Nathaniel Wyckoff's Blog

November 25, 2018

A Time for Vengeance

Chapter 1: Capture They came for him late one night.

Chapter 1: Capture They came for him late one night.Simon Mendez awoke to the sounds of horses’ hooves that came to an abrupt halt in the little alley that passed directly beneath his bedroom window. Lying motionless on his bed, he gazed briefly around his room. Wide rays of moonlight provided the only illumination. It took several moments for him to return to the waking world from his latest haunting and bizarre dream.

The dreams had been occurring more often lately. On far too many nights, Simon found his sleep disturbed by images of an elderly, bearded, humble-looking man clothed in a slightly tattered white shroud and wearing an expression of deep concern. Simon had never seen the man in real life before, yet tonight was different. In tonight’s vision, the old man identified himself as Simon’s great-great-grandfather, José Mendez, who had perished at the stake over one hundred fifty years earlier. Great-Great-Grandpa José also told Simon that he must be brave, that he must care for his mother and younger sisters, and - above all - that he must remain in full control of his emotions.

“What do you mean?” Simon asked.

“Be the rider in control of your animal self, my child,” answered José, “not the horse. There are important battles to be won, very soon.” Simon’s ancestor spoke in a very refined Spanish, in a dignified manner rarely heard among the common folk.

Tonight’s dream was the most puzzling and discomforting of all, and Simon had no idea what to make of it. At seventeen, Simon was used to mastery; he was tall, muscular and conversant in several languages.

“Be the rider in control of your animal self, my child, not the horse.” Simon prided himself on his sharp mind, yet still found his ancestor’s statement rather cryptic.

Now, José’s words reminded Simon that there were actual horses standing right outside his home. What were they doing there at this hour? Simon sat up and peered out the second-floor window behind him. Two dark-colored stallions stood in the alley, both attached to an ornate carriage. Simon wondered who its passengers could have been. Were they weary travelers in need of a place to stay for the night? Why would they choose to stop in Simon’s out-of-the-way hometown, Arboles, and why the Mendez home?

Simon rose from his bed and instinctively reached for the candlestick that typically stood atop a little nearby table. He sharply withdrew his hand before touching the object. The Mendezes were a family of conversos, or anusim (“forced ones”), as they often referred to themselves in private and veiled conversations. José Mendez and his righteous wife, Dina, had chosen to perish in the Inquisition’s flames back in 1492, rather than to renounce their Jewish faith, the faith for which so many of their own forebears had already fought and died. Yet, José and Dina’s children had lacked their parents’ degree of inner strength, and had chosen a feigned conversion to Catholicism over death.

Four generations later, the Mendez family lived outwardly like all of their Catholic neighbors, yet secretly practiced a number of ancient Jewish rituals when the neighbors were not around to see them. Every Friday, late in the afternoon, Simon’s mother, Sonia, lit a candle and placed it deeply inside a wooden cabinet in the kitchen, to mark the beginning of the twenty-five-hour-long Jewish Sabbath. The Mendezes privately referred to the day by its Hebrew name, Shabbat. Since Jewish law prohibited kindling fires, or even moving candles, on the Sabbath, the Mendez family made it a point to leave their candles alone for one day a week. Avoidance of fire on the Sabbath was one of a select few time-honored Jewish traditions that the Mendezes tried their best to uphold. Mr. Alejandro Ortiz, the well-liked local baker, was another secret Jew. He hosted an annual seder in honor of the first night of Passover, in his basement. And, every year on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, the Mendezes attempted to fulfill the Biblical commandment to fast, while going about their daily business.

Simon found it hard to be a converso, yet his parents’ secret stories - told in hushed tones, behind closed doors and drawn window shades - of Biblical figures like the Matriarchs, the Patriarchs, Moses, David, and Samson, inspired him to carry on, anyway. The mighty Samson, who smashed a Philistine temple and ended the lives of its oppressive occupants, was Simon’s favorite. Although Simon generally followed the Catholic crowds at church and school, he privately harbored a resentment that was growing more difficult to suppress with each passing day.

Marranos was the term that his classmates called Jewish converts to their religion. Oh, you think of us as pigs? Insincere brats, never to be trusted? How special. Let me kneel before you, my superior, Catholic-all-the-way-through-going-back-to-Saint-Augustine brethren. I’ll try not to let too much of my inferior Jewish shadow darken your royal countenance.

Few people even knew Simon by his real name. Biblical names from the Old Testament were considered a clear sign - literally, a dead giveaway - that a family practiced Judaism at home. So, seventeen-year-old Salvador Mendez lived as an upright, loyal, believing Catholic in all obvious respects. He obediently attended Mass every Sunday, along with his family, and Confession every Saturday night. He washed his hands in holy water (sometimes sorely tempted to spit in it), behaved himself around the girls, prayed with his classmates at Saint Ignacio’s, the local Catholic school, and tacitly went along with their behavior and remarks. Despite the occasional enraged outburst, Simon (as Salvador) generally made a clean-cut impression on the adults in his life. He studied well enough to convince his teachers of his sincerity and intelligence, but his real preference was to play with the exotic goodies that his mercantile father, Diego, often brought home as gifts for Simon and his younger sisters, Esperanza and Alma.

Esperanza’s name meant “hope.” She was born shortly after Portugal’s separation from the Spanish Empire. In 1640, Portugal’s King John IV ended that country’s sixty-year union with Spain. Portugal was now an independent kingdom once again. King John entered a peace treaty with Holland, and the two countries formed an alliance against their former master, Spain. For the Mendez family, this proverbial “chink in the armor” of the Spanish Empire was a positive omen. Spain was still an oppressive force in the world, but no longer the invincible juggernaut that it had once been. The Portuguese had a different set of rules for conversos; they were less restrictive, and allowed conversos to travel to their New World colonies. There was hope that the wicked Spanish Empire was on the road to collapse, and that its cold, powerful grip on Jewish existence would soon come to an end.

Diego and Sonia Mendez had invested their dreams into their baby daughter. Simon remembered the night on which his parents had chosen his new little sister’s name. Their greatest hope was that, someday, their children would be able to thrive as practicing Jews, committed to their highest ideals, rather than hiding their true selves and living in constant fear of persecution. From her birth, Esperanza’s parents and brother viewed her as a sign of a bright and hopeful future.

Now, at twelve, Esperanza did seem to shine as a beacon of hope to others. She was a thoughtful girl, an introspective young lady with a kind and benevolent nature. She had many friends, whom she always seemed to greet with a smile, a good word and a generous spirit. Esperanza was known to uplift other children when they were down, to break up fights and to get along with everybody. She also stood up fiercely for other kids when bullies insulted or picked on them. Indeed, where Esperanza Mendez went, there was both peace and hope.

Alma’s name meant “soul.” She was an impassioned eight-year-old girl who certainly did appear to put her heart and soul into everything that she did. When it was time to help her mother in the kitchen, she ran there and focused intently until the job was done. When she played with her siblings or friends, she shut out the rest of the world and concentrated fully on doing her very best. And when she didn’t get her way, there was no mistaking that she had been wronged. No place had a fury like Alma Mendez scorned.

Under the Spanish Inquisition, conversion to Catholicism generally saved a Jew and his or her family from immediate torture and death; however, it was far from a guarantee of equality or tolerance. The conversos’ second-class status involved more than the jeers and taunts of a society that viewed them with constant suspicion of becoming relapsos; there were legal restrictions, as well. Conversos could not travel to Spain’s conquered lands in the New World; those colonies were off limits to anybody who could not produce documentation of limpieza de sangre, “purity of blood.” It took four generations to cleanse the impure Jewish blood from the veins of the marrano; thus spoke the Church’s prevailing religious prejudice. Simon and his sisters technically qualified to travel to the New World, as their great-grandfather, José’s son, had converted to Catholicism; however, splitting up the family would not have been a good idea. Most of the inhabited Earth was not much more hospitable to Jews than was the Spanish Empire. Nevertheless, Diego Mendez had managed to build a fairly vigorous trade with merchants in other countries. Many of his trading partners were other secret Jews, who maintained an extensive commercial network amongst themselves. Thus, numerous objects from various remote corners of the globe adorned the Mendez family home.

