Tara Mohr's Blog

November 19, 2025

Why Do We Feel Hurt? 7 Reasons, and Then Some

What makes us feel hurt?

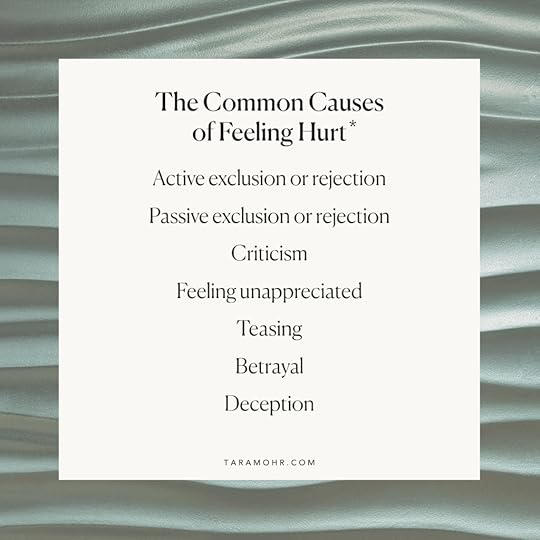

Psychology researchers have sought to come up with a list of the causes of feeling hurt. They created that list for further research and study on the types of hurt, but I immediately grabbed onto that list as itself a kind of personal growth tool. I find it immensely useful in my own life, and in my coaching.

The idea here is not that we always feel hurt when we experience these things. The idea is that when we do feel hurt, usually one of these is the cause.

• Active exclusion or rejection. These are experiences of outright rejection, exclusion or ostracism that cause us to feel hurt. For example, not being invited to a friend’s small birthday gathering, or being broken up with by a partner, or being a final candidate for a job and not being the one to get it. We all know it from our own life experience – rejection or being left out can really hurt.

• Passive exclusion or rejection. These are more subtle experiences of exclusion, or things we may interpret as rejections, for example, “They didn’t even invite me to sit down with them,” or “She stopped answering my texts – she doesn’t want to be friends.”

• Criticism. This includes literal criticism, implied criticism, or things that we interpret as criticism.

• Feeling unappreciated. Often not because of what others do – but what they don’t do or say. “I worked really hard to cook a beautiful dinner for my family and they didn’t even come to the table when the food was hot.” Or “You never say thank you for everything I’m doing for the family, and you’re always focused on what I’m doing wrong.”

• Teasing. We can probably all remember a childhood hurt from some form of teasing. Maybe there’s a kind of teasing happening in your adult life that hurts too.

• Betrayal. Whether personal or workplace, extreme or subtle, betrayals make us feel hurt.

• Deception. When we are lied to or feel deceived – particularly if it happens with someone we trust – whether or not we know them well, deception hurts.

So, how does this become applied, how can we use it for our own wellbeing?

One way is this: Think of a recent hurt. Then notice, what was the reason? Was it a combination of a couple of them?

Then, I invite you to do a practice. Write down a simple sentence along these lines,

“I felt hurt when Kim said she couldn’t help me, because it felt like a betrayal.”

“I felt hurt when John said I should try thinking logically sometime, it was hurtful teasing.”

“I felt hurt at the dinner when no one seemed to want to talk to me – because it felt like a rejection.”

Begin with, “I felt hurt when….” and then describe the situation in a short, summary phrase. Then add to it a “because…” phrase, identifying which of the causes of hurt from the list above feels like the best fit.

This kind of simple sentence helps us do three incredibly important things.

#1. We boil down the situation to a short phrase. When we are hurt, we tend to get really lost in all the details of the story, especially as anger, blame or shame rush in. The situation feels complex and intricate. When we boil the situation down to a short phrase, it helps us get a little less invested in our own particular argument or narrative. It helps us be a little less precious about it or attached to our take on the story. I know when I do this there’s a kind of 10,000ft view that starts to set in, “Oh right, this is just one more human situation like so many I and others experience everyday.”

#2. As you write this sentence, you are giving language to how you feel. “I was hurt. I felt hurt when…” This is huge. A host of research shows that when we can give language to our feelings, that helps us regulate them and lessen their intensity. It’s also the starting place from which we can consciously choose how we want to respond to the feeling.

Unacknowledged or unprocessed hurt is like an invisible driver in your car – one who is definitely influencing where the vehicle is going…all while you think you are in the driver’s seat. Unacknowledged hurt affects our mood. Our sense of safety with other people, and in the world. Our general emotional rigidity or flexibility, and more.

Whether you ever say “I felt hurt” to the other party is another matter for another post. But if you are feeling hurt, it is a powerful practice to name the feelings to yourself.

#3. You are saying why you were hurt. It’s illuminating to see the cause of the hurt. Hurt, like fear, causes a strong physiologic response that’s often dizzying and disorienting. We don’t see things particularly clearly, or think so precisely, when we are feeling hurt. This list gives us a way to do a kind of analysis of the situation, and to understand it better.

One qualifier. I find that this can go one of two ways. Sometimes, people’s inner wounded part grabs hold of this language and uses it to reinvest in their feelings of outrage and blame. It’s a subtle difference in tone. You can say, “I felt hurt because I was lied to” in a way that feels like an accusation, and brings a deepening of the wound. Or, you can say it with a spirit of self-compassion and more of an observer’s stance.

One thing I love about this list of causes is that it reminds me I’m far from alone in the experience of hurt. It connects, “I felt hurt, because I was lied to (or criticized, or rejected or whatever it was),” and “that is one of the universal human experiences that makes us feel hurt.”

In other words, I’m using this list of universal causes of hurt to ground myself in the truth that in being hurt for one of these reasons, I’ve had a core human experience. I’m joining billions of other humans who have felt hurt for the same reason. I’m part of something larger. It’s actually rather awe-inspiring.

So we say, “I felt hurt when this happened” as a gentle, hand on heart gesture, an “Oh honey, that was hard. It hurts to feel excluded!” Or, “oh honey, that was hard. It hurts to feel unappreciated.”

