Richard Goodman's Blog

November 26, 2025

Thankful

I’m thankful for so many things. Especially now. Especially this Thanksgiving.

I’m thankful for my daughter. It’s a sublime gift to be the father of this brilliant, beautiful young woman.

I’m thankful for my good health.

I’m thankful for light; for the English language; for walking; travel; reading; Hemingway; museums; laughing; storms; for Paris; birds; learning, my body.

For gardening; the French language; poetry; outdoor showers; Maine; Flaubert’s letters; for the moon; The Great Gatsby; Southern food/soul food; my Smith-Corona Galaxie II manual typewriter; for cooking; my first apartment in New York on Tenth Street; music; M.F.K. Fisher; Giotto.

For van Gogh; French bookstores; the sound of rain; dogs; for New York City; driving down country roads; Isak Dinesen; fall, winter, spring, summer; the ocean; opera; the light in Provence; for writing; Deborah Attoinese; the struggle to make my book, French Dirt, the best book I could write.

For salt air; Ralph Ellison; a good baguette; my sister; snow falling down; road trips; for going to sleep when I’m exhausted; tea; kayaking; Van Morrison; the Frick Museum; for the Italian language; my bicycle; Michelin maps; François Truffaut; my daughter’s laugh; tall, slim pine trees; New Directions paperbacks; Tennessee Williams.

For old docks; books; going barefoot; etymology; James Baldwin; friendship; biscuits; work; identifying plants and trees; for New Orleans; porches; the songs of birds; Balzac.

For Cole Porter; West Fourth Street in New York City; libraries; the smell of hay; my wife’s gorgeous smile; for sweat; the Seine; Rome; my senses; the stillness of early morning; breasts; Pablo Neruda’s poetry.

For overcoming fear; for deep, pristine snow; water; wood, the smell and feel of it; herons and egrets; trains; a simple desk; for women’s rich, lavish hair; my brother; the rejuvenation sleep provides; Jean Rhys; coming home to someone you love; wetlands; Velázquez.

For a cast iron skillet; Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers; a good dictionary; lovemaking; Big Joe Turner; Evelyn Waugh; for the Cevennes; rock ‘n’ roll; full lips; seeing my daughter born, holding her for the first time; for Joseph Conrad; Marcel Pagnol; Manon, our dog; my memory; pecan pie; for Ms. Booth, Ms. Benson, Ms. Shugrue and Ms. Carley, all the teachers who were so kind to my young daughter.

For Langston Hughes; Greenwich Village; Verdi; warblers; kindness; pastrami; bookstores; belly laughs; for breathing; Lucinda Williams; the smell of suntan lotion at the beach; dusk; strong coffee; Ray Charles; for brilliant sunsets; Elizabeth Bishop; Central Park; Wellfleet oysters; stretching; friends’ voices; affection; holding hands with the woman I love; the release of crying; John Lennon; truth.

And, especially, this Thanksgiving, for my wife, for Gaywynn.

November 13, 2025

My own private Dante

This is a post for book lovers. Fanatics might be a better word. Be forewarned.

Some years ago, I went to Rome to teach for two weeks in June. I came a few days early to acclimate myself and, in the airport, ran into a fellow teacher in the same summer program. We decided to walk around Rome together. We went to the Piazza Navona and then wandered into the nearby Church of Sant’Agostino. Inside, to our left, was a large painting titled “Madonna dei Pellegrini” by Caravaggio. Immediately, the thought came to my mind,

“I wonder where the original is?”

I was just a few hours off the plane, remember.

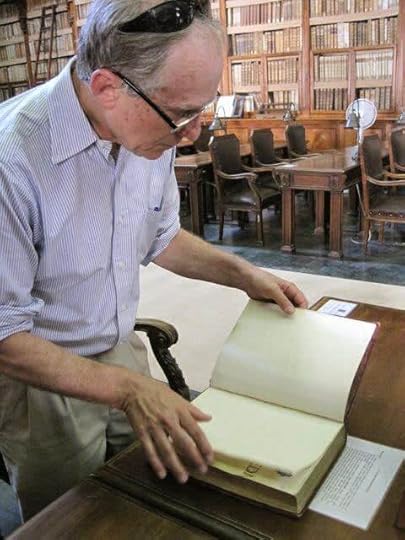

We walked outside. Next door was the Biblioteca Angelica. A library. It looked fairly plain from the outside. I suggested we go inside. (Background: I was supposed to give a lecture on Dante as part of my teaching responsibilities.) I spoke some rudimentary Italian, a hodgepodge of opera arias and a few courses here and there. There was a man at a desk in an anteroom. I asked him if we could go inside the library. He said yes, just fill out this card. I guess that’s standard around the world. We did, and we stepped inside to this:

It was a book-lover’s dream. It was like an all-you-can-eat literary feast. Those books! Row after row. Ancient, leather-bound books, reaching up to the sky. Doesn’t it make your mouth water?

It did mine. I had to ask my colleague for a Kleenex because water was cascading down the corners of my mouth onto the floor. I looked like a dog when you don’t give it the treat right away.

After cleaning myself up, I walked up to the main desk behind which three women were seated. I asked them in my pig-Italian if they had any copies of The Divine Comedy. All three of them smiled at once. “Sì,” they answered in unison. I asked them if they had some very old editions. More smiles. “Sì.” Could I see the oldest edition? (Refresher: Dante wrote The Divine Comedy between 1308 and 1321. Gutenberg printed his first Bible in 1455.) “Sì,” they said, again.

I learned later that the Biblioteca Angelica is the oldest public library in Europe. I suppose that’s why I could simply ask for a book—and get it.

In a few minutes, one of the women returned with a volume. She simply handed it to me. “I can look at it?” I asked. She nodded. Didn’t have to wear white gloves? No, I did not. So, I just took it to a table nearby. And opened it. My colleague snapped a photo.

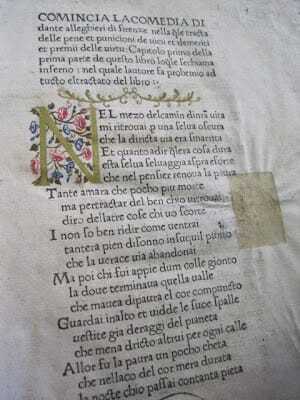

I didn’t know precisely what I was looking at until later. I could see that this edition of The Divine Comedy had been printed in 1472 in a town called Foligno by a man named Johann Neumeister. The name didn’t have that Italian ring I was expecting. I reasoned he must be German (I have several Master’s degrees) and that he had worked with Gutenberg (possibly). What I didn’t know was that this was the first printed edition of The Divine Comedy, anywhere.

I opened the book.

Well, Lord have mercy. Let’s get in a bit closer:

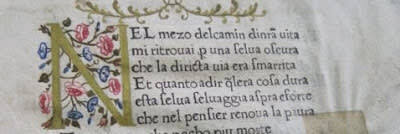

There are those famous Italian words, the most famous Italian words ever written, here put down in a kind of medieval shorthand, with the “s’s” shaped like “f’s,” “Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita / mi ritrovai per una selva oscura / ché la diritta via era smarrita.” As translated by Robert Pinsky, “Midway on our life’s journey, I found myself / In dark woods, the right road lost.” There may be equally good openings, but can you show me a better one?

I suddenly felt the lecture I would give had been distantly blessed by the poet himself. It was as if he were speaking to me across the centuries.

Dante

DanteI wondered who had read this particular copy of the book when it was printed over five centuries ago. I still couldn’t believe the three librarians were letting me page through this book freely. I was respectful, mind you, and careful, but still. I read on:

“Ahi quanto a dir qual era è cosa dura / esta selva selvaggia e aspra e forte / che nel pensier rinova la paura.” Again, Pinsky, “To tell / About those woods is hard—so tangled and rough / And savage that thinking of it now, I feel the old fear stirring.” Then he begins his own remarkable journey.

