David W. Tollen's Blog

October 19, 2022

Hello world!

Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start writing!

The post Hello world! appeared first on David Tollen.

September 10, 2020

Please visit us at Pints of History!

Click above to visit Pints of History!

For future posts about history and education, please visit David Tollen’s blog:

Pints of History

www.PintsofHistory.com.

The PoH blog has a long history, dating back to 2011, (and a big future, too) so you’ll find lots to grab you there!

The post Please visit us at Pints of History! appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

August 7, 2020

King George III: The Abdication that Never Happened

George III was Britain’s king during the American Revolution. Research during the last five years has revealed a surprise about the king. In 1783, as the Revolutionary War drew to a close, he almost abdicated—as revealed by a draft abdication speech in his own hand, recently discovered. The king’s speech blames the loss of the colonies on selfish partisanship within Britain. (Apparently, little has changed in the U.K.—or in its former colonies.) King George also concluded that he had nothing left to offer. “A long Experience … has gradually prepared My mind to expect the time when I should be no longer of Utility to this Empire; that hour is now come; I am therefore resolved to resign My Crown and all the Dominions appertaining to it to the Prince of Wales my Eldest Son and Lawful Successor and to retire to the care of My Electoral Dominions the Original Patrimony of my Ancestors.” (The last point means he planned to move to his family’s duchy in Germany.) George III would have been England’s first monarch to abdicate—and only the second for Britain’s other key realm, Scotland, following Mary Queen of Scots, who abdicated in favor of her infant son in 1567. Apparently, George’s advisors convinced him to stay, and in fact, he ultimately reigned longer than any other English king. So the U.K.’s first abdication had to wait until 1936, when King George’s descendant, Edward VIII, gave up the throne. (Edward’s motives were less patriotic. Britain’s government more or less pushed him out, thanks to his questionable loyalty and his plan to marry a divorced American Nazi sympathizer.)

The post King George III: The Abdication that Never Happened appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

June 26, 2020

This Week in History: Althing

This week in 930 CE, the chieftains of Iceland established the Althing, which remains the country’s parliament. It’s the world’s oldest surviving legislature. Northmen (sometimes called Vikings) had arrived on the island about 60 years before, and now they set about to govern themselves – meeting outdoors at a place called Thingvellir, which means “assembly fields,” near modern-day Reykjavik. The original Althing had 49 members – mostly district leaders – as well as a Lawspeaker, who presided while sitting on a rock called the lögberg, or law rock. The Althing met every year, drawing large crowds who camped nearby, since any free man could attend. In fact, it was the year’s main social event. Today’s Althing doesn’t look so different, except that it moved inside after almost 900 years on the field at Thingvellir, it has 63 members, and it generally invites the population to participate by watching on TV.

The post This Week in History: Althing appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

June 11, 2020

This Week in History: The Treaty of Tordesillas

This week in 1494, the Spanish and Portuguese Empires signed the Treaty of Tordesillas—brokered by the Pope. The treaty divided the globe between the two great powers, fifty-fifty.

The Treaty of Tordesillas drew a line through the Atlantic, from pole to pole. New lands (non-European countries) to the West belonged to Spain. That gave it the Americas, which Columbus had recently “discovered” for the Spanish king and queen. Portugal got new lands to the East, which gave it Asia—again confirming recent exploration, since Portugal had rounded the horn of Africa and sailed to Asia shortly before Columbus’ first voyage. As it turned out though, South America extended further East than either party realized, so the great line actually cut through the southern continent. That gave Portugal a claim to part of the Americas—and that’s why the people of Brazil speak Portuguese to this day.

The amazing thing about the Treaty of Tordesillas is that the two sides honored it more or less consistently. The other European powers, however, did not—since they hadn’t participated, and since Protestant powers like England and Holland didn’t care about a treaty brokered by the Pope. So as the two Catholic empires lost power over the centuries, the treaty lost relevance. Still, Spain and Portugal never terminated it. And their former colonies, like Argentina and Chile, invoked the treat as late as the 20th Century, to support their territorial claims—as has did Indonesia.

Image: the Cantino planisphere (1502), depicting the Tordesillas Merdian, splitting the world

The post This Week in History: The Treaty of Tordesillas appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

May 29, 2020

This week in history: Ashmolean Museum

This week in 1683, the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology opened in Oxford. It was the world’s first university museum and was named after Elias Ashmole, who in 1677 had given Oxford University what became the museum’s first collection. Construction also began in 1677. The current museum building was finished in 1845.

That first donation from Elias Ashmole ranged from antique coins to zoological specimens. The most noteworthy piece may have been the stuffed body of one of the world’s very last dodos. Unfortunately, by 1755 the dodo’s body was so moth-eaten that only the head and one claw remained. Today, the Ashmolean has more than 110,000 items, including drawings by Michelangelo and Raphael, paintings by Pablo Picasso, and a Stradivarius violin.

Have you visited the Ashmolean Museum? What were your favorite pieces? If you haven’t visited, what would you be most excited to see?

Photo of the museum’s main entrance taken in 2014 by Lewis Clarke used with permission under CC BY-SA 2.0.

The post This week in history: Ashmolean Museum appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

May 16, 2020

Coronavirus Would Not Have Disrupted Our Ancestors’ Lives

A virus circles the world, killing 1% of the population or more, particularly the elderly … and people just go about their business. Even in countries that understand contagion, no one healthy stops working, and neither do most of the sick. In fact, if you suggest staying home, most people think you’re crazy. Why manufacture an economic disaster? That’s how our ancestors would react to coronavirus, from the ancient world through early modern times. Their lives already involved a steady risk of death from acute, fast-acting disease, so this comparatively mild new illness would hardly set them back.

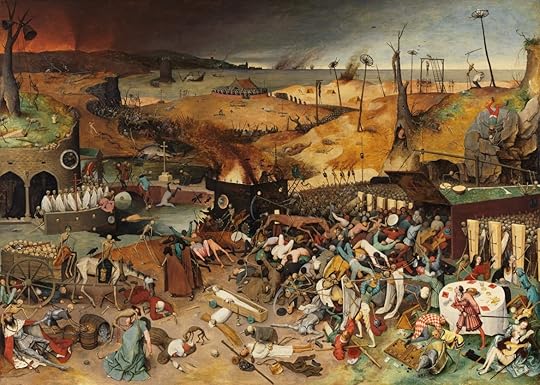

The Triumph of Death, Pieter Bruegel the Elder. c. 1562. Click for a closer view of death’s regular assault on our ancestors.

Today, we fear cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic slow killers. (At least, we did before coronavirus temporarily shifted our focus.) Those “diseases of affluence” threaten us because of some uniquely modern bad habits, like eating processed foods, smoking, living surrounded by toxic chemicals, and exercising less than the average walrus. We also have the luxury to worry about chronic diseases because we’ve made such progress against fast-acting, acute diseases. The latter, however, loomed over the pre-industrial world. They cast such long shadows that our ancestors were used to the threat of death from sudden illness.

Acute Disease before the Industrial Revolution

St. Sebastian praying for a gravedigger during the 541-542 AD Plague of Justinian, Josse Lieferinx, 1493

Pre-industrial societies regularly faced death from acute diseases like pneumonia, dysentery, flu, malaria, diphtheria, typhoid, and food poisoning, as well as infected injuries. And these illnesses struck every level of society, not just the poor. Dysentery is acute diarrhea, and its victims include at least four kings of France and three of England The latter include John “Lackland” (Robin Hood’s Prince John, 1216) and Henry V (Shakespeare’s war hero, 1422). But dysentery felled rulers far beyond these backwards medieval kingdoms. Its victims also include emperors of the Roman, Byzantine, and Mughal empires and rulers from rich and sophisticated states across the world. And of course, dysentery killed countless non-royal big names, like Hernán Cortés (1547), Sir Frances Drake (1596), and Renaissance philosopher Erasmus of Rotterdam (1536).

Malaria can probably claim even more big names. Those include Pope Urban VII (who reigned only twelve days thanks to the disease, 1590), Oliver Cromwell (1658), three members of Renaissance Italy’s mighty Medici family, and probably Alexander the Great (323 BC).

Yet Malaria and dysentery represent just a small sample of the fast-acting microorganisms threatening our ancestors. Several of the acute diseases listed above had similar death tolls, as did many more vicious microscopic bugs.

Young Victims and Epidemics

Generally, these acute diseases did not restrict their malevolence to the elderly. Alexander the Great died at 32, while England’s Henry V was 35, and malaria’s three Medici victims died at 24, 18, and 15. In fact, children bore most of the risk of acute diseases. During the Roman Empire, half the children died by age five. And the Romans had better doctors than most people before or since, until modern times.

Some of these illnesses lurked in the background, killing here and there, while others struck in waves, as epidemics. And while our ancestors probably experienced many epidemics like COVID-19, killing 1% or more, history rarely records them. To those keeping records, a noteworthy epidemic killed far more of its victims, including among the young. A smallpox outbreak could kill 30% of the infected — or more among children — while cholera and yellow fever ranged from 5% to 50%. And the Black Death of 1347 — possibly an extinct strain of plague — killed about half its victims when it spread through the lymph nodes (“bubonic plague”). If it spread through the blood or lungs, the death rate may have been 100%.

The Hunter-Gatherers’ Advantage

Interestingly, our only ancestors not accustomed to regular acute illness were the most primitive: hunter-gatherers. These foragers lived in bands ranging from 30 to 100 people, and they could trek vast distances without seeing anyone. So they didn’t offer the population-density necessary for human-focused viruses and bacteria to evolve or spread. Nor did hunter-gatherers live with pigs, chickens, cattle, or any other animals, except dogs (after about 40,000 years ago). So they offered illnesses few opportunities to jump from animals to humans. (Hunting and eating animals does create those opportunities, but not as often.)

Humanity’s acute diseases mostly evolved and spread once farming came along, with its denser populations and daily close contact with livestock.

Fear of the Epidemic but No Recession

Contrary to common belief, our pre-industrial ancestors often lived into their 60s or 70s — at least, those who survived childhood did. So I don’t mean to suggest that life was cheap. Past people would have feared coronavirus. But unlike us, our ancestors already expected much of the population to die of acute disease. That means word of an illness killing one in a hundred — at most a handful per village — would not shock them. Coronavirus would add little to the background level of disease-driven death. In fact, an epidemic that mostly spared the young would almost come as a relief.

Today, we stand on the verge of a recession, thanks to our efforts to stop coronavirus. That decision would baffle our ancestors.

Monte Python and the Holy Grail exaggerates the regular role of death in Medieval Europe — with excellent comic effect — above. But the movie still makes a fair point.

© 2020 by David W. Tollen

The post Coronavirus Would Not Have Disrupted Our Ancestors’ Lives appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

May 15, 2020

This week in history: Kublai Khan

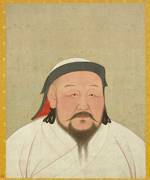

This week in 1260, Kublai Khan became ruler of the Mongol Empire. Grandson to the well-known Genghis Khan, Kublai was the empire’s fifth Khagan, or Great Khan. Kublai succeeded to the throne after the death of his eldest brother, Mongke. The latter died in 1259 without naming a successor, and almost immediately Kublai’s younger brother, Ariq Boke, held a Mongol great council that named him Khagan. But Kublai then held his own great council, got declared Khagan, and went to war with Ariq Boke. The Mongol civil war that lasted 4 years, and of course Kublai won.

The civil war, however, divided and weakened the Mongol Empire, and soon it broke into several smaller empires. Kublai ruled as great Kahn, but his true realm was China, and he wielded less power of the rest of the empire than had any of the earlier Great Khans.

Kublai’s legacy includes many conquests but also some prominent losses. That includes three failed attempts at conquering Vietnam and two failed invasions of Japan.

The post This week in history: Kublai Khan appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

May 11, 2020

Independent Press Award

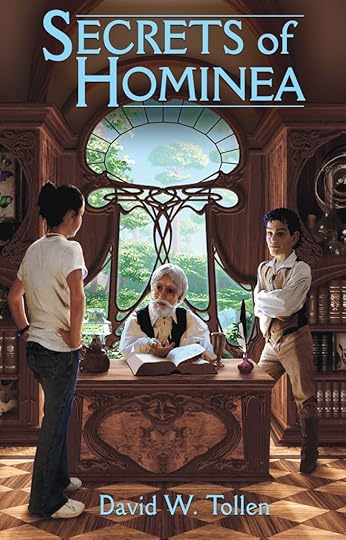

I am very proud to announce that my second novel, Secrets of Hominea, just won an award: Distinguished Favorite in the Juvenile category of the Independent Press Awards.

