Daniel Chamovitz's Blog

April 2, 2023

Screaming plants

11 years ago I posted this April 1st blog about plants screaming when cut by a lawnmower http://whataplantknows.blogspot.com/.../screaming-plants...

Some (including close friends) fell for it and I was even tracked down to be interviewed about the science, which led me to emphasize that this was an April fool's joke!But now we have our first evidence for "screaming" plants!Now my friend and colleague Prof. Lilach Hadany at Tel Aviv University published yesterday a landmark paper in CELL that shows for the first time that plants emit sounds that carry biological information!: https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(23)00262-3

Here for example is what a tomato sounds like is it doesn't have enough water:thirsty tomato

And this is what a grapevine sounds like after being cut:Grapveine after being cut

I'm proud to have has an influence on this research as its roots (all pun intended) can be traced back to my discussions with Lilach while I was writing What a Plant Knows.

So this is NOT an April Fool's hoax. Plant's do emit sounds (But they don't scream

)!

)!

January 27, 2021

Combatting Plant Blindness

Tu Bishvat, the Jewish Arbor Day is a call against "plant blindness". When I say "plant blindness", I'm not referring to a plant's visual acuity. Plants are anything but blind. While plants may not see in pictures like you or me, they are acutely aware of the surrounding light in their environments. Plants discern between blue and red light, and use this information to know which direction to grow. Your plants on the windowsill bend to the sunlight so that they can absorb the light needed for photosynthesis, the energy-producing metabolism of the plant. Plants actually know how to measure the length of the night, the period between sunset and sunrise. Plants differentiate between the ever-dimming scarlet light of sunset, and the brightening orange light of sunrise, and use this information to determine when to flower.

"Plant blindness" relates less to the plants' abilities, as it does to ours: we are often blind to plants.

That's not to say that we don't see plants. We see them all around us: Arazim and Orenim in the forest, grass in our lawns, shkadia blossoms in harei jerusalem, and rakafot and calaniot in the field. We see miles of wheat fields as we drive south on Route 6. While we see plants as passive objects in our visual landscape, we are blind to their complexity. The static plant world we experience belies a dynamic plant community that includes perception, communication and complex information processing.

Why are we blind to the complexity of the plant world? First, plant movements, with the noted exception of a few rapid movers such as the Venus Fly Trap, occur over long timeframes – too slow for our impatient eyes. Leaves slowly move up and down in response to changes in temperature and light; stems dance in various shapes ranging from circles to figure 8s, but only over a course of several hours, so that only though time-lapse photography do we discern these purposeful motions that characterize the plant world.

Second,we see only half of the plant world – the stems, leaves and flowers. Underground, the other half of the plant world, the roots, are continuously exploring, probing the soil for nutrients, signs of water, and differentiating between friend and foe. The roots of some species are so advanced that they grow away from their cousins, but will grow over, and steal resources from roots of another species!

So to combat plant blindness in humans, we have to learn to appreciate the complexity we can't see. We need to learn to see the beauty in the thousands of meticulous scientific studies which have elucidated the ways plants sense their environment, whether by seeing light, or smelling their neighbors, or listening to insects.

And why should plants be so complex in their abilities to sense the environment? To survive. As opposed to us, plants are literally rooted in one place. They can't escape their environment. Humans and other animals respond to hostile environments by running away, by seeking out more hospitable conditions. Plants can't run away from stress. Held in place, they must suffer extreme changes in temperature, drought and flooding, strong winds, and insect infestations. Their survival is not based on the ability to escape, but rather to adapt. Thus plants have to be very aware of changes in their environment so that they can quickly respond and survive.

Yes plants are acutely aware of the world around them. They are aware of their visual environment. They are aware of aromas surrounding them and respond to minute quantities of volatile compounds wafting in the air. Plants know when they are being touched and they are aware of gravity – they can change their shapes to ensure that shoots grow up and roots grow down. And plants are aware of their past – they remember past infections and the conditions they’ve weathered, and then modify their current physiology based on these memories. And most importantly they integrate all this diverse information to yield a plant exquisitely adapted to its current environment.

