R. Mark Liebenow's Blog: Nature, Grief, and Laughter

November 30, 2025

We Don't Beat Cancer, We Endure

Getting the language right.

The language we use to describe cancer matters because it speaks of how we are choosing to deal with our cancer.

Some people describe their experiences with cancer as a journey. It’s definitely not a sprint because it goes on for far longer than we expected. Some describe it as a wilderness trek, like hiking the Appalachian Trail, because so much is unknown about what we will encounter along the way. There will be times when we’re exhausted and can’t take another step. There will be storms that batter us around, trails that end and force us to backtrack and find a new route, and large wild and hairy animals show up — a lot of metaphorical, Joseph Campbell stuff.

While some experience cancer as a thru-hike, starting at one end and hiking until they reach the other end months later, some people hike for a time (cancer treatments) and take time off (remissions) until they finish the trek years later. Others feel it’s more of a rollercoaster ride through hell.Has your journey been like the one that Bilbo takes in The Lord of the Rings with all of the horrible creatures like the Wargs, Orcs, and Ogres that want to whomp you with big, knobby clubs? Or is it more like Nan Shepherd’s relationship with the Cairngorm Mountains, the wildest in Scotland that has its own weather system? She kept hiking into them to discover what was there and discovered beauty within the harsh crags. For her, the goal was never about reaching the summit, but of finding a way to live with the mountains as part of her life.

How we talk about cancer is important because language helps us understand the reality of what is going on with us, or it can hide the truth from us. Is it battle or a relationship?

When we find the right words to talk about our cancer, we find it’s not as scary as when we began because we have pulled the immensity of cancer down into manageable words and regain a measure of control. When we can name it, we tame it.

When you have cancer, it’s tempting to say you’re in a battle with it. It’s easy to use military or sports terms to describe what’s going on because society speaks of it in this way. The terms are comforting in a back-handed way because they say we are doing something rather than letting things happen to us. The downside of using military terms is that when people die of cancer we blame them for not trying harder or for being weak. There is nothing weak about engaging in the struggle with cancer, and to say this negates all of our courage, strength, and resolve that is keeping us alive. And, if we feel we are losing the battle, or that we can never win, then we might give up trying.

For example, if you have prostate cancer, while military terms affirm the macho-ness of your manhood at a time when cancer is taking away what you think makes you a man — muscles, hair, a healthy libido — they divert you from paying attention to how you’re feeling. You also don’t let anyone in to help because this is your battle, you can handle it, and you push people away who want to help.

Doctors might describe what they are doing as fighting a war, with them on one side and cancer on the other, and bombarding cancer into submission with radiation and chemotherapy, but we, the patients, are the land between the two where the battle is taking place, and we want both of them to stop. To doctors, it may also seem like a chess match between Sherlock Holmes and Moriarty with patients being chess pieces on the board. The doctor’s goal might be to checkmate cancer and end the game, and sacrificing some pieces in order to win. But the goal should be to lose as few pieces as possible and reach a stalemate, to keep the game going until research finds a cure for those who have cancer and finds a way to prevent cancer from starting in others.

Eight years before Brian Doyle developed an aggressive brain tumor (either glioblastoma or ependymoma), he wrote an opinion piece “On not ‘beating’ Cancer” that was published in The Oregonian. He got fed up when yet another journalist talked about someone losing their battle with cancer. Doyle wrote that it’s wrong to describe cancer as a battle where there is a winner and a loser because there aren’t any. It’s about finding ways to endure. What “weapons” do we have to deal with cancer? Doyle says we have humor, patience, and creativity. You can read his article at this link: https://www.oregonlive.com/opinion/20....

Consider this imagery. If we talk about having cancer as being in a relationship with the ocean, then we expect to feel the natural ebb and flow of the waves of our situation. We expect to have good days and bad ones as we walk along the ocean shore. Storms will roll in and overwhelm us at times, but there will also be nights when an offshore breeze calms the ocean to stillness and we are mesmerized by the moon shimmering on the water.

