Christa Miller's Blog

April 11, 2025

Five Years After My Dystopian Fiction Was Published, I’m Afraid It Might Actually Be Coming True

By Election Day 2016 I was wiped out. It wasn’t just the endless news cycle squawking about Hillary Clinton’s emails or Donald Trump’s worst hot mic moments. Those were bad. But I was also grappling with a much more personal challenge: my first layoff.

It had come as a shock in May, over the phone and one week before scheduled surgery. In the weeks that followed, I took the extended break everyone says you should. I read a lot, lounging in a hammock at the base of the maple tree in my yard. I walked in the woods, also a lot.

Inside, though, I seethed. I had thought this company and team really wanted me there. They’d valued me enough to poach me from my prior company. I’d worked at the new job for nearly a year. Sure, there were disagreements, but nothing I thought we weren’t working through.

Alas, I’d misunderstood that when corporate types talk about how much they value problem-solving and lesson-learning, they have limits and conditions in mind which they assume you know without having to communicate them. I’d also underestimated my own capacity for staying in situations long past their expiration dates.

Internalizing the outcome as purely my problem — corporate life wasn’t for me, I wasn’t compliant enough, I couldn’t fit in, perhaps I was too neurodivergent — I decided I’d go back to self-employment, where I could make my own rules… and my own projects.

I took my sense of powerlessness and displaced anger and suddenly copious time and started writing. The unassuming speculative dystopia I came up with was based on a few things: a murder-mystery idea from years ago. Someone I’d known and loved years before. A setting that had always captivated me for the way its careless summer vibe seemed to hint at a seedier underculture powering its place in the local culture.

I wrote, and a new world took shapeMy fictional world reflected my anger and cynicism about corporate business-at-all-costs, profit-uber-alles approaches. With all of society privatized, my little New Hampshire coastal community became an Epstein Island-like attraction for rich, depraved sociopaths.

Public service had given way to fealty towards metrics. Civil servants had been indentured as corporate drones. Private prisons, as well as underground markets, thrived on the backs of laborers sentenced by AI judges to pay off their “debts” to corporate interests. My characters subsisted off dwindling company scrip and lived in the hulks of capitalist enterprises gone by, even as infrastructure crumbled around them due to climate change-related weather. My speculative fiction twist: empathy, a learnable skill, had been banned outright.

One novella became four, after the first in the series, “Sodom and Gomorrah on a Saturday Night,” was accepted into an anthology published by upstart Running Wild Press. The stories, each titled tongue-in-cheek after other Biblical stories, became more personal. I found myself exploring themes of allyship and intersectionality, post-Ferguson, pre-Floyd.

Though I worried I didn’t have the political science or journalism chops to write a “good enough” thriller a la , I focused on the human stories I was trying to tell, even as my life continued to founder. I was hired at another job, then laid off a second time nearly two years later. My marriage was crumbling.

By 2020, when my collection of four novellas was published in a single volume — Sodom and Gomorrah on a Saturday Night — the first Trump presidency had likewise come to an end.

At this point, I found myself unsure my stories were even relevant anymore. Audience interest in dystopian fiction, at that time the province mostly of young-adult literature and movies, seemed to be on the wane. Worse, the published authors I’d asked for blurbs had all turned me down.

Besides, I found myself so exhausted by all the trauma I was living with that I hardly felt able to promote the book. Deep in survival mode, I focused on getting through the divorce and supporting my kids and maintaining my home.

But as life became more precarious — freelance contracts lost, paychecks slim, the six-of-one-half-a-dozen-of-the-other safety net of a mortgage forbearance and, finally, stable but low-wage work — I felt ever more vulnerable. Election Day 2024 marched toward Inauguration Day 2025, bringing with it a sense of creeping dread.

The dread now is less creeping, more ambientIt’s not that I thought Joe Biden was any kind of second coming of FDR, but after years living in survival mode, I now know the lengths people will go to retain their illusions even in the face of evidence.

It’s just basic positive thinking. You don’t want to invite further hardship by living in anticipatory gloom. Your cognitive behavioral therapist supports this. And you do see glimmers of light in the darkness, like the stable job or the thriving kids or the (re)awakening of old interests.

Like bioluminescent organisms in caves, though, these glimmers can fool you into thinking you’re almost out of the darkness. That you don’t have to fight so hard to ensure your survival, even that you can rest.

That is, if you’re privileged enough to do so.

Those of us living precariously know that positive thinking can turn quickly to self delusion and denial. We need to feel helpful more than hopeful, empowered more than enabled.

Yet these qualities are tall orders. Late capitalism trained us to be hyperindividualistic, reliant on no one but ourselves and our own bootstraps. It is all too easy for precarity to overwhelm us, make it harder to help ourselves, and harder to reach out for help from others.

In these conditions, authoritarians thrive. People who feel disconnected from one another snitch and suspect, focusing on their own survival at others’ expense. This is, perhaps, what the “Mump” plot anticipated when it enacted its dystopian “shock and awe” campaign.

Indeed, the past few weeks have seemed increasingly like the setup to the world I envisioned while processing my personal experiences with corporate fuckery:

The initial suspension of federal funding suggested that perhaps private industry might indeed step in to fund scientific research and development, in its own interests, of course.

Tristan Snell skeeted on Bluesky on March 11, 2025: "They want to cut USPS - so they can own it. They want to cut Amtrak - so they can own it. They want to cut Social Security - so they can force you to use private financial firms more. They want to cut Medicare and the VA - so they can force you to use private healthcare more."

Tristan Snell skeeted on Bluesky on March 11, 2025: "They want to cut USPS - so they can own it. They want to cut Amtrak - so they can own it. They want to cut Social Security - so they can force you to use private financial firms more. They want to cut Medicare and the VA - so they can force you to use private healthcare more."The wholesale layoffs of federal civil servants may likewise be a prelude to privatizing “failed” services like air traffic control and veterans services.

On February 18, 2025, Will Stancil skeeted on Bluesky: "Americans do not understand the incredible crisis consuming all components of their government at once. Thousands of jobs lost, projects on hold, desks unmanned, services stopped, basic safety neglected. Total chaos. Stuff is going to start breaking down, maybe catastrophically." Sallie B responded: "This is intentional. They want to break it to the point where we will accept private corporations coming in to fix it."

On February 18, 2025, Will Stancil skeeted on Bluesky: "Americans do not understand the incredible crisis consuming all components of their government at once. Thousands of jobs lost, projects on hold, desks unmanned, services stopped, basic safety neglected. Total chaos. Stuff is going to start breaking down, maybe catastrophically." Sallie B responded: "This is intentional. They want to break it to the point where we will accept private corporations coming in to fix it."Private industry in the form of Meta announced plans to replace human engineers with artificial intelligence; there’s been talk of automating government, too.

On the other hand, while incarcerated laborers fight wildfires, Trump reversed a ban on private prison contracts — and intends to leave disaster management to states just as climate disasters begin to intensify.

Calls for children to work for their meals prefaced plans to eliminate the Departments of Education and Labor. Likewise, regarding the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), an early suggestion that wildfire victim relief might need to come with conditions.

Speculation, too, suggests a country more like the one I envisioned:

Bluesky’er mblackberry skeeted on March 2, 2025: “White supremacists will fire cops to instead hire private contractors. Those private contractors will allow cops to apply for their old job at a reduced salary with no defined pension benefits. Getting rich is more important than being racist.”

