Laurie Steed's Blog

May 1, 2020

Short Stories for the Win

In such strange times, it’s easy to lose track of all kinds of things. And so I was surprised (but heartened) to find two recent successes with short story submissions from my second book, Nova.

Firstly, my story, ‘The Crazy and The Brave’ has been accepted for publication in the July 2020 Issue of Westerly, under the guidance of editors Kate Noske and Josephine Taylor, and fiction editor (and esteemed short story writer and novelist) Susan Midalia. ‘The Crazy and the Brave’ follows a family visiting Sculptures by The Sea at Cottesloe Beach in 2012, the same year in which a statue, Childhood Morning, was stolen from the exhibition. This story holds a special place in my heart, and so I’m doubly grateful that it’s found a home among three of the most supportive, most passionate advocates for literary fiction here in Western Australia.

Another story, ‘But What Have You Done Lately?’ received an honourable mention in the 49th New Millenium Writing Awards in the USA. ‘But What Have You Done Lately?’ follows a man a woman on the road trip from hell as they make-up and break-up along the coast of Queensland. It’s flash-fiction, and I still remember the time my sister read it, looked up at me, and said, ‘Whoa.’ From there, I guess it was just a matter of finding the right reader.

On a greater scale, It feels as if things are slowing starting to move again in the world. I’m grateful for this, not just in terms of my writing, but just as much because the world feels that little bit lighter. Here’s hoping we can soon return to normality, community, and connectivity.

April 29, 2020

Five Short Stories You Must Read - Angela Wilson

In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson is Buried by Amy Hempel. In The Collected Stories, 2006.

This story was suggested reading for a short fiction workshop I once took. The fragmented style of the narrative expanded my ideas about what a short story was, viz. it is a more flexible, ambiguous form, which doesn’t have to do all of the things a novel does, like adhering to a three-act structure.

In the story, the narrator who is visiting a friend in an L.A. hospital, reflects on her guilt at having stayed away for months. Her fears about the situation, prevent her from discussing her friend’s imminent death, openly. Instead, she is fixated on images like earthquakes and airplane turbulence, and a report about a man who apparently dies from seeing his arm mutilated. Privately, she wants to run from the situation, speed down the coast highway and rage all night in Malibu. The story feels like a set of disjointed thoughts – snapshots, shifting between unrelated scenes, while hinting at a plot. The dialogue between the friends is in the tone of their college days; light and ironic.

I came across a quote by Hempel in the Missouri Review, recently, where she responds to criticism about her writing style:

‘Interviewer: ‘One critic says that “your structure is like the mongrel dog in ‘The Center’, part something and part something, and the best are those whose parts almost fly apart but don’t.” You start with your beach ball, and things collect on that’ (1993, p.88).

Hempel: ‘There is a way in which a writer does not have to spell things out, and the reader will get it. There's a way in which the mind works to impose meaning and order automatically on seemingly random bits of information, so you can almost offer these bits up without knowing yourself how they fit together— suspecting that they do—and trust the reader to make some sense out of it’ (ibid).

Reverting to a Wild State by Justin Torres. In The New Yorker, Aug 1, 2011.

I hadn’t heard of Torres, until I came across ‘Reverting to a Wild State’ in The New Yorker. I took out a digital sub over Christmas – the fiction archives date back to the old days and I got a free tote bag. Torres’ essays and stories can be found in Granta, Tin House, Gulf, and other publications. His is also author of the novel, ‘We the Animals’.

‘Reverting to a Wild State’ jumps around a bit, and while some things in the story had me feeling slightly off-balance, the experience was riveting. The first-person narrator does a good job at holding out on the reader, telling the story at an angle to the situation at the heart of it. Which is about a relationship break-up. The relationship itself spans a decade, written in reversed segments: 3,2,1,0.

