John Coulthart's Blog

November 29, 2025

Weekend links 806

Cover art by George Wilson for The Twilight Zone #45, September 1972. Via.

• At Public Domain Review: Thea Applebaum Licht on the history of art within art, or cabinets of curiosity and paintings within paintings.

• The final 2025 catalogue of lots for the After Dark: Gay Art and Culture online auction. Homoerotic art, photos, historic porn. etc.

• At Smithsonian Mag: See the “Mona Lisa of Illuminated Manuscripts,” a 600-Year-Old Bible covered in intricate illustrations.

It’s amazing, the number of people out there who love everything about queer life except for queer sex, who would prefer that sex and sexual orientation live in entirely different zip codes, that they exist as non-overlapping magisteria; it’s so much safer that way. Who wants gay sex polluting their enjoyment of the abstraction that is Being Gay?

That is what gay love is, now, in the collective imagination of American commerce: a set of identity relations projected onto bored and indifferent celebrities who will half-heartedly play along with the idea because doing so moves units and, anyway, what does it cost them? The more that sexual orientation slouches to the point of pure abstraction, the less effort it takes. Anyone and anything can be gay, now, because gay is just a set of pompous liberal cultural signifiers that have no earthly material relation to homosexuals.

“I miss when homoeroticism was erotic,” says Freddie deBoer. I’ve made similar complaints myself over the years. For some genuinely erotic homoeroticism, see the latest auction link above.

• At Ultrawolveunderthefullmoon: Illustrations for Edmund Weiss’s Bilderatlas der Sternenwelt.

• DJ Food’s latest harvestings of psychedelic ephemera may be seen here.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Bruce Connor’s Day.

• The Strange World of…David Lynch.

• RIP Udo Kier and Tom Stoppard.

• Menergy (1981) by Patrick Cowley | Eros Arriving (1982) by Bill Nelson | Erotic City (“Make Love Not War Erotic City Come Alive”) (1984) by Prince & The Revolution

November 26, 2025

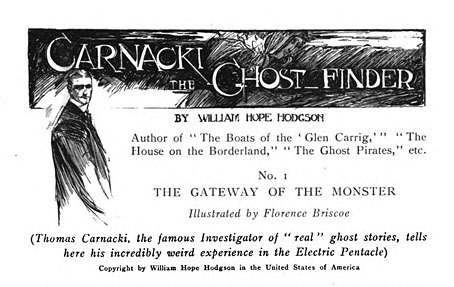

Carnacki’s first manifestation

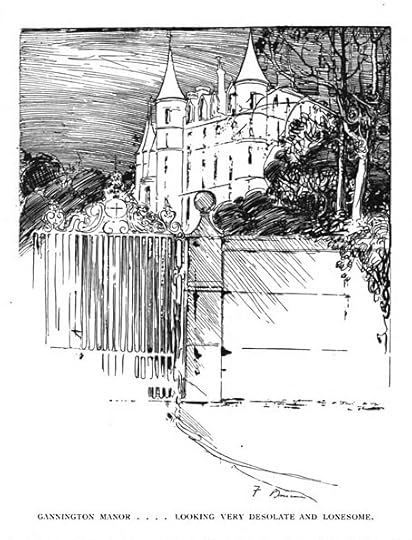

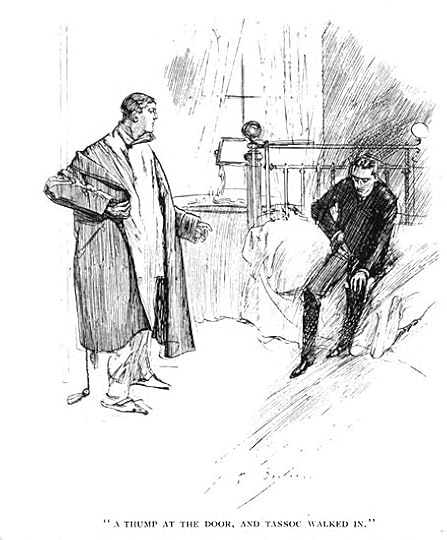

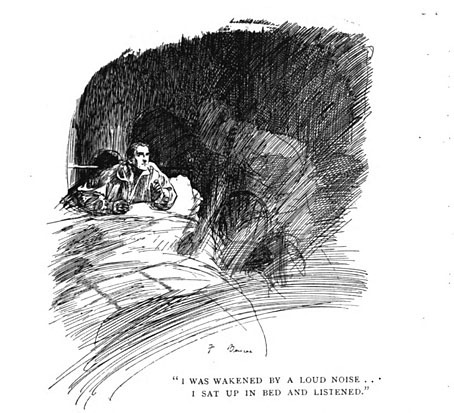

Visual manifestation, that is. The first Carnacki story to see print was The Thing Invisible, published in 1909 as a part of The Ghost Pirates, A Chaunty, and Another Story. The book wasn’t illustrated, nor was the Carnacki collection published by Eveleigh Nash in 1913. The five stories that ran in The Idler, however, were all decorated with sketchy illustrations by Florence Briscoe, all of which may be seen in this collection of extracted pages from the issues for 1910. (For the complete magazines, look here.)

The House Among the Laurels.

Miss Briscoe (and she does appear to have been a Miss at this point) has the distinction of being one of the first illustrators (possibly the first) of any of Hodgson’s fiction. She was also a friend of the author and may well have used him as a model for many of her illustrations. James Bojaciuk suggests as much in this piece of biographical research that I’d managed to miss when it was posted at Greydogtales. I think we can take Hodgson as a definite model for the portrait of Carnacki that illustrates the magazine header, the similarity between the drawing and one of the author’s photos is beyond doubt even if some of the other Carnacki drawings show less of a resemblance. Carnacki also seems to be quite tall, or at least of average male height, something that the diminutive Hodgson was not.

The Whistling Room.

Portraiture aside, Florence Briscoe’s illustrations tend to be of a type that I refer to as “people standing about in rooms”, a common form in the world of magazine illustration. Sidney Paget’s famous drawings of Sherlock Holmes are almost all of this type, stories of cerebral industry and ratiocination being rewarding for the reader, less so for the jobbing illustrator. (The Hound of the Baskervilles is a notable exception, with its dramatic locations and spectral atmosphere.) The most obvious difference between Carnacki and Holmes is that Carnacki encounters genuine manifestations of eldritch horror which he manages to keep at bay with his incantations and electrical devices. Miss Briscoe shows us none of this, unfortunately. But her figures are well-drawn, and as general illustration her work is of a higher standard than the often amateurish renderings you find in the early pulp magazines of the 1920s. The growing sphere of Hodgsonian illustration begins with these few stories.

The Horse of the Invisible.

