Evangelos Simoudis's Blog: Re-Imagining Corporate Innovation with a Silicon Valley Perspective

October 28, 2025

From Conversation-Centric to Agent-Centric AI Models

Enterprises have accelerated their efforts to integrate AI into operations. More recently, many have launched pilot projects to develop agent-based systems across various domains. Most of these agents rely heavily on the capabilities of conversation-centric foundation models such as GPT or Gemini. But as we deploy more capable agent-based intelligent applications, we must utilize agent-centric models for reasoning, planning, coordinating, and learning. Such agents will need to incorporate neurosymbolic components that access Large Reasoning Models, Large Action Models, and other such agent-specific models. Instead of communicating using natural language, as is the case today, multi-agent systems will need to communicate using specialized languages in conjunction with appropriate communication protocols.

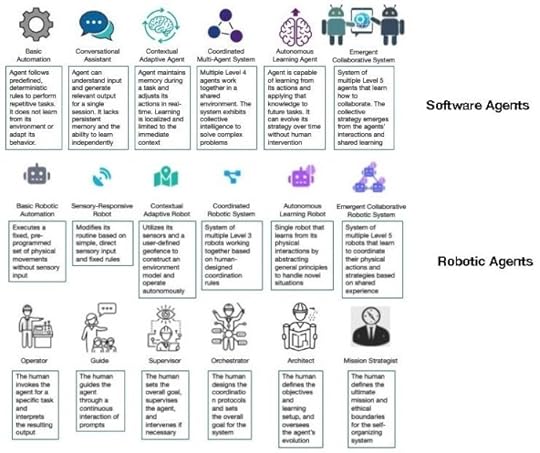

The Models Agents UseIn a recent post, “Evolving the AI Agent Spectrum from Software to Embodied AI,” I arranged AI agents along a six-level spectrum based on their capabilities. In that framework, I explained how agents advance from simple, software-based assistants (Level 1) to embodied, fully autonomous agents (Level 6).

Today’s conversation-centric LLMs support the Level 2 agents, which mainly interpret and respond to human instructions using natural language. They can automate routine tasks, assist with information retrieval, and aid decision-making through conversational interfaces. For example, a Level 2 “HR agent” that accesses a conversation-centric foundation model can be used to screen candidate resumes for a particular corporate position. Similarly, a Level 2 “paralegal agent” can be used to review corporate contracts.

As enterprises advance to Level 4–6 agents, the primary focus of LLMs, which is linguistic fluency, will fall short for tasks involving multi-step reasoning, autonomous actions, and coordination among agents. For instance, consider a comprehensive multi-agent predictive maintenance system used in manufacturing. Its agents need to predict equipment failures, dynamically reschedule production, order parts, and work together with robotic systems. Achieving this requires two distinct types of AI models:

Large Action Models (LAMs) for operational intelligenceLarge Reasoning Models (LRMs) for reasoning and planningNeurosymbolic components that are part of these higher-level agents utilize such models to accomplish the tasks assigned to them.

Large Action ModelsOver the past year, we have witnessed the rapid rise of LAMs. This is a new class of AI models designed to translate perception and context into action. LAMs generate actions enabling agents to plan and execute complex sequences of operations in both digital and physical environments.

Large Action Models model relationships between states, goals, and actions. They learn from interaction data, such as API calls, robotic control signals, and software operations, rather than from static text. These models learn “how” to act in context, integrating perception (what’s happening), reasoning (what should be done), and control (how to do it).

Google DeepMind’s RT-2 and NVIDIA’s Cosmos platform are state-of-the-art LAMs.

Large Reasoning ModelsTo enable the transition to Level 5 (Autonomous Learning), agents need specialized cognitive structures provided by Large Reasoning Models. LRMs provide the cognitive component powering LAMs. They have been architecturally structured and specially trained for deliberation rather than general conversation.

They utilize formal deliberation techniques such as Tree-of-Thought (ToT) search, allowing the model to explore multiple potential solutions, evaluate their logic, and select the safest, most robust path. LRMs are engineered to move beyond pattern-matching (situational adaptation) to abstract deduction, enabling an agent to act effectively in novel situations, which is the defining characteristic of Level 5 autonomy.