3 opens in a New York train station after midnight, where the narrator is playing daredevil at the edge of the platform. He’s heading uptown to clean for a man who lives in a penthouse suite. (It’s likely the job entails things that aren’t to do with cleaning.) In 2, the narrator is dining out with Nigel, his partner. The disparity between the two lovers in the way they look and act, is sad and hilarious and savage, and still sticks with me. In 1, Nigel fusses over the old cat, plays cracked records and fills up the apartment with things. The narrator likes to sleep around, and steals opportunistically. Nigel is a jealous lover. The story ends at 0, where the two are just nineteen and working on a farm in Virginia. New love amid a warm summer landscape, enables the reader to relax, peripherally aware of a storm building on a mountain slope.

Do the reversed segments work? I think so. All of the harm inflicted, and the mess the narrator has made of the relationship, feels strangely restored by the end. And although we are really at the start of the relationship, a small feral thing pops up, grounding us in the passing of time.

The Sentence is a Lonely Place by Gary Lutz. In Partial List of People to Bleach, 2013.

The first time I read this creative essay, my brain hurt. The break-down of sentences and words into units of sound, seemed pernickety. I did enjoy the stuff about Lutz’s childhood, where, ‘Words seemed to be intruders, blown into the rooms from otherwhere through the speakers of the television set or the radio . . .’ (p.2). Later, I went back to the essay when my own writing seemed toneless and flat. I’ve returned several times since.

The sentence is a lonely place because words don’t feel like they belong together, Lutz says. ‘Writing is rich to the extent that the drama of the subject matter is supplemented or deepened by the drama of the letters within the words as they inch their way closer to each other or push significantly off’ (pp.101-102). Words need to ‘rub off’ on each other – disperse consonant and vowel sounds into their successors. He examines the prose of some notable authors, which he believes to be rich. For example, the four word phrase, ‘acutely felt, clearly flat’, in Christine Schutt’s story, ‘The Blood Jet’. Here, clearly flat ‘. . . contains the alphabetic DNA of the first phrase.’ Almost. The adjectives felt and flat ‘. . . begin with a tentative-sounding, deflating f and end with the abrupt t.’ As well, ‘. . . the richness of receptivity summed up in felt has been leveled into the thudding spiritlessness of flat’ (p.99). And so on.

How does Lutz’s prose look on the page? Below is an excerpt from his short fiction collection, Stories in the Worst Way, 2009.

‘She had a strapping, hoydenish body. She maintained a sunlamped handsomeness. But she was hygienically delinquent. I wondered what my predecessors had made of the ashtrayish, perspiry nimbus she almost always hazed around herself’ (‘Recessional’, p.104).

While Lutz’s sentences are uniquely inventive, they can also seem confounding. To what extent then, should we choose one word over another because of its sound – what if the writing doesn’t make sense? In Lutz’ scheme of things, sentences unfold tonally, rather than perhaps, logically, conveying meanings in ways which might not seem syntactically ‘correct’. In any case, the sentences are catchy to the eye and ear, and are more accessible, I think, as we grow into them.

Midnight in Dostoevsky by Don DeLillo, in The Angel Esmeralda: Nine Stories, 2011. Also published in The New Yorker, Nov 30, 2009.

I knew little about Don DeLillo until his name cropped up in a book I read by Brooks Landon: Building Great Sentences. (There was consensus among my writing pals that my sentences could be wordier.) Landon teaches a class in the English Department at Iowa, which focusses on building complex sentences. His book tells you how to grow a kernel sentence into something more complete. Diagramming and numbering of various sentence levels, viz. base clauses, modifying clauses, subordinates, coordinates, etc., is involved. I’ve little doubt I’d flunk Landon’s class at Iowa. He said DeLillo’s fiction was full of these sentences, so I had a look. I don’t know if DeLillo thinks his sentences are ‘cumulative’. At any rate, they’re masterful. Here’s an excerpt from ‘Midnight in Dostoevsky’.

‘We were two somber boys hunched in our coats, grim winter settling in. The college was at the edge of a small town way upstate, barely a town, maybe a hamlet, we said, or just a whistle-stop, and we took walks all the time, getting out, going nowhere, low skies and bare trees, hardly a soul to be seen’ (p.119).

