Eric Bosse's Blog

September 11, 2012

Free Kindling: Fahrenheit Four-Fifty-FUN!

We're giving away the Kindle edition of my book for free this Saturday! Please download it and spread the word far and wide. Many thanks!

Here's the link to the Facebook event page (not necessary to get a free copy, just a way to promote freedom!): https://www.facebook.com/events/18025...

And here's the book's Kindle page: http://www.amazon.com/dp/B0098D2CPQ

Here's the link to the Facebook event page (not necessary to get a free copy, just a way to promote freedom!): https://www.facebook.com/events/18025...

And here's the book's Kindle page: http://www.amazon.com/dp/B0098D2CPQ

Published on September 11, 2012 18:59

•

Tags:

flash, flash-fictions, free, gender, giveaway, kindle, literary, magnificent-mistakes, short-short-stories, short-stories

May 1, 2012

Win a Free Copy of Magnificent Mistakes

If you're on Facebook and you share this image, you'll be entered in Ravenna Press's drawing for a free, signed copy of my book: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fb...

Published on May 01, 2012 17:26

•

Tags:

book, giveaway, magnificent-mistakes

February 14, 2012

Enjoying the Silence

When you write a book, publish a book, sell a book, and wait for the book to start selling itself, you know what doesn't happen automatically? Reviews. That's what.

My small publisher and I have sent out review copies of Magnificent Mistakes to various publications, and thus far we have landed precisely one review. Four months: one published review. No complaints on the review itself. It's very kind.

But where did the other copies go? Did anyone look at them? I just don't know. It's all kind of mysterious, this business. I'm not taking it personally--not at all--but I would like to get the book in front of a few more eyes before it dies.

Ah well. Heavy sigh. Chirp chirp. All that.

Meanwhile, the novel gestates.

-----

PS If you want a signed (or unsigned, or inscribed) copy, I'll sell you one, cheap. I've got a boxful, and one is anxious to meet you. Drop me a line.

My small publisher and I have sent out review copies of Magnificent Mistakes to various publications, and thus far we have landed precisely one review. Four months: one published review. No complaints on the review itself. It's very kind.

But where did the other copies go? Did anyone look at them? I just don't know. It's all kind of mysterious, this business. I'm not taking it personally--not at all--but I would like to get the book in front of a few more eyes before it dies.

Ah well. Heavy sigh. Chirp chirp. All that.

Meanwhile, the novel gestates.

-----

PS If you want a signed (or unsigned, or inscribed) copy, I'll sell you one, cheap. I've got a boxful, and one is anxious to meet you. Drop me a line.

Published on February 14, 2012 19:13

January 15, 2012

Summoning the Writing Angels

As prelude to teaching a new course with the same title, I am rereading Annie Dillard's

The Writing Life

this weekend. It has been at least fourteen years since I last read it, possibly twenty, and I had forgotten how this book bristles with metaphor. It can be overwhelming, at times. But the advice is priceless and abundant in these pages. Consider this:

(Blogger would not let me properly break the paragraphs therein. Sorry. Too lazy or busy to figure this one out, so I lumped them all together.)

I am also re-watching Jane Campion's brilliant film adaptation of Janet Frame's autobiographies, An Angel at My Table. I feel richer today than I felt on Friday, by far. My next big challenge will be to figure out how to manage my larger-than-usual course load this semester in a way that allows for time to write. No, that sounds too passive. My challenge will be to carve out time to write from my larger-than-usual course load. Nope. Still not quite right. Here: My challenge will be to carve out time for teaching three courses, instead of the normal two, from all the time I am going to devote to writing.

In the dark days of their careers, writers have to be their own cheerleaders.

To comfort friends discouraged by their writing pace, you could offer them this: It takes years to write a book--between two and ten years. Less is so rare as to be statistically insignificant. One American writer has written a dozen major books over six decades. He wrote one of those books, a perfect novel, in three months. He speaks of it, still, with awe, almost whispering. Who wants to offend the spirit that hands out such books? Faulkner wrote As I Lay Dying in six weeks; he claimed to have knocked it off in his spare time from a twelve-hour-a-day job performing manual labor. There are other examples from other continents and centuries, just as albinos, assassins, saints, big people, and little people show up from time to time in large populations. Out of a human population on earth of four and a half billion [as of 1989], perhaps twenty people can write a serious book in a year. Some people lift cars, too. Some people enter week-long sled-dog races, go over Niagara Falls in barrels, fly planes through the Arc de Triomphe. Some people feel no pain in childbirth. Some people eat cars. There is no call to take human extremes as norms.Full stop.

(Blogger would not let me properly break the paragraphs therein. Sorry. Too lazy or busy to figure this one out, so I lumped them all together.)