The Language of CoordinationUsing natural language for inter-agent communication in multi-agent systems is ineffective. Natural language is too slow and ambiguous. Inter-agent communication must prioritize efficiency and precision. Instead, agents must communicate using standardized data structures that explicitly articulate the message’s intent and content, replacing verbose text with high-bandwidth, structured exchange.

Agent Communication Languages (ACLs), such as KQML and FIPA, require that every message must contain an intent and a structured content payload. Agents exchange formal commands like (REQUEST :sender SchedulingAgent :content check_part_availability), which is unambiguous and instantly machine-readable.

The structured messages are governed by protocols that enforce reliability and security, enabling agents to coordinate. The Agent-to-Agent (A2A) Protocol standardizes the secure and reliable transfer of structured messages between agents. This is a necessity for Level 4 and 6 multi-agent systems. In such systems, agents from different enterprise applications, e.g., the Maintenance Agent and the ERP Ordering Agent, must collaborate seamlessly and maintain context across long-running workflows. The Model Context Protocol (MCP) standardizes the “model-to-tool” interaction. It ensures that an agent always supplies its underlying model with the necessary tools, memory, and grounded context. This results in reliable responses. MCP helps guarantee the stability and non-hallucination of the reasoning process.

Bridging LLMs and LAMs in Enterprise AIConversation-centric LLMs will continue to facilitate human-agent interaction, while LRMs/LAMs will handle planning and execution. Enterprises are experimenting with this paradigm in areas such as customer service automation, industrial maintenance, and digital operations. Over time, this integration could evolve toward agent-centric foundation models that incorporate conversational, perceptual, and operational intelligence. Such models would be capable of reasoning about both language and action within the same semantic framework. They would enable autonomous collaboration, long-term memory, and adaptive decision-making in dynamic enterprise environments.

As Professor Gary Marcus recently argued, the future of AI lies in specialized systems that integrate multiple forms of reasoning rather than relying on monolithic general-purpose models. Agent-centric foundation models embody precisely this vision. They move beyond general language understanding toward contextual, action-oriented intelligence to make consequential decisions.

Looking AheadEnterprises will transition from today’s AI-enhanced monolithic applications to AI-first multi-agent systems that will utilize agent-centric models. The emergence of agent-centric models signals the emergence of cognitive infrastructures in the enterprise. These infrastructures will integrate various model types (LLM, LRM, LAM) with neurosymbolic reasoning components and formal communication protocols (A2A, MCP). Enterprises that succeed in this transition will understand and respond to their customers’ and users’ intents accurately, efficiently, and safely.

The post From Conversation-Centric to Agent-Centric AI Models appeared first on Evangelos Simoudis.

September 25, 2025

Preparing the AI-First Enterprise Workforce for the Age of Agents

As AI agents become more capable, how should the roles and responsibilities of the AI-first enterprise employees evolve? Which skills will matter at each level? How will technical and business teams collaborate to effectively leverage agents and agent-based systems? As the capabilities of agents advance, employees will move from executing tasks to supervising workflows, orchestrating agent collectives, and setting mission-level strategy. Preparing for this transformation requires a clear view of how roles evolve across the six levels of AI agents, and how responsibilities will shift among AI specialists, application users, and supporting teams.

IntroductionIn previous posts, I outlined a spectrum of AI agents for the AI-first enterprise, describing the capabilities of agents at each level and how they impact the workforce. I also highlighted level-specific design patterns that AI-first enterprises can use when deploying agent-based systems. Yet an AI-first enterprise is not defined only by how advanced its software and robotic agents are. Its success depends equally on the humans who develop, interact with, guide, and orchestrate these agents.

This raises an urgent question: as AI agents become more capable, how should the roles and responsibilities of the AI-first enterprise employees evolve? Which skills will matter at each level, and how will technical and business teams collaborate to effectively leverage agents and agent-based systems? As the capabilities of agents advance, employees will move from executing tasks to supervising workflows, orchestrating agent collectives, and setting mission-level strategy. Preparing for this transformation has two requirements. First, a clear view of how roles evolve across the previously defined agent levels. Second, how responsibilities will shift among AI specialists, application users, and supporting teams.

