Janice Pariat's Blog

September 15, 2016

WordPress Resources at SiteGround

WordPress is an award-winning web software, used by millions of webmasters worldwide for building their website or blog. SiteGround is proud to host this particular WordPress installation and provide users with multiple resources to facilitate the management of their WP websites:

Expert WordPress Hosting

SiteGround provides superior WordPress hosting focused on speed, security and customer service. We take care of WordPress sites security with unique server-level customizations, WP auto-updates, and daily backups. We make them faster by regularly upgrading our hardware, offering free CDN with Railgun and developing our SuperCacher that speeds sites up to 100 times! And last but not least, we provide real WordPress help 24/7! Learn more about SiteGround WordPress hosting

WordPress tutorial and knowledgebase articles

WordPress is considered an easy to work with software. Yet, if you are a beginner you might need some help, or you might be looking for tweaks that do not come naturally even to more advanced users. SiteGround WordPress tutorial includes installation and theme change instructions, management of WordPress plugins, manual upgrade and backup creation, and more. If you are looking for a more rare setup or modification, you may visit SiteGround Knowledgebase.

Free WordPress themes

SiteGround experts not only develop various solutions for WordPress sites, but also create unique designs that you could download for free. SiteGround WordPress themes are easy to customize for the particular use of the webmaster.

December 13, 2014

Infinite Heart

When I was twelve I fell in love with Amanda. She played basketball, had a chic (for the ‘90s) ‘mushroom’ haircut, and the widest, most gleeful smile. Stricken by indecision even then, I faithfully divided my affection between three others—Joyce, Feli, and someone whose name, decades on, utterly fails me. I wasn’t alone on this tender tour de force. At my convent school in Shillong, girls had crushes on other girls (usually their seniors) all the time. ‘Fans’ they were called coyly, and while some of us kept these sentiments secret, hoping to be bestowed a passing smile, others were more emboldened. They’d make their pronouncements in cards and letters, couriered via their juniors. (I was one for my sister.) I doubt the nuns had an inkling all this passion was running undemurely through their corridors, but if they did, they avowed patient silence. While I didn’t stay on long enough at the convent school to boast my own fandom (as if. My sister was much cooler and more popular), this memory has long stayed with me. Last year, at the Internazionale a Ferrara, on a panel on Indian literature, the moderator asked why my fiction so often featured ‘young love’. I replied that I was intrigued by its pliability at an age before certain cultural boundaries become tangible, when affections are directed by spontaneity, not after we have imbibed gendered notions on who we’re meant to be attracted to. Now, I‘d add that attraction and love, at any age, is (and should be allowed to) be as unanchored. As Kate Bornstein, author of Gender Outlaw, explains, if our sexual orientation must translate into an enclosing boundary which rigidly determines our gender (such that heterosexuality perforce distinguishes ‘men’ and ‘women’), we’re cheating ourselves of a searching examination for a richer, more fulfilled life.

I later attended a co-educational residential school where, before my eyes, gender was ritually polarised. Suddenly, there were boys, and strict lines of demarcation. Hostels, dining rooms, playing fields, swimming sessions, neatly separated into two. It was acceptable only to be enamoured by someone from across the lines of control. Within the hostels whisperings flew around—‘do you know, she’s lesbo…he’s gay’—based on little more than youthful ignorance and ill-judgement. I remember being silent about ‘fans’, and wondering why the language to describe them differed so vastly, why one was said with giggly nonchalance, and the others with scorn and derision, even a trace of fear. In places like these, gender is ‘learnt’. And after, it usually ceases to be questioned. Soon enough, I had a crush on a boy, sweet and shy. We’d take long, awkward walks around the sports grounds, hold hands in Hindi class. ‘Fans’ became something I didn’t often mention. Not through school, nor even while studying and then working in Delhi.

