Emma Darwin's Blog

May 4, 2023

Itchy Bitesized 24: Five Thoughts About Thinking in Acts

I was wary of books about story-structure for a long time, because they all seemed to be written by script-writers, not novelists - and novelists are not in the business of writing a skeleton to help a group of actors flesh out their characters-in-action well enough to keep the audience sitting down in the dark for a couple of hours. We are in the business of story-telling. I only understood why thinking in acts is so useful to a writer when I encountered John Yorke's Into the Woods, and was encouraged by the fact that Yorke started in TV: a TV series, like a novel, is a multi-sitting experience. You need a lot more story-material than a film does and, crucially, you don't just have to keep your audience once, you have to keep bringing them back.

1) You are already thinking in acts as soon as you're thinking about what happens to your characters in your story. Beginning, Middle and End is the fundamental experience of human life, so when we're imagining stories, we can't help shaping them that way too, with the twist that our equally human drive to make sense of things drives us to tell stories in terms of cause-and-effect

2) You don't have to think in acts to write a strong story with a compelling narrative drive, but thinking in acts can help you get to grips with how to build the chain of cause-and-effect, and how to keep the reader reading. What is different at the end, from how things were at the beginning? How did what went on in the middle get us there?

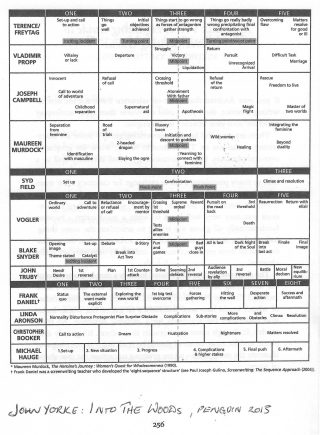

3) The midpoint is crucial in almost every one of different writers' attempts to lay out the structural fundamentals of the great stories told in past and present. Yorke actually prints a table of what he freely admits is "a gross simplification" of some of the major books, to make the point that all of them are just different ways of trying to get a handle on "the true shape of story".

4) Three Act Structure leaves the novelist with very little help in preventing that looooonnnnng Middle from sagging. In a film it might be an hour's watching, but in a book it might be many hours' reading. My breakthrough was realising that five acts works for me, because it divides the Middle up into three. My crime writer friend C S Green, on the other hand, works in four acts, with the Midpoint a single scene "holding everything else up like a tentpole".

5) Act structure is fractal. If the novel is your story, each act also needs its own beginning-middle(s)-end structure. You could each of those units chapters, if you liked, and if each chapter has a beginning-middle-end you could call each unit a scene. A scene, too, has a beginning-middle-end. Indeed, if you get feedback that a page or a paragraph is rather stodgy or rambly, look at its structure: does it, too, lead onwards? How are things different by the end?

*********

I love helping writers with their work, as a one-off appraisal or more extended tutoring and mentoring. If you'd like to know more, or if your writers' group or organisation is interested in a workshop, tutorial or talk, click through to my website to find out more, and get in touch.

April 18, 2023

Three Things About "It's Tough Out There"

It's tough out there, we all tell each other ��� trying to get books published, trying to get them bought, trying to keep them published ��� and figures such as the ALCS's confirm it. 'Twas ever thus, of course (which is why the Royal Literary Fund has existed since 1790): writers are in a low-unit-cost, high-volume industry, competing for readers who have ever more non-book ways of spending their leisure time and income.

And since the background (gender/class/culture/ethnicity/origin/sexuality/neuro-type) of publishers and published writers doesn't align with national demographics, that disparity can constitute a huge barrier to entry for those whose faces don't fit. If you are campaigning for programmes and prizes to change that, or making an academic or journalistic study of the industry, then those facts matter not just for social justice, but for the flourishing of the arts and the cultures they nourish.

But if you are developing your own creative processes for good and successful writing, then letting yourself dwell on those facts may be actively unhelpful. Recently I was at a talk by poet and writer Sophie Hannah, founder of the Dream Author Coaching programme, and what she said makes huge sense to me as both a writer and a tutor/mentor. Essentially, there are facts, which you are often not in control of, and there are the thoughts and feelings you have about those facts, which you can control. Unpicking the difference, says Sophie, is one key to making a successful (in your terms) life as a writer.

But if you are developing your own creative processes for good and successful writing, then letting yourself dwell on those facts may be actively unhelpful. Recently I was at a talk by poet and writer Sophie Hannah, founder of the Dream Author Coaching programme, and what she said makes huge sense to me as both a writer and a tutor/mentor. Essentially, there are facts, which you are often not in control of, and there are the thoughts and feelings you have about those facts, which you can control. Unpicking the difference, says Sophie, is one key to making a successful (in your terms) life as a writer.

Some years back I blogged about why paying attention to industry news can be really bad for your writing. What I hadn't grasped then is something that Sophie emphasises: that confirmation bias is hard-wired into humans for excellent reasons, but you can use it to your advantage, or let it thwart you at every turn.

Here's a thought experiment: As of today, there's a big book deal in the news. I can't find the details, just that it's a lot of money and publicity for a particular writer.

What is your first, reflex thought? Which of these is it most like?

I bet it's a celebrity.

I bet it's a cis white male, even if he isn't dead yet.

I bet it's the latest fashionable topic.

I bet it's the latest fashionable identity.

I bet it's a debut.

I bet the writer knows the right people.

I bet it's whatever I'm not ("not" as in not too old/the wrong identity/the wrong topic/too literary/too commercial/too genre/too out of the loop/too weak a writer).

I bet that's why there's no money left for my and my friends' books.

I bet that's because they think many readers will like the book.

I bet my book does different things.

I bet I could get a big book deal, because clearly there are big book deals to be got.

And if you're thinking, "How can I think anything when I don't know the details?" then that's kind of the point. I didn't tell you what the book/writer/������ are, because without facts, your response reveals some of your confirmation biases.

So: which of your thoughts about the industry shaped your reflex response? And what did you feel in tandem with that thought? Was it essentially positive, or negative, about your past, present and future writing life? More widely: of the emotions a writer might have felt at this news, which would be the most energising and motivating? What thought about this news would be most likely to foster that energy and motivation?

