Mike McCabe's Blog

February 18, 2026

First Things First

I’ll believe it when I see it. Been hearing that forever, considerably more now than before. Wanting proof is understandable, no one wants the wool pulled over their eyes. Nothing wrong with healthy skepticism. Trust but verify, as Ronald Reagan famously said.

Yes, verify, by all means. Document the dotting of every i, the crossing of every t. But when all the scrutiny, the evidence gathering, the fact checking is done and still doesn’t yield trust, that’s a danger zone where skepticism morphs into cynicism. A skeptic questions; a cynic assumes the worst. There is an abundance of cynics nowadays.

When tension between verification and trust reaches a breaking point, one casualty is clarity of vision, another is imagination, a third is faith.

I wrote last week about focusing on a hazard so intently that our field of vision narrows. All we see is the menace we wish to avoid or escape, leaving us unable to see what lies beyond the obstacle.

After hearing “I’ll believe it when I see it” for the umpteenth time over just the last couple of weeks, I went looking for insight on the subject and stumbled upon an episode of Trevor Noah’s podcast from back in December. At about the 20-minute mark of his conversation with Zohran Mamdani, the decline of imagination in this terribly cynical age of ours comes up. I’ll let them do the explaining.

Something Noah said about faith is especially striking: “One of the things that faith requires of you is the ability to believe that this current state that you are in is not the end. There is a possibility that something can be greater.”

Then he says this:

“Even though you cannot see it, you believe that it can happen.”

This idea is an endangered species in today’s America.

My thoughts stray to my late father. The loss of his own father to colon cancer at a young age resulted in Dad being granted a military draft deferment exempting him from service so he could support his mother and three sisters. Seeing Hitler on the move, his army seemingly invincible, European countries falling like dominoes, Dad decided not to exercise his deferment and joined the fight.

He did not go off to fight the Nazis knowing the allied forces would win, he fought them because they were Nazis. The war was not going well, prospects for victory were dim. Even though he couldn’t see how Hitler could be taken down, he must have believed it could happen. He had faith, risked his life for it.

Today we have rich and powerful men who’ve committed unspeakable crimes and consider themselves above the law. They’ve yet to face accountability for their atrocities. We have rogue government forces invading and occupying and terrorizing and traumatizing communities, running roughshod over civil liberties and constitutional rights. Democracy is under siege.

Cynicism does not shield us from these threats. It doesn’t bring heartless, soulless pedophiles and their accomplices one step closer to justice. Accountability must be tirelessly sought, not because it is certain justice will be done, but because they are criminals. This regime’s authoritarian designs must be resisted, not because any of us is sure democracy can be saved, but because it is worth saving.

First things first. Believe, then see.

February 9, 2026

Sueña, Mi Nación

Couldn’t understand the words, still the message came through loud and clear. Never have been especially swift at picking up languages, or deciphering lyrics sung in my mother tongue for that matter. Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio got his points across in spite of my shortcomings.

The performer known far and wide as Bad Bunny made history as the first artist to perform a Super Bowl halftime show almost entirely in Spanish. America’s superiority-complex-in-chief was disgusted by the spectacle, insisting “nobody understands a word” coming out of the Puerto Rican rapper’s mouth. Nobody. Or half a billion people worldwide, close to 50 million in this country alone.

I do not count among these masses who speak Spanish, yet Bad Bunny’s performance spoke to me as well, transcending cultural and linguistic barriers through the universal languages of rhythm, harmony and movement. I felt the energy, the unbridled exuberance. I caught the symbolic expressions of pain and frustration, of hope and resilience. The sugarcane, the sparking electrical poles, the wedding ceremony (not a staged one, actual nuptials).

My heart melted along with so many others when Bad Bunny handed his Grammy Award to a 5-year-old boy. Many were on high alert for political statements, many rushed to social media to speculate the boy was none other than Liam Ramos, who was kidnapped by federal agents to use as bait to lure his parents out of their Minneapolis home. It was not Liam, though the actor who shared the moment with Bad Bunny bore a striking resemblance.

If this was a jab at paramilitary goons occupying Liam’s hometown, it was an artfully subtle one. To me, it came across as a symbolic passing of the torch to the next generation, a proclamation that anyone can pursue their dreams and achieve great things.

