Arthur George's Blog

July 27, 2024

Mythology of Wine Webinar Video Posted on YouTube

This video of last week’s webinar about the mythology of wine has just been posted on YouTube. It offers a fascinating look on how wine and its associated myths underlie so much of our religion and culture. Enjoy! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rukQfQ4VzP0

July 9, 2024

Mythology of Wine Free Webinar July 20

On Saturday, July 20, I’ll be doing a free webinar hosted by prominent mythologists about the mythologies pertaining to wine, based on my book The Mythology of Wine. I’ll cover Greece and the wine god Dionysus, wine in the Bible, wine mythology in ancient Egypt, and much more. It starts at happy hour (3:00 PST) and will go for one hour, so attendees are encouraged to sip on a glass of wine while they watch and ask questions. Hope you can make it! Here’s the link describing it and for registering.

June 7, 2023

What Would Jesus Say and Do Today?

Myths are often regarded as simple falsehoods, as being about people or gods that have never existed or events that never happened. But regardless of their historicity, the important part about myths is the fundamental truths that they convey to a community, then and even now. This is especially true for Biblical myths, including stories about Jesus. Our American community is still largely Judeo-Christian, and even if one is not Christian or Jewish, all of us still grow up in our largely Judeo-Christian culture and are influenced by it, whether we are fully aware of this or not. Therefore, it behooves us to consider how the teachings and deeds of Jesus (i.e., the truths in the stories) should apply to the important issues that our American community faces today, and what solutions they imply. What would Jesus say about them? What actions would he take? How would he vote?

Background from the Prophets of Israel

What Jesus taught did not spring simply from his own imagination; it was the product of longstanding Israelite tradition, drawing especially upon the prophets in the early to mid- first millennium BCE. At that time, too many Israelites observed empty ritual and prayer and paid lip service to doctrine on the one hand, but actually behaved otherwise, contrary to God’s demands and expectations. The prophet Isaiah, for one, took issue with these folks (1:11, 15-16):

What to me is the multitude of your sacrifices?

says the Lord.

I have had enough of your burnt offerings of rams

and the fat of fed beasts . . . .

When you stretch out your hands,

I will hide my eyes from you;

Even though you make many prayers,

I will not listen;

your hands are full of blood.

Wash yourselves, make yourselves clean;

remove the evil of your doings

from before my eyes;

cease to do evil;

learn to do good;

seek justice;

rescue the oppressed;

defend the orphan;

plead for the widow.

The prophet Amos demanded the same (5:12, 23-24):

For I know how many are your transgressions,

and how great are your sins —

You who afflict the righteous, who take a bribe

and push away the needy in the gate. . . .

Take away from me the noise of your songs;

I will not listen to the melody of your harps.

But let justice roll down like waters,

And righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.

The book of Leviticus, written later, contains rules in line with what these prophets wanted (e.g., 19:11-17). Leviticus 19:10 says to leave some grapes from one’s vineyard for the poor and for the alien. And Leviticus 19:18 introduces a fundamental command, to love one’s neighbor as thyself, which Jesus famously taught (see below).

The import of these moral and ethical commands is that what a person actually does to make the world better is what is most important in order for him or her to be in the right relationship with God, not what one merely says; not just offering thoughts and prayers; and not just performing or attending religious rituals (in today’s world, such as just going to church on Sundays). You have to walk the walk.

What Jesus Taught and Did During His Life

Jesus saw himself as a prophet in the line of the above tradition of teachings. When a Pharisee lawyer asked Jesus what are the most important of God’s commandments in the Law, he replied that they are, first, to love God with all one’s heart, and second (which Jesus said is “like” the first), is to love thy neighbor as thyself (Matthew 22:36-39; likewise Mark 12:28-34; Luke 10:25-28; see also Gospel of Thomas, saying 25). In other words, loving God entails loving one’s neighbor, and vice versa. “On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets,” Jesus stressed (Matthew 22:40).

This principle finds expression in the more specific teachings of Jesus, as well as in his acts.

