Neel Burton's Blog

November 28, 2025

My Beautiful Books 🦌🛷

Written for the mind, soul, and senses.

Short introduction video

Find out more about the Ataraxia and Ancient Wisdom series—and about me.

The post My Beautiful Books 🦌🛷 appeared first on Neel Burton author website and bookshop.

November 13, 2025

Free to Download: Growing from Depression

What if depression were a blessing as well as a curse? This is a book about how depression can have benefits as well as costs, and how to reap those benefits while making yourself feel better—better, in fact, than ever before.

Semi-finalist, the BookLife Prize

Semi-finalist, the BookLife Prize

Highly Commended, the BMA Book Awards

Highly Commended, the BMA Book Awards

A comprehensive, sympathetic, and thought-provoking guide for those who want to explore their depression in more depth. —The British Journal of Psychiatry

This book brings understanding and encourages independent solutions. It is remarkable in its shortness and practicality. —The British Medical Association Book Awards

★★★★★ I have read most of Dr. Neel Burton’s books and have enjoyed them immensely … All in all, I found this to be a very insightful and engaging book on depression. —Jamie Bee, Amazon.com Top 50 Reviewer

Grab your copy now for a new and powerful way of looking at depression.

READ now FOR FREEThe post Free to Download: Growing from Depression appeared first on Neel Burton author website and bookshop.

Now Free to Download: Growing from Depression

What if depression were a blessing as well as a curse? This is a book about how depression can have benefits as well as costs, and how to reap those benefits while making yourself feel better—better, in fact, than ever before.

Semi-finalist, the BookLife Prize

Semi-finalist, the BookLife Prize

Highly Commended, the BMA Book Awards

Highly Commended, the BMA Book Awards

You have, in some sense, embarked on the hero’s journey.

Despite being ill-fated, despite starting out as a victim and underdog, the hero is able to rise up to life and experience it in its horror and fullness, rather than merely suffer or survive it and occasionally drink its dregs like so many of us do.

In myth, the aspirant has to travel through hell, or deep into the forest or labyrinth, before slaying the monster and re-emerging as a hero.

If your depression is the journey through the Inferno, then let this book be your guiding Virgil.

If your depression is the descent into the Cretan labyrinth, then let this book be Ariadne’s ball of red thread.

A comprehensive, sympathetic, and thought-provoking guide for those who want to explore their depression in more depth. —The British Journal of Psychiatry

This book brings understanding and encourages independent solutions. It is remarkable in its shortness and practicality. —The British Medical Association Book Awards

★★★★★ I have read most of Dr. Neel Burton’s books and have enjoyed them immensely … All in all, I found this to be a very insightful and engaging book on depression. —Jamie Bee, Amazon.com Top 50 Reviewer

Grab your copy now for a new and powerful way of looking at depression.

Grab your copy now for a new and powerful way of looking at depression.

Happiness is good for the body, but it is grief which develops the strengths of the mind. —Marcel Proust

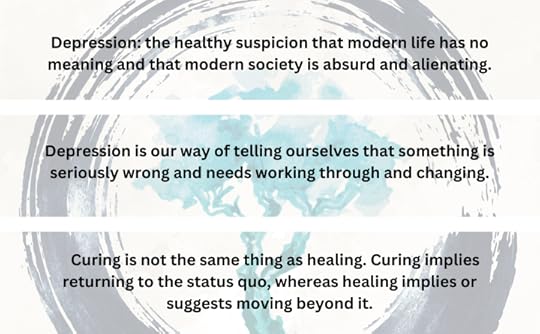

Growing from Depression—rather than, say, Recovering from Depression or Defeating Depression—is a counterintuitive, perhaps even provocative, title for a book on depression. But I chose it for what I think are three very good reasons.

• First, I wanted to challenge the popular perception of people with depression. Rather than being ‘failures’ or ‘losers’, they are often, as I will argue, among the most honest, intelligent, and sensitive of all people.

• Second, while I would never wish it on anyone, the depressive position can challenge us to identify and address long-standing life problems, potentially opening us out onto a much brighter, richer future. If we are to re-envision things, and make a leap, it helps to take a few steps back.