We need to appreciate a plants' complexity, because there is one more thing we are blind to when it comes to plants - We are blind to our dependence on them. We wake up in our house made of wood from the forests of Maine, pour a cup of coffee brewed from the coffee beans grown in Brazil, throw on a tee-shirt made of Indian cotton, and eat a locally-sourced tomato and cucumber salad, with toast made from wheat grown in Kansas. We drive our kids to school in a car with tires made of rubber that was grown in Africa and fueled by gasoline derived from Cycad trees that died millions of years ago. Chemicals extracted from plants can cure cancer and reduce fever, or increase our appetite, calm our nerves or block pain. And most importantly, we breathe the oxygen produced by plants worldwide.

Our existence is totally dependent on ensuring the continuation of plant life on Earth. So doesn't it behoove us thie Tu B'shvat to be a bit more appreciative of plants? To truly see them for what they are – complex and amazing organisms which not only make us happy to look at, but which provide us with the gift of life.

March 31, 2018

The VQ of Plant Intelligence

“Plant Intelligence” has been greatly debate by plant biologists and philosophers alike [1–9]. Yet throughout this debate, no measure of plant intelligence has been proposed.

Indeed, if plant intelligence exists, it must be quantifiable similar to human intelligence [10].

Towards this end, the Daily Plant introduces the VQ, the "Vegetal Quotient", which will be the plant equivalent of IQ.

We assume that some plants will have a high VQ, akin to genius plants, while others will be vegetally challenged, and have a relatively low VQ.

To make the VQ statistically valid, we need your help. Please fill in the VQ form below. Just as Binet’s original test has been modified over the past century [10], we realize that this test is only a beginning. However with your help we can make the VQ as valid a description of plant intelligence as IQ is of human intelligence.

If the form below does not work, click here.

Much thanks for your help!

Bibliography(1) Alpi, A., Amrhein, N., Bertl, A., Blatt, M.R., Blumwald, E., Cervone, F., Dainty, J., De Michelis, M.I., Epstein, E., Galston, A.W., Goldsmith, M.H.M., Hawes, C., Hell, R., Hetherington, A., Hofte, H., Juergens, G., Leaver, C.J., Moroni, A., Murphy, A., Oparka, K., Perata, P., Quader, H., Rausch, T., Ritzenthaler, C., Rivetta, A., Robinson, D.G., Sanders, D., Scheres, B., Schumacher, K., Sentenac, H., Slayman, C.L., Soave, C., Somerville, C., Taiz, L., Thiel, G. and Wagner, R. 2007. Plant neurobiology: no brain, no gain? Trends in Plant Science 12, pp. 135–136.(2) Brenner, E.D., Stahlberg, R., Mancuso, S., Vivanco, J., Baluska, F. and Van Volkenburgh, E. 2006. Plant neurobiology: an integrated view of plant signaling. Trends in Plant Science 11(8), pp. 413–419.(3) Calvo, P. and Baluška, F. 2015. Conditions for minimal intelligence across eukaryota: a cognitive science perspective. Frontiers in psychology 6, p. 1329.(4) Van Loon, L.C. 2016. The intelligent behavior of plants. Trends in Plant Science 21(4), pp. 286–294.(5) Marder, M. 2013. Plant intelligence and attention. Plant signaling & behavior.(6) Marder, M. 2012. Plant intentionality and the phenomenological framework of plant intelligence. Plant Signaling & Behavior 7(11), pp. 1365–1372.(7) Trewavas, A. 2016. Intelligence, cognition, and language of green plants. Frontiers in psychology7, p. 588.(8) Trewavas, A. 2017. The foundations of plant intelligence. Interface focus 7(3), p. 20160098.

(9) Trewavas, A.J. 2012. Plants are intelligent too. EMBO Reports 13(9), pp. 772–3; author reply 773.(10) Binet, A., Simon, T. and Town, C.H. 1912. A method of measuring the development of the intelligence of young children. Lincoln, Ill.,: Courier.

Loading...

November 24, 2015

DNA is DNA is DNA

While the interview was recorded as a discussion, it was edited into a monologue of over an hour, which you can access here. Below is the part pertaining to genetic engineering.

Your browser does not support the audio element. Your browser does not support the audio element.