Bluesky’er mblackberry skeeted on March 2, 2025: “White supremacists will fire cops to instead hire private contractors. Those private contractors will allow cops to apply for their old job at a reduced salary with no defined pension benefits. Getting rich is more important than being racist.” On February 14, 2025, Ilana Masad skeeted on Bluesky: "Can't even joke about how my silly little feelings should be illegal because that seems like an entirely possible thing for this government to outlaw"

On February 14, 2025, Ilana Masad skeeted on Bluesky: "Can't even joke about how my silly little feelings should be illegal because that seems like an entirely possible thing for this government to outlaw"I hope I’m wrong, of course. I hope incompetence and vainglory erode from within, and enough voices and resistance undermine from without, all contributing to stopping this hateful and nihilistic regime. But however it happens, we will need one another as never before.

The “as never before” part is what drives the characters in the stories I began writing nearly 10 years ago now. They’re as deeply flawed, privileged in many regards, and uncertain as I find myself when it comes to organizing.

Like me, too, they’ve never felt they fit in, not least because they’ve failed — in some cases very badly — to show up when they were needed.

But crucially, they get over themselves. Where I still have prolific trust issues and social anxiety, the characters I wrote learn from their mistakes. They come together, choosing the actions that help them grow into the better versions of themselves they’d like to be.

They ally with characters more vulnerable than themselves. They show up for one another.

As I write this essay, much of the future is still uncertain. Lawsuits have been filed and protests rallied, even as the gutting and bullying continues. The resistance brings me hope that much as we indeed only have each other, we are all learning and growing likewise.

March 11, 2025

Finding Community and Building Solidarity for Socially Exhausted Introverts*

People are exhausting, or perhaps more accurately, interactions with people are exhausting:

Decoding the nonverbal microexpressions and hand gestures, tones of voice and fidgets and tells.The verbal communication, too: not just the words, but also their sound, the speed, the flow.Putting the two together. Deconstructing them to find the incongruities and discrepancies. Reconstructing them.Deciding if these inputs make a person or group safe or unsafe... during and after every single encounter.Judging them.Not judging them.Showing them you see and hear them.Willing them to see and hear you.Wanting them to have the answers you can't and never have been able to find within yourself.Being disappointed when they don't.Trusting them when they encourage you to find your answers.Being done with them.Missing them and wanting to be around them again.Trying to figure out if they ever wanted to be around you.The contradictions between your conditioning that says they're avoiding you, versus not quite believing the more positive alternatives.The contradictions between your conditioning that says they're just being nice, or want something from you, versus not quite believing you can trust them.Trying to communicate your needs in conversation (like when you absolutely cannot tolerate eye contact) as well as your other needs while balancing theirs while not putting theirs ahead of yours while they may not be able to put yours ahead of theirs either.Among these overwhelming observations are the small moments that tell you whether and how much you have anything in common. If you're paying attention, you find the keys to all your future interactions:

Share a love for nature? You might be able to volunteer together for river cleanups or community gardening.You have neurodivergent children? Arrange sensory-friendly playdates. Reschedule them when someone – you, your child – is having a bad day.The faith you doubt? Just decide to gather, two or three, in the name of friendship.Agree your workplace could be compensating or treating you better? Find out if a local union has introvert-friendly tasks you can contribute to while getting support.Enjoy the same kinds of music and/or movies? Find where buskers play, listen to them, tip them (hey, it's live music without the crowds).Sometimes, of course, it won't work out. It can't.

You think you share values, but you find you're expected to keep giving long past the point of depletion. You're not even sure they see your needs as valid relative to theirs.They already have enough friends, and despite the things in common, don't seem eager to make room for one more.They're more interested in people they can bring into their orbit, than they are in dancing.Spending time around them makes you feel tired or confused or stressed or even sick in ways you may not be able to explain.Local opportunities are few and far between, and you both struggle to make room for each other around work and life.And then you have to start over, and that's exhausting too, especially when you fear you're running out of time, that the Universe is not so much benevolent as indifferent, much less that it will provide what you need when you need it.

But the alternatives are inertia and stagnancy, and you realize -- even as you stop and sit and rest a bit, or a while -- you don't want those either, and you find a way to keep going.

Maybe at some point, you even find people and activities who energize you, and that's the most important social cue of all for introverts: those who make you want to socialize.

*The kind of "introversion" I've described here also describes neurodiversity, autism in particular, but also CPTSD. I've deliberately left out "find a therapist" because I know it's often inaccessible and not necessarily high quality, but therapy can be a good option for introverts.

March 4, 2025

How to Heal When Life Feels Like the Environment That Harmed You

There's a popular saying among therapy and self-help circles: "You can't heal in the same environment that hurt you." It's a rallying cry for those of us hurting to encourage us to "go no contact" with the toxic family or friends, divorce the abusive or neglectful spouse, find the new job.

But what happens when you do those things, only to find things don't get better?

Friends remain distant, or you lose them altogether and can't seem to make new ones. The new managers still focus on results. Money remains tight.

No one sees you. No one cares that you escaped. There's almost an unspoken expectation that now that you're out, you should be better.

Except you're not. You find yourself questioning every new person and environment. What are they hiding? When will their true colors come out? You find yourself shrinking, once more trying not to be noticed (a flight / freeze / fawn response) or else, becoming combative and challenging (the fight response you weren't allowed before).

You give people chances. They let you down. It's harder for you to give them the benefit of the doubt in their own flaws and life stresses. You remember all the times you've ever given someone the benefit of the doubt and gotten screwed (again).

We remember negative experiences more strongly and for longer than we do positive ones, which in turn, can make our gratitude and mindfulness practices feel hollow. We start to assume we can't "do life." We retreat.

So how can we form and maintain communities?In "How to Be a Fighter When You Feel Like a Punching Bag," writer and organizer Kelly Hayes writes about agency, linking to a piece by Elise Granata that includes information on what agency might look like within communal spaces:

A volunteer finds their onboarding confusing and makes a handbook so others can more easily navigate their own journeys.

An attendee sees a bottleneck happening at the event’s doors and jumps in to help folks navigate.

An artist wants to collaborate with others who share their identity or lived experience and curates a showcase of bands or visual artists like them.

For those of us struggling to identify what "community" looks like when you're just coming out of isolation, justice advocate Mia Mingus offered "Pods for Our Current Moment," "a few or more people [who] can help in the interim and especially in the years to come. A pod is made up of the people that you would turn to for support. You can have as many pods as you like and you can be part of as many pods as you have the capacity for."

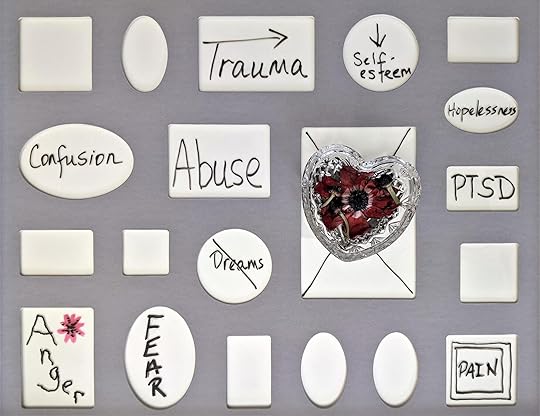

These ideas are incredibly valuable, and yet, as I wrote in a comment on Hayes' piece: "...my experience living with CPTSD has really, really screwed up my ability to discern whether my nervous system is only projecting onto others, or alerting me to very real dynamics I've already escaped."

At the same time that my own sense of agency is encouraged to flourish in local civil service, I've found that the two years I spent in therapy (back when I could afford it) really didn't heal as much as I hoped it would when I started.

Of course, therapy has many limits. But it only takes one triggering to feel like all that cognitive behavioral stuff is just pretty words, and you really are as broken and deficient as you were conditioned to believe.