I stood there and drank my fill of Dante. Satiated and stunned, I gave the book back to le tre donne gentili, and we left. We walked back out onto the street. The sun was full, glorious.

This was my first day in Rome.

November 6, 2025

A very considerable speck

I get up at 5AM. After making coffee, I go to the room in back where I write. I sit down, turn on the computer and usually stare at the blank screen. It stares back. “Well,” it seems to say, “looks like you have nothing to say. Again.” Very dispiriting.

So I sit there. Staring at the screen. The computer screen is going to win this staring contest, though. It always does. “Still got nothing?” it seems to say. “Have you thought of a career in sanitation?” I look away, start to daydream and come up with all the things that need to be done instead of trying to write.

This morning I’m joined by a tiny flying insect. It’s so small I have to look twice to believe it’s there. It lands on my blazing empty screen. It ambles up and then down. It’s light brown, with wings nearly as long as its body. I have no idea what it is. It moves along rapidly and then flies off for a bit. Then it returns to the screen, which, applying moth-logic here, it’s probably drawn to by the screen’s brightness.

Whatever is motivating it, it’s got things to do. It’s busy. It seems to have a purpose. More than I do, that’s for certain. Wait—I’m envious of an insect? Apparently.

Speck, bottom, on the move.

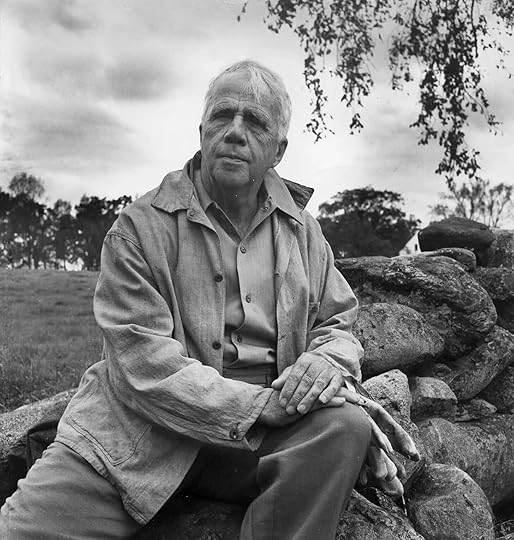

Speck, bottom, on the move.Robert Frost wrote a poem, which I allude to in this post’s title, “A Considerable Speck,” about a similar incident with an insect. I was too lazy to come up with my own title, so I stole his. I’d like you to note, though, that I added the word, “very,” for originality. It’s quite different.

In the poem, Robert Frost is writing away when he sees what, at first, he thinks is a speck of dust on his white page. It turns out to be an extremely small insect. (His poem has a parenthetical subtitle, “Microscopic”.) He observes the creature moving across the page, watches it make what he concludes are decisions: “Plainly with an intelligence I dealt,” he writes. He decides, “Since it was nothing I knew evil of,” to let it alone.

Robert Frost, speck observer

Robert Frost, speck observerFrost ends the poem in a droll way, taking us far beyond the speck’s movement across his page. Drollness is often a Frost trademark. I’ve always thought this ending is a sly way of Frost responding to his critics. In any case, it’s a deft way of taking something ordinary and turning it into a kind of wily commentary: “I have a mind myself and recognize / Mind when I meet with it in any guise / No one can know how glad I am to find / On any sheet the least display of mind.”

Like Frost, I have no desire to kill this tiny creature that moves, with focus and determination, up and down my screen. What would be the point? Because it slightly distracts me from my writing? What writing?

Besides, today, so far at least, the only mind working on this computer screen is not my own.

October 30, 2025

In the realm of Sulphur

Last night, I slept in Sulphur. That is, Sulphur, Louisiana, a city just west of Lake Charles, in southwest Louisiana.

Yes, there is actually a city named Sulphur. I stayed there last night because I was attending a meeting of the Louisiana Ornithological Society. It took place in the town of Hackberry, about thirty minutes south of Sulphur, but there were no rooms to be had in Hackberry. The closest available rooms were in Sulphur. So, there I stayed.

I wanted to find out how the city got its acrid name. I discovered that, indeed, there used to be sulphur mines in the area in the early 1900s. The Union Sulphur Company was founded to extract the sulphur from deep below the earth. And that’s how the city got its name. (I use the British spelling here, “sulphur,” to match the spelling of the city’s name.)

I imagine the Sulphur Tourist Bureau, if there is one, has a challenging job. What would they say, or show, to draw people to their city? What would their slogan be?

“You know the element! Now try the town!”

Staying in Sulphur here got me to thinking about sulphur itself.

What, exactly, is sulphur? Wikipedia says, “Sulphur is the tenth most abundant element by mass in the universe and the fifth most common on Earth. Though sometimes found in pure, native form, sulphur on Earth usually occurs as sulfide and sulfate minerals. Being abundant in native form, sulphur was known in ancient times, being mentioned for its uses in ancient India, Greece, China and Egypt.”

I found out that sulphur in the Bible and elsewhere is also called brimstone, as in “fire and brimstone.” That phrase is usually connected to divine retribution or Hell. The word sulphur derives from a word that means “to burn.” Brimstone means “burning stone.” The two words are used interchangeably in the Bible and elsewhere.

Sulphur and sulphureous flames have always evoked terror and pain. If you’re a grave sinner or are considering committing a particularly egregious sin, the thought of spending the rest of eternity having sulphurous flames rain down on you might give you pause.

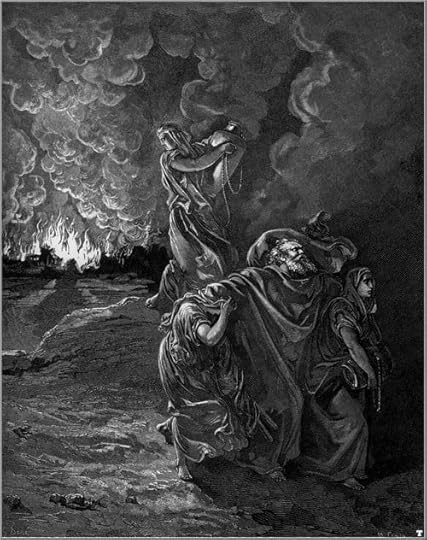

Think the kind of Hell Milton describes in Paradise Lost, where you are exposed to “ever-burning Sulphur unconsum’d.” Let’s not forget the Bible: “Then the Lord rained down burning sulphur on Sodom and Gomorrah” (Genesis 19:24).

Lot fleeing sulphurous flames

Lot fleeing sulphurous flamesThis got me to questions we all grapple with sooner or later. Does Heaven exist? Does Hell exist? The people who believe they do, and the people who believe they don’t, seem to be equally certain of themselves and equally adamant.

I’ve actually been thinking a lot about Hell lately. Because of the life I’ve led. I wonder if I’ll be judged not to have lived a virtuous life, that I have caused more harm than good. Will I be sent to Hell? The fact is, dear reader, none of you can tell me with any certainty that this will not happen—however adamant you are.

And, yes, I worry. Quite a lot. Especially since I’m 80, and the day of reckoning is if not nigh then within walking distance. Sometimes, I shiver in fear. I do. Have I done enough with my one wild and precious life, as the poet says? And, as the prayer asks, have I done those things I ought to have done and have I done those things which I ought not to have done?

Maybe the town’s slogan should be, “Sulphur. The town that makes you think.”

Meanwhile, I’m leaving Sulphur, and I’m heading home.