I am also re-watching Jane Campion's brilliant film adaptation of Janet Frame's autobiographies, An Angel at My Table. I feel richer today than I felt on Friday, by far. My next big challenge will be to figure out how to manage my larger-than-usual course load this semester in a way that allows for time to write. No, that sounds too passive. My challenge will be to carve out time to write from my larger-than-usual course load. Nope. Still not quite right. Here: My challenge will be to carve out time for teaching three courses, instead of the normal two, from all the time I am going to devote to writing.

In the dark days of their careers, writers have to be their own cheerleaders.

Published on January 15, 2012 08:45

November 5, 2011

Advice to Young Writers

I am often asked to give advice to young writers who wish to be famous and fabulously well-to-do. This is the best I have to offer: While looking as much like a bloodhound as possible, announce that you are working twelve hours a day on a masterpiece. Warning: All is lost if you crack a smile.

- Kurt Vonnegut, in Palm Sunday

Published on November 05, 2011 12:50

December 30, 2010

Writing Space

My biggest challenge, as a writer, is making the time and finding the space in which to actually write. With two small children, the only quiet place left for me is my office at work. But the office is, of course, where I work. I can shut the door. I can drown out nearby voices with the air conditioner in summer. But in winter, quiet solitude does not come easily or predictably. But it does come.

And when it does, I struggle to find the discipline to disconnect from email and Facebook and the constant stream of news, politics, and entertainment. I'd blog more about this, but I'm trying to break away today (without much luck). So, quickly, I want to share this link, which came to me via the wonderful Oklahoma performance poet and activist Lauren Zuniga. From What Happened to Down Time? :

And when it does, I struggle to find the discipline to disconnect from email and Facebook and the constant stream of news, politics, and entertainment. I'd blog more about this, but I'm trying to break away today (without much luck). So, quickly, I want to share this link, which came to me via the wonderful Oklahoma performance poet and activist Lauren Zuniga. From What Happened to Down Time? :

There has been much discussion about the value of the "creative pause" – a state described as "the shift from being fully engaged in a creative activity to being passively engaged, or the shift to being disengaged altogether." This phenomenon is the seed of the break-through "a-ha!" moments that people so frequently report having in the shower. In these moments, you are completely isolated, and your mind is able to wander and churn big questions without interruption.

However, despite the incredible power and potential of sacred spaces, they are quickly becoming extinct. We are depriving ourselves of every opportunity for disconnection. And our imaginations suffer the consequences.Read the rest here.

Published on December 30, 2010 10:22

December 17, 2010

"The Writer at Work"

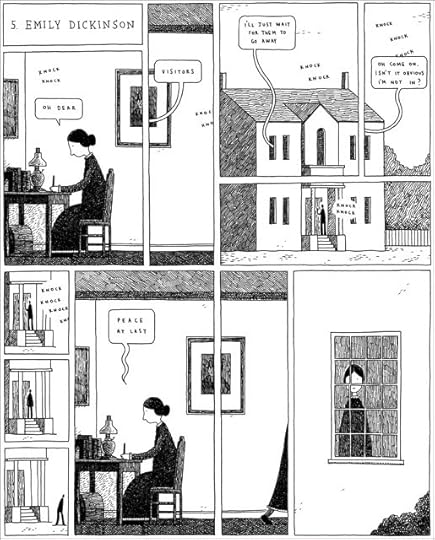

Don't miss Tom Gauld's "The Writer at Work" series, reproduced here. The Emily Dickinson is my favorite:

Published on December 17, 2010 10:24

September 21, 2010

"It's a way to make your soul grow."

You can read the transcripts of two riveting discussions between Kurt Vonnegut and Lee Stringer in the book Like Shaking Hands with God: a conversation about writing. Early in the book—no, the talk, the talk—Vonnegut addresses the effects that writing has on the writer:

But you shouldn't. Instead, quit surfing. And write.

There's a swell book that's out of print now. Maybe Seven Stories will bring it out again. It's called The Writer and Psychoanalysis by a man who's now dead named Edmund Bergler. He claimed he had treated more writers than anyone else in his field, and being that he practiced in New York, he probably did. Bergler said that writers were fortunate in that they were able to treat their neuroses every day by writing. He also said that as soon as a writer was blocked, this was catastrophic because the writer would start to go to pieces. And so I said in a piece in Harper's, or a letter I wrote to Harper's, about "the death of the novel": People will continue to write novels, or maybe short stories, because they discover that they are treating their own neuroses. And I have said about the practice of the arts that practicing any art—be it painting, music, dance, literature, or whatever—is not a way to make money or become famous. It's a way to make your soul grow. So you should do it anyway.Vonnegut mentions the bounty on Salman Rushdie then jokingly offer a million-dollar reward for the killing of Microsoft's Bill Gates:

Gates is saying, "Hey, don't worry about making your soul grow. I'll sell you a new program and, instead, let your computer grow year after year after year..."—cheating people out of the experience of becoming.Rilke wrote about the dizzying effects of urban commercialism and consumer society a few decades earlier, and in jest I've suggested Rilke had warned against the effects of Facebook. You can read that here.

