Greg Houle's Blog

June 11, 2025

Interview with The Collector

July 11, 2024

Witch City

While most of the accused witches in 1692 lived in Salem Village, which is now known as Danvers, the city of Salem, for obvious reasons, takes most of the “credit” today for the witch trials.

And they’ve leaned in hard on this identity over the years, to say the least.

Salem is often called “Witch City.” The Salem Police Department incorporates a witch flying on a broom stick on its patch (And the chatbot icon on the city’s website is also a flying witch.) Can you guess what the Salem High School mascot is? Of course you can!

While it’s difficult to blame the city for trading on its infamous past—particularly when more than a million tourists visit Salem annually, mostly to revel in its witchiness during the fall ‘spooky’ season—it’s entirely incongruent with the actual events that occurred more than 330 years ago.

Of course, there were no witches in Salem three centuries ago. And as far as we know, nobody ever claimed to be a practicing witch, as we would view them today. To a seventeenth-century Puritan, a witch was somebody who had sold their soul to the devil. Somebody who existed well within the Calvinist belief system that the Puritans practiced. For Puritans, witches weren’t practicing a nature-based spirituality. They were doing the devil’s work to undermine everything that they held dear. It was deadly serious business. Being a witch was nothing short of the worst thing a person could be.

But, then again, maybe Salem is just being smart. A million visitors a year can’t be wrong, right? Maybe connecting Salem’s infamous past with present-day witch practices is the way to go. At least it seems to be working for them.

Still, it makes me wonder how many of those million plus people who visit Salem each year actually understand what really happened there.

What do you think?

June 24, 2024

Who was Thomas Putnam, Jr.?

One of the narrators of my novel, The Putnams of Salem: A Novel of Power and Betrayal During the Salem Witch Trials, is Thomas Putnam, Jr.

Thomas, who turned 40 years old as the witch hysteria struck in 1692, is my seventh great grandfather on my mother’s side. He was a third generation resident of Salem Village and his grandfather, John Putnam, as well as his father, Thomas Sr, arrived there from Buckinghamshire, England around 1634. John was in his mid-50s and Thomas, Sr. was close to 20 years old at the time of their arrival in America. John Putnam acquired large tracts of land and he and his son continued to build upon the family’s holdings in the decades ahead. It wasn’t long before they were among the wealthiest residents of the community.

Historically, wealthy families have often followed a similar trajectory: the first generation establishes wealth, the second generation builds that wealth further, and the third generation squanders the wealth entirely. While the Putnams didn’t exactly follow this traditional roadmap, Thomas, Jr was never quite able to build upon the successes of his grandfather and father. In fairness, the deck was stacked against him. The growing population of Salem Village created more competition for land, making it more difficult for the people of Thomas’ generation to build wealth like their forefathers had during the early days of the Great Puritan Migration.

Thomas served as a sergeant in the military during King Philip’s War, which was a brutal, two-year conflict between English settlers and native peoples fought throughout New England during the mid-1670s. The impact of the war on those who experienced it cannot be overstated. King Philip’s War was transformational, helping to set into motion increasingly fraught relations between settlers and natives, as well as a greater sense of independence between Americans and England.

Around the time of the war, Thomas married Ann Carr. The couple would go on to have a dozen children, one of whom is the other narrator of my novel, his oldest daughter, Ann Putnam, Jr., who was twelve-years-old in 1692.

Thomas famously lost out on much of his expected inheritance from his father when the widowed Thomas, Sr. married his second wife, Mary, who was from the rival Porter family. The couple had a son together, Joseph, who inherited the lion’s share of the Putnam family wealth.

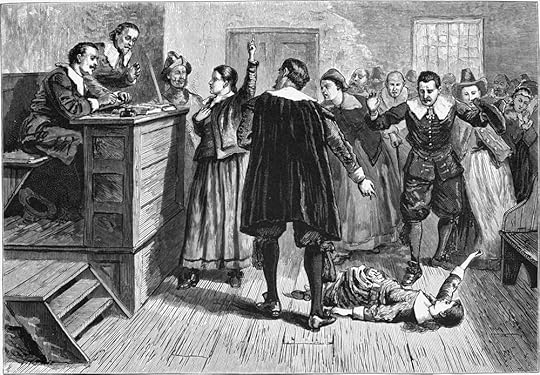

When the witch crisis struck, Thomas was an enthusiastic participant. By the end of the year, he had accused over 40 people of witchcraft and his daughter had accused more than 60. Thomas was also thought to have written the depositions of many of the afflicted girls himself. He also wrote letters to the judges and magistrates, encouraging them to arrest and convict certain individuals.