• Third, and most important, the journey out of depression is one of learning: learning about oneself, of course, but also learning life skills such as managing stress or coping with loss, and, above all, learning to rediscover the little things that make life worth living and loving.

As poor concentration and motivation are common features of depression, I have tried to be as clear and concise as possible. I have divided the self-help section into short, self-contained modules, enabling you to dip in and out of the book and focus on whatever seems most interesting or useful or practical.

Healing is not the same as curing. Curing implies returning to the status quo, whereas healing implies or suggests moving beyond it. My ambition is not merely to make you feel better, but better than ever before, by increasing your resilience, awareness, and openness to life.

You have, in some sense, embarked on the hero’s journey. Despite being ill-fated, despite starting out as a victim and underdog, the hero is able to rise up to life and experience it in its horror and fullness, rather than merely suffer or survive it and occasionally drink its dregs like so many of us do.

In myth, the aspirant has to travel through hell, or deep into the forest or labyrinth, before slaying or taming the monster and re-emerging as a hero. If your depression is the journey through the Inferno, then let this book be your guiding Virgil. If your depression is the descent into the Cretan labyrinth, then let this book be Ariadne’s ball of red thread.

Although depression self-help books abound, it is rarer to see one that speaks of growing through depression, rather than conquering it. Readers who have struggled with depression will find this book comforting; depression can be a useful tool in one’s life, allowing a person the time necessary to slow down, take stock in their life, and make needed changes to be more comfortable in their existence. Burton offers up countless strategies for improving one’s situation, and gives honest, thoughtful feedback about the efficacy of these interventions. —The BookLife Prize (Semi Finalist)

GET NOW FOR FREEThe post Now Free to Download: Growing from Depression appeared first on Neel Burton author website and bookshop.

October 19, 2025

Discover Naoussa: Greece’s Hidden Gem for Wine Lovers

View over Naoussa and Mount Vermio from the dominant Karydas winery—located in the kind of eudaimonic place where three thousand years ago one would have built a temple.

View over Naoussa and Mount Vermio from the dominant Karydas winery—located in the kind of eudaimonic place where three thousand years ago one would have built a temple.Naoussa is a hill town to the west of Thessaloniki, overlooked by Mount Vermio (2050m, high enough for three ski resorts) and overlooking the plain of central Macedonia. In myth, the area is the birthplace of Semele, the mother, by Zeus, of Dionysus. The modern town is very near to the Nymphaeum of Mieza, a numinous spot where Aristotle taught the future Alexander the Great and comrades such as Ptolemy and Hephaistion. And it is a short drive from Vergina, where one can descend into the rich tomb of Alexander’s father, Philip II of Macedon.

Wine paraphernalia found in the tomb of Philip II of Macedon.

Wine paraphernalia found in the tomb of Philip II of Macedon.Naoussa is the spiritual home of the most noble black variety of Greece, the difficult and demanding Xinomavro (or Xynomavro, ‘Sour black’). There are three other PDOs based on Xinomavro: Amyndeo, on a plateau on the other side of Mount Vermio; Goumenissa, an hour to the north-east in the foothills of Mount Paiko; and Rapsani, two hours to the south in the foothills of Mount Olympus (although there are currently only two producers in Rapsani). In Goumenissa, the blend must include at least 20% Negoska. In Rapsani, the blend consists of equal parts of Xinomavro, Stavroto, and Krassato. The cooler climate in higher up Amyndeo, where Xinomavro can struggle to ripen, favours the production of rosés, sparkling wine, and international varieties.

The Barba Yiannis vineyard in Amyndeo.

The Barba Yiannis vineyard in Amyndeo.In 1831, the French scholar and diplomat Esprit Marie Cousinery wrote that, ‘The wine of Naoussa is to Macedonia what Burgundy wine is to France. I am in a position to say that the wine of Naoussa is the best in the Ottoman Empire.’ In the years following the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) and the forced exchange of populations, phylloxera ravaged the vineyards of Naoussa, leading to peach trees and mixed farming. It is only in the last two decades that Naoussa has recovered something of its former glory, owing, in part, to the efforts of producer Apostolos Thymiopoulos.