But you shouldn't. Instead, quit surfing. And write.

Published on September 21, 2010 09:22

August 20, 2010

Call and Response

I write fiction because I am a bad poet. When I was much younger (in my mid twenties—so, young but not terribly young), I stumbled into fiction only after I got lost and wandered for years in the maze of poetry. Which is to say that when I admitted to myself I was no Rilke, no Rumi, no Mark Strand, no Mary Oliver, no e.e. cummings, only then did I notice the clear strands of narrative woven through the bent architecture of my ramshackle poems. I quit thinking of myself as a poet and became a fiction writer. And fiction felt good. It suited me in a way that poetry never had. I knew in short order that fiction was my calling.

Torre del Mangia, SienaYet I still turn to poetry when I want to kick myself into fiction writing mode. Perhaps I feel compelled to somehow relive the journey that brought me to fiction. Perhaps I have to blast my ears with poetry before I can properly hear the calling of fiction. More likely, though, I have learned to use the jolt from a good poem to jumpstart the engine of my fiction. (Clearly I need no prodding to start wildly mixing metaphors.) Whatever the reason, this works. When I don't know how to open a story or get started on another long day of revision, I reach for a poem. I steer clear of fiction. When I read a gripping, unsettling story, I want to write a story just like it. A good story triggers my impulse to imitate. A good poem compels me to write my own gripping, unsettling story in response.

Torre del Mangia, SienaYet I still turn to poetry when I want to kick myself into fiction writing mode. Perhaps I feel compelled to somehow relive the journey that brought me to fiction. Perhaps I have to blast my ears with poetry before I can properly hear the calling of fiction. More likely, though, I have learned to use the jolt from a good poem to jumpstart the engine of my fiction. (Clearly I need no prodding to start wildly mixing metaphors.) Whatever the reason, this works. When I don't know how to open a story or get started on another long day of revision, I reach for a poem. I steer clear of fiction. When I read a gripping, unsettling story, I want to write a story just like it. A good story triggers my impulse to imitate. A good poem compels me to write my own gripping, unsettling story in response.

At the risk of echoing the prejudice Charles Baxter reveals in the passage I quoted on Wednesday, I will generalize. Fiction writers take time to lay out the subtle intricacies of their art, and poets—at least the poets I read and love—seem to be more consistently and immediately in touch with the extraordinary, the intense, and the fantastic. No doubt, there are countless exceptions. What matters is only this: Reading poetry works. It works for me. It focuses my thoughts and energizes my intentions. Poetry calls, and I respond with fiction.

For you, this may not work at all. If you want to write—if you have no choice but to write—then listen for the bell that calls to you, and answer it. Find what works, and do it.

Now write.

Torre del Mangia, SienaYet I still turn to poetry when I want to kick myself into fiction writing mode. Perhaps I feel compelled to somehow relive the journey that brought me to fiction. Perhaps I have to blast my ears with poetry before I can properly hear the calling of fiction. More likely, though, I have learned to use the jolt from a good poem to jumpstart the engine of my fiction. (Clearly I need no prodding to start wildly mixing metaphors.) Whatever the reason, this works. When I don't know how to open a story or get started on another long day of revision, I reach for a poem. I steer clear of fiction. When I read a gripping, unsettling story, I want to write a story just like it. A good story triggers my impulse to imitate. A good poem compels me to write my own gripping, unsettling story in response.

Torre del Mangia, SienaYet I still turn to poetry when I want to kick myself into fiction writing mode. Perhaps I feel compelled to somehow relive the journey that brought me to fiction. Perhaps I have to blast my ears with poetry before I can properly hear the calling of fiction. More likely, though, I have learned to use the jolt from a good poem to jumpstart the engine of my fiction. (Clearly I need no prodding to start wildly mixing metaphors.) Whatever the reason, this works. When I don't know how to open a story or get started on another long day of revision, I reach for a poem. I steer clear of fiction. When I read a gripping, unsettling story, I want to write a story just like it. A good story triggers my impulse to imitate. A good poem compels me to write my own gripping, unsettling story in response.At the risk of echoing the prejudice Charles Baxter reveals in the passage I quoted on Wednesday, I will generalize. Fiction writers take time to lay out the subtle intricacies of their art, and poets—at least the poets I read and love—seem to be more consistently and immediately in touch with the extraordinary, the intense, and the fantastic. No doubt, there are countless exceptions. What matters is only this: Reading poetry works. It works for me. It focuses my thoughts and energizes my intentions. Poetry calls, and I respond with fiction.

