John Bascom's Blog

September 6, 2023

The Motleytown Bonefish Extravaganza

THE MOTLEYTOWN BONEFISH E XTRAVAGANZA

A couple on a hastily arranged

bone fishing trip find themselves

in an odd place with eccentric people

From the collection "Beneath a Hunter's Sky" by John Bascom

“What would you like to do with your timeoff?” Laura asked. I had one unused week from my prior year'svacation allotment that would be lost if I didn’t use it by the end of April. Time was running out.

“Honestly? What about bonefishing in the Bahamas. The weather iswarm and sunny this time of year, and you'd love seeing the flats around AndrosIsland. Where Jack Verdon and I went.”

“Is it nice there? Wherewould we stay?”

“Jack and I were at the Bonefish Club on the NorthIsland. It's Spartan but clean andcomfortable. Last time he went byhimself, though, he tried a different place. Where the accommodations were more basic, but there's less fishingpressure and the action is better.”

“But it's next week. Isit even possible?”

“Won't hurt to give it a try.”

“If you say so,” Laura said.

I Googled it and came up with a phone number. The basic website confirmed it was the oneJack had mentioned, on Littlesalt Cay by the south bite.

“Motleytown Deluxe Resort an' Bonefish Lodge. Lindsey Motley.” A man's voice answered with the classicBahamian dialect I had come to know during my visits there.

After identifying myself and exchanging a few pleasantries, Isaid, “Yeah. My wife and I are lookingto come down there for a little bone fishing. Is that something we could set up with you?”

“Oh…ya, mon. Bonefish,dey be our specialty.”

“I was thinking of a few days next week.”

There was a long silence.

Finally, “No, Suh. Weall full. Duh guess, dey mus book tree,usually six muns ahead. Sometime ayear. No way nex week.” His voice sounded both incredulous andirritated at my stupidity.

“Look,” I said. “I'monly talking a night or two. And we'reflexible. We could pop down anytime nextweek. Is there anything...?”

“Jus one minute, Suh…” I could hear him flipping pages in what I imagined was a reservationregister.

After a few seconds he came back on the line. “We may put you in duh annex, Suh. Dey iz one vacancy dere. But yas mus come Tuesday and be gone byTursday in duh mornin. Dot be okay?”

I was able to book a charter in a beat-up old four-passenger twin outof Fort Lauderdale, direct to Motleytown, Andros Island. I sat in front to the pilot's right, while Laurarode in one of the backseats. Theupholstery was worn through with a few wads of remaining stuffing pokingout. Black crankcase oil flowed in alittle rivulet from a crack in the right engine cowling back and into theairstream. The paint, what was left ofit, was faded, scratched, and worn through. Little bare-aluminum riveted repair patches dotted the metal skin. The radio the pilot used—apparently the onlyone working among the aging relics—was held in place beneath the instrumentpanel by nylon tie-wraps. Bundles ofwires wound everywhere. We were out ofsight of land.

“Is this safe,” Laura said in a weak voice, more a concernedstatement than a question.

Our final approach to the short and narrow crushed-shellairstrip was over a wet marsh. A wreckedSeneca II twin, much like one I had trained in back in the day, sat half-submergeda few hundred yards short of the runway, its engines gone and doors sprungunnaturally forward.

“Been there more'n twenty years,” our pilot commented. “Longer'n I've been comin' here.”

We hopped out and walked to the little open-sided woodenpavilion where a heavyset, squat and bald black Bahamian stood waiting. His red cap, peaked in front like those that elevatoroperators wore when there still were any, had the word CUSTOMS across the front. Awooden, crudely hand-lettered sign nailed crooked to a post announced, WELCOME TO THE BAHHAMMAS, the name ofthe country clearly misspelled.

We signed a form and showed our passports while the pilotoffloaded our luggage. That pretty wellcompleted our official reception.

“A cab was supposed to meet us,” I said to the agent.

“Over dere, Suh,” he said, pointing to a rusty, unmarkedvintage car a few yards behind the pavilion. There was no one in it.

We carried our gear to the vehicle and looked around. The customs agent had followed. He opened the driver's side, slid behind thewheel, removed the customs hat, anddonned a similar but yellow one that read CABacross the front. Laura and I lookedat each other, loaded our luggage, and hopped in the back.

“I Lindsey Motley,” the driver said as we pulled away. “Welcome ta Motleytown.”

The Motleytown Deluxe Resort &Bonefish Lodge was an aging, two-story mortar structure like those of thebygone fifties-era motels one sees in the dying beach towns of mid-Florida'sAtlantic coast. The once-whitewashedexterior was stained with gray streaks and blotches. Inside, the wooden floor was darkened anduneven. What served as a registrationdesk sat along one wall in the small combination lobby-bar.

After Lindsey checked us in, he said, “Ya care for a drinkfrom duh bar before goin to yas room?” He motioned to the dark, old wooden bar along the opposite wall, itsveneer warped and separating in places.

“Sure. I'll have avodka and tonic.”

“White wine, please,” Laura said.

He walked behind the bar and placed a conch-colored baseballcap on his head that read MotleytownDeluxe Resort, and under it, BARTENDER,all in brown letters.

We sat on unsteady barstools and sipped the drinks that wereparticularly refreshing after our daylong travels.

“What ya like fer ya suppuh, and at what time ya eat?” Lindseyasked.

“Whenever and whatever your other guests are doing is finewith us,” I said. “We'll go with theprogram.”

“Ah…Suh…,” he said. “Yaan duh Missus be duh only guess. Iz ferya ta say.”

Our quarters on the secondfloor were accessed by anexterior wooden stairway. There was abedroom, sitting room, and bath, all surprisingly spacious. The floors were peeling linoleum tilesquares, the walls stained plaster with a few holes punched here or there. The door jambs were all out of square. The toilet stool had gaps between its baseand the tile, the plumbing visible in the floor below.

“Nice,” Laura said, her sarcasm obvious enough.

“Lindsey said the fishing skiff will be across the street bythe pier off the beach in the morning.” I was trying to change the subject. “We'll meet our guide there, I guess, around eight sharp. After breakfast. I checked, and the weather should be fine.”

She nodded glumly. Itwas a bad sign.

We arrived in the dining room for supper just off the lobby atthe appointed time, seven in the evening. It was still bright outside.

Lindsey walked into the room wearing a French-style, high andpuffed white chef's hat. Red letteringaround the band said Kiss the Cook.

“What I fix ya fer tonight?” he said with a happy smile.

“So you're the cook, too!” I said. “Hope you're getting paid for all this.”

“Da regla cook be from Arizona,” he said. “Was in duh prison dere. He gun leff hare sudden lass night. Dey find him, I tink, he hadda go verfass. I take care'ah yas, doe.”

I hadn't seen a server, either. “You the waiter, too?”

“Waitress be duh girlfrien. Har goin wit dot mon, duh cook. Ibring ya duh food, okay?”

“A lot for one fellow to do.”

“My brudder, Umfry. Hebe over ta Nassau today, but gun come hare tonight. He duh big boss, duh owner. He help me out when he get hare.”

“So Humphrey's the owner of the Motleytown Deluxe Resort?” Isaid more than asked, clearly pronouncing the “H”.

“Umfry,” Lindsey said. No “H”.

“Humphrey?”

“It be Umfry.”

“How do you spell it?”

“Umfry,” he repeated, not spelling out each letter.

“Okay, then,” I said.

Dinner was a surprisinglynice, fresh yellowtailsnapper with rice and beans. We enjoyeda good tossed salad with a cookie and coffee for desert.

The bed was lumpy but passable. Laura and I both read for a while, she dozingoff and me getting up to use the bathroom. I opened the door from our bedroom to the main room and switched on thelight. The biggest cockroach I'd everseen scuttled away under the glare of the single bare bulb.

I swear I could have thrown a saddle over him and broke himright there. But I took the book I wascarrying and hurled it down on him. Itwas a perfect hit, the book landing flat and hard directly on thesquirrel-sized insect with a loud bang.

“Bingo!” I thought. “Oneroach down.”

The thick hardcover novel bounced off the bug. It continued on unfazed, as if nothing hadhappened. I grabbed the book from thefloor and gave chase, intending to administer another crushing blow. The cockroach scurried beneath the wide gapunder the bathroom door. In fastpursuit, I threw it open in time to see him dive beneath the toilet basethrough the gap in the floor.