As I commented further to Hayes:

"A thing I've noticed in our society is how eager we are to tell people to go to therapy, assuming it will teach them everything they need to know about boundaries and self-trust they need to be "fixed" and thus able to be part of our communities. We do this because of our own limited capacity, of course. But in my experience, it tends to alienate those of us who were never sure to begin with that we were reading social rules correctly. I wonder how community leaders and members might work towards addressing these kinds of issues?"Finding community requires openness and trust

In my workplace, everyone has suffered some kind of trauma: poverty, domestic abuse, addiction. By nothing short of a miracle, most of the women there have been able to integrate their traumas. It's part of them, but it doesn't run them. They set boundaries for appropriate behavior that keeps the whole place running, but they make themselves available to listen and care.

I didn't go looking for them, though. No one had told me to apply because this place was so great, for example. It was the result of a lot of trial and error.

First there were the misfires. The community groups I joined to help clean up local riverbanks and mobilize for local labor and tell local stories all offered people who were polite but not especially eager to form friendships, or else open to friendship but not equipped to deal with my messy feelings or chaotic thinking.

Then came the long period of isolation. In its own way, it was the antidote to my codependent tendency to rely on others to have all the answers. I didn't trust myself enough to see the answers within me, and I certainly didn't believe I could fix myself. Being isolated protected me, but only to a point.

Because at the time I was trying to heal, I was also running out of money. I took an hourly job to help pay the bills when writing wasn't going so well. That led to an opportunity to train upward into a different role with more responsibility (and more pay with more hours).

I found myself able to act with agency and uncover skills I'd forgotten I had. I gained trust and was told I was a "great fit."

But even as I developed these bonds, I knew the true test was going to be their tolerance for me when I fell.

I often say that opportunity -- that community -- was the literal answer to a prayer. I'm not religious, but I was raised that way, and I still pray, even though it feels like I have to work harder than ever before to see and trust the answers in front of me.

Those answers include the coworkers who, again totally by accident, have seen the worst parts of me and are still willing to abide my presence; for whom "professionalism" is a reasonable boundary rather than a box into which to shove me and shelve me, and a foundation to develop the strengths they know I have.

This is what I think Hayes and Granata and Mingus are writing about. The communities we think should be obviously welcoming aren't always, and won't necessarily give us the sense of connection we crave. But as Granata wrote:

"If we use agency as a prism to assess our daily activities, we might discover that it is not just about having enough information, trying enough toolkits, browsing or scrolling about it; it is about cultivating our own capacity to act.

"It is about rushing towards the sources that stoke a sense of agency in us, so that we may tap into our own power and build things with other people as much as we dream about it."

Regaining our sense of agency is another way of saying regaining the sense of power we lost in the environment(s) that harmed us. Our triggers show us where we feel powerless. Healing them starts with believing that we do still have power, so that we can tap it and build on it.

February 5, 2025

Asking for Help When You Don’t Conform to Social Expectations

Content warning for transphobia and misogyny.

At the gas station recently, my coworker noticed a young woman, dressed in a miniskirt, struggling to replace the vacuum hose atop its rack. My coworker, a red-blooded (and red-hatted) American male, approached her to ask if she needed help.

She spun around, and all he saw were masculine facial features. He (said he) apologized for scaring her, and then he took his scorn and disgust and left her to struggle alone.

I won’t repeat his rationalizations. I’m sure his reasoning went more like: he saw a chance to get himself laid, and as soon as he realized that chance didn’t fit his expectations, that person was on their own.

Having been accosted by strange angry men in parking lots, I’m sure that trans woman was scared speechless. Likely, she would have been even if decency in the form of Kamala Harris had won the election.

Here’s why that matters: because men like these, who seem prepared to use their physical strength for you, can easily turn it against you.

Often, we never know the reasons why they flip the switch. They just decide we deserve it.

And that affects a whole lot more of us than trans people alone.

What expectations of conformity do to our sense of communityMy amygdala remembered this, even as the rest of my brain struggled to find the right words to convey to my coworker that he could’ve just helped her out because that’s what good humans do. That her transness wasn’t as much of a threat to him as his muscles and height were to her. That I wondered what about her and her identity could possibly be so threatening to him.

While I was still trying to get the words out in a way that would maintain my own sense of safety, he left the room.

Men like him aren’t interested in dialogue, after all. They only want to drop their payload and leave others to sort the wreckage they leave behind.

I felt for that trans woman, though, beyond just the immediate threat my coworker presented. I also know intimately what it’s like to ask for help, but not receive it because you don’t conform to the ways other people expect women to look and act.

You’re too assertive about asking — or not assertive enough. You should ask humbly, but not in a way that sounds manipulative. You should be prepared to reciprocate. You should receive without feeling compelled to give back. You should be responsible with what you’re given. You shouldn’t keep asking.

Confused? I have been. ADHD and CPTSD (and maybe a side of autism) cause me to take such advice literally, and to try to reconcile the conflicts they presented through sheer force of will and logic.

Ultimately, though, all these conflicts led to was shutdown, which I suspect was the point. People don’t really want other people to ask them for help.

The problem is that when you don’t ask — when you conform to the ultimate expectation of total, compliant silence — you give tacit permission for people to stay in the comfortable, convenient bubbles of their own beliefs.

What if that trans woman had felt unthreatened enough to take my coworker up on his offer of help? He’d have had to confront the idea that he might not be as helpful as he likes to believe. That he only helps women in order to extract something from them.

That maybe he’s not actually all that great a guy.

Confronting our conformist illusions breaks down barriersThese are the kinds of illusions we all maintain about ourselves. Finding out that we might not be the hero in someone else’s story — that we might be the villain or even the bystander — isn’t very pleasant. But it’s the start of the growth we are all, as humans, called to go through.

In my own story, for example, I’m a single mom struggling just to make ends meet. Both in my marriage and as a professional, I stood on principle and got left holding a very big, very heavy bag. I want help holding it, but everyone seems to think I’m strong enough to manage on my own.

In their stories, they’re:

Delivering the dose of tough love they think I need to stave off denial. But “Just get a job” only goes so far when the work you had burned you out, and the only work you can find doesn’t offer a living wage.Shoring up my strength with pep talks. But “Just work multiple jobs” leave you with little time or energy to “manage” investments or property — if you weren’t trying to use all available wages to maintain a home and the vehicle you use to get to work.Offering practical, friendly, even loving advice to a somewhat scatterbrained friend. But “Just budget” is cruel advice in a time of greedflation outpacing wages and billionaires ripping off the U.S. Treasury. Most of us know we’re one emergency away from losing everything.Giving me the permission they think I won’t give myself. But “Just apply for assistance” fails to recognize families who hover so close to the poverty line that sometimes wages render them ineligible for assistance, and you have to hit the application timing just right, and your timing may not sync with the shifts you’re working.Reminding me that help is available, even if it’s not from them. But “Just ask family” assumes family are willing to help, not struggling with their own expenses, and aren’t judging you for the same failures everyone else does. It also assumes you live close enough to rely on, say, housing or transportation, which come with plenty of their own conditions.Again with the tough love. But “Put your ego aside” assumes you haven’t already, over and over, to the point where you’re not sure you even recognize yourself anymore.No wonder trans people choose living as themselves. Because all those “just” expectations really are, are demands for us to conform to the social norms we think society can’t function without:

The boxes we put people in that say that women are bad with money and real men do things themselves, that women need men to take care of them and men need women to take care of — and gender nonconforming people neither need nor are needed by anyone else.

Curiosity, not control, engenders (pun intended) community

Curiosity, not control, engenders (pun intended) communityTransgender rights are human rights because — surprise! — not even cisgender white men totally conform to the social expectations people have for them. We see this in their insecurity and control issues: they know they can’t hold themselves to such rigid social expectations.

If they could, then the phrase “toxic masculinity” wouldn’t exist — much less frighten and hurt so many people.