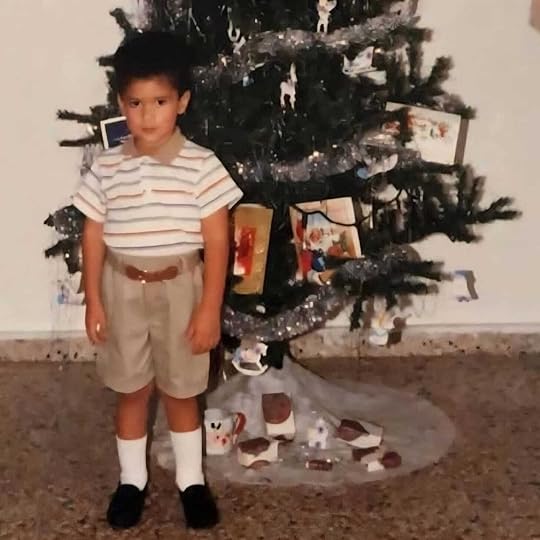

The actor in this scene, half-Argentinian Lincoln Fox, was dressed exactly how a young Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio looked standing in front of his family’s Christmas tree, wearing a striped collared shirt and khaki shorts.

About the only thing Bad Bunny said in English on Sunday was “God bless America,” and I surely noticed when he then named every country in the Americas. I took this not as protest but as celebration and aspiration. My takeaway was that he must be immune to the ailment that afflicts so many across the cultural and ideological landscape on the U.S. mainland.

More of us than not suffer from obstacle fixation, obsessively focusing on a hazard to the point where it narrows our field of vision until all we see is the menace we wish to avoid or escape. We fixate on it so much that we can’t see what’s beyond it, can no longer tell there are clear paths around it.

Couldn’t make out many of the words Sunday, but the lesson embedded in Bad Bunny’s joyous, celebratory art sunk in nevertheless. Pay less attention to the nightmare and more to the dream.

February 2, 2026

The Worst Trade Ever

He made the deal the day after Christmas in 1919 and his name is mud in some quarters to this day. Harry Frazee was still young, not yet 40, a theatrical agent, producer and director, at the top of his game, eyes on him after he made a small fortune on stage productions in and around Chicago, built Chicago’s Cort Theatre, moved to New York around 1910, took aim at Broadway.

In no time Frazee was printing money on Broadway, with a string of his shows—Madame Sherry, Ready Money, A Pair of Sixes, A Full House and Nothing But the Truth—becoming huge hits. The small fortune grew large. He built the ornate Longacre Theatre in Midtown Manhattan, kept it full with his own productions and those of others.

Nearly everything Frazee touched made money, a real estate company, a brokerage business. He managed a professional wrestler, dabbled in boxing promotion. He knew everybody who was anybody, not just in New York, but all over the Northeast, including Boston.

Baseball was the national pastime. With more money than he knew what to do with, Frazee made a bid in 1911 to buy a major league baseball team, the Boston Braves. When that pursuit was thwarted, he made additional overtures, showing interest in acquiring the Chicago Cubs and the New York Giants. Finally, in 1916 he was able to swing the purchase of Boston’s other big-league team, the Red Sox, but was mortgaged to the hilt to pull off the transaction.

For a brief time, it looked as though another thing Frazee touched had turned to gold, as the Red Sox won the 1918 World Series. But the Great War had disrupted the public’s appetite for amusement. The 1918 and 1919 baseball seasons had been shortened, diminishing gate receipts. Frazee’s latest Broadway production, A Good Bad Woman, tanked in the spring of 1919, opening and closing in the span of only a month. A new show, My Lady Friends, was to open by year’s end, but cash was short to bring it to the stage. His team’s best player was demanding that his salary be more than doubled.

Harry Frazee is no household name. The same cannot be said for that player who wanted the big raise. George Herman Ruth. The Babe.

Ever the wheeler-dealer, the asset-rich but cash-poor Red Sox owner sold Babe Ruth to the rival New York Yankees for $100,000—$25,000 up front, with three promissory notes for $25,000 at 6% interest due in each of the next three years—plus a $300,000 loan at 7% a year for which Frazee put up Boston’s Fenway Park as collateral.

Including interest, Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert paid Frazee $108,750 for Ruth, whose legendary exploits and the fan reaction they generated led to the Yankees amassing $3.4 million in profits over the course of the Babe’s 15 years in pinstripes. The $300,000 loan was not repaid until July of 1933, meaning Frazee’s Red Sox must have paid Ruppert something in excess of a quarter-million dollars in interest over a 13-year period. In the end it was Frazee who paid Ruppert, not the other way around, to take arguably the greatest baseball player who ever lived off his hands.

A century later The New York Times quoted an economist describing Ruth’s sale as “the greatest financial swindle since the purchase of the Louisiana Territory,” and called it a “transformational moment, not just for two baseball franchises but also for the cities they inhabited. Boston became the capital of grievance and curse; New York became the locus of power and stardom, and not just in sports.”

One hundred and five years after that great swindle, an entire nation repeated Harry Frazee’s colossal error, bewitched by performative spectacle, trusting in the art of the deal. Americans were in a foul mood, felt financially strapped, many wanted someone—or something—to blame. Looked for easy solutions to complicated problems, wanted to think we could tariff our way to revived manufacturing on our soil, wanted to believe we could deport our way to renewed prosperity. Bought into grievance and its faithful travel companion cruelty.