“Damn!” I said out loud. I used the toilet quickly, one eye on the opening, then returned to bed,careful to close the doors behind. Inever said a word to Laura.

After breakfast Lindsey confirmed we were to take our thingsto the pier directly across the dirt main street, the harbor road ofMotleytown.

“Umfry, he gun be hare dis night,” Lindsey told us as we roseto go to our room and collect our gear.

“Fine,” I said. Ithought I remembered him saying last evening Umfry would be here this morning,but I really couldn't see what difference it made to us either way.

The beach was a heaping mound of broken, pink and white conch shellsthat stretched along the shore as far as one could see. A collection of aging wooden boats rode at anchora few yards off the beach. Near the endof a sagging, twisted wooden pier sat a classic sixteen-foot or so bone fishingskiff with a forty-horse Johnson outboard, a level casting deck across the bow,and a poling platform extending on legs above the stern. There were three plastic bucket-typeseats. No one was around.

We waited for ten minutes. With no guide in sight, we began loading our tackle and day-bags. “Maybe Umfry was supposed to be the guide,” Isaid absently to Laura. Then I sawLindsey ambling, big and awkward, down the pier. As he drew close, I could see the dark bluelettering on his white baseball cap. GUIDE, it read.

We took off across the harbor on a splendid, sunny Caribbeanday, the water gin-clear but reflecting from the sky—from the varying depthsand bottom-cover—lovely hues of blue, green, tan, or a mixture of differentshades and intensities. The deepertrenches, channels, or holes in the bottom were well defined in very dark,sometimes midnight blue. The breeze waslight and our mood fine.

About fifteen minutes out, a few miles from shore, a large,gray shadow floated across the shallow bottom fifty or so yards off ourbeam. “What's that fish?” I askedLindsey.

“Dot be ver big hammerhead,” he said. “Dey dangerous.”

Perhaps a half mile beyond the hammerhead shark, I noticed aman standing in a small boat and waving his arms frantically. I pointed.

“Dot fella, he boat be broke. He want duh ride back home,” Lindsey said. It was obvious he had seen the boat wellbefore I had. He motored on, clearlyintending to ignore the man and his plight.

“Go on over there,” I said.

We pulled alongside the stranded skiff. Its outboard engine cover had been removedand was in the water, tied to a fraying length of old rope as some kind ofmakeshift sea anchor. The bay wasshallow enough to see the sand bottom a dozen or so feet down. The interior of the old wooden boat heldstanding water. There was no spare gascan or oars to be seen.

The two Bahamians exchanged a few rapid, unintelligible wordsin their local, oddly cadenced dialect.

“He say he be stranded duh night,” Lindsey explained. “Motor be broke. He come from duh fishin trawler out by duhdeep ta go ta Motleytown, see duh girlfrein little while. Dot hammerhead, go roun dot boat all duhnight. Want duh ride in. I say ta dot boi, no, I got duh clients, ameestuh an madam.” He started the engineand began to pull away.

“Hold on,” I said. “It'sonly fifteen minutes back. Tell him tohop in. We'll take him to the pier.”

The stranded fellow beamed from ear to ear as he climbed intoour boat.

“Tank you, tank you,” he smiled, taking my hand in his andpumping it. “What kine-ah fish yalike. I bring ya some fer yassuppuh. Ta duh resort were ya be.”

“Gotta love fresh grouper,” I said.

“Sure…sure, duh grouper be good. Be dere fer ya dinner dis night. Tank you. Tank you.”

Across the bay, our stranded sailor safely back at thepier, Lindsey cut the engine and poled the skiff slowly among themangroves. We searched the shallow,clear water for any moving shadows that might signal bonefish.

“Dere, dere Meestuh Rob.” Lindsey strained to bend at the waist to keep his profile low and setthe pole. The boat twisted about thepivot point of the pole held into the bottom.

“Where?” The boat wasturning. Finally I saw the three graymoving forms gliding beneath the surface forty yards to our right.

“Look there!” I said to Laura. “About one thirty, moving parallel to shore, toward us. Cast well in front of them so they won'tspook and scatter.”

Laura had one of my spinning rods with a pink lead-head jig,the hook baited with just of bit of crab Lindsey had brought, just enough togive the lure some scent and flavor. Shetossed it only twenty yards out to the side. I doubt she saw the barely visible fish, but the jig landed right intheir path.

“Let it sink and lie on the bottom. Don't move it, and stay low,” I said. I could feel the excitement building.

The three bonefish moved to within a few feet of hermotionless lure.

“Barely twitch it,” I said.

She moved the tip of her rod slightly as one of the shadowsapproached the very spot where her bait had splashed into the water less than aminute earlier. Her rod bent sharply asthe drag began to sing.

“Fish on!” I half shouted and laughed.

The fish made a hard fifty-yard run before stopping but stillkeeping Laura's rod tip bent well down.

“Work him back in,” I said. “Lift the rod and reel as you lower it again. And keep the line tight.”

About ten yards from the boat, the bone made another run, notas long this time. She repeated theprocess of pumping him in. The wholething was repeated one more time. As shebrought the fish alongside the final time, I reached in and scooped him up witha hand. He was about a three-pounder.

“I had no idea they were so strong.” She was grinning and looking at her fish.

“He had a lot of fight in him for his size.”

“Is he a big one?”

“Fairly good,” I fibbed.

“He took so much line, I thought I'd run out.”

“You did great.”

“Let's take him back for dinner.”

“I'm afraid catching them is just for fun. They're not good eating. Like the name suggests, too many bones.”

I removed the jig hook and carefully slipped him into thewater. He took just seconds to recoverbefore swimming quickly away. Lindseywent back to poling the skiff, but after a few minutes, there was noisysplashing in the water near the shoreline where we had released the fish.

“Shark get him,” Lindsey said. “Dey smell da blood an follow afta dem like duh houn-dog.”

Lindsey's poling was lackadaisical. He stopped to rest and look aroundfrequently. We moved between the mangrovesand up a little tidal creek.

“What's this creek called?” I asked him.

“Dot be Freshwater Creek.”

“It's the same name as the one on North Andros up near theBonefish Club where I fished before.”

“Ya, Meestuh Rob. Deyall be called dot cause duh water be fresh, not duh seawater.”

Even with our slow pace and periods of inactivity, Laura and Ieach caught several more bonefish. Shecontinued with her spinning rod and jig, while I used a sturdy saltwater flyrod I'd brought with a bulging-eyed pink shrimp imitation. At one point I spotted a very long shadow lyingjust below the surface over slightly deeper blue water.

“Is that a bone?”

“Barracuda,” Lindsey said. “Dey like duh needlefish dot be on dis flat. Take dot rod dere and cass at him.”

A sturdy spinning rod lay beside the seats along onefreeboard. It was baited with a long,lime-green tube-lure made of colored rubber surgical tubing slipped over a wireleader. A lead weight capped one end ofthe tube, and three treble-hook gangs, attached to the wire leader beneath, protrudedat intervals through the tubing along its length.

My cast was about a dozen yards beyond the cuda and a fewyards in front of what I took to be the shape of his head.

“Reel fass, Meestuh Rob. Fass as ya can!”

I cranked with all the speed I could muster. As the lure approached the spot where I hadlast seen the fish, the water seemed to explode. The rod pulled parallel to the surface beforeI could haul it back and create the proper bend. I worked the fish to the boat, overcominglong runs, hard pulls, and lots of thrashing. Finally Lindsey used a gaff to bring him aboard in the stern beneath thepoling platform.

“Our guess doan eat dese,” he said. “But we boil dem ta get duh poison out. Den dey vere fine.”

We had seen many rays and small sharks gliding over thebonefish flats. Big starfish lay alongthe bottom.

“What kind of sharks are these?” Laura asked at one point.

“Dey san sharks, Madam,” Lindsey said.

“Do they bite?”

“Oh, no, Madam. Deymosely eat duh crab or udder fish.”

“Can we try to catch one?”

Lindsey lazily poled the skiff up a brackish creek with thetide flooding in. He anchored in thechannel and baited the big spinning rod with a plain treble-hook and chunk ofmeat from the head of our barracuda. Hehanded the rig to Laura.

“Hole duh hook about tree feet above duh bottom, Madam.”