Tasting with Apostolos Thymiopoulos.

Tasting with Apostolos Thymiopoulos.Today, there are some 500ha of Xinomavro in Naoussa, trained and pruned en Cordon de Royat or gobelet. Vineyards range in altitude from 150 to 400m, along the southeastern slopes of Mount Vermio (Naoussa looks a lot higher up than it is). The soils are varied, and include areas of limestone, clay, loam, and sand. There are twelve subregions with names such as Ramnista, Paliokalias, and Fyteia, although the differences between producers are greater than those between subregions. Summers are hot and dry, but autumns can be unreliable, leading to considerable vintage variation. Sheltered, sloping, and south-facing slopes are favoured to protect against spring frosts and maximise sun exposure. As elsewhere, the challenge is to minimise vigour and yields and balance phenolic and sugar ripeness. Yields are capped at 70hl/ha, but ambitious producers might aim for half of that.

In the vineyards at Dalamára, in the subregion of Gastra.

In the vineyards at Dalamára, in the subregion of Gastra.Like the light-coloured Barolo, with which it is often compared, Naoussa is structured and savoury with high acidity and tannins, although, as with Barolo, there is a modern style that requires less time in cask and bottle. To me, Naoussa seems more herbal and ‘churchy’ than Barolo or Etna, with a signature note of tomato leaf. Like Barolo, Naoussa benefits immensely from ageing, developing, after ten years, notes of roses, olives, dust, old books, frankincense, Parma ham, truffles, and chocolate. For that kind of spine-tingling wine, it is very cheap.

Tasting a delightful 2009 Karydas. The current vintage is only 13 euros ex-cellar.

Tasting a delightful 2009 Karydas. The current vintage is only 13 euros ex-cellar.There are some 26 producers in Naoussa. Favourites include Dalamara, Diamantakos, Foundi (pay the small premium for the single vineyard Foundi Estate), Karydas, Kir Yianni, and Thymiopoulos, who also makes wine in Rapsani. The Thymiopoulos Earth and Sky and Kir Yianni Ramnista are benchmark blends, and not far off, and better rounded than, pricier single vineyard expressions. In the new generation of winemakers, look out for Konstantinos Kokkinos and Socràtes Maras. It is difficult to generalise about vintages. For instance, while 2007 is upheld as a great vintage, I preferred the fresher 2009 and 2011. More recently, 2024 is hot, while 2025 is classic and very promising.

Tasting with Konstantinos Kokkinos at Whole Bunches wine bar in Naoussa.

Tasting with Konstantinos Kokkinos at Whole Bunches wine bar in Naoussa.For Goumenissa, you can go with Chatzivaritis, and for Amyndeo, with Alpha Estate and Karanika. Alpha Estate is noted, among others, for its Barba Yiannis made from centenarian ungrafted Xinomavro in a single limestone vineyard. Karanika specialises in traditional method Xinomavro. Their Extra Cuvée de Réserve, made from ungrafted old vines and released after seven years on the lees, is distinguished from Champagne by notes of roses, tea, and peaches.

Tasting older vintages at Chatzivaritis in Goumenissa.

Tasting older vintages at Chatzivaritis in Goumenissa.Several Naoussa wineries have a sideline distilling tsipouro. Both ouzo and tsipouro are anise-flavoured spirits, but tsipouro is made from pomace, and ouzo from neutral alcohol. Tsipouro can be without anise; ouzo can include other botanicals. But the main difference is that tsipouro is more grapey. Cognac, compared to tsipouro, is aged in oak.

Although close to Thessaloniki airport, Naoussa is off the tourist trail, making it a cheap and authentic destination. If you go, sleep at Palea Poli, eat at Spondi, and drink at Whole Bunches.

Neel Burton is author of The Concise Guide to Wine and Blind Tasting.