His Teachings

A threshold question that a lawyer asked Jesus was, “Who is my neighbor”? Jesus replied by telling the story of the good Samaritan (Luke 10:29-37). (Samaritans were not Jews, but were another ethnic group generally located in Samaria (the highlands of what is currently the West Bank of the Jordan); their religion differed somewhat from the Jews so they were not considered part of the House of Israel, were deemed ritually unclean, and thus were viewed as foreigners (gentiles). See, e.g., Luke 17:18.) In the story, a man traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho was robbed and badly beaten by robbers, who left him on the roadside to die. A Jewish priest and then a Levite passed by but ignored him, but then a Samaritan arrived, cared for him, and saved him. Jesus asked the lawyer which of the three was a neighbor to the victim. “The one who showed him mercy,” the lawyer replied. And Jesus instructed, “Go and do likewise.” Thus, the “neighbors” whom one should love are not restricted to those who share one’s religion or ethnicity. Jesus himself extended his ministry to foreigners (see below), and he declared that the worthy people of all nations would be gathered together in the Kingdom of God (Matthew 25:32).

Jesus taught that the Kingdom of God would be made up of those who loved God and their neighbors, like sheep who were separate from the goats. He taught that the Son of Man will explain to them, “I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me. I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me” (Matthew 25:35-36). Since the righteous listeners had never met the Son of Man, they asked how they could have performed these kind acts for him. He replied, “Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me” (Matthew 25:37-40). Loving one’s neighbor is to love God.

In his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus taught much the same:

Blessed are the meek,

for they shall inherit the earth;

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness,

for they will be filled.

Blessed are the merciful,

for they will receive mercy.

Blessed are the pure in heart,

for they will see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers,

for they will be called the children of God.

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’s sake,

for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

(Matthew 5:5-10)

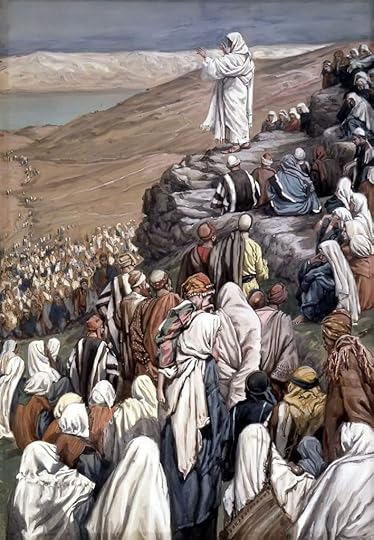

The Beatitudes Sermon by James Tissot (1890)

The Beatitudes Sermon by James Tissot (1890)His Actions

Jesus’s actions exemplified how God wanted people to conduct themselves and love one another. These deeds included:

Feeding the needy (Matthew 14:15-21; 15:32-39; Mark 6:35-44; 8:1-10; Luke 9:12-17; John 6:4-13)Healing the sick, and not shunning them (e.g., Mark 7:31-37)Throughout the canonical gospels, treating women as equals, and accepting them as his close followers; they played key roles in his ministry, and at his crucifixion and resurrection. See also the Gospel of Mary, in which Mary Magdalene teaches the disciples, since Jesus had recognized her as worthy, while the Gospel of Philip says that Jesus loved Mary Magdalene most of all, because she saw the light better than did the disciples.Not shunning but being kind to people whom most of society abhors (tax collectors, prostitutes, lepers, etc.)Paying special attention to widows (Mark 12:41-44; Luke 21:1-4), and condemning people who mistreat them (Mark 12:40; Luke 20:47)Paying special attention to children, and teaching that they are exemplary and to be emulated (Matthew 18:3; 19:13-14; Mark 7:27; 9:33-37; 10:13-16; Luke 18-15-16)Jesus also was kind to and performed beneficial deeds for foreigners. In John 4:7-26, he welcomed and taught a Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well, and revealed his messiahship to her (meaning that he could be the messiah for non-Jews too). He traveled to the region of Tyre and Sidon where he healed the daughter of a Phoenician (gentile) woman (Matthew 15:21-28; Mark 7:24-30). In Galilee, he received and taught “great numbers” of foreigners from Tyre, Sidon, and Idumea, from beyond the Jordan (Mark 3:8; Luke 6:17). In Matthew 8:5-13, a Roman centurion appealed to him to heal his servant, and Jesus did so, remarking, “in no one in Israel have I found such faith. I tell you, many will come from east and west and will eat with Abraham and Isaac and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven, while the heirs of the kingdom [of Israel] will be thrown into the outer darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.” So he placed foreigners of good will above unrighteous Jews. According to the Gospel of Philip, Jesus redeemed aliens and made strangers his own.