It couldn't have been ten minutes before the rod bent doubleand the drag began to run out. Laurafought the fish for another twenty minutes or so, using our techniques for thecuda and bonefish. Finally she pulledthe head of a nice sand shark just clear of the surface beside the boat. We could see through the clear water it wassomething over four feet in length.

“My gosh, look at that shark!” Laura said. She was squirming in her seat fromexcitement.

Lindsey had grabbed the gaff.

At that point the fish opened its mouth wide, lunged from thewater, and bit hard. The braided steelline separated beneath its teeth like string. The shark fell back into the creek and disappeared, leaving the frayed,kinked end of the wire leader dangling in the breeze. I think Laura was more thrilled by thedramatic and violent escape than hooking her shark and bringing itboatside.

Lindsey brought in the anchor and poled the skiff a few yardsto a sandbar on the edge of the creek. He beached the boat.

“I be goin get more crab back in duh mangroves,” he said. “Yas rest here one minute an haf ya lunch.” He disappeared.

“I guess he's a good guide,” Laura said after he was safelyout of earshot. “We've each gotbonefish, there was your barracuda, and then my shark.”

“He poles in slow motion.” I measured my words, not wanting to throw cold water on the trip I hadput together for us. “Rupert up at theBonefish Club on North Andros works three times as hard. We cover way more ground and he spots lots offish. I'm sure we missed a ton. And there are no rest stops with Rupert.”

We enjoyed the sack lunches Lindsey had provided and took inthe beautiful scenery. It was a half hourbefore he finally returned with no crabs.

We poled and waded flats for the balance of the afternoon,landing another bonefish each before returning sunburned and wind-drained toMotleytown. Dinner was more yellowtailsnapper like the previous evening. Itcame as no surprise our rescued seaman hadn't shown with the promisedgrouper. Still, the evening was good.

“Umfry, he be hare in duh mornin,” Lindsey said as we left thetable and headed up to our room.

Laura and I just looked at each other. She rolled her eyes.

“Sure,” I said to Lindsey.

In our room, we packed most of our things for ourcharter back in the morning. We readuntil well after dark. The only bar intown, a ramshackle place just next door with warped plywood over some of thebroken-out windows, rang with talk and shouting and laughter. Soon the raucous group of locals spilled intothe dirt street beneath our window.

“It may be a long night,” I said.

“I'm so tired I'm sure I'll drift right off and sleep like alog,” Laura said.

“Do you think there really is an Umfry?”

“Maybe he's Loa, the invisible voodoo spirit,” she laughed.

“Or Lindsey's imaginary friend.”

“Maybe Lindsey is Loa,” she kidded.

“Or the real Umfry using an assumed identity. Maybe he's the fugitive cook from Arizona whohas murdered the real Motleys.”

“Honestly, though, even with everything it was spectacularout there. I never could have imagined.”

“We actually did fairly well on the fish.”

“It's one thing to see a place, like on a tour. But to actually be in it, participating inwhat it's all about, that's something altogether different.”

“We'll remember this better than if we had been at a firstclass place like the Bonefish Club.” Both of us broke out in laughter.

We had undressed and were sitting on the edge of the bed. I reached over and laid my hand on hers.

“I had such a wonderful time,” she said. “With you. I'm so glad you arranged this, with the short notice and all.”

“Speaking of which…” I said. “I'll have more vacation in a month.”

“And just what would you like to do?” She arched her eyebrows.

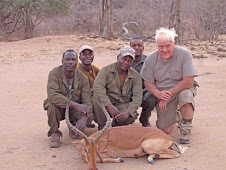

“Actually, I've always dreamed of a hunt in Africa. And it's getting nice now. In May. The rainy season has ended.”

“Are there decent accommodations? Where in the world would you have us stay?” She sounded skeptical, and I knew she wastoying with me.

“If we're talking about next month, the good places arealready booked. They're tied up a year,two years in advance. All right,sometimes three. But I heard about a newplace. Pretty basic, but less well knownand off the beaten path. A littlerougher, really, but the hunting is supposed to be better.”

“Is that even possible? To arrange something like that with so little time…” She lay down on her side and pulled the sheetup.

“Wouldn't hurt to give it a try. I'll call tomorrow night when we're home.”

She raised up on an elbow, smiling, and kissed me lightly onthe lips. “Nice try, but not a chance, Mister.” Then she switched off the light.

______________________________

The Motleytown Bonefish Extravaganza is a short story from the collection Beneath a Hunter's Sky by John Bascom, available on Amazon.com

May 28, 2021

Coming Home!

COMING HOME

the concluding installment of

by John Bascom

On April 30, 1945 Hitler committed suicide in Berlin. On May 7, all of Germany formally surrendered. The war in Europe was over.

In the Pacific, however, war continued to rage. U.S. forces had successfully prosecuted their island-hopping campaign, moving closer and closer to the Japanese homeland. By mid-1945, the Philippines had been retaken, and the island of Okinawa, the closest to Japan itself, had been seized. The Japanese air and naval forces had largely been destroyed. Intense daily bombing had devastated Tokyo and other key industrial cities and ports. Plans were underway for a massive land invasion of Japan. Estimates called for a ten-million-man invasion force, with over a million American casualties expected. Word quickly spread through Allied forces in Italy that they would soon be sent to the Pacific, a massive logistical undertaking.

In Italy, the main business was maintaining order. Power abhors a vacuum, and partisan factions had begun fighting among themselves. In the west, France had moved to claim long-disputed border territory and was threatening to enter Italy. It was up to the Americans to assure a peaceful and orderly transition to civilian rule.

Generals visited troops, made speeches and decorated soldiers. Dad was awarded the Good Conduct Medal there. He received medals and ribbons for his role in the Arno, North Apennines and Po Valley campaigns. In early August, news came of the atomic bombing and surrender of Japan. There would be no redeployment to the Pacific.

The troops moved south to await transport back home. There were nearly a million Allied soldiers in Italy, and marshalling them for deployment home was a gigantic logistical task. My father at some point visited Rome and Pompei on leave as a tourist while awaiting his turn. There, he enjoyed the scenes and collected souvenirs. He was promoted to Pfc, the highest rank he would attain. On October 22nd, he boarded ship in Naples, disembarking at Camp Patrick Henry in Virginia on November 3rd.

He arrived back in St. Louis around November 9, 1945 and was formally and finally honorably discharged from service with character and efficiency ratings of excellent. He had weighed 153 pounds when he was inducted; he was down to 138 for his exit physical. He had experienced endless months in the field, been wounded twice by artillery shells, and was hospitalized for hepatitis. He had watched his best friend die a gruesome death. Dad endured up to a month at a time in wet foxholes, dodged machinegun fire and hand grenades, and survived a mano-a-mano, eye to eye shootout at the war’s very end. But now he was home.

My earliest memory is of my father coming home, and I truly recall the event as clearly today as I experienced it at the time. I was just beyond two years old, only twenty-six months. I’ve been told the family had been buzzing about his return for weeks, but I remember none of that, though excitement surely rippled through my grandparent’s flat in South St. Louis. I recall my father climbing the long steps, smiling, his uniform starched and pressed, my mother giddy with arms-outstretched in anticipation. At the top of the stairs they embraced and kissed. And, an uncomprehending toddler, I remember wondering why in the world she was kissing the mailman, the only other uniformed man I had ever seen at our house. Then I slipped away and hid under the massive buffet table that stood along the dining room wall, peering out warily at the raucous scene that was unfolding.

My earliest memory is of my father coming home, and I truly recall the event as clearly today as I experienced it at the time. I was just beyond two years old, only twenty-six months. I’ve been told the family had been buzzing about his return for weeks, but I remember none of that, though excitement surely rippled through my grandparent’s flat in South St. Louis. I recall my father climbing the long steps, smiling, his uniform starched and pressed, my mother giddy with arms-outstretched in anticipation. At the top of the stairs they embraced and kissed. And, an uncomprehending toddler, I remember wondering why in the world she was kissing the mailman, the only other uniformed man I had ever seen at our house. Then I slipped away and hid under the massive buffet table that stood along the dining room wall, peering out warily at the raucous scene that was unfolding.