Secrets of Hominea is a magical novel for middle grade readers (4th through 8th grade), using fantasy to teach history and science.

My first novel, The Jericho River, won several awards, including first place at the Next Generation Indie Awards and the London Book Festival, as well as a bronze medal at the Reader’s Favorite Book Reviews and Awards. This is the first award for Secrets of Hominea, published in late 2019.

You can learn more about Secrets of Hominea below, and you can purchase either book in paperback or e-book at Amazon and other retailers.

A magical, educational novel that teaches science and history. Ideal for homeschooling, distance learning, and the classroom.

Alison Pulido gets more than she bargained for when she cuts middle school. She follows a strange little man into another world. It’s a beautiful land where evolution breeds mythic people and animals. It’s a realm of satyr dukes and gnome rebels, giant priestesses and dwarf spies, noble unicorns and monster rats, along with cataclysmic floods, stone age battles, and imperial intrigues – all shaped by forces of history and science. Alison learns tales of all these wonders from her little man and his scholar companion. But Hominea is no safe place for a young Homo sapiens. Soon, Alison finds herself caught up in the other world’s struggle: in the battle between truth and ignorance.

SECRETS OF HOMINEA educates and entertains middle school readers, along with 4th and 5th -graders. Teachers and parents will love the educational resources, including questions for discussion and reading guides. Come follow Alison through the portal and into this magical other world …

The post Independent Press Award appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

April 24, 2020

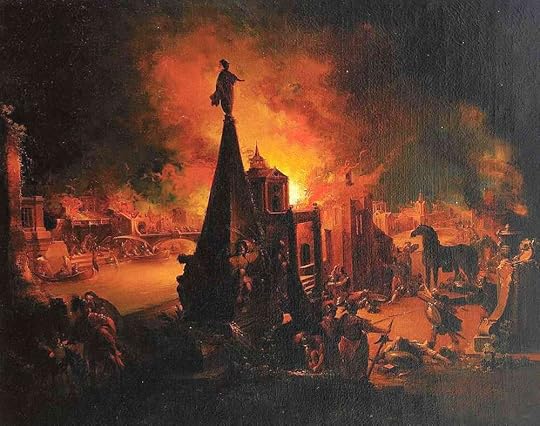

The Fall of Troy and Its Warning for 2020

This week marks the traditional reckoning date for the fall of Troy, in 1183 B.C. The ancient Greeks calculated the date centuries later, and it may not be far off. Whatever the timing, the city’s fall offers a frightening warning for our world in 2020.

We know about Troy because of a blind ancient Greek poet. Homer told the tale of the Trojan War in his great poems The Iliad and The Odyssey. Modern readers long considered Homer’s tales fiction, but during the 1870s, a treasure hunter dug up ruins in Turkey that match Homer’s Troy. Fire destroyed the buried city during the 1250’s B.C., not long before the traditional date for Troy’s fall. And many of the ruins match the features Home described in The Iliad.

To Homer and his readers, Troy’s fall seems an isolated event. But Troy was not the only city to fall during the years before and after 1200 B.C. In fact, every major civilization of Mediterranean world fell – the Hittites, Babylonia, Syria and Palestine, the Mycenaean Greeks themselves, etc. – except Egypt. And Egypt almost fell. This wave of disaster ended Bronze Age civilization and launched a long, brutal dark age. Scholars have offered many explanations, including invasions (e.g., the famous “Sea Peoples”), climate change, disease, and barbarians with iron weapons. But the most likely explanation is that Bronze Age civilization had become too fragile, with each society dependent on extended trade networks for survival. When the troubles above disrupted the trade routes, they triggered a cascade of disruptions, leading to network collapse and disaster.

If that sounds familiar, it’s because the modern world is also a civilization surviving on a web of trade networks. And we’re facing a massive disruption to our network, COVID-19, with others looming, like climate change. Let’s hope we do better than the Bronze Age kingdoms, particularly Troy.

The post The Fall of Troy and Its Warning for 2020 appeared first on DavidTollen.com.