Karen A. Chase's Blog

November 11, 2025

Women in American Revolution: Agency, Coverture, and the Revolutionary War

As we honor Veteran’s Day today, let’s talk about women’s involvement in our founding and the Revolution. While researching women’s roles in the American Revolution for a historical novel, I became fascinated by primary sources showing young women working in trades or nurturing “expected” talents like needlework while family members discussed their futures. These moments capture a reality for countless colonial women—lives shaped by expectations, limited by law, yet filled with quiet resistance and remarkable agency.

The Legal Reality: Coverture and Women’s RightsWomen in American Revolution faced coverture, a legal doctrine where a married woman’s legal identity merged with her husband’s. Legal scholar William Blackstone wrote that “the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage.” Married women could not own property, make contracts, or control wages.

Yet historian Karin Wulf’s research in Not All Wives: Women of Colonial Philadelphia reveals the system was more complex than black-letter law suggested. Wulf argues that “unmarried women shaped the city as much as it shaped them.” Women arranged marriage settlements, conducted business as “feme sole” traders, and managed estates when husbands were absent. As Wulf notes, “The presence of unmarried women affected household arrangements, intense and emotional ties, and inheritance practices.”

When Duty Collided with DesireYoung women faced impossible choices. Marriages were arranged based on family connections, financial security, and social standing. Carol Berkin’s Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America’s Independence documents how the war disrupted these expectations.

Women “managed farms, plantations, and businesses while their men went into battle.” Yet Berkin notes the paradox: “Yet no matter how long her caretaking duties lasted, no matter how hard she labored in the fields…these actions did not blur the line between male and female.” Women’s contributions were often minimized within traditional gender roles.

Holly A. Mayer’s recent Women Waging War in the American Revolution (2022) brings together current scholarship examining women’s active participation across all social categories, emphasizing that creative activities often masked deeper longings for autonomy.

Women’s Agency During the Revolutionary WarThe war years disrupted traditional gender roles. Cokie Roberts’ Founding Mothers: The Women Who Raised Our Nation chronicles how women organized boycotts, raised funds, managed businesses, and even engaged in espionage.

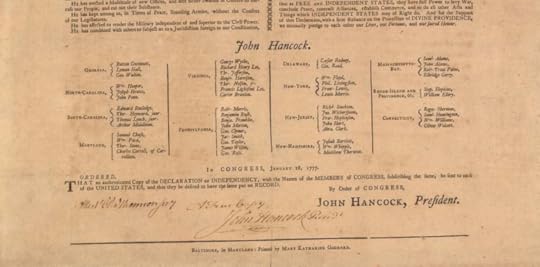

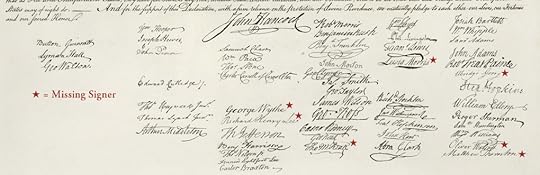

Consider Esther de Berdt Reed, who in 1780 penned “Sentiments of an American Woman” and organized the Ladies Association of Philadelphia. Reed led a door-to-door fundraising campaign that raised over $300,000 for Washington’s Continental Army—just weeks after giving birth to her sixth child. Or Mary Katharine Goddard, Baltimore’s postmaster from 1775-1789 and likely the nation’s first female federal employee. In January 1777, Goddard printed the first official copy of the Declaration of Independence bearing the signers’ names, typesetting her own name into history: “Baltimore, in Maryland: Printed by Mary Katharine Goddard.” (See image below.)

Berkin observed women transformed peacetime activities “into wartime activities, becoming the unofficial quartermaster corps of the Continental Army.” One British officer acknowledged: “If [we] had destroyed all the men in North America, we should have enough to do to conquer the women.”

These women demonstrated agency within restrictive legal frameworks. As one woman wrote during boycotts, “join with” in protest resolutions “implied independent decision making rarely displayed by ‘Ladies.'”

Needlework was one domain where colonial women could exercise creativity. Women used it to communicate—samplers included political slogans, mourning pieces commemorated loved ones, and coded messages hid in stitchery during the war. Working within acceptable feminine spheres, women found ways to influence outcomes. They couldn’t vote, but they refused to buy British tea. They couldn’t serve in legislatures, but they managed farms feeding Washington’s army.

The Personal Cost of Public ServiceThe Revolutionary War demanded sacrifices from women that history often overlooks. Women maintained households, protected children, and kept businesses solvent while managing wartime losses. Their service was essential, yet it brought no political rights. As Berkin writes: “The war for independence allowed, and often propelled, these women to step out of their traditional female roles for the briefest of moments…When the war ended, however, these women returned to their kitchens and parlors—and to the anonymity their society considered feminine.”

Lessons for TodayHow do we recognize women’s agency when legal systems denied it existed? How do we properly credit contributions when records were kept in husbands’ names?

These questions matter as we approach America’s 250th anniversary. Accurate history requires acknowledging the full complexity of women’s lives—their constraints and their agency, their sacrifices and their resistance. Women in the American Revolution made choices, took risks, and shaped history—even when the law pretended they didn’t exist.

A Question Worth Pondering for lineage groups: Recognizing Women PatriotsThis question of women’s agency has practical implications today for lineage organizations like the Daughters of the American Revolution. Current DAR guidelines state that when a married woman paid supply taxes or furnished aid to the revolutionary cause, patriot recognition goes to her husband because coverture law meant all property belonged to him.

This policy assumes women lacked agency—that they couldn’t make independent decisions about supporting the cause. Yet modern historians like Wulf, Berkin, and others have documented extensive evidence of women’s agency, even within coverture. Women ran businesses in husbands’ absence, made financial decisions, and actively chose to support the revolution.

For a women-centered organization, this presents a question worth pondering. If we recognize that women exercised real agency during the Revolutionary War—managing businesses, making political choices, and taking risks for the cause—should we reconsider how we grant patriot status to married women who demonstrably supported independence, even when legal documents bore only their husbands’ names?

Read the full novel, Carrying Independence, by purchasing an autographed copy. This deep dive focuses on chapter 17 of the novel, in which Susannah is stuck doing needlepoint while her mother outlines her future role as only a married woman. It sets the foundation for her ultimate growth through the freedom that war provided her—a time period in which she gained agency.

The post Women in American Revolution: Agency, Coverture, and the Revolutionary War appeared first on Karen A. Chase.

September 3, 2025

Hidden History: Continental Congress Secret Journals

When we think about the founding of America, we often picture dramatic moments like the signing of the Declaration of Independence or George Washington crossing the Delaware. But some of the most crucial work was quite hush hush—in shadows and secrecy. My favorite hidden history? The Continental Congress maintained not one, but two sets of official records during the Revolutionary War. The public journals for the Crown told one story. The “Secret Journals” told another entirely.

Charles Thomson: America’s Keeper of Secrets

Charles Thomson served as the only Secretary of the Continental Congress for its entire fifteen-year existence, from 1774 to 1789. While delegates came and went, Thomson remained the constant presence, faithfully recording debates and decisions that would shape the infant nation. His name was regarded as an emblem of truth, and in all the factional disputes of the Revolutionary period, his judgment was respected.

But Thomson held a responsibility that went far beyond typical record-keeping. He was trusted to decide which minutes of their meetings and decisions were recorded in the Secret Journal. This wasn’t just administrative discretion—it was a matter of life and death during wartime.

Why Two Sets of Books?The Continental Congress faced an impossible situation. As rebels fighting against the British Crown, they were technically committing treason with every decision they made. Yet they also needed to govern, conduct diplomacy, and coordinate military efforts. The Continental Congress, recognizing the need for secrecy regarding foreign intelligence, foreign alliances, and military matters, maintained “Secret Journals,” apart from its public journals, to record its decisions in such matters.

And yes—they actually called them the “Secret Journals.” Not the “Confidential Records” or “Classified Documents” or some other euphemistic title. Just the Secret Journals. The straightforward name tells us everything about the founders’ mindset: they knew they were doing dangerous work, and they weren’t going to pretend otherwise.