I’m calling on them, and all of us, to let go of the control. To get curious about why we expect things of ourselves as well as others. And to confront inconvenient realities that coexist.

Drag Queen Story Hour is an affront to children’s innocence? OK, then make sure you also protest the rampant sexual abuse in houses of worship.

Single moms should be more responsible with the money they get? OK, then call for affordable childcare and better mental health counseling for couples and for god’s sake, more equitable pay and an end to price gouging and a dozen other things I’m not thinking of.

For myself, part of allyship is to hold space for myself as a survivor of trauma who still struggles to speak up and confront people who I perceive could overpower me. Just because my experiences allow me to empathize with my trans sisters doesn’t mean my amygdala got the memo. She and I still have work to do.

In the meantime, I have my online voice, as well as the voice that’s learning to ask for help when I need it. I hope you’ll join, at whatever level you can, to support me in sharing my learnings.

January 31, 2025

To Protect Our Children, We First Need to Heal Ourselves

Note: this essay is the last of a 5-part series I wrote over a period of years prior to Election Day 2024. Part 1 described my personal experiences being groomed and the factors that continue to allow it to happen. Part 2 went into the role of generational trauma in child and intimate partner abuse. Part 3 described the failures of the "stranger danger" education I grew up with. Part 4 considered how our "hero" narratives keep us from solving the problem of (or healing from) child abuse. Here, I offer some thoughts on how healing our own traumas could help us protect younger generations.

If I were to sum up my experiences with “not that bad” abuse, I would say this: I’ve never talked about it, much less reported it, because I thought that not only was it not abuse, but also that it was a fact of life.

I was conditioned to set a low bar of expectations for the men in my life. The bar for strangers I encountered wasn’t much lower. Those who didn’t beat or rape me, in other words, were potential husband material, especially if they “put up with” me.

In fact, the term “coercive control” was only coined more than 20 years after I was born (during the same decade women finally were able to get their own credit cards) and a little more than a decade after all 50 U.S. states finally recognized marital rape as a crime.

Even still, the concept of coercive control would only begin to enter public awareness more than a decade after its naming. Society still, in my opinion, has a limited grasp of what coercive control can entail, which also limits people’s grasp of what grooming can entail.

This is what I believe a lot of adults misunderstand about “not that bad” abuse: its profound repercussions throughout the rest of our lives.

Such limited awareness may in part be willful. Remaining ignorant means people don’t have to do the hard work to heal their own assumptions — which may necessarily mean facing the same dynamics within their own circles, among people they love.

Indeed, in my own experience, undermining the social expectations I learned has been far from easy. Raising my two Gen Z boys, I myself often found it easier to address issues they had with peers and strangers than with other adults in their lives.

For example, it was easy to:

Not hire babysitters we didn’t know very well, including who else was in their lives.Remind our sons, when they were little, that they had the agency to ask a friend to remove a video from her Snapchat they hadn’t consented to her posting.Leave the box unchecked on school and extracurricular permission slips that allowed posting of their photos and videos to organizations’ social media pages.Warn them when someone they met online offered, unsolicited, to send them a gaming computer.Counsel them on things their favorite YouTubers did and said in order to attract views, likes, and subscribers.Those were the “stranger” examples, though — the clear-cut challenges. Much more nuanced and thus harder to navigate were the inner-circle conflicts with family members, friends, and coworkers. Were they matters that required cutting ties — the default I learned as a child moving states and schools — or only projections of my past that I needed to work through, the way adults with more stable modeling had learned?

These situations were where I fumbled, as I suspect we all do. In part, that was because I was playing out the same dynamics in my work life that my sons were at school. Wrapped up as I was in survival mode at work — navigating office politics as well as a workload that drove me to burn out more than once — I was only partly emotionally available to my sons.

That was how I missed the effect of a teacher who didn’t quite single out one son for shame and ridicule; but managed, nonetheless, to make him feel like he couldn’t get anything right.

In fact, I found it easier to tell him he’d encounter bosses like her — again, as I was finding in the workplace — than it was to try to switch classrooms halfway through the year.

Likewise, I found myself surprised into speechlessness when my otherwise always-confident younger son talked about the trauma he felt witnessing student-on-student violence that didn’t trigger a school lockdown.

This is what I believe a lot of adults misunderstand about “not that bad” abuse: its profound repercussions throughout the rest of our lives.

It was then that I realized that my approach — chaperoning some field trips along the way, aiming for experiences rather than souvenirs, and listening deeply when my sons talked about the games and YouTube channels they loved that didn’t interest me — only went so far.

The fact was, memory-making wasn't a stand-in for the kind of emotional intimacy kids really need.

Our fears of the worst outcomes are rooted in the knowledge that many things are beyond our control. But by fearing too much of the future, we box ourselves into a far more restricted present than is real.

As I knew from experience, kids who don’t feel they can be fully themselves around peers or adults want to prove to everyone, themselves included, that they, too, can be “special” or “chosen”: the right kind of “other,” the kind that is lovable.

In other words, I realized that perhaps we hadn’t created enough of the kind of environment I felt, based on my experiences, was so important: the creation of a loving safe space for my sons to tell me anything.

Thus it is only in the last few years, as my sons have matured to young adulthood, that we’ve been able to talk about, say, all the nuances of a friend’s challenges living with a drug-addicted family member, or befriending a Syrian refugee teen only recently arrived in the U.S., or for that matter, their feelings around my divorce from their father.

Those conversations are only possible because I finally began to do the work to learn to listen to myself, and why I believe now that a more impactful and sustainable way to deal with child abuse — not only to mitigate it, but also prevent it; not only for the worst cases, but also those we deem “not that bad” — is to invest in healing it.

The rub is that “healing” is more complicated than it seems on the surface. As we learned during the COVID-19 pandemic, our culture is not set up to accommodate the copious time required to sit and feel and process our emotions.

But it’s difficult, if not impossible, to do this feeling work and remain productive; to pay the bills and maintain the home and complete the work. That’s likely why instead, we were asked to double down and work around the inconvenience.

Perhaps not coincidentally, even as official child abuse reports plunged during those years, other reports surged.

Moreover, every person’s healing process is different — differently intense, and differently timed — making it inherently less controllable than outcomes. Healing needs to happen in its own time, in its own way, on its own terms.

Perhaps that’s why the idea of “rescue” is so alluring: it has a defined outcome — even if it fails. Moreover, it gives the rescuer a sense of power in an otherwise uncontrollable situation. Healing, in contrast, takes that power out of “rescuer” hands and places it squarely back where it belongs: in survivors’.

Healing our beliefs about “not that bad” abuseBoth as a young person in my family of origin and later, as I made my way into the corporate workforce, I heard phrases like: “That’s just the way they are,” or “It’s better to catch flies with honey,” or “You just need to grow a thicker skin,” or “They had a hard life, you need to learn to bend a little.”

This is the nature of grooming. Adults accept it because on some level we believe it will elevate us. We’ll get the promotion or the business if we go along, complicit in pushing our own boundaries in the name of “getting out of our comfort zone.”

We put on our “big girl panties,” and put aside our misgivings with the bully coworker or manager or client. We let them push our boundaries in the name of relationship-building and customer service.

If we were to stand up for ourselves, we might be shunned: “quiet fired,” if not outright terminated, or for those of us self-employed, facing canceled contracts and bids awarded to competitors.

These forms of rejection appear to threaten our survival: how will we eat and maintain our homes if we can’t earn the money we need to do so?

Our fears of the worst outcomes are rooted in the knowledge that many things are beyond our control. But by fearing too much of the future, we box ourselves into a far more restricted present than is real.

The limited choices we think we have then lead us to become a little too accepting. We can start to take on too many things that we can control… to avoid thinking about the things we can’t.