The biggest Harry Frazee of our time continues to wheel and deal like crazy, to no good effect. In demanding ownership of Greenland, the U.S. needlessly alienated trusted allies, eventually pushing away from the negotiating table with no more than we already had before wrecking all those relationships. For the empty promise to restore national glory, we pay an immense price. We surrender the moral high ground, diminish our standing globally, abandon any claim to leadership of the free world.

So here we sit, Americans still in a foul mood, still financially strapped, swindled for certain, bound to pay through the nose for what’s being stolen from us just as Harry Frazee was obligated to pay interest on his foolishly accumulated debt. And those payments will be only a small part of the Ruthian price we pay for what little we ever get in return.

History will judge the trade our country is making now as the worst ever. Worse even than the one Harry Frazee made the day after Christmas in 1919.

January 26, 2026

Warmth in the Freezing Cold

Hate the sin, love the sinner. Wise words. Downright magical when put into action. Still hard to take to heart, easy to forget.

One horrifying story after another after another after another after another after another has emerged from the besieged Twin Cities in recent days. Details have been meticulously chronicled. Images are burned into memory. The extensive coverage is more than justified, the public needs to know the full extent of authoritarian overreach involved in the ruling regime’s lawless immigration raids.

When rogue federal agents snatch a 2-year-old girl and ship her from Minnesota to Texas in defiance of a judge’s order, other big stories get overshadowed. When they kidnap a 5-year-old boy to use as bait to draw family members out of their home, other critically important news goes unnoticed. When they force open the front door of a home without a warrant, slap handcuffs on a barely clothed man—a U.S. citizen—and pull him out into the freezing cold as his 4-year-old grandson watches, crying inconsolably, even the most remarkable and inspiring stories have a way of getting lost in the shuffle.

One story in particular was easy to overlook considering the grave circumstances. Perhaps you’ve already heard it, no matter, it bears repeating. This story shows a way forward, a way out of seemingly impenetrable darkness.

White supremacist and January 6 insurrectionist Jake Lang was imprisoned while awaiting trial for beating Capitol police officers with a baseball bat. Eleven charges against him went away thanks to a presidential pardon. A free man on account of that criminal injustice, he went to Minneapolis City Hall a little over a week ago with plans to burn the Muslim holy book before leading a march to a neighborhood that is the heart of the city’s Somali community.

Lang never did get around to burning the Quran or leading his parade. Only a handful of supporters showed up for his rally, vastly outnumbered by hundreds of counterprotesters who sprayed water on Lang and draped him with silly string as he stood on a window ledge, drenched and shivering on this frigid afternoon. The surging crowd showed no mercy, pulled him down from the ledge, pinned him against a wall. Several kicked and struck Lang, bloodying him.

There’s no telling what might have happened next if Isaiah Blackwell, a 30-year-old Black man, had not put his body between Lang and the counterprotesters. Blackwell stood face to face with Lang, shielding him from further attack. He then led Lang away from City Hall, at times acting as a blocker clearing a path of escape, other times clutching him by one arm or guiding him from behind with hands on his shoulders. “Don’t touch him, let him go,” he cried. Lang made it to a nearby hotel.

Former Minneapolis Mayor R.T. Rybak said, “Lang saw that Black man as less than him. The Black man saw Lang as a human being.”

Lang benefited from more than Blackwell’s intervention that day. Aleigha Henderson and Daye Gottsche were driving by the hotel on the way to a bar, and Lang ran up to their car at a red light, begging to get in. They let him in, “trying to do a good deed,” as the 25-year-old Henderson put it.

Protesters opened the back door, tried pulling Lang out of the car and kicking him as he pleaded with Henderson to drive. She peeled out once the light turned green. Lang wouldn’t tell them who he is or what was going on, only mumbling something about how Trump had saved his life. Gottsche, a 22-year-old trans woman, said the two got “weird vibes” from him and pulled over after a few blocks and told him to get out, saying they were just trying to go have a drink. “I’m not invited for the drinks?” Lang asked. “No!” the friends shouted in unison.

Well beyond harm’s reach by this time, Lang had lived to hate another day. He later told InfoWars host Alex Jones that he was “lynched” but some “Good Samaritans” saved him. He seemed puzzled, struggling to make sense of people out in the freezing cold summoning the warmth of spirit to protect someone who came to demean them and hurl hateful filth in their direction. “Many of them were Black. Some of them were even Muslim,” he told Jones, marveling at “this underlying human compassion.”

Maybe Jake Lang’s heart remains frozen over, perhaps it thawed just a little that day. At a bare minimum, the power of his rescuers’ actions made an impression on him. Lasting impact on Lang or no, these unassuming heroes set an enduring example for the rest of us. They did not lower themselves to his level. Instead, they took a hateful man into their care. What they didn’t let in was hatred itself, even when it was delivered directly to their doorstep.