Of all the international gifts from his father, Simon most enjoyed to amuse himself with authentic weapons, especially those from the Orient. He was very protective of those playthings; he dared not risk showing them off to his friends, or even revealing their locations to his family. Simon imagined that his shuriken conferred a competitive advantage; few, if any, potential attackers in Spain - and certainly in his little hometown - even knew of such weapons or were prepared to defend against them. Shuriken were Japanese throwing stars, little roundish pieces of metal with protruding sharp blades. Ninja warriors in faraway Japan used them against their enemies, so Simon liked to refer to them as “Ninja stars.” Simon’s nunchakus were additional gems. They consisted of two short sticks tied together with a chain. Simon had spent many hours secretly practicing the art of spinning them; by now, he was quite proficient at holding onto one stick and spinning the other into a twirling cloud of rage that could easily repel any opponent.

Walking across his room, Simon had trouble taking his mind off of tonight’s dream. José Mendez had called him “Shimon,” the original Hebrew form of “Simon,” rather than “Salvador.” Virtually nobody else, beyond his immediate family, even knew him by that name in the first place. Even Simon had only learned of his Jewish name at his Bar Mitzvah ceremony, a brief and secret affair that had occurred early one Saturday morning, four years earlier, in the Ortiz family’s basement. There, with his sandy-brown hair covered by a small black cap, he had been called “Shimon ben (the son of) David,” and had then hunched over and recited some ancient blessings while gazing into a tiny Torah scroll (contraband these days). The adults, also all conversos, had smiled at him and congratulated him on officially becoming a man. If the elderly gentleman in his dream knew Simon’s Jewish name, then the dream itself must have been some kind of Divine vision. That thought made him shudder momentarily when he grasped the doorknob.

As he left his bedroom, Simon heard several loud knocks emanating from the front door of the house. The sequence of four or five knocks repeated itself a few seconds later, this time with greater urgency. Simon dashed downstairs, leaping over the bottom few steps and landing on the stone floor of the front room. There, in the dim glow of the several candles that still burned, he noticed that his parents and sisters had also been aroused from their slumbers. All of them now gathered in the front room, standing in their bedclothes, Alma and Esperanza murmuring to each other about what was going on and how tired they were. On reaching the front door, Simon put his hand on the knob, turned it and pulled the door open, expecting to find a weary traveler who would request a place to stay for the night and, perhaps, a cup of fresh water.

He wasn’t expecting the Spanish Inquisition. There, on the Mendez family doorstep, stood Father Alonso Garcia, the priest who headed the local branch of the Holy Office. Father Garcia was a man of slight build, with a powerful voice and a diabolical-looking goatee that complemented his constantly stern expression. Simon had never seen the man smile. He didn’t speak much, either; his grouchy manner said a lot, though. Most people talked about him with reverence, and children generally seemed afraid of him. Simon, though, regarded Father Garcia as a little joke, a short man overcompensating for his small size with his cocky “holier-than-thou” mannerisms. I could take him in a fight any day, Simon often thought, when Alonso Garcia was in view. Tonight, the moonlight gave the priest, dressed in black robes and boots, a somewhat supernatural appearance. Father Garcia stood by the doorway for a brief moment before letting himself in, wordlessly pushing Simon out of the way as he marched imperiously into the Mendez family’s living room.

Sonia was the first to speak. “Why, good evening, Father Garcia! It’s so late…is everything all right? I mean…to what do we owe this honor? Can I get you anything?”

He gave Mrs. Mendez a severe look. “I am not here to make a social call, ma’am,” he uttered, in a gravelly voice. “I have come to see Diego Mendez.”

Diego stepped forward and addressed the visitor. “Father Garcia, here I am. Is everything all right?”

“I’m not so sure,” answered the priest. “We have a rather urgent matter to discuss. Your presence is requested immediately at the Holy Office of the Inquisition.”

Diego took a step backward, in obvious surprise. “The Inquisition? Why? What’s going on?”

Alonso Garcia counteracted Diego’s retreat by taking another couple of steps forward and then speaking directly into Diego’s face. “Your name came up during a recent inquiry.”

Inquiry? thought Simon. I’m not fooled. I know what goes on at your “inquiries.”

Father Garcia continued: “It seems that there’s been a matter of Judaizing.”

“Judaizing? What?” asked Diego, sounding shocked. Simon heard a loud gasp from his mother and Esperanza.

“Mama, what does ‘Judaizing’ mean?” asked Alma, innocently.

“I’ll tell you later, dear,” whispered Sonia.

Father Garcia’s voice became ice, cold and sharp as a razor. As he continued speaking, contempt spilled out of him like blood from an open wound. He forgot any genteel manners that his parents or the Church might have instilled in him during some distant past life; spit sprayed and hate flew from his cruel mouth. “It seems that some lessons in the Jewish Torah have been taught in various homes throughout the neighborhood. This clandestine - and illegal - activity has been going on for over a year.”

My club, thought Simon. If only I had my club. That guy would be on the floor in a second and out cold. But I’ve lost the element of surprise. Still, maybe I can regain it…

Simon surreptitiously took several steps backward, toward the staircase, while Alonso Garcia continued his rant: “We have been investigating the nature of these criminal offenses, and your name arose. You, Mr. Mendez, were identified among the teachers of the Hebrew Bible lessons that have been given at odd hours, and in various private closets and basements throughout this city.”

Sonia let out another gasp. “There must be some mistake, Father,” she said, her voice exuding worry. “Diego w-w-would never be involved in illegal activities!”

Simon did not like the direction of this conversation. If that little sluggard thinks he can just burst in here and start pushing us around, he’s got another thing coming. He’s about to make a social call with one of my most trusted buddies. He had been gradually inching his way toward the staircase, and had felt the back of his left foot bump against the bottom step right at the moment that his mother had uttered the word “activities.”

“Make no mistake about it, señora,” replied Father Garcia, ceremoniously lifting his right hand into the air, index finger extended. He wagged his finger in the air several times, and then said, “We cannot have our beloved and holy town of Arboles polluted with this filth.”

“Polluted with this filth?” Please. Simon rolled his eyes, grateful for the nighttime darkness that hid his scornful gesture. An instant later, he was walking up the staircase at a brisk pace. His bedroom door was still ajar, and the moonlight emanating from that room provided a decent view of the stairs as he ascended them. While he climbed, he heard Alonso Garcia’s grim voice exclaiming the bone-chilling proclamation that would alter the course of Mendez family history.

“Diego Mendez, you have been named in a criminal matter of Judaizing, and are hereby ordered to the Holy Office of the Inquisition at once, to answer to the charges that have been brought against you.”

As soon as he had finished speaking, Alonso Garcia loudly snapped his fingers, summoning two overgrown thugs to step into the home through the front doorway. They were soldiers, both dressed in uniforms and carrying long, sharp pointed rapiers - the finest in modern, seventeenth-century military gear. Simon had not a second to spare. His club might be no match against those ruffians, but what about his morning star?

While his mother shrieked, Simon ran into his bedroom, quickly entered the closet, and squatted in front of the most important item that it contained. It was a large wooden chest that stored some of Simon’s smaller articles of clothing, boots and valuables. The chest was one of Simon’s several secret locations in which he liked to keep his special playthings.

Miraculously, the box’s lid did not creak this time when Simon threw it open. He needed no light to guide him as he rapidly rummaged through the chest. His fingers were already very well acquainted with its contents, and at the bottom, he soon found the item that he wanted. He closed his right hand around the weapon’s shaft, pulled it out of the chest, and rushed out of his room. Yes, the morning star, a massive club whose attached ball was studded with sharp spikes, would be tonight’s weapon of choice.

At the bottom of the staircase, he found pandemonium. Alonso Garcia’s hoods held Diego in a tight grip, one solder grasping each of the man’s arms. Sonia and the girls busily assaulted them with vases and cutlery, but their furious attacks seemed to have little effect. Clearly, these men were hardened fighters, trained to withstand fiercer assaults than anything that Sonia and her daughters could do to them. Diego, for his part, resisted his arrest as fiercely as possible. He was generally a calm, quiet, calculating man, not accustomed to combat of any sort. Still, he opposed his captors with a surprising ferocity, shouting epithets and kicking madly; within half a minute after their grabbing him, he had reduced the pair of soldiers to dragging him across the floor.

Simon rushed at the pair of soldiers with his mace and began swinging. The thug on Diego’s right responded by unsheathing his sword and taking a couple of swings of his own, somehow still maintaining a lock on Mr. Mendez’s left arm. The sword slightly nicked Simon’s left elbow, but in his rage, he barely felt a thing.

Father Garcia, who had disappeared, began screaming orders from outside the house. “The darbies, you dolts!” he called from the comfort of his carriage’s back seat. “Use the darbies! And hurry it up already! We still have another couple of victims to pick up before tomorrow morning!”

