Bridget McKenna's Blog

January 29, 2015

Hail to the King - How I Wrote “A King in Exile”

I just published my short story “A King in Exile” to

Amazon

,

iBooks

,

Kobo

,

Scribd

, and

Barnes & Noble

. You can buy it for 99c or the local equivalent, or

sign up for my newsletter and get it for free

.

What follows is my afterword to the story, which is included in the e-book, directly following the story proper. One paragraph has been deleted to avoid spoilers. I hate spoilers.

Nanyangosaurus Like most kids I’ve ever known, I loved dinosaurs. I read about them, I drew pictures of them, I memorized their strange, romantic names, and I dreamed of unearthing their bones. At the age of nine, I knew I was headed for a career in paleontology. As it happens, I was actually headed for a career in writing and editing, so eventually, I suppose, those two paths wanted to cross. One day decades after I had abandoned my paleontological dreams, I found myself wondering what kind of person might logically find herself in possession of a mysterious egg and bring a living, breathing piece of the cretaceous into Victorian London.

Nanyangosaurus Like most kids I’ve ever known, I loved dinosaurs. I read about them, I drew pictures of them, I memorized their strange, romantic names, and I dreamed of unearthing their bones. At the age of nine, I knew I was headed for a career in paleontology. As it happens, I was actually headed for a career in writing and editing, so eventually, I suppose, those two paths wanted to cross. One day decades after I had abandoned my paleontological dreams, I found myself wondering what kind of person might logically find herself in possession of a mysterious egg and bring a living, breathing piece of the cretaceous into Victorian London.

As ideas about the story began to come together in my mind, I grew excited about the places it might go. I was relatively new to writing, and had not yet made my first fiction sale. In my unbridled enthusiasm, I gave an elevator pitch to someone who told me all the reasons the idea was a bad one, why the story was unbelievable, and why it would be a waste of my time to write it. Some time later, Algis Budrys would offer some advice he’d picked up watching the behavior of writers at workshops. He said to keep your story ideas close to your chest unless you know the person you’re talking to won’t try to critique it. An idea can always be shot full of holes, he said. Once it’s written, peer critiques can be helpful. Until then, you risk letting someone convince you to kill what could have been a perfectly good story.

Some time later, Algis Budrys would offer some advice he’d picked up watching the behavior of writers at workshops. He said to keep your story ideas close to your chest unless you know the person you’re talking to won’t try to critique it. An idea can always be shot full of holes, he said. Once it’s written, peer critiques can be helpful. Until then, you risk letting someone convince you to kill what could have been a perfectly good story.

But I hadn’t yet heard that excellent advice, and so I took my friend’s criticism to heart and decided, with much regret, that however much I loved my idea, I didn’t have a viable story after all. I locked it away in the back of my mind for years.

Afrovenator Enter Lorelei Shannon, gaming industry colleague, fellow writer, good friend, and goth punk chick extraordinaire. She’s quite knowledgeable about many facets of Victorian society, so one day I mentioned my idea and told her why I’d never written the story. She begged me to disregard what I’d heard before and write it anyway. She pointed out all the ways in which the advice I’d received long ago was wrong. She offered suggestions based on her studies of the lives of women in Victorian England and breathed new life into my old idea until I was ready to begin again. I sat down at my keyboard with renewed enthusiasm for my idea, my setting, and my characters—Lady Penelope, John Maguire, and of course, Rex. The young Lady Penelope who came to life in my mind was a bit of a fish out of water as a gentleman’s daughter in mid-19th-century England. She was independent, courageous, adventurous in the extreme, and not a particularly good risk on the marriage market. John Maguire, a junior solicitor far from his home in Ireland, seemed a likely candidate to see in her what other young men of her acquaintance could not. He was also from a lower social class, and being Irish set him down yet another rung on the societal ladder, so he could not be considered a prospective husband.

Afrovenator Enter Lorelei Shannon, gaming industry colleague, fellow writer, good friend, and goth punk chick extraordinaire. She’s quite knowledgeable about many facets of Victorian society, so one day I mentioned my idea and told her why I’d never written the story. She begged me to disregard what I’d heard before and write it anyway. She pointed out all the ways in which the advice I’d received long ago was wrong. She offered suggestions based on her studies of the lives of women in Victorian England and breathed new life into my old idea until I was ready to begin again. I sat down at my keyboard with renewed enthusiasm for my idea, my setting, and my characters—Lady Penelope, John Maguire, and of course, Rex. The young Lady Penelope who came to life in my mind was a bit of a fish out of water as a gentleman’s daughter in mid-19th-century England. She was independent, courageous, adventurous in the extreme, and not a particularly good risk on the marriage market. John Maguire, a junior solicitor far from his home in Ireland, seemed a likely candidate to see in her what other young men of her acquaintance could not. He was also from a lower social class, and being Irish set him down yet another rung on the societal ladder, so he could not be considered a prospective husband.

I DELETED ONE PARAGRAPH FROM THE BLOG VERSION BECAUSE SPOILERS!

My portrayal of Rex owes a lot to Predatory Dinosaurs of the World: A Complete Illustrated Guide by Gregory S. Paul, which was always at the top of a tall stack of reference books teetering near my desk as I wrote. I wanted my dinosaur character to live and breathe, unlike the stuffy, stodgy Victorian sculptures displayed on the grounds of the Crystal Palace that influenced popular and scientific thinking about dinosaurs for generations. I wanted to bring a living creature of the steamy, lush cretaceous to live in a time and place impossibly foreign to his kind, then watch what happened next.

What happened was a love story. The more I wrote, the more the story filled up and spilled over with love—love expressed and unexpressed, love that conquered millennia and love that prevailed over death itself. The love these characters bore one another wove in and out of their experiences and adventures together to become the heart and soul of “A King in Exile.”

To get a free copy of “A King in Exile,” including the afterword complete with the spoilerific paragraph deleted here, sign up for my newsletter.

To get a free copy of “A King in Exile,” including the afterword complete with the spoilerific paragraph deleted here, sign up for my newsletter.

What follows is my afterword to the story, which is included in the e-book, directly following the story proper. One paragraph has been deleted to avoid spoilers. I hate spoilers.

Nanyangosaurus Like most kids I’ve ever known, I loved dinosaurs. I read about them, I drew pictures of them, I memorized their strange, romantic names, and I dreamed of unearthing their bones. At the age of nine, I knew I was headed for a career in paleontology. As it happens, I was actually headed for a career in writing and editing, so eventually, I suppose, those two paths wanted to cross. One day decades after I had abandoned my paleontological dreams, I found myself wondering what kind of person might logically find herself in possession of a mysterious egg and bring a living, breathing piece of the cretaceous into Victorian London.

Nanyangosaurus Like most kids I’ve ever known, I loved dinosaurs. I read about them, I drew pictures of them, I memorized their strange, romantic names, and I dreamed of unearthing their bones. At the age of nine, I knew I was headed for a career in paleontology. As it happens, I was actually headed for a career in writing and editing, so eventually, I suppose, those two paths wanted to cross. One day decades after I had abandoned my paleontological dreams, I found myself wondering what kind of person might logically find herself in possession of a mysterious egg and bring a living, breathing piece of the cretaceous into Victorian London.As ideas about the story began to come together in my mind, I grew excited about the places it might go. I was relatively new to writing, and had not yet made my first fiction sale. In my unbridled enthusiasm, I gave an elevator pitch to someone who told me all the reasons the idea was a bad one, why the story was unbelievable, and why it would be a waste of my time to write it.

Some time later, Algis Budrys would offer some advice he’d picked up watching the behavior of writers at workshops. He said to keep your story ideas close to your chest unless you know the person you’re talking to won’t try to critique it. An idea can always be shot full of holes, he said. Once it’s written, peer critiques can be helpful. Until then, you risk letting someone convince you to kill what could have been a perfectly good story.