The post Discover Naoussa: Greece’s Hidden Gem for Wine Lovers appeared first on Neel Burton author website and bookshop.

October 11, 2025

Seneca on Anger, or, How to Banish Anger Forever

After his brother Novatus asked him “how anger may be soothed,” the Stoic philosopher Seneca penned his famous treatise, On Anger (c. 45 CE).

Anger, says Seneca, is a bad habit that people tend to pick up from their parents. When a child who was raised at Plato’s house was returned to his parents and witnessed his father shouting, he said, “I never saw this at Plato’s house.”

Anger is like a communicable disease. If we are around angry people, it is hard not to lose our temper, however temperate we may normally be. For this reason alone, we ought to prefer the company of mild, level-headed people. For those who don’t know, even wild animals become gentle in the company of the calm.

We should also resist our egocentric tendency to believe the worst about others. Often, the people at whom we are most liable to get angry are those who are in fact trying to help us—although, of course, not as much as we would like. In their minds, they are only trying to do what they think is best for them, and we, by our anger, are trying to thwart them—which is why they tend to return our anger. If what they are doing is not in their best interests, then we should calmly explain this to them, rather than losing our temper and, with it, their ear.

As for the things that anger us, they are often mere slights or annoyances that do not do us any real harm. Luxury debilitates the mind and undermines our sense of perspective, so that pampered people (like us) are more prone to anger over trivial things.

Even if someone murders our father or child, anger is not required to honour their memory, obtain justice, and, more generally, do the right and honourable thing. Many people think that anger is a show of virtue or, at least, a spur to virtue; at most, it can substitute for virtue in those who are lacking it.

Anger and grief only add to our existing pain, and often do more harm than the things out of which they arise. It is out of anger that Alexander the Great killed the friend who had saved his life—that great conqueror of kings, himself brought down by anger. And it is also out of anger that Medea slaughtered her innocent children.

For Seneca, “anger is a short-lived madness” (in the original Latin, ira furor brevis est) and differs from other vices in that “whereas other vices impel the mind, anger overthrows it.” The angry person, he adds, is “like a collapsing building that’s reduced to rubble even as it crushes what it falls upon.”

Being social animals, like ants, bees, and wolves, human beings are born to provide and receive assistance. Anger, which, on the contrary, seeks to arrogate and annihilate, is so inimical to our nature that some angry people have benefited simply from looking in a mirror. Those who are unwilling to check their anger and work with others for the common good are like wasps in a beehive, gorging on the honey of others without contributing any of their own.

For all these reasons, the Stoic should never get angry. She might feel the beginnings of anger, but then reject this passionate impression that threatens to overthrow her reason and the tranquillity and dignity that follows in its train.

To regain perspective when angry, to reclaim our sanity, we might ask ourselves:

“Am I expecting too much out of the world?”“How is getting angry going to help me?”“Who will remember this in a day or in a year, or in a hundred years?But the surest cure for anger is delay, because it gives us a much better chance of rejecting our passionate impression.

Before rising into the first emperor of Rome, Augustus—then Octavian—was taught by the Stoic philosopher Athenodorus Cananites at Apollonia, in modern-day Albania, where he received the news of Julius Caesar’s demise. Athenodorus followed Octavian back to Rome and remained by his side as he deftly achieved that which his great uncle Caesar could or did not. When, on account of his old age, Athenodorus begged to be dismissed and was at last taking leave of Augustus, he reminded him, “Whenever you get angry, Caesar, do not say or do anything before repeating to yourself the twenty-four letters of the alphabet.”

At this, the emperor seized Athenodorus by the hand and said, “I still have need of your presence here.”

Read more in Stoic Stories .

The post Seneca on Anger, or, How to Banish Anger Forever appeared first on Neel Burton author website and bookshop.

September 2, 2025

How to Cope with Bad News

Three ancient mind exercises for processing and subliming bad news.

