Bolaji Olatunde's Blog

September 13, 2024

Fighting an Impolite Virus

Review of An Imperfect Storm:n A Pandemic and the Coming of Age of a Nigerian Institution by Chikwe Ihekweazu with Vivianne Ihekweazu by Bolaji Olatunde

Publisher: Masobe Books and Logistics Limited

Date of Publication: 2024

In 2020, the world stood still, terrorised by a disrespectful virus named by COVID-19 by scientists. At no point does the narrative stand still in this riveting memoir by Dr Chikwe Ihekweazu and his wife, Vivianne Ihekweazu. In 2016, Dr Chikwe Ihekweazu, was plucked from relative obscurity to become the head of the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), “with the mandate to lead the preparedness, detection and response to infectious disease outbreaks and public health emergencies.” Prior to his appointment, he’d worked variously in Europe and South Africa for twenty years.

The book’s narrative, rendered in an unflappable tone, settles the reader into a ringside seat of Nigeria’s war with a virus, through Dr Chikwe Ihekweazu’s eyes. The authors remark on COVID-19 being like many other viruses, “are little impolite things. They make no special consideration for holidays or other festivities.” The book opens with Dr Chikwe Ihekweazu being alerted to “’the pneumonia of unknown cause’ from Wuhan, China,” while holidaying during the 2019 Yuletide in his village, Amaigbo, southeastern Nigeria. “The new virus had effectively shut down a city the size of Lagos,” he reports.

Chikwe Ihekweazu discusses his experiences as medical student at the University of Nigeria, Enugu, from where he graduated in 1996. His “housemanship” in Aba also comes up, “where the nurses demanded competence, and the senior doctors weren’t only unapproachable but often completely unavailable.” His counterintuitive switch from surgery which had him spellbound as a student, to public health, which he’d earlier considered to be boring will fascinate the reader. His childhood on the grounds of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, where “his (German) mother started out as a lecturer in the Department of Foreign Languages,” and his father, “was one of three doctors at the university hospital” will interest the reader.

This insight into his background shifts seamlessly into the battle against COVID-19. Chikwe Ihekweazu admits to his initial intense apprehensions about Nigeria’s ability to survive the onslaught of the virus, after a trip to Wuhan in February 2020, in the immediate onset of the virus: “I wasn’t confident in our capacity for infectious disease management in other hospitals across the country.”

Chikwe Ihekweazu details how the Nigerian fight against the virus was made possible by cohorts of Nigerian professionals from every stratum of society, wielding and deploying their experience, expertise, guts, local and international networks, to ensure the prevention of the virus’s spread. The average Nigerian may be tempted to assume that the successful fight against COVID occurred by happenstance; the Ihekweazus’ book shows that it involved meticulous, on-the-job strategizing and implementation. He also details the transformation carried out by him and his team at the NCDC, which was created in 2007. Ihekweazu reports that under his leadership, that he and his team changed it from a little-known government parastatal which by 2016 had a hundred reportedly mostly demoralized staff to a well-oiled machine of about five hundred staff, which enabled the NCDC to become the public front in Nigeria’s fight against COVID-19.

From the accounts in the book, the fight also took its personal tolls on the Ihekweazu family, and the staff of the NCDC. Upon Chikwe Ihekweazu’s return from Wuhan, he had to go into isolation in line with the COVID-19 protocols which were previously instituted by the NCDC. His son was “asked to stay at home to protect other students because his father had travelled to China,’ despite the said father having tested negative to COVID-19. To further complicate the times, Chikwe Ihekweazu had a well-kept secret health challenge that necessitated an invasive surgery — this, in the middle of the war on COVID-19. “Our staff were subjected to insults and death threats on social media.” Staff who were lost during the fight, both to natural and unnatural causes, are, commendably, honorably mentioned.

At several points in the memoirs, Chikwe Ihekweazu bemoans the poor remuneration of staff of government agencies in Nigeria, and their disincentive to staff morale. It would have been an insightful addition in the book, if the Ihekweazus discussed how they coped economically with the reduced pay (“I took a pay cut, but it’s not really a matter of what the DG earns,” Chikwe Ihekweazu replied to a question from this writer during a book reading in Abuja in August 2024). This would have proved useful for Nigerian professionals in the diaspora who are willing to return home to contribute their quota to national development someday.

The backroom shenanigans and power play behind the COVID-19 fight are some of the most spellbinding aspects of the book. The circumstances around the death attributed to COVID-19 of Abba Kyari, aka “case number 43,” the chief of staff of the then Nigerian president, Muhammadu Buhari, are well explored. The vivid recollection of the frenzied reactions at The Presidency to the death of “case number 43” will set the pulse of the politically inclined racing. Unbeknownst to the general public, there was no love lost between Chikwe Ihekweazu and the then minister of health, Dr Osagie Ehanire, as well as several other officials in the top echelon of the Federal Ministry of Health, the NCDC’s supervising ministry. “In the end, I realized that an important relationship had been strained, and I don’t think I was ever forgiven for it,” he writes wistfully about the minister’s reaction to the management of information about Kyari’s illness.

Chikwe Ihekweazu expresses perplexion at vaccine hesitancy, especially among health workers. “If the very people who had seen the devastation of COVID-19 up close were unsure about the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines, how could we convince the rest of the population?” he wonders. “Every day unearthed a new conspiracy about the vaccines, even among those who should have known better,” he writes. No mention or allusion is made to the not unfounded reports of people vaccinated against COVID-19 and yet becoming victims of the same virus they were inoculated against, most notably President Joe Biden of the United States of America. The failed promise by the vaccine manufacturers that the vaccines would prevent the transmission of the virus is not mentioned either. His regrets about Nigeria’s response to the virus are freely discussed.

Intended by the authors or not, An Imperfect Storm: A Pandemic and the Coming of Age of a Nigerian Institution is one of Nigeria’s most important public health and national health security documents of today.

Rating: 4 stars out 0f 5

July 9, 2024

Review of "Vagabonds" by Eloghosa OsundeThis is a novel ...

Review of "Vagabonds" by Eloghosa Osunde

This is a novel that makes the bold attempt tobe a literary manifesto of sorts for Nigeria’s LGBTQ community. Theintroductory pages of the book make that clear. The opening pages have thefollowing notices from the author: “There are simple and good andstraightforward and well-behaved people, I’m sure. But this isnot a book about them.” The author also defines the word “Vagabond” as aNigerian noun (used) “In the states of Bauchi, Gombe, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano,Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, Yobe, and Zamfara,” to refer to “any male person whodresses or is attired in the fashion of a woman in a public place or who practicessodomy as a means of livelihood or as a profession.” In the author’s definitionfor the female vagabond, the word covers “any female person who dresses or isattired in the fashion of a man in a public place.”