Memories of my father are scant in the few years following his return. He found work in Albany, New York, but not sure that it would work out for the family, we remained at the St. Louis flat of my grandparents while he commuted on weekends. For me, he was still not a part of my daily life. About eighteen months later, he found a good job in Minneapolis, and our entire family moved into a small frame house there. I was four years old. It was the first traditional nuclear family life I had experienced.

Dad settled into a typical routine. He worked hard at his job and did well. Ours was the classic suburban life of school, church, friends and back yard barbecues. My father experienced some drinking problems, but quickly got them under control. I never recall him taking a single drink. I experienced him as aloof and detached at times. Later, he displayed a few uncharacteristic angry outbursts over minor events. José Narosky, the Argentine author, famously said, “In war, there are no unwounded soldiers.” It must be true. Did the traumas of the Apennines warn him not to get too close, or cause him to burst forth in those occasional fits of barely constrained anger? I’ve often wondered.

Whatever his demons, they eventually faded. His life can fairly be described as long, productive, and successful. He enjoyed a good career, rising in the ranks to management levels in a major corporation. His marriage was lifelong and from all indications happy. His friends liked and respected him. He was loved by his wife and children. I never heard of him experiencing nightmares or flashbacks. He occasionally talked about the little things: seeing Rome, shooting the cow, the time his buddies dared him to swim across a lake, and he came head to head with a huge turtle. But he never spoke about combat. My mother and he must have talked, late at night, the children in bed, the house quiet and the lights low. The death of Woody, the killing of the German boy. It was she who, much later, secretly revealed these events to my sister and me. He and I made our peace in the end. Dad died quietly of cancer in July, 1985, seventy-five years of age.

It is over twenty years now that I vacationed in Tuscany, marveling at the rolling hills, the little walled medieval villages, Chianti vines heavy with grapes in the fall, my wife and I stopping to pick one, bursting with juice, as sweet as any candy. Sipping Brunello Reserve at the hilltop winery in Montalcino. Then, I knew nothing of the details I have shared here. Now, having learned the things I have in writing this, I resolve to return. I will visit the wartime places of my father, I tell myself. This time, I will go to Castel Fiorentino, traveling through Florence, not pausing there as I did on my first visit. I will go to Barbarino, to the places of the battles, to Bruscoli, Livergnano, where my father advanced inch by inch and house by house in the face of withering fire and grenades raining down from the clifftops, then to the Futa Pass. I will travel to Monte Bastione and contemplate what happened there. I will follow in my father’s footsteps, I say to myself, climbing the pathways the mules trod up the side of Mount Belmonte, pausing on the summits to hear the wind moving through the treetops as had my father. I will perhaps, quite unknowingly, stand on the spot where Woody Woodruff breathed his last. And I will turn my ear to the sacred ground and hear the whispers of the souls of Americans who have never left that place. These are the things I say to myself. As I write this, I am a seventy-six-year-old, burnt out and used up old man. Still, these things I say and resolve, and I will do it all.

What will the souls on Mount Belmonte tell me? Will they say that I would have performed as well, been as brave, suffered the terrors with the same fortitude as did my father? I think I would not, but really, I don’t know.

But one thing I am certain those souls will tell me is that wars are not fought and won by machinegun charging heroes. They are waged by bakers and cab drivers, salesmen and store clerks. Those who do not volunteer, who do not want to be there, but, like my father, answer the call when it comes. They are fought by men who show up, do their duty despite their fear, and then, for the lucky ones, go home again.

My father was such a man. He never, ever complained about his service. Dad received no medals for valor, but in the thick of violence he put his head down, and like his comrades, moved forward. And in so doing, he participated with the others of his time in defeating unimaginably powerful forces of evil. He stood among those to whom we all owe so much, those who journalist Tom Brokaw rightly called The Greatest Generation.

___________________________________________

This book is dedicated to my father, John Gay Bascom, to whom I owe so much, and upon whose shoulders new generations now stand

… John Bascom

May 11, 2021

Victory in the Po Valley

The Battle of the Poexcerpted from One Soldier's Story

by John Bascom

(After nine months of grueling mountain fighting, the Allies break the Gothic Line and the 34th Red Bull Division seizes the key Po Valley city of Bologna, the linchpin in the Nazi's defenses in Northern Italy. All that remains is to finish them off)

In late April, 1945 the Red Bull Division had finally cracked the Apennine Mountain Gothic Line, driven the Nazi's out of the mountains and taken the strategic city of Bologna. Now the 34th had bigger fish to fry.

What occurred in the ensuing week was one of the most daring, chaotic and successful moves in military annals. Rather than the classic pause to regroup and reconnoiter, General Clark grasped the opportunity to exploit the Germans’ panic and finish them once and for all. Instead of locating and attacking enemy units one at a time, he resolved to disorient them and prevent their retreat into the Alps by swiftly enveloping them in the Po Valley. There, all the advantages lay with us. Unlike the commanding and intimidating Apennines, the Po was relatively open, rolling and crisscrossed by good roads. The terrain was suitable for our superiority in tanks and equipment to move swiftly. The weather there was more accommodating to substantial friendly air forces. The Germans had essentially no air capability left. Still, abandoning our classic military defensive formations in pursuit of an elusive brass ring was a risky strategy. It left many of our units exposed to assaults should the German’s be able to regroup and reorganize. General Clark accepted the risk.

Allied units were ordered to race forward, bypassing areas of light resistance in a blitz of our own designed to disrupt and block the retreat of the enemy. The 135thRegiment was ordered to attack west along Highway 9 that ran parallel to the northern face of the Apennine Range. Germans were pouring from the mountains in an attempt to cross the Po River and establish new defenses.

The Regiment was ordered to capture objectives along Highway 9, initially taking and clearing Modena, then pushing on into Parma, about sixty miles west of Bologna. Germans continued to drift out of the mountains and into the towns all along the highway, requiring brisk fighting to drive them out. A history of Company L describes it thus:

“The Po Valley was aflame…rolls of powder smoke belching from thousands of weapons darkened the sky on that otherwise bright day. The resistance was sharp all along the way…”

The 135th continued to fight west along Highway 9, achieving their assigned objective of , a strategic town on the Po River over a hundred miles west of Bologna. It had taken eight bloody months to advance from Florence to the approaches of Mount Belmonte. In less than two weeks the 135thhad moved over a hundred-ten miles through enemy territory in late April. In the afternoon of April 26th, Company L was ordered to Caorso, some ten miles from Piacenza. It had been reported to be a German stronghold. The Company was advised by friendly civilians that the Germans had moved out. Our men proceeded cautiously into the town square where a crowd of civilians including the mayor greeted them. Suddenly, enemy burp guns opened up. The locals dashed wildly for safety while Company L sought cover and returned fire with BARs, machineguns and small arms. It became all too obvious that German elements remained. Outnumbered, the men of Company L sought refuge wherever they could. There were casualties and a few of our soldiers were taken captive. German troops, retreating from the mountains, continued to pour into the village. Night fell and enemy tanks appeared. The Americans were by then scattered, and in the darkness, it was difficult to tell friend from foe. The Germans hurled hand grenades and directed tank rounds into the buildings where our forces, increasingly outmanned, were hunkered down. Eventually an estimated six thousand Germans had arrived, a considerable force easily outnumbering the entire nearby 3rd Battalion, not to mention little Company L.

American reinforcements soon arrived, however, and the tide turned. Most of the Germans escaped north across the Po, but many were killed in Caorso and seven hundred were captured. Our casualties, while much lighter, were still a painful reminder of the unpredictable fortunes of war.

By April 27th, only two weeks after the breakout over Mount Belmonte had begun, the battle for Highway 9 and the Po River south of the Apennines had been won. A total of three German divisions had been captured. Many others had escaped north across the river and were fleeing toward the Alps. The next day, on April 28, the entire Red Bull Division was ordered to move north across the Po River to aid in sealing the Alpine passes. Every conceivable vehicle was pressed into service. Soldiers clung to the hoods, fenders and bumpers of trucks. The 135th sped back to Modena then north, breaching the Po River on a hastily made pontoon bridge.

[image error]Orders were changed mid-route, and the unit raced toward , fifty miles north of Caorso where they had been ambushed. Upon arrival, orders were almost immediately issued to proceed to Milan, the largest industrial and commercial center in Italy. News soon came that the Italian resistance had liberated the city, and captured then brutally killed Mussolini, the Fascist dictator and ally of Hitler who had led the nation to ruin. His nude, battered body was infamously hung naked from a balcony in the city square, a final act of violent defiance.