Queerness, as ‘lived’ experience, didn’t involve me again deeply until recently. During my time in the UK these past few years, I was fortunate to meet people—two in particular—who continually, and quietly, challenged dominant ideas of gender. While at SOAS, a flatmate and I shared a kitchen and a love for Jeanette Winterson. Over endless cups of tea, many discussions ensued on homelands, loves, and literature, particularly around Winterson’s Written on the Body with its nameless, genderless narrator. Was it important for these specifics to be clarified? No, we concurred, for it bolstered the idea of gender as spectrum rather than fixed polarities. As an experience of immense fluidity. What was also important was the negotiation of that spectrum. My flatmate told me about a transgender club in nearby King’s Cross that offered spaces—make-up and ‘changing’ rooms—to enable the transition from whoever you are outside to whoever you long to be inside. Gender, far from being fixed and stable, is tentative. What draws and entices us evolves and changes, our identity is constantly in the process of ‘becoming’. The more welcoming an environment is to these negotiations, the more conducive it is to a flourishing of queerness. It becomes greater with our ability to experience boundaries as invitations, rather than walls to be stringently policed.

This discussion was enlarged and enlivened one evening when I accompanied a friend with an extra ticket to Steve McQueen’s Shame. When it turned into a late-night discussion of the movie’s treatment of addiction, sex, personal boundaries. Over a bottle of some truly dreadful corner shop wine (thankfully not the same vintage over which we were later engaged), we talked of how the stringencies of ‘purity’—what’s considered ‘normal’, conventional, correct—were also markers of cruelty. And how this applies to everyone. A friend, he said, who was dating a transgender woman, felt increasingly awkward about the polarity of roles that informed even such a seemingly unconventional relationship. I told him about another who confessed that she’d been accused by a ‘real’ lesbian of being deceptive because she was also attracted to men. To draw the paradoxes even further, then, an overturning of such boundaries of purity can even be a marriage to someone you love, because you love them, rather than because they’re of the ‘correct’ gender to be betrothed to. Given I was in the UK at the time, where unions between people regardless of biological sex are recognised, this was a matter of personal choice. Which leads me to the dangers of state-sponsored moral gatekeeping that offers protection and recognition only to unions of one kind, standing in the way of simply being who you are, with whom you love.

I’ve been asked whether Seahorse was written in response to Section 377 being reinstated in India in November 2013. But it began long before, as a story simply about love. I started working on the novel with the idea of setting a ménage à trois in Delhi, but the seasonable purchase of Robert Graves’ Greek Myths shaped it into the retelling of the story of Poseidon, the god of the sea—like all the others, hugely promiscuous, gender indiscriminate—and his faithful lover and devotee Pelops. We follow Nem through a year in Delhi University, in love with an older art historian, and later in London, where he and his friends mingle with ‘gender outlaws’. Seahorse is not a book about queerness, rather it is a book that treats queerness as a way of being that is accessible to everyone. As something that you may simply happen to walk into. It was inspired by the wealth of experiences unfolding before me, and the increasingly wider circles of people I encountered, all nonconformists in their own ways. Some in relationships of polyamory or ‘many loves’, the practice of being in more than one intimate relationship with the full consent and knowledge of all partners. (If gender is about roles and expectations, polyamory customises that in significant ways.) Others who were transgendered. Some who continually shuffled the props of gender by cross-dressing. Through a common friend, I met S—, a beautifully effeminate biological male who would decide every morning, in front of his/her wardrobe, whether, that day, he/she felt more inclined to be a man or a woman. Gender is as discardable as clothes.

It’s something I wish I could tell my thirteen-year-old self.

Yet writing this book prompted, in many ways, a new ‘coming out.’ Revisitations to past emotions. And a joyful reinstatement. We, all of us, are free to love our Amandas.

This piece first appeared in Elle magazine (November 2014)

December 6, 2014

The Gift of Stories

I heard my first stories from a woman who couldn’t read or write.