As we’ll see in a next post, we don’t dwell there. We don’t stay in that experience for the long-haul. But we do pause there to name our hurt and one of the universal human reasons for it, to honor that, and witness it with compassion. Paradoxically, that’s what allows us to move on from it.

Love,

Tara

*Vangelisti, A. L. (2001). Making sense of hurtful interactions in close relationships. In V. Manusov & J. H. Harvey (Eds.), Attribution, communication behavior, and close relationships (pp. 38–58). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Feeney, J. A. (2004). Hurt feelings in couple relationships: Towards integrative models of the negative effects of hurtful events. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21, 487–508.

Leary, M. R., Springer, C., Negel, L., Ansell, E., & Evans, K. (1998). The causes, phenomenology, and consequences of hurt feelings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1225–1237.

November 12, 2025

The Neglected Emotion

“Oh yeah, they call you chickenlegs. Because your body looks like a chicken—you know, super skinny legs and a big stomach on top.”

I was fourteen years old when a boy at school said this to me, while we were standing on the quad between classes.

I was already immersed in diet culture, trying to change my body, knowing it did not fit the mold of how girls at my school were supposed to look (skinny).

I was also a dancer, finding sanctuary and art and joy in my teacher’s dance studio most afternoons. My legs were strong and muscular. They were the one part of my body I felt comfortable with, even proud of.

In that dizzying moment, I suddenly felt wrong to be proud of them. Now, it seemed, my body was a problematic emergency.

It would have been wonderful if my younger self knew that these boys’ inappropriate judgements of others’ bodies were their problem. It would have been wonderful if that younger self had known the Unhooking from Praise and Criticism tools. But she didn’t.

She felt panic and fear and shame, but underneath all of that—harder to sense, harder to name—at the core of what she felt was hurt. Sting, pain, gut punch—hurt. The hurt of, I am not welcome, or okay, or cherished here.

I am sure you have had your own chickenlegs kind of moment.

Hurt doesn’t evaporate on its own. Research has found that quite often, hurt feelings endure, sometimes at a searing intensity, for years or decades. I can still feel my heart rate go up when I write these words thirty plus later.

That was an early hurt. Today, I sometimes feel hurt when I read a cutting comment online about something I wrote, or when a loved one says something that seems like an implied dig or criticism.

More and more, I started noticing that people brought to coaching conversations situations in which the core of the issue was an experience of being hurt. (Here, for our context, I’m speaking not about trauma, but about other important hurts.)

The hurt of feeling betrayed or abandoned by a colleague or collaborator.

The hurt of feeling criticized by a loved one.

The hurt of feeling or being excluded.

The hurt of a professional or personal rejection.

The list goes on.

I was intrigued by how frequently the kernel of what people were grappling with had to do with hurt. But something else struck me as even more interesting: the hurt was stealth.

People often weren’t aware, at first, that they were feeling hurt. They never led with, “Hey Tara, can we talk about x situation? I’m feeling really hurt about it.” Nor did they say, “I’m feeling so hurt by my good friend.”

Instead, they’d say, “I want to talk about this friend who ghosted me,” or “I have this incredibly difficult boss.” In other words, they’d share their narrative about the external situation. If they did speak to their feelings about the situation, they named emotions like anger, shock, frustration, indignation, sadness, grief, guilt, shame, sometimes fear.

But they rarely said I’m hurt.

Yet quite often, their whole physical being seemed to communicate a sense of woundedness. As we coached about the situation more, we would often uncover hurt at the core.

That got me thinking. I’ve been reading widely in the worlds of psychology and personal growth for 30 years now. I’ve read plenty on anger. Plenty on fear and anxiety. The same on shame and grief. But I can’t say the same about hurt.

It turns out, I haven’t just been missing a section of the bookshelf. In 2001, psychology professors Mark Leary and Carrie Springer published an academic chapter entitled, “Hurt feelings: The neglected emotion”. As they put it,

“Psychologists have shown considerable interest in the negative experiences and emotions that undermine the quality of human life. In particular, researchers and clinicians alike have devoted a great deal of attention to emotional reactions such as depression, anxiety, anger, loneliness, and shame, and the size and breadth of the extant literature dealing with dysphoria and dysfunction are staggering. After more than 100 years of work on such topics, one might imagine that behavioral researchers would have, by now, plumbed the depths of human unhappiness and despair. Curiously, however, one common and painful experience has virtually escaped scholarly attention—the emotional experience that people colloquially call hurt feelings.” [1]

Additional research on hurt has been done in the last twenty five years, but there’s still an enormous gap; the number of scholarly articles on anger and sadness dramatically exceeds those on hurt, for example.

One reason for this is that when late 20th century psychology scholars sought to codify the core negative human emotions, their lists did not include hurt. They all name fear, anger and sadness as the primary three; some models also add shame, disgust, contempt or despair. Yet none include hurt in that taxonomy of basic, core negative human emotions.

And you know those cute posters that teach kids (and adults) about feelings? Most of them don’t list hurt as one of the options – even those that find space for emotions like awe, proud, and bored.

This might sound shocking, but for many years there was a debate in the academic community about whether hurt was a distinct emotion, rather than just a component of emotions deemed more worthy of study—like anger, fear, guilt, and sadness. Pathbreaking researchers had to take a bold stand: that hurt was indeed a distinct feeling. [2] That was relatively recently, in the early 2000’s.

Why has hurt been so neglected in research and inner-work conversations? There are a number of potential reasons, but one is this: it’s very hard for us human beings to sit with and face hurt; it’s an incredibly vulnerable emotion. In some sense, the capacity to be hurt is the very essence of our vulnerability. We definitely avoid looking at it and talking about it in our own lives. Is it possible that collectively, we’ve avoided looking at the subject of hurt, not only in our own hearts but in the professional discourse as well?

Think of all the tremendous potential that might come from bringing hurt back into the conversation, as its own focal point. It overwhelms me a little to consider. Think of how we might be able to heal what actually needs to be healed in ourselves. Think of the more tender conversations we might be able to have with each other. Think of how we could get to the underlayer of what’s really going on in a situation, rather than dancing on the surface of anger or blame. Think of how we could have a more heartfelt discourse with each other in the collective realm, to get out of the trance of our reactions to our hurt, and to talk about the hurt itself.

