Daniel A. Masters's Blog

October 12, 2025

A Scene of Public Grief: Bringing the Boys Home After Stones River

A few weeksafter the Battle of Stones River, a trio of gentlemen from Salem, Ohio traveledto the battlefield to retrieve the bodies of some of their townsmen who diedduring the battle. In an extraordinary account from the editor of the SalemRepublican, he described the sad scene that marked the arrival of thebodies at the town hall.

“The rough boxescontaining the dead were placed side by side on the platform of the hall andwere opened as speedily as possible,” he stated. “The first box openedcontained the body of Captain Bean; the next was Hale’s, and so on until allwere opened. Among the few men present was an aged father whose son lay in arude coffin before him. How eagerly he gazed at his boy and said, “That’s myson!” and left the room.”

“Few of us present on this occasion ever saw such a sight aswas here presented. There lay the bodies of four young men in the pride andglory of manhood, three of whom has been buried on the battlefield just as theyfell and presented a ghastly appearance which we do not feel like describing.Captain Bean had been buried in a coffin and did not look so bad,” he wrote.

The article goes on to describe thenature of the wounds suffered by each man and explained how the community bothhonored and grieved for its dead heroes the next day. Special thanks to friendof the blog Ken Bandy who shared this remarkable source from his personalcollection of 65th Ohio accounts.

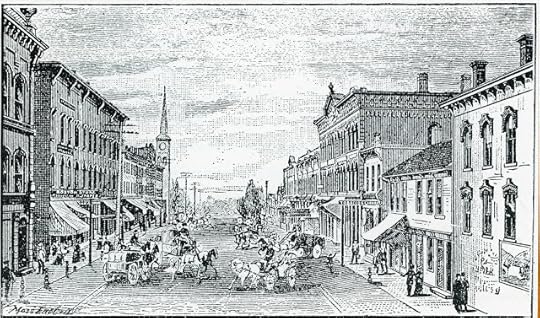

Broadway in downtown Salem, Ohio

Broadway in downtown Salem, OhioMessrs. Hudson, West, and Wilson, who left this place onMonday after the Battle of Murfreesboro for the purpose of procuring the bodiesof Captain Urwin Bean [Co. E, 19th Ohio], Thomas T. Hale [ Co. B, 65thOhio], Robert D. Wilson [Co. D, 19th Ohio], Joseph Bull [Co. B, 65thOhio] , Abner J. Crampton [Co. B, 65th Ohio], and Benton Speakman [Co.B, 65th Ohio] returned on Tuesday evening of last week at 10 o’clockwith the above bodies except Crampton’s which they were unable to procure.

Mr. West arrived at home on the Sunday morning previous,leaving the bodies in charge of Hudson and Wilson. Mr. West left the party atElizabethtown, Kentucky, some 40 miles south of Louisville, the snow being sodeep, some three feet, that the train was unable to proceed further. Mr.Hudson, seeing no chance of getting to Louisville by rail, hired a wagon andeight horses to take the bodies by the Lebanon Pike to Louisville, 46 milesthrough the snow. At Louisville, they came by boat to Cincinnati where theywere again placed on board the cars and safely arrived as we stated above.

Although the night was a dismal one, quite a large number ofour citizens were at the station to receive the bodies and have them conveyedto the town hall where they were to be dressed before delivering them to theirfriends. We could not, at this time, but notice the marked difference in themission of those here congregated on this cold, stormy winter’s evening withthose who had assembled over a year ago to bid the same young men, whoselifeless and lacerated bodies lay before them, the last farewell and a heavyGodspeed in the service of their bleeding country.

But tonight, how changed! The earth is robed in a whitemantle and the cold winds of mid-winter are hurling the rain and snow on everyhand, a fit emblem of the occasion. Back then, the beautiful autumn hadshowered her richest treasures upon us and our hearts were light. A sad change hascome over that scene and we are walking amid the wreck of a bloody battle asthe rude boxes before us attest. We hear not the cannon’s roar, nor the quick,sharp crack of the rifle, but here are the remains of a few of the brave menwho participated in that death struggle and have given their lives for thecountry they loved.

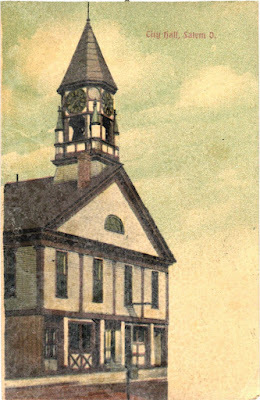

Salem City Hall

Salem City HallLocal History Collection,

Salem Public Library

The bodies were conveyed to the hall with the exception ofWilson’s which was taken to New Albany where his mother resides. The roughboxes containing the dead were placed side by side on the platform of the halland were opened as speedily as possible. The first box opened contained thebody of Captain Bean; the next was Hale’s, and so on until all were opened.Among the few men present was an aged father whose son lay in a rude coffinbefore him. How eagerly he gazed at his boy and said, “That’s my son!” and leftthe room. Who can tell the agony of a fond parent for their child under suchcircumstances?

Few of us present on this occasion ever saw such a sight aswas here presented. There lay the bodies of four young men in the pride andglory of manhood, three of whom has been buried on the battlefield just as theyfell and presented a ghastly appearance which we do not feel like describing.Captain Bean had been buried in a coffin and did not look so bad.

As to the nature of the wounds, Captain Bean was shot in thebreast, the ball passing through his right lung, causing almost instant deathby suffocation. The hair on the left side of his head was clotted with bloodbut no signs of a ball mark could be found. The ball entered the right hip ofSergeant Hale, passed through him, and came out on the left side just below thehip bone. He was carried to the camp hospital nearby and did not die until thenext morning.

Joseph Bull was killed by a piece of shell which explodednear to where he was standing and struck his right side, just below the ribs,and passed through him making a frightful wound. A piece of the same shellwounded Lieutenant R.S. Rook who was standing near him at the time. BentonSpeakman was shot; the ball entered just in front of his left shoulder andpassed through his chest and bowels, coming out near the hip bone on the rightside. He must have been leaning over, or stooping down, at the time. He waskilled instantly.

The bodies, after being washed and dressed, were placed intheir coffins and on Wednesday morning they were delivered to their friends. CaptainBean’s remains were encased in an iron burial case and remained in the hallduring the forenoon and were visited by a large number of citizens. His body,in charge of his brother, was taken to Norristown, Pennsylvania for burialwhere his mother resides. Speakman was taken to the residence of Mrs. Maria Woodleynear Lynchburg in this county where he lived before he enlisted.

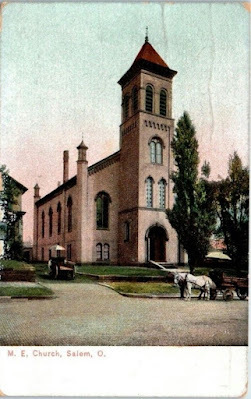

Methodist Episcopal Church

Methodist Episcopal ChurchSalem, Ohio

Local History Collection

Salem Public Library

The funeral services of Hale and Bull took place at theMethodist Episcopal Church on Broadway at 10 o’clock on Thursday the 22ndinstant. The hour appointed for the meeting at the church was announced by theringing of the town bell which was afterwards tolled during the services at thechurch. The principal stores and places of business were closed. The largeaudience chamber of the church was filled at an early hour by our citizens whoevidenced by their presence that this sad occasion was not a private but apublic grief.

The exercises commenced by singing an appropriate hymnfollowed by prayer by Reverend Stevens, and a sermon preached by Reverend C.H.Jackson from the 3rd chapter of 1st Corinthians, 22ndand 23rd verses, which read as follows, “Whether Paul or Apollos orCephas or the world, or life, or death, or things present, or things to come,are all yours. And you are Christ’s and Christ is God’s.”

We should like to have given a portion at least of the remarksmade on this occasion but we are unable to do so. Suffice it to say that thesermon was one worthy in every respect of the time and place. At the close ofRev. Jackson’s remarks, Rev. Stevens narrated the following incidents relatingto the death of these young men as told him by Mr. Hudson who learned the factsfrom their officers and companions in battle. After the recital of theseincidents, a song was sung by the choir befitting the occasion. Thecongregation then formed in procession and took at last view of the departedheroes. They were both buried in the cemetery.

Source:

“From theBattlefield,” Salem Republican (Ohio), January 28, 1863, pg. 2

October 11, 2025

A Ticket to Texas: Colonel Rutishauser's Travails at Camp Ford

Captured in the aftermath of the City Belle disaster in May 1864, Lieutenant Colonel Isaac Rutishauser of the 58th Illinois described the elation of his Confederate captors in the aftermath of their successes against General Nathaniel Banks' army.

"They took us to their camp, which was more like a bandit camp, such as I had seen in Italy in previous years, than a military camp," he relayed. "Here I was immediately surrounded by several Rebel officers, all of whom expressed their joy at their victory, which they had just achieved over Banks's mistakes. They mocked this general, called him their commissary, and claimed to have cut off and surrounded the Union army in Alexandria and could now starve them out."

And so began the colonel's lengthy imprisonment; eventually he would be delivered to Camp Ford, Texas, and remained there for nearly six months. Lieutenant Colonel Rutishauser’s account first sawpublication in the November 16, 1864, edition of the Illinois Staats-Zeitungpublished in Chicago. Special thanks to friend of the blog Randy Gilbert whodiscovered and translated this letter from its original German (in fraktur typeno less!) and to Vicki Betts who assisted with the translation.

