Robert D. Cornwall's Blog

April 25, 2024

Deconstruction, Reconstruction, & Being Called to Bless

We allknow about the slow decline of Mainline Protestantism. Over the years, the once-dominantdenominations have declined significantly in numbers. There are numerous reasonsfor it, but the truth is these traditional denominations, including the one inwhich I’m ordained, have failed to retain their children and draw in newmembers. Many of the children of older Mainliners ended up Evangelicals. Now,we’re seeing a major shift within Christianity, as many evangelicals,especially ones who grew up in it are leaving. Not only are they leavingevangelicalism, but they’re also leaving the Christian faith. There are numerous reasonsfor that, including patriarchy, scandals, politicization (alignment with the Trump-ledRepublican Party), and a rejection of LGBTQ persons. Several books haveappeared exploring these realities. At the moment, I’m finishing reading SarahMcCammon’s Exvangelicals (reviewforthcoming).

I’m aBoomer. I was born and raised an Episcopalian but became part of aPentecostal/Evangelical church in High School. Then I went to a ChristianCollege, served as a youth minister in a conservative church, and then headedoff to seminary (an evangelical seminary). Over time I shed much of theevangelical ethos and became more liberal in my politics and even my theology.One of the key moments for me was being fired from my teaching position at aBible college for being too liberal. A second was the coming out of my brother,which led to my own reappraisal of my beliefs about LGBTQ. What is happeningtoday seems different from what I experienced. It seems more intense, andpeople are simply exiting, though some are seeking to create Postevangelicalcommunities. What that will look like is yet to be determined. I’m a bitconcerned that the current communities are largely white and perhaps male-dominated.They tend to embrace LGBTQ persons, but my concern is that they become justanother silo. But not everyone is staying.

One ofthe current words for what is happening today is “deconstruction.” It is a termthat has been around for a while but wasn’t something we talked about during myperiod of transition/transformation. Regarding deconstruction, I’ve beenreading God After Deconstruction byTom Oord and Tripp Fuller. A review of this book is forthcoming as well. Theyalso describe the processes undertaken by evangelicals, mostly white, who areseeking to extricate themselves from the narrow confines of their evangelicalexperiences. As with those whom Sarah McCammon describes, most of those theyspeak of were born into a white evangelical subculture, such that they werefully enmeshed in this world.

As Iread these books, I realized that my story is different. I wasn’t born into thissubculture, didn’t attend Christian schools, or was homeschooled, and I hadfriendship circles outside the subculture. I bought in, but it appears I wasnot as deeply rooted as some who are now undergoing deconstruction.

As Iread these books and watch the developments on the ground, I wonder how thosewho have been so affected by their past experiences might move beyonddeconstruction to reconstruction. As Tom and Tripp suggest, there may need tobe theological adjustments, though I’m not sure that Process theology is theonly possible path out of the morass. For me, the people who contributed to mytransition included Karl Barth, Hans Küng, Jürgen Moltmann, and DietrichBonhoeffer.

One ofthe questions we face as we begin to put the pieces back together is where wefind meaning and purpose. In my own journey, I discovered that there are piecesfrom the past and present that have helped form me. I call this spiritual DNA.As people deconstruct there is a tendency to toss out everything from the past,but I believe that there are pieces that can be reclaimed. If you are like me,and you have spent time in several traditions, you might have severalstrands of spiritual DNA. How then do we put things back together?

In 2021I published with Cascade Books (Wipf and Stock) a book I titled Called to Bless: Finding Hope by Reclaiming OurSpiritual Roots. In that book I share my own spiritual journey, whatyou might call a theological memoir, reflecting on the elements that haveformed me, as I spent time in Anglicanism, Pentecostalism, Evangelicalism, andthe Disciples/Restoration Movement. As I’ve reflected on the discussions about deconstruction,I believe that my book offers a possible path to reconstruction. The key pieceis the thread that ties everything in the book together, and that is ourcalling as Christians, as spiritual descendants through Jesus of Abraham andSarah, to be a blessing to the nations (Gen. 12:1-4). Here we find a purpose inlife that is deeply rooted in our faith tradition. For me that discovery hasempowered my own engagement with dear friends outside the Christian communityas we each claim our calling to be a blessing.

Withthis in mind, I invite you to pick up my book Called to Bless.From now until the end of May, you can order a copy from Wipf and Stockand receive a 40% discount. Just use the code: CALLEDTOBLESSCORNWALL. You can also getthe book at Amazon and other fineretailers.

PLEASE UPDATE THE RSS FEED

The RSS feed URL you're currently using https://follow.it/bob-cornwall will stop working shortly. Please add /rss at the and of the URL, so that the URL will be https://follow.it/bob-cornwall/rss

April 24, 2024

The True Vine—Lectionary Reflection for Easter 5B (John 15)

Vincent Van Gogh, Vineyards with a View of Auvers

Vincent Van Gogh, Vineyards with a View of Auvers

John 15:1-8 New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition

15 “I am the true vine, and my Father is thevinegrower. 2 He removes every branch in me thatbears no fruit. Every branch that bears fruit he prunes to make it bearmore fruit. 3 You have already beencleansed by the word that I have spoken to you. 4 Abidein me as I abide in you. Just as the branch cannot bear fruit by itself unlessit abides in the vine, neither can you unless you abide in me. 5 Iam the vine; you are the branches. Those who abide in me and I in them bearmuch fruit, because apart from me you can do nothing. 6 Whoeverdoes not abide in me is thrown away like a branch and withers; such branchesare gathered, thrown into the fire, and burned. 7 Ifyou abide in me and my words abide in you, ask for whatever you wish, and itwill be done for you. 8 My Father is glorified bythis, that you bear much fruit and become my disciples.

*******************

Agrapevine has branches. Those branches, which carry the fruit, are connected tothe vine. Without the vine the branches are dead. The vine carries the lifeforce of the plant to the branches, which produce the fruit. Jesus is the vineand we are the branches. As such, through our connection to the vine, weproduce fruit. In both the Gospel of John and 1 John we see references to abidingin and with God, reflecting this image of the vine and branches. It is an imagethat has deep roots in the Old Testament, where Israel is depicted in severalplaces as a vine and branches that God cares for and when necessary prunes.

TheGospel reading for this Fifth Sunday of Easter takes us back to the Gospel ofJohn, and more specifically to Jesus’ final teaching session that follows hislast meal with his followers. The final instructions and his prayer for thedisciples make up chapters 14 through 17. The reading for the Fifth Sunday comesfrom the fifteenth chapter of the Gospel.

Ourreading for the week from John 15 begins with Jesus declaring “I am the truevine, and my Father is the vinegrower.” In this role of vinegrower orvinedresser, the Father prunes the vine so that branches that fail to producefruit are removed. You prune the vine to make it healthier and able to bearmore fruit. As for the identity of the branches, Jesus tells his disciples thathe is the vine and they are the branches. With that imagery in place Jesustells his disciples who have gathered with him for that final meal, that ifthey abide in him, he will abide in them. Just as the branch can’t bear fruitunless it abides in the vine, the same is true for them. Deirdra Good notesthat “Understanding of the images of Jesu as the true vine and disciples asbranches, together with the repetition of ‘remain’ or ‘abide’, is intuitive andmystical. A vine, for example, is not separate but rather indistinguishablefrom its branches, and as the branches in turn may be cut off, their wholeidentity is nevertheless in the vine. Branches are never independent but alwaysrooted and growing in Jesus.” [Connections, p. 260]

Whileit is true that the branch requires the sustenance of the vine to bear fruit,if the branch is not connecting (abiding) with the vine, then it is of novalue. Therefore, it simply withers away until it’s removed and tossed into afire to be burnt up. Thus, this is the way it is for those who fail to abide inJesus. They lose their sustenance and thus their ability to bear fruit. Therefore,they are pruned and tossed into the fire, which consumes them.

WhileJesus mentions the possibility of pruning branches, his expectation for hisdisciples is that they will abide in him and bear fruit. So he tells them thatif they abide in him, and his words in them, they can ask of him whatever they desireand it will be fulfilled so that the Father is glorified. That sounds a bitlike what you might hear from a prosperity gospel preacher. Just name it andclaim it and it’s yours. While it might be used in that way, I don’t thinkthat’s what Jesus has in mind. Rodger Nishioka helpfully writes “Because weabide in him and he abides in us, whatever we ask will be given. This promiseis certain because as we remain in him, we grow more and more into hislikeness. As we grow more and more into his likeness, what we desire will bemore commensurate with what he desires. That is the result of abiding” [Connections,pp. 263-264]. In other words, if we’re abiding in Jesus and our desiresmirror his, we won’t be asking for private jets and mansions.