The novel is also an ode to Lagos, exploringsome of the myths and fascinations that the city holds for both the dwellersand outsiders looking into that complex city. “There is an eye following youand you know. Everywhere you go, e dey look you. The eye is made up of people.The eye does not blink, talk less of sleep. The eye is us, curious. The eye isa city; this eye na Lagos.”

The novel starts off quite well, exploring a popularNigerian urban legend: the football match between India and Nigeria, whichevery one knows Nigeria lost 100 to 0, even though no video or formal of thematch exists in FIFA’s archives. We meet Thomas who makes the mistake ofstanding at the market place, bending and staring between his knees at themarket, on Christmas eve. The reader also meets Johnny, who leaves Uyo to joinhis cousin, Clement, in Lagos to become a driver to a very powerful unscrupulousman, Mr H, with a terrible source of income that demands silence: “State thatyour tongue in your mouth does not move, whether your oga is there or not,”Johnny is told when he arrives at his new boss’s Lagos home. To complicate thealready warped situation, Johnny gets into an “entanglement” with Mr H’spersonal assistant, Livinus, whose mouth can’t keep shut and causes trouble. Thereader also gets the shapeshifting “Hoverer” Toju, who is also bisexual, whomoves from body to body, slips in and out of them, appears to fall in love withmen, and then abandons them — spiritual one night stands and flings, if youwill. There is also the most memorable character for this writer — WuraBlackson, who “started out by making dresses for herself and her best friends,after all; all of them from families whose fathers were corrupt leaders who’drobbed the country insane…Wura’s work stood out because her creativity wasbottomless.” There are several other characters, which allows room for aweakness that can engender — the room for exploring them is very limited, thuslimiting how interesting and memorable they can be, or be made to be by anauthor.

There are several references to the Same-SexMarriage (Prohibition) Bill signed into law in Nigeria on January 7, 2014,which stipulates long jail terms for those who enter into same-sex marriagecontract or civil union (14 years in prison), any individuals or groups,including religious leaders who “witness, abet, and aid the solemnization of asame-sex marriage or union,” (10 years in prison). Those who “directly orindirectly make [a] public show of [a] same-sex amorous relationship” andanyone who “registers, operates, or participates in gay clubs, societies, andorganizations,” are also subject to, upon conviction serve 10 years in prison. “Wherewere you on the thirteenth of January 2014, when that law was passed?” asks “Tatafo”,a narrator (or whatever they may be). The latter half of the novel explores thedifficulties faced by Nigeria’s LGBTQ community. “God hates boys who loveboys,” says a Sunday school teacher, which makes fourteen-year-old Junior, oneof the characters, wonder, “Or did God make me on a day when He was too tired,when He was taking a break from being God?” “And besides, he’s learned thatpeople keep their sins to themselves as a matter of etiquette,” Junior notices.The novel has more adult characters falling in and out of same sexrelationships, most of them concealing the relationships so as not to causeembarrassment to family. Of course, the hypocrisy of some religious housescourting members of the LGBTQ community, and paying them to pretend to behealed of the spirit of homosexuality is explored.

Eloghosa Osunde is a wonderful wordsmith. Sheputs the words together in an impressive manner, blending the King’s Englisheffortlessly with Pidgin English and current Nigerian slang reflective of theday. This unashamed pride in the street talk of Nigeria is wonderful to observe. One could not help but be awed by itall. The first half of the novel was fascinating to read. However, the novelbecame a drag midway. The last chapter “Tatafo (Water No Get Enemy!” was agreat struggle to read, for me; its incoherence was a marvel. One of thosethings you have to complete because you know you have to get it done to getwhat the point of the novel is.

“If anybody deserves to live…it is us. It isus, after all this dying we have done,” goes the final line of the novel.

Rating: 3 out of 5 starsMarch 18, 2024

The Heptagon Revolt

I'd like to also believe it can be enjoyed by a teen class in a secondary school/high school class, and a sociopolitical or socioeconomics class in a university. I have revisited George Orwell's fable for the 2020s, with all the fun subjects, and more.

The Heptagon Revolt has reflections on capitalism, socialism, migration, DEI, gender issues. It's dedicated to my nieces and nephews, and their generation, who've left Nigeria -- who may never live there again. Something for their parents to show them about the values back home.

Amazon.com https://www.amazon.in/Heptagon-Revolt...

Barnes and Noble https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-...

Revolution!

The two humanguards who watched over the dogs when the Big Fight occurred left the farm thefollowing week. They were replaced by two other guards. To prevent the spreadof Covid-19, it was decided that the guards would be rotated weekly. EvenJohnbull Osagie could not visit the farm regularly because the police men andsoldiers deployed to the streets of Abuja prevented the free flow of people andtraffic. The health authorities of the government said that the less people mixed,the less the disease was transmitted from one person to another. The dogs wereamused to see the human guards with surgical face masks covering their mouthsand noses.

When they resumedtheir duty, the new batch of human guards were informed about the importance ofallowing the dogs out of their cages at least once a day. Johnbull Osagie didnot want a repeat of what had occurred in the recent past.

Liz warned herchildren to be careful with the older dogs. She told them to protect themselveswhenever the other dogs ganged up against them. She was lucky sometimes to belet out of her cage in the same batch as her offspring. When that happened, shegathered her offspring together and whispered to them about the need for themto protect one another. She noticed that Rex had become more withdrawn andspoke less after the Big Fight – he had a defeated look about him. Rex was themost wounded dog after the Big Fight such that the scars were visible on hisbody. The scars and welts from wounds were caused by Bruce hitting Rex withhard blows from his paws. When his cage was opened for him to leave his cageand run around on the field, Rex was so obviously reluctant to step out of hiscage. The human guards had to force him out on such occasions.

“Rex, one daysoon, you will be big and strong, stronger than even Bruce and his stooges,” Liztold her son directly. It was on a day that she was in the same batch of dogs asher children, the dogs who were let out of their cages. “In life, one must facemany battles. You win some, you lose some. You must prevent the losses fromgetting you down,” she added. Rex nodded to show that he understood.

The Big Fight showedthe dogs that there was a new champion dog on the farm – it was Bruce. Everyonesaw how he had beaten both Rex and Danladi, without so much as a scratch on hisfur. He was always followed by his three acolytes, Shadow, Rambo and Captain. Asusual, they walked with him quietly with suspicious looks in their eyes, asthough warding off any possible attack. Their suspicion was unnecessary becauseno dog on the farm dared to even dream of physically attacking Bruce.

