Robert Milner's Blog

April 12, 2019

Cues Commands and Prompts

A cue is not a command. Commands are not commands either. Words do not produce behavior. A cue is a signal to the dog that he will get paid for performing a certain behavior. The cue does not produce the behavior. The behavior is produced by the previous week of sessions with many payments for many repetitions of the behavior. To put the behavior on cue you gradually start preceding the behavior with the cue. Then you begin paying only the repetitions that are preceded by the cue. You stop paying the behavior when it is not preceded by the cue.

Cues

In the retriever training world a cue is a trigger to elicit a trained behavior from a dog. Many refer to a cue as a command. We make a very large assumption when we assume that the dog is picking the same cue that we are using for a particular behavior. When the trainer says “sit” and the dog sits, is the dog reacting to the sound “sit” or is he reacting to a visual signal, a consistent movement, probably subconscious, that the trainer makes whenever the trainer says, “sit?”

Consider the fact that dogs communicate almost entirely with the visual signals of a person’s body language. In training dogs preferentially pick a visual cue from the trainerto respond to. Frequently this cue is not the words or sounds emanating from the trainer’s mouth. The dog is really responding to some body movement that the trainer has habitually and subconsciously accompanied with the verbal signal.

Also consider the dog’s 14,000 years of evolution through domestication. Recent research suggests that early humans selected dogs for domestication by picking those animals more attuned to human communicative signals. Research demonstrates that dogs significantly read human behavioral characteristics as subtle as eye movements in the communication process. These factors indicate that dogs prefer a visual to an auditory cue. When you say “sit”, and the dog sits, he is more likely to be responding to your eye movements, or your infinitesimal head movement, or your slight posture change, than he is to your sound.

Trainer Kathy Sdao gave a great example of this tendency during a recent Clicker Expo. It seems a prominent agility trainer and handler had a very talented dog that looked like a sure winner for the national competition. The dog had won several regional contests. At the national started well and then froze at the first turn. He was unable to take a simple directional cue. He was out.

After the competition an analysis of his failure determined that the freezing was caused by the absence of the trainer/handler’s ponytail. The handler usually wore her hair pulled back in a pony tail and subconsciously accompanied her directional cues with a head movement that tossed her ponytail. For the regional competition, she had dressed more formally and had put her hair up. No ponytail. The dog was unable to respond because the cue that the dog had selected and learned was not present.

The most important characteristics of a cue are that it be clear and distinct. If you are not aware of what cue or cues the dog is selecting, then the chore of making that cue or those cues separate and distinct becomes quite difficult.

To add more confusion, here is a piece of Pavlov’s research which I came across recently in Fundamentals of Learning and Motivation by Frank Logan.

Experimental Neurosis

One use of the procedure of differentials classical conditioning is to determine how fine a discrimination an animal is capable of. With humans, of course, we can simply ask whether two tones sound alike or different, but with animals, we need to develop some nonverbal response by which they can communicate to the experimenter. Clearly if an animal can learn to respond differentially to two stimuli (cues), he can discriminate between them.

In an effort to obtain such information, Pavlov would first employ differential conditioning with stimuli (cues) that were quite dissimilar, say a very-high pitched tone versus a very low-pitched tone. He would then make them progressively more similar in an attempt to find out where the discrimination broke down indicating that the animal could no longer respond differentially. Interestingly enough, he found that when the stimuli (cues) became very similar, not only did the discrimination break down, so did the dog!

The dog would show obvious signs of fear and anxiety about the experimental situation, so that rather than standing quietly in the stock and salivating when appropriate, he would resist the situation. This behavior carried over to his total behavior. He would huddle in a corner of his living cage, cower at the sight of his familiar handler, refuse to eat regularly, and overreact to the slightest sound or distraction. Pavlov called this result an experimental neurosis because of its apparent similarity to many human neurotic behaviors, and he usually had to send the dog away from the laboratory for a rest cure of tender care in the country.

Considering all the above factors, it appears that is important to pick cues that are separate and distinct and to use those cues in a well-defined manner. All of this should also tell you that it is quite important for the puppy to be trained by only one person. No two people have the same body language, so no matter what the word is that is emanating from the human mouth, two different people are going to be sending two different signals in terms of body language. Pavlov’s experiment demonstrates that lack of consistency of cues has the potential to cause some problems.

You will greatly enhance your if you occasionally check to see what cue the dog is using. Try training with your mouth shut. Give no verbal cues, only gestures. Try it with sunglasses on. That will disguise your eye movements. Try it sitting down instead of standing. You might be surprised to see how often the dog is responding to a signal other than your words.

Because fuzzy cues make it much harder for the dog to behave as desired it is unwise to have two different trainers during the dog’s active learning periods. He will survive it. He will probably even learn in spite of the trainer because of his flexibility, but the learning process will be much more difficult for the dog.

As no two people use the same body language, a dog with two trainers will get inconsistent cues. That is not a recipe for success.

