Laura Kalpakian's Blog

January 19, 2024

A Son Of This House: Sean Meyer 1982—2024

But as a boy, through elementary, middle and into high school Sean Meyer was so often present here with us that, like the other sons of this house, Bear and Brendan McCreary, his laughter and his gifts melded into ours. He is present in photos of Christmas and New Years and Thanksgivings, the Elvis parties, family celebrations and birthdays for many years. More poignantly, he was present on those days so ordinary they are mulched into memory, woven, almost unseen, into the fabric of a collective childhood

Sean Meyer and Brendan McCreary met at Parkview School, at about age eight or nine. They played together on the basketball team where both were hapless. But they discovered shared enthusiasms, music, movies, action figures, games in which they wove elaborate stories for their own ongoing delight as boys, and then as teens. They created around them a core of friendships still strong and extant to this day.

The high school equivalent of Ben Hur.

Music and movies were lifeblood to Sean Meyer. One of my favorite memories of him and Brendan and Tyler Swank was the making of “Le Maître de la Bête Sauvage” (Or roughly, The Master of the Terrible Beast.) Its origins were modest, an assignment for their high school French class. Whatever the actual assignment was, in their creative hands it became an extravagant twenty minute film, the high school equivalent of Ben Hur. The script was written by Brendan and Sean, and then translated into French by Greg Finnigan (whose study habits exceeded theirs and who was doing much better in French than either Sean or Brendan). I do not remember the story, but “Le Maître de la Bête Sauvage” required a cast of well, not thousands, but perhaps twenty people, along with extras. Sean directed. The film crew included camera personnel, security (with badges) caterer (moi), costumers, sword fight instructors, stunt people, custom-made dummies falling from trees in the park, deathless dialogue (all spoken in French even by those actors who were not in French class). In the last scene Tyler, wearing a clown wig and a woman’s dress (one of mine, I’m told) is being chased down the street by a car with a crazy driver. The French teacher, needless to say, was dumbfounded. Sean did the final edits, and to my knowledge, had the only copy.

Even after high school, Sean remained part of my immediate life. He went to LA with me to visit Bear and Brendan at USC, to have Thanksgiving at my sister’s in Riverside, California, to hang out at the Boingo Cover Band gigs in Anaheim. Here at home, he and Tyler Swank, Anna Mortimer, Phil Swenson, Shaun Johnson twice yearly performed the Geranium Exodus, bringing the potted geraniums into the house in October, taking them out in April. And for years, once a month or so, we would all get together at my house for dinner and a movie, usually an action movie or a classic Western, especially when I was researching the novel, American Cookery. He was a good friend to me, a support and a ballast in various emergencies, including, most dramatically, the basement flooding in 2010. He was one of the pallbearers at my father’s funeral in 2012. He outlived my 101year old mother by only three weeks.

For the rest of his life he shared his gifts with his hometown.

After a stint at the Evergreen State College, Sean moved to LA, studying guitar at the Musician’s Institute. There he had a number of musical adventures, including playing guitar for artists recording with Wind Up Records, and Geffen Records and touring with these labels around the US and Europe.

But his heart was always here, in Bellingham. He returned to this city where for the rest of his life he shared his gifts and enthusiasms. He played in many bands, Bowie and Queen tribute bands, country (and western) bands, punk bands, rock bands, and my personal favorite for a title, Guillotine Eyes. At one time he told me he was playing and recording with six different local bands at the same time. He taught guitar for years to students of all ages. He worked for a long time at Harris Street Music store (which was not on Harris Street) and every year on his birthday, October 30th, I brought cake and a card to the store.

But his heart was always here, in Bellingham. He returned to this city where for the rest of his life he shared his gifts and enthusiasms. He played in many bands, Bowie and Queen tribute bands, country (and western) bands, punk bands, rock bands, and my personal favorite for a title, Guillotine Eyes. At one time he told me he was playing and recording with six different local bands at the same time. He taught guitar for years to students of all ages. He worked for a long time at Harris Street Music store (which was not on Harris Street) and every year on his birthday, October 30th, I brought cake and a card to the store.

But there are whole vast tracts of Sean’s life in which I had no part, no knowledge. I can only guess at his complex inner and emotional life. I believe he masked his pain. He was fortunate, late in his short life, to find Julia Skerry who brought him joy and gave him strength. These last few years, I saw him only infrequently, especially after he left the music store, Covid intervened and my mother’s heart attack in 2021.

In October 2023 Brendan called me and asked me to sit down, that he had some bad news. He said that Sean and Julia had called to say that Sean’s body was riddled with cancerous tumors. I remembered then that Sean’s own father had died of cancer when Sean was just three years old. He would have been just Sean’s age. Sobering.

He insisted we see it as a demanding moment.

With this news, like everyone else eager to help, I splashed into action, part of the bucket brigade, contributing money to a fund, signing up for Meal Train, anything that would help Sean and Julia through this demanding moment. And that was how he insisted we see it: a demanding moment, not the end. He remained steadfastly upbeat about his treatment and his chances. I last met with him and Julia delivering a lasagna dinner to them. I last heard from him personally in December when he emailed a request for my recipe for French toast. On the afternoon of January 3rd 2024 Julia set up a Facetime call from the hospital so Brendan and I could talk to him, words that seemed to me so utterly inadequate, necessary yes, not useless certainly but unequal to what we wanted him to know. He died on January 4th.

Trailer Wars! The Bellingham equivalent of Cinema Paradiso.

What I am writing here does not aspire to obituary. That takes in the whole life. I did not know his whole life. Rather, I want to laud the gifts Sean so generously gave. He ought to have been better recognized while he lived, but at least I can record here that for nearly ten years Sean Meyer gave to his hometown, Bellingham, the equivalent of the experience chronicled in that wonderful Italian film, Cinema Paradiso where the whole community comes to the theatre, not simply to watch, but to bond. He created Trailer Wars and these evenings were wildly popular, great choral, communal moments of enthusiasm, laughter, competition and camaraderie.

What I am writing here does not aspire to obituary. That takes in the whole life. I did not know his whole life. Rather, I want to laud the gifts Sean so generously gave. He ought to have been better recognized while he lived, but at least I can record here that for nearly ten years Sean Meyer gave to his hometown, Bellingham, the equivalent of the experience chronicled in that wonderful Italian film, Cinema Paradiso where the whole community comes to the theatre, not simply to watch, but to bond. He created Trailer Wars and these evenings were wildly popular, great choral, communal moments of enthusiasm, laughter, competition and camaraderie.

I was part of the very first audience who crowded our butts together, December 2008, on the couch of the place Sean was living at the time (older folks on the couch, younger ones sitting on the floor). I don’t remember the short films we watched, but it was the first of what would become a monthly civic film festival.

Trailer Wars offered community and encouraged expression.

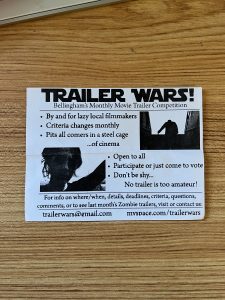

Sean and a number of close compatriots, Chris Patton, Tyler Swank, Anna Mortimer were the core, founding group. Beginning in April 2009 They invited anyone to make five minute trailers. (Time limit was later changed to three minutes, for the sheer volume of entries.) The invitation read:

Trailer Wars!

Bellingham’s Monthly Movie Competition

By and for lazy local filmmakers

Pits all comers in a steel cage–of cinema

Open to All. Come to participate or just to vote.

Don’t be shy. No trailer is too amateur.

The audience for Trailer Wars quickly outgrew the couch. Sean and the Trailer Wars core crew prevailed upon (what was then the Pickford, later the Limelight) art house cinema to show the films. Soon they reached out to local businesses for endorsements, supporting ads, product placement, engaging the town’s commercial community. Trailer Wars not only invited the participation of would-be, wannabe, or might-yet-become filmmakers, but the Trailer Wars core group lent their expertise—and their equipment—to participants, teaching the basics of film-making, basically, informal education. Trailer Wars was an inclusive, creative, civic enterprise. In short, it offered community and encouraged expression.