At dawn, one morning during thelockdown, the dogs on the farm sensed a loud noise approaching the farm. Itsounded like a large creature was walking fast towards the farm. The dogs onthe farm with a view of the sky saw a large cloud of dust rising in thehorizon, over the high fence that surrounded the farm. All the dogs on the farmheard what sounded like the barks of a million dogs, barking in unison. Thenoise frightened some of the dogs on the farm, both the young and older dogs. Theolder dogs wouldn’t openly admit it afterwards, so they wouldn’t be thought ofas weak. The hearts of the dogs on the farm beat faster than ever. Theirinstincts told them that something great and unusual was upon them.

“What is goingon?” some of the dogs on the farm asked aloud and barked to one another.

The human guardsin the security house were woken up by the cacophony of barks from outside thefarm, as well as the barks by the dogs on the farm, under their charge. Theyemerged from the security house dressed in their underwear, just in time to seewhat appeared to be an uncountable number of dogs leaping over the high fence. Thesurprised guards froze in their tracks for a few seconds because it was unlikeanything they had ever seen before. When they recovered their wits, the guards fledtowards the large gates of the farm. The gates had a side entrance forpedestrians. The invading dogs chased after the human guards. The guards threwopen the pedestrian entrance of the gates and ran as fast as their feet couldcarry them away from the farm. The invading dogs continued to chase them untilthey were out of sight. Another batch of dogs ran querulously around the outerpart of the farm’s fence, in search of any humans. When they didn’t find anyhumans, they changed course. They returned to the farm compound. The pedestriangate was shut by the dogs.

Another batch of dogsran into the giant kennels where the dogs were kept in cages. They opened thecages with such skill that the farm dogs were taken aback and impressed. Thefarm dogs watched in awe, wondering how a member of their species had managedto learn how to open the locks with such expertise.

The freed farmdogs leapt out of their cages and most of them stopped in front of the entranceto the giant kennel. They watched in amazement as the invading dogs dashed toand fro on the field, doing what appeared to be a victory dance. A continuoussound of thunderous victory barks could be heard at every corner of the farm,and even beyond. Some of the invading dogs leapt into the air with great excitement.

Oriade watched itall in awe from the entrance to the great kennel. He knew it was a specialmoment, a thrilling spectacle.

While thecheering was going on, a male dog, bigger and heads taller than all theinvading and the farm dogs put together, approached the centre of thegathering. From his looks, Oriade knew that humans would regard the biggest dogas a stud, worthy of being used for breeding. This was because he had thepowerful looks that humans sought in dogs. Oriade’s eyes caught the big dog’s leftear and managed to see a birthmark on the inside of his left ear. Oriade’s heartbegan to beat furiously. He recalled what his mother Liz had told him about theirfather. He looked around for Liz, but he could not see her in the crowd ofdogs. The big dog growled and snapped so loudly that the noise carried out farinto the crowd. The invading dogs went quiet immediately.

With his right forepaw,the big dog waved the invading dogs to a section of the large farm field. Theinvading dogs moved into formation around him in a circle, standing together onall fours in neat rows. He waved his right forepaw again and a clearingappeared between the invading dogs. The farm dogs stood in front of the giantkennel, obviously impressed by all that they had seen. Some of them wereconfused and fearful too. The big dog looked sternly at the farm animals.

“Good morning,fellow dogs!” the big dog said to the farm dogs in a booming voice. “We areone! Do not fret. We’re here to help you. We’re here—” he paused dramaticallyand continued, “TO FREE ALL DOGS FROM HUMANITY!”

All the invadingdogs cheered and stamped their legs on the field so hard that dust rose intothe air. The big dog raised his right hand once again and waved it. The was pindrop silence on the dog farm instantly.

“My name isBobby! Some of you have heard about me!” said the big dog. Ruth, Rex and Oriadeexchanged excited looks. “With these loyal dogs from mostly the southern partof Nigeria, I plan to liberate all dogs on earth from the tyranny of mankind. Historytells us that the first dog was subjugated – humans say tamed – on African soilhundreds, or thousands of years ago. We will reverse this, starting fromAfrican soil!”

The invading dogscheered heartily. Some of the farm dogs began to cheer, impressed by Bobby’soratory.

“While we welcomeother creatures in the struggle to free ourselves from the bondage of humans,we shall focus mainly on the dog race! We know we can be stronger, and we canbe better than we are now! Now that we have taken over this farm, it shall beour temporary headquarters as we push towards spreading this revolution up toour canine counterparts especially up in Northern Nigeria. We’ll then spreadthe canine revolution to other parts of Africa!”

The cheers thatfollowed were almost unanimous, except for Bruce and his three acolytes,Shadow, Rambo and Captain, who watched the proceedings wordlessly and withoutany expression on their faces.

“I dream of a daywhen all breeds of dogs – the Alsatian, the German shepherd, the terrier, thebulldog, the beagle, the dachshund, the poodle and chihuahua – will look upon oneanother as brothers and sisters. Join us today, and I promise you won’t regretit!”

The dogs cheered.

“With mygenerals, we have planned to take advantage of the lockdown that the humanshave embarked on to prevent the spread of the Covid-19. Now that humans aresafely locked away in their homes, this is the best time for us to move. Wemust move with lightning speed. We have been able to free dogs because of thisrestriction of movement of humans. We’ve freed dogs from farms like this one,although this is the largest farm that we have conquered. We have freed dogsfrom the captivity of hunters, local vigilantes, and security officers. Wedon’t know how long the lockdown will last, but act, we MUST!” Bobby went quietin a way that suggested he was through with his speech.

The cheers andbarks at the end of Bobby’s speech were the loudest noises the farm had everheard.

The Heptagon Revolt was published in March 2024 by LaTunes Publishers. It is available at the following stores.

Amazon.com https://www.amazon.in/Heptagon-Revolt...

Barnes and Noble https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-...

October 30, 2023

Wahala By Nikki May: A Review

Nikki May says she wrote Wahalabecause she wanted to see herself in a book — middle-class, mixed-raceNigerian living in Britain https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Iq5N.... It’s anovel inspired by a “long and very loud lunch with her Nigerian friends inLondon”. That aspiration has been met. Shealso believes the success of the book will mean that she has been forgiven fordropping out of medical school. She shares this characteristic with a characterin the novel. The average helicopter Nigerian parent sparingly forgives suchacts but it’s not unknown to happen.

Three female best friends based inLondon have a close bond. They share several characteristics, as close friendsoften do. They are all of mixed race (more popularly described in Nigeriansociety with the word “half caste” which is a pejorative in the West and acompliment in Nigeria). All of their fathers are Nigerian, their mothers areCaucasian. Ronke (Ronks), Boo (Bukola) Whyte and Simisola (Simi) first becamefriends when they first met at university in Bristol, thus sharing an almamater. “Father issues was the only other thing the friends had in common. And asubject best avoided. Ronke’s — perfect but dead. Simi’s alive butdisappointed. Boo’s — non-existent and good-for-nothing. They are all women intheir mid-thirties.

Ronke, unmarried dentist, has hada string of broken relationships, mostly with Nigerian men. Simi and Boo areseemingly happily married; the former to Martin who is a white Briton, thelatter to Didier, a white French man. Ronke’s friends feel degrees of pity andcontempt for her choice of men. “I just wish you’d find someone you could counton, who’d treat you right. Someone white. Or at least not a Nigerian. Dull andsteady, like Didier,” Boo says to Ronke in the opening pages of the novel. Almostneedless to say, Kayode King, Ronke’s boyfriend does not impress her twoclosest friends.

Into this ordinary (dare one say“mundane”?) dynamic catwalks Isobel Babangari-Adams, Simi’s mixed-race childhoodfriend, offspring of a marriage between a Nigerian man and a Russian woman.Their friendship was severed when Simi’s father fell from grace and was expelledfrom the Ikoyi Club in Lagos, ostensibly for loss of financial wealth, becausehe lost his single client, Isobel’s father. The three women’s lives are turnedupside down in what seem like happenstances and mere serendipity. Thedenouement causes Boo, Ronke and Simi to reevaluate their lives and theirfriendships —they find out that their lives were even interconnected long before they met. Theystart to understand, first hand, what betrayal feels like (“So, this was howbetrayal felt — like being punched in the stomach”), or confiding secretsin people whose tongues have no censor (“It was like being in primary school —back-stabbing, rumours, he said, she said,” Simi muses to herself at somepoint.)

The novel is well-paced and goodhumoured. It introduces the outsider looking in on the lives of young mixed-raceNigerian women, their aspirations, dreams, career drives and shows that theyare as human as anyone else, and subject to the same pressures that youngNigerians resident and working in Nigeria, face from their families, in respectof educational attainment and accreditation, career progression and gettingmarried. Simi’s father is unhappy that she dropped out of medical school, but isforced to come to terms with her success as a fashion magazine editor; hisexpression of his disgruntlement in various verbal and nonverbal cues arekeenly observed in the novel.

The efforts of the diasporaNigerian to fit into British society are well documented. “Simi marvelled asRonke morphed into a Nigerian; she sounded as if she had never left Lagos. Simihad worked hard to master her English accent and didn’t drop it for anyoneever.” One is reminded of the complaints of this demographic about being tooalien to fit into either Nigerian society or their new home countries. “InNigeria, Simi would have been called oyibo or akata but mostlyshe’d been called yellow. It wasn’t meant to be offensive, it was acompliment.” In typical millennial quest to add to an ever-growing list offorbidden words, the word akata has been added to a list of racial slursagainst African Americans.

One cannot but observe the placeof food in the narration of the story. Almost every other page of Wahaladrips with oil, carbs and allied edibles. There’s food-food-food everywhere —British, French Nigerian!

One couldn’t help but bediscontented at the representation of the Nigerian man in this novel as somephilandering, unthinking brute whose existence is to make women, be theyNigerian (mixedrace or solely black) or white, into a miserable person at the end of romanticor marital interactions. The only Nigerian man with a semblance of faithfulnesscomes to a violent end. “They don’t trust me because I am black. They’ve bothgot white husbands and I am not good enough because I am Nigerian,” lamentsKayode King. “Simi believed it was impossible to be racist if you were mixed.The more of us (mixed race people) the better. If only the world would shagracism into oblivion,” is Simi’s thought on the subject. “But I don’t get it.What on earth were our mothers thinking? I am not being racist…Why would anysane English woman go for an African bloke?” says Boo during a lunch meetingwith Ronke, much to the dismay of the latter — who dates mostly Nigerian andAfrican man in relationships that end badly. This pigmentocratic datingpreference based the premise that Nigerian, and African men, are less thantheir white counterparts is so popular today among certain categories ofAfrican women that it’s not unusual to find on dating sites, Nigerian women statingwithout equivocation on their profiles that only white men may apply. Theconcept of the unthinking, deceitful, and unfaithful Nigerian man is becomingoverused trope, both in literature and on social media. And cheating isn’tgender specific, as one of the three friends shows us when she strays from thenest and has an affair with a colleague. In a society where the “kidnap value” (amountof ransom likely to be paid by a kidnap victim) of a mixed-race person ishigher than that of a person who is a hundred per cent black; a Caucasian fetchesmore.

The representation of the PidginEnglish spoken by the characters in the work leaves much to be desired andcaused my eyes to roll more than once. This is remarkable, given that the titleof the novel is a Pidgin English synonym of “trouble” or “upheaval”. I doubt ifa truly Nigerian novel about contemporary Nigeria would be regarded as completewithout the appearance or use of Pidgin English; it’s important that authorsconfer widely to get its cadences and nuances. “Where did you get tis effigy, ehn?...Itfine pass, o!” exclaims Mama T, Simi’s stepmother, upon sighting a priceysculpture —the Ife head — Isobel gifted all three friends. Any Nigerian caughtspeaking Pidgin English this way on Nigerian origins and street smartsquestioned immediately.

Wahala isa fun novel. It was an interesting ride, watching friends come to terms withfactors beyond their control and realising the importance of friendships andrelationships in our lives.

Rating: 3 out of 5 stars

Naira Power by Buchi Emecheta: A Review

Buchi Emecheta was once described by her son asa “womanist”, a word that is perhaps closely related to the more popular word,“feminist”. Her ideas about the place of a woman in what is ostensibly 1970sand 1980s Nigeria are explored in this novella that packs a punch that is fargreater than its small weight.

“Going to the United Kingdom must surely belike paying God a visit,” Buchi Emecheta declared in a BBC One programme TheLight of Experience about her perceptions about that island as a little girlgrowing up in Ibusa, Nigeria. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K7cAwemP-u8 She vowed to someday visit thatcountry; she would go on to live there for decades. Bintu, the narrator of NairaPower by Buchi Emecheta, follows this path. “I am a woman who has stayed morethan half of her life in the United Kingdom, pursuing one set of studies andthen another,” Bintu introduces herself at the beginning of the novella.

The book opens with Bintu explaining that shehas been visiting her family in Lagos, Nigeria and has spent some time withNurudeen, her younger brother, and his third wife, Amina. “I am in my prime,thirty-five or so, but I still call Amina my wife,” Bintu remarks on theAfrican culture of referring thus to a spouse of the member of the family. “So,she even felt it an honour for me to refer to her as ‘Amina my wife.’ I couldhear and feel the vibrant happiness in her voice when she called back, ‘Yes, Auntie.’”The novel opens on the day that Bintu is expected to fly back to the UnitedKingdom. Nurudeen rules his house sternly. As he coordinates the house, Binturemarks, “I could hear my brothers grave and sullen voice say something nastyto this person, or that person. I could hear Lamidi whimper in pain. I knewwhat had happened, my brother had given him a slap or two…But aggressivenessand rudeness are all part and parcel of being a male, I suppose.” The preceding lines set the tempo for thenovella: female solidarity in the face of patriarchy and outright malechauvinism. “My eyes caught hers and we nearly collapsed laughing…For thatsplit second we forgot we were women. We forgot that we were meant to laughonly gently in a subdued, feminine way,” narrates Bintu about the hilarity sheand Amina derived from Nurudeen’s strict conduct of the house’s affairs. For abook first published in 1982 under the Macmillan Pacesetters series, thesentiments expressed in the immediately preceding extract are perhaps notstrange.

While she waits impatiently for her returnflight to the UK, Bintu offers to follow Amina to the market. As Amina drivesthem to the market, they stumble on a mob that has apprehended Ramonu, a manfrom Amina’s past. A member of the mob tells Amina that Ramonu was caught allegedlypickpocketing “an Ibo man” at the National Stadium in the middle of a footballmatch. The mob burns Ramonu alive. A rain suddenly starts thereafter, and thetwo women are trapped in Lagos’s notorious traffic. The novella is mostlyAmina’s recollections of Ramonu’s life — mostlyuntoward adventures in the quest for wealth. It turns out that they grew uptogether at Isalegangan, a fictitious neighbourhood on Lagos Island. “Lemonuwas the name of Ramonou’s father. He came to Lagos as a young man. A very longtime ago, he travelled from the North to the South to sell his cattle…Lemonuspoke neither English nor Yoruba,” but he found success as a sanitary officer.Lemonu’s story is like many who join the rural to urban drift and make it bigby using their wits and derring-do; his is slightly more different because he achievesit somewhat legitimately. As is expected of successful men, Lemonu delves intopolygamy, and the deleterious effects on Ramonu is presented to the reader. Ramonu’srelationship with his father hits the rocks as a fall out of this domesticpolygamous arrangement, leading Ramonu being disowned by his father. After someyears, Ramonu suddenly shows up, wealthy and in a far better financial statethan his father had ever been. His past transgressions are forgiven, and hefinds favour with the neighbourhood. Everyone wants to be Ramonu’s friend, orwife. “If you don’t have naira power here, Auntie, you are lost. Money can buyyou everything, even justice. Everything,” Amina tells Bintu as she narratesthe story.

The theme of polygamy rings all through thenovel. Bintu wonders how her civilservant brother manages to maintain his three wives and their many children. “Menwith many wives end up not having a single wife-friend among the women theywork for all their lives,” Bintu observes. Bintu, much to her surprise, findsthat Amina is not the docile, unexposed person/third wife she initially thoughther to be. “Our mothers always told us that if you let your husband know allabout you, you are asking for trouble,” Amina tells Bintu, after she disclosesthat the relationship between Ramonu and her was not platonic. It is common tofind that many Nigerians in the diaspora look down on Nigerians who live athome, considering them anything buy exposed, smart or wise; both educated anduneducated alike. When Bintu wonders why Amina had never told her husband aboutRamonu, Amina retorts, “My mother told me never to undress in front of myhusband. He would never respect me. So. All these five years, my husband hasnever known how I look and he will never know. Do you think I should tell a manlike that I had an adventure in my youth?” Bintu is very much surprised at theeconomic awareness possessed by Amina despite her limited formal education, asthey lament Ramonu’s fate. “We both agreed that the tragedy that was Ramonu wasthe fault of nobody, but that of a society that respects any fool who hasnaira.” The Nigerian in the 2000s understands this sentiment very much.

Buchi Emecheta effectively takes the readerinto Lagos of yore, when “One of the civil laws of Lagos states that onlyeven-numbered cars should run on the roads on certain days, and on other days,only odd-numbered vehicles.” Her descriptions of Lagos are vivid. She also accurately captures the attitudes ofa lot of Nigerian men to the premiership of Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s. “Myhusband says that the United Kingdom is full of sick men. He says that is why theyhave a woman ruling them and a woman is their prime minister,” Amina tellsBintu, much to the dismay of the latter.

However, as with novellas, the majorshortcoming I observed was the shortage of further material or informationabout the major characters in the novel.

I have little doubt about it; as Naira Poweris reprinted and distributed once again, it will be an impactful book foranother generation of Nigerians and Africans, especially to the younger readersfor whom the Pacesetters series was initially designed.

Rating: 4 out of 5 stars

October 13, 2023

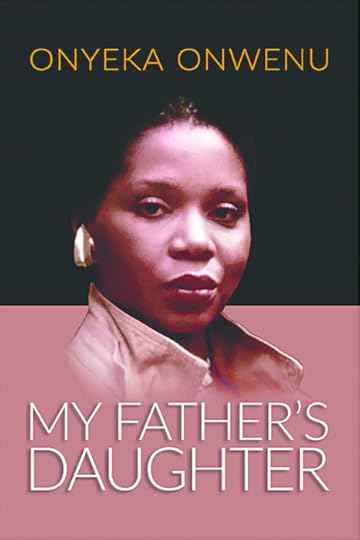

My Father’s Daughter by Onyeka Onwenu : A Review

Book Publisher: Expand Press Limited, Lagos

Date of Publication: 2020

Rare is a published memoir by a Nigerian musician. Lady Onyeka Onwenu has served the reading public with this intriguing insight into her life. To her long-time fans, the title “Lady” may come as a surprise ─ to many who have followed her over the decades, she is known simply as “Onyeka”.

My earliest memory of Onyeka is watching her on television circa 1983, in her much younger days, roll across the bonnet of a black Rolls Royce car, singing away (or probably more accurately, miming away) a song that I can’t remember, but easily outshining the Spirit of Ecstasy, the sculpture that adorns Rolls Royce bonnets. It was a sensual dance, one can say with the benefit of hindsight, but my childish brain thought, “Hmm, that’s a very playful person. I should marry her.” Evidently, by the time, Onyeka was aware of “the power of Kpongem” — the power of a “firm backside” which she proclaims in her memoirs was passed down the family line from the maternal roots. After all, this was the 1980s, when Kris Okotie implored whoever was so inclined to show him their backside, long before he became a Pentecostal pastor. A fan of her music was created after sightings of that music video. The first music album I bought with my own money — her self-titled 1990 album “Onyeka”, sponsored by Benson & Hedges, the cigarette brand.

Onyekachi Akuchukwu Onwenu was born in Obosi, on the 29th of January 1952 to schoolteacher and politician Dixon Kanu (DK) Onwenu and Hope Onwenu aka Sister, who was a teacher and trader. Onyeka takes us through her early childhood memories, growing up in Port Harcourt as her father’s favourite daughter, and her evolution into a proud independent, feminist Igbo woman and one of Nigeria’s most easily recognizable celebrities.

“I am a feminist because I am a woman who is blessed, talented, hardworking, and imbued with the strong belief that I can contribute my quota to make the world a better place…Being a woman does not make me the weaker sex,” she writes firmly, for the avoidance of doubt for those doubtful of her stance on women’s rights.

“My Father’s Daughter” is an autobiography filled with previously unknown things about Onyeka. The most defining moment in Onyeka’s life was the tragic loss of her father when she was four years and eleven months old. The loss of that son of Arondizuogu village in a car accident; he was an elected member of the Federal House of Representatives under the National Council of Nigeria and Cameroon (NCNC). “Most times, when death calls, it gives no warning. It does not give you time to prepare. It burrows through the door of your house like the typical unwanted guest,” Onyeka muses. Her vivid narration of the day he died and burial show that the memory is deeply implanted. Her attribution of his death to what is popularly regarded in Nigeria as “diabolical means” is no less riveting. The mantle of steering the young family subsequently fell on Onyeka’s mother, Hope Onwenu, daughter of the Nwokoyes of Obosi. Onyeka also details her mother’s pitiable struggles as a thirty-seven year old widow in 1950s Port Harcourt, dodging the wiles of “big men” who either wanted to marry her or have her sell her late husband’s property to them at giveaway prices.

Onyeka lived through the Nigerian Civil War which commenced when she was fifteen. “The world has no conscience,” her mother’s cousin lamented to her during the war, as they sought refuge, migrating across towns like millions of other south-easterners, to avoid Nigerian army troops, who from all accounts, did not often distinguish between south-eastern civilians and actual Biafran combatants when they carried out extrajudicial killings. “Two weeks before my eighteenth birthday, the fires died down. Yet, the ashes continue to smoulder in my memories,” she writes. In lucid language, she contends that the war caused a loss of innocence and morality in her home region. “For many, everything became about money…The natural Igbo inclination for collective progress was soon replaced by ruthless individualism,” she avers in lucid language, comparing life before and after the war.

In 1971, she visited Lagos, the then capital city of Nigeria, for the first time, before her imminent departure to the United States of America for further education; her formal education was suspended during the war. As if the universe, in its ever mischievous method, was informing her of a future career in music, she recounts a fortuitous meeting with Fela Anikulapo-Kuti who pulled alongside her on the streets of Surulere and invited her to his nightclub; an invitation that she accepted but admits to not having any intentions of fulfilling even on the spot.

“Stepping into the dining hall, dressed in an Ankara trouser and top, I was immediately aware that all eyes were on me,” Onyeka writes about her first days at the Baldwin School, Pennsylvania, a prep school she attended prior to proceeding to Wellesley College, Massachusets, where she studied International Relations and Communication. As is the common experience of emigres of the day, she remarks with slight amusement on the shock of her western classmates about her “spoken English and overall academic performance.”

Onyeka serves up interesting and hilarious anecdotal encounters with international and Nigerian political figures and entertainment celebrities. There’s an unintended interruption of a conversation between the bemused spouse of Yasser Arafat and Hilary Clinton, herself a Wellesley College alumnus; her meetings and relationship with Winnie Mandela, wife of Nelson, for whom she wrote and dedicated an eponymous song that was performed when the famous man visited Lagos in 1990, just after his release after twenty-seven years of incarceration by South Africa’s Apartheid government.

An entire chapter is dedicated to recollections of meetings and relationships with notable Nigerian figures. She explores her relationships with other female Nigerian musicians and the travails they had to suffer in a largely conservative society where women are supposed to be seen and not heard. She recounts the innuendos, especially of a sexual nature, spread about her, and other female musicians, simply to smear their reputations because they refused to do as they were told. “If you must date someone, do so because you want to, but not for political or financial reward,” she advises women, young and old. It may surprise many old timers to know that Christy Essien-Igbokwe, the “lady of songs” and Onyeka’s assigned rival number one (assigned by fans of both singers), shared a close friendship. The late Tyna Onwudiwe (African Oyibo and also alleged to be a one-time lover of Charly Boy Oputa) also had an intense friendship with Onyeka. Onwudiwe shared a flat in Surulere after Onyeka quit her job at the United Nations and decided to return to Nigeria to put her energy where her mouth was, all based on a chance encounter with another Nigerian who chastised her for being an arm chair critic ─ pillorying the nation from the safety of the comfortable offices of the UN.

A “stern” encounter with former Nigerian president, the late Shehu Shagari, “usually soft spoken” leaves her surprised.

“You this Squandering of Riches woman,” she says were his first words to her. It was an allusion to a 1984 BBC documentary she presented, which focused on corruption and maladministration under the civil rule during the Second Republic. The documentary features the young Onyeka and Tyna Onwudiwe dancing vigorously with the cheerful abandon of happy youths in a Nigeria that was not exactly what they desired, but was, from all accounts, better than the one in which she has written the book. She laments that the migration pattern is now predominantly westwards, as young Nigerians move to the west to fulfil their potentials.

There is a second meeting with Fela Kuti circa 1985 who ─ surprise, surprise ─ asked her to marry him, a proposal she rejected on the spot. There is a #MeToo moment with Sonny Okosuns ─ yes, of the famous “Papa’s Land” anti-Apartheid freedom chant ─ whom she accuses of ungentlemanly conduct in an alleged quest to get her to show gratitude for helping her to record her first album at EMI International’s famous Abbey Road, London studios, where famous musical acts like the Beatles recorded. There are hints at financial malfeasance on Okosuns’s part; he negotiated her recording deal with EMI International, terms of which she insists she was never made fully aware of due to naivety and doing music at the time as a hobby.

The rumours of a romantic dalliance with King Sunny Ade, juju music maestro, receive severe dismissal. They were so widespread that even General Ibrahim Babangida, the then Nigerian military president, was compelled to inqure from her if they were true. “Even you?” she recalls asking the man. Onyeka insists that the relationship with Sunny Ade did not go beyond the professional boundaries of recording the hit songs, “Choices” and “Wait For Me”.

Onyeka dishes on her love life, describing a teenage crush that was lost and ruefully expresses regret at some point about what might have been. She describes falling in love and being the live-in-lover of “a Yoruba Muslim” she met in 1984, at the time she had just come onto fame and fortune as a singer. In a move guaranteed to elicit admirable nods from privacy-philes, and reactions of disbelief from many of today’s young generation, her (now ex-) husband’s name and pictures are completely absent from the book. She attributes this to an agreement they reached early not to share their relationship with the world. In these days of active over-sharing, by celeb and non-celeb alike, this is uncommon. For years, the “junk media” of the eighties, at the height of her fame, hounded her about the identity of her husband. The closest she disclosed was her children’s identity, not only in the book, but in an interview from the late 1980s with the now defunct Weekend Concord, owned by Chief MKO Abiola.

Like DK Onwenu, Onyeka Onwenu, could not escape the lure of political involvement. She explains her role in the “One Million Man March” organized in 1998 to encourage military dictator, Sani Abacha, to “run” for the office of president. “I did not acknowledge Abacha in whatever capacity. I made no comments other than to wish the Super Eagles the best of luck at France ’98,” she insists. That single episode of her appearance at the march marred her estimation in the minds of many of her fans. It was considered a monumental betrayal by die-hard supporters of the then imprisoned Chief MKO Abiola, winner of the annulled June 12, 1993 presidential election. She admits that Abiola was often a financial benefactor of hers who made public showings of his support of her musical career. Another national figure she hobnobbed with and campaigned for (she wrote and performed a song for his 2011 presidential campaign “Run, Goodluck Run), ex-president Dr Goodluck Jonathan, appointed her as the director-general of the National Centre for Women Development, Abuja. The public space, online and offline, is filled with complaints persona while she held sway at the centre, with some describing her as an arrogant and inconsiderate boss. Her own account of her tenure at the National Centre for Women Development is so filled with drama, it is worthy of a television series all by itself.

Lady Onyeka Onwenu, the elegant stallion, singer, actress, administrator, business woman, will always be a part of the memory of generations of Nigerians “of a certain age”, and perhaps of the younger ones who saw her turn as the diabolical mother in the movie adaptation of the novel “Half Of A Yellow Sun” by Chimamanda Adichie. Her songs will linger in the nation’s artistic memory, as will images of her with her low cut afro, white patch just above her forehead, will accompany the memories of those musical classics. The image of the author on the back cover of the first edition may throw longtime fans aback somewhat ─ the black braids certainly surprised this writer! Her politics has divided, and will continue to divide her fans, and maybe non-fans. One thing may well be beyond question to the curious reader ─ “My Father’s Daughter” is a well-written recollection of a most interesting life.

Rating: Five out of five stars

October 9, 2023

When We Were Fireflies by Abubakar Adam Ibrahim: A Review

Yarima Lalo, a young man, a painter with his studio on Kolda Street, off Adetokunbo Ademola Crescent, Abuja, on which is located some of the costliest real estate in Nigeria’s capital city, although the novel does not hint at or suggest that. To himself, he has always been an ordinary person, until one Friday “on a hot June day in Abuja…it occurred to him that once, many years before, he had been murdered in the carriage of an old locomotive with the well-worn seaweed-green seats.” With this prepossessing opening, Abubakar Adam Ibrahim pulls the reader into Lalo’s past lives, with death making a constant reappearance.

In the Hollywood movie, The Bucket List, Carter Chambers (played by Morgan Freeman) tells Edward Cole (played by Jack Nicholson) that in the Buddhist concept of reincarnation, a being returns to the world in either an upper or lower station of life, based on how they lived their previous lives. Edward Cole asks rhetorically, “What would a snail do to move up the line? Lay down a perfect trail of slime?” Well, what does Lalo have to do to warrant these returns over three generations? Fall in love with the wrong woman, for the most part, and be at the wrong place at the wrong time — and end up murdered by unsavoury characters. The returning being also has a penchant for reappearing in major northern Nigerian cities across these past lives — Kano, Kafanchan, Jos. Yarima Lalo has vague recollections of these past lives, and as a human is wont to do, he sets out to unravel the full details — the truth — of those lives, vowing to avenge the deaths of those who had killed him in his previous lives. He is accompanied on the journey by Aziza, a divorced-single mother, and Mina, her daughter from her failed marriage.

The novel is also a love, or almost love, story between Aziza and Yarima. Aziza, former banker and now henna parlour owner — or Mai Lalle, to use the Hausa description of the occupation, walks into his painting studio one afternoon and a remarkable relationship is born. At first, she thinks he is mentally unstable when he tells her that he has been dead before, “He speaks about it and I wonder if his family knows he is losing it. He seems like a nice person but I am worried he needs help,” Aziza says to Hajiya Batulu, one of her customers, who would unwittingly lead them to, Indo, Batulu’s mother, a key witness in one of Yarima’s past lives. Aziza supports Yarima as he tries to uncover the past; he supports her as she deals with childhood trauma, and her in-laws trying to wrest Mina from her, so that her mother-in-law, who was missing her soldier son who disappeared during a battle with “the boys”, as the people of Baga in the novel call the Boko Haram insurgents.

The themes also include the insurgency that has ravaged northern Nigeria for more than a decade, and the huge toll it takes on the officers of the Nigerian army who fight the war against the insurgents; two of the leading characters are victims of the war. The religious crises that erupt occasionally and lends an unpredictability to life in usually calm and friendly northern Nigerian cities is also explored in the story.

The novel is a soaring triumph of majestic prose. Ibrahim describes life in Abuja with fine detail, and draws the attention of the reader to those aspects of life in the city that may escape one due to the increasingly bustling nature of the place. The characters muse about life in Nigeria, and maybe everywhere in the world: “We are all fleeing a war. If not in our homes, then in our hearts, in our minds. In everything we pursue, we flee other things.”

I would have given this novel five out of five stars, but one has to score it four due to what I perceive as a shortcoming: the “Americanisation” of the dialogues between the characters. That cadence of daily Nigerian conversation was disrupted by this limitation. Along the way, in the present day, Yarima meets a grandmother with whom he was desperately in love with, in a previous life. He is now young; she is a wrinkled version of her former self, which induced in this reader the evocation of a similar romance in Ibrahim’s award-winning novel Season of Crimson Blossoms. The distinct dialect and cadence of 2010s and 2020s American, or Americanised, teen comes across as they dialogue and reminisce about pre-independent Nigeria, or discuss the results of Yarima’s research into his past on the telephone—I found this off-putting, especially when one considers that they conversed in Hausa, the lingua franca of the region. A little more “timeless” quality should have been infused into their communication, I believe. Although I find this instance to be the most noticeable example, there are several dialogues that come off this way in the novel. There is also the small matter of Yarima’s reproductive inadequacy that was not, in my opinion, sufficiently explored in the novel. Could the insufficiency have been an evolutionary result of some sort, preventing Yarima from being in the position to be summarily despatched to the other world, for another return?

In total, a well-crafted novel based on a fascinating premise.

Gravel Heart by Abdulrazak Gurnah: A Review

Now, I get an inkling why Abdulrazak Gurnah got the Nobel Prize for Literature. It is a beautiful novel, Gravel Heart, and is also the first Gurnah title I have read.

"I don't know why you want to study literature. I don’t know where this idea came from. It’s a pointless subject.” This statement by Uncle Amir, said to the protagonist, Salim Masud Yahya, when he admits that he had no business studying finance in the university, sent me into hysterics. Every African literature student must have encountered this argument at one point in their careers. At some other point, the narrator says, “What is the point of literature? I think that the person who asks that question will not find my answer convincing.”

The unspoken family secret that simultaneously unsettles and binds Salim’s maternal extended family is treated with such sensitivity and adequate suspense, as only a skilled writer can, and should.

Salim’s migration to the United Kingdom forms the major part of the story. His story illustrates the racism, and the difficulty of an African finding love in 1980s (?) Britain. His encounter with a white lady is simultaneously appalling and hilarious: “One of them was pulling my shirt and reaching into my jeans, that she would have gone to bed with me if I weren’t black, but since I was, she wouldn’t. I asked if she would do it if I were Chinese. She thought about it for a moment and said she would. She went back to snogging me after that and I made no effort to resist even though honour required that I should repel her and walk hauntingly away.” Lust almost never fails to disgrace men sometimes.

There is of course the examination of “revolutionaries” on the African continent in the 1970s and 1980s: “They speak a familiar language of freedom, but plan to enforce it with violence.” And of course, after they succeed, “All the children of the powerful were being groomed to be powerful. That is what families do, if for no other reason than to ensure the security of their plunder. That’s how things are.” There is the keenly observed “progress” made in this regard, as the West demands more from African leaders, as Salim notes: “Now they all wear suits and ties because they want to look like statesmen, but then everyone wanted to look like a guerrilla.”

My single grouse with the novel? I wish it were easier to decipher the timeline of the story in relation to the reality of Zanzibar; the timeline seemed all over the place, perhaps it is deliberate to show the flexibility of memory.

I really enjoyed reading the novel, and the regular wisdoms shared (“Our doubts are traitors,” or as Bibi, Salim’s maternal grandmother used to say, “This is the burden we all have to bear, to live a useful life.”) The finality of death, “Dying is such a degrading business.”

I look forward to reading other titles by Abdulrazak Gurnah.

Allah is Not Obliged by Ahmadou Kourouma: A Review

Aha! Welcome to the child-soldier-fiction-fest that is Allah is Not Obliged. It was first published in 2000; I first read it in 2023. As I read it, those tropes I’d seen in Hollywood movies about war-torn regions in Africa – fiction and nonfiction alike – started to come alive. I am not sure the effect this novel by Ahmadou Kourouma had on those Hollywood stories about the continent’s troubled zones, but Allah is Not Obliged is a powerful novel.

As the ten year old narrator, the “fearless, blameless, street kid, the small soldier’ (read “boy soldier”) Birahima, says, “Allah is not obliged to be fair about all things he does here on earth.” A fatalistic outlook on life that one has to adopt to survive the crazy. Birahima takes on a heart-stopping and heart-rending. It’s filled with zany characters, from fraudsters to sex abusers to mass murdering warlords. I assume it’s one of those novels that, rightly or wrongly, made the child soldier the face of Africa back in the noughties in popular culture.

For a child, Birahima comes across as worldly-wise, which could happen when anyone goes through what he went through early in life. He has to watch his physically challenged mother drag herself around while her infected legs give her endless pain, with the attendant ever present smell of rotting flesh; Birahima is told by the father figure he has around him, Balla, “…No kid ever leaves his mother’s hut because her fart stinks.” When the chance arrives for Birahima to leave his mother’s hut, he leaves for Liberia in the company of Yacouba, the sweet-talking hustler who transforms from smuggler to shaman, as the occasion dictates. Together, they travel from Guinea to Liberia, and then Sierra Leone in 1990s West Africa. An ambush, caused by an accidental shooting done by guards of their travel party in Liberia leads Birahima to the path of becoming a child soldier.

As they move from one war zone to the other, Birahima observes that, “That’s wars for you. Animals have more mercy for the wounded than humans.” He somehow manages to see the method in the madness of the warlords and commanders he comes across; above all is the desire for material things that drives their motivations. “General Baclay was weird, but she was a good woman and in her own way she was very fair. She shot men and women just the same, she shot thieves and it didn’t matter if they stole a needle or a cow. A thief is a thief, and she shot everyone of them. She was impartial.” The desolate situations of many of the child soldiers is also observed: “When you haven’t got no father, no mother, no brothers, no sisters, no aunts, no uncles, when you haven’t got nothing at all, the best thing to do is become a child soldier.” The warlords invoke God at every turn; the role of religion and superstition is keenly explored in the story. For instance, “God had commanded that he, Prince Johnson, wage tribal war. Wage tribal war to kill the devil’s men. The devil’s men had so gravely wronged the people of Liberia. And chief among the devil’s men was Samuel Doe.” The wiles of these troublesome warlords are presented with dark humour, for those with a high threshold for gore, and it could be horrifying for those who are a lot more sensitive.

To say that most of the warlords and commanders are insane would be an understatement. They encourage drug use among the child soldiers under their command (“A child-soldier needs drugs and hash doesn’t grow on trees. It’s expensive,” Birahima says.) The roles of West Africa’s big brother, Nigeria, in the wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone are also explored and their relation to the current times were eerie (There's currently serious public debate about whether Nigeria should invade neighbouring Niger to restore that nation to civilian rule, after the civilian president was ousted in a military coup). “Nigeria is the most heavily populated country in Africa ad has loads of soldiers they don’t know what to do with, so they sent their spare soldiers to Liberia with the right to massacre the innocent civilian population, the whole works. The Nigerian troops were known as the ECOMOG peace-keeping force. ECOMOG troops were now operating all over Liberia and even Sierra Leone and massacring people, all in the name of humanitarian peacekeeping.” As a Nigerian, I was struck by this. Many Nigerians heap praise the past achievements of their military in those nations; many are unaware of the well documented atrocities attributed to its troops in those countries.

I found it unrealistic that a boy locked away in child soldier camps, engaged in gun battles while raiding the camps of other commanders, would be politically aware enough to make some very accurate statements about the sociopolitical scene of 1990s West Africa. For instance, this remark which caused me to go into hysterics because of how true it is: “National conferences were the big political meetings that every African country held in 1994 where everybody just said the first thing that came into their heads.” However, you never know — that I am willing to concede. It’s possible the boy was only parroting things (propaganda?) he’d heard from his much older commanders.

I found the novel to be a page turner. Its strength is its overall realism. It confirms Marvin Gaye’s words in his song, “What’s Happening Brother” — “War is hell.”