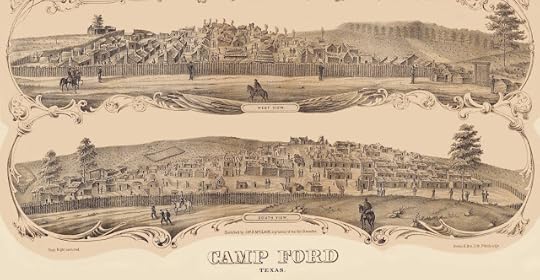

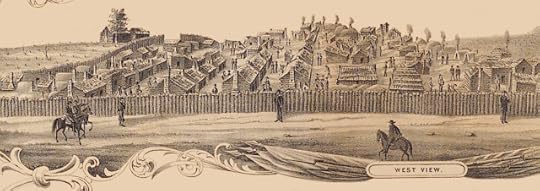

This depiction of Camp Ford, Texas was drawn by James McLain of the 120th Ohio, a fellow prisoner captured during the City Belle Disaster. (Courtesy of Randy Gilbert)

This depiction of Camp Ford, Texas was drawn by James McLain of the 120th Ohio, a fellow prisoner captured during the City Belle Disaster. (Courtesy of Randy Gilbert)

The brave Lt. Col. Rutishauser of the 58th Illinois Regiment,who was taken prisoner by the Rebels on the Red River last May, and wasrecently exchanged, has shared with us the following interesting account of hisexperiences in the South.

To theeditors of the Illinois State newspaper,

Please allow me to give you a brief account of my capture andmy fellow prisoners' experiences in Texas.

On February7, I was released from McPherson Hospital in Vicksburg with a leave of absence.After recovering somewhat from my illness, I went to Cairo, where I reportedfor duty on April 11to General [Mason] Brayman, commander of the Cairo District, and receivedorders to wait for my regiment, which had been reassigned with the 16thArmy Corps and was not easily accessible to me, as it was in Louisiana.

On the 25th, I reported to General [Stephen] Hurlbut,the corps commander, and received orders and transportation from him, but noopportunity to join the regiment.Three days later, an important dispatch arrived from Washington for General [Nathaniel]Banks and Commodore [David D.] Porter, and I was entrusted with its delivery. Itherefore left Cairo on April 29, and upon arriving in Memphis, by order ofGeneral [Cadwallader C.] Washburn, was given the gunboat Monank (Monarch?)at my disposal. On May 3, I advanced with it to about 30 miles belowAlexandria, when the commander informed me that he could go no further due tothe low water. I therefore considered it best to embark aboard the transportship City Belle, which was following us and had the 120thOhio Regiment on board, in order to deliver my dispatches to the scene.

Colonel Marcus Speigel

Colonel Marcus Speigel120th O.V.I.

However, I had barely been on the ship for 10 minutes when wewere suddenly subjected to heavy fire from artillery and small arms. The secondcannonball destroyed the pilothouse and killed the pilot, and the fourth destroyedthe steam boiler, rendering the ship unsteerable. Many soldiers jumped into theriver to swim to save themselves. The three colonels on board, [Marcus] Spiegelof the 120th Ohio Regiment, [John J.] Mudd of the 2nd IllinoisCavalry Regiment, and [Chauncy J.] Bassett of the 96th U.S. ColoredTroops were killed, along with many other soldiers.

The ship itself was swept ashore by the current on theopposite side of the enemy, whereupon I quickly crawled ashore and fluttered tothe hill under the fierce fire, but without being injured. The boat was sunkinto the shore.

After I wasout of the area of the fire, I destroyed my military orders as a dispatchcarrier and handed the dispatch itself to a private from the 120thOhio Regiment, whom I took along as a companion, intending to carry it on footto Alexandria. During the night, we followed the river for about 20 miles, butour hopes of reaching Alexandria were soon dashed when, unfortunately, weencountered a pile of cotton bales, behind which about 25 Rebels were hidden.They immediately captured us, set fire to the cotton, and marched back the sameway we came.

They took us to their camp, which was more like a banditcamp, such as I had seen in Italy in previous years, than a military camp. HereI was immediately surrounded by several Rebel officers, all of whom expressedtheir joy at their victory, which they had just achieved over Banks's mistakes.They mocked this general, called him their commissary, and claimed to have cutoff and surrounded the Union army in Alexandria and could now starve them out.On the same day, I was taken to Chennyville, but first I was joined by theprisoners of the 120th Ohio Regiment. After marching for seven daysthrough pine forests, bypassing Alexandria, we arrived in Nacatorche(Natchitoches) on May 10th, were transported by river to Shreveport, and fromthere, about 110 miles away, on foot to Camp Ford near Taylor (sic), Texas. Imyself had to be left behind in the so-called hospital in Marshall due toillness.

Detailed view of Camp Ford, Texas. Lt. Col. Rutishauser said that the name "camp" was a misnomer "for it was a six-acre cattle yard enclosed by tall, thick posts placed close together. The prisoners are driven into this enclosure like a herd of cattle and there they are left to make their own beds on the ground as best they can." (Courtesy of Randy Gilbert)

Detailed view of Camp Ford, Texas. Lt. Col. Rutishauser said that the name "camp" was a misnomer "for it was a six-acre cattle yard enclosed by tall, thick posts placed close together. The prisoners are driven into this enclosure like a herd of cattle and there they are left to make their own beds on the ground as best they can." (Courtesy of Randy Gilbert)After three weeks, and before I had recovered, I, too, had tomarch to Tyler, accompanied by a captured staff officer from General Banks,despite my protests and citing my poor health. Arriving at the camp, I foundthe captured officer prisoners of the 120th Ohio Regiment in a hutthat they had built themselves out of wood and that offered protection from theburning sun's rays, but not from storms and rain.

I am incorrectly using the name "camp" here todescribe the place where we were imprisoned, although it does not deserve it,for it was a six-acre cattle yard enclosed by tall, thick posts placed closetogether. The prisoners are driven into this enclosure like a herd of cattle,and there they are left to make their own beds on the ground as best they can.The camp commander showed so much humanity that he allowed the prisoners, underguard, to fetch bushes and shrubs from the nearby forest so that they couldobtain some protection from the heat of the sun. This humanity, however, wasvery cheap, and in his other treatment of the prisoners, he was so inhumanethat he had some of them shot dead from outside the enclosure without theslightest cause. He is also the author of the order that authorizes any Rebelsoldier or citizen to shoot at will any Union prisoner attempting to escape.

Before I speak further about this enclosure, I must return toour marches. For two days we had nothing to eat except a small so-calledbiscuit, a tuber kneaded together from water and flour. Later, we were givencorn flour in very small quantities and quality. However, since we had nocooking utensils, each of us provided himself with a board on which the flourwas mixed with water in the evening and roasted over the fire without salt.Finally, pork and beef were also delivered, which we stuck on sharpened twigsand roasted over the fire. At night, we slept without shelter, most of uswithout blankets, on the bare ground. I myself was fortunate enough to keep mywatch, which I bartered with a Rebel soldier after a few days for a usedblanket that had been taken from under a horse's saddle. My money was stolen bya Rebel guard on the very first night, as I fell asleep after a weary march.The thief, who returned the empty wallet to me, received no reprimand from hiscommanding officer, Captain Hendriks, 6th Texas Cavalry Regiment,when I complained to him.

The Ohioans fared no better; the night before we arrived atcamp, they were combed and searched by the Rebel guards, and under threat ofbeing shot if they resisted being plundered. At Camp Ford, the men are providedwith cornmeal and beef, which is distributed equally. This, apart from a littlesalt, is the only food available, and it is therefore no wonder that thehospital is full and the sick roam the camp by the hundreds. The prisonerscannot procure vegetables, for even if they have money, access to theseprovisions is blocked. I myself was once granted the privilege of receiving anorder allowing me to bring two watermelons into camp for my own use.

However, afew prisoners of Irish descent, who enjoyed the favor of Colonel Border, wereonce granted the privilege of trading in foodstuffs subject to a tax of 25percent of the value. This tax, it was said, was intended to benefit thehospital. The Rebel Dr. [Thomas W.] Meagher of Tyler, who was in charge of theoperation, never received any of it, so it can only be assumed that the colonelused the money for his own purposes. Mycomrades in the field will do well to remember the names of Colonel J.P. Borderand his adjutant, B.W. McEachem, both of whom treated the prisoners in the mostoutrageous manner, so that if they ever get hold of them, they can pay them inkind.

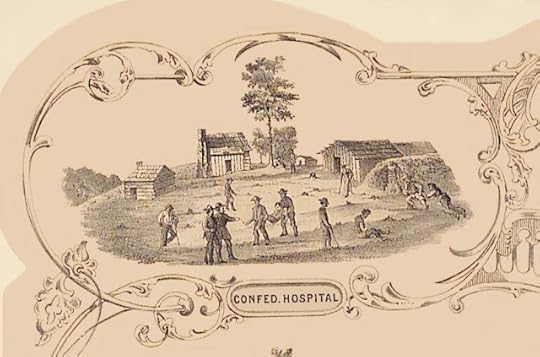

The hospital at Camp Ford as drawn by James McLain of the 120th Ohio

The hospital at Camp Ford as drawn by James McLain of the 120th OhioFrom time to time, some wheat flour also arrived at the camp.It cost 50 cents in greenbacks per pound. Sugar cost $1.75 per pound, pork$1.00, butter $1.75 per pound, a gallon of molasses $6.50 per pound, a quart ofmilk $1.00, and onions $1.00 per dozen. For several days, Col. [George] Sweet [15thTexas Cavalry] has been the post commander. He asked me to take over thesupervision of the camp and gave me the necessary orders. I devoted myattention to cleaning the camp in a military manner, which mainly improved thehealth of the people. I visited the sick, tried to cheer them up, and gave themmy advice as best I could. This is about all that can be done for them. We haveno proper doctors there; The few gentlemen who consider themselves such, butwho understand nothing of medicine, contribute not a little to the increase inthe number of burial mounds. Medicines are also in short supply.