The audience for Trailer Wars quickly outgrew the couch. Sean and the Trailer Wars core crew prevailed upon (what was then the Pickford, later the Limelight) art house cinema to show the films. Soon they reached out to local businesses for endorsements, supporting ads, product placement, engaging the town’s commercial community. Trailer Wars not only invited the participation of would-be, wannabe, or might-yet-become filmmakers, but the Trailer Wars core group lent their expertise—and their equipment—to participants, teaching the basics of film-making, basically, informal education. Trailer Wars was an inclusive, creative, civic enterprise. In short, it offered community and encouraged expression.

Winners got to keep the Trailer Wars Crown for a month

Once a month Trailer Wars brought scads of people into the theatre on otherwise dull weeknights. Admission was probably five dollars. Tee shirts were later sold for ten bucks. Trailer Wars nights were always sold out, standing room only. Sometimes the small theatre was so crowded people were sitting on the floor in the aisles. Indeed, on one occasion, if memory serves, someone called the fire department, and they intervened saying that blocked aisles were against the city’s codes.

In many ways Trailer Wars was a throwback to those long-ago, fabled days of the Saturday matinees when the main feature was preceded by a serial. Trailer Wars’ serial was Baycove Terrace, a high spirited, goofy-spoofy soap opera, filmed locally and propelled by the many talents of Sean Meyer, Chris Patton, Tyler Swank, Ryan Covington, Anna Mortimer and others. After the installment of Baycove Terrace the various trailers were shown, just as they had been submitted, without edit or censure.

Participants always brought their posses to the Pickford to cheer. These noisy supporters sometimes reminded me of the theatres in 19th century Paris where the actors and the playwright would import their own cheering sections, known, in French as claques, to the theatre to drown out the jeers of their antagonists who also brought their own heckling claques. Unlike 19th century Paris, the Pickford never erupted in fights, but there was always cheering, and muttering, occasionally shouts. After the trailers were shown, paper ballots were passed out with the names of the trailers and the audience voted for the best trailer. The group with the biggest posse often won.

The winners got to keep the Trailer Wars Crown for a whole month. They also got to choose the genre for the next month (mystery, musical, noir, Western, zombie etc). They were disqualified from winning the following month.

I Did It For Love

The trailers were, clearly, not all of equal quality. But some were little gems. In terms of narrative strength, filming, continuity, many were, honestly, superior to the many student films I saw at USC (made by filmmakers with access to high grade equipment and technology). My favorite of all the Trailer Wars films was, I Did It For Love, much of which was shot at my house in December 2009. After the holidays, I was cleaning up, and I found the shooting script in Sean’s own hand. I put it in a folder and it stayed in a file cabinet until I began to write this remembrance. I read it and wept.

I Did It For Love told the story of an Irish family, particularly a father-son conflict over music. It was directed and filmed by Sean Meyer, and written by him and Brendan, both men who had grown up without fathers present. It starred Brendan McCreary, Tyler Swank, Anna Mortimer with a supporting cast of Bear McCreary and Raya Yarbrough, Phil Swenson, all of them affecting Irish accents.

A three minute film, it was beautifully dramatically economical. It had humor and pathos. When I saw the final, finished, in the theatre, I got all misty though I had seen its various parts in bits and pieces in the making. It had a lovely, lilting theme song with whimsical lyrics written and sung by Brendan with Anna chiming in at the end. In part the lyrics to “I Did It For Love” read:

If you were lost, no matter the cost, I’d find you

And always ask what I did it for

(I did it for love)…

I would sleep for a thousand years

I would cry ten thousand tears

I would sing a million songs

(What for? What for? What for?

I did it for love)

I would climb the highest peak

I would brave the cold and heat

(What for? What for? What for?

I did it for love)

I would bring you breakfast in bed

If you were sick, I would pay for your meds

(What for? What for? What for?

I did it for love)

I’ll be with you until the end

And always ask what I did it for.

I did it for love.

Brendan and Bear and I were not there at the end with Sean. We were all three in Los Angeles. But many others were at his side; he knew he was loved. Fittingly, the Trailer Wars crown was in his hospital room.

When the call came on the morning of January 5th, I sat with the phone in my hand, staring out the hotel window watching the 405 freeway, all those automotive corpuscles speeding up and down the concrete veins, and all the little lives within, everyone on their way to destinations, none of them knowing what I—what we—had lost. A son of this house. Sinéad O’Connor’s plaintive ballad, “This is to Mother You,” played in my head.

I never dreamed I would say goodbye with no hope of hello.

I Did It For Love can be found

https://youtu.be/utyDkxy9pcQ?si=4yftmrb5bnYyWPse

Other Trailer Wars can also still be found on You Tube.

The post A Son Of This House: Sean Meyer 1982—2024 appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

December 7, 2023

Patsy Cline in Her Own Words

Patsy Cline In Her Own Words is an important contribution to mid-century American culture, and the life of an icon. This is a beautifully presented collection of letters Patsy Cline wrote to Treva Miller, her very first fan club president. Patsy and Treva were allies in forwarding the singer’s career, but they were confidantes as well. It is a book awash in hope, dreams, enthusiasm, romance and tragedy.

They met in 1955, young women from modest backgrounds. Seventeen year old Treva lived with her widowed mother and aunt in tiny Telford, Tennessee. Patsy’s father had deserted their family, and she had been raised by her mother in Winchester, Virginia. Twenty-three in 1955, Patsy had married young, but she had been performing seriously since she was fifteen.

She believed in Patsy from the beginning

That summer of 1955 Treva went to county fair to hear the Louvin Brothers, well known gospel singers. Patsy Cline was also performing. After the performance Treva sought Patsy out and asked for an autograph and to join her fan club. Patsy didn’t have one. Treva volunteered on the spot to start one, to be the president. These four years of letters testify to their growing friendship.

Decades later Patsy Cline’s letters to Treva were found in a jewelry box. Cindy Hazen and Mike Freeman bought them at auction and put them into a book originally published in 1999, and now, happily reprinted by Sartoris Literary. In addition to the printed letters (and many photographs) the editors have included copies of the actual artifacts, giving the book a much more intimate feel.

“I’m just as happy as if I had sense.”

Seeing Patsy’s rounded handwriting, on these often hurried notes, her occasional misspellings, we can imagine her long hours on the road between gigs, toiling in the studio and the demands of radio and early television, performances on Town and Country Jamboree and The Arthur Godfrey Show. We get the flavor of her habitual expressions, my favorite being, “I’m just as happy as if I had sense.” We see the breakup of her brief marriage to Gerald Cline in her own succinct, emphatic words: “He told me if I was gonna sing, I wasn’t going to live with him. So I’m back home.” We see Patsy falling in love again, re-marrying and becoming a mother.

Treva’s efforts on Patsy’s behalf drew her into a world beyond Telford, Tennessee. As the Patsy Cline Fan Club president Treva reached out to a young DJ and country music enthusiast, Bruce Steinbicker; he was happy to help promote Patsy’s music. Bruce and Treva fell in love and married. So these four years were youthful, active, energetic times for both Patsy and Treva. Their lives were enhanced by, and engaged with one another.

Treva Miller vanished into oblivion.

Though we do not have Treva’s letters to Patsy, it’s possible to imagine the contours of her life. While Patsy was continually on the road, performing and recording, television, and radio and county fairs, Treva was typing up the fan club newsletter at the kitchen table. (And one wonders if she had to teach herself to type, if she had to buy a second hand typewriter.) She maintained and constantly added to long sheets of names, addressing each newsletter by hand. Patsy and Treva both worried over the costs of postage and supplies. Patsy sent money whenever she could to support these efforts; when she couldn’t, she felt badly and Treva paid for these things. One wonders if Treva’s work met with resistance from her mother and her aunt. Even if they opposed her efforts, Treva persisted as fan club president and good friend to Patsy. And then, in September 1960, riding with her young husband, their car was struck by a drunk driver and twenty-two year old Treva was killed instantly. We have no record of what Patsy felt when she heard this news, but these letters testify that she would have been heartbroken.

