Seth Mnookin's Blog

January 1, 2014

A PSA to journalists writing about vaccines: Thimerosal was never used in the MMR vaccine

The shameless and lamentable decision on the part of ABC to hire Jenny McCarthy as one of its co-hosts for the daytime talk show The View has, once again, brought the topic of vaccines and autism into the news. Fortunately, the spineless “on the one hand, on the other hand” reporting that characterized this debate for so many years has, for the most part, been replaced by an almost universal acknowledgment that vaccines are a safe, life-saving public health intervention — and that there is not now and never has been the smallest shred of evidence showing a causal link between any vaccine and autism.

The shameless and lamentable decision on the part of ABC to hire Jenny McCarthy as one of its co-hosts for the daytime talk show The View has, once again, brought the topic of vaccines and autism into the news. Fortunately, the spineless “on the one hand, on the other hand” reporting that characterized this debate for so many years has, for the most part, been replaced by an almost universal acknowledgment that vaccines are a safe, life-saving public health intervention — and that there is not now and never has been the smallest shred of evidence showing a causal link between any vaccine and autism.

As someone who’s been reporting on and writing about this issue for five years, I know how confusing it all can be — and anti-vaccine activists (like McCarthy or RFK Jr.) take advantage of this confusion by moving the goalposts, throwing up smokescreens, and generally doing whatever they can to obfuscate the reality of the situation. (When there aren’t any facts on your side, your only hope is to create enough distractions so that the public forgets what the real issue was in the first place.)

Which is why I get a little nuts when I see well-meaning journalists who are attempting to grapple seriously with the issue make basic mistakes. Take this Los Angeles Times story^ titled “Jenny McCarthy on ‘View’: A new forum for discredited autism theories.” After running through the sorry history of charlatan/opportunist Andrew Wakefield’s efforts to scare people into thinking the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine could cause autism, the author writes (the emphasis, obviously, is mine):

Subsequent efforts to replicate Wakefield’s findings failed. But vaccination rates began a steep decline anyway, and a new generation of parent activists — skeptics of the biomedical industry’s claim on their children — was born. Meanwhile, the findings spurred additional research, which suggested that the specific culprit in the MMR vaccine was the widely used preservative thimerosol.

I’ll say this as clearly as I can: The MMR vaccine does not and never did contained thimerosal. (This mistake is made so often that the FDA has included it as one of it’s FAQ’s about thimerosal.) It’s a small, niggling point in this larger debate — but when the anti-vaccine movement’s entire tactic is to blur reality, it’s crucially important that those of us dedicated to uncovering and reporting the truth make sure we get every last detail right.

^ July 19: Earlier today, the Times changed the wording in their story and appended a correction which read, “For the Record, 9:08 a.m. PDT, July 19: An earlier version of this online article incorrectly stated that the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine had contained the preservative thimerosal. It did not.” Kudos to them for making the change. I’m not sure why it took them more than 80 hours to do so, but better late than never…

The post A PSA to journalists writing about vaccines: Thimerosal was never used in the MMR vaccine appeared first on The Panic Virus.

December 17, 2013

Live, from Harvard Square– it’s the Sabeti Lab!

A little more than a year ago, I wrote a piece for Smithsonian about Pardis Sabeti, a Harvard geneticist who is one of those incredible overachievers that I’d hate if only she wasn’t so damn likable. Over the past decade, she’s devised robust computational analyses that have resulted in creative new ways to study evolution. She’s also an MD, and much of her recent work has focused on acute viral hemorrhagic fevers. And on top of all that, her post-docs and grad students regularly cite her as one of the most generous and caring mentors they’ve ever had.

Sabeti told me that one of the keys to getting good work out of a team is to make sure everyone is having fun — and one of the ways she does that is with her annual holiday cards. (Last year’s was an homage Psy’s ubiquitous “Gangum Style” video.) The latest entry in this six-year-old tradition features Sabeti and her lab mates acting out classic SNL skits. (They even managed to snag Seth Meyers and Chris Martin for guest appearances.) Here’s Pardis as a Conehead:

There’s plenty more where that came from. (Delicious Dish? Check. Wayne’s World? Check. Dick in a Box? Check and check.) This three-minute video clip has some behind-the-scenes action; the full card is below. Happy holidays, folks!

December 3, 2013

Katie Couric promotes dangerous fear mongering with show on the HPV vaccine.

Tomorrow on Katie: Tiger blood – the new cure-all?

On July 10, 2012, I received an email from a producer at Katie, Katie Couric’s daytime talk show, about a show the program was planning on vaccines. Here was the pitch:

I am interested in talking to Seth Mnookin about his book ‘The Panic Virus.’ I am researching a story about parents who opt out of immunizations for their children because of their personal beliefs. As Seth knows, parents’ fears have lead to a resurgence of diseases like measles and Pertussis and it poses a real danger to society. The goal of the hour will be to better inform the public that still questions links between vaccination and autism and need to better understand the scientific truth.

Over a period of about a month, the producer and I spoke for a period of several hours before she told me that the show was no longer interesting in hearing from me on air. Still, I came away from the interaction somewhat heartened: The producer seemed to have a true grasp of the dangers of declining vaccination rates and she stressed repeatedly that her co-workers, including Couric herself, did not view this as an “on the one hand, on the other hand” issue but one in which facts and evidence clearly lined up on one side — the side that overwhelmingly supports the importance and efficacy of vaccines.