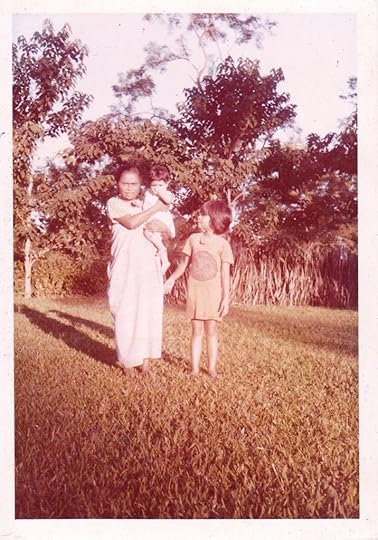

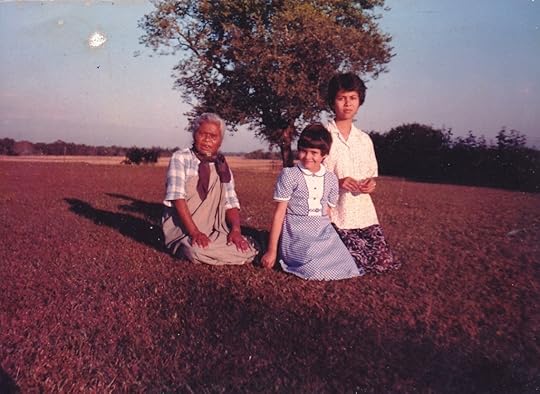

A small, stout lady with a soft, full moon face ringed by silver tresses. Dark once, always worn in a bun, fat, plump, perched on the back of her head like a dinner roll. The colour of her hair might be the only thing that’s changed dramatically over the years; her face, as far as I can remember, has always been intensely lined. A coastal shelf of experience.

My nanny (‘kong’ in Khasi), Stian Kharwar, or lovingly called Oiñ, has been with, or rather, a part of, our family for almost forty years. She is from Mawkyrwat, a town in the southwest of Meghalaya, about fifty kilometres outside Shillong. Once, she confided in us, she nearly chucked a cauldron of boiling water on her violent, abusive husband who was lying inebriated on the bed.

‘And?’ we asked, holding our breath.

She shrugged her tiny shoulders. ‘He wasn’t worth the trouble.’

So she packed up her things and children, and left instead. Joining, on her travels, a Punjabi family with a young son who she helped bring up. A few years later, through a common acquaintance, she was recommended to my parents, posted at the time at Koomsong, in Upper Assam. The story goes that my perpetually cranky three-month-old elder sister stopped crying as soon as she lay in Oin’s arms, and my exhausted mother hired her on the spot.

Soon enough, I came along, and Oin’s patient love awaited me too.

Despite growing up amidst my father’s frequent transfers from one estate to another, I consider Harchurah my longest-lasting ‘home’, brimming with childhood memories. Located about an hour from the (then) small town of Tezpur. We lived in a bungalow perched on a section of high ground that overlooked a vast spread of paddy fields, visited occasionally by herds of elephants and rhinoceros. The garden was my playground—gigantic red-blossom gulmahurs, a sand-pit, bird bath (which I dutifully replenished daily), a grove of carambola trees, a lichee tree by the swimming pool whose summer fruit-laden branches would sweep the surface of the water, rows of spectacular papery bougainvillea. Oiñ had her own little house by the back gate, and I’d visit her there, pestering her for stories and chicken curry.

‘Her food is better,’ I’d reply (with the candidness of youth) when my mother enquired about my routine absence from the dining table. In truth, it was. The curry made in its simplest, most fuss-free form, generously ladled over a mound of steaming rice. We’d eat, I remember, with our hands. And then lie on the bed, the afternoon heavy and muggy around us.

‘Tell me that story, Oiñ,’ I’d say, ‘the one about nongshohnoh.’ The Khasi version of the bogeyman. Or, more often, about the ghost.

‘What ghost?’

‘The one that saved me.’

‘When you were very small…’

‘How small?’ I’d ask, although I already knew.

‘When you were less than a year old, you fell ill, with a fever. But your parents and sister were away in Cherrapunjee, to attend your great-grandfather’s funeral. You were on the bed, and I was dozing on the chair…I don’t know if it was a dream, but a woman in a black jaiñsem stood at the door and asked for you…Give her to me, give her to me, she said…’

‘And then?’ This was my favourite part.

‘And then I saw your great-grandfather, he crossed the room…he was a doctor, you know…and when I woke up and checked you, your fever was gone.’

I’d shiver, with fear and excitement. Clutching at my personal sliver of magic realism. This was how Oiñ narrated her stories, unabashedly poised between the mundane and fantastic, fact and memory—what transmuted, years later, into Boats on Land. Looking back now, I see she gifted me orality, a life-long reminder that stories exist far beyond text and pages. That they are there for the taking, ready to be rediscovered, retold through my own voice. My interest in forms of story-telling lead me from the spoken to myth, our most ancient, iconic forms of making sense of the world. How they offer us the precision of behavioural patterns, an atavistic map of human nature, changeable, and constant, as the sea.

