Deborah Appleman's Blog

September 6, 2022

In Defense of Teaching Troubled Texts in Troubling Times

You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who had ever been alive. ~James Baldwin

You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who had ever been alive. ~James BaldwinAs the summer wanes, we teachers slowly turn our focus to the beginning of school. For teachers of literature, that often means a trip to the dusty bookroom to decide what texts teachers and students should read together throughout the year. This is, or should be, a complicated decision, a thoughtful calibration of text and context, of who our students are and what kind of reading would serve them best as we encourage their personal and intellectual development. After the obligatory quick count of paperback and perma-bound copies of literary texts, we consider factors of readability, literary merit, and relevance. We re-read state standards and confer with our fellow teachers about our school’s curriculum. This fall, however, there are even more factors to consider as we attempt to make our best pedagogical decisions about what to teach and why.

These are particularly troubling times. We find ourselves in a bitterly divided country with ideological discourse at a feverish peak. Even the very foundations of our democracy seem threatened. Our classrooms need to remain a space where critical thinking is taught, tolerance from different viewpoints is modelled, and the sometimes-harsh truth of our history and literary heritage are not hidden. This year it takes more courage than ever to be a teacher of literature as we anticipate the various challenges that might arise, even from those we consider to be our philosophical bedfellows. Recent challenges to both much-loved classics and newly published works have cast a troubling shadow on the teaching of literature. Pressures from both the right and from the left have prompted the removal of books from school libraries and bookrooms. We teachers need to resist these pressures, regardless of the political direction from which they come.

In a recent NY Times opinion piece Pamela Paul writes:

We shouldn’t capitulate to any repressive forces, no matter where they emanate from on the political spectrum. Parents, schools and readers should demand access to all kinds of books, whether they personally approve of the content or not. For those on the illiberal left to conduct their own campaigns of censorship while bemoaning the book-burning impulses of the right is to violate the core tenets of liberalism. (July 24, 2022)

In my most recent book, Literature and the New Culture Wars: Triggers, Cancel Culture, and the Teacher’s Dilemma, (WW Norton, September, 2022) I discuss this threat to the teaching of literature from both the left and the right and call on teachers to continue to teach troubling and challenged texts, even, perhaps especially, in these troubling times. What follows in an excerpt from the final chapter of the book.

In my most recent book, Literature and the New Culture Wars: Triggers, Cancel Culture, and the Teacher’s Dilemma, (WW Norton, September, 2022) I discuss this threat to the teaching of literature from both the left and the right and call on teachers to continue to teach troubling and challenged texts, even, perhaps especially, in these troubling times. What follows in an excerpt from the final chapter of the book.

These are indeed troubling times. As I write, the world is slowly and cautiously reawaking from a global pandemic, a shuttering and withdrawal which has forced a re-thinking of many of our bedrock social institutions, including schooling at all levels. The basic elements of schooling, the rhythm and dynamics of the classroom, so familiar that we took them for granted, were no longer possible. Remote learning has disrupted many of our educational norms, as traditional ways of teaching and discussing texts became impossible. In many cases, this disruption prompted necessary and healthy reappraisals of what we should be teaching and how we should be teaching it. Although there were clearly some significant technological and pedagogical developments that lead to positive learning highlights, most students and teachers, from kindergarten through graduate school, had an extremely challenging eighteen months of schooling. We were all on edge, teachers and students alike, and none of us had our best selves show up to our virtual classrooms. Perhaps that generalized edginess contributed to the bitterness of this most recent iteration of the complex and confounding culture wars in which we currently find ourselves.

In addition to the myriad of difficulties caused by the pandemic, there was another dramatic kind of social upheaval as well. I write these words from the Twin Cities of Minneapolis/St. Paul, just scant miles away from the site of the murder of George Floyd in May of 2020. I write from the epicenter of an event that taught us all the most brutal and heartbreaking of lessons, that business as usual had to be stopped–on our streets, in our neighborhoods, and, of course, in our schools. This incident spurred, on a global scale, a radical and much needed racial reawakening, one that undeniably added urgency to the increasingly strident calls for a more racially sensitive and socially just literature curriculum.

This radical racial reawaking is only part of our current political, psychological, sociological, and educational landscape. In the United States, we find ourselves in a country that is bitterly divided along political lines, in ways that seem more defined and more antagonistic than ever before. We seem to have moved beyond the divisions of political parties into a kind of cultural tribalism that views contradictory opinions as ignorance, even heresy. Even the question of whether students should be required to wear masks in school or receive vaccinations created bitter divisions between parents of school children, administrators, even governors. In this atmosphere, having a nuanced and informed discussion about something as potentially volatile as critical race theory, for example, seems nearly impossible.

All of these factors—economic uncertainty, fear for well-being in the face of ravaging pandemic, heightened racial sensitivity, and fiercely held political positions have all contributed to the fomenting of the kind of culture wars that have led to the concerns that are addressed in this book—triggers, cancel culture, and a narrow and limiting focus on a kind of extreme version of political correctness or “wokeness.” All of these elements are brought to bear in our classrooms and influence this new era of teaching texts in these troubling times.

I write to argue for a reasoned approach to determine what literature still deserves to be read and taught and discussed, despite some troubling characteristics. It calls for a refocusing of the intellectual and affective work that literature can do and argues that there are ways to continue to teach troubling texts without doing harm.