Apparently, that was all a load of crap. Here’s the teaser for tomorrow’s show on the HPV vaccine:

The HPV vaccine is considered a life-saving cancer preventer … but is it a potentially deadly dose for girls? Meet a mom who claims her daughter died after getting the HPV vaccine, and hear all sides of the HPV vaccine controversy.

As I assume Couric and her staff know — they are, after all, literate — here are “all sides” of the HPV vaccine issue:

* More than 25,000 new cancers attributable to HPV occur in the United States each year. Almost 12,000 of these cases are cervical cancer in females; another 6,000 are oropharyngeal cancers in men.

* More than 100 million doses of the vaccine have been given since it was approved in 2006.

* A study published in the British Medical Journal in October evaluated 997,000 girls, 296,000 of whom had received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine. More than 150,000 of those girls received all three doses. The results? Absolutely no link to short- or long-term health problems. As Lisen Arnheim-Dahlström, the lead researcher on the study, told Reuters Health, “There were not really any concerns before our study and no new ones after.”

But hey, you know, what’s years of data based on hundreds of thousands of verifiable results when you have a single “mom who claims her daughter died after getting the HPV vaccine,” right Katie?

November 13, 2013

This Thursday at MIT: ChartGirl in all of her glorious awesomeness

This Thursday, Hilary Sargent, aka ChartGirl, will be giving a talk from 5pm-7pm at MIT in room 4-231 titled “Visualizing Information: An Alternative Route to Understanding and Explaining Complicated Information.”

I can’t speak highly enough of Hilary. She’s had a fascinating career — worked for traditional media (including The Boston Globe, among other places) before embarking on a career of private investigating/corporate intelligence (no joke). On the side, her frustration with the poor way visual information is conveyed in the media led her to start ChartGirl, a one-woman operation that Time recently named one of the 50 Best Websites in the world.

I can’t speak highly enough of Hilary. She’s had a fascinating career — worked for traditional media (including The Boston Globe, among other places) before embarking on a career of private investigating/corporate intelligence (no joke). On the side, her frustration with the poor way visual information is conveyed in the media led her to start ChartGirl, a one-woman operation that Time recently named one of the 50 Best Websites in the world.

You should dive into her site on your own, but here are a small handful of recent examples of her work: “Where in the world is Satoshi Nakamoto?,” ”Taylor Swift, Maneater,” Westboro Baptist Church, aka The Worst Family Ever,” and “Guys! Stop Pissing Off Alec Baldwin!”

Details of the talk, which is part of MIT’s Comparative Media Studies/Writing Colloquium Series, are here. I’ll be doing the moderating, and if you’re in the area, I’d love to see you there.

October 16, 2013

Misogyny and sexism in SciComm, pt 2: Act inappropriately and suffer the consequences. Full stop.

Yesterday, I tried to publicly process my feelings about an incident in which Scientific American blog editor and ScienceOnline co-founder Bora Zivkovic acknowledged acting inappropriately^ toward a young writer named Monica Byrne.

Over the past twenty-four hours, I’ve had many conversations and spent many hours thinking about the information that’s come out as a result of all of this. I’m not sure if I’d even know how to get into all of that here, but I’ve been left with the following conclusion: If we, as a community, are to acknowledge that sexual harassment is both pervasive (and literally every single woman I’ve spoken with has confirmed that it is) and wrong, we are obligated to find ways to address this — not in the abstract and not in the future, but now.

One obvious step is to insist that there be consequences for people who engage in inappropriate behavior regardless of whether they were aware that their behavior made someone uncomfortable at the time. We can’t say, on the one hand, that we want to be a community where women are treated equitably and fairly and then on the other hand say that those among us who do not treat women equitably and fairly get a one-time free pass. Inappropriate behavior often occurs under murky circumstances, and women are right to assume that promises of raised awareness and different standards in the future too often translates as a quick return to business as usual. There has to be a line in the sand. This is wrong. Do it and you will be punished.

Even after reaching this conclusion, I still struggled with the appropriate consequences for Bora. At least until this afternoon.

***

Earlier today, Hannah Waters, a Scientific American blogger who also runs Smithsonian‘s ocean portal, posted a vividly disturbing and searingly honest account of her uncomfortable interactions with Bora over the years. I’m unspeakably grateful she shared what I can only imagine was an excruciating story to tell:

What makes this so hard to talk about—my experience and Monica’s—is that it may not look like sexual harassment. There was no actual sex or inappropriate touching. Bora wasn’t vulgar toward me, nor did he even directly announce his interest. It was all reading between the lines, which made it easy for me to discount my own experience. Instead, I did my best to ignore my discomfort to avoid conflict, or otherwise convinced myself that I was reading too far into it. How vain! To imagine all men want to have sex with me!

…

I’ve made it far enough now that I know my work is valuable on its own. And I’m writing today to let anyone else who has experienced sexual harassment—especially the type of harassment that can be mistaken for acceptable behavior—that you aren’t alone. Whoever did this to you is the one in the wrong. They are the one who did not examine their own power and the effect their “harmless flirting” could have on you.

It’s easy to say that now but, at my most insecure moments, I still come back to this: have I made it this far, not based on my work and worth, but on my value as a sexual object? When am I going to be found out?

I don’t think Bora intended to make me feel this way. In fact, if he knew I were carrying this with me, I’m sure he’d be horrified. But it’s our actions that matter, not our intentions. He did make me feel that way. His actions degraded my self-worth.