Prompts

A prompt is an enabler or trigger for a behavior. One example in dog training are a raised hand “traffic cop” gesture to induce a dog to stay. A trainer uses the prompt to produce behavior so he can reinforce it. As the behavior is becoming established the trainer fades the prompt and continues the reinforcement.

Another useful prompt is walking decisively in the direction you want the dog to go when giving a directional cast. The dog has an innate propensity to herd as a legacy from his wolf ancestors. When wolves need to kill a large animal they must operate jointly to bring it down. This joint behavior is basically herding. In the dog it manifests itself in the dog moving the direction that he sees the trainer move.

The first few times the dog is given a directional cast the trainer should take 3 or 4 or 5 decisive steps in the desired direction. Then, as the dog gains proficiency on directional casts, the

.

The post Cues Commands and Prompts appeared first on Good Dog Chronicles.

October 18, 2016

Three Brief Video Clips Showing Well Trained Gundogs in the Field

Here are three brief video clips of well trained gundogs at work.

Phil Parkinson’s FTCH Twixwood Shooting Star

This retrieve occurs in a beet field through which many pheasants have just been pushed slowly to move them on the ground. The occasional flush occurs, with the bird being shot. Watch this dog sort out the live bird scent from that of the slightly hit bird that has just been shot but not killed. This is a field trial and the dog will be disqualified if he chases an unwounded bird.

http://youtu.be/u5wu3VCKrpM

Robin Watson with FTCH Brackenbird Minnow

This is a field trial. Note that the dog is doing nearly all of the work. Most of the falls and retrieves are deep into cover where the dog is out of sight, so hand signals are not feasible.

Reddihough Day Hallrule

Note the good manners and calm demeanor of these gundogs on a day of shooting in Scotland.

The post Three Brief Video Clips Showing Well Trained Gundogs in the Field appeared first on Good Dog Chronicles.

September 30, 2016

Put the Bird Where? – Preserving Delivery to Hand

I arrive at my neighbor’s door and knock. Pete answers the door and invites me to come in. I enter and sit on the couch and the two of us begin the discussion on improvements for the school festival. About 4 minutes into the conversation I feel something nudging my leg and look down. Pete’s border collie, Missy, is nudging me on the leg. I look down and see that she has a ball in her mouth. I take the ball and toss it for her. She fetches it and returns to nudge my leg again. The light bulb snaps on. Missy has,accidentally, trained herself to deliver to hand in order to get a person to toss the ball for her. If Missy could do that by accident, then we brilliant humans should be able to do it by design.

Being an astute dog trainer, I come up with a training model:

Start with two tennis balls:

Roll one ball across the ground. The dog pounces on it. You call him over and take it from his mouth and immediately give him a short throw. That is classic operant conditioning. The behavior is bringing the ball to hand. The reward is an immediate retrieve. Repeat a number of times and add on the cue, “fetch.” Correct deliveries to hand are immediately paid with a toss. Non delivery to hand is not paid. The dog will figure out the payment system quickly. You will have a dog that delivers to hand and fetches on cue in about 3 sessions of a couple of a couple of minutes each. That beats the heck out of the traditional force fetch programs that can go on for six or eight weeks.

Here is a short video clip of Buccleuch Temperance learning delivery to hand.

Note the strings thru the tennis balls to compensate for fumble-fingered humans. Note also that a training dummy is slipped in when the dog is getting good. Note also that Tempie is not rewarded for a delivery when she picks the dummy up by the string.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BrOkq9fsSkI

The post Put the Bird Where? – Preserving Delivery to Hand appeared first on Good Dog Chronicles.

September 8, 2016

Steadiness Training – The Beginning

A steady retriever is one that waits quietly and calmly while the birds are shot and fall. The wait might be 3 minutes or 30 minutes. The behavior should be the same regardless of the time duration. The dog waits quietly until released to retrieve. The key to keeping steadiness training simple and easily achieved is to refrain from giving pup much of a taste of the alternative. Start early and don’t give “instant” retrieves. Train the puppy to expect to wait a while to be released for the retrieve.

Here is a video clip of the beginning of the training process. Temperance gets paid for sitting quietly for first an increasing length of time, and for increasing distraction levels presented by gradually increasing the distance of the trainer and increasing the loft of the tossed dummy. A clicker is used to mark the end of the waiting period. She is initially paid with freeze dried liver treats, and on the last throw she is paid with a retrieve for the wait. Note that the dog learns much more readily when the food treats are delivered to her at the spot you want her to stay.

Steadying with Buccleuch Temperance: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hC8frpx5lPY

The post Steadiness Training – The Beginning appeared first on Good Dog Chronicles.

August 26, 2016

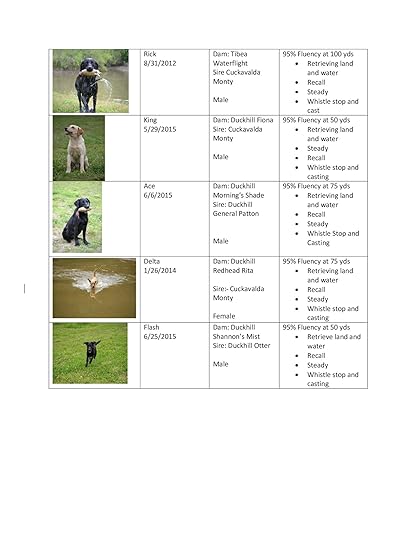

Available – Trained Gundogs for Sale – email: mauri@duckhillkennels.com

The post Available – Trained Gundogs for Sale – email: mauri@duckhillkennels.com appeared first on Good Dog Chronicles.