Convincing ourselves that we’re “character building” and modeling the right way to our children, we keep stuffing our intuitions. We may even convince ourselves that we love what we do and couldn’t imagine doing anything else.

Remedy: Work on noticing what you say to other people — coworkers, kids, partners, friends — when they come to you with complicated feelings. Work on noticing what you say to yourself, too, as well as how your words make you feel: peaceful, or more agitated?

Healing generational power and control dynamicsFor as long as I can remember, adults have pointed to research about kids’ brain development, focusing on impulsiveness rather than intuition, poor decisions rather than developing discernment, to “prove” that “adults know better.”

Too much adolescent brain research focuses on what isn’t there, rather than on what is. Kids may not have all the neural pathways they need to make rational decisions. But all that means is that those pathways won’t develop without practice.

As with every generation, today’s children are experiencing life much differently than we did. They have different technology, cultural norms, social expectations etc.

I try to remind them that intuition is not just about situations that feel all wrong, but also about the warning signs that come before the situations.

To meet these challenges, they have to be able to speak up on their own behalf (as developmentally appropriate) and enter into a dialogue. Otherwise, "protecting" them is just another way of communicating they have no agency.

Counteracting this type of poor parenting in 38 U.S. states is Erin’s Law education, a good starting attempt at encouraging awareness, agency, consent, and bodily autonomy in all kinds of relationships.

That said, as of June 2024, 12 states still had not enacted Erin’s Law legislation. Furthermore, in my experience as a survivor of grooming, these types of programs are too little, too late.

By middle school, a child may have spent years experiencing and/or witnessing unhealthy dynamics. Their self image is already on shaky ground due to the onset of puberty along with social pressures.

If they believe they’re the problem, then the line between enthusiastic consent and mere compliance is blurred. It’s possible, in other words, to believe you want something because the person you care about or admire wants it. Including, and especially, your own parents.

That’s what makes it all the more important to heal the (sometimes hyper)vigilance many of us develop in response to abuse.

For example, my own trust issues could end up isolating my kids from the other adults whose perspectives and guidance they critically need as they grow towards their own adulthoods.

Thus most of what I talk to my sons — and their girlfriends — about these days is what I wish more adults had talked to me about 30 years ago: the need to honor your own gut feelings.

I try to remind them that intuition is not just about situations that feel all wrong, but also about the warning signs that come before the situations. For instance: that sense of feeling put off by a comment right before your brain tells you “they were just joking.”

That they may see those signs even among people they love and trust. That their intuition is the same no matter what. That two things can be true: they can love a person, but no longer be able to trust them. And that their intuitions can guide them along the right path, because life cannot be all avoidance.

Being seen and respected for who they are as people — integrated as individuals, rather than forced to carve away pieces of self in the name of conformity — is what gives kids the self-confidence and assurance to observe and reject the false intimacy promised by grooming.

In turn, healthy emotional intimacy encourages community: a whole network of people who all see and respect one another for who they are, who will band together to protect those they love.

But it’s our avoidance that provides the scaffolding for the structures in which predators thrive. Thus to heal, really heal, we need different structures; ones that hold us accountable for maintaining real safety, not just its illusion, within our communities.

Remedy: Notice your tendency to believe the young people you know — even toddlers! — are too naive to know what they experience and how they feel about it. Be self-aware enough to recognize, and communicate, when your beliefs drive your advice. For example:

Do we project adult assumptions and interpretations onto children’s behavior when we say things like "she asked for it"?Do we experience disempowerment at work and with our aging parents, to the extent we push it downhill by disempowering our children?Is it harder to spot "grooming" when so much manipulation has become normalized in adult dating?Asking these and similar questions requires us to get past a “protection” mindset that keeps us from looking at our kids as equal partners in their own safety.

In turn, making these questions part of our conversations with our kids helps everyone to trust that our inexperienced kids can and will carry our lessons into their impulsive, reactive teenage years — and that they’ll be able to make good choices when we aren’t around to watch over them.

Healing our “stranger danger” conditioningEveryone we meet starts out as a stranger. Healthy adults know that over time, people’s actions show us whether to trust or not trust them.

That’s the rub. Unhealthy adults, who themselves cannot be trusted, raise unhealthy children who learn that unhealthy behavior is “normal.” Attachment issues compound the problem, with children and adults both attaching to strangers far sooner than is safe or healthy to do so.

In my experience with child predators — not just the three from my teen years but also one or two I encountered as an adult — they really do seem to believe they're entering into a "relationship." Psychologists call this a “cognitive distortion.”

Other cognitive distortions include inferring sexual intent from innocent activities: a child sucking a lollipop or injured finger, for example, or in an even grayer area, a teen beginning to experiment with sexual power – “flirting” – without necessarily understanding where or how far it might lead, or the ramifications of their actions.

(In this latter example, “she asked for it” might appear to be valid, as might “I was following their lead” or “I was just offering guidance.” These excuses, however, come back to poor boundaries and an adult’s choice to prioritize their own baser biological urges over a child’s humanity.)

The fact is, child predators are people who learned to equate love with manipulation, power, and control, much like many of their targets did. When they offend, they’re reinforcing messages the victim has likely already received. Their connections are based on shame, not love.

Remedy: Take a hard look at all the influences in kids’ lives, not in general terms, but in terms of the level of access and influence they have over our kids, and the extent to which we trust them to do so.

This part is tough because it means potentially undermining the trust we all want to feel in human connections. Again, though, predatory adults understand this desire to trust. That’s how they’re able to twist it so effectively.

As a society, then, we need to be more vigilant: more observant, more communicative, more caring. It’s not “none of our business” and it doesn’t have to be a big deal; sometimes a “Hey, are you OK?” is all that’s needed.

(Yes, the same conditions that make a teen vulnerable to abuse — a quiet private space, a listening ear — are the ones needed for them to feel safe enough to disclose if something is happening to them. That’s why it’s so crucial for kids to know how to be clear about boundaries.)

We can also help our kids by looking out for — and showing them to look out for — the behaviors that might trigger their intuitive red flags. One example is the difference between reciprocity in a healthy relationship, and transactionalism in an unhealthy one. Another example is intermittent reinforcement.

Finally, we can set guidelines around extracurricular activities, even “safe” ones, especially those where the power differential between adults and children is exacerbated — as it is in Explorer programs — by weaponry and/or social authority.

Healing our hero narrativesAs important as it is for us to have people to look up to and emulate towards growing into our best selves, identifying heroes can also come as a result of feeling disempowered or out of control.

If “rescue” and “abuse” are opposite sides of the same coin, then so are “heroes” and “predators.” We scapegoat those who remind us of the negative traits that (we think) cause our problems, while business, political, and military leaders who (we think) solve our problems go up on pedestals.

Put another way, when the monsters are revealed to be hiding in plain sight, we tend to think it reflects on us. Somewhere, we think, we missed the signs. Somehow, we failed to notice — much less protect.

“Protectors” like police, prosecutors, and even predator catchers go up on pedestals. The monsters, meanwhile, are cast out, a stand-in for everyone who’s ever wielded power over us. Lock child abusers away, we think, and we retain some of our own power, so we can “move on” with our lives..

The alternative is that we scapegoat the child reporting the crime, especially when they challenge our illusions of our safety. Not only do they “not know any better,” we conclude, we might also project an outsize sense of the power they have in our lives.

Perhaps that’s part of why we turn a blind eye to exploitation dynamics because that’s just the world we live in and our kids need to learn how to go along to get along.

However, just as casting out a scapegoat puts them out of sight and mind, placing heroes too high above us can put them beyond our vision — and in some cases, our reach, as high profile child abuse cases indicate.