That’s a horrible experience for anyone to go through, and it embarrasses me that I’ve been clueless about the extent to which my colleagues and co-workers have dealt with painfully similar situations and emotions. I’m still struggling with the best and most appropriate ways to translate what I’ve learned into concrete actions.

There is one action that can occur immediately. Bora can leave SciAm and his leadership role at SciO. Bora has done a lot for the science communication community over the years, and he’s had an enormous positive impact on many young writers’ lives — and for that, I’ll be forever thankful. He’s also made smart and talented young women question their abilities and their worth — and that is unforgivable.

* Update, 4:22 pm: As I hit publish on this post, I saw that Bora voluntarily resigned from the ScienceOnline Board of Directors; his future involvement with the organization is under review. The full statement from Anton Zuiker, Karyn Traphagen, and Scott Rosenberg is here.

^ Update, 5:04 pm: In the first iteration of this post, this passage read “acknowledged sexually harassing.”

October 15, 2013

A chance to discuss sexism & misogyny in science communication: DNLee, Bora, & the SciAm fiasco

If you’re reading this blog, chances are good that you already know the backstory for this: Last week, an editor at Biology Online asked Danielle N. Lee, a zoology postdoc and well-known blogger, to contribute posts to the site. She asked how much she would be paid — and when he responded that her payment would be in exposure (which, last I checked, doesn’t pay the rent or buy groceries), Lee politely declined. His response to that was to reference the title of her Scientific American blog, Urban Scientist by asking, “Are you an urban scientist or an urban whore?”

On Friday, Lee wrote about the experience; within an hour, her post was removed from Scientific American without any explanation. A firestorm, fueled mostly by the patently false justification tweeted by Scientific American editor Mariette DiChristina.

Many people, including me, were outraged by this; I tweeted about it a handful of times during a chaotic and busy Saturday with my kids. By Sunday night, SciAm Blogs had republished Lee’s original post, DiChristina had publicly explained what had happened, and the offending Biology-Online editor, who still has not been identified publicly, was fired.

Then, at some point yesterday, writer and playwright Monica Byrne updated a post she had published a year ago detailing a encounter she had with a “prominent science editor and blogger.” You can read Monica’s detailed description of the encounter; the CliffsNotes version is: The editor friended Monica on Facebook; Monica sent him clips and asked him to coffee; in the course of discussing her clips, Monica mentioned visiting a strip club; using that as a jumping off point, the editor began talking about his marriage, his sexuality, and his sex life in ways that were clearly inappropriate. Monica later confronted the editor over email; several weeks later, he wrote her an apology and acknowledged he had behaved inappropriately.

Monica’s update contained one new piece of information: The editor and blogger was Bora Zivkovic, who runs SciAm’s blog network and is probably the best-known and most influential person in the science-blogging world. Today, Bora acknowledged that Monica’s description of the events was accurate and that his behavior was wrong – and also that his superiors at SciAm had gotten involved.

Monica writes very eloquently about the ways in which her encounter with Bora affected her. I’m grateful to her for sharing this: As a white man living in the United States in the twenty-first century, I have no idea what it’s like to be bombarded with loutish behavior and unwanted advances on an ongoing basis. Several years ago, a female friend told me about being groped on the subway. I was shocked, a fact which she found laughable: She couldn’t believe that I had no idea that every single woman living in New York had to navigate those waters every single day. By bringing light to one of the often-undiscussed realities of being a woman, Monica has made it that much harder for men to be clueless about what’s going on in the future. Speaking as the father of a daughter and as a teacher, I’m grateful she’s deepened my understanding about the insidious harassment women face.

That does not mean that Bora’s outing was not painful and confusing to me. Bora has been a friend to me and a supporter of mine. I’ve always seen him as someone who was a champion for increasing the diversity of voices in science and science communication. So I didn’t say anything about it — I didn’t tweet about it, didn’t bring attention to it on Facebook or Google+ or LinkedIn.

But my not joining in the discussion on social media obviously does not mean I haven’t been thinking about the situation. As I said above, on a global level, I’m glad Monica came forward. On an individual level, I’m struggling with the correct context through which to view his behavior. Viewed in the context of an increasingly visible attitude towards women on the part of some people whom I’d consider intellectual allies, and then in the immediate context of what happened to Lee, this is horrendous — another piece of evidence that women deal with outrageous types of discrimination and harassment that men can barely imagine.

But is that the right context? Bora has, as many have noted, done an enormous amount to increase the voices of women in science. So do I view his behavior of someone who has internalized the power imbalance and misogyny of much of the scientific and science communication worlds? Or do I view it as the fumbling, bumbling, and clearly inappropriate behavior of someone in the midst of what he has said was a difficult personal crisis?

Obviously, I don’t know all the facts here; obviously, we all may learn more in the next few days; obviously, my judgment may be affected by my personal feelings about Bora and his family. That said, to me, this certainly seems like the latter — and for that reason, it saddens me that Bora was outed at this particular moment. Based on what I know right now, I don’t think the implied rationale–that Bora is another example of the type of sexism that allowed a Biology-Online editor to casually call Lee an “urban whore” when she refused to write for him for free–is correct.

At the moment, that is all a bit beside the point. And hopefully, the events of the past four days will force a conversation about many of these issues into the open — and that is inarguably a good thing. Women are overrepresented among the ranks of those starting out in the field — here at MIT’s Graduate Program in Science Writing, it’s not unusual for between 75 and 85% of our applicants and admittees to be female — but men remain overrepresented in positions of authority. We, as a community, have had years to have this conversation. Let’s not let this opportunity fall by the wayside.