Reading this reissue, I find my reactions are very different from 1999

Patsy Cline went on to establish herself as one of the sterling voices of American music. Treva Miller vanished into oblivion. Reading this reissue of Patsy’s letters, I find my reactions are quite different from my responses to the original book. Then, I was mostly struck by the emotional connection between these two young women, and that intimacy still bubbles up off the pages.

But now, twenty-plus years later, I am also struck with how Treva and Patsy worked together on what was basically social media. And what a lot of work it was! Done not by glossy high-priced PR people but two small town women dedicated to one cause.

Treva put out an almost monthly newsletter, painstakingly keeping fans up on Patsy’s various appearances so they would know where and when they could see her perform. Neither of them had any kind of background in publicity, and yet that’s exactly what they were doing. When producers wanted to put Patsy in evening gowns (she had always worn the cowgirl outfits handmade by her mother) she consults with Treva about what such a change might mean to her image, her career.

Fan club newsletters created necessary bonds.

Amid the incessant welter of information in the 2020’s (and unless you are going to unplug from the universe and sit on a rock in Scotland) it’s hard to imagine the crucial function of these many fan clubs for performers in the past. The newsletters created necessary links, not simply for the performer and the fans, but for the fans to connect with one another, to share their stories and enthusiasms. To bond. Not perhaps Taylor Swift mania, but basically the same work.

Patsy Cline absorbed all these disappointments and still pressed on.

Re-reading the book now, I also responded more vividly to the many hopes, possibilities, plans that Patsy wrote of so eagerly and with such enthusiasm….that never came to pass. Died, or dried up, or simply never came to fruition. The editors have provided informative, well-placed sidebar contexts, quick descriptions of people and events that Patsy mentions, and so the reader is struck with the immediate contrast: Patsy looking forward to a possible tour in Asia, for instance, and the sidebar info that this prospect not only didn’t materialize, but was never heard of again. Or how working with a well known producer had not brought the recognition Patsy had hoped for. Patsy Cline absorbed all these many disappointments and yet, pressed relentlessly on professionally.

Patsy Cline died in a plane crash in 1963, thirty years old, leaving a grieving mother, a heartbroken husband and two small children, leaving as well an indelible body of work. Treva Miller did not live to see Patsy become the icon whose voice remains vivid and immediately recognizable sixty years after her death, but she would not have been surprised. From the time she stood amid the audience at the dusty county fair, Treva knew she had heard something unique. She believed in Patsy from the beginning.

—–

Patsy Cline in Her Own Words is available in paperback December 1, 2023

The post Patsy Cline in Her Own Words appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

August 14, 2023

A BOOK AND ITS COVER

“Writing a book, seeing it published, why that must be the most wonderful feeling in the whole world. To hold it in your hand, a book that began just as an idea in your imagination!” says a character in one of my novels. Writing a book is a (pretty much) solitary undertaking, but producing a book, “holding it in your hand,” that is a collective enterprise, pulling the author into myriad relationships, some more intense than others.

Naturally, there’s the editor (and no doubt her assistant) with whom the author has many dealings over many months. Trotting right behind in the process is the copyeditor. This person will question your punctuation, yes, but also ought to make sure that your references are correct. (Did Triscuits exist in the era in which you are feeding them to your characters?) I have learned the proverbial hard way that the author needs to alert the copyeditor as to the novel’s narrative quirks beforehand. Otherwise there’s a lot of confusion, and occasionally a lot of hard feelings. (On the other hand, I do have to admit I have more than once thanked the copyeditor for her alerts.) The proofreader then takes up your book. The author’s relationship with the proofer is simpler.

When it is suddenly over, it feels like a summer fling in September, ciao, amore.

Months before publication the publicist and the marketing people jump into the fray. In that intense moment—flurries of emails and phone calls, possibilities abounding—the author’s life will be intimately entwined with these individuals, all equally enthusiastic, committed to the glorious prospects for this wonderful book! But, alas, this is not so. The relationship ends, suddenly it seems to the author, and when it is over, it’s ciao amore, like a summer fling amid September’s fallen leaves.

What of all the other hands and eyes, talents and skills contributing?

There are other people who clothe the author’s words in print and paper and send those words out to meet the world. The book designer, the typesetter, the jacket designer and creator of the jacket art. The author is deeply indebted to these unseen contributors, but she has no contact with them. Their names are discreetly tucked on the publication page.

But what of all the other hands and eyes, talents and skills contributing? I’ve read that one of the Big Five publishers has started listing their names at the back of their books, production assistants, everyone who, literally, had a hand in creating the artifact. I applaud this choice and hope other publishers will follow suit. These contributors should be noted, acknowledged just like they are in films. (I always sit through the whole long list of ending credits until the lights come up and it’s just me and the guy sweeping up popcorn in the theatre.)

“I like it very much.” Or, “I like it very much.”

The second-to-last step in the evolution of the artifact is the dust jacket. The editor will send the author a “proof” of the dust jacket. To this the author can reply one of two ways.

“I like it very much.”

Or

“I like it very much.”

Of all the many books I have published, there have been several dust jackets that I did indeed like very much. However, I only loved two of them, both were long ago and both by the same artist, Wendell Minor, who managed to evoke character and thematic canopy with his artistic rendering.

What could I say? Could I whine that Roxanne Granville wasn’t that skinny?

Mostly, publishers’ decisions about jacket art have left me baffled. For The Great Pretenders (Berkley, 2019) I was surprised to see Roxanne Granville, the central character, wearing an enormous sunhat, a yellow sundress and long black gloves, staring skyward, standing beside a fat-fendered 1950’s Cadillac in front of a line of tall palms with a generic cityscape in the background. This woman did not look like the Roxanne I imagined or described. There was no yellow dress in the book. Roxanne drove a smart little British sportscar, an MGT, not this big behemoth. The palms look more like Florida palms than bushy California palms.

“I like it very much.” I wrote to the editor.

I understood the fat-fendered Caddy, though I was surprised to see what looks like a parking ticket on the window. (The Great Pretenders is a Hollywood novel of the Blacklist era, the Fifties. Clearly, they wanted the jacket art to reflect that era. As for the figure not looking like my character. Could I whine that Roxanne Granville wasn’t that skinny? Could I inquire why she was looking skyward, perhaps to a flock of Canadian geese overhead? I could not. In the last draft of the novel, I put her in a yellow sundress (though yellow would not have been her color) and I did not include long black gloves, thank you.

I protested the cityscape.

But the more I thought on it, the generic cityscape made me bristle. I’m native to Los Angeles, my earliest memories are rooted there, and the sprawling city itself is important to the novel. I protested. I wrote to the editor again. “I like it very much,” I began, but I objected to the cityscape. At the very least, why not include the iconic LA City Hall? (Recognizable by anyone who has ever seen a television series set in LA.) I won that round, happy that my authorial input was acknowledged, maybe even respected. Oh, and no parking ticket for her.

I’m not even sure what I envisioned. It’s a handbook for writers.

The jacket art for nonfiction, I learned, is an entirely different process. For nonfiction there’s no central character, no particular era or overall thematic canopy that can be evoked in a visual image. When the editor sent me the jacket proof for Memory Into Memoir, (2021, University of New Mexico Press) I wrote back, “I like it very much,” though in truth it looked nothing at all like what I had envisioned. I’m not even sure what I had envisioned. Memory Into Memoir is a handbook for writers.

“Pen in hand” is a nostalgic image, perhaps even metaphorical.

What I envisioned was, oddly, more like the recent proof I received for jacket for the Chinese edition of Memory Into Memoir. I like it very much. I like the bright, the vibrant red. I like the wistful picture of a woman alone with a pen in her hand facing an open window and a setting sun. It’s thoughtful, even tranquil (though I know very well that writing a memoir is not a tranquil experience, quite the opposite). The writer in this gauzy scene appeals to me. I like the little drawing on the back, the disembodied hand, again, pen in hand, writing in an actual notebook. I like it because “pen in hand” is itself a nostalgic image, perhaps, now, even so passé as to be metaphorical.