1) Negative confirmation biases are trying to keep you safe. Human consciousness has evolved to protect us by defaulting to pessimism. If you see something unidentifiably stripy in the forest shadows, it's wise to assume the worst and run away, not stride forward with your spear. OK, so you won't have eland steak for supper tonight, but at least you're sure not to become a tiger's afternoon snack.

But how does it serve your writing and writing life to assume the worst? Yes, there are risks out there: there are emotional dangers in being rejected; being judged; being disappointed in your sales; being told your work is bad; being frustrated by slogging at the Other Job to pay the bills; setting up as "an author" and finding yourself shamingly "unsuccessful" by whatever measures you care about.

None of these dangers are fun when you meet them - and it's not if, it's when. But even while it still hurts like hell and you've dead hopes to mourn, what has happened is past and the past tells you nothing about what the future can hold - unless you choose to let it. The playwright Somerset Maugham was asked if bad reviews upset him. He said that of course they spoilt breakfast, but you'd be a fool to let them spoil lunch. That seems to me a very helpful mindset.

2) If you constantly feed your mind stories about how difficult things are in publishing in general, or for your sort of writer in particular, confirmation bias ensures that you'll come to see more and more evidence of difficulties, and thereby miss or misinterpret evidence that might give you energy and hope. And when I say "stories" I mean just that: we are storied creatures, wired to understand facts by arranging them into chains of cause-and-effect based on our experience.

If the chain seems convincing to us (which it will because it's formed partly by our own biases), our narrative then acquires an aura of "truth", when in fact it's nothing of the kind, even if the original facts are. Do also note that your Inner Critic is a big part of the Protector team, and is an excellent storyteller. It will dress up as many things, including your Inner Industry Insider, in the effort to persuade you to stay its idea of safe - which is to say, unpublished.

That's not to be panglossian about it: it would be offensive to pretend that all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds, and it would be foolish to base mortgages and other life-plans on groundless optimism. And make no mistake: facts from your agent about what's selling, or the latest algorithms at The Online Retailer Who Must Not Named (especially if you're self-publishing), matter when you're talking industry strategy. But I'm talking about what you feed your day-to-day awareness, including reading industry reporting, doomscrolling on social media and chatting among writer friends.

3) Day-to-day, you can choose to ignore gloom-inducing facts, and starve your negative biases, by refuse to arrange those facts into stories of how tough it is and will be. And you can choose not to make a story about your own past sales or experience that defuels and demotivates you.

If your mind screams at the very idea of turning away from information and others' analysis, and is horrified by the idea of refusing to relate that stuff to your writing life, ask yourself: Why do I feel that I must know news all the time? Which parts of me are so frightened by the thought of not knowing this stuff? What do they feel I mustn't miss out on? What do they fear would happen if I don't know bad news as well as good?

I'd suggest it'll be some of these:

I need to know the facts, so as not to let myself in for failures. Perhaps, but remember to separate facts from thoughts-and-emotions, and from the stories you then form to connect them. The facts may be counted into decisions, but the thoughts and emotions they induce can be jettisoned. (On the Somerset Maugham scale, this is the mental shift from breakfast towards lunch. Coffee helps.)

If I act as if I have a great future I'll make rash decisions. Deciding not to feed and indulge your negative biases doesn't preclude going out and finding proper data, when you do need to make a decision. Indeed, if you haven't been indulging your negative biases for months, I'd argue you're better armed and wired to interpret that data in wise ways.

If I act as if I have a great future, I'll be shamed for being conceited and arrogant. Societies thrive on common interests and shared biases, and success beyond the norms threatens those equilibria. Whether it's the village child who is shunned for getting into the grammar school, or the tall-poppy film star who the tabloids suddenly turn on, societies go to a lot of trouble to bind our feet to their acceptable boot-sizes, either overtly with pre-emptive or retrospective shame, or covertly with well-meant advice and information - and underlying it all is the threat/fear of being deemed unacceptable and thrown out of the tribe altogether. Bren�� Brown's Daring Greatly is very good on this: you don't have to accept society's attempts to shame you.

If I act as if I'm a bestseller when I'm not, I'll be shamed in the industry for being foolish and deluded. But humans are strongly wired to take strangers at their own estimation, so a crucial reason for fostering your positive confirmation biases is that they will shape how you are perceived and received, in everything from how you enter a room or write a covering letter, to how you talk about your backlist to a journalist. Since you're a writer, you're more than capable of finding words to tell a story about your writing work which sounds cheerfully realistic about the present while also sounding bouyant about the future. Others can't shame you if you don't accept the shame they're offering. (And very often they're not offering it anyway: it's just your projection).

It's not the despair... it's the hope I can't stand, as John Cleese says in Clockwise. The hearts of kindly parent-figures (including their avatars inside ourselves) do honestly bleed at the thought of a child's lost hope, so they pre-emptively try to protect us by damping our hopes, because as we all know, happiness = reality minus expectations. But expectation is about probability, whereas hope is about possibility: you only need to know something is possible to get started, feeling the fear and doing it anyway and meanwhile fostering your Inner Somerset Maugham. Even more crucially, one way to make sure you never do your best work if to be so scared of getting your hopes up that you damp down every hope-driven urge to work harder and write even better. The only way to achieve what you want is to work as if your work is worth everything it could possibly get, and then some.

If I can't think that it's the industry making it so hard, then I'll have to believe it's all my fault. A good old industry moan among writer friends feels so comforting, and in one sense it's true: market forces, subjective judgements and sheer, darned good or bad cosmic luck are all part of what shapes our writing lives. And we all (I hope) are deeply irritated by the person who's so oblivious to how helpful their personal circumstances have always been that they're brightly convinced that anyone can achieve anything if they just try hard enough - ergo you haven't been trying hard enough.

But after your last good moan, did you come away feeling more hopeful and energised? Or were you despairing and defuelled? Was it a useful vent, and the next day you got stuck into a new initiative? Or did you crawl home and feel depressed and demotivated for days? Think back, and be honest with yourself.

And then, next time you catch yourself joining a group moan or clicking through to some gloomy news, try some of these:

What am I thinking and feeling as I read this?

Is it helpful and energising for my writing? How might I make the most of it?

Was it defuelling and demotivating? Do I wish I hadn't read it?