The Searcher of the End House.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Whistling Room, 1952

• The art of Jean-Michel Nicollet

• Suspicion: The Voice in the Night

• Hodgsonian vibrations

• The Horse of the Invisible

• Tentacles #2: The Lost Continent

• Tentacles #1: The Boats of the ‘Glen Carrig’

• Hodgson versus Houdini

• Weekend links: Hodgson edition

• Druillet meets Hodgson

November 24, 2025

The Whistling Room, 1952

Coincidence time again: this ancient TV drama was posted to YouTube a few days ago just as I was finishing Timothy S. Murphy’s very commendable study of William Hope Hodgson’s fiction, William Hope Hodgson and the Rise of the Weird: Possibilities of the Dark. As drama or even basic entertainment, The Whistling Room is the opposite of commendable but it is notable for being the first screen adaptation of a Hodgson story. Hodgson’s fiction has never been popular with film or television dramatists. His two major weird novels, The Night Land and The House on the Borderland, would require lavish expenditure and special effects to do them justice, while the latter has a narrative shape and a lack of characterisation that would either repel any interest or incur considerable mangling of the story.

More appealing for screen adapters are Hodgson’s tales of Carnacki the Ghost Finder, a collection of short mysteries with a supernatural atmosphere and neat resolutions. The Whistling Room, a US production for Chevron Theatre in 1952, is the first of two Carnacki adaptations, the other appearing almost 20 years later when Thames TV included The Horse of the Invisible in their first series of The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes. The Carnacki character was Hodgson’s take on the occult detective or psychic investigator, a short-lived offshoot of the post-Sherlock Holmes detection boom of the 1890s, and the concurrent interest in Spiritualism (or “Spiritism”, as Aleister Crowley always insisted it should be called). Carnacki is as resourceful and energetic as Hodgson’s other protagonists, and as an investigator he’s happy to use modern technology (electricity, cameras, vacuum tubes) to combat incursions from other dimensions. Hodgson’s descriptions of these encounters are freighted with all the capitalised terminology that recurs throughout The Night Land: “Outer Monstrosities”, “a Force from Outside”, “the Ab-human”. Carnacki’s exploits, however, have often been dismissed as hack-work when compared to the author’s novels or his tales of the Sargasso Sea. (The one Carnacki story that even detractors favour, The Hog, was a longer piece that only turned up many years after Hodgson’s death.) The stories are at their best when the mystery is an authentically supernatural menace, instead of another Scooby-Doo-like fraud being perpetrated by a disgruntled minor character.

The Whistling Room was the third Carnacki tale from an early series of five that ran in The Idler in 1910. The story is one of those that concern genuinely supernatural events, and is essentially a repetition of the first of the Idler episodes, The Gateway of the Monster, in which a room in an old house is haunted by an antique curse that plagues the present owners. The room in question isn’t as deadly as the menace in the first story, the mysterious whistling (or “hooning”) being more of a threat to the nerves of the household than to life or limb. But the whistling soon resolves into a more material manifestation.

Whatever power the original story may possess is thoroughly absent from the TV adaptation, a mere sketch of a narrative that wasn’t very substantial to begin with. Alan Napier—Alfred the butler in the Batman TV series—is hopelessly miscast as Carnacki, being more of a bungling buffoon than any kind of serious investigator. There’s no mention here of Carnacki’s favourite occult tools, the “Saaamaaa Ritual” and the Sigsand Manuscript, while the closest we get to his Electric Pentacle is a ridiculous “Day-Ray”, a raygun-like emitter of captured sunlight that has no effect at all on the cursed room. The room itself and its mysterious whistling is more comical than frightening, with dancing furniture that wouldn’t be out of place in Pee-wee’s Playhouse, while the Irish setting of the story is signalled by terrible attempts at Irish accents from two of the actors. Nobody actually says “begorrah” or mentions leprechauns but much of the dialogue is pure stereotype. The adaptation by Howard J. Green even shunts the resolution into Scooby-Doo territory when one of the local lads is found to be partially responsible for the whistling noises, an explanation that Hodgson’s Carnacki goes to some trouble to rule from his investigation.

I wouldn’t usually write so much about something that scarcely deserves the attention but this film is such an obscure item we’re fortunate to be able to see it at all. I’ve been wondering what prompted the producers to choose this particular story. The Whistling Room was first published in the US in 1947, in the expanded Carnacki collection from Myecroft and Moran, an imprint of Arkham House. If Howard J. Green (or whoever) had taken the story from there then we have to wonder why he favoured this one over the others. I think it’s more likely that Dennis Wheatley’s A Century of Horror Stories (1935) was the source, a British anthology but one which would have had wider distribution than an Arkham House limited edition. The only other option listed at ISFDB is a US magazine, the final (?) issue of The Mysterious Traveler Mystery Reader. But this was published in 1952 which puts it too close to the TV production given the time required to commission and schedule an adaptation, even a poor one such as this. Whatever the answer, I feel that thanks are due to the uploader for making The Whistling Room available. Now that my curiosity has been assuaged I’ll return to hoping that someone eventually gives us a better copy of The Voice in the Night.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Jean-Michel Nicollet

• Suspicion: The Voice in the Night

• Hodgsonian vibrations

• The Horse of the Invisible

• Tentacles #2: The Lost Continent

• Tentacles #1: The Boats of the ‘Glen Carrig’

• Hodgson versus Houdini

• Weekend links: Hodgson edition

• Druillet meets Hodgson

November 22, 2025

Weekend links 805

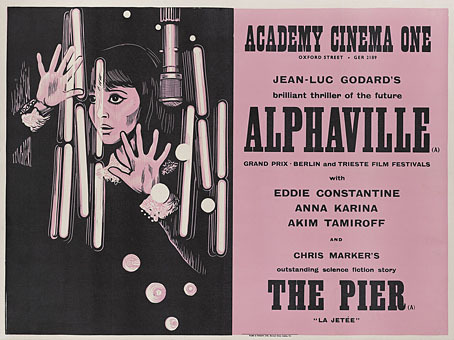

A poster by Peter Strausfeld for a 1966 screening of Alphaville and La Jetée.

• At Bandcamp Daily: “Caroline True obsesses over compilations so you don’t have to,” says Erick Bradshaw. I recommend CTR’s compilations.

• At The Wire: Read an extract from Music Stones: The Rediscovery Of Ringing Rock by Mike Adcock.

• At Colossal: Pastoral landscapes brim with patterns in luminous paintings by David Brian Smith.

One of the markers that sets Mamoru Oshii apart from his peers is his willingness to allow place to speak for itself. From the seasonality captured in his works, like the first two Patlabor films, to the otherworldly environments of Ghost In The Shell 2: Innocence (all projects in which Ogura was also involved heavily) and even the fantasy scapes of his Angel’s Egg, Oshii’s attention to place, and allowing it to be a player in the story, gives as much voice to world building, as he does to characterisation. This attentiveness and patience for place, allows us to settle deeply inside a worldview that is often simultaneously familiar but unerringly alien.

Lawrence English talks to art director Hiromasa Ogura and composer Kenji Kawai about their work on Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell

• At the BFI: Leigh Singer suggests where to begin with the films of Lucile Hadžihalilović.

• Necromodernist Architectures in Contemporary Writing: an essay by David Vichnar.

• New music: Hydrology by Loula York; Love Letters Via Echelon by Nerthus.

• There’s more Intermittent Eyeball Fodder at Unquiet Things.