Like the above-mentioned Israelite prophets, Jesus scolded religious and political leaders who enjoy high positions and luxury, yet do nothing to help the plight of the needy and even prey on them (e.g., Matthew 23:1-12; Mark 12:38-40; Luke 11:42-52; 20:46).

What Would Jesus Say and Do Today?

In light of Jesus’s teachings and deeds, it is easy to see that he would be especially attentive to addressing similar issues that we face today, in the compassionate spirit in which he addressed them during his life, including:

Caring for the poor, orphans, and widowsProviding access to health care (including for mental health) regardless of income or wealth; ensuring food quality and product safetyEnsuring equality for women and protecting their rightsCombating racismProtecting civil rights and human rightsEnsuring access to justice in our legal systemEnsuring religious toleration (Christian exclusivity and intolerance (and Christianity itself) arose after Jesus)Respecting and valuing diversityProviding access to affordable education, so that all people can have better livesEnsuring fair treatment of immigrants (whether legal or not, and especially asylum seekers) and other foreignersProtecting our environmentLike in Jesus’s time, too often those in power (including some religious leaders) ignore these issues, while too many in our population (including many Evangelicals) nevertheless vote such individuals into public office; such candidates campaign on platforms that are opposed to the above values. And Jesus surely would not support the “prosperity gospel.”

How Would Jesus Vote?

Jesus’s truths and teachings are timeless, and indeed much the same are found in the world’s other religions and spiritual traditions. We must not lose sight of them in both our individual and national lives. Although Jesus did not get into politics, his teachings have obvious applications in our businesses, other institutions, politics and lawmaking, and the justice system. Many other countries are implementing these teachings and values in their national life better than we do here in America. Both Christian and non-Christian Americans should examine who among our existing and aspiring leaders are really embracing and acting in accord with Jesus’s teachings (and similar teachings in other religious and spiritual traditions), hold them to account, and vote accordingly when we go to the ballot box. And be activists in furthering these goals, as Jesus was.

October 27, 2022

The Mythology of Halloween

Boo! Earlier this week I did an interview with Esoteric Thoughts about the mythology underlying Halloween, which the interviewer just posted on his YouTube channel. Hope you enjoy it, and Happy Halloween. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J0MMRsUmDTQ&t=595s

May 8, 2022

Myth in Contemporary Society and Politics: The Short Version

In recent years we have seen increasingly strident, polarized, and factually false narratives emerge and circulate in our society and political life. This situation is confusing, and fractures our society and politics. We wonder how this all came about, and what we can do about it. In this series of posts on myth in contemporary society, I argue that this situation is most fundamentally understood by viewing it in mythological terms. We must recognize that myth is alive and well in modern society. Understanding how myths arise and function will better enable us to address this problem.

At the outset, let me say that myths can be either helpful or harmful, whether on the personal or collective level. As Joseph Campbell and other mythologists and psychologists have shown, myths can be important for positive and valuable personal and societal transformation. But in this series of posts I deal mainly with pernicious myths. We need to understand how these work too, in order to compare and contrast how myths can work for the good.

Historical Background

Historically, we have thought of myths as involving deities, heroes, the creation of the cosmos, other supernatural events, etc. These were traditionally the subjects of myths because for ancient peoples the natural world was mysterious and threatening; people were anxious and sought answers regarding how the cosmos and nature work. Myths arose to provide answers. Later, science answered many such questions, so hardly any new myths have arisen about such things. Other questions, such as what happens after death, remain, so we continue to spin out myths about those subjects. Even more questions, derived from the modern uncertainties in American and globalized culture, have produced additional myths, which are the main subject of this series of posts.

In the Age of the Enlightenment, thinkers hoped that the application of reason would lead to the end of myth. Over the past century, however, depth psychology on the one hand and postmodernism (or deconstruction) on the other have exposed what is now recognized as the “myth of mythlessness” in modern society. Aristotle called man “the rational animal.” Although, unlike other animals, we do possess highly developed reason, when it comes to our behavior, fundamentally we are mythmaking animals, and myths ultimately have non-rational origins in our unconscious psyche. Reason, which is a conscious function, often ends up operating in service of our myths, to support and elaborate them further, in order to make those within a community feel more secure with the community’s myth.