When the tide turned against the witch hunt in the fall of 1692, we don’t know how Thomas reacted. Yet it’s easy to imagine his frustration and anger when he suddenly found himself on the wrong side of history. Did he feel contrition or shame? Did he feel slighted or wronged in some way? We’ll likely never know.

Thomas and his wife both died—just two weeks apart—in 1699, leaving their oldest child, Ann, to care for their remaining children.

Exactly why Thomas Putnam, Jr. took such an active role in the witch hunt remains a mystery. Simple explanations about accusing his neighbors so he could steal their land don’t hold up under scrutiny. Were his prolific accusations an attempt to show “leadership” during the crisis? Was Thomas trying to recapture the fading glory of his family?

Like everything about the Salem witch trials, the truth is far more complex than we would like it to be. In truth, the mystery of why Thomas Putnam, Jr. became such a prolific accuser during the Salem witch trials will likely never be known with any certainty.

May 22, 2024

Why historical fiction is important

When I was a master’s student in history many years ago, I did what many graduate students do: I took myself too seriously.

I wanted to be a good historian. I wanted to be somebody who seeks the truth in the historical record. I wanted to be capable of synthesizing scant pieces of information in order to make it make sense. I never progressed beyond a master’s level study of history, but it wasn’t because of a lack of seriousness. In any case, much of what I learned about being a good historian has stuck with me. And I remain in awe of historians who are capable of stitching together details of the past to provide lucid and meaningful answers about why it’s important today.

As a serious grad student, I scoffed at historical fiction. The idea that anyone would use conjecture when addressing the past—potentially making things up as they go—seemed ridiculous, if not dangerous, to me. Shouldn’t we just stick to what we know is true?

Yet, as the great novelist, E. L. Doctorow, once said, “the historian will tell you what happened. The novelist will tell you what it felt like.”

For an event that occurred over three hundred years ago in a relatively primitive colonial backwater, the Salem witch trials are fairly well documented. Yet, as any good historian will tell you, much of the primary source material (such as the transcripts of the examinations of the accused written mostly by Reverend Samuel Parris, for example) are potentially biased. Still, this primary source documentation gives us a pretty good sense of the who, what, when, where, and how of the witch crisis. We generally know, for example, who was arrested and when, who made the accusations against them, what occurred during their trials, whether they were executed or not, and even much of what was taking place politically behind the scenes as well. But what we do not know in any meaningful way is perhaps the most critical component for understanding what the Salem witch crisis was all about.

What were the people involved thinking and feeling as it was happening?

That is the question that drew me to writing a historical fiction novel about the Putnam family during the Salem witch crisis. Afterall, this family—my own relatives—where at the very center of it all, making dozens of accusations that helped to propel the events forward at a frenetic pace.

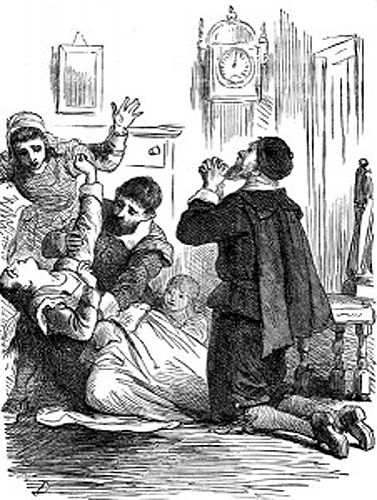

When Ann Putnam, Jr. began acting strangely that cold winter in early 1692, claiming to see the specters of her neighbors who poked and prodded her, what did her father Thomas think? When Ann and the other so-called “afflicted” girls suffered “fits” that caused them to contort their bodies into impossible positions, make strange vocalizations, and claim to see devilish visions, how did that make the people of Salem feel?