Some time later, Algis Budrys would offer some advice he’d picked up watching the behavior of writers at workshops. He said to keep your story ideas close to your chest unless you know the person you’re talking to won’t try to critique it. An idea can always be shot full of holes, he said. Once it’s written, peer critiques can be helpful. Until then, you risk letting someone convince you to kill what could have been a perfectly good story.But I hadn’t yet heard that excellent advice, and so I took my friend’s criticism to heart and decided, with much regret, that however much I loved my idea, I didn’t have a viable story after all. I locked it away in the back of my mind for years.

Afrovenator Enter Lorelei Shannon, gaming industry colleague, fellow writer, good friend, and goth punk chick extraordinaire. She’s quite knowledgeable about many facets of Victorian society, so one day I mentioned my idea and told her why I’d never written the story. She begged me to disregard what I’d heard before and write it anyway. She pointed out all the ways in which the advice I’d received long ago was wrong. She offered suggestions based on her studies of the lives of women in Victorian England and breathed new life into my old idea until I was ready to begin again. I sat down at my keyboard with renewed enthusiasm for my idea, my setting, and my characters—Lady Penelope, John Maguire, and of course, Rex. The young Lady Penelope who came to life in my mind was a bit of a fish out of water as a gentleman’s daughter in mid-19th-century England. She was independent, courageous, adventurous in the extreme, and not a particularly good risk on the marriage market. John Maguire, a junior solicitor far from his home in Ireland, seemed a likely candidate to see in her what other young men of her acquaintance could not. He was also from a lower social class, and being Irish set him down yet another rung on the societal ladder, so he could not be considered a prospective husband.

Afrovenator Enter Lorelei Shannon, gaming industry colleague, fellow writer, good friend, and goth punk chick extraordinaire. She’s quite knowledgeable about many facets of Victorian society, so one day I mentioned my idea and told her why I’d never written the story. She begged me to disregard what I’d heard before and write it anyway. She pointed out all the ways in which the advice I’d received long ago was wrong. She offered suggestions based on her studies of the lives of women in Victorian England and breathed new life into my old idea until I was ready to begin again. I sat down at my keyboard with renewed enthusiasm for my idea, my setting, and my characters—Lady Penelope, John Maguire, and of course, Rex. The young Lady Penelope who came to life in my mind was a bit of a fish out of water as a gentleman’s daughter in mid-19th-century England. She was independent, courageous, adventurous in the extreme, and not a particularly good risk on the marriage market. John Maguire, a junior solicitor far from his home in Ireland, seemed a likely candidate to see in her what other young men of her acquaintance could not. He was also from a lower social class, and being Irish set him down yet another rung on the societal ladder, so he could not be considered a prospective husband.I DELETED ONE PARAGRAPH FROM THE BLOG VERSION BECAUSE SPOILERS!

My portrayal of Rex owes a lot to Predatory Dinosaurs of the World: A Complete Illustrated Guide by Gregory S. Paul, which was always at the top of a tall stack of reference books teetering near my desk as I wrote. I wanted my dinosaur character to live and breathe, unlike the stuffy, stodgy Victorian sculptures displayed on the grounds of the Crystal Palace that influenced popular and scientific thinking about dinosaurs for generations. I wanted to bring a living creature of the steamy, lush cretaceous to live in a time and place impossibly foreign to his kind, then watch what happened next.

What happened was a love story. The more I wrote, the more the story filled up and spilled over with love—love expressed and unexpressed, love that conquered millennia and love that prevailed over death itself. The love these characters bore one another wove in and out of their experiences and adventures together to become the heart and soul of “A King in Exile.”

To get a free copy of “A King in Exile,” including the afterword complete with the spoilerific paragraph deleted here, sign up for my newsletter.

To get a free copy of “A King in Exile,” including the afterword complete with the spoilerific paragraph deleted here, sign up for my newsletter.

Published on January 29, 2015 10:08

March 5, 2014

Why I Didn't Keep Reading Your Book, Part 2

Golden City - Zone 1 Design Dear Anonymous Writer,

Golden City - Zone 1 Design Dear Anonymous Writer,Recently your book broke into the top 1000 on Amazon’s sales rankings, and went considerably higher in your subgenres despite having an unprofessional cover and dull, repetitive sales copy. I admit I was curious about such an unlikely combination, but what ultimately steered me inside was the first line of your book description, which reads “Professionally edited.” I’m an editor as it happens, and you piqued my curiosity by putting that information up front. I wanted to see whether—despite a poor first impression—the level of your writing and an editor’s professional help had produced a readable book.

Your formatting was clean but uninteresting—chapter headers underlined in your word processor, no bolding or other treatment to make the chapter title stand out. Taking the time to observe how professionally formatted books look would have helped you a lot here. But while it’s a good idea to have attractive formatting, the look of your pages isn’t as important as the quality of your work. I still held out hope for good writing. But not for long.

Widow - Zone 1 Design Your opening sentence demonstrated that you don’t know the difference between “number,” which is used to describe things that can be counted, such as fenceposts and birds, and “amount,” which is used to describe something functionally impossible to count, like water or sand. So “a large amount of birds” flapping around the very first line of your book didn’t fill me with a sense of promise for your writing or a lot of respect for your editor. I’ll never know whether you told a good story—what I found in the few pages convinced me you couldn’t write well enough for the quality of the story to make a difference to me. The best story in the world won’t survive poor writing. At least that’s true for me as a reader; your mileage may well vary.

Widow - Zone 1 Design Your opening sentence demonstrated that you don’t know the difference between “number,” which is used to describe things that can be counted, such as fenceposts and birds, and “amount,” which is used to describe something functionally impossible to count, like water or sand. So “a large amount of birds” flapping around the very first line of your book didn’t fill me with a sense of promise for your writing or a lot of respect for your editor. I’ll never know whether you told a good story—what I found in the few pages convinced me you couldn’t write well enough for the quality of the story to make a difference to me. The best story in the world won’t survive poor writing. At least that’s true for me as a reader; your mileage may well vary.I set out to read one chapter—about 15 pages—wondering if I would find anything to impel me into a second one. I didn’t. Long before I finished the chapter I knew I wasn’t buying your book, but just to see whether some very simple copy-editing might make a difference on the prose level, I ran that opening chapter through a few steps from the Self-Editing Checklist included at the back of The Little Book of Self-Editing (or free here ).

Crossing - Zone 1 Design As many of my readers know, I think the verb “to be” is the weakest and most unnecessary verb a writer can use. I call it a “

vampire verb

.” Sure, there are times when it’s the right word for the job, but far more often than not, a sentence containing “was” or “were” can be rewritten to feature a more active verb that conveys more interest and information to your readers. In your first chapter you used “was” and “were” a total of 190 times. That’s a lot of vampires for 15 pages. If I’d been your editor, I’d have suggested you stake most of them.

Crossing - Zone 1 Design As many of my readers know, I think the verb “to be” is the weakest and most unnecessary verb a writer can use. I call it a “

vampire verb

.” Sure, there are times when it’s the right word for the job, but far more often than not, a sentence containing “was” or “were” can be rewritten to feature a more active verb that conveys more interest and information to your readers. In your first chapter you used “was” and “were” a total of 190 times. That’s a lot of vampires for 15 pages. If I’d been your editor, I’d have suggested you stake most of them.You tended to use “had” to write descriptions, as in “the dog had long legs,” and “he had a deep voice,” (not actual quotes, but similar to what you did half a dozen times in your first chapter). When used this way (rather than to establish past perfect tense), “had” is what I call a “ zombie verb .” It lurches along where another verb would stride, skip, skitter, or sprint, and it takes a big bite out of your readers’ involvement in your story.

Early on, I noticed a lot of instances of “that.” “That” is one of those weakener words . It’s sometimes necessary, but more often not. In the first chapter you used “that” 102 times. It seemed like an extraordinary number, so I reviewed them. At a glance, I would have let 37 of them remain.

Prairie Sunset - Zone 1 Design “Then” is another over-used word that weakens sentences, especially in “and then” and “but then” combinations. Of 15 “then” uses in the first chapter, you combined it with “and” or “but” 13 times. That was 13 times too many.

