David Pilling's Blog

February 14, 2025

Getting ahead (2)

On 14 February 1283 Edward I was at Rhuddlan. The war in Wales was still raging, but the king and his advisers made time for other business.

On this day they dealt with six cases. Edward took a personal interest in the case of Madog de Brompton, a Welshman accused of murdering one Roger Dodesune. The king was shown the verdict of a jury in Shropshire, which found that Madog had killed Roger in self-defence. Edward, 'moved by piety', agreed with the verdict and ordered Madog to be pardoned and restored to his lands, goods and chattels.

It would be nice to know more about this Madog. Brompton (Brontyn in Welsh) is a hamlet in Shropshire, right on the border: it lies between Church Stoke and Newtown, both in Powys.

Perhaps Madog was related to one of the local mixed-'race' families.

The Antiquities of Shropshire record that Great Weston/Weston Madoc was held by Robert fitz Madoc in 1224, as a tenant of Thomas Corbet of Caus. After his death Henry III seized the manor, even though Robert had left an heir, Owain. By 1242 the manor was held by one Hywel de Brompton as a serjeant of the king, but after his death it was seized by John Lestrange. Thomas Corbet then managed to reclaim it at law.

The Chirbury Hundred-Roll records that Hywel de Brompton's heir was later in the custody of Lord Edward (later Edward I) and held his land of the prince worth 100 shillings. This was Roger Fitz Hywel, who held the land of Weston. Unfortunately the editor of the Antiquities could find no further trace of Roger Fitz Hywel or the Brompton line.

Getting ahead (1)

#OTD in 1283 a string of cases were heard before the king and council at Rhuddlan in Wales. Edward I was still embroiled with the war against Prince Dafydd, but - much like his ancestor, Henry II - he was in the habit of doing umpteen things at once. I have wondered how many of their scribes had nervous breakdowns, being dragged along in the wake of these frenzied Angevins and their endless to-do lists.

We don't know the order in which the cases were heard, so I'll make it up. First, a certain Sir Thomas Mandeville came before the king and presented him with the head of an Irishman named 'O'Donald'. He was in fact Domnhall O Donnell, King of Tír Connaill.

This was related to a very long-running war in Ireland, in which the Mandeville and Fitz Warin factions had fought like rats for control of territory. The various Irish kings and lords had been drawn into it, and in 1281 Mandeville and his Irish ally, Hugh 'Boy' O'Neill, wiped out their enemies at Disert-dá-chrích (Desertcreaght, County Tyrone).

Although Edward never went to Ireland, he kept his finger on the pulse. He ordered Mandeville to be paid a fee for the head of O'Donnell, while Hugh and 'other Irishmen of Ulster' received bounties amounting to £18. Another payment went out to a certain O'Hanlon and his men-at-arms, along with a robe of the king's gift to him.

The reference to 'men-at-arms' is interesting; in an English context, it usually referred to heavy armoured cavalry, and implies the O'Hanlon had mailed horsemen as well as kern and gallowglass.

The gift of a robe is not just a mere detail. O'Hanlon was now currying the favour of the king, and dealt direct with him and his ministers. By doing so he bypassed the Red Earl, Richard de Burgh, who saw himself as the greatest power in Ireland.

So much for the first order of business. Mandeville and his grisly trophy were dismissed, and Edward turned to the next item.

February 13, 2025

Brutal power plays

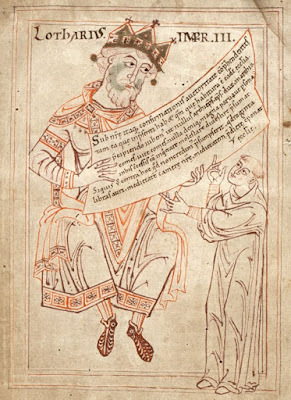

Lothar or Lothair III, Holy Roman Emperor (reigned 1133-1137)

Lothar or Lothair III, Holy Roman Emperor (reigned 1133-1137)1136. While John II Komnenos pushed east, his allies in the west went into action against the Normans of Sicily. The army of Pisa sacked Amalfi, and from late 1136 the German emperor, Lothar III, led an expedition into southern Italy. There he lifted the siege of Naples and conquered much of Apulia, including Bari.