Evolving Roles and System ArchitecturesAt the center of this transition are four archetypes.

The model developer creates AI models from scratch. Such models include large, medium, or small language models (xLMs), vision-language action models (VLAMs), and more traditional classifiers. This developer functions as a system architect at the model level.The model refiner adapts existing models using methods such as fine-tuning or RAG, acting as an adaptation-focused system architect.The agent developer creates agents that incorporate or call models while adding reasoning, planning, memory, and orchestration logic. This developer functions as the agent-focused architect.The application user interacts directly with agents or with business applications that embed them. The user performs tasks, validates outputs, and orchestrates multi-agent workflows.Other enterprise personnel, from data scientists and engineers to IT staff and business domain experts, also play critical roles. Their responsibilities evolve alongside these archetypes to ensure data quality, infrastructure reliability, governance, and business alignment. The table below summarizes how these roles transform across the six levels of AI agents.

AI Employment by Agent Level Agent Level Model Developer Model Refiner Agent Developer User Supporting Roles L1 Minimal involvement Minimal involvement Develops rules & adds them into simple agents Operator: Invokes agent, monitors outcomes Data engineers: maintain pipelines; IT: monitors uptime L2 Selects Foundation Models & builds LLMs Fine-tunes selected models to company needs Implements intent and manages dialog Guide: Guides agent behavior with prompts, validates outputs Data scientists: curate examples; business experts: provide prompts & guardrails L3 Develops proprietary xLMs and components to augment model context Tunes developed models for correct retrieval & dynamic context Implements memory heuristics & context management for models used Supervisor: Oversees multi-turn workflows, escalates edge cases Data engineers: maintain data pipelines for xLM development and dynamic context L4 Builds xLMs and xMMs specific to agent diversity Adjusts models to match agent capabilities Incorporates orchestration protocols into 1st & 3rd party agents, boosts observability Orchestrator: Coordinates multiple agents, sets objectives/ constraints IT: distributed heterogeneous systems MLOPs; Domain experts: define constraints L5 Designs safe self-learning pipelines & architectures Curates self-learning datasets, monitors agent model drift Implements reflective subsystems, & exploration policies Mission Architect: Defines goal and learning objective, oversees agent evolution IT: manage the continuous learning infrastructure, agent ops, unclog bottlenecks L6 Ensures dynamic updating of multiple diverse & proprietary xLMs, xMMs Oversees emergent behaviors, ensures ethics/ compliance Designs socio-technical ecosystems for collaboration of 1st and 3rd party L5 agents Mission Strategist: Sets mission, monitors agent performance, authorizes interventions IT: ensures systemic resilience and governance. Business units: ensure continuous strategic alignment .wpdt-ff-000002 { font-family: Palatino Linotype, Book Antiqua, Palatino, serif !important;}.wpdt-fs-000012 { font-size: 12px !important;}.wpdt-fs-000011 { font-size: 11px !important;}Three ObservationsFirst, as agents advance, the user evolves from application operator to mission strategist. This transformation profoundly reshapes business unit personnel. Simply knowing how to operate applications such as Workday or Salesforce — even as they are augmented with AI — will no longer be enough. Instead, business employees must be able to define missions for multi-agent systems, monitor performance, adjust objectives dynamically, and reconfigure the agent mix as conditions change. This role resembles that of a military strategist, setting goals, constraints, and tactics while leaving execution to the system.