The public journals served multiple purposes. They kept colonists informed about congressional actions and demonstrated legitimacy to both supporters and skeptics. But they were also sent to Britain as required communications from what the Crown still considered its colonial assemblies.

The Secret Journals, however, contained the real business of revolution. Congress recorded all decisions regarding the Committee of Secret Correspondence in “Secret Journals”, separate from the public journals used to record decisions concerning other matters. These confidential records documented intelligence operations, foreign negotiations, covert supply chains, and military strategies that would have meant execution for anyone involved if discovered by British forces.

What the Continental Congress Secret Journals ContainedThe scope of activities hidden in these journals was remarkable. The committee employed secret agents abroad, conducted covert operations, devised codes and ciphers, funded propaganda activities, authorized the opening of private mail, acquired foreign publications for analysis, established courier systems, and developed maritime capabilities apart from the Continental Navy.

The Secret Journals covered the period from 1775-88 and included sensitive intelligence operations and foreign negotiations. They documented everything from arms procurement in France to intelligence gathering about British troop movements. The journals also contained records of financial arrangements that couldn’t be made public—payments to spies, funding for covert operations, and contracts with suppliers who needed anonymity for their own protection.

On November 9, 1775, the Continental Congress adopted its oath of secrecy, one more stringent than the oaths of secrecy it would require of others in sensitive employment. This wasn’t theatrical politics—it was survival.

The Weight of SecretsThomson’s role required incredible discretion and judgment. He had to determine which congressional decisions could safely appear in public records and which needed to remain hidden. After leaving office, he chose to destroy a work of over 1,000 pages that covered the political history of the American Revolution, stating his desire to avoid “contradict[ing] all the histories of the great events of the Revolution”.

This destruction of records represents one of American history’s great mysteries. What did Thomson know that he felt needed to remain buried? His decision to preserve the myths and legends of the Revolution rather than reveal the messy, complicated truth shows how heavy the burden of these secrets became.

The Secret Journals weren’t published until 1821, more than thirty years after the Continental Congress disbanded. None of the contemporary editions included the “Secret Journals” (confidential sections of the records), which were not published until 1821. By then, most of the original participants were dead, and the new nation was strong enough to handle the truth about its covert beginnings.

From History to Fiction: A Novelist’s Discovery

From History to Fiction: A Novelist’s DiscoveryWhen I was researching Carrying Independence, I knew my protagonist Nathaniel needed a cover story for his mission. I had already named him Nathaniel Marten, choosing his German-based name by reviewing birth/death/marriage records in the Pennsylvania area for the mid-1700s (nearly 1/3 of PA citizens were German).

During my deep dive on the Continental Congress Secret Journal entries, one particular entry caught my attention—a resolution about contracting with a “Mr. Mirtle” for importing goods. The language was formal, vague, and clearly designed to hide the true nature of whatever operation was being authorized.

The Declaration of Independence being engrossed,

and compared at the table, was signed by the members.

Resolved, That the secret committee be empowered to contract with

Mr. Mirtle for the importation of goods to the amount of thirty thousand

pounds sterling, at his risk, and fifteen thousand pounds sterling

at the risk of the United States of America, for the publick service.

That the marine committee be empowered to purchase a swift sailing vessel

to be employed by the secret committee in importing said goods.

Then I realized something incredible: Marten and Mirtle are both derived from Mars, the Roman god of war. My fictional character’s name and the name in this entry were a perfect historical coincidence. I could use this to give Nathaniel exactly what he needed for such a secret mission. An alias.

This discovery shaped how I wrote Chapter 14. I used the exact format and language style of authentic Secret Journal entries but inserted my fictional “carrying committee” and the mysterious Mr. Mirtle contract. The entry in the novel reads exactly like the real thing because it follows the actual patterns Thomson used when recording sensitive operations.

The beauty of historical fiction lies in these moments where research and imagination intersect. By grounding fictional elements in authentic historical practices, the story gains credibility while honoring the real experiences of people who lived through these extraordinary times. (It also allowed me to bring in the notion of Nathaniel taking the sailing vessel referenced here. Later in the novel, he hops on the ship The Frontier featuring a new fictional character—and one of my favorites—Captain Hugo Blythe.)

When Secrets Finally Came to LightFor decades after the Revolution, the Secret Journals remained exactly that—secret. The Continental Congress disbanded in 1789, but the confidential records stayed locked away. It wasn’t until 1821, more than thirty years later, that these hidden chapters of American history were finally published by Thomas B. Wait in Boston under the official title “Secret Journals of the Acts and Proceedings of Congress, From the First Meeting Thereof to the Dissolution of the Confederation.”

The timing wasn’t accidental. By 1821, most of the original participants were dead, and the United States was strong enough to handle revelations about its covert beginnings. The published Secret Journals revealed a four-volume treasure trove of intelligence operations, foreign negotiations, and military strategies that had been hidden from British eyes during the war.

Today, curious readers can explore these fascinating documents themselves through digital archives. The complete Secret Journals are available online, offering an unvarnished look at how the founders really operated when they thought no one would ever know.

Legacy of the Secret JournalsThe Secret Journals remind us that the founding of America wasn’t just about grand speeches and dramatic declarations. It was also about intelligence networks, covert operations, and the countless unnamed individuals who risked everything to make independence possible. For years, Thomson’s brain held the best record of what really happened in the Continental Congress.

These hidden records shaped American independence in ways we’re still discovering today. They reveal the Continental Congress as a sophisticated operation that understood the complexities of 18th-century geopolitics. The founders weren’t just idealistic rebels—they were strategic thinkers who built an intelligence apparatus that helped secure victory against the world’s most powerful empire.

The next time you read about the Revolutionary War, remember that for every public resolution passed by the Continental Congress, there may have been secret decisions recorded in Thomson’s careful handwriting. Some of those secrets changed the course of history. Others remain buried forever.

Read the full novel, Carrying Independence, by purchasing an autographed copy. This deep dive focuses on chapter 14 of the novel, which I am serializing for America250 via substack—read for free.

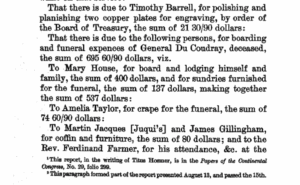

PS: A Secret Journal Entry about Women in the RevolutionWhile researching the Continental Congress Secret Journals, I stumbled upon another entry that perfectly illustrates how these records captured the human side of the Revolution. On page 804 of the Journals, there’s a matter-of-fact entry about reimbursing Mary House—the same innkeeper whose boarding house sheltered James Madison and other Virginia delegates—for “boarding and funeral expenses of General Du Coudray, deceased.”

General Philippe Charles Tronson du Coudray had been appointed “Inspector General of Ordnance and Military Manufactories” in August 1777, but

died shortly after arriving in America. Congress quietly reimbursed Mary House $400 for his board and lodging, plus $137 for “sundries furnished for the funeral”—a total of $537. The entry sits between payments for paper-making supplies and engraving work, as routine as any other congressional expense.

This small entry reveals something profound about the Revolutionary War experience. Behind every grand military appointment and strategic decision were real people—innkeepers like Mary House who opened their homes to foreign volunteers, provided comfort in their final days, and handled the practical necessities when death arrived unexpectedly. Mary House and her daughter Eliza Trist represent the countless women who supported the Revolution in ways that rarely made it into official histories. I proved Mary House as a new female Patriot for the DAR as part of my work on Eliza Trist’s life and journals, and entries like this in the Secret Journals provide rare glimpses into their vital contributions.

The Secret Journals captured these human moments alongside the covert operations, reminding us that the Revolution was fought and supported by ordinary people doing extraordinary things.

#AmericanRevolution #ContinentalCongress #CharlesThomson #SecretJournals #DeclarationOfIndependence #RevolutionaryWar #America250 #HistoricalFiction #FoundingFathers #CarryingIndependence

The post Hidden History: Continental Congress Secret Journals appeared first on Karen A. Chase.