The text is flowing with sentences like these, and the plot is intriguing. Two freshmen, Robbie and Todd (Robbie is narrating), are curious about an old man in a hooded duffle coat they encounter on the streets near their campus, which is located somewhere in north-east America. They walk the town between lecturers, filling in backstory about him and arguing over the details, intensely. The dialogue is superb in the way the two students get at each other. Todd is interested in facts, while Robbie’s imagination is unending. They weave Ilgauskas into their story, a philosophy professor who teaches Logic, and doesn’t make much sense; believing him to be related to the man in the hooded coat. Ilgauskas reads Dostoevsky, they discover. When it becomes clear to Tom how they can find out the truth about the old man in the coat, Robby is dead against it, and at this point, the impasse between reality and fantasy, comes to a head.

Winterreise by Christine Schutt. In A Day, A Night, Another Day, Summer, 2005.

This tale is set in New York City, amid the yellowing ginkoes in the park. The narrator witnesses the deterioration of Margaret, her life-long friend and walking buddy, who has cancer. It is a Thoreauvian tale, about the swift passing of time. Though the prose lingers, laying bare the anguish between the two friends. On their walks, the narrator discusses her readings of Thoreau, who sought nearness to nature. The vivid imagery in the language, and the infusion of rhythm and rhyme, heightens the impression of character, place and time in this tale.

‘Used to be even in the rain we walked hooded in water-repellent bicolor suits that swished and sounded as if we were fat when we were thin, both of us, Margaret and I, and only walking for the routine and the way it felt, hands free, holding nothing. Children, leashes—my first husband—we left even the dogs sleeping to meet each other at the entrance to the park marked by the great elm, that folktale tree with its house-wide trunk sprung green. We meet there still although not as often—and no more in the rain’ (p.137).

Angela Wilson lives in Wellington, Aotearoa, NZ, where she writes and learns te reo Māori through Te Herenga Waka, Victoria University of Wellington. She likes clean air, big dogs and stand-up comedy. Most of it.

April 1, 2020

Five Stories You Must Read - H.C. Gildfind

‘You're Ugly Too’ by Lorrie Moore

I love this story, and every other written by Lorrie Moore! She is the queen of tragicomedy. Her fictional voices are full of life, warmth, humour and incredibly astute insights. Her stories are hilarious, touching and true. This story includes a confrontation between a jaded man and a jaded woman: each of them are fraught with all the hurt, anger and insecurity of middle-aged disappointment. They have an exchange which, I think, sums up Moore's world view. One character says, "Live and learn." The other replies, "Live and get dumb." Indeed!

‘So Much Water So Close To Home’ by Raymond Carver.

This story deserves its fame! It is very unsettling and is about a group of middle aged men who go fishing in a remote spot. They find a dead naked girl in the river and, instead of going home to report it, secure her to the riverbank and continue to fish. The story is really about the 'fallout' that results from this hideous choice, in both the local town and in one of the character's marriages. This is a story about the complex murk that lies around, and between, men and women. I can also recommend the great movie based upon this story, shot in Australia, called "Jindabyne." Read and watch them together - fascinating!

‘Sonny's Blues’ by James Baldwin.

I knew nothing of Baldwin till I stumbled across this touching story. Baldwin has this incredibly assured writing style that immediately transports you into his realist narratives. He has a tender and observant eye, and a profoundly compassionate attitude to all of his characters. This story is about two brothers living in Harlem, one who's a 'successful' teacher and the other who, though he is struggling desperately with drugs, can nevertheless find solace and self-expression in music. This story lead me to read Baldwin's novel, Another Country: brilliant!

‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ by Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

This is an amazing, haunting gothic story that draws the reader into the claustrophobic horror of living in a society (and a marriage) that would rather pathologise women than respect them: its female protagonist has been imprisoned in her home, having been given the 'rest cure' for her 'hysteria.' This story will really make your skin crawl, in the best possible way. Very chilling, very insightful and, unfortunately, still very pertinent. Perkins was a prolific and fascinating feminist writer who also wrote the important book: Women and Economics – A Study of the Economic Relation Between Men and Women as a Factor in Social Evolution (1898).