Remedy: Accepting these uncomfortable concepts might then encourage us to consider the institutions we tend to want to protect at the expense of children’s vulnerability. Child predators thrive in families, schools, churches, healthcare facilities, and other trusted places because of how badly we want to avoid admitting that “other” exists among us.

But it’s our avoidance that provides the scaffolding for the structures in which predators thrive. Thus to heal, really heal, we need different structures; ones that hold us accountable for maintaining real safety, not just its illusion, within our communities.

So it’s on us, too, to recognize when we’re part of the problem. We may not earn ribbons or medals, much less a full “fruit salad” for our efforts. But we can take comfort in creating a legacy of healthy, unbroken adults who can live up to their potential in contributing to society the way they were meant to.

Support more work like this series: subscribe to a paid tier, leave me a tip , and/or share this article!

How American Hero Narratives Keep Us From Solving Social Crises — or Healing

Note: this essay is Part 4 of a 5-part series I wrote over a period of years prior to Election Day 2024. In Part 1 , I described my personal experiences being groomed and the factors that continue to allow it to happen. Part 2 went into the role of generational trauma in child and intimate partner abuse. Part 3 described the failures of the "stranger danger" education I grew up with. Here, I consider how our "hero" narratives keep us from solving the problem of (or healing from) child abuse. Finally, Part 5 offers some thoughts on how healing our own traumas could help us protect younger generations.

It is perhaps a tragic irony that even as our attention has shifted from “stranger danger” to the dangers of people children already know and trust, victims of child abuse must rely on strangers for justice.

Further ironic is that most of these professionals have built their careers within structures designed to address stranger danger. As a result, the criminal justice and family court systems reflect society’s failures to address the calls coming from inside the house. As professor Gillian Harkins wrote in her book Virtual Pedophilia:

“[T]he focus on pedophilia is not so much paranoia about sexual harm that directs attention away from apparently more legitimate structural social problems … as a minimization and denial of sexual harm as a structural social problem tethered to broader systems.”Is the system functioning as intended?

In the aftermath of any given incident, a veritable gauntlet forms to gather and preserve key evidence: police detectives, forensic interviewers, victim advocates, medical staff, and lawyers among others comprising multidisciplinary teams that coordinate an investigation and eventual prosecution.

This coordination, and the considerable training that goes with it, is necessary not just to collect and preserve as much evidence as possible — including memories — but also to do so in a way that removes as much emotion as possible from an otherwise highly charged incident.

This professional approach to child abuse cases is designed to limit the chance of “vigilante justice.” However, the development of such professionals recreates the dynamic of adults who “know better” than victims; whose emphasis on evidence may disproportionately focus on tactics, rather than less concrete psychosocial behaviors like grooming; and who may not be able to see their own blind spots.

The professionals I’ve worked with over time would doubtless characterize this view as unfair. On LinkedIn, their posts try to communicate that clearly something must be working:

Recaps of testimony delivered on Capitol Hill and in criminal hearings.Personal accounts of children removed from abusive homes and other situations.Recountings of burnout and vicarious trauma.Resharing of inspirational messages from survivors turned advocates.Not everyone agrees, however, that these efforts or results are consistent or widely distributed enough. Witness the rise of online “predator catcher” vigilante groups across the United States. Something may be working, but everything is not.

Have we overemphasized “rescue”?As a survivor who fell through the system’s cracks not just once, but multiple times, it’s hard not to observe that much of the discourse focuses on “rescuing” children from predators’ clutches, or “protecting” them from falling into those clutches to begin with.

In fact, it takes time — often years — for cases to wend their way through criminal courts. Although trauma-informed training along with plea bargaining practices can help reduce the chance of revictimization during trial, victims are nonetheless often disappointed by outcomes.

So are the professionals who have dedicated careers and lives to child safety. They know there’s only so much they can do; only so much that can capture and keep their attention at one time. Naturally, as a result, their focus tends to coalesce around the very worst — a bar that seems to sink lower each news cycle, apparently demanding proportionally strong responses.

Responders can begin to think of their efforts as nothing short of heroic, the natural progression of a “sheepdog” mindset that sets law enforcement, in particular, apart from the rest of the population.

This mindset is a kinder form of “us vs. them” mentality, arguably a byproduct of American law enforcement’s origins from slave patrols. Even so, the idea of “sheepdogs” guarding “sheeple” recalls the words of one young officer, when I first joined the Explorers: “The public is basically dumb.”

Her contempt may have been at least part of the reason neither she, nor any other officers, noticed the grooming happening right under their noses. There were other factors, too:

I was nearly “of age.”They had lives and dramas of their own to contend with.They needed to be able to trust one of their own.The “weak oversight” cited by both the New York Times and the Marshall Project in their stories about abuses in the JROTC and Explorer programs.At the time I was attending summer encampments, the U.S. Navy’s 1991 Tailhook scandal was still fresh in most active duty personnel’s minds. More female instructors, or at least a medic who would have been able to address “girl problems” like menstrual cramps and harassment, might have at least curbed some of the more egregious boundary oversteps.

Then again, it might not. Another woman, like the cynical officer, could as easily have sided with her male counterparts’ (especially superior officers’) decision-making.

It’s also hard for me to avoid the sense that I was, again, the “weird kid.” Once again, I didn’t fit neatly into any herd — not among the “sheeple,” nor the pack of sheepdogs I was among.

At that point, it’s difficult for me to view “sheepdog” mentality as anything but a way to fight a pervasive sense of powerlessness: the inability to make as much difference as we’d like in the world.

The underpinnings of modern hero narrativesHeroism is as old as the ancient Greeks. In the United States, modern-day heroism equates with superheroes — a subgenre that’s been part of the national discourse for years, since the late 1930s, when Superman and Batman were introduced.

Of course, those years fell between the Great Depression and World War II, another period of time in which Americans felt powerless. Thus it’s perhaps no coincidence that post-9/11, five years after “Mission Accomplished” was declared and two years after Saddam Hussein’s execution, Marvel Studios introduced us to Iron Man: the first of dozens of films that would generate more than $29.8 billion at the global box office, making the MCU the highest-grossing film franchise of all time.

In 2015, ten films into the franchise — back when it was still easy to “catch up” with the MCU — President Obama signed the HERO Act into law. The act formalized and endorsed the Human Exploitation Rescue Operation (HERO) Child-Rescue Corps Program, described by the program’s website as “a paid federal internship that recruits and trains veterans as computer forensic analysts to combat child exploitation.”

Administered by ICE HSI's Cyber Crimes Center, the HERO program relies specifically on “wounded, ill or injured (VA/DoD Disability rating) veterans and transitioning service members.” A lot of people, veteran and non-veteran alike, have touted the HERO program as a way to give some meaning back to veterans whose disability or transition back to civilian life has left them struggling with their sense of identity.

Around the same time, though, another troubling trend was emerging: people exposed to child sexual abuse material were experiencing profound vicarious trauma.

On the “tame” side of the scale were those who, for example, turned the sound off on their computers so they wouldn’t experience the full horror of what those children were going through. On the other end of the scale were those who experienced mental health crises, including suicide.

These outcomes were reflected in additional Marvel productions that came out around the same time:

2014’s Guardians of the Galaxy depicted a ragtag bunch of deeply traumatized antiheroes who, somehow, managed to band together and use their coping mechanisms to defeat a tyrant.The following year, Jessica Jones hit Netflix, dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from the abusive relationship she survived.Jessica introduced her audience to Luke Cage, whose own 2016 series would explore themes around the traumas of racism and sexual abuse.As validating and even cathartic as these productions were, they did nothing to address the ongoing mental health challenges of everyday “heroes” in the first responder community. Even aside from all the excessive-force complaints, domestic and intimate partner violence rates are higher among law enforcement than among the “sheeple.” There is the substance abuse, and the suicide rate:

“Four suspected suicides in the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Office highlight a problem affecting agencies across the country,” read the deck beneath The Marshall Project’s headline: “Four Suicides in L.A. and the Mental Health Problem in Law Enforcement.”