[image error]Overall, our combined forces spread across the valley and sped along the well-developed road network in the Po. The Germans in turn wheeled, dodged and raced with frantic zeal. Their units fragmented. Some were simply left behind to be mopped up later by the Allies. Prisoners began to pour in, some finding and surrendering to American units on their own initiative. Others continued futile resistance. According to eye witnesses, it was an amazing spectacle, colorful and exciting. The demeanor of the German prisoners was one of utter dejection, defeat and hopelessness.

[image error]With Milan pacified, the 135th was ordered to take and capture the German 75th Corps. Upon making contact, that entire corps, tens of thousands of men, surrendered en masse to the Red Bull 34th Division. In a twist of irony, the German 34thDivision surrendered to my father’s division of the same name. Our forces were given the massive task of rounding up and taking custody of the POWs.

It was about this time that my father experienced the most dangerous and terrifying encounter of his time in Italy. A few small German units continued to resist. They either had not gotten or refused to heed the orders to surrender. My father and several fellow soldiers were manning an outpost set up in a small stone farmhouse on a little hilltop. They were spotted by a rogue group of Germans, who immediately attacked their position. A fierce fight followed. With superior numbers, the enemy stormed the house and burst into the tiny interior, weapons firing. Dad found himself in the same room with the German soldier who had knocked the door down and rushed in shooting. My father instinctively fired his weapon, his BAR, from the hip in a reflexive act of self-preservation. Both men shooting at each other, the German boy collapsed and died before Dad’s eyes. My father was unscathed. With the enemy surrendering and the war virtually over, he had come closer to death, saved only by chance, than at any other time during his combat. My father was incapable of violent vengeance. But in an odd way, it seems a fitting counterbalance to the tragic death of Woody, his young ward, also before his very eyes. Fate has a way of evening scores.

Ultimately, we were able to get behind the retreating Germans in this fashion, and bring things to a whimpering end. On May 2nd, the Germans signed a surrender of all forces in Italy, and the war there was over. One observer reported

“…the final surrender was received by our troops with a strange calm almost amounting to complacency. There was neither shouting nor cheering, no celebration was held. Perhaps it was because the men had foreseen the inevitability of the enemy’s collapse. Or perhaps our battle-weary soldiers were just too exhausted…”

It is estimated that between September, 1943 and April, 1945, 70,000 Allied and 150,000 German soldiers died in Italy. The total number of Allied casualties including those wounded was about 320,000, and the German figure (excluding those involved in the final surrender) was over 330,000.

And so the Battle of the Po and all hostilities in Italy came to an end.

_________________________________

Next: "COMING HOME", the conclusion of One Soldier's Story

May 1, 2021

BREAKTHROUGH!

BREAKTHROUGH INTO THE VALLEY OF THE PO

April – June 1945

Excerpted fromOne Soldier's Story by John Bascom

April in the Apennines arrived to much improved spring weather and great anticipation among Allied troops. March had been marked by the usual patrols, skirmishes and shelling. It had been a month of holding the line and preparation. My father had been hospitalized in Livorno for much of the time, but returned to his unit in April.

The officers of the Allied Armies were busy planning the great offensive that would, once and for all, crush the Germans in Italy. Back in Germany proper, American forces had breached the Rhine River at Remagen, and a metaphorical floodgate had opened allowing the Allies to pour into central Germany. The Russians were on the doorstep to the east. German resistance was crumbling; hundreds of thousands of prisoners had been taken, Hitler was hiding underground in Berlin, and Nazi officials were already fleeing the country. Many had surrendered or committed suicide. The end was in sight.

Conditions and morale among the German officers and men continuing to resist in Italy must have been abysmal. Still, the Gothic Line stood strong, stretching across the northern Apennines from coast to coast in a two-hundred-mile line from the Ligurian Sea in the Mediterranean west to Rimini on the Adriatic. Their line was opposed along it’s entire length by the Allies, over one million men strong. Better equipped and motivated, our forces were ready for the great and final assault to begin.

British forces along the Adriatic and the American 92ndon the west coast began attacks northward in early April. In addition to pushing the Germans off the line in those areas, it was designed to pressure them into pulling troops from, or at the very least prevent them from reinforcing their forces in the center of the line south of Bologna. It was there, in the center, that General Clark had planned the final, killing blow. Both coastal attacks met with good results and fulfilled their objective of pinning the Germans down there.

The Red Bull and other divisions of II Corps continued to be positioned between Florence and Bologna astride north-running Route 65 and its parallel byways. On April 14, with weather fair and troops ready, the great assault commenced. It was marked by an earth-shaking roar of artillery, followed by air attacks from thousands of bombers dumping countless tons of high explosive and antipersonnel munitions. Then came the screaming, swooping fighter planes firing machineguns and rockets. The massive explosions continued throughout the day.

The air and artillery attacks were followed by a full-force assault of infantry. The squad and platoon-sized probes a hill or village at a time were a thing of the past. With improved roads, tanks accompanied our foot soldiers. Artillery and air continued to prepare their advance. Once again, the 135th Regiment found itself positioned south of and ready to attack Mount Belmonte one last time. They moved out on command to take the eastern flanks and hills adjacent to the mountain.

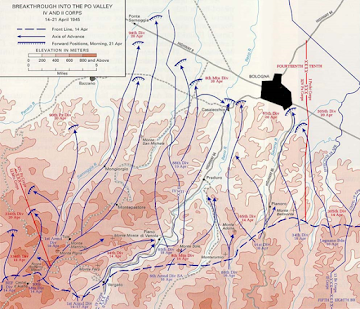

Spring attack to break the Gothic Line. Position and planned path of the 34th Division shown right center. Mount Belmonte is shown immediately above and slightly left of the Division’s starting position

On the eastern Adriatic Coast, the British had achieved a breakthrough and surged across the Gothic Line defenses into the Po Valley. Swinging westward, they threated to continue north behind German lines, trapping the entire German army between them and the Americans charging northward.

At first German resistance to the advance of the 135thRegiment was as fierce and stubborn as before. Casualties ran high on both sides. But the enemy could not negate the months of Allied preparation, stockpiling ammunition, and our resolve to end things once and for all. And above all, the devastating air and artillery bombardments. According to military historians Jay Roth and Judith Nichols, German prisoners

“…revealed the ordeal that had been theirs during two terrible days of air and artillery preparation. Many were still trembling when captured: others stared with vacant eyes, numbed and speechless. Still others told of the hell they had endured.”

Realizing their precarious position, the German defenses in the Apennines began to collapse. The Red Bull Division and its sister II Corps units surged north, taking objective after objective. The previously impregnable Mount Belmonte was quickly overwhelmed. German units, all hopes of successfully resisting dashed, began a scrambling retreat out of the Apennines and across the Po River, which defined the southern edge of the Po Valley. Their aim was to form a secondary defensive line north of the Po River and then retreat further north in an orderly fashion until the refuge of the Alps could be achieved.

Bologna is an ancient and historic city located about sixty miles north of Tuscan Florence. It was the prize the Red Bull Division struggled to attain in the previous eight, bloody and frustrating months. Bologna has a rich Renaissance heritage and hosts many historic and architecturally important sites.

A teaming city—one of Italy’s largest—it is home to over a million people. The Piazza Maggiore is the sprawling square with lovely arched colonnades and medieval buildings of classic beauty. There sits the Fountain of Neptune and the Basilica di San Petronio. Graceful towers adorn the city including one that is leaning, reminiscent of the famous tower in coastal Pisa. Bologna boasts the world’s oldest university, the 1088 AD University of Bologna.

But the beauty and historical significance were not the reasons it was coveted by both the Allies and Germans. It sits squarely in the west – east center of the entrance to the Po Valley, directly in the middle of the Nazi’s defensive forces. Immediately to the city’s north lies the west – east oriented Po River, a perfect defensive barrier for the enemy’s retreating armies. Taking Bologna and the river were the keys to shattering German lines and opening the Po Valley to attack by our troops, tanks and aircraft.

