Xavier Leret's Blog: Writer. Believes too many of his own dreams.

November 14, 2015

The Face Of Islam That I Know

This is not the Islam that I know. The Islam that I know comes with names like Jade, or Rehana, or Abdul or Tariq. It comes in the form of a young man that I tutor, for an hour every week. A young man who in reality is still a small and incredibly vulnerable boy, who is struggling with his GCSEs, who is frustrated because his friends are already shaving and he’s still got the face of a baby, struggling because he is not as big as the other boys in his school, who like so many other young people is struggling to understand himself and his place in the world. He likes football and every week he tells me that he scored a goal, that his team won or lost, that his team is a team. And his mum is a power-house of independence who bucked her cultural background and left her husband, who strode out alone. For her, for her son, there is only one direction in their faith and that is for peace.

The Islam I know comes in the faces of some of the members of the most fantastic ensemble of young people that I was lucky enough to work with over the summer. We explored life and age and death. We created the most sensitive and eloquent contemplation of these subjects in words and photographs. Not my words, theirs, their observations, their understanding. They look through the camera to see. In that group there was no racism, no hatred, no dogma. I watched these young people develop our project in an old people’s home and I was moved to tears by their care and humanity, by their gentleness, by their capacity to love. That is the face of Islam that I know. As an atheist who has no truck with God or faith or religion, I find those faces to be beautiful. They did not show me horror, they gave me hope.

April 27, 2015

When I Grew Up God Was Everywhere

I went to a Catholic primary school so God was pretty much everywhere. He was there too in secondary school because the headmaster was a lay-preacher. Priests never visited my secondary school like they had my primary school but a band called ’Amessiah’ did play. I had no idea what they were singing about but I thought the quitar playing was great. I loved how loud it was too. I didn’t have pop music at home, in fact we didn’t have a record player. Watching Top Of The Pops was frowned upon. I did have a radio in my room and I was given this old record payer in a suitcase thing that someone was throwing out. I began to discover music.

When I was fourteen or so I went to this Evangelical church which was like a hypnotists show. One of the preachers told this story about how once, when they were flying somewhere, they needed cheering up, because their life was not going as it should, when all of a sudden an air stewardess appeared and offered them a seat in business class. It was an obvious gift from above and a sign that he was real. It was a great sales pitch, you could really see it hooking these kids. Then some people started falling on the floor and wailing. It was quite creepy.

My RE teacher was a rugged looking old Teddy Boy who was rumoured to be a raging alcholic. He brought this man in to chat to us about God. He took out this old watch on a chain and said that it had been made by a master craftsman. Then he said that the universe was like the watch, the economies of scale made this plainly rediculous. By this point in my life I had really had enough of religion, which did not make any sense when compared to all that I was discovering about just about everything. But, it was not until I was at university that I said that I was an atheist out loud. There was a small wood out the back of my halls and I said it out there. I was not smited down. Which I was very relieved about.

April 8, 2015

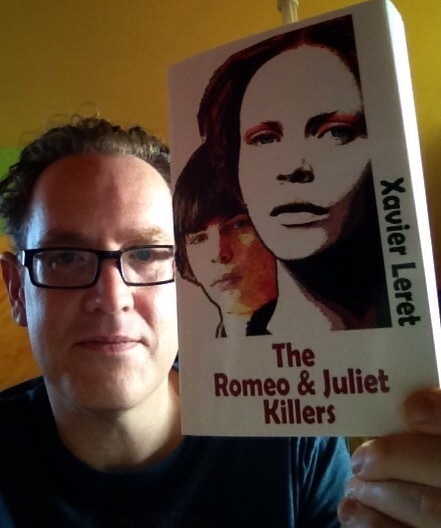

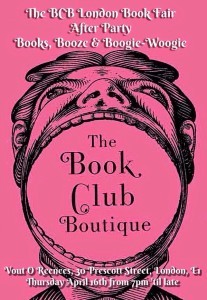

My book launch is next week. I’m reading at the BookClub Boutique!

This April we’re thrilled to be curating live readings from two fresh and exciting, eagerly anticipated new novels, both published this London Book fair week: Paul McVeigh’s ‘The Good Son’ and Xavier Leret’s ‘The Romeo and Juliet Killers’

We’ll also hear new poetry from prize winning poets Lewis Buxton and the reigning champion Young Poet Laureate of London Aisling Fahey. Plus new work from notorious Book Club Boutique hosts Salena Godden and Michelle Madsen.

There will be a live music from Delirium Tremens, treating us to delicious songs from their latest folk noir release. Plus we’ll be drinking and dancing through the night to top tunes from The Book Club Boutique DJ Kevin Richards, and all for just £5 on the door, 7pm ’til late. Click here to join our facebook page for more updates or find us on twitter @bookcboutique

March 23, 2015

March 15, 2015

I Am Change

I am change,

the breaker free of chains.

I am my own benchmark,

my mountain ridge from which to fling my mortal self

and let the wind rush

its drummers thrash

I am free on wings,

and rise above the sleeping drones of working days

and life all missed

all moments lost,

for you,

or him,

or her,

or they,

for pension time,

then silent death,

all too too quick,

and no mark left.

That’s not for me.

This time I have is mine

And I do claim it.

And from this entrepreneurial spark I fire my destiny

not yours, or his, or her, or they,

it’s mine this time I make,

this business that I toil to grow,

my dream,

my vision,

my life long flame.

13 August 2014

March 8, 2015

The Problem Is Not Daizee

Whenever I was in trouble at school, which was a lot, my mum reminded me how lucky I was with the story of this girl she had taught in a residential unit, who’s step-dad sold her to sailors from out the back of his van, which he parked up down the docks in Bristol, when she was three years old. My mum said she was a handful, as were the other girls that she was working with, and that nearly all of those teenage girls were prostitutes. That girl became the template for my character Daizee.

Whenever I was in trouble at school, which was a lot, my mum reminded me how lucky I was with the story of this girl she had taught in a residential unit, who’s step-dad sold her to sailors from out the back of his van, which he parked up down the docks in Bristol, when she was three years old. My mum said she was a handful, as were the other girls that she was working with, and that nearly all of those teenage girls were prostitutes. That girl became the template for my character Daizee.

Nothing was done for the real life Daizee even though enough people knew about what was going on. There were no trials, no convictions. There wasn’t even a scandal. I don’t think it was because nobody cared, my mum did for one, but her job was to teach English, not to keep men off her. That was someone else’s job. My mum did say that the girl and her friends did keep getting themselves in trouble, and that no matter what doors were locked they always managed to sneak out. But like I said my mum wasn’t there when all the nastiness was happening. I guess there was no point in going to the cops because these kids already had reams of paperwork on them and as we now know the cops don’t have the best of records when it comes to ‘wayward’ girls.

In Rotherham the coppers said of the girls that were sytematically raped that it was their fault, they chose to be prostitutes, it was their ‘lifestyle choice’. And I thought of the real life Daizee being fiddled with in the back of a van at three years old. Different coppers echoed those in Rotherham in Bristol and then again in Oxford. I am sure it will be echoed again and again as more cases come to light. Then came an echo from that Delhi rapist/murderer, though a Chinese whisper had morphed it into, “A girl is far more responsible for rape than a boy.” And we hear it all over the Middle East too where they take the protection of their women so seriously they cover them up. And again in Mexico where rape is endemic, Ethopia, Shri Lanka, Canada, France, Germany, India, Sweden, South Africa, The US then back again to here, the UK, to footballers’ hotel rooms and everywhere else that it might go down. Because men like to blame women or, in the case of Daizee and girls like her, teenagers, kids, for their own downfall.

My Daizee, like the real life one, is not fallen, she is no Eve who tempts Adam, because Adam has already raped her long before she got anywhere near an apple. All looked on by a male God, who in a later story sent his angel to do his business and then after that his priests. And in that religion like most of them there is an onus on female modestly because men can’t stop themselves.

Daizee, like lots of Daizees, has had to live with what life has thrown at her. And she does, with bells on. And that makes her a beautiful handful that needs to be celebrated and loved, even though she would probably tell you to fuck right off. But fuck off, or switch off, you must not do. Especially us men. Especially us men. Because the problem is not Daizee.

The Romeo And Juliet Killers by Xavier Leret to be published by Dedalus Books, April 2015.

January 27, 2014

Turn The Porn On

He was lying in the hospital bed with a plastic clip on his little finger from which a wire connected him to a heart monitor. His leathered skin was pulled tight over his cheekbones and jaw. Under his eyes were turbid shadows textured like bruised deflated bollocks. Every now and then his tongue would appear out of his mouth, twitching like a tired old cock in a gentle spasm on those dry and frigid lips. Near dead, he was haunted by the memory of what was once pronounced between his legs, solid and jerking like some plastered drunkard at a dance. Above him on the television screen a national talent show blazed, sculpted kids in tight clothes, gyrating to songs of unrequited love. He didn’t want it switched off, just the channel changed, but he hadn’t the strength to reach up to do it himself. Not that they had what he wanted to watch. Not like in a hotel room.

This was not how he had wanted it to be. This hour of his death. Alone. The veins from his wrists morphed into plastic capillaries feeding from a translucent sac, slung on a pole like a discarded breast implant. His throat rattling. His lungs heaving, in and out like a exhausted gigolo’s ass. And he wanted to fuck, to relive a fuck, to be back in a fuck, to be alive in a fuck, for his prick to break free of these deathbed blankets like the arm of the undead thrusting through the cemetery turf.

The door opened and in walked a nurse, in a white uniform, her shoes squeaking across the floor. Stopping at the foot of his bed to pick up his chart, scan it, and then glance an eye, a poker eye, not giving her game away. Perhaps she was giving him the eye and he just couldn’t read her. That’s how he remembered it when he was young, when he was in the thick of it. Never could read the look in their eyes. Like another species they were, these women.

She hung his notes on the end of his bed, turned to leave. Was just about to vanish from the room when he croaked her back with a half whispered, Nuuurrsrse. Not once but twice: Nuuuurrsse.

When she turned to face him he could feel his eyes sticking out of his sockets. Watching her highlighted hair glisten under the fluorescent strip of lights. It hung to her shoulders. And her body was heavy, but in a good way, he thought, flesh to get hold of, a body that had been lived in. He’d always liked that. A body with experience.

The nurse smiled gently and waited as he searched not for words – he knew what he wanted to say; he was searching for the energy to say it, and when it came it didn’t flow fluent and fast, it was stilted and slow, the deathly cantor of his breath distorting the pitch and tone of his dense Bristolian lilt. Turn the porn on, he said. Turn the porn on, for Christ’s sake. I’m dying . . . I’m dying. I can’t move my arms. This wheezy breath is dragging me down. I can’t do for myself . . . I can’t fucking move. Please, please make an old man happy. I won’t wank. Honest. Christ, look at me: I can’t move. I just want to remember what it was like. I want to remember that feeling of rubbing close to a body. Sliding over that silk. I want to remember her breathing and steaming my eyes up. I want to remember.

Stop this “you can’t help me” bullshit. Stop it. There ain’t nothing wrong with longing. I want to let go of this world fucking. When I can’t breathe no more I want to be breathless, go out on a bang. But you don’t hear me. Just switch me out with soft channels and talent shows. Don’t press the Discovery pages – I don’t want to think myself to oblivion. What is the point of all that knowledge? I want to feel. I want to feel wet pussy. I want to feel pointed tits. I want to feel her little death in my arms, her heart miss a beat. I want to remember coming apart and sticking back together in an instant. I want to remember pumping until it hurts. I want hair in my teeth and the back of my throat.

Please, just five minutes. Make an old man happy. The banter – that old banter running around until the lips meet, that first accident, that first smile with teeth touching, that first smile with eyes melting together, and then a wander around the edge of her tongue.

Don’t let me die now, not just yet. Five minutes more – no, ten – make it a whole hour, just one more hour, just time enough to remember what flesh is like. Just a bit more time to hold on, a bit more time to hold her, to roll her, to fold her flesh, to bite it, lick it, suck it, just a bit more time before I let it go.

I can feel my spirits lift – oh yes, there is life in this old man yet. Oh yes, I can feel my heart picking up, I can feel my breath getting deeper, my chest rise. I love life, I love every day, I love walking, I love talking, I love eating, I love reading, I love looking at people, I love jostling with crowds, I love hard rain, I love being angry, I love shouting, I love screaming, I love running, I love throwing money away, I love getting on the wrong bus, I love it when it’s freezing cold, I love being a child, I love growing up, I love knowing more than I did then, I love knowing that you don’t know what I am thinking, I love the moments when you do, I love staying out late, I love wine, I love drinking, I love wishing that I didn’t, I love working, I love hating bits of my life, I love hating bad food and terrible films. I love not wanting to let it all go.

And now I’m in and we’re down to it. Wow she’s wet – I had a great time drinking her. And now we’re pros we’ve been here so many times, and it’s never without colour, even though the red rouge of her cheeks is slowly growing dull and the pitch black of her hair has long since passed grey to white. This is one land that I don’t mind walking again and again and again.

Please, nurse, just turn the porn on. I want to enjoy these last few breaths, because I can’t let my body go. It doesn’t work like that. Each one of your tubes, in my body, is holding me to this earth like a ship to the shore, keeping me here with nothing to do, except remember. So turn the porn on. Please, turn the porn on. I want to remember. I want to remember it all. Before it stops . . . Before it stops . . .

January 20, 2014

It All Crashed Around George As He Danced A Frantic Financial Fandango

At the trading desks it was a tempest of panicked activity, a maelstrom of despairing voices crying havoc, tossing imaginary life preservers to the howling shrieks of landlines and mobiles, beeping coloured graphs like faulty heart monitors, lines of credit just too short to save creditors, the banking horizon a swirl of economic brimstone and financial fire, phones bleating maydays, reams of paper exploding over head, suited men and their tottering secretaries battening down the hatches, tossing some clients to certain death and others to rack and ruin.

And George had the urge to dance. His only dilemma, amid the greatest financial meltdown in world history, was that there was no correlation between the physical dynamic of his imagination and the reality that his body presented him. Years of neglect, finger tapping keyboards, observing banks of monitors, lounging around board rooms, making plays for the zillions, that one lunchtime drink too many, large breakfast followed by ample lunch boosted by a home cooked supper (often sandwiched between two plates in the oven) finished off with a swift night time snack and the ubiquitous bottle of red, invariably Spanish. All this had distributed about his body more than a few extra pounds. His organism was limber dissipated, his joints stiff, his youth sapped. And yet he could close his eyes and recall playing as a child, spinning, jumping, running, flying, twisting, pirouetting, somersaulting, sometimes like teasing sparrows head over tail through the air, at other times his body shoaled within an ensemble of tumbling weightless minnows.

“If it is a memory within the mind then perhaps,” he told himself, “it is a physical memory too, the ability still stitched into my sinews”.

Sure he might have been a bit clunky and sloppy in his movement, it had been years after-all. His focus has been on his job, revelling in a synthetic joy, built on the foundations of nothing. “Debt begets cash,” he had once explained, “rather like all that begetting in the Book of Exodus. Once there was just a man, now there are gazillions of them. And so it is with debt and it’s spawning revenues.” But the work had dulled his senses, dilapidated his motoneuron capabilities, robbed him of his natural desire to move, to make his body articulate instead of this indolent, supine and lymphatic morphon that remained. This was the crisis that had hit him that morning in the car. Before that as he woke it was the realisation that the hope and dreams of his youth had taken a powder and wandered off into the wings with whatever aspirations for goodness or the good man he may have once harboured. But when he stood beside his car naked and tried to fly, and when that failed, to simply hover, he was left with the grim discovery that he had no capacity for dance left. Yet there was still hope. There was a way that he could get it back. He just needed the courage to make the first move, to step out of the dressing room onto the dance floor and set about his boogie.

“George,” screamed a voice, (George had no idea whose), “answer your fucking phone, it’s going down all sides of the Atlantic. George wake the fuck up.”

It would be wrong to credit George with the economic meltdown of civilisation as it was known then, but his lack of obvious hysteria, his general disregard of the sheer scale of the collapse surrounding him, grown men crying, women wailing, not just in his immediate proximity but one or two floors up and numerous floors down, a cataclysmic wail replicated in offices the world over, yet one observer described him as “sitting at his desk rather like the captain of the Titanic, the ship going down with all hands on deck and all he did was stare with a look of flushed ecstasy across his face, as if he was listening to some cacophonous symphony underscoring the grand opera of historic events whilst ripping the pecuniary carpets from under our very feet.”

There was nothing to be done and certainly nothing that George could do to stem it. Though he could have acted up more, giving some hearty bestial clamours of impending penury of his own, just to fit in, just to be one with the throng.

Instead, after a long stillness, with eyes closed, he stood, raised both his hands above his head, balanced on one leg. And then began to dance. Up and down the aisles of the open plan office, hopping into the air, kicking, sliding along desks, zinging on office chairs, standing his ground suddenly whilst whipping his arms in a flurry of waves, prancing up and down like a chicken, rotating his head at a ferocious speed, tipping on tiptoes, whooping with chest expressed, buttocks compressed, skipping across desktops, dropping onto his haunches like a Russian, whirling like a Dervish. It was a frenzy of improvised colour. It was his renaissance of being. He understood somehow all that was really going on, everything that everybody missed, and I don’t mean it terms of the financial disaster, I mean in terms of life’s mysteries, all that is existentially and metaphysically vital.

The reality of George’s epiphany was a mixture of internal gyrations from which a kablooey of colours, splattered and sprayed slogans of movement that extolled the virtues of being. A medley of imagery such as holding his first born for the first time, which linked to his own recollections of birth, frantic and somewhat fuzzy, falling as a child, being mollycoddled, fighting in the playground, dashing the hundred metres, his first kiss, his first drink, his first day at the office, the crush of bodies on the train into work, the sweat, the battle of perfumes, the conductor squeezing his way through, the poor chap that lost his ticket or had forgotten to purchase it – he has no idea which, the taste of bitter coffee, the repetitive submariner blips of a train station full of iPhones, Blackberries, Qwerty thumbs a clicking, the rushing whirr of the train timetable, weaving the commute, hands up for a cab, dashing the traffic, crushed in on the lift, eyes shifting, the exit as one body, the sudden dispersal of individuals. Each movement he would later admit was clunky, at times extremely sloppy. He lacked the control he needed, he carried that extra weight, he couldn’t manipulate the wobble around his belly. He lacked too the precision of timing necessary to achieve absolute aesthetic transmorphication, which only got worse as his dance went on, his energy slopping out of him rather than shooting like light to the edges of his open plan office.

Tears, wails, looks of disbelief, shock, awe, the world was in plight and George was dancing. Years later he would recall the moment he took flight as his first ever act of pure altruism. There was no undoing the meltdown it had been building for years. Secretly – not even secretly, quite openly in fact, they had all said that this moment would arrive, that there was no way the market could sustain the discords of debt hideously caterwauling out.

Towards the end of his dance George’s body was possessed by a sorrow, an understanding that this day was a cataclysm that the world of men had put in place for themselves an unavoidable nasty deplorable mess all of our own doing. George embodied this sentiment in his hands and feet, in his belly. His lungs could no longer breathe, he was spent, and yet he still danced, his eyes half closed, looking like a reveller, a devotee of Dionysus, an impassioned votariant of mis-rule, jigging his jiggy, a Nero with a conscience- he yelled “for it all to be re-born it must all be pulled down”. Weaving through bodies. Sweat soaking through his white shirt, his trousers sticking to his legs. And then finally exhaustion. George could move no more. He had no idea how long he had been dancing. He was depleted of energy and his movement reduced to the tumultuous pulse of his heartbeat and the pant of his breath as he collapsed at his desk, a computer monitor in front of him, an open plan office in shock surrounding him. The financial markets discarded about him, all collapsed and depreciated, his despicable dance done.

As It All Crashed Around Him George Danced A Mean Fandango

At the trading desks it was a tempest of panicked activity, a maelstrom of despairing voices crying havoc, tossing imaginary life preservers to the howling shrieks of landlines and mobiles, beeping coloured graphs like faulty heart monitors, lines of credit just too short to save creditors, the banking horizon a swirl of economic brimstone and financial fire, phones bleating maydays, reams of paper exploding over head, suited men and their tottering secretaries battening down the hatches, tossing some clients to certain death and others to rack and ruin.

Yet for George amid the greatest financial meltdown in world history there was no correlation between the physical dynamic of his imagination and the reality that his body presented him. Years of neglect, finger tapping keyboards, observing banks of monitors, lounging around board rooms, making plays for the zillions, that one lunchtime drink too many, large breakfast followed by ample lunch boosted by a home cooked supper (often sandwiched between two plates in the oven) finished off with a swift night time snack and the ubiquitous bottle of red, invariably Spanish. All this had distributed about his body more than a few extra pounds. His organism was limber dissipated, his joints stiff, his youth sapped. And yet he could close his eyes and recall playing as a child, spinning, jumping, running, flying, twisting, pirouetting, somersaulting, sometimes like teasing sparrows head over tail through the air, at other times his body shoaled within an ensemble of tumbling weightless minnows. “If it is a memory within the mind then perhaps,” he told himself, “it is a physical memory too, the ability still stitched into his sinews”. Sure he might have been a bit clunky and sloppy in his movement, it had been years after-all. His focus has been on his job, revelling in a synthetic joy, built on the foundations of nothing. “Debt begets cash,” he had once explained, “rather like all that begetting in the Book of Exodus. Once there was just a man, now there are gazillions of them. And so it is with debt and it’s spawning revenues.” But the work had dulled his senses, dilapidated his motoneuron capabilities, robbed him of his natural desire to move, to make his body articulate instead of this indolent, supine and lymphatic morphon that remained. This was the crisis that had hit him that morning in the car. Before that as he woke it was the realisation that the hope and dreams of his youth had taken a powder and wandered off into the wings with whatever aspirations for goodness or the good man he may have once harboured. But when he stood beside his car naked and tried to fly, and when that failed, to simply hover, he was left with the grim discovery that he had no capacity for dance left. Yet there was still hope. There was a way that he could get it back. He just needed the courage to make the first move, to step out of the dressing room onto the dance floor and set about his boogie. “George,” screamed a voice, George had no idea who, “answer your fucking phone, it’s going down all sides of the Atlantic. George wake the fuck up.” It would be wrong to credit George with the economic meltdown of civilisation as it was known then, but his lack of obvious hysteria, his general disregard of the sheer scale of the collapse surrounding him, grown men crying, women wailing, not just in his immediate proximity but one or two floors up and numerous floors down, a cataclysmic wail replicated in offices the world over, yet one observer described him as “sitting at his desk rather like the captain of the Titanic, the ship going down with all hands on deck and all he did was stare with a look of flushed ecstasy across his face, as if he was listening to some cacophonous symphony underscoring the grand opera of historic events whilst ripping the pecuniary carpets from under our very feet.” There was nothing to be done and certainly nothing that George could do to stem it. Though he could have acted up more, giving some hearty bestial clamours of impending penury of his own, just to fit in, just to be one with the throng. Instead, after a long stillness, with eyes closed, he stood raised both his hands above his head, balanced on one leg. And then began to dance. Up and down the aisles of the open plan office, hopping into the air, kicking, sliding along desks, zinging on office chairs, standing his ground suddenly whilst whipping his arms in a flurry of waves, prancing up and down like a chicken, rotating his head at a ferocious speed, tipping on tiptoes, whooping with chest expressed, buttocks compressed, skipping across desktops, dropping onto his haunches like a Russian, whirling like a Dervish. It was a frenzy of improvised colour. It was like he had just come alive. It was like he understood somehow all that was really going on, everything that everybody missed, and I don’t mean it terms of the financial disaster, I mean it terms of life’s mysteries, something existential and important. The reality of George’s epiphany was a mixture of internal gyrations from which a kablooey of colours, splattered and sprayed slogans of movement that extolled the virtues of being. A medley of imagery such as holding his first born for the first time, which linked to his own recollections of birth, frantic and somewhat fuzzy, falling as a child, being mollycoddled, fighting in the playground, dashing the hundred metres, his first kiss, his first drink, his face day at the office, the crush of bodies on the train into work, the sweat, the battle of perfumes, the conductor squeezing his way through, the poor chap that lost his ticket or had forgotten to purchase it – he has no idea which, the taste of bitter coffee, the repetitive submariner blips of a train station full of iPhones, Blackberries, Qwerty thumbs a clicking, the rushing whirr of the train timetable, weaving the commute, hands up for a cab, dashing the traffic, crushed in on the lift, eyes shifting, the exit as one body, the sudden dispersal of individuals. Each movement he would later admit was clunky, at times extremely sloppy. He lacked the control he needed, he carried that extra weight, he couldn’t manipulate the wobble around his belly. He lacked too the precision of timing necessary to achieve absolute aesthetic transmorphication, which only got worse as his dance went on, his energy slopping out of him rather than shooting like light to the edges of his open plan office. Tears, wails, looks of disbelief, shock, awe, the world was in plight and George was dancing. Years later he would recall the moment he took flight as his first ever act of pure altruism. There was no undoing the meltdown it had been building towards for years. Secretly – not even secretly, quite openly in fact, they had all said that this moment would arrive, that there was no way the market could sustain the chords of debt crying out, crying out, crying out. Towards the end of his dance his body was possessed by a sorrow, a premonition of the future, an understanding that this day was a cataclysm that the world of men had put in place for themselves, an unavoidable nasty deplorable mess all of our own doing. George carried this sentiment in his hands and feet, in his belly. His lungs could no longer breathe, he was spent, and yet he still danced, his eyes half closed, looking like a reveller, a devotee of Dionysus, an impassioned votariant of mis-rule, jigging his jiggy, a Nero with a conscience- for it all to be re-born it must all be pulled down. George understood this and his organism embodied it. Weaving through bodies, kicking his leg, big French kicks and tiny toe flicks, a random jazz outfit of movement. Sweat soaking through his white shirt, his trousers soaked to his legs. And then finally exhaustion. George could move no more. He had no idea how long he had been dancing. He was depleted of energy and his movement reduced to the pulse of his heartbeat and the pant of his breath as he collapsed at his desk, a computer monitor in front of him, an open plan office in shock surrounding him. The financial markets discarded about him, all collapsed and depreciated, his despicable dance done.

January 12, 2014

WILL

Will was alone, his ear to the door, the pain beyond it near splitting the wood. He heard the doctor issue orders and pushed himself away from the door as the Nurse, whose face and hands were covered in blood, dashed out of the bedroom to call for hot water. The sight of the blood made him shudder. Through the door he could see his wife lying pale and exhausted on the bed. The doctor was by her side talking, though she was barely able to listen. The whites of her eyes showed, her face contorted and then her whole body buckled in agony. Her scream wrenched the nurse back.

Will snatched the large black kettle from the hearth, dashed down the two flights of stairs to the pump which stood in the courtyard behind the tenement, thrashed it until he had filled the kettle with water, ran back up.

There was no wood or coal with which to build a fire to heat the water – nothing but two chairs and their table, at which they had imagined themselves to be King and Queen. Her screams were coming quicker. He put the kettle down, seized his small axe, and began to hack at the furniture in an unsentimental frenzy that reduced it to a dismembered heap.

There was no paper other than her bible with which to set the kindling he had split from the table. The book had survived three generations and contained the names of her father, mother, grandfather, grandmother and her great grandfather. He ripped pages from the middle, crushed them into balls, placed them in the grate, built up the fire with the kindling he had split from the furniture and topped it with the thick mutilated legs of the table.

Reaching from the hearth to the sideboard he retrieved a box of matches from a drawer, fumbled it and the entire contents scattered across the floor, forcing him to scramble on his hands and knees. He snatched up a match, struck it too hard. It exploded uselessly in an arc to the floor. He picked a second and forcing himself to be more gentle it flared alight. He put the match to the paper in the fireplace. The flame caught. It flicked and fought as though it would drown if it could not keep its hold. He began to blow to help it on. His first breath was too strong and he nearly put it out. With the second and then the third breath the wood began to crackle and spit as the flame grew. He grabbed the kettle and hung it on its hook above the fire, reached for another piece of wood, but stopped. For a moment he listened. Beyond the sound of his breathing and that of the fire there was nothing. Not one sound.

Into the silence the child cried.

He stood and turned to face the door. There was a flicker of movement in his hand. His chest rose and fell and he waited. After a while the child’s crying subsided. He heard whispering and the shuffling of feet before the door opened slowly to reveal the Nurse standing there, blood smearing the edge of her hairline. In her arms she held his babe, wrapped in the swaddling that his wife had so lovingly prepared.

It’s a boy, the Nurse said quietly, he’s a beauty.

He crossed over to her, his feet creaking on the floorboards. She held the bundle out and he reached awkwardly to take his son.

The boy felt fragile in his arms, his limbs soft and weak. His hands were out of proportion to the rest of him, the palms etched with delicately sugared lines. He watched in wonder as the little body began to move, flickering recitations of labour, his legs winding and weaving muscle together, his face and eyes in shuddery action.

Will lifted him to his lips and kissed his face, careful not to rub the boy’s new skin with the coarseness of his unshaven jaw. He felt the child’s hand run along his cheek, his long thin fingers hooking into his bottom lip, the tips touching his tongue before searching up, poking into his nose and then journeying to his eyes. The boy’s face was wrinkled and wise, and what the father saw was the mirror of himself and her, not at the beginning of life, but at the end, when all that is to be learnt is past and done.

Finally, he looked up, turned his head and saw his wife, lying still on their bed. Her face was ashen. The edges of her eyes were red and her lips were a pale bisque yellow with pink rims, deflated by the exhaustion of the end.

…..

I don’t want no pauper’s grave for her, Will said. His voice was gravelled in the back of his throat.

It’ll be no pauper’s grave, Will, said the Priest. He had comfortable furrows in his forehead.

I don’t want her lying on someone else, said Will, or someone pressing down on her, cause there’s no where else, because I can’t pay premium.

What else are you going to do with her man?

Will looked from the Priest, to the boy’s cot by the fireplace. He shook his head. His body trembled.

She needs a proper burial, lad, said the Priest. It’s what she would have wanted.

To live, that’s what she would have wanted.

I can understand your anger, Will-

I’m not angry, he said, looking directly at the Priest. I am broken hearted. His jaw was clenched. His short cropped hair was spiked. His eyes were wide and streaked red with grief. His big hands were fists by his side.

The Priest looked Will directly in the eyes. I don’t want to fight with you, Will, he said.

Will sniffed and shuffled on his feet. Then let me be.

There are no words of comfort that I can offer you, Will, said the Priest softly. I can only imagine your pain and that is enough to make it unbearable to me. I would be angry. I would be distraught if I were in your shoes. We are but men and we feel as men do. Sometimes I just want to scream at the sky. At him. God. My God. And I do. I walk out into the hills and I scream and shout. It might get it off my chest but does it do any good in the wider scheme of things? No. Does it rest my soul? No. We are small and insignificant to his will. And he tests us. When that test comes, we must rise to it, even if we know not why. There is more at stake than the everyday trials that we endure. There is more to life. There is reason even if that hidden will of God remains a mystery to us until the hour of hour of our death, it is there and we cannot run from it.

Will looked at the Priest. His gaze fell to the floor. She won’t be coming back, he said. That I know. What you speak of, I don’t know. The sun rises in the morning, that I know. It sets at night too. And here is something else that I know. She is lost to me. She is lost to the son that she suffered to create.

…..

Will sat in the bare room in the cold half dark, with the boy in his arms. The apartment was pungent with the mildew of decay. Getting onto his knees he placed the boy in his cot, moved to the fire, reached for the cloth that sat on the mantelpiece, put it under the hot handle of the kettle and poured the hot water into the bucket. He crossed to the sideboard and rummaged in a drawer until he found a sharp knife which he took, with the bucket, into the bedroom.

His hand hesitated before pulling back the sheet that covered her body. Her night gown was stained with blood. Using the knife to cut her out of her night clothes he revealed her body, naked, her arms coyly over her breasts, like a virgin, her body frigid in the shame of death.

From the bucket, he scooped up some water and began to wash her tenderly, his hands stroking her, tracing the contours of her features, passing down to her thighs, her legs, reclaiming her body for himself. Kneeling he rested his head on her belly and closed his eyes. For a few seconds.

He stood, brushed his hand through her hair, bent, kissed her softly on the lips and put his arms around her; not so much in an embrace but so that he could remove the soiled linen from the bed, which he did as gently as he could.

Stored in an old chest at the foot of the bed he found a clean and embroidered sheet, the one that had greeted them on their wedding night. This he unfolded and passed under her body before cocooning her in the cloth.

Once her chrysalis was complete he stood over her breathing quietly before he walked out of the bedroom to the cot, knelt and picked the boy up. The child was light and seemed to float in his arms. He carried his son out of the room across the hall to the door of his neighbour and knocked.

…..

He carried her body into the street, laying her on the bedroom door that he had already placed there and then wrapping the rope in a lattice pattern to secure her. The tenement families were watching him from their windows as he reached for the tools, the pick axe and spade that he had borrowed from a neighbour and tied them to the side of the door, mindful that they should not touch her. He took a piece of rope and threaded it through two holes that he had gouged in the top of the door, tied it into a circle, slung it over his shoulder and took up the slack.

He heaved his way by the figures who appeared in doorways, men removed their caps and bowed their heads; the Autumn wind ran like banshees though the windows and alleys in gusts that swirled around them stinging their ears. Will’s pace was heavy and slow. The tenements gave way to terraces which stood hunched up together, their inhabitants lining the streets, some with candles in their hands, others with flowers which they silently placed in the rope work as he passed.

…..

The night was mizzled and curtained in damp. The weight that he dragged dug into his shoulders. The wood of the door chafed the road, bouncing on the uneven surface, snapping the rope like reins and a whip. The boscage, the bosket and the brier cracked under the black mass of the night, the stars hidden behind a thick moss canopy of sweating clouds. His breath, which was frosted and sharp, vanished into the gloom that enclosed him. The tools clunked on the side of the door, their vibration jolting him.

Half a mile out of the town he turned left off the road to mount the hill, his feet slipping under the grass, the door tugging. The firm ground became soft steeped mud and sucked his feet down, forcing him to fight for each step. His thighs were aching, his hands numb, his damp hair flat to his scalp, the sweat under his coat cold and making for his bones. He struggled on in stubborn concentration, his head rolling from one side to the other. He fell, his hands sinking into the freezing clay. His trousers were soaked, the course serge a cold skin against his legs. He stumbled, dropped, stood, fell, fought, gasping, his lungs filling with the clag of the land. He stopped for breath resting his hands on his knees. And then on again, up into the hill where the sludge transformed to rock, sodded by bristled tufts of bracken. Thorns snagged and tore into his flesh, caught on her corpse, the devil’s claws trying to claim her for his own.

His feet struggled for grip with the elevation of the climb; his hands grabbing clumps of grass which came away. Feet scrambling and then his hands grasping, this time the grass holding. He lifted himself onwards, foot after foot.

The ground became earthen once more, firmer under his feet and more even. The clouds began to pull aside like curtains revealing veiled head dress of the moon. The walking was easier now and the sheer struggle gave way to relief and collapse as he arrived at their retreat. There, he had smiled and they had kissed and passed many a day there.

He unhitched himself from his load, removed his coat, took the pickaxe and began to hack at the ground. The earth loosened. He swapped the axe for the shovel, cleared the mud and gravelled rock, then once more took up the pick. He worked through the depth of the night. Dawn came and went, the sun rose. By the early afternoon he was finished and for a moment he rested.

Hoisting himself out exhausted and caked in mud, he crawled over to her, dragged her to the edge of the pit and loosened the ropes which held her to the door.

He unravelled the cloth from her face and looked upon her for the very last time. He lent forward, kissed her forehead, then her lips and pressed his cheek to hers. He was still for a long while. With a final kiss he closed up her shroud.

He eased himself back into the grave, took her into his arms, held her and then lowered her gently down so that she lay at his feet. He uttered no words.

He reached up for the pile of earth to the side of the pit and began to bury her slowly, never letting the rock or sediment fall heavily upon her. He buried her as if he was burying his most precious treasure.

When he felt his work could not damage her, he climbed out, shovelled the remaining earth to close up her grave.

Turning to look at their view stretching into the distance, he sat on the damp grass as a breeze blew through his hair and billowed beneath his shirt, chilling the sweat on his skin. Below the rocks, the land was shaded musty lemon, lime, harrowed greens, the slow animation of autumnal browns, sun shot reds, dry hay yellows, amber, cinnamon, deep mahogany, blushing auburn as wild moor blurred to dark ploughed land.

He thought about her in the landscape, her smile, her nose, her hair, her eyebrows – her intelligent eyebrows, which were pointed instead of curved when she listened or spoke.

He thought about the last times he had spent with her.

He thought about her pregnant, her full belly that never seemed to weigh her down or distemper her in any fashion, her smile as she stroked the bump, the distant look in her eyes as she felt their child move.

He remembered too her temper, that once she had thrown her wedding ring at him. He couldn’t recall why, or how the argument had finished, just remembered that she had.

Mostly, though, he remembered how she felt at night with her head on his chest, the conversation petered out. As her breathing became heavy, her body would twitch with the last flickerings of the day and always before him, she settled still to sleep.