House Training for Dogs and Puppies

The principles of evolution say that puppies have a natural proclivity to eliminate outside the den. If they did not, then the probability of disease would be high. Eliminating outside the den carries with it a survival value. Thus the dog has an innate propensity not to foul his own nest. All the human needs to do is make it easy for the dog to exercise that innate behavior. It is essentially a matter of schedule management. Here is how to accomplish this task:

Get the dog a crate to be his “den”. The crate should be of a size that he can comfortably turn around and lie down. It should not be much larger. If the crate is too large, put in some cardboard boxes to take up the extra space. Keep pup in the crate when he is unsupervised. The basic principle is to adjust his environment so that he only eliminates when he is outside. This trains the behavior of eliminating outdoors. The act of eliminating is a reward in itself. If you take him to a particular area in the yard every time and give him a treat, he will form a preference for eliminating in that place. Whenever you want to let him out of the crate for indoor activity, always take him from the crate directly outdoors and let him eliminate, before turning him loose in the house.

Established a fixed schedule. Feed the dog the same time or times each day. Let him outside on a fixed schedule. The only way a dog can predict what time to expect dinner is by what the schedule was yesterday and the day before, and the day before. The same principle applies to going outside.

An adult dog’s digestive time for canned dog food averages about 4 to 6 hours to move through his system. With dry food, it may take as long as 8 to 10 hours. A puppy’s cycle time will be much faster. Stress and many other factors will also alter cycle time. In other words it is quite difficult to pin down. It is best to err to the conservative side. My rule of thumb is two hours for young puppies; four hours for adults.

Limit the intake. If you cut back 50% on the dog’s food for the first three days of housebreaking, you make it easy for him to “hold it”, and thus easier for him to adjust his schedule to your fixed and thus predictable schedule.

The best regimen for night confinement for puppies is:

Give evening meal at 4:00 in the afternoon.

No water after 6:00 in the evening

Take out at 11:00 PM then put in crate

Wake up at 5:00 am and take outside

Most puppies over 10 weeks of age can adapt readily to this schedule if the schedule is regular and the puppy is on a sparse serving size of food. The major contributors to difficulty with housebreaking are:

Irregular schedule imposed by the human

Overfeeding

Unsupervised puppy activities in the house. If you follow the above principles, you should be able to house-train a puppy or dog in three to five days.

The post House Training for Dogs and Puppies appeared first on Good Dog Chronicles.

August 9, 2016

Starting a Retriever Gundog Puppy on Blind Retrieves

The conservation aspect of a retriever’s job is exercised by his ability to collect the crippled birds quickly before they have a chance to run off or swim off to die uncollected. Often pup will have to ignore closer lying and quite tempting dead birds in order to retrieve the cripples first. Many times the cripple will be the very bird that he did not see fall. In that case pup must be guided to the cripples area of fall by a sequence of whistle stops and hand signals. This might seem to be a daunting training task, but if done in the right sequence it is remarkably easy.

The term I give to this important aspect of a gundog’s work is “the long unseen cripple”. There is a definite series of steps in pup’s life that will make it easy for you to train him to a great degree of proficiency on the behaviors for retrieving the long unseen cripple. The one most important factor in making it easy to teach pup blind retrieves is to not give him any marked retrieves. A marked retrieve is the retrieve of an object (bird, dummy, tennis ball, etc.) that pup has seen fall. He has been hard-wired through the genetic selection of two hundred years to go for falling objects. The retrieving of those seen falls is like crack cocaine to a retriever pup. He can’t get enough of it. When a puppy has had a number of marked retrieves, it becomes much more difficult to teach him blind retrieves. Conversely, if he has not had marked retrieves, he doesn’t know what he is missing and he loves blind retrieves.

The only other prerequisites for blind retrieves are having a little obedience and being steady enough to sit while you toss a dummy out 10 feet to become the blind retrieve, and the very important behavior of stop/look (at handler) when a whistle signal is given.. Pup will also have greater probability of success when he has completed the period of extremely fast growth that encompasses his first 6 months of life. During that first 6 months most of his energy his going into growth and he does not have a lot left over for long blind retrieves.