October 5, 2015

2015 Nobel Prize highlights importance of botanical chemistry

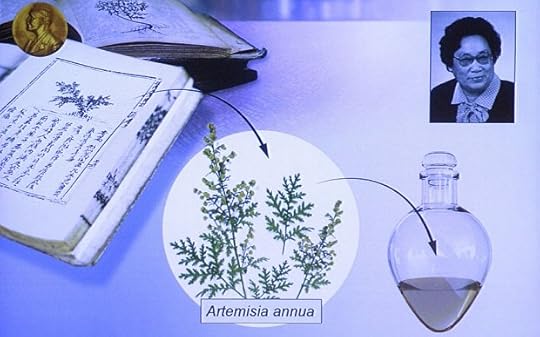

An illustration describing Ms Tu's work displayed during the press conference announcing the winners of the Nobel Medicine Prize. Linked from and The Telegraph: Nobel Prize for Chinese traditional medicine expert who developed malaria cure. Photo: AFP

An illustration describing Ms Tu's work displayed during the press conference announcing the winners of the Nobel Medicine Prize. Linked from and The Telegraph: Nobel Prize for Chinese traditional medicine expert who developed malaria cure. Photo: AFP This reminds us that many of our medicines have their roots in botany. The ancient Greek physician Hippocrates described a bitter substance, now known to be salicylic acid, from willow bark that could ease aches and reduce fevers. Other cultures in the ancient Middle East also used willow bark as a medicine, as did Native Americans. Centuries later, we know salicylic acid as the chemical precursor for aspirin (which is acetylsalicylic acid), and salicylic acid itself is a key ingredient in many modern anti-acne face washes.

The Pacific Yew is a conifer found primarily in the Pacific Northwest. Its thin scaly back would probably go unnoticed if not for the fact that it contains a chemical called paclitaxel, or more commonly known as the chemotherapy drug Taxol. Taxol was discovered in the mid 1960s as part of a large-scale program to identify natural products which might be used against cancer. In 1992 Taxol was approved by the FDA for use in fighting breast, ovarian and lung (and a few other) cancers.

And what would life be like without the opium poppy, the source of morphine or codeine. The medicinal (and likely recreational) uses of opium poppy have been known for thousands of years. And the increasingly legal uses of cannabinoids in western medical protocols cannot be ignored.

These are prime examples of how a deep knowledge of botanical diversity and chemistry can lead to incredibly important applications.

Unfortunately, education towards and development of expertise in these fields over the past decades were not a priority for many universities, where plant biology outside of the study of model organisms was looked down upon. At Tel Aviv University we've recognized the importance of botanical pharmacology. As Dean of the Faculty of Life Sciences, together with the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, we have initiated a search for a botanical pharmacologist whose position will be divided between our two Faculties, between plant biology and pharmacology. Such interdisciplinary research is critical for exploiting the medicinal potential hidden in plants.

September 12, 2015

My take on feeding the world

A few months ago I was interviewed by Story Preservation Initiative. What started out as a nice interview about What A Plant Knows, developed into a discussion about global food security and the role of genetic engineering in agriculture. The interview was edited into a monologue of over an hour, which you can access here. Below is the part pertaining to feeding the world.

Want the bottomline? (1) Increase yield per water unit; (2) reduce food loss from field to fridge and food waste from fridge to trash; (3) modify our diet; (4) adopt technology.

Your browser does not support the audio element. Your browser does not support the audio element.

September 7, 2015

Hawking Food Security in India

I was the guest of the Confederation of Indian Industries trade show called FOODPRO 2015. I have been interacting with CII for almost two years as co-chair of the India-Israel Forum sub-group on Food Security. I was one of the guest speakers for the conference part of the event. That in itself is not so bizarre – I’ve given talks over the years to diverse audiences. But what was bizarre is that they asked us also to man a booth in the exhibition part of the trade-show. So one of the 250 exhibitors at Chennai’s FOODPRO 2015 was the Manna Program for Food Safety and Security at Tel Aviv University. At both #35, we handed out flyers about our summer program and sang the praises of Tel Aviv University. To our right in booth #36 was CoCo Rain – “100% pure tender coconut water”. To our left in booth # 34 was Chennai Food Testing, a chemical service lab. Across the aisle in booth 112, Kookmate had a large exhibit of industrial cooking machines including an automatic chipati maker. Other booths included spice grinders, chicken pluckers, and sweet coffee machines. Booth H43-A belonged to "Spanker International". We didn't spend much time there.