It's appropriate that this passagehas been chosen for this point in the calendar, at least in the NorthernHemisphere. With the onset of spring, we see the trees and vines begin to leafout, bloom, and when appropriate show signs that fruit is to be expected. Inother words, by viewing nature Jesus’ words are enhanced and affirmed.

Theword here speaks of connections between Jesus and the Father along with he andhis disciples. There is a sense here of mutuality, such that there is a mutualindwelling such that Jesus abides in us and we abide in him. Therefore, weabide in God. The message throughout the “Farewell Discourse” is that Jesusenvisions oneness among his followers. Later in the Discourse, as it comes toan end right before his arrest, he prays for his followers, asking that theywould be one even as he and the Father are one: “I ask not only on behalf ofthese but also on behalf of those who believe in me through theirword, that they may all be one. As you, Father, are in me and I am in you,may they also be in us, so that the world may believe that you have sentme.” (Jn 17:20-21).

John uses several similar metaphorsto describe his relationship with his disciples, as does Paul. The metaphorfrom Paul that I find most helpful is that of the church as the Body of Christ.Together his followers form his body on earth post-resurrection. Theologically,we might turn to the Greek word perichoresis to describe thisrelationship. This Greek word has played an important role in our understandingof Jesus' nature as truly human and truly divine, as well as the internalTrinitarian relationships, such that God is one and yet three. The idea here isthat there is mutual interpenetration within the Godhead, a sense of abiding ineach other, reflecting the unity of the Godhead and the unity of the Body ofChrist. Catherine Mowry LaCugna puts it this way:

He is who and what God is; he iswho and what we are to become. Jesus owes his whole existence, authority,identity, and purpose to God; he ‘originates’ from God, is begotten of God,belongs eternally to the life and existence of God. Through him we, toooriginate from God, are begotten of God, and belong eternally to the life andexistence of God. [God for Us: The Trinity and Christian Life, p.296].

We are one in the Spirit, such that we participate in thelife of God through Jesus who abides in us, even as we abide in him. The goalis that we might bear fruit and express the love that is God.

InJohn’s version of the Gospel story, we hear Jesus describe what it means to behis follower. It is a calling that he extended to the disciples and us. We arebranches, connected to a vine. The expectation is that we will bear fruit(grapes for harvest). In doing so we reflect the presence of Jesus who dwellswithin us. What is the fruit? Perhaps we might want to consult Paul’s list of thefruit of the Spirit in Galatians 5: “The fruit of the Spirit is love, joy,peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness,and self-control. There is no law against such things” (Gal. 5:22-23).

When weabide in Christ, such that he abides in his, we express our dependence, perhapseven interdependence, with Jesus. Our spiritual lives depend on abiding in orparticipating in the life of Jesus, but it goes both ways, such that we are, asthey say, Christ’s hands and feet. Jesus ministers to the world through us. Assuch, as we bear fruit in the Spirit, we bring glory to God.

Image Attribution: Gogh, Vincent van, 1853-1890. Vineyards with a View of Auvers, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=55980 [retrieved April 23, 2024]. Original source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fil....

April 23, 2024

Gospel as Work of Art: Imaginative Truth and the Open Text (David Brown) - A Review

GOSPEL AS WORK OF ART: Imaginative Truth and the OpenText. By David Brown. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company,2024. Xviii + 572 pages.

While the canon of the NewTestament might be "closed," or at least it is as complete aspossible. I realize that some argue for the inclusion of other texts includingthe Gospel of Thomas, but it would appear that we have we need to provide asufficient foundation for our Christian witness. When it comes to interpretationof the New Testament, and more specifically, the four Gospels, it is not quiteas simple. So there seems to be room for imagination and even an open text thatoffers new visions of the Christian faith. The question before us concerns howwe might best interpret scripture to gain new insight and perhaps even newrevelation when it comes to the things of God. With that question in mind, wemight ask how releasing the imagination might be part of the process. Many ofus, who preach and teach, have been well-trained in the historical-criticalmethod of biblical interpretation, which does a good job of getting us as closeas possible to the original context and even the original meaning of the text. Forthose of us who eschew doctrines of inerrancy, we are less worried byrevelations that the Gospel accounts might conflict with each other. While thismay be true, might there be more to the Gospel story than what thehistorical-critical method might reveal? So, with that in mind: might weenvision the Gospel as a Work of Art?

Gospel as a Work of Art isthe title of David Brown’s book, which serves as an invitation to explore theGospels through our imaginations, such that the text itself is understood to beopen. He does so by drawing on artwork, poetry, and other art forms, includingprose. In the course of this book, Brown seeks to challenge the idea that theBible, and especially the Gospels, form a closed system, “such that theimagination can at most illustrate propositional belief, and that revelationceased with the closure of the canon” (p. xxi). In inviting us to use ourimaginations to engage with Scripture he challenges both conservatives andliberals who are thoroughly influenced by the Enlightenment and often fail to embracethe imagination as a source of meaning and revelation. Rather their roots inthe Enlightenment often serve as a straight jacket on the religiousimagination. Readers will find that Brown doesn’t fit our stereotypes ofconservatives and liberals, such that it’s often difficult to place him on thatspectrum. That is refreshing in an age of polarization. What we will discoveris that Brown is a scholar and theologian of distinction. He is an Anglicanpriest who has taught at Oxford, Durham, and St. Andrews Universities. Hisscholarly work has focused on philosophy, theology, as well as religion and thearts. He brings all of this scholarly backgroundinto conversation with biblical scholarship.

Brown is concerned that modernChristians, left and right, fail to recognize that the Gospels themselves areexpressions of imaginative truth, such that the Gospel writers often turned toinvention to get their understanding of truth across to their audience.Unfortunately, too often we are led to believe that invention in the case ofthe Gospels is somehow a pejorative thing. We read books that suggest that theGospels and other biblical writings are forgeries. Brown takes a differentperspective, one that allows for invention, such that the original writers madeuse of their imagination to convey truth. That same imagination can be releasedto embrace an open text that speaks anew in each era. This might not provide a “firmfoundation,” which many look for. However, it might open up new possibilities forinsight into the things of God.

With this commitment to releasingimaginative truth, David Brown offers us a book filled with artwork, poetry,and excerpts from literary works, all of which give imaginative expression tothe Gospels. The book is beautifully designed, having been printed onhigh-quality photographic paper. Since the book is over five hundred pages inlength, it is quite heavy. While there is an aesthetic quality to the book,that is not his primary concern. It is a question of the message that theseartistic forms provide. It is divided into three sections that focus on foundations,resources, and significance.

Part 1 is titled Foundations. Thisopening section of the book is comprised of four chapters. The first twochapters focus on the legacy of the Enlightenment when it comes to biblicalinterpretation. The opening chapter gives us a sense of Brown’s concerns, forit focuses on “Religious Control and the Spiritual Imagination." Here hesuggests, rightly I believe, that fundamentalism is essentially the fruit ofthe Enlightenment. We see this in the focus on propositional truth orrevelation. In the effort to discover precise definitions of theology, whetherfrom the right or the left, the imagination was shut down. Chapter 2 focuses onthe question of “Meaning and an Open Text.” Here he discusses such things asthe quest for the historical Jesus and what openness looks like when it comesto texts. These two foundational chapters are followed by two chapters thatfocus on discovering imaginative truth through art (Chapter 3) and Literature (Chapter4).

With these foundations set, we canturn in Part 2 to "Resources Then and Now." In the three chapters inthis section, Brown "explores the resources available to Jesus in shapinghis view of God and the divine purpose, but in a way that seeks to developparallels and analogies with subsequent reflection on these sources, includingin the present day" (p. xxvii). He writes that “for Jesus to function asthe basis for the Christian faith,” there must be sufficient overlap such that “hislife and values” are “intelligible to us” and when appropriately modified “functionadequately in their new context” (p. 252). The three chapters in this section focuson resources "Through Prayer and People'" "Mystical andNatural;" and "Responding to Inherited Traditions." He addressesthe question of the distance between the ancient and modern worlds, noting theprocess by which historians of the New Testament seek to address the distance.His focus, on the other hand, is identifying a solid core that “allows us to transitionrelatively easily between our world and that of Jesus Christ” (p. 258).