The basic trick to training pup on blind retrieves lies in making sure he is always successful. Then he will learn rapidly. The key to success lies in pup’s inherent GPS system. Pup can always find his way back to a place that he has been before, especially if that place contains something that he wants. One extreme example happened with me back in the 70’s when I was running field trials. I was driving across Wyoming with a truckload of 16 Labradors and stopped late one afternoon at a wildlife management area to let the dogs get out and exercise. It was an ideal spot with a large area of ponds bordered with cattails and well off the highway. I turned out all the dogs and let them run and play in the water for a few minutes. One of them got off some distance across a couple of ponds and happened to flush a mallard hen off of her nest. She proceeded to act like an injured duck and lured the dog away from the nest. The last sight I had of the dog was a tiny black figure disappearing over a ridge in the distance. I called in and loaded all the other dogs and drove around for an hour looking for the miscreant. I had no success, so I went back to the place where the truck had been parked for the let out. I tossed a jacket on the ground and went to the nearest town and had dinner and spent the night. The next morning I went back to the coat, and there sat the dog. He knew exactly where that truck had been parked when he took off. When you think about it, mother nature had to equip dogs with a good GPS. When an ancestral bitch had a litter of puppies, she had to support them and herself by hunting. The hunt might take her miles away from the pups in their den. She had to be able to find her way back to them. Similarly, when an ancestral dog found a valley teeming with rabbits, or a section of stream with a lot of fish to catch, he needed to be able to find it again when he got hungry.

Whistle Stop

The most important element in the blind retrieve is the whistle stop. The handler gives a “toot” on the whistle to which the dog responds by stopping and looking at the handler, who gives the dog a directional cast toward the unseen fall. To accomplish a blind retrieve, note that sitting on a whistle “toot” is not required. The dog can quite proficiently accomplish a blind retrieve by simply looking at the handler in response to a whistle signal. The dog doesn’t need to sit to get it done. First understand that a dog’s hearing is four times better than a human’s is. If you train pup to stop/look close to you with a loud whistle blast, then he will not be very responsive to the soft sound he will hear when he is 200 yards away. Therefore, when he is within 30 yards, keep the whistle volume very low.

Here are the steps leading to pup’s learning to get the long unseen cripple:

1. Take the dog for a walk and encourage him to get out away from you. When he’s 8 or 10 feet away give a soft “toot” on the whistle. When he glances back at you throw him a tennis ball. Note that the behavior is “stop/look”. The payment is the tennis ball. Take a quarter-inch drill and drill a hole through a tennis ball. Thread a 8” piece of nylon rope through it. Knot each end of the rope. This will give you a “handle” that enables longer throws, and thus payments at greater distances.

2. Repeat the whistle-stop payment 3 or 4 times. End the lesson. Skip at least one day before another lesson. Do 2 or 3 lessons and then proceed to #3.

3. On the this lesson sit pup and throw a dummy out 20 yards. Send pup. As he picks up dummy, give a “toot”. When he looks at you throw a tennis ball out to him. He will spit out the dummy and go for the ball.

4. Repeat step 3, but give the toot when he is half-way to the dummy. When he stops and looks at you throw the tennis ball. If he doesn’t stop, then go back and repeat step 3.

A few sessions of this activity will have pup crisply looking to you on hearing a whistle “toot”. Then he is ready for the long unseen cripple lessons.

Long Unseen Cripple

Using dummies we will recreate the scenario of two close dead birds downed close with a long unseen cripple 30 yds out. We will use pup’s position-finding talent to insure his success. Start in a field with minimal cover where you can run pup on a 30 yd memory retrieve. The dog will learn faster and to a higher level if one or more days off occur between training sessiions. In other words, every other day is better than every day for training. The goal of the exercise is not to line the blind. Conversely the goal is to send pup to the area where he thinks there is a bird, and let him hunt a little. Then handle him away from “his” area and to a fall. This allows him to be rewarded with the “find” for moving his hunt area from “his” to “yours”. This programs into pup the behaviors needed to find those tough, long unseen falls that he will get in real life hunting, where generally the location of the long unseen cripple is pretty fuzzy in everyone’s minds.

1. Session 1 – Taking pup at heel with you, go out 30 yards and drop the a dummy representing the unseen cripple. Then return with pup half way back to your starting point. Stop, turn and send pup the 15 yds to pick up the unseen. Then take him with you to put the long unseen back again. This time take him back the full 30 yards and send him again to pick it up. This will fix the unseen’s position for the next lesson, which should come the day after tomorrow.

2. Session 2 – Return to the scenario of session 1. Take pup out with you to place the long unseen.

Then put a couple of short “dead birds” to handle him away from on his way to the long unseen cripple. To simulate the “dead birds”, leave pup sitting and walk out in a line 30 degrees to the left of the line to the unseen. At about 10 yards, stop and throw two dummies with good lofting throws of about 30 feet (away from the line to unseen). Then walk over and pick the 2 dummies up. This will insure that pup will be successful on the exercise. Then walk back in to pup. Send him toward the two falls you just picked up. When he gets to the area of those 2 falls, let him hunt a second or two, and then give him a whistle toot. If he looks at you, start walking toward the long unseen cripple. If he gets off course “toot again” and again when he looks signal by walking the direction he needs to go. You will over a number of sessions fade the walking signal down to a hand signal.

If he does not look, keep giving a toot every 3 or 4 seconds, until he does. If he doesn’t stop and look for you to give him a walking hand signal, then terminate the exercise and do a few whistle stopping exercises tomorrow, returning to the long unseen exercise in a few days.