Second, over time, the model developer’s role changes. This is the result of enterprises gaining experience with foundation models, but also as model performance plateaus. In some companies, developers will build proprietary small or medium language and multimodal models (xLMs, xMMs). In others, the developer’s responsibilities will converge with those of the refiner and the agent developer. Some AI-first enterprises may even merge these roles entirely. Regardless of structure, explicit accountability must be defined:

Who owns the models?Who owns the adaptation pipeline?Who is accountable for agent orchestration?Who authorizes the promotion of agents from testing to production?Third, with the introduction of Level 4 agents, enterprises begin deploying multi-agent systems that combine first- and third-party agents. These agents incorporate proprietary and third-party models of varying types and sizes. Agent developers, business users, and IT teams must manage behaviors and interactions among heterogeneous agents. As a result, governance becomes essential. Multi-agent systems, especially those mixing internal and external components, introduce new risks. These include misaligned objectives, emergent behaviors, supply-chain vulnerabilities, and reasoning opacity that complicates root cause analysis. Enterprises should establish an Agent Governance Framework. The framework addresses model health, fine-tuning quality, agent orchestration, and mission alignment. It includes deployment gates such as safe-fail modes, continuous observability and explainability, periodic red-team reviews of emergent behaviors, and escalation paths.

An ExampleImagine a large retailer piloting AI agent-based systems. With Level 2 agents, customer-service personnel guide conversational systems to resolve problems more quickly, while website search becomes easier and more effective through natural-language interaction. Inside the enterprise, software engineers use the same class of agents to boost their programming productivity. In the warehouse, semi-autonomous robots are supervised as they fulfill orders, shelve new arrivals, and re-stock returns. In the store, robots perform routine jobs such as cleaning, removing hazards, and providing security.

With Level 3 agents, customer support, software development, supply chain management, vendor disputes, and other business functions are handled largely autonomously, with only limited supervision. In the warehouse, robotic agents need little direction, though supervisors step in for multi-step cases where customer history or logistical constraints must be carefully considered.

At Level 4, software agents for logistics, fraud detection, and supplier communication coordinate with robotic agents that handle the physical movement of goods across warehouses. The Orchestrator user configures the agent set, defines objectives, such as minimizing return cycle time, and sets constraints on refund thresholds or supplier credits.

At Level 5, software agents analyze return patterns to refine fraud detection, while robotic agents adjust handling strategies based on wear-and-tear data. The user Architect defines reward signals, such as balancing customer satisfaction, cost control, and sustainability goals, and ensures safe learning loops. Supervisors and Orchestrators provide the evaluation data that feed these loops, while the Architect validates that learning improves mission outcomes without introducing bias or instability.

At Level 6, software and robotic agents operate as an emergent collective. They discover strategies that the enterprise did not pre-program. For example, the system may reassign warehouse robots to customer-service tasks during peak returns season or propose new supplier arrangements to reduce product defects. The Mission Strategist interprets these emergent behaviors, aligns them with corporate strategy, and decides whether to authorize systemic changes.

Business Leaders Action PlanMap current roles against the six-level spectrum and identify gaps in orchestration, governance, and learning pipelines.Assign clear ownership for model goals, adaptation protocols, and agent orchestration responsibilities.Launch pilots that progress from Level 2 to Level 4, with named Guides and Orchestrators for each stage and governance gates at every transition.Build a training curriculum for each archetype, including practical rotations such as orchestration shadowing, model-refinement labs, and safety playbooks.Instrument processes for end-to-end observability and governance.Create an Agent Governance Board with legal, security, business, and technical representatives, and define clear rules for third-party agent usage.ConclusionThis post does not attempt to predict a single, uniform future. Each AI-first enterprise will adopt a different mix of software and robotic agents, and will progress through the spectrum of agent levels at its own pace. Those choices will reflect differences in risk tolerance, domain complexity, and competitive context. What matters is that they are intentional, the result of deliberate planning rather than hasty reactions to competitive pressure.

As the table makes clear, the structural shifts in the workforce are unavoidable: application users evolve into mission designers, technical roles move steadily toward system architecture, and support functions advance from maintenance to governance. Enterprises that understand these shifts, prepare their people for orchestration and stewardship, and align governance accordingly will be positioned to turn agent capability into sustainable strategic advantage rather than operational surprise.

The post Preparing the AI-First Enterprise Workforce for the Age of Agents appeared first on Evangelos Simoudis.