Ultimately, how they felt about these highly unusual happenings and, more importantly, how those emotions caused them to react, is essential to understanding the “why” of the Salem witch crisis. Simple explanations about lying aren’t enough. Yes, there were undoubtably liars involved in the Salem witch crisis, but it is not credible to pin the entire tragedy on their actions. More than anything else, it was the human emotion of fear generated by this collection of odd occurrences that drove the crisis forward. Yet how are historians supposed to quantify such things?

This is where historical fiction comes it. Novelists have the freedom to credibly explore these important human emotions in ways that historians simply cannot. Most of the details in The Putnams of Salem are factual (with one notable exception) but I focused on exploring the emotional decent that Thomas and Ann made as they got deeper into the crisis. After all, they were human beings, with a full range of human emotion. And there’s little doubt that those emotions were getting a serious workout in 1692.

While historians are often at a loss when asked to quantify how human emotions such as fear, anger, jealousy and the like impact events, historical fiction thrives at it. And because of this, reading historical fiction can often provide a more complete picture of how these critical human feelings can be a driving force behind a historical event.

April 25, 2024

The Tragedy of Ann Putnam, Jr.

One of the narrators of my book, The Putnams of Salem, is twelve-year-old Ann Putnam, Jr. Ann was among the first people to be “afflicted” by so-called witches during the Salem witch crisis. Her claims of affliction happened early, shortly after the first girls—Betty Parris and Abigail Williams—claimed to be afflicted during the cold, early days of 1692.

Ann spent the entire witch crisis—most of the year 1692—suffering from her affliction. She claimed to see visions, contorted herself into unusual positions, complained about being pinched and poked and prodded, among other things. With the help of her father, Thomas Putnam, Jr. (who is the other narrator of my book), Ann became the most prolific accuser during the witch crisis, pointing her finger at more than 60 people, including nearly all of those who were executed.

Ann’s infamous role in this tragedy cannot be denied. Without her claims, it is very likely that fewer people would have been wrongly convicted, jailed, and executed.

But why did she do it?

Did Ann really suffer from some kind of affliction that caused her to see visions? Was she simply making it all up? Did she step into a lie and then find herself unable to get out of it? Was she a victim of conversion disorder, or what we used to call mass hysteria?

It’s our desire as human beings to want to provide definitive answers to such questions. Unfortunately, however, the truth is not so easy to know. In many ways, that’s what makes this moment in history so alluring for us today. Much like our current-day obsession with true crime, we can’t help but rack our brains and wonder how such a thing could have happened. But, as much as we’d like to have an easy answer, it alludes us.

One thing we do know for certain is that the world that young Ann Putnam inhabited was a frightening one. And there are several reasons why this was the case.

The first was embedded in her religion. Puritans believed in the notion of predestination, which means that a person was destined by God to go to heaven or hell before they were even born and there was nothing that that person could do change their destiny. Imagine a child sitting in the meeting house listening to the minister spewing fire and brimstone sermons about devil and the fiery pits of hell, all the while knowing that they might be destined to be sent there for all eternity. That's pretty harrowing, particularly for a young person. It’s easy to image how these troubling thoughts could stir up palpable anxiety and fear.

The second reason is embedded in the world that they lived in. Late-seventeenth-century New England was a fraught and dangerous environment. The relative calm that had existed for decades after the Pilgrims first landed in Plymouth was broken during the mid-1670s when King Philips’ War broke out across the region. Conflict between European settlers and the native peoples of the region became a constant and existential threat. Horrific stories—both real and embellished—circulated widely across the region. And many who experienced such brutal conflict ended up in Salem, directly involved with the witch crisis.

We also can’t forget that Ann was a twelve-year-old girl. That’s not an easy age for anyone—whether they lived more than three hundred years ago or are living today. Perhaps it was Ann’s desire to be seen, to fit in, to be part of a group that led her down this dark path. Or perhaps she was guided there by her father, an imposing and forceful presence in her life.

In any case, Ann’s story is a tragic one. A few years after the witch hysteria faded, both her parents died just weeks apart. She was an orphan, forced to care for her many siblings, at the ripe young age of twenty. A few years later, in 1706, Ann wrote a confession of sorts that was read to the congregation by the pastor of Salem Village church. She had been asked to do so as a condition of her becoming a member of the church.