How might I reframe what I'm thinking about what I've read, so the feeling changes to something more helpful?

Which parts of me were thinking and feeling things? Were different thoughts coming from different parts? Why were they trying to protect me, and what from? How could I get them to understand that I've got this, and they can stand down?

Was it really, truly, something I need to know? What would have happened if I'd never known it?

How can I stop myself being exposed to unhelpful stuff I don't need to know?

How can I start actually feeling that success (in whatever terms you choose) is always available to me?

It takes quite a bit of time and meta-awareness to start retraining your reflexes towards helpful thinking in this way, though it's hugely worth it. The gentle way in, meanwhile, is not to scold yourself, but just to get curious, teasing facts away from thoughts and feelings as those questions do, and working out what's going on. There's no right or wrong, there's only accurate and inaccurate facts, and helpful and unhelpful thoughts and feelings.

Mind you, you may get pushback from friends who feel threatened by your refusal to join in with the moan, because covertly or overtly that's a challenge to their wiring and worldview. When they're raw from a rejection, chocolate and a solid shoulder to cry on are kinder things to offer, but at other times, their writing reality is their business and yours is yours. When it's your writing reality you're re-shaping, why surrender your power to others? You have the right to choose the frames and biases which work best for you.

March 23, 2023

Itchy Bitesized 23: Six Thoughts About Choosing Your Book's Title

A plea by novelist Lisa Medved on Twitter, asking for tips for choosing titles, has got me thinking about what makes a good title, and how you go about finding one. So far I've had very positive responses to the titles of my books (though one kind reader emailed because they were worried that I'd made a big mistake in titling a book with what it isn't). So forgive me if some of the examples are of my own work, because they do offer clues to what's going on.

1) Your title is part of your pitch (join me online at Blue Pencil next Thursday, the 30th, for more on pitches), and if you have a cracker, that's great. But at the submissions stage, having a not-cracker is absolutely not a deal-breaker. My debut novel started life as Shadows in the Glass and everyone said, "Oh, that's a good title", and it was sent out and sold as that. So it was a shock when my editor said to my agent, "I can't tell you how much I hate that title", but we changed it to The Mathematics of Love. And yes, it did feel like renaming a dog you've had for years, but my editor was proved absolutely right. First, everyone including the big buyers was now saying, "Wow, fantastic title!". Next, virtually every review and media mention picked up on the title and commented, made puns, or used it as the opening of the piece: hence my indecent confidence that it is, indeed, a good title.

1) Your title is part of your pitch (join me online at Blue Pencil next Thursday, the 30th, for more on pitches), and if you have a cracker, that's great. But at the submissions stage, having a not-cracker is absolutely not a deal-breaker. My debut novel started life as Shadows in the Glass and everyone said, "Oh, that's a good title", and it was sent out and sold as that. So it was a shock when my editor said to my agent, "I can't tell you how much I hate that title", but we changed it to The Mathematics of Love. And yes, it did feel like renaming a dog you've had for years, but my editor was proved absolutely right. First, everyone including the big buyers was now saying, "Wow, fantastic title!". Next, virtually every review and media mention picked up on the title and commented, made puns, or used it as the opening of the piece: hence my indecent confidence that it is, indeed, a good title.

2) A book title is not a label. Being the most exact description of the contents matters less than getting the potential reader thinking, "Oooh, what's that all about?". Having said that, Four Weddings and a Funeral hasn't suffered from its title; I think of this as the Snakes on a Plane tradition of titles defiantly eschewing mystery or poetry. This is Not a Book About Charles Darwin is an tongue-in-cheek example of the same species.*

3) The crucial "Oooh, what's that all about?" can be stirred up by various means:

Potency. Wedding and funeral are both potent words, of course, and in Jeanette Winterson's Oranges are Not the Only Fruit , oranges is vivid and specific, colour and shape conjured instantly in your mind: it's Showing , if you like. But as competition judge Susannah Rickards pointed out when she guest-blogged for the Itch , oranges works so very well because not the only fruit "activates" the noun. In a title like Lisa Jewell's psychological thriller The Family Upstairs , the words are more everyday, but still potent because they're close to home.

Friction between the words. One of my daughter's most beloved books is Jenny Valentine's Broken Soup : what's that all about? Other examples might include Mohsin Hamid's The Reluctant Fundamentalist , and Jo-Anne Richards's The Innocence of Roast Chicken . And people found friction between mathematics and love, even though that wasn't the point and anyway, in my family the two are not antithetical at all.

Working in an existing tradition, as certain genres have covers to draw in readers who already know and like them. Jennie Valentines' The Double Life of Cassiel Roadnight echoes many others of all kinds of genre (just search for "the secret life of", or "double life of", and the like, on The Online Retailer Who Must Not Be Named). And the rhythm is good too. Dick Francis, like many thriller-writers, often use single words - Straight , Proof, Bonecrack - which mirrors the spare, energy-packed prose, while Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall belongs to a tradition which includes Mansfield Park and Bleak House, but with a different potency, even friction, in wolf.

4) Saying a title aloud shouldn't be difficult. If someone's not sure how to pronounce a word they may be too embarrassed to ask for it, or talk about it, or even have it lying about. Similarly, my original title for my second novel was An Uncertain Alchemy, but to say that aloud even this half-trained actor has to summon up her crispest diction. We toyed with calling it Alchemy, but another book with that title was out there. True, in the UK there's no copyright in titles, but it was aimed at a very similar market and only a few years old, so I thought hard about all the alchemical couples in the story, and came up with A Secret Alchemy.

5) Finding a title may take brainstorming. Your writing mates can help, and here are some other ideas:

Brainstorm on paper, and don't censor as you go: put down everything. However meh or silly or someone-else-has-done-that a title seems, you never know what thought it will lead to next.

Try free-association techniques of the sort that poets use: spider diagrams which jump the tracks of logic and obvious meanings, wake up your metaphor-and-image mind, and engage your rhyme-and-rhythm sense.

Look through the novel for potent phrases. "I would say that the mathematics of love defy arithmetic" comes from a crucial hinge moment, the midpoint of the story, and because they recognise the title in the line, the reader gets a little fizz of extra alertness exactly where I want them to.

