exalted” proportions of the drawer ratio.

Okay, Students! How did you respond to this passage? What was the first thing that struck you? Did you like it, dislike it, love it, indifferent, irritated, what?

I wish we were sitting around a circle and I could hear your answers, which I’m sure will be much more interesting than mine! And different. You’ll just have to let me know.

Meanwhile, I’ll give you my take.

The first thing that strikes me is how much Donna Tartt knows about furniture restoration! She’s done her homework, boys and girls. She’s the smartest girl in the class. And it pays off. What authority this passage contains! It absolutely convinces us that the world she’s creating is real, solid, and authentic. We trust that she knows of which she speaks, so we can give ourselves over to the story completely. Surely she researched these esoteric details with someone extraordinarily versed in furniture restoration. Did she takes notes? No doubt. But I’ll wager the best note-taker in the world couldn’t transform mere research into this sterling passage of prose.

Beyond authority, what strikes me the most here is how sensitive and skillful she is in terms of language itself: words, the sounds they make, how they join together into sentences that create rhythm and meaning. Most of all, her words awaken our senses. Here, words give us the deep pleasure that only our senses can provide. It’s quite a paradox. Most of the time in our so-called real lives, our senses are on pause, slumbering, acclimated to the quotidian. But when we read a passage like this, loaded with extraordinarily precise, sensory detail, our senses wake up and really pay attention, pulling our whole mind into the act.

As soon as I read the word “tick,” I hear a tick. It’s such an onomatopoetic word. ” . . . Amidst the drowsy tick of the tall-case clocks.” I like the way the two “ts” sound tick-tocky, and those “tall-case clocks”: Don’t tall, thin grandfather clocks come instantly to mind as you begin to picture the repair shop? This line about the clocks is a great example of “strong specification”— the opposite of Henry James’s “weak specification,” in which the eye glides over the words while the mind nods off—because the writer isn’t giving us concrete, specific, sensory detail—the foundation of good writing. An example of weak specification would be “amidst the sound of ticking clocks.” No distinct “tick” sounding in your ear and only a vague picture created in your mind’s eye.

. . . he taught me the pore and luster of different woods, their colors, the ripple and gloss of tiger maple and the frothed grain of burled walnut, their weights in my hand and even their different scents—”sometimes, when you’re not sure what you have, it’s easiest just to take a sniff”—spicy mahogany, dusty-smelling oak, black cherry with its characteristic tang and the flowery, amber-resin smell of rosewood.

To me this is a delicious passage of prose! I love the juxtaposition of the words “pore,” so staccato, and “luster,” so luxuriously drawn-out, conjuring up a beautiful sheen. Who can resist the “ripple and gloss of tiger maple” and “the frothed grain of burled walnut?” You want to run your fingers over them. She even fires our tactile sense with “their weights in my hand.” And doesn’t your nose just perk up at those wood smells: “spicy mahogany, dusty-smelling oak, black cherry with its characteristic tang and the flowery, amber-resin smell of rosewood.” Wonderful.

We get absolute particulars in the cataloguing of the repair shop tools. But even these are alliterative and precise, interesting because of their novelty: “rasps and rifflers, bent blades and spoon blades, braces and mitre-blocks . . . ”

I study this passage to learn from it. I’m always my first, best student. Analyzing it won’t make me write like Donna Tartt (I wish). And it’s not always necessary or desirable to write this kind of lush, dense description. But there are things to learn from here. Most of all, it reminds me to try harder in my own writing.

I tried to research how Tartt knows so much about furniture restoration. I didn’t get too far before I came upon an interesting interview with her by Mick Brown in the UK’s The Telegraph, entitled “If I’m Not Working, I’m Not Happy.” You might enjoy hearing some of what she had to say, about her personal life and her way of writing:

She is unmarried. “My idea of hell is a crowded and oppressive domestic life. Some people love that. It’s absolutely my worst nightmare.” When I ask what I should write about her personal life, she laughs. “As little as possible…”

Her deepest satisfaction is shaping a sentence – the right word, the seemly metaphor. She can happily move a comma around “for hours”.