With cruelty firmly established as national policy and circulating like legal tender, it grows more tempting by the day to go with the flow, to respond in kind. Fortunately, there are angels among us, guiding not with measured words but spontaneous gut reaction, a reminder there is a far more powerful response at our disposal. Pass it on.

January 20, 2026

The New Company Store

Dad was a tenant farmer, never satisfied him, longed for land of his own. Mom was a farm wife, more by fate than choice. A homemaker, more by default than desire. Did far more than cook, clean and tend the kids. Helped in the barn every day and in the fields when needed, kept the books, juggled the finances, without complaint. Her life was not the stuff of her dreams. Suffered from depression she hid as best she could, to little avail.

Dad had reached his 50s by the time he became the owner of a 200-acre, 40-cow dairy operation. He’d pinched pennies for decades, doing farm labor before and after shifts in a factory and on weekends, at one point going more than three decades without a day off. Finally, he could work land and milk cows full time on a farm titled in his name, with a bank lien, of course.

He splurged, paying to have a customized magnetic sign made, one he proudly slapped on the driver’s side door of his truck. Big black letters against a white background, “C.J. ‘Chuck’ McCabe & Sons” with the farm’s address below.

Even before reaching adolescence, I saw injustice in Dad’s sign. Mom got no billing, no recognition of her many contributions to the family business and our household. Neither did my three sisters. That was wrong, but also very much in keeping with the times.

Upon gaining statehood in 1848, original Wisconsin law treated women as appendages of their husbands, giving men absolute control over their wives’ property. Early efforts to change that were fiercely resisted, with one debater wondering “will her welfare, and feelings and thoughts, and interests be all wrapped up in her husband’s happiness, as they now are?”

Women did not gain the right to have their own credit cards and bank accounts without a male co-signer until 1974. It wasn’t until the mid-1980s that Wisconsin law was changed to presume spouses equally share marital property. That was the first significant piece of legislation I worked on as a state assembly aide.

Fresh out of school, little more than a lowly clerk, I got to be in the room where it happened, the office of one of the most prolific lawmakers my homeland has ever known, as she plotted strategy for driving her handiwork down the field and across the goal line. I imagine seeing this measure of equality written into state law made Mom happy, though she never said so.

I reflect back on all this as I consider the mess our society is in today. Dad and Mom passed years ago, but I can’t help but think the angst and anger eating at us nowadays traces to the same powerful impulse they felt in their time, the desire to have something they could call their own. Titled in their name, with a legal deed to hold on to, there’s something real solid about that.

It’s commonly and cynically said that everything is for sale. Except that’s not quite true. Most things are for rent. Nothing’s built to last anymore, everything’s made to wear out fast. Since few things we buy can be repaired because they are no longer designed to be fixable, it’s hard to say we really own them, they’re not really ours. We pay to use a home appliance, it stops working and is discarded, we pay to use another until the time comes to dispose of it. Same goes for the smaller stuff, too. Record collections have gone the way of the dinosaur; we pay subscription fees to stream music. We rent this, subscribe to that. No titles, no deeds, no ability to keep things working, fix what’s broken, just an app to manage all the subscriptions.

It was once in fashion among our nation’s elites to talk of creating an ownership society. It was just talk. The forces driving the economy—profit, preoccupation with the acquisition and accumulation of consumer goods—have steadily driven us in the opposite direction, toward a new feudalism with a few owner-lender lords and masses of renter-borrower serfs.

Buy-now-pay-later is deeply engrained in the nation’s psyche. Credit card debt and overall household debt continue to spiral upward and are at all-time highs. To keep consumers buying, corporate America carefully nurtures a throwaway culture, fights the right-to-repair movement tooth and nail. To lower costs as well as their own accountability, companies are killing off customer service, using AI bots to perform that function.

Dad wanted to run his own business, be his own boss. Mom deserved recognition of what she contributed economically. They both wanted to feel justly rewarded for all their work, to have something to show for it. If they were still alive, they’d be swimming against powerful currents pushing them away from ownership and toward being renters and subscribers. They’d be treated as we all are now, as faceless consumers, as numbers, rather than living, breathing customers. As subjects, not citizens. They’d be diminished, as we all are now.

We’ve been in a place like this before. History never truly repeats itself, but it often rhymes.