What Is a Myth?

With the above background, we can now consider an updated definition of myth. I like to define myth on the phenomenological level, by seeing what it looks like and how it works. (We can later and separately explore the underlying (e.g., psychological) explanations for it.) Here I offer a working modern definition:

A narrative (story) communicated, maintained, and further developed using symbols, imagery, and ritual, that becomes popular and important —often to the point of having a sacred quality — within a community because it reflects and resonates with the community’s fundamental concerns, thereby providing explanation, assurance, meaning, value, and often a model for behavior in both everyday life and community rituals.

Under this definition, a myth has at least the following key characteristics:

It uses symbols to best express things (especially subconscious contents) that are difficult to express in words. Accompanying rituals can do the same.It is a narrative. Symbols and images can operate as shorthand to convey the whole narrative or parts of it (e.g., the cross).Myth is a social phenomenon within a community. A story does not become a myth unless it is important – even sacred – and is embraced by a certain community. This means that the social psychology of groups is important.The definition accommodates communities of various sizes. For present purposes, the communities are largely subsets of America as a whole (e.g., evangelical Christians). Nowadays, such a community can be principally a virtual one functioning on the Internet.A myth provides the community with self-identity and meaning, comfort in the wake of disturbing emotions and events, and answers to questions of community concern. It also can model behavior. Myth-based rituals can arise.This definition is free from particular ostensible subject matter (e.g., gods). It is thus a functional definition that illuminates the perennial dynamics of myths that apply to any period in history as well as the present.It follows from the above definition and characteristics that it is difficult for people outside the community in which the myth arises to believe it. This can result in conflict, and underlies much of the polarization that we see today.

The Psychological Origins of Myths

According to depth psychology, myths and their symbols originate in the unconscious. As Joseph Campbell put it:

Myths . . . come from below the threshold of consciousness, as do dreams. They arise from down in the belly, from the source of the body’s energies. It is the business of the ego not to dictate to the self . . . , but rather to try to bring the impulse system into relationship with the conditions of the environment that the ego has constructed. Culture is the result of a cooperation between the self and the ego. Mythology is the language of the self speaking to the ego system, and the ego system has to learn how to read it. (Campbell lecture)

There are two sources of myths in the unconscious. First, they can arise out of the archetypes of the collective unconscious (Jung 1960, 152), which are evolved structures in our psyche that tend to produce instinctive patterns of behavior and mentality, in order to help us cope with typical situations in human life (mother and father archetypes, anima, animus, the shadow, etc.). “The archetype,” Jung explained, “is a kind of readiness to produce over and over again the same or similar mythical ideas” (1966, 69). According to Jung, the same basic archetypes are common to all humans. Second, myths can arise from complexes. Complexes can arise from archetypes, but they are more closely tied to an individual’s own life experience, so are more linked to a person’s personal unconscious, which is particular to each person (see Jacobi 1959, 6-30).

Both archetypes and complexes store psychic energy (libido). This energy is triggered by events in people’s lives that concern them, and it becomes conscious. It can be powerful, taking possession of one’s ego consciousness and overwhelming reason. In order for ego consciousness to understand and give meaning to this energy, the energy needs to take concrete form, in the form of symbols and narratives, yielding myths. Myths are fueled by psychic energy and take form through archetypes and complexes, yielding symbols and ultimately a story.

Because myths ultimately originate in the unconscious, at bottom they contain non-rational elements. Thus, myths inevitably to some extent depart from rationally derived, objective facts as known by our waking (ego) consciousness. Humans are naturally and unavoidably mythmakers. Thus, myths in society – even contemporary society – are inevitable. This means that it is incumbent upon us to learn to understand and deal with them in their own mythological terms, including the psychological aspects. If we fail to do so, mythmaking can spin out of control, which is what we see happening today.

What Triggers the Generation of Myths?

Myths usually don’t arise in connection with something well known and understood. Rather, they are connected with something unknown, mysterious, especially when such things give rise to fear and anxiety.

A good historical example is the nature of disease. Ancient peoples didn’t understand the cause of disease and feared it, so they attributed it to demons, other supernatural forces, sorcerers, and witches. They were also afraid that the sun wouldn’t rise tomorrow, that spring would not come again, or that wives would not be fertile, so they created myths to assure themselves that these things would indeed transpire.