August 20, 2025

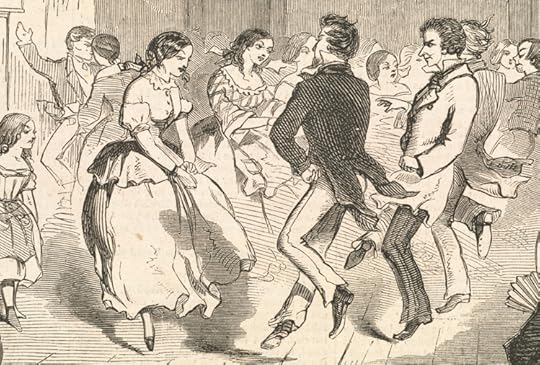

Revolutionary War Romance: Democracy on the Dance Floor

Imagine if your dating life depended entirely on how well you could navigate a complex series of steps while dozens of people watched your every move. Welcome to colonial courtship during the Revolutionary War, where the ballroom was both battlefield and proving ground for matters of the heart.

Imagine if your dating life depended entirely on how well you could navigate a complex series of steps while dozens of people watched your every move. Welcome to colonial courtship during the Revolutionary War, where the ballroom was both battlefield and proving ground for matters of the heart.

In Revolutionary War America, courtship dances weren’t just entertainment—they were elaborate social negotiations wrapped in silk and set to music. The way you moved, whom you danced with, and which dances you chose revealed everything about your social status, romantic intentions, and even your political leanings.

The contradance that Nathaniel and Susannah share in Carrying Independence perfectly captures this delicate balance. As Susannah cleverly explains to her smitten partner, the contradance was revolutionary in more ways than one. Unlike the formal French minuet, which kept couples of different social classes from dancing together, the contradance democratically mixed all participants.

The Minuet: Dancing with Your Own KindThe minuet represented everything aristocratic about European society. This elegant dance required extensive training, perfect posture, and careful attention to complex footwork. Most importantly, it was performed by only one couple at a time while everyone else watched—rather like a performance piece where your social grace was on full display.

Colonial families of means ensured their children learned proper minuet steps. The dance served as a public demonstration of good breeding and education. When you danced the minuet, you weren’t just moving to music—you were announcing your family’s social position and your own marriageability.

The English contradance changed everything. This lively group dance required partners to constantly switch, meaning a blacksmith’s son might find himself briefly partnered with a merchant’s daughter. Contra dances were fashionable in the United States and were considered one of the most popular social dances across class lines in the late 18th century, and unlike the minuet, country dances did not reinforce the established social hierarchy—in fact, they were democratic. The contradance created what Susannah calls “democratic” moments where social barriers temporarily dissolved.

The egalitarianism of country dance had reached its zenith during the Revolution, with the social mixing that had been a feature of the longways set in country dances allowing people of different backgrounds to interact in ways that would have been impossible in more formal settings. These dances featured long lines of couples facing each other, with intricate patterns that sent dancers weaving up and down the set. The music was faster, the steps more energetic, and the whole experience more communal. Instead of performing for an audience, everyone participated together.

A Modern Author’s DiscoveryWanting to learn exactly what a contradance was like so I could write this scene faithfully, I learned to do it myself. In my own town, I found a Regency-era contra dance group, and the experience taught me things no research could convey.

While democratic, I also learned two important things about this dance. First, it was a serious workout. Colonial balls were often all-night affairs that could last from seven in the evening until dawn, with guests attending all day and through most of the night, and many celebrations continuing three to four days. Individual country dances could go on for extended periods since they were described as “everlasting” because fresh dancers frequently cut in to continue until the musicians were exhausted.

Second, the democratic partner-switching could be uncomfortable if you were paired repeatedly with someone of questionable hygiene or unpleasant behavior. Dancing in the 18th century was a good way to discover if a partner had sound teeth, pleasant breath, good bearing, and was generally healthy—which meant the opposite was equally discoverable! The enforced intimacy of the contradance meant you couldn’t always escape an undesirable partner quickly.

Reading Between the Dance StepsColonial courtship required young people to become masters of subtle communication. A squeeze of gloved fingers during a turn, maintaining eye contact longer than propriety suggested, or requesting a second dance all carried meaning. The ballroom became a place where emotions could be expressed through carefully orchestrated movement. It was a place where women especially could express feeling through movement—an important asset when writing female 18th century characters.

Parents closely watched these interactions. A young man who danced too often with the same young lady might find himself facing questions about his intentions. Young women learned to use their fans, their glances, and their dance card choices to encourage or discourage suitors.

When Revolutionary War Meets RomanceThe shift from minuet to contradance mirrors the larger Revolutionary movement sweeping through the colonies. Just as Americans were rejecting British aristocratic traditions in politics, they were embracing more democratic forms in their social lives.

The contradance’s emphasis on changing partners and shared participation reflected emerging American values of equality and community cooperation. When Nathaniel tells Susannah he prays “democracy will sweep the colonies forevermore,” he’s responding to both her explanation of the dance and the larger political moment they’re living through.

The Jane Austen Connection I’m a Jane Austen fan, and so the dance scenes in Carrying Independence deliberately echo the romantic tension we see in Jane Austen’s novels and their film adaptations. Why? Austen understood that ballrooms were theaters of emotion—a place where glances, touches, and movements conveyed what words could not.

I’m a Jane Austen fan, and so the dance scenes in Carrying Independence deliberately echo the romantic tension we see in Jane Austen’s novels and their film adaptations. Why? Austen understood that ballrooms were theaters of emotion—a place where glances, touches, and movements conveyed what words could not.

The 2005 Pride and Prejudice film famously uses the dance between Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy to show their attraction despite their social differences. Similarly, Nathaniel and Susannah’s contradance becomes a metaphor for their ability to connect across class lines—even as larger forces work to keep them apart.

The Music of DemocracyColonial dance music evolved alongside the social changes. While minuet melodies were formal and restrained, contradance tunes were often based on popular folk songs that everyone knew. Fiddles replaced harpsichords, and musicians encouraged audience participation.

The six-eight time signature that Susannah mentions created a lilting, energetic rhythm that made the contradance feel more like a celebration than a formal exhibition. This musical democracy meant that anyone who could keep time could participate, regardless of their formal training.

Beyond the BallroomThe social lessons learned in colonial dance halls extended far beyond courtship. Young people practicing contradances were literally rehearsing democratic participation—learning to work together, share leadership, and adapt to changing patterns while maintaining harmony with the group.

These skills served them well when the Revolutionary War required colonists to work together across traditional social boundaries. The same spirit that made the contradance appealing prepared Americans for the collaborative effort of building a new nation.

The ballroom taught other valuable lessons too. Young people learned to read social cues, navigate complex etiquette, and present themselves effectively in public settings. These abilities proved essential whether you were courting a spouse or courting political support.

Modern EchoesToday’s dating apps and social media have replaced dance cards and calling hours, but the fundamental challenges remain the same. How do we signal romantic interest? How do we navigate social differences? How do we balance personal desire with family expectations?

Colonial courtship dances remind us that romance has always required careful choreography. The steps may change, but the human need to connect, impress, and find love through shared movement continues across centuries.

The democratic spirit of the contradance lives on in contemporary social dancing, from swing dancing to salsa nights, where strangers become temporary partners and social barriers dissolve in the joy of shared rhythm.

Whether you’re navigating a colonial contradance or a modern dance floor, the message remains the same: sometimes the most profound connections happen when we’re brave enough to step into the dance, put forth a hand, and see where the music takes us.

Read the full novel, Carrying Independence, by purchasing an autographed copy. This deep dive focuses on chapter 12 of the novel, which I am serializing for America250 via substack. Read for free here.

The post Revolutionary War Romance: Democracy on the Dance Floor appeared first on Karen A. Chase.

August 6, 2025

Revolutionary War Taverns: The Social Hearts of Colonial America

In Chapter 10 of Carrying Independence, Silas Hastings waits in the elegant confines of City Tavern, observing the fine dining around him while nursing a simple pint of cider. This scene captures perfectly what made Revolutionary War taverns the beating heart of 18th-century American life. Far more than places to eat and drink, these establishments served as unofficial town halls, business centers, post offices, and the primary venues where colonists from all walks of life gathered to share news, debate politics, and forge the relationships that would ultimately birth a nation.