You load sixteen tons, what do you get

Another day older and deeper in debt

Saint Peter don’t you call me ’cause I can’t go

I owe my soul to the company store

“Sixteen Tons”

Tennessee Ernie Ford

January 12, 2026

Pogo's Reminder

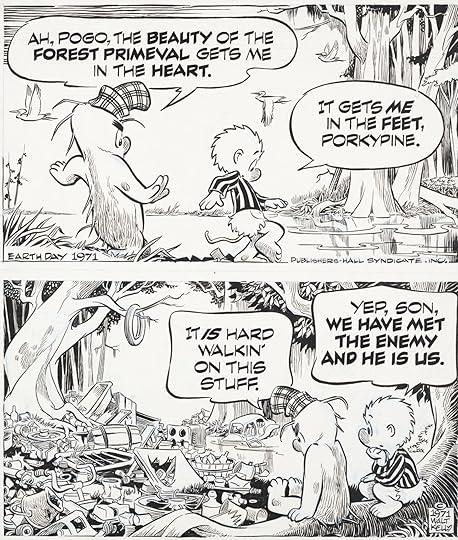

Cute as a button, teller of ugly truth. Pogo the comic strip possum, born way back in 1948, dispenser of wit and wisdom from the Okefenokee Swamp over a lifespan of nearly 27 years.

After working as a Disney animator, Walt Kelly struck out on his own, creating his trademark character who channeled Kelly’s seemingly simplistic but slyly perceptive comments about the state of the world and politics. Pogo is best remembered for uttering a phrase that echoed through the ages and still reverberates today.

The quip first appeared in a poster Kelly designed to help promote environmental awareness and publicize the first annual observance of Earth Day, held on April 22, 1970. Kelly used the line again in the Pogo strip published on the second Earth Day in 1971.

Back then, it was perfectly legal to dump untreated sewage and industrial waste into local waterways and turn natural areas like Okefenokee Swamp into toxic waste dumps. Earth Day helped raise awareness and inspire a grassroots environmental movement that won crucial battles to raise air and water quality standards and restrict deadly pollutants. The impact of these victories was immense.

Then complacency set in, creating an opening for a fierce backlash that’s prompted numerous rollbacks of natural resource protections and conservation measures. Now, against a backdrop of spiraling atmospheric carbon dioxide levels that are altering the Earth’s climate, there is binge construction of AI data centers that will devour only slightly less energy than Egypt and more than Malaysia while generating more carbon emissions than major cities. They’ll consume more water than all the bottled water sold globally, six times more than the entire nation of Denmark consumes. This at a time when a quarter of humanity already lacks access to clean water and sanitation. On top of that, data centers produce copious amounts of electronic waste containing hazardous substances like mercury and lead. We have met the enemy.

Pogo must be playing dead, every possum’s instinct when sensing grave danger. But the little fellow’s timeless message still resounds. Not easy to hear with all the noise pollution, what with America well on its way to becoming a police state domestically and a might-makes-right bully globally to ethnically cleanse our nation, distract from unnerving economic uncertainty and stifle social unrest.

Pogo’s famous warning surely rang out on November 5, 2024. That’s when Google searches for “Did Joe Biden drop out” started, beginning around 6 a.m. on election day, continuing to rise over the course of the day, reaching a peak near midnight. Spiked again around 8 a.m. the day after. Prior to election day, there were virtually no such searches even though President Biden dropped his re-election bid in July and endorsed Kamala Harris. We have met the enemy.

Pogo comes to mind whenever willful ignorance rears its head. To be clear, I’m not chalking this up to any mental deficit, I speak of a deliberate choice to remain oblivious. It’s not a matter of being smart or dumb, it’s a matter of paying attention or not paying attention.

I once journeyed the length and breadth of the state of Wisconsin as if Pogo was on my tail prodding me. It was 2018, and I was a candidate for governor. Our campaign traveled over 100,000 miles in 11 months, visited every county, held dozens of town halls and meet-and-greets, took part in more than 50 candidate forums, did hundreds of media interviews.

Since then, I’ve lost count of the number of times I found myself conversing with highly intelligent, well-educated people who talk a good game about how they are alert, informed and engaged citizens who always vote. Who, when my candidacy was brought up, had no idea. Couldn’t believe I’d ever done such a thing.

Running for office is an exhausting ordeal that puts enormous strain on family life. No two ways about it, coming up short after putting in all that time and effort is painful. When a mere 11.8% of Wisconsin’s eligible voters bothered to cast a ballot in the party primary election that I was a part of, it felt like salt rubbed in the wound.

Not long after the election was over, I went with my family and a neighbor of ours to a screening of the documentary Knock Down the House about four women who ran for Congress against all odds that same year. I felt a kinship with the three who lost their races. I marveled at Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s shocking upset win.

The last poll in her race showed her trailing her primary opponent, one of the top-ranking Democrats in the House, by a staggering 35 percentage points. An especially poignant moment in the film shows an anguished Ocasio-Cortez coming to terms with her likely fate on the eve of the election, wondering aloud if she had let down all the people who had done so much on her behalf. I tried my best to fight back tears, but they streamed down my cheeks.