Darbies were metal restraints that the authorities clasped around the wrists of arrestees, to restrain their movements.

Both soldiers paused briefly at the threshold of the house. Using his left hand, the taller soldier dutifully pulled a long chain from his belt. Smirking, he handed one end of it to the shorter one, who took it and clasped the metal loop at its end around Diego’s right wrist. Then, the two brutes silently lifted Diego and started carrying him outside, toward the carriage. Garcia continued to bark meaningless orders at them, and Simon figured that the whole neighborhood could hear his shouts. Naturally, nobody did anything to shut him up; everybody was either too intimidated, too indifferent or both. From the corner of his eye, Simon spotted a neighbor opening his front door and just standing there, staring. Newly lighted candles appeared in a couple of windows; those who sat by them and watched the scene unfold apparently needed some entertainment in their otherwise busy, humdrum lives. Not a single individual bothered to offer help, or even stepped outside to question the players in this twisted event. Even a small number of courageous people could have easily ganged up on Diego’s captors and stopped the horror that now unfolded; their silence and complicity spoke volumes. How many more families had been destroyed, how many other innocent victims mercilessly robbed of their lives and dreams, over the past century and a half of madness? How many fingers had been lifted to put a stop to the evil that was the Spanish Inquisition?

If anybody in the surrounding homes managed to sleep through Alonso’s rude shouts, Sonia and her daughters’ shrill wails would have awoken them. Alma’s repeated, panicked cries of “No! Don’t take away my Papaaaaaa!!” pierced Simon like daggers stabbing into his heart. Yet, her desperate screams were to no avail. She gripped her arms tightly around Diego’s legs, and her eyes sprayed mad tears while her infuriated mouth screamed fierce cries of despair and protest.

On reaching the carriage, the shorter soldier clinically pried Alma away from her father and callously tossed her several meters away. When the vehicle’s door was open and Alonso’s pathetic, impatient figure became visible, Sonia Mendez gave up her fight. She collapsed into a heap on the ground and sobbed, her spirit smothered.

Esperanza and Alma, however, refused to quit. “I’ll burn down your carriage!” screeched Esperanza. She turned and ran back into the house.

Not to be outdone, Alma shouted, “I’ll kill your horses!” The young girl dashed back into the house and emerged an instant later, wielding a steak knife. She rushed at the nearest horse with the knife and tried to stab it. Over their screams, Simon heard the cruel, arrogant laughter of his father’s three abductors. They had clearly won this round, and were now flaunting their victory.

Esperanza emerged from the house, stridently carrying a candle and trying hard to stop the rushing air from blowing it out. It was too late to make good on her threat, though; the horses were already on their way.

Simon stared at the receding carriage, hatred radiating from him in waves. His outraged voice stabbed the cool spring air: “I’ll get you for this, Alonso Garcia!” He then threw his morning star in wild frustration, and watched as it embedded itself into the trunk of a nearby tree. His mother’s and sisters’ blood-curdling screams and wails continued to disrupt the calm of that fateful Friday night, belying the notion that the Jewish Sabbath served as a day of rest.

Simon knew that he had to get past his despair if there was any hope of saving his father. Saving Diego was now the only thing on Simon’s mind. The capture of Simon’s father was the very last straw. Simon despised the Inquisition, and burned for vengeance. You’ll never get away with this, Alonso, you pompous little creep. I’ll find a way to make you pay - in blood. ORDER NOW FROM AMAZON

Just $0.99 from now through December 8!

Published on November 25, 2018 06:59

August 21, 2017

I Started with an Audience of One

Becoming an author has been a long, strange trip. Though I have only been actively producing and publishing books for several years, writing has actually been a lifelong pursuit. Today, with the first three novels in a series completed and a fourth one on the way, I want to take a moment to give my readers a sense of what drives Nathaniel Wyckoff the Author.

Reading was a major part of my childhood. It was a skill that I picked up quickly and easily, one that I instantly enjoyed. Books were a big deal in our house, and at an early age, I found reading stories to be my favorite activity. Listening to stories was almost as fun as reading them.

My father was our family’s master storyteller. When putting my brothers and me to bed at night, he used to invent all sorts of exciting and imaginative stories on the spot, keeping us fascinated by his cast of recurring quirky characters. Most of his tales ended with, “And then, the boys went home, took baths, put on their pajamas, and went to sleep. Now, you go to sleep.” Then, he would turn into Sandy the Sandman, offering us magic sleeping dust for our eyes, in the colors of our choice. From him, I learned to dream up on-demand stories about almost anything, a skill that would serve me well when entertaining my own children.

When an elementary school teacher had the class write down our own creative stories and then have them bound into little books, I was a natural. Having learned from my father how to imagine impossibly awesome scenarios, far beyond the limits of normal experience and the natural world, I had no trouble coming up with a tale of aliens from outer space invading people’s homes and making life unbearable for them (eventually to be defeated, of course). I drew the aliens to resemble those from the Atari 2600’s version of the “Space Invaders” video game. My teacher was flabbergasted, and praised me to my parents, as having “such an imagination!” I recall telling my mother that, someday, my little book would become a bestseller. That didn’t actually happen, but I didn’t give up.

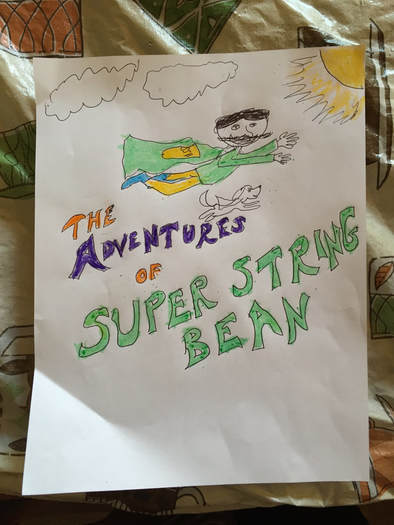

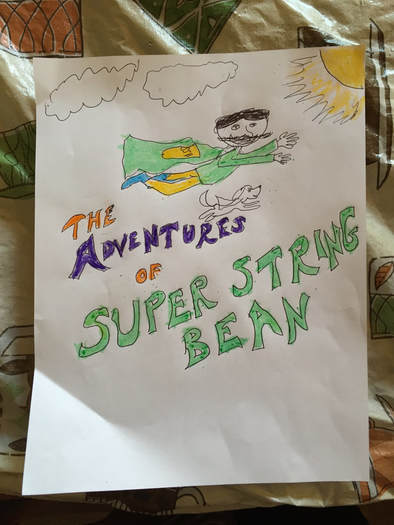

A major event in my writing saga was a comic book of my own creation. One day, probably to relieve my San Fernando Valley boredom, I sat down and created a comic book character named “Super String Bean. ” He was a regular guy named Joe Binny, who gained temporary super powers by eating string beans. Of course, he used his super powers to fight crime. His archenemy was a wizard named “Lermin.” (“Merlin” was taken.) Though I did not consider myself a visual artist, I wrote and drew a number of issues of the Super String Bean comic book, for my younger brother’s entertainment. Super String Bean inspired him to take up comic book art, as well; he produced some “Captain Cheerio” comics for my amusement. His comics usually had me cracking up with laughter.

My kids enjoyed this recent reproduction my Super String Bean comic book. Alas, no original copies remain, but the memory and inspiration live on. An audience of one does not make a writing career, and my writing dreams were somewhat suppressed for a while. At the time, young people were consistently told to be practically minded, and the image of the starving, alcoholic writer who barely ekes out a livelihood loomed large in the broader culture, dissuading me from pursuing writing in a serious way. (Think of Edgar Allen Poe.)

My kids enjoyed this recent reproduction my Super String Bean comic book. Alas, no original copies remain, but the memory and inspiration live on. An audience of one does not make a writing career, and my writing dreams were somewhat suppressed for a while. At the time, young people were consistently told to be practically minded, and the image of the starving, alcoholic writer who barely ekes out a livelihood loomed large in the broader culture, dissuading me from pursuing writing in a serious way. (Think of Edgar Allen Poe.)

Still, I knew that I had an inner author waiting for the right time to be unleashed. In an enjoyable ninth-grade English course, I wrote an essay and submitted it to a writing contest, winning a cash prize; it was a bona fide validation of my ability, through writing, to produce something that others valued. Courses that involved creativity, innovation and experimentation were generally those that I enjoyed most. Though I also enjoyed scientific subjects, and did well in those areas, writing remained very important to me; abstracts, lab reports, and technical papers were usually fun to compose. While attending university, I often contributed articles and opinion pieces to a Jewish student newsmagazine.

