David M. Reynolds's Blog

February 8, 2024

TotRT Audiobook released! Meet the cast!

In a process that started way back in August of last year, the Tales of the Risen Tide audiobook is finally out, triggering the rollout of the book in all formats!

I’ve had a lot of questions about my approach to the audiobook, so I’m going to try to tackle some of them here.

Why create an audiobook when your book isn’t even out yet?

With the power of retrospect, I can see it’s not the ‘done thing’ – the self publishing industry isn’t really geared up for it. But it was always the plan and I wasn’t budging – here’s why:

I’m a firm believer that a written story is a substitute for the spoken word, not the other way around. We started out telling stories to each other around a fire, long before writing was even invented. And reading aloud is a huge part of my process: my phone is jam packed with recordings of me reading yesterday’s scenes back to myself so I can polish them before moving on to new material.

I always knew Risen Tide would be an audiobook, and that there are a lot of people out there who find it far easier to enjoy stories that way. Why would I lock them out of coming on the adventure for the first six months after paper release?

Why did you go for a full-cast reading? Nobody does that.

This was something I had to figure out along the way. Originally I was seeking someone to read the whole thing themselves, just like all the audiobooks I love to listen to. The idea of a full cast reading didn’t even cross my mind.

After listening to about 30 auditions, however, it became clear something wasn’t right. I scored everyone on various criteria: some readers had fantastic voices, some could offer a range of accents, some really got the prose and delivered it brilliantly, others made fantastic acting choices when performing the characters. Unfortunately though – nobody scored highly in all areas, and any one of those areas can really let the thing down.

In the end, I tried narrating some myself. Obviously I had a huge advantage in understanding the prose, and most people seem to like my tone of voice, but I knew there was no way I could tackle the voices (just ask my D&D group…).

I was skeptical about constantly cutting between voices, worried it would sound like a radio play, only with ‘he said’ crammed in between each line of dialogue. My good friend and audio engineer Ben made up a quick demo of the scene in the Smikken Sun though, and it was enough to convince me.

Now all I had to do was cast all the actors…

Why are you giving it away for free?

It’s my first book. I don’t have an audience. It’s more important to me at this stage in my journey that thousands of people enjoy my story for free, than a few hundred pay me for it.

I’m a firm believer that if the story is good enough, and the audience is big enough, it will pay for itself in the long run.

Who is in it?

I’m glad you asked – meet the outlaw crew of the Archon:

Luke Sumner (Harry Potter and the Cursed Child) was the first hire. The charm of his audition tape and apparent ease with which he slipped between accents in our first meeting blew my mind. Unfailingly dedicated, Luke read the entire novel before getting started and spent weeks perfecting his performances for Jymn, Cap and the other Archonauts.

Gordon Cooper (Baldur’s Gate III) voices the older, male characters. He’s responsible for Tsar, Node, Lotan, Rasmus, along with various other piratical villains and preachers. I was looking all over to find the right voice for Tsar, and when I found him, it turned out he lived in the same sleepy corner of Devon as me. We must breed good pirates down this way.

Bryony Reynolds (Macbeth the Musical) brings Nix and Daj to life, and worked with me for a time beforehand to define the unique cadence of Nix’s hand-sign. That surname is no accident – Bryony is my cousin!

Mitchell Zhangazha (Save the Cinema) joined the crew fairly late after an extensive search to find a voice for Weylun that could conjure the right mix of vulnerability and yet confidence and excitement when he’s talking about teck.

Maxine Finch (Coronation Street) reads for Syrincs Ren – she might only appear prominently in two chapters, but each time she controls the scene, often with a deeper understanding of the characters around her than they themselves possess.

Eva Eklof (Aber Bergen), brings authentic Scandinavian tones to the Goodmother and Jenn in her latter years. For those of you complaining about the mispronunciation of various narrated scandinavian words throughout the book – Eva did do her duty as a Norwegian and tell me, I chose to read them my way anyway…

Hadley Karimloo (Best Interests). At just 15 Hadleyis the youngest member of the crew, voicing Gam. He recently doubled for Ethann Isidore on Dial of Destiny which meant hanging out with Harrison Ford for six months. Jealous? Me?