September 1, 2025

Robotaxi Value Chains: From Prediction to Reality

The global robotaxi industry has entered a new era, one defined by the tangible formation of new value chains. The recent flurry of high-stakes partnerships and strategic pivots is not a sign of chaos, but rather the methodical construction of the very operational and economic structures required for autonomous mobility to scale. In Transportation Transformation, I predicted that the deployment of autonomous vehicles (AVs) would necessitate a radical departure from the traditional automotive value chains to a new, service-oriented paradigm: the Fleet-Based On-Demand Mobility Value Chain. I presented a framework for the transition. Today, that framework is becoming the industry’s working reality and a predictive lens through which to interpret what might otherwise appear to be a series of disparate corporate announcements.

The Blueprint EmergesThe global robotaxi industry has entered a new era, one defined by the tangible formation of new value chains. The recent flurry of high-stakes partnerships and strategic pivots is not a sign of chaos, but rather the methodical construction of the very operational and economic structures required for autonomous mobility to scale. In Transportation Transformation, I predicted that the deployment of autonomous vehicles (AVs) would necessitate a radical departure from the traditional automotive value chains to a new, service-oriented paradigm: the Fleet-Based On-Demand Mobility Value Chain. I presented a framework for the transition. Today, that framework is becoming the industry’s working reality and a predictive lens through which to interpret what might otherwise appear to be a series of disparate corporate announcements.

For years, the primary question was, “Can the AV technology work?” Now, as companies like Waymo, Uber, and Baidu deploy robotaxis at scale, the critical question has become, “How does the business model work?”. According to a JP Morgan report, Baidu’s Apollo Go service has already logged over 14 million driverless rides, comparable to Waymo’s in the US, and achieved positive unit economics in key markets. Meanwhile, competitors like WeRide and Pony.ai are aggressively reducing system and vehicle bill-of-materials (BOM) costs. These are economic milestones, signaling a transition from experimentation to the establishment of sustainable commercial operations.

The Models in Motion: How Today’s Leaders Validate the FrameworkThe current market is not converging on a single dominant business model. Instead, it is proving the viability of multiple, distinct strategic paths. A company’s legacy competencies dictate its choice of model. The strategies of today’s market leaders align directly with the three primary value chain implementation models I predicted and described in Transportation Transformation: the “Technology Company-Centric,” the “Mobility Service Provider-Centric,” and the “Automaker-Centric” models.

Robotaxi Models Predicted Model (2020) Example Company Strategic Execution (2025) Technology Company-Centric Waymo Develops core AV tech stack; aggregates demand and operates fleet in some markets, but also partners for • Vehicles (JLR, Hyundai, Zeekr)• Demand aggregation (Uber) • Specialized fleet operations (Avis) Mobility Services Provider-Centric Uber Evolves from asset-light model; aggregates demand and partners for • Vehicles (Lucid)• Tech stack (Nuro) Automaker-Centric Volkswagen (MOIA) Provides vehicle (ID. Buzz) and partners for • Tech stack (MobileEye)• Demand aggregation (Lyft) The Technology Company-Centric Model: Waymo’s Ecosystem PlayAfter a testing period during which it controlled major parts of the value chain, Waymo is starting to focus on its core competency (the AI-based AV stack) and outsource other critical value chain processes. This approach reflects strategic discipline. Waymo owns the core technology and is aggressively scaling its own fleets in cities like Phoenix, Los Angeles, and Austin, with over 2,000 commercial vehicles now operating in the US. The Uber partnership will greatly improve demand generation. The Avis partnership that will drive the Dallas expansion will provide end-to-end “fleet management services,” including vehicle readiness, maintenance, and depot operations. These moves directly map to the processes identified as essential but non-core functions for a technology-led company in my 2020 framework.

The Mobility Services Provider Evolution: Uber’s Strategic PivotUber’s recent actions, particularly its deal with Lucid and Nuro, represent a calculated departure from its historically “asset-light” model. In Transportation Transformation, I discussed such a pivot. The pivot highlights the pressure on ride coordinators to gain more control over the value chain to ensure service quality, diversify supply, and capture more value per trip.