Make a list of key words, metaphors and ideas from your novel, then get hold of a good dictionary of quotations and look them up (or try The Poetry Foundation , say; Google will only give you a million versions of a narrow selection). Max Porter's Grief is the Thing With Feathers riffs on Emily Dickinson's poem "Hope is the thing with feathers" (although if you're not riffing, leaving the original word in can be over-explainy ). P D James's Devices and Desires is from the General Confession in the Book of Common Prayer.

Existing phrases and sayings, riffed on, can also work: there's friction in the metaphorical connotations of Bonnie Garmus' Lessons in Chemistry but the denotation is deliberately tin-labelling, while the sting in the tail of John LeCarr��'s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy , is a classic example. Just be very, very careful not to use anything which is still in copyright: Claire Allen's Rainy Days and Tuesdays wasn't Mondays for a reason.

6) Start noticing titles of films and songs as well as books. If it whets your appetite, why, exactly? What are the denotations but also the connotations of the words? How are they working together? If it doesn't whet your appetite, why might a writer and publisher nonetheless have thought it would? But do also bear in mind what my agent said as we were trying to thrash out a title for what wasn't yet A Secret Alchemy: sometimes everyone spends ages trying to come up with a better title, and in the end they come back to the original, just with more faith that it's the best there is.

___________________________

*Indeed, Get Started in Writing Historical Fiction hasn't suffered by doing, I hope, exactly what it says on the tin. Though of course How To books are a bit different; here, the Amazon algorithm is king.

Image by KathrynMaloney from Pixabay

January 31, 2023

Itchy Bitesized 22: Five Steps For Working With Feedback

Whether it's your sibling reading your first-ever story, or a professional review in a national newspaper, feedback is a fact of life for every writer. It's also an essential part of our training and professional development: there's no point in trying to communicate if you don't have a sense of the who/what/why of the receiver. Which is why almost all writers have beta readers of some form: fellow-authors, spouses, ex-coursemates, professional editors.

But that doesn't mean it's always easy to make the best use of feedback: to taked on board and work with everything that will help, and absorb nothing that will harm. And it's even less easy when a painful mixture of hope and fear is making your heart bump as you sit down for the one-to-one, click on the email, or open the magazine. So this is a quick aide-memoire for ways to make the most of feedback. Click through to the Tool-Kit for more extended help with how to give feedback, and how to work with feedback you're given.

1) Notice your first reaction, which probably falls roughly under one of these headings:

"Duh!" = Of course! How did I miss that?

*Sigh* = You���re right, and I half-knew it. I was hoping readers wouldn't notice, but clearly they will.

"Fair enough" = I see why you might feel that, and I'll have a think about whether and how to act on it.

"That isn't relevant" = It���s not that kind of story, it's not your kind of book, you're not the right kind of reader for this stage.

2) Separate out the problems which the reader has found from the solutions they suggest. This sounds obvious, but many feeders-back will express a problem in terms of a solution: they'll say, "I wanted more to happen" when the real problem is that what does happen isn't written grippingly enough: the piece needs re-writing, not more bombs in baby-carriages. Similarly, there are many possible causes for a novel feeling "too long" or "too short", and only one solution involves adjusting the wordcount. Click through to The Fiction Editor's Pharmacopoeia for help in diagnosing and treating the disease at the root.

3) Ask yourself: "Tool, Rule or Fool?" when parsing feedback, and see if it makes a difference to what you do. In other words:

Who is giving this feedback? Do they read enough of this kind of writing for you to trust their experience as usefully representative? If they don't read this genre, are they still saying useful things?

Are they a writer, so they have helpful specialist knowledge and technical know-how about how stories are read and written?

Or are they a writer over-sensitised to particular "rules" such as not moving point-of-view or avoiding adjectives and adverbs , so they base their feedback on whether you've kept or broken those rules? Or, more generally, a person-splaining know-it-all who actually doesn't?

4) Does this reader have power over your writing? Are they a tutor giving you a grade, an examiner, an agent or an editor? Have they already paid for the work, or are you just hoping they will? Are they a tutor trying to help - but who you might eventually need a reference from? Even if you disagree with the feedback, you probably need to be seen to be addressing it.

Some parsing of their response is still in order, and they're still likely to express problems as solutions. Have confidence, though, that finding your different solution to the problem they have very properly raised, should satisfy them - and perhaps better than if you'd gone against your grain by pushing their solution onto your work. Certainly, if they haven't paid you for the writing and you're just hoping they will, you don't have to meekly do a ton of work on the off-chance that they'll offer you a contract - unless you choose to.

5) Ask yourself: "Accept, Adapt, Ignore?" This is my shorthand for the whole process. When the reader points out problems, ask yourself whether you should accept them and act; adapt them - for example by trying a different solution; or simply dismiss them. In the end - even with those who have power - it's your right to write what's right.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

December 12, 2022

New Events To Kick-Start Your Writing in the New Year

If you're hoping to work on your writing in the New Year - whether it's a specific project or a more general feeling that you need more tools, skills and inspiration - then let me help you kick-start your creative development. I've been busy planning new events, from an online evening about Showing and Telling with Blue Pencil, to a whole January learning to Make Your Novel Shine, with RNA Learning. They're all up on my website, and there are more in the pipeline, but here's a taster: it would be lovely to see you online, or in person!

And if you're interested in one-to-one mentoring or tutoring help, click through here to find out more about how I work with individual writers, or get in touch.

***

MAKE YOUR NOVEL SHINE: DEVELOPMENTAL SELF-EDITING FOR FICTION: one month online course

MAKE YOUR NOVEL SHINE: DEVELOPMENTAL SELF-EDITING FOR FICTION: one month online course

Online: Tuesday 3rd January to Tue 31st January 2023

Hosted by RNA Learning

Join me for this one-month online course, hosted by RNA Learning - education arm of the Romantic Novelists��� Association. Whatever genre you write in, self-editing is about a whole lot more than tidying up the sentences. But what should you be looking for when you set out to revise and edit your writing to become the best it can be? How do you set about changing things? And how do you give it that extra polish which will raise it above other novels seeking the same readership?