Fast-forward a number of years. With a family of several young, active children and a tenuous research position that wouldn’t last forever, I had to do something. A parenting magazine included an advertisement for a writing course: “We need people to write children’s literature.” Since I was already quite adept at telling my kids fanciful tales at a whim, I gave it a shot. The course taught me some valuable guidance regarding point of view, setting, character development, and related topics. Combined with the mandatory stories that I told the kids on our morning drives to school, the course helped me to produce a short story about some kids who discover a treasure map in their broken robot and try to return the treasure that it reveals, being blocked by pirates along the way. For a while, that story didn’t go anywhere; traditional book and magazine publishers typically have rejection rates of around 98%. Like Super String Bean, my stories eventually became another suppressed but unforgettable part of my past.

Around 2010, self-publishing started to become a real phenomenon, and began to disrupt the publishing industry; for me, it presented a new opportunity. A good friend compiled dozens of his blog posts into a book, and had them published through an independent publishing service. I marveled at his ability to do so. Shortly thereafter, I took up my story of pirates, kids and robots once more; I was determined to write a full-length novel. I added further adventures, and then tried to get the novel in front of several different literary agents and publishers. Their rejections annoyed me; I had no patience to wait several years to be “discovered.” Instead, I followed my friend’s example and pursued self-publishing. I thought of a title, Yaakov the Pirate Hunter , that encapsulated the story in a fun, concise way. For the cover, I threw together a do-it-yourself monstrosity using the publishing service’s template; a toy treasure chest in the sand, blurrily photographed via a crummy cell phone, would have to do. I added a royalty-free stock photo of the large synagogue in Djerba (read Yaakov the Pirate Hunter to find out why), and voila! I was now a (terrified) self-published author. Is that a blurry picture of a sharp treasure chest, or a sharp picture of a blurry treasure chest? Following my initial, timid entry into “Bookland,” a friend who is an accomplished writer gave me some excellent advice for Yaakov the Pirate Hunter. She recommended that I rework some scenes, flesh out some characters and settings, and publish a revised edition of the book, followed by a sequel. Though it was not easy for me to hear my work being critiqued, I knew that she was right. Eventually, I followed her advice, and released a second edition, with a high-resolution photo on its cover.

Is that a blurry picture of a sharp treasure chest, or a sharp picture of a blurry treasure chest? Following my initial, timid entry into “Bookland,” a friend who is an accomplished writer gave me some excellent advice for Yaakov the Pirate Hunter. She recommended that I rework some scenes, flesh out some characters and settings, and publish a revised edition of the book, followed by a sequel. Though it was not easy for me to hear my work being critiqued, I knew that she was right. Eventually, I followed her advice, and released a second edition, with a high-resolution photo on its cover.  It still doesn't scream, "pirate hunter," but what a nice picture of a compass! As it true of anything else worth doing, being an author is a perpetual learning experience. Joanna Penn’s podcast, John Locke’s book, Nick Stephenson’s course, and Monica Leonelle’s many instructional materials have been invaluable, along with feedback from family members, friends, reviewers, and my growing army of perceptive proofreaders. I now have a wealth of support from readers and fellow authors who believe in me, along with a talented cover designer (see her work below!), and have recently been able to assist others along their writing journeys.

It still doesn't scream, "pirate hunter," but what a nice picture of a compass! As it true of anything else worth doing, being an author is a perpetual learning experience. Joanna Penn’s podcast, John Locke’s book, Nick Stephenson’s course, and Monica Leonelle’s many instructional materials have been invaluable, along with feedback from family members, friends, reviewers, and my growing army of perceptive proofreaders. I now have a wealth of support from readers and fellow authors who believe in me, along with a talented cover designer (see her work below!), and have recently been able to assist others along their writing journeys.

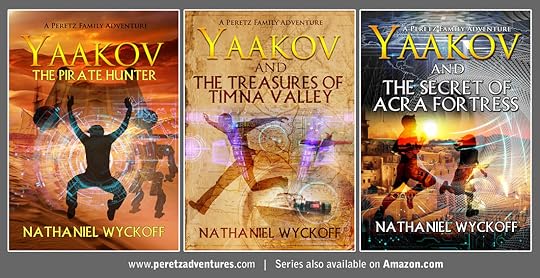

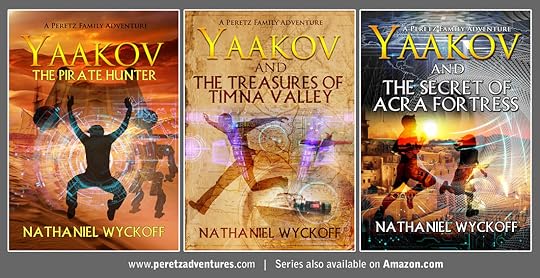

I thank you for joining me on my adventures, and look forward to what the future holds! Masterful artwork by my amazing graphic designer, Jeanine Henning

Masterful artwork by my amazing graphic designer, Jeanine Henning

Reading was a major part of my childhood. It was a skill that I picked up quickly and easily, one that I instantly enjoyed. Books were a big deal in our house, and at an early age, I found reading stories to be my favorite activity. Listening to stories was almost as fun as reading them.

My father was our family’s master storyteller. When putting my brothers and me to bed at night, he used to invent all sorts of exciting and imaginative stories on the spot, keeping us fascinated by his cast of recurring quirky characters. Most of his tales ended with, “And then, the boys went home, took baths, put on their pajamas, and went to sleep. Now, you go to sleep.” Then, he would turn into Sandy the Sandman, offering us magic sleeping dust for our eyes, in the colors of our choice. From him, I learned to dream up on-demand stories about almost anything, a skill that would serve me well when entertaining my own children.

When an elementary school teacher had the class write down our own creative stories and then have them bound into little books, I was a natural. Having learned from my father how to imagine impossibly awesome scenarios, far beyond the limits of normal experience and the natural world, I had no trouble coming up with a tale of aliens from outer space invading people’s homes and making life unbearable for them (eventually to be defeated, of course). I drew the aliens to resemble those from the Atari 2600’s version of the “Space Invaders” video game. My teacher was flabbergasted, and praised me to my parents, as having “such an imagination!” I recall telling my mother that, someday, my little book would become a bestseller. That didn’t actually happen, but I didn’t give up.

A major event in my writing saga was a comic book of my own creation. One day, probably to relieve my San Fernando Valley boredom, I sat down and created a comic book character named “Super String Bean. ” He was a regular guy named Joe Binny, who gained temporary super powers by eating string beans. Of course, he used his super powers to fight crime. His archenemy was a wizard named “Lermin.” (“Merlin” was taken.) Though I did not consider myself a visual artist, I wrote and drew a number of issues of the Super String Bean comic book, for my younger brother’s entertainment. Super String Bean inspired him to take up comic book art, as well; he produced some “Captain Cheerio” comics for my amusement. His comics usually had me cracking up with laughter.

My kids enjoyed this recent reproduction my Super String Bean comic book. Alas, no original copies remain, but the memory and inspiration live on. An audience of one does not make a writing career, and my writing dreams were somewhat suppressed for a while. At the time, young people were consistently told to be practically minded, and the image of the starving, alcoholic writer who barely ekes out a livelihood loomed large in the broader culture, dissuading me from pursuing writing in a serious way. (Think of Edgar Allen Poe.)

My kids enjoyed this recent reproduction my Super String Bean comic book. Alas, no original copies remain, but the memory and inspiration live on. An audience of one does not make a writing career, and my writing dreams were somewhat suppressed for a while. At the time, young people were consistently told to be practically minded, and the image of the starving, alcoholic writer who barely ekes out a livelihood loomed large in the broader culture, dissuading me from pursuing writing in a serious way. (Think of Edgar Allen Poe.)Still, I knew that I had an inner author waiting for the right time to be unleashed. In an enjoyable ninth-grade English course, I wrote an essay and submitted it to a writing contest, winning a cash prize; it was a bona fide validation of my ability, through writing, to produce something that others valued. Courses that involved creativity, innovation and experimentation were generally those that I enjoyed most. Though I also enjoyed scientific subjects, and did well in those areas, writing remained very important to me; abstracts, lab reports, and technical papers were usually fun to compose. While attending university, I often contributed articles and opinion pieces to a Jewish student newsmagazine.