The sheer number of taverns in colonial Philadelphia tells us everything about their importance to daily life. In 1776, there were more than 120 taverns, inns, and “ordinaries” in Philadelphia—not counting the illegal serving houses that operated without licenses. With an estimated population between 30,000 and 40,000 people, that amounts to roughly one licensed drinking establishment for every 250-300 residents. By comparison, modern Philadelphia has about one bar for every 1,000 residents, making colonial Philadelphia far more tavern-dense than today’s city.

This incredible density of taverns reflected their essential role in colonial society. Taverns filled multiple functions that we can barely imagine today. They served as the restaurant, the meeting house, the hotel, the post office, and the entertainment venue all rolled into one. If you wanted to read the latest newspapers, hear local gossip, conduct business, or simply socialize with both friends and strangers, the tavern was your destination.

How Colonial Taverns Actually FunctionedColonial taverns operated on a model that might seem foreign to modern bar-goers. Most served meals at fixed times around large communal tables, where strangers were expected to sit together and make conversation. The menu was limited—often just one option per meal—and prices were regulated by local governments. Travelers shared sleeping quarters, sometimes even beds, making privacy a luxury few could afford.

The tavern keeper held enormous social influence in their community. They were typically among the best-known people in town, often serving as postmaster since taverns functioned as unofficial post offices where letters and packages were collected and distributed. The keeper’s establishment was the busiest in town, and they made it their business to know every patron. Colonial tavern keepers were notoriously inquisitive, always eager to learn about their guests’ business and news from other towns.

The Changing Politics of Colonial HospitalityOne of the most fascinating aspects of colonial taverns was how they navigated the increasingly tense political atmosphere as revolution approached. In the early 1770s, many taverns served both colonists and British soldiers without issue. The White Horse Tavern in Newport, Rhode Island, for example, quartered both Loyalist and British troops during the British occupation of Newport during the American Revolution, especially during the Battle of Rhode Island in the summer of 1778.

However, as tensions escalated, tavern keepers found themselves forced to choose sides. When the British occupied Philadelphia in 1777, City Tavern’s innkeeper Daniel Smith welcomed them with open arms, and the tavern became the center for British officer recreation, including elaborate balls where local Tory women were entertained. But when the Continental Army reoccupied the city in 1778, Smith fled to England, understanding that his loyalty to the Crown had made him unwelcome in the new America.

This political shift reflected a broader transformation in tavern culture. What had once been neutral ground gradually became polarized, with patriot and loyalist taverns serving as organizing centers for their respective causes. The famous Green Dragon Tavern in Boston became known as “the headquarters of the Revolution” because the Sons of Liberty met there regularly, and it was where the Boston Tea Party was planned.

Women: The Unsung Operators of Colonial TavernsOne of the most surprising aspects of colonial tavern culture was the significant role women played as operators. In certain areas, up to 40 percent of taverns were operated by women, especially widows. Local magistrates, who had to award licenses before a tavern could operate, actually preferred widows who knew the business and might otherwise become a burden to the county if left impoverished.

Right here in Philadelphia, we see this pattern perfectly illustrated. Mary House owned and operated the House Inn on Second Street, just two blocks from the State House where the Declaration of Independence was signed. Her inn became a respected political hub, frequented by founding fathers who stayed there during their service in the Continental Congress. Mary’s daughter, Eliza House Trist, helped run the inn and it was there that she met Thomas Jefferson, forming a friendship that would last for decades. (In 2024, Mary House was recognized as an official “Patriot” by the Daughters of the American Revolution.) The House Inn demonstrates how women’s business acumen and hospitality skills made them natural tavern operators, even as society generally excluded them from other forms of commerce.

The Culinary ConnectionThe food served in colonial taverns varied dramatically by location and clientele. City Tavern, which catered to Philadelphia’s elite, offered what John Adams described as the “most genteel tavern in America” with fine wines and elaborate fare during the First Continental Congress. The tavern specialized in elegant dishes that would have included turtle soup, venison, elaborate meat pies, and imported delicacies that showcased the wealth and sophistication of its patrons. Of course, all this fine dining was accompanied by equally impressive libations—copious amounts of Madeira wine, rum punches, and ale that no doubt helped democratic discourse flow as freely as the spirits themselves.

However, this luxury existed alongside stark inequality. While businessmen and delegates feasted at establishments like City Tavern, common citizens struggled to afford basic bread in the markets. Many taverns provided glasses of rum for just a penny to alleviate the miseries of Philadelphia’s poor, highlighting the economic disparities that existed even as revolutionary ideals of equality were being debated just blocks away.

Modern food historians like Walter Staib, who recreated colonial cuisine when he operated the reconstructed City Tavern, have helped us understand what colonists actually ate. His research and cookbook work, featured in his television series A Taste of History, have revealed how tavern fare reflected local ingredients, seasonal availability, and the complex trade networks that brought exotic spices and imported goods to America’s tables.

My friends and amazing reenactors Bill Ochester and Steve Edenbo as Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson in the front pub at City Tavern.The Tavern as Democracy’s Cradle

My friends and amazing reenactors Bill Ochester and Steve Edenbo as Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson in the front pub at City Tavern.The Tavern as Democracy’s CradlePerhaps most importantly, colonial taverns served as early laboratories for democratic ideals. Churches or government buildings where hierarchies were strictly observed. Taverns were among the few colonial spaces where social mixing occurred across class lines. While the wealthy might dine upstairs in private rooms, the common room below buzzed with conversation between merchants, artisans, laborers, and travelers.

This mixing of social classes created unique opportunities for the exchange of ideas. Literate patrons would read newspapers aloud to their illiterate neighbors, spreading news and political opinions throughout the community. Debates about taxation, representation, and rights played out nightly around tavern tables, gradually building the consensus that would support revolution.

The tavern’s role in fostering democratic discourse cannot be overstated. These were spaces where ordinary colonists could voice their opinions and hear different perspectives. They could participate in the political conversations that were shaping their future. In many ways, the democratic ideals that would define America were not just debated in formal halls of government. They were lived and practiced in the everyday interactions that took place in taverns across the colonies.

When Silas Hastings sits in City Tavern in Chapter 10, he is observing the diners around him and plotting his schemes. He’s positioned in the perfect location to understand the pulse of revolutionary Philadelphia. The tavern wasn’t just a setting—it was the very foundation upon which American society was being built. One conversation at a time.

Read the full novel, Carrying Independence, by purchasing an autographed copy. This deep dive focuses on chapter 10 of the novel, which I am serializing for America250 via substack. Read for free here.

#CityTavern #RevolutionaryWar #AmericanRevolution #ColonialPhiladelphia #FoundingFathers #TavernHistory #America250 #PhiladelphiaHistory #ColonialLife #CarryingIndependence

The post Revolutionary War Taverns: The Social Hearts of Colonial America appeared first on Karen A. Chase.

July 23, 2025

The Missing Declaration of Independence Signers: America’s Contract

When we picture the Declaration of Independence signers, most Americans envision fifty-six determined patriots gathered in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776, solemnly affixing their signatures to the document that would birth a nation. This cherished image has been powerfully reinforced by John Trumbull’s famous painting, commissioned in 1817 and hanging in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, though the painting actually depicts the presentation of the draft on June 28, 1776—not the signing—and includes delegates who were never in the room together at the same time. (Plus the chairs and placement of the windows is incorrect, among other things.) But both this iconic artwork and our national mythology obscure one of the most precarious moments in American history—the weeks and months when seven crucial Declaration of Independence signers remained missing, threatening to unravel the very unity the document was meant to establish.

The truth about July 4, 1776, is far more complex than our national mythology suggests. While Congress approved the final text of the Declaration that day, the formal signing ceremony wouldn’t occur until August 2, 1776. Even then, seven crucial delegates were missing, scattered across the colonies by war, illness, and urgent state business.