***

WRITERLY YOGA: WRITING FIT AND FLEXIBLE: online tutorial

WRITERLY YOGA: WRITING FIT AND FLEXIBLE: online tutorial

Online: Thursday 26th January 2023, 6-8pm

Hosted by Blue Pencil Agency

If your language-wrangling skills and experience are limited, your storytelling will always be limited too. It���s the same with the imaginative work: learning to direct and develop your imagination, and knowing when and how to let it go off-track fruitfully, can make a huge difference to the quality of your writing. Join this intereactive, online workshop, to find out more.

***

THE HISTORY QUILL VIRTUAL WRITERS' CONVENTION: keynote presentation and Q&A

THE HISTORY QUILL VIRTUAL WRITERS' CONVENTION: keynote presentation and Q&A

Online: Saturday 4th February 2023, 4-5.30pm GMT, 11-12.30am EST

Hosted by The History Quill historical fiction specialists

The History Quill Online Convention runs 1st-5th February, and Emma is delighted to have been asked to give a keynote presentation on the Saturday. When authors want to take their writing to the next level, there is no better way to do this than by exploring advanced writing techniques. As part of The History Quill���s five-day online convention, Emma���s keynote presentation will discuss techniques which will stretch and challenge authors and encourage them to embrace new ideas, and will include a Q&A. Note that the time for the presentation is 4-5.30pm GMT, and 11-12.30 am EST

***

SHOWING AND TELLING: online tutorial

SHOWING AND TELLING: online tutorial

Online: Thursday 23rd February 2023, 2023, 6-8pm

Hosted by Blue Pencil Agency

Probably, you were first told, ���Show, don���t Tell��� ��� or maybe you know it���s nonsense, but not what to do instead: you just know that what writers mean by these two apparently simple terms has big implications for how effective your writing can be.

***

HOOKS, OPENINGS AND PITCHES: online tutorial

HOOKS, OPENINGS AND PITCHES: online tutorial

Online: Thursday 30th March 2023, 6-8pm

Hosted by Blue Pencil Agency

It���s not only agents and editors who judge a book by the first page: readers do too. In an industry driven by pitches, hooks, blurbs and the first paragraph of Look Inside the Book, writers need to get to grips with how a potential reader would first encounter their novel. Join Emma for this interactive online tutorial.

***

FIRST DRAFT TO FINAL DRAFT: spring away day

FIRST DRAFT TO FINAL DRAFT: spring away day

Kintbury, Berkshire: Saturday 22nd April 2023, 10am-6pm

Hosted by Blue Pencil Agency

Do you get the first draft of a novel or creative non-fiction down fairly easy, but find it hard to move on to the next stage? Does your motivation sag ��� or does your plot ��� when you start revising? In this fully-catered Away Day in a lovely private house, we will explore what a writer needs to do to move on from that first-draft stage without losing touch with the passion that makes you want to write this story.

***

WRITING WITH SCRIVENER: A ROUGH GUIDE: online tutorial

WRITING WITH SCRIVENER: A ROUGH GUIDE: online tutorial

Online: Thursday 25th May, 2023, 6-8pm

Hosted by Blue Pencil Agency

Scrivener software is the writing program most used by professional writers of all kinds to help them structure and plan ��� or erase ��� their drafts, then revise, edit polish and even format and publish book-length projects and scripts. Emma is a working writer who has used Scrivener for Windows for many years; she will help you understand the core principles of how Scrivener works, and support you as you get a feel for how to make it work for your own, individual writing process.

***

SELF-EDITING YOUR NOVEL: six-week online course

SELF-EDITING YOUR NOVEL: six-week online course

Online: four times a year (usually January, March, June and September)

Hosted by Jericho Writers

This course, which Debi Alper and I developed together for Jericho Writers and run four times a year, is sold out for all currently scheduled presentations. New dates will be announced later in the year. Our alumni have gone on to all sorts of achievements: one has sold over a million copies of her fiction, and another has just landed a TV deal; others have simply taken huge pleasure in developing their writing to its maximum potential, and many groups have formed lasting bonds of friendship, for beta-reading and support.

For current courses there is a waiting-list and we do sometimes have drop-outs, so it's worth getting in touch with Jericho. And on every course we have one bursary place available for a writer from an under-represented group. To find out more about the course, click through to Jericho Writers.

November 21, 2022

Itchy Bitesized 21: Three Thoughts About "Breaking the Fourth Wall"

Blog-reader and blogger Mark Harbinger emailed me to say one comment he gets from alpha-readers "is them dinging me for 'breaking the fourth wall'," when he goes for "meta-narration in first person": i.e. a internal narrator, telling a story which includes themselves, who sometimes talked directly to the reader. Paraphrasing his example, you might deliberately choose to open a story like this:

I always say that "Make hay while the sun shines" is only a useful maxim if the sun above you ever does shine. And in my dungeon, it doesn't, and it wasn't shining on that Thursday.

The idea of the "fourth wall" comes originally from the slow evolution of the proscenium arch theatre from the 16th century onwards: the architecture of indoor theatres increasingly separated the humans representing characters-in-action on stage, from the humans who'd come to see the story of those characters being re-created. When cinema arrived, fourth-wall thinking came very naturally, not least because the characters-in-action are not in the same room, thanks to their shadows, the screen creates an illusion that it's a wall beyond which all this is happening. Over centuries, audiences increasingly wanted and expected to feel that they were watching real, individual, one-off events happening before their eyes, and this shift towards realism and naturalism parallelled what had been happening with the novel.

1) Prose narrative is not drama, and a novel is not a film-script. Even if you're sitting in a room with the writer speaking their work, the words themselves are still telling of something that happened elsewhere (and, by definition, at another time: more on past vs present tense here.) However magically the writer's and reader's brains conjure up that other place and time, there is no inbuilt fourth wall to the experience. There is only a (usually silent) negotiation over how much writer and reader acknowledge or ignore the contrast between their shared space, and the otherness of the purely mental story-space. Even in print or recorded audio, there is a reader at the other end of your act of storytelling, and your choice is simply whether you want to acknowledge and work with their existence, or ignore it.