• The Strange World of…Early Cabaret Voltaire.

• Winners of the Drone Photo Awards 2025.

• Drone Um Futurisma (1992) by Cusp | ABoneCroneDrone 1 (1996) by Sheila Chandra | Suspicious Drone (2009) by Demdike Stare

November 19, 2025

The Return of the Crawling Chaos

Behold Nyarlathotep, v. 3.0, this being yet another revision of an old illustration. Some readers may recognise the imagery from version 2.0 (2009) or even the original that appeared in my Haunter of the Dark book in 1999. Earlier this month the work I’ve been doing for the new edition of the book reached the end of another stage with the completion of all the necessary redrawing of The Dunwich Horror. I’ve also just finished drawing page 24 of the story, the page I’d left half-done when the strip was abandoned in 1989. Everything I do from now on will be new material.

Having got this far I decided to pay a little more attention to the upgrading of the book’s fourth section, The Great Old Ones, by finishing Nyarlathotep, something I began this time last year then set aside when I got involved in rescanning all the old comics pages. As I’ve mentioned before, several of the pieces for this section of the book were some of my earliest digital illustrations, created a few months after I’d bought a secondhand and very underpowered Macintosh computer. Nyarlathotep was an attempt to depict the hybrid nature of a Mythos entity which combines elements of an Egyptian pharaoh, the diabolic “Black Man” of European witch cults, a sinister stage magician or scientist, and the winged abomination that Robert Blake finds lurking in the steeple of the Starry Wisdom church. Version 1 was one of my very first digital collages which suffered as a result of my inexperience with the new medium, hence my eagerness to rework the design in 2009 when Cyaegha, a metal band I’d been working with, requested a Nyarlathotep-themed T-shirt. The first version had been aimed more at the theatrical/scientific aspect of the character, with a poster in the background from John Nevil Maskelyne’s Egyptian Hall in London. For version 2 I added a number of organic elements to bolster the “Haunter of the Dark” side of the character. Version 3 keeps all the details from version 2 while replacing some of the collaged elements with similar ones taken from better sources. The new design is also slightly taller to account for the enlarged page size of the new book.

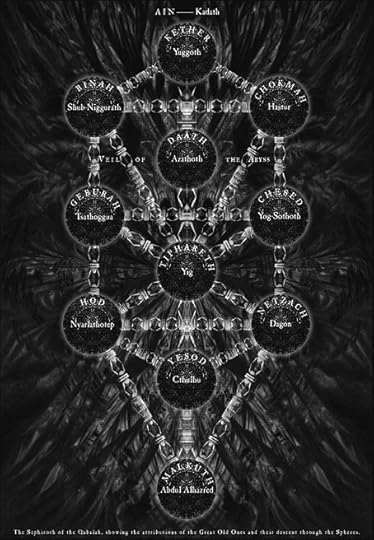

The Sephiroth chart from the second edition of the book, 2006.

The most notable additions to the new piece are the names of the character in Latin letters and Egyptian hieroglyphs (𓋔𓇋𓄿𓂋𓈌𓊵), the latter being a suggestion from this Reddit post. The Egyptian spelling is conjectural but I have a guidebook to the hieroglyphic language which confirms that most of the letters are the ones they should be. The words aren’t included solely as decoration. The Great Old Ones was a collaboration with Alan Moore in which Alan wrote eleven texts or invocations which position each god or entity on one of the spheres of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. Alan was heavily involved with the Kabbalah at this time, being also engaged with the first few issues of Promethea, a story which involves a physical (or metaphysical) journey from Malkuth to Kether. The Great Old Ones takes the same journey in reverse, and from a much darker perspective, like a Lovecraftian equivalent of the Qliphoth, the “nightside” of the Kabbalistic spheres. In Alan’s scheme, Nyarlathotep is positioned at sphere 8, Hod (or “Splendour”), a sphere associated with gods of magic and language like Thoth, Hermes and Mercury. I imagine most Mythos-acquainted occultists would agree with adding Nyarlathotep to this pantheon. In addition to being gods of magic and language, Thoth, Hermes and Mercury also serve as celestial messengers, a function which Lovecraft assigns to Nyarlathotep in The Whisperer in Darkness when one of the Mi-Go declares “To Nyarlathotep, Mighty Messenger, must all things be told.”

As for the rest of The Great Old Ones, I have four more of them still to be reworked, one of which, Abdul Alhazred (or Lovecraft himself) is almost finished. Further progress will be posted here.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Lovecraft archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Lettering Lovecraft

• Weird ekphrasis and the Dunwich Horrors

• Kadath and Yog-Sothoth

• Another view over Yuggoth

• Nyarlathotep: the Crawling Chaos

November 17, 2025

Sphinxes

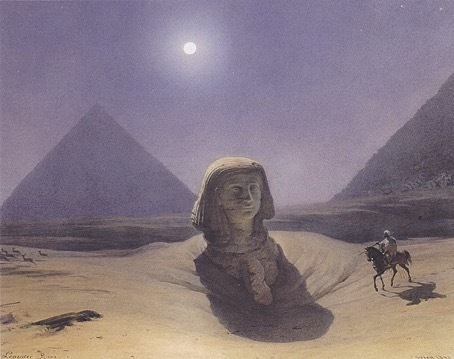

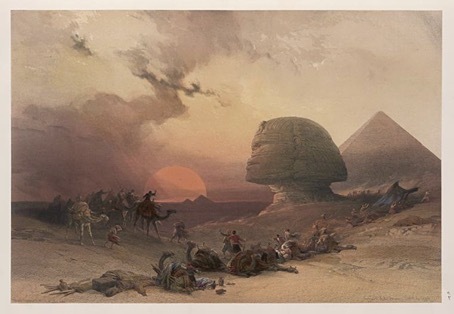

Bei den Pyramiden (1842) by Leander Russ.

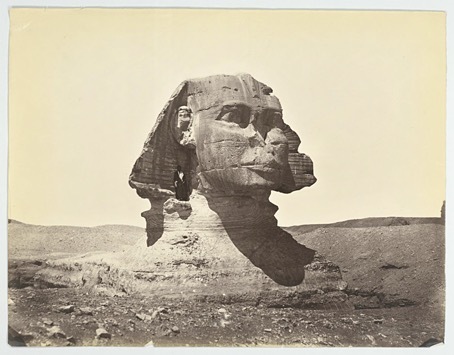

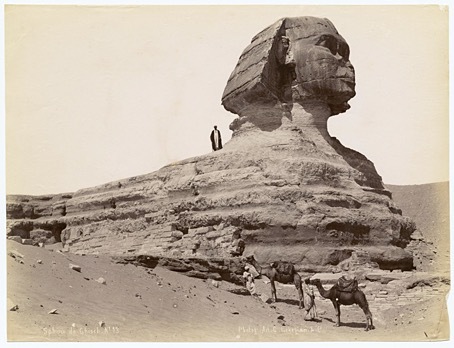

A horde of sphinxes from NYPL Digital Collections and Wikimedia Commons, a pair of sites I was searching through last week. I was looking for a very particular kind of sphinx, not the Great Sphinx that sits near the Pyramids at Giza. What I wanted was something smaller and less ruined, like the sentinels that proliferated during the fads for Egyptian art and design in the early 1800s and the 1920s. My search was satisfied eventually, the results of which will be revealed in the next post.