I have zero idea what the writing on this dust jacket says. I have sent it on to my adventurous cousin, Patty Stephenson who has lived and taught in China. She can speak Chinese, and though I don’t know if she can read it, she knows a lot of people in China and they can read it. She will get back to me with their findings. Stay tuned.

The post A BOOK AND ITS COVER appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

July 19, 2023

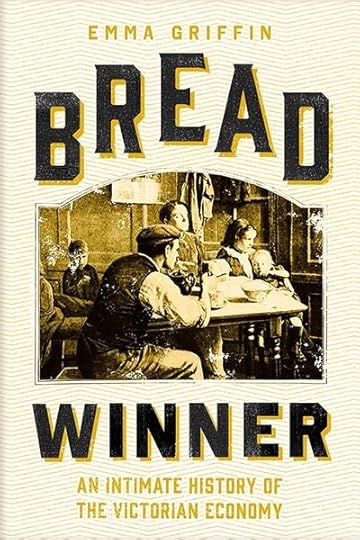

Bread Winner

So, no surprise, I had [have] no interred in economics with its endless tables and bewildering acronyms. However, I was enthralled by Bread Winner: an Intimate History of the Victorian Economy by British historian, Emma Griffin. Ms Griffin is not content with the usual nattering about GNP and wages rising or falling etc. “Working class voices can shed light on large economic questions as well.” Indeed they can. Bread Winner asks the truly pertinent questions if we are to understand the past. Where did those wages go? Who spent them and how? How did the people earning those wages actually live? And though men were usually the ones earning the wages, Ms. Griffin turns her primary scrutiny to the women and children, the family. The book makes clear that even if, as the economists tell us, wages rose, the standard of living for actual people did not.

Her scope is both vast and deep.

Griffin’s sources for these families are some 662 autobiographies of working class people. Some are actually published, but most she exhumed from archives, libraries, obscure collections in record offices, heritage centers all over England. The work that she (and presumably her team) put into reading, assessing the experiences of so many disparate lives, truly boggles the mind. “Bread Winner picks up themes that historians have long wrestled with. But if the problem is old, the method I have pursued here is not.” True. Yes, there is a goodly amount of statistical processing (“twenty percent of these autobiographies reported…” and so on). But Griffin seeks to understand these lives, not simply codify deprivation. Bread Winner is rich with insight, alight with compassion for working class life in England.

The author delves deep into the particulars of ordinary people who lived through these events, and from those accounts derives universal observations about life in Victorian and Edwardian England. (The book ranges from about 1835 to about 1914.) Her scope is both vast and deep.

Domestic violence was rife, almost expected, evaded when possible, borne when not.

Overall, she describes a society in which working class women were kept penurious by virtue of being uneducated. Thus, any work women could do was unskilled and poorly paid—if it was paid at all. Many girls did not go to school, but were kept at home, unpaid drudges caring for younger siblings, and helping with housework. Without any possibility of income, women were also denied any possibility of independence. Those who did work outside the home could only be domestic servants, doing the same tasks for poor wages.

When these girls married, as most did, they found that motherhood usually followed swiftly upon marriage. They and the children who lived were dependent on their men. If those men squandered their wages on drink (the role of alcoholism is a terrible constant in these lives) or gaming, the families had no recourse, and no other resources. Alcohol also exacerbated domestic violence which was rife, almost expected, evaded when possible, borne when not. Still, most women stayed with their men. If the husband/father deserted the family altogether, the depths of destitution can hardly be imagined. And if a woman managed to free herself from an abusive husband, she had to wait until her sons could join the workforce, at the age of thirteen or fourteen when typically, education ended even for the boys.

Men were gifted with entitlements denied to the women and children.

In digesting and assessing these autobiographies, Ms Griffin found that being the breadwinner gifted men with entitlements denied to the women and children. He would get the best of the family’s food (an egg, or fish, or even a bit of meat, say while the rest of them ate bread and margarine or drippings). Being the breadwinner also entitled the man to retaining a share of those wages for his sole amusement, a few hours at the pub, say, or sporting clubs. Additionally, he could claim a certain amount leisure time, apart from the family, to enjoy those amusements. Certainly the husband/father was spared any sort of housekeeping responsibilities. Once the boys went out to work, and began to bring home pay, they too were spared the endless drudgery of housework.

Bread Winner: An Intimate History of the Victorian Economy by Emma Griffin, Yale University Press, 2020

All that thankless grind fell on the wife and the children. Ms. Griffin shows vividly just how arduous housework was, maintaining fires for cooking if not for heat, making bead, conserving bits of meat or fish, thinning soups. In urban areas there were myriad little shops where food already prepared could be bought, lightening the cooking burdens for some, even if the food did not improve their diets. Access to water and infestations of vermin were part of everyday housekeeping rituals, to say nothing of the ongoing woes, dirt and diseases spawned by poor sanitation.

These are stories of women and children, left destitute, dirty, barefoot, and barely educated. Children reduced to picking through the garbage in gutters looking for food. Children’s shoes routinely pawned on Monday, redeemed on Saturday. As the reader comes upon the same names, the stories seem to deepen. We develop empathy for these writers, as one would for characters in a novel. We are alert to the poignancy in their narratives, though it is mostly unstated, camouflaged under forthright, unembellished, unimpassioned prose.

Ms. Griffin treads into a whole new kind of history

In the last section, “Life” Ms. Griffin treads boldly into a whole new kind of history. She inquires into the emotional life portrayed in these narratives. What constituted a happy home? A good mother? A good father? She finds that a different set of standards prevailed 150 years ago than the ones we use now, bearing out the oft-quoted, “The past is a foreign country, they do things differently there.”

Griffin gives readers the wherewithal to imagine

At the end Ms. Griffin explores how working class women edged their way toward citizenship, that is, participation in life outside the confines of the family. Not surprisingly for many impoverished women, the suffrage movement gave them the tentative chance to emerge from narrow domestic spheres. Women banded together in various ways, and in doing so offered each other solidarity even though suffragettes were reviled by society in general and men in particular.

And then came the Great War, four years of military misery, incompetence and death. When in 1914 their men marched off (many of them never to return) women stepped out of their hovels and into the factories and workplaces. Bread Winner is a wonderful book, not simply for its depth and scope, but because Griffin gives readers the wherewithal to imagine what those pay envelopes must have felt like, once placed into these women’s hands. The clink of a few coins, prelude to the possibility of independence. Their lives would never be the same.

The post Bread Winner appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

July 14, 2023

THE LAND OF LUCKY STRIKE

One hundred years ago, 1923, the Kalpakians left Constantinople, bound for America. Their immigration was sponsored by members of my grandmother’s family, people who had emigrated years before and had established themselves in Southern California. In the Kalpakians headlong, single-minded haste to become Americans, they jettisoned their old country past and their struggles as new immigrants, consigned all that to oblivion save for three particular anecdotes.

These three stories are funny and charming. But they masked what must have been an ocean of anguish, of pain I never guessed at until—among my earliest endeavors as a writer—I tried to take those three anecdotes and render them into shapely fiction. From one of them, the Dumbbell Story, I created “The Land of Lucky Strike,” first published in Fair Augusto.

Lucky Strike? Chesterfield? Juicy Fruit?

Once arrived in Southern California, Harry Kalpakian had to get a job and swiftly. However, he spoke no English. In the old country Turkish was the only language allowed on the street or for commerce. Armenian would have been his home-language, the language of intimacy. He had as well a smattering of Arabic, and Greek. (Keep in mind, none of these uses the English alphabet.) My grandmother, on the other hand, learned English when she was educated in an American Protestant school in the city of Adana, Turkey. Helen’s schoolgirl English would have been useful in the immigration process, but it was no help now to Harry who had to support his family while she stayed at home with two little girls, my mother, Peggy, a toddler, Angagh, age four, and a third daughter born in January 1924.