After 6 or 8 sessions on the basic model of unseen cripple drill, the dog will be fairly proficient. Then you need to start making the distances longer and raise the distraction level by moving it to different fields, and adding distractions such as other dogs running around while yours is performing, adding shots, and sometimes using birds. Keep picking up the “short dead falls” until the dog is totally proficient on all variations of the drill. Keeping the dog successful is the key to a fast, easy training program. .

When your dog is proficient at this long unseen cripple drill in a number of variations, he is ready to become, with some hunting experience, a fabled “dog of a lifetime”.

The post Starting a Retriever Gundog Puppy on Blind Retrieves appeared first on Good Dog Chronicles.

July 5, 2016

British Labradors as Product of British Retriever Field Trials for Breeding Selection

Working Labradors in England are heavily influenced by the relatively small population of Labradors that are actively bred and trained for competition in retriever field trials. The defining characteristics of this field trial population are not looks or appearance but rather temperament, behavior and trainability. The typical successful field trial Labrador In England tends to be calm of temperament, typically easy to train, a high degree of gamefinding initiative and has a tendency toward natural good manners and tends to have a genetically inherited tendency to deliver a retrieve to hand. There are two major factors driving the breeding selection that tends to produce these characteristics of dogs in the field trial population. Those breeding selection drivers are (1) a culture of gentle training methods, and (2) the behavioral requirements of a successful field trial dog.

Gentle Training Culture

The British retriever field trial sector is characterized by a culture of gentle positive training methods. The practice of force fetch training is nearly never encountered in England. Delivery to hand is in the main accomplished by breeding selection for natural delivery to hand. A typical puppy of British field trial breeding has a natural tendency to deliver to hand. All the owner needs to do is reinforce that tendency by rewarding it at the appropriate times.

British field trials are restricted to 12 dogs in a one-day event or 24 dogs in a two-day trial. A further limit is that of a maximum of two dogs handled by the same handler in a field trial. These numeric limits will not economically support a structure that includes a lot of professional trainers. Because of that basic structure of field trials, nearly all competing field trial Labradors in England are trained and handled by their owners. When that amateur owner encounters a dog that is too “hot” to train to field trial standards by traditional gentle training, the dog is generally found a new home. A more suitable field trial candidate is then sought. Thus breeding selection tends to favor dogs that are fairly sensitive and tractable. Incidentally, the use of the term “professional” and “amateur” is not appropriate to the British field trial system. The British Field Trial Regulations do not differentiate between a professional and an amateur.

Behavioral Requirements for a Winning Field Trial Dog

British retriever field trials are run in shooting environments and settings that are very different from American shooting, but the gundog behaviors those field trials require are perfect for American shooting. To become a winner, the typical field trial retriever must exhibit good manners in extremely high distraction environment and they must demonstrate game-finding initiative and hunting persistence. Typically the trials will consist of two types of scenario, driven birds and walked-up birds. The British shooting scenario is a little different than that of American shooting, but the behaviors required of the retrievers is very similar. The major important behaviors are:

1. Exhibit Good Manners in an extremely high distraction environment

2. Demonstrate game-finding initiative and hunting persistence

3. Leave the short visible dead birds and go for long unseen cripple when so instructed.

Exhibit good manners in extremely high distraction environment.

Driven pheasants comprise a large part of British shooting. Pheasants are driven from cover and above pre-stationed shooters. The shooting is usually fast and furious with many birds being dropped around the guns. The dog must sit quietly at heel during pheasant drives during which dozens of shot pheasants fall all around the dog. (I once saw a falling pheasant bounce off a dog’s shoulder and the dog remained sitting) A drive typically lasts 15 to 20 minutes or more, during which time the dogs are expected to sit calmly and quietly.

Walkups constitute the other major scenario of British Field Trials. Here a line of beaters walks line abreast across a field. Interspersed across the line are 4 to 6 shooters, and probably 4 dogs under judgment. As the line progresses the dogs must walk quietly at heel while the birds are flushed and shot. After several birds are down the line halts, and the birds are retrieved. The dogs must walk quietly at heel with no badgering from handler. They must remain quietly at heel during flushing and shooting of birds. Wounded birds or “runners” are retrieved first. Whether it is a marked (seen fall) or blind (unseen fall) depends upon whether the next dog up to run happened to see it or not. The judges judge the dog’s performance the same in either case.

The walked-up bird gets interesting when it is a big cock pheasant which is only slightly hit and sails off to go down 75 yards in front of the line. When a dog is sent for this bird, he is expected to go to the area of the fall, find the blood trail, and track down the wounded pheasant. Furthermore he is expected to ignore the freshly flushed birds that may spring up as he makes his way along the wounded bird’s trial. Chasing freshly flushed birds will cause his elimination. The dog must stick to the wounded bird’s trail and collect him, or the dog will be dropped from competition.