“...the personality traits of people who are typically drawn to law enforcement jobs are a strong factor in the suicide problem in U.S. police departments,” the article went on to say. “There’s a macho culture among many of the nation’s nearly 1 million sworn officers…. Former members of the military, people with thrill-seeking personalities, and competitive, hard-charging temperaments round out the profile…. Some military veterans, especially those who have been in combat, come to law enforcement with trauma…. Other aspects of the typical officer’s personality profile are also consistent with people more likely to bury emotional wounds and view seeking mental health treatment as a sign of weakness.”The dark side of hero worship

I’m going to go out on a limb and say I’m not the only person thinking this way. The creators of the comic book series and TV show “The Boys” are very plain in their critique of modern-day hero culture.

In that fictional world, super-anti-heroes do terrible things in the name of maintaining their image as well as their ratings. This isn’t so much that they’re under tremendous pressure to deliver on what the public expect will pay money to see, as that they themselves are being exploited — by the very powers that created them.

In real life, the popular television show To Catch a Predator ended after Louis “Bill” Conradt Jr., chief felony assistant district attorney for Rockwall County, Texas, killed himself as police tried to serve him with an arrest warrant alleging he himself had solicited sex with a minor.

Nearly two decades later, “hero” organization Operation Underground Railroad suffered its own scandal when founder and chief executive officer Tim Ballard resigned. Ballard had been under investigation for claims he coerced seven women to act as “wives” on overseas missions.

In the same timeframe, Ashton Kutcher likewise stepped down from the anti-child-sex-abuse nonprofit he had co-founded, the Thorn Foundation, following backlash for his support of convicted rapist Danny Masterson.

In most cases, of course, people who do bad things aren’t bad people. Those who want to rescue children, in particular, can be thought of as true believers adhering to Joseph Campbell’s definition of a hero: “someone who has given his or her life to something bigger than oneself."

But that can create a massive blind spot in our worldview, which is that a world that increasingly feels out of control inspires people to seek a sense of purpose or perhaps more accurately, a sense of control.

It’s perhaps this goal that’s behind another, less inspirational kind of LinkedIn posts: those that exhort followers and connections to “step up” and “be the change” — by way of engaging in subtle shaming.

These posts invoke the image of “bystander effect,” the ghosts of movie-set extras either rescued from, standing agape at, or dying in villain-triggered catastrophes.

It’s true that any effort at all “invites more people into the conversation, elevates awareness, and, most importantly, eases suffering in the only time any of us truly have, which is now,” as one of the more positive posts put it.

Indeed, the best of these posts encourage people to recognize our own power to break free from illusions.

For example, understanding that it isn’t possible to prosecute all cases, society has found other avenues. People have founded nonprofits and introduced legislation, shamed social-media CEOs and lobbied to change terminology and terms of service, hosted and led and participated in panels and debates, developed tools and training and apps and education.

And yet, by shifting the onus of child protection to peers regardless of their capacity, the authors of the less positive LinkedIn posts don’t stop to question whether all the work they do:

Only walks around the problem instead of wading into it.Constitutes a way for the powerful to put off doing — or perhaps more accurately, funding — more meaningful, effective, less profitable work.These posts thus end up being a projection of powerlessness. If the powerful aren’t doing enough, then shaming peers might be seen as “doing something.”

Perhaps that’s why the inspiration in these posts have begun to ring more and more hollow.

While, again, the rates of child abuse of all kinds reported to state child protection agencies have dropped substantially, the reasons for these declines may have come at the cost of unintended consequences.

Take, for example, the “increases in the numbers of law enforcement and child protection personnel [and] more aggressive prosecution and incarceration policies.” The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the largest crime bill in the history of the United States, provided for — among other things — 100,000 new police officers, $9.7 billion in funding for prisons, and a requirement for states to establish sex offender registries by September 1997.

The “crime bill,” however, has been blamed for a host of unintended consequences, from mass incarceration to stigmatization of juveniles and others who ended up on sex offender registries. Specifically with regard to the drop in child abuse, other unintended consequences arose:

Cases end up being prioritized based on age , effectively leaving teens and preteens to fend for themselves.Trained professionals can overreach their purview, resulting in medical misdiagnoses .“Non-protective” parents, usually mothers, have been jailed for child abuse-related crimes rather than treated as victims of intimate partner abuse that led to their choices and actions.The false equivalence of poverty with child abuse and neglect has led to thousands of children, usually Black or Hispanic, needlessly removed from their families and placed in foster care — where they went on to experience actual abuse and neglect .Changing the power and control structures requires a different approachThe activities we engage in to stop child abuse are designed by existing structures, to reinforce the same structures. Systems’ view of abuse is often facile, missing the nuance e.g. older husbands / younger wives as a foundation from economic hardship; holdover from generations where it was necessary.

By communicating that “expert” people and organizations “know better” how to “rescue” victims, in other words, the system models the very nature of abuse.

That’s because the idea of a “rescue” implies a single act with a defined outcome. In turn, an outcome implies control. To be a rescuer, a hero, assumes a person who has taken control.

It’s at this point that we’re wise to consider that “rescue” and “abuse” are opposite sides of the same coin. The nature of heroism requires a power differential; the strong save the weak — and rely on the same “othering” that scapegoats offenders and their victims.

At the same time, heroism is a denial of the weakness or helplessness we refuse to abide in ourselves. Still, denying these traits in ourselves only means projecting them onto others. A rescue requires a victim to be rescued, not an equal with enough agency to participate in their own deliverance.

By bending to the passive assumption that children must be protected from threats, in other words, we participate in denying them the active agency they will need to assert their own boundaries both now, and into their own futures.

Support more work like this series: subscribe to a paid tier, leave me a tip , and/or share this article!

5 Things “Stranger Danger” Education Got Wrong, and 1 It Gets Right

Note: this essay is Part 3 of a 5-part series I wrote over a period of years prior to Election Day 2024. In Part 1 , I described my personal experiences being groomed and the factors that continue to allow it to happen. Part 2 went into the role of generational trauma in child and intimate partner abuse. Here, I describe the failures of the "stranger danger" education I grew up with. Part 4 considers how our "hero" narratives keep us from solving the problem of (or healing from) child abuse. Finally, Part 5 offers some thoughts on how healing our own traumas could help us protect younger generations.

By now I think we all know child abuse happens regularly in the communities we trust the most, from families up through schools, churches, clubs, and so on. Yet, we continue to be shocked, dismayed, and angered when we hear about it.

Even if we don’t give in to the notion that abuse happens to other children in other communities, we still insist on believing that predators are “other”; the monsters lurking in the shadows around corners and behind bushes.

These were the threats I remember being cautioned against as I grew up in the late 1970s through the 80s and into the 90s, not least following the abductions and murders of Etan Patz in 1979, Adam Walsh in 1981, Shari Smith and Debra Helmick in 1985, Jacob Wetterling in 1989, Megan Kanka in 1994, and JonBenet Ramsey and Amber Hagerman in 1996 among many others.

But my parents’ best efforts to protect and guide me, backed by the society of their time, meant very little when I found myself groomed by men we all thought I could trust.

Failure #1: The belief that adults “know better” than kidsI have memories of my parents cautioning me to sit less provocatively on a bus where a young long-haired man was staring, unnoticed by me, at my bare leg. Indeed, he stopped after I tucked my leg safely away under my skirt (complete with eyeroll at my parents’ insistence).