Science has rendered myths about the natural world unnecessary, but people still have fears, anxieties, and uncertainties. Individuals and groups also have their shadows in the subconscious, as a result of which they create myths to explain away things and blame scapegoats. (I will cover scapegoating specifically in an upcoming post.) In recent years, we’ve seen this happening in myths about immigrants and minorities, Hillary Clinton, George Soros, Bill Gates, Covid 19, and just about anything touched upon by QAnon.

When investigating a crime, we often say, “follow the money.” When investigating a myth and its consequences, look for the underlying anxiety. As Carl Jung once advised, “Where the fear [is], there is your task!” (1976, 305) The key is to honestly confront and integrate the anxiety, not give in to it and let it run one’s life, or spin out compensating tales.

Social Aspects: Cultural Complexes and Myth Generation

While a myth may originate in an individual’s psyche, full-fledged myths have a collective, social character, and grow and flourish in communities. So the question arises of how myths transcend the individual and take hold in a community.

In recent decades psychologists, such as Thomas Singer and others, have developed the notion of “cultural complexes” within communities (see generally Singer 2004, 2019, 2020). They have discerned – in the psychology of groups – complexes, archetypal defenses, and notions of a group Self analogous to those found within individuals (Singer 2019). These factors facilitate myths taking hold and become important in supporting communities facing anxieties.

In order for a myth to take off in a community, it must resonate with the community’s cultural complexes. Otherwise, the myth will remain private to the individual. As a myth grows into the community, it will become more detailed and refined as the community’s conscious efforts develop it. In this process, the group’s complexes will tend to make the myth more strident and partisan, projections will proliferate, and scapegoats will become prominent. The myth thus hardens, and in strays further from factual reality. We end up with what Trump’s former advisor Kellyanne Conway called “alternative facts.”

Charismatic Leaders and Myths

Another aspect of the appearance and evolution of modern myths is the appearance of charismatic community leaders who symbolize the myth, propagate it, and elaborate it further. The leader does not necessarily invent the myth, but he recognizes it and senses how to redirect and exploit it for his own benefit. In this way the myth becomes central in politics. The myth grows through conscious group activity, steered by the leader. It feeds into and can pander to the cultural complexes of the community and indeed magnifies them into grand proportions. In due course, the leader personally becomes mythologized, often fitting into archetypes (e.g., father archetype, and the workings of the shadow archetype). Cult behavior and group hysteria can result (Jung 1964a and 1964b; Hassan 2019).

Images of Trump eerily like those of Big Brother, at the January 6, 2021, rally preceding the insurrection at the Capitol. A contemporary example of cult behavior based on a contemporary myth.

Images of Trump eerily like those of Big Brother, at the January 6, 2021, rally preceding the insurrection at the Capitol. A contemporary example of cult behavior based on a contemporary myth.Last century, prominent examples of such leaders were Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini, Chairman Mao, and Fidel Castro. Now leading examples are Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, who indeed have embraced each other. On our own far left, Bernie Sanders emerged as something of a cult figure with his enthusiastic band of followers, often known as Bernie Bros.

Where We Will Go from Here

The above background provides the basics that we can use to identify and analyze contemporary myths and their role in contemporary society and politics. In due course (no promises when!) I will analyze particular aspects and examples of recent and contemporary myths.

Sources and Bibliography

Campbell, Joseph. Lecture available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1hcogiUUNnM

Hassan, Steven. The Cult of Trump. New York: Free Press (2019).

Henderson, Joseph. Cultural Attitudes in Psychological Perspective. Toronto: Inner City Books (1984).

Jacobi, Jolande. Complex/Archetype/Symbol in the Psychology of C.G. Jung. New York: Princeton University Press (1959).

Jung, Carl. “The Structure of the Psyche,” in The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche. Collected Works, vol. 8 (1966), pp. 139-58 (cited as Jung 1960). Cites to the Collected Works are to page numbers, not the numbered paragraphs.

Jung, Carl. “Wotan,” in Civilization in Transition. Collected Works, vol. 10 (1964), pp. 179-93 (cited as Jung 1964a).

Jung, Carl. “After the Catastrophe,” in Civilization in Transition. Collected Works, vol. 10 (1964), pp. 194-217 (cited as Jung 1964b).