As the grand assault in the quest for Bologna began in mid-April, the 135th Regiment deployed on the right flank of II Corps. While resistance as always was brisk, they quickly took their objectives around Mount Belmonte and pushed forward east of and finally astride Route 65. After several days of fighting the battered and retreating Germans, the 135thentered Bologna, their original target at the outset of the Gothic Line campaign back in September 1944. They and a sister Polish unit fighting with the Allies were the first to gain the prize. It had taken less than a week to advance the final twelve miles to the city, something that had not been accomplished in months of earlier fighting. The German’s had already withdrawn north across the Po River in an attempt to establish their next line of defense as planned. The mission of the 135th was to secure the city and remove any mines or booby traps left by the enemy. Other Allied units along the entire length of the Gothic Line were making good progress as well.

The Red Bull’s stay in Bologna would be short lived. After securing the city, its defense was handed over to other units. The Division had bigger fish to fry.

___________________________

Next Installment: The Allies defeat the Nazis in a frantic series of battles ranging across the Po Valley and into the far corners of Northern Italy, while our soldier comes closer to death than ever before

April 16, 2021

Holding the Line in the Apennines

Excerpted from

One Soldier's Story

by John Bascom

HOLDING THE LINE

January – April 1945

By early January 1945 both sides in Italy had ceased large-scale military operations. In addition to the winter weather, five British Eighth Army divisions that had been attacking the Gothic Line to the east of our 5th Army had been moved to northern Europe. This continuing drain of people and equipment added to the growing Allied shortages in Italy, and made defeating the entrenched and tenacious Germans more difficult than ever. The generals decided to go on the defensive and use the winter months to prepare for new offensive operations scheduled for April 1945, when the weather would be better and resupply and reinforcements would have, at least to a small degree, occurred. Despite four months of planning, bloody offensives, and staggering casualties, Allied units came to rest on a defensive line in a position that had changed very little since early autumn.

Troops of the Red Bull Division were set to work constructing our own defensive winter line south of the Po Valley. Since September, their assaults had carried them nearly fifty hard-fought miles up Route 65, stopping just a dozen or so miles south of Bologna and the Po. The line ran east to west across Route 65, just south of the as yet unconquered section of the German Gothic Line near Mount Belmonte. The men of the 34th constructed bunkers, machine gun pits, artillery emplacements, barbed wire, mine fields and other obstacles to a German attack. Heavy snow made construction difficult, and at times totally covered and concealed prepared positions, requiring them to be marked with poles so they could be found by our soldiers later.

Troops of the Red Bull Division were set to work constructing our own defensive winter line south of the Po Valley. Since September, their assaults had carried them nearly fifty hard-fought miles up Route 65, stopping just a dozen or so miles south of Bologna and the Po. The line ran east to west across Route 65, just south of the as yet unconquered section of the German Gothic Line near Mount Belmonte. The men of the 34th constructed bunkers, machine gun pits, artillery emplacements, barbed wire, mine fields and other obstacles to a German attack. Heavy snow made construction difficult, and at times totally covered and concealed prepared positions, requiring them to be marked with poles so they could be found by our soldiers later.

Neither side could nor wanted to launch a major offensive. Still, patrols were sent out regularly to assess the enemy’s position and intentions, which resulted in frequent clashes. Any enemy movements were struck with artillery and machine guns, and they likewise struck us. On several occasions, based on information from local civilians who despised the Germans, enemy agents dressed in American uniforms seeking to infiltrate our positions were captured by Dad’s Company L. The 135th Regiment and its 3rd Battalion were moved to the very front of our lines near Mount Belmonte, which had previously been the site of the fierce battles that had failed to dislodge the Germans. Conditions were slippery, which made vehicle traffic up the icy mountain lanes virtually impossible. Our men were forced to march for long distances in blinding snow storms and through partially frozen slush when required to change locations. Conditions for the men entrenched on Mount Belmonte were grueling. Trench foot became epidemic in Company L and its sister companies of the 135th.

Firefights continued to break out. On January 9th, four German soldiers approached Company L and indicated they wanted to surrender. However, the ruse turned into a fierce clash and three of the four Germans were killed with the fourth captured. The next day a detachment of sixty enemy was spotted. When they took shelter in a small building, they were shelled by our artillery. The building was completely destroyed. A mortar duel erupted, and two men from Company L were

wounded. Soon after, a five-man enemy contingent attempted to raid the company. Four were killed by our troops. For the remainder of January, these kinds of scattered encounters continued. Company L was tasked with setting up ambush patrols closer to German lines. At times, the dug-in troops received coordinated, intense artillery bombardments augmented by bombing from Germany’s few remaining planes in the theater. My father wrote that at one point during this winter deployment on the front, he spent thirty miserable, consecutive days living in the same cold, wet foxhole.

Heavy patrolling continued through February. In early February, several more aggressive and organized raids were launched against German positions with limited results. Dad related that they had been eating rations from cans for nearly a month, when a cow was spotted by his patrol. It was dispatched by their M-1s, and the men dined on steaks for several days. By the middle of the month, the 135th was pulled briefly into reserve, then quickly redeployed to another nearby sector. What had become the customary patrols, shelling and intermittent gunfights continued throughout the balance of the month.

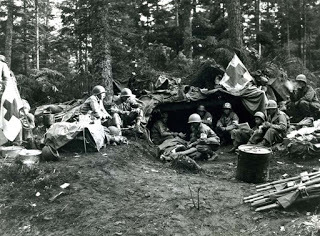

My father had earlier in the campaign been twice wounded by shrapnel during enemy artillery bombardments. Fortunately, the injuries were minor and he was

My father had earlier in the campaign been twice wounded by shrapnel during enemy artillery bombardments. Fortunately, the injuries were minor and he was

treated at the nearby field medical facility, then quickly returned to his unit. However, in late February Dad was taken ill with jaundice and hepatitis, probably from coming into contact with contaminated water. Soldiers in the field sometimes washed their hands or faces in streams or pools, and it was impossible to know what pollutants lurked just upstream. The men of course had to relieve themselves in the field. Also, food occasionally obtained from local villages was suspect.

Since hepatitis is infectious and disease had become a problem among the troops, he was evacuated to a military hospital in Livorno on the Mediterranean coast, southwest of Florence and well behind the action. He not only enjoyed a clean, comfortable bed, but the weather was also considerably warmer. Despite being ill, it must have been a welcome break from six straight months of fighting, shelling, death and misery. After several weeks of treatment and convalescence, he recovered and returned to his unit in the Apennines to continue the fight.

February 26, 2021

ONE SOLDIER’S STORY: THE BATTLE CONTINUES

The Wartime Experience of John Gay Bascom

by John Bascom

“The Attack that Wasn’t”

November – December 1944

The onset of November saw the 34th Division, it’s constituent and sister units on a broad defensive east – west line across the northern Apennines centered on Route 65. The assault had stalled due to a combination of German tenacity, well planned and constructed fortifications, horrible weather even by the standards of the Apennines, and a serious depletion of men, equipment and supplies.

The Allies main thrust against the Germans was the invasion of northern Europe through France at Normandy in June 1944. By November, the main European assault had driven the Germans from France and Belgium back into the motherland. American troops had approached the western German border and were threatening the Rhine. Berlin would then be within striking distance. The thrust into Germany was receiving top priority for men and equipment. Our forces in northern Italy were a neglected stepchild, contributing to the shortages that made cracking the Gothic Line increasingly difficult.

The Germans were not fairing well either. Their homeland had been subjected to relentless strategic bombing for four years. Thousands of huge, heavily laden Allied planes rained hundreds of tons of incendiary and high explosive bombs on German cities daily. Smaller aircraft swooped in on their military concentrations, strafing, bombing and launching air-to-ground rockets. The Allies had established near complete air superiority and had largely destroyed the German Air Force and Navy. Industrial capacity was crippled, German equipment had been decimated on a wholesale basis, and countless thousands of Nazi soldiers had been killed, wounded or captured. And the Russians had turned the tide and were advancing rapidly on Germany from the east. The Germans’ main priority was protecting the homeland, and Italy was an afterthought. As such, their men, equipment and supplies were dwindling in Italy as well, more so perhaps than those of the Allies.

For both sides the battle in Italy was seen as a secondary front designed to frustrate the enemy. The Allies sought to pin German forces down to prevent their use in the main defense of their country further north in Europe. The Germans realized they could not defeat the Allies in Italy, who enjoyed a huge advantage in manpower and materials. Their objective was to stall our advance, keep our forces from reinforcing the assault that was proceeding well across northern Europe, and only secondarily to protect their southern borders. German leadership in Italy had long wanted to fall back into the more defensible Swiss and Austrian Alps to avoid further carnage. Italy itself was seen as being of little strategic importance. But Hitler had ordered a “no retreat” policy, so the Germans fought on across the Gothic Line.