Of course, that is no easy matter. But it’s a possibility worth pursuing, which is why I’m writing and thinking about hurt a lot these days.

The matter is deeply intertwined with our Playing Big. I can’t tell you how many women I see who get stopped in their tracks because of unhealed hurt from unjust or harsh feedback, or from fallings out or painful endings with team members or collaborators. So many of you have given me the honor of hearing your stories about that. But the topic of hurt is also relevant beyond our Playing Big. It’s integral to the health of our relationships and our hearts.

I’ll be sharing more about what we can do with our hurt feelings—and giving us a kind of Hurt 101—an education we all need and generally don’t receive. For today, I hope you’ll chew on this with me: how, and why, has hurt been so overlooked in our personal growth and psychology lexicon? When was the last time you were aware of your own hurt, in such a way that you could (or did) name, “That hurt.” And do a check-in to notice: what is your current toolkit for responding to the everyday kinds of hurts that come your way?

With love,

Tara

[1] Leary, M. R., & Springer, C. A. (2001). Hurt feelings: The neglected emotion. In R. M. Kowalski (Ed.), Behaving badly: Aversive behaviors in interpersonal relationships (pp. 151–175). American Psychological Association.

[2] Lemay, E. P., Jr., Overall, N. C., & Clark, M. S. (2012). Experiences and interpersonal consequences of hurt feelings and anger. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(6), 989–1017.

Top Photo credit: Zyanya Citlalli

November 4, 2025

What I wish more women entrepreneurs knew…

Recently, in the span of a few weeks, I had several strikingly similar conversations with women entrepreneurs in our community.

The conversations generally started with these women sharing some sort of dilemma in their business: How do I decide whether to offer x or y? What if I hate or don’t want to support social media? Is it time to focus on this business full-time? Is it time to stop focusing on this full-time?

With my coaching hat on, I sensed that the questions they were asking didn’t seem to be their real questions. I took note of the tender and subtly hurt tone in their voices. And when we dug a little deeper, it became clear that certain past experiences were sitting within these women as painful memories, even as near secrets that they felt shame about.

Some had courageously put an offer out into the world and…no or little response.

Others had been persisting for a long while without the number of customers or level of success they hoped for.

And because of that…

Some of these women were left thinking their gifts weren’t really wanted or welcome in this world.

Others questioned if they were meant to be entrepreneurs at all.

Many were getting lost in “compare and despair” as they looked at others’ seeming success.

These thoughts and feelings were particularly demoralizing because they’d already worked to overcome such self-doubts in order to even start their businesses in the first place!

And then, with those painful experiences and the self-doubt or bewilderment they caused, many had put business projects and dreams on hold.

Some convinced themselves they needed to get training or expert advice.

Others convinced themselves the problem must be an internal block like fear or self-sabotage they had to then fix through intensive inner work.

Others concluded they had to just wait (and wait, and wait) until the universe brought them something different.

I want to offer a different perspective on these experiences.

I live in Silicon Valley, a place world-renowned as the epicenter for starting and growing successful businesses. Even in this context – in which people take themselves damn seriously as the ultimate experts in starting and growing companies, and in which companies get millions of investment dollars to recruit the best people, do paid marketing, and build the robust technologies – people still expect a very low percentage of businesses to work out.

For example, a venture investor works to select what they feel are the most high-potential start ups, then gives those start ups ample money and guidance and support, yet expects that only about 10-20% of the companies they invest in will become big successes! And they’ve formed these expectations about their odds based on a lot of past data.

Here’s a second important thing: those 10-20% of companies that do succeed don’t get it right on the first time. In fact, tech investors expect startups to spend ~3-18 months in a process of experimentation in order to discover – via trial and error – what resonates with a group of customers. These businesses often find traction with an offering or positioning that is wildly different than the entrepreneur’s original idea.

It pains me that while (mostly male) tech entrepreneurs are embracing this ethos of experimentation and not taking failures personally, so many of the women creative and small biz entrepreneurs I speak with are in a very different situation. We haven’t been told that we are allowed to have lots of trial and error, let alone supposed to have it! We expect ourselves to get it right, right out of the gate, and we often take on so much self-criticism and shame when we don’t.

So please hear me, loud and clear.

Business struggles have nothing to do with worth.

Often, they don’t even have much to do with talent.

Having few customers does not signify that you are less talented, unique, or less liked or loved than someone who has many.

All it means is that you haven’t yet landed upon the combination of elements that make a product work for some particular group of customers.

That’s it. It’s actually a kind of boring, tactical problem. Nothing more and nothing less.

And one more thing: for all of you creating beautiful art, exciting innovations, or new forms of healing and personal growth work, please know that sometimes the most valuable, revolutionary work and ideas aren’t met with huge demand in the marketplace. The mainstream world’s consciousness of its actual needs – its understanding of what is actually most deeply valuable – may not be there, where you are, yet. And if that’s your situation, you don’t just have to wait or despair. There are a whole host of specific implications for how to approach your cutting edge work, as well as for how you sustain yourself financially.

Alright – so big picture, if you’ve been carrying pain or shame around these topics, I truly hope this note helps you to begin to let go of it.

And if you’d like to dive deeper into these ideas,

• to learn what experiments to run in your business, so that those experiments help you discover what will find traction with an audience

• to get off the emotional roller coaster ride, and separate confidence and self-worth from your business metrics once and for all

please join me for Trust & Traction, my entrepreneurship workshop in August.

In an intensive (and joyful!) day together, we are going to let go of myths, learn a ton, and land into a powerful reset in our businesses. Get your spot here!

With love,

Tara

Photo credit: Martin Reisch

October 30, 2025

Out of the Narrow Places

Lately I’ve been simmering a lot on what I’ve come to think of as “the narrow places”.

I don’t mean the hallway that’s a little too slim or an impossible parallel parking spot downtown.

I mean the immaterial narrow places – the felt experience of being in a confined, pressured, constricting internal state.

There are many kinds of narrow places.

Living with mean, judging, self-critical thoughts in your head is a narrow place.