Jung, Carl. “On the Psychology of the Unconscious,” in Two Essays on Analytical Psychology. Collected Works, vol. 7 (1966), pp. 3-119 (cited as Jung 1966).

Jung, Carl. Letters: Vol 2: 1951-1961. East Sussex: Routledge (1976).

Singer, Thomas, ed. The Vision Thing: Myth, Politics, and Psyche in the World. New York: Routledge (2000).

Singer, Thomas, ed. The Cultural Complex: Contemporary Jungian Perspectives on Psyche and Society. New York: Routledge (2004).

Singer, Thomas, ed. Cultural Complexes and the Soul of America: Myth, Psyche, and Politics. New York: Routledge (2020).

Singer, Thomas. “Trump and the American Collective Psyche,” in Lee, Bandy, ed., The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump,” rev. ed., New York: Thomas Dunne Books (2019).

© Arthur George 2022

Myth in Contemporary Society and Politics: An Introduction

In recent years we have seen increasingly strident, polarized, and factually false narratives emerge and circulate in our society and political life. This situation is confusing, and fractures our society and politics. We wonder how this all came about, and what we can do about it. In this series of posts on myth in contemporary society, I argue that this situation is most fundamentally understood by viewing it in mythological terms. We must recognize that myth is alive and well in modern society. Understanding how myths arise and function will better enable us to address this problem.

At the outset, let me say that myths can be either helpful or harmful, whether on the personal or collective level. As Joseph Campbell and other mythologists and psychologists have shown, myths can be important for positive personal and societal transformation. But in this series of posts I deal mainly with pernicious recent and contemporary myths. We need to understand how these work too, in order to compare and contrast how myths can work for the good.

Historical Background

Historically, we have thought of myths as involving deities, heroes, the creation of the cosmos, other supernatural events, etc. These were traditionally the subjects of myths because for ancient peoples the natural world was mysterious and threatening; people were anxious and sought answers regarding how the cosmos and nature work. Myths arose to provide answers. Later, science answered many such questions, so hardly any new myths have arisen about such things. Other questions, such as what happens after death, remain, so we continue to spin out myths about those subjects. Even more questions, derived from the modern uncertainties in American and globalized culture, have produced additional myths, which are the main subject of this series of posts.

In the Age of the Enlightenment, thinkers hoped that the application of reason would lead to the end of myth. Over the past century, however, depth psychology on the one hand and postmodernism (or deconstruction) on the other have exposed what is now recognized as the “myth of mythlessness” in modern society. Aristotle called man “the rational animal.” Although, unlike other animals, we do possess highly developed reason, when it comes to our behavior, fundamentally we are mythmaking animals, and myths ultimately have non-rational origins in our unconscious psyche. Reason, which is a conscious function, often ends up operating in service of our myths, to support and elaborate them further, in order to make those within a community feel more secure with the community’s myth.

What Is a Myth?

With the above background, we can now consider an updated definition of myth. I like to define myth on the phenomenological level, by seeing what it looks like and how it works. (We can later and separately explore the underlying (e.g., psychological) explanations for it.) Here I offer a working modern definition:

A narrative (story) communicated, maintained, and further developed using symbols, imagery, and ritual, that becomes popular and important —often to the point of having a sacred quality — within a community because it reflects and resonates with the community’s fundamental concerns, thereby providing explanation, assurance, meaning, value, and often a model for behavior in both everyday life and community rituals.

Under this definition, a myth has at least the following key characteristics:

It uses symbols to best express things (especially subconscious contents) that are difficult to express in words. Accompanying rituals can do the same.It is a narrative. Symbols and images can operate as shorthand to convey the whole narrative or parts of it (e.g., the cross).Myth is a social phenomenon within a community. A story does not become a myth unless it is important – even sacred – and is embraced by the community at large. This means that the social psychology of groups is important.The definition accommodates communities of various sizes. For present purposes, the communities are largely subsets of America as a whole (e.g., evangelical Christians). Nowadays, such a community can be principally a virtual one functioning on the Internet.A myth provides the community with self-identity and meaning, comfort in the wake of disturbing emotions and events, and answers to questions of community concern. It also can model behavior. Myth-based rituals can arise.This definition is free from particular ostensible subject matter (e.g., gods). It is thus a functional definition that illuminates the perennial dynamics of myths that apply to any period in history as well as the present.The Psychological Origins of Myths