She also imbedded in me a mild, irrational fear of ladies in black jaiñsems.

Sometimes, when I’d been especially naughty as a child—bringing a goat into my bedroom concerned it might be cold outside; on other occasions, a calf, or a favourite chicken—she’d mutter menacingly, ‘I should have listened to that woman.’

Oiñ was a bit of a troublemaker herself. Like many Khasis, she’s particularly fond of ‘khana’ or telling stories, and not just the harmless, childish kind. Tea estates are compact, self-contained worlds punctured routinely by gossip and rumour, which Oiñ did well to generously spread and gather. Strolling around the place, in her chequered jaiñkyrshah, collecting scandal that she’d pocket like coins for her purse. She considered our cook, fondly called ‘Babarchi’, her real-life ‘frenemy’—sometimes confidante, more often bête noire—until my mother would intervene.

‘No more of this, Oiñ,’ she’d say, her chides rapidly turning to pleas.

And Oiñ would turn wide, wounded eyes toward her, proclaiming irrefutable innocence.

Often, though, we were partners in mischief.

‘Do your holiday homework,’ I’d be instructed, before my parents left for a party. As soon as they were out the door, I’d flick the television on with Oiñ’s enthusiastic approval. Doordarshan (apart from Chitrahaar) was usually deemed boring, but we owned a single Hindi movie VHS tape, that we’d happily watch infinitely. I remember little from Aradhana (1969) apart from the “Mere sapno ki rani” song sequence—with Rajesh Khanna in a jeep following Sharmila Tagore aboard the toy train winding up to Darjeeling—and Oiñ gleefully chortling during the fight scenes.

My favourite memory of Oiñ from those days was when my sister taught her to read and write Khasi. I remember her lined notebooks, the patiently rendered alphabet—it amazed me, all of seven, that a grown-up found them as exhilarating and infuriating as I did. She’d follow, with a finger, the lines in poetry and ‘khana’ texts my parents bought her, slim volumes printed by Ri Khasi Press in Shillong. Soon, she could read the Bible. She would write us letters while we were away in school. In English, she knew how to say ‘I love you’, and insisted she didn’t need to know more. When I visited her recently in Mawkyrwat, I found, beside photographs of my sister and I, these books, untouched now because the doctors advised against the operation that would remove the cataract slowly impairing her sight. She’d sounded forlorn on the phone—‘When will you come? My legs are no good’—but was overjoyed and feisty when we met.

‘Do you go to church?’ she asked sternly.

‘Yes, of course,’ came my pat reply.

She blinked—‘Liar,’ she accused—and we both burst into laughter.

Where she lives, she is surrounded by a gaggle of grandchildren, grand nephews and nieces, little children running in and out of the lime-washed rooms. I hope they too listen to her stories. Before we left, I hugged her tight, and said, in response to her utterance, ‘I love you too.’ All the words I need to know came from her.

This piece first appeared in Vogue (November 2014)

Leit suk Oiñ

2nd January 1930 (circ.)—6th December 2014

October 31, 2014

October 23, 2014

Dark Numbers

1) The Bezbaruah committee, that was set up to probe the rise in hate crimes against people from the northeast, found the incidence of such crimes to be the highest in Delhi. Why Delhi? From your experience, can you think of any reason why it is worse in Delhi than in other metros?

In criminology, there is the notion of “dark number”. This is the number of actual crimes committed, only a small number of which actually get reported. If the committee based their findings on official data, the reason that Delhi falls under the spotlight might simply be because it is the Indian capital, which is subject to more intense scrutiny by civil society and hence might be witnessing a higher number of hate crime reports. I prefer this explanation to the alternative, i.e. that there is something particularly wrong with Delhi-dwellers. An accusation of this sort, in fact, would be guilty of the same reasoning that makes people hostile towards “foreigners”, seen as a homogeneous, faceless group that deserves no respect. In fact, if my experience has taught me anything it is that it’s very important to respond to the simplification and stereotypes that drive hate crimes not with other typifications and faceless categorisations that chastise some and absolve others.

2) What do you think can be done to stop such violence from recurring?