Monica Berlin, a Knox College poet, wrote that it’s important we keep track and not “lose what is real in what is impossible. Everything is impossible.” Every great challenge seems impossible when we start out, including cancer. But that doesn’t mean we can’t find a way through cancer and continue to live our lives.

© 2025 Mark Liebenow

November 23, 2025

Cooking For Cancer

Karen Babine, All the Wild Hungers

Today I want to talk about Karen Babine’s All the Wild Hungers: A Season of Cooking and Cancer. Babine’s mother was diagnosed with a rare and deadly form of soft tissue cancer (embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma), and Babine copes with her anxiety by cooking. The book is accessible to everyone who is caring for a loved one who has cancer because we still have to eat to keep us healthy enough to care for them.

In 64 crafted micro-essays, Babine talks about her mother’s cancer treatments and about learning to cook with cast iron as she tries to make something that her mother can tolerate. Her thoughts on the devastating toll that cancer is taking are woven into reflections on the sustenance of nutritious food.

The ingredients that make up the book are well balanced. There is the cancer and cooking, of course, along with several recipes, but also Babine’s lyrical writing, a discussion of metaphors, humor, touching portrayals of her family, the historical view of the value of women to society, the color blue, ethical eating, the moral differences between agriculture and agribusiness, and insights into the culture of northern Minnesota. Having grown up in Wisconsin, I was intrigued that the stoic, non-emotive culture of Scandinavian Americans sounded much like the German American one I grew up in.

Like many books that deal with serious illnesses like cancer, this one is not filled with the medical details (although I wish they all would), and the main focus is not on the person fighting off death, but on Babine’s caregiving struggles to assist her mother. It feels like Babine is sharing with us as friends.

Now and then, Babine pauses in her narrative to face the darkness looming before her and wonder how long she can endure living with the uncertainty. She says metaphors can cover some of the unsettledness we feel when we don’t have enough facts but, ultimately, we have to let go of trying to control the situation and accept the unpredictability of life. The depth of her reflections is refreshing.

When we’re under stress like this, it’s helpful to do something physical. Babine finds release, and regains a measure of balance, by cooking and by shopping for additional antique cast iron pots and pans. She also gathers with her network of family and friends for support and to encourage one another.

Although we may not be able to stop the outcome of cancer, we can slow it down, and we can make the journey a little less painful. We can listen to the stillness between our fears and hopes, and do everything we can to take care of those who need assistance. We can feed the hungry and comfort those who are suffering.

Thanksgiving in the United States is this week. Find out who is hungry in your community and do something to help.

*

Because

Why do I share posts with you about people who are dealing with cancer? Because I want to express my gratitude to the people who take time to write honestly about their cancers. Because I find inspiration in the ways they discover for living with cancer. Because I like to learn about the different kinds of cancer, and the more medical details they share, the better. Call me a science-nerd. And because I want to pay homage to the wonder of every person who faces cancer and endures its gauntlet of treatments and the emotional tsunami that tosses them around. Their courage strengthens me.

November 16, 2025

Fear of Possibilities

Humans have a great ability to predict the future. We’re usually wrong. What we fear will happen often does not and it holds us back from living today with gusto. We live as people dead before we actually die. Which is almost the same thing.

A friend was recently diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. I wanted to tell her that everything would be okay, but I didn’t know this. No one did. I wanted to say something that would help, but from my time with people dealing with grief, I knew that my friend didn’t need platitudes. Words are no help right after someone receives the news that they have cancer. What she needed was someone to sit beside her for a time as the cold shadows of her fears drew near.

I know how it feels to sit beside the unbreathing body of a spouse, as well as by the bedside of a friend in a coma who is dying of brain cancer. Other friends have had to watch their spouses go through the regimen of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation as hope moved in and out like the ocean tide, and they walked along the shoreline between life and death and began to grieve the possibility of dying.A cancer diagnosis is no longer a death sentence, and my friend wasn’t on an automatic slide into passing. That’s one of the possibilities. What is different now is the awareness that she is finite. When we’re under the age of 60, we only footnote our eventual mortality. We expect to live decades of years more, and many of us do. A good number of us don’t.