July 16, 2013

A PSA to journalists writing about vaccines: Thimerosal was never used in the MMR vaccine

The shameless and lamentable decision on the part of ABC to hire Jenny McCarthy as one of its co-hosts for the daytime talk show The View has, once again, brought the topic of vaccines and autism into the news. Fortunately, the spineless “on the one hand, on the other hand” reporting that characterized this debate for so many years has, for the most part, been replaced by an almost universal acknowledgment that vaccines are a safe, life-saving public health intervention — and that there is not now and never has been the smallest shred of evidence showing a causal link between any vaccine and autism.

As someone who’s been reporting on and writing about this issue for five years, I know how confusing it all can be — and anti-vaccine activists (like McCarthy or RFK Jr.) take advantage of this confusion by moving the goalposts, throwing up smokescreens, and generally doing whatever they can to obfuscate the reality of the situation. (When there aren’t any facts on your side, your only hope is to create enough distractions so that the public forgets what the real issue was in the first place.)

Which is why I get a little nuts when I see well-meaning journalists who are attempting to grapple seriously with the issue make basic mistakes. Take this Los Angeles Times story titled “Jenny McCarthy on ‘View’: A new forum for discredited autism theories.” After running through the sorry history of charlatan/opportunist Andrew Wakefield’s efforts to scare people into thinking the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine could cause autism, the author writes (the emphasis, obviously, is mine):

Subsequent efforts to replicate Wakefield’s findings failed. But vaccination rates began a steep decline anyway, and a new generation of parent activists — skeptics of the biomedical industry’s claim on their children — was born. Meanwhile, the findings spurred additional research, which suggested that the specific culprit in the MMR vaccine was the widely used preservative thimerosol.

I’ll say this as clearly as I can: The MMR vaccine does not and never did contained thimerosal. (This mistake is made so often that the FDA has included it as one of it’s FAQ’s about thimerosal.) It’s a small, niggling point in this larger debate — but when the anti-vaccine movement’s entire tactic is to blur reality, it’s crucially important that those of us dedicated to uncovering and reporting the truth make sure we get every last detail right.

July 15, 2013

A Jenny McCarthy reader, Pt. 4: The real dangers in following Jenny’s advice

Note: Earlier today, Jenny McCarthy was officially named as a new co-host of the popular daytime talk show The View . As many people have already noted, this is an extremely unfortunate move on ABC’s part: It’s giving the network’s imprimatur to someone who has worked, methodically and relentlessly, to undermine public health.

In (dis)honor of McCarthy’s new perch, I’ve decided to post a chapter of my book The Panic Virus titled “Jenny McCarthy’s Mommy Instinct” on the blog. Since it’s well over 5,000 words, I broke it up; this part final installment is about the dangers in following McCarthy’s advice. You can go back and read Part 1 (“ The birth of a star and an embrace of ‘Crystal Children“), Part 2 (“ Jenny brings her anti-vaccine views to Oprah,” and Part 3 ( “Jenny legitimizes the scientific fringe“).

James Laidler, a medical doctor who teaches in the biology department at Portland State University, has firsthand experience with the lure of this approach. About a year after his oldest son was diagnosed with autism, Laidler’s wife returned home from an autism conference flush with stories about how seemingly intractable cases of the disease had been “cured.” While initially skeptical, Laidler agreed there was no harm in seeing if their son responded to some of the vitamins and supplements that had been recommended. Soon after that, the couple removed gluten and casein from their son’s diet. The next thing they tried was hormone therapy. “Some of it worked—for a while—and that just spurred us to try the next therapy on the horizon,” Laidler wrote in an essay about his experiences. When the Laidlers’ second son started showing autistic-like symptoms, they decided to treat him as well. It was around this time that Laidler went with his wife to an autism conference and saw firsthand what had so impressed her. “[I] was dazzled and amazed,” he wrote. “There were more treatments for autism than I could ever hope to try on my son, and every one of them had passionate promoters claiming that it had cured at least one autistic child.”

This was how the family found themselves headed to Disneyland with forty pounds of preapproved food for their two boys, “lest a molecule of gluten or casein catapult them back to where we had begun.” That’s exactly what they were convinced would happen when, during an unobserved moment, their younger son ate a waffle he’d snatched off a table. “We watched with horror and awaited the dramatic deterioration of his condition that the ‘experts’ told us would inevitably occur,” Laidler wrote. “The results were astounding—absolutely nothing happened.” Over the next several months, the Laidlers stopped every treatment except for occupational and speech therapy. Not only did their sons not deteriorate; they “continued to improve at the same rate as before—or faster. Our bank balance improved, and the circles under our eyes started to fade.” During those years in which he and his wife had been religious devotees of various biomedical treatments, Laidler wrote, they’d just been “chasing our tails, increasing this and decreasing that in response to every change in his behavior—and all the while his ups and downs had just been random fluctuation.”

In some ways, the Laidlers were lucky: The cost of trying every new treatment that comes along can be more than time, money, and dashed hopes, a fact that is tragically illustrated by chelation, the favored cure for ridding the body of “environmental” toxins. A large part of chelation’s appeal among parents lies with the way it tackles the putative problem head-on: It results in the literal expulsion— or “excretion,” to use the phrase favored by its proponents—of the hypothesized poisons from autistic children’s bodies. Unfortunately, as can be expected from a chemical cleansing process originally designed during World War I as a treatment for mustard gas exposure, chelation comes with a significant amount of risk. When Liz Birt’s son, Matthew, was chelated, his condition seemed to worsen, and in one instance, chelation preceded a grand mal seizure. Colten Snyder, whose family’s suit claiming the MMR vaccine had caused his autism was one of the Vaccine Court’s initial Omnibus Autism Proceeding test cases, had an even worse experience: After his second round of chelation, a nurse wrote in his medical records that he went “berserk.” He also became aggressive and noncompliant, became more prone to tantrums, and exhibited increased repetitive behaviors. After his third round of treatment, he was brought to a medical facility due to severe back pain, which is one of the procedure’s known side effects.