Lothar probably had assistance from John, who seems to have sent troops as well as money. However, Lothar's luck then turned. He argued with the Pope over Apulia, his soldiers mutinied, and he was forced to retreat despite impaling over 500 men in a desperate bid to restore discipline. Lothar died in the Alps on 4 December, depriving the Roman emperor of a powerful ally. In the aftermath the Normans were able to rally and retake their lands in southern Italy.

None of this had any direct impact on John's campaign in distant Anatolia. While on the march east, he also made contact with Fatimid Egypt, perhaps to discuss trade or a more permanent alliance. This may imply that John intended his reconquest of eastern Anatolia to be permanent, with Egypt as a constant neighbour. To that end it made sense to establish friendly relations with the Fatimid Calpih.

John's enemy in the east was Leon I, ruler of Armenian Cilicia. In recent years Leon had waged war against the Frankish princes of the Holy Land, and defeated Raymond, Prince of Antioch. He then divided his forces, sending an army to attack the Roman stronghold of Seleukia, while Leon himself attended a meeting with Baldwin of Marash, a noble of the county of Edessa.

Unhappily for Leon, he had walked straight into a trap. He was treacherously seized and imprisoned in Antioch, after which his three sons fell to arguing. The eldest, Constantine, was blinded by his brothers, who were then also captured.

These brutal power plays were all to John's advantage. The internal collapse of Cilicia made it vulnerable to conquest, and this was his chance to reclaim it for the Empire. He had every intention of seizing that opportunity.

February 12, 2025

Of all tribes and tongues (2)

The Roman ruins at Seleukia, modern-day Turkey

The Roman ruins at Seleukia, modern-day TurkeyIn early 1136, after months of preparation, Emperor John II Komnenos marched east from Constantinople. His objective was Pamphylia, where the Roman coastal fortress of Seleukia was under siege.

Pamphylia, along the southern coast of Anatolia (Asia Minor) had once been part of the Roman Empire. Along with the rest of the eastern provinces, it had been thrown into chaos after the disastrous battle of Manzikert in 1071. Now it was largely hostile territory, which meant John had to fight his way through to the isolated imperial outpost at Seleukia.

The fortress was besieged by Leon I, the ambitious ruler of Armenian Cilicia, who sought to expand his power from the mountains to the coast. He launched his attack on Roman territory early in the year, gambling that John would be too distracted by problems in the west to mount an effective response.

Unfortunately for Leon, he had miscalculated. John's victories in previous years had secured much of western Anatolia, including the great stronghold of Kastamon and Gangra. Meanwhile the various Turkish rulers, who might have distracted the emperor, were at each other's throats instead.

Thus, John was free to move all his forces against Leon. By the winter of 1136 he had reached the southern coast at Attaleia, where he awaited the arrival of the imperial fleet with his baggage and military equipment. Mindful of his western allies, John also found the time to send an embassy to the Holy Roman Emperor, Lothar III. The emperor's envoys arrived at the German court in 1137, bringing gifts.

John's embassy was concerned with the Normans of Sicily, and their ambition to conquer Roman territory in Africa; specifically, modern-day Tunisia with some of eastern Algeria and western Libya. Under Roger, the so-called 'tyrant' of Sicily, the Normans were also waging war against John's new allies, the rulers of Venice and Pisa

Lothar responded favourably to the Roman embassy, as did the Venetians and Pisans. From late 1136 they launched multiple campaigns against the Normans; we shall look at these next, as well as John's eastern offensive.