Her books may be big, but she describes herself as “a miniaturist – painting a wall-size mural with a brush the size of an eyelash; doing very tiny, very detailed work, but over a large space and over a long period of time. That’s why it takes so long.”

Her working method is Byzantine. She writes in longhand in large spiral-bound notebooks, adding thoughts and corrections in red, blue and then green pencil, and stapling index cards to them to keep track of plot and characters. When it all starts getting “too messy” she types the manuscript into the computer, then prints out the drafts on colour-coded paper. “I can pick up the pink draft, and I know that’s the first one; or the grey draft, or the most recent one is the blue. So if I need something from an older draft I know where to find it. My French teacher, many years ago, told me this, and it actually works.”

On the wall of her office is a quote from Paul Valéry: “Disorder is the condition of the mind’s fertility.”

Hearing about her process actually gives me hope. It takes her a long time (Goldfinch took ten years to write). She loves shaping a sentence. She produces a final product over many drafts.

See, fellow writers? A book doesn’t spring from someone’s head like Athena sprang from the head of Zeus, fully formed! There’s hope for us.

Now, what are your thoughts and reactions to the passage I quoted from The Goldfinch?

March 13, 2014

The Goldfinch: A Brilliant, Beautiful Novel

A friend and I were talking about hyperbole in book blurbs and reviews the other day (I confess I don’t mind a little hyperbole concerning my books). He told me about Rich Bass’s blurb on the back cover of Cold Mountain when it came out: “It seems possible to never want to read another book, so wonderful is this one.”

I’m not willing to go that far. But after Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, I suspect it will be a long time before I read another novel that is as brilliant and beautiful as this one.

The Goldfinch is huge in many ways. For starters, it’s long: 771 pages. So if you’re not up for the long haul, step aside

In addition, it’s “wordy.” Full of fulsome descriptions. If you like a clean, simple, cut-to-the-chase style, Finch is not for you.

If you’re not that interested in highly elaborate (but accessible) discussions of art, furniture restoration, what it feels like to be high or in love, to be terrorized, to be saved, to be lost, to be found, to be good, to be bad, to be human–go elsewhere.

But if you want to have a reading experience that may make you wonder if you’ll ever want to read another novel, I recommend The Goldfinch.

Why is it so great? You’re entitled to ask.

Let me count the ways.

I give it the highest marks—over the top—for its brilliant characterization; its brilliant sense of place (Manhattan, Las Vegas, Amsterdam); its brilliant plot (quite Dickensian, with one damn thing right after another!); its brilliant description. Most of all the brilliant mind that conceived of and executed this book. How can one person know so much? Brilliant, brilliant, brilliant. I can’t begin to capture its brilliance here (not being brilliant myself). Let me just say that this was a book where I wished I could quote every line for you. Ever single line of 771 pages, and you wouldn’t be disappointed by a single one.

Here’s what’s at the heart of this big book: a small painting, “the smallest in the exhibition, and the simplest: a yellow finch, against a plain, pale ground, chained to a perch by its twig of an ankle.”

Theo, the book’s extraordinary narrator, rescues this painting, a 17th century Dutch masterpiece, from the destruction caused by a terrorist bomb in the Metropolitan Museum of Art that kills his mother and nearly him when he’s thirteen. Follow this painting all through the novel. It will animate the highly suspenseful plot, but beyond that, it is the overarching vehicle for all this ambitious book takes on: love, loss, longing, obsession, friendship, and the power of art itself. In the process, The Goldfinch contains some of the most vividly detailed writing and richly drawn characters and relationships you’ll encounter in contemporary literature.

Let me introduce you to some of the memorable players:

There’s Andy, who becomes Theo’s best friend in grade school when they both skip ahead a grade because of high test scores: ” . . .poor Andy had always been a chronically picked-upon kid: scrawny, twitchy, lactose-intolerant, with skin so pale it was almost transparent, and a penchant for throwing out words like ‘noxious’ and ‘chthonic’ in casual conversation.”