‘Caterpillar Men’ by Max Taylor.

This story represents a true attempt by a writer to empathise with utterly different people from an utterly different time and place. In this surreal, touching and disturbing story, Taylor has attempted to imagine the experiences of Korean comfort women. I came across this story is in the anthology The Kid on the Karaoke stage (Fremantle Press, 2011) and it has stayed with me since.

Helen Gildfind lives in Melbourne and has published fiction, essays, and book reviews in Australia, overseas and online. She was awarded an Australia Council Grant to complete a collection of short stories, The Worry Front, which was published in 2018 by Margaret River Press. Gildfind also won an APA to complete a PhD at the University of Melbourne, which was awarded in 2012. In 2020, Gildfind won the Miami University Press international novella competition: the publication of Born Sleeping is upcoming.

March 29, 2020

Five Short Stories You Must Read - Wayne Marshall

‘American Dreams’ by Peter Carey

Thematically, this classic from Peter Carey’s debut collection The Fat Man in History rails against the march of American culture through even the smaller pockets of Australian society. But the great pull of it, what brings me back time and time again, is its tantalising premise: on a hill overlooking a rural Australian town, one of the residents has built a wall. What, exactly, lies behind this wall up on Bald Hill, as the locals have dubbed it? And why on earth did Gleason – ‘this small meek man with the rimless glasses and neat suit who used to smile so nicely at us all’, a council worker on the verge of retirement – have his brick wall built in the first place?

This story endures because when that answer comes, it not only rises to meet the expectation of the set-up but surpasses it, in what is probably my favourite scene in all short fiction. So, when Gleason dies and the wall comes down, what does it reveal? Beauty and wonder and terror and love. And art – the transformation of the raw stuff of everyday life into something higher, something new. I’ve read ‘American Dreams’ dozens of times, and am still profoundly moved – and surprised – by what happens when the townspeople flock to Bald Hill to discover what Gleason has left for them. And also, of what comes after. Because the story doesn’t end there, but spirals in another surprising direction, a testament to what can be achieved in the space of a short story, and the dazzling imagination typical of all the short fiction produced by Carey in the 1970s, before he departed for the land of the novel.

‘Paradise Park’ by Steven Millhauser

For those who don’t know of him, American writer Steven Millhauser has been working predominately in the short story form since the early 1970s (although he won a Pulitzer for his novel Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer). His story worlds are a beguiling mix of the mundane and the magical. A bunch of bored suburban teenagers embrace a fad of laughter contests, with dangerous consequences. A small town falls prey to a serial slapper. A young woman disappears from another of Millhauser’s small towns – or was she simply ignored out of existence?

There are probably other Millhauser stories I enjoy more, or others I enjoy more consistently on re-reads, but as a must-read, I can’t go past ‘Paradise Park’. In it, Millhauser takes his obsession with amusement parks and other astounding feats of architecture to the very limit and beyond. Over 38 pages – rendering it almost novella length – and via a springboard of forensic detail, Millhauser documents in faux journalistic style the twelve-year rise and fall of the eponymous amusement park. The story is almost characterless; with little dialogue and dense paragraphs, it’s by no means an easy read. But as Paradise Park expands at the hand of its mysterious creator, opening up a shadowy underground level filled with illicit thrills, and its popularity soars, we are taken to a place that gives me shivers still.

An incredible work by a committed writer, which can be found in Millhauser’s 1998 collection The Knife Thrower and Other Stories.