The third Section, which is titled"Significance," is the longest section of the book. It includes sevenchapters. The first of the seven chapters asks the question of why the Gospel?Brown writes that in this section he focuses on how the evangelists treatedwhat Jesus said and did. He notes three characteristics of what appears in thisfinal section— "a search for meaning in the present; various strategiesfor escaping the consequences of the past (not just sin but also fear, anxiety,and uncertainty); and, finally a future sense of purpose or vocation." (p.261). In this section, Brown explores what he calls layers of revelation,miracles as signs and symbols, and parables, along with chapters on death andresurrection. He concludes the book with a chapter titled "The Openness ofFaith." Before you get the idea that Brown is advocating a form of postmodernismor pushing for relativism, that is not the case. What he offers here is aninvitation to make use of our imagination as we engage with the Gospels so thatthese ancient texts might speak to the present. He is not dismissive ofhistorical-critical studies, but he believes there is more to the story thanwhat these tools of the Enlightenment reveal. As he notes in Chapter 14, “TheOpenness of Faith,” He shares his concern that “one of the most depressingfeatures of contemporary approaches in theology is the extent to which itsvarious subdisciplines maintain independence of one another. At their worst,biblical scholars assume that the Bible is all that is needed for Christiandoctrine. Systematic theologians sometimes behave no better.” So, he offers adifferent perspective, from a theologian’s perspective, what he believes is a “moreopen approach that seems demanded by the way in which doctrinal development hasin fact occurred” (pp. 498-499).

By making use of art andliterature, both of which are expressions of the imagination, David BrownInvites us to envision the Gospel as a Work of Art. It is a vision of doctrinaldevelopment as we experience the Gospels anew through these art forms. To getthere, Brown (and Eerdmans) have produced a beautifully illustrated book thatpushes beyond the Enlightenment so that we might fully inhabit the message ofthe Gospels and an open faith. Even if and where we have differences of opinion,Brown provides the opportunity to break free of the religious controls thatprevent us from fully appreciating the message of Jesus.

April 22, 2024

Time for a Bath of Welcome—Lectionary Reflection for Easter 5B (Acts 8)

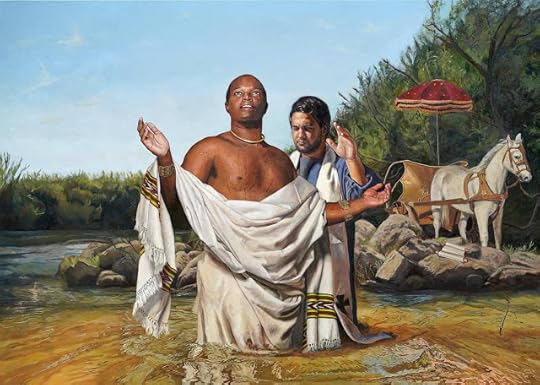

The Baptism of the Ethiopian, by Blair Gordy Piras

The Baptism of the Ethiopian, by Blair Gordy Piras

Acts 8:26-40 NewRevised Standard Version Updated Edition

26 Then an angel of the Lord said toPhilip, “Get up and go toward the south to the road that goes down fromJerusalem to Gaza.” (This is a wilderness road.) 27 Sohe got up and went. Now there was an Ethiopian eunuch, a court official of theCandace, the queen of the Ethiopians, in charge of her entire treasury. He hadcome to Jerusalem to worship 28 and was returninghome; seated in his chariot, he was reading the prophet Isaiah. 29 Thenthe Spirit said to Philip, “Go over to this chariot and join it.” 30 SoPhilip ran up to it and heard him reading the prophet Isaiah. He asked, “Do youunderstand what you are reading?” 31 He replied,“How can I, unless someone guides me?” And he invited Philip to get in and sitbeside him. 32 Now the passage of the scripturethat he was reading was this:

“Like a sheep he was led to theslaughter, and like a lamb silent before its shearer, so he does not open his mouth.33 In his humiliation justice was denied him. Who can describe his generation? For his life is taken away fromthe earth.”

34 The eunuch asked Philip, “Aboutwhom, may I ask you, does the prophet say this, about himself or about someoneelse?” 35 Then Philip began to speak, and startingwith this scripture he proclaimed to him the good news about Jesus. 36 Asthey were going along the road, they came to some water, and the eunuch said,“Look, here is water! What is to prevent me from being baptized?” 38 Hecommanded the chariot to stop, and both of them, Philip and the eunuch, wentdown into the water, and Philip baptized him. 39 Whenthey came up out of the water, the Spirit of the Lord snatched Philip away; theeunuch saw him no more and went on his way rejoicing. 40 ButPhilip found himself at Azotus, and as he was passing through the region heproclaimed the good news to all the towns until he came to Caesarea.

**************************

In theopening chapter of the Book of Acts, as Jesus and his disciples prepare for hisdeparture (ascension), Jesus commissions his followers to be his “witnesses inJerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth, but onlyafter they have been empowered by the Holy Spirit (Acts 1:8). The first sevenchapters of the Book of Acts focus on the emergence of a fledgling community ofJesus followers in Jerusalem. These chapters depict a church that isexperiencing growth and the accompanying challenges that growth brings. We readabout the attempt to hold everything in common so that no one is in need, butthings don’t quite work out as planned. There is a story about a couple whopretend to give all, but hold back some things. That doesn’t end well (Acts 5).Then there are questions about whether everyone is being treated equally, whichleads to the creation of a new order of ministry so that the Greek-speaking Jewsget their share. The seven spirit-filled men who are chosen for this ministryinclude at least two people who take on preaching roles. One of the seven,Stephen, ends up being martyred, while another named Philip becomes a missionary,such that the first steps beyond Jerusalem.

Chapter8 of the Book of Acts describes the aftermath of Stephen’s death. SupervisingStephen’s execution is a man named Saul, who will take the lead in persecutingthe fledgling church. This led to the scattering of the church. Among those wholeft Jerusalem during this time of trial was Philip, one of the seven. He wentto Samaria, where he preached and brought healing to the people in this region.That led to the establishment of the first community of “Jesus People” followersoutside Jerusalem. That’s a story in itself, but what we see there is the firstborder crossing, for Samaritans were distantly related but separate from Jews. ButPhilip isn’t finished quite yet. After he got things started in Samaria, anangel appeared to Philip and told him to go down to a spot along the roadbetween Jerusalem and Gaza (mention of Gaza at this moment should lead us tostop for a moment and pray for the inhabitants of that stretch of land that isexperiencing great trauma).

Philipfollowed the angel’s directions and headed toward the aforementioned road.While he made his way to this road, he met up with an Ethiopian Eunuch, who wastraveling this road after being in Jerusalem. We’re told by Luke that thisEthiopian man was quite important since he worked for the Candace, queen of Ethiopia(not modern Ethiopia but a region at the southern end of the Nile Valley),overseeing her nation’s treasury. He was returning home after worshipping inJerusalem. This suggests that he might be Jewish since he went to Jerusalem toworship and was reading Jewish scripture, but that doesn’t fit very well withthe direction that Luke’s narrative is taking. There is also the question ofthe Eunuch’s physical situation as an eunuch, such that following Deuteronomy 23:1 he would be excluded from the people of God, though Isaiah 56:1-8 suggeststhat a time is coming when eunuchs and foreigners would be included in thepeople of God. Thus, as Eugene Boring and Fred Craddock note, “Luke sees theEthiopian as a transitional figure who worships the Jewish God, reads theJewish Scriptures, but is still an outsider to the people of God” [People’s New Testament Commentary, p. 395].

As theymeet up, Philip the Evangelist comes alongside the man’s chariot. Hearing himread out loud a passage of scripture from the prophet Isaiah, Philip asks “Doyou understand what you are reading?” The Ethiopian replies by noting that heneeds someone to explain this passage, so he invites Philip to join him in the chariot.They read together this passage from Isaiah 53:7-8, a passage that speaks ofone who is like a sheep led to slaughter, one who was denied justice, and whoselife was taken from him. Having received this invitation, Philip interprets thepassage, using it to point to Jesus.

Lukedoesn’t share with us what Philip told the Ethiopian official, but whatever hetold him, the man responded favorably. Perhaps Philip said something about themessage found in Isaiah 56, which speaks of restoring to the people of Godthose who are eunuchs. Something also musthave been said about baptism—perhaps Philip shared Peter’s formula from Acts 2:38when asked what they must do to be saved: “Peter said to them, ‘Repent, and bebaptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ so that your sins may beforgiven; and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit.’” Whatever Philipshared with the man, upon seeing a pool of water alongside the road, he asked Philipwhat might prevent him from being baptized.

Philip, who had already baptized the Samaritanbelievers, didn’t hesitate to baptize this new follower of Jesus. He didn’t prescribethree years of catechesis as we see prescribed in the Second Century. Instead,he had the driver pull the chariot off to the side of the road. They got out ofthe Chariot and Philip baptized the man into the realm of God. Not only that,after the man came out of the water (it is clear he was immersed), Philip wascaught up by the Spirit, such that the “eunuch saw him no more.” But Philip’sdisappearance didn’t seem to bother the eunuch who “went on his way rejoicing”(Acts 8:39). As for Philip he landed in Azotus and went on his way proclaimingthe good news all the way to Caesarea. Thus ends the story of Philip’sministry. However, it is another boundary-crossing event in the life of the newly-bornChristian community.

Philip’s story offers us a look athow the early Jesus Movement expanded beyond its base in Jerusalem. We see inthese two stories from Acts 8, how the Spirit moved in the lives of people whowere considered outsiders to the People of God. Samaritans were a despisedpeople, and it is interesting that while Philip evangelized and baptized theSamaritans it took a visit from Peter and John for the Spirit to fall on themin a demonstrable way, perhaps so that the two communities might be reconciled inthe Spirit. As for the eunuch, we might see him as one who is a sexual minority,such that his body made him an outsider to the people of God. But he too iswelcomed into the community through baptism. Might this passage serve as an entrypoint for those who have been excluded from the church because of their sexualorientation or gender identity? That Luke includes this story along with thatof the Samaritan mission suggests that this is meant to be understood inclusively.In this case, baptism serves as the means of initiating into the realm of God onewho traditionally has been excluded.

Perhapswe might hear in this story a word about the work of the Holy Spirit who pushesthe boundaries we set for ourselves. Right after we hear about Philip’sministry, we read in chapter 9 about the call and inclusion of Saul of Tarsus,the one who had been the lead persecutor. He will become a key figure in theexpansion of the church into Gentile territory, though first Peter will serveas the instrument of inclusion of Cornelius and his Gentile family (Acts 10-11). History has shown us that the church born from Jesus’ incarnateministry, has strayed from the inclusive ministry of people like Philip. Wehave a habit of remaining within our comfort zones, sitting in the same pew,talking to the same people at coffee hour, etc. It’s not that we mean to snubthe newcomer, it’s just we would rather stay in our comfort zone. However, that’snot what happened with Philip, who experiences something of “divine compulsion.”As Willie James Jennings points out Philip didn’t initiate the encounter withthe eunuch, the Spirit put him in a position to encounter the man. Thus, Jenningswrites: “The Spirit is driving a disciple where the disciple would not haveordinarily gone and creating a meeting that without divine desire would nothave happened. This holy intentionality sets the stage for a new possibility ofinteraction and relationship” [Acts: Belief, p. 87]. Jenningsreminds us that down through history, the church has combined evangelizationwith civilizing people, but the two have nothing in common. Thus, we would be wiseto read this story as a celebration of diversity within the body of Christ.

Whatword does Philip’s encounter with the Ethiopian Eunuch have for the churchtoday, especially as the broader culture is moving back into its silos, where diversity,equity, and inclusion are considered inappropriate for our times. In responseto this movement inward, such that we seek to protect our own positions insociety, we hear Philip preaching a different message when it comes to Jesus. Itis a message not only of inclusion but overcoming marginalization. As MiheeKim-Kort notes, both the Ethiopian and Philip experience forms of mutualconversion, such that we see here a “glimpse of how certain power structures gosideways, crumble, and fall when we encounter and listen to those who stand atthe intersection of marginalized realities.” It is thus, a liberating momentthat produces joy for both men. Thus, “they both experienced a transformation,participating in a shift initiated by the Holy Spirit” [Connections, p. 252].

As weponder this message we hear an invitation to attend to those transformativemoments of encounter, where we also might experience that shift that isinitiated by the Holy Spirit. Those elements of identity that can marginalize aperson, in this case, ethnicity, and sexual identity, no longer stand in theway of entering the realm of God. The man remains an Ethiopian and a eunuch,but he also becomes a follower of Jesus through baptism. That leads to joy onhis part. As for Philip, well, he still has work to do which takes him toAzotus and then from there Caesarea and beyond. The story of expansion and inclusionwill continue with the call of Saul of Tarsus and then Cornelius and hishousehold.

April 21, 2024

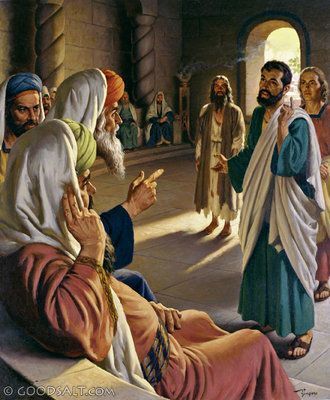

By What Authority? A Sermon for Easter 4B (Acts 4)

When Peter and John went to the Temple to pray they encountered a man who had been lame since birth. When the man asked for alms, they healed him. After that the man who couldn’t walk got up and danced for joy. This display of excitement on the part of the man who had been healed drew a crowd. As this crowd gathered in Solomon’s Portico, Peter took that opportunity to preach a sermon that focused on the resurrection of Jesus (Acts 3).

When the religious authorities heard about this disturbance in the Temple, they got annoyed, especially because Peter and John were proclaiming “that in Jesus there is the resurrection of the dead.” You see, the Temple authorities, including Annas the High Priest, were members of the Sadducees Party, which didn’t believe in a resurrection. So they had Peter and John arrested (Acts 4:1-4).

This morning we pick up the story on the day Peter and John stood trial in the Temple Court because they had caused a commotion in the Temple. The Temple authorities, most of whom rejected the idea of the resurrection, wanted to know who authorized Peter and John to go about healing and preaching in the Temple. The authorities led by Annas, the High Priest, along with other members of the high priestly family, asked Peter and John: “By what power or by what name did you do this?”

I can empathize with the religious authorities because once upon a time I served as the chair of the Commission on Ministry for the Michigan Region of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Just like the Presbyterian Commission on Ministry, the Disciples Commission is responsible for authorizing the ministries of its clergy and holding them accountable to the region’s expectations.

Obviously, these two Apostles didn’t get their credentials from the Temple authorities, who wanted to know why they thought they could come into the Temple and begin preaching without their permission. They had a point because it’s important to vet the people who preach and teach in our churches. Although I’m not Presbyterian, I’ve been vetted. The church submitted my contract to the Presbytery and I filled out a number of forms, and I got my “approval” letter from the Presbytery. So, even though I remain a Disciples of Christ minister with standing in the Michigan Region, I’m fully authorized to preach here at First Presbyterian while Pastor Dan is gone.

While I have the proper credentials, the Temple authorities weren’t so sure about Peter and John’s credentials. So when they pressed the two Apostles for more information about who authorized them to heal and preach in the Temple, Peter took the opportunity to preach another sermon. Luke tells us that as Peter began to speak, he was “filled with the Holy Spirit” and boldly declared that Jesus of Nazareth, the one whom, according to Peter, they had killed, had been raised from the dead by God. It was the risen Jesus who authorized their ministry. Even though the religious authorities rejected Jesus’ ministry, since he didn’t have the proper credentials either, Peter told them that God had credentialed Jesus by raising him from the dead. Peter turned to the Psalms to support his claim that while the religious authorities collaborated with the Romans to have Jesus executed, God had made him the cornerstone of a new work of God. Yes, “the stone that was rejected by you, the builders; it has become the cornerstone” (Acts. 4:11; Ps. 118:22).

The religious authorities raised an important question because down the centuries people have heard a call to ministry, and have been empowered by the Holy Spirit to preach the good news in word and deed, but faced questions about their authorization to preach. This was true of Jesus, Peter, Paul, Francis of Assisi, and a whole score of women, people of color, and many others who haven’t fit the expectations of the religious authorities. But, the Holy Spirit often opens doors that others have closed. When the religious authorities in England closed their pulpits to John Wesley, he began to preach in the fields and declared that “The world is my parish!”

Now I’m not against the proper vetting of preachers. After all, I served as the chair of a commission on ministry and I’ve had my call to ministry authorized by the proper authorities. Nevertheless, even though I believe there is value in this vetting process, history shows us that the Holy Spirit often lifts up voices who stand outside the normal channels of authority so that a word from God can be heard by the people. We need to remember that not only did Jesus, Peter, and John, lack the proper credentials, but so did most of the prophets of the Old Testament. These prophets often spoke challenging words to people in authority, which didn’t make them very popular with those authorities.

When it comes to Peter’s defense of his ministry in the Temple, he let it be known that they were on trial simply because they had done a good deed in the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, whose ministry God had authorized by raising him from the dead so that he could be the cornerstone of a new work of God in the world.

Peter’s closing words in his defense have proven to be rather controversial. We need to remember that he was on trial because he had proclaimed that God raised Jesus from the dead. So, Peter told the authorities that when it comes to Jesus, “there is salvation in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given among mortals by which we must be saved.” Many have interpreted this statement in a rather narrow and exclusive way, such that one must confess faith in Jesus to enter heaven. I know this perspective well because I once embraced it. While it can be read in an exclusive way, I believe it’s also possible to read it in a more inclusive manner.

I don’t believe Luke or Peter were speaking about the eternal destiny of people who hadn’t heard the Christian message or who followed other religious traditions. They were seeking to answer the religious authorities' question about who authorized them to preach about the resurrection of Jesus. Peter answered their question by asking the authorities to acknowledge Jesus’s authority in this matter. They wanted the authorities to recognize that the risen Jesus had changed the lives of his followers and they simply wanted others to have the same experience.

When it came to their own experiences with God, Peter and John couldn’t imagine any other way of experiencing spiritual wholeness except through a relationship with Jesus. Peter doesn’t offer us a detailed theology of salvation, but he is convinced that Jesus is the way of salvation.

While we often think of salvation in terms of being a ticket to heaven, the concept of salvation is much broader than that. The Greek word that we translate as salvation has several meanings, including healing, reconciliation, and wholeness. Rather than dive into that conversation I’d like to invite us to consider a different question.

That question has to do with the difference Jesus makes in our lives. Why does Jesus matter to you? Several years ago the acronym WWJD was all the rage. People wore bracelets with those initials to remind them to ask the question: “What Would Jesus Do?” That’s a good question because it invites us to consider what it means to be a follower of Jesus in the modern world.

While we might not know the answer to everyone’s ultimate destiny, we can seek to live in a way that reflects Jesus’ vision of wholeness in an often broken world. The starting point in answering that question begins with the two commandments that Jesus emphasized: Drawing from the Old Testament, Jesus calls on us to love God with our entire being and love our neighbors as we love ourselves. When Peter and John offered to heal the lame man, they acted out of love. Love stands at the center of what it means to be a follower of Jesus. So we read in 1 John that “God is love, and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them” (1 Jn 4:16). By embracing Jesus we experience the life-changing reality that is the love that is God. It is this love that serves as our authorization for ministry in the world. As Paul wrote to the Corinthian Church, in Christ, we are called to be ambassadors of reconciliation (2 Cor. 5:20).

If we embrace the way of love, then the question of our eternal destiny will take care of itself. As this word from 1 John reminds us, to abide in love is to abide in God. If we abide in God, we participate in the divine nature. Eastern Christians refer to this pathway as theosis. This pathway, according to the Russian Orthodox theologian Vladimir Lossky, involves “divine love, which is simply grace, appropriated in the depths of our being.” This love is “an uncreated gift— ‘a divine energy—which continually inflames the soul and unites it to God by the power of the Holy Spirit. Love is not of this world, for it is the name of God Himself” [Lossky, Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church, p. 212].

What does it mean for us to be followers of Jesus? I believe it involves participating in the love of God, which Jesus embodied, and with which we have been empowered through the Holy Spirit. When it comes to the question of authority to engage in acts of love, that authority comes to us from Jesus, whom God raised the dead so he might be the cornerstone of this new work of God.

Preached by:

Dr. Robert D. Cornwall

Acting Supply Pastor

First Presbyterian Church

Troy, Michigan

April 21, 2024

Easter 4B

Image Attribution: Poussin, Nicolas, 1594?-1665. Saints Peter and John Healing the Lame Man, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=58397 [retrieved April 20, 2024]. Original source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi....

April 19, 2024

Called to Bless: Finding Hope By Reclaiming Our Spiritual Roots - A Path of Spiritual Reconstruction

In 2021, my book Called to Bless was published. It is in essence a theological memoir that offers a path for those who have experienced spiritual deconstruction and wonder what is next. Many leave Christianity, but is it possible to reclaim parts of one's past experiences, such that something new can emerge. My own spiritual journey has taken me to several places from Episcopal to Disciples of Christ, each stop has left a bit of spiritual DNA that helped form the person who exists today. My hope is that what I've discovered can help others along their journey.

I am grateful to Grace Ji-Sun Kim for writing the foreword to the book. She commends the book and its author (me), as it "generously shares his life journey of seeking the divine, encountering the Spirit, and living into the Spirit. Cornwall explores spirituality with honesty and reflective sensitivity, asking us what it means to not only encounter the Spirit but what it means to live being filled with the Spirit."

If you want to hear more about the book, I invite you to check out Brian Kaylor's interview concerning the book for Dangerous Dogma.

With that in mind, my publisher (Wipf and Stock) is offering a 40% discount on the book. To order a copy, go to the book page at: https://wipfandstock.com/9781725268685/called-to-bless/ Please use the coupon code: CALLEDTOBLESSCORNWALL.

*************

Below is an excerpt from the book, along with endorsements for the book.

I am who I am, spiritually, because of the spiritual DNA Icarry. My journey has been a circuitous one. I have traveled from the church ofmy birth, the Episcopal Church, to the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ),the church of my mature years. Along the way, I’ve been part of several otherfaith communities, including Pentecostals, Baptists, Presbyterians, and theEvangelical Covenant Church. My theology is eclectic. I’ve suggested thiseclecticism is due to my being a historical theologian rather than a systematicone. My theology professor in seminary, Colin Brown, reinforced the idea thatthere is no one system of theology, which is why we didn’t have a specifictextbook. Over the years, I’ve borrowed from Karl Barth, Jürgen Moltmann,Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Jon Sobrino, Elizabeth Johnson, Athanasius, theCappadocians, Augustine, John Calvin, Open Theists, and many more. I know thatthese can be strange bedfellows (think of Calvin and Augustine alongside TomOord), but I’ve come to believe that few of us are theological purists. Anotherway of describing my journey is to use the word “pilgrim.” Diana Butler Basswrites that “becoming a pilgrim means becoming a local who adopts a new placeand new identity by learning a new language and new rhythms and practices.Unlike the tourist, a pilgrim’s goal is not to escape life, but to embrace itmore deeply, to be transformed wholly as a person, with new ways of being incommunity and new hopes for the world.”

It is said by some that we should live in the present. Thatis true, but it’s important to remember that the present only exists for amoment before it becomes the past. As for the future, it is always beckoning usforward. Jürgen Moltmann reminds us, “Original and true Christianity is amovement of hope in this world, which is often so arrogant and yet sodespairing. That also makes it a movement of healing for sick souls and bodies.And not least, it is a movement of liberation for life, in opposition to theviolence which oppresses the people.” Whatever spiritual DNA we draw from thesefounding visions, if it’s true to the calling given to Abraham and hisdescendants, then it will be a vision of hope, healing, and liberation. Thus,it will be a call to bless.

What is true of us as individuals is also true forcongregations. Congregations are formed by people who bring their variousspiritual journeys and life experiences into the community. Some participantsgrow up in the church and others do not. Some spend their entire lives in onetradition, while others have been wanderers (much like Abraham, the wanderingAramean, who is the father of Israel). When we gather together as a community,or better yet, as siblings in the family of God, we contribute our diversespiritual DNA into the church’s existence. This contributes to the diversityand complexity of the congregation, even one steeped in a particular tradition.The members/participants in a congregation contribute their spiritual DNA, butso does the Tradition of which they are part.

So, for example, consider my denomination, the ChristianChurch (Disciples of Christ). Contributors to our identity as a movement anddenomination include the Presbyterian heritage of the Disciples founders. Italso includes the time spent by the Campbellites among the Baptists. They drewfrom the Reformation, along with the British Enlightenment (John Locke, forexample). Then there is the secular DNA contributed by their American context.The movement emerged shortly after the birth of the new nation. Thomas Campbellcontributed a founding document to the movement that he titled The Declarationand Address. The word “Declaration” was used purposely as a signal that thiswas a revolutionary document. Sometimes we Disciples see ourselves as part ofthe Reformed tradition, but if so, we aren’t an “orthodox” version of thattradition. The founders purposely threw off the creeds and faith statementsprized by their Presbyterian colleagues and ancestors.

If we take this a step further, individual believers and thecongregations of which they are members contribute their spiritual DNA to thelarger church, making the Christian “religion” a rather complex organism. Inour diversity and complexity, we find our purpose as a community in that callgiven to Abraham and Sarah. Their call is our founding vision, one that wasembodied and renewed and passed on to us in Christ Jesus. That calling, whichrequired them to leave their homes and set out for an unknown land, eventuatedin a fountain of descendants, who are called to be a blessing to the nations.It is a calling that has been passed on from generation to generation until itincorporated we the readers of this book, whether Jew or gentile, for all of usare heirs of this call to be a blessing to humanity and all of creation. Whilethe future might be open, might we envision that moment when all things cometogether, and the blessings promised to Abraham and Sarah reach theirfulfillment?

I did not see a temple in the city, because the Lord GodAlmighty and the Lamb are its temple. The city does not need the sun or themoon to shine on it, for the glory of God gives it light, and the Lamb is itslamp. The nations will walk by its light, and the kings of the earth will bringtheir splendor into it. On no day will its gates ever be shut, for there willbe no night there. The glory and honor of the nations will be brought into it.(Rev 21:22–26, NIV)

Praise for Called To Bless

“What does a Bapti-costal, Episco-matic, Presby-vangelical,Disciple of Christ, and Covenanted Follower of Jesus look or sound like?Perhaps a child of Abraham who has inherited the divine mandate of being ablessing to others, even indeed to the ends of the earth. Anyone seeking tomake sense of their varied spiritual journey will find Robert Cornwall a sureguide and companion.”—Amos Yong, Professor of Theology and Mission, Fuller TheologicalSeminary“To get at who we are, we must tell stories. Even in thetelling, we shape who we might become in the future. In this story-orientedbook, Bob Cornwall draws together diverse stories in hopes of explaining ouridentities. Cornwall’s narration is worth the listening!”—Thomas Jay Oord, author of The Uncontrolling Love of God, GodCan’t, and other books“This is an insightful book, designed for people who want toexamine and explore their faith. It is written by one of the most perceptivepastoral theologians of our time, whose work makes us think deeply about ideasof tradition and continuity of faith in the modern world. It is also a bookwhich draws Christians together rather than divides or separates.”—William Gibson, Professor of Ecclesiastical History and Director of theOxford Centre for Methodism and Church History, Oxford Brookes University,United Kingdom“Bob Cornwall asks, ‘Who am I? Where do I come from? Wheream I going? What is my purpose in life?’ Such questions are entrenched in theearly twenty-first century. Cornwall points to Abram and Sarai as foreparentswho were given the gracious call from God to show the way of blessing toothers. By demonstrating the way of blessing, the couple would be blessed. Twothings happen. (1) The number of paths to blessing expands as human experiencebecomes more diverse. (2) Communities lose blessing as life wears them down.Cornwall shows readers how to rediscover the generative power of the foundingblessing and to witness to blessing in new forms in new contexts.”—Ronald J. Allen, Professor of Gospels and Letters, Emeritus, ChristianTheological Seminary, Indianapolis“This book provides a theologically informed case study,based on the author’s life experiences, that is intended to show individualChristians, pastors, church leaders, and congregations how to find a fruitfulbalance between their past traditions and their Christian witness for thefuture while living faithfully in the present. Reflection questions forindividuals and congregations following each chapter are designed to helpreaders as they respond to this challenge.”—Keith Watkins, Professor Emeritus of Practical Parish Ministry,Christian Theological Seminary, Indianapolis

April 18, 2024

A Faith of Many Rooms: Inhabiting a More Spacious Christianity (Debie Thomas) - A Review

A FAITH OF MANY ROOMS: Inhabiting a More SpaciousChristianity. By Debie Thomas. Minneapolis, MN: Broadleaf Books, 2024. 184pages.

Too often Christians live in theologically crampeddwellings, with little room to move or welcome others into the dwelling place.As a result, we often fail to truly understand God's gracious and welcomingnature. Therefore, we need reminders that Jesus was and is a welcoming person.We see this in his eating habits and messages of love and mercy. If this istrue then it is appropriate that our theologies reflect the openness that Jesusexhibited as he revealed the nature of God in and through his life, death, andresurrection. Fortunately, some people and communities embrace a spaciousChristianity.

If you seek a more open and"spacious" Christianity, then you will be blessed if they choose toread Debie Thomas's A Faith of Many Rooms. This book is a beautifullywritten and compelling exploration of a spacious Christianity. The author,Debie Thomas, brings her own spiritual journey into the conversation. Sheshares this message of a “more spacious Christianity” by bringing into theconversation her background as an Indian American Christian. Born into anevangelical family today Thomas is an Episcopalian, serving as a minister atSt. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Palo Alto, California. She is a columnist forthe Christian Century and author of Into the Mess and other JesusStories.

Although Thomas is Protestant,having been raised in Protestant churches in India and the United States (herfather was a pastor serving both predominantly white and Indian congregations),she traces her spiritual roots much further back in time, to the faithcommunity planted in her ancestral homeland of Kerala in Southern India. It isthere, in Southern India that St. Thomas is said to have ministered and, in theend, martyred for his faith. As such, her first language as a child was the Malayalamlanguage. It is Thomas' story of doubt and service that permeates Thomas' book.

This is a book about belonging.Thomas begins by introducing the reader to the word Nadhe, a word thatis treasured by her immigrant family, a word roughly translated as birthplace,mother country, heart of belonging, or home. It is a word that brings to mindher ancestry in a region where she was born, but from which her familyimmigrated shortly thereafter. Nevertheless, though Thomas grew up in Boston,she spent many summers in Kerala. Therefore, this ancestral homeland serves asthe foundation for her spiritual journey. She speaks in the book about experiencingdislocation and finding it difficult to belong. This is a situation that sheshares with many bicultural people. In part, this is the story of her journeyto experience a sense of belonging. Of course, it's not just bicultural peoplewho feel that they don’t belong spiritually, as many others find it difficultto find a spiritual home, especially as church membership shrinks. So, even asshe shares her own story of seeking that place of belonging, she explores thechanging geography of belief. Thus, part of the story is Thomas's path of discoveringa spiritual home that is different in many ways from the one she inherited.That inherited faith was, as Thomas shares with us, rather male-centric, patriarchal,and theologically narrow. She eventually discovered that she did not fit in theevangelical church of her spiritual origins.

After Thomas provides us with alengthy introduction that sets the parameters of the book, Thomas takes us on apilgrimage to India. In a chapter titled "A St. Thomas Pilgrimage:Doubt," we journey to Kerala. At the time Thomas took this pilgrimage, shewas a graduate student in creative writing at Ohio State University, attemptingto write a thesis about her faith. When she took this journey, she was experiencinga spiritual crisis. As she was in the midst of this crisis, she returned to"the ancient place that birthed my relationship with God" (p. 13). Therefore,we travel with her to the Mount of St. Thomas, a place that Indian Christiansconsider sacred. On that mountain, there is a giant statue of the foundingsaint. At the base of the statue, one finds the words from the Gospel of John,where Thomas declares of Jesus: "My God, my God." By taking us toKerala and this sacred place, we who know the name and biblical story of Thomaslearn something important about the disciple who is best known for his doubts,a disciple, who according to Tradition, became a missionary and a martyr.Whether or not the story of Thomas’ ministry in India is factual, it is thespiritual foundation story for Indian Christians. This is true even if one isnot part of the ancient Mar Thomas church. Therefore, if for no other reason,this opening chapter is worth the price of the book.

While Kerala is the starting pointon this journey to belonging, there is still much more to the story. Thus, wemove from Kerala and the foundational story of St. Thomas’ ministry to herimmigrant story. Thus, in Chapter 2 we join the family as they first immigrateto Switzerland, where her father attended seminary. From there the family movedto the United States, where her father would serve as a pastor. This chapterdraws on Jesus' statement to prospective disciples as a point of orientation.So we consider Jesus’ statement that the Son of Man has "Nowhere to LayHis Head." Thomas uses this imagery to describe her own and her family’sexperiences as immigrants. It speaks to the reality of feelings of notbelonging as well as leaving behind past homes, which for her includes leavingbehind her evangelical home. She notes that "much of the Bible is writtenby, for, and about wanderers. Clearly, there is something powerful,instructive, and transformative about leaving home" (p. 40). I sense thatmany will resonate with this chapter.

From "leaving" we move inChapter 3 "Into the Wilderness: Lost." Here Thomas describes her ownseason of wandering in the wilderness and the feeling of being lost. Thisseason of lostness involves not knowing where one would finally land, while thefeelings concerning what was left behind remain strong. I have heard a numberof my immigrant friends speak of this feeling of lostness and displacement,that feeling of not quite belonging. The question raised here concerns how one mightexperience the life of the pilgrim, such that one holds things lightly as onecontinues down a path uncertain as to the destination.

One way of navigating thisspiritual reality is through storytelling. She explores the act of storytellingin Chapter 4, which is titled "Beyond Belief: Story." She writes that"Stories hold memory and identity, seasons and secrets, sorrows and joys.They give our lives texture and depth, roundedness and fullness" (p. 60).She describes some of the stories that had formed her life, from the Christianrock music she listened to as a youth to the creed that gave a foundation toher faith. But she also shares how she resisted other stories that eventuallybecame hers. She reminds us that belief-centered Christianity isn't necessarilywrong, but it can be "divorced from our enfleshed and storied lives,"and thus isn't enough to sustain faith. (p. 65). She writes that the "beststories affirm that life is complicated, that easy answers rarely satisfy, andthat even the shiniest 'happily ever after' endings exact a price" (p.71).

In Chapter 5, which is titled"She Blows Where She Wills: Spirit," Thomas shares her discovery ofthe way language and stories function, often in surprising ways. So, in thischapter, Thomas draws on the story of Pentecost and the gift of the Spirit. Shespeaks of the diversity of languages present at Pentecost, such that"there is no single language, story, creed, or mother tongue on earth thatcan fully capture the spaciousness and the hospitality of God" (p. 77).It's not that all paths are the same or that the differences between faiths aresurface level for they are not. Therefore, she rightly speaks of recognizingand honoring spiritual differences as being genuine and meaningful. If this istrue, as she believes (and I agree), we can be open about our faith traditionswithout trying to make everything look the same. We can share our story asbeing meaningful to us and perhaps to others, but following Jesus we don'tengage in manipulation or coercion.

In Chapter 6, titled "GettingSaved: Sin,” Thomas explores the question of sin. In exploring this concept,she shares with us how she wrestled for many years with the feeling that shewas a sinner, which led her to strive for acceptance by God and others. Shespeaks of living in fear that she was not right with God. Many will resonatewith her description of her past experiences. Thus, she invites us to consider ourown questions as to the nature of sin and salvation. She helpfully points outthat many progressive Christians shy away from dealing with questions as to thenature of sin and salvation. However, Thomas helpfully writes that "rightlyunderstood, sin and salvation are precisely the roomy, expansive words we needto ground our vocations as Christ's hands and feet in a pain-filled world.Walking away from these core tenets of our faith grants us no more freedom,spaciousness, resilience, or hope that my anxious childhood sprints to thealtar" (p. 89).

From sin, we move to another topicthat many Christians shy away from, and that is lament, the topic of Chapter 7.Thomas writes that too often we find it difficult to embrace lament, eventhough the Psalms are filled with laments. She notes how in her past she practiceda grief-averse faith, a faith that ended up being rather shallow. She remindsus that lament is not faithlessness but is instead an act of faith for inpracticing lament we recognize that things are not yet as they should be. So,even though we are Easter People, "the Easter stories we cherish in theGospels make room for ache, fear, regret, and sorrow" (p. 119).

Earlier in the book, Thomas noted thatthe faith she inhabited when she was young was very male-centered. As shematured spiritually and left behind a narrow evangelicalism, she began torecognize that women bear the image of God. That is the subject of Chapter 8.This is the story of Thomas discovering the feminine side of God and what thatmeans for her as a woman. A roomy church, she suggests, has room for thismessage that God is not male, but allows for differing imagery that empowersrather than restricts. She finds her foundation for embracing her own identityas a bearer of God's image in the incarnation. Thus, "he takes on theparticular flesh of a first-century itinerant Jewish peasant: poor, colonized,and criminalized. It is out of this radical specificity that Jesus includes,embraces, and saves us, in all our specificity" (p. 133).

In Chapter 9 Thomas invites toembrace dissonance and paradox. Thus, she writes "Again and again, the wayof Jesus invites us to hold opposing truths together, in pairings that seemimpossible. This is not to confound us but to show us how wide and spacious therealm of God really is." (p. 141). There is no greater paradox than theTrinity, that God is both three and one. So, we can approach uncertainty not with fear but curiosity, such that we canrecognize that the Christian faith is not a religion of easy answers. If weembrace this truth then perhaps, we might be open to loving those whom we findit difficult to love.Finally, we come to Chapter 10:"Limps and Worms: Wrestling." Here Thomas draws on one of my favoritebiblical stories, the story of Jacob's wrestling match with God. She suggeststhat a truly spacious faith needs to allow for spiritually wrestling matcheswith God. She writes that "wrestling keeps God relevant in our lives; itkeeps God personal. It makes sure that God remains a force to reckon withrather than a dusty relic we stick on a shelf." (p. 168). She alsoincludes the story of Jonah who runs away from God and then finally gives in,preaches doom, and then gets mad when God doesn't destroy the Ninevites. Thus,we are left with Jonah wrestling with God's "scandalous compassion andmercy toward Jonah's sworn enemies."

In her epilogue to A Faith ofMany Rooms, Thomas concludes the story of her spiritual journey towardinhabiting a more spacious Christianity by affirming that there comes a timewhen we will discover a home where we can finally stay put. Therefore, shewrites that she stays a Christian because she found in Christianity the roomyhouse where she belongs. As we walk with her, perhaps we will find that we toobelong in that roomy house.

If we know from the start thatDebie Thomas holds an MFA degree in creative writing, it might not surprise ushow fluid and beautifully written Thomas's A Faith of Many Rooms is. Whilebeautifully written, Thomas also brings exceptional spiritual and theologicalinsight into the book. I expect that readers will resonate with different partsof the book, but to illustrate her theological insight, I found that her chapteron paradox was especially poignant in that she holds together theologicalpositions that many progressive Christians struggle with, such as the Trinityor the resurrection of Jesus. At a time when so many people, especially formerevangelicals, are experiencing spiritual deconstruction, Thomas’ vision of aspacious Christianity may prove inviting. Wherever one is on their spiritualjourney, I believe that Thomas has provided us with a book that can be read andenjoyed and will provide encouragement as we seek a spiritual home in the kindof spacious Christianity Thomas describes in A Faith of Many Rooms.

April 17, 2024

Taking Care of the Sheep—Lectionary Reflection for Easter 4B (John 10)

Peter Koenig, The True Shepherd and the Wolves

Peter Koenig, The True Shepherd and the Wolves John10:11-18 New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition

11 “I am the good shepherd. The goodshepherd lays down his life for the sheep. 12 Thehired hand, who is not the shepherd and does not own the sheep, sees the wolfcoming and leaves the sheep and runs away, and the wolf snatches them andscatters them. 13 The hired hand runs away becausea hired hand does not care for the sheep. 14 I amthe good shepherd. I know my own, and my own know me, 15 justas the Father knows me, and I know the Father. And I lay down my life for thesheep. 16 I have other sheep that do not belong tothis fold. I must bring them also, and they will listen to my voice. So therewill be one flock, one shepherd. 17 For this reasonthe Father loves me, because I lay down my life in order to take it upagain. 18 No one takes it from me, but I layit down of my own accord. I have power to lay it down, and I have power to takeit up again. I have received this command from my Father.”

*****************

Perhapsthe most beloved passage of scripture of all is Psalm 23. It is the scripturepassage most often chosen for funerals. Even if a family doesn’t know muchscripture, they likely know this Psalm. They take comfort in the declarationthat “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want.” The fourth verse reads:“Though I walk through a valley of deepest darkness, I fear no harm, for Youare with me; Your rod and Your staff—they comfort me” (Ps. 23:4 Tanakh, JPS).That image of God, the shepherd, who provides for and protects the sheep, isappropriated here in John 10, as Jesus claims to be the Good Shepherd. In apreview of what is to come, Jesus speaks of himself laying down his life forthe sheep.

As anaside, although this shepherding image is appropriated by the churches to speakof clergy, we must be careful in how we use the image. We may be pastors, butwe are not God or Jesus. As for the people in the church being sheep, thatimage is also problematic, for it suggests an image of spiritual dependence onclergy that can lead to passivity and manipulation (on both ends—I know thisfrom experience). So, while God is ourshepherd, and we are the sheep of God’s pasture, we need not be passive in theway we live our faith.

TheFourth Sunday of Easter is known as “Good Shepherd Sunday.” The Gospel readingsfor Good Shepherd Sunday draw from John 10, where Jesus speaks of himself asthe Good Shepherd. These passages are read along with Psalm 23. In thesepassages from John 10, Jesus addresses a concern for the community goingforward. He contrasts the Good Shepherd who willingly lays down one’s life forthe sheep with the hired hand who runs away when danger approaches. While thehired hand doesn’t have ultimate responsibility for the sheep, such that the hiredhand doesn’t care for the sheep, unlike the Good Shepherd to whom the sheepbelong.

Jesus tellsus here that he is the Good Shepherd. Therefore, he knows his sheep, and thesheep know him. That mutual knowledge reflects the relationship Jesus has withthe Father, whom he knows and who knows him. Knowing here speaks of arelationship that exists between Jesus and the sheep and between Jesus and theFather. Because of the depth of the relationship, such that Jesus cares for hissheep deeply, he is willing to lay down his life for the sheep. That is, thegood shepherd is all in, unlike the hired hand who is only in it for the money(and shepherds didn’t make a lot of money).

As for Jesus, when confronted withdanger, he doesn’t flee but stands firm, laying down his life for his friends.However, even as he laid down his life, he would take it up again. Indeed,Jesus tells his audience “No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my ownaccord. I have power to lay it down, and I have power to take it up again” (Jn.10:18). As for the authority to do this, it came to him from his Father. This reference to taking up his life connectsour reading with the overall message of Eastertide, that of Jesus’resurrection.

One verse that stands out to me isverse 16. In that verse, we hear Jesus declare: “I have other sheep that do notbelong to this fold. I must bring them also, and they will listen to my voice. So,there will be one flock, one shepherd.” Who might these other sheep be to whomJesus must go, so that there might be just one flock? It is important to notethat these “other sheep” will listen to his voice. That would seem to suggestthat they also belong to Jesus. My interest in this verse is rooted in my long-standinginvolvement in interfaith and ecumenical ministry. While it likely is areference to the growing presence of Gentiles in what originally was a Jewishsect, might it have more to say to us as a predominantly “Gentile” church as welive out our faith in a pluralistic world?

We might start by asking thisquestion as laid out by Stephen Cooper:

The “other sheep” of today must bedetermined by the setting in which the word is preached and heard. Who are“other” for us? This line of questioning brings the affluent churches of thedeveloped world into discomforting reflections on the “other” in our midst—inour own societies— and the “others” elsewhere in the world. Both “others” areon the margins of our horizons, the horizons established through circumstance,habit, and counsels of prudence. The key point is that these “others” are Christ’ssheep, just as we are, and they too recognize his voice. [Feasting on the Word, p. 450].

In an increasingly divided world economically andpolitically, our religious divisions, starting within the larger Christiancommunity, work against the idea that we are one flock with one shepherd.Despite decades of ecumenical efforts, we seem as divided as ever. The Lord’sTable, which should be a symbol of unity, remains a point of contention.Efforts to bring about full communion among denominations continue to be achallenge, especially in light of the decline of churches. While the boundariesare less narrow and rigid than they once were, especially when we think of laypeople who move easily from one church to another, they still exist even thoughwe all claim to be part of Christ’s flock. We often divide ourselvesideologically, such that liberals and conservatives each look at the other withdisdain, and thus we tend to live in our own ideological silos while claimingto represent Jesus. Therefore, it would appear that God dislikes the samepeople I dislike. So, who are these other sheep? We might also ask who isn’t present in ourcongregations and fellowship circles. Most churches are racially/ethnicallysegregated. While we can rationalize this as an expression of cultural andlanguage differences, there is an “otherness” to this reality. Economicbarriers are often in play. There are the theological barriers mentioned above,as well as ideological/political barriers. My denomination, especially clergy,was one rather purple. We’re now quite “blue.” Then there is the full inclusionof LGBTQI persons in our faith communities. How might these differences bebridged? What does it mean to say “All are welcome?” Are we open to welcomingthose who hear and respond to Jesus’ voice but are not of “our flock?”

Things get even trickier when wethink in terms of our interfaith relationships. How might they listen to Jesus?I could adopt the idea of the “anonymous Christian,” but that seems ratherpaternalistic. Nevertheless, might we find some shared place of spiritualfellowship that reflects Jesus’ embrace of other sheep? Does Jesus lay down hislife for my friends whose faith professions differ from mine? How might I dothe same?

John invites us to listen to thevoice of the Good Shepherd, who lays down his life for us (and takes it backup). Jesus tells us that the shepherd knows the sheep and the sheep know theshepherd, might we know the shepherd well (be in a relationship with him), knowingthat the shepherd leads us to green pastures and still waters while preparing atable for us in the presence of our enemies. May this be true for us thisEaster season as the Savior leads us “like a tender shepherd.”

April 15, 2024

Who Authorized Your Ministry? —Lectionary Reflection for Easter 4B (Acts 4)

Acts 4:5-12 New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition

5 The next day their rulers, elders,and scribes assembled in Jerusalem, 6 with Annasthe high priest, Caiaphas, John, and Alexander, and all who were of thehigh-priestly family. 7 When they had made theprisoners stand in their midst, they inquired, “By what power or by whatname did you do this?” 8 Then Peter, filled withthe Holy Spirit, said to them, “Rulers of the people and elders, 9 ifwe are being questioned today because of a good deed done to someone who wassick and are being asked how this man has been healed, 10 letit be known to all of you, and to all the people of Israel, that this man isstanding before you in good health by the name of Jesus Christ ofNazareth, whom you crucified, whom God raised from the dead. 11 ThisJesus is

‘the stone that was rejected byyou, the builders; it has become the cornerstone.’

12 “There is salvation in no oneelse, for there is no other name under heaven given among mortals by which wemust be saved.”

**************

Thefirst reading as defined by the Revised Common Lectionary once again takes usto the Book of Acts. Once again, the text centers on the proclamation ofChrist’s resurrection. The reading for the previous week came from Acts3:12-19, where we read of Peter’s sermon after the healing of the lamebeggar in the entrance to the Temple. That sermon, which actually ran to verse26 of Acts 3, caught the attention of the religious authorities. That may havebeen due to the fact that Peter was not very kind when speaking of theauthorities, blaming them for Jesus’ death and calling on them (and all thepeople) to repent. Not only did Peter and John challenge the authorities, butthey were doing a pretty good job making converts of the people. So, theleaders had them arrested (Acts 4:1-4).

The reading for the Fourth Sundayof Easter picks the story up at the trial before the Council that takes placethe day after the arrests. Luke suggests that the rules, elders, and scribesgathered in Jerusalem with Annas, the High Priest, and his family (Caiphas,John, and Alexander) in attendance. It should be noted here that the HighPriest and most of the leadership in attendance would have been members of theparty of the Sadducees, a conservative party that rejected the resurrection andcollaborated with the Romans. Seemingly absent here are members of the party ofthe Pharisees, who like Jesus’ followers, believed in the resurrection.

When the trial began with Peter andJohn standing before this group of religious leaders, the two apostles wereasked: “By what power or by what name did you do this?” That questionopened the doors for Peter to launch into another sermon, with the goal ofdemonstrating the nature of their authority to speak as they did. At least inthe early going, it appears that Peter is willing to take whatever opportunitygiven to him to bear witness to Jesus and his resurrection. This occasion wasno different. The question was asked, and Peter had an answer.