Approach of the Simoom. Desert of Gizeh (c. 1846–49) by David Roberts.

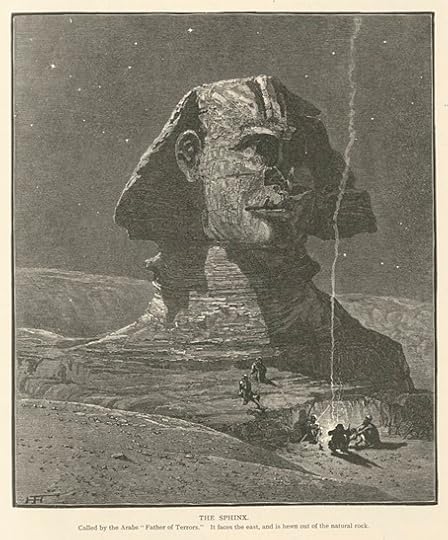

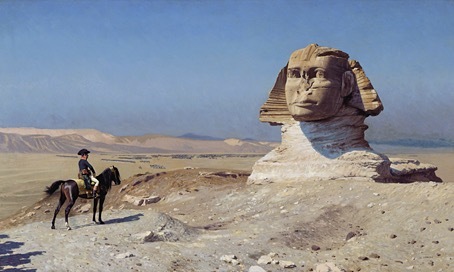

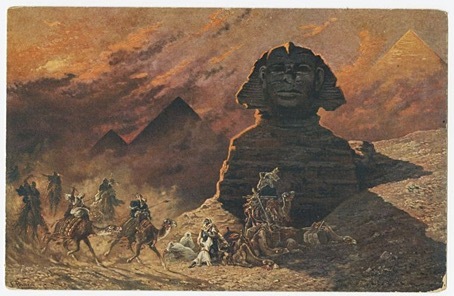

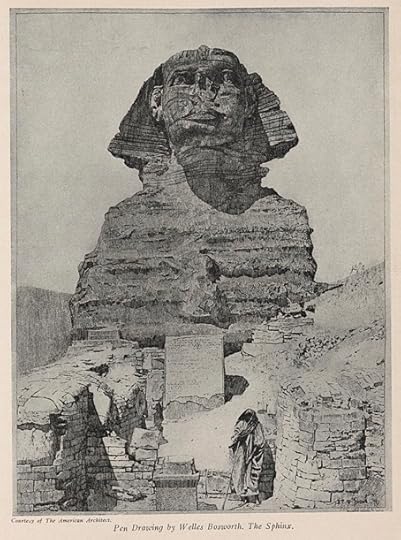

As for the Great Sphinx, I enjoy seeing artistic representations of the monument, especially those which place the creature in a dramatic setting. Older depictions tend to look bizarre or even comical, especially the ones made during the centuries when the figure was little more than a head protruding from the drifting sands. The photographs I prefer are those that show the Sphinx in the 19th century before all the restorations began, when the creature was another half-buried fragment of antiquity, not something that seems to have just been removed from a box in a museum.

The Sphinx and Great Pyramid, Geezeh (1858–1859).

The Questioner of the Sphinx (1863) by Elihu Vedder.

The Sphinx by Harry Fenn (1881–1884). “Called by the Arabs “Father of terrors.” It faces the east, and is hewn out of the natural rock.”

Bonaparte Before the Sphinx (1886) by Jean-Léon Gérôme.

The Great Sphinx By Moonlight (1890) by Eric Pape.

Le Sphinx au Simoun (c. 1918).

Pen drawing by Welles Bosworth. The Sphinx (1925).

Sphinx at Gizeh.

Sphinx de Ghiseh.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The sphinx of Wolf City

• On the pyramid

• Athanasius Kircher’s pyramids

• Watercolour ruins

• Le Sphinx Mystérieux

• The Feminine Sphinx

November 15, 2025

Weekend links 804

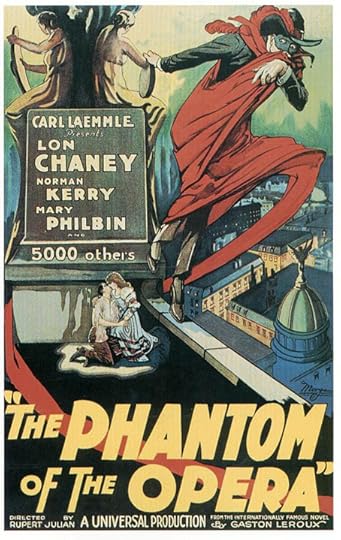

Poster for The Phantom of the Opera, 1925. The first Universal horror film, and the best screen adaptation of Gaston Leroux’s novel, was released 100 years ago this month.

• “Evolution seems to have a thing for mind-bending molecules here on planet Earth. Psychedelics are more widespread in nature than you might think. These remarkable compounds, which can profoundly alter consciousness, arose repeatedly across evolutionary time, stretching back at least 65 million years. To date, some 80 species of fungi, at least 20 plants, and a species of toad have been documented to produce psychoactive molecules. And scientists continue to identify new ones.” Kristin French presents a trip around our surprisingly psychedelic planet.

• “There was no condescending sense with Potter —all too present today as then—that the public were idiots who needed to be intellectually housetrained, by their enlightened ‘betters’. […] Television was not treated as a particularly serious medium, something Potter upended not by performing ‘seriousness’ but by bringing out the possibilities few had believed it contained.” Darran Anderson on the television plays of Dennis Potter.

• At Public Domain Review: AD Manns on a possible origin for the occult lore presented in Charles Godfrey Leland’s Aradia, Or the Gospel of the Witches, a founding text for the witchcraft revival of the 20th century.

• New music: Implosion by The Bug vs Ghost Dubs; Herzog Sessions by Mouse On Mars; VHS Days Vol. 1 by Russian Corvette.

• At the BFI: David West selects 10 great Hong Kong action films of the 1980s.

• Wyrd Britain talks to the great Ian Miller about his long illustration career.

• Mix of the week: DreamScenes – November 2025 at Ambientblog.

• At The Wire: Stream the new album by Ann Kroeber & Alan Splet.

• Seb Rochford’s favourite records.

• RIP Tatsuya Nakadai, actor.

• Phantom Lover (2010) by John Foxx | Phantom Cities (2020) by The Sodality Of Shadows | Phantom Melodies (2018) by Cavern Of Anti-Matter

November 12, 2025

Koho Shoda’s nocturnes

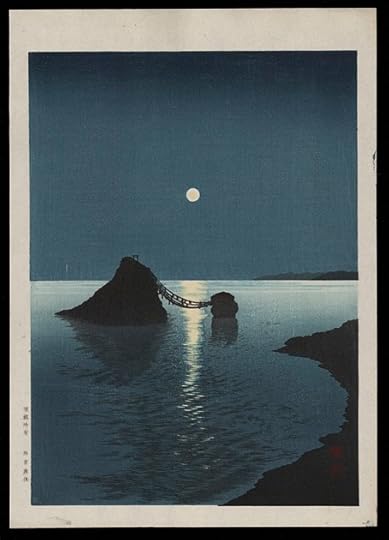

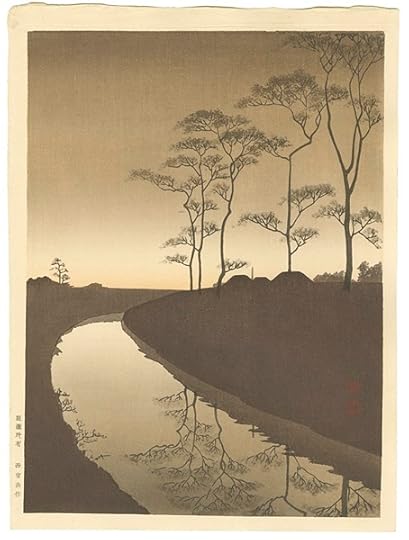

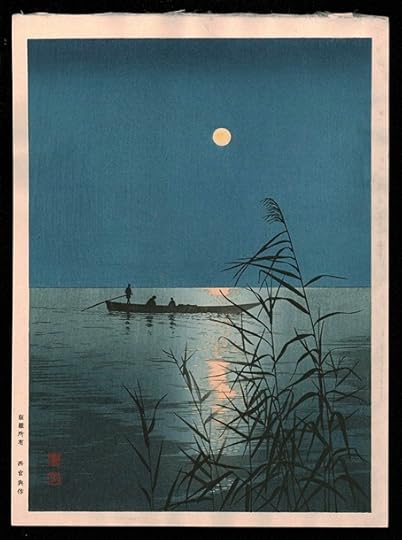

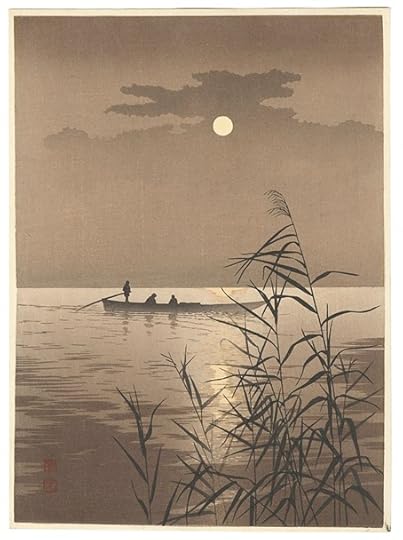

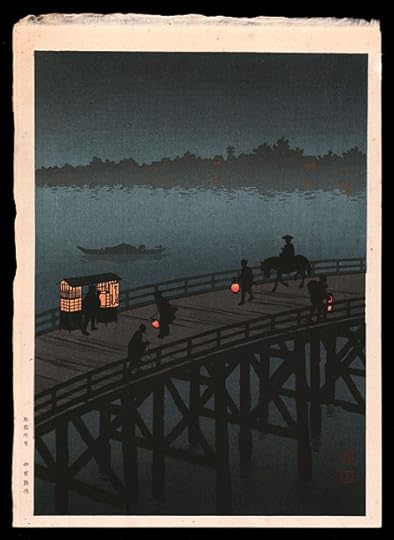

Futamigaura.

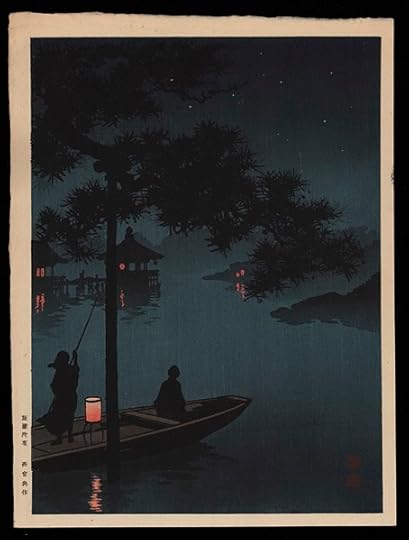

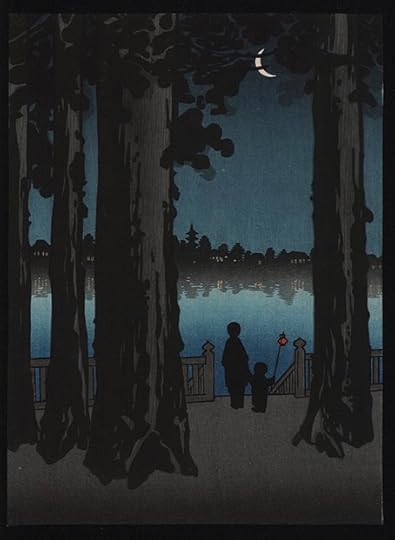

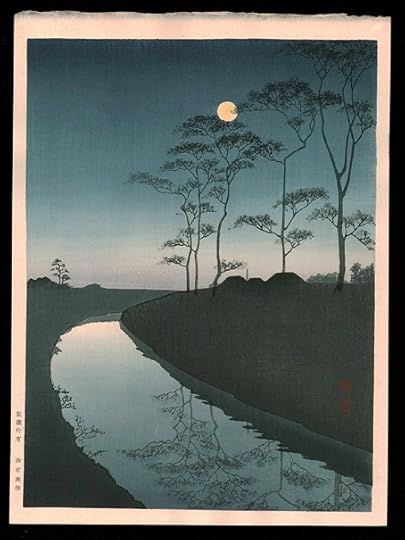

The biographical dates (1871–1946) are apparently uncertain for this Japanese artist about whom little documentation exists. What we do have is the prints he created, a couple of which have appeared here before. Nocturnes were Shoda’s speciality, together with other atmospheric scenes created with carefully graded colouring. As always with prints such as these, I’m in awe of the artist’s ability to create a sense of verisimilitude in the difficult medium of woodblock printing.

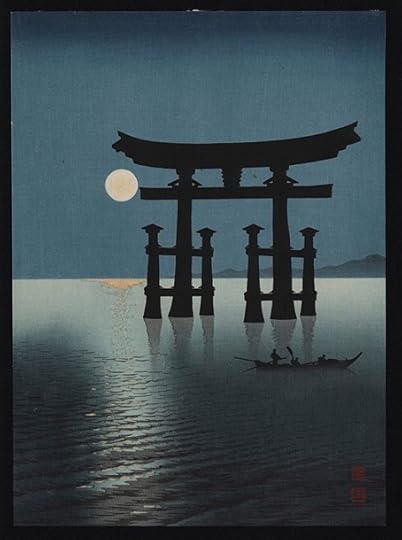

Shrine Gate of Miyajima.

Lake Biwa.

Shinagawa Shore.

Uyeno Park.

A Country Scene (with Moon).

A Country Scene (sepia).

Moonlit Sea (mid edition).

Moonlit Sea (sepia, early edition with clouds).

Ohashi Bridge at Atako.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Cats and butterflies

• Twenty-four octopuses and a squid

• Seventeen views of Edo

• The art of Yuhan Ito, 1882–1951

• Eight Views of Cherry Blossom

• Fourteen views of Himeji Castle

• One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji

• The art of Kato Teruhide, 1936–2015

• Fifteen ghosts and a demon

• Hiroshi Yoshida’s India

• The art of Hasui Kawase, 1883–1957

• The art of Paul Binnie

• Nineteen views of Zen gardens

• Ten views of the Itsukushima Shrine

• Charles Bartlett’s prints

• Sixteen views of Meoto Iwa

• Waves and clouds

• Yoshitoshi’s ghosts

• Japanese moons

• The Hell Courtesan

• Nocturnes

November 10, 2025

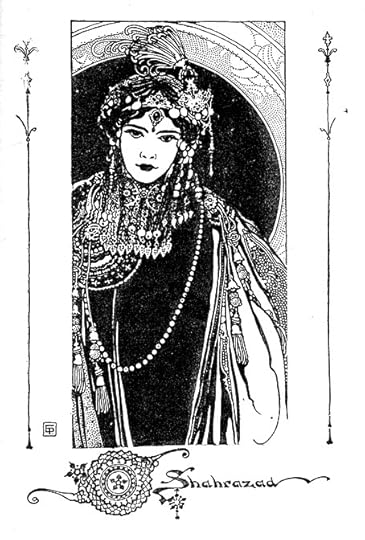

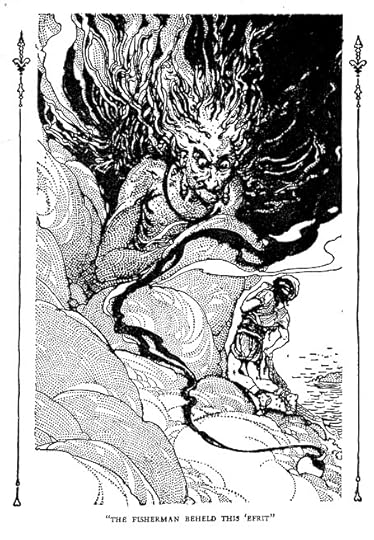

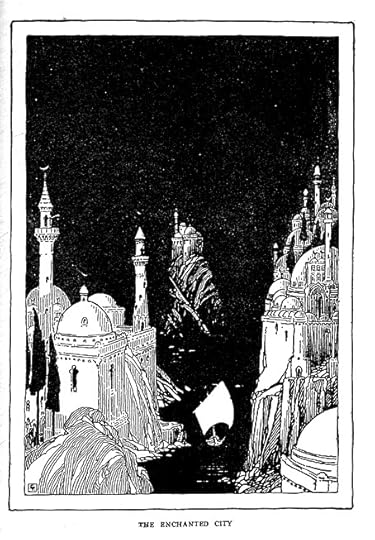

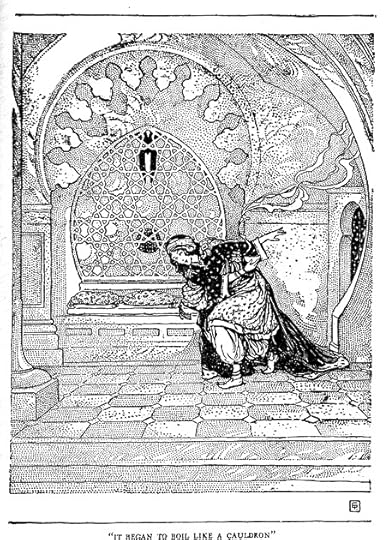

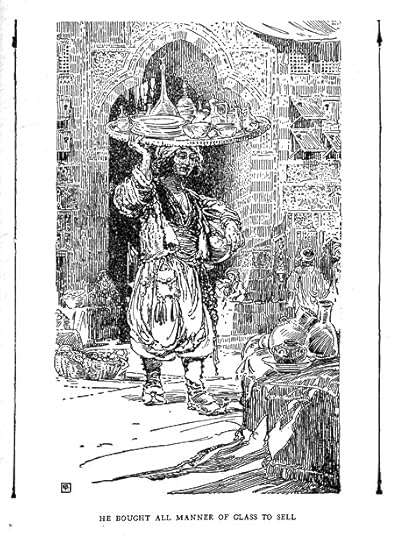

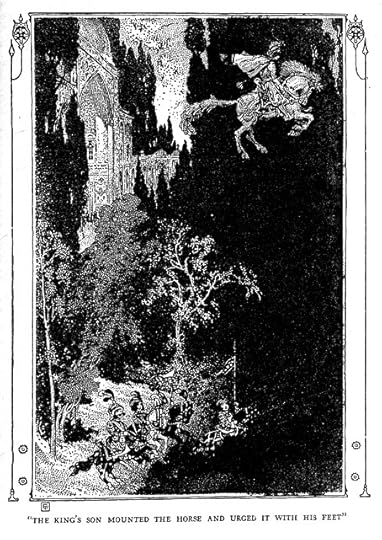

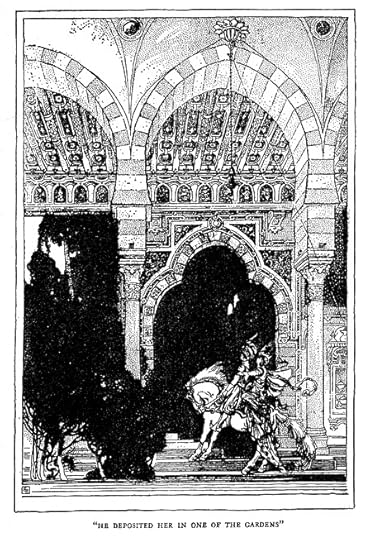

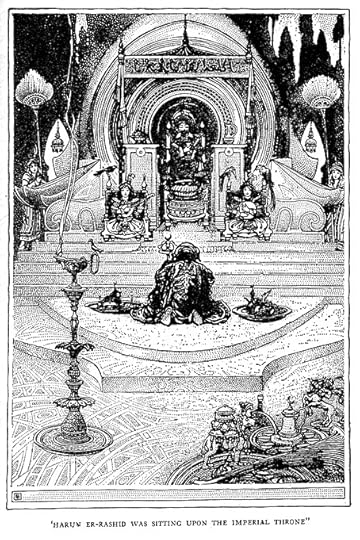

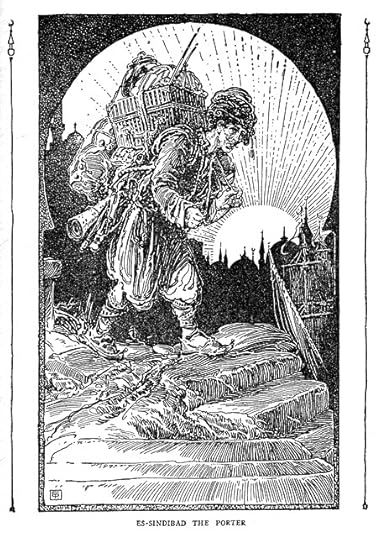

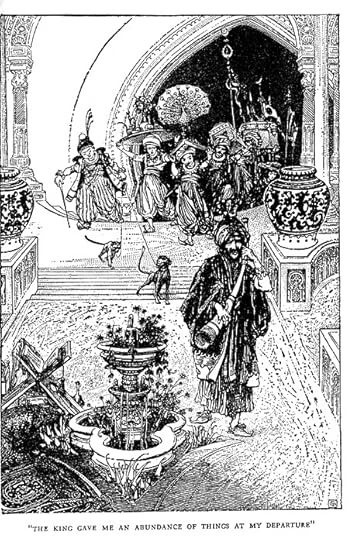

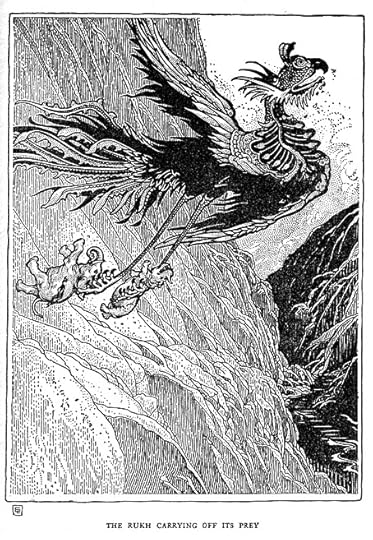

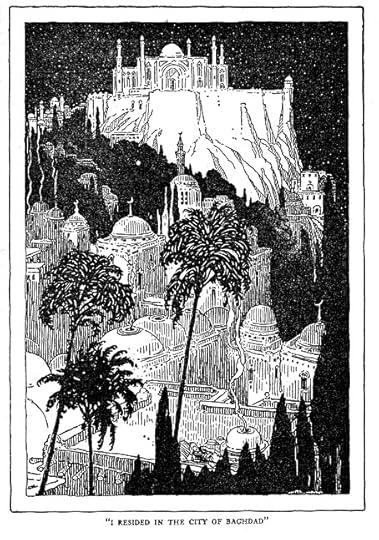

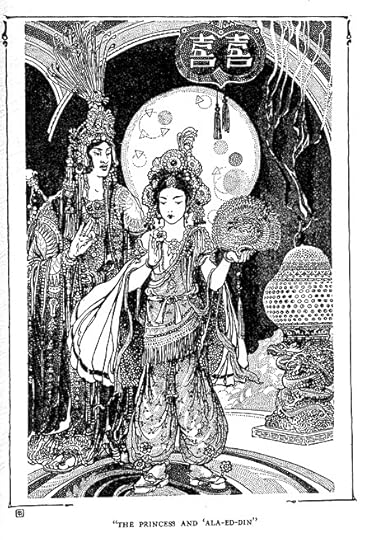

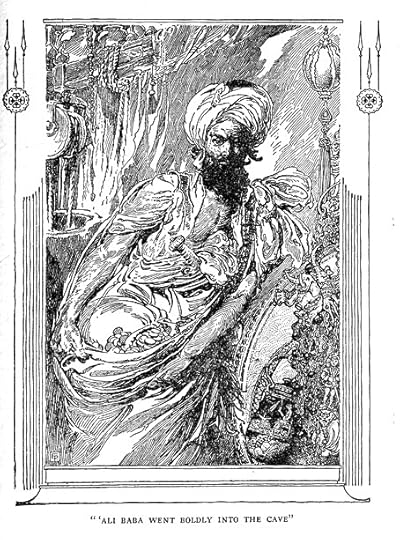

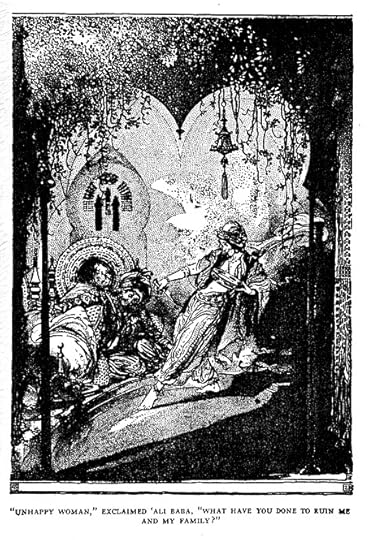

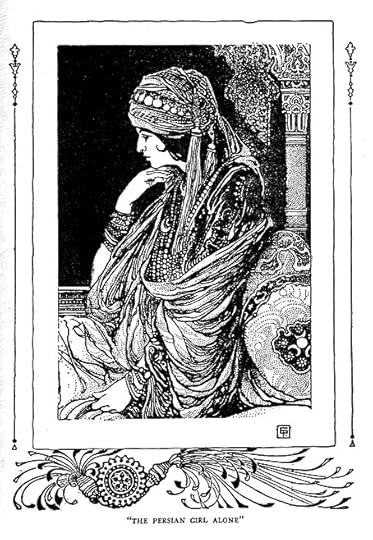

Eric Pape’s Arabian Nights

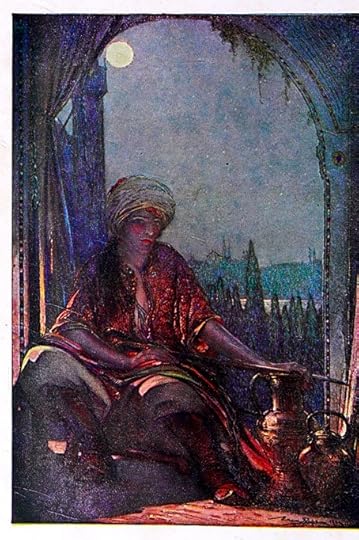

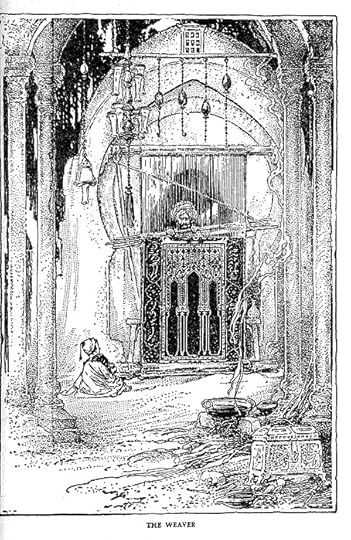

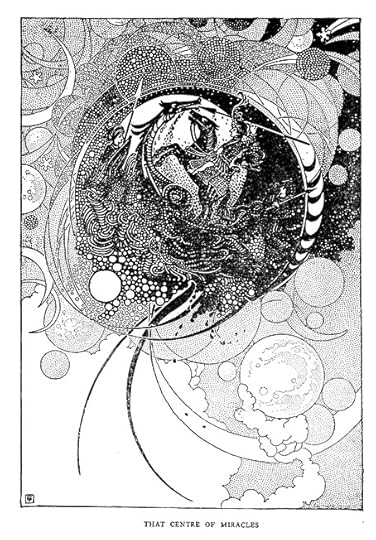

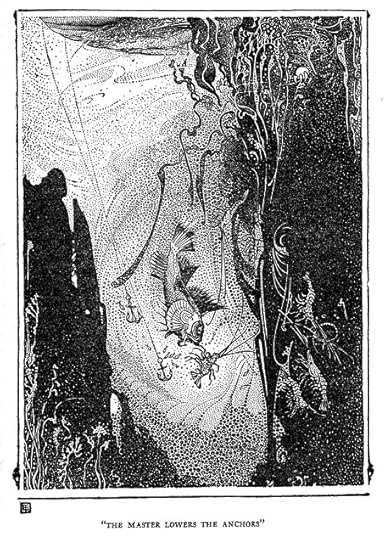

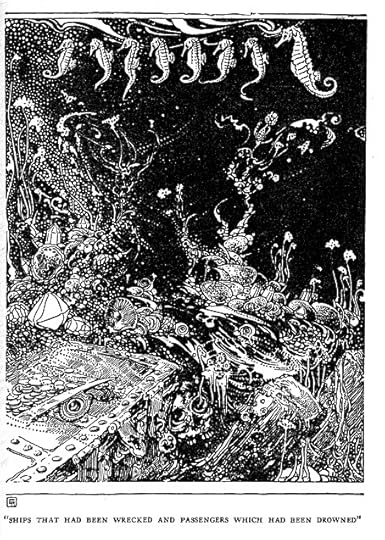

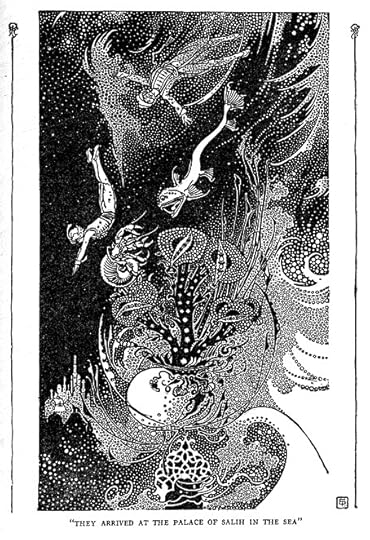

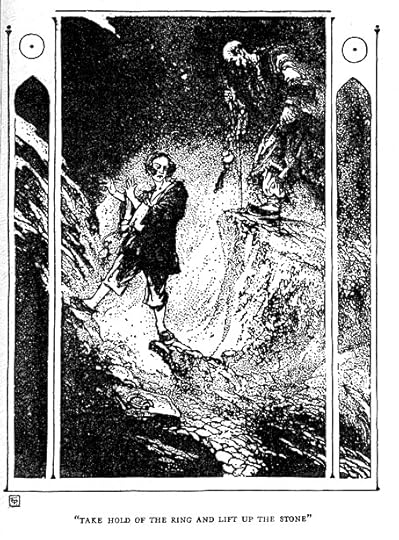

Eric Pape (1870–1938) was an American artist and illustrator who shouldn’t be confused with his contemporary Frank C. Papé, a Briton who was also a popular illustrator. Pape was more of a fine artist—he studied in Paris under Jean-Léon Gérôme—whose magazine illustrations are of that type that favoured realistic scenes using posed models. The illustrations in The Arabian Nights Tales of Wonder and Magnificence (1923) differ enough from his paintings to be taken for the work of another artist, the book being a substantial volume which Pape fills with many full-page ink drawings replete with stippling and detail.

The stories are a retelling by Padraic Colum with an eye to maintaining the flavour of the original (or older) texts. Books like this were aimed at a young readership but Colum begins with an introduction that describes the origin of the tales, and also weighs the pros and cons of the translations by Lane and Burton. In the stories he avoids simplifying the names of the more popular characters, so we have the six voyages of “El-Sindibad of the Sea”, and the tale of “Ala-ed-din” and his wonderful lamp. These gestures of fidelity are matched by Pape’s vignettes, many of are borrowed from Arabian or Persian sources. Pape had spent two years living and working in Egypt—his painting of the Sphinx by moonlight was a product of this period—a factor which may explain why he was offered the commission.

The pictures I’ve selected are mostly the full-page pieces which I’ve adjusted slightly to remove the grey tone of the paper. This copy of the book is a reprint from 1945, a period when print standards suffered from wartime restrictions. Older printings may be better.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Maxfield Parrish’s Arabian Nights

• Thomas Mackenzie’s Aladdin

• More Arabian Nights

• Edward William Lane’s Arabian Nights Entertainments

November 8, 2025

Weekend links 803

Ad for The United States Of America from Helix magazine, 1968.

• American composer Joseph Byrd died this week but I’ve yet to see a proper obituary anywhere. He may not have been a popular artist but he was significant for the one-off album produced in 1968 by his short-lived psychedelic group, The United States Of America. Their self-titled album has been a favourite of mine since it was reissued in the 1980s, one of the few American albums of the period that tried to learn from, and even go beyond, the studio experimentation of Sgt Pepper. The United States Of America didn’t have the resources