The Dumbell Story

Sometime in 1924, Harry Kalpakian went to work for Helen’s older brother, Art Clark (his old country mouthful-of-a-name neatly Anglicized). Art owned a string of cigar stands near the Pickering Pleasure Pier. No doubt Helen coached her husband with Cigarette? Cigar? Candy? Thank you! Sufficient English, easily augmented with a smile, and hand gestures, pointing to the logos, Lucky Strike? Chesterfield? Juicy Fruit?

The Dumbell Story is based on the following incident: A young flapper came by the cigar stand. She did not want cigarettes or candy; all she wanted was change for a dollar. Harry had no idea what she meant. Cigarette? Cigar? Candy? Thank you! was all he could repeatedly say, pointing to his various wares. This girl was disgusted, and before she sauntered off, she sniffed, “Dumbell.” Harry came home and asked Helen, “What means dumbbell?” But her proper schoolgirl English was not equal to slang. Finally Art had to tell them dumbbell meant stupid. Everyone had a good laugh over this. Indeed everyone had a good laugh over this for generations.

I tried to imaginatively enter into my grandfather’s life and mind

When I went to shape The Dumbbell Story into “The Land of Lucky Strike,” I tried to imaginatively enter into my grandfather’s life and mind. I asked questions. Big Picture questions: How would the pace, the light and noise, the sensations of 1920’s Southern California have affected him as a new arrival? Detail questions: How would he have navigated the commute to the beach? I set the story at Christmastime to make the new customs even more bewildering. The inner turmoil I imagined for my grandfather was that of a foreigner adjusting to American life, that is, face forward to the future.

I never asked myself what he might have lost from the past

On re-reading “The Land of Lucky Strike” for the new Paint Creek Press edition of Fair Augusto, I was suddenly struck by the questions I did not ask: what might Harry Kalpakian have lost from the past? Harry, unlike his wife, lost his language, his religion, and his family. Helen’s surviving family was together in Southern California. She had been brought up Protestant. She spoke English.

When Angagh’s kindergarten teacher came to their home and told them their daughter was falling behind at school, husband and wife made a pact: at home they would only speak English, no Armenian, no Turkish. English alone. No doubt this stringent measure helped Harry to learn more swiftly, but he must surely have felt the loss of Armenian, the language traditionally spoken in all the homes he had ever known. Over time Harry’s English came to be good, but his speech always remained heavily inflected. Growing up, I never even wondered why my grandmother’s English was flawless and without accent, and his was not.

[image error]Harry’s family dispersed into the diaspora in 1921; he never saw any of them again.

Harry Kalpakian , c. 1950 Olympic Blvd.

My grandparents married in 1917 in Adana, Turkey. Harry’s people, merchants, and bankers, were not especially happy that he had wed a penniless orphan, however well educated she was. A formal portrait of the young couple standing on either side of Harry’s mother fairly bristles with the implication of Trouble to Come. And it did.

Given Armenian tradition (and the perils of wartime and even being Armenian in a Turkish city in 1917) the bride and groom went to live with the groom’s family. Three generations, thirteen people lived under one roof. Armenian tradition also demanded that the bride does the bidding of the groom’s family, especially his womenfolk, that she becomes a kind of servant. My grandmother (educated by American Protestant teachers) didn’t much care for this arrangement. Bride and groom stayed there nine months and then moved to their own place. Their departure created an indelible rift. “They never forgave us,” my grandmother wrote in 1983 ub her terse “My Life.” Only in the last few years have I come to wonder if she also never forgave them.

Many journeys and much anguish lay ahead.

After the Great War the victorious English and French divided up the Middle East, a complex web of alliances and betrayals and land grabs that reverberate to this day. My grandparents were hastily forced out of Adana, east to Alexandrette, Syria where they lived for four months before taking a ship to Constantinople. They remained there less than two years before leaving for America.

In 1921 the other Kalpakians were also forced out of Adana. Harry’s mother and father, one sister and two brothers got French passports which allowed them to go to Romania. Another sister, her husband and children, the husband’s mother and his unmarried sister went to Haifa in Palestine, and later to Jerusalem.

Many journeys and much anguish lay ahead. Time and again history uprooted these Kalpakians, and split these families further. Shortly before World War II, the Romanians revoked French passports and many of these Romanian Kalpakians were evicted; they went to France where they lived through the Nazi Occupation.

Imagine the dizzying array of passport and visa stamps

Those Kalpakians who went to Palestine endured the ongoing conflicts in the Middle East. Ousted from post-World War II Jerusalem, they moved to Syria, splitting again, some to Lebanon, some of them eventually on to Canada and France. In the 1980’s my grandfather’s nephew brought his family to America. One can only imagine the dizzying array of passport and visa stamps, decades of official documents signed by unsympathetic bureaucrats.

No such upheavals awaited Harry and Helen Kalpakian. On arrival in Venice, California, they had an instant home. They moved into the gardener’s cottage on the grounds of 905 Harding. This fine ten room house was owned by Helen’s sister and brother-in-law, John Boyd (Anglicized name) who had sponsored their immigration, They had emigrated at least fifteen years earlier and John Boyd was now successful pharmacist. The Boyds had two children. Helen’s older brother, Art Clark, also lived there until his marriage in 1926, (That gala wedding reception is one of my mother’s earliest memories). Helen also had a beloved cousin and her family living nearby.

How did Harry fit in with these people? No anecdotal evidence remains, save that in 1927, Harry quarreled bitterly with John Boyd. The Kalpakians abruptly moved out of the gardener’s cottage and into an unfurnished rental where they used overturned orange crates for beds for the little girls. Harry never again spoke to John Boyd, nor went to 905 Harding Avenue. Helen continued to see her sister, though that relationship was no doubt strained by this profound quarrel.

Harry’s family vanished altogether, beyond even the pale of inquiry.

My grandfather became a grocer, small mom-and pop stores; in 1931 they bought a house. In 1940 they moved to a large duplex on Olympic Boulevard, and lived on the upper floor. This was the only house of theirs we, the grandchildren, knew. In it there was nothing of the old country, other than the rugs on the floor and the books in Armenian language on the bookshelves. There were mirrors in the front hall, the dining room, the bedrooms and bathrooms. No pictures save for a single framed California desert scene that hung in the livingroom. No family photographs whatever. No mention was ever made of Harry’s family, certainly not to us. It was as though they had vanished altogether, beyond even the pale of inquiry. And so they had. Not until 2016 did we, the grandchildren, reconnect with the cousins living in France.

For all his sophistication, he was still a dumbbell.

Harry Kalpakian (1887—1963) became an American citizen, but he remained Old Country in a way that my grandmother did not. He wore, no matter the weather, a coat and tie and long-sleeved white shirt, a hat when he went out. He was soft-spoken and there was about him a quiet formality. He told old country Hodja stories. My grandfather read books in Armenian, but he never used it to speak to his children. His religion was the entrenched rituals of the Armenian Apostolic church, but his daughters went to the nearby Protestant church; they married in Protestant churches and brought up Protestant children. His parents, his brothers, his sisters dispersed in 1921, and Harry never saw any of them again.

“The Land of Lucky Strike,” only explores the central character’s sense of strangeness in a new land, where, for all his sophistication, his reading, his many languages, he was still a dumbbell. Revisiting my own work, I marvel at my limits of my imagination and the questions I never asked.

“The Land of Lucky Strike” was broadcast by the BBC2 on Christmas Eve in 1982. A British friend taped it and sent me the recording. I sent it to my widowed grandmother. It was the only story of mine she ever liked.

The Unruly Past: Memoirs [Paint Creek Press 2021] has a long chapter about the Kalpakians, and their relationship to their past.

The post THE LAND OF LUCKY STRIKE appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

July 4, 2023

Story? Novella? Novel?

As a writer I love the novella because it has the pleasing economy of the story and the density of the novel. For these reasons I so admire the work of the great maestros of this form, Katherine Anne Porter, William Trevor and Mavis Gallant. Porter herself rather snorted at the term novella. She wrote somewhere words to the effect of, Call it a short novel or a long story, but novella just sounds cheap and demeaning. In truth the novella is an elusive literary form. Can be defined by page length or word count? Can it be picketed by its thematic content, or time frame, or number of characters? I think not. My (admittedly fluid) standard is this: how long does this tale need to be in order to come to fruition?