According to depth psychology, myths and their symbols originate in the unconscious, in at least two ways. First, they can arise out of the archetypes of the collective unconscious (Jung 1960, 152), which are evolved structures in our psyche that tend to produce instinctive patterns of behavior and mentality, in order to help us cope with typical situations in human life (mother and father archetypes, anima, animus, the shadow, etc.). “The archetype,” Jung explained, “is a kind of readiness to produce over and over again the same or similar mythical ideas” (1966, 69). The archetypes are common to all humans. Second, myths can arise from complexes. Complexes can arise from archetypes, but they are more closely tied to an individual’s own life experience, so are more tied to a person’s personal unconscious, which is particular to each person (see Jacobi 1959, 6-30).

Both archetypes and complexes store psychic energy (libido). This energy is triggered by events in people’s lives that concern them, and it becomes conscious. It can be powerful, taking possession of one’s consciousness and overwhelming reason. In order for our consciousness to understand and give meaning to this energy, the energy needs to take concrete form, in the form of symbols and narratives, yielding myths. Myths are fueled by psychic energy and take form through archetypes and complexes, yielding symbols and ultimately a story.

Because myths ultimately originate in the unconscious, they are at bottom non-rational. Thus, myths inevitably to some extent depart from rationally derived, objective facts as known by our waking (ego) consciousness. Humans are naturally and unavoidably mythmakers. This means that myths in society are inevitable. This means that it is incumbent upon us to learn to understand and deal with them in their own mythological terms, including the psychological aspects. If we fail to do this, mythmaking can spin out of control, which we see happening today.

What Triggers the Generation of Myths?

Myths usually don’t arise in connection with something well known and understood. Rather, they are connected with something unknown, mysterious, especially when such things give rise to fear and anxiety.

A good example is the nature of disease. Ancient people didn’t understand the cause of disease and feared it, so they attributed it to demons, other supernatural forces, sorcerers, and witches. They were also afraid that the sun wouldn’t rise tomorrow, that spring would not come again, or that wives would not be fertile, so they created myths to assure themselves that these things would indeed transpire.

Science has rendered myths about the natural world unnecessary, but people still have fears, anxieties, and uncertainties. Individuals and groups also have their shadows in the subconscious, as a result of which they create myths to explain away things and blame scapegoats. (I will cover scapegoating specifically in an upcoming post.) In recent years, we’ve seen this happening in myths about immigrants and minorities, Hillary Clinton, George Soros, Bill Gates, Covid 19, and just about anything touched upon by QAnon.

When investigating a crime, we often say, “follow the money.” When investigating a myth and its consequences, look for the underlying anxiety.

Social Aspects: Cultural Complexes and Myth Generation

While a myth may originate in an individual’s psyche, full-fledged myths have a collective, social character, and grow and flourish in communities. So the question arises of how myths transcend the individual and take hold in a community.

In recent decades psychologists, such as Thomas Singer and others, have developed the notion of “cultural complexes” within communities (see generally Singer 2004, 2019, 2020). They have discerned – in the psychology of groups – complexes, archetypal defenses, and notions of a group Self analogous to those found within individuals (Singer 2019). These factors facilitate myths taking hold and become important in supporting communities facing anxieties.

In order for a myth to take off in a community, it must resonate with the community’s cultural complexes. Otherwise, the myth will remain private to the individual. As a myth grows into the community, it will become more detailed and refined as the community’s conscious efforts develop it. In this process, the group’s complexes will tend to make the myth more strident and partisan, projections will proliferate, and scapegoats will become prominent. The myth thus hardens, and in particular strays from factual reality. We end up with what Trump’s former advisor Kellyanne Conway called “alternative facts.”

Charismatic Leaders and Myths

Another aspect of the appearance and evolution of modern myths is the appearance of charismatic community leaders who symbolize the myth, propagate it, and elaborate it further. The leader does not invent the myth, but he recognizes it and how to exploit and grow it for his own benefit. In this way the myth becomes central in politics. The myth grows through conscious group activity, steered by the leader. It feeds into and can pander to the cultural complexes of the community and indeed magnifies them into grand proportions. In due course, the leader personally becomes mythologized, often fitting into archetypes (e.g., father archetype, and the workings of the shadow archetype). Cult behavior and group hysteria can result (Jung 1964a and 1964b; Hassan 2019).