Of all tribes and tongues (1)

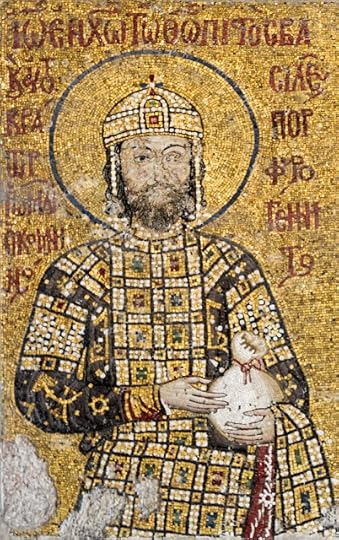

Emperor John II from the mosaic at Hagia Sophia

Emperor John II from the mosaic at Hagia SophiaIn 1136 John II Komnenos embarked upon the most ambitious military expedition of his reign. After seizing power in 1118, he had spent much of his reign at war, reconquering western Anatolia from the Seljuk Turks as well as fighting the Hungarians and Venetians in the West. Finally, after almost twenty years of struggle, he was in a position to try and recover former Roman provinces in Cilicia and Syria.

His opportunity came thanks to two major developments. In 1135 he received an offer of marriage by ambassadors from Antioch, now ruled by the Franks. At the same time the province of Pamphylia was invaded by Leon I, lord of Armenian Cilicia. These things combined gave John every reason to mount a campaign in the east.

The envoys from Antioch probably arrived at Constantinople in late 1135, after John had returned to the capital from Paphlagonia. They proposed a marriage between Constance, heiress to the principality of Antioch, to John's youngest son Manuel. As part of the agreement, Antioch would once again be part of the Roman Empire. From the emperor's perspective, it offered the chance of a bloodless reconquest.

John seems to have started preparations for a major campaign before the year was out. According to William of Tyre, he set about gathering a large army of diverse peoples and supplies. Quote:

"From every part of his empire he had summoned people of all tribes and tongues, and now, with a countless number of cavalry and a vast array of chariots and four-wheeled carts, he was on the march..."

At the same time John engaged in intense diplomatic manoeuvres with the Latin west and Fatimid Egypt. These western initiatives focused on aligning him with the Italian maritime republics, the Papacy and the Geman Emperor against the rising power of the Normans of southern Italy. While these new allies guarded his western flank, John would be free to march east.

Events took a fresh twist in early 1136, when news arrived of Leon I's invasion of Pamphylia. After expanding his power beyond the mountains of his homeland, Leon had laid siege to the strategic Roman fortress at Seleukeia, guarding the coastal road leading out of Cilicia.

Thus, John marshalled his army 'of all tribes and tongues' and set out for the distant east.

February 11, 2025

Lively and open war

In February 1298, after extending the truce with France, Edward I paid a visit to Brabant. He went to see his daughter, married to Duke Jan II of Brabant, and to do a bit of business.

The duke was notably pro-English in his outlook. During the king's visit, Jan granted the port of Antwerp and the adjoining towns of Liere, Herentals and Liere to his father-in-law.

This was a hefty slice of Brabant, including the chief port, and probably a temporary lease called 'achterleen'; a form of subinfeudation, whereby a grant was made in exchange for money and military support. Technically the margraviate of Antwerp was held of the Holy Roman Empire, but there was nothing to stop Duke Jan from making out a temporary sub-grant.

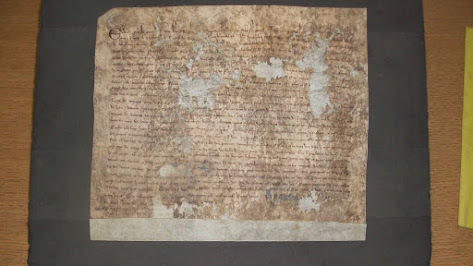

In the same month, Edward moved to Aardenburg near the border of Zeeland. Here the king renewed his military contract with the barons of Franche-Comté in Burgundy (see pic, original document held at the National Archives). In exchange for another 30,000 livres tournois, the barons were to continue to make 'lively and open' war against the French.

The Battle of Stirling Bridge had occurred in September 1297, but Edward showed no particular haste to go home and deal with the crisis in Scotland. Instead he delegated the task to Earl Warenne and the council in London. Writs for the Scottish expedition were issued in October 1297, for a muster at Newcastle on 6 December. The bulk of this northern army was composed of Welsh infantry; 5157 Welshmen were in pay from 8 December 1297-29 January 1298.

February 10, 2025

The context of killing

The murder of John Comyn of Badenoch, and his uncle Robert, in the church at Dumfries on 10 February 1306 was one of the most shocking acts of the period. Less clear is the motive.

If we take a look at the wider context of the killing, especially the immediate aftermath, the fog starts to clear. Once Bruce and his men had finished off Comyn, they rode to Dumfries castle and seized it from the sheriff, Sir Richard Siward. They were joined by Sir Roger Kirkpatrick who, somewhat ironically, had been holding court nearby as one of Edward I's justiciars of Galloway. His fellow justice, Sir Walter Burghdon, was then taken prisoner along with the other English officials in the region.

The intrepid band then rode to Siward's castle of Tibbers, seventeen miles north-west of Dumfries, and seized it along with Comyn's castle at Dalswinton. The royal castle at Ayr soon followed, as well as James the Steward's castle at Inverkip and Rothesay castle on the Island of Bute. Later evidence strongly suggests that the royal castle of Dunaverty on Kintyre and Bruce's castle of Loch Doon in Carrick were provisioned at about the time as the murders at Dumfries.

In short, Bruce had taken a string of strategically important castles that enabled him to control the sea-routes in and out of western Scotland. His actions, and those of his supporters, were efficient and co-ordinated, implying their strategy had been carefully worked out beforehand.

This was emphatically not the behaviour of a man who had murdered Comyn in a fit of rage or panic, on the spur of the moment. Rather, Comyn and his uncle had been carefully targeted, as part of Bruce's long-planned seizure of power. Now he had to wait for the reaction of Edward I, slowly expiring in distant Westminster. But that's another tale...

Sources:

Traitor, Outlaw, King Part One: The Making of Robert Bruce by Fiona Watson

Edward I by Michael Prestwich

Disunited Kingdoms: People and Politics in the British Isles 1280-1460 by Michael Brown

Treachery and battle and strife

Madog died at Whittingdon castle in Shropshire, where he and his eldest son Llywelyn had gone to meet Henry II's officers. This meeting was held to discuss the latest threat of invasion from Owain Gwynedd, ruler of Gwynedd (the kingdom adjacent to Powys) and self-styled Prince of Wales.

The details of the meeting are reported by the poet Gwalchmai. According to him, Llywelyn was granted a stretch of territory between Rug and Buddugre to patrol against Owain. This was part of Henry's defence policy, whereby he paid the local rulers of Powys to garrison a chain of border forts against incursions from Gwynedd. That also suited the Powysians, since they took the king's money and men to help guard their own frontier.

Very soon after his father's death, Llywelyn was killed in unclear circumstances. A clue to his demise comes from Gwlachmai, referring to events in early 1160:

"Gwelais frad a chad a chamawn,

Cyfrwng llew a llyw Merfyniawn".

(I saw treachery and battle and strife,

between a lion and the leader of the descendents of Merfyn [the dynasty of Gwynedd])

Gwalchmai seems to imply, without saying outright, that Llywelyn was murdered by the forces of Owain Gwynedd. This is not unlikely, since Owain certainly launched an invasion of Powys at this time. Alternatively, Llywelyn may have fallen victim to an internal feud in Powys.

Whatever the case, Owain took full advantage. Shortly afterwards Owain led an invasion of Edeirnion, deep inside Powysian territory; the poet Cynddelw lamented that if the king and his son were still alive, the forces of Gwynedd would never have penetrated so far:

"While Madog lived there was no man

Dared ravage his fair borders

Yet nought of all he held

Esteemed he his save by God's might ...

If my noble lord were alive

Gwynedd would not now be encamped in the heart of Edeyrnion."

Much of the above is taken from David Stephenson's brilliant book on medieval Powys. Anyone who really cares a damn about the history of Wales in this era - as opposed to noisy chest-banging - MUST get hold of a copy. That's an order.

A murder at Dumfries...

#OTD in 1306 John Comyn of Badenoch and his uncle Robert were murdered by Robert de Bruce and his followers in Dumfries church.

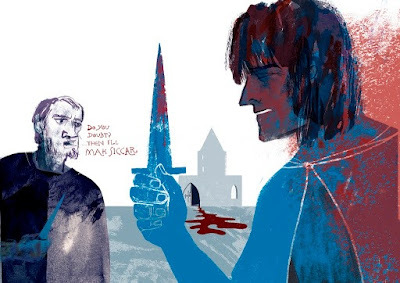

Comyn was at his castle of Dalswinton, seven miles north of Dumfries, when he received an invite from Bruce to meet him in the church. What they discussed is uncertain. After a brief talk, Bruce kicked out at Comyn, and ran him through with a sword or dagger. Robert was killed by Sir Christopher Seton.

A later account claimed that Comyn was killed in revenge for betraying Bruce to Edward I. That is Bruce propaganda, invented after the fact to justify a political murder. The killing was in the same vein as the murder of Henry of Almaine, murdered at a church in Italy in 1271, or the followers of John IV Laskaris, slaughtered in a church in Nicaea in 1258.

The reality is that Bruce wanted to be King of Scots, and the Comyn faction were his chief rivals. Both men had sworn homage to Edward as overlord of Scotland, but the king was old and ill, and clearly wouldn't live much longer.

Even after the killing, Bruce did not immediately rise against Edward. Instead he sent a letter to the English at Berwick, warning that he would defend himself with 'the longest stick that he had' unless Edward agreed to his demand. That demand can only have been the kingship.

Bruce was most likely seeking to fulfil the ambition of his grandfather, Bruce the Competitor, who had offered to help Edward conquer Scotland in exchange for the crown. If that meant swearing homage to the old king - in the unlikely event that he would swallow Comyn's murder - so be it. When Edward died, the Bruce Scots would have to re-swear their oaths to his heir, Edward II. That was a different situation altogether.

In the event, Edward I's reaction was ferocious, and the war was back on again.

February 8, 2025

Last Emperor of the Romans

Constantine was proclaimed Emperor of the Romans in a small ceremony at Mystras on 6 January 1449. I am no expert on the man, but he seems to have been loyal and capable, and might have made a successful emperor in a less hopeless time. As it was, he inherited a bankrupt 'empire' that consisted of Constantinople and a few outlier territories. Even the Great City was a shadow of its former glory, much of it depopulated and lying in ruins.

Criticising a figure like Constantine, still regarded as a hero in Greece, is to risk making oneself seriously unpopular. However, it is not the business of historians to deal in hero-worship. For all his positive qualities, Constantine has been accused of a major blunder in trying to play off the Ottoman rulers against each other. This policy triggered a furious rant from Çandarlı Halil Pasha, the Ottoman grand vizier. Quote:

"You stupid Greeks, I have had enough of your devious ways. The late sultan was a lenient and conscientious friend to you. The present sultan is not of the same mind. If Constantine eludes his bold and impetuous grasp, it will only be because God continues to overlook your cunning and wicked schemes. You are fools to think you can frighten us with your fantasies, and that when the ink on our recent treaty is barely dry. We are not children without strength or reason. If you think you can start something, then do so. If you want to proclaim Orhan as Sultan in Thrace, go ahead. If you want to bring the Hungarians across the Danube, let them come. If you want to recover the places which you lost long since, try it. But know this: you will make no headway in any of these things. All that you will achieve is to lose what little you still have."

Ouch. Constantine and his advisers seem to have had little idea of how to deal with the Ottomans, wavering between appeasement and defiance. In fairness, they were in a dire situation, and it was only a matter of time before the city was attacked. Without substantial aid from the West, Constantinople stood no chance.

There are many accounts of Constantine's death, but he almost certainly went down fighting. One of his last recorded quotes was:

"God forbid that I should live as an Emperor without an Empire. As my city falls, I will fall with it. Whosoever wishes to escape, let him save himself if he can, and whoever is ready to face death, let him follow me."