Demonstrate game-finding initiative and hunting persistence

On driven birds, the dogs not only get the opportunity to demonstrate their steadiness in the face of immense temptation, they also get the opportunity to demonstrate their game-finding initiative and their hunting persistence. At the end of the drive, the judges will ask each dog to pick up a particular bird. The judges will select the wounded birds first. Thus the dog may be required to ignore several birds lying in plain sight out front and take line of to the left toward a cripple, which the dog did not see, downed 150 yards off in dense cover, out of sight of the handler. The handler sends the dog off on a line, handles him up to the cover and casts him into it. Then it is all up to the dog. If he finds the bird he is a star, if he fails to find it, he is out of the trial.

The Cream Rises to the Top

The British have one custom in their retriever field trial which helps insure that the best dogs tend to win at field trials. That custom is the eye-wipe. When one dog fails to find a bird for which he has been sent, then the next dog up is sent for the bird. If the second dog succeeds, he is said to have wiped the eye of the first dog. If both dogs fail, then typically both are dropped, under the premise that they had the opportunity of picking up the scent trail while is was still fresh and they failed to do so.

The British Retriever Field Trial system has done an excellent job of preserving the genetics of a good working gundog. A British Labrador whose pedigree has a good sprinkling of British Field Trial Winners and British Field Trial Champions will have a high probability of having the behavioral tendencies which lead to proficiency in the three major behavioral elements of success in British Field Trials:

1. Exhibit Good Manners in an extremely high distraction environment

2. Demonstrate game-finding initiative and hunting persistence

3. Leave the short visible dead birds and go for long unseen cripple

In general one would expect such a dog to exhibit a calm temperament, to be tractable, and sensitive and easily trained by a relatively inexperienced trainer. One would also expect that dog to have lots of gamefinding initiative and hunting perseverance. These behavioral traits are important to the hunter and his gundog whether the dog is competing in a field trial in the UK or whether he retrieving ducks shot on Chesapeake Bay.

The post British Labradors as Product of British Retriever Field Trials for Breeding Selection appeared first on Good Dog Chronicles.

June 18, 2016

Hunt Drive ???– Retriever Gun Dogs and Predatory Conservation Practices

The Old Man and the boy crept quietly up the back side of a ridge overlooking a small mountain stream in Yellowstone Park. As they cautiously peeked over the top they could see fifty yards below the burbling stream shining in the late morning sun. It was a small stream 3 to 5 ft across and looked ankle deep in most parts. The old man whispered to the boy, “My old friend George is chief ranger here. He told me about a coyote bitch that frequently fishes here in the stream to feed a litter of cubs that she has about a quarter mile north of here.” He settled back to wait for the coyote. 15 minutes later, the old man nudged the boy and whispered, “look off to the left there about a hundred yards. Here she comes.”

The boy watched as the coyote approached the stream. She came at a purposeful, but not fast walk, regularly scanning her surroundings as she shortened the distance to the creek. She occasionally stopped to study something that caught her attention, then resumed her walk to the creek.

“Look at her,” whispered the old man. “She is the epitome of energy conservation. She never breaks out of a fast walk. She is steadily scanning her surroundings, but doesn’t give a physical reaction other than to stop and study a perception for a couple of seconds before going on. She doesn’t waste energy with unnecessary muscle movement.” The old man paused for a moment to watch as the coyote caught a fish. Then he continued, “Look at the way she the way she caught that fish. While she was walking across the stream, scanning the water, she took one quick step with a quick duck of the head and snap of the jaws and came up with an 18 inch trout. She wasted no motion or energy.”

The coyote bitch proceeded with eating the fish. Then she turned back to the stream. She walked into the water, and took a couple of short bouncing steps to stir the fish. There followed a quick pounce, and she snapped up a second fish. She took it up on the bank to eat. After she finished the fish she went back to the stream and with what gave every appearance of a casual dip of her head into the water, snapped up the third fish. This one she held in her mouth as she set off at a purposeful walk toward her den.

As the coyote ambled off along the hillside below, the old man continued his nature lecture, “That bitch is taking the third fish back to the den. When she gets there, she will regurgitate the first two fish onto the ground for the pups to eat. That’s mother nature’s solution for tenderizing and ease of transport.”

The old man slowly arose and stretched his stiff joints. “Let’s go back to the cabin and get some lunch and I will tell you how to fit this coyote saga into the retriever gundog picture,” he said as he started back down the ridge.

Back at the cabin, the old man fed the Labrador, Jake, and fixed lunch. He and the boy sat down to eat. The old man tasted his sandwich and nodded approvingly. Then he said, “Boy, there is a major gundog lesson in what we watched this morning.” He removed his glasses and pointed toward them toward the dog for emphasis. “A good gundog should move like that coyote. He should be as energy efficient as a predator, and he should make finding and retrieving game look effortless and easy, just like that coyote made catching fish look effortless and easy. The measure of gamefinding initiative in a gundog is the number of birds in your hand with apparent ease of effort.” He slid his chair back and turned toward the boy for emphasis as he stated, “A good gundog hunts efficiently and hunts for a long time.”