There’s Boris, the irrepressible, survival-savyy Ukrainian waif who befriends Theo when they’re schoolboys in Las Vegas, and who reappears to play a crucial role in Theo’s adult life in New York. “Boris . . . Long-haired, narrow-chested, weedy and thin, he was Yul Brynner’s exact opposite in most respects and yet there was also an odd familial resemblance: they had the same sly, watchful quality, amused and a bit cruel, something Mongol or Tartar in the slant of the eyes.”

There’s Hobie, a loveable, dreamy, old-world, artisanal furniture restorer who takes in the lost Theo and nurtures him, teaches him, and loves him. “Though I [Theo] sometimes worked down in the basement with Hobie for six or seven hours at a time, barely a word spoken, I never felt lonely in the beam of his attention: that an adult not my mother could be so sympathetic and attuned, so fully there, astonished me.”

There’s Pippa, the unrequited love of Theo’s life: ” . . .—we’d been there [at a restaurant] for hours, laughing over little things but being serious too, very grave, she being both generous and receptive (this was another thing about her; she listened, her attention was dazzling–I never had the feeling that other people listened to me half as closely; I felt like a different person in her company, a better one, could say things to her I couldn’t say to anyone else, certainly not Kitsey [Theo’s fiancé], who had a brittle way of deflating serious comments by making a joke, or switching to another topic, or interrupting, or sometimes just pretending not to hear), and it was utter delight to be with her, I loved her every minute of every day, heart and mind and soul and all of it, and it was getting late and I wanted the place never to close, never.”

There are plenty of others you have to meet—Theo’s mother, his father, Mr. and Mrs. Barbour, Zandra, Kitsey, Horst . . .

But most of all, there’s Theo Decker, the protagonist, whom we follow from age thirteen into his mid-twenties. Here toward the end of the novel is Theo reflecting on life:

. . . I’m hoping there’s some larger truth about suffering here, or at least my understanding of it–although I’ve come to realize that the only truths that matter to me are the ones I don’t, and can’t understand. What’s mysterious, ambiguous, inexplicable. What doesn’t fit into a story, what doesn’t have a story. Glint of brightness on a barely-there chain. Patch of sunlight on a yellow wall. The loneliness that separates every living creature from every other living creature. Sorrow inseparable from joy . . .

It’s Theo’s incredibly intelligent, perceptive, sensitive, damaged consciousness that pervades the novel and makes it the brilliant book it is. We live through so much life, death, trauma, danger, disruption, obsession and passion with Theo that there’s the possibility of being wrung out emotionally. But for readers who give themselves over to Theo and embrace him and his story fully (as I did), you won’t be disappointed. If you’re like me, you’ll want to start reading it all over again.

Not many novels come along that are this exceptional.

And that’s not hyperbole.

March 4, 2014

The Silent Wife: A Fascinating Novel Both Psychologically and Technically

I first became interested in The Silent Wife in when I read an August 4th, 2013 piece in The New York Times. The article described how the novel—a “sleeper,” written by an “unknown” Toronto writer and released as a paperback original (as opposed to a hardcover, which signals the publisher intends to push the book)–had vaulted its way onto The New York Times best-seller list. The book received some crucial attention from a handful of reviewers, and caught on via word of mouth.

I first became interested in The Silent Wife in when I read an August 4th, 2013 piece in The New York Times. The article described how the novel—a “sleeper,” written by an “unknown” Toronto writer and released as a paperback original (as opposed to a hardcover, which signals the publisher intends to push the book)–had vaulted its way onto The New York Times best-seller list. The book received some crucial attention from a handful of reviewers, and caught on via word of mouth.

I read that the author, A.S. A. Harrison, had died of cancer at 65, a few weeks before The Silent Wife was published. She was aware that numerous other countries had bought publishing rights and she knew the book was getting wonderful endorsements from other authors. It is sad to think that she didn’t live to see her novel receive the acclaim that it has garnered. But I imagine she knew how good the book is. You can’t write a novel this accomplished without knowing it.