I always knew we’d need a real Kiwi to bring Caber to life, and Curtis Te Maari was our man. His audition knocked it out of the park, and we recorded the entire part in one remotely directed session with his local studio in Auckland.

Lastly comes stoic Balder – only 80 words, and the very last piece of the puzzle, Nicholas Contreras responded lighting fast to feedback rounds and got us over the finish line

The enormous task of assembling, editing, mixing and mastering was undertaken by my friend and collaborator Ben Pering, who has been in charge of all the interactive sound design for our Real Life Gaming series of films, such as Real Life Hitman.

And last but not least, long time collaborator Rob Westwood found time while composing for the new Asgard’s Wrath game to write an original piece of music for the title credits.

The audiobook is available for free (two chapters a week) on the Realm Pictures YouTube channel, as well as the Tales of the Risen Tide podcast, or you can find the full adventure on Audible, Spotify, Apple Books and more.

Have you listened yet? Who was your favorite? If you have questions for me or the cast – this is the place to ask.

February 6, 2024

Sneak attacks and rabbit holes – my approach to planning a novel

When it comes to questions about the process of writing a novel, there are three I get asked most often:

How much planning do you have to do before you can start writing?How do you deal with writer’s block?How do you find your style?I’m going to devote three blog posts to answering these questions in the hope that I can point people here when they ask and give them a much richer answer than I could in the moment. Here goes the first:

How much planning do you have to do before you can start writing?

None. Not unless you want it to be any good, that is.

I’ve heard it said that there are two types of writers, those who have every little thing planned out in advance, and ‘pantsers’ – those who write by the seat of their pants, never quite knowing what’s going to happen on the next page.

In practice, I suspect it’s not so much the writer that dictates the approach, but rather the type of story they are choosing to tell. An thriller or murder mystery undertaken with no knowledge of the resolution feels sure to lack satisfying intricacy, while a slice-of-life romance led by the characters is likely to feel forced or formulaic if over-planned. I’m a firm believer hat planning/pantsing is a spectrum, with few (no) writers sitting at one extreme or the other. Everybody plans something, and even the most meticulous planners occasionally wind up surprised by where their characters lead them.

Although the ‘seat of your pants’ approach sounds deeply romantic and exciting, I think my books would be vastly less exciting for the reader if I were to work this way. Consider me firmly in camp ‘plan’. Here’s a snapshot of what that process looks like for me:

On Risen Tide I spent six months planning before writing a single word of prose. The start and end of this period (Jan 1st – Jul 1st) was decided beforehand, to give me some boundaries and keep me accountable.

The end goal of this planning phase was to have a 25-30 page document, each page detailing a chapter of the book. But I don’t start there – that’s not going to happen until around month five.

Everything starts with a blank Google Doc, which will slowly and organically coalesce into sections about locations, characters, factions, culture, creatures and so forth. Some days I’m doing nothing but populating that document, racing to get all my thoughts and ideas down before they fade. Other days I barely touch the document – instead I’m spelunking down rabbit holes in dusty corners of Wikipedia. I love this part – it makes me feel like Gandalf in the archives of Minas Tirith, hunting through ancient legends, obscure inventions, and the surprisingly well-documented history of competitive cheese rolling.

After a few hours each day I ‘save’ my work by bookmarking the 20-30 browser tabs I have open, and then walk away. It’s important to give your brain space to ‘defragment’ everything you are working through, and space for new ideas to germinate.

For me, it’s important to avoid the plot for as long as possible. I know from experience that scenes and setpieces that are written down have a habit of solidifying, and become resistant to change. That’s not to say I won’t note down an idea for a cool sequence – I just try not to let it burrow its way into the actual linear cause-and-effect of the story yet.