Prairie Sunset - Zone 1 Design “Then” is another over-used word that weakens sentences, especially in “and then” and “but then” combinations. Of 15 “then” uses in the first chapter, you combined it with “and” or “but” 13 times. That was 13 times too many.Another quick search revealed a dozen instances of “began to,” and several each of “tried to,” “started to,” and “continued to.” These kinds of filler words weaken writing and distance readers from a direct sensory experience of what they're reading . When you want to show a character doing or saying something, just have them do it. Not “He began to wave the gun around,” but “He waved the gun around.” Involve your readers by showing them what’s actually happening in the story right now.

I know what I have to say here probably means little to a writer whose book sits high on the sales rankings and sports lots of enthusiastic 4- and 5-star reviews alongside those bemoaning the weakness of the writing and story. It’s obvious a lot of the people who bought your book don't care about those things, but how many potential readers never got past the first few pages? I think there’s a lot wrong with your level of writing skill besides the few things I pointed out here, but if you keep a learner’s mind you’ll improve as you do more of it. Oh, and I hope you find a better editor.

—Bridget McKenna

Published on March 05, 2014 07:56

February 26, 2014

Why I Didn't Keep Reading Your Book, Part 1

Ophelia - Zone1Design.com Dear Writer Who Shall be Anonymous,

Ophelia - Zone1Design.com Dear Writer Who Shall be Anonymous,Why, oh why couldn’t I get past the third page of your book? Your cover was frankly awesome. The price—on a special deal from Amazon—was quite reasonable. Your sell copy was engaging and well-written; I had no choice but to click the cover image and start reading, fully expecting to buy the book and its sequel within the next few minutes.

Some thought had gone into the interior design, a fact that tends to increase my confidence in a book. There were some odd choices, like scene-break graphics crowded right up against the text at top and bottom, but I was willing to chalk them up to the vagaries of the previewing tool. And as annoying as they are, formatting errors don’t necessarily mean anything about writing or storytelling. So I started to read.

Woods Walkers - Zone1Design.com The first verb in the first line was “was.” The main character “was” something or other. Points off, but I’ve read some good books whose authors didn’t start with an action verb, so I overlooked this particular peeve and went on.

Woods Walkers - Zone1Design.com The first verb in the first line was “was.” The main character “was” something or other. Points off, but I’ve read some good books whose authors didn’t start with an action verb, so I overlooked this particular peeve and went on.In the second line, you told me what the viewpoint character was feeling. You went on to describe a setting that would have justified that emotion, so you could have let me deduce the character’s feelings from your description of the setting from her viewpoint, or by showing me her reaction to it. Instead, you told me. My friend, that was a rookie mistake that a good editor would have marked. Yours apparently did not. In the next sentence you did it again. The snowball had begun its downhill roll.

Millionaire - Zone1Design.com In the third paragraph you served up a weak verb/adverb combo where a good verb standing alone would have done a far better job for your narrative, only you didn’t take the time to find and use one. You did it again in the fourth paragraph and in the fifth. At this point I knew I wasn’t buying your book for any price. However good the story might be, my experience of it would have been ruined by constantly bumping up against writing too weak to carry it.

Millionaire - Zone1Design.com In the third paragraph you served up a weak verb/adverb combo where a good verb standing alone would have done a far better job for your narrative, only you didn’t take the time to find and use one. You did it again in the fourth paragraph and in the fifth. At this point I knew I wasn’t buying your book for any price. However good the story might be, my experience of it would have been ruined by constantly bumping up against writing too weak to carry it.Still, curiosity kept me reading as you mashed up several years of the protagonist’s backstory into one indigestible six-paragraph narrative lump rather than letting me discover it over time, revealed as needed in narrative or dialogue as you moved the story forward. Even curiosity couldn’t get me past that. Amazon chose your book for one of their imprints, so clearly they had confidence in it, but it was confidence I no longer shared.

Memories - Zone1Design.com I can't say I'll never pick up another of your books. I closed that one so fast I don't remember its title or your name, so I very well might read another sample of yours someday, but unless your writing improves a great deal, I probably won't get any further than I did this time.

Memories - Zone1Design.com I can't say I'll never pick up another of your books. I closed that one so fast I don't remember its title or your name, so I very well might read another sample of yours someday, but unless your writing improves a great deal, I probably won't get any further than I did this time.It's not personal, but my reading time is limited and life's way too short to wince my way through a book I'm not enjoying at any price, including free. If you want my money, my time, and my attention, you're going to have to bring a better game.

Sincerely,

Bridget McKenna

The Little Book of Self-Editing for Writers

Pre-made bookcovers by Zone 1 Design

Published on February 26, 2014 07:13

September 3, 2013

Self-Editing for Everyone Part 12: Point of View Violations

It's all in your point of view With this article, the last in the series, could it be we’ve reached the end of our self-editing journey together? Possibly not. I’m using these 12 articles to revise and expand

The Little Book of Self-Editing for Writers

(

UK

,

CA

). Look for the new version later this year.

It's all in your point of view With this article, the last in the series, could it be we’ve reached the end of our self-editing journey together? Possibly not. I’m using these 12 articles to revise and expand

The Little Book of Self-Editing for Writers

(

UK

,

CA

). Look for the new version later this year.Nearly every word in these 12 articles will be included in the new version, along with other material that’s not part of this series. The price of the book will go up a bit after publication in autumn 2013, but here’s the cool thing: if you buy the book on Amazon for $.2.99 before the new version comes out, you’ll be able to update your existing book without spending a cent using the Manage Your Kindle feature inside your Amazon account. When the new version is published, that page will tell you there’s an update available for your book, and you can go to your account and download it. As far as I know, this feature isn’t yet available to buyers at other e-book retailers.

You don’t need a Kindle to read Kindle books—you can read ’em on your computer, tablet, or phone. Meanwhile, help yourself to a free Self-Editing Quick Reference , in .doc or .PDF.

Now back to our regularly-scheduled program.

One mind, one pair of eyes, one viewpoint Point of View

One mind, one pair of eyes, one viewpoint Point of ViewLike the director of a film, an author uses viewpoint to direct the reader’s attention. Viewpoint is how the reader experiences your story through the senses and thoughts of another person. When done well, it’s pretty nearly invisible.

It’s not within the scope of this article to discuss the myriad aspects of viewpoint in detail, but rather to discuss the ways in which you can recognize and fix those places where your handling of Point of View (POV) may have gone off the tracks.

Note:

My advice here is aimed at writers who like to write from a particular point of view and stay there until they switch to another, usually at a scene or chapter break. I realize that there are writers who like to switch from one viewpoint to another all through a scene or chapter, but most writing advice, including mine, recommends otherwise.

I’m of the school of writing that prefers to stay in one point of view until the reader needs information or insights that must come from another, then make the transition only at a clear break in the narrative, such as the end of a chapter. In my opinion this enables the reader to more closely identify with each character, and to know more of his goals and inner tensions. Each point of view also drives the narrative voice, and switching from one to another within a scene, in my opinion, dilutes the impact of that voice.

Each POV a worldview, each worldview a universe A View of the Universe

Each POV a worldview, each worldview a universe A View of the UniverseEvery fictional viewpoint is also a worldview. That’s one reason it’s wise, in my opinion, to remain in one character’s POV for the length of a chapter or at least a scene that’s clearly marked with a visible scene break from the next. This allows the reader to feel anchored in that character’s story, and avoids confusion between viewpoints.

Here’s an exchange which switches POV between one paragraph and the next.

Cody had his doubts about Mina’s intentions. “Are you sure? You’re not going to change your mind later?”

“Of course I’m not, dummy.” Mina said. She worried about that boy. Was he going to cause trouble?

“Just stay where I can see you,” Cody told her. He couldn’t risk letting her out of his sight.

“Aye-aye, Cap’n. I’ll go first.” There was a passageway up ahead where she was pretty sure she could lose him.

I don’t know about you, but I feel like a spectator at a tennis match. I’m not at all sure whose story I’m in. If the author remained in one viewpoint until the other was needed, I’d be able to identify more closely with the worldview of one character. And the author would be able to conceal the thoughts and motives of the non-viewpoint character a lot more effectively, because if Mina intends to ditch Cody and the author doesn’t reveal that while in her POV, the reader is going to feel more than a bit cheated. If the author does reveal it, as above, it cheats the reader of a great deal of suspense.

While you’re writing in a particular character’s POV, the reader experiences everything the character does, and nothing the character does not. When you’re not in a character’s POV, you can observe that character’s actions and hear his speech, but have no idea what he’s thinking, seeing, hearing, or feeling.

“What can you tell me about Esparza,” I asked Frank.

“Esparza?” he said, puzzled. “I don’t know anyone named Esparza.”

Since we’re not in Frank’s POV in the example above, the reader can’t know if Frank is puzzled. Fortunately, the writer has made puzzlement clear in Frank's speech, making the blatant mind-read unnecessary.

Give 'em an experience. Viewpoint and Direct Experience

Give 'em an experience. Viewpoint and Direct ExperienceWhile you’re in a particular character’s POV, the character—and by extension the reader—can’t know what any other character sees, hears, or feels. Be consistent in this. If the POV character doesn't experience something, the reader doesn't either. If the character doesn’t have knowledge yet, the reader can’t have that knowledge.

When in a character’s viewpoint, the writer can conceal what the character experiences only in limited ways. Keeping secrets in a third-person point of view is usually considered to be deceiving the reader, but it’s possible to conceal things in a first-person point of view by not reporting every detail when it happens and allowing the unreported detail to come out later.

I knew a lot more when I hung up the phone than I had before I called.

-

The bartender told me what I needed to know. I left a generous tip.

As I've repeated often throughout this self-editing series, let direct sensory experience be your guide. Let your reader directly experience what your POV character does. Don’t tell them. And let them experience what the character is experiencing, not what they’re trying or failing to experience.

Seeing from Outside

Sometimes you may begin a story from no-one’s point of view, rather like an establishing shot in a film. Fairly quickly, however, you’ll focus in on your point-of-view character and stay there. There are other times you might find stylistic reasons to use this approach, and during those times you’re in an unknown narrator’s point of view, you’re seeing your POV character from the outside. If this happens while a character is being introduced, before you reveal their name, you may even use terms like “the young man,” “the surgeon,” “the dark-haired woman.”

Now listen carefully: those are the only times you should view a POV character from the outside, or refer to her in terms that she would not use for herself, though someone else might. Once you know your hero’s name is Lance, for as long as you’re in Lance’s point of view, looking at the world from inside his head, do not refer to him as “the young man,” “the tall man,” “the magician,” or “the cowpoke.” Why? Because those kinds of tags are in an outside point of view, and when you step outside Lance to refer to him, you’re leaving his point of view for one that doesn’t actually exist, and you're throwing the reader out of the reading experience, which is something you very much do not want to do.

Keep your point of view consistent and logical. Your reward will be coherent narration and increased dramatic tension and reader immersion.

TL;DR

Anchor your reader in the story by getting inside one character’s head and staying there until you need information or insight from another character’s viewpoint.

Change viewpoint at clearly marked chapter-or-scene breaks to avoid reader confusion.

The reader can only experience what the viewpoint character does, and nothing the viewpoint character does not.

COVER ART

All the fabulous pulp magazine covers on this article series were created using the amazing Pulp-O-Mizer from art by its creator, Bradley W. Schenck.

Be sure to read the earlier Self-Editing for Everyone articles.

Part 1: The Most-Hated Writing Advice Ever

Part 2: Vampire Verbs, Zombie Verbs, and Verbs that Kick Ass

Part 3: Attack of the Adverbs!

Part 4: The Weakeners

Part 5: When Words Get in the Way

Part 6: Secrets of Relative Velocity

Part 7: Two Languages

Part 8: Dialogue Tags

Part 9: Dangling Modifiers

Part 10: Passive Voice

Part 11: Homophones

Published on September 03, 2013 11:07

August 26, 2013

Self-Editing for Everyone Part 11: Homophones

Know more than your spellchecker. This 11th and penultimate chapter of Self-Editing for Everyone is inspired by and expands upon

The Little Book of Self-Editing for Writers

, available for the price of a 12-oz. latte from

Amazon.com

,

Amazon.co.uk

, and all Amazon stores worldwide as well as

Barnes & Noble

and

Kobo

.

Know more than your spellchecker. This 11th and penultimate chapter of Self-Editing for Everyone is inspired by and expands upon

The Little Book of Self-Editing for Writers

, available for the price of a 12-oz. latte from

Amazon.com

,

Amazon.co.uk

, and all Amazon stores worldwide as well as

Barnes & Noble

and

Kobo

.Homophones: Sounds Like…

Just three days ago, I was eagerly reading a new book—a winner of no fewer than three literary awards, originally published by one of the world’s largest publishing companies. The writing engaged me, and the author was doing a bang-up job with his story and characters. Before I got to the end of the first chapter, however, a band arrived on the scene. They unpacked and began playing their instruments, including a drum and a pair of clashing symbols. “How appropriate,” I thought as I bookmarked an error that had gotten past its author, an acquiring editor, a copyeditor, a proofreader, and the author again correcting page proofs, “that my next article will be about homophones.”

Homophones are words that sound alike but have different meanings. Unlike ordinary misspellings and mis-typings, homophones will walk right past the watchful eye of your spellchecker without even slowing down to show ID. They require careful reading and re-reading to pin down and destroy. The fact that some survive the editorial process to appear in published works means they have escaped the notice of any number of people, including but not limited to the author, a copyeditor, and—amazingly enough—a proofreader. Never assume someone else will find them for you.

Peek, peak, pique Some homophones, like there, their, and they’re, or to, too, and two, pane and pain, sail and sale, ad and add, and even its and it’s are easy to mis-type and easy to miss on a casual editing pass, especially of your own work. Your mind can know the difference, but that won’t stop your fingers from tripping you up and your eyeballs from letting it happen. Be vigilant.

Peek, peak, pique Some homophones, like there, their, and they’re, or to, too, and two, pane and pain, sail and sale, ad and add, and even its and it’s are easy to mis-type and easy to miss on a casual editing pass, especially of your own work. Your mind can know the difference, but that won’t stop your fingers from tripping you up and your eyeballs from letting it happen. Be vigilant.Homophone errors can also result from the writer’s or editor’s confusion over meaning. There are worlds of difference between affect and effect, peak, peek, and pique, born and borne, or discreet and discrete, but you’d be surprised how often they’re used incorrectly by authors and how often they remain uncorrected by any number of people who are being paid to correct them.

Sounds like... But of course YOU know the difference between a miner and a minor, naval and a navel. You know your sachet from a sashay, rain from reign, a taper from a tapir, and a tenner from a tenor. You know whether you’re wreaking or reeking. You do, don’t you? It’s important to know more about the nuances of the language you’re writing in than your spellchecker does, because if the word you need is altar and you use alter, advanced word-processing technology won’t save you. What might is putting extra eyeballs on the job in the form of an eagle-eyed beta reader, a pass by a copyeditor, and a final independent proofing before publication. If you’re hoping for the skills of a traditional publishing house to correct your homophone errors, you should know that the vast majority of the ones I and readers like me have encountered have been in the pages of books from traditional publishers—from professionals whose day job it was to produce clean copy for the finished product. Virtually no book is free of errors, but you can take responsibility for ensuring yours comes as near that elusive (not illusive) goal as your efforts will allow.

Sounds like... But of course YOU know the difference between a miner and a minor, naval and a navel. You know your sachet from a sashay, rain from reign, a taper from a tapir, and a tenner from a tenor. You know whether you’re wreaking or reeking. You do, don’t you? It’s important to know more about the nuances of the language you’re writing in than your spellchecker does, because if the word you need is altar and you use alter, advanced word-processing technology won’t save you. What might is putting extra eyeballs on the job in the form of an eagle-eyed beta reader, a pass by a copyeditor, and a final independent proofing before publication. If you’re hoping for the skills of a traditional publishing house to correct your homophone errors, you should know that the vast majority of the ones I and readers like me have encountered have been in the pages of books from traditional publishers—from professionals whose day job it was to produce clean copy for the finished product. Virtually no book is free of errors, but you can take responsibility for ensuring yours comes as near that elusive (not illusive) goal as your efforts will allow. It foretold the coming of his enemies. If you’re at all fuzzy on the definition of any word you’re using, look it up and confirm you have the right one, lest your hero travel to Cypress, cash his extra passport under the mattress, pour over the secret documents, auger the coming of his foes, fight a dual with several combat-trained Unix, take to the heir dodging flack, land his plain on the wield, be bitten by tics, escape upriver in a skull rowed by experienced semen, and give in to the temptations of vise while awaiting his true love with baited breath.

It foretold the coming of his enemies. If you’re at all fuzzy on the definition of any word you’re using, look it up and confirm you have the right one, lest your hero travel to Cypress, cash his extra passport under the mattress, pour over the secret documents, auger the coming of his foes, fight a dual with several combat-trained Unix, take to the heir dodging flack, land his plain on the wield, be bitten by tics, escape upriver in a skull rowed by experienced semen, and give in to the temptations of vise while awaiting his true love with baited breath.Here’s a short list of the most common homophones not mentioned in the article above.

breach/breech

canvas/canvass

complement/compliment

dental/dentil

desert/dessert

elicit/illicit

fain/feign

faze/phase

fate/fête

filter/philter

gaff/gaffe

gamble/gambol

gibe/jibe

grill/grille

hangar/hanger

hoard/horde

immanent/imminent

lightening/lightning

loath/loathe

palate/pallet/palette

pistil/pistolpsalter/salter

rack/wrack

retch/wretch

rhyme/rime

sear/sere

sensor/censer

sight/site/cite

sink/sync

sight/site

stanch/staunch

straight/strait

trooper/trouper

vale/veil

valance/valence

venous/Venus

vial/vile

wrang/rang

There are hundreds of homophones in English. Take a few minutes to peruse the lists at www.homophone.com . Some are nearly as far-fetched as the adventure above, but many lay avoidable traps for the unwary writer.

TL;DR

Homophones plot your destruction. They won't stop until they've embarrassed you.

It's a good idea to know more about the nuances of the language you're writing in than your spellchecker does.

If you use the wrong word out of ignorance, advanced word-processing technology won't save you. COVER ART

All the fabulous pulp magazine covers on this article series were created using the amazing Pulp-O-Mizer from art by its creator, Bradley W. Schenck.

Be sure to read the earlier Self-Editing for Everyone articles.

Part 1: The Most-Hated Writing Advice Ever

Part 2: Vampire Verbs, Zombie Verbs, and Verbs that Kick Ass

Part 3: Attack of the Adverbs!

Part 4: The Weakeners

Part 5: When Words Get in the Way

Part 6: Secrets of Relative Velocity

Part 7: Two Languages

Part 8: Dialogue Tags

Part 9: Dangling Modifiers

Published on August 26, 2013 07:48

August 19, 2013

Self-Editing for Everyone Part 10: Passive Voice

Self-Editing for Everyone Part 10: Passive Voice is brought to you by the letter

Z

, the number

3

, and

The Little Book of Self-Editing for Writers

, available at

Amazon.com

,

Amazon.co.uk

, and all Amazon stores worldwide, as well as

Barnes & Noble

and

Kobo

. Said a kind reviewer: “It’s the best $2.99 you’ll ever invest in your writing career.”

Self-Editing for Everyone Part 10: Passive Voice is brought to you by the letter

Z

, the number

3

, and

The Little Book of Self-Editing for Writers

, available at

Amazon.com

,

Amazon.co.uk

, and all Amazon stores worldwide, as well as

Barnes & Noble

and

Kobo

. Said a kind reviewer: “It’s the best $2.99 you’ll ever invest in your writing career.”Passive Voice

If you’ve been at this writing lark any time at all, you’ve probably heard that something called “passive voice” is a no-no. That’s almost entirely true. Passive voice should be eliminated wherever possible. (No! The passive—it burns!) Or I should say: strive to keep your sentences active.

The first step for a writer hoping to understand and thereby eliminate the problem of passive voice from her writing is to understand the difference between active and passive sentences.

In an active sentence, the subject is the person (or place or thing) who performs the action of the sentence. If the subject performs the action on someone (or someplace or something), that becomes the object.

The manager handed Maury his ass.

Manager is the subject, Maury (and his ass) are objects.

Paris displayed all her autumn colors along the banks of the Seine.

Paris is the subject. Paris acts on colors, which are the object.

The stone struck Alvin between the eyes.

The stone is the subject. It acts on Alvin, who is the object.

In a sentence in the passive voice, the subject and object may trade places.

Maury got his ass handed to him by the manager.

Maury has become the subject, but he’s not acting; he’s being acted upon by the manager.

All of Paris’s autumn colors were displayed along the banks of the Seine.

The colors have become the subject, but they aren’t doing anything but being displayed. They’ve become passive.

Alvin was struck between the eyes by a stone.

Um...Alvin? DUCK! Alvin has taken on subject duty here, but he has nothing to do in this sentence but stand there and get smacked around by the stone.

Um...Alvin? DUCK! Alvin has taken on subject duty here, but he has nothing to do in this sentence but stand there and get smacked around by the stone.First rule of active sentences: subjects act.

Sometime a passive voice construction has no actor—the object of the sentence is mysteriously acted upon by no-one at all.

Mistakes were made.

Explanations were called for.

The body was moved.

The result, as in the previous examples, is a weak, flabby sentence.

Remember this: someone always has to move the body, and passive voice leeches life from your writing.

It's totally zombies.

Yes, zombies. Again. USMC Ethics Professor Rebecca Johnson famously devised a way to teach her students how to recognize passive voice. If you can add “by zombies” and the sentence still makes sense, it’s passive. Try it!

Yes, zombies. Again. USMC Ethics Professor Rebecca Johnson famously devised a way to teach her students how to recognize passive voice. If you can add “by zombies” and the sentence still makes sense, it’s passive. Try it!Mistakes were made by zombies.

Explanations were called for by zombies.

The body was moved by zombies.

I find this a fun way to discover my own passive voice boo-boos. Product warning: you will find yourself shouting “…by zombies!” a lot while watching television. Or maybe it’s just me.

Passive voice also occurs when the writer doesn’t put a real subject—one capable of performing an action—into the sentence.

There was movement in the bushes.

Note the dread “ was .” “There” is not a subject. If you attempt to force it into acting like one, it teams up with “ to be ” to remove forward motion from your sentence.

Something moved in the bushes.

This is an improvement. “Something,” when it’s not a form of “ the word that wasn’t there ,” can add a sense of mystery and foreboding when used with intention. Another option would be to show what the POV character experienced, and imply with which sense or senses she perceived it. A rule for all writing at all times: take every opportunity to involve the reader’s senses.

Light flittered through the bushes.

A shadow moved in the bushes.

Leaves fluttered in the bushes.

The bushes rustled.

Not just dull—corporate memo dull.

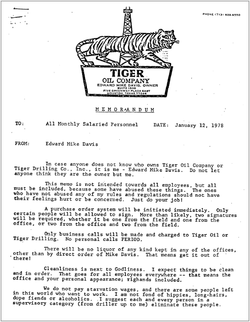

Tiger Oil Memos. NEVER dull. Pic links to the set. Corporate communicators are among the front runners in the passive voice sweepstakes.

Tiger Oil Memos. NEVER dull. Pic links to the set. Corporate communicators are among the front runners in the passive voice sweepstakes.It still needs to be decided what our growth markets will be for the next year.

We understand what’s being conveyed by your marketing message.

Changes must be made in the way we deliver content.

This kind of communication is vague and equivocal. It says “Things must be done!” and not “We must do this thing.” Whatever needs doing is then somehow assumed to be done by some magical means that don't involve anyone actually doing them. This may explain why the other common place to find passive voice is in political writing.

We need to decide…

We understand what you’re conveying…

We must make changes…

The vague sentences now have subjects that act.

Writers sometimes use passive voice in an attempt to make a sentence sound particularly high-flown:

Our intentions must be matched by our actions, or we will do nothing.

The active subject “we” has been pushed almost out of the sentence here. Who must do something? We must. But in a passive construction, doing doesn’t appear to be anyone’s responsibility. It will somehow just…happen.

We must match our intentions to our actions…

Making the sentence active has transformed it into a call to action.

Leonard should have gone to http://undeadlabs.com Leonard was killed.

Leonard should have gone to http://undeadlabs.com Leonard was killed.Who killed Leonard? Apparently no-one. Or zombies. My money’s on zombies.

If passive voice is one of your bad writing habits, you’ll be relieved to know that there are times when it actually works. Use it when you want to show that a character is not an actor in some aspect of his own life, and then in moderation for effect:

Claire would understand, of course—Marcus was certain she would when all was said and done. There were circumstances, after all. Things happened. Mistakes were made.

If you’ve kept passive construction out of your narrative, the reader will understand that this is somehow different and pay closer attention to what you intend by it.

Are there times when it doesn’t matter who the actor is, or when the actor is so generalized that to use the active voice would be to disturb the intention of the turn of phrase? If there is, you’re bound to encounter it someday. But when you think you’ve found it, first try giving the action to a tangible subject and see if that doesn’t clarify your intention. If it doesn’t, give your sentence wholeheartedly to the zombies.

Another Passive Voice

Go. Read. Follow. Seriously.

Go. Read. Follow. Seriously. The Passive Voice BLOG is a passive voice I can totally get behind. If you're an indie author-publisher, indie curious, or just interested in 21st century publishing, you really, really must read it. I can't emphasize loudly enough how important this blog is as a resource and information clearing house for all things 21st century publishing. COVER ART

All the fabulous pulp magazine covers on this article series were created using the amazing Pulp-O-Mizer from art by its creator, Bradley W. Schenck.

Be sure to read the earlier Self-Editing for Everyone articles.

Part 1: The Most-Hated Writing Advice Ever

Part 2: Vampire Verbs, Zombie Verbs, and Verbs that Kick Ass

Part 3: Attack of the Adverbs!

Part 4: The Weakeners

Part 5: When Words Get in the Way

Part 6: Secrets of Relative Velocity

Part 7: Two Languages

Part 8: Dialogue Tags

Part 9: Dangling Modifiers

Thanks for linking to this blog post!

A Novel Experience - Best of the Week's Articles

Did I miss anyone? Let me know!

Published on August 19, 2013 11:24

August 12, 2013

Self-Editing for Everyone Part 9: The Case of the Dangling Modifier

This article is brought to you by

The Little book of Self-Editing for Writers

, available at

Amazon

,

AmazonUK

,

B&N

, and

Kobo

for the paltry sum of $2.99.

This article is brought to you by

The Little book of Self-Editing for Writers

, available at

Amazon

,

AmazonUK

,

B&N

, and

Kobo

for the paltry sum of $2.99.Misplaced Modifiers and Dangling Participles

There’s a reason many writers don’t show their first drafts to anyone but trusted friends—our first-draft errors can be downright embarrassing. And perhaps nothing is more capable of producing unintended giggles than a dangling modifier. Heck, even the name is giggle-worthy. So how and where do modifiers dangle?

Sometimes writers put adjectives and adverbs in places where they inadvertently change the meaning of sentences, often with humorous results.

The rule is: put the modifier immediately before the word you want it to modify.

Modifiers, like shoes, shouldn't dangle. The shiny soldier’s buttons caught and reflected the candlelight.

Modifiers, like shoes, shouldn't dangle. The shiny soldier’s buttons caught and reflected the candlelight.This sentence introduces us to the shiny soldier, whereas the adjective “shiny” here is supposed to be modifying “buttons.”

The soldier’s shiny buttons caught and reflected the candlelight.

I nearly ran six miles this morning before breakfast.

...but something came up and you stayed home? The adverb “nearly” in this sentence is supposed to be modifying “six,” but appears to modify “ran” instead.

I ran nearly six miles this morning before breakfast.

When Participles Dangle

“What the bleedin’ ’eck is a participle?” you might be asking. Let’s get that out of the way first. A participle is a verb doing the work of an adjective.

An adjective is a word that modifies a noun.

A fast horse.

Adjective “fast” modifying noun “horse.”

A participle is a form of a verb that ends in “-ing” and also modifies a noun.

A galloping horse.

Participle “galloping” (from verb “gallop”) modifying noun “horse.”

Beloved of lumberjacks everywhere Participial Phrases for the Rest of Us

Beloved of lumberjacks everywhere Participial Phrases for the Rest of UsA phrase that contains a participle is called—not surprisingly—a participial phrase.

Glancing at her lover

Seeking the shelter of the covered bridge

Buttering a scone

Of course by themselves, those participial phrases aren’t sentences. Their place in a sentence is to modify the subject noun by saying what the subject noun is doing.

Glancing at her lover, Lavinia trod upon the dance instructor’s foot.

Seeking the shelter of the covered bridge, Paul dodged another falling frog.

Buttering a scone, Chris pondered the legality of shooting people who run their lawnmowers at 6 A.M.

If you’ve put a phrase containing a verb at the beginning or end of a sentence, that phrase should modify the nearest noun. When you put something in the way of a participial phrase so that it can’t reach the noun it’s meant to modify, we say it’s dangling. When participles dangle, they do strange things to sentences.

When used correctly, the first phrase modifies the noun in the second phrase, and one flows into the other with no loss of meaning.

Believing herself to be in danger, Melanie notified the police.

Knowing sparks were likely to fly, James decided to avoid the whole discussion.

Don't trust the cute. But when used incorrectly, modifying phrases create unlikely results.

Don't trust the cute. But when used incorrectly, modifying phrases create unlikely results.Fleeing down the darkened alley, Sandra’s handbag fell to the pavement.

Sandra’s handbag was fleeing down the alley.

Fleeing down the darkened alley, Sandra dropped her handbag.

Now the phrase modifies Sandra, as it should. Or you could ditch the participle entirely and use another sort of modifying phrase:

As Sandra fled down the darkened alley, her handbag fell to the pavement.

--

Having been bitten by a Chihuahua, Rollo’s trust in dogs was practically nonexistent.

A dog bit Rollo’s trust. Neat trick, that.

Having been bitten by a Chihuahua, Rollo felt an extreme distrust of dogs.

Now the phrase modifies Rollo, as is right and proper. Ditching the participle:

Ever since a Chihuahua had bitten him, Rollo had been suspicious of dogs.

Keep your modifying words and phrases with the words they modify, and no-one will ever be able to accuse you of illegal dangling.

TL;DR

Dangling modifiers don’t modify what their authors think they do.

To avoid unintentional hilarity, put your adjectives, adverbs, or participles immediately before the words you want them to modify.

COVER ART

All the fabulous pulp magazine covers on this article series were created using the amazing Pulp-O-Mizer from art by its creator, Bradley W. Schenck.

Be sure to read the earlier Self-Editing for Everyone articles.

Part 1: The Most-Hated Writing Advice Ever

Part 2: Vampire Verbs, Zombie Verbs, and Verbs that Kick Ass

Part 3: Attack of the Adverbs!

Part 4: The Weakeners

Part 5: When Words Get in the Way

Part 6: Secrets of Relative Velocity

Part 7: Two Languages

Part 8: Dialogue Tags

Published on August 12, 2013 11:14

August 5, 2013

Self-Editing for Everyone Part 8: Dialogue Tags

Dialogue Tags

Dialogue TagsLong, long ago, in another century, some bored or desperate soul wrote a book of dialogue tags that could be used in preference to “said.” That writer is lost to well-deserved obscurity, but the term “said-bookism” remains to describe the labored alternatives some writers resort to for tagging dialogue.

A few said-book sorts of tags are justly famous for their unlikeliness. Among them:

Smile

“I really enjoyed the play,” Imelda smiled. ...as opposed to...

Imelda smiled. “I really enjoyed the play.”

Imelda can’t smile a speech. But she can say something, and she can smile, adding action to the speech.