During the course of my duties, I monitored the supply ofrations and discovered a deficit of 8,287 corn meal rations for 3,070 men in 17days. Considering the quality of this food, it is easy to see that theprisoners must have suffered greatly from such deception. I lodged a complaintagainst this injustice and thereby somewhat improved our situation, but I couldnot prevent us from later being given unmilled corn when the mill broke down.Fortunately, we had some good craftsmen among us, whom I immediately employedto repair the mill to protect us from starvation.

Col. Sweet allowed some of his men to go into the woods withthe prisoners to gather brush for the camp and huts, but after a few days, thisprivilege was revoked, as it was considered too inconvenient for the guards toconstantly run into the woods. Indeed, it required the service of two men fortwo hours a day to enable the poor prisoners to seek shelter from the burningsun and the rain, and to grant this is too generous. Such conduct exposes themen's lies when they excuse themselves for not being able to treat ourprisoners better and pretend to give them what they have.

I was almost overwhelmed by my duty, in which I could not beof any significant use to my fellow sufferers, and therefore submitted myresignation, which was granted. It is a sad sight to see about 3,000 men,mostly without blankets, in ragged clothing, and fed as described above,crammed in as we were. Therefore, no words can describe the joy I and 600 of myfellow prisoners felt when we left the camp on October 1st to beexchanged. On the way to Shreveport, we met a wagon train containing clothingand blankets for 1,200 men, which our government, accompanied by two Unionofficers, sent through the Rebel lines to our prisoners. These items will warmnot only many a body this winter, but also many a heart at Camp Ford.

With the 600 lucky ones, I traveled on foot, but at a lightpace, to Shreveport. Here, part of the crew was sent by boat and another partby land to Alexandria. It took us no less than 21 days to reach the mouth ofthe Red River, where we were exchanged. I need not describe the feelingsaroused in the people by the sight of the Star-Spangled Banner. The poor souls,almost all of whom were half-naked and barefoot, were reclothed in New Orleansand thoroughly enjoyed Uncle Sam's hearty rations, so that they would soon beable to devote their services to the country again.

I.Rutishauser, Lieut. Colonel, 58th Illinois Regiment

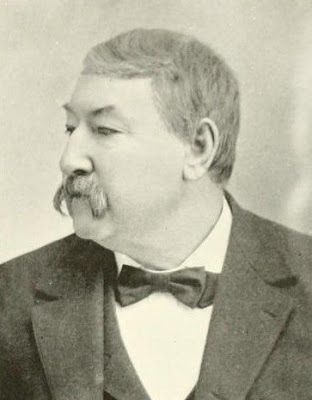

Isaac Rutishauser (Rutishowser/Rutsehaucer) was born 18 July1810 in Amriswil, Switzerland, emigrated to the US in the late 1850's and wasnaturalized on October 17, 1859. The 1860 census shows him as a saloon keeperresiding in Somonauk, Illinois, a village in northcentral Illinois west ofChicago. He was commissioned lieutenant colonel of the 58th Illinoison January 25, 1862, and saw action at Fort Donelson, Shiloh, Iuka, andMississippi. “For a long time, he was well and favorably known among our Germanpopulation,” the Chicago Tribune noted. “He was a brave and fearlesssoldier and at the battle of Shiloh he was wounded, taken prisoner, and held sixmonths before he was exchanged.”

The 58th Illinois saw service in the Red River campaignwhen Lt. Col. Rutishauser was trying to join them; this led to his capture May3, 1864. Following his release from Camp Ford on October 1, 1864, he wasdischarged January 27, 1865. “In 1865, he was appointed an Internal RevenueInspector and was legislated out of office in 1869,” the Tribune stated.“In 1873, he was appointed a Gauger which position he filled until 1876 whenthe whiskey troubles culminated. For 4 months past he had been employed in thepost office and had resigned his place, the resignation to have taken place fromthe 1st of November.” He collapsed of apoplexy and died October 23, 1878,in Chicago in the Grand Pacific cigar store of his son-in-law Louis Schaffnerand is buried at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago.

To learnmore about the loss of the City Belle which led to Lt. Col. Rutishauser’scapture, click here to read Captain James Taylor’s account in “Disaster atSnaggy Point with the 120th Ohio.”

Sources:

Letter fromLieutenant Colonel Isaac Rutishauser, 58th Illinois VolunteerInfantry, Illinois Statts-Zeitung (Chicago, Illinois), November 16,1864, pg. 1

“IsaacRutishauser,” Chicago Tribune (Illinois), October 24, 1878, pg. 8

“SuddenDeath of a Well-Known Citizen, Chicago Inter Ocean (Illinois), October24, 1878, pg. 8

The 157th New York and Dingle's Mill: A Final Fight in South Carolina

On one of the last days of the Civil War, Captain William Saxton of the 157th New York recorded his impressions of the April 9, 1865, fight at Dingle's Mill, South Carolina. His regiment, formerly part of the 11th Corps, had been pummeled at both Chancellorsville and Gettysburg before being sent to South Carolina in the summer of 1863. They were a veteran unit and when they deployed through the swamp at Dingle's Mill, Captain Saxton spied a pair of Confederate artillery pieces in his front and resolved to take them.

"I immediately formed my company in line, a few of the 56th New York boys falling in line with me, and marched them hurriedly to the edge of the woods, showed them the guns, then said, “Boys, let’s take them. Now, every man for himself as fast as you can go. Forward march!” And away we went. How rapidly a man’s thoughts will come to him under certain circumstances. I remember I thought as we were running forward that the muzzles of those guns were large enough for one to crawl into and I expected every second to see them fire into our faces. The distance was perhaps 200 yards but the Johnnies had gotten scared and attempted to hitch their horses to those guns and haul them off, but we were too near them and they cut the traces of those that were hitched and away they went. Their traces were cotton ropes. Some ran up the road west, some climbed the road fence and scattered into a field north. A squad of cavalry was in the road only a few rods away and as we rushed over that little fort, they all fled up the road. I was among the first to arrive and shook hands with one of the 56th New York boys across one of the cannons," he wrote.

These diary entries from Captain William Saxton, Co. C, 157th N.Y. saw publication in the January 17 & 24, 1902, editions of the Edgar Post published in Edgar, Nebraska.

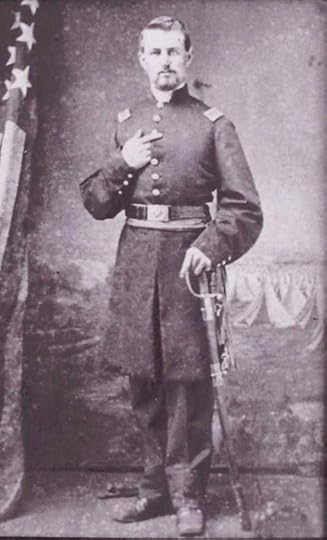

Captain William Saxton, Co. C, 157th New York Volunteers was a veteran of hard fighting at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg as well as service in South Carolina and along the Florida coast. The April 9, 1865, fight at Dingle's Mill near Sumter, South Carolina was the regiment's last engagement of the Civil War.

Captain William Saxton, Co. C, 157th New York Volunteers was a veteran of hard fighting at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg as well as service in South Carolina and along the Florida coast. The April 9, 1865, fight at Dingle's Mill near Sumter, South Carolina was the regiment's last engagement of the Civil War.

April 5, 1865: GeneralE.E. Potter was in command of this provisional division which was composed oftwo brigades. Adjutant Baldwin of our regiment was A.A.A.G. and LieutenantCampbell was acting ordnance officer on General Potter’s staff. The firstbrigade was commanded by Colonel Brown of our regiment; the second brigade byColonel Edward N. Hallowell of the 54th Massachusetts.

Two companiesof our regiment were left at Georgetown under command of Major Place to guardthe post and the two companies (B and D) of the 56th New York wereassigned to duty with us and Lieutenant Colonel Carmichael commanded theregiment. The provisional division consisted of about 4,000 men of allbranches, infantry, artillery, and cavalry.

At 8 a.m., thecolumn started and marched northwest parallel to and south of the Black Riverthrough a level wooded country towards Kingstree. Before going far, the columnwas halted and all who thought they would not be able to endure a long marchwere allowed to return to Georgetown. We made a march of about 18 miles thatnight and at night three or four Rebels were captured by our pickets.

April 6, 1865: Startedat 6:30 [a.m.] and marched through the same kind of country. The weather isgetting hot again. Camp near the Black River about seven miles from Kingstree,having marched about 20 miles. I was brigade officer of the day and had chargeof the pickets at night.

April 7, 1865: On themove again at 7:30 [a.m.]. The Johnnies are accumulating in our front andharass us a little. They burned the bridge over Black River at Kingstree. Wekept to the left and passed Kingstree on our right, marching toward Sumter. Thecountry is more open and a wealthier class of people live here when they are athome. Camped ten miles beyond Kingstree.

April 8, 1865: Startedat the usual hour, 6:30 [a.m.] in the rain bit it cleared off before noon.Marched 20 miles, forded two streams, and camped at night near the littlesummer village of Manning. A dastardly act was committed here by the enemy’scavalry. We had a small detachment of the 4th Massachusetts Cavalryalong with us. In coming into the village on the advance, this squad of cavalrychased the Rebel cavalry out. One of the Rebels, finding himself hotly pressed,turned and held up his hands in token of surrender. Private Elias B. Pratt ofCo. C advanced to receive him and, anticipating no danger, when nearly to hisside the Rebel dropped his hands, seized his revolver, and shot Pratt in theface, killing him instantly. The Rebel then put the spurs to his horse andescaped. In the running fight that ensured, one of the Johnnie’s saddles wasemptied. This was the most dastardly act that came within my personal knowledgeduring the war.