Avoiding what’s true is a narrow place.

Being certain that you have to trade off something that is dear to you to get something else that is dear to you is a narrow place.

Living with the shoulds or have-to thoughts holding authority over you is a narrow place.

Carrying around fiery resentment at someone is a narrow place.

There are many narrow places, but in my view, they exist in a kind of loose constellation with each other. They have a lot in common.

I’ve seen again and again that we can move out of the narrow places and back into what we might call the expanse – the inner space where we feel a sense of possibility, where possibilities abound and ideas and visions and whispers for ways forward come into our minds and hearts.

Working with people, watching them leave the internal narrow places, I’ve come to believe something a bit radical: if we’re in a narrow place, that’s not the full story. The situation at hand is not merely some cynical verdict about how things are, about the harsh reality of life. There is a different way to see it, listen to it, relate to it.

All of this has nothing to do with avoiding the harder realities of life. Sadness is not, in my experience, a narrow place. Grief is not at all a narrow place – it is vast and wide, and often it is the way out of the narrow place. This is not about turning sad to happy. It’s about moving from the internal narrow places to the expansive ones.

Often a change in perspective, narrative or beliefs ushers us quickly out of the narrow place. That’s one of my favorite moments in working with others – when a narrow place that seems so intractably confined suddenly reveals itself to have a big open doorway, or even a bright yellow waterslide that we can jump on and go down with glee. We leave the narrow place behind simply because we saw the situation in a new way… or we saw our role in a new way… or we shifted from a fearful part of us to a calm one or a loving one.

Sometimes we leave the narrow place by giving ourselves permission to do something that we haven’t given ourselves permission around before.

Sometimes we leave the narrow place simply by expressing fully how we feel, unburdening our heart to a loving ear.

Sometimes we leave the narrow place by making a new choice, taking a new action, saying a new no or a new yes.

Today I want to share some beginning steps for moving out of the narrow places.

We can each begin with noticing, “I’m in a narrow place around this.”

It’s a significant reframing. Instead of “she’s just so impossible” it’s “wow, I’m really in a narrow place in how I’m relating to her.” Instead of “my to-do list is unbelievably long and I have to get it all done by three or I will prove myself a slacker once again,” it’s “okay, I’m really in a narrow place with how I’m relating to the work on my plate.” Instead of “this family member won’t listen to me and do what’s right and safe for them and it’s driving me crazy,” it’s “I’m really in a narrow place in how I’m relating to this person I can’t control.”

We can notice when we’ve landed in a narrow place.

Second, we can take being in a narrow place as a call for us to do some inner or outer work to help move ourselves to an expansive, generative state. Being in a narrow place signals to us that there’s a need for a shift.

How might we shift out of the narrow places?

You can always place your hand on your heart and have compassion that you’re in a narrow place. That’s a powerful start.

Then, perhaps a lowering of expectations to something more realistic of what we can really get done today,

perhaps a humbling reminder that we’re all very fallible beings doing our best,

perhaps a remembering that there is no win to seek, except the win-win,

perhaps some time to heal a hurt, or dissolve a resentment, or find a creative solution instead of settling for something that doesn’t feel right,

perhaps a pause to help everyone slow down and feel a little safer and more connected before you all dive back in to tackle the problem in front of you.

Perhaps a new question. What are my points of agency here? Given that I can’t control others, what is a wise and serenity-creating response? What are the gifts or lessons in this? How is this the perfect life curriculum for me at this time? Sometimes, a powerful question is the door or window or skylight in the narrow place.

So, notice when you’ve landed in a narrow place. Let that be the signal there’s a need for a shift. And then use the tools and questions and practices that help you find the expanse again.

Thank you for reading. If this post evokes a story or thought or sentiment you want to share, please email me here. Whether or not I can respond, I will read all of your notes.

Love to you today,

Tara

Photo credit: Valilung

June 16, 2025

10 Things I Believe About Writing

There is no question that these are turbulent and daunting times.

Writing is one of the ways we can ground ourselves, process what we’re feeling and thinking, and make a positive impact on others.

A few years ago, I wrote and shared 10 of My Convictions About Writing. Here they are, with some updates.

1. What defines us as writers is simply that we write – frequently or rarely. We are writers in that we endeavor to put our experiences, questions, sentiments, into words on the page.

2. Creativity exists naturally in all of us – but in most of us, it gets blocked. We often need support unblocking and unlocking our words.

That’s why creative recovery is a thing. I’ve been through my own, and am always reaching for more of that recovery. Creative recovery can happen for us.

3. Writing heals. As we translate our lived experience into words, we metabolize and integrate it. We put what’s past more firmly in the past, and discover what’s arising in the present. We become the authors of our experience, the creators of it in some sense, in its second life on the page.

4. For women, every act of articulation is an act of empowerment, because we are in the midst of many generations of being silenced.

5. To unleash the flow of words, we have to write for ourselves and ourselves alone. Impact on the world or accolades may come, but only if we’ve learned to write for ourselves first.

6. The writing work that lands most strongly in the world is born of authenticity and courage – not from polishing, perfecting, or trying to guess what readers want. That’s one of the many reasons that most of what we learned about writing in school does not give rise to the kind of writing that changes hearts and minds – others’ or our own.

7. The age of AI is demonstrating that an artificial intelligence can generate near infinite amounts of relatively logical words on a page – and, for a very long time, our own mental chattering minds have been doing that too. This is a time to discover and reground in the very different thing that makes words important, moving, and transformational – for both writer and reader.

8. Editing and craft are merely good assistants to the more important qualities of authenticity and courage. And, they are damn good assistants!

9. If writing feels stilted, clunky, frustrating, futile, that’s okay. We just need to dip beneath the surface in you to the place where the words are ever flowing. The flow of words is always tappable, and community, prompts, and structure can help us tap the spring.

10. Most importantly: your story and life experience, your ideas and inquiries are enough to make for plenty to say. That’s so hard to see in ourselves sometimes, but I can promise you, it’s true.

If these ideas about writing, creativity, and sharing our voices resonate with you, please use them, post them, pass them on!