Gape

“You can’t be serious,” Robert gaped.

Much like Imelda, Robert can’t gape his words. He can say them and then gape, but why should he? His incredulity is evident from his speech. To repeat it is to court Superfluous Redundancy .

Ejaculate

Yes, “an abrupt, exclamatory utterance” can be defined as an ejaculation, but do yourself a favor; don’t go there. Don’t even look at the price of tickets.

Sometimes you can't say anything. To Say or Not to Say

Sometimes you can't say anything. To Say or Not to SayOf course on widely spaced occasions, fictional characters might remark, comment, shout, shriek, whisper, rasp, hiss, mutter, or growl. For the most part, though, and unless there’s a solid reason to have them do otherwise, they just say stuff. Sometimes they ask stuff, and when they do, someone might reply. The word “said” is the best candidate for readers’ eyes to pass over it if it’s not repeated too often, so it’s a good way to tag dialogue while maintaining immersion. The occasional “told,” “asked,” and “replied” or “answered” are likewise nearly invisible when used with restraint.

To lay a bit of popular internet writing advice to rest, a said-bookism is not “…any word used in place of ‘said.’” “Said” has its own pitfalls and is not the only acceptable dialogue tag. I have nailed my colors to the mast on this one, and will take as many boarders as possible down with me.

“Said”—to get up in the grille of a similar bit of oft-repeated guidance—is not really an invisible word that readers never notice. Too many saids are as annoying as overly-dramatic tags, and readers will notice if you use it too often. How often is too often? You’ll have to play that by ear, and one way to do that is to read some dialogue-heavy portion of your writing out loud. If you feel self-conscious about reading aloud to an empty room (I certainly do, and I figure it’s probably not entirely idiosyncratic), ask your friend, spouse, or dog to listen. Your cat will probably fall asleep, which may affect your confidence.

Another ear-friendly method is to record yourself reading a scene or chapter, then wait a day—or at least overnight—and play back the recording. Excess saids and other awkward items will cry piteously for you to release them from their miserable existence.

Not every line of dialogue needs to be tagged. A well-written fictional conversation can go on for quite a few exchanges without the reader losing his way, especially if the characters have different ways of speaking and/or different goals for the conversation. See Part 6 of this series for an example of a conversation with very few dialogue tags spoken by three characters with three different goals for that scene. Well-written characters with strong intentions put their own stamp on their speeches, much like real people.

Save your tags for a rainy day. Be sparing with dialogue tags. Miserly, even. Use them mainly to avoid confusion as to who’s speaking, and/or to improve the rhythm of a line.

Save your tags for a rainy day. Be sparing with dialogue tags. Miserly, even. Use them mainly to avoid confusion as to who’s speaking, and/or to improve the rhythm of a line.To get extra mileage from a dialogue tag, use it to get in a bit of stage business that either helps reveal character or moves the story forward.

“I’d help you look for him if I could,” Trey said, peering over Haldane’s shoulder for a better look at the paper. “I can’t leave town right now without bringing half the police force behind me.”

—

“He hasn’t been here in days,” Lexie said, letting her eyes slide off to her left, to the darkened hallway. “I’ll tell him you came by.”

Well-written dialogue spoken by well-drawn characters is the heart of any scene, and scenes are the building blocks of your fiction. A vital part of writing good, believable dialogue is knowing how to handle tags with skill and confidence.

TL;DR

Inspect your dialogue for labored tagging that tends to make it over-dramatic.

If every character in your scene is well-defined with a clear intention, you won't need many dialogue tags.

Use dialogue tags—sparingly—to improve rhythm, avoid confusion, include stage business.

Avoid tags like shrieked, sobbed, rasped, hissed, spat, commanded, and intoned. Really.

COVER ART

All the fabulous pulp magazine covers on this article series were created using the amazing Pulp-O-Mizer from art by its creator, Bradley W. Schenck.

Be sure to read the earlier Self-Editing for Everyone articles.

Part 1: The Most-Hated Writing Advice Ever

Part 2: Vampire Verbs, Zombie Verbs, and Verbs that Kick Ass

Part 3: Attack of the Adverbs!

Part 4: The Weakeners

Part 5: When Words Get in the Way

Part 6: Secrets of Relative Velocity

Part 7: Two Languages

Published on August 05, 2013 09:13

July 29, 2013

Self-Editing for Everyone Part 7: Two Languages

You are a veritable genius. Writers of English have extra linguistic resources, owing to that fact that English is two utterly distinct languages more or less happily married into one language of incredible richness. When a word from one branch won’t do, we can always go looking for one belonging to the other. The trick is to know which language to employ in which circumstances.

You are a veritable genius. Writers of English have extra linguistic resources, owing to that fact that English is two utterly distinct languages more or less happily married into one language of incredible richness. When a word from one branch won’t do, we can always go looking for one belonging to the other. The trick is to know which language to employ in which circumstances.Linguists everywhere consider English to be a Germanic language, but less than a third of today’s language actually derives from Anglo-Saxon roots, most of the rest having come to us from Latin, either directly from Roman influence or from Romantic languages such as French, a bit from Greek, even less from the Celtic language of the Britons who were running England when the Romans arrived. In a language race, the conquerors always win.

Conquest and language enrichment our speciality. English speakers borrowed (and did not return) Latinate language from four centuries of Roman rule, a passel of early Christian missionaries, and generations of Norman French rulers. More than 10,000 additional Latin words entered the language during the Renaissance alone. In fact, Latin words continued to enter English right up through the 18th century. Any time an Anglo-Saxon word wasn’t equal to describing a new concept or thing, someone constructed a new one from Latin.

Conquest and language enrichment our speciality. English speakers borrowed (and did not return) Latinate language from four centuries of Roman rule, a passel of early Christian missionaries, and generations of Norman French rulers. More than 10,000 additional Latin words entered the language during the Renaissance alone. In fact, Latin words continued to enter English right up through the 18th century. Any time an Anglo-Saxon word wasn’t equal to describing a new concept or thing, someone constructed a new one from Latin.So that’s how we got here. The question for our purposes seems to be “How does having a dual language affect us as writers?”

Thanks for asking.

English is hard work, and thirsty to boot. A Linguistic Discrepancy, or Weight Against Reach

English is hard work, and thirsty to boot. A Linguistic Discrepancy, or Weight Against ReachFor all that Anglo-Saxon doesn’t measure up in terms of actual numbers, most of the words it does provide are the most common in the language. Most everyday words for the common things and actions of everyday life are still based in English’s Germanic roots. One does not generally perambulate with one’s canine as often as one walks the dog. In a normal day, we are more likely to eat food than to consume or devour victuals, sustenance, or comestibles. Our language is two-thirds Latin, but our common usage is overwhelmingly rumpled old Anglo-Saxon, dressed in faded jeans and moccasins (no socks). When Latin comes out to play, it does so wearing its best clothes.

Okay, not THIS simple. Keep it Simple

Okay, not THIS simple. Keep it Simple For the purposes of ordinary, everyday fiction writing, and even most nonfiction writing, the plainest flavor of English is almost always the most unnoticeable and unnoticed, and writing that doesn’t call attention to itself for its own sake is writing that communicates its intentions clearly. When it’s time to make a reader see, hear, taste, smell, or feel something, the language needs to get out of its own way, and that happens when you keep it simple.

It’s usually better to say

Used than Utilized

Started than Initiated

Before than Prior to

So far than As of yet

But than However

Rest than Remainder

Found than Discovered

Happened than Occurred

Not all of those pairs involve Latinate English vs. Anglo-Saxon, but they do concern wordy and elaborate vs. clear and unadorned language. The more decorative word or phrase will be needed far more rarely and usually when you’re looking for a more formal style, deliberately distancing the reader from the narrative, or making your language sound educated, self-important, unemotional, or wordy. That’s what Latin-based English does best.