Fast-forward a number of years. With a family of several young, active children and a tenuous research position that wouldn’t last forever, I had to do something. A parenting magazine included an advertisement for a writing course: “We need people to write children’s literature.” Since I was already quite adept at telling my kids fanciful tales at a whim, I gave it a shot. The course taught me some valuable guidance regarding point of view, setting, character development, and related topics. Combined with the mandatory stories that I told the kids on our morning drives to school, the course helped me to produce a short story about some kids who discover a treasure map in their broken robot and try to return the treasure that it reveals, being blocked by pirates along the way. For a while, that story didn’t go anywhere; traditional book and magazine publishers typically have rejection rates of around 98%. Like Super String Bean, my stories eventually became another suppressed but unforgettable part of my past.

Around 2010, self-publishing started to become a real phenomenon, and began to disrupt the publishing industry; for me, it presented a new opportunity. A good friend compiled dozens of his blog posts into a book, and had them published through an independent publishing service. I marveled at his ability to do so. Shortly thereafter, I took up my story of pirates, kids and robots once more; I was determined to write a full-length novel. I added further adventures, and then tried to get the novel in front of several different literary agents and publishers. Their rejections annoyed me; I had no patience to wait several years to be “discovered.” Instead, I followed my friend’s example and pursued self-publishing. I thought of a title, Yaakov the Pirate Hunter , that encapsulated the story in a fun, concise way. For the cover, I threw together a do-it-yourself monstrosity using the publishing service’s template; a toy treasure chest in the sand, blurrily photographed via a crummy cell phone, would have to do. I added a royalty-free stock photo of the large synagogue in Djerba (read Yaakov the Pirate Hunter to find out why), and voila! I was now a (terrified) self-published author.

Is that a blurry picture of a sharp treasure chest, or a sharp picture of a blurry treasure chest? Following my initial, timid entry into “Bookland,” a friend who is an accomplished writer gave me some excellent advice for Yaakov the Pirate Hunter. She recommended that I rework some scenes, flesh out some characters and settings, and publish a revised edition of the book, followed by a sequel. Though it was not easy for me to hear my work being critiqued, I knew that she was right. Eventually, I followed her advice, and released a second edition, with a high-resolution photo on its cover.

Is that a blurry picture of a sharp treasure chest, or a sharp picture of a blurry treasure chest? Following my initial, timid entry into “Bookland,” a friend who is an accomplished writer gave me some excellent advice for Yaakov the Pirate Hunter. She recommended that I rework some scenes, flesh out some characters and settings, and publish a revised edition of the book, followed by a sequel. Though it was not easy for me to hear my work being critiqued, I knew that she was right. Eventually, I followed her advice, and released a second edition, with a high-resolution photo on its cover.  It still doesn't scream, "pirate hunter," but what a nice picture of a compass! As it true of anything else worth doing, being an author is a perpetual learning experience. Joanna Penn’s podcast, John Locke’s book, Nick Stephenson’s course, and Monica Leonelle’s many instructional materials have been invaluable, along with feedback from family members, friends, reviewers, and my growing army of perceptive proofreaders. I now have a wealth of support from readers and fellow authors who believe in me, along with a talented cover designer (see her work below!), and have recently been able to assist others along their writing journeys.

It still doesn't scream, "pirate hunter," but what a nice picture of a compass! As it true of anything else worth doing, being an author is a perpetual learning experience. Joanna Penn’s podcast, John Locke’s book, Nick Stephenson’s course, and Monica Leonelle’s many instructional materials have been invaluable, along with feedback from family members, friends, reviewers, and my growing army of perceptive proofreaders. I now have a wealth of support from readers and fellow authors who believe in me, along with a talented cover designer (see her work below!), and have recently been able to assist others along their writing journeys.I thank you for joining me on my adventures, and look forward to what the future holds!

Masterful artwork by my amazing graphic designer, Jeanine Henning

Masterful artwork by my amazing graphic designer, Jeanine Henning

Published on August 21, 2017 05:57

May 7, 2017

A Hearty "Shalom Aleichem" to You, Mon!

What comes to mind when you think of Jamaica? The name of that tiny Caribbean island most likely conjures thoughts of sunny tropical beaches, sugar cane, reggae music, and dreadlocks. Less well-known is the island’s tumultuous history as a haven for pirates, as well as some clever and courageous Jews who fought valiantly to keep the Spanish Inquisition off their backs.

Christopher Columbus discovered the island in 1494, on his second voyage. Some historians believe that he was a Jew fleeing the Inquisition; today, members of Jamaica’s tiny remaining Jewish community claim Columbus as a forebear. The Columbus family gained ownership of Jamaica and control over the Church there, making Jamaica a safe haven from the Inquisition. The Jews of Jamaica no longer had to live in fear of being tortured or burned at the stake.

That situation lasted for over a century, until the Spanish government found an excuse to send the Inquisition to Jamaica. By that time, the island was ripe for conquest, and Jews played a pivotal role in liberating Jamaica from Spanish rule.

In 1655, a Jewish pilot named Campoe Sabada navigated an English invasion fleet into Jamaica’s harbor, to wrest the island from Spain. The Spanish soon surrendered Jamaica to England. Under English rule, Jamaica’s Jews were able to live openly as Jews. Spanish and Portuguese Jews from all over the New World immigrated to Jamaica, as well; there, they could live freely and prosper.

Jamaica also became a home for pirates. The island’s Port Royal attracted French and English buccaneers, who found in that town many customers for their loot stolen from Spain, in addition to the sensuous pleasures that they craved and the ability to repair their ships.

As the pirates prospered, so did Jamaica’s Jewish community. Between 1666 and 1670, led by the famed English pirate Henry Morgan, the buccaneers repeatedly invaded the Spanish colonies of the New World and forcibly robbed the Spaniards of their wealth. They were backed by the Jewish merchants of Port Royal. Morgan carried out six raids on Spanish ports, and finally in brought the Spanish Empire to its knees. Spain’s dominance in the New World came to an end.

Throughout Jamaica’s history, there were rumors that Christopher Columbus had discovered a secret gold mine while on the island. In 1663, three wealthy Dutch Jewish men and their sons trekked into the mountains of Jamaica to search for the mine. They claimed that Jamaica’s secret Jews had told them about the mine during the era of Spanish rule, and convinced the English King Charles to back their two-year expedition. Charles’s patience only lasted one year, though; due to their failure to locate the mine, Charles accused them of fraud and expelled them from Jamaica. However, by the time the king’s ordered reached Jamaica in 1664, the gold-seeking Jews from Holland were already gone.

One of those Dutch Jews, Abraham Cohen Henriques, may have returned to Jamaica to continue his search. In 1670, he secretly staked his claim to a large piece of property near the mouth of northern Jamaica’s Oracabessa River. Others, too, have tried to locate the mine, but it still has never been found. Does Columbus’s legendary mine actually exist? Ainsley Henriques, Abraham Cohen Henriques’s descendant and the current leader of Jamaica’s Jewish community, is quite skeptical. “The gold is in the story,” he has asserted. (1) However, one can never be too sure.

Despite numerous difficulties, the Jamaican Jewish community continued to thrive after its liberation from Spanish rule. The Jewish population has dwindled to fewer than 200 persons. Still, the aged Sha’are Shalom synagogue continues to function in Kingston, near the southern coast. An Israeli-born caterer named Vered Maoz runs a kosher food business in Kingston, as well. (2) In addition, Chabad has recently established a presence in Montego Bay, at the island’s north side, to provide visitors with opportunities to engage in Jewish practice. (3) Ainsley Henriques hosts Jewish history conferences, and opened a museum near Sha’re Shalom. Henriques aims to inform the public about Jamaica’s once-flourishing Jewish life. (4)

Pirate combat, a lost gold mine, stunning scenery, and a rich history spanning more than five centuries: Jamaica remains a fascinating locale, still ripe for new discovery…and adventure novels. Stay tuned!

References:

Kritzler, Edward, Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean. New York: Random House (2008).http://www.aish.com/jw/s/Jews-of-Jamaica.htmlhttp://www.jewishjamaica.com/general-info/http://www.haaretz.com/jewish/features/1.647047

Christopher Columbus discovered the island in 1494, on his second voyage. Some historians believe that he was a Jew fleeing the Inquisition; today, members of Jamaica’s tiny remaining Jewish community claim Columbus as a forebear. The Columbus family gained ownership of Jamaica and control over the Church there, making Jamaica a safe haven from the Inquisition. The Jews of Jamaica no longer had to live in fear of being tortured or burned at the stake.

That situation lasted for over a century, until the Spanish government found an excuse to send the Inquisition to Jamaica. By that time, the island was ripe for conquest, and Jews played a pivotal role in liberating Jamaica from Spanish rule.