The Silent Wife has been compared to Gone Girl, by Gillian Flynn. It covers similar territory, a “dark, psychological thriller about a broken marriage,” as the Times described it. Like Gone Girl, it’s told in alternating “Him” and “Her” chapters. I only got 100 pages into Gone Girl before I put it down. I saw Gillian Flynn speak at the Key West Literary Seminar this year (on “The Dark Side: Mysteries, Crime and the Literary Thriller”). She was very bright, and articulate in her defense of writing “bad women,” women who can be evil, mean, bad, or selfish–though honestly, plenty of other authors since time immemorial have plowed that ground. I found Gone Girl smart and well-written, but it just didn’t interest me. I wonder if it has something to do with age. Flynn is in her forties (and looks about thirty) and Harrison was 65, having worked on The Silent Wife for ten years. Or maybe my preference for SW had to do with GG being written in first person, and SW in third, with a knowing, authoritative narrative voice, which interested me technically (more on this in a moment). For whatever reasons, I found The Silent Wife far more fascinating and accomplished, and more mature, than what I read of Gone Girl.

photo by Harrison’s husband John Massey

Susan Angela Ann Harrison (she used initials to disguise her gender) had previously written a porn novel with the artist AA Bronson which was quickly banned when it was published in 1970. Her 1974 book, Orgasms, was a series of interviews with women speaking frankly about their sexual climaxes. (In my commitment to researching an author thoroughly (wink), I tried to order Orgasms but alas, it’s out of print.) Harrison collaborated on two other non-fiction books, one about striptease, experimenting with it herself, and another involving case studies in psychotherapy titled Changing the Mind, Healing the Body. She also wrote Zodicat Speaks, a guide to feline astrology. Her friend, the author Susan Swan, said of Harrison, “She deconstructed prettiness. She wanted to be larger than life, and she was.” Swan’s daughter, Samantha Haywood, a neophyte agent, took her on as a client in 2004. For the next decade, Harrison’s work was repeatedly rejected. But she kept at it, telling herself to “write better, Susan,” and donning industrial earmuffs to keep out noise.

What’s not to love—and admire—about her!

I was captivated by The Silent Wife from the opening paragraphs.

It begins:

It’s early September. Jodi Brett is in her kitchen, making dinner. Thanks to the open plan of the condo, she has an unobstructed view through the living room to its east-facing windows and beyond to a vista of lake and sky, cast by the evening light in a uniform blue. A thinly drawn line of a darker hue, the horizon, appears very near at hand, almost touchable. She likes this delineating arc, the feeling it gives her of being encircled. The sense of containment is what she loves most about living here, in her aerie on the twenty-seventh floor.

Notice how we’re placed inside the point of view of the character, Jodi, but there is also a narrative voice that is beginning to describe her psychologically. Certain words—”encircled,” “containment”—seem suggestive of more than the physical landscape. There is a distance in the narration, created partly by the use of her full name, as opposed to just “Jodi is in her kitchen . . .” We hear a voice that is not Jodi’s but the narrator’s, who is taking care to select the precise details to begin to build not only the external world but Jodi’s interior one.

The second paragraph:

At forty-five, Jodi still sees herself as a young woman. She does not have her eye on the future but lives very much in the moment, keeping her focus on the everyday. She assumes, without having thought about it, that things will go on indefinitely in their imperfect yet entirely acceptable way. In other words, she is deeply unaware that her life is now peaking, that her youthful resilience—which her twenty-year marriage to Todd Gilbert has been slowly eroding—is approaching a final stage of disintegration, that her notions about who she is and how she ought to conduct herself are far less stable than she supposes, given that a few short months are all it will take to make a killer out of her.