2) Why not let your narrator talk the way storytellers always have? Why not let a character who is narrating their own story talk directly to their audience, not just at them? It���s a much older way to tell a story and it's not surprising that first-person novels are so often formed as memoir or diary: explicit acts of storytelling. It's arguably more natural than the "naturalist" illusion that the main character is talking to themselves and the narrative is just seeping into the reader's brain by osmosis. Of course, we've got so used to the latter we don't think of it that way, but there's still plenty of the former about, for example in commercial women���s fiction, where the tone is so often of the protagonist telling their story to a girlfriend (who, it's implied, is the reader) over a glass of wine. And to whom is Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe saying "There are blondes, and blondes and it is almost a joke word nowadays"*, if not the reader?

3) The key is to do it wholeheartedly, with confidence and consistency, and take care to create the reader you need early on. Together, starting early and doing it with confidence help the reader settle into reading the way this story needs to be read. That's particularly true if you're working by older or different traditions from the current late-20th-early-21st literary creative writing tradition: if there are just one or two instances of addressing the reader - particularly if they're late in the book - it���s more likely (though not inevitable) that the reader will be wrong-footed, jarred out of the stream of the story, feeling abandoned and dissatisfied, and so ultimately unsatisfied.

Click here for the full Itchy Bitesized Series

----------------------------------------------------------

*In The Long Goodbye

Photo of Amsterdam's Path�� Tuschinski Theatre, by Liam McGarry on Unsplash

November 1, 2022

Itchy Bitesized 20: Make it to the NaNoWriMo Finish Line

Today is 1st November, and all round the globe writers of every kind and every degree of experience and talent are embarking on National Novel Writing Month. The general idea - as explained on the NaNoWriMo website - is to spend November writing a novel of 50,000 words. (OK, for most genres that's a bit short, but the whole idea of NaNo is not to get stuck in the nitpicks). The website has articles and blogs full of advice, and forums offering support, fellowship and more advice from fellow-NaNoers. There are places to log your wordcount if that's your thing, and if it is and you make it over the finishing line, you can download a certificate.

I have writing friends who use NaNo, rather as others use #100daysofwriting, as an extra push-cum-support for any kind of writing project, but this post is about the classic NaNo goal of first-drafting a new novel.

1) Remember "don't get it right, get it written". 1,670 words a day (all right, 1,666.66 recurring) really isn't so much, if the only quality standard those words need to meet is that they'll do as placeholders now for the right words later. If a writing evening is two and a half hours, that's less that 670 words an hour. A shade under a minute is plenty of time for thinking up one good-enough-for-now word, I'd say.

1) Remember "don't get it right, get it written". 1,670 words a day (all right, 1,666.66 recurring) really isn't so much, if the only quality standard those words need to meet is that they'll do as placeholders now for the right words later. If a writing evening is two and a half hours, that's less that 670 words an hour. A shade under a minute is plenty of time for thinking up one good-enough-for-now word, I'd say.

2) It doesn't have to be a "good" draft, let alone a good novel, because the value of this approach is to "build up, rather than tearing down", as the website puts it. Tearing bits down and rebuilding them can wait till December, when you know what kind of novel this crazy first draft needs to be. This first draft is what you write for yourself, to find out what the story actually is.

3) Microplanning is your friend even if planning beforehand isn't. This is one of several ideas I've taken from Rachel Aaron's entirely brilliant blog* about how she went from a "mere" 2,000 words a day to 10,000. Microplanning is about working out exactly what happens in just the next few pages, and you can do it while pushing the pram, swimming lengths, waiting for the bus, or in the first five minutes of a writing session. Having worked out the next couple of links in your causally-related chain of events, actually clothing them in good-enough words is relatively quick work.

4) Don't be afraid to go off-piste. Whether it's just that halfway through the evening that you realise the microplan you made while cooking the supper is the wrong ending for the scene, or that on 15th November you realise that your main character's best friend is the real MC of your story, the momentum of writing NaNo-style has a way of leaving space for your intuitive sense of story to speak its truth to you. If that happens, because it's NaNo and you don't want to go into reverse, I'd suggest spending a little time thinking what that means for where the story's headed, making a few notes about what you would need to change in the already-written sections, and then keeping going as if you had actually made those changes.

5) It's only a month. When you've chose to stay in the mode of crazy first drafts and planning by the seat of your pants, it's easier to shut up your mental censor. OK, so the new idea seems silly or the way it's playing out could land you in trouble - but it's only a month. Why not just run with it?

6) It's also only a month's delay on gym sessions, departmental pub crawls, Christmas shopping, highlights growing out, car maintenance and dental check-ups. And ironing, of course.

7) If you're really mired in stuckness, take a writing session or two to try some of my remedies for writer's block.

8) Whatever happens you'll learn something, if only that NaNoWriMo is so not your thing (which at leasts gives you an answer when helpful friends say, "Have you tried NaNo?".). More usefully, you could spend the 1st December journalling about what you've learnt from doing NaNo about

this story

writing this story

storytelling

your writing self

your writing process.

That's a lot of learning. Why not give it a go?

----------------------------------------------

I blogged in more detail about Rachel Aaron's blog here.

Image credit: Public Domain Images at Pixabay

October 10, 2022

Itchy Bitesized 19: How Not To Commit Writerly Adultery

One of the most common difficulties that writers bring to our mentoring meetings is that they find it hard to see a project through to completion, so here are some quick diagnostic pointers which should help you to keep going when you're tempted by the Other Novel - or give you confidence that you really shouldn't.

Of course, the fact that today's writing work on One is boring, effortful and not obviously rewarding is very possibly just business as usual, as it can be in marriage. Most people know that, so it seems to me that there are different kinds of person who are nonetheless drawn to infidelity:

a) the writers who committed outwardly to a relationship (egged on by a society which feeds on stories of "following my passion 110%" and all the rest of the rhetoric), but can't bring themselves to commit inwardly. Adultery is a way of not putting all their emotional eggs in one basket, because that is deeply scary. And of course if, in turn, their commitment to the Other Project, Two, gets too scary, they can always leave it, either returning One, or moving on to their new best happiness, Three.

b) the writers who jumped in and committed to relationships too early out of fear of being alone or of never finding the truly "right" person. A longer, slower courtship might have revealed the flaws in the partnership before the joint mortgage was signed. Sometimes the only thing to do is to admit, with some honest soul-searching, that this is not the right partner for you.

b) the writers who jumped in and committed to relationships too early out of fear of being alone or of never finding the truly "right" person. A longer, slower courtship might have revealed the flaws in the partnership before the joint mortgage was signed. Sometimes the only thing to do is to admit, with some honest soul-searching, that this is not the right partner for you.

c) the writers who "just want to have their cake and eat it". That's a flippant and rather judgemental response: the root of most human emotional complexities is fear, however brutally embodied. And besides, there's no shame in being a Sunday painter or writer who just wants to have creative fun. But, assuming you want to see One through to completion and some form of being read, digging non-judgementally into the desires and fears which are distracting you from that path could be illuminating.