In 1655, a Jewish pilot named Campoe Sabada navigated an English invasion fleet into Jamaica’s harbor, to wrest the island from Spain. The Spanish soon surrendered Jamaica to England. Under English rule, Jamaica’s Jews were able to live openly as Jews. Spanish and Portuguese Jews from all over the New World immigrated to Jamaica, as well; there, they could live freely and prosper.

Jamaica also became a home for pirates. The island’s Port Royal attracted French and English buccaneers, who found in that town many customers for their loot stolen from Spain, in addition to the sensuous pleasures that they craved and the ability to repair their ships.

As the pirates prospered, so did Jamaica’s Jewish community. Between 1666 and 1670, led by the famed English pirate Henry Morgan, the buccaneers repeatedly invaded the Spanish colonies of the New World and forcibly robbed the Spaniards of their wealth. They were backed by the Jewish merchants of Port Royal. Morgan carried out six raids on Spanish ports, and finally in brought the Spanish Empire to its knees. Spain’s dominance in the New World came to an end.

Throughout Jamaica’s history, there were rumors that Christopher Columbus had discovered a secret gold mine while on the island. In 1663, three wealthy Dutch Jewish men and their sons trekked into the mountains of Jamaica to search for the mine. They claimed that Jamaica’s secret Jews had told them about the mine during the era of Spanish rule, and convinced the English King Charles to back their two-year expedition. Charles’s patience only lasted one year, though; due to their failure to locate the mine, Charles accused them of fraud and expelled them from Jamaica. However, by the time the king’s ordered reached Jamaica in 1664, the gold-seeking Jews from Holland were already gone.

One of those Dutch Jews, Abraham Cohen Henriques, may have returned to Jamaica to continue his search. In 1670, he secretly staked his claim to a large piece of property near the mouth of northern Jamaica’s Oracabessa River. Others, too, have tried to locate the mine, but it still has never been found. Does Columbus’s legendary mine actually exist? Ainsley Henriques, Abraham Cohen Henriques’s descendant and the current leader of Jamaica’s Jewish community, is quite skeptical. “The gold is in the story,” he has asserted. (1) However, one can never be too sure.

Despite numerous difficulties, the Jamaican Jewish community continued to thrive after its liberation from Spanish rule. The Jewish population has dwindled to fewer than 200 persons. Still, the aged Sha’are Shalom synagogue continues to function in Kingston, near the southern coast. An Israeli-born caterer named Vered Maoz runs a kosher food business in Kingston, as well. (2) In addition, Chabad has recently established a presence in Montego Bay, at the island’s north side, to provide visitors with opportunities to engage in Jewish practice. (3) Ainsley Henriques hosts Jewish history conferences, and opened a museum near Sha’re Shalom. Henriques aims to inform the public about Jamaica’s once-flourishing Jewish life. (4)

Pirate combat, a lost gold mine, stunning scenery, and a rich history spanning more than five centuries: Jamaica remains a fascinating locale, still ripe for new discovery…and adventure novels. Stay tuned!

References:

Kritzler, Edward, Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean. New York: Random House (2008).http://www.aish.com/jw/s/Jews-of-Jamaica.htmlhttp://www.jewishjamaica.com/general-info/http://www.haaretz.com/jewish/features/1.647047

Published on May 07, 2017 13:31

December 25, 2016

A Lesson from the Chanukah Villain

The name “Antiochus” has been known throughout the ages to Jewish children around the world. It’s the name of one of the chief villains of Jewish history, the Seleucid Greek tyrant whom the Maccabees defeated in the story of Chanukah. Relatively recent excavations in Israel have verified traditional accounts regarding this interesting historical character from the Hellenic era and his military and political strategies. Discoveries at the site of Antiochus’s military stronghold in Jerusalem can help us to appreciate the sheer magnitude of the Chanukah miracles.

A descendant of Greek rulers including Alexander IV of Macedon and Seleucus I Nicator, Antiochus IV Epiphanes ruled the Land of Israel with an iron fist. In contrast to his father and predecessor, Antiochus III, who had treated the Jews of Israel in a benign manner, Antiochus IV forbade the study of the Torah and many additional aspects of traditional Jewish life. Recent excavations have uncovered a veritable treasure trove of knowledge regarding Antiochus and his citadel. While the Jewish rebellion that began in the year 168 BCE under Judah Maccabee, and the Maccabees’ miraculous triumph, tell an inspiring story, Antiochus’s military stronghold provides a fascinating tale in its own right.

Antiochus IV erected a fortress known as the Acra, and used it during his siege of Jerusalem. This fortress, mentioned both in the Book of Maccabees and by the historian Flavius Josephus, eventually fell to Shimon Maccabee, Judah’s brother. The fortress’s location allowed the Acra to control all approaches to the Temple. It also cut off the Temple from southern Jerusalem. Antiochus’s strategic placement of the Acra is consistent with what we know to be the Selucid Greek’s broader goal: the imposition of Hellenistic culture to replace Judaism. Antiochus IV’s efforts at Hellenization included the placement of Greek pagan idols in the Temple itself and the abolition of Temple sacrifices. He also banned three specific practices that undergird the Jewish worldview: the Sabbath, the weekly Jewish day of rest; the celebration of the Jewish New Month; and circumcision.

Ruins of the Acra were excavated in November 2015, after over a century of searches by archaeologists. Evidence of the fortress’s existence included “…a section of a massive wall, a tower of impressive dimensions (width about 12 ft, length 60 ft, estimated height 54 ft.) and a slanted slope which was built next to the wall, a defensive element made of layers of earth, stone and stucco, designed to keep attackers from the base of the wall. The slope came down to the Tyropoeon ravine that split the city in ancient times, which was an additional obstacle in defending the fort.” (1)

At the site, archaeologists found numerous weapons, including ballista stones imprinted with pitchforks (Antiochus’s symbol), bronze arrowheads, a catapult, and lead sling stones. A cache of coins dated between the reigns of Antiochus IV and Antiochus VII was uncovered there, as well. According to researchers involved, the coins and “…the large number of wine jars (amphorae) that were imported form the Aegean region to Jerusalem and were found at the site bear witness to the citadel’s age, as well as to the non-Jewish identity of its inhabitants.” (2)

What lessons can we take from the unearthing of the Chanukah villain’s ancient stronghold? Perhaps this discovery can fortify our faith in the enduring nature of the Jewish People. Antiochus and his ilk had it all: wealth, power, and the most advanced weaponry that the old world had to offer. Yet, they did not realize that their society was indeed ancient, and that the very people whom they struggled to subjugate would, one day, be found picking through their artifacts. More importantly, the Jewish People would still be living by their timeless Torah long after the demise of the mighty Greek Empire. Despite the Greeks’ seemingly indomitable military and cultural machine, they were brought down by a fiercely dedicated band of Jews who resisted Greek influence with all of the strength that they could muster.

Our continued survival is the greatest miracle that G-d has ever performed for the Jewish People. We will continue to thrive and to reach heavenward, come what may, like the burning wicks that we kindle nightly at this very special time of year.

Sources:

1. "Ancient Mystery Solved: Hellenistic Citadel that Restricted Jewish Rule in Hasmonean Jerusalem", The Jewish Press. http://www.jewishpress.com/news/israe...

2. "The History and Archaeology of Chanukah," Jewish Home LA. https://jewishhomela.com/2015/12/09/t...

A descendant of Greek rulers including Alexander IV of Macedon and Seleucus I Nicator, Antiochus IV Epiphanes ruled the Land of Israel with an iron fist. In contrast to his father and predecessor, Antiochus III, who had treated the Jews of Israel in a benign manner, Antiochus IV forbade the study of the Torah and many additional aspects of traditional Jewish life. Recent excavations have uncovered a veritable treasure trove of knowledge regarding Antiochus and his citadel. While the Jewish rebellion that began in the year 168 BCE under Judah Maccabee, and the Maccabees’ miraculous triumph, tell an inspiring story, Antiochus’s military stronghold provides a fascinating tale in its own right.

Antiochus IV erected a fortress known as the Acra, and used it during his siege of Jerusalem. This fortress, mentioned both in the Book of Maccabees and by the historian Flavius Josephus, eventually fell to Shimon Maccabee, Judah’s brother. The fortress’s location allowed the Acra to control all approaches to the Temple. It also cut off the Temple from southern Jerusalem. Antiochus’s strategic placement of the Acra is consistent with what we know to be the Selucid Greek’s broader goal: the imposition of Hellenistic culture to replace Judaism. Antiochus IV’s efforts at Hellenization included the placement of Greek pagan idols in the Temple itself and the abolition of Temple sacrifices. He also banned three specific practices that undergird the Jewish worldview: the Sabbath, the weekly Jewish day of rest; the celebration of the Jewish New Month; and circumcision.