And, if these ideas resonate with you, I hope you will join me for my upcoming online Writing Retreat this summer.

January 20, 2025

In These Times

So here we are, in 2025. So much is unfolding with speed and fury in our collective milieu, from climate disasters, to accelerating technological change, to rising authoritarianism around the globe. It is not for the faint of heart.

Certainly in these times, my team and I are feeling, in a new way, the profound need to support women in their leadership and in creating full and fulfilling lives. That’s the “what” of our work. But these times have prompted my team and I to reflect on what’s important about the how of our work – meaning, the stances we take and the values that guide our work with each other and with you each day.

I want to share how we, on the Playing Big team, are showing up in relationship to these challenges this year. We aim to operate with three principles informing everything that we do. These have all long been a part of how we work, but they feel important in new ways, and we will be making them more central to our work this year.

I think of this principle as “everybody precious.” Everybody holy – everybody a piece of, a part of – the divine. This principle is foundational, it changes everything, and there is a huge assault on it in our time.

I think of this principle as “everybody precious.” Everybody holy – everybody a piece of, a part of – the divine. This principle is foundational, it changes everything, and there is a huge assault on it in our time.

Our team lives the conviction that every person is precious in so many different ways, large and small. It shows up through the deep care we always try to treat our readers and course participants with. It shows up when a member of our team sits down and writes, by hand, the name of each person in a course before it begins, saying a quiet blessing of well wishing over each name. It shows up in my starting assumption before any coaching conversation: that I am about to experience a miraculous human being worthy of absolute cherishment. It shows up, too, when we get a tricky or difficult email from a reader, and we slow down to do the sometimes lengthy reflective and discernment work to figure out how to ethically and generously respond.

In the current context, treating people in these ways is countercultural. If the rest of your day felt like it jerked you around with harsh words and experiences, we want our space to be different. We want it to be a soft place to land.

But it’s not just that we work to hold each person as precious. It’s also that, in our courses, people come to see each other’s sacredness and humanity – often across real differences in identity of many kinds. As just one example, on a recent course call, we had participants present from Croatia, Jamaica, Canada, Poland, South Africa, Slovakia, Sweden, Bermuda, Switzerland, Australia, Colombia, Spain, Netherlands, India, UK, and more. And within the U.S. participants joined from Chicago to Houston, from the Puget Sound to Florida, from Indiana to Wisconsin, and everywhere in between.

Because of the tone we set, and because we aren’t just engaging in small talk, but instead having coaching conversations in which each person’s tender dreams and fears come forth, something amazing happens. Across our wide-ranging community, people experience each others’ essences, their stunningly bright light. They are moved by each other. In the climate of increasing dehumanization, and the misinformation about each other that is so rampant now, this is important in an entirely new way.

The second theme we are embracing this year is helping people ground in ungrounded times.

The second theme we are embracing this year is helping people ground in ungrounded times.

What does it mean to be grounded? It means that we are regulating our nervous systems and processing our emotions so that we can keep returning to a state of openness, centeredness, and goodwill – and then taking action from that state. This is vital, as every day we are seeing leaders take action – not out of those calmer and wiser internal spaces – but out of their own gaping unhealed wounds and harmful animosities. As they do that on the most visible stages, they are normalizing that behavior, and granting a dangerous permission for others to do the same in their own communities and homes.

All of us who are doing work to help people regulate emotionally are doing a crucial collective task: building the cohort of individuals who can act from solid emotional and mental ground. Parents, teachers, therapists, coaches, wellness support people do this work quite formally, all day long. But many of us do it more subtly through our work – by being the calm one in the room, by knowing how to help people talk through triggers or intense emotions, or by being a problem solver who can help people move forward together. I see our team’s work as also fitting in here – both in offering coaching conversations that help us shift and regulate, and in teaching self-coaching tools that give people the skills to again and again move from fear, stress and resentment, back into their calmer and loving selves.

Our third principle is about embodiment. In these times, it’s all too easy to end up living like floating heads lost in our devices. Meanwhile, AI is rapidly blurring the lines between what’s human and what’s not. And we find ourselves in relationship to a disrupted, changing earth. All of these currents threaten to pull us away from our sensory, incarnate existence. But it’s through the body, so much of the time, that we ground and source ourselves. And so often it’s through embodied human connection – voices, faces, touch, felt energies – that we find comfort and calm.

Our third principle is about embodiment. In these times, it’s all too easy to end up living like floating heads lost in our devices. Meanwhile, AI is rapidly blurring the lines between what’s human and what’s not. And we find ourselves in relationship to a disrupted, changing earth. All of these currents threaten to pull us away from our sensory, incarnate existence. But it’s through the body, so much of the time, that we ground and source ourselves. And so often it’s through embodied human connection – voices, faces, touch, felt energies – that we find comfort and calm.

In these times, I need the solace that comes from gazing at eyes and faces. I need to hear human voices aloud. In fact, “Keep It Fleshy” is my personal motto for 2025. It makes me chuckle because it’s such a cheeky phrase, but I’m not joking about the actual meaning of it at all! I am taking darn seriously designing a life that stays rooted in felt connection and embodied day-to-day living: more voices aloud, more gatherings, more touch, more immersion in water, more physical movement, more staring at trees.

In our work as a team, Keep It Fleshy means we will be offering more opportunities for live interaction within my courses, more opportunities for participants to know each other, and for me to get to know each of you. I’ll also be doing more in-person events than I have in a long time, as well as doing smaller events, with the grassroots communities and organizations that inspire me and fill me up. Because what I know for sure is that in these tumultuous times, we need each other – and we need to connect in embodied ways.

So, those are our principles.

Everybody Precious.

Grounding in Ungrounded Times.

Keep It Fleshy!

That’s how we plan to operate within our team and with you this year. We look forward to supporting you, gathering with you, and learning from and with you.

With love,

Tara & team

Photo Credit: Natalia Blauth

October 13, 2024

What I do next with feedback

We all get a lot of feedback.

There are the more obvious forms of feedback – a client’s feedback about a session, a performance review with your boss at work, some honest and tough feedback from a teenager in your life, and so on.

Then there are the more subtle forms of feedback.