Most of us understand the landscape of cancer in general terms. Doctors locate the problem, standard treatments are administered, and percentages of survival are given. You endure the treatments and go on with your life. If there’s still a problem, doctors try immunotherapy or targeting therapy drugs as you tread water, all the while wondering (continuing the water imagery) if you will ever stand on dry, solid ground again. I’ve had enough friends go both ways to know that this is a big unknown. And this is where my friend lives, enduring the physical trauma, the burning and nausea of chemotherapy, while waiting to find out what will happen to her. It’s a hard place to live in for very long.

When we don’t know which path we are on, we want reassurance. With my cancer, I needed to hike in the woods to see the beauty of the nature and be reminded that I liked being alive. I needed to know that wonders still existed. I wanted to feel the hope that lived beyond my fears, and I didn’t want the possibility of death to put a damper on the sharing of my heart.

I sat with my friend later and we talked about her life, the dreams she didn’t know if she would ever accomplish, her tiredness of living with the stress, and about some of her regrets in life, which she was grateful for because they taught her things she needed to know. When we find out which direction her future is going to head, then we will talk about that.

What we have is today, and today we choose to live.

© 2025 Mark Liebenow

November 9, 2025

It Sits Between a Man's Bladder and His Old Feather

My title is a quote by Stephen Fry who was treated for prostate cancer and bemoaned men’s reluctance to talk about the prevalence of the cancer simply because it involved their penis.

Mark Shanahan interviewed Fry for his video series for The Boston Globe that first aired in 2020 and was updated in 2025. It’s a six-part series that is informative, hugely funny, and quite personal. The interviews with leading cancer doctors, including Dr. Drew Pinsky, are filled with details about how treatments have greatly improved since the 1980s.

Although Shanahan’s father was treated for prostate cancer, they had never talked about it, and Shanahan knew little about the cancer, what the prostate did, where it was located, or that it was the size of a walnut. In 2014, when he was only 48, his doctor noticed that Shanahan’s PSA was elevated, and it continued to rise over the next eighteen months. A biopsy revealed a Gleason 7 score that indicated he had an “intermediate risk cancer.”Because of his family history of the disease, rather than wait to see if it got worse, Shanahan decided to go ahead with surgery. Unfortunately, the surgeon found the prostate was “mushy” and wasn’t sure he got it all. He could have taken more tissue, but Shanahan had said he valued his sex life and didn’t want to risk losing that, so the doctor didn’t remove more of the margins. The pathology report indicated that surgery hadn’t gotten all of the cancer. The doctor put Shanahan on the anti-hormone drug Lupron and sent him through seven weeks of daily radiation to make sure he got all of the cancer.

As designed, the Lupron took Shanahan’s testosterone level down to zero. This causes some men to have large mood swings, which is what it did to Shanahan. He said he was sometimes out of control, ranted over little mistakes, driven to near madness by the unbearable hot flashes, and he inexcusably inflicted his temper tantrums on his family. Acupuncture helped calm his hot flashes and restored him to some sort of sensible sanity.

One of Shanahan’s regrets was not going to a prostate cancer support group before he decided what to do about his cancer, and then during treatments, because he found out, as he was doing research for his report, just how supportive and informative such groups are.

Now, trucking along post-treatment, he continues to be checked yearly. While he is relieved to have the cancer gone, he is dreading the possibility of its return, because cancer too often does.

Quite a few topics are covered – how men anchor so much of their identity in a working penis, how the development of the PSA blood test was a game changer because digital rectal exams aren’t very accurate, the overreaction of some men with a higher than normal PSA by demanding treatments when they could have simply waited to see if something did develop because most prostate cancer is slow growing, and the disturbing reality that Black men have a higher rate of getting prostate cancer and a higher rate of dying partially because of heredity and diet, but also because of unequal medical care and a learned distrust medical people because of experiments done on Black men in the past.