Of course, there have always been troubling and problematic texts, texts that have been censored or judged inappropriate for public school classrooms because they contain sensitive, even objectionable content, or offensive and anachronistic portrayals of people or whole cultures. In the past, teachers often performed their own individual calculus of whether a text should be taught. They evaluated the “teachability” of texts based on a wide array of student characteristics, the specific properties of the text, including subject matter, use of language, underlying issues, and overall perspective and context, including the relationship of the subject matter to current social and political issues. They made specific and contextualized decisions based on the text, the teaching context, and, most importantly, their students. In these troubling times, however, it seems that was once the province of individual pedagogical prerogative, for better or worse, is now in the court of public opinion at best and mob mentality at worst, as Ann Applebaum suggests (Applebaum, 2021.)

Of course, there have always been troubling and problematic texts, texts that have been censored or judged inappropriate for public school classrooms because they contain sensitive, even objectionable content, or offensive and anachronistic portrayals of people or whole cultures. In the past, teachers often performed their own individual calculus of whether a text should be taught. They evaluated the “teachability” of texts based on a wide array of student characteristics, the specific properties of the text, including subject matter, use of language, underlying issues, and overall perspective and context, including the relationship of the subject matter to current social and political issues. They made specific and contextualized decisions based on the text, the teaching context, and, most importantly, their students. In these troubling times, however, it seems that was once the province of individual pedagogical prerogative, for better or worse, is now in the court of public opinion at best and mob mentality at worst, as Ann Applebaum suggests (Applebaum, 2021.)

To be sure, there is some inarguable value to the heightened awareness and increased scrutiny to particular texts. There is certain content, characterizations and racist and misogynist tropes found within the pages of some previously lauded texts that have rendered them intolerable, so troublesome that they should no longer be taught. In these cases, it is not sufficient to simply ignore the controversy or to dismiss serious and sustained objections to the work or calls for the work to be removed from the curriculum. Silence is acquiescence, an implicit acceptance of problematic portrayals and attitudes. Speaking out against and working to disrupt behavior and attitudes that demean and oppress others is what all educators should be doing. Texts that reproduce harmful social attitudes need to be interrogated, disrupted, and resisted. Clearly there are some texts that simply should not be taught; their historical place on the secondary literature curriculum can no longer be justified as we weigh their assumed literary value and aesthetic significance against the harm, they might possibly do by perpetuating unacceptable social attitudes and anachronistic beliefs. These texts are simply not deserving of our students’ attention. To put it more strongly, they are too potentially harmful to be taught.

Coming to Terms with the Past

To read literature also means that we come to terms with the past, in an honest, full, and non-censored way. Much of the trouble with literary texts has arisen with older, once-classic texts that portray values and beliefs that are anachronistic and best, demeaning at worst. The works of Shakespeare, Mark Twain, Hemingway, and others may fall into this category. Is the solution of their problematic portrayals to not to read their works at all?

To read literature is to learn to read the world in all of its complexities. It calls for a refocusing of the intellectual and affective work that literature can do and argues that there are ways to continue to teach troubling texts without doing harm. Let us consider the larger purposes of a literary education, what it is that we want students to learn from reading texts. In addition to encountering the richness of well-written literature (even though we may not be able to agree on what that is) we also want students to glean a sense of history, to understand the interplay between social context and literature, to witness the evolution of social mores and ideas, to view things from multiple perspectives, to be able to inhabit the perspective of others, to develop empathy, and to acquire some aesthetic sensibilities.

James Baldwin

James BaldwinPerhaps, by teaching, rather than banning, troubled literature, we can help students learn to decipher the world inscribed within the texts we read together and to help them read the world around them. Students can become the “enlightened witnesses” that bell hooks calls for, noting how power and privilege are inscribed all around us, and learning to read both texts and worlds with a nuanced and critical eye. Our students can become, with our help, truly educated in the way James Baldwin envisioned, able to critique one’s own society intelligently and without fear.

Perhaps this is all about trust—trust in the reciprocal act of teaching trust in the reciprocal act of teaching and learning, trust in the ability of teachers to navigate their students through difficult waters, trust in the kinds of rich pedagogical strategies that we have collectively created. Perhaps, most importantly, we need to trust our students, to be able to learn to read words and worlds through a critical eye, to be able to parse out the harmless for the harmful, to read the world for themselves and to develop both the critical strength and emotional resilience to notice harm and to resist it, without it being kept from them by well-meaning but over-vigilant teachers. Perhaps what these troubled times need is for us to continue to teach troubling texts, and trouble the ideologies inscribed therein, rather than cancel or banish them. Our students deserve no less.

Originally Published in the California Educator

April 11, 2021

Stay Free

Monday was Robert’s last class. A big bear of a man, whose gentle demeanor is at odds with his appearance (and probably his record), Robert is being released on Monday, November 24th. This is a rare occurrence, since so many have the guys in our class are serving life sentences. These days, in Minnesota anyway, most life sentences are really life sentences.

Monday was Robert’s last class. A big bear of a man, whose gentle demeanor is at odds with his appearance (and probably his record), Robert is being released on Monday, November 24th. This is a rare occurrence, since so many have the guys in our class are serving life sentences. These days, in Minnesota anyway, most life sentences are really life sentences.

Robert undoubtedly committed a less serious crime than most of his classmates. In order to know why Robert is getting released, I’d have to know what he was in for and I am adamant about not trying to find that out, for any of them.

Robert’s imminent release is bittersweet. What has been perhaps the hardest aspect of this experience has been the deep despair we feel when we think of the men we work with, incarcerated before they were 20, often for crimes the committed or were convicted of, before they were 18. Some are serving multiple life sentences, consecutively, and have ridiculous sounding release dates like 2099. Last week, after Jason asked me if I could request that he be in the next class I taught, for no apparent reason, he said, “I’m 99 plus 17. 17. That’s how old I was when they sent me to the maximum security prison.”