It is also a strategic hedge against the “Waymo risk,” i.e., an over-reliance on a single powerful partner that could one day become a primary competitor. CEO Dara Khosrowshahi uses the company’s balance sheet to prove the revenue model of robotaxis as a distinct asset class. This strategy allows Uber to test multiple technologies and business models, from software licensing to direct vehicle ownership.

The Automaker-Centric Model: A High-Stakes GambleThis model remains the most capital-intensive and culturally challenging. My framework identified significant disadvantages, including the need for large investments in non-core competencies like AI software development and fleet management, and the immense challenge of corporate culture change.

The failure of General Motors’ Cruise robotaxi division validated these predicted risks. After billions in investment, GM shut down Cruise in late 2024. Nevertheless, Volkswagen’s MOIA division continues to pursue this strategy, but this time in partnership with MobileEye and Uber.

The Rise of the Fleet Operations EcosystemA sophisticated ecosystem dedicated to the operation of autonomous fleets is emerging. The “Fleet Management,” “Fleet Maintenance,” and “Vehicle Financing” processes outlined in the framework are becoming high-value industries. The Waymo-Avis and Lyft-Marubeni partnerships are prime examples of a new “Fleet Operations as a Service” model. This new service layer will expand to include specialized providers for insurance, data management, and robotic depot maintenance, creating a ripple effect of economic opportunity.

The focus on operations is seen clearly in Chinese robotaxi companies. Baidu is already achieving positive unit economics, WeRide cutting system costs by fifty percent, and Pony.ai reducing its vehicle BOM by seventy percent. The primary bottleneck for scaling is now shifting from technological readiness to capital availability. Today, a single Waymo vehicle costs approximately $175,000; a fleet of 10,000 would require a capital outlay of $1.75 billion. Financial innovation has become as critical as technological innovation.

From Deployment to Integration and OrchestrationWith foundational value chains now being built and validated, the next competitive frontier lies in globalizing them. U.S. firms are testing internationally, e.g., Waymo in Tokyo, while Chinese companies are aggressively forming partnerships to enter new regions: WeRide with Grab in Southeast Asia, Baidu with Lyft in Europe, and Pony.ai establishing a presence in the EU and the Middle East. These international partnerships are essential for acquiring localized operational knowledge. Success requires deep integration with local regulations, infrastructure, and user behavior; best achieved by partnering with an entrenched local player.

This trend points toward the vision presented in Transportation Transformation: the “Multimodal MaaS Value Chain”. In this end-state, robotaxis are not a standalone solution but one integrated component within a digitally orchestrated network that includes private mobility, public transit, micromobility, and other transport options. The “city government” is a core actor and evolving from a mere regulator to a “transportation orchestrator,” actively shaping how these new services are integrated into the urban fabric.

ConclusionThe evolution of autonomous shared mobility is proceeding along the logical, structured pathways predicted years ago. The industry has moved past the initial hype cycle of pure technology and is now engaged in the difficult but essential work of building sustainable, scalable business models founded on new and complex value chains. The framework is clear, and the race to execute it is on. The challenge is no longer if these models will work, but how quickly they can be refined, financed, and scaled. The companies that master the full, integrated value chain, from silicon and software to fleet operations, financial engineering, and regulatory strategy, will define the next decade of urban mobility.

The post Robotaxi Value Chains: From Prediction to Reality appeared first on Evangelos Simoudis.

August 12, 2025

A Guide to AI Agent Design Patterns

In the first three parts of this series, we achieved three objectives. We described the characteristics of the AI-first company. We identified the role of AI agents in such a company. Finally, we created and refined a six-level spectrum to map the range of AI agents, from simple software automation to embodied, collaborative systems. The challenge for the AI systems architect is how to design these agents in a disciplined, scalable, and reliable manner.

Introduction: From Mapping the Territory to Building the RoadsAgents as an AI construct are not new. They have been used in intelligent systems for several decades. Despite the recent emergence of powerful development frameworks, building agents remains an artisanal craft, more recently driven by intricate prompt engineering. The crafted agents are inherently brittle and rarely scale to meet the demands of the AI-first company.

To address brittleness and scale, we need to close the gap between craft and repeatable engineering practices. We must create a