As I watched AOC sort through her emotions, I thought about the more than 3,000 volunteers who worked so incredibly hard in hopes of getting me elected governor. They were my voice, my surrogates in neighborhoods up and down the state. They were my TV ads, for we couldn’t afford the real kind. I thought about one in particular from the La Crosse area who volunteered his evenings and weekends even as he was working more than 40 hours a week at his paying job to make ends meet. As the election approached, he donated his two weeks of paid vacation for the year to work full-time on the campaign.

Like Ocasio-Cortez, the feeling that I had let him and so many others down tormented me. I thought I had worked through those emotions, but watching the film made me realize I had just stuffed them in some psychological sock drawer. The movie forced that drawer open.

The drawer reopens every time I encounter willful ignorance. It reopens each time I see earnest, honest women and men tarred with a broad brush, belittled as just another power-hungry crook for treating public service as a duty and putting their name on a ballot. The depleted souls doing the tarring have always shirked that duty themselves, have no clue how much of an emotional toll has to be paid when answering democracy’s call. They also have no idea what cost there is to society if good people grow unwilling to tempt the bitter fate of a very public humiliation when the votes are all counted, some cast by peers frighteningly unaware enough to have googled “Did Joe Biden drop out” on the day of the last presidential election.

I took Pogo’s message to heart, ran with purposeful abandon, paid the hefty toll, was tarred with the broad brush, suffered the sting of defeat, was left with that nagging feeling I had let thousands of people down. But I can still say without hesitation that it’s all worth it. Worth it even should you become the target of cynical condemnation. Worth it because civilized society and the planet that sustains us are worth protecting. Worth it to avoid becoming the enemy.

January 6, 2026

The Thrill of the Blank Page

No working Congress, Lolita and Weekend at Bernie’s playing in turns at the presidential palace, Caracas had to look appealing. Ripe for the taking. After that, maybe Kalaallit Nunaat. Google it and you’ll know.

All was calm one moment, such a clatter arose the next, waking us from a long winter’s slumber to news of invasion, explosion, abduction. The breaking down of doors, the breaching of someone’s domicile, how twistedly fitting, seeing how the first month of the year’s name derives from the Latin word for doorway. A start like this makes you think we’re in for a long year of rough sailing. Batten down the hatches.

Those unconcerned with empire see January as a moment of passage, a fresh start. We resolve to put troubles behind us, though we know in our heads if not our hearts that they remain. January’s not the clean slate we like to think it is. An hour, a day, a week, a month, they all bleed into the next. The start of a new year is hardly a clear point of demarcation, but it is an opportune moment to ponder leaves worth turning over. We are changing constantly but rarely consciously.

Change usually just sort of happens, maybe because we’re not as open to it as we should be. We humans are prone to closing cases after considering scant evidence, rushing to judgment on the flimsiest of first impressions. Those first impressions have a way of calcifying, soon becoming hard as cement. We assume we know others, assume we know what they’ll do next, assume it’ll be what they did before.

Case in point. A month ago, I wrote a piece titled “Curled Up in a Ball” about how quick we are to brand certain people disengaged or apathetic when, in reality, emotional self-defense during trying times isn’t the same as not caring. Encounters with two audiences—one very young, one considerably older—drove that home for me. I noticed no signs of apathy. What I did see and hear was exasperation that leaves them feeling powerless.

My essay shared episodes from Wisconsin’s past as reassurance that the “cure for this powerlessness that ails us can be found in our own history, provided we have the wisdom and courage to teach it and the good sense to believe in it.”

I posted a brief summary along with a link to the article on several social media platforms. No mention was made of Republican or Democrat, red state or blue, left or right, not in the summary, not in the article itself. Still, a scroller on Facebook blurted, “I see virtually NO ‘good sense’ on the alt-right, Mike. Please stop being an apologist for the MAGA movement members.”

I replied that no one referred to in the article qualifies as “alt-right” or MAGA, and it makes no apologies for anybody.

He fired back: “I did not bother to read your article…. I have heard you speak elsewhere. I have read your words written elsewhere. I am not one who supports your lines of reasoning. I have encountered many people, had many conversations with many people…I do not encounter ‘goodwill’ from all these conversations and meetings. There is a lot of hate-infused and a lot of hate-driven energy in Wisconsin and in our nation at this time…. I do not like your thinking…. I stopped reading what you wrote a good while ago.”

Yet after all this good while he was drawn to my post, couldn’t resist weighing in, assumed he knew what the article was about, went ahead and judged it. Pretty much the definition of prejudice.

His screed was far lengthier than the excerpts shared here. He didn’t specify when or where he heard me speak, but volunteered that he’d read a book of mine published in 2014. I think that book’s insights and conclusions have aged pretty well, better than my body has. He obviously disagreed then and continues to disagree now. Who’s right doesn’t matter. What matters now is I am not the same person I was when he decided who I am. I’ve done another dozen years of living, give or take, moved on from prized experiences, embarked on new adventures, learned a thing or two along the way. I keep moving, changing as I go. We all do.