So when you're feeling the lure of that twinkly new project, take a long, hard look at what is sapping your desire to stay with the current project.

1) What desires and fears drove you into the original relationship with One? What needs did it fulfil? What desires and fears are now tugging you away?

2) What unfulfilled writerly needs does the flirtation or affair with Two seem to fulfil?

3) What pleasures does Two offer which you've lost touch with in One?

4) Do any of these tell you about what needs to be different about how you work on One?

5) Has your Inner Critic realised you're about to stop being able to say something is a work-in-progress, flaws and all, and instead send it out into the world with a label which says "This is my best!"? Dodging away from that scary moment to something at a more comfortable stage of life, when you're not so vulnerable; some writers become course junkies for similar reasons.

6) If the two projects are different forms or genres - or even if they aren't - consider if the one or both are just not the right kind for you. The classic example is the natural-born short-story writer who keeps trying to write novels because to the rest of the world that's "real" writing, and might even make some money - but there are other misprisions of this kind.

Remember that no writing project is, actually, a person, and no metaphor drawn from human life is the truth about the writing life, merely a means of evoking what's hard to explain. In writing there is no crime or unkindness in being pragmatic about how your creative self works. Processes which get your needs are far more likely to result in good work that actually finds a home.

So try breaking what needs doing to all your current ideas and projects into clear stages and pieces of work. That way, you can scratch that seven-year itch but not be permanently lured away:

Work-in-progress: frustrating, miserable plot-wrangling and deep doubt

New Thing 1: an afternoon in the library researching and making notes, then back to

WIP: sort out fall-out from plot-wrangling:

NT1: one day on a rough draft try-out little short story for voice.

WIP: line-edit wrinkle-smoothing of those scenes

NT2: browse books which are doing the kind of thing you might do with NT2.

WIP: push on with close-up microscope polishing

And so on. As a bonus, the day away from something often gives you a useful little bit of distance from it, and the new things may get you thinking in useful ways about the WIP, and vice versa.

To keep yourself on track, be very clear, every time, what today's job is. Don't fiddle or get lured away when something occurs to you about another project. Be prepared to calm the fears that you'll forget what you meant if you don't go with the new thing, or that you're wasting time going back to the boring old one, or vice versa. Just make loads of notes, thank the Inner Critic who's so full of dire warnings and then ignore them and recognise that there is no One Perfect Version of anything: the outcome of any writing will always be always contingent on the particular circumstances of its making. Then go back to today's work.

------------------------------------

Image by Gordon Johnson from Pixabay

September 14, 2022

Itchy Bitesized 18: Three Things About Chapters Breaks

I know writers who work in chapters right from their first thinking; I know writers who write their way forwards and just intuit when it's time for a break; I know writers who write (in order, or out of sequence) several drafts before they decide where the breaks go at all; I even know one writer who finds the decisions so impossible they get their editor makes them. This new blog in the Itchy Bitesized series is about how to make best use of chapter-breaks.

1) A CHAPTER-BREAK NEED NOT BE THE END OF A SCENE (unless you want it to be)

There are many ways of getting from one scene to the next, and a chapter break is only one of them. While a chapter-break can naturally create a "jump-cut" to the next scene, you can also exploit the "narrated slide", splitting it across the break so the reader is led comfortably forwards into the next stage of the story.

At heart, the scene is a concept borrowed from theatre: a unit of character-in-action - of story - but not necessarily of storytelling*. You might put more than one scene in a chapter, if together they form an important stage of the story as a whole, or you might split a scene across a chapter-break: many writers do that if they don't want (or don't know how) to move point-of-view, but there are other reasons too.

I suspect that if you did a survey of contemporary commercial fiction, you would come up with an average chapter-length of perhaps 3-7,000 words. On the other hand, when it comes to literary fiction, as in many things all bets are off. But, as with all things word-count related, doing the normal thing just because it's normal is the worst reason for doing it. A good reason is to exploit how readers are accustomed to chapter-breaks working, for your own creative purposes.

2) A CHAPTER BREAK AFFECTS THE READER'S EXPERIENCE:

a) "That's the end of that bit." Many readers feel a chapter break is telling them to turn the light off and go to sleep: that the action or narrative has reached a natural, temporary conclusion. That doesn't mean you have to "finish the scene", as in getting everyone off stage: the dictum "get in late and get out early" applies to chapter-building as much as it does to your novel as a whole. So it's worth checking: once the plot-and-story purpose of the chapter has been achieved, how much more does the reader need?

b) "Now we're going somewhere else." The implication of any visual break is that we've reached a storytelling break. Since stories are made of place and time, it alerts the reader that the next bit will be at another time, and/or in another place. This has two consequences:

i) how are you going to make sure, after the break, that the reader is quickly grounded in the new place and time?

ii) if you break away solely to avoid the reader discovering something that would otherwise be revealed by what the characters do or say next, make sure you don't do it so crudely that the reader feels cheated. To get away with this, make the narrative feel as if it reaches a natural conclusion, so the reader doesn't feel you're artificially withholding things.

c) "Wow! What just happened? What will happen next?" The combination of the break's announcing "that's the end of that bit", and the slightly extended time till the next bit, means that the last phrases and actions of a chapter ring in the reader's mind. Theatre folk call it the curtain-line or the tag-line, comedians the mike-drop. But, again, make sure that the break seems natural, so readers don't sense that the narrative tension is being racked up artificially.

After the break, the opening sentence of the next chapter will also have extra weight and resonance, by virtue of the reader landing on it. But that shouldn't trump its more essential job: quickly anchoring (scroll down) the reader in the new place.