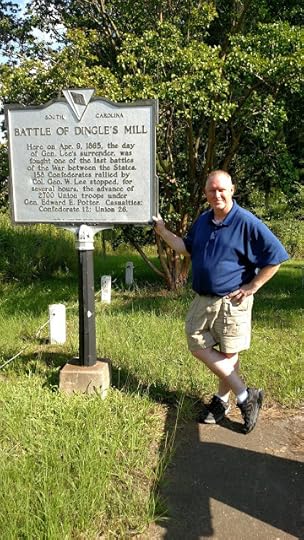

These are two cannons placed in their approximate positions at Dingle's Mill, an almost forgotten battlefield near Sumter, South Carolina. I visited the site, along along SC 521, in June of 2020.

These are two cannons placed in their approximate positions at Dingle's Mill, an almost forgotten battlefield near Sumter, South Carolina. I visited the site, along along SC 521, in June of 2020. April 9, 1865: Startedat 6:30 [a.m.] and marched rapidly all the forenoon. A number of cotton ginsand pressed were burned en route. We marched 14 miles in the forenoon and atnoon came to Dingle’s Mill where the road crossed a wide swamp with a streamflowing through the middle. The Rebels had town up the bridge across thisstream and flooded the swamp by cutting the dam to the right of the road. Theyhad erected a redoubt on a little rise of ground across the road on the westside of the swamp and as we approached, they sent a few solid shots across atus. General Potter halted the column out of range and gave the tired troops achance to eat their dinners.

After an hour’snooning, the 157th New York and 107th Ohio were ordered to flank the Johnnies out of their chosen position. ColonelCarmichael took our regiment and the two companies of the 56th NewYork to the left about a fourth of a mile and then turned west, parallel to theroad, marched down to the edge of that thickly wooded tangled swamp, halted,and had the officer’s call sounded.

He then toldus that we were to wade through that swamp and drive the enemy from theirposition. He said according to the best information obtainable; the swamp wasfrom a mile to a mile and a half in width and in places it would be waist deep.He instructed the company commanders to see that the men kept their ammunitiondry and have it ready for immediate use.

The difficultiesin crossing the swamp under the most favorable circumstances would requireconsiderable time and of necessity the regiment would become considerablystrung out as we would march by column of fours, left in front. If the enemystubbornly resisted our advance, it would take still longer time. In that swampand woods it would be impossible for the commander of the regiment to have aneye on the whole command and therefore each company commander (and especiallythose in the rear) must see to his own company. When we struck the hard groundon the other side, each must handle it as his best judgment would indicatewould be best in routing the enemy.

The order toadvance was then given. The marching of the regiment left in front brought Co.I in the lead and I do not recollect the order in which the other companiescame. My company was near the rear of the column, the two companies of the 56thNew York were ahead of me. As we entered the chilly waters of that swamp, whata shudder ran through our bodies! It was a dense wood with fallen logs andunderbrush with innumerable climbing, clinging, thorny vines extending from thelimbs of the trees to the ground. The natural obstructions to our progress weregreat and as before stated, the swamp had been flooded and the water and mirewere from knee to thigh deep as we floundered along.

Our progresswas naturally slow and the distance seemed longer than it actually was. Sometimearound 4 o’clock Co. I ran afoul of the enemy’s skirmishers along the edge ofthe woods on the west side and the firing at once became rapid and severe. Asthe head of the column emerged from the swamp while still in the woods, itdeflected to the right towards the road. Word was passed back for the othercompanies to hurry up as fast as possible; the firing all the time becomingmore rapid as the companies came out.

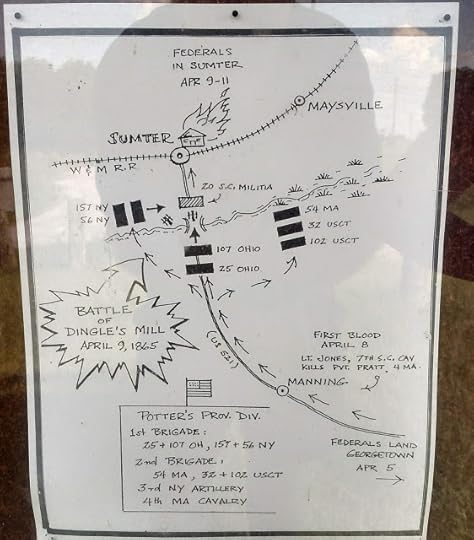

Map of the Battle of Dingle's Mill; the 157th New York hit the left flank of the 20th South Carolina Militia, perhaps 200 men in all.

Map of the Battle of Dingle's Mill; the 157th New York hit the left flank of the 20th South Carolina Militia, perhaps 200 men in all. When I struckthe solid ground with Co. C, I advanced to the edge of the woods west and sawacross an open field the earthwork referred to on a little knoll in the roadwith two pieces of cannon mounted in it. I saw at once (or thought I saw) if Icould form my company and charge across this field, I could take them in theflank and capture that battery before they could turn the pieces on us. I wouldbe charging along the hypotenuse of a triangle, the road being theperpendicular and the edge of the swamp along which the forward companies hadturned to the right being the short side.

I immediatelyformed my company in line, a few of the 56th New York boys fallingin line with me, and marched them hurriedly to the edge of the woods, showedthem the guns, then said, “Boys, let’s take them. Now, every man for himself asfast as you can go. Forward march!” And away we went. How rapidly a man’sthoughts will come to him under certain circumstances. I remember I thought aswe were running forward that the muzzles of those guns were large enough forone to crawl into and I expected every second to see them fire into our faces.

The distance was perhaps 200yards but the Johnnies had gotten scared and attempted to hitch their horses tothose guns and haul them off, but we were too near them and they cut the tracesof those that were hitched and away they went. Their traces were cotton ropes.Some ran up the road west, some climbed the road fence and scattered into afield north. A squad of cavalry was in the road only a few rods away and as werushed over that little fort, they all fled up the road. I was among the firstto arrive and shook hands with one of the 56th New York boys acrossone of the cannons.

We did not stop but for a momentin the redoubt. I rushed my men forward up the road a few hundred yards anddeployed them as skirmishers across the road and in the field to the north andsouth. As I was passing through the earthwork, one of my men picked up ablanket roll fastened with a shawl strap lying beside a dead lieutenant andhanded it to me saying, “Captain, this will keep you warm at night.” When Iunrolled that blanket, I found it was a lap robe, black on one side and greenon the other. I kept this and brought it home with me, using it for years. Ifound also in this roll a pair of cotton drawers and an undershirt which Igladly put on in exchange for the wet and muddy ones I was wearing. The rollalso contained a sick leave of absence signed by General Lee for thislieutenant. I kept this paper a long time and presume I now have it somewhereamong my papers but in the confusion incident to moving, I have mislaid it andcannot insert a copy of it here.

Yours truly at Dingle's Mill; signs on the site state to keep a close eye out for snakes but I never saw one, probably a good thing given my general distaste for reptiles.

Yours truly at Dingle's Mill; signs on the site state to keep a close eye out for snakes but I never saw one, probably a good thing given my general distaste for reptiles. Almost immediately after Co. Chad passed up the road, the other part of the regiment came charging up andcharged that battery again. In the fight of Dingle’s Mill or Sumter, Co. I borethe brunt of the fighting. Our regiment suffered 10 casualties, the 56thNew York, 15 and the 107th Ohio another 11. I have no means ofknowing what loss we inflicted on the enemy but presume their loss was not sogreat as they had the advantage of us, fighting on the defensive, and wereprepared to fire on the head of our column as it emerged from the swamp. TheRebel lieutenant in command of the battery was killed and left in the redoubt. Wecaptured the two pieces of artillery with ammunition and took them along withus, having them to use during the entire expedition, and took them back toGeorgetown with us and turned them over to the government.

After taking possession of theartillery, we marched on and after dark camped in Sumter, the county seat ofSumter County. The citizens had planned to give their boys a banquet after theyhad driven the invading Yankees back, but some of those refreshments foundtheir way into the empty stomachs of those invading Yankees. The boys capturedlarge quantities of peanuts and cigars.

During the 10th ofApril, the command remained in the city. E.H. Smith of Co. D, 56thN.Y. went into the printing office, set up, and printed a one sheet paper whichhe called The Banner of Freedom dated Sumter, S.C., Monday morning,April 10, 1865. Among the items in this paper was an article entitled “Acts ofBravery” from which I quote:

“In the affairs of yesterday, agallant act of bravery was performed which is worthy of commendation. When theorder to charge and capture the Rebel battery was given, Private Nathan Morseof Co. D, 56th N.Y. advanced ahead of his company on a keen run,scaled the breastwork which concealed the artillery, found four Rebels in thefort and ordered them to surrender, which they did. Captain Saxton of Co. C,157th N.Y. was the next to scale the earthwork and he and PrivateMorse shook hands across the guns. They were all the time exposed to themusketry of the enemy and liable to be captured at any moment as the Rebelcavalry were only a few yards to their left. Both escaped.”

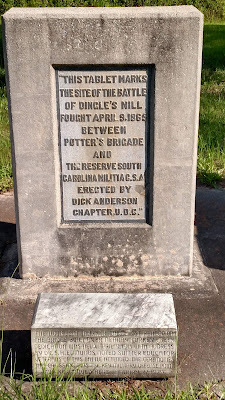

United Daughters of the Confederacy marker at Dingle's Mill.

United Daughters of the Confederacy marker at Dingle's Mill. In an editorial under the headof “The Duties of the Hour,” an address was made to the citizens of Sumter andto the whole state at large setting before them the fact that they had failedin their attempt to destroy the union by seceding therefrom. That they hadfought well and bravely, worthy of a better cause, but now they were beaten andthe union would be preserved. How would they accept the inevitable? They wereexhorted to take a common sense view of their conditions and yield gracefullyto the authority of the United States. It was believed if they would sue tocome back under the protecting folds of the stars and stripes and makeapplication for protection to the commander of the department, a guard would begranted them which would secure their persons and property against allguerillas or others who might seek to take advantage of the times to injurethem. A goodly number of copies of this paper were printed and distributed tothe houses of the city.