It’s dangerous to assume we know each other. Predicting next steps based on ones already taken is folly. We have to give ourselves room to grow because grow we surely will.

Shakespeare might have been right; past may be prologue. But it’s not the whole book. That still needs to be written. The blank page is thrilling in a way, an invitation to invention, a summons to make a break from the past, create something brand new. But oh how it sets nerves on edge in the halls of Congress, at the presidential palace, on social media newsfeeds, the bustling streets of Caracas, the desolate lands of the Kalaallit. Google it, you’ll see.

December 29, 2025

Something's Off

What a difference a little three-letter word can make. Well means healthy. Well off means wealthy. Compared to most others, the U.S. is a high-income country, among the wealthiest nations in the world, but far from the healthiest. Americans live shorter lives and suffer more illnesses and injuries than people in other high-income countries, despite spending considerably more on health care.

As goes one of those songs meant for singing around this time, I’ve no wish to come between the season and your enjoyment, so I bid you pleasure and bid you cheer. Still, this is the time of year for taking inventory. If done honestly, it’s impossible not to see that something is off here. America is unwell. Our obsession with being well off has a lot to do with it.

The obsession makes us fond of locks and gates and guns and video surveillance. It fills us with grievances, which in turn fertilize intolerance of difference and indifference to suffering. From this grows a self-absorbed, cold-hearted mean streak. Numb to cruelty one moment, accepting of barbarity the next.

Yearning to be well off above all else—even at the high cost of unwellness—diverts one’s gaze from social and economic injustice, how wealth and power feed off each other. Concentration of wealth produces concentration of power, greater concentration of power leads to further concentration of wealth, a corruption cycle that has put our country in a death spiral.

Another year coming to a close, a new one about to dawn, billionaires well on their way to becoming trillionaires. Goodbye neighborhood, hello island sanctuary. Old acquaintance, forgotten. Cup of kindness, poured out on the ground. Something is off here. America is unwell.

Surely I can’t be alone in noticing that people who have the least in this world, materially speaking, are often the most giving. I once lived for two years in one of those places our nation’s mean-streak-in-chief calls a shithole. At the time, people there were living on less than a dollar a day but never hesitated to welcome a stranger, share a meal, offer shelter, give what little they had. They are poor in ways we are rich, rich in ways we are poor.

They are not well off, but they are well. There’s a big difference between the two conditions. To a much greater extent than most Americans realize, our society’s fate in the new year and beyond will depend on recognizing that difference, taking it to heart, striking a better balance.

As that other song always sung this time of year asks, should old acquaintance be forgot? Good God, no. Better to remember every fellow passenger, cultivate associations with all our might. While we’re at it, take a cup of kindness, that true source of wellness, offer it generously, share the health.

December 15, 2025

'Just Needs a Little Love'

Branches sag under the weight, a boy cries out in anguish.

“Isn’t there anyone who knows what Christmas is all about?!”

A voice answers. Not a neighborhood chum’s, not this time. One from the grave.

The voice of that passed soul reminds us Christmas is not about the invention of a religion, it’s about a new birth of morality, or at least a fresh opportunity for people to do what’s right for a fleeting moment, show some mercy, extend a courtesy, practice generosity.

“Morality is doing what is right, no matter what you are told. Religion is doing what you are told, no matter what is right.” — H. L. Mencken

Christmas is about doing what’s right, Charlie Brown. And it’s about what it does to us. Slows us down, gets us to set aside workaday worries and material pursuits, makes us a little more patient with each other, gentler, kinder. The effect is only momentary, but it’s remarkable. That’s why Christmas is worth celebrating.

Living as we do, doing as we’re told, for nearly the whole year, worshipping the market, scrolling, buying, scrolling some more, keeping possessions close, the distance between us grows. Sagging under the crushing weight of our troubles, the many messes made, bridges burned, bonds broken. Then that forsaken refrain rings out: Happiness is not found in things but in relationships.

This wisdom should be continuously expressed and heeded but tends to be seasonal instead, glad tidings sounded in a Yuletide sermon or carol. There’s no need to wait for this wondrous thing called Christmas to arrive, it doesn’t have to be a pastor or a choir or a boy or a voice from the grave spreading the word. In a recent 60 Minutes interview, it was a psychology professor extolling the virtues of human connection.

@60minutes 60 Minutes on Instagram: "“We are at the brink of having more r…

60 Minutes on Instagram: "“We are at the brink of having more r…“Reclaim what it means to be human.” That’s the spirit.

December 9, 2025

Curled Up in a Ball

We call it one thing when it’s most likely another. One thing’s for sure, it’s all around us. A second thing’s for sure, it’s infectious. Passes easily from one carrier to the next. Right here, over there, everywhere, all at once. Widespread and contagious. Qualifies as an epidemic.