Imagine: Your house has been burgled. You’ve been fired. Your partner cheated or walked out on you. You’ve been diagnosed with a life-changing condition…

Bad news can leave us in a state of dread and despair. It seems like our whole world is falling apart, almost as if we’re being driven into the ground. We fear the very worst and cannot get it out of our mind, or gut. Often, there are other emotions mangled in, like anger, guilt, despair, betrayal, and love.

Bad news: we’ve all had it, and the worst is yet to come.

So, how best to cope?

I’m going to give you three cognitive strategies, or mind exercises, that I picked up from the Stoic philosophers—who, in the second century, could count the Roman Emperor, Marcus Aurelius, among their followers.

All three strategies aim, in one way or another, at generating perspective. While reading, hold a recent piece of bad news in the front of your mind, and consider how the strategies might or might not apply to your bad news.

ContextualizationTry to frame the bad news, to put it into its proper context. Think about all the good things in your life, including those that have been and those that are yet to come. Remind yourself of all the strengths and resources—the friends, facilities, and faculties—that you can draw upon in your time of need. Imagine how things could be much, much worse—and how for some people they actually are. Your house may have been burgled. Yes, you lost some valuables and it’s all such a huge hassle. But you still have your health, your job, your partner… Bad things are bound to hit us now and then, and it can only be a matter of time before they hit us again. In many cases, they are just the flip side of the good things that we enjoy. You got burgled, because you had a house and valuables. You lost a great relationship, because you had one in the first place. In that much, many a bad thing is no more than the removal or reversal of a good one.

Negative visualizationNow focus on the bad news itself. What’s the worst that could happen, and is that really all that bad? Now that you’ve got the worst out of the way, what’s the best possible outcome? And what’s the most likely outcome? Imagine that someone is threatening to sue you. The worst possible outcome is that you lose the case and suffer all the entailing cost, stress, and emotional and reputational hurt. Though it’s unlikely, you might even do time in prison (it has happened to some, and a few, like Bertrand Russell, did rather well out of it). But the most likely outcome is that you reach some sort of out-of-court settlement. And the best possible outcome is that you win the case, or better still, it gets dropped.

TransformationFinally, try to transform your bad news into something positive, or into something that has positive aspects. Your bad news may represent a learning or strengthening experience, or act as a wake-up call, or force you to reassess your priorities. At the very least, it offers a window into the human condition and an opportunity to exercise dignity and self-control. Maybe you lost your job: time for a holiday and a promotion, or a career change, or the freedom and fulfilment of self-employment. Maybe your partner cheated on you. Even so, you feel sure that he or she still loves you, that there is still something there. Perhaps you can even bring yourself to look at it from his or her perspective. Yes, of course it’s painful, but it may also be an opportunity to forgive, to build a closer intimacy, to re-launch your relationship—or to go out and find a more fulfilling one. You’ve been diagnosed with a serious medical condition. Though it’s terrible news, it’s also the chance to get the support and treatment that you need, to take control, to fight back, to look at life and your relationships from another, richer perspective.

A Taoist story for the roadThere’s a Taoist story about an old farmer whose only horse ran away. “Such terrible news!” said a neighbour. “Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t,” replied the farmer. The next day, the horse returned with six wild horses. “Such wonderful news!” exclaimed the neighbour. “Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t,” replied the farmer. The day after that, the farmer’s son tried to tame one of the wild horses but got thrown off and broke a leg. “Such terrible news!” cried the neighbour. “Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t,” replied the farmer, biting into a peach. A week later, war broke out: thanks to his broken leg, the farmer’s son managed to escape military conscription. “It all worked out really well in the end,” said the neighbour, “such great luck!”

“Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t,” replied the farmer, rolling his eyes.

Neel Burton is author of Growing from Depression, which is currently free to download from his website bookstore.

The post How to Cope with Bad News appeared first on Neel Burton author website and bookshop.

September 1, 2025

The Wines of the Valais and Switzerland

Domaine the Beaudon in Fully, Valais, accessible only by cable car.