‘How To Tell A True War Story’ by Tim O’Brien

The war story is a slippery thing in the hands of Tim O’Brien. How do you tell a true war story, he ponders throughout this story from his 1990 linked collection The Things They Carried. On the first level, we’re presented with a story: that of Rat Kiley, an American soldier serving in Vietnam, and his grief at the killing of his best friend and fellow soldier Curt Lemon by booby trap. This is all observed and relayed by another soldier in the platoon – a fictional version of O’Brien. On another level, we have O’Brien the writer, at his desk years later, looking back on his experiences in the Vietnam War and trying to make sense of it all. He is a man obsessed with story and storytelling, with finding a way of telling it just right.

This is a masterpiece. It would still be a masterpiece if it only operated on that first level. O’Brien takes you right there, to the living, breathing, fatal jungle. Every detail is perfect, each observation cutting, the atmosphere of collective madness palpable. There are also a few scenes (such as Kiley’s attack on a baby water buffalo following Lemon’s death) that are shocking in their power. But it’s that second level – O’Brien’s meditation on storytelling, his metafictional interjections – through which ‘How To Tell A True War Story’ becomes something extraordinary. Elsewhere in his collection, O’Brien comes to the epiphany that thirty years on, what he’s really doing is trying to save his life through story. And what a magical thing that is.

‘The Quiet’ by Carys Davies

One of the hallmarks of most great stories, for mine, is an unexpected turn. A twist, a sting in the tail, a surprise that at first might appear to come out of the blue, but on closer inspection is inevitable, given the crumbs sprinkled throughout.

In ‘The Quiet’, the opening story of her collection The Redemption of Galen Pike, Welsh-born Davies presents us with a lonely, isolated homesteader named Susan Boyce, newly relocated to the Australian outback. The story begins in decidedly gothic fashion. Susan’s husband is away, rain pelts her tin roof, and her creepy neighbour – the only other person for miles around, a man whose visits she detests – appears at her window. That neighbour, Henry Fowler, has ‘the look of a convict about him’, and as Susan reluctantly lets him inside, you sense something awful is about to happen. When Henry begins to undress, while Susan has her back to him at the stove, these fears seem confirmed.

Well, something awful is about to happen. But not at all in the way you’d expect.

To say any more about what happens next would be criminal.

‘Escape From Spiderhead’ by George Saunders

The world of a George Saunders story is a wild, wild place. Case in point: ‘Escape From Spiderhead’, from his most recent collection Tenth of December. From the very first sentence, we’re dropped without preamble – this immediacy being one of Saunders’ many strengths as a writer – into an experimental lab facility that doubles as a prison, where radical new drugs are tested on human subjects. One of those subjects is Jeff, the story’s narrator. Jeff, like the other ‘inmates’ at Spiderhead, is serving time for a heinous crime. Does this crime justify the shocking – and darkly funny, I also have to mention – tests that he and the others are subjected to? Such are the epic moral conundrums that fuel the bulk of Saunders’ fictions.

What makes ‘Escape From Spiderhead’ more of a must-read than a dozen other Saunders stories I could name? Honestly, it’s a flip of the coin. What I love about his writing, what will keep me signed up for anything he writes, is his roaring imagination, his anarchic wit. Here, that combo is not so much cranked up to eleven but shatters the dial. It’s a mad story, an insane story, and that’s kind of the point.

‘Escape From Spiderhead’ contains another feature of a Saunders story: the gradual shift from being almost a piss-take of his hapless characters, to a deepening that occurs late, a plumbing of his characters’ humanity in the face of the American capitalism that degrades them at every turn. For Jeff, that occurs when Darkenfloxx enters the scene – a drug that sends recipients into lethal fits of rage. When told to administer a fellow inmate with Darkenfloxx, Jeff is faced with a decision. That decision leads to one of the most brutal yet strangely uplifting endings I’ve ever read.

Honourable mentions:

‘Moonfish’ by Shaun Tan, ‘One Night’ by Wayne Macauley, ‘Last Night’ by James Salter, ‘The Dragon’ by Vladimir Nabokov, ‘The Wall’ by Julie Koh, ‘Rush’ and ‘Octopus’ by Nic Low, ‘The Lottery’ by Shirley Jackson, ‘The Lottery’ by Marjorie Barnard, ‘A Short Story’ by Ryan O’Neill, ‘A Quiet Call’ by Andrew Roff.