Cancer research continues to make important improvements in treatment options. I don’t recall if Shanahan had an MRI to determine if all of his cancer was still contained in his prostate before he had surgery, but it wasn’t until the development of the PSMA-PET scan in 2020 that doctors could tell if cancer had moved beyond the margins of the prostate, which is how I found out about the aggressiveness of mine. If Shanahan had known the cancer was already outside, he could have skipped the surgery, with its potential long-term side effects of incontinence and erectile dysfunction that plague a large percentage of men, and gone directly to radiation and the hormonal sleighride of the leuprolide (Lupron).

The “Mr. 80 Percent” video series is a really good overview, and I recommend it. On the internet, type in “Mark Shanahan prostate cancer” and it will show up.

Men should be less uptight about talking with others when their down under equipment is having problems. There is no shame in having prostate cancer or in getting treatments for it. There is also no shame in doing nothing and dying, but then … well … you’re dead.

© 2025 Mark Liebenow

November 2, 2025

Hope Is

Hope is the thing with … barbed wire.

Hope definitely doesn’t have FEATHERS, all fluttery and light, although it might if a circus clown like Emmett Kelly is trying to sweep up a spotlight with a feather, making us feel sad at his seemingly impossible task. I want something solid.

Hope is a great stone mountain that doesn’t move. It’s the bright North Star in the night sky that I know will always be there, even if I can’t see it because of the clouds.

Hope is barbed wire because just when I think I’m done with life, that nothing is left and I’m about to take my leave, hope snags my flesh and pulls me back. Or, if you prefer a less painful image, when we leap from a bridge, hope is the bungee cord that stops us from smashing on the rocks below. Maybe something will happen that I can’t anticipate, something that I don’t even realize is possible. It’s not like I know everything that goes on in the Milky Way. I’ve been gobsmacked by surprises in the past, and I’m willing to be smacked again.

It was Emily Dickinson who wrote the line “Hope is the thing with feathers.” I had been focused on the feathers, but when I read the entire poem, I discovered its context. Dickinson isn’t speaking about the feathers as much as she is speaking about the THING that has feathers, and the thing is the bird that continues to sing even in the onslaught of a storm when its song can barely be heard through the blustering wind and driving rain.

When we have cancer, we carry hope in our heart’s cage. It’s what we feel when we hear the voices of children singing, what we see in the eyes of physicians and nurses as they care for the sick, and what we feel in the touch of a friend’s hand on our shoulder after a hard day of being battered about by our treatments.

Having hope in a time of struggle may not change anything medical, yet hope is what gets us through the rough times when our confidence has been shredded by the ongoing mental trauma, when some of our friends desert us because they are tired of hearing about our cancer and they have their own problems to take care of. Having hope is what spurs us to keep trying. Hope reminds us to hang on because, just maybe ….

Hope is not tied to what goes on in this world. It is neither reduced nor expanded by the world’s problems or celebrations. It is never used up. It endures. Hope is a conviction. It’s more than a wish when I say, “I hope you have a good day.” Because I mean GOOD in the sense of something happening, even if it’s small, that will leave a warm glow in your chest and a bounce in your step.

For two years my radiologist and oncologist have denied that their radiation or anti-hormone drugs could have caused the gluten sensitivity that left me unable to eat bread, pie, cookies, or pasta. Then cancer dietician Sydney said that she had heard of this happening and had an idea. She gave me hope, and her idea worked.

Sometimes hope is the only thing that keeps us tethered here. By not giving up at something that seems insurmountable, Emmett Kelly does the impossible. He sweeps up the spotlight and takes it home with him.

Be the bird singing in the storm.

© 2025 Mark Liebenow

October 26, 2025

A Lifespan of Width

Andrea Gibson, You Better Be Lightning, 2021

Reading the poetry of Andrea Gibson is like coming out of a thick, brambled forest and seeing the beauty of the mountains rising all around you.

Andrea Gibson (they/them) died in July 2025 at age 49 after four years of dealing with ovarian cancer, but cancer will never be Andrea’s story. Before this, Andrea struggled with the serious side effects of Lyme disease and this ushered in a deeper understanding of the suffering that others go through because of chronic illnesses and disabilities.