I have other memories, too, from when I was very little:

Being left with an older adult woman, a neighbor, while my parents went to the hospital for my brother’s birth.Riding in a neighbor man’s pickup truck, listening to Elvis on the radio just after the famed singer’s death.Later on, older, riding an elevator at my mother’s workplace with a young man my mother half-jokingly told not to molest me.In each of these situations, my parents trusted the adults I was with, and that was good enough. In those pre-internet days, toddler rape was on no one’s radar at all. If my parents ever considered that the neighbors could pose a threat, whatever conversations they had dispelled those fears.

In the elevator, my mother’s word was supposed to act as talisman enough. She’d survived gropings and harassment throughout the 1960s and ‘70s in New York City, offering her experiences as proof that while I might be naive, she was not.

Such assumptions meant that if she and/or my father felt something was “off,” then it was off; if they trusted another adult, then so could we.

That was because in those days, no adult ever questioned ceding their own power – their own intuition, their still, small voice – to someone they believed they could trust.

Surviving “less bad” experiences, as my mother had, proved adults able to navigate threats and come out the other side. From there, they could communicate their lessons to others.

“Knowing better” was one of those values I’d heard a lot about growing up, often to describe actions or information it was assumed I already had. The main message I got was that when I didn’t know better, it meant I was incompetent to manage key elements of my own life.

I think a lot of adults think this way, and to some extent it’s even true. We do know, for example, that friend spats and clothing trends are temporary and will pass. Likewise, that some risks, like playing in the road or outdoors during a thunderstorm, aren’t worth the price of being wrong.

We also, however, place a little too much emphasis on “knowing better,” relying on both children and other adults to have the same information we have that can keep them out of trouble. When we learn they don’t, in fact, have that information, we engage in:

Failure #2: The victim-blaming emphasis on tacticsSomewhere along the way, adults lost the ability or willingness to teach children to trust our own gut sense. Instead, most of our lessons focused on abductors’ tactics. Kids in the 1970s and 80s learned not to trust strangers who:

offered candy, money, or a small furry animal to pettold us our mother had asked them to pick us up and bring us to herasked us to help them move a piece of furniture into their home or vehicleOther killers, we were led to assume, targeted and ambushed unlucky people who ran or hiked or lived alone, or who engaged in gay sex or sex outside of wedlock (especially for money), used alcohol and/or drugs, or hitchhiked.

The unspoken conclusion: you could avoid rape and murder by avoiding these activities. (Left unsaid were the ways the Zodiac Killer, Golden State Killer James DeAngelo, and “Night Stalker” Richard Ramirez targeted “normal” couples and families.)

In this context, I believed that my fascination with serial killers, coupled with my advancing age, insulated me from predation. This assumption made it easy for me and so many other girls to continue to insist that we’d “never” follow a virtual stranger into his vehicle, home, or submarine.

By shifting our attention to the salacious details of “stranger” killings and abductions, though, we laid the groundwork for the victim-blaming that ensued: our judgment on victims for their failure to protect themselves (or their children).

Even as other news items of the day demonstrated that less violent men could still prey on adult women serving in the most respectable roles as legal advisers, White House interns, and U.S. military and government personnel and spouses, we failed to realize the true threat:

Failure #3: The ignorance of groomingHaving learned our intuition had gaps, we learned to fill them in by shouldering the assumed benefit of our own and others’ experiences. Thus the adults in our lives left us vulnerable to a much different dynamic: the kind of “slow burn” grooming that happened on Bernard, Cardinal Law’s watch during that same era.

Indeed, 80 percent of sexual violence perpetrators are already known to their victims. These perpetrators, like so many other predators drawn to positions of trust and authority, manipulate relationships and power differentials.

Only one example are the priests Law ignored, who wielded their power over their parishioners and their children — particularly those with troubled situations.

I’ve written about how easy it becomes for victims, afraid of judgment and abandonment and craving a sense of connection, to mistake such tactics as part of normal relationship-building. That was my own experience being groomed in “safe” environments.

More confusing is that in this context, the idea that adults “knew better” extended to those adults we trusted not to abuse us. If and when they did, it would be our word against theirs.

By focusing on “stranger danger,” in other words, our parents’ well-meaning social messages enabled the other authority figures in our lives to deflect from the abuse happening behind our own closed doors.

They made it that much easier for predators to adapt and even blend in around our expectations of how predators prey, making it harder for everyone to understand how predators blend in — how they exploit adults, long before they ever exploit children.

It wasn’t until Ann Rule wrote her book The Stranger Beside Me about her friendship with Ted Bundy that we started to consider the lengths predators go to blend in. Yet still, Bundy and other killers of the era, including John Wayne Gacy and Jeffrey Dahmer, were considered outliers.

Failure #4: The “othering” of both predator and victimFew people talked about the ways in which Gacy, Dahmer, Bundy, and others — in contrast to the “stalker” type killers — cultivated their victims’ trust. It was assumed that they targeted only the truly outcast, without much thought either for the way they cultivated trust before they attacked — or for what made the victims outcast to begin with.

In her 2012 article “The Truck Stop Killer,” author Vanessa Veselka describes leaving home at 15:

“People don't leave home because things are going well; they leave because they feel they have to, and right or wrong, that's how I felt. I lived with my mom in New York, and the fights between us were growing in intensity and emotional violence.”

You don’t, of course, have to come from a violent home to feel “othered.” In my case, my parents’ efforts to ensure I remained outside of the 1980s-era bubble of “in” clothes and toys and music contributed to my and my brother’s ostracization by the other kids.

Other parents, though, might have gone too far in the other direction, helping their kids blend in as a matter of social survival — thus locking away their sense of self and communicating that there was no space for them to be themselves.

Add in other factors, like a learning disability or neurodivergent brain, brown skin or a foreign accent, “poor” clothes that aren’t freshly laundered – and the pressure to conform mounts. These kids might learn they are too loud, too talkative, too intense, too sensitive, too undisciplined; singled out by adults who judge them right away for being “less than.”

The overarching message: you aren’t worthy of love unless you “behave yourself” by performing well in school, doing as you’re told, not being “difficult.”

These messages teach children to remain submissive to others’ whims, to the extent kids tend to bond over “power tripping” teachers or bosses. Less social ones, like me, might learn to go inward when they feel bullied or ostracized. We must, after all, have brought it on ourselves..

In my own experience, when this twisted version of my self-image met my normal, biological teen desire to strike out on my own – learn to take my own chances and make my own choices – my parents’ best efforts backfired.

Looking back on the child predators I encountered, I can see their approximations of "normal" and the way their not-fitting-in echoed and intrigued my own. I’d already decided I had no chance of a shot with “normal” boys, much less that I’d ever be able to practice “normal” dating social cues. So when these adult men came across like fellow loners or rebels, they represented a future of adulthood in which I might just be able to be successful.

I believe this was because at some point in their lives, my groomers were the “weird kids” too. Statistically speaking, they likely survived multiple kinds of abuse of their own, experiencing one of three outcomes:

They kept it to themselves.They reported it, but were beaten and blamed and shamed.They reported it, but were ignored.In other words, they’re used to being “othered.” That’s how they recognize other outcasts, how they appeal to their acute need for a sense of belonging, and how other outcasts come to trust them.

Which I think gets at the root of our continued, collective challenges ending child sexual abuse: by “othering” both our children and child predators, we unwittingly create the space of profound loneliness in which they can come together.

Failure #5: The inability to face our own blind spotsThe problem with “othering” child predators is that when they, in fact, turn out to be men we trust with responsibility, the threat to family or community becomes too big to handle. As professor Gillian Harkins wrote in her book Virtual Pedophilia:

“The pedophile’s potential predation lurks on the surface of norms, not behind or beneath them. The sharks aren’t camouflaged; our eyes are. We are unwilling, or perhaps even unable, to see their looks as predatory.”