So we respond to Robert’s news with a strange mixture of optimism and wistfulness. His release underscores the impossibility of the eventual release of others. Our understanding that they have committed very serious crimes does not ameliorate this wistfulness, even if one might think it should.

Of course, the other element that renders Robert’s release bittersweet is the ominous threat of recidivism. Nationwide, the average rate of inmates re-offending within 3 years of release is more than two-thirds. To be sure, education in general and higher education in particular has, in multiple studies and metanalyses, been found to the single most effective tool against recidivism. Yet despite these statistics, it is hard to fund higher education and the program in Minnesota has very little money.

Higher education programs for the incarcerated are a tough sell, but it might be the only thing that works.

During our class break, I ask Robert if he would mind if I announce that tonight is his last class as well as explain the reason why. Robert says it’s fine. “I’m gonna miss you all. I mean it,” he says.

Right before class ends, I make the announcement. The class applauds, some looking at Robert, others looking down. Robert stands, and bows.

The guard comes to the door to signal the end of class. As the men straggle out, Mike, a quiet guy who keeps to himself and doesn’t say much either to us or his fellow inmates, walks over to Robert.

The guard comes to the door to signal the end of class. As the men straggle out, Mike, a quiet guy who keeps to himself and doesn’t say much either to us or his fellow inmates, walks over to Robert.

“Hey, man, I know I didn’t get to know you very well, but I admired how you represented yourself in this class. I wish I’d gotten to know you better, and I wanna wish you the best of luck.”

“Thanks,” says Robert. They shake hands.

“I mean it, man. Go out there, represent, do your thing. But, mostly, for all of us, stay free, man. You gotta stay free.”

EXCERPT , Words No Bars Can Hold , by Deborah Appleman

EXCERPT , Words No Bars Can Hold , by Deborah Appleman

February 12, 2021

The School-to-Prison Pipeline

The School-to-Prison Pipeline

The School-to-Prison Pipeline

I remember, when I was a high school teacher, working with students who I thought were walking a tightrope between going to college and going to jail. Up to this point, my teaching life has insulated me so that I’ve only seen the students who ended up in college. Now I see the other side, the ones who were not caught by the “catchers in the rye” we teachers sometimes fancy ourselves to be. Now I see the ones who were harmed, rather than helped, by a system that contributed to their senses of failure and their self-images as outlaws.

There are students in my class who were picked up at their high school by the police, who committed crimes as 15-year-old runaways, who have moved from foster home to juvenile detention facility to a maximum security prison, who have grown from boys to men… in prison. Many of them are serving life sentences, with no possibility of parole, for crimes they were found guilty of while they were still adolescents.

There is much talk about the school-to-prison pipeline. Briefly, many youth advocates contend that the over-policing of urban schools, racial profiling of “at-risk” students, zero tolerance disciplinary policies leading to suspensions and expulsions, and low academic expectations for certain students create a direct pipeline to our nation’s prison system for some youth.

There is much talk about the school-to-prison pipeline. Briefly, many youth advocates contend that the over-policing of urban schools, racial profiling of “at-risk” students, zero tolerance disciplinary policies leading to suspensions and expulsions, and low academic expectations for certain students create a direct pipeline to our nation’s prison system for some youth.

While some students in our class did receive decent educations, in both public and, private schools, many testify to a difficult school experience that only amplified their challenges at home.

LaVon, writes of a “miseducation”, so commonly experienced by African-American males:

As I grew older I began to learn about myself, who the real me really was. I started educating myself in ways to become a better man, in how to become a so-called black man. I started recognizing the miseducation I was receiving from my schools for what it was. It was this misguided message that propelled me to seek knowledge elsewhere.

Chris writes of being misdiagnosed with a speech impediment because of his accent:

Very early on I was diagnosed by the school as having a speech impediment because they believed that I had an issue pronouncing my R’s correctly. I can recall the classes making me feel as though something was wrong with me and added to my insecurities speaking up which in turn developed a mumbling problem. I cannot remember ever feeling as though these ‘special’ classes ever helped. Thinking back, I believe my lean towards slang was orchestrated to hide my ‘impediment’ and give the appearance that I was in more control.

Many educators have gathered in conferences around the country to begin discussions of “dismantling the school to prison pipeline.” Schools are beginning to review zero-tolerance discipline policies, how students are sorted into special education, and ways in which negative beliefs about particular students are communicated both verbally and nonverbally.

Some schools are beginning to change both their practices and their cultures. For example, in an admittedly schmaltzy but gutsy move, The Dallas Public Schools tried to change the tone of the discourse around students by having a young African American male serve as their keynote speaker. He began his speech by asking the auditorium of educators, “Do you believe in me?

Some schools are beginning to change both their practices and their cultures. For example, in an admittedly schmaltzy but gutsy move, The Dallas Public Schools tried to change the tone of the discourse around students by having a young African American male serve as their keynote speaker. He began his speech by asking the auditorium of educators, “Do you believe in me?

It is much more likely that those of you reading this blog can affect change within our current public school system rather than within the walls of a “correctional facility.” I think awareness of the carceral state needs to be a part of every teacher training program. If I only I knew as high school English teacher what I have learned this past year teaching in the prison.