Heaven, or hell, can wait.

October 21, 2025

Janet Shea

I’m writing this in Boston. That seems so appropriate, because Janet was born and raised here. She died October 12. She was 90. She was lovely.

I got to know Janet Shea in Louisville, at Spalding University’s MFA in Writing program, in 2005. I was teaching creative nonfiction at Spalding, and I had her in a workshop I led. In fact, I had her in several workshops, and so got to know her and her writing well.

I can see her now, seated with the other students around the table in one of Spalding’s conference rooms, eager and shy, fulfilling a dream at 70 years old. Because that’s what she was doing, fulfilling a dream to write that she had to put on hold while she raised her five children. She was of a generation before the women’s movement. Women having a career was not what normally happened or was encouraged. But here she was now, doing it.

She wrote about her Irish Catholic childhood in Boston, and what richer material is there than a solid Boston Irish Catholic childhood? I was entranced by her writing, and so were her fellow students. She wrote lyrically and feelingly about her family and about her growing up.

This is from her essay, “Elegy to Jimsey,” about her younger brother. The excerpt was read at her graduation in Louisville:

“On the way home, Jimsey holds the big bouquet close up to his face, nuzzling its cinnamon fragrance. He walks straight and tall beside me, his honey-colored hair blown back off his face, his violet eyes trimmed in mink lashes, a pink birthmark on his forehead, the size of a miraculous medal. He is so beautiful. He smiles at me, the same smile on his lips today while I visit. The same smile he wore when I took him to the movies on a Saturday afternoon when he was six and I was fourteen. We saw Bing Crosby and Bob Hope On the Road to somewhere. Bing, getting ready to board the plane that will take them to Rio, gives a huge, arcing Mr. America wave from the screen. My brother waves back. For years afterwards whenever we got together, we’d greet each other with that Mr. America, Queen Mother, Beauty Pageant Wave—as if it were a magic wand, slicing through the stratosphere of time and place.”

This is what she had inside her, all those years, waiting to emerge. It was a glory to watch her reveal her writing to the group of writers around the table and to see the modest pride on her face when they responded with pleasure and praise after she read.

Janet Shea

Janet SheaShe lived in Maine in Tenants Harbor on the coast. Coincidentally, I taught in Maine in the summers, and so I visited her several times at her home where she and her husband, John, lived. He was very ill then, and most of her time was spent caring for him. It took its toll. But she was always glad to see me, and I, her.

In 2016, she published a book of poems, Prayers of a Roadside Contemplative. I remember on one of my visits to Tenants Harbor being in her study where she wrote as she read me a few of these poems. It was one of those perfect Maine summer days, bright and sweet-smelling, the air traced with the sea’s presence. Janet was anxious. Were they any good? I thought so. She read them to me in that lilting, honeyed voice of hers. She was born to recite poetry. This is the first poem in the collection:

A year or so later, her husband, John, died. She moved from her home in Tenants Harbor to an apartment in Portland, in one of those assisted living places. (Later, she moved in with her daughter, Alice, in whose home she was blissfully content.) On the way to my teaching job in Maine, I visited her in Portland. I hadn’t seen her since John died. I wrote these lines that follow soon after that visit, so that’s why I know the words she speaks are accurate.

I knocked on the door. It opened, and there she was, with that lovely Boston-Irish face, that smile as big and open as Faneuil Hall. There are some greetings that make you feel ten years younger, and Janet’s is one of them. I walked into a charming apartment. It had cascades of light and intimate touches everywhere.

Janet

JanetWhen I had last visited her in Tenants Harbor, she was trying to bear up under the weight of caring for a very sick husband. Now, here in Portland, she was free from that, and though she was sad about John’s death, she also felt grateful “for the solitude he bequeathed me.” She speaks like this, with the dramatic intimacy of an Irish storyteller. Janet has the most delicious voice, at turns conspiratorial, at turns astonished, at turns instructive. It’s not exactly husky, but it has a cabernet richness to it, and if you heard it on the radio, you wouldn’t want to move the dial. She has a wonderful—I can’t escape that word when talking about her—laugh and smile. Her hair, silver gray, is cut very short.

I sat down. She began telling me what she’d been doing. We talked about many things as we sat there at her table, eating a lunch she prepared—chicken pot pie and fresh tomatoes with basil and olive oil.

She’s 84, and this is how I want to be 84.

Then the talk turned to the place she was living, and the people who live here. I asked her if the place served food.

“Yes. I went a few times, but I didn’t like it. Awful. So, I make my own food. What’s the big deal? You cook. I don’t mind. I did mind when I used to have to make three meals a day all year, but now it’s just me.”

I asked her about living here.

“So many of the people here are…just old,” she said. She looked me straight in the eye. “I just want a decent conversation, about interesting things.”

I asked her if she believed in God.

“No. I believe in something, in an energy that comes from all of us,” she said.

“Life is a mystery,” I said. “I mean, what is it that makes us alive? What is it that’s life and, when it’s gone, is death?”

“Death is with us all the time,” she said. “We live with death.”

“You were raised strictly Catholic, right?” I asked.

“Oh, yes. I was fodder for the convent when I was a girl. I used to believe, but it was those priests and the things they did that soured me. I’m done with that.”

Janet and me.

Janet and me.Then I remembered one of the funniest things Janet had ever written for Spalding and done. She had five children, and at times it was overwhelming. It was hard to cope, and who would be able to, day after day, without help? So she would play this game she called “Coffin Mommy,” where she’d pretend she was dead, and none of her five children were allowed to disturb her, because she was dead. She’d lie on the floor absolutely still, arms over her chest, eyes closed. This was how she got a precious few minutes of peace.

We talked about writing and books, and she mentioned Patricia Hampl, whose latest book she was reading. She read me a few passages from the Hampl book. How lovely it was to be read to on a cool June afternoon in Maine in a warm room, the words being read by someone I so liked and admired. I realized I would rather be talking to Janet at that very moment than with anyone, young or old.

I got up to leave. Janet had a movie date with two other women from the building at 2PM. They were going to see The Book Club.

“These four women have all read Fifty Shades of Gray and they meet to discuss that.” She rolled her eyes. “I tried to get out of it. I did once, but they got me the second time.”

She walked me to the door.

“Come visit me,” I said. I was going to spend the whole summer in Maine teaching.

“I’d love to. And let me know what’s happening with you.”

That big smile. Then goodbye.

Goodbye, Janet.

October 16, 2025

The Hermit of Croisset: Flaubert’s Fiercely Enduring Perfectionism

It could be said that the modern novel, or at least the sensibility of the modern novelist, was born when Gustave Flaubert went to live with his mother.

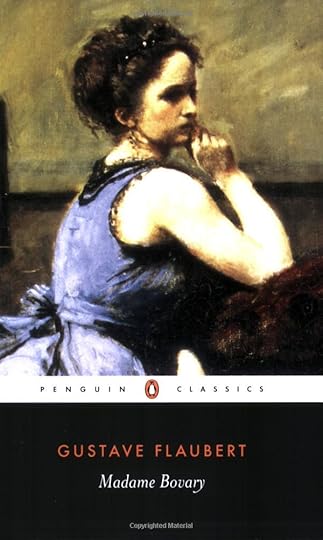

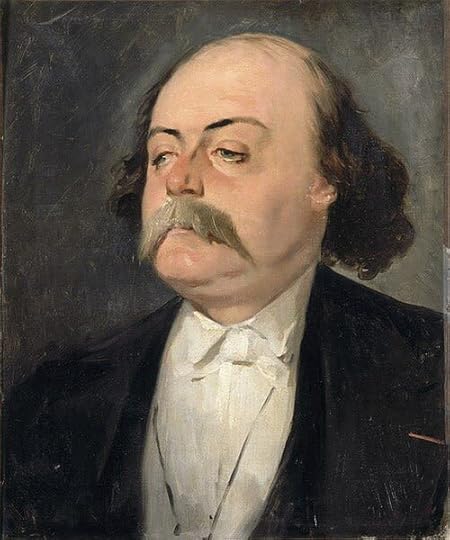

Big biographies—including a massive five-volume tome by Jean Paul Sartre and a 620-page book by Frederick Brown—have been written about a man who, save for a few interludes, lived his entire life in the same house in the same small village in Normandy. For years, Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880) lived with his mother, and, when she died in 1872, he stayed on alone in this village of Croisset. He made his study in a room on the second floor of this three-story house. There he wrote Madame Bovary, the book that, in his lifetime, would make him infamous and, after his death, immortal.

Toiling day in and out—or, really, night in and out, since he preferred to work late into the night—he slaved for his art. This relentless and agonizing search for le mot juste, the exact word, has made him the icon for the pursuit of literary perfection in the eyes of writers ever after. Writers from Henry James (“...he is for many of our tribe at large the novelist....”) to Hemingway (“He is our most respected, honored master”) to those of the present day like Mario Vargas Llosa (after reading Madame Bovary he wrote, “I now knew what writer I would have liked to be”) to Julian Barnes (who, after a pilgrimage to Croisset, wrote Flaubert’s Parrot) to scores of others, including the contemporary essayist Sven Birkerts, who, as a young writer, had been “deeply influenced by stories of Flaubert’s grail-quest for le mot juste”—all have turned to Flaubert for inspiration.

This legacy of inspiration lives on and no doubt will continue to live on. We can, as writers, still count on Flaubert to urge us onward, to show us that what we’re doing is worth the blood, sweat, and tears. Once, when Oscar Wilde was asked what he had done that day, he said, “I was working on the proof of one of my poems all the morning, and took out a comma. In the afternoon I put it back again.” We may or may not believe Oscar, because he was his own most precious work of art, and he was forever shaping it for public view. (By the way, Wilde once declared that “Flaubert is my master.”) But when Flaubert writes a friend that he spent three days making two corrections and five days—normally twelve-hour days—writing one page, we believe him.

In Flaubert we have, perhaps for the first time, a writer who brought into the center ring of the three-ring circus of writing—and with a bright spotlight at that—the idea that we should search for the exact word, the most beautiful sentence, the most realistic scene, as if our life depended on it. He had a fierce confidence that what we do as writers matters and that it is worth a lifetime of sacrifice and pain. The proof is all there in the writing.

He never married. He had no children. He had no profession outside his writing. In his youth, he studied law, but, just before graduating from law school, had a kind of nervous breakdown. He did not return to law. He just wrote. He was eventually dubbed “the Hermit of Croisset.” There, in his house, he lived like a monk. As Timothy Unwin writes in the Cambridge Companion to Flaubert:

“...up and down the avenue of lime trees in his garden, sometimes in the company of his friend and mentor Louis Bouilhet, Flaubert bellows out the sentences of Madame Bovary to the amazement or amusement of the folk in passing river craft. This is the legendary gueuloir, or ‘yelling place,’ where the novelist puts his writing through the test of sound, rhythm and vocal fluidity, subjecting it to the final quality control.”

This is a man gripped by the throat by writing, a death grip that he cannot free himself of.

It is through Henry James that we have one of the clearest and most appealing portraits of Flaubert. Gustave Flaubert was a large man, six feet tall, with a booming voice, flowing blonde hair—he seems like a character out of Asterix—and a dragoon-like drooping mustache. In addition to the house in Croisset, he kept a small apartment on the Right Bank of Paris. From time to time he would emerge from his isolation in Normandy and stay for a month or two in Paris so as to see his friends and to expose himself to humanity. When his mother was still alive, he brought her too and set her up in a place nearby. There, in his sixth floor walk-up, on Sunday afternoons, he would hold forth, and his artistic friends would flock to see him. On any given Sunday you might find Turgenev, the brothers Goncourt, his old friend Maxime du Camp, the critic Sainte-Beuve, and the young Zola. And, on a few occasions, Henry James. Remember that James knew French intimately. In an essay written after Flaubert’s death, James remembered:

“He had... a small perch, far aloft, at the distant, the then almost suburban, end of the Faubourg Saint-Honoré, where on Sunday afternoons, at the very top of an endless flight of stairs, were to be encountered in a cloud of conversation and smoke most of the novelists of the general Balzac tradition....There was little else but the talk, which had extreme intensity and variety; almost nothing, as I remember, but a painted and gilded idol, of considerable size.... Flaubert was huge and diffident, but florid too and resonant, and my main remembrance is of a conception of courtesy in him, an accessibility to the human relation....”

Flaubert never stayed in Paris too long. He always returned to Croisset, to his smoke-filled study, and, in later years, his trips to Paris became less and less frequent. He did indeed become the hermit of Croisset, a monk, and eventually became completely celibate, like a monk—though Julian Barnes has pointed out that he may not have been so celibate on those infrequent trips to Paris. As a young man, especially in his travels to the Middle East, he had left no stone unturned sexually. No more. In 1878, in a letter to Guy de Maupassant—who was the nephew of an old friend—he wrote, “You complain about fucking being ‘monotonous.’ There’s a very simple remedy: stop doing it.... You must—do you hear me, young man?—you must work more than you do.... You were born to write poetry: write it! All the rest is futile.”

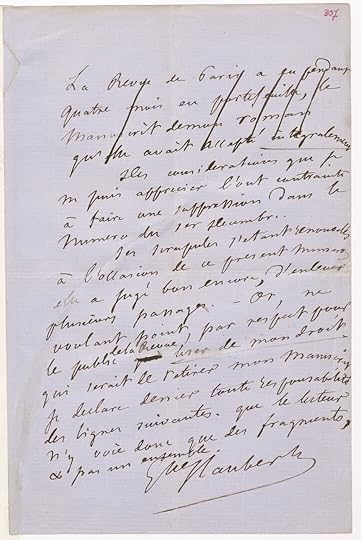

Flaubert was thoroughly modern in that, like James Joyce who followed him, and William Burroughs even later, he—or, really, Madame Bovary—was put on trial for obscenity. It is difficult to imagine a book as mildly sexual—in which there are no four-letter words and no explicit sexual consummation—would cause the public prosecutor to demand its destruction. For a man as private and ultimately misanthropic as Flaubert, this was a terrible thing, a trying thing, to be forced into the public eye as blatantly as he was. Madame Bovary began its life in the Revue de Paris in 1856, to be serialized in six parts. Almost immediately it attracted the government’s eyes and, eventually, the government struck: Flaubert and the owners of the Revue were put on trial for “outrage of public morals and religion.” Adultery and suicide, however elegantly portrayed, were just too much for Napoleon III’s regime. Ultimately, Flaubert won his case. But it only enhanced his desire to rid himself of the world at large. He wrote a friend, “...all this has left me so exhausted physically and mentally that I haven’t the strength to walk a step or hold a pen.... I long to return, and forever, to the solitude and silence I emerged from; to publish nothing; never to be talked of again.”

So, wary of humanity, he went back to Croisset. He did write, of course, and he did publish again.

It doesn’t matter to us that Flaubert wrote in French, and not English, because the pursuit of the exact word—and all other forms of artistic excellence he strove for—knows no linguistic barrier. We may not know enough French to read Madame Bovary or Sentimental Education in the original and pass judgment on whether or not we believe Flaubert achieved his lofty goal, but no matter; the philosophy is fully translatable. The question is: how do we know about Flaubert’s relentless work habits, about his tortured search for perfection?

And it was tortured: Henry James wrote that Flaubert “felt of his vocation almost nothing but the difficulty.” (This is not entirely true, as we shall see.) How do we know that he spent three days making two corrections? How do we know that after he composed the suicide scene in Madame Bovary where Emma Bovary swallows arsenic, there was such a strong, imagined taste of arsenic in his own mouth that he actually vomited? He did everything to avoid being what we would call a celebrity. According to Julian Barnes, Flaubert “allowed no photograph of him to be published in his lifetime.” (Photographs do exist, so we must put the emphasis on “published.”) He gave no interviews that I know of. He hated the press. (“The press is a school that serves to turn men into brutes, because it relieves them from thinking.”) He was an intensely private man.

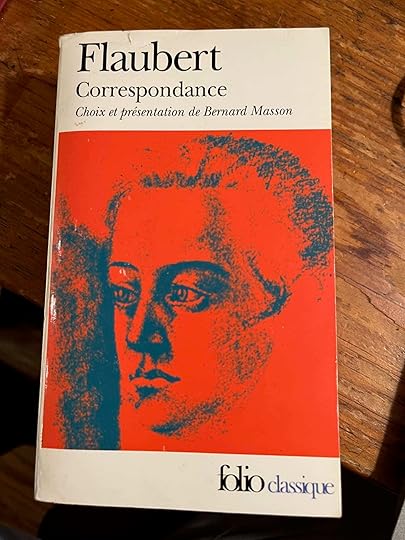

We know because of his letters. Now, nearly 130 years after his death, almost all of them have been published, and many of them translated into English, as well as into other languages. The fact is, though, quite a few of his letters came into the public view amazingly early. In 1884, just four years after his death, Flaubert’s correspondence with George Sand, the great friend of his later years, was published with an introduction by Guy de Maupassant. From 1887 to 1893, his niece, Caroline, with whom he had a complex, sometimes troubled relationship, published four volumes of his letters. Henry James reviewed the last volume for Macmillan’s Magazine. In 1895, the first English translation of a selection of his correspondence was published. Since then, various editions of his letters have been published, including, from 1926-1933, a nine-volume edition—right on up to the splendid two-volume English translation by Francis Steegmuller (1980-82) referred to earlier, and to, finally, the Pléiade edition, edited by Jean Bruneau and completed, upon his death, by Yvan Leclerc and other scholars. We can be certain there will be more editions.

It is in these letters that we see Flaubert unplugged. They reveal him as his novels never will. He was the man who said that “an author in his book must be like God in the universe, present everywhere and visible nowhere.” Anyone reading Madame Bovary would, I think, be surprised to find the kind of man its creator is within the pages of his letters. He is as stormy and wild as his great novel is calm and collected. His letters make for great reading, and it is here we find the Flaubert that writers have come to put on their pedestals. (We also see him with his hair down in the journals of Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, and there are indeed some wonderful moments in those pages, but there is nothing as direct and forceful as what we get by reading the letters.)

I’m certain Flaubert would have been appalled, horrified, and fiercely angry at this public display of his private thoughts and communications. “May I be skinned alive,” he wrote, “before I turn my private feelings to literary account.” He was a preternaturally private man who, for example, hated surprises, hated an unexpected, unannounced guest.

With his close friends, he could be extremely warm, generous, and even ridiculous. He became friends with George Sand after the publication of Madame Bovary and visited her on several occasions at her house in Nohant. During one such visit, Sand wrote in her diary, “Lunch at noon. Lolo dances all her dances. Flaubert puts on woman’s clothes and dances the cachucha with Plauchet. It’s grotesque—we all behave like lunatics.”

But this is the private Flaubert, and even now I feel his shade moving uneasily at my revelation. Henry James called the publication of his letters by his niece a “posthumous betrayal.” In this desire for privacy, Flaubert was like W.H. Auden, who commanded his friends to destroy all his letters.

It seems, though, that very few of Flaubert’s letters to his correspondents were destroyed. As Julian Barnes wrote in a review of Flaubert’s letters, alarmed “by the posthumous publication of two series of (the writer Prosper) Mérimée’s love letters, he had a letter-burning pact in 1877 with Maxime Du Camp, which wiped out ‘our life between 1843 and 1857.’ Two years later, in an eight-hour session with his protégé, Maupassant, a lifetime’s incoming correspondence was assessed, ordered, packeted, and in some cases—certainly that of (Flaubert’s mistress) Louise Colet...burnt.” This was the exception, however, not the rule. Louise Colet kept Flaubert’s letters to her—as did many others. When we read the Steegmuller translations, we see that Du Camp and—obviously from the letter cited earlier—even Maupassant did not throw all of Flaubert’s letters away.

Restless shade or not, the letters are there for us to read. I, for one, despite a slight sense of voyeuristic guilt, say, good. They are endlessly inspiring and uplifting. Flaubert writes about many things to his correspondents, but he is always obsessed and doomed by writing, by art. As Henry James wrote in an introduction to an English edition of Madame Bovary, Flaubert “was born a novelist, grew up, lived, died a novelist, breathing, feeling, thinking, speaking, performing every operation of life, only as that votary.”

These letters, demonstrating his unstinting dedication to his art, can bolster the frustrated and agonized artist. It is a fierce dedication. “When one does something,” Flaubert wrote to his mother from the Middle East, “one must do it wholly and well. Those bastard existences where you sell suet all day and write poetry at night are made for mediocre minds—like those horses equally good for saddle and carriage—the worst kind, that can neither jump a ditch nor pull a plow.”

He wrote many of his most inspiring letters about art to Louise Colet during the time he was writing Madame Bovary. Colet, herself a published poet, was Flaubert’s mistress for a number of years until he cut her out of his life like a dead rose, with a sure swift snap. As far as I know, she never visited him at Croisset. (Well, yes, once-unannounced, but Flaubert was not at home.) They usually had their infrequent rendezvous in Paris or elsewhere. While they were together—which is somewhat of a misnomer, since he saw her irregularly and he never lived with her—he wrote her long letters filled with passion about his feelings for her and his feelings for art. He met her in 1846, when he was twenty-five. She stayed in his life through most of the composition of Madame Bovary until, in a curt note written in March of 1855, he dismissed her forever. It is because of these letters that we know so much about Flaubert’s composition of Madame Bovary.

He began writing Madame Bovary in September 1851 and finished it five grueling years later in April 1856. He wrote to Colet the day after beginning, “Last night I began my novel. Now I foresee difficulties of style, and they terrify me.” A month later, he is already in pain: “I suffer from stylistic abscesses; and sentences keep itching without coming to a head. I am fretting, scratching.” Yet, onward he plowed. A month later he to wrote Colet, “I am advancing painfully with my book. I spoil a considerable quantity of paper. So many deletions! Sentences are very slow in coming.”

In January of 1852, he proclaimed to her perhaps the core of his literary belief, “...there are no noble subjects or ignoble subjects; from the standpoint of pure Art one might almost establish the axiom that there is no such thing as subject—style in itself being an absolute manner of seeing things.” This would result in his ideal book—”What seems beautiful to me, what I should like to write, is a book about nothing, a book dependent on nothing external, which would be held together by the internal strength of its style.”

Flaubert soon realized his book would take him years to write. “There is nothing at once so frightening and so consoling as having a long task ahead,” he wrote to Colet in March of 1852. In April, he wrote to her about the “pleasures” of writing—”I love my work with a love that is frantic and perverted, as an ascetic loves the hair shirt that scratches his belly.” In the same letter he summed up for anyone who has ever put pen to paper the bizarre, manic-depressive state writers often find themselves in:

Sometimes, when I am empty, when words won’t come, when I find I haven’t written a single sentence after scribbling whole pages, I collapse on my couch and lie there dazed, bogged in a swamp of despair, hating myself and blaming myself for this demented pride that makes me pant after a chimera. A quarter of an hour later, everything has changed; my heart is pounding with joy. Last Wednesday I had to get up and fetch my handkerchief; tears were streaming down my face. I had been moved by my own writing: the emotion I had conceived, the phrase that rendered it, and the satisfaction of having found the phrase-all were causing me the most exquisite pleasure.

However, he was soon back to talking to Colet about the difficulties of writing. “What a bitch of a thing prose is!” he wrote to her in July of 1852. “It is never finished; there is always something to be done over.” Later that month he wrote, “Writing this book I am like a man playing the piano with lead balls attached to his knuckles.”

Always his goal was to be absent from his book, “‘How is all that done?’ one must ask; and one must feel overwhelmed without knowing why.” In a December 1852 letter to Colet, he sarcastically wrote what must be music to the ears of any writer who has tried to do something new, “I would show that in literature, mediocrity, being within the reach of everyone, is alone legitimate, and that consequently every kind of originality must be denounced as dangerous, ridiculous, etc.” How does one go forward against the tide of mediocrity? “One must sing with one’s own voice,” he wrote Colet in January 1853.

In June 1853, he wrote to Colet about the difficulty of the mundane in writing: “It is so easy to chatter about the Beautiful. But it takes more genius to say, in proper style: ‘close the door,’ or ‘he wanted to sleep.’” Then, in the same letter, he vented about critics, and what author who has been scorched by someone in print can’t take solace from this: “Criticism occupies the lowest place in the literary hierarchy: as regards form, almost always; and as regards ‘moral value,’ incontestable. It comes after rhyming games and acrostics, which at least require a certain inventiveness.”

And, no, it isn’t all pain, this writing of Madame Bovary. In December of 1853 he wrote to Colet, “...it is a delicious thing to write, to be no longer yourself but to move in an entire universe of your own creating.” Then there is a marvelous gem from one of his last letters to Colet before he tosses her aside: “Sentences must stir in a book like leaves in a forest, each distinct from each despite their resemblance.”

Then the letters to Louise Colet, increasingly more passionate about art than about love, stop.

After Louise Colet’s summary dismissal in 1855, Flaubert would live for another twenty-five years. He would finish Madame Bovary and then write five more books: Salammbô; Sentimental Education; The Temptation of Saint Anthony; Three Tales; and the unfinished Bouvard and Pécuchet. He continued to write letters, many of them to George Sand, but also to Ivan Turgenev, Alphonse Daudet, Guy de Maupassant, Émile Zola, and, frequently, to his niece, Caroline. All of them are inspiring in some way or another to the writer working away alone, often distressed, sometime elated, many times lost and bewildered.

The letters bristle with frustration and with perseverance. In April of 1880, in one of his last letters, written to his niece, Caroline, he wrote, “...will I have reached the point I’d like to attain before leaving my dear old Croisset? I doubt it. And when will the book [Bouvard and Pécuchet] be finished? That’s the question. If it is to appear next winter, I haven’t a minute to lose between now and then. But there are moments when I feel like I’m liquefying like an old Camembert, I’m so tired.”

Less than a month later he was dead. But if we open his letters, he springs back to life, the irascible, impassioned, relentless perfectionist, still slaving away for his art, still agonizing over every word, every phrase-still searching, like the pearl fisher he compared himself to, for le mot juste. With that in mind, I’ll leave the last word to Flaubert himself,

“What an atrociously delicious thing we are bound to say writing is—since we keep slaving this way, enduring such tortures and not wanting things otherwise.”

NOTE: I have not put numbered footnotes in the text to make for smoother reading. The references are below. For the most part, it’s clear what they refer to. I can supply you with a version with in-text citations, if you like. Just send me a note.

This essay, first published in “The Writer’s Chronicle,” is used a a reference (number 36) in the Wikipedia entry, “Flaubert’s letters.”

Jean-Paul Sartre, The Family Idiot: Gustave Flaubert, 1821-1857 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981-1993.) Originally published as L’Idiot de la famille, 3v. (Paris: Gallimard, 1971-72).

Frederick Brown, Flaubert: A Biography (New York: Little, Brown, 2006).

Henry James, Literary Criticism: Volume Two (New York: Library of America, 1984), 316.

Ernest Hemingway, Selected Letters, Carlos Baker, ed. (New York: Scribner’s, 1981), 624.

Mario Vargas Llosa, The Perpetual Orgy (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1986), 9.

Sven Birkerts, “Flaubert’s Anatomy.” The American Scholar (Washington, DC, Winter 2004), 138.

Richard Ellmann, Oscar Wilde (New York: Vintage, 1988), 221.

Oscar Wilde, Selected Journalism, ed. Anya Clayworth (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 204.

The Cambridge Companion to Flaubert, ed. Timothy Unwin (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 1.

James, 319.

The Letters of Gustave Flaubert, 1857-1880, Francis Steegmuller, trans. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. Press, 1982), 243.

The Letters of Gustave Flaubert, 1830-1857, Francis Steegmuller, trans. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. Press, 1980), 227.

James, 315.

Julian Barnes, “Gustave Flaubert’s Last Letters,” review in The Times Literary Supplement (12 March 2008).

The Letters of Gustave Flaubert, 1857-1880, 180.

Lettres de Gustave Flaubert à George Sand, précédée d’une étude par Guy de Maupassant (Paris: G. Charpentier et Cie, 1884).

Correspondance / Gustave Flaubert, précédée de souvenirs intimes par Mme Caroline Commanville (Paris: G. Charpentier, 1887-1893).

John Charles Tarver, Gustave Flaubert As Seen in His Works and Correspondence (Westminster: A. Constable, 1895).

OEuvres complètes de Gustave Flaubert: Correspondance. 9 vols. (Paris: Louis Conard, 1926-1933).

Gustave Flaubert, Correspondance, édition établie, présentée et annotée par Jean Bruneau et Yvan Leclerc. Index par Jean-Benoît Guinot, et al (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 1973-2007). Note: There is a very good one-volume selection of Flaubert’s letters (in French) in paperback published by Gallimard in its Folio Classique collection, edited by Bernard Masson. It is culled from the Pléiade edition.

The Letters of Gustave Flaubert, 1830-1857, 173.

James, 295.

The Letters of Gustave Flaubert, 1857-1880, 139.

James, 295.

Barnes.

James, 315.

The Letters of Gustave Flaubert, 1830-1857, 113.

Ibid., 145.

Ibid., 151.

Ibid., 152.

Ibid., 154.

Ibid., 154.

Ibid., 157.

Ibid., 158.

Ibid., 158.

Ibid., 166.

Ibid., 166.

Ibid., 173.

Ibid., 175.

Ibid., 179.

Ibid., 190.

Ibid., 190.

Ibid., 203.

Ibid., 215.

The Letters of Gustave Flaubert, 1857-1880, 275.

The Letters of Gustave Flaubert, 1830-1857, 211.

October 9, 2025

Autumn in New York

What a lovely song that is. So much like the season itself. I get all funny when I hear it.

“Autumn in New York, Why does it seem so inviting?”

Inviting, the city is.

Autumn, when everyone in New York looks beautiful and strong. In the summer, the women wear light dresses, and you can see their hair flowing and skin everywhere, and it excites the blood. But in the fall, the crisp days and the rich, bright wools women wear, their confident stride and flushed cheeks make you think you’re seeing them at their best.

When the temperature cools, when it’s brisk outside, and the sharp air braces me, I can walk for miles and miles. And I do. I set out from my apartment in the Village and walk until I can’t. In the fall, the crisp, cool air enlivens me. Swirling around my head, enlivening my face, pushing my stride. There I am, walking willy-nilly; it doesn’t matter where I’m going, as long as I’m going.

Is it along West Fourth Street, toward the Hudson River? Or down old Second Avenue? Or across Houston, skirting the edges of Soho and Greenwich Village? Or up Broadway, from one world to another? Walking in New York in the fall is a love affair. Anywhere and everywhere—it doesn’t matter. While it’s here, fall gets the blood flowing. It gives me a steed-like energy. On and on I go.

Fall aches within me, the precursor to death, and I carry that ache, knowing that fall will fade, leaves will drop, and branches will become skeletal. The dead season will arrive. I’ll feel that coming death and mourn. It reminds me of my own. I can feel it arising within me, and that’s why I have the urge to walk, walk, walk before I can’t.

I’m speaking of fall in New York, not in Vermont or some other leafy state where the experience is not the same, though the ache of change and loss is. Fall means the city to me.

In the late November afternoon, when the light is dying and the temperature lowering, if I’m in Greenwich Village, I walk into Bruxelles, a long-ago bistro off West 13th Street.

I go in for warmth and a paper-lined, silver cupful of their hot, salty French Fries and a strong Belgian beer, the cold still swirling about my face, as I eat and drink and restore my body and mind. I feel like I’ve earned it. I’ve walked the city until my legs are weak. I’ve seen everything so clearly, every bit of cityscape has entered me. I still have it all inside me, to this day. I eat and drink happily.

In autumn, I experience a bittersweet tang that brings the body and soul a potent mixture of joy and melancholy, and I’m hardly able to stand it.

October 2, 2025

The personal trainer

My wife, Gaywynn, gave me an hour session with a personal trainer as a birthday present. I had been whining about not being in shape. This was very nice of her, and it was also a handy way of shutting me up.

Actually, I was looking forward to it. At my age, which is 80, I need to do anything and everything I can to detour the rapid degradation of my body. Note to people my age or thereabouts: staying away from a mirror is extremely helpful.

So, a few days ago, I arrived at the gym, ready and willing. The trainer introduced himself. His name is Brian. He is huge. Like some sort of redwood. Even the loose track suit he was wearing looked tight. If you put him on a pedestal, you’d think, who did that statue? I’m running out of comparisons.

Clipboard in hand, he sat me down and began asking me a series of questions. He’s an affable guy. As he listened to me, he jotted down little notes. Even his hands seemed muscular.

“What are your goals?” he asked.

“Well,” I said, thoughtfully, “I’m not sure what’s a realistic goal at my age. Bench pressing 600 pounds is probably not within the realm of possibility.” Or is it?

“Probably not,” he said, an appealing smile appearing on his face. “Ok, let’s have you run through a few drills to see what sort of shape you’re in.”

He had me get on the treadmill first. He started the machine off at a slow walk.

“This ok?” he asked.

I think the setting was “Grandad.”

“Yes, good.”

I can do this. I can walk.

Note: this is not me.

Note: this is not me.He adjusted it several times to make it go faster. Then I started feeling like: where am I going? What is the meaning of life? Something about walking and going nowhere brings out the nihilist in you.

“Ok, good,” he said, noting something on his clipboard. What was it he wrote? “Alive,” perhaps.

He had me do a series of exercises. Curls with hand weights, push-ups against a bar, stepping up and down on a block of wood, etc. Then several sets using those menacing-looking gym machines that look like they had a supporting role in 50 Shades of Grey.

Pain? Pleasure?

Pain? Pleasure?When I completed an exercise, Brian said, “Good job!” Even if the exercise was fairly easy, he said it. It’s surprising how positively I responded to this reinforcing praise, even for doing something one step harder than tying my shoe. I nearly responded, “Gee, thanks, Dad!”

In fact, this made me realize that almost every male authority figure—teachers, coaches, bartenders, bus drivers, etc.—has been a father figure to me from whom I sought approval. Which explains a lot. And which makes me wonder if I’ve ever had a simple encounter with any male I’ve ever met in my life. Has it always been about seeking my father’s approval? Which makes me….wait a minute! I’m just here for a workout, not for analysis. Let’s get back to the machines.

Along the way I asked Brian about himself. Turns out that he got one of his degrees at the University of New Orleans where I taught English for eleven years.

“I actually grew up in New Orleans,” he said. “In Gentilly.”

That’s a neighborhood not too far from the university. I always thought it was such a pretty name, Gentilly. It’s also the name of a particularly delicious cake, a piece of which I could have eaten then contentedly instead of exercising. Followed by a sugar coma.

This…or exercise? Thoughts?

This…or exercise? Thoughts?But, no. Brian kept pushing me. That was his job, after all. That was the reason I was there. Because I was too damn lazy to work out by myself. And even if I did have the gumption, I wouldn’t know what to do. Unsupervised, I’d probably design a workout for myself that I could do while watching TV. So, deep down, I was glad to be in Brian’s hands. Clearly, he knew what he was doing. Clearly, he had a plan. There is something so gratifying about putting yourself in the hands of someone who’s capable.

He kept pushing me and writing notes down on the clipboard.

I began to get tired. How much longer is this workout? I thought at one point. I didn’t say that out loud, mind you. I didn’t want to be put in the “Wimp” section of Brian’s report. The thing about a trainer is that he knows you want to quit. But he won’t let you, despite whatever woebegone, melodramatic look you assume, however hard and pitifully you pant. And, believe me, I did—all of that. At one point, I was grunting like a feral pig. He ignored me.

This didn’t work with Brian.

This didn’t work with Brian.A few more exercises, and then, finally, it was over. I was spent. My chest was heaving. I was sweating. But I felt good. I’d lasted.

“Good job! You did really well,” Brian said, reaching down from his height and shaking my hand.

I really think he meant it. It sounded like he did.

I thanked him, and we made an arrangement for me to come for a second session that following week. I walked out of the gym feeling wrung out but slightly heroic. That’s the thing about a real workout, isn’t it? You make yourself, in a very small way, and for a very short time, a hero.

When I got home, I began the conversation with Gaywynn,

“My personal trainer said….”

September 25, 2025

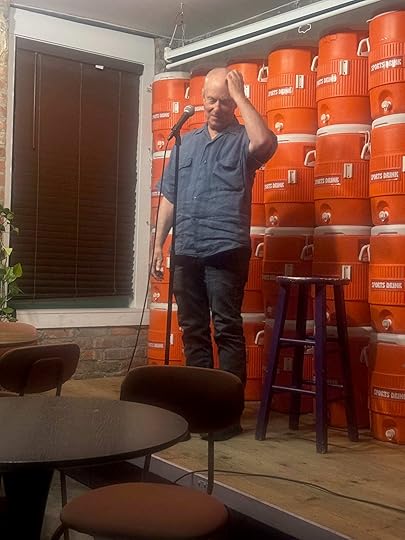

Comedy tonight!

It was my friend László who said I should do this. Stand-up comedy. László is the kind of guy I listen to. He’d done stand-up a few times before in New Orleans. So when he told me a few weeks ago that there was an open mic in New Orleans a few Sundays away, I said, without thinking, ok, yes, I’ll do it. Now that I’ve turned 80, is there no better time to take risks?

I’d actually wanted to do this for a while. I just needed a push.

Then came the panic. I’d never done stand-up comedy before. That’s comedy in front of an audience, I reminded myself, a live audience. Yes, I’d done a few jokes in front of my mirror, but that’s really not the same thing, is it?

Write what you know is what they say. I thought that would be a good guiding principle for my stand-up material, as well.

I’m 80, as I said. That’s one thing I know. I’d begin with that.

László told me that I should have a solid three minutes. And that I should read it out loud ahead of time so that I gave myself room to perform, not just to say the lines quickly, one after another. I began to jot down material. And more. And still more.

My wife, Gaywynn, was forced to listen to my jokes so many times over the next few weeks, she must have wanted to join a convent. Or worse.

At one point, I called my daughter, Becky, a brilliant comedian who’s been performing comedy in front of audiences for years, including many open-mics. I walked her through my material. She had some sharp ideas and suggestions. I was grateful for her to have my back.

After much uncertainty, I had my three minutes. For better or worse. Was it funny? The audience would be the judge.

The day came. Nothing but to do except go, do my best, and let the chips fall where they may.

The venue was a place called Sports Drink. It’s off Magazine Street, uptown, in New Orleans, for those of you who know the city.

“So, you’re here for the open-mic?”

“So, you’re here for the open-mic?”Gaywynn and I arrived around 6:30. Sign-up was at 7. The show would begin at 8. Sports Drink is small. I think at one point or another, we’ve all been in these kinds of places. Maybe in college. Often, they’re in basements. I watched as others signed up, one after another. All of them young.

Some friends showed up, thankfully. Olivier, a friend from days teaching at the University of New Orleans. And Skye, a former student and now a friend. Plus, László, of course. He was going to perform, too. And his girlfriend, Rachel, and two friends of theirs who I hadn’t met. I was glad to see their enthusiastic faces, because the room was nowhere close to full.

The host for the evening gave us the order of when we would perform. I would go third. That was a relief. I wouldn’t have to go first, and I wouldn’t have to wait forever, stewing in my own anxiety. And I had a bit of that.

Then, a little after 8, the evening started. I watched the first two comedians. They got some laughs. But what became crystal clear to me was that the audience wasn’t going to give them or me or anyone else anything for free. If I wasn’t funny, there would be no laughs. Just silence.

My turn.

I stood up, went to the stage. I leaned into the microphone.

“Can you hear me?” I asked.

“YES!”

Then:

“Hey, how’s everyone doing? It’s good to be here!

I’m old.”

Then…I hear…laughter!

Thank you, Jesus!

Think funny, Rich! (Photo by Skye Jackson.)

Think funny, Rich! (Photo by Skye Jackson.)I kept going:

“I have enough ear hair now to make a hair transplant for my head.

And I need it. If I don’t have enough, I can go to my eyebrows. As a last resort, my nose.”

A few more laughs! I even heard laughs from the other side of the room where people that I didn’t know were sitting.

After I shook some off the nervousness, there were a few moments when I was actually enjoying the experience. I was performing, and it seemed like I was doing all right. Not everything I said got a laugh, some of it didn’t land, but there was laughter.

I could see why people do this. It can become addicting. You want that fix, that narcotic laughter. It shoots through your veins like heroin. More! I want more! It feels soooooo good!

Then, there it was—my last line. I was done. I stepped off the stage and went back to my table, sat down and exhaled. Everyone congratulated me. That was nice. But the main thing was, I’d done it. 80 years old, and my first stand-up! The rush made me feel 50. It took me about three weeks of work and anxiety to put together three minutes of material, but it was worth it.

Here’s the video Gaywynn took of me. I’m posting the first half of the set. It’s about 1 1/2 minutes. I hope I’m funny.

After the last set of the night, we all went outside. László told me he had another club he wanted us to try. Would I want to do it again? Maybe in a few weeks?

I would.

Box checked. What’s next? Whatever it is, it should be something outside my comfort zone. That’s where I really feel alive. At 80, I want that.

September 18, 2025

The man with the wispy laugh

There are just a few passing references to him I found on the Internet. Nothing substantial. I searched high and low. There’s not a single photograph. Nowadays, that’s almost as if you never existed. Ridiculous, isn’t it?

Dennis D’Amico.

He was an advertising art director. We both worked at the same New York ad agency, Ally & Gargano, for a few years in the early 1980s. After we worked on some advertising campaigns together, we became friends.

He was tall, with dark hair and a neatly-cropped moustache. He spoke with a wispy voice. He was fastidious in his dress and in everything else. His office was always immaculate, everything in its place. He worked mathematically, with precision, using his tools like an architect or master builder. He often liked to work standing up. He did not like the sprawling, the unruly, the chaotic. He loved what he did. He worked hard at it.

He liked to laugh. His laugh was the same as his talk, wispy. He found things that he thought were funny around the agency, especially people. There was plenty to laugh about at that ad agency, plenty of eccentric characters, plenty of the outlandish.

We worked on the Traveler’s Insurance account. We produced print ads and television commercials, two of which we shot in California. I liked working with him. If he thought a headline I came up with was substandard, he told me so. He was stubborn. He wouldn’t back down. That never bothered me. Well, maybe for a minute or two.

Dennis at my apartment in NY sometime in the early 1980s. I only have two blurry photographs of him.

Dennis at my apartment in NY sometime in the early 1980s. I only have two blurry photographs of him.He often worked late. I remember wandering into his office at 7:00PM one evening, and there he was, only a desk light on, radio playing low. Why do I remember the song? “People Who Died” by Jim Carroll. That same evening, a brilliant, hilarious female copywriter strolled in. “I had a coffee enema today,” she announced. “I could pass the white glove test.” Dennis and I looked at each other. We had one of those silent takes you have in those kinds of speechless situations. Every once in a while, Dennis and I would look at something we did, and one of us would ask, “Can it pass the white glove test?”

He owned a house in the Berkshires with his brother. He invited me up a few times, and it was good to see him outside of work. He and his brother were always working on some part of the house. I remember going up in the fall and, once, in the winter. The Berkshires are beautiful in any season, and I was grateful he asked me to be there with him.

Dennis was the first person at the ad agency that I told about my love affair with Jerilyn, the rough-and-tumble office manager of the agency. We kept our love affair a secret, because, I think, romances between employees were not allowed. Or maybe we just wanted to keep it secret. But I told Dennis.

Then he started dating Betty—I wish I remembered her last name!—who worked as an assistant at the ad agency. Eventually, they married. They were a good match. They were happy. I was glad to see him in such a good state.

I left the agency, went to France, wrote a book. Dennis and I lost touch after a while. I came back and tried to get back in touch. I wrote him a letter or two to his Berkshires address but never heard back. Then I heard, somehow, that he was sick. He had cancer. I tried to find out if he was in a hospital and, if so, which one. No luck.

Then, sometime later, I heard he’d died. I don’t know how old he was when he died, but I can’t believe he was over 50.

One day, I ran into his wife, Betty, on the street. It had been a hard death. “It was terrible,” she said. “And he was so young!” she said. I wish I’d seen him one last time before he died.

There is one picture I have of him in my mind. I don’t know why. It’s a bit absurd, but it expresses a certain outsized relentlessness Dennis demonstrated sometimes.

It’s winter. I’m up at his house in the Berkshires. It’s snowing fiercely, and it’s very cold. Dennis insists on barbecuing outside, despite the weather. He puts on heavy clothing and takes a tray of raw steaks outside into the swirling frenzy. I can see him at the grill, turning the meat, his figure almost obscured by the snow. He keeps at it. Then, finally, he comes back in with a tray of smoking, charcoaled meat. His moustache is almost white. He’s got snow on him everywhere.

“Leopard dinner!” he says, and then gives a wispy laugh. He puts the tray down and takes off his outdoor clothes, snow falling everywhere. “Let’s eat before it gets cold,” he says, and we do.