Eventually though, the world-building will have taken shape. I’ll know who the major factions are, who the main characters are, what their fears, weaknesses and dreams are. I’ll know how the world works, and how it doesn’t. At this stage (usually about 3-4 months in) it’s time to start playing with potential plot lines. Being a child of the early 90’s, I always imagine this like watching a large JPG load on a dial up connection: first you see the size of the thing, then the rough shapes and blocks of colour, then gradually Princess Leia starts to reveal herself.

Having come from a film background where structure and pacing is far less forgiving than in a novel (see ‘Save the Cat’ by Blake Snyder), I find myself always starting with the roughest shape: the three (four) acts . At their most, most basic these are:

Act 1 – set up the world, the protagonist, and their problem

Act 2A – thrust the protagonist into a new world, meet new friends and enemies, enjoy the ‘promise of the premise’ (it’s a pirate novel – so there had better be some pirate shenanigans)

Act 2B – things get serious, the bad guys are closing in, the protagonist is heading for a fall.

Act 3 – Pulling himself out of the dumps, the hero emerges with a plan to save the day.

There are a few critical beats at the junctions between these acts (honestly, read ‘Save the Cat’) so I usually play with the story in the form of 7-8 bullet points. I’ll knock about a few versions of that for a week before moving on. It’s important to note that unlike a 2-hour movie, a novel can (and perhaps should) sustain much greater deviations from this structure – but it’s a great starting point.

Next I’m breaking things down into groups of chapters. This is just a case of adding bullet points to the acts, so now Act 2A now comprises 3-4 bullet points instead of one (Shoalhaven, Kimpakka, The Cove, West). Now my story is 12 or so bullets long. This is the most dangerous part for me – it’s very easy to cram too much in, or skew your pacing.

Next I’m breaking those bullets down further until every chapter has its own bullet point. For me, a chapter is always going to try to feel like an episode of TV with a clear beginning, middle, end, and hopefully a hanger to draw people into the next chapter. I know this is going to be about 30 minutes of reading, or about four to five thousand words. Now it’s time to be honest with myself about how much I can (or should) cram into each chapter, and how long the finished manuscript will be. I was aiming for 125,000 words with Risen Tide, and ended up overshooting by about 13,000 – nearly three chapters’ worth.

Next is the part I love most – now I get to give each chapter a few bullet points of its own. Then I go through and give them all a few more. Gradually I start to figure out exactly where the hero finds that clue, or when they have that key conversation with their nemesis. Nothing is too firm yet – it’s like a game or Tetris, or a jigsaw puzzle. The opportunity to make rapid changes at this stage will never be repeated – once I get into writing prose even simple 2-second changes can take days (and I won’t want to make them, even if I know I should).

It’s easy to see how we get from here to the end goal of one page per chapter – but I’m wary of leaping ahead too fast. I built three versions of this structure before moving on. Honestly, with every step you take toward prose you are sacrificing experimentation and flexibility. It’s important to take your time and play.

At this stage I should be able to tell the story. I tell it to my friends, my wife, my kids, my cat. If I can’t tell it, or I get stuck, or they get confused, I know there is something janky. That’s not a failure – this is exactly what this stage of the process is for – I do not want to find out when I’ve already committed 100,000 words to paper.

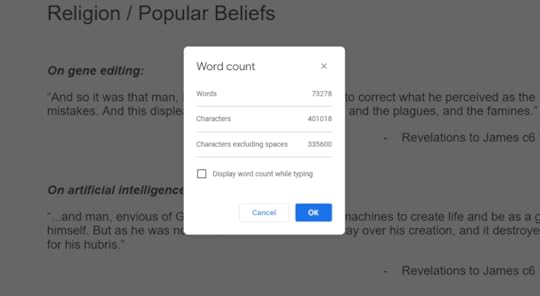

On Risen Tide, by the time I was ready to start turning each chapter into a page, my planning document was 73,278 words long. That’s one chapter short of the first Harry Potter book. I wasn’t kidding when I said I was firmly in the planning camp…

At this stage I had written prose for a novel once before, but not solo (that’s a tale for another day). This would be the first time I was setting sail by myself, and I was a little nervous. Six months of planning had prepared me for what I was about to tackle, but it had done nothing to reduce my sense of quite how enormous the task ahead was. But first – just a page per chapter. Easy. I sat down and wrote two-thirds of a side of A4 detailing the prologue.