January 22, 2021

Celebrating Poetry, From the Outside In

Last Wednesday, in addition to rediscovering hope for our country and for democracy, much of the world discovered the power of the spoken word. Through the brilliant of Inaugural Poet Amanda Gorman, we were able to be inspired by her words, as she recited “The Hill we Climb. ”

Last Wednesday, in addition to rediscovering hope for our country and for democracy, much of the world discovered the power of the spoken word. Through the brilliant of Inaugural Poet Amanda Gorman, we were able to be inspired by her words, as she recited “The Hill we Climb. ”

For some, this might have been an introduction to the power of spoken word poetry. For others, it  was a glorious validation of the power of an art form long cherished by youth poets, performance artists, and spoken word poets . For the incarcerated writers who I teach, spoken word has long been a favored art form, an important artistic salvation. As I wrote about my students in Words No Bars Can Hold and featured some of their work, I always regretted that I couldn’t render their voices on the page as they spoke their worlds. Now, through the brilliance and artistry of Emily Baxter, their words are offered in a project called Seen, which is a collaboration of We Are All Criminals and the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop.

was a glorious validation of the power of an art form long cherished by youth poets, performance artists, and spoken word poets . For the incarcerated writers who I teach, spoken word has long been a favored art form, an important artistic salvation. As I wrote about my students in Words No Bars Can Hold and featured some of their work, I always regretted that I couldn’t render their voices on the page as they spoke their worlds. Now, through the brilliance and artistry of Emily Baxter, their words are offered in a project called Seen, which is a collaboration of We Are All Criminals and the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop.

I’d like to offer the works of two of the most accomplished spoken word artists I know, and invite you to listen to them read their words.

https://www.weareallcriminals.org/bino/

https://www.weareallcriminals.org/jeff/

While you are there, please check out the work of some of the students who are featured in my book:

LeVon, C. Fausto, Fong, and Zeke

In their own way, these resilient souls and gifted poets are heeding Amanda Gorman’s advice as she explains:

Amanda Gorman

Amanda GormanWhen day comes, we step out of the shade aflame and unafraid. The new dawn blooms as we free it. For there is always light. If only we’re brave enough to see it. If only we’re brave enough to be it.

December 14, 2020

The Season of Small Gestures of Compassion

The pandemic has made the last year extremely difficult for all of us, but conditions in our prisons have gone from terrible to intolerable. Several Minnesota prisons have become hotspots of infection, and all programming and visitation has been halted. Many of the incarcerated have spent most of the last 10 months in their cell. Knowing that, I reached out out to one of the students I profile in Words No Bars can Hold. Here is a bit of background about LaVon, as I described him in the book:

The pandemic has made the last year extremely difficult for all of us, but conditions in our prisons have gone from terrible to intolerable. Several Minnesota prisons have become hotspots of infection, and all programming and visitation has been halted. Many of the incarcerated have spent most of the last 10 months in their cell. Knowing that, I reached out out to one of the students I profile in Words No Bars can Hold. Here is a bit of background about LaVon, as I described him in the book:

LaVon has become a man in prison. Arrested before he was 18 on the steps of his city high school for a gang-related gunfight, LaVon has a sentence of more than two lifetimes. LaVon was in the very first class I taught more than a decade ago and has been in every one since. He approaches learning with such seriousness of purpose, with such reverence, that he alone can make the classroom seem holy. In our first class, an introduction to literature course, he wrote an original poem to complement every academic essay. He finished his GED in prison and has been pursuing education ever since. He doesn’t care about earning a degree–his credits are scattered haphazardly across a variety of on-line institutions and disciplines. He wants to learn things, he once told me, not earn things.

LaVon views writing as a vehicle of self-improvement, of bettering himself, of trying to become the man he hopes he can someday be. He believes in transformation, even if it will only take place within the walls of the prison. His commitment to self-improvement is unshakeable, and as with his writing, he is the only audience that matters. He also sees it as a way to heal and to come to terms with the life he is living behind bars. With no discernable way out, LaVon creates a community in prison. In many ways it has become his city, his neighborhood, his world.

LaVon views writing as a vehicle of self-improvement, of bettering himself, of trying to become the man he hopes he can someday be. He believes in transformation, even if it will only take place within the walls of the prison. His commitment to self-improvement is unshakeable, and as with his writing, he is the only audience that matters. He also sees it as a way to heal and to come to terms with the life he is living behind bars. With no discernable way out, LaVon creates a community in prison. In many ways it has become his city, his neighborhood, his world.

In many ways LaVon exemplifies what can only be described as the purity of literary pursuit in prison. Literacy is not a means to any kind of instrumental end-not vocational, not educational in the traditional sense of attaining degrees through post-secondary education. LaVon will not be leaving prison. He writes to heal himself, to map the contours of his interior landscape and in doing so to re-chart it.

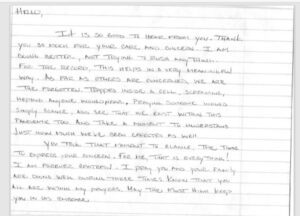

Knowing how isolated things have been in the prison I sent a simple message of greeting to LaVon.

Here’s what I received in return:

“Hello, It is so good to hear from you. Thank you so much for your care and concern. I am doing better, not trying to rush anything. For the record, this helps in a very meaningful way. As far as others are concerned, we are the forgotten. Trapped inside a cell, screaming, hoping anyone would hear. Praying someone would simply glance, and see that we exist within this pandemic too. And take a moment to understand just how much we’ve been effected as well. You took that moment to glance, the time to express your concern. For me, that is everything! I am forever grateful. I pray you and your family are doing well during these times. Know that you all are within my prayers. May the most high keep you in his embrace. LaVon

I was deeply moved by how much such a small gesture of compassion meant to LaVon. It is a good lesson for all of us this time of year.

“Reading it, we learn so much about the power of writing, about teaching, about what education makes possible, and about the urgent human capacity to define who we are.”

“Reading it, we learn so much about the power of writing, about teaching, about what education makes possible, and about the urgent human capacity to define who we are.”– Mike Rose, author of Back to School: Why Everyone Deserves a Second Chance at Education

October 27, 2020

Before I Was Anything

“Before I Was Anything”

A Poem by Zeke Caligiuri

Before I was anything

I was an abstraction, sound waves

moving through glycerin.