The old man stopped, picked up his pipe and packed tobacco into it. The boy was familiar with this ritual which usually preceded a major pronouncement. After lighting his pipe, the old man said, “Here in America, unfortunately, the retriever field trial game has made it popular for dogs to be flashy, run fast, bounce high, and waste a lot of energy. That is a faulty model. The American field trial Labrador gene pool has just about lost the self-pacing behavior that Mother Nature provided dogs in their natural state. The dogs of the American field trial gene pool are very highly visually reactive. The sight of moving objects sets off muscle movement that wastes energy and creates heat which leads to early fatigue.”

He paused to pet Jake on the head and gather his thoughts. Then he continued, “The guys that run the Iditarod in Alaska have learned the effects of dog size, dog effort and dog heat production. The Iditarod is the annual dogsled race from Anchorage to Nome. It is just over a 1000 miles in length and is run in March when temperatures frequently are subzero with wind chill pushing the effective temperature down as low as −100 °F. The race takes 8 to 9 days to run. It is an extreme test and has served as an excellent laboratory for studying factors affecting stamina in dogs. One of the major factors is size. Early on, some mushers tried larger dogs with the logic that a larger dog with a longer stride would cover more ground faster. What they discovered was that larger dogs fatigue more quickly from overheating. They found that dogs larger than 50 to 60 pounds have a body volume and muscle mass that generates too much heat for the dog’s skin surface area to lose efficiently. In short a big dog generates more heat than he can lose, and he fatigues more rapidly. The ideal size for stamina appears to be 50 to 60 lbs.”

The old man paused and relit his pipe, a sometimes lengthy process. Then he continued, “A classic example of visual reactivity being confused with hunting initiative you see in the world of explosive detection dogs. Labradors are being used a good bit in Afghanistan for IED detection and the scent detection trainers are out trying to buy dogs for that job. Their almost universal analytic test is ‘how vigorously does the dog chase a tennis ball?”

The old man shook his head and informed the boy, “Tennis ball chasing in a dog is mostly a measure of visual reactivity. The more visually reactive a dog is, the more aggressively he will go after a tennis ball. Generally the very visually reactive dog is also very energy inefficient because he continuously reacts with muscle movement in response to visual triggers. The ball reactive dog is frequently a dog with short hunting persistence because of early fatigue from all the muscular acitivity. The problem is not in the dog. The problem is in the breeding selection and in the dog evaluation method. To get a dog with more persistent hunting behavior breeders need to breed back toward the self-pacing behavior that Mother Nature originally gave to the dog’s ancestors.”

The old man stood up and motioned for the boy to clear the dishes from the table. Then he continued, “The upshot of all this is that you need to remember what I have said when you get ready to buy a retriever gundog. When you look for the litter’s parents, look for those that are closer to Mother Nature’s model of a predator. Look for parents that move smoothly and efficiently and make finding and retrieving game look effortless. If they are in the 50 to 60 lb size range that is a plus on heat tolerance and stamina. A bigger plus on heat tolerance and stamina is a calm behavior as opposed to the visually reactive dog. The dog that moves efficiently and hunts persistently will, in the hunting field outperform the flashy, fast moving, bouncing bundle of barely contained energy. You don’t measure gamefinding initiative by a dog’s energy wasteful behavior. You measure gamefinding initiative by how many birds he brings to hand and by how effortless he makes the process appear.”

Here is a video clip of a fishing coyote: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DjCd09VyQbE

The post Hunt Drive ???– Retriever Gun Dogs and Predatory Conservation Practices appeared first on Good Dog Chronicles.

June 3, 2016

The Hard-Mouthed Gundog

According to history, Labradors Retrievers got their start in the 1500s and 1600s with the British Cod-fishing fleets that spent summers harvesting cod off the coast of Newfoundland. Back in those days a dog had to have great economic value in order to earn his keep. With fishing-fleet Labradors, that value lay in the dog’s talent at fetching. The sailing vessels brought with them small dories which were offloaded at Newfoundland and used for the Cod fishing. Two fishermen would man a dory and fish with handlines, hauling up cod that bit on the baited hooks. Since hooks were fairly primitive back then, one can guess that a significant number of cod would flop off the hook at the surface. Usually a fish that has been hauled up from a depth and flops off of a hook will be dazed and immobile for a few seconds, giving ample time for a dog to jump from the boat and grab the fish. A dog that delivered that fish to the fisherman’s hand was valuable. Thus the Labrador got an early start on delivery to hand with fish. Logic would indicate that those early English fishermen bred the more talented fish- catching dogs to the more talented fish- catching bitches and gave an early start to the selection of the breed’s signature behavior of gentle delivery to hand.