I’ve read only a few of Andrea’s cancer poems because they haven’t been published in a collection, and I long to read more. In the stunning poem “In the Chemo Room,” Andrea takes off the ice mittens to preserve their fingernails to write “I could survive forever / on death alone. Wasn’t it death that taught me / to stop measuring my lifespan by length, / but by width?”My only qualifications for speaking about Andrea’s work come from having aggressive cancer and writing poetry. Andrea’s words reach past the cotton bumpers and the sound walls we put up around us to protect us from pain. With cancer there is no running from, only running to, and Andrea encourages us to claim the courage that we carry in our hearts and find life within the darkness.

What surprised me is that Andrea opened to happiness because of cancer instead of closing down in anger, frustration, and depression. Although I’m sure that Andrea felt them, I think they realized that writing about them did not help anyone, but affirming what was still good and beautiful about life could. This is Andrea’s story.

While working with a therapist to help themself feel and honor all emotions, Andrea realized that they had never let themself feel happiness until they had cancer. This door opened, and the gratitude they felt began to permeate their poetry.

After three years of continuous chemotherapy, Andrea left the clinical trial because of the toxic effects on the body and wrote the poem, “What’s Real,” about the struggle between the mind and heart to decide what is true about reality, and what are only presuppositions. I like the lines, I hold “a stethoscope to my pain / and [hear] the heartbeat of the whole world.”

The author of seven books, Andrea’s last book of poetry, You Better Be Lightning, was published in 2021, right when they were being diagnosed with cancer. Andrea began an experiential blog on Substack called “Things That Don’t Suck” to affirm the good things and to share their journey with cancer. The writing is filled with insights, wisdom, humility, and inspiration for those who are dealing with any serious health problem, and they challenge us to care about those who are suffering and live on the margins.

Andrea performed poems on stage, so the poems tend to be long. Often they are monologues where rhyme shows up now and then, and rhythm builds on the cadence of image after image. There are quite a few videos of the performances, and they are witty and understanding, connect concrete things with ideas (“keep a roof over the head of truth”), and riff on topics that cut through the dross of life and get down to the bare metal of living — suffering, community, and justice. Andrea’s poems say we can feel gratitude even when we have cancer, and I need to be reminded of this on my hard days.

Ovarian cancer is the 11th most common cancer among women, but the 5th leading cause of cancer-related deaths. In their lifetime, 1 in 91 women will get it. By way of comparison, 1 in 8 American women will get breast cancer. Ovarian cancer is hard to diagnose because the symptoms are generic, and most cases are diagnosed at Stage 3 or 4 when survival is less likely. In the 1990s, quite a few women were still dying only one year after diagnosis, but survival in the last thirty years has greatly improved because of cancer research. The 5-year survival rate is still only 50% because of being detected in the later stages. If it’s found early, 92% survive five years. If found in Stage 4, survival falls to 30%. Older women are more likely to develop the cancer, and having the BRCA-1, BRCA-2, or Lynch syndrome genes increase your risks.

The list of famous women who died of ovarian cancer include Gilda Radner, Madeline Kahn, Dinah Shore, Coretta Scott King, Rosalind Franklin, Joan Hackett, Sandy Dennis, Laura Nyro, and Jessica Tandy. Some of the women who are surviving include Cobie Smulders, Kathy Bates, and Christiane Amanpour.

Megan Falley, a poet and Andrea’s wife, said a lot of Andrea’s words have yet to be published, including a memoir, half-finished poems, and a bunch of late night thoughts recorded on Notes. Megan not only has to deal with her grief, she also has to face deepening her sorrow as she sifts through, rereads, and prepares the words of struggle and hope that were written by someone she loved.

October 19, 2025

Maybe Dying, Maybe Not

“I am going to die.” We took a poll in my cancer support group, and that’s what each of us thought when our doctors said we had cancer.