Before the effigies of my generation

in orange jumpsuits started tattooing

cuffs on their wrists, bars on their hearts,

I was a red jumpsuit

running under evergreens

on the edge of a mountain.

Back then, I was a story

they would tell me my whole life.

Before I was anything

I was an open school education.

Cracks big enough to climb down into

strange fleeting minutes alone,

subterranean stairwells, where feelings

as vacuums consume

moving photographs of moments

compressed between years, bound

to one another––the ones they said

would come eventually and go away

so quickly.

That was before

City Center was Mecca

and kids made Hajj

stealing Girbauds from Dayton’s

and looked at all the people they knew

on the wall in the holding tank

in the basement.

Zeke

Zeke grew up as the adored only child of a middle-class family. His home life was relatively stable, and he didn’t lack for any material needs. Yet, as Abraham Maslow reminds us, food, shelter and safety are merely basic needs, and don’t guarantee self-actualization, or, in other words, a state of satisfied well-being (Maslow, 1943). Zeke’s basic needs were always met; his parents saw to that, but their love and care weren’t enough to keep him out of prison.

Zeke Caligiuri, Poet, Essayist , Author

Zeke Caligiuri, Poet, Essayist , AuthorAlthough he is one of the most intellectually gifted students I have ever taught, anywhere, Zeke barely graduated from high school. High school completely bored him and he began to skip classes and spend more time on the streets, falling in with a tough, streetwise crowd. Depression also took hold or, as Zeke himself explains, he fell in love with the grays. That depression remained undiagnosed and untreated until his first stint in jail.

A series of unsuccessful jobs, recurring depressive episodes, broken relationships, and shady associates in early adulthood led him to being in the wrong place at the wrong time. A robbery gone bad, an innocent life needlessly lost, and a fouled-up plea led him to a sentence of 25 years. He has been in prison for 20 of those years. In that time, Zeke’s mother, father and grandmother have all died, and with his parents’ early untimely and unexpected deaths, his isolation has made even the harsh reality of incarceration more difficult. He has no family to visit him and many of his former friends have lost contact with him over time.

Education has been a central focus of Zeke’s incarceration, even though he has had many distractions and impediments in his pursuit of education. He has earned an AA degree and his working his way through a Bachelor’s degree. He has learned the value of reading:

There were books I read that influenced my sensibilities. Steppenwolf appealed to some of my very dark experiences with loneliness and isolation and depression. Some books I read illuminated associations I had with injustice and individuals’ confrontation with power, and some just taught me about the nuance of individual human lives. The books I read made me want to write things that touched people in the same ways.

Motivated by his reading as well as his desire to communicate his “experiences with the world” Zeke began to work seriously on his writing:

Writing offered me a conduit to communicate my experiences with the world. It was not therapy but it could speak for me in ways nothing else could. It also offered me some evidence that I was still a feeling and empathetic human being. When I was first able to publish, it offered a way for people I had lost contact with years before to reconnect. It was the way I could tell them where I had been. But as far as my break-me-down-to -my purpose reasons for writing: Writing was for me an act of defiance. I lived an entire life so deeply defined by roles hidden under varying levels of authority. It was the only way I could show that I hadn’t been beaten by these people, even when I was so tired and worn down by being a prisoner. Also, writing for me was humbling, giving me space to confront al of the conflated parts of our being-ego and narcissism, pride exaggerated purpose. Through it, writing also became an act of endearment to my family, and to my city.

Zeke has been writing prose and poetry since early into his incarceration. A multi-genre, multitalented writer, he has won several Pen writing awards for poetry, short story and memoir. He recently published a book-length memoir with the University of Minnesota Press, one that garnered the praise of literary luminaries like Joyce Carol Oates and Jimmy Santiago Baca. Becoming a published author held a particular salience for Zeke. He writes:

Zeke has been writing prose and poetry since early into his incarceration. A multi-genre, multitalented writer, he has won several Pen writing awards for poetry, short story and memoir. He recently published a book-length memoir with the University of Minnesota Press, one that garnered the praise of literary luminaries like Joyce Carol Oates and Jimmy Santiago Baca. Becoming a published author held a particular salience for Zeke. He writes:

There was for a while a transcendence from my incarceration; an idea that I had outperformed the strictures of this place, regardless of what the system or the nameless blob of power that governed over me expected of me. There is power in that feeling, and empowerment is what men in these places need most; the sense that they are capable human beings who can accomplish larger goals in their lives.

For Zeke, writing is a way to preserve his sanity, his humanity. He writes:

Writing gave me a voice. It made me a writer, a student, a man, an individual outside statistics hidden somewhere. It made me a better son; able to replant seeds over the things I tore down a long time ago.

Writing became a way to work through his considerable grief, to make sense of his own narrative and to alter it by retelling it. He tells me that writing is the only thing that hasn’t been stolen from him. Still, it also reminds him of his powerlessness. Despite his accomplishments as a writer, and the pride that the Department of Corrections, including the commissioner, takes in those accomplishments, Zeke often finds himself without access to a typewriter or word processor. An unexpected stint in a county jail left him even without a pen. His current job assignment is to fold mylar balloons in an overnight shift. He then sleeps through the precious typing hours that are available to him in the computer lab.

Zeke is not only a writer; he is a student of writing and he invariably finds himself in violation of the ten book limit that the prison imposes on each inmate. He doesn’t want to be known as an outstanding prison writer; he wants to be known as an outstanding writer, “period.”