According to history, Labradors Retrievers got their start in the 1500s and 1600s with the British Cod-fishing fleets that spent summers harvesting cod off the coast of Newfoundland. Back in those days a dog had to have great economic value in order to earn his keep. With fishing-fleet Labradors, that value lay in the dog’s talent at fetching. The sailing vessels brought with them small dories which were offloaded at Newfoundland and used for the Cod fishing. Two fishermen would man a dory and fish with handlines, hauling up cod that bit on the baited hooks. Since hooks were fairly primitive back then, one can guess that a significant number of cod would flop off the hook at the surface. Usually a fish that has been hauled up from a depth and flops off of a hook will be dazed and immobile for a few seconds, giving ample time for a dog to jump from the boat and grab the fish. A dog that delivered that fish to the fisherman’s hand was valuable. Thus the Labrador got an early start on delivery to hand with fish. Logic would indicate that those early English fishermen bred the more talented fish- catching dogs to the more talented fish- catching bitches and gave an early start to the selection of the breed’s signature behavior of gentle delivery to hand.

The advent of the percussion cap firearm in the 1800s brought on the age of sporting firearms and drove the rise of wingshooting, also driving the development of retrievers for finding and delivering shot game to hand. These events further accentuated the custom of breeding selection of dogs of soft mouth. The following 200 years of breeding selection for soft mouthed delivery to hand, brought us the soft mouthed Labrador we imported from the UK in the 1920s and 1930s. Today in the US, that Labrador has slid backwards toward become generally more prone to mouth problems due to poor breeding selection practices. A major factor is the widespread practice in the field-retriever sector of force fetch training.

Force fetch training is the commonly accepted solution for a hard mouth dog. If you have a dog that has mouth problems and put him through a proper force fetch training program, then his hard mouth issues will be suppressed and he won’t exhibit them. The next problem comes with his offspring. Because hard mouth is to a great degree genetically transmitted, the hard mouth dog who has been force fetched may deliver softly to hand like a gentleman, while his progeny will have a large propensity toward being hard mouthed like their sire was before his force fetch program. When you are selecting breeding candidates from a pool of force fetched dogs, you cannot tell which ones are naturally soft mouthed deliverers to hand, and which ones are soft mouthed only from the force fetch training.

The practice of force fetch training started proliferating in the sporting retriever community in the US in the 1960s and 1970s. Today nearly every retriever trainer practices force fetch as an integral part of his training program. The force fetch phenomenon appears to be confined to the U.S. The practice is rarely encountered in the working retriever communities in the UK or the rest of Europe. The Europeans deal with hard mouth with breeding selection instead of training.

All the above having been said, if you have a dog with hard mouth what can be done? First define the depth of the problem. In many cases where the dog has merely a slight tendency to be rough on birds, the issue can be solved with a few months of work restricted to dummies. All work with birds should be reserved until after the dog’s trained behaviors of coming, delivering to hand, and performing blind retrieves are very proficient. This means all retrieves are with dummies until the dog is “bullet proof” on all behaviors including blind retrieves. This should be coupled with much reinforcement of the behavior of coming to you with speed and focus. It is difficult for a dog to rough up a bird when he is coming to you with alacrity.

For the more extreme cases of hard mouth, a thorough force fetch program will generally solve the problem.

Don’t confuse hard mouth with eating a bird by invitation. When you leave pup in the car alone with the day’s take of mallards, don’t be surprised if you return and find yourself one or two ducks short. You have invited him to eat it by leaving him alone with it. Eating a bird or two under such circumstances will not make him hard mouthed.

In the early 70s when I was running field trials I had a dog on the truck who was a bit weak on water blinds. I had been a little too hard on him in the water and when he ran blinds he was very slow on his entry into the water. This was very embarrassing at field trials, so I decided to try a radical solution. One Sunday, when he had made it to the water blind and had good work,. I decided to try feeding him a duck before the water blind. I had a crate a mallards on the truck, so 15 minutes before Ace was due to run the water blind, I took a live Mallard and tossed it into Ace’s crate. I returned 10 minutes later and got Ace. All that remained of the duck was a pair of feet. When Ace ran the water blind, he hit the water like a bullet. Subsequently at field trials, eating a Mallard became part of his pre-water- blind prepartation sequence. At field trials he continued to get his pre-water blind “starter” and he continued hitting the water hard. He never offered even a hint of roughing up bird he was retrieving in training or in field trials.

One physiologic condition which will promote hard mouth is low blood sugar and/or hunger. I stumbled into this bit of information when I had Wildrose Kennels back in the 1970s and 1980s. The first 10 years I fed the dogs in the evenings. During that period I had a fair number of dogs with mouth problems. I think that is what made me a great supporter of force fetch training back then.

In the early 1980s I switched to feeding in the mornings and my incidence of mouth problems went to practically zero. I deduced that the mouth problems had been due to hunger and low blood sugar. The morning feeding regimen took care of it.

If you have a retriever puppy, and you want to maximize the probability that he will grow up to deliver ducks softly to hand, the program is fairly simple. You should:

1. Feed in mornings

2. Develop his retrieving behaviors to a high level of proficiency with work on dummies; then add the birds.

Last but not least, if you have a dog with a propensity for hard mouth, don’t breed him if you want your children and grandchildren to be able to find retrievers that genetically deliver softly to hand.

Robert Milner

The post The Hard-Mouthed Gundog appeared first on Good Dog Chronicles.