As it is for my friends, the thought of dying is never far from my mind. It is a possibility, and my oncologist hasn’t said that I’m not, so I exist in a netherworld where I hold my breath and wonder when it will happen and how. He actually thinks I’m doing quite well. He said so, after I asked, because the dread of dying was weighing heavily on me that day.

Of course, after I left his office, I wondered if I was “doing quite well” only in comparison to other men in my situation. I noticed that he didn’t say my cancer was gone, which is what I really wanted to hear, and he didn’t give a date when he would know. Maybe he’s seen the cancer in too many men take a wrong turn. Men with high risk, aggressive prostate cancer like mine do die, and some do so unexpectedly.Data points stick in my head from the reading I’ve been doing trying to comprehend the conundrum I’m in, like how forty years ago men with advanced prostate cancer would be dead in two years, and how twenty years ago men whose cancer had metastasized and were being treated were dead in three. Because of advances in cancer research, metastatic men are now living for five years and beyond. So there is hope, and I cling to this.

I’m not metastatic or Stage 4 but it doesn’t feel like I’m out of the woods yet because I’m a high Stage 3b. A year ago my medical oncologist had to do a quick retest of my PSA after six weeks because my PSA number jumped and this surprised him. Generally he runs this blood test every three months. If the results are good, then I know I have another three months when I don’t have to worry. Since then, my PSA has continued to bounce around and I go into every doctor’s appointment with trepidation.

If I’m only “maybe dying,” can I write perceptively about what dying feels like? Can I talk about the anguish of listening for the last time to crows cawing in the woods today if there’s a chance that I might return and listen to them again? When the Buddhist bell clangs to guide the dying home, am I allowed to listen if I’m not sure I’m going?

Would my focus change if I knew for sure that I was dying? Yes. It would also change if I knew for sure that I wasn’t. Until I know otherwise, I am going to focus on what is going right and celebrate every good thing I can find.

I’m fascinated with the stories of people who knew they were dying of terminal cancer and took the time to write about their experiences because they provide a view into the unknown land I’m facing. Their words bite with insights. They speak of the light in the sky being opaque, of colors becoming brighter, of images sharpening and deepening in meaning, of life slowing down to where they notice small items of beauty around them that they had missed before, and how many of the tasks that they used to stuff into their days really don’t matter. They also speak of the shadows that appear along the edges.

The writers I’ve come to value include the poets Ilyse Kusnetz, Julie Hungiville Lemay, and Katie Farris. Kate Bowler writes about dying, too. She had Stage 4 colon cancer and lived two months at a time between her check-ups. Experimental immunotherapy in a clinical trial brought her situation under control, although it didn’t for many others in the study and they died. She details this in No Cure For Being Human, her second book on her cancer treatments. She will be monitored for the rest of her life.

Andrea Gibson dealt with the physical and mental depletion of Lyme disease before ovarian cancer showed up. Andrea confessed that the one emotion they had never let themself feel before getting cancer was happiness, and they began to embrace this as they were dying. Andrea’s poems ring with the encouragement to live every moment of every day you have.

When you have cancer, you live in a worry castle. What would you do if you thought you might be dying? Would you start saying goodbye as you inch towards the door, or would you push the hope endorphins and begin to plan what you’re going to do when you’re cured? As you wait, since there’s not much else you can do except worry, you try to be helpful to others who are suffering, and you try not to think that every new pain is your cancer growing. We took a poll on this, too.

Because cancer and the treatments made me dependent on others for help, and the anti-hormone drug loosened up my emotions, every unexpected act of kindness moves me to tears. It’s sometimes embarrassing. I don’t know at what point the fear of dying will go away. If my cancer is determined to be gone, I will take stone of fear off the desk in front of me, where it’s been sitting for three years, tuck it into my pocket, and go on living knowing how easily everything can change.

October 12, 2025

A Spouse's Journey Through Cancer

Elaine Mansfield, Leaning Into Love

Elaine Mansfield is honest in her book about her husband Vic’s struggle with lymphoma. She writes of her growing fatigue from being his constant caregiver over the years, and then, after his death, of learning to live with the emptiness of the home they shared.