This wasn’t merely a clerical inconvenience. In the 18th century, signatures carried profound legal and political weight. More than half the Congress consisted of lawyers and merchants who understood that without unanimous consent demonstrated through actual signatures, the colonies remained vulnerable to British divide-and-conquer tactics.

Why Unanimity Mattered: The Declaration as ContractThe stakes couldn’t have been higher. The Declaration of Independence functioned as more than a political statement—it was fundamentally a contract binding thirteen separate colonies into a unified nation. Without complete signatures, this contract remained legally incomplete, representing only a partial commitment to independence.

Britain understood this weakness and could exploit it by offering separate peace terms to individual colonies, potentially fracturing the fragile American alliance before it truly began. The Crown’s strategy had always been divide and conquer, and an incomplete Declaration provided exactly the opening they needed. Only through unanimous agreement—demonstrated by actual signatures—could the colonies ensure that King George III could not convince individual states that they weren’t truly bound together in common cause.

Here lies one of the most intriguing gaps in the historical record. Despite the enormous importance of completing the Declaration, surprisingly little contemporary documentation exists about exactly how those final seven signatures were obtained.

The Seven Missing Declaration of Independence SignersThe missing delegates weren’t random absentees—they included some of the most prominent leaders in the independence movement:

Richard Henry Lee (Virginia) – The very man who had introduced the Lee Resolution calling for independence was in Virginia helping draft his state’s new constitution. His absence was particularly ironic given his central role in initiating the independence movement.George Wythe (Virginia) – Thomas Jefferson’s former law teacher and one of the most respected legal minds in America was similarly engaged in Virginia’s constitutional convention. His expertise in constitutional law made his signature especially valuable.Thomas McKean (Delaware) – Was commanding militia forces in New Jersey alongside George Washington. McKean had cast the crucial deciding vote for Delaware’s approval of independence on July 2, making his signature essential for legitimacy. His situation became increasingly precarious as the war intensified. In his own words to John Adams in 1779, McKean described being “hunted like a fox by the enemy, compelled to remove my family five times in three months, and at last fixed them in a little log-house on the banks of the Susquehanna, but they were soon obliged to move again on account of the incursions of the Indians.”Elbridge Gerry (Massachusetts) – Was away managing critical war supplies and military logistics for his home state, duties considered essential to the war effort.Oliver Wolcott (Connecticut) – Was handling military affairs in Connecticut, including the famous melting down of King George III’s statue to make musket balls.Lewis Morris (New York) – Was with Gerry on military business, as New York faced immediate threat from British forces.Matthew Thornton (New Hampshire) – Wasn’t even elected to Congress until September 1776, making him impossible to include in any August ceremony. Thornton and Thomas McKean were the last signers.Each absence represented not just a missing signature, but a potential crack in American unity that enemies could exploit.

The men signed the document by colonies, south-to-north, with Georgia on the far left, and Connecticut on the bottom far right. However not all the names are in order. Matthew Thornton had no room to sign with Josiah Bartlett and others from New Hampshire.Congress Faces an Unprecedented Challenge

The men signed the document by colonies, south-to-north, with Georgia on the far left, and Connecticut on the bottom far right. However not all the names are in order. Matthew Thornton had no room to sign with Josiah Bartlett and others from New Hampshire.Congress Faces an Unprecedented ChallengeFaced with this crisis, Congress confronted an unprecedented challenge: how to secure the remaining signatures without compromising the document’s security or the safety of the signers.

The options were limited and fraught with risk. They could wait for all delegates to return to Philadelphia, but with war raging and state governments demanding attention, there was no guarantee when—or if—all would return. Alternatively, they could carry the original document to collect signatures, but this would expose the irreplaceable parchment to the dangers of 18th-century travel and potential British interception.

The Historical Mystery: How Were the Signatures Obtained?Here lies one of the most intriguing gaps in the historical record. Despite the enormous importance of completing the Declaration, surprisingly little contemporary documentation exists about exactly how those final seven signatures were obtained.

We know the basic facts: all seven missing delegates eventually signed the Declaration between September 1776 and early 1781. However, the historical record provides surprisingly little detail about exactly when or where these crucial signatures were obtained. Matthew Thornton, elected to Congress only in September 1776, signed in November when he first arrived in Philadelphia. Thomas McKean’s signature date remains the most disputed—historians believe he signed anywhere from 1777 to as late as 1781, with some evidence suggesting it could have been even later.

But the crucial question remains unanswered: were these signatures obtained when the delegates returned to Philadelphia, or was the Declaration carried to them? The historical record is remarkably silent on this critical point.

Evidence That Congress Wanted In-Person Declaration of Independence SignersSeveral factors suggest that Congress preferred delegates to return for in-person signing rather than having the Declaration carried to them. The physical arrangement of signatures on the Declaration shows careful planning, with spaces deliberately reserved for absent delegates. George Wythe’s signature appears at the top of the Virginia delegation, suggesting his colleagues anticipated his eventual presence in Congress.

The Continental Congress’s July 19, 1776 resolution ordered that the Declaration “when engrossed be signed by every member of Congress”—language that suggests a preference for signing to occur in Congress rather than elsewhere. Additionally, the ceremonial importance of the signing would have made in-person presence politically significant for such a momentous document.

However, wanting delegates to return and actually requiring it are different matters. The resolution doesn’t specify what should happen if delegates couldn’t return, leaving the crucial question unanswered.

However, other evidence suggests the possibility that the Declaration of Independence signers had it carried to them. Different ink compositions in some signatures indicate they weren’t all signed with the same materials used in the August 2 ceremony. Timothy Matlack had prepared consistent iron gall ink in Philip Syng’s silver inkwell for the formal signing, so variations could suggest signatures were affixed elsewhere with different materials. (Syng’s inkwell is in fact featured in Trumbull’s painting.)

The Continental Congress had already demonstrated sophisticated document distribution capabilities, having successfully circulated over 200 printed copies of the Declaration throughout the colonies. The infrastructure existed for secure document transport if the Declaration needed to be carried to absent delegates.

The Missing EvidencePerhaps most telling is what’s absent from the historical record. No contemporary letters, diaries, or official documents describe the logistics of obtaining these crucial signatures. For such a momentous undertaking, this silence is remarkable. Whether this reflects routine administrative processes, deliberate secrecy for security reasons, or simply lost records, we cannot know.

Thomas Jefferson’s July 8, 1776 letter to Richard Henry Lee mentions sending “a copy of the declaration” but provides no insight into plans for the original signing document or whether it might be carried to missing delegates. Continental Congress journals record that signatures were obtained but offer no details about the process.

A Nation Hanging in the BalanceWhat we do know is that for several crucial months in 1776, American independence hung by a thread. The Declaration that proclaimed the birth of a new nation remained legally incomplete. Its signers were unprotected by the unanimous commitment they had sought to establish.

This period of uncertainty reveals the fragile nature of the American experiment in its earliest days. The founders understood that without complete consensus, their bold Declaration might amount to nothing more than an ambitious document signed by a partial coalition.

The eventual completion of the Declaration’s signatures, however achieved, represented more than bureaucratic thoroughness. It marked the transformation of thirteen separate colonies into a unified nation, bound together by mutual commitment to independence and the radical principles the Declaration espoused.

The Enduring Historical LegacyThe period when the Declaration remained incomplete is a reminder that American independence was not achieved through a single moment of bold declaration. Instead, it was through months of painstaking work to build and maintain the unity necessary for survival. In our current era of political division, we need this reminder. It takes careful, deliberate effort required to forge a unified nation from diverse and sometimes competing interests.

Read the full novel, Carrying Independence, by purchasing an autographed copy. This deep dive focuses on chapter 8 of the novel, which I am serializing for America250 via substack. Read for free here.

#DeclarationOfIndependence #AmericanHistory #FoundingFathers #America250 #RevolutionaryWar #AmericanRevolution #HiddenHistory #IndependenceDay #1776 #HistoricalMystery

The post The Missing Declaration of Independence Signers: America’s Contract appeared first on Karen A. Chase.