Domaine the Beaudon in Fully, Valais, accessible only by cable car.Only 1% of Swiss wine is exported, and what does get out is usually rare and expensive. A ceramic wine bottle was found in the Valais, in the tomb of a Celtic woman who lived in the second century BCE. In the sixth century, monks from Burgundy established a monastery at Aigle, Vaud, and began cultivating the vine with their customary dedication. Before the arrival of phylloxera in 1874, the country counted ~35,000ha of vines, compared to ~15,000ha today. In 1990, the Valais set up a European-style appellation system, and other cantons soon followed suit.

Today, owing to domestic tastes, more red than white wine is produced, and quality can be very high. The most important area, accounting for almost 70% of national output, is in the francophone west, along Lake Geneva (cantons of Geneva and Vaud) and into the upper Rhône valley (canton of the Valais, see below). In Geneva, where I grew up, plantings are very diverse, including national favourites such as Gamay, Pinot Noir, and Chasselas; international varieties such as Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, and Pinot Gris; modern hybrids such as Gamaret and Garanoir; and local varieties such as Altesse and Mondeuse. In neighbouring Vaud, the climate is moderated by the lake, which also mirrors sunlight onto proximal vineyards. The region is dominated by Chasselas, which is highly reflective of terroir. Its most revered expressions are the Grand Crus of Dézaley and Calamin on the terraced slopes of Lavaux, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Other areas include the Rhine valley in the north and north-east, Ticino south of the Alps, and Lake Neuchâtel (‘Trois Lacs’) in the west.

Overall, the climate is cool, but the Valais is relatively warm and dry, and Ticino warm and humid. Typically, the cool climate and rugged landscape restricts viticulture to favourable pockets, placing natural limits on production volumes and holding sizes. Over 240 varieties are cultivated, the most common being Pinot Noir, Chasselas [Fendant, Dorin, Gutedel], Gamay, and Merlot. Pinot Noir accounts for around three-quarters of plantings in the Germanic north and north-east, Chasselas for around four-fifths of plantings in Vaud, and Merlot for almost nine-tenths of plantings in Ticino. Pinot Noir and Gamay are often blended to produce Dôle, a concept similar to Bourgogne Passetoutgrains, with a rosé version known as Dôle Blanche. Oeil de Perdrix [‘Eye of the Partridge’], most associated with the area of Neuchâtel, is a pale rosé made from Pinot Noir. Switzerland is full of blind tasting quagmires, such as red Dézaley, Neuchâtel Viognier, Thurgau Pinot Noir, Valais Syrah, and Ticino white Merlot!

The Valais Terraced vineyards in Chamoson

Terraced vineyards in ChamosonThe Valais (‘the real Northern Rhône’), with its 5000ha under vine, produces over a third of Swiss wine, and is without a doubt Switzerland’s most important and interesting wine region. Most plantings are on the terraced southeast facing-slopes of the main valley, stretching 50km from Fully in the southwest to Leuk in the northeast, where the road signs slip from French into German. There are also small plantings in the side valleys and on what, before climate change, used to be the ‘wrong side’ of the main valley.

Vineyards range in altitude from 450m to 800m or even 1000m in Vispertal. Above them is the Valais’s other claim to fame: its picturesque Alpine resorts such as Leukerbad, Evolène, Zermatt (Matterhorn), Verbier, and Crans Montana. And below them, along the Rhône, fruit trees, industry, and urban development—and two hilled castles at Sion, which you can visit for a view of the surrounding vineyards (sturdy shoes required, skip the museum).

Owing to the Alps and foehn winds, the climate is surprisingly warm and dry with, annually, 2100 hours of sunshine and just 600mm of rain. At Domaine de Beudon in Fully, cacti (prickly pear) have naturalised at 800m asl. The long growing season and high diurnal temperature variation support organic viticulture, late ripening, and the production of sweet, sometimes botrytised, wines, known locally as vins flétris. The main threats are spring frosts and summer droughts, and light irrigation of the thin soils is often necessary.