He believes that his words and the critical and affective reception they garner will allow him to travel to places he can’t yet go. It is a freedom of movement, a carpet ride of prose. His work is an imperative, it demands attention even as he is ignored.

Perhaps most importantly, and the reason why he allows his work to appear in this volume, his words, which no bars can hold, force us to think collectively about the ways in which human capital languishes in the name of just punishment. I think of not only the written words of Zeke, but of the millions of words that remain unwritten by so many of their fellow inmates.

This is Where I am by Zeke Caliguiui

This is Where I am by Zeke Caliguiui

University of Minnesota Press

A look at the life that landed the writer in prison and a lost world recaptured

This is the memoir of Zeke Caligiuri, who grew up South Minneapolis in the 1990s when the city was dubbed “Murderapolis.” Currently in prison, Zeke’s story is a clear-eyed account of how he got from there to here, how a boy who had every hope went from dreaming of freedom to losing it, along with nearly everything and everyone he loved.

“An intimate, searing, and important document that makes no excuses for its subject’s life-choices and is all the more powerful for its honesty.”

—JOYCE CAROL OATES

October 6, 2020

Sticks and Stones, Essays from Incarcerated Students

We’ve all heard the saying “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names may never harm me.” Yet most of us have experienced the power of language to harm us.

We’ve all heard the saying “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names may never harm me.” Yet most of us have experienced the power of language to harm us.

For one of my prison classes, I instructed the incarcerated students to write a personal essay of two to three typewritten or 3-4 handwritten pages recalling an incident where they were either the target of hurtful language or were the instigator.

I told them to make certain that in they discuss the following:

the incident itself, including the participants, history, and the language involved

personal, social, historical, and cultural reasons why the language was so hurtful

the consequences of the use of that language

current reflections on the significance of the incident

We arranged ourselves into a big misshapen circle, and each student was asked to speak about what he wrote about, although they did have the opportunity to pass, and two or three did. One by one, the students described a time, sometimes from early childhood, sometimes from the time they have spend in prison, when words created hurt. Several students described the first time they heard the n word; others from the opposite side of the circle confessed to when they first used it. Ross talked about hearing the word “whiteboy.” As he described his early childhood in a foster home, we could see his classmates soften toward him. Victim stories and perpetrator stories were about evenly split. We also got several incarceration stories-the incident that landed them in prison or the incident that foreshadowed the incident that landed them in prison.

The class felt like a group meeting. There were tears, and there was laugher. Two students discovered they had both used the same title “Why Me?” and chuckled about it. Everyone listened to each other’s stories with an earnestness and an empathy that they don’t always demonstrate for their opposing political and intellectual positions.

Several students took us up on our invitation to experiment with non-traditional forms. Ezekiel wrote a short story; Terrell wrote a poem. The pain, hurt, and anger rose from nearly every page like storm clouds. Many expressed contrition, shame and embarrassment. Two asked that we didn’t share their work in any way because what they wrote was simply too painful. “It’s for your eyes only, as my teachers,” one wrote.

Others were eager to share their stories. They want people to know they have been hurt. They want people to know that they have changed. They want people to know that they are sorry for the hurt they have caused. They want people to know that they have learned that language is power and they learned that the hard way.

Jason wrote about the day he learned his mother died. Check out his note of apology at the bottom of the page-he wasn’t sure his essay fit the assignment.

Jason wrote about the day he learned his mother died. Check out his note of apology at the bottom of the page-he wasn’t sure his essay fit the assignment.

Looking back on it now, those words impacted my life more than any others because of the turn-for-the-worst that my life would take after that day. After that day I just continued to spiral downward until I reached prison. Without my mom to guide me, I was on my own. I ended up having to live with my dad, and he continued to not be around much. Ever since that day I’ve basically been just lost trying to find my way on my own.

A lot of the mistakes that I’ve made can be attributed to not having the guidance and structure that my mom would have provided. I know that had she not died, I would not be in prison right now, and I definitely wouldn’t be heavily tattooed. That sentence or two affected my life deeper than someone calling me cracker or honky ever could. The words that were used to tell me that my mom had died were a lot more than just words. Those words were a turning point towards the rest of my life.

Jason’s additional handwritten note of apology:

I wrote about a situation that hurt me the most with words. If you’d like me to re-write the paper about a situation involving insult, just let me know. I’ll be happy to do it.

Joe mourns the loss of a relationship, swearing he has changed:

Joe mourns the loss of a relationship, swearing he has changed:

The pain that has resulted from these words still echoes through me to this day. The effect of severing communications – which these words represent – has created a chasm between us that I can find no way to circumnavigate, and trust me I have tried. I have spent sleepless nights pondering why such an obstacle even exists, and I have come to realize that the true travesty in this situation is that the man that she was angry with, does no longer exist – for the fact is I have changed, but sadly, now she has no way of knowing this. If we cannot communicate, I have no way of conveying or proving that today I am not the same man I was yesterday. And every morning when I awake, I say a prayer that one day she will allow me to speak with her and with my children once again.

Jon remembers the racial slurs on the playground of his St. Paul youth

Jon remembers the racial slurs on the playground of his St. Paul youth

We Could Have Been Friends

Have you ever seen an Asian man as a main character in a movie in which he wasn’t portrayed as knowing martial arts, being a homosexual, or a perverted nerd? Ever since I was born these media stereotypes of Asian males are all that I’ve seen and heard in mainstream America. From today’s Jacky Chan to the days of Charlie Chan this skewed image has been reinforced over and over again. At times they didn’t even let an Asian man play an Asian man in the movies. So it is no surprise that growing up I was always bombarded with the question, “Do you know kung fu?” or “Do you know karate?” Along with that I’d also get a Bruce Lee esq “Whaaw!” and a karate chop in the air. The most offending things to ever happen to me didn’t come from a movie or a question. This incident happened to me on the joyful and sometimes cruel playground of my neighborhood.