July 9, 2025

When Home Becomes the Enemy: The Declaration of Independence Devastated Families

The summer evening of 1776 should have been like any other for Jane Marten. Smoke curled from her Pennsylvania farmhouse chimney, carrying the familiar scent of pork and beer stew. The towering Eastern Hemlock her father had planted cast its protective shadow across the porch where she often sat reading letters from relatives across the Atlantic. But when her son Nathaniel rode up that July evening with news that “Congress has declared independence,” everything Jane thought she knew about belonging shattered in an instant.

“Dear God. We are separated,” she whispered, sinking onto the stone steps as the weight of those four words crashed over her. “I still feel… I am English. Where does this leave me? Us?”

Jane’s anguish captures one of the Declaration of Independence’s most overlooked consequences: the nuanced emotional devastation visited upon families whose heritage suddenly marked them as potential enemies in their adopted homeland. When the Declaration of Independence was signed, it didn’t just create a new nation—it tore through the hearts of thousands of families caught between worlds.

![Cartoon showing a European gentleman with the Boston Port Bill in his pocket pouring tea down a [native American] woman's mouth. She is being held down by a lascivious gentleman at her feet and a judge at her arms. A woman holding a spear and shield covers her eyes while a gentleman holds a sword with](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1752151536i/37052498._SX540_.jpg) Graphic cartoons like this one published in 1774, vilified the British, and riled up Americans against those who still identified as English. Britannia weeps as Frederick, Lord North, pours tea into the mouth of America. She is held down, and about to be raped. A woman holding a spear and shield covers her eyes while a gentleman holds a sword with “Military Law” on it. Published in the Royal American Magazine, 1774, it was created by Paul Revere.The Declaration of Independence: More Than Political Separation

Graphic cartoons like this one published in 1774, vilified the British, and riled up Americans against those who still identified as English. Britannia weeps as Frederick, Lord North, pours tea into the mouth of America. She is held down, and about to be raped. A woman holding a spear and shield covers her eyes while a gentleman holds a sword with “Military Law” on it. Published in the Royal American Magazine, 1774, it was created by Paul Revere.The Declaration of Independence: More Than Political SeparationJane Marten embodied thousands of colonial women caught in an impossible bind when the Declaration of Independence was signed. Born in London but raised in Pennsylvania, she had spent decades building a life between two worlds. Like many English immigrants, she maintained deep emotional connections to family across the ocean while nurturing equally strong roots in American soil.

The Declaration of Independence didn’t just separate political entities—it tore through the hearts of families whose very existence bridged the widening chasm. Jane “devoured their regular missives like a starving stray,” treasuring letters from English relatives that she carefully stored in her family cookbook alongside recipes that sustained her American household. These women lived authentically in both worlds until the moment politics demanded they choose just one.

But here’s what made Jane’s situation uniquely heartbreaking: she faced not just the loss of her English identity, but the terrifying possibility of persecution for it. Her “pale, English skin” and refined accent—once sources of pride—now marked her as potentially suspect. Would neighbors who had shared harvest meals and helped birth her children suddenly view her as a threat? Would her husband’s gun shop, already under pressure to supply weapons for the Continental Army, face additional scrutiny because of his wife’s heritage?

When Heritage Became Liability After the Declaration of IndependenceThe Declaration created an atmosphere where decades of integration could be undone overnight. Families with English surnames faced whispered suspicions. Women with distinctive accents found themselves explaining their loyalty. Children caught between their parents’ heritage and their own American birth navigated questions about where their true allegiances lay.

Jane’s terror wasn’t unfounded. Throughout the colonies, families with English connections faced social ostracism, economic boycotts, and worse. The very traits that had once made them valued community members—their cultural knowledge, business connections, refined manners—suddenly became evidence of potential disloyalty.

This transformation of asset to liability creates a psychological trauma that reverberates through generations. When the place you call home begins to view your heritage as dangerous, the foundation of identity itself becomes unstable. Understanding these historical parallels helps us better comprehend today’s immigration challenges.

Declaration of Independence Legacy: Echoes Across CenturiesJane Marten’s anguish resonates powerfully today as American families navigate their own impossible choices between heritage and belonging. Across our nation, people with deep roots in their communities find themselves questioned about their loyalty based on their names, accents, or countries of origin.

Consider the mother whose children ask her not to speak their native language in public, fearing unwanted attention. Think of the small business owner who worries that his family name might hurt his livelihood when political tensions rise. Picture the college student who downplays her cultural heritage to avoid uncomfortable questions about her “real” loyalties.

Today’s policies increasingly emphasize isolation and deterrence, with new detention facilities built in remote locations where natural barriers provide security. Officials openly discuss using harsh conditions as deterrents, echoing the same psychological tactics used to pressure families like the Martens to prove their American loyalty through visible sacrifice of their English heritage.

The current climate has left millions of established Americans living in fear. Recent surveys show that 42% of Hispanic families worry about deportation affecting their loved ones, regardless of legal status. When heritage becomes a liability, the very diversity that strengthens our nation becomes a source of anxiety for those who embody it.

It’s easy today to think of immigrants as someone else, someone other than us. Yet, even for those of us with ancestors who were English, they were at one time immigrants, too.

The Declaration of Independence and Universal BelongingJane Marten’s story reminds us that the question “Where does this leave me?” transcends any single era or policy. It’s the cry of every person caught between worlds when politics demands impossible choices about identity and belonging.

Her Eastern Hemlock still casting shadows, her cookbook still holding those precious letters from England, her heart still breaking for the impossible choice between who she was and who she needed to become—Jane represents the human cost of political separation. She reminds us that behind every policy decision about immigration, citizenship, and belonging are real families facing real choices about how much of themselves they’re willing to sacrifice for safety.

The Declaration of Independence promised that “all men are created equal,” but Jane Marten’s tears that summer evening remind us that the path to that equality has always been more complicated for those whose very existence bridges the gaps between nations, cultures, and identities.

As we approach the Declaration’s 250th anniversary, Jane’s story challenges us to ask: How do we honor the promise of equality while protecting those whose heritage connects us to our shared humanity? How do we celebrate independence while ensuring that belonging doesn’t require the erasure of identity?

In Jane’s tears, we find both the heartbreak of impossible choices and the enduring hope that America might someday become a place where heritage enhances rather than threatens our belonging. Me too, Jane. Me too.

Illustration of a woman in mourning, leaning against a cemetery monument of stone. The woman is weeping. Behind her to reiterate her worries, is a weeping willow tree. The illustration was found in Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land-Warrant Application File W25373 for Francis Drew, New Hampshire.

Illustration of a woman in mourning, leaning against a cemetery monument of stone. The woman is weeping. Behind her to reiterate her worries, is a weeping willow tree. The illustration was found in Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land-Warrant Application File W25373 for Francis Drew, New Hampshire.Read the full novel, Carrying Independence, by purchasing an autographed copy. This deep dive focuses on chapter 6 of the novel, which I am serializing for America250 via my substack. Read for free.

Ready to explore more stories from America’s founding era? Visit carryingindependence.com to learn about the novel that brings these nuanced voices to life.

#DeclarationOfIndependence #America250 #ColonialFamilies #AmericanRevolution #HistoricalFiction #ImmigrantExperience #RevolutionaryWar #CarryingIndependence #FoundingFathers #IndependenceDay

The post When Home Becomes the Enemy: The Declaration of Independence Devastated Families appeared first on Karen A. Chase.

June 25, 2025

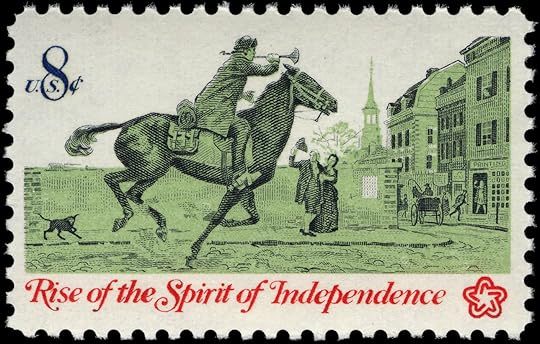

Revolutionary Colonial Post Roads: How 1776 Routes Became Our Modern Highways

This post corresponds with Chapter 4 of Carrying Independence—serialized for FREE on my substack.