Hatred towards people with a different skin colour, a different accent, a different culture, a different language is a constant problem in human relations. One of the rising parties in the UK, the UK Independence Party, is winning consensus precisely by blaming many of the problems that have been gnawing at Britain (such as widening inequality brought about by the London-centrism of Westminster governments, by the elitism of an Oxbridge-educated political class as well as by rampant privatisation of public services) on Eastern European immigrants. Racism, then, is not just an Indian problem, nor just a Delhi problem.

It is something that comes whenever people cannot embrace diversity. And diversity, for better or for worse, is something of which India has an abundance. The idea that you can traverse a city like Delhi or Bangalore and speak three to four different languages is unheard of in many parts of the world. The challenge this poses, then, is not so much to try and distil some purist and simplistic identity (around language, religion down to dress and appearance as in Nido Taniam’s case). But, rather, to try and embrace difference, starting from the everyday. On this, I am more hopeful about civil society initiatives than about formal government intervention. This is because many post-colonial states, of which India is one, have often become the bone of contention of different cultural or communal groups to assert their pre-eminence over others, thereby being part of the problem. The massacre of the Tutsis in Rwanda is perhaps the most glaring example. But India is no stranger to cases of government indifference towards violence against this or that group of supposed “undesirables” (like the Sikhs in Amritsar, or the Muslims of the Gulbarg Society). The best way I see to achieve this is to build alliances and grow an awareness of the dynamics at play in the game of insiders/outsiders.

When I first wrote my piece on Delhi, some responded saying that I had no right to complain, given the discrimination that “dkhars” are subject to in the North East. To that I reply that, instead of making me indifferent to the violence at home, my experience in Delhi makes me even more eager to listen to and speak out against the same treatment directed at other people who are treated as “foreigners” in what is my home state. And, more generally, it has made me more aware of the many dividing lines that are policed throughout India, not just on an Indian regional basis, but also on grounds of migrant status as well as caste. All these problems hold together, because if we learn to accept and appreciate, we learn to appreciate everything and everyone. If we learn to divide, on the other hand, there is no end to the borders we may build amidst ourselves.

October 1, 2014

Poem in October

My birthday began with the water-

Birds and the birds of the winged trees flying my name

Above the farms and the white horses

And I rose

In rainy autumn

And walked abroad in a shower of all my days.

— Dylan Thomas

September 26, 2014

Happy Birthday, TS Eliot

“You gave me hyacinths first a year ago;

They called me the hyacinth girl.’

—Yet when we came back, late, from the Hyacinth garden,

Your arms full, and your hair wet, I could not

Speak, and my eyes failed, I was neither

Living nor dead, and I knew nothing,

Looking into the heart of light, the silence.

Od’ und leer das Meer.”

— TS Eliot, The Wasteland

September 9, 2014

September 7, 2014

Deleted Scene

“A deleted scene refers to footage that has been removed, censored, or replaced in the final version of a film or television show.” In this case, my novel, Seahorse. I’d written this paragraph in its earliest draft, and it survived until final edits, shuffled here and there, tweaked and polished. And then it had to go. “Suggest cutting to make it more brisk,” marked my editor. Yet I felt a little sorrowful to hit Delete. So it’s gone from the manuscript. Here it has its own space.

“Long train journeys always remind me of the first one I took from my hometown to Delhi. Standing at the station bidding my parents farewell. My mother suddenly quiet. My father briefly placing his arm around my shoulders just before I stepped into the carriage. It was the single most exhilarating journey of my life—across the plains of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. I’d been ensconced within the shadow of landlocked hills, and the view of a limitless horizon offered me a glimpse of freedom I’d never imagined. In those days—this was the late 1990s—few economy airlines ran in India. Those who could afford it flew Indian Airlines or the new Jet Airways. The rest took the train. As ever, looking back now a decade or more later—which if you think about it, isn’t very long—I am surprised by slowness. And I think of that journey, two days to Delhi in a rattling, lurching carriage that didn’t smell all that fresh, as a rite of passage. As my small odyssey. The world has no epics now because it doesn’t undertake long journeys. By ship. By carriage. On foot. From one airport terminal to the other, people reached destination after destination with little sense of having moved or been transformed.”

Image from Vanessa Fire