Ruins of the Acra were excavated in November 2015, after over a century of searches by archaeologists. Evidence of the fortress’s existence included “…a section of a massive wall, a tower of impressive dimensions (width about 12 ft, length 60 ft, estimated height 54 ft.) and a slanted slope which was built next to the wall, a defensive element made of layers of earth, stone and stucco, designed to keep attackers from the base of the wall. The slope came down to the Tyropoeon ravine that split the city in ancient times, which was an additional obstacle in defending the fort.” (1)

At the site, archaeologists found numerous weapons, including ballista stones imprinted with pitchforks (Antiochus’s symbol), bronze arrowheads, a catapult, and lead sling stones. A cache of coins dated between the reigns of Antiochus IV and Antiochus VII was uncovered there, as well. According to researchers involved, the coins and “…the large number of wine jars (amphorae) that were imported form the Aegean region to Jerusalem and were found at the site bear witness to the citadel’s age, as well as to the non-Jewish identity of its inhabitants.” (2)

What lessons can we take from the unearthing of the Chanukah villain’s ancient stronghold? Perhaps this discovery can fortify our faith in the enduring nature of the Jewish People. Antiochus and his ilk had it all: wealth, power, and the most advanced weaponry that the old world had to offer. Yet, they did not realize that their society was indeed ancient, and that the very people whom they struggled to subjugate would, one day, be found picking through their artifacts. More importantly, the Jewish People would still be living by their timeless Torah long after the demise of the mighty Greek Empire. Despite the Greeks’ seemingly indomitable military and cultural machine, they were brought down by a fiercely dedicated band of Jews who resisted Greek influence with all of the strength that they could muster.

Our continued survival is the greatest miracle that G-d has ever performed for the Jewish People. We will continue to thrive and to reach heavenward, come what may, like the burning wicks that we kindle nightly at this very special time of year.

Sources:

1. "Ancient Mystery Solved: Hellenistic Citadel that Restricted Jewish Rule in Hasmonean Jerusalem", The Jewish Press. http://www.jewishpress.com/news/israe...

2. "The History and Archaeology of Chanukah," Jewish Home LA. https://jewishhomela.com/2015/12/09/t...

Published on December 25, 2016 06:40

February 21, 2016

I Will Always Remember Mama

I stood in our synagogue’s social hall on a typical Saturday night, while my sons and I began listening to Havdalah, the Separation service that officially marks the weekly transition from the Jewish Sabbath to weekday activity. As usual, I was not planning on fulfilling the mitzvah (commandment) of Havdalah by listening to its recitation by others; rather, I expected to go home in order to perform the service for my wife, my daughter and myself. My teenaged son decided to walk home alone from the synagogue before Havdalah was over. I bid him farewell, and he left. A moment later, he surprised me by returning to the room.

“Mommy’s outside, waiting to pick us up,” he told me, “and she’s in a hurry.”

That didn’t sound good. It was a ten-to-fifteen-minute walk home, and there was usually no need to pick us up from the synagogue at the conclusion of the Sabbath. The last time such a thing had happened, Havdalah was followed by a rushed drive to the ICU to visit my ailing mother, Simha Wyckoff. What in the world was going on tonight?

I nervously gathered my five sons and led them outside, where my wife awaited us in our family’s SUV. She was visibly shaken; after quickly urging everyone into the vehicle, she raced down the familiar streets of our neighborhood. On the way home, she answered our curious children’s relentless questions with an uncharacteristic annoyance. Before long, she hastily parked in front of our house and then quickly instructed the children to exit the vehicle. Something was wrong, very wrong.

In our bedroom, with the door locked and no children present, my wife dropped a bomb. “Your mother died last night. I’m sorry.” She then left me alone and allowed my shocked mind to absorb the horror that I had just heard. The four and a half months that my mother’s frail body had spent fighting illness after ruthless illness had finally come to a bitter end. I broke down in tears and then turned on my phone to call my father, stunned by the magnitude of our loss.

As Jews, we are taught not to forsake “Torat imecha,” the “Torah of your mother.” Although fathers are obligated to teach their children the facts and logic that comprise the incredibly vast body of the Written and Oral Torah, the Jewish mother is responsible for creating a home environment that fosters a Torah-true life. The mother provides her children with an indispensable experiential knowledge in her warm and loving Jewish home. In this regard, my mother was – and remains – an unparalleled success. She was my first and best Torah teacher.

In my earliest memories, my mother filled our home with the sights, sounds and scents of a vivid, meaningful and true Jewish life. I called her “Mama.” The smell of her freshly baked challah (bread baked in honor of the Sabbath) and cooked chamin (a Sabbath stew cooked overnight, known in Ashkenazi communities as “cholent”) tantalized me every Friday afternoon and Sabbath day. My mother casually sang songs about Jerusalem and the Kineret as she walked around the house, tending to domestic matters. The lucid images of her lighting the weekly Sabbath candles and of her helping my brothers and me to kindle our Chanukah menorahs every year will always remain with me. She taught me the melodies that I still use for the Friday night Kiddush (Sanctification of the Sabbath Day) and for the Passover Seder. Further, she ignited my yearning for Jewish knowledge by telling a myriad of fascinating stories, including tales from the Tanach (the Jewish Holy Scriptures) and accounts of great individuals from Jewish history. Every year on Passover, she brought the Exodus from Egypt to life. And I will never forget my mother’s anecdotes about the deeds of her righteous parents; although poor, they attended diligently to the needs of people more destitute than they.

A descendant of the Moroccan Jews who had founded the Jewish community of Tiberias in the nineteenth century, my mother was raised in the home of Rabbi Machluf and Rivka Koubbi. She was the youngest of eight children, and grew up with a deep faith in our Creator and an abiding commitment to righteousness and Jewish scholarship. She was born before the outbreak of World War II. As a child, she observed her father standing by the mezuzah (a scroll containing scriptural passages and placed at the doorway of a Jewish home) every morning, tearfully supplicating on behalf of the Jews who were being brutally persecuted and murdered in Europe. After the war, her parents excelled at the Jewish trait of kindness, opening their modest home to numerous Jewish refugees from Europe who had nowhere else to go. A multitude of guests were hosted and treated well in the Koubbi family home every Sabbath and holiday. Her parents perpetually gave charity to the poor, and Machluf studied the Torah without a stop.

My mother made formal Jewish education as important as the experiences that she provided in the home. She excelled at the top institutions in Tiberias and Jerusalem, and later brought her wealth of knowledge and wisdom into the classrooms of Jewish schools in order to teach the next generation. After spending a number of years at schools in Israel and in England, she followed her adventurous spirit to tame the Jewish badlands of the San Fernando Valley. In 1970, she moved to North Hollywood, California, to accept a full-time teaching position at a new Jewish day school, Emek (Valley) Hebrew Academy. The traditionally religious Jewish community in the Valley was quite small in those days, and Jewish education was a difficult challenge for many parents. My mother was instrumental in bringing Torah knowledge to children who otherwise would have had no opportunities to learn their people’s traditions. Not long after moving to the Valley, she met and married my father. Emek was my first school, and will always occupy a special place in my heart.

Financial struggles made it difficult for my parents to provide a continuous religious Jewish education for my brothers and me. With a heavy heart, and feeling forced by unbearable financial pressures, my mother withdrew us from Jewish day school. I finished my elementary school education in a public school setting, and attended public middle and high schools. After-school religious educational programs were available, but they were poor substitutes for day school.

Although I did not make many close friends in public school, my mother saw to it that I survived that experience with a healthy, intact self-esteem. She consistently reassured me that, no matter what came my way, I had worth, lots of worth. I was loved. I mattered. And I had every right to hold my head high; my mother built me up in ways that no other person on Earth could. I felt privileged to have a mother like her (along with an equally loving and devoted father).

My mother’s most prominent, defining characteristic was her inner strength. She was remarkably tough, and had more guts that anyone else I knew. When I was in my late teens, a stationery store that my parents had run jointly for over a decade failed. A couple of real estate investments went poorly, as well, when my parents’ renters simply refused to pay their rent. My mother was hungry for a new challenge, and she chose an intellectual one. She would return to education, this time taking on the task of teaching children with special needs. To do so, she required a degree from the American university system. The first step was to tackle the local community college. She flew through the Associate of Arts program in record time, taking many courses at once. From there, it was on to a California State University, where she quickly completed her B.A. degree and then progressed to a Master’s Degree in Special Education. None of the common excuses and rationalizations stood in her way; she pursued her goals with fierce grit and determination. Whenever she set her mind to something, my mother could be described by only one adjective: unstoppable.

When I was a university student, my interest in learning the Torah, along with traditional Jewish life and practice, was reignited. It was an interest that had, at worst, grown dormant within me, but had never been fully extinguished, over my years of secular education. My mother bragged to friends about my plans to travel to various English-speaking yeshivot (religious schools) in Israel in order to enhance my Torah knowledge. She was elated by each of my decisions to take the observance of a mitzvah more seriously. Throughout the 1990s, I steadily increased my Jewish knowledge and practice, to my mother’s delight. She took great pride in my achievements, reveling in the awareness that Judaism in our family was to continue.

I rarely saw my mother happier than on the day that I announced to her my engagement. Janna was a charming, wise young woman who called my mother “Imma,” the Hebrew word meaning “mother.” After devoting herself tirelessly to raising three sons, my mother was now being rewarded with a daughter. At our wedding, my mother stood by me under a chuppah (Jewish wedding canopy) and cried tears of joy. She could now add a beautiful daughter-in-law to her well-earned arsenal of bragging rights.

An expanded family in Los Angeles meant even more devotion. My mother supported us in every possible way throughout the births of six children, and participated actively in their upbringing. She cooked and baked for us, watched our children, carried them around while speaking to them in Hebrew and singing Hebrew songs for them, and bought them gifts. She prepared massive meals in honor of Jewish holidays, sometimes celebrating them with us and sometimes sending food to our home in order to enhance our celebrations. I will never forget the joy that she expressed at the brit milah (circumcision) of our fifth child, Eliyahu, who was named after her saintly grandfather, the Moroccan-born Torah sage, Rabbi Eliyahu Yiloz.

Ultimately, her family was the only thing that mattered to my mother. Her passing not only ruptured our familial structure itself, but threw our entire dynamic off track. Nearly every month of the year, someone’s birthday was celebrated at her home, with a delicious meal, birthday cake, gifts, and the type of entertainment that only grandparents can provide. The Bat Mitzvah and Bar Mitzvah celebrations of our two eldest children were only the beginning of a long cycle of rewards reaped for my mother’s selfless dedication and her efforts to provide a Jewish home. She loved to attend our younger children’s siddur (prayer-book) parties, our elder children’s graduations, and the annual Purim meals at our house. Imma, you left us too soon.

Against all of my better hopes that I was simply dreaming a horrible nightmare from which I would soon awake, the dreaded day finally arrived. I was scheduled to get on an airplane and fly to Israel, where I would accompany my mother to her final rest in her hometown, the holy city of Tiberias. She would now share a commonality with the Rambam and the Tanna Rabbi Meir. On the morning of my flight, Janna faced the formidable task of consoling a husband who lay in bed, sobbing uncontrollably.

“It’s not goodbye forever,” she said to me, exhibiting her typical sagacity. “Some day, we will be together with Hashem (G-d).”

She was right, of course. The concepts of the eventual Resurrection of the Dead and the World to Come are integral to Jewish belief. As is generally true in Jewish philosophy, these principles have sound rational bases. The human being is a combination of body and soul; although the needs of the soul are primary, the body is also destined to receive its just reward for having enabled the soul to carry out its Divine purpose during a person’s Earthly existence. The eventual reunification of body and soul on Earth will coincide with the Messianic Era, described in our daily prayers with the words, “On that day, G-d will be One, and His Name will be One.” (Zechariah 14:9) Imma, I pray fervently for that day to arrive very soon. I miss you.

“Mommy’s outside, waiting to pick us up,” he told me, “and she’s in a hurry.”

That didn’t sound good. It was a ten-to-fifteen-minute walk home, and there was usually no need to pick us up from the synagogue at the conclusion of the Sabbath. The last time such a thing had happened, Havdalah was followed by a rushed drive to the ICU to visit my ailing mother, Simha Wyckoff. What in the world was going on tonight?

I nervously gathered my five sons and led them outside, where my wife awaited us in our family’s SUV. She was visibly shaken; after quickly urging everyone into the vehicle, she raced down the familiar streets of our neighborhood. On the way home, she answered our curious children’s relentless questions with an uncharacteristic annoyance. Before long, she hastily parked in front of our house and then quickly instructed the children to exit the vehicle. Something was wrong, very wrong.

In our bedroom, with the door locked and no children present, my wife dropped a bomb. “Your mother died last night. I’m sorry.” She then left me alone and allowed my shocked mind to absorb the horror that I had just heard. The four and a half months that my mother’s frail body had spent fighting illness after ruthless illness had finally come to a bitter end. I broke down in tears and then turned on my phone to call my father, stunned by the magnitude of our loss.

As Jews, we are taught not to forsake “Torat imecha,” the “Torah of your mother.” Although fathers are obligated to teach their children the facts and logic that comprise the incredibly vast body of the Written and Oral Torah, the Jewish mother is responsible for creating a home environment that fosters a Torah-true life. The mother provides her children with an indispensable experiential knowledge in her warm and loving Jewish home. In this regard, my mother was – and remains – an unparalleled success. She was my first and best Torah teacher.

In my earliest memories, my mother filled our home with the sights, sounds and scents of a vivid, meaningful and true Jewish life. I called her “Mama.” The smell of her freshly baked challah (bread baked in honor of the Sabbath) and cooked chamin (a Sabbath stew cooked overnight, known in Ashkenazi communities as “cholent”) tantalized me every Friday afternoon and Sabbath day. My mother casually sang songs about Jerusalem and the Kineret as she walked around the house, tending to domestic matters. The lucid images of her lighting the weekly Sabbath candles and of her helping my brothers and me to kindle our Chanukah menorahs every year will always remain with me. She taught me the melodies that I still use for the Friday night Kiddush (Sanctification of the Sabbath Day) and for the Passover Seder. Further, she ignited my yearning for Jewish knowledge by telling a myriad of fascinating stories, including tales from the Tanach (the Jewish Holy Scriptures) and accounts of great individuals from Jewish history. Every year on Passover, she brought the Exodus from Egypt to life. And I will never forget my mother’s anecdotes about the deeds of her righteous parents; although poor, they attended diligently to the needs of people more destitute than they.

A descendant of the Moroccan Jews who had founded the Jewish community of Tiberias in the nineteenth century, my mother was raised in the home of Rabbi Machluf and Rivka Koubbi. She was the youngest of eight children, and grew up with a deep faith in our Creator and an abiding commitment to righteousness and Jewish scholarship. She was born before the outbreak of World War II. As a child, she observed her father standing by the mezuzah (a scroll containing scriptural passages and placed at the doorway of a Jewish home) every morning, tearfully supplicating on behalf of the Jews who were being brutally persecuted and murdered in Europe. After the war, her parents excelled at the Jewish trait of kindness, opening their modest home to numerous Jewish refugees from Europe who had nowhere else to go. A multitude of guests were hosted and treated well in the Koubbi family home every Sabbath and holiday. Her parents perpetually gave charity to the poor, and Machluf studied the Torah without a stop.

My mother made formal Jewish education as important as the experiences that she provided in the home. She excelled at the top institutions in Tiberias and Jerusalem, and later brought her wealth of knowledge and wisdom into the classrooms of Jewish schools in order to teach the next generation. After spending a number of years at schools in Israel and in England, she followed her adventurous spirit to tame the Jewish badlands of the San Fernando Valley. In 1970, she moved to North Hollywood, California, to accept a full-time teaching position at a new Jewish day school, Emek (Valley) Hebrew Academy. The traditionally religious Jewish community in the Valley was quite small in those days, and Jewish education was a difficult challenge for many parents. My mother was instrumental in bringing Torah knowledge to children who otherwise would have had no opportunities to learn their people’s traditions. Not long after moving to the Valley, she met and married my father. Emek was my first school, and will always occupy a special place in my heart.

Financial struggles made it difficult for my parents to provide a continuous religious Jewish education for my brothers and me. With a heavy heart, and feeling forced by unbearable financial pressures, my mother withdrew us from Jewish day school. I finished my elementary school education in a public school setting, and attended public middle and high schools. After-school religious educational programs were available, but they were poor substitutes for day school.