And Brian eloquently recounts a harsh interaction with his stepmother over his grades, claiming that at that moment, he began to spiral into the person who would land in prison… for life:

And Brian eloquently recounts a harsh interaction with his stepmother over his grades, claiming that at that moment, he began to spiral into the person who would land in prison… for life:

…I felt the stings there on my bed, and I continued to feel those lashes for a long time after the eruption. My state of mind had to be rebuilt, and a new cornerstone had to be carved out of a new ideology. What once was, was no more. It was difficult to decipher that all of this devastation took place over a couple of letters on a piece of paper that didn’t constitute how hard I strived to do my best, and not just academically.

As I look back on this important piece of my childhood, I realize how vulnerable I was to all types of attacks, and part of it may have to do with that ambient innocence of a child. Even now I am vulnerable to verbal attacks because I take everything directed at me to heart; as I’ve stated before, I wear my heart on my sleeve, unarmored, and statements weigh heavily on my mind thoroughly before discarded. Because of what was said that day, the gap between my step-mother and me grew into a canyon, and any unkind words that were said from then on had to float across that chasm and came to me only as echoes. It’s a feeling that I never want to feel again and I never want to make another person, especially one that I care dearly for, have to experience that agony. I realize the importance of the way we talk to each other and communicate with one another, and how damaging taboo language and hate speech can be. The consequences go far beyond that of physical injury; the harm can be irreparable and one’s psyche and emotional wellbeing can experience severe affliction. The wound may scab over, but a ghost of that wound could always haunt the heart and mind. I don’t think talk is cheap; on the contrary, it comes at a very high price.

Those wounds do continue to haunt, but perhaps writing and talking about them provides an opportunity for both reflection and healing.

Blog Excerpt originally published in “Words No Bars Can Hold” by Deborah Appleman

Blog Excerpt originally published in “Words No Bars Can Hold” by Deborah Appleman

Buy the Book

September 9, 2020

Walking the Tightrope Between Jail and College

At 7:30 AM on a still cold March morning, I wait inside the entrance of an urban public high school, with Patrick, a ninth-grade English teacher on one side of me and a security guard on the other. We are waiting for the arrival of Eli, my formerly incarcerated student, who has agreed to spend the day at the high school. Eli arrives exactly at 7:30, dressed immaculately in a three-piece gray suit. I berate myself silently for worrying that he might be late.

At 7:30 AM on a still cold March morning, I wait inside the entrance of an urban public high school, with Patrick, a ninth-grade English teacher on one side of me and a security guard on the other. We are waiting for the arrival of Eli, my formerly incarcerated student, who has agreed to spend the day at the high school. Eli arrives exactly at 7:30, dressed immaculately in a three-piece gray suit. I berate myself silently for worrying that he might be late.

Together, Eli, Patrick, and I make our way through the crowded halls; nearly every student we see is a student of color. The ninth-grade students have been reading Walter Mosley’s Always Outnumbered, Always Outgunned, an adolescent novel about the challenges of adjustment faced by an African American ex-convict. Patrick, an extraordinarily gifted veteran teacher committed to the urban youth he serves, has become increasing worried about the precarious pathway of many of his students. They seem to be gingerly walking the tightrope between jail and college. Many have experienced the ravages of incarceration in their own families–fathers, brothers, uncles, even sisters and mothers. Patrick hopes to interest them in learning in ways that so many of my incarcerated students were not. He wants to engage them in literacy, in reading texts and writing about them. He also wants his literacy lessons to be relevant.

During my regular visits to Patrick’s classroom he and I hatched a plan, inspired in part by a student named Henry. Henry is bright and thoughtful, but he is flunking out of ninth grade. He is frequently absent, tardy to class when he is present, his sweatshirt hood hiding his face. He never participates in class. Patrick is worried about Henry, and so am I. He seems destined to drop out of school. The enticements of the streets beckon. If only we could fashion learning to capture Henry before the police do.

Patrick decides to teach the Walter Mosely book and asks if I’d like to come speak to his classes about my experiences teaching in the prison. Mindful of Erica Meiner’s (2007) helpful conceptualization of the White Lady Bountiful, I tell Patrick that my speaking to his students might be no more effective than Nancy Reagan’s “just say no” campaign in the 80s. I am not a messenger with any credibility.

But Eli is. Incarcerated at 15 for over 17 years before managing to have his life sentence overturned, Eli knows the consequences of poor choices only too well. In addition to describing the realities of prison, with which the students are almost morbidly fascinated, he also speaks passionately about the power of education. He falls into the cadence of a preacher and uses a call and response to rouse the ninth graders.

“Hey y’all, I wouldn’t be here without education. Say education.”

The students respond, “education.”

“I needed to release the power of my own intellect. Say intellect.”

“Intellect.”

“I needed to learn that literacy is the key. It was the key to my freedom. Say freedom.” “Freedom.” Henry looks up.

“Brother, I am speaking to you. Do you hear me?”

Henry nods slowly.

“I am out here to make sure you don’t go in. It’s what I am dedicating my life to. Hear me, little brother, stay free. Say in school. Say I will, say I will, y’all.”

“I will.” Henry mouths the words.

Eli, Patrick and I all know that it will take more than a one-time visit by an ex-convict to keep Henry out of prison. But as much as this story is about Henry, it’s about Eli, too. Eli has recrafted himself from a discarded shell of a man known only by an ID number, written off by everyone except himself, to a vibrant example of the power of literacy behind bars.