When I was researching locations for Carrying Independence, I needed a protagonist who could believably navigate the treacherous colonial post roads of 1776 while carrying the most important document in American history. That’s when I discovered Berks County, Pennsylvania—one of the few counties without its own post office, making it the perfect home for an express rider like Nathaniel Marten who knew every twist and turn of the colonial post roads. But how did those roads come to be a part of our colonial postal system?

Why Some Counties Went Without Post Offices

In 1776, the colonial postal system was still developing under Benjamin Franklin’s guidance as Postmaster General. Counties like Berks relied on express riders because establishing post offices required sufficient population density, reliable local leadership, and most importantly, enough mail volume to justify the expense. Rural counties often depended on traveling riders who knew every trail, creek crossing, and safe haven along their routes.

The National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C. houses fascinating exhibits about these early postal pioneers, including an impressive leather portmanteau from the colonial era—one of the earliest mail carriers in their collection. While express riders typically used linen haversacks for regular mail delivery, riders carrying precious cargo like Nathaniel often switched to more durable leather bags that could better protect vital documents from rain, river crossings, and the general hazards of wilderness travel.

A Revolutionary-era mail bag as designed and created by colonial Williamsburg tannery for Bill Ochester, a Ben Franklin reenactor. Most similar to Colonial Post Road rider bags.

A Revolutionary-era mail bag as designed and created by colonial Williamsburg tannery for Bill Ochester, a Ben Franklin reenactor. Most similar to Colonial Post Road rider bags.From Footpaths to Superhighways

What makes the colonial post roads truly remarkable is their lasting impact on American infrastructure. Franklin’s postal survey teams carefully mapped routes that balanced efficiency with safety, creating pathways that would endure for centuries. The Boston Post Road, which connected Boston to New York, forms much of today’s Route 1. Similarly, the Great Indian Warpath through Virginia became portions of Interstate 81.

These weren’t random trails—they were strategically planned networks. Post riders marked trees with axe blazes to guide future travelers, creating the first standardized highway system in America. When you drive I-95 today, you’re following routes first traveled by riders carrying letters between distant colonies, slowly stitching together what would become the United States. You can view a full-size zoomable map of the below 1796 Post Roads map from Bradley is here, online at the Library of Congress map collection.

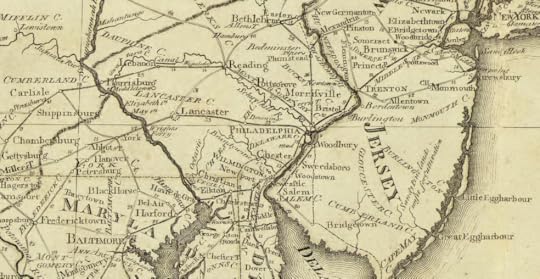

Colonial Post Roads closeup. 1796 map by Bradley.

Colonial Post Roads closeup. 1796 map by Bradley.The Skills That Made Express Riders Essential

Express riders needed extraordinary skills that went far beyond simply staying in the saddle. They had to read weather patterns, navigate by stars, identify safe river crossings, and maintain their horses’ health across hundreds of miles. Most importantly, they needed to be absolutely trustworthy—colonial merchants, political leaders, and families depended on them to deliver everything from business contracts to love letters.

In Carrying Independence, Nathaniel’s background as an express rider makes him uniquely qualified for his ultimate mission. His knowledge of post roads, his ability to survive in the wilderness, and his understanding of how to avoid detection all stem from his experience carrying mail through the Pennsylvania countryside.

Franklin’s Revolutionary Postal Vision

Benjamin Franklin revolutionized colonial mail service, but perhaps not in the way you might expect. As curator Daniel Piazza from the National Postal Museum explains in a fascinating Smithsonian article, the British crown originally established the colonial postal system without any intention of fostering resistance. However, “with the development of a postal network between the colonies, that facilitated communication and coordination between pockets of resistance that without this postal network might have remained more or less isolated.”

Franklin’s innovations included the first postal inspections, standardized postal rates, and the requirement that post riders travel day and night to speed delivery. But his greatest contribution may have been unintentional—creating a network that allowed colonial leaders to coordinate resistance, share ideas, and build the unity necessary for revolution. Rather than “stewing in their own little grievances” in isolated colonies, Americans could now “join up and make common cause” against British rule.

Today, we use our own communication routes to organize and unite. When we gather to vote or protest, we spread the word through social media platforms and text messaging—our modern equivalent of Franklin’s postal network. The principle remains the same: connecting people builds movements, though our messages now travel in seconds rather than weeks.

The postal service became more than a convenience—it was a unifying force. When colonial leaders needed to coordinate resistance to British policies, when merchants required reliable business communications, and when families wanted to maintain connections across vast distances, they all depended on riders like Nathaniel traveling Franklin’s carefully planned routes.

The Legacy of Colonial Mail

Next time you travel a major highway, consider that you might be following the same route that an 18th-century express rider used to carry news of independence. These colonial post roads didn’t just connect towns—they connected ideas, dreams, and the shared vision of a new nation.

The story of America’s postal service is beautifully preserved at the National Postal Museum, where visitors can explore everything from colonial-era mail bags to the Pony Express. It’s a reminder that long before the internet connected us instantly, brave riders like Nathaniel Marten carried the threads that wove our nation together, one letter at a time. You can also read more about my research on Colonial cartography in a previous blog, Navigating Historic Maps.

Discover more about Nathaniel’s journey in Carrying Independence by purchasing an autographed copy at or learn more about the novel at carryingindependence.com. This deep dive focuses on chapter 4 of the novel, which I am serializing for America250 via substack.

#ColonialPostRoads #AmericanRevolution #DeclarationofIndependence #RevolutionaryWar #America250 #FoundingFathers #BenjaminFranklin #CarryingIndependence #HistoricalFiction #Independence250

The post Revolutionary Colonial Post Roads: How 1776 Routes Became Our Modern Highways appeared first on Karen A. Chase.

June 18, 2025

No Kings: When Personal Loyalty Trumps Declaration of Independence Ideals

Loyalty Oaths and the American Revolution

Loyalty Oaths and the American RevolutionIn Chapter 3 of Carrying Independence, Nathaniel and his friends face a moment that echoes through American history: the pressure to sign an oath of allegiance. As evidenced by loyalty oaths that still exist from the American Revolution, allegiance was not to a specific leader, but to a country. To ideals. This scene resonates powerfully today as Americans grapple with recent “No Kings” protests across the nation, where millions demonstrated to defend Declaration of Independence ideals against what they view as excessive loyalty to a single individual rather than to democratic institutions.

The ideals articulated in the Declaration of Independence—that all men are created equal, that governments derive their power from the consent of the governed—weren’t just revolutionary arguments against King George III. They became America’s foundational promise, the principles we’ve adopted as our national ideals to uphold across generations. Yet here we are, nearly 250 years later, still fighting to honor that promise against the pull of personal loyalty.

The parallels between 1776 and 2025 are striking—and troubling.

The King’s Oath: Personal Loyalty as Political ControlRevolutionary-era oaths of allegiance weren’t abstract pledges to freedom or democracy. To sign an oath to the Crown was a deeply personal declaration of loyalty to King George III as an individual. British subjects swore to “be faithful and bear true allegiance to His Majesty King George the Third” personally, not to Britain as a concept or even to the Crown as an institution.

This wasn’t accidental. Personal loyalty has always been authoritarianism’s most effective tool. When you pledge allegiance to a person rather than principles, that person becomes the sole arbiter of what’s right, what’s legal, and what’s patriotic.