Wayne Marshall’s stories have appeared in Going Down Swinging, Kill Your Darlings, Island, Review of Australian Fiction, and other places. His story collection Shirl (then Frontier Sport) was shortlisted for the 2019 Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for an Unpublished Manuscript and was published in February 2020 by Affirm Press. He is the co-founder of the Peter Carey Short Story Award and lives in regional Victoria with his partner and two daughters.

March 24, 2020

Five Short Stories You Must Read - By Emily Paull

A good short story is like a gentle stroke of the head, culminating in a punch to the guts. Think you know what’s really going on? Think again. You’ll agree that my love of magical realism really comes out in the selection of must-read stories that I have for you today…

1. The Great Awake by Julia Armfield (from the collection Salt Slow)

This whole collection is incredible, and I wanted to link for you one of the first two stories in the book (the first story is called Mantis) because both have stayed with me long after finishing. Julia’s collection is dark and witty and looks at things like body autonomy and difference with such a fresh perspective. I enjoy her sense of humour very much—including the Anne of Cleves joke in her Twitter bio.

2. Cat Person by Kristen Roupenian (from the collection You Know You Want This)

This collection was a lot better than I had any right to expect it to be, especially after this story, Cat Person, went viral. You’ve probably read it before, but there’s a reason so many people read it and shared it. Read it again, and then go and read the collection as a whole.

3. Gender Studies by Curtis Sittenfield (From You Think It, I’ll Say It)

Another incredible collection. I think I’m discovering that collections have more of an impact on me than individual stories as far as what sticks in the memory…

4. Where are you going, where have you been by Joyce Carol Oates

I mean, it’s iconic for a reason.

5. The Elements by Laura Elvery (from Trick of the Light)

One of the only examples I can think of where an historical fiction short story has been done so well.

Emily Paull is a former-bookseller and future-librarian from Perth who writes short stories and historical fiction. Her work has appeared in numerous anthologies as well as Westerly journal. When she’s not writing, she can often be found with her nose in a book. Her debut short story collection, Well Behaved Women was published in late 2019 by Margaret River Press.

February 18, 2020

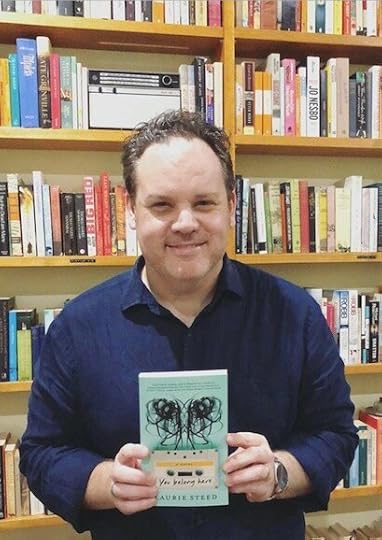

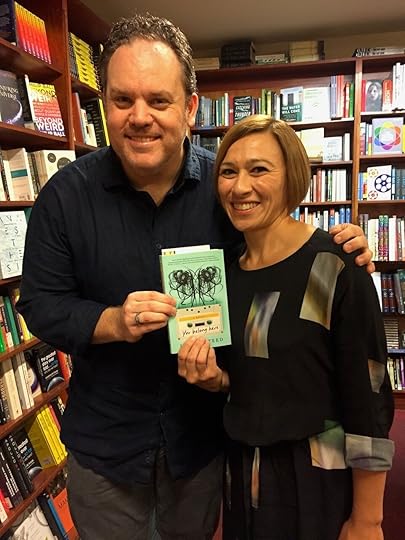

From You Belong Here to Nova: A Photographic Retrospective

It’s been two years since You Belong Here was published, and I’ve now completed, Book two, Nova, for submission. How does that make me feel? Excited. Terrified. Grateful.

Thanks for taking the journey with me.

July 14, 2019

The Long and the Shortlist

It seems that something surprising happens every month in the life of Laurie Steed. In June, and specifically, on the afternoon of June 4th, my debut novel, You Belong Here, was shortlisted for the WA Premier's Book Awards, with the winner to be announced in late July.

I'm delighted by the news. I also feel incredibly grateful; while I'm ecstatic to have been shortlisted, there are many talented WA writers who wrote great books but who missed out this time around. In all of this, I think, there is a lot of hard work but also a bit of luck, and so I take the win with gratitude, and keep writing, in search of my next story, or moment of joy.

I'm partly so delighted (and a little relieved) by the recent shortlisting because I spent so long with this book, eight years in total by the time it was published. I don't know if the book is great on an objective level, but it is my book, just as it is yours, for those of you who have read the book and shared the journey.

My most invaluable feedback has come from those who knew the place and time of You Belong Here, and so felt drawn back to that space. Nostalgia often gets a bad rap in today's society. And yet, our memories are the one thing that connects us all to this place and this time, ranging from our first cup of Milo through to the roads we drove to get to a girlfriend or boyfriend's house. With songs, that's doubly the case, andYou Belong Here is nothing if not a family mixtape that wanted to honour Perth, and the people of Perth in my own unique way.

While the recent shortlisting is incredibly exciting, I'm just as buoyed by readers' responses, and the ways in which the book brought people back into my life: my aunt Flo and cousin Alexandra, continents away but keen to read my words; my friend from high school, Alex, stopping around for a coffee the day before release, and tossing my baby boy up in the air, firm-hands catching him safely; a former writing friend, Jean, who'd been at the first ever writing workshop I took, and who came to the Perth launch to celebrate with me in person.

Nothing beats that. For me, it's like someone took John Parr's 'St. Elmo's Fire (Man in Motion)', added the click-clack of Spokey-Dokeys, threw splotches of that bright Stackhat orange colour you so rarely see around anymore and labelled it 'life'. It's real, alive, flawed and faultless, all at once.

Thank you to anyone and everyone who has read and appreciated my book. As authors, there’s nothing more heartening than a person who reads your words, sees your world, and says, ‘Yes. I know what that feels like.’

November 3, 2018

Thank You

Being an independent author can be tough, in that those books brought out by larger publishers have sales, marketing, rights and publicity departments. My publisher, Caroline Wood of Margaret River Press, does all of these things with a skeleton staff and on a much smaller scale and budget. The benefit of this is that we have a personal, supportive relationship, and she's my greatest champion. The downside is that it's much harder for my book to get traction, interest and coverage when pitted against entire departments of industry professionals.

So how did I do, despite all of this? All told, I'm grateful both for the opportunities that surfaced (I was pretty flawed by a feature in The Australian and my goofy grin staring back at me in the Saturday Herald Sun) and for the people who reached out to me. Wherever I went, be it a library, festival, or just checking my emails, someone said, 'Your book moved me, and I wanted to let you know.' Some people seemed like real-life versions of my characters. Others were just sound, soulful people. I will never forget a single one of them, or the chance they gave to share my world and words.

Because I had such an amazing time with my debut novel, I wanted to do something to say thank you. And it turns out that those video editing skills I picked up in my undergraduate degree at ECU proved beneficial in the long-run! So here, before I share it to the world, is a video I made about a book, and some, if not all of the many folks who made the journey so special.

Thank you, always.

October 9, 2018

Killing it for 10 Years!

The five or so people who’ve been following my writing career for at least ten years (hi Simon, Kate, Jean, Ryan and Les!) know that literary journal Kill Your Darlings published my non-fiction at an early stage, a hilarious (my words) take on Chuck that also included an insightful (my words) analysis of product placement and gender roles within the show. Since then, they selected me as one of their inaugural literary critics, and more recently, featured You Belong Here as their book of the month.

It is incredibly tough to keep a journal running for ten years. Kill Your Darlings aren’t the only independent journal to have done this (The Lifted Brow, Going Down Swinging, and Untitled have all fought the good fight for similar lengths of time) but like these journals, they’ve added, and continue to add something unique to the literary landscape. As such, they’re looking for support to continue the mission they began nearly ten years ago.

Their fundraising prizes for this project are outstanding, incidentally, so if you give money, you’re really just buying yourself a great present. Check them out here but be quick; a lot of great prizes have already been snapped up, so you’ll need to get your sneakers on to avoid missing out.

Thank you to Rebecca Starford, Hannah Kent, Estelle Tang, Alice Cottrell, Ellen Cregan, Meaghan Dew and everyone else I’ve worked with at Kill Your Darlings over the years. Your energy and enthusiasm for KYD is both refreshing and inspiring; may it always be so.

August 6, 2018

Jobs Writers Do When They're Not Writing - Barman

So I worked a little job as a barman. In Scotland. In winter.

The good news is that they played the current music of the time, and you’d be surprised how much ‘Livin’ La Vida Loca’ grows on you after the 58th listen, and how, if you block your ears, Lou Bega's ‘Mambo No. 5' is pretty much ‘Eine Kleine Nachtmusik' but with more trumpet.

So I worked a little job as a barman, and everyone was Scottish, even the barmaids. Their drinks were beer (‘A Pint of Heavy,') beer (‘Aye Ken, I dinnae order nae buttery!') vodka and Irn Bru, and some cocktail that tasted like Robitussin, that was only to be bought for your fiancé, or some guy from Celtic who may or not have kicked the winning goal against Rangers.

Courtship rituals consisted of shouting swear words into your potential partner’s ear, while Will Smith’s ‘Miami’ played really loud. The bar girls were given note tips, sometimes five, ten pounds. By the end of the night, they'd have twenty, twenty-five quid.

I’d have one pound seventy, give or take a pound seventy.

My barmaid in arms, Luce Penny, broke glasses; this thing that she did while trying desperately to be Tom Cruise in Cocktail, arms blocking imaginary punches, a start-stop body-pop that inevitably ended in a smash.

Aaron filled the fridges, and Morvern was some sort of sorceress from Lord of the Rings, who just happened to be working in a bar, and, being the only bar maid who wasn’t regularly breaking glasses and yelling ‘faaaark!’ at the top of her voice, was pretty much the holy grail. That is, were she not already going out with the manager, Jamie. Who was not all that handsome but was definitely a manager. Whereas Aaron and I were not management material. We weren’t even allowed to do stocktake unless Jamie was there with the key to the back room cupboard.

Learning Scottish was hard, partly because things rarely had the one word to describe them, but also because I could never tell if someone wanted to fight me or french kiss me, and often they wanted to do both, because that’s what vodka and Irn Bru will do to most folk in a strong enough dose.

Did I write much while working there? I did. One time I wrote ‘Fuck off’ in capital letters to show to Des, a guy with a bald head and a bald gut that used to poke out from the bottom of his soccer shirt as if to say, ‘Peek-a-boo!’ Another time I wrote ‘Please turn off that poxy Lou Bega/Ricky Martin/Spice Girls hot-mess nonsense,’ and handed it to the DJ, but he just shrugged his shoulders as if to say, ‘Oops, I did it again, I made you believe we're more than just friends.'

I worked there for the longest time. We’re talking three, four weeks. Did I ever pull? Yep, I pulled at least three hundred pints, around two hundred of which had massive heads of foam on top. Did I pick-up? Yep, I picked up all the broken glass that exploded around Luce, and only cut myself say three, four hundred times.

Should you work at a bar? Well, that depends. If you think people are nice and you want to cure yourself of that then, by all means, find your way to the rubber, slip-free floor. If you're not familiar with ‘Flower of Scotland,' and you want to hear it sung by a man as you try to shove him out of the front door, then this is your job.

But if you’re in it for the tips, then I’d try something more potentially lucrative, like cleaning the Dundee public toilets, or shouting on a corner, yelling, ‘Pay me.’