Yes, prisons are inhabited by some who have not learned any path besides violence, but they are also filled with men like Eli, who will embrace and return the lessons of literacy, if we are willing to offer them.

Excerpt from “Words No Bars Can Hold” Literacy Learning in Prison. (W.W Norton & Company) Excerpt reprinted in The Crossing Arts Alliance Currents, August 2020, Volume 20, Issue 3

Excerpt from “Words No Bars Can Hold” Literacy Learning in Prison. (W.W Norton & Company) Excerpt reprinted in The Crossing Arts Alliance Currents, August 2020, Volume 20, Issue 3

August 18, 2020

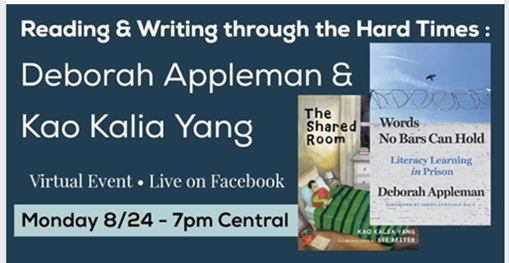

Live Book Discussion with Deborah Appleman and Kao Kalia Yang

Reading and Writing through the Hard Times: Deborah Appleman presents Words No Bars Can Hold, with Kao Kalia Yang

Reading and Writing through the Hard Times: Deborah Appleman presents Words No Bars Can Hold, with Kao Kalia Yang

Monday, August 24, 7:00pm Magers And Quinn Booksellers Facebook Page

Ever wondered about the ability of literature “to empower inmates who are too often dismissively diminished by society”? Join Deborah Appleman as she discusses her book, in which she shares her experiences teaching creative writing to high-security prisoners. She will be joined by Kao Kalia Yang, who will also discuss her new book The Shared Room!

Tune in HERE on Monday, August 24 at 7:00pm Central Time.

Words No Bars Can Hold provides a rare glimpse into literacy learning under the most dehumanizing conditions. Deborah Appleman chronicles her work teaching college-level classes at a high-security prison for men, most of whom are serving life sentences. Through narrative, poetry, memoir, and fiction, the students in Appleman’s classes attempt to write themselves back into a society that has erased their lived histories.

Buy Words No Bars Can Hold HERE

Deborah Appleman lives in Minnesota and is the Hollis L. Caswell Professor of Educational Studies and director of the summer writing program at Carleton College. Since 2007, she has taught language, literature, and creative writing courses at a high-security prison for men in the upper Midwest.

Deborah Appleman lives in Minnesota and is the Hollis L. Caswell Professor of Educational Studies and director of the summer writing program at Carleton College. Since 2007, she has taught language, literature, and creative writing courses at a high-security prison for men in the upper Midwest.

Kao Kalia Yang is a mother of three and a writer of both adult and children’s literature. She is author of A Map into the World, the award-winning memoirs The Latehomecomer: A Hmong Family Memoir and The Song Poet, and is coeditor with Shannon Gibney of What God Is Honored Here? Writings on Miscarriage and Infant Loss by and for Native Women and Women of Color (Minnesota, 2019). Her dream is to create books that a child can grow up with and an adult can grow old with. She lives in Minnesota where the winters are cold and dry and the summers are hot and humid, but there are days in between that are so very precious and perfect they are a state secret.

Kao Kalia Yang is a mother of three and a writer of both adult and children’s literature. She is author of A Map into the World, the award-winning memoirs The Latehomecomer: A Hmong Family Memoir and The Song Poet, and is coeditor with Shannon Gibney of What God Is Honored Here? Writings on Miscarriage and Infant Loss by and for Native Women and Women of Color (Minnesota, 2019). Her dream is to create books that a child can grow up with and an adult can grow old with. She lives in Minnesota where the winters are cold and dry and the summers are hot and humid, but there are days in between that are so very precious and perfect they are a state secret.

This event is free and open to the public.

July 27, 2020

Saying Goodbye to Grandma in Chains

Eddie comes up to me after the midterm and says he too is afraid that he hadn’t done as well as he should have. Eddie is a tutor, a sweet and serious man in his late twenties, who works with other inmates to help them earn a GED.

Eddie comes up to me after the midterm and says he too is afraid that he hadn’t done as well as he should have. Eddie is a tutor, a sweet and serious man in his late twenties, who works with other inmates to help them earn a GED.

“You see, my grandma died this week,” Eddie says. “And I was too sad to study.”

“I’m so sorry, Eddie. Of course I understand.”

“I did get to see her, though. They let me go see her.”

“Wow, Eddie, I said, incredulous at the seemingly humanitarian gesture. “So you got to say goodbye to her?”

“Well, no. I waited till she died. I had a choice but I had to be in the orange jumpsuit all shackled and in chains. I didn’t want her to see me like that; I didn’t want that to be the last picture she had of me as she left this earth. So I waited till she died. They took me to the funeral home. And I kissed her good-bye.”

Saying goodbye to those we love and grieving them with dignity is a basic human right. Yet, for the incarcerated many of the things that keep us humans are denied.

The goals and aims of education and the goals and aims of incarceration are fundamentally opposite. Education seeks to liberate; incarceration necessarily seeks to constrain. Education seeks to humanize; incarceration inevitably seeks to dehumanize. Education seeks to give the individual power; incarceration only works if the incarcerated are rendered powerless. Yet departments of corrections are aware that education is the only reliable key to reduce recidivism. So, how does one accomplish the education needed to retrain, rehabilitate and heal while at the same time, effectively controlling individuals until they are released?

Excerpt from WORD NO BARS CAN HOLD