Maya running our booth.Obviously, Maya Oren, the Program Director at Manna, in her sleeveless back dress, and me with light brown hair, and our promoting an advanced educational program, stood out among the sari-clad women and tika-adorned men selling ice cream machines, rice makers and automatic mixers. Our stall was frequented by an endless stream of curious visitors, most long past university age, who eagerly snapped pictures (especially of Maya), took home TAU leaflets, and especially, our keyfobs. Many of the conversations bordered on the absurd – “In which part of India Tel Aviv is?”, “What are you selling?”, “Are you interested in puffballs?”. It was like touring around India, while staying in one place. We quickly adopted the head bob, which we found made us more understood.

Maya running our booth.Obviously, Maya Oren, the Program Director at Manna, in her sleeveless back dress, and me with light brown hair, and our promoting an advanced educational program, stood out among the sari-clad women and tika-adorned men selling ice cream machines, rice makers and automatic mixers. Our stall was frequented by an endless stream of curious visitors, most long past university age, who eagerly snapped pictures (especially of Maya), took home TAU leaflets, and especially, our keyfobs. Many of the conversations bordered on the absurd – “In which part of India Tel Aviv is?”, “What are you selling?”, “Are you interested in puffballs?”. It was like touring around India, while staying in one place. We quickly adopted the head bob, which we found made us more understood. Without a doubt, most of our time was spent more in promoting Israel awareness than in attracting students. But we also met a group of motivated college students studying entrepreneurship who surrounded us, excited about the possibility of studying in the “start-up” nation. They were at the fair as part of a class on agro innovation. And we met a number of industrialists, who found in Tel Aviv University a novel option to the American universities they had been considering for their children. And we bought spices – 8 different types of curry for $5. I thought of taking home a chipati maker, but it wouldn’t fit in my suitcase.

Without a doubt, most of our time was spent more in promoting Israel awareness than in attracting students. But we also met a group of motivated college students studying entrepreneurship who surrounded us, excited about the possibility of studying in the “start-up” nation. They were at the fair as part of a class on agro innovation. And we met a number of industrialists, who found in Tel Aviv University a novel option to the American universities they had been considering for their children. And we bought spices – 8 different types of curry for $5. I thought of taking home a chipati maker, but it wouldn’t fit in my suitcase.August 30, 2015

My Pen Pal, Oliver Sacks

I did try a few times, through organized school activities, to write to a pen pal, but I don’t remember these efforts lasting more than one exchange. This need for an unknown pen pal probably found a proxy after age 11, in the numerous letters I wrote to friends across the country I had made while away at camp each summer.

Until I turned 51 that is.

One day, while sifting through the mail in my office, I found a letter with a hand-written address to me, and in the return address was printed “Dr. Oliver Sacks, New York”. I remarked to a friend who happened to be visiting in my office at the time, “Olive Sacks. Who is Oliver Sacks? Isn’t that the neurobiologist who wrote The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat?”. Why would he be writing me?

One day, while sifting through the mail in my office, I found a letter with a hand-written address to me, and in the return address was printed “Dr. Oliver Sacks, New York”. I remarked to a friend who happened to be visiting in my office at the time, “Olive Sacks. Who is Oliver Sacks? Isn’t that the neurobiologist who wrote The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat?”. Why would he be writing me?Inside I found a 3-page letter, hand-written by fountain pen in a flowing script. I admit that I had to remember for a second how to read script, I’d grown so use to email. Oliver wrote to tell me how much he enjoyed reading What a Plant Knows” and then went on to tell me of his own experience as a botanist, his quest for understanding what consciousness is, and how he related to my book.

Needless to say I was flabbergasted. I spent the next six hours crafting a reply, which I realized would also have to be written by hand. Numerous attempts found their way to the trash bin as I scratched out mistakes and misspellings. How did we survive without spell-check and backspace? I wanted to come across as erudite, but not pompous, casual, but not disrespectful. What could I write to the great Oliver Sacks which would at all interest him?