These soils are varied, ranging from granite in the west (favourable to Gamay) to chalk in the east (favourable to Pinot Noir), interspersed by areas of loess, moraine, schist, and pebbly alluvial fan. Some fifty grape varieties are permitted, but the most important are Pinot Noir and Gamay for the reds, and, for the whites, Fendant (Chasselas with berries that split)—introduced from Vaud in 1848. Other important varieties include, for the whites, Johannisberg (Sylvaner), Petite Arvine, Heida (Savagnin, also called Païen in the Bas Valais), and Ermitage (Marsanne), and, for the reds, Syrah, Humagne Rouge, and Cornalin. There are 12 designated Grand Cru villages, each one for a limited number of grape varieties. These are Chamoson, Conthey, Fully, Leytron, Saillon, Saint-Léonard, Salgesch, Savièse, Sierre, Vétroz, Sion, and Visperterminen.

2005 Fendant with Lake Geneva perch.

2005 Fendant with Lake Geneva perch.When I visited, I was most impressed by the Cornalin (a variety which repays its difficulty with silky notes of morello cherry and cloves), Syrah, Fendant, Petite Arvine, Heida, and the rarer Amigne and Humagne Blanche (which is unrelated to Humagne Rouge). In total, there are only 41ha of Amigne, 33 of which are in Vétroz. All these varieties are seriously ageworthy. At its best, Fendant resembles Chablis, and I tasted several excellent 20-year-old examples with notes of toffee, marzipan, cognac, and—still—a salty, iodine finish. Favourite producers include Simon Maye in picturesque Chamoson (try the Fendants and, later, drive up to Les Violettes for a terroir lunch), Jean-René Germanier in Vétroz (try the Cayas Syrah), Domaine de Beudon in Fully (try the old Fendants), Denis Mercier and Domaine des Muses in Sierre, and Cave Caloz in Miège.

Neel Burton is author of The Concise Guide to Wine and Blind Tasting.

The post The Wines of the Valais and Switzerland appeared first on Neel Burton author website and bookshop.

August 31, 2025

How the Ancients Coped with Grief, Loss, and Bereavement

The Stoic Seneca is the master of the ‘consolation’, a letter written for the express purpose of comforting someone who has been bereaved. Seneca wrote at least three consolations, to Marcia, to Polybius, and to Helvia. In the Consolation to Helvia, he comforts his own mother Helvia on ‘losing’ him to exile—an unusual case, and literary innovation, of the lamented consoling the lamenter.

The emperor Marcus Aurelius (d. 180 CE) had at least fourteen children with his wife Faustina, but only four daughters and one unfortunate son, Commodus, outlived their parents. In the Meditations, Marcus likens his children to leaves, and paraphrases Homer in the Iliad:

Men come and go as leaves year by year upon the trees. Those of autumn the wind sheds upon the ground, but when the spring returns the forest buds forth with fresh vines.

Marcus was a Stoic, and would have known, at least in principle, how to cope with grief, loss, and bereavement. But if Seneca could have consoled Marcus on the loss of his children, and could only have told him three things, what might those three things have been?

First, Marcus, remember that life is given to us with death as a precondition. Some people die sooner than others, but life, on a cosmic scale, is so short that, really, it makes no difference. Even children are known to die—indeed, they often do—and these, Marcus, simply happened to be your own. A human life, however long or short, or great or small, is of little historical and no cosmic consequence. Since a life can never be long or great enough, the most that it can be is sufficient, and we would do better to concentrate on what that might mean.

Second, it may be that death is in fact preferable to life (the secret of Silenus). Life is full of suffering, and grieving only adds to it, whereas death is the permanent release from every possible pain. Indeed, many people who have died—think only of our friend Cicero—would have died happier if they had died sooner. If we do not pity the unborn, why should we pity the dead, who at least had the benefit, if benefit it is, of having existed? The unborn cry out as soon as they are delivered into the world, but to the dead we never have to block our ears. If weep we must, it is not over death, but the whole of life, that we should weep.

Third, we should treat the people we love not as permanent possessions but as temporary loans from fortune. When, in the evening, you kiss your wife and children goodnight, reflect on the possibility that they, and you, might never wake up. In the morning when you kiss them goodbye, reflect on the possibility that they, or you, might never come home. That way you’ll be better prepared for their eventual loss, and, what’s more, savour and sublime whatever time that you have with them—and, in that way, lead them to love you more.