Piece of cake.

Then I moved on to Chapter One. I had a neat idea that maybe the first bullet-point scene ‘Jymn working aboard the Trossul’ could start with Jymn watching a magfly testing his weld.

I wrote:

“The tiny magfly crawled across the steel plate, two of its eight legs prodding and testing the new joint for weakness — any break in the metal surface where it could begin to gnaw at the rich ferrous within.

Jymn Hatcher watched, studying the creature, his good eye squinting at the jerking mechanical movements that would reveal any flaw in his work — any void or cavity in the weld-bead that held fast the latest patch in the great steel patchwork that made up the ship’s hull.”

You might notice that’s not detail – that’s prose. And that was it – the words started pouring out and suddenly I wasn’t writing a one-page summary of each chapter any longer. The ship had left the harbour and I was writing the whole damn book.

This ‘sneak attack’ approach has gone on to be one of my favourite ‘brain hacks’. If ever I’m putting something off or procrastinating, it’s usually because on some level I’m afraid of tackling it. By getting right up adjacent to it, armed with everything I need, you can almost blur the threshold between not-started-yet and oh-shit-I’ve-started-now. And then you just have to strap in and let momentum take you where it will.

Until the writers’ block strikes. But that’s a blog post all of its own.

What’s your process? Does it look anything like mine? Are you one of these mythical ‘pantsers’? If so – how in the hell does that work?

February 3, 2024

On having a head full of horse-shit

As any creative person will tell you, one of the most common questions you get asked (besides ‘when are you going to get a proper job?’) is ‘where do you get all your ideas’?

Confronted with this question often enough, you could fall into the trap of believing you are blessed with a special power. A unique way of looking at the world that allows these ideas to come to you (and only you). An inalienable ability that can’t be earned, improved, or taken away. It’s a very seductive idea – it requires very little work and it makes you feel special.

But like most seductive ideas, it’s a load of bollocks.

Creativity is a process. It’s something anyone can do, not some magical gift bestowed upon a special few. The only thing that separates ‘creatives’ against the masses is they are the ones who actually bother to create. Everyone can be creative, but not everyone is creative. It’s sort of like saying ‘anyone can run a marathon’ or ‘anyone can sing’ – it’s true (barring any physical limitations), but in practice it is only those who train, flex, and strengthen the necessary muscles who are any good at it.

Training creativity isn’t easy though. Because creative endeavors tend to exist in a world of subjectivity and opinions (instead of objectivity and ‘personal bests’), it is nigh-on impossible to empirically measure progress. And without measurements, it’s very easy to fake it. It’s why there are so many bad writers and bad singers in the world, but very few bad sprinters (it’s very hard to kid yourself into believing that you are faster than you really are).

So, hard to measure = hard to train. You can practice the craft of putting words on a page all you like, and that’s a great skill, but what about the art behind the craft? What about coming up with original concepts about which to write? You can’t sit down and squeeze out 20 reps of good ideas for practice (you can try, but in my experience they tend to lean towards derivative) so how do you grow?

Instead of deliberate, focussed training, the approach I employ looks more like a philosophy than an activity. Like a low-level meditation, a state of mind you must encourage over the years to welcome and cultivate new ideas. It works like this:

Your senses are being bombarded, day in, day out, with external influences. Your heart and your mind are constantly reacting to these things in some way or another. There is no shortage of external seeds of inspiration flooding into your head each day, the thing most people lack is not inspiration, but rather a fertile soil in which these seeds can land and begin to grow.