Brilliant. Here the third-person limited omniscient narrator (limited to Jodi, not going into anyone else’s perceptions or psyche, such as an unlimited omniscient narrator could and would) tells you the whole story. We learn that Jodi will be transformed into a killer over the course of the book, so the plot becomes not “what will happen,” but “how does this happen”– much more psychologically enticing. I’m hooked as a reader, both psychologically and technically. I’m in cahoots with this all-knowing, cool, sophisticated narrator who knows more about Jodi than Jodi will ever know about herself. It’s as if we—the narrator and I—make eye contact over Jodi’s head. This narrator, having been established so authoritatively early on, can now arc over the book, with a voice that can “tell” the story in a way that is more shaping and knowing than just having Jodi live through it experientially. This narrative voice is an example, albeit an extreme one, of what I often try to teach writing students, which is the use of a limited omniscient narrator who can both show and tell the story.

In the second chapter, a “Him” chapter after the opening “Her” chapter, Todd takes center stage. Here the point of view is more centered in him, without the narrator commenting so directly about the character. “He likes getting an early start, and over the years he’s pruned his routine down to the fundamentals. His shower is cold, which kills the temptation to linger, and his shaving gear consists of canned foam and a safety razor. He dresses in the semidarkness of the bedroom while Jodi and the dog [who is named Freud!] sleep on . . .”

Todd is a serial philanderer but Jodi accommodates his behavior as long as he doesn’t bring it home:

from Jodi’s opening chapter:

It simply doesn’t matter that time and time again he gives the game away, because he knows and she knows that he’s a cheater, and he knows that she knows, but the point is that the pretense, the all-important pretense must be maintained, the illusion that everything is fine and nothing is the matter. As long as the facts are not openly declared, as long as he talks to her in euphemisms and circumlocutions, as long as things are functioning smoothly and a surface calm prevails, they can go on living their lives, it being a known fact that a life well lived amounts to a series of compromises based on the acceptance of those around you with their individual needs and idiosyncrasies , which can’t always be tailored to one’s liking or constrained to fit conservative social norms.

But as the novel opens, Todd is changing the terms of their relationship. He has fallen for a college student, the daughter of his best friend, a hot girl who makes him feel young, virile, and who lifts his depression. Naturally, Natasha becomes pregnant (and Todd wants a child, though Jodi didn’t), injecting her own agenda into the mix. Todd, though admittedly led around by the nose (or another body part), is written with complexity and depth, as opposed to just being portrayed as a scoundrel. Some readers may view him as such, but I found both Jodi and Todd fully and deeply realized as “real,” believable people, with complex desires, motives, back stories, and unconscious motives as well as conscious ones, swept along by needs and emotions they can’t control or understand. A novel like The Silent Wife lets us see what lies behind lives that seem, on the surface, inexplicable. Be sure to read carefully when you get to Chapter Twenty-five.

One of the fascinations with the novel is to see the same relationship and situation from two totally different perspectives—his and hers. How often in life we wish we could know the mind of someone with whom we’re embroiled, whose thoughts, feelings and experiences, despite some stabs at communication, remain a cipher to us. At one point in the story, after Todd has left Jodi and moved in with Natasha, Jodi invites him back “home” for dinner. She sees it as a chance to reunite with him, and indeed, after dinner they make love. “I’ve missed you,” he says. “I’ve missed coming home and I’ve missed getting into bed with you and I’ve missed waking up beside you—and all I can say is that I must have been out of my mind to think I could give you up.”

And he means it when he says it–in the moment. But for him it is just a moment. For her it means something; she reads into it. “The way it worked out [inviting him to dinner] she couldn’t have wished for a more idyllic coming together, a more gratifying renewal of their bond.” She expects that they will reunite.

The next day, Jodi is advised by Todd’s lawyer’s secretary that she needs to get a good divorce lawyer. Soon after, she is informed that Todd is going to exercise his legal right to make her vacate the apartment that has been her home for twenty-something years—that contained sanctuary we learned about in the first paragraph. The outrage and pain she feels will push her towards murder.

The Silent Wife is not only psychologically and technically deft, it’s a riveting page turner. It has the requisite plot twists and turns, but it is far better than your average “thriller.” It goes well below the surface to give us insight into why two apparently nice, normal, functioning people (I should note that Jodi is even a psychologist who counsels others) are coming apart at the seams. A.S.A Harrison did herself proud with this book. It’s a shame that we won’t see another from her.