If you do lose a loved one, do not grieve, or no more than is appropriate, or no more than they would have wanted you to, but be grateful for the moments that you shared, and consider how much poorer your life would have been if they had never come into it.

The post How the Ancients Coped with Grief, Loss, and Bereavement appeared first on Neel Burton author website and bookshop.

August 18, 2025

10 Unexpected Benefits of Hardship

Why the Stoics valued self-imposed hardship.

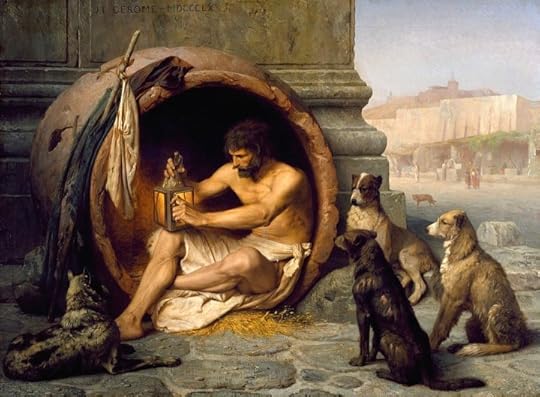

Diogenes in his barrel.

Diogenes in his barrel.In the deep winter, Diogenes the Cynic (d. 323 BCE) would strip naked and embrace bronze statues. One day, upon seeing this, a Spartan asked him whether he was cold. When he said that he was not, the Spartan replied, “Well, then, what’s so impressive about what you’re doing?”

Like their predecessors the Cynics, and like the Spartans, the Stoics greatly valued hardship, albeit on a more modest or moderate scale. We should, they said, routinely practice poverty or put ourselves through mild hardship, and this for several reasons:

First, to discover what we can do without, and reduce our fear of losing those things. In his Letters, Seneca advises Lucilius: “Set yourself a period of some days in which you will be content with very small amounts of food, and the cheapest kinds, and with coarse clothing, and say to yourself, “Is this what I was afraid of?””

Second, to be reminded that simple things, such as bread and olive oil, or a good night’s sleep, can be just as enjoyable and profitable as any great banquet (if not more so), and thus that pleasure is both readily available and highly transferable.

Third, to better reflect upon our true goals, or to work towards them. “If you want to have time for your mind” says Seneca, “you must either be poor or resemble the poor… One cannot study without frugality, and frugality is just voluntary poverty.”

Here are six more advantages of self-imposed hardship, according to the Stoics:

To increase our appreciation and enjoyment of the things that we normally enjoy.To break from our normal routine, and reinvigorate our minds while exercising our freedom.To be prepared for future hardship, which, unless we are suddenly struck dead, is all but a certainty.To be convinced that the greater part of our suffering lies not in fact but in our attitude towards it.To practise self-discipline, or test our fortitude.To empathise with less fortunate people, and people from the past.In addition, self-imposed poverty and hardship can also have more mundane benefits, such as losing weight, saving time or money, and making yourself popular by seeming like one of the people.

Finally, all these motives are in themselves a source of pride and pleasure of a different kind. “Do not” says Marcus Aurelius, “lament misfortune. Instead, rejoice that you are the sort of man who can undergo misfortune without letting it upset you.”

Seneca does us the favour of putting self-imposed hardship into radical perspective when he says: “Armies have endured being deprived of everything for another person’s domination, so who will hesitate to put up with poverty when the aim is to liberate the mind from fits of madness?”

Neel Burton is author of Stoic Stories.

The post 10 Unexpected Benefits of Hardship appeared first on Neel Burton author website and bookshop.

August 5, 2025

Ancient Paths to Inner Peace: Why You Should Walk in a Labyrinth

As I argue in The Meaning of Myth, mazes and labyrinths are spiritual tools, not mere amusements or diversions.

The post Ancient Paths to Inner Peace: Why You Should Walk in a Labyrinth appeared first on Neel Burton author website and bookshop.