In short, you need to have a head full of horse-shit. Good, stinky, fertile horse-shit (from what people tell me I’ve been highly successful at this part).

As writers, our job is to awaken something in the reader, to light a fire in them, terrify them, make their heart swell, or to speak directly to their inner child. Deep down, we humans are all the same, and so – trusting in this fact – the writer must turn themselves into an antenna, an ultra-sensitive seismometer that notices every tremor in their own emotional landscape, and records what caused it.

An idea might sit in the fertile soil of your mind for years without sprouting, or it might sprout right away. Most often, I find that ideas like to pair up through a process of free-association. It’s almost like some long-dormant idea has decomposed, and has enriched the soil with its raw elements – then some new seed lands in the soil and finds exactly the nutrient it needs to start growing right away, combined with some element of the former.

Some seeds might stir you deeply, but try as you might you don’t know why, or sometimes even what the reaction was. With these things, I tend to place a marker in the soil – a little reminder to revisit it often and see if there is anything more to be learned.

Sometimes it can be like a great chain reaction. You might spend months burying things in the soil, enriching it with fragments of ideas or feelings but nothing concrete. You might feel that you have nothing tangible to show for all your careful gardening. Then one day something lands in the soil – it might be a painting on someone’s wall, a lyric from a song on the radio, it might be a game your kids are playing – and BAM, it lays down roots deep into your rich soil and before you know it you have a beanstalk bursting out of your ears, and you’re unable to sleep until you write it down.

Some thoughts and observations if you are interested in adopting this way of walking through the world:

Notes are critical. I’ve tried a pocket notebook but had to eventually face the reality that it is no match for the notes app on my iPhone. As soon as something ‘pings’ my antenna, it goes straight into my ‘soil’ note – immediately – however inconvenient (warning: this will take some getting used to for friends and family…). Re-reading these fragments is like aerating the soil, and is a great way to keep things fresh.If you’re doing things right, you should actually feel yourself becoming more sensitive and attuned to the world around you. It can take you by surprise, but embrace it. I find myself regularly moved to tears by things that my younger self would have scoffed at (I’m looking at you Paddington 2). Don’t let old fashioned notions of masculinity prevent you from seeing the beauty in things. If you are scared of what people will think of your feelings, you probably shouldn’t be a writer.Just because you are constantly being bombarded with sensory input doesn’t make all input equal. Busting out of routine, saying yes to things you’re scared of, and putting yourself in new situations will increase the richness of your soil and diversity of your seeds. I often drag my feet attending an event I’m not enthusiastic about, only to find my antenna light up like a christmas tree when I get there.Likewise with hobbies – learn new skills, become a more interesting, rounded person, and you will find plenty of nutrients for your brain-dung. Your job is to be interesting and have interesting thoughts. Habits matter. Everyone has their go-to app for those snippets of time in the cracks between life happening. If you add all this up (thanks, ‘screen time’) the numbers can be staggering. Does your app expose you to new content and ideas? News apps can be great, or even Reddit. Best of all is falling down a rabbit hole on Wiki Roulette.Do you have another approach? Or perhaps more tips and thoughts to add to the above? Feel free to jump in the comments.

PS: Only upon having a friend review this blog entry has it become cringingly clear that even this metaphor is an example of one’s environment fuelling one’s ideas. “Only a writer from rural Devon could cultivate (heh) a creativity metaphor based entirely around manure”. Sorry not sorry.

February 1, 2024

“Why don’t you go and write the book?”

I hadn’t even left school when I fell for my first love. Infatuated with the extensive ‘behind the scenes’ content that came out of the Lord of the Rings film trilogy, my oldest friend and I set about making an hour-long ‘medieval romantic tragedy’ picture, replete with horses, knights and castles. This was long before YouTube existed, so everything we knew (which wasn’t a lot) we had learned from watching and re-watching Peter Jackson and his merry band of Kiwi rogues. My media studies teacher laughed and told me there was no way we could pull it off (this was, and is, like a red rag to a bull for me). We borrowed £4000 from the bank to feed the crew and pay for the costumes and camera hire, and spent what will always be a close contender for ‘greatest summer of my life’ roaming around Devon with our crew of friends, utterly dedicated to the dream of making a movie of our own. I met the second love of my life shortly afterwards (during a brief misadventure at film school) and she helped me assemble the hot mess of amateur footage into something resembling a coherent picture. Eventually we paid the budget back with DVD sales and local screenings, and that was that. But it wasn’t over – I was hooked.

What followed were almost twenty years of pursuing that dream. I didn’t want to simply work in the film industry, I wanted to keep making movies with my friends – the bigger the better. We got up to all sorts of mischief: an hour long zombie action movie with motorbike chases and airstrikes, an urban fantasy retelling of the Arthurian myth, a series of short films spanning two thousand years of Atlantean history – shot entirely underwater. We had a hell of a time, we met our heroes: Stephen Speilberg, Sir Richard Taylor, Kevin Smith, Robert Roriguez, and we made some great inroads. But whenever things got serious – whenever we were pitching some big, ambitious original project that required major industry investment we always came up against the same problem: the age of original content was dying. It didn’t matter how exciting the script was, or how novel the world building – it wasn’t an established franchise. Audiences wouldn’t recognise the name, there was no video-game or best-selling book series to justify a $50m budget.

‘Why don’t you go and write the book – then we can adapt it into a movie’ they would joke. I don’t know how many times I heard that from agents, managers, and development execs.

After a while, it didn’t sound like such a bad idea.

Only trouble was: I didn’t write. I was the one who came up with the stories and the worlds, I produced the projects, built the teams, and directed the films, but not once did I dare to put pen to paper and get involved in the actual words. I didn’t know if I even could. The thought was frankly terrifying.

What started out as a vague ‘fuck you, I will then’ to a hundred smug LA suits, very quickly blossomed into the third love of my life. It turned out that I could do it (longer blog post coming about that). Not just that: I loved to do it. Not just that: I wondered how I had spent so many years existing without doing it. In novel writing I had found a way to finally be free of the endless compromises that necessitate filmmaking – no longer did I have to worry about the budget, or the daylight, or the temperature of the water, or some department having a flap. It was as if someone had skewered my skull with a spout that allowed ideas to pour, undiluted, from my imagination onto the page. And what came out wasn’t a script – not just a blueprint with which we’d go forth and try to make something else – it was the finished product (well not quite – but the fate of that first novel is a long story for another day…).

One great piece of advice I read in my late teens was ‘start by calling yourself a filmmaker’ – it’s a great way to shift your perspective and fortify yourself against fear and imposter syndrome. Now, though, it felt almost like a betrayal of those 20 years to start calling myself a writer (not least of all because it begs the horrifying question ‘what have you written?’). But I couldn’t help it. Something in my DNA had mutated, it wasn’t simply that I was currently enacting the verb to write, I had become the noun writer.

After a while, I started to realise there was a power less tangible, but even greater to the act of novel writing, beyond the lack of compromise. In film, however hard we strove to aim big and compete at the highest possible level, there was always a temptation to bow to the reality that we simply didn’t have the same resources as the big boys. We spent two years making 30 minutes of underwater cinema with less money than Avatar spent on coffee. For what we had, we did great. Only that doesn’t matter to the audience – the ticket price is the same, the cost of their attention is the same – they quite rightly want the best entertainment they can get for their time and money. However hard you try, it’s never possible to completely silence the voice that says ‘well, yeah, we can’t do that though – we haven’t got $200m’ – to let yourself off the hook, to give yourself an excuse (however valid) for not being as good as the very best.

But with a novel? With a novel those stubborn little excuse-goblins that cling in the dark recesses of your mind are burned away by the scorching white-hot light of a blank page staring out of your word-processor at 5am. All you have is a keyboard and a coffee. But guess what, that’s all anyone has.

All that matters is: what are you going to do with it?