What I look for in a memoir about cancer and grief is honesty. I don’t want sugar. Sugar doesn’t give me real hope. Sugar melts away when tears begin to fall. I want truth because I want to learn about the stress and despair that caregivers have to endure as they take care of someone with terminal cancer, and I want to know how she survived when the future she dreamed about was taken away.

Even with people who are as determined as Elaine and Vic, cancer often wins the physical battle. Elaine writes of her struggle to hold on as hope in his survival began to fade and her longing to let go because she was exhausted and coming apart as she kept pushing herself to help Vic keep going. After he dies, she wrote, “His gentle passage opens my heart and stills my mind” She bends but does not break: “The downward pull of grief persists, but I often touch the slippery edge and rise above instead of being sucked under.”

The book is divided into Before and After, with death as the turning point. There are no magic words here that will erase cancer’s trauma on families or ease death’s sorrow, but she offers insights — stay attentive, do not give up when treatments go on for longer than you expect, screw up your courage and do what needs to be done, even if it scares you, even if you are resentful.

After Vic’s death, Elaine began writing about their shared journey with cancer as a way as understanding what went on. She describes how tired she was as Vic increasingly needed more medical care, the late night dashes to a distant hospital, and the lack of time to do what she needed to do to recharge her energy. She acknowledges her feelings of guilt when she takes time for herself instead of doing another small thing for Vic that he would enjoy. Elaine writes, “If we dare to love, then we will grieve. Mortality is the shadow that falls when the sun shines.”

Sprinkled through the narrative are the words of Elaine and Vic’s spiritual mentors — Anthony Damiani, Marion Woodman, and the Dalai Lama, as well as words from the poems of Rainer Maria Rilke and Naomi Shihab Nye, including Nye’s astounding “Kindness” poem.

Elaine finds solace in the woods after Vic’s passing. She writes of her desire for daily exercise and cooking healthy food, even though, on some days, these are the last things she wants to do. She writes of her ongoing practice of meditation and spending time in solitude. She speaks of volunteering to help with a hospice group, and of the support she received from her community of friends, both during Vic’s illness and after his death.

Cancer and the death of a spouse change our lives and sends them in a different direction. Six weeks after Vic died, Marion Woodman wrote to Elaine: “Something is emerging that could not have happened in your old life.” Each year Elaine raises Monarch butterflies, watches their transformation from caterpillar to butterfly, and feels her own life undergoing a similar transformation.

Elaine’s words move with the flow of a powerful river that carries us into a deeper understanding of life.

© 2025 Mark Liebenow

October 5, 2025

Troglodytes of Whimsy and Mercy

Brian Doyle, writer. Age 60. Dead of aggressive brain tumor discovered only six months earlier.

Stark details, and all too familiar. They don’t say anything about who Brian was. How he wrote in a way that made grown men drool and old women swoon clutching their rosaries. How he touched the lives of thousands of people who knew him or read his words. He was reverent and irreverent, often in the same sentence. Insightful. Optimistic. Funny. Stuffed full of heart and faith. An artist with words that stunned with their lyrical beauty.

Brian and I corresponded lightly over his last couple of years. This is not important because I suspect he did this with many people. He was generous in this way.My introduction to him began when I stumbled over his essay “Playfulness” in River Teeth Journal. I really liked it but, at that point, I didn’t spark to his name. I liked it so much that I began paging through my other journals and Best American anthologies to see if he had written anything else. He was in most of them, too, and I had dog-earned those pages, but not remembered his name.

I thought this was funny, so I wrote about it and sent Brian a copy to make sure it was okay to publish. I figured he was a big fish in the essay world and I didn’t want to piss him off. He wrote back, no caps: “o gawd that made me laugh.” With his blessing, the piece was published by Burlesque Press.

(“Dear Famous Writer” https://burlesquepressllc.com/2014/01... )

At the University of Portland, where he worked as editor-in-chief of the Portland Magazine, he also did things like sponsor the “Brian Doyle Scholarship in Gentle and Sidelong Humor.” As a nod back for all the times he made me chuckle, I made donations to his cancer fund from the Brian Doyle Cricket Club, then the Hedge Trimmer Hobbits of the Who Dunnit. the Ambidextrous Thinkers of America, the Hairy Kloggers of Laughter and Light, and finally the Troglodytes of Whimsy and Mercy.