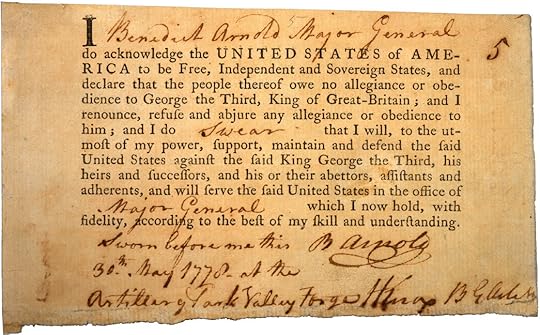

Thomas Paine understood this danger perfectly. In Common Sense, he wrote “that in America THE LAW IS KING. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King; and there ought to be no other.” This wasn’t just rhetoric—Paine and the founders deliberately chose a republic over direct democracy or monarchy, creating a system where representatives would be accountable to law and institutions rather than to personal loyalty. The Declaration of Independence ideals echoed this, rejecting personal rule and establishing that governments derive their power from the consent of the governed, not from loyalty to a monarch. (Even Benedict Arnold who flip-flopped signed an oath to the United States, shown above and here. Oh the irony of looking at this document in light of June 14th protests.)

When Party Becomes PersonYet here we are, nearly 250 years later, watching congressional leaders openly defer to presidential power rather than assert their constitutional authority. During a recent congressional recess in Anchorage, Senator Lisa Murkowski made a stunning admission: “We are all afraid,” she told constituents. “It’s quite a statement, but we are in a time and a place where I certainly have not been before, and I’ll tell ya, I’m oftentimes very anxious myself about using my voice, because retaliation is real.” This reveals how personal loyalty has again become the currency of American politics.

Trump has fundamentally transformed the Republican Party into one defined by loyalty to him, turning it against other major institutions in ways that echo the very system America’s founders fought to escape. When 61% of Republicans want their president to “stand up to” Democratic leaders even if it makes solving critical problems harder, we see the same dynamic that split colonial families: loyalty to a person superseding loyalty to the common good.

This isn’t partisan observation—it’s historical pattern recognition. The founders specifically designed our system to prevent exactly this concentration of personal loyalty around one individual.

The Cost of Choosing SidesDuring my research at Colonial Williamsburg and Yorktown, I watched reenactments simulate a moment in which representatives for the Crown and for the colonies demanded oaths be signed—respectively one for the King, and one for the Cause of Independence. To other reenactors the struggle was real, but to the modern tourists, the choice was clear. We would absolutely support ideals for the betterment of all over loyalty to and for a single man. And in part because we know how the Revolution ended—and on which side of history.

Yet that clarity came from historical distance. The colonists depicted in that scene had no such advantage. Research on charismatic authority explains how supporters accept a leader’s extraordinary qualities without question, creating what scholars describe as cult-like devotion—whether to a king or revolutionary leaders. But questioning that authority is how we actually came around to declaring our independence from a leader who no longer justly served the people.

Nathaniel’s conflict in Chapter 3 mirrors that original uncertainty. His English mother represents heritage and tradition; his father’s rifle-making supports the colonial cause; his friend Kalawi offers an entirely different perspective on the conflict. Must he choose one loyalty and abandon all others, and during a time of war?

“Who would he be aiming at exactly?” Nathaniel asks himself in a later chapter, capturing the profound confusion of someone caught between competing loyalties.

The revolutionary generation faced this impossible choice. Families split. Communities fractured. Neighbors became enemies. All because personal loyalty to either the King or revolutionary ideals and causes became the test of political legitimacy.

The Founders’ Warning in Declaration of Independence IdealsWhat would Thomas Paine say about Americans again debating loyalty to a single person? Perhaps he’d be stunned that we’re relitigating principles he thought settled in 1776. In Common Sense, he wrote of America’s potential to be “the glory of the earth”—not the glory of any individual.

The recent “No Kings” demonstrations, with their explicit rejection of monarchical tendencies, echo Paine’s central insight: free people don’t pledge allegiance to individuals. They pledge allegiance to ideas, institutions, and laws that transcend any single person.

Jefferson would perhaps have mixed reactions to our current moment. He’d be dismayed by institutional erosion, but perhaps proud of the “No Kings” demonstrations. When over 5 million Americans took to the streets in more than 2,000 cities to protest what they viewed as monarchical tendencies, they embodied the Declaration of Independence ideals—its core principle—that governments derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

Like the Declaration’s 27 grievances against King George III (nearly all of which begin with the word HE), the protesters articulated specific objections to individual overreach. While more than half of American voters elected Trump, more than 5 million on June 14th refused to accept personal rule over democratic institutions—exactly the kind of popular resistance Jefferson championed when he wrote in our founding document, “whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive” of the people’s rights, “it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it.”

The Choice Before UsThe characters in Carrying Independence didn’t have the luxury of historical hindsight. They couldn’t know that rejecting personal monarchy would create the world’s most successful democracy. They had to choose based on principle, not certainty.

We face a similar choice, but with the advantage of knowing where personal loyalty leads. We’ve seen democratic backsliding around the world when citizens transfer their allegiance from institutions to individuals. We’ve witnessed how loyalty tests and conspiracy theories can undermine democratic norms. Even President Zelensky understands loyalty is not unto himself. In his own inaugural address he stated, “We need people in power who will serve the people. This is why I really do not want my pictures in your offices, for the President is not an icon, an idol or a portrait. Hang your kids’ photos instead, and look at them each time you are making a decision.”

The question Nathaniel faces in Chapter 3 is this and it remains urgent today. What would compel you to sign an oath of allegiance, especially when it divides you from others? But perhaps we should be more clear: What would prevent you from signing such an oath? What should? What principles and ideals are worth more—and worth fighting for—over personal loyalty?

The founders answered clearly when 56 of them signed the sole copy of the Declaration of Independence: the principle that no individual should be above the law, that power belongs to the people, and that government exists to serve citizens rather than the other way around.

As we approach America’s 250th anniversary, the wisdom of 1776 feels both ancient and immediate. The choice between the Declaration of Independence ideals and our founding-vision of government by “consent of the governed” versus personal rule isn’t historical artifact—it’s the living challenge of every generation.

This post is a deeper discussion for Chapter 3 of Carrying Independence, my historical novel about the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It is part of my ongoing weekly chapter serial release—56 chapters FREE—in honor of our America250 Sesquicentennial on July 4, 2026. Join in and read the chapters on my substack: From the Wandering Desk of Karen A. Chase.

#AmericanRevolution #DeclarationOfIndependence #ColonialAmerica #America250 #HistoricalFiction #CarryingIndependence #1776 #RevolutionaryWar #AmericanHistory #NoKings #RepublicanIdeals

The post No Kings: When Personal Loyalty Trumps Declaration of Independence Ideals first appeared on Karen A. Chase.

The post No Kings: When Personal Loyalty Trumps Declaration of Independence Ideals appeared first on Karen A. Chase.

June 11, 2025

When Elk Ruled: Revolutionary War Pennsylvania Wilderness

In Chapter 2 of Carrying Independence, young Nathaniel Marten races across the Pennsylvania countryside to join his friends Arthur and Kalawi for an elk hunt on Topton Mountain. Their hunt represents not just adventure, but participation in an ancient relationship with the land—one that was changing by 1776. For readers of Carrying Independence, understanding this environmental history at the time of the Declaration of Independence—and the Revolutionary War Pennsylvania wilderness —adds depth to Nathaniel’s world.

First, there is no doubt that this scene is influenced by the opening hunting scene from the film Last of the Mohicans. Although, while those characters killed their quarry, I preferred my expert hunters miss, their hunt interrupted by shots not their own.

To write this scene faithful to the time period, I visited Kutztown and Topton Mountain while researching this novel. Along the way, I also learned a tremendous amount about elks—all for a handful of pages—so you, my dear reader, could envision Kalawi and Nathaniel’s lost wilderness.

These magnificent animals were truly massive—historical records indicate they frequently weighed 1,200 pounds and stood 17 hands (5 feet 8 inches) at the shoulder—far larger than modern Rocky Mountain elk. Unlike today’s carefully managed wildlife populations, colonial elk moved in herds that could number in the hundreds.

Farmers considered them agricultural disasters. A single herd could destroy an entire season’s crop in one night, trampling cornfields and devouring newly planted vegetables. The Pennsylvania elk were part of the Eastern elk subspecies (Cervus canadensis canadensis), which ranged from Georgia to southern Canada and from the Atlantic coast to the Great Plains.