It her confession, Ann wrote, “I, then being in my childhood, should, by such a providence of God, be made an instrument for the accusing of several persons of a grievous crime, whereby their lives were taken away from them, whom now I have just grounds and good reason to believe they were innocent persons…”

While we shouldn’t feel too much pity for somebody who caused so much needless harm to so many innocent people, Ann is a tragic figure of her own. Ten years after her confession—at the relatively young age of 37—Ann died. She never married and never had children.

One can imagine the internal torment that Ann must have endured during the remaining twenty-five years of her life after the witch crisis had passed. She never left Salem, and everyone there knew who she was and what she had done. She was infamous. Of course, none of this excuses her critical role in this tragedy. But it is impossible to ignore the fact that Ann Putnam herself was a tragic figure as well.

In many ways, Ann’s story helps to illustrate the enormous complexity of this horrific moment in history. There are no easy answers.

March 25, 2024

Debunking myths about the Salem witch trials

The Salem witch trials—like so many moments in history—is plagued by misconception and misinformation. There have been a lot of bad takes over the last three centuries that have stubbornly remained within our midst, and it can be interesting to parse through them and separate the truth from fiction.

Here are three that I think are particularly stubborn and important to dispel:

The “witches” in and around Salem in 1692 were persecuted for their beliefs.

First, and most importantly, there were never any witches in Salem. The people who were accused, convicted, jailed, and executed were not guilty of their so-called crimes. Period.

Furthermore, a “witch” in seventeenth-century Massachusetts was nothing like how we think of a witch today. A witch was not somebody who practiced a nature-based set of beliefs, like, say, Wicca, for example. Or a green-faced woman who stirs a steaming caldron, like in the Wizard of Oz. A seventeenth-century “witch” was somebody who had sold their soul to the devil to obtain some earthly power. While there is little doubt that most Puritans were deathly afraid of witches and the power that they derived from the underworld, witches existed squarely within the Calvinist belief system that Puritans attested to.

The witch hunt was mostly driven by long-standing infighting between neighbors.

There’s little doubt that late-seventeenth-century Salem was filled with conflict—these were litigious people who seemed to revel in suing each other. But to say that the witch crisis of 1692, which resulted in about 200 accusations and 25 deaths, was driven entirely by neighborly infighting is an oversimplification. This was a society that very much believed in the power of the devil to undermine the goodness of their community. And while some of these long-standing squabbles certainly played a role in some of the accusations, in truth, much of the witch crisis was driven by a growing sense of fear that built to a crescendo over the course of the year. The more people claimed to be afflicted, the more accusations that were made. And as more accusations were made, the fear pulsating throughout the community continued to grow. It was a vicious cycle with devastating results.

It was all about property.

Again, property disputes were sometimes the basis of bad blood between neighbors, but they didn’t lead to a witch crisis. Individuals could not gain control over other people’s property by accusing them of being a witch. And the government could not seize the property of those who were accused.

What are some other myths? Let me know in the comments below.

March 23, 2024

What draws us to the Salem witch trials?

What we know today as the Salem witch trials occurred 332 years ago, mostly over a brief seven-month period, in and around Salem Village. The number of Puritan settlers living across the entire region at the time numbered only a few thousand at most. Over the course of this crisis, approximately 200 people were accused of witchcraft, and at least 25 people died because of those accusations—19 convicted and executed, one tortured to death, and at least five more died in jail awaiting trial.

Over the broad scope of history, stretching around the globe, there have been thousands of similar tragedies that have been largely forgotten, particularly more than three decades after they have happened. Yet, our interest in the witch crisis in Salem only seems to grow with each passing decade.

Why is that?

Is it because it involves sensational accusations of witchcraft? Is it because literally millions of us living in the United States today can trace our heritage back to the people involved?

I assume it’s a bit of both of those things…and more.

In many ways, the Salem witch crisis is an ideal microhistory. It’s a compelling, engaging, tragic, horrific story that sheds important light on a timeless human experience. The Salem witch trials are a nearly perfect example of how our fears can overtake all rationality and drive us to do the most horrific things. That isn’t to say that our late-seventeenth-century forefathers didn’t believe wholeheartedly in witchcraft and the power of the devil—they most certainly did. But almost as quickly as the hysteria blew up, it died down completely once cooler heads prevailed. A community had collectively allowed its fear and emotion get the best of it, with devastating results.

Why do you think the Salem witch trials remains such a compelling topic for so many of us today? Let me know in the comments.