Sources:

War Reminiscences of Captain William Saxton, Co. C, 157thNew York Volunteer Infantry, Edgar Post (Nebraska), January 17, 1902,pg. 1; also, January 24, 1902, pg. 1

September 28, 2025

Nothing to Bind Us But Honor: In the Three-Months’ Service with the 87th Ohio

There isn't much written about the wartime services of the 87th Ohio Volunteers. Mustered into service in the summer of 1862 for just a brief 90-days, the regiment first guarded prisoners at Camp Chase before being sent to Baltimore, Maryland where it took part in the 4th of July celebration. A few days later, it was sent to Harper's Ferry where it became part of the garrison.

We are fortunate in that Private William A. Bosworth of Co. A, a student of Marietta College, provided the following lengthy description of the travails of the 87th to the August 22,1862, edition of the Pomeroy Weekly Telegraph. About 5 weeks after hewrote his letter, the 87th Ohio would be surrendered as part of thegarrison of Harper’s Ferry.

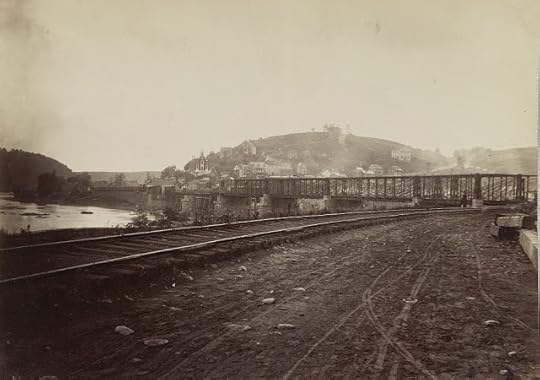

Maryland Heights as viewed from Harper's Ferry during the Civil War.

Maryland Heights as viewed from Harper's Ferry during the Civil War. Bowery Lane,Camp Banning, Harper’s Ferry, Virginia

August 4,1862

Being almost the sole representative ofold Meigs in the three months’ service and being connected with a regimentwhich has seen very many of the enjoyments and few of the hardships of soldiers’life, I may contribute my mite towards encouraging our boys to volunteer bygiving your readers a sketch of our adventures for the past two months.

When Governor Tod issued his call forvolunteers to serve for a limited period during the storm that seemed tothreaten our capitol, the citizens of Washington County called together by thepromptness and energy of Judge Putnam, chairman of the military committee, heldan enthusiastic meeting at which some 40-50 names were enrolled for 60 days.The students of Marietta College assembling at the courthouse with thecitizens, at a preconcerted signal, adjourned en masse to the College Chapelwhere after a brief deliberation, they agreed almost unanimously to holdthemselves in readiness to go.

The next day, when it was learned thatthe emergency was not so great as before supposed and that men would not beaccepted for less than 90 days, many though that duty did not call them to go.Nevertheless, we had quite a respectable company raised by night and the nextafternoon (Wednesday May 28) we started with about 75 men up the MuskingumRiver en route for Camp Chase.

I could hardly entertain you be describingat any length our trip to Columbus; I will only say that we had a pleasantjourney, finding amusement in responding to the cheers and waving ofhandkerchiefs that greeted us all along the way and withal feeling quite braveand patriotic as we attacked with valorous appetites the tables loaded withcrackers, cheese, and prime ham. We arrived at Columbus late Thursday eveningand marched up to the State House where we listened to a nice little speechfrom the governor, then marched back to the lunch of crackers and hot coffeewith quarters of the floors of an unoccupied tavern stand.

The next day, we took up quarters atCamp Chase and spent the first two weeks of our stay there in recruiting,organizing, arguing, and quarreling generally. We had come to camp entirelyunorganized and in fact, not regularly enlisted having nothing to bind us buthonor. In his call, the governor offered the choice of either going to protectWashington or remaining at Camp Chase to relieve troops doing guard duty. Thegreater portion of us, incited by a love of travel and adventure and willing toundergo danger if need be for our country, enlisted with the former intention.

But we had a few timid ones and anumber of boys who were bound by promises to their parents who intended tochoose the latter alternative. We gathered, however, from certain hints droppedby the governor that old Uncle Samuel had been more scared than hurry and thatthe dilemma now would be either to enter the general service, subject to theorders of the War Department, or the state service to be under the control ofthe governor. About three-fourths of our boys were still in favor of thegeneral service, but being induced by the persuasion of Judge Putnam and inorder to keep our company together, we at length reluctantly consented to enterthe state service and became Co. C of the 85th Ohio. We remained inthe 85th two weeks longer, making four weeks in the state service.

I presume Camp Chase is about as gooda camp as any similar one where large bodies of men congregate, though I shouldby no means recommend it as a place of summer resort. We had pretty goodshanties, very fair soldier’s grub, and the camp was well-policed but theground being bare, hard, and destitute of trees, the heat became veryoppressive when hot days did come which, thank heaven, were comparatively fewfor the season. The dust raised by the slightest breeze from the broad, flatparade ground, swept in almost blinding clouds; when the wind blew hard, thedust penetrated every crevice and cranny of our shanties. Just multiply thedust of Pomeroy by three and you will have about the product of camp Chase. Thewater, though not positively unwholesome, was not good, being strongly impregnatedwith sulfur.

Colonel Henry Banning

Colonel Henry Banning87th and 121st Ohio

There were about 1,200-1,400 prisonersat Camp Chase. The prisons in which these men are confined are merely portionsof the camp enclosed by a close board fence 20 feet high with a walk near thetop for the guards. Our principal business at Camp Chase was, of course, toguard these prisoners- that is, to walk back and forth with a loaded guncarried in military position and keep them from coming within 10 feet of thefence. Such is the glory of state service. Among these prisoners may be foundall varieties of character from the wealthy and courteous Southern gentlemen tothe degraded ragamuffin bushwhacker. They all seem to be quiet and orderly withfew and occasional exceptions.

We soon became tired of this kind ofservice and when the opportunity of transfer was offered, about 20 of our menfrom the 85th and as many recruits we became Co. A of the 87thOhio. Our regiment was organized and ready for the march in a few days and onSunday morning, we started from camp under marching orders for AnnapolisJunction, Maryland.

Saturday afternoon we cooked our fiveday’s rations and got our troops ready. We awoke at 2 a.m. and were ready tomarch by 4. Marching from Camp Chase to Columbus for five miles was our firstand only hard march. I can assure the unsophisticated that even a five-miletramp with full knapsacks, five day’s rations, a gun, and ammunition to carryis not to be sneered at. I would as soon go 20 miles unencumbered. However, theboys bore up bravely and stepped firmly to the music as we passed through thestreets of Columbus.

We took the Ohio Central Railroad forPittsburg. What we most observed as we passed through the state was the numberand beauty of the ladies. At Newcomerstown, a mere village, there was a fullcompany of young ladies- a fine chance for young Benedicts. I suppose a portionof this praise of Ohio girls is owing to the fact that it was Sunday and thegirls were all out in their holiday attire which we passed through Pennsylvaniaon a Monday, which was wash day.

At the city of Smoke and Cinderswhere, by the way, the women are as homely as the houses, we changed cars,taking the Pennsylvania Railroad. Soon we began to ascend the mountains- up,up, along the banks of the Connewaugh, then down the Blue Juniata. There weremany fine scenes for the artist’s pencil along this route. The weather was delightfullycool and pleasant and I feasted my eyes to the full upon the grand panoramafleeting by us. The scenery on this side of the mountains is especially grand.High peaks and ridges tower blue and cloud-like in the distance. Down below us,half hidden in the trees, winds the Juniata River of song and tradition whileall varieties of mountain scenery unite to complete the picture.

Among the numerous towns upon ourroute, I must not forget to mention Huntingdon where we stopped for two orthree hours and were plentifully supplied with first-rate bread and butterwhich the ladies brought by the basket full. Well do they emulate thepatriotism of their husbands, fathers, and brothers, three companies of whomare in the service. It is their custom thus to minister to the enjoyment of allthe soldiers who pass through. God bless them! May their joys ever be asabundant as their charity is bountiful.

We arrived at Baltimore, Marylandearly Wednesday morning; we got off the cars and unslung our knapsacks,expecting to take the train for Annapolis when the order came to encamp. In themidst of a cold, drizzling rain, we pitched our tents upon a vacant space atthe northern edge of the city which we christened Camp Tod. This camp was lowand hot, but still better than Camp Chase as we had splendid water nearby and acreek upon one side and an old reservoir upon another which afforded greatconveniences for washing and bathing. Then we had a fine opportunity of seeingthe city when we could get a pass.

We had halted at Baltimore for thepurpose of being on hand on the 4th of July in case of a riot. Letme describe our day. At 4:30, we routed out and marched to town without our breakfastsand around the Washington Monument while everybody was asleep but a fewNegroes, draymen, etc. Squad and company drill in the morning and in theafternoon our first battalion drill for about two hours. Then about 5 o’clockanother tramp down the stony streets in the broiling sun and around the bigpile of white rocks, taking off our hats and giving cheers cheer at everystripe of the red, white, and blue which we couldn’t see for the sweat that pouredoff our faces. I must confess that when Colonel [Henry] Banning made us alittle speech and told us this was the proudest day of his life, we felt verymuch like the frog in the fable although we cheered him, of course.