The symptoms are hard to miss. Hands thrown up in exasperation. Frustration morphing into resignation. Looks like quitting. Comes across as no longer giving a damn. We say it’s apathy, but nine times out of ten it’s not. Apathy means not caring. Judging from how heartsick many of those throwing up their hands appear to be, they must care a great deal.

Many are choosing to tune out the news these days. It’s tempting to chalk that up to indifference, too. Not so fast. Their reasoning, explained in an unsettled tone, makes it seem less like checking out and more like an act of emotional self-defense. Watching the decline of civilization in real time produces such overwhelming feelings of helplessness for some that they fear for their mental well-being. They’re curling up in a ball, not because they’re apathetic, because they’re feeling besieged and powerless.

Two encounters with very different groups drove this home for me. In recent weeks, I was asked to give talks on Wisconsin political history, one to a classroom full of students in a small-town high school, another to a 50-and-over crowd. Both presentations were well received. Both audiences seemed genuinely appreciative. At the same time, it was clear neither had escaped the epidemic’s spread. The signs were unmistakable.

I started both talks describing how Wisconsin politics was originally as crooked as the Kickapoo River. Bribing public officials was perfectly legal for the first half-century of statehood, for crying out loud. Financial ruin and widespread hardship scared Wisconsin straight. Bribery was outlawed. Corporations were barred from seeking to influence elections. A new political culture took root that earned our state a national reputation not only for squeaky-clean politics but also trail-blazing social and economic reform.

That political culture was a powerful guiding influence for the better part of a century, and this invisible hand still had a firm grip when I first started working as a lowly aide at the State Capitol more than 40 years ago. Somewhere along the line, we lost our way. We let corruption regain a foothold and, not coincidentally, lost our pioneering spirit. Wisconsin’s one-word motto—Forward—went from being our defining characteristic to an empty promise.

After class was over, the students’ teacher confided in me how concerned he is about the apathy of Gen Z. Maybe I mistake raging hormones for youthful exuberance, but these Zoomers sure didn’t seem checked out. They couldn’t wait for the post-presentation Q&A to jump right in, interrupting my talk several times with questions and comments.

Peer pressure being what it is, such engagement by students is a fairly rare but welcome exception, not the rule. Years ago, I ran a civic education program that took me into dozens if not hundreds of schools, where I made nearly 700 classroom presentations. Most times, teachers would try prompting students to pipe up, to no avail, then would ask questions in their stead. Not this time. These kids kept peppering me until the bell rang.

That surprised me. Equally striking was the nature of their contributions to the discussion, sour bordering on angry, fatalistic. The system’s crooked, the game’s rigged, always has been, always will be. As if they very selectively heard what I was saying. Like they paid little or no heed to how Wisconsin’s history is the perfect counterargument to that kind of jaded thinking.

I wondered how such a gloomy outlook can be reflected in such bright eyes. I wanted to tell them, but didn’t, that they’re too young to be so cynical. I soldiered on, saying ethical standards in Wisconsin used to be so stringent that in 1978 a state senator from Kenosha by the name of Henry Dorman was criminally charged with misconduct in office for making a few personal calls on a state telephone.

The charge was eventually dismissed in court, but not by the voters. Dorman was defeated in a primary election that fall, ending his 14-year career. News accounts at the time emphasized that Dorman had been tainted by the “scandal.” A handful of phone calls not pertaining to state business were more than the citizenry could bear, an unacceptable misuse of public property. The invisible hand of our state’s political culture steered voters to throw the bum out.

I told the students these sky-high standards imposed by that bygone culture were slowly but surely eroded over the years. We now have a culture where money is king, where holding power takes priority over serving the public and solving problems, where re-election is everything. Some corrupt lawmakers have become lawbreakers, but the real scandal in our state and throughout America is what’s completely legal and totally within today’s cultural norms. The students didn’t look persuaded, but they didn’t look indifferent either. They looked helpless.

I recounted the same history to my older audience. They too asked questions until there was no time for more. Unlike the students, they did look persuaded. But there was this common theme in their comments and questions, a nagging doubt that they’ll live long enough to see meaningful change come about, ethical standards raised again, honor restored to public affairs. They sounded hopeless.

In neither audience did I see or hear evidence of apathy. How much they care—about what’s happening to our country, what we’re becoming—came through loud and clear. They just don’t believe there’s a damn thing they can do about it. This is the disease that afflicts them, the illness that’s infected so many in our society. This is what has young and old alike tuning out, turning away, avoiding the fray, curling up in a ball.

The cure for this powerlessness that ails us can be found in our own proud history, provided we have the wisdom and courage to teach it and the good sense to believe in it.