Latinate language puts the brakes on pace. Language and Pacing

Latinate language puts the brakes on pace. Language and PacingThe type of language you use helps to set the pace of your writing. Longer words, which are most often of Latin origin, help slow pace down by removing the reader from the immediacy afforded by more direct language. Shorter words, most often Anglo-Saxon derived, help speed it up. This is also true of dialog; when their feet are to the fire, characters tend to use the shortest, punchiest way to say anything. If you choose to have them do otherwise, do so deliberately and for good reasons.

Choose and Use

Speaking very generally, Latinate English is cool, erudite, perceived as higher in status and educational level, emotionally muted, and detached. Anglo-Saxon English is warm, down-to-earth, perceived as lower in status and educational level, and emotionally present. In real life, we tend to switch to Latinate English when we want to distance ourselves from the listener or establish higher status, and to shade over into Anglo-Saxon vocabulary when we’re going for closeness or establishing ourselves as "just one of the folks."

Most English speakers know unconsciously how to modulate their usage of Latin-based vs. Anglo-Saxon words depending on situation and context. We go back and forth between one and the other dozens of times every day, but most of us have never given the distinction a lot of conscious thought. Knowing about our two languages gives us a powerful tool for flexible and effective writing.

TL;DR

Rule of thumb: Anglo-Saxon English is informal, direct, close. Latinate words are the opposite.

Prefer use over utilize, start over initiate, happened over occurred, before over prior to.

Keep it simple except when you don't. And when you don’t, know why you didn’t.

COVER ART

All the fabulous pulp magazine covers on this article series were created using the amazingPulp-O-Mizer from art by its creator, Bradley W. Schenck.

Be sure to read the earlier Self-Editing for Everyone articles.

Part 1: The Most-Hated Writing Advice Ever

Part 2: Vampire Verbs, Zombie Verbs, and Verbs that Kick Ass

Part 3: Attack of the Adverbs!

Part 4: The Weakeners

Part 5: When Words Get in the Way

Part 6: Secrets of Relative Velocity

Published on July 29, 2013 08:23

July 22, 2013

Self-Editing for Everyone Part 6: Secrets of Relative Velocity

The one on the right is the gas. Pacing

The one on the right is the gas. PacingNo story is all action or all leisurely contemplation—or at least none worth reading. It’s vital to keep your story moving forward, but not relentlessly and not always at speed. Likewise, you must allow your characters to stop and think, but not to the point of putting your reader to sleep. A book that consisted of nothing but gunfights and car chases might be fast-paced but would soon become as boring to read as one where characters sipped tea and chatted about literature for 300 pages. People in fiction, like people in the real world, don’t always live life at the same speed, and readers need a break from both too much laid-back navel gazing and too much break-neck action.

There are two easy ways to check up on your pacing as you edit yourself.

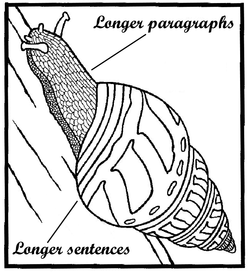

The Fiction Writer's Coloring Book, Fig. 17 Sentence Length

The Fiction Writer's Coloring Book, Fig. 17 Sentence LengthCount the words in a few dozen sentences from different parts of your work. Do they vary in length? Sentence length variety does at least two good things: it changes up the rhythm of your writing, and it helps control the pace.

Count the words in the sentences of an action or dialogue sequence, and do the same for a more leisurely part of your story. Which part had shorter sentences overall, and which longer? If there wasn’t much difference, you might need to work on tightening up the pace of your faster-moving scenes.

Long sentences tend to slow the pace of a story. There are times when you want to do this, particularly just before or just after a sequence of fast-paced action. In a slow-paced scene, sentences can lengthen out just a bit. Think of it like a heartbeat. When everything’s peaceful, the story’s heart rate can be slow and easy until the next action moment.

Thomas watched the gulls wheel in the gray sky above the gray water, always seeming to be on the lookout for whatever might be down there just below the surface. He threw the last of his stones into an incoming wave and walked back up the shore toward Lena’s place, more than half hoping no-one would be home yet.

Average length of a sentence: 29.5 words.

When the action picks up, so does the heartbeat. Pick up the pace of narrative with shorter, punchier sentences that contain less observation and reflection and more action and/or dialog.

Two figures resolved out of the mist. Thomas dropped behind a sandbar, heart hammering. It was Dexter and Clarke. Lena’s mother must have told them where he’d be.

Average length of a sentence: 7 words.

Dialogue is a form of action, and one that can move a story forward rapidly.

“Those two could have killed me. If they’d seen me, they would have.”

Mrs. Flores wrung her hands in the dish towel. “I didn’t tell them anything!”

“You’re the only one who could have!”

“No, Thomas, I never talked to them. I swear!”

“Leave her alone, Thomas,” Lena said. “She didn’t tell Dexter and Clarke where to find you.”

“Then who?”

“I did.”

Average length of a sentence: 5 words.

Let the length of your sentences help create the pace of your narrative and signal the reader how much forward movement to expect as soon as they see the page.

The Fiction Writer's Coloring Book, Fig. 18 Paragraph Length

The Fiction Writer's Coloring Book, Fig. 18 Paragraph LengthAlternating the length and action content of your paragraphs is a good way to slow down and speed up pacing. Long paragraphs slow the pace. This can be a good thing in moderation, but when a reader sees lots of lengthy paragraphs ahead, she may begin to skim. This is a slippery slope that might end with her putting down your book and forgetting to pick it up again.

Conversely, short paragraphs, including dialog, tell the reader that the pace is picking up, along with the information-to-words ratio.

When reading drags, break up long paragraphs into two or more. Use dialog and other short action paragraphs to slow down reading speed and perk up reader attention.

Part of the Matthew Scudder series. Masterful Pacing

Part of the Matthew Scudder series. Masterful PacingPace is also determined by content, so if your sentence and paragraph length matches the pace you’re hoping to set with your words, you won’t be working against yourself in that regard. It can be useful, however, to go against the reader’s expectations for pace. Let me give you an example of how a master does it.

Near the end of Everybody Dies, one of the Matt Scudder novels, Lawrence Block puts two well-loved characters in an unbearably tense situation. As they walk across the countryside into what they know is a trap to face an unknown number of well-armed men, the reader knows that one man is here out of loyalty to the other, who has foreseen his own death. In point of fact, both are far more likely to die violently and soon than to live past the next few minutes. Many authors would have made sure to speed up the pacing to keep the reader glued to the page, but Block has another way of snagging hearts and minds; he uses the time it takes them to walk to their fatal rendezvous to have one of the characters talk about life, his past, his philosophy, his beliefs. With every paragraph that delays the coming shoot-out, the reader is gripped by apprehension and anticipated grief. When the deadly shoot-out finally happens, it’s almost a relief to have the waiting over with.

Where Block could have sped the reader on to the final confrontation by upping the pace, he made the tension unbearable by slowing it. Where he could have written a perfectly fine chapter, he wrote a masterful one. Pace is but another of the little toys excellent writers like Lawrence Block use to keep readers buying and reading and anticipating books.

Chances are you'll fall naturally into keeping sentences and paragraphs at the proper length for the pace of your scenes, but if a scene isn't working, it may be worth reading to see whether or not the pace you need matches the pace you've written. I'll talk about how language choices affect pacing and other aspects of your writing in next week's article, "Two Languages."

TL;DR

Sentence and paragraph length directly affect story pacing. In general, they get shorter as the action speeds up, longer as it slows down.

Reading pace is to some degree the opposite. As pace picks up, reading rate slows down. As pace drops, reading speeds up.

Vary the length of paragraphs in slower-paced sections to keep readers’ eyes from glazing over.

COVER ART

All the fabulous pulp magazine covers on this article series were created using the amazing Pulp-O-Mizer from art by its creator, Bradley W. Schenck.

Be sure to read the earlier Self-Editing for Everyone articles.

Be sure to read the earlier Self-Editing for Everyone articles.Part 1: The Most-Hated Writing Advice Ever

Part 2: Vampire Verbs, Zombie Verbs, and Verbs that Kick Ass

Part 3: Attack of the Adverbs!

Part 4: The Weakeners

Part 4: The Weakeners

Part 5: When Words Get in the Way

Published on July 22, 2013 09:12