As the letter was hand-written, and I didn’t think to snap a picture of it, I don’t recall what I wrote. I’m sure it had to do with plant biology and plant intelligence. I signed it, “Sincerely yours, Danny Chamovitz”, put it in an envelope (after I found one of those arcane things) and sent it off to New York.

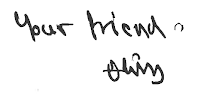

3 weeks later I received another hand-written letter, again 3 pages long, and with a copy of his soon-to-be-published piece in the New York Review of Books, “TheMental Life of Plants and Worms, Among Others” where he gave some mention to my book. Again I was flabbergasted, especially as he signed it this time, “your friend, Oliver”.

There it was. I had a pen pal.

There it was. I had a pen pal.Oliver and I corresponded several more times. I visited with him in Jerusalem, where I had the honor of interviewing him as a public lecture. He hosted my wife Shira and I for lunch in his apartment in New York. We corresponded after his announcement of his impending doom, and we corresponded a few weeks ago. In his letters he was full of life and wonder of our world, questioning me on any new studies on the abilities of plants, and telling me of his latest projects. I would write back with some details of obscure experiments, and comment on articles he quoted to me, and I would close with “Your friend, Danny”.

In our short friendship I learned humility, curiosity and the importance of intellectual honesty. And courage. Many people will mourn the loss of one of our age’s great communicators of the mind. I mourn the loss of my pen pal.

July 7, 2014

Plants in the City: Plants respond to vibrators

Even the New York Times published an article entitled "Noisy Predators Put Plants on Alert, Study Finds".

Such a headline calls into the question the validity of a previous blog here, What a Plant Hears and Chapter 4 of WHAT A PLANT KNOWS where I concluded "in lieu of any hard data to the contrary, we must conclude for now that plants are deaf".

So what's going on here? Is there finally hard data indicating that plants hear?

To really answer this question, one has to read the primary literature, and that is the research paper, "Plants respond to leaf vibrations caused by insect herbivore chewing, that was published recently in Oecologia.

Let's briefly read how the experiment was carried out:

The green vibrator attached under the leaf

The green vibrator attached under the leafChewing vibrations were recorded with laser Doppler vibrometry. To experimentally reproduce the caterpillar feeding vibrations, we used piezoelectric actuators supported under a leaf and attached to the leaf using accelerometer mounting wax." (see picture on right)In other words, the scientists recorded the vibrations caused by chewing, and then reproduced these vibration with a vibrator attached to the leaf. These physical vibration elicited a chemical response in the plant similar to the chemical response to insect chewing. This is a very interesting finding. But what it shows is the plants respond to physical vibrations induced by being attached to a microvibrator.

So if the popular press insists on bombastic news items, perhaps it would be better to say: "Scientists Find That Plants are Similar to Samantha - They Respond to Vibrators"

March 31, 2014

Intelligent Plants for Intelligent Gardens

"People are no longer satisfied with a standard run of the mill garden with dull plants. My customers demand that ionly the most intelligent plants populate their gardens" said Al Binet, the founder of IP - Intelligent Plants, Inc.

"We've developed a new scale called the Vegetal Quotient, or VQ for short, which measures the intelligence of individual plants on a scale of 50 - 150. A plant with a VQ of 150 would be considered highly intelligent (and thus highly sought after by our customers) while a plant with a VQ of 50 would not be found in a an advanced garden."

The VQ considers a number of independent parameters such as the time needed for a plant to differentiate

Dionaea muscipula, has a high VQ due

Dionaea muscipula, has a high VQ dueto its ability to count, remember, and move.between wave lengths of light, its sensitivity to tactile stimulation, and its ability to communicate with its neighbors. A highly intelligent plant would also have the ability to communicate not only with neighboring plants, but with other species as well, such as insects.

"I've invested hundred's of thousands of dollars in classes for my children to make sure that they test high in academic, social and emotional intelligence. " says Raymond Cattell, "So of course I would want the surrounded only by the most intelligent plants. Mediocre and dim-witted plants have no place in my garden."

Daniel Chamovitz's Blog

- Daniel Chamovitz's profile

- 59 followers