Then there’s the case of Abubakar Nadama, who moved with his mother to Pennsylvania from Batheaston, England, because chelation is not permitted for the treatment of neurodevelopmental disorders in the U.K. On August 23, 2005, Abubakar went into massive cardiac arrest and died while receiving intravenous chelation therapy from a sixty-eight-year-old ear, nose, and throat specialist named Roy Kerry. In a 2009 lecture titled “Starting the Biomedical Treatment Journey,” Lisa Ackerman told parents they couldn’t let Abubakar’s death dissuade them. “I’m going to not be politically correct again,” she said. “There’s a child that passed away from chelation and it was extraordinarily sad and tragic. . . . The guy that gave the chelator to that little boy gave the wrong dose and the wrong type, and the kid had a heart attack because the doctor erred.”

Lisa Ackerman and Jenny McCarthy

That didn’t mean, Ackerman said, that parents should be “afraid”; after all, they were going to need to “step it up” if they wanted their kids to get better. Ackerman failed to mention that less than a year after his patient died, “the guy that gave the chelator” was recognized as a DAN!–approved clinician, a designation which is obtained by attending a thirteen-hour seminar conducted by the Autism Research Institute, signing a loyalty oath to the organization’s principles, and paying an annual fee of $250. (In order to maintain certification, doctors must attend a continuing education seminar every two years.)

Another of Ackerman’s recommendations that morning was to buy some of the “thousands” of supplements marketed to parents of autistic children. Her personal favorites were those produced by a company called Kirkman Labs. “Go get their handy-dandy resource guide called ‘The Roadmap.’ That will tell you what supplements do what,” she said. “I’m a big fan of Kirkman’s because they’ve been around forever and their products are tried and true.” Less than nine months later, Kirkman did a voluntary recall of seven of their products because they contained high levels of antimony, a chemical element used in flameproofing, enamels, and electronics—and one that some anti-vaccine activists had recently been proposing as a potential cause of autism.

A Jenny McCarthy reader, Pt. 3: Jenny legitimizes the scientific fringe

Note: Earlier today, Jenny McCarthy was officially named as a new co-host of the popular daytime talk show The View . As many people have already noted, this is an extremely unfortunate move on ABC’s part: It’s giving the network’s imprimatur to someone who has worked, methodically and relentlessly, to undermine public health.

In (dis)honor of McCarthy’s new perch, I’ve decided to post a chapter of my book The Panic Virus titled “Jenny McCarthy’s Mommy Instinct” on the blog. Since it’s well over 5,000 words, I broke it up; this part (the third of four) is about McCarthy’s efforts to legitimize the scientific fringe. Part 1 was about the McCarthy’s rise to fame and her embrace of the “Crystal Children” philosophy, Part 2 details McCarthy’s use of Oprah Winfrey’s megaphone, and the final installment is about the danger of following Jenny’s advice.

McCarthy’s sudden ubiquity did more than give families affected by autism hope for a miracle cure—it also further legitimized a movement that still had not completely shed its reputation as being on the scientific fringe. Dan Olmsted, a former UPI reporter who is one of the editors of the Age of Autism blog, gives McCarthy credit for singlehandedly pushing vaccine skeptics into the mainstream: “To anybody who comes to this issue from the environmental and recovery side of this debate—the idea that something happened to these kids, and it’s probably a toxic exposure—Jenny McCarthy is the biggest thing to happen since the word autism was coined.”

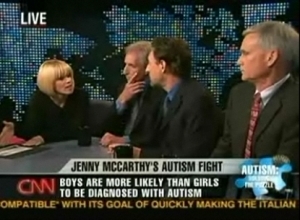

The media’s willingness to indulge McCarthy’s campaign and its disinclination to provide an accurate representation of the issues at stake continued unabated in 2008. On World Autism Awareness Day that April, Larry King devoted his full hour-long broadcast to “Jenny McCarthy’s Autism Fight.”  Also appearing on the show that evening were David Kirby and Jay Gordon, the celebrity pediatrician who’d been treating Evan ever since McCarthy became convinced he’d been harmed by the MMR vaccine. Together, the trio repeatedly shouted down David Tayloe, the president-elect of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Also appearing on the show that evening were David Kirby and Jay Gordon, the celebrity pediatrician who’d been treating Evan ever since McCarthy became convinced he’d been harmed by the MMR vaccine. Together, the trio repeatedly shouted down David Tayloe, the president-elect of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Gordon: David Kirby’s book is entitled Evidence of Harm, okay? The evidence is there. We have to address the evidence. We do not have respect for the instincts of our parents. We don’t have respect for the immune system. The immune system is a complicated, complicated system in the body, complex—

Tayloe: But you need scientific evidence that— gordon: You need to prove it’s safe!

McCarthy: First!

Gordon: Yes!

Kirby: There is a bill in Congress to study vaccinated versus unvaccinated populations in this country. Doctor, would you support that legislation? Would you?

Tayloe: W e support—

Kirby: D o you?

Tayloe: W e are not afraid of the truth at the American Academy of Pediatrics—

McCarthy: Well, will you support the unvaccinated/vaccinated study?

Two months later, McCarthy and Jim Carrey led a “Green Our Vaccines” rally in Washington that also featured Gordon and included a keynote address by Robert Kennedy. (In the TACA press release announcing the rally, Ackerman appeared to confuse Kennedy with his uncle, Massachusetts senator Edward Kennedy: “Having Senator Kennedy as part of the supporters for the Green Our Vaccines Rally is an honor.”) McCarthy’s rally-related appearances on Good Morning America and Fox News’ On the Record with Greta Van Susteren didn’t even feature anyone representing an opposing viewpoint.

By that time, McCarthy’s autism activism had become a full-time job. She’d taken over Generation Rescue, which was rebranded as “Jenny McCarthy and Jim Carrey’s Autism Organization.” (After the couple’s split in the spring of 2010, the Web site was listed either as “Jenny McCarthy’s Generation Rescue” or “Jenny McCarthy’s Autism Organization.”) By the end of the year, she’d published Mother Warriors: A Nation of Parents Healing Autism Against All Odds and signed a deal with the licensing agency Brand Sense to create Too Good by Jenny, a line of non toxic products ranging from bedding to cleaning supplies that “will be positioned as providing safe, non-toxic surroundings for children.” She’d also launched Teach2Talk Academy, a school for autistic children, and developed a series of Teach2Talk DVDs designed to improve autistic children’s “imagination” and “empathy toward others” by having them mimic what they see on screen.

The following spring, just as had been the case the year before, McCarthy was booked as the keynote speaker at the annual Autism- One conference at the Westin O’Hare. A half-hour before she was scheduled to appear, most of the seats in the Westin’s 7,400-squarefoot Grand Ballroom had already been claimed. Twenty minutes later, people were sitting two and three deep along the walls and in the aisles. Before the start of the main event, the restless audience had to sit through a presentation by Sarah Clifford Scheflen, the thirty-one year-old speech pathologist who was the co‑founder of Teach2Talk. (In April 2010, Teach2Talk Academy was closed after McCarthy and Scheflen parted ways due to “different visions for the school.”) Scheflen appreciated that putting autistic children in front of a TV might seem to some to be a counterintuitive way to teach children with developmental disorders how to interact appropriately with actual human beings. “People always ask me, ‘Why, Sarah? Why does it work with the TV and not one-on-one?’ ” she said. “Children tend to be strong visual learners. . . . Sometimes I get distracted when I see two pairs of shoes on the floor, and I think that’s what happens when kids come into my office.” A handful of people in the audience chuckled, although most seemed nonplussed by Scheflen’s comparison. “So I would show the child the prerecorded model and then the child would watch the video and imitate that—because most children learn through imitation.”

Within fifteen minutes of the start of Scheflen’s presentation, murmured conversations had begun to break out throughout the hall. After a series of glitches with the hotel’s AV system, a visibly flustered Scheflen began to peer offstage. “So, um, I think Miss Jenny—is she here?” Indeed she was. Scheflen quickly wrapped up, and when McCarthy stepped out from the wings, the crowd erupted. One woman started hopping up and down like a teenager at a Taylor Swift concert, shouting over and over, “We love you Jenny!”

McCarthy was dressed casually—she had on a pink zip-up sweater and jeans, and her hair was pulled into a tight ponytail—and when she took the stage, she started clapping along with the audience. “How many people are back from last year?” Hundreds of hands shoot up. “I love it! We have an overflow crowd in the other room, so I’ll give a shout out to them.” Then, in lieu of a prepared speech, McCarthy told the audience she’d rather answer questions they had about her journey.

“ ‘Jenny,’ ” she said, reading off a note card, “Will you please repeat the five steps you said last year? That was a huge help to us.’ ” That, McCarthy explained, was a reference to checklist she keeps on her refrigerator. “The first one I call cleaning the bucket. All these kids have a bucket of toxins, infections, funguses,” she said. Before they can treat their children effectively, McCarthy explained, parents needed to properly identify the problem: “PLEASE go and get allergy testing. If you want to know what kind, it’s in my book.” Step two is cleaning out the fungus: “A lot of these kids are malnourished . . . please, please don’t forget about that.” Step three is detoxification, either using chelation or any number of other therapies. “You know, I’ve been getting glutathione IVs every weekend because I’m starting to take care of myself,” she said. (Glutathione is a naturally occuring antioxidant that is depleted in patients with wasting diseases such as sepsis, cancer, and AIDS. There has never been a clinical trial on the effects of glutathione infusions in healthy humans or developmentally disabled children.) “I was a cold sore, herpes monster. . . . I was a mess. I started glutathione and in the last three months I haven’t had a cold sore.”

After acknowledging the irony of her next recommendation, McCarthy explained that step four was drugs. “Even though some of us are so angry at the pharmaceutical companies,” she said, “I’m grateful for the medicine that we do need to get our kids better.” According to McCarthy, antifungals and antivirals were especially important; in fact, she said she knew one child who fully recovered from autism in less than three months as a result of antiviral therapy.

Finally, there was step five: positive thinking. “I love that one more than anything,” McCarthy said, because it demonstrates the power parents have to change their lives. “If you think, ‘My kid is going to get better,’ he’s going to get better. If you keep thinking, ‘My kid is going to be sick,’ he’s going to be sick.” (Presumably, a more detailed explanation of how that process worked was provided at one of the conference’s earlier lectures, which covered a philosophy that involves wishing your way to better health.)

“I’ve come to trust other parents more than anyone during this journey,” McCarthy said. “I salute you all for being here today, and for believing and trusting and working on your child, for spending the money and the time and the tears on autism.” There are so many people, McCarthy said, who don’t come to these conferences, a fact that left her dumbfounded. “It breaks my heart,” she said, when she meets the parents of a child with autism and “they still refuse to do anything.”

What McCarthy seemed to be saying was that it broke her heart when parents refused to do everything: buy books and DVDs; try chelation and hyperbaric chambers; take supplements, make gluten-free meals, and eat organic chickens; march on Washington, write elected officials, and sign petitions; use DAN! doctors, travel across the country for treatment at special clinics, and ignore anyone who suggests otherwise . . . and if none of that works, start all over again.

Besides being expensive and exhausting, one disadvantage of that approach is that it’s impossible to know if any of it actually does any good. An indiscriminate attitude toward treatment also makes it hard to determine what changes are due to the natural rhythms of disease: Temporary ailments by definition get better and the symptoms of lifelong conditions almost always wax and wane, which means that even the most far-fetched cure is bound to look like a winner every now and again. In his book Innumeracy, the mathematician John Allen Paulos describes how proponents of pseudoscientific therapies rely on this reality to shade their products in the best light possible. “To take advantage of the natural ups and downs of any disease (as well as of any placebo effect),” Paulos writes, “it’s best to begin your worthless treatment when the patient is getting worse. In this way, anything that happens can more easily be attributed to your wonderful and probably expensive intervention. If the patient improves, you take credit; if he remains stable, your treatment stopped his downward course. On the other hand, if the patient worsens, the dosage or intensity of the treatment was not great enough; if he dies, he delayed too long in coming to you.”

A Jenny McCarthy Reader, Pt. 2: Jenny brings her anti-vaccine views to Oprah

Note: Earlier today, Jenny McCarthy was officially named as a new co-host of the popular daytime talk show The View . As many people have already noted, this is an extremely unfortunate move on ABC’s part: It’s giving the network’s imprimatur to someone who has worked, methodically and relentlessly, to undermine public health.

In (dis)honor of McCarthy’s new perch, I’ve decided to post a chapter of my book The Panic Virus titled “Jenny McCarthy’s Mommy Instinct” on the blog. Since it’s well over 5,000 words, I broke it up; this part (the second of four) is about Oprah Winfrey’s endorsement of McCarthy’s anti-vaccine views. The first part was about the McCarthy’s rise to fame and her embrace of the “Crystal Children” philosophy; Part 3 is titled “Jenny legitimizes the scientific fringe,” and Part 4 is “The real dangers in following Jenny’s advice.”

In 2005, McCarthy contacted Lisa Ackerman, the mother who’d founded Talk About Curing Autism five years earlier. “Jenny was looking for information to help her son Evan, who was recently diagnosed,” Ackerman wrote in an essay titled “TACA and Jenny McCarthy.” “Jenny is an extraordinary mom. She ran with every bit of information that she gleaned from TACA’s website, individual mentoring and community outreach efforts and was back when she needed more. As Evan improved Jenny kept good on her promise to get involved.” In fact, McCarthy got so involved that she donated a portion of the proceeds from Life Laughs, which was released in April 2006, to the organization.

Shortly thereafter, McCarthy told Ackerman she’d decided to write her next book about autism—and, McCarthy vowed, when it came out she’d publicize it on The Oprah Winfrey Show.The narrative for this latest project would be in stark contrast to the Crystal Child one McCarthy had been promoting on The Tonight Show and in newspaper interviews: Now, McCarthy said, her mistreatment at the hands of Evan’s doctors had begun when she’d tried to discuss with them her concerns about vaccines. The only two constants of McCarthy’s competing story lines were her refusal to let the medical establishment victimize her and her promise of succor to anyone who followed her path. “I say, Okay, let’s look at your choices,” she says of the message she’s currently pitching to the public. “You have a choice of listening to the medical community, which offers no hope, or you can listen to our community, which offers hope. . . . O ur side at least gives you . . . somewhere to go.”

True to her word, on September 18, 2007, one day after Louder than Words: A Mother’s Journey in Healing Autism was released, McCarthy appeared as a guest on Oprah. That afternoon, with Ackerman looking on from the second row of the studio audience, McCarthy told Winfrey that her latest journey had begun with a flash of insight that sounded similarly dramatic to the one that had occurred in 2006 when a stranger told McCarthy that her son was a Crystal Child—except this epiphany had taken place two years earlier, when McCarthy awoke one morning with a terrifying premonition that something was wrong. Shortly thereafter, Evan, who was around two years old at the time, had the first in a series of what McCarthy described as life-threatening seizures. For months, McCarthy said, her requests for help for her child were dismissed by every doctor she approached. (At times, McCarthy said, this condescension would mutate into rage: She claimed that one pediatrician had become so incensed by her insistent questioning that he shouted at her to “leave the hospital— now!”) It wasn’t until Evan suffered a near-fatal heart attack that he was properly diagnosed as autistic—and even then, McCarthy said, she wasn’t offered any help or support. “I got the, ‘Sorry, your son has autism’ [speech],” she told Winfrey. “I didn’t get the here’s-what-todo- next pamphlet.”

Winfrey, who praised Louder than Words as “beautiful” and “riveting,” didn’t ask McCarthy why she hadn’t mentioned the seizures or the screaming doctors or the heart attack during her Indigo phase, when she’d claimed that treating Evan for a behavioral disorder would be akin to “taking away all the beautiful characteristics he came into this world with.” In fact, neither Winfrey—nor, seemingly, anyone else—asked McCarthy about her prior involvement with the Indigo movement at all. Instead, Winfrey praised McCarthy’s unwillingness to bow to authority, her faith in herself, and her use of the Internet as a tool for bypassing society’s traditional gatekeepers:

McCarthy: First thing I did—Google. I put in autism. And I started my research.

Winfrey: Thank God for Google.

McCarthy: I’m telling you. winfrey: Thank God for Google.

McCarthy: The University of Google is where I got my degree from. . . . And I put in autism and something came up that changed my life, that led me on this road to recovery, which said autism—it was in the corner of the screen—is reversible and treatable. And I said, What?! That has to be an ad for a hocus pocus thing, because if autism is reversible and treatable, well, then it would be on Oprah.

The ad McCarthy saw was for a wheat- and dairy-free diet. Within weeks of her putting Evan on this new regimen, McCarthy said, he’d doubled his language, his eye contact improved, he began smiling more, and he became more affectionate. “Once you detox them,” McCarthy said, “your kids are going to get better. You’re cleaning up their gut. You’re cleaning up their brain. There is a connection.”

Winfrey nodded in agreement—but how, she asked, did McCarthy know to try this specific diet as opposed to the “fifty other things” that showed up online?

McCarthy: Mommy instinct.

Winfrey: Mommy instinct.

McCarthy: Mommy instinct. . . . I went, okay—I know my kid. . . . I know what’s going on in his body, so this is what makes sense to me. . . .

Winfrey: Okay—so this is what Jenny says really worked for her. It doesn’t mean it will work for all children. . . . It worked for her. This is her book. She wrote the book. So she knows what she’s talking about.

As it turned out, Mommy instinct had done more than just show McCarthy which of the many alternative “biomedical” treatments she should pursue—it had also given her insight into what had made Evan sick in the first place. Winfrey, in much the manner she’d done with Katie Wright five months earlier, prompted McCarthy to share that information with the audience:

Winfrey: So what do you think triggered the autism? I know you have a theory.

McCarthy: I do have a theory.

Winfrey: Mom instinct.

McCarthy: Mommy instinct. You know, everyone knows the stats, which being one in one hundred and fifty children have autism.

Winfrey: It used to be one in ten thousand.

McCarthy: And, you know, what I have to say is this: What number does it have to be? What number will it take for people just to start listening to what the mothers of children who have autism have been saying for years? Which is that we vaccinated our baby and something happened. . . . Right before his MMR shot, I said to the doctor, I have a very bad feeling about this shot. This is the autism shot, isn’t it? And he said, “No, that is ridiculous. It is a mother’s desperate attempt to blame something on autism.” And he swore at me. . . . And not soon thereafter, I noticed that change in the pictures: Boom! Soul, gone from his eyes.

At that point, Winfrey picked up an index card. “Of course,” she said, “we talked to the Centers for Disease Control and asked them whether or not there is a link between autism and childhood vaccinations. And here’s what they said.” As she started to read, the screen filled with text.

We simply don’t know what causes most cases of autism, but we’re doing everything we can to find out. The vast majority of science to date does not support an association between thimerosal in vaccines and autism. . . . It is important to remember, vaccines protect and save lives.

When Winfrey appeared back on screen, she turned to McCarthy, who was ready with a response: “My science is named Evan, and he’s at home. That’s my science.” There was little question that Winfrey’s sympathies lay with the “mother warrior” who’d written a “beautiful new book” about how she’d cured her son of a supposedly incurable disease as opposed to the faceless bureaucracy that couldn’t provide any answers.

Before the end of the show, Winfrey told viewers that McCarthy would be available to answer questions for anyone who logged on to a “special [online] message board just for this show so you can share your stories.” One fan asked McCarthy what she would do if she could do it all over again. “The universe didn’t mean for me to do anything else besides what I did,” McCarthy answered, “but if I had another child, I would not vaccinate.” A mother wrote in to say that she had decided not to give her child the MMR vaccine “due to the autism link.” McCarthy was delighted. “I’m so proud you followed your mommy instinct,” she wrote.

Within a week of her appearance on Oprah, during which time McCarthy had also broken the news about her relationship with the comedian Jim Carrey, McCarthy had repeated her story on Larry King Live and Good Morning America. On those three shows alone, she reached between fifteen and twenty million viewers—and that wasn’t including people who watched repeats or saw the clips online. Print publications told her story as well: People, which is one of the largest general interest magazines in the country, ran an excerpt from Louder than Words under the headline, “My Autistic Son: A Story of Hope.”  The media blitz’s effects were felt immediately. Ackerman, who’d appointed McCarthy as TACA’s celebrity spokesperson in June, said the group was so swamped with e‑mails from parents pleading for information about how to cure their children that it scrapped its more cautious expansion plans and went national that fall. “Had to,” she said. “Jenny forced us.”

The media blitz’s effects were felt immediately. Ackerman, who’d appointed McCarthy as TACA’s celebrity spokesperson in June, said the group was so swamped with e‑mails from parents pleading for information about how to cure their children that it scrapped its more cautious expansion plans and went national that fall. “Had to,” she said. “Jenny forced us.”

Seth Mnookin's Blog

- Seth Mnookin's profile

- 39 followers