Our last correspondence was over a manuscript on the spirituality of nature I had written. I sent it to him, he suggested places to submit it, and offered to write a promo when the time came.

Brian knew the darkness of humanity, but he also celebrated its great, creative, and wondrous joy. He held fiercely to his faith in things unseen, believing that, even in the midst of the cruelest tragedies, the holy was still present, and its mystery holds us up until we are able to walk on our own again.

Now and then we discover someone who writes what takes our breath away, who props us up on bad days when we are sliding into despair, and who makes us believe in goodness again. And then they’re gone. They’re always gone too soon.

“Writing is a time machine,” Brian said. I suppose that is why I write about cancer, grief, and dead people, having lost friends, parents and a wife, because writing keeps them alive. Brian said, “writing gives death the finger.” So it does, and so do I.

© 2025 Mark Liebenow

September 28, 2025

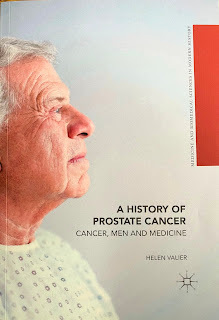

Prostate Cancer Has A History

Helen Valier, A History of Prostate Cancer, 2016, Palgrave MacMillan.

This is the best book I’ve found that covers the scope of prostate cancer—history, treatments, and research. While quite a few articles exist elsewhere that deal with the topics in specific ways, Helen Valier has brought everything together, and her book answers most of my questions. I say most because her book came out in 2016, and medical advances have continued to occur over the last nine years. One example is the development of the PSMA-PET scan that can detect trace amounts of cancer cells that traditional scans like the MRI and CT miss.

The book covers the entire history of prostate cancer, what physicians in ancient times suspected what was going on, how the cancer was treated through the centuries, the struggles of doctors to find solutions and a cure, and the big debate that we continue to struggle with is over whether it’s better to catch the cancer early through prescreening and use of the PSA blood test, and get some false-positive results, or wait until symptoms show up, when the cancer might have already spread into the lymph nodes and bones. Doctors have differences of opinion about this. So do patients.The chapters cover the problematic prehistory of prostate cancer, surgery and specialization, sex and hormones, clinical trials, screening and the politics of prevention, and radiation therapy.

The main drawback with the PSA is the false-positive result, which cause men anxiety. Yet if your PSA is high, then doctors do a digital exam, and if that indicates something, then they do a biopsy to find out what you’re dealing with. The Gleason score that comes out of this determines the level of treatment you need to get. If it’s a low score, you probably have the wait-and-watch variety of prostate cancer and nothing needs to be done. A high score indicates that your cancer is aggressive and something does need to be done now.

The risk with having a higher than normal PSA is that some men overreact when they’re told they have cancer and demand treatment right away, when in reality their cancer is actually low-risk and they simply have to watch to see if their PSA number jumps. There are definite risks to the treatments because they can have serious side effects, some that do not go away. Doctors can also over-diagnose and do more than is necessary as they try to be proactive. Patients need to be aware of these matters and decide the level of risk that they are willing to take on.

If the cancer has remained within the prostate, the standard course of action is surgical removal of the prostate. If cancer cells have moved locally outside of it, like into a seminal vesicle, then doctors do a combination of hormone therapy, brachytherapy, and several weeks of daily external radiation. If cancer has metastasized into your lymph nodes or bones, then you head off on a different course of treatments, with genetic and genomic / somatic testing to help determine your specific therapies.

While the book focuses on the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer over the years, the patient side of the equation is not often dealt with. Valier acknowledges this and says that other historians can explore this aspect. She does provide one example, though, which is enough to give me hope for my aggressive cancer. Her father’s cancer wasn’t found until it was Stage 4 and in his bones. He began treatments and was doing well ten years later.