Posting something on social media about a political cause that matters to you and getting tons of positive responses? Feedback.

Applying for fifty jobs and not hearing back from any? Feedback.

No sign ups to your course? Feedback.

Getting rehired by the same consulting client over a decade? Feedback.

Being asked by your community organization to run for a leadership role? Feedback too.

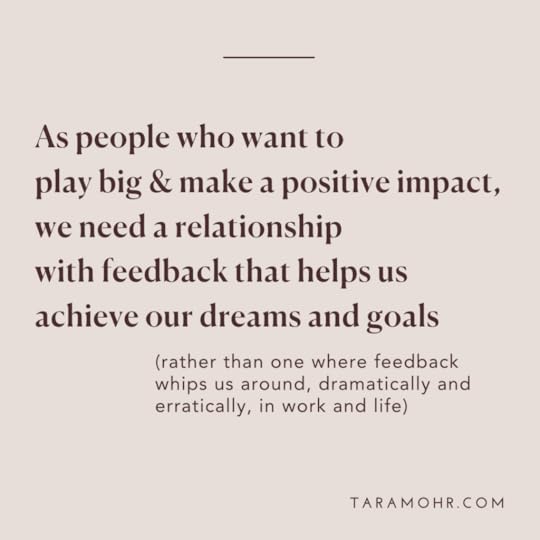

Every day, we find ourselves in feedback situations. That means we need an everyday toolkit for working with feedback. And particularly those of us who have been taught to be people-pleasers or to put others’ opinions before our own internal sense of authority – we need a relationship with feedback that helps us achieve our most important dreams and goals, rather than one where feedback ends up whipping us around – dramatically and erratically – in work and life.

And looking through the bigger picture lens, thinking about women playing bigger, sharing our voices, bringing our work into this broken world to make it a better place…

…if we take feedback as a referendum on us, and go on an ego-up-and-down roller coaster with it, we simply aren’t going to be able to do the needed, revolutionary, beautiful work we are here to do.

But if we take feedback as valuable information – information about the people we are trying to reach, change, support, engage – then we have a shot at refining our work to be truly impactful.

So today I’d like to share with you the Playing Big model for Unhooking from Praise and Criticism – the model for working with feedback – including the new additions to that model since the Playing Big book came out.

It’s been fantastic to see how widely applicable this model is. I’ve seen it have positive impact on… a 7th grade girl thinking through her teacher’s harsh feedback, a professor unpacking being denied tenure, a worn-out job seeker needing to bounce back from rejections, a social justice focused artist wanting to grow audiences for her work. The Playing Big model is even being used in Fortune 500 companies pre-performance reviews, to help people have truly constructive conversations (because we know how those can often go!).

But before I go further, let me also say what the Unhooking from Praise and Criticism model is not a good fit for. It is not a good fit for situations when the feedback you receive involves someone speaking to you about your privilege, biases, or blindspots. That is a crucial kind of feedback, and a genuine learning and reflection process should follow. Opening up to and really hearing that kind of feedback, and changing as a result of it, requires its own specific kind of process (and what I’ll share below is not the right toolkit for it).

So, keeping that in mind, you can use the Playing Big Unhooking from Praise and Criticism process when:

you are receiving the polarized reaction or especially personal or harsh feedback that visible, vocal women often get you are receiving any kind of everyday feedback on a product or service, job role or piece of work such as customer feedback, workplace performance reviews, audience feedback for creatives, hiring decisions for job seekers, and so on.So, let’s walk through the model.

Let’s say you’ve gotten ten rejections from publishers. Or, your boss said you need to have more “executive presence.” Or, a client said sessions with you feel rushed. Here are the four steps to take.

Step 1: Reframe the Feedback

Ask yourself: what does this feedback tell me about the person or people giving the feedback? What does it tell me about their needs, preferences, or priorities?

This reframing is the big mental and emotional pivot point.

Typically, we think feedback is telling us something about ourselves. Then we tend to get defensive (if we think the feedback is wrong, off-base, crazy!), or we get deflated (if we think the negative feedback is maybe true). And if we think positive feedback is deeply about us (rather than about the other party), we often get so pumped up or relieved that we fail to reflect on what the positive feedback is teaching us about what others are looking for or resonate with – what we might give or do more of. In other words, whether it’s negative or positive, we go on an egoic roller coaster with the feedback, instead of understanding strategically useful information.

But instead, we can see feedback as information about the point of view, needs, priorities, perhaps fears or preferences of the person or people giving the feedback.

Your client says the work felt rushed? That doesn’t really tell us any facts about whether you were rushing, but wow does it reveal something interesting and important about your client’s experience.

Ten publishers rejected your book? That really doesn’t give us any facts about you as a writer, but it might start to point us to some information about what publishers are looking for. If we asked some follow up questions about the rejections, we likely would learn even more about that.

When we reframe feedback and we start to think about the valuable, revealing information we are getting, the emotional charge dissipates, and we often find we are curious to even learn more.

Step 2: Check for Relevance

Quite often, women especially assume that being a decent human means caring about everyone’s opinion. Patriarchal myth alert!! None of us are going to get important work done while pleasing everybody.

We need to ask, is this feedback relevant to me achieving my goals?

If the feedback is from a boss in a job you want to stay in, the answer is probably yes.

If the feedback is from one of the few women of color in your organization, and you believe in equity and inclusion, yes, it’s highly relevant.

If the feedback is from the gatekeeper to something you need (like funding, access, press, etc.), likely the feedback is relevant.

But… if the feedback is from your PhD advisor from 20 years ago and you are no longer even in academia… it’s probably not relevant.

If it’s comments on your home from the auntie whose cleanliness standards you don’t even want to live up to… then the feedback is probably not relevant.

If the feedback is relevant to you, keep going – time for step 3.

If it’s not relevant to you, congrats, you are done with the process on the feedback! Return to focusing on your core goals, and to feedback from the stakeholders that are relevant to those goals.

Step 3: Revise Your Approach

If you determined this feedback is relevant to you, consider how you might want to revise your approach, in light of the feedback you’ve received.

So, maybe you learned publishers are looking for books with a snappier main idea, and you feel okay about revising your book proposal to align with that.

Maybe you learned your client easily ends up feeling rushed, and that she’d really like to cover fewer topics in each session, and revising in that way feels good and doable to you.

But take note: in this model, you are not revising your approach because there is something wrong with you that you are trying to fix. You are simply revising your approach to be more effective with the particular stakeholders you want to reach. How liberating!

This step is where you may also end up discerning, “I’m really not okay adapting my work or myself in the way that’s desired or expected here.”

Then you can consciously choose not to adapt in light of the feedback – having made a conscious and intentional choice. Maybe you decide instead to explore other situations where you think the feedback would likely be different. Maybe you come up with some creative third way that takes the feedback into account but isn’t a revision to your work or approach that feels misaligned. All valid, thoughtful choices.

Step 4: Tend to the Relationship

Some feedback situations feel very neat and tidy – and they don’t raise relationship issues. But other times, there’s a relational and emotional dimension that needs our attention. In steps 1-3, we reframed the feedback, evaluated its relevance, and (if applicable) revised our approach to the work – all so that we can work more effectively with those who shared the feedback. That’s the strategic piece.

Alongside of it, we may also need to tend to the relationship dimension – the relationship with self, with individuals who shared the feedback, and sometimes with the organization or larger body involved.

Maybe a client’s feedback revealed that long-term, they probably aren’t the right fit for you. Maybe performance review feedback felt manageable to adapt to for now, but also left you with concerns about how authentic you can be with your manager. Maybe there’s a follow up conversation you’d like to have about that.

Step 4 is where we weave in our bigger toolkit of relationship tools and:

Feel any lingering feelings around the feedback – often sadness, joy, relief, anger, hurt. We give ourselves time and space to feel, perhaps journal about them, or talk them through with someone who we know can be a good listener.This is also the step where we reflect: are there any new conversations we want to have, requests we want to make of the other party, or boundaries we want/need to set in the relationship?This is how we steward our own wellbeing in a world where feedback comes at us, a lot.

So, to recap on our four “R’s” and their key questions, for feedback situations large and small:

Step 1 – Reframe: If you interpret this feedback as information about the person/people giving the feedback, what might this tell you about their preferences, priorities, or perspective?

Step 2 – Check Relevance: Is their feedback relevant to me? Is it useful in helping me achieve my goals?

Step 3 – Revise Your Approach: If so, how can I revise my approach to incorporate this feedback?

Step 4 – Tend to Relationship: Are there any relationship pieces around this feedback that I need to tend to, such as boundaries, processing my own feelings, or making requests?

Try it out, and let me know how it goes! Grab the printable journaling 1-pager here to take yourself or those you support through the 4 R’s.

And share this with a friend or colleague who would benefit!

We do much more unpacking of Unhooking from Praise and Criticism, and giving and receiving feedback, with case studies, coaching demos + lots of Q&A in the Playing Big courses. The courses will be starting up soon. Stay tuned for details and to join!

September 27, 2024

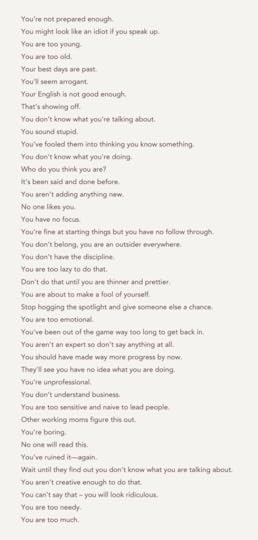

What We Say to Ourselves

These are the real words of women, sharing what their inner critics say, sharing the kinds of self-diminishing thoughts they live with, day in and day out. (And we all know their lives are hard and demanding enough without an added dose of self-criticism.)

When I teach a Quieting the Inner Critic workshop, I begin by asking the participants to share one thing their inner critic says to them. Answers like this stream in. A flood of self-criticism. A flood of the legacy of the sexism that lives inside us. A flood of the legacy of a civilization not yet loving enough to build people who cherish themselves and each other.

Then I ask the women present what they feel reading all those inner critic thoughts from others. Undoubtedly people say:

“It makes me so sad.

”

“

My heart hurts.”

“I’m crying reading these.”

“I can’t believe we do this to ourselves.”

“It’s terrible, but it makes me feel less alone.

”

“

Horrible but healing.”

Fifteen years ago, when I started my coaching practice, the inner critic voice was loud for every woman client I had – and they were all remarkable, capable women. At that time in my life, the inner critic was loud, invasive, and dominant in my own head, too.

I got very, very interested in how we quiet that voice – quiet it enough that it doesn’t direct our decisions, keep us silent, or hold us back from going for our dreams.

Things that I’ve found don’t work (for most people, or for very long) in quieting their inner critics:

Trying to just say “f-you” to it, and kick it to the curb with a kind of pumped up, faux-empowermentArguing with its criticisms through positive thoughts or affirmations about ourselvesReminding ourselves of our accomplishments or others’ praise and trying to find confidence from thoseThe things that do consistently work and make a real difference over the long term are subtler and softer. They include:

Getting a kind of Inner Critic 101 training so we can recognize it for what it is and understand how it functionsUnderstanding the inner critic’s protective (but misguided) motivation around safety – and seeing its intent with compassion and clarityDrawing on parts of us that are stronger and deeper than self-doubt, like values and the inner mentor’s voiceAltogether, the work involves a shift in orientation. It’s not about getting rid of self-doubt and becoming unfailingly, blazingly confident. It’s about having the skills to wisely respond when self-doubt arises, as it inevitably will, as we face life’s uncertainties and stressors, and as we stretch into new kinds of playing bigger.

So, today, ask yourself these key questions:

What is my inner critic speaking up about these days? In my life? In my career? About my body? (There’s always more fresh awareness to gain here, since our inner critics often sneakily creep in.)What would happen if I didn’t hold those inner critic thoughts as truth, but rather as an expression of my safety instinct that’s trying desperately to scare me enough (about failure, rejection or humiliation) that I’ll shrink back into my comfort zone?Then check out the tools in The Inner Critic chapter of Playing Big for everyday, moment-to-moment practices for quieting that self-doubting voice, so it doesn’t control your actions.

Thank you for reading and, here’s to quieting our inner critics – together.

Warmly,

Tara

. . . . . . . .

Want more support around working with your own inner critic, or working with clients, team members, or mentees around theirs? Join me for an upcoming Playing Big program.

September 12, 2024

Pulling the Thread

It was a particular joy to get to be a guest on one of my favorite podcasts, Pulling the Thread with Elise Loehnen. Honestly it felt like a bit of a dream to be a part of it! Ask my husband and kids – I was nervous!

If you enjoy my work, I think you’ll love Elise’s work too. In a sea of personal growth content that’s reductive, it embraces nuance. In a landscape with too many tip– and check– lists, Elise is comfortable in the terrain of asking and exploring big questions. And, in a personal growth landscape that has evolved to have its own problematic old boys’ network, Elise is calling that out, and creating stronger women’s networks within the field.

One more thing I especially love. When I look over at my bookshelves of favorite personal growth and spirituality books, it strikes me how many of those books were published before 2010 or so. There’s a kind of book we don’t see a lot in the personal growth space anymore – it’s hard to describe, but I’d say they are books with less of a big, grabby lead idea, and more of a quieter, wise exploration of major questions. Elise highlights these foremothers and forefathers of a lot of the work happening today – people like Harriet Lerner, Riane Eisler, Llwellyn VonLee, and others. We coaches, therapists, spiritual seekers, personal growth lovers – we did not, um, fall out of a coconut tree! It can only enrich our thinking to know our lineages.

Okay, with all that said… you can listen to my episode on the show here.

Here are a few more episodes with teachers who have been important to me:

Harriet LernerJoy HarjoPeggy OrensteinLoretta RossElise’s fantastic Substack is here, and you can get her book, On Our Best Behavior: The Seven Deadly Sins and the Price Women Pay to Be Good here.

Photo by Sean Sinclair on Unsplash

July 10, 2024

The Other Immortality

A few months ago, I was listening to a podcast, a conversation between a physician author and another writer who’d just published a book about creating a meaningful, purposeful life.

This physician author is a big name these days – he’s by all traditional, professional measures wildly successful, with a whole host of accomplishments and even some fame. Yet, as he shared in this conversation, he was struggling with a deep and painful sense of meaninglessness and futility. As he put it, no matter what he did in his life, no matter how much success he had, ultimately, the planets would go on spinning just the same. His own name would be forgotten in the sands of time. This – the not being permanent or even remembered, and not being able to change reality in some major, fundamental way – troubled him.

He is not alone of course. There is a particular notion of meaning that many of us have been seduced by. In this version of significance, you live on because your name is carved into the big buildings you funded, or your story is written in history books because of the power you wielded and the enormous public influence you had. Or, perhaps you win big prizes or create a technological advance that breaks into a new frontier.

Indeed, in Silicon Valley, people actually talk about wanting to make “a dent in the universe” – as if denting this unbelievably beautiful and more-intelligent-than-us miracle would somehow be a good thing. As if it needs our denting.

As I listened to this physician share about his struggle with his individual temporariness, and his ultimate individual insignificance, I couldn’t help but reflect on what I’ve lately come to think of as “the other immortality.”

We – as named selves, with edges we define by our bodies – are indeed finite and mortal. But if we don’t identify with that smaller self, and instead identify with the slightly larger selves – seeing ourselves as nurturers and givers who shape others, who in turn shape others – then the stretch of our lives looks different. We can see the truth that we, via our love, our care, our gifts, are in fact enduring. We just don’t endure in ways that are always knowable to us, easy to chart or pin down.

When I sit on the rug and read Goodnight Moon to my daughter, some things are being poured into her from me: new words she’ll go and use in who knows what ways in her own life, future memories of the comfort and happiness of snuggling with a loved one, perhaps a love for stories. When we sit there and read, we are not just passing ten minutes. We are layering in one more experience that is shaping her.

I can’t know what she will choose to do with her words in her future – comfort people, teach something, offer kindnesses to her neighbors, write some words on a page – who knows? Nor do I know what she will choose to give or create from what will hopefully become in her a deeply felt love for human beings. But I do know she will do something, because that’s how the chain of giving and receiving and giving again works for us humans. And it’s an endless chain: she will impact someone, and whoever she impacts will in turn impact others.

And so, when I read Goodnight Moon, I’m immortal.

And everyone who has shaped my capacity to read to her, to be patient with her, to extend love to her – is in that moment immortal too.

When my childhood dance teacher would gather all of us kids in a circle before class and look at us as if we were the most miraculous creatures ever created, and ask us, with rapt attention, “What did you learn at school today?,” she forever altered how we felt about ourselves. Now we are artists and therapists and activists and aunties and neighbors and teachers. Everything we do is a little bit imbued with her and her love. And so she is immortal.

Or, let me put it this way. If you have ever seen me be patient, you have met my dad. If you have ever heard me ask a searing question, you know something of my mom. If I have ever been kind and affable in a casual sidewalk conversation with you, you know my childhood neighbor Dolores, who was that way with me every single day when I passed by her front walk.

And how many of us are carrying a little of Georgia O’Keefe, or James Baldwin, or some other sage or saint of old, because of how their words and wisdom live in our heart and keep shaping us?

Life is about this miraculous and mysterious mixing of light between humans over time, over generations.

And so, to anyone who is stuck in the cold loneliness of seeking significance in their small-self’s permanence, I want to say: small-self permanence is not actually available to us humans. Permanence of name and individual impact is not here for our taking.

But we do have immortality through love. We pour the golden light of our attention and care and gifts into others. It changes who they are. It shapes the golden light they have to give, and as they give it, some part of our own light is carried forward.

We live on, eventually anonymously.

We live on, always gloriously.

We live on in beautiful ways that, if you ask me, are more than enough.

Love,

Tara

P.S. These ideas are one piece of what we explore in my new body of work about love and relationships (all our relationships). Want to join me for some upcoming workshops about Loving Well? Join the interest list here.

Photo Credit: tenten