For you, this may not work at all. If you want to write—if you have no choice but to write—then listen for the bell that calls to you, and answer it. Find what works, and do it.

Now write.

Published on August 20, 2010 09:44

August 18, 2010

Charles Baxter on The Writer's Life

Hello, and welcome to The 39th Draft. From the cozy, air-conditioned thrum of my office, I inaugurate this blog for young* writers—such as it is, such as it will be—with an offering of two passages excerpted from Charles Baxter's "Full of It"—a letter to a young writer, collected in Frederick Busch's excellent and damn near indispensible anthology

Letters to a Fiction Writer

(numbers and emphasis, mine):

Hello, and welcome to The 39th Draft. From the cozy, air-conditioned thrum of my office, I inaugurate this blog for young* writers—such as it is, such as it will be—with an offering of two passages excerpted from Charles Baxter's "Full of It"—a letter to a young writer, collected in Frederick Busch's excellent and damn near indispensible anthology

Letters to a Fiction Writer

(numbers and emphasis, mine):1.

Women and men who have decided to be fiction writers have a certain fanaticism. Sometimes this fanaticism is well concealed, but more often it isn't. They—you—need it, to get you through the bad times and the long apprenticeship. Learning any craft alters the conditions of your being. Poets, like mathematicians, ripen early, but fiction writers tend to take longer to get their world on paper because that world has to be observed in predatory detail and because the subtleties of plot, setting, tone and dialogue are, like the mechanics of brain surgery, so difficult to master. Fanaticism ignores current conditions (i.e., you are living in a garage, surviving on peanut butter sandwiches, and writing a Great Novel that no one, so far, has read, or wants to) in the hope of some condition that may arrive at a distant point in the future. Fanaticism and dedication and doggedness and stubbornness are your angels. They keep the demon of discouragement at bay. But, given the demands of the craft, it is no wonder that so many of its practitioners—women and men—come out the other end of the process as drunks, bullies, windbags, bespoke-suited merchants of smarm, and assholes. The wonder is that any of them come out as decent human beings. But some do.

A writer's life is tricky to sustain. The debased romanticism that is sometimes associated with it—the sordid glamour of living in an attic, being a drunken oaf or a bully, getting into fistfights á la Bukowski—needs to be discarded, and fast.

2.

It seems a shame to say so, but the hardest part of being a writer is not the long hours of learning the craft, but learning how to survive the dark nights of the soul. There are many such nights, far too many, as you will discover. I hate to be the one to bring you this news, but someone should.

Part of the deal of having a soul at all includes the requirement that you go through several dark nights. No soul, no dark nights. But when they come, they have a surprisingly creepy power, and almost no one tells you how to deal with them. You can do illegal drugs or take psychoactive pills, you can have affairs or masturbate, you can watch movies 'til dawn, but that only produces what doctors call "symptomatic relief." In these nights you confront your own doubts, lack of self-confidence, the futility of what you are doing, and the various ways in which you fail to measure up. Feelings of inadequacy are the black-lung disease of writing. These are the nights during which the Fraud Police come to knock on your door.

Psychologists have their own name for this set of feelings. (They have clinical names for most of our emotions by now.) They call it "imposter-syndrome." Imposter-syndrome is endemic to the art of writing because gifts—the clear evidence of talent—are not so clearly associated with writing as they are with music and graphic art. Not everyone has perfect pitch, not everyone can carry a tune, not everyone can draw or create an interesting representation of something on canvas. But almost every goddamn moron can write prose.

Furthermore, anyone's apprenticeship in the writing of fiction has several stages, at least one of which involves an imposture. To be a novelist or short story writer, you first have to pretend to be a novelist or a short story writer. By great imaginative daring, you start out as Count No-Count. Everyone does. Everyone starts as a mere scribbler. Proust got his start as a pesky dandified social layabout with no recognizable talents except for making conversation and noticing everybody. So what do you do? You sit down and pretend to write a novel by actually trying to write one without knowing how to do it….

The trouble is that the first stage—of pretending to be a writer—never quite disappears. And there is, in this art, no ultimate validation, again because it's not a rule-governed activity. The ultimate verdict never comes in. God tends to be silent in matters of art and literary criticism.

A young writer could do far worse than investing a few bucks in this book.

Now write.

* Chin up! "Young" in this case means anyone, of any age, who is new to writing, returning to writing, or simply engaged in the ongoing and often quite difficult journey of the writer.

Published on August 18, 2010 09:46