General Clark’s plan to crush the Gothic Line and pour into the Po Valley by the end of October had failed. The infamous Apennine winter would soon make maneuvering for an attack virtually impossible. Against this backdrop, a renewed assault toward the Po was ordered to begin in November before the worst of the winter weather could set in.

In early November, Dad’s 3rd Battalion was in reserve in Montecatini. Many of the men were billeted in hotels or other buildings in the town. They were finally able to shower, relax, socialize and even attend a few movies. There was mail to and from home. The commanding generals visited the area to commend troops and award medals. Training was also conducted and fresh troops and equipment arrived.

The R&R did not last long. General Clark was still committed to reaching the Po before winter. For the time being, the II Corps’ line deep in the northern reaches of the German Gothic Line was still held by our troops. November saw the opportunity to improve our positions, destroy enemy guns and fortifications with heavy artillery, and conduct reconnaissance and harassing raids preparatory to a major assault being planned for December.

By November 11th, Dad’s 135th Regiment moved back onto the front lines to Barbarola, a tiny village astride Route 65. It was only two miles south of recently taken Livergnano and eighteen miles south of the Regiments’ main objective, Bologna. To the north were the commanding and strategically important heights of Mount Belmonte. They were ordered to conduct two patrols nightly and target known enemy positions for artillery and mortar fire.

Mount Belmonte was a rugged, sprawling area of deep gorges, steep cliffs, and narrow, muddy trails. Located just north of the tiny village of Zena and lying only ten miles south of the Bologna objective, the mountain was strategically positioned. It dominated the approaches the 34th Division would have to use if it were to seize Bologna. It would have to be taken before a breakthrough in the center of the Gothic Line could be achieved. As such, my father’s 135thRegiment was ordered to attack it.

Mount Belmonte was more than a simple military objective. It was a strong point, a lynchpin in the German Gothic Line. To say it was heavily fortified or defended would be a vast understatement. A huge, mountainous area rather than a single peak, it was awash in enemy entrenchments, bunkers, defensive barriers and crack German troops. Moving onto its face, patrolling the area was difficult and dangerous. Our units regularly received machine gun and mortar fire. Uncharacteristically clear days occasionally allowed our aircraft to effectively bomb and strafe enemy positions to our front. For its part, the enemy fired tank, artillery and machine gun rounds into our positions with regularity. They, too, continuously patrolled, assaulted our positions or counterattacked those they had recently lost. Once our units gained a ridge or prominence, they immediately made preparations to repel the almost certain counterattacks. All the while, our patrols constantly met and exchanged fire with those of the Germans.

Aggressive patrolling, firefights, assaults and ambushes continued through mid-November. On the 18th of November, Company L and other elements of the 135th were relocated to the village of Sassi, where they continued to receive enemy artillery fire. Mount Belmonte remained firmly in German hands. But my father would revisit it again and again before it finally fell.

On November 20th, they moved farther back to Barbarola south of Livergnano, where they had originally been located earlier in November. Two days later they fell back behind the front lines to Barberino for some well needed rest after being encamped in the field for most of the month. By the evening of the 25th, the entire 135th Regiment was in reserve at Barberino. Training resumed and a few one day passes to Florence were granted. General Bolte, commanding officer of the entire 34th Division, presented the Combat Infantry Award to the 135th Regiment in recognition of their distinguished performance in the Gothic Line campaign.

Commanding generals were planning a new, intensified assault and the rest at Barberino was not to last long. Company L was dispatched once again to Barbarola and then marched forward to Sadurano, situated east of Route 65 about two miles from Livergnano. The weather had remained cool and rainy all through November, and the area where they were ordered to encamp in tents was covered in nearly a foot of water and slush. Fortunately for Company L, it was soon ordered to move out and reinforce the sister 133rd Regiment near the village of Quercito where living conditions were slightly more tolerable. Another assault on stubborn Mount Belmonte, still partially occupied by the Germans even after two weeks of bloody attacks, was scheduled to begin in a few days.

A flock of twenty-five sheep was obtained to probe for mine fields. A German deserter was captured who reported that some twenty agents had been sent to infiltrate the American line including six women. Our combat patrols increasingly received machine gun, artillery and mortar fire. Heavy rain and enemy fire were delaying any new major attack. Still, unit officers were meeting regularly to discuss plans for the long-awaited main assault. The Germans, perhaps sensing an attack, increased patrolling and shelling activities. The men were in high anticipation.

Still, rain and fog delayed action. On the occasional clear day, allied planes attacked enemy positions to our front. Some minor repositioning occurred and aggressive patrolling continued. About December 16th, the 3rd Battalion was ordered to return to Barberino, marching cross country through rain and thick mud. There the 135th was reinforced with two additional battalions from a sister unit, bring the total to five battalions.

Winter weather was beginning to arrive. Snow and ice covered the hilltops and roads. The men were issued cold weather gear, including white “snow parkas” for some. A Christmas dinner was served for those in reserve including the 135th Regiment, and church services were available.

Having been thwarted in efforts to attack earlier in December, the American senior commanders had been planning the long-delayed offensive against the length of the entire coast-to-coast Gothic Line to begin on Christmas Eve. The goal was to surprise the Germans and finally break through before the worst of the winter weather. It would be the last chance before spring. The date for the attack had been continuously postponed due primarily weather, and Christmas would be the latest it could be launched.

The Germans, however, had learned of the preparations, and planned their own preemptive assault before the Americans could attack. They initiated a major, multi-division thrust southward along the Mediterranean coast against the recently arrived American 92nd Division, which the Germans viewed as particularly vulnerable. The enemy’s aim was not to defeat the Allied armies there, but to create a major diversion designed to draw Allied reinforcements from the center of the Gothic Line to the coast in defense of the 92nd. In in so doing, it would spoil the assault on the center of their lines. The strategy worked. Allied commanders became aware of the Germans’ plan a few days before it was to begin, and units were shifted eastward to block the German onslaught. Elements of the 135 Regiment were moved west near Lucca in the 92ndDivision’s sector near the coast to help them stop the Germans.

Also significant was the Germans’ pre-Christmas thrust into Allied lines in Belgium, the famous Battle of the Bulge. It met with some initial success, although it was ultimately turned back, in large part by the counterattack of Patton’s armored forces at Bastogne. Nonetheless, the Allies were alerted to the fact that the Germans did not intend to go quietly into the night. All this increased the anxiety of commanders further south in Italy.

Ultimately, the German assault against the coastal 92nd Division was halted, but equipment and forces had been reduced and realigned in the II Corps along the Route 65 sector. By the time the threat had passed, the weather had taken a bad turn and it was too late into winter for the planned breakthrough assault to Bologna to occur any time soon. Any such action against the center of the Gothic Line would have to wait until spring.

___________________________________

Next Installment: Holding on in the Winter; Cold, Snow, Slush, and Sickness

February 17, 2021

ONE SOLDIER’S STORY: FIRST COMBAT

The Wartime Experience of John Gay Bascom

by John BascomFIRST CONTACT WITH THE GOTHIC LINE

August-September 1944

Castel Fiorentino today is a busy town nestled in the iconic hills of Tuscany, Italy. Located an hour southwest of Florence and halfway to coastal Pisa and its leaning tower, the scenic Tuscan hills surrounding the town are draped in vineyards. The vicinity is known for marvelous Chianti wine and a flavorful, mellow Brunello. The town dates from 1100 A.D. in the Middle Ages, and much later came to enjoy a rich Renaissance heritage. Stone houses, winding lanes, quaint public squares, hilltop churches and beautiful vistas make it a popular, off the beaten path tourist destination. When my father arrived in August, 1944 it was, of course, much smaller, but still peaceful and beautiful. The scene of bygone struggles for land and power that have forever characterized Italy, no battles had touched it in the modern epic. He must have been charmed and reassured. But it would be a portal to the coming eight months of chaos, fear and blood that would be the Battle of the Northern Apennines.