No one sets out to write a novella. One might start a story, but seeing the story shake off that harness and gallop away, seeing it gain momentum and defy gravity, seeing that the page count is billowing, the writer gulps. Oh, no! Shall I rein this narrative in, and keep it to say, less than twenty pages, a length that might make actually find print? Or do I unleash it and see if it will become a novel? And if it does not become a novel, and has ceased to be a story, what the hell do I do with it?

Please do send us your overlong, bloated pieces

The novella is far more difficult to publish than either the novel or the story. Few literary journals, online or not, ask, Oh, please do send us your overlong, bloated pieces to deprive other writers of space and tax our readers’ patience and their attention spans. No. They say: Short fiction. Few publishing houses, even tiny independents, never mind the Big Five, will put their resources toward a book of say, a fifty or a hundred pages that can only command a small price, no matter who the author is.

The novellas I have written have appeared amid the And Other Stories in books like Fair Augusto, Dark Continent, The Delinquent Virgin (all of them, and Other Stories). The novellas, generally the strongest pieces in the book, are the anchors in these collections. All of them began life believing they were stories. Or at least, I believed they were stories.

How much more was lurking under the surface of the original!

Only one of my stories consciously evolved into a novella. In the late 1980’s there was a PBS program called American Playhouse that brought stories of American writers to the small screen. I had an unpublished story, about two soldiers who come home at the end of World War II and disrupt the routines and camaraderie their women (neighbors) have created in wartime. I sent “Wine, Women and Song” to the American Playhouse producer who liked it, but she thought it was “thin” and needed more. As I went to work, to open it up, I was astonished to see how much more was just lurking under the surface of the original, development I had evaded in my hope to keep the story at a “publishable” word count. A few months later I sent it back to her, only to hear in reply that this producer had left American Playhouse, gone off to become a pastry cook! American Playhouse folded soon after.

“It’s only a story” is a good way to wade into writing a novel.

It’s much easier to face the empty page (or empty screen) and say: I’m going to write a story, than to tell your trembling self, I’m going to write a novel that might eat up years of my life that I could have spent maintaining friendships or knitting sweaters, or becoming a Zen master, or watching the re-runs of Law and Order. I have found that believing “It’s only a story” is good way to tiptoe into the novel. Like telling the reluctant swimmer, Go on, wade into the shallow end, instead of tossing that poor swimmer into the deep.

Buyer Beware is not a good look for the bookstore shelf.

Caveat [Paint Creek Press, 2022] was one such book. Eighteen years passed between the time I began writing and when I first published it in 1998. It is the tale of a rainmaker in Southern California in 1916, and started life as a story called “Caveat Emptor.” At fifty-plus pages, I acknowledged it had become a novella; I planned to use it as the anchor, the last, most ambitious piece in a collection, but I didn’t. I had finished the novella, but had the nagging these characters and their relationships needed more time to develop, in short, to come to fruition. When it grew into a novel, the title change was imperative; Buyer Beware is not a good look for the bookstore shelf. It is the shortest novel I’ve ever written.

Miscreant, noisy characters and their unruly individual stories.

I blush to admit that These Latter Days began as a story, slid into novella, and from there into a long novel with a steadily growing cast of characters, and an increasingly complex structure. TLD (as we call it) evolved into a 400 or 500 page novel (depending on the edition) in which only one paragraph of the original story remains. Revising over some eight years, I came to have ambivalent relationships with these characters, in particular, the central character, Ruth Douglass. Put bluntly, I was sick of her. But I did not feel I could move forward till I had seen this book into print. So, the struggle continued.

All right, I will tell this story the way it needs to be told.

Finally I had a residency at the Montalvo Center for the Arts in Saratoga, California. I knew this was the last otherwise-unencumbered chunk of time I would have for a very long while. My then-agent had interest from a powerful editor who wanted the convolute story laid out chronologically. I was so eager for print, I agreed to do this. (Though I knew that chronology would never suit the whole book.)

This editor read 100 pages and declared herself longer interested. Once I finished gnashing, I was actually relieved. I thought: All right, I will tell this story the way it needs to be told. But even with that bold vow, I also knew I had to exert some kind of authorial control over these miscreant, noisy characters and their unruly individual stories.

My resolve remained, but my authorial heart broke.

As I worked my way through the book, I found two chapters that impeded the forward thrust of the novel. (If a novel that diffuse can be said to have a forward thrust.) These were focused on one character, Gideon Douglass (born 1892) Ruth’s eldest son. These chapters had to be cut. My resolve remained, but my authorial heart broke. If cut them, they would just rot in some forgotten folder. Even though I was under a pressing deadline (the Montalvo residency would end in May) I stopped work on TLD and gave myself a few days to turn them into stand-alone pieces. “And Departing Leave Behind Us,” and “Sonata in G Minor” taken together chronicle a young man’s hopes, potential conflicting with his religious beliefs, and societal expectations. The two stories suggest the core weaknesses of Gideon’s character and the life he will have as an adult.

Stories about a Mormon boy in 1909 didn’t exactly scream Relevant! Relevant!

I could not combine the two chapters into one novella because “Sonata in G Minor” is told with a distant third person narrator and covers months. “And Departing Leave Behind Us” is a first person narrative by Gideon’s sassy, know-it-all sister, Afton. It takes place on one day, Gideon’s 1909 high school graduation. The title comes from his valedictorian speech, lines by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: “Lives of great men all remind us/ We can make our lives sublime/And departing leave behind us/ Footprints on the sands of time.”Afton has genial contempt for “Mr. Henry Wordsworth Longfellow.” Her emphatic narrative voice and the tiny crack in her certitude are what give the story its charm.

Though I polished these two stories, I never tried to publish either one in mags or literary quarterlies. A Mormon boy in an obscure California town in 1909 didn’t exactly scream Relevant! Relevant! However, I placed them side by side in Fair Augusto and Other Stories. And that is exactly where they belong.

Ironically, I have recently returned to work on the original novella that became TLD. It has already grown into a novel, so that won’t happen. It’s way too long for a story. When it’s finally finished (if it is finally finished) what will I ever do with it?

—

Paint Creek Press has reissued Fair Augusto and Other Stories in 2023, Dark Continent and Other Stories in 2021, and These Latter Days in 2021. Delinquent Virgin and Other Stories is forthcoming from Paint Creek Press.

The post Story? Novella? Novel? appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

June 26, 2023

North and East: The Fortune Teller

We went on a lark. Friends of long-standing, we were all young, in our twenties that spring of 1969, but old enough to know that True Love, Fulfilling Work, Success, and all the rest of it would not be automatically conferred upon us like high school diplomas, or for that matter, college degrees. In one of our shoot-the-cosmic-shit convos someone mentioned they’d heard of a famous fortune teller right here in Southern California. She lived in an isolated trailer on acreage in a high desert area not all that far from Riverside. Someone suggested, instead of wondering about our futures, let’s go ask!

We had heard she only worked Saturday and Sunday and only took so many clients a day, first come, first serve. So on a Friday evening we caravanned there and camped overnight in a field beside a narrow road and across from her place, a dreary looking double-wide set on a low hill. We brought sandwiches and chips and an ice chest with beer and entertained one another with what-ifs. “What would you do if she told you….” Ha ha ha. We finally crawled into our respective sleeping bags, and slept in our clothes. Someone brought an alarm clock. Waking at dawn we waded through the weeds downhill to pee and then stowed our gear in the cars. Across the road, in front of the double-wide people were already lined up.

Everyone ill at ease. No one wore a wedding ring.

I cannot remember the fortune teller’s name, so let me just call her Madame S. Madame’s assistant, a plain woman of indeterminate age, finally opened the door and allowed about twenty of us in. She took our names and cash money ($25? $50? Can’t recall, expensive in that era when gas was 39 cents a gallon, and cigarettes were 25 cents a pack.) The assistant told us to wait on utilitarian couches and chairs that lined up, facing each other. Florescent light fixtures buzzed overhead. The place vibrated with that same silent unease you find in a doctor’s waiting room. (How sick is that dude across from me and what’s he got?) Except for me and my friends, everyone else was middle-aged, and I noted, no one wore a wedding ring.

Before Madame was to see the first client, the assistant informed us of protocol. We should not talk to Madame until she spoke to us. She would allow each person two questions. No more. And when she was done, even if you were not, you would be shown to a back exit. (Thus no one staggered back through the waiting room, looking stunned or haggard or joyful or confused.)

Yes, she had a crystal ball.

Madame S. must have had a buzzer or some such, because the assistant knew exactly when to call the next person. Each client got about fifteen minutes. I studied the framed photographs on the walls, glamorous Hollywood types who left florid testimonials and gratitude to Madame S along with their signatures. As the waiting room began to empty out, and one by one my friends exited and did not return, I began to get what is formally known as the heebie-jeebies. Finally my name was called and I was pointed to a door. I opened it, walked down the short hall and opened another door.

“Will my brother Doug come home from Vietnam?”

After the florescent glare in the waiting room, my vision faltered. It was a small, close room, lit only dimly by a single lamp and some votives, the one window covered by heavy drapes. The walls were hung with many scarves or shawls of varying lengths and hues. Madame sat at a small table, and yes, she had a crystal ball. To my recollection she was probably about sixty, stout, even dumpy, wearing a loose caftan in dark colors, her graying hair in a braid. Her thick glasses (the proverbial Coke-bottle glasses) obscured her eyes. She pointed to the chair across from her and I sat down. She took my hand, petted it, not as though reassuring me, but as though tugging at me. I remember nothing of her mumblings, except for two things.

One of my two questions was complex, but the other was simple: “Will my brother Doug come home from Vietnam?”

“Yes,” she replied without hesitation.

At that an unseen assistant entered the room, and brushed aside a shawl.

Just before Madame S. let go of my hand, she said, “North and east.”

“What?”

“Your future lies north and east.”

The assistant opened the door and I stumbled outside, blinking against the brightness, the blue sky. I was alone. Down on the road my friends waved to me.

We’re in Southern California, lady!

Driving back to Riverside we talked about what she’d variously told us, and decided it was mostly stupid. We dismissed her as a charlatan. I said, “North and east? Really? We’re in Southern California, lady! South of here is Mexico and west is the Pacific Ocean. Where else is there to go? ” We had a good laugh and I forgot all about Madame S.

One of the great undeserved mercies of my life.

That fall—on an impulse, really, what amounted to an utter whim—I quit my job, went to the East Coast to visit. I did not come back to live in California for three years. Some of the most consequential years of my life. I made the friends of a lifetime. I got a Masters in history. I stood up in front of a college classroom posing as a professor who knew her shit while I struggled to live up to the responsibility. I lived in a community that was, for me, the equivalent of Junior Year Abroad. I met the man I later married, father of my sons. I took part in massive anti-war protests in DC. I drove across country and down the coast to Florida. I went to Europe. And though I could not have known it then, living on the east coast was one of the great undeserved mercies of my life.

Why? Because I was not in Southern California when my brother returned from Vietnam. Doug was riddled with malaria, hepatitis, skin afflictions, hallucinations and drug addiction. He was denied any kind of help or care from Veteran’s Administration due to his Undesirable Discharge. His care fell wholly on my family; the shock and loss and terror at what he had become left indelible stains on the psyche of everyone around him. I was not around him. I did not see these events firsthand.

I wished I been more specific.

Doug Johnson, in uniform

When I did come home, when I saw my brother. I thought instantly of Madame S. and wished I’d been more specific. I should have asked: Will Doug come home from Vietnam and still be a whole human being?

How would she have answered that? How could I have guessed what war would do to him? Of what war could do to any eighteen year old boy who cavalierly dropped a class at the community college and was thus so ripe for the draft that he up and enlisted. The army basic-trained Doug Johnson at Fort Ord, took his photograph in a smart uniform, and shipped him off to Vietnam, just another 4th Infantry grunt. Oh, and in May 1970 they sent him into Cambodia, the country that Nixon had assured the American people he did not intend to invade. My mother saw Doug in Time magazine photograph standing in front of a helicopter in the jungle with a bunch of other hapless grunts, one of them making a weak peace sign. Doug went AWOL in Cambodia. All that before he was old enough to vote. I wish I could say the rest was silence, but it was not.

I moved north to take a Visiting Writer gig for only six months

In 1984 on another whim, I packed up my two little boys, got in the car, stuck La Traviata in the tape deck and drove north to Washington state to take a Visiting Writer gig that would only last six months. It lasted five years, as it turned out, and when it ended, I stayed on in the house I had bought. I made a life with my sons. I made a living with assorted teaching jobs and workshops while writing and publishing nine books between 1989 and 2006 the year my youngest graduated from college. I still live in the same house, eighteen miles from the Canadian border.

North and east indeed.

The post North and East: The Fortune Teller appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

June 19, 2023

“Veteran’s Day”

Memoir obliges the writer to fling words like a footbridge across the past. Having trod that footbridge, the writer hopes to come out on the other side with better understanding. In any event, the deed is done, and the memoir writer can move on. Fiction obliges no such thing. Fiction condemns the writer to returning—time and again—to leave and revisit—with or without understanding—the themes, characters, places that haunt that writer.

The fucked-up Vietnam vet is a recurring character in my fiction. Each iteration of this character is set in different circumstances, but they are rooted in the experience of my brother, Douglas Johnson (1950—2021). Doug was a casualty of the Vietnam War, though he lived through it. He came home a hollowed-out human being. He was talented and could be charming; he was charismatic and without scruple, a drug addict. I personally did not suffer at his hands. But I know plenty of people who did. For decades.

First Prize in the Stand International Short Fiction Competition

I first created a character echoing Doug’s experience in “Veteran’s Day,” the lead story in Fair Augusto and Other Stories. The first person narrator is a hairdresser, Betty Sutton Lusky, sister of the demented Vietnam vet, Walter Sutton. I will not recount the story here; it can speak for itself. Suffice it to say I poured time and tears and years of care and pain into many drafts of “Veteran’s Day.”

“Veteran’s Day,” won first prize in the first Stand International Short Fiction Competition in 1983. (Stand is a venerable Leftist literary mag based in Leeds, UK.) My British agents had submitted it for the prize, though they thought it unlikely to win; it was a long story, grim, and very American.

“I’m telling the truth! That’s what it says!”

In 1983 I had other things to worry about. Amid a lot of domestic upheaval I had left Florida and was finally renting an apartment in Redlands, California where I lived with my two little boys, Bear and Brendan. Since my address had been in flux for some time, I used my parents’ address for all things professional.

One afternoon my father called me and said a letter had come from my agents in England. I told him to open it. Inside, in addition to the agency note, there was a letter from Stand. “Veteran’s Day” had won the International Short Fiction Prize.

I said, “Don’t joke. This is not funny.” (My dad was sometimes known to have a weird sense of humor.)

“I’m telling the truth! Honest! That’s what it says.”

I still didn’t believe him. I told him to bring the letter over immediately. And he did. He stopped on the way to buy a bottle of champagne.

I felt so vindicated! In December I went to England to collect the award. I thanked Stand, the judges and my British agents. I did not speak of my brother. I almost never speak of my brother.

The army spat him out like gristle.

Douglas Johnson spent two years in Vietnam, 1968 to 1970 fighting their dirty little war. At the end the army spat him out like gristle from an underdone chicken wing at an All-States Picnic. They gave him an Undesirable Discharge [“in lieu of a court martial”] that denied him any veteran’s benefits, including medical, dental, psychiatric, and rehab, that denied him the GI Bill, and denied entrance to many jobs. When the army released him, and my father picked my brother up at Fort Lewis, he was clutching the sandal of a Vietcong he had killed. Doug’s enormous medical and psychiatric expenses fell upon his middle class family. (My father was a pharmaceutical sales rep; my mother was a secretary at County Hospital.) The emotional burdens implicit in those medical and psychiatric tribulations fell on them as well. They had two younger children still at home.

Doug Johnson and his mother, 1969

In the midst of that daily turmoil, my parents fought for years to get that Undesirable Discharge reversed. And what a fight it was. They took on the army, the government, even the inner sanctum of the Nixon White House which in 1973 had begun to crumble under the weight of Watergate. My father would often skip work, go to the public library, research, chase down leads, write letters in his almost-unreadable scrawl. My mother would decipher and type them at night, make careful carbon copies, file them. When they got replies, they took up those denials and challenges, and fought on. In the end, they won. The Undesirable Discharge was reversed, and Doug could use VA benefits, and the GI Bill. This was my parents’ finest hour, a heroic achievement.

Am I equal to building a footbridge over that pain?

The raw materials of that struggle—that is to say the carefully kept carbon copies—are here in this house. In the basement. I have always vowed I would outlive Doug and then I would use these documents to write the history of what the army did to him, and my parents’ epic struggle to free him from the ignominious Undesirable Discharge. I have outlived Doug. But am I equal to exhuming those documents from the basement? Am I equal to revisiting that rage? Am I equal to building a memoir-footbridge over that pain? Do I dare?

I thought: He’s going to kill her after all.

Doug Johnson first contracted hepatitis (along with malaria and malnutrition and skin afflictions as well as a vicious drug habit) in Vietnam when he was between eighteen and twenty years old. All his life he suffered from liver problems. In about 2018 his innards were so ravaged that he had to have an ostomy and he was hospitalized for three months. In late October of 2020 he telephoned to say that he had been diagnosed with liver cancer, that he had six months to live. He had a lot less time than that. On the morning of January 5th 2021, he died in the California home he shared with his third wife.

My mother sat in stunned silence when I told her this news. Five days later, on the night of January 10th 2021 she had a heart attack, found face down on the bedroom floor the following morning. As I drove behind the ambulance taking her to the ER, I thought: After everything he’s put her through, he’s going to kill her after all. But he didn’t. She lived. Lives still.

Where is the wall not simply for dead humans, but for dead humanity?

Perhaps the fitting epitaph for my brother can be found in a chapter in a still-unpublished novel where I wrote of a troubled, drug-addled Vietnam vet named Ace. In the spring of 1969, a few months after he got out of the army, Ace bought a blond wig to cover his stubbled hair. He bought a VW van, forsook his Baltimore family, and went on the road, taking with him the harmonicas he had learned to play in Nam and a duffel bag that held the sandal of a dead Vietcong and a chain of human ears. He picked up a couple of hitch-hiking musicians with whom he shared warmth, camaraderie and adventures with a broader circle of friends. However, drug-lust triumphed and Ace betrayed their trust. As the years rolled on, he lost his way, time and again, along with his harmonicas, and any chance he had at love. In the book Ace vanishes into the maw of homeless oblivion.

Here are the closing lines of Ace’s chapter:

“Maybe when Ace dies they’ll inscribe his name on that wall in Washington. Maybe someone will scrawl it, graffiti among the graven names, there among the fifty-five thousand known dead. Cleon Waters’ name is there. The grunt who killed the whore with the heart of tin, his name is there. Where is Ace? Where’s the wall for Ace’s name? Where is the wall not simply for dead humans, but for dead humanity? Where is the monument for them? What can it possibly look like?”

____

Paint Creek Press will republish Fair Augusto and Other Stories on Tuesday, June 20th 2023. It is dedicated to the British literary agents, Verity Mason and Juliet Burton.

The post “Veteran’s Day” appeared first on Laura Kalpakian.

June 13, 2023

Fair Augusto, fair fair Augusto

In his genial account of a solitary road trip across the US, Travels with Charley, John Steinbeck muses that there are some journeys that are never over. He tells of a man he knew in boyhood, in Salinas, California who had once been to Honolulu. Steinbeck said, years later you could see him rocking on his front porch, mentally still in Honolulu. For me, that place was Venice. My initial month-long stay in Venice has, in some ways, never ended. Venice rooted itself in my imagination forever. I first went to Venice on the bounty of the advance for my first novel, a time in my life so heady that the seed of promise seemed to me to be the full-blown blossom of assurance. Moreover, this was back in that halcyon era when publishers gave the author the whole sum at once. (Over the last twenty or so years, publishers divvy up the advance in threes: one-third on signing, one-third on final acceptance of the manuscript and one-third on publication. This practice is not merely pissy and unkind, it is unjust. Why should the mega-corporation hold on to these sums when the money is so much wanted/needed by the poor author?) The check for the advance arrived. I took a picture of it before depositing. I bought presents for everyone. And Paola Rizzoli invited me to come to Venice. Paola was pure Venetian, but she was also a grad student at Scripps Institute of Oceanography at UCSD with my husband, Jay McCreary. At the time she was married to a classical guitarist, Francesco Rizzoli who had come with her to California. They lived in a tiny apartment, and while Paola went to Scripps, Francesco practiced classical guitar. Jay McCreary was also a serious classical guitarist, and Paola played the violin so when they came to our apartment, people would stand in the alley below just to hear the music pouring out of our open windows. At the end of that year, they returned to Venice, where they split up. In September Paola returned to California alone. Paola and Jay and I remained close friends the whole time we were in grad school. (I was in Literature at UCSD.)

I lived in a state of Heightened Awareness

From the moment I set foot there, Venice left me dazzled. It was truly like stepping into the past. The past in Venice is everywhere present. The scientific institute where Paola worked was a palazzo on the Grand Canal and the water-level room sheltered a boat that had fought at Lepanto in 1571, the last naval battle that used oared vessels. Her apartment with its cool marble floors was between two sleepy canals, replete with the slosh and smell of green water, the calls of boatmen, the damp heat billowing in through the windows, the glow of stones in the afternoon light. Paola went to work every day and in my platform sandals I explored the city. The shudder of the vaparetto under my feet, musical voices in a lingo I could not understand, the competing orchestras in the Piazza San Marco, the dark churches and museums, the splashed-sunny piazzas, all created indelible magic. I first tasted basil risotto and thought I had ascended. I lived there in a state of what I can only call Heightened Awareness, every sense alive, tingling, awaiting the next new sensation, becoming a character in my own story. Mid-August two other UCSD friends, Karen Shabetai and Nancy Hancock, who were traveling in Europe, came to Venice and the three of us spent a week exploring Florence and Rome. We returned to Paola’s apartment at night and as we crossed the small bridge, I stopped, awash in magic. An unseen classical guitarist somewhere nearby flawlessly rendered “Romanza,” a song Jay often played. The music counterpointed with the lisp of water in the canal. The moment could not have been more beautifully orchestrated if I had written it myself.

Ferragosto, which I heard as Fair Augusto, the image on a Roman coin

The title piece, in my first collection of stories, Fair Augusto takes place mostly in the Piazza San Marco on that purely Italian holiday, August 15th. All of Italy closes down—and has for thousands of years—for Ferragosto. I, speaking no Italian, heard this as two words, Fair Augusto, and conjured it somehow in my mind with a notion of a beautiful image on a long ago Roman coin. As is my usual writing process, I wrote the novella “Fair Augusto” in a few days, and then revised for years. I had scant hope of publishing it because it was so long. A friend suggested I turn it into an actual novel and then I could more easily see it into print. I declined. The piece was exactly as long as it needed to be. Finally, I put “Fair Augusto” into a manuscript with twelve other stories.

The title piece, in my first collection of stories, Fair Augusto takes place mostly in the Piazza San Marco on that purely Italian holiday, August 15th. All of Italy closes down—and has for thousands of years—for Ferragosto. I, speaking no Italian, heard this as two words, Fair Augusto, and conjured it somehow in my mind with a notion of a beautiful image on a long ago Roman coin. As is my usual writing process, I wrote the novella “Fair Augusto” in a few days, and then revised for years. I had scant hope of publishing it because it was so long. A friend suggested I turn it into an actual novel and then I could more easily see it into print. I declined. The piece was exactly as long as it needed to be. Finally, I put “Fair Augusto” into a manuscript with twelve other stories.

Years passed. Truly, years.