of the Beatles and Abbey Road but they did have Byrd’s arrangements, together with an energetic rhythm section, an electric violin, a ring modulator, some crude synthesizer components, the voice of Dorothy Moskowitz, and a collection of songs with lyrics that ranged from druggy poetry to barbed portrayals of the nation’s sexual neuroses. The album became an important one for British groups in the 1990s who were looking for inspiration in the wilder margins of psychedelia, especially Stereolab, Portishead (Half Day Closing is a deliberate pastiche), and Broadcast. Byrd did much more than this, of course, and his follow-up release, The American Metaphysical Circus by Joe Byrd And The Field Hippies, has its moments even though it doesn’t reach the heights of its predecessor. Byrd spoke about this period of his career with It’s Psychedelic Baby Magazine in 2013.

• At BBC Future: “The most desolate place in the world”: The sea of ice that inspired Frankenstein. Richard Fisher examines the history of the Mer de Glace in fact and fiction with a piece that includes one of my Frankenstein illustrations. The latter are still in print via the deluxe edition from Union Square.

• A Year In The Country looks at a rare book in which Alan Garner’s children describe the making of The Owl Service TV serial.

• The final installment of Smoky Man’s exploration of The Bumper Book of Magic has been posted (in Italian) at (quasi).

• At Public Domain Review: Perverse, Grotesque, Sensuous, Inimitable: A Selection of Works by Aubrey Beardsley.

• At Colossal: Ceramics mimic cardboard in Jacques Monneraud’s trompe-l’œil ode to Giorgio Morandi.

• At the Daily Heller: The “narrative abstraction” of Roy Kuhlman‘s cover designs for Grove Press.

• New music: Elemental Studies by Various Artists; and Gleann Ciùin by Claire M. Singer.

• Steven Heller’s font of the month is Archive Matrix.

• Sensual Hallucinations (1970) by Les Baxter | The Garden Of Earthly Delights (United States Of America cover) (1982) by Snakefinger | Perversion (1992) by Stereolab

John Coulthart's Blog

- John Coulthart's profile

- 31 followers