Harper's Ferry, Virginia

Harper's Ferry, Virginia On Wednesday July 9th wereceived marching orders again, this time for Harper’s Ferry. Three days ofrations to cook, another knapsack drill through Baltimore, a ride in the hogcars, and daylight finds us nearing Harper’s Ferry. As we turn a sharp curveapproaching this place, suddenly a most magnificent scene bursts upon thesight. Where the Potomac and Shenandoah unite their waters, they have cut adeep, narrow gorge through a ridge 700-800 feet high, leaving an almostperpendicular rocky wall upon either side. These rivers present quite asingular appearance. They are rather broad and quite swift, dotted thickly withrocks forming innumerable little water falls so that they presented a spottedappearance at a little distance. The scenery as you look up the Shenandoah isthe finest I ever beheld.

Again, in a drizzling rain we selectedour campground and pitched our tents. I will describe as well as I can oursituation and surroundings. Take as a starting point a street a mile in lengthrunning northeast and southwest through the towns of Harper’s Ferry andBolivar; the Ferry being at the northeast where this street divided the rightangle formed by the two rivers, the Potomac running east and the Shenandoahnorth. The town of Harper’s Ferry occupies the point formed by the rivers; theruins of the old arsenal buildings extending along both banks. Strongfortifications bristling with cannon extend across from stream to stream. Thetown of Bolivar is higher and extends along the street first mentioned. Here weare encamped about a mile from the Ferry in advance of the troops here.

Between us and the Potomac is a ridge. East across thePotomac from the Ferry are the Maryland Heights, halfway up which is a batteryof artillery with its guard of infantry. On the top of these heights is alookout built by the Secesh from which you can see the whole country for 20-30miles around. Ridges as high as our Pomeroy hills appear to be mereinequalities in the surface of a great valley which lies outstretched like amass at our feet. It is a view which will richly repay any one for the labor ofascent. South of us across the Shenandoah are the Louden Heights where we cansee some spiked guns, formerly a masked battery of our men. The troopsstationed here besides our men are the 12th and 22nd NewYork regiments, parts of a Maryland and Delaware regiment, and severalcompanies of artillery and cavalry.

We have had a good time since we have been here. Our camp isa very fine one with plenty of elbow room and a nice grassy drill ground. Whenwe first came to camp, we could get plenty of cherries from deserted premises.We now get apples and pears in the same way while picking blackberries andhuckleberries in the woods. For the past two weeks, our principal amusement hasbeen the construction of bowers of pine and cedar. I presume 10,000 loads ofbushes have been dragged into camp by our boys. We have built bowers in frontof all our quarters and fitted them up with seats and tables of Secesh boards.

We have built a tabernacle for meetings 40 feet by 80 feet,but the finest bower is one built by Co. A in front of the colonel’s quarters. Apine tree 8 inches in diameter is planted in the center, the upper boughs beingleft on; 8 smaller ones are set at equal distances from this, the raftersextended in a slanting direction to the center pole. Cross ticks are laid uponthese and the whole thickly covered with pine boughs. The center pole is finelyornamented with cedar full of berries and an octagonal seat is put up. Thestars and stripes float upon the top of the center pole.

The bowers of our company are constructed upon a similarpattern but are not so fancy. I do not suppose we suffer as much from the heatas you do at home. We have no drills now after 8 in the morning or before 6 inthe evening. The rest of the time we can spend in our arbors. Besides we are onpretty high ground and have a cool breeze almost all the time.

As to the drill of our regiment, I will only say that we werehighly complimented by both General Wool and Colonel Dixon Miles at the reviewof the troops stationed here. Everybody says we have made very great progressfor the time we have been in the service. We do not expect to see any fightingbefore our time is expired though our boys are ready and, in fact, ratheranxious for a fight. Colonel Miles says that though the New York boys arebetter drilled, he would depend principally upon us in an emergency.

Our staff officers are all good men and well liked. Colonel HenryBanning is a captain in the service on a three month furlough. He is a goodmilitary man, very kind and sociable, and thoughtful of the interests of hismen but still strict enough in discipline. Lieutenant Colonel John Faskin is aScotchman with a voice like a lion and an air of unflinching courage which hasbeen well-tried, too. He was an adjutant in the service [67th Ohio]and won laurels at Winchester. Major Leffingwell was in the Mexican War and isthe best drilled man of the three. Surgeon Barr from the 36th Ohiois a No. 1 physician.

Our regiment is to be reorganized whenour time is out. I suppose our friends will be anxious to know what we aregoing to do. It seems to be settled than unless an emergency arises, we are toremain where we are until our regiment is taken back to Ohio to be reorganized.Rumors, many tongued, daily brings as to the time of our return and the placeto which we will be taken. The latest authentic report is that we are goingback to Camp Chase the last of next week to be immediately discharged and amonth’s furlough given to those who reenlist. Our term of enlistment does notexpire until the 10th of September.

[As things turned out, the 87th Ohio did not reorganize, the men disgusted by the way in which they were caught up in the surrender of the Harper's Ferry garrison on September 15, 1862, 5 days after the expiration of their term of service. Upon their arrival as paroled prisoners of war at Camp Douglas in Chicago, the men successfully lobbied to be sent home to Ohio where they were mustered out in early October 1862. William's older brother Milton Bosworth served in the 53rd Ohio and died of disease in March 1863. After his service with the 87th Ohio, William became a minister and died in Kansas in 1936, aged 94.]

Source:

Letter fromPrivate William A. Bosworth, Co. A, 87th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, PomeroyWeekly Telegraph (Ohio), August 22, 1862, pg. 1

September 26, 2025

With the Pointe Coupee Battery at Nashville

Scramblingback to the Pointe Coupee Battery’s position after spying the advancingFederals closing in on them, Rene A. de Russy recalled the thrilling finalmoments before the battery was overrun on December 16, 1864, during the Battleof Nashville.

“The battery suffered severely, men and horses going down inthe turmoil, a caisson being blown to atoms and Edgar Gueson being cut in by ashell. Still, the battery held fast, even when the men to the left had brokenand when the Union men came around the hill on the flank. Gun after gun wasserved until human endurance could go no further. Then with aparting shot into the very faces of Thomas’s men, Corporal Joseph H. Vienne andhis fellows started back under orders from Captain Alcide Bouanchaud. CorporalVautier trained his gun upon Vienne’s captured piece but without avail and theorder came to withdraw, several of the pieces first being spiked. The membersof the battery then made for the Granny White Pike, leaving over 20 dead andwounded within less than 100 yards of their guns. From that time on, theretreat partook the nature of a route and “suave qui pent” was the watchword.”

De Russy’s account of the second dayof the Battle of Nashville first saw publication in the May 20, 1907, editionof the New Orleans Times-Democrat. The battery was part of Myrick’sArtillery Battalion which was attached to General William Loring’s division ofGeneral A.P. Stewart’s Corps.

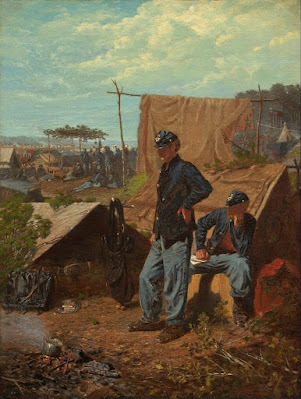

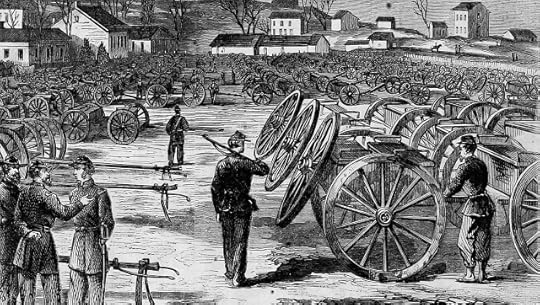

The spoils of war: the four 12-pdr Napoleons of the Pointe Coupee Battery are somewhere amidst this field of captured cannons and caissons gathered at General George H. Thomas's headquarters in Nashville in the days after the battle.

The spoils of war: the four 12-pdr Napoleons of the Pointe Coupee Battery are somewhere amidst this field of captured cannons and caissons gathered at General George H. Thomas's headquarters in Nashville in the days after the battle. At the opening of the second day’shostilities on December 16, 1864, the new line of the Confederates was locatedsome distance to the left of the Granny White Pike near the base of a high hillwith a running range of rock fence making a breastworks about four feet inheight and a range of trees skirting near the pike. The Pointe Coupee Batterywas the last battery near the base of the hill.

The Federal troops were extremelyactive and at times precipitated an onslaught which required a check from thebattery, driving the Union forces to shelter. Shortly before noon the rattle ofmusketry and the roar of half a hundred pieces of artillery gave notice thatthe Confederates on the right were engaged in a terrible battle and great wasthe suspense in the battery while awaiting news as to whether the tide ofbattle was running for or against the army. Could the old Army of Tennessee,with its thinned line, hold its own and gain further renown? This was thequestion that each man asked the other and the tension told on the nerves ofmany.

For three or four hours the battleraged and then came detachments of cavalry riding by, bringing the news thatthe day had been won for the Confederates and that Lee’s Corps had drivenThomas back in disorder and defeat. Thus encouraged, the Pointe Coupee Batterybraced itself with the rest of the wing for the general attack contemplated onthe front by the Union troops and awaited the onslaught of the seriedthousands.

In close marching columns the Federalscame forward, first opening on the Confederate skirmish lines and works withhalf a dozen batteries. On they came at the double quick for the Confederatebreastworks as the left wing of the Army of Tennessee braced to receive them.Out burst the blaze of the Confederate guns and the Federals paused in theirprogress and for a moment sought shelter, finding this cover behind a range ofhills which ran parallel with the Confederate lines.

Our battery was prominent in therepulse and performed its full share of the deeds of glory in the briefinterchange while General [William] Loring, but a short space distant, cheeredand waved his hat in encouragement. Noting that the Union forces had made anoblique move in their charge, the battery at once grasped the opportunitypresented and sent in heavy charges of grape with such telling effect that theright of the brigade was thrown into disorder and broke for cover with greatlythinned ranks.

