Ben Mattlin's Blog

May 3, 2017

I’m sorry…

Memoirs are based on memories. They are not reportage of facts. They shouldn’t lie exactly, of course, but

part of the bargain between memoirist and reader includes an understanding that

this is just one person’s subjective version of true events. The story as told is true to the writer’s

memory.

Nevertheless, I feel I must apologize to my readers. In my memoir, miracle boy grows up, I quoted

from my college application essay. I

quoted from memory, which is to say I made it up. The gist was true, but the actual quotations

were manufactured. Since I was only

quoting myself, I figured there was no harm.

I also figured there was no choice.

I didn’t have an actual copy of the essay at hand and didn’t think I

could get one, since it was 30 years gone. But I was wrong.

I have now acquired a copy of the essay that helped me win

acceptance at Harvard back in 1980. (A

version of the same essay was sent to all the colleges to which I applied;

there was no comment at in those days.)

And boy, did I get it wrong!

Please note, however, that this was the first time I’d endeavored to

write about my disability, and it does pretty well reflect events depicted in

the memoir. It’s just that the actual

quotations couldn’t be farther from the truth.

For instance, in the book I wrote:

I focus on how TV- and

comic-book-fueled fantasies “suffused my relationships with the physical

world.” From the Mighty Thor to Captain Kirk and, perhaps especially, Chief

Ironside, I’ve spent much of my life “identifying with embattled overachievers.

Is it escapism because I can’t face my own reality? Perhaps. But there is more

to it,” I propose.

My larger-than-life heroes, trapped in alien and sometimes hostile

worlds “as our barrier-laden society often seems to me,” I write, “invariably

prove themselves to be smarter, braver, and stronger than people expect. They

give me hope and a model for patience and self-determination that I strive to

emulate.”

Lots of SAT words in there. I’m particularly proud of the line: “Then

adolescence struck, and I’ll never forgive it!”

So here, for historical accuracy, is the actual

essay—verbatim, with the most relevant parts highlighted—and submitted to

Harvard at the end of 1979. It was

accompanied by two supplemental essays (which I think were better), to

reinforce the point that, even then, I saw myself as a writer in training. I’ll post the supplemental writing samples

separately.

Here it is. And

please forgive me for my inadvertent deception:

Ben

Mattlin - 1

I am told that the first sign of my handicap was my inability to

sit up by myself at seven months. In

time, I was diagnosed as being mentally retarded, which my parents found

absurd. After years of examinations by a horde of doctors, I had a muscle

biopsy and was reported to have spinal muscular atrophy, a rare, inherited,

neuromuscular disease that, in my case, is stable rather than progressive.

Little is known of it, and nothing as yet can be done to cure it.

I attended a nursery school and kindergarten for

“normal” children, I have a sense that I was very serious and aloofly

observant of the otherg, though thie probably is not true. More likely, this

was an image of what

I wanted to be. I admired

the serious, the uninvolved, the nonconformist. This might have been a

subsconscious defense against any social discomforts I may have had. If I was insecure about being

physically different —— inferior —— what better way to reassure myself than to

disassociate myself from the majority on the basis of spiritual or mental superiority.

I

tend to deny this and say that I vas

inclined to be serious because my idols, television characters like Captain

Kirk and Mr. Spock, the rough— and—ready Cartwright family, and Ironside, were serious

and rather gruff.

Of all of my idols,

Ironside is the most significant. Not only was he tough, serious, and wise; he,

too, was confined to a wheelchair. I felt that I, like Ironside, could defend

myself if necessary. When my friends saw a James

Bond movie, they imagined themselves able to fight off physical threats. I, too, had such fantasies. I could not “kick back,” and I

accepted that, but I was confident that I could pay back any other child who

“assaulted” me - by thinking. My unusual circumstance had honed my mental preparedness. Logic, rather than brawn, would be my

retaliation.

This is not to say that my childhood was a succession of fights.

With my bent for dramatic tension, I may have preferred it that way, but

reality had something else in mind. Something gentler, After kindergarten, I

attended the Walden School, the only non-specialized private school that was

willing to accept a student in a wheelchair. I soon made many friends who

helped me reach things and pushed me wherever I wished — even around the bases

at top speed in our whiffle ball games.