Images of Trump eerily like those of Big Brother, at the January 6, 2021, rally preceding the insurrection at the Capitol. A contemporary example of cult behavior based on a contemporary myth.

Images of Trump eerily like those of Big Brother, at the January 6, 2021, rally preceding the insurrection at the Capitol. A contemporary example of cult behavior based on a contemporary myth.Last century, prominent examples of such leaders were Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini, Chairman Mao, and Fidel Castro. Now leading examples are Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, who indeed have embraced each other.

Where We Will Go from Here

The above background provides the basics that we can use to identify and analyze contemporary myths and their role in contemporary society and politics. In subsequent posts I will analyze particular examples of recent and contemporary myths.

Sources and Bibliography

Hassan, Steven. The Cult of Trump. New York: Free Press (2019).

Henderson, Joseph. Cultural Attitudes in Psychological Perspective. Toronto: Inner City Books (1984).

Jacobi, Jolande. Complex/Archetype/Symbol in the Psychology of C.G. Jung. New York: Princeton University Press (1959).

Jung, Carl. “The Structure of the Psyche,” in The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche. Collected Works, vol. 8 (1966), pp. 139-58 (cited as Jung 1960). Cites to the Collected Works are to page numbers, not the numbered paragraphs.

Jung, Carl. “Wotan,” in Civilization in Transition. Collected Works, vol. 10 (1964), pp. 179-93 (cited as Jung 1964a).

Jung, Carl. “After the Catastrophe,” in Civilization in Transition. Collected Works, vol. 10 (1964), pp. 194-217 (cited as Jung 1964b).

Jung, Carl. “On the Psychology of the Unconscious,” in Two Essays on Analytical Psychology. Collected Works, vol. 7 (1966), pp. 3-119 (cited as Jung 1966).

Singer, Thomas, ed. The Vision Thing: Myth, Politics, and Psyche in the World. New York: Routledge (2000).

Singer, Thomas, ed. The Cultural Complex: Contemporary Jungian Perspectives on Psyche and Society. New York: Routledge (2004).

Singer, Thomas, ed. Cultural Complexes and the Soul of America: Myth, Psyche, and Politics. New York: Routledge (2020).

Singer, Thomas. “Trump and the American Collective Psyche,” in Lee, Bandy, ed., The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump,” rev. ed., New York: Thomas Dunne Books (2019).

© Arthur George 2022

December 28, 2021

My Interview about the Mythology of New Year’s just Posted on Esoteric Thoughts YouTube Channel

The YouTube channel Esoteric Thoughts just posted its interview with me about the mythology underlying the New Year’s holiday, which was based on my book, The Mythology of America’s Seasonal Holidays: The Dance of the Horae. You can watch it here. Enjoy. (Sorry about the poor lighting conditions.)

December 22, 2021

My Interview about the Mythology of Christmas Just Posted on YouTube Channel Esoteric Thoughts

I just gave an interview about the mythology of Christmas on the YouTube Channel called Esoteric Thoughts, which was posted on December 21, the occasion of the Winter Solstice. You can watch it here. I should also mention that exactly a year ago I gave a longer lecture on the mythology of Christmas (on Zoom, in my Covid haircut) at the Krotona Institute in Ojai, California, which is also on YouTube here. Please enjoy!

October 18, 2021

My New Mythology Article Just Published

The Westar Institute just published my newest article in the November-December issue of its journal, The Fourth R, pp. 3-7, 24 (attached below). It is entitled “Christmas, Easter, Myth, and Depth Psychology.” Based on the Easter and Christmas chapters of my recent book, The Mythology of America’s Seasonal Holidays, it explores the mythological and depth psychological underpinnings of these holidays. The Westar Institute is an organization of (mostly) secular biblical scholars dedicated to furthering religious literacy.

4th-r-34-6DownloadSeptember 30, 2021

Mythology of Wine Lecture, October 16

Hello wine and mythology enthusiasts! On October 16 in Oak Park, California, I’ll be giving a talk on wine mythology in the ancient world and early Christian Europe. It is hosted by an 80-member group of winemakers from the congregation of The Church of the Epiphany in Oak Park. They have a vineyard on the church property and make the wine right in the church! Needless to say, wine will be flowing at the event! If you would like to attend, please RSVP per the announcement below.