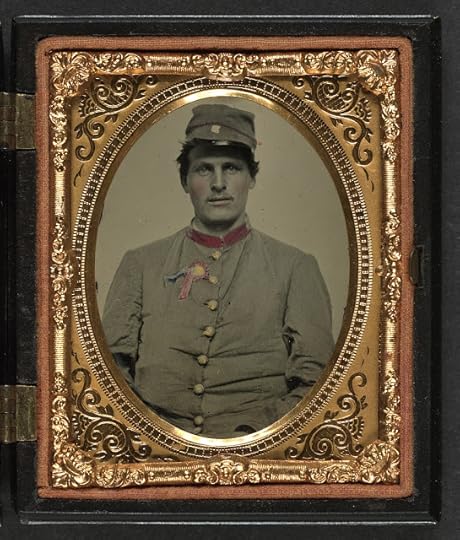

A proud Confederate artilleryman wearing a secession cockade.

A proud Confederate artilleryman wearing a secession cockade. Foiled in his first attempt, Thomaspaused and pondered, appreciating that direct attack was futile, and aretrograde movement took place with his forces. Taking advantage of the lull, Iclimbed a hill with some comrades intending to get a bird’s eye view of thesituation but was somewhat discouraged by the advent of a reckless shell whichdropped carelessly in my vicinity and dug a large hole in the hilltop. Beforewe could turn and flee, however, a second shell followed and decapitated ayoung Confederate, and warned the survivors that their range had been found bythe enemy.

Notwithstanding the shock of thisoccurrence, I with a friend from the battery threw ourselves on the ground andsquirmed to the edge of the hill where a view of over a mile stretched beforeus. Here we could see the moves and counter-moves of Thomas’s forces and theaddition of two batteries to the artillery gave us the realization that adesperate encounter was coming. Hardly had we rejoined our battery when GeneralHood rode up to General Loring and said, “General, if we can hold our line forhalf an hour or better, the victory will be ours.” His face was aglow with thebeam of hope and his eyes flashed with the fire of conflict; General Hoodpresented an inspiring sight to his soldiers and the Pointe Coupee Batterycheered him to the echo.

Then came the attack as Thomas’s armymoved onward. But, stubborn as was the onslaught, equally determined was thedefense and for hours the battle raged with blood flowing like water. Thebattery suffered severely, men and horses going down in the turmoil, a caissonbeing blown to atoms and Edgar Gueson being cut in by a shell. Still, thebattery held fast, even when the men to the left had broken and when the Unionmen came around the hill on the flank. Gun after gun was served until humanendurance could go no further.

Then with a parting shot into the very faces of Thomas’s men,Corporal Joseph H. Vienne and his fellows started back under orders from CaptainAlcide Bouanchaud. Corporal Vautier trained his gun upon Vienne’s capturedpiece but without avail and the order came to withdraw, several of the piecesfirst being spiked. The members of the battery then made for the Granny WhitePike, leaving over 20 dead and wounded within less than 100 yards of theirguns. From that time on, the retreat partook the nature of a route and “suavequi pent” was the watchword. That the defeat was a more bitter disappointmentto General Hood than the retreat at Moscow was to Bonaparte was the feelingwhich prevailed throughout the army. But the Pointe Coupee had fought the goodfight and had been faithful unto death.

To read more about the Battle of Nashville, please check out these posts:

The "Glory" Business: The 7th Minnesota at Nashville

William Keesy and the Battle of Nashville

A Carnival of Death: A Federal Officer's View of the Battle of Nashville (99th Ohio)The Troops Need Rest Very Much: A Confederate Reporter Writes After Nashville

Grab a Root! With the 111th Ohio at Nashville

Source:

“Record ofthe Pointe Coupee Battery in the Fierce Battle of Nashville,” Rene Amedee de Russy, New Orleans Time-Democrat (Louisiana), May 20, 1907, pg. 5

September 20, 2025

Picket Shots of Chickamauga with the Army of Tennessee

In "Picket Shots of Chickamauga" I'll share some of the shorter stories provided by veterans of the Chickamauga campaign that might not be long enough to constitute a blog post on their own, but make for insightful reading.

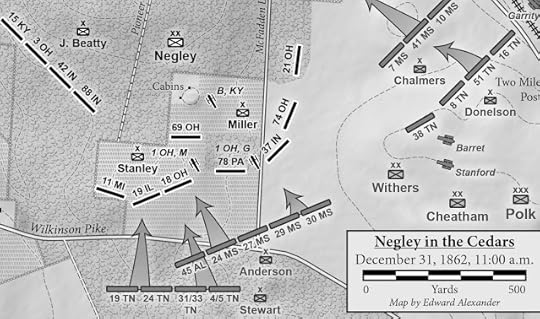

In commemoration of the 162nd anniversary of the second day of the battle, three accounts below give some perspectives from soldiers in the Army of Tennessee, including William Knight of the 36th Alabama who shares his memories of September 20th, George Jones war diary of Stanford's Mississippi Battery, and Captain John H. Martin of the 17th Georgia who 50 years later returns a corporal's commission he captured on the battlefield.

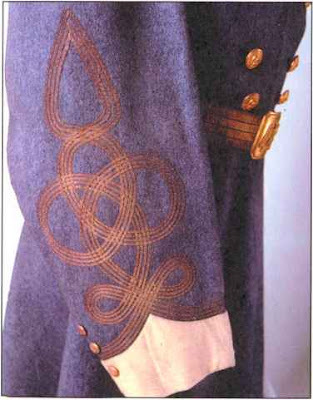

The detail of the lace on a uniform once worn by Lieutenant Braxton Bragg, commanding the Army of Tennessee at Chickamauga. The battle marked Bragg's one clear-cut victory over the Federals and it would be his last. His Army of Tennessee took enormous casualties defeating Rosey's bluecoats at Chickamauga and would be unable to full exploit that victory in the days afterwards. By the end of November, Bragg's army had been driven away from Chattanooga and Bragg asked to be relieved. Jefferson Davis finally agreed to do so.

The detail of the lace on a uniform once worn by Lieutenant Braxton Bragg, commanding the Army of Tennessee at Chickamauga. The battle marked Bragg's one clear-cut victory over the Federals and it would be his last. His Army of Tennessee took enormous casualties defeating Rosey's bluecoats at Chickamauga and would be unable to full exploit that victory in the days afterwards. By the end of November, Bragg's army had been driven away from Chattanooga and Bragg asked to be relieved. Jefferson Davis finally agreed to do so.

Alabama Volunteer Corps button

Alabama Volunteer Corps button

Chasing VanCleve’s Division in Clayton’s Alabama Brigade

The announcement of the death ofGeneral Henry D. Clayton vividly recalls to the mind of the writer the bloodyscenes of the Battle of Chickamauga where General Clayton fought so bravely anddistinguished himself so signally. The writer was a member of Co. C, 36thAlabama regiment but at this time was serving on General Clayton’s staff and isnow the only one of these staff officers that is left on this side of theriver.

His brigade was composed of the 18th,32nd, 36th, 38th, and 58th Alabamaregiment. The division was commanded by General Alexander P. Stewart ofTennessee. The battle was fought on the 17th, 18th, 19thand 20th days of September, 1863. During the last two days thehardest fighting was done and the heaviest losses sustained. Many of ourcompanies lost as many as 20 men and many of our bravest officers here pouredout their lifeblood. Among the number were Lt. Col. Richard Inge of the 18thAlabama and Major Jewett of the 38th. Lt. Col. Thomas H. Herndon wasseverely wounded and carried from the field.

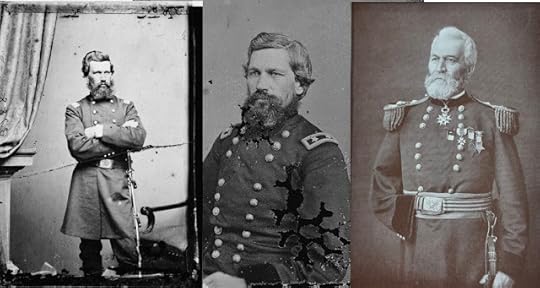

General A.P. Stewart

General A.P. Stewart"Old Straight"

On the 17th of Septemberthe first man was killed in the ranks of the 36th Alabama by acannon ball. The last charge was made on Sunday evening about 5 o’clock byClayton’s brigade on the division of Major General Van Cleve who was stronglyfortified behind a long line of breastworks constructed by cutting down largetrees. The charge resulted in a complete rout and almost entire capture of VanCleve’s division and ended the battle.

In the rear of van Cleve’s divisionwas a large old field and when the enemy were routed, this old field lookedlike a living mass of blue coats running pell-mell without regard to rank or file.It was here the gallant Clayton, followed by his staff and mounted men, dashedinto the midst and of the retreating mass and captured 4,000 prisoners; GeneralVan Cleve himself only escaping by possessing a fleeter horse than his pursuers,the officers of General Clayton’s staff. He finally reached the woods andsucceeded eluding us. I captured General Van Cleve’s portfolio, his papers, andphotograph, which I now have. I picked up on the battlefield a small bible withthe name of O.A. Mevis, St. Paul, Minnesota on one of the fly leaves and thefollowing epigraph: “The testament is of no force while the testator liveth.”If this soldier or any of his relatives are living and will write to me, I willgladly return it to them.

Source:

“Reminiscent:Recollections of Gen. H.D. Clayton at the Battle of Chickamauga,” CaptainWilliam N. Knight, Co. C, 36th Alabama Infantry, Troy Messenger(Alabama), November 7, 1889, pg. 1

Division commander General Benjamin F. Cheatham and his staff in an image dating from 1863.

Division commander General Benjamin F. Cheatham and his staff in an image dating from 1863. War Diary ofStanford’s Mississippi Battery

Monday,September 7, 1863:Orders to march at a moment’s warning. Baggage packed in wagon at 10a.m. Ordersat 3 p.m. to be at McFarland’s, a distance of two miles, at sunset.

Tuesday,September 8, 1863:We rested our bones on the roadside last night; our horses remained standing inharness, ready to move in a moment. We are dirty as hogs. We moved off thismorning at 9, marching slowly, very dusty; marched 6 miles to Spring Creek;bivouacked in a large open field.

Thursday,September 10, 1863:At 8 o’clock we moved out from camp and marched two miles on the road toMcFarland’s, placed the guns in position, ready in case of attack on this road.Moved again at 8 o’clock tonight, crossed Chickamauga Creek about 10 o’clock.We are closing in upon the enemy; wouldn’t be surprised at a hard-fought battleany moment. General Rosecrans is said to have about 70,000 men.

Friday,September 11, 1863:We remained standing in the road all last night; moved again at sunrise;marched to the town of Lafayette, Georgia. It is now 4 p.m. The male academy isjust to our left.

Saturday,September 12, 1863:On the road at daylight; marched north to Rock Spring Church, 8 miles fromLafayette. Took position on the right of the road. Orders to build no fires.

Sunday,September 13, 1863:We stood by our guns all night; moved forward at sunrise. We advanced two mileson the Chattanooga road beyond our regular line of battle and took positionwhen we were ordered to shell the woods. We fired 70 times and did some goodshooting. We located a 10-lb rifle battery; they opened upon us and some oftheir shots came very close to us but most went over us. We fell back to themain line at dark.

Monday,September 14, 1863:Fell back to Lafayette again. We are marching and countermarching.

Wednesday,September 16, 1863:Ordered out on the road at 4 p.m. and marched one-and-a-half miles. We are nowcooking two days’ rations.

Thursday,September 17, 1863: Marchedout on the Ringgold road. Bivouacked at 10 p.m.

Friday,September 18, 1863:Moved forward a short distance at daylight. Heavy skirmishing throughout theentire day. Orders to stand by our guns.

Saturday,September 19, 1863: Itis now a little after daylight. We are moving in line of battle. We crossed theChickamauga this morning at 9 o’clock, having driven the Yankees from their strongposition. It is now 10 o’clock and the battle is raging all along the line. Ourright center is about to give way. There seems to be a gap between the left ofCheatham’s division and Hood’s right. Stewart’s division with our battery areheld in reserve and now are ordered to fill the gap. Oh, how awful, howfearful! It seems to be death itself. Stewart is making a gallant charge. Hehas broken the enemy’s center and is pushing forward. We are now under a heavy enfiladingfire. Our battery attempted to take a new position on a knoll of a ridge alittle in advance of the regular line. Just as we got nearly to the top of theridge a perfect hail of Minie balls and shells poured in on us. Wecountermarched in double quick time. Captain [Thomas J.] Stanford said to stay would meandeath to the entire battery in five minutes. John McNeal and Robert Burt werebadly wounded. It is now 4 p.m. A general advance is being made on the entireline. Volley after volley of musketry and the grand booming of artillery areheard all along the line. The Yankees are falling back slowly. It is now nearlydark. By 8 p.m., we are bivouacking on the bloody battlefield. General PrestonSmith was killed about dark while leading his brigade in a gallant charge.

Source:

“Old Soldier’sDiary: Mr. Geo. W. Jones’ Reminiscences Make Interesting Reading for Everybody,”Sergeant George W. Jones, Stanford’s Mississippi Battery, Grenada Sentinel(Mississippi), October 1, 1898, pg. 8

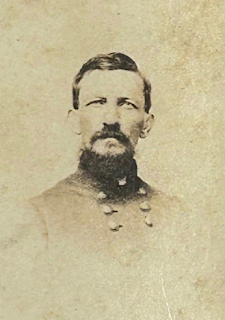

This postwar image of a determined looking Captain John Henry Martin of the 17th Georgia gives some sense of the character of this self-described "most unreconstructed Rebel you ever saw."

This postwar image of a determined looking Captain John Henry Martin of the 17th Georgia gives some sense of the character of this self-described "most unreconstructed Rebel you ever saw." Returning aBattlefield Trophy: a Letter from the 17th Georgia

In January 1913, Judge John HenryMartin of Hawkinsville, Georgia returned the long-lost corporal’s commission belongingto Thomas J. Rutledge, formerly of Co. F of the 8th Kansas Infantry.Martin had found it on the battlefield of Chickamauga on September 19, 1863,and wrote the following to Mr. Rutledge:

I was captain of Co. D, 17th Georgia Volunteers ofBenning’s Brigade, Hood’s Division, Longstreet’s Corps and we got to thebattlefield just after daylight on the 19th and were moved to ourextreme left, the Federal extreme right. Early in the morning of the 19th,Benning’s and Hood’s Texas Brigade were ordered to advance and did so. A friendof mine and I said we would be the first to strike the enemy and we dashedahead of the line and ran right into the 8th Kansas in the thickwoods. We ran right into the regiment and were captured for a short time.

Just after we got into the rear of the front of the regiment,a Federal soldier fired at me but a few feet distant but missed me and he waskilled. The fighting at this time was general and instead of the two sidesbeing in line, they were badly mixed up. Your side was holding up until a lotof Confederate cavalry with a yell dashed into the open on your right and rear(and our left). Then the Federals gave way and retreated, closely pursued byour troops and when our troops came up, I rejoined them.

We advanced up to the Lafayette road and by a cluster of oaksright be the side of the road where the Federals had had a battery; here I waswounded in the foot slightly. You will doubtless recollect where the batterywas located and when the cavalry dashed out. When the fighting stopped, I wentback to where I was shot at and found a dead man at the place as I near as Icould locate it. When the fellow shot at me, I did not notice him closely so asto certainly identify him for the fighting was then too furious forobservation. Close to this dead man was a knapsack which I took to be his andin the knapsack I found the commission and have had it ever since then. Ithought and have always thought until I got your letter that the owner of the knapsackand commission was the dead man and have so stated many times.

The next day, we moved to the right and were ordered to takean 8-gun battery that two or three brigades had tried in vain to take. We tookthe battery but lost nearly all our men. Every officer and man in my company waskilled, wounded, or hit with a ball. I was shot within 20 feet of the batterythrough my jaw, crushing it on both sides and from which I have never fullyrecovered. I was hit 11 times during the war, three of those wounds beingsevere. I was never in a Federal prison. I was captured on September 29, 1864,at Fort Harrison but got away as I had vowed that I would never surrender or betaken to a prison, preferring death. My company was captured by Lee’s surrenderbut I was not, being on detached duty near Danville, Virginia guarding theConfederate Cabinet against Federal raiders.

I was in skirmishes after Lee’s surrender and I have neversurrendered or been paroled but am today the most unreconstructed Rebel youever saw or heard of. I do not wear anything, except in midsummer, butConfederate gray. I do not, however, abuse or say hard things about the Federalsoldiers who fought us and some of my most loyal friends are old Federalveterans.

I know you will appreciate the commission and it will be amemento that you can leave your family.

Captain Martin died nine months later in Hawkinsville onSeptember 14, 1913, nearly 50 years to the day when he captured CorporalRutledge’s commission on the first day of the Battle of Chickamauga.

John Henry Martin was born April 10, 1842, in Decatur County,Georgia and enlisted in the 17th Georgia straight from college,entering the ranks a private but being quickly mustered as orderly sergeant. Hisservice record shows he was wounded at four battles: Second Manassas, July 2ndat Gettysburg, September 19th at Chickamauga, and May 6thduring the Wilderness. He was paroled May 20, 1865, at Thomasville, Georgia andreturned home where he became a judge.

Source:

“Lost in1863, Found in 1913. Commission dropped at Chickamauga Recovered,” Captain John Henry Martin, Co. D, 17th Georgia Infantry, Coffeyville Daily Journal(Kansas), January 22, 1913, pg. 6

To learn more about the Chickamauga campaign, please check out the Battle of Chickamauga page where you'll find more than 100 blog posts covering varying aspects of this important campaign.

September 19, 2025

Picket Shots of Chickamauga from the Army of the Cumberland

In "Picket Shotsof Chickamauga" I'll share some of the shorter stories provided by veterans of the Chickamauga campaign that might not be long enough to constitute a blog post on their own, but make for insightful reading.

In commemoration of the 162nd anniversary of the opening day of the battle, three accounts below give some perspectives from soldiers in the Army of the Cumberland, including Henry Dietrich of the 19th Illinois, Allen Fahnestock of the 86th Illinois, and Edward Molloy of the 87th Indiana. Tomorrow's post will feature three stories from their opponents in the Army of Tennessee.

Brotherton Cabin

Brotherton CabinAt the Battle of Chickamauga, I was a private in the ranks ofCo. A of the 19th Illinois Infantry. I was one of the skirmisherssent out to feel the enemy. At the beginning of the battle, we advanced towardsa clump of woods to draw the fire of the Southerners. We had to cross a fieldcovered with stumps and piles of rails and a battery was stationed behind us tothrow shells into the Confederate ranks whenever we should draw their fire.

We had advanced a considerabledistance when the Confederates opened on us. We took refuge behind the railsand remained there firing until the recall was sounded. The battery all thewhile threw shells over us and into the woods. When we were going back afterthe recall, I missed a young soldier named Metcalf. Looking back, I saw himkneeling behind a rail pike. Another soldier and myself, thinking he must bewounded, we went back to get him. We found that a short shot from our ownartillery had literally blown off the top of his head but it had not caused himto fall. [The Illinois Adjutant General’s report states that Private Fred W.Metcalf was killed in action September 11, 1863, at Lafayette, Georgia.]

Private Henry S. Dietrich

Private Henry S. DietrichCo. A, 19th Illinois Inf.