I left Walden after eighth grade, because I wanted to go to a

more academic schocl. Walden’s philosophy of education deals more with developing

students’ personalities than exercising their brains. I say this scoffingly, not because I do not

believe in social education, but rather because that often beeomes a guise for

a lack of intellectual education. I transferred to the Rudolf Steiner School.

Although it had steps at the entrance and was equipped with only a one—man

elevator, it agreed to take on my disability. For the school, it was a new

frortier; for me, it was old hat.

Then adolescence set in, and I'11 nevor forgive it. Not only was I a stranger in a new school, I became a stranger

to myself. My admiration

of the aloof had developed into acute sarcasm and anti—sociability. I found that these qualities were not

appreciated at Steiner. (They had not been

popular at Walden, either, but Walden was bigger, and I was part of a group of

anti-“socialites.”) I had difficulty relating to my classmates at

Steiner – and they had difficulty relating to me, and my handicap. I soon found

it hard to distinguish between who really liked

me and who sympathized with me. I became insecure. I was unsure of every movement I made

and rarely spoke out in class. I felt doomed to inadequacy. If anyone ever offers

me the opportunity to relive my early teens, I will refuse immediately.

I had another problem in ninth grade: I was due to have a back

operation in the summer and didn’t expect to return to school until November. I

told no one in school for fear of eliciting more pity. Over the summer, I decided

it was time for a change. The solution to the problem of cloying solicitousness

was in me, in my attitude. If

I accepted my condition (and I always had before), my classmates could do no

less! Phase one of the program was candor about the operation, While in

the hospital, I wrote an article for the school news—magazine explaining my absence. It

summarizes my hospital experience; a copy is enclosed.

Next, I had to be more active and more friendly. I joined every extracurricular

group I could. Getting to know as many people as possible became my

all—important goal. I enjoyed school, or rather the people in school,

tremendously. My antisociality faded! Tenth grade was replete with

achievements: a broader circle of friends, closer friendships, and a starring

role in the class production of Kaufinan and Hart’s You Can’t Take It With You. I attended nearly every school dance (and

even a dance at another school), went out with friends, and attended the annual

farewell—seniors party. The year’s achievements were epitomized by a yearbook

full of flattering messages.

My growth did not stop there. I gained more confidence and

established closer friendships – with members of both sexes — in eleventh

grade. This year I feel even more confident and relaxed. Social amenities now come

naturally. I am glad I learned what I did about self—confidence and sociability,

for I believe that to be an important key to happiness. One cannot wait for friends and

blessings to come simply on their own. And I am happy too in other aspects of

my life. Even the divorce of my parents has not proved entirely detrimental: it

has left me free of many of the restrictions of family that plague so many of

my peers.

As for senior year: despite the increased workload, I am fully

enjoying this year, devoted to the idea of instilling more confidence in the

freshmen than I had — without losing my senior image, of course.

The End

October 5, 2016

The Opinion Pages: A Disabled Life Is a Life Worth Living

My latest New York Times column

June 3, 2016

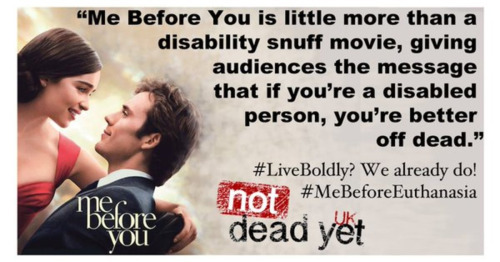

#Disabled people are sick of #suicide being portrayed as OK for...

#Disabled people are sick of #suicide being portrayed as OK for us! #LiveBoldly: boycott #MeBeforeYou! #NotDeadYetUK http://thndr.me/6VanSz

September 1, 2015

The tax advantages of low-cost, low-benefit variable annuities

My latest @famagazine column

July 25, 2015

An Act That Enabled Acceptance

June 27, 2015

May 25, 2015

May 18, 2015

Upbeat blues, as improbable as that sounds, to groove to on yr Mon evening

An old gem:

Arthur Lee - “Everybody’s” Gotta Live"

Upbeat blues, as improbable as that sounds, to groove to on yr Mon evening

An old gem: Arthur Lee - “Everybody’s” Gotta Live"

May 15, 2015

F. A. O. Schwarz to Close Its Doors on Fifth Avenue

Noooo! My childhood is over!!! (About time, really. I mean, I am 52…)