3) YOU CAN EXPLOIT HOW READERS EXPERIENCE CHAPTER-BREAKS

a) In a long event where more than one crucial piece of plot happens - say, a big party where one couple breaks up, another gets together, and a third has a baby - you could use chapter breaks to mark the different phases/scenes. That gives the event some internal structure and scaffolding - a rhythm, if you like - even if the action is pretty much continuous and all the characters interact with each other throughout.

b) The ringing of the last sentence or two over the break, gives it extra emphasis. Which of the last few speeches, actions or images do you want to linger in the reader's mind - perhaps ready to be recalled or echoed later in the story? Those are often the one you want to end the chapter with. Be aware, though, that if you do this too often, with too much of a dramatic drumroll, it can come across as a self-conscious and artificial.

Actually, finishing with "Then she left, and caught the last bus home" can be as effective an ending as "I never want to see you again in my entire life!": if that cry comes three lines earlier, it will rings through the banality of what follows, and the contrast (and longer time till the next chapter starts) will heighten its effect.

c) Thinking like a poet is useful. Grab a good anthology such as one of Bloodaxe's Staying Alive, Being Alive or Being Human, and compare the different effect of end-stopped lines, enjambment, and how each of those plays out even more strongly over the larger break at the end of a stanza. A poem is a journey in miniature; novels are journeys on the grand scale, but they both need the reader to feel the structure, albeit unconsciously. Breaks are crucial to that.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

* If we're being tidy-minded, you could say the hierarchy of units of storytelling from the largest to the smallest goes something like this.

Separate books of e.g. trilogy

Part or "Book" divisions with a book

Chapters

Sections separated off with *** or --- or some such

Sections separated off with a double-line break

Paragraphs

Sentences

Sentence fragments

September 6, 2022

Itchy Bitesized 17: Writing Course or Festival Finished? What Now?

I hope all you lovely Itchy reader-writers have had a good summer (or for my Antipodean readers, winter). I'm just getting my balance again after a mad two months of teaching and talking about writing: first, two different residential courses for Oxford on life-writing, memoir and creative non-fiction, and then two conferences: the Historical Novel Society's in Durham, and Jericho Writers' Festival of Writing in York. And of course there's the four cohorts a year of writers from the course Self-Editing Your Novel.

Every author I know has their story of a turning-point moment: the festival, course or book which opened a door, the workshop or teacher who jumped their writing up a level, the off-hand comment which was the key to the kingdom. And it's moving for a teacher to watch the departing writers, and hope that maybe that's happening for some of them.

But when writers have finished a terrific course, or reeled home from the overload of a big festival stuffed with agents and editors, they can be full of the buzz and the new energy to get going, and still feel overwhelmed. Where to start? What to do first? Which paths to follow? What if different people said entirely opposite things? What if two sets of changes to your project both seem essential but are wholly incompatible? This post in the Itchy Bitesized Series is about the day after you get home.

But when writers have finished a terrific course, or reeled home from the overload of a big festival stuffed with agents and editors, they can be full of the buzz and the new energy to get going, and still feel overwhelmed. Where to start? What to do first? Which paths to follow? What if different people said entirely opposite things? What if two sets of changes to your project both seem essential but are wholly incompatible? This post in the Itchy Bitesized Series is about the day after you get home.

1) Take stock, and take your time.

Never mind (for now) the details of how your MC needs to have more emotional depth or just be different, or that your saggy middle needs bolstering. I'd suggest making a big-picture list of the different kinds of next step, over time, that the festival or course has got you thinking are necessary or would be useful.

That might be revising and editing, or starting something new, or getting input and feedback from others, or engaging with the writing and publishing worlds. Put these under different headings, but mark them with how urgent and/or important (so not the same thing) each is, to fend off the Inner Critic which declares it's all impossible. You know what your headings would be; for what it's worth, mine might be:

this project: what work it still needs; first thoughts about the order it needs them in

other projects: what do you want to do about them?; what could you do now?

developing writing skills and confidence: for the later stages of this project; to enrich and grow future projects

the world out there: friendships and networks in the writing world to support you or bear creative fruit; useful knowledge about and connections to acquire in the industry

And don't be afraid to take your time. Even if an agent or editor has asked to see a full manuscript (yay!), this is where the glacier-time of publishing is your friend. They won't even notice if you take a week or two to send it; if it'll be longer, it's polite (and good policy) to email to say how delighted you are they liked the sound of My Brilliant Novel, and you're just making a few adjustments; you hope that's OK, and it should be with them in X weeks. They'd always rather see an MS that is as good as you can get it than one which you know is still rough, however shiny the diamond it could yet become - and you don't want to use up their attention on things which you're quite capable of improving now.

2) Make a plan of campaign.

If you're drowning in drafts, scenes and beta-reading reports, you may need to start by taming your novel.

If it's reasonably under control, then I suggest you tackle your to-do list in terms of eating an elephant.

If you have feedback you disagree with, or which is contradictory, try digging backwards from the symptoms each reader has described, to diagnose the original problem. Readers will often couch a problem they've found in terms of the solution they would like to see - but the real solution may be quite different.

If you think the work is pretty much ready to go, you could just check over my list of the Ten Line-Edits I Most Often Suggest, in case there's anything on there which could tighten things up even better.

If it's definitely ready, don't forget to check you're presenting it in a form which no agent could be annoyed by.

3) Know how you tick - and make the most of it.

Different kinds of work use different kinds of energy, need different degrees of silence and different amounts of unbroken time; some need an empty house and others a present writing-buddy; some need because-you're-worth-it positivity, and others ruthlessly honest self-scrutiny about how you and this project got to this point.

Of course you still need to push yourself to get on with it even when it's being difficult or discouraging: professional writers know that days like those are just business-as-usual, not an indication that they or the project are useless.

But it's well worth developing ways to make the best use of the human variables of mood and confidence. That's yet another reason for clear to-do lists: if what you planned to do this evening simply isn't possible, or you have an unexpected free morning, then you can change your plans and still use the time.

I hope that helps, and don't forget that there's a lot more on all these topics, and many others, in the Itch of Writing Tool-Kit. For more about what I offer groups, organisations and individual writers, click through to Teaching and Talking, and for more about where I'm teaching in the next few months, click through to Events.

Good luck!

Photo by Luke Stackpoole on Unsplash