The 135th Regiment, Red Bull Division was in reserve in Castel Fiorentino. Dad dutifully reported there as a replacement in mid-August following a weeks-long voyage in a cramped troop ship, then a truck ride inland. Following distinguished battle performance in North Africa, and then in Italy before Dad joined them, his unit, the 135th, had landed as part of the Salerno invasion far down the Italian boot in September, 1943. They had viciously fought north through Anzio, Rome and Livorno before pausing in Castel Fiorentino for training and replacements in the summer of 1944. Shortly after Dad’s arrival, a major line of defense north of Rome for the retreating Germans, the Arno Line, had been broken and the historic city of Florence was finally in American hands. Dad was part of a large compliment of desperately needed replacements for the thousands of dead, missing, wounded and captured.

He was assigned as a rifleman in the 3rd Battalion, 135th Regiment, Company L. Oral family history is that he was part of a two-man BAR or Browning Automatic Rifle light machine gun team. One man would carry and fire the machine gun while the second supported him by carrying the bipod and the considerable load of ammunition required, while providing covering support with his M-1 rifle. Smaller and lighter than a heavy machinegun designed to be operated from a prepared emplacement, the BAR could be fired from the ground while supported by its bipod or from the shoulder. Its portability and versatility made it suitable in both in assaults and for defense and as such, a staple in infantry platoons. Dad would not have to wait long for more action to begin.

The Regiment moved to Galluzzo on the southern outskirts of Florence on the night of September 4th, and on 8th through the city to a northwesterly suburb. This was preparatory to a carefully planned, multi-corps assault on the feared German Gothic Line, which spread west to east across the entire Italian boot along the imposing Apennine Mountain range. Its heights ranged from three hundred feet to over four thousand, with its highest peak over seven thousand feet.

The Allied strategy was to mount a coordinated northward attack along the entire Gothic Line, ultimately forcing the Germans backward and out of the Apennines. The II Corps, comprised of four divisions including the Red Bulls, was to press the attack north through the center of the Gothic Line. They planned to completely break through it and out of the mountains into the Po Valley before winter set in. The Apennines Mountain Range ended on its northern face in the broad, deep and rolling Po Valley which stretched from the Milan in the west of Italy to the Adriatic coast in the east. There, the decimated Germans would lack the advantage of the rugged, concealing Apennine heights and be easy game for American infantry, tanks, artillery and planes. My father’s unit, the huge fifteen-thousand-man Red Bull Division, was tasked with supporting the massive effort by attacking northward from Florence. Other divisions attacked simultaneously along the entire Gothic Line, from coast to coast. These would be the first penetrations north of the recently fallen Arno Line. The Germans knew their next line of defense to the north, the infamous Gothic Line, was essentially their last stand. They committed hundreds of thousands of men, artillery and equipment to defending it from carefully prepared and heavily fortified mountain positions.

The Red Bull’s attack path was north generally along the western flank of Route 65 which ran some sixty winding, hilly miles through the Apennines from Florence to Bologna and the entrance to the Po Valley. The attack corridor extended miles to the east and west of the main road to include barely accessible villages and fortifications occupied by German troops in the surrounding mountains. Route 65 transited a tangle of mountain roads, often narrow, steep and muddy, that wound up, down and through the Apennines. Some were little more than trails unsuitable for vehicles. These mountain lanes held countless villages, many perched on forested hilltops or mountainsides, some with a population of only a few dozen souls. Their ancient stone houses, walls and turrets provided perfect killing sites for the Germans. All these would have to be taken inch by inch by the soldiers of the Red Bull Division to assure the success of the larger II Corps assault. It was to take eight bloody months, countless thousands of American casualties, setbacks and failures, before the objective of Bologna and the Po Valley would be finally achieved.

Having crossed the Arno River in Florence and for the first time formally advancing through the Arno Line, on September 11th they proceeded to an assembly area near , north of Florence on the road to Bologna, the ultimate objective. Along the way they were subjected to enemy artillery fire, sniping and firefights. On the next day, the 2nd and 3rd (Dad’s) Battalions went forward, passing through its sister regiment, the 168th Infantry. It was a day of severe losses for the 3rd Battalion. As the unit's command group moved into the assembly area, a German "Schu" minefield was encountered and the battalion commander, Lt. Col. Harry Y. McSween, was seriously injured by a mine. More mines exploded in the attempts to aid him and others were injured including several more officers. The losses in battalion leadership on the eve of battle were felt very keenly because of the experience and ability of these officers. These actions marked the beginning of the North Apennines Campaign and the assault on the deadly German Gothic Line.

The method of attack was to advance with combat patrols to identify German positions which could be occupied or overrun by larger concentrations of American troops that followed behind the patrols. To assure the integrity of the assault it was critical that all high points from which Germans could fire down on advancing Americans be taken. These engagements involved fierce firefights and seizing ground ridge by ridge and town by town from tenacious Germans skilled in the art of mountain defense. German doctrine was to counterattack almost immediately after having been dislodged, resulting in violent battles to hold ground only recently taken.

The battalions of the 135th were moving forward on September 12th toward about twenty-five miles north of Florence in the face of stiff opposition. Enemy artillery fire was quite heavy, but this was countered effectively by fire from our own supporting artillery. On September 13th it was learned from prisoners that the 135th Regiment had encountered the outposts of the Gothic Line. It was learned, too, that this sector was defended by crack units of the 4th German Paratroop Division.

In one instance, Company L, Dad’s company, ran into pillboxes at the base of Hill 568, a highpoint fortified by the enemy. Hand grenades were exchanged at close range. All the companies were able to keep pressing on but, the 3rd Battalion ran into the greatest resistance. Artillery on both sides was expending a large amount of ammunition. On September 14th, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions attacked. The enemy used a great amount of automatic weapons fire. The 1st Battalion passed through the 2nd, and the 3rd Battalion opened a second assault on important Hill 671 where the enemy had managed to hold out the previous day. Casualties ran high on both sides. Company I, for instance, alone lost 18 men wounded and 5 killed.

Dad’s 3rd Battalion was not to be denied its objective and advanced under a rolling artillery barrage. The advance north continued and the battalion took part in the attack on the heavily fortified and strategically important town of , located just off of Highway 65. The fighting to take the village, nestled among cliffs on a mountainside, was fierce. In one group of houses at Livergnano a hand-to-hand fight developed with extensive use of grenades. This engagement was won primarily through initiative and courage. Inspired by heroic leadership, the battalion moved in to clear out the strongpoint. A posthumous award of the Congressional Medal of Honor was made to Lt. Wigle for his heroism during that battle.

Hill 671 was completely occupied by the 135th the next day. The German paratroopers had displayed their traditional stubborn resistance and had made good use of extensive mine fields, barbed wire, concrete emplacements and dugouts. It required direct hits from artillery of heavy caliber to knock out many of the emplacements. With the capture of this mountain position, the Gothic Line had been penetrated and the 135th Regiment was now meeting the main defenses. Before the sister 1st Battalion jumped off in the direction of Mangona a lengthy artillery barrage, including heavy guns, was laid down with excellent results. The enemy was also employing heavy artillery on our frontline troops.

The Gothic Line defenses were legendary. Rather than a single line, it was a series of parallel defensive positions allowing the Germans to fall back when pressed to other prepared fortifications, forming a defense in depth all the way to the Po Valley. Prisoners of war had pointed out and stressed its formidable nature. They contended that this line would prevent the Allies from getting into the Po Valley and added that orders had been received from Hitler that the drive northward must be stopped at this position. All available intelligence indicated that the major undertaking on hand would require a maximum of skill, coordination, and aggressiveness in order to break the line. The Gothic Line positions in the vicinity of the Futa Pass, which the 135th Regiment was attacking then flanking from the west, were as staunch and formidable as had been feared.

The selection by the Germans of commanding heights with tortuous approaches had been scientifically welded into a defense line with all the expertness acquired by the enemy high command throughout its long defensive campaign in Italy. To increase the effectiveness of the forbidding terrain, the Germans had commandeered, through organization "Todt", Italian civilian slave labor to erect coordinated positions of steel and concrete pillboxes and gun locations. The mountains presented problems of supply to the 135th Regiment, and mule pack trains often offered the only means of transporting the much-needed food and ammunition. Rations were often delayed because mules could not climb steep cliffs; casualties had to be hand-carried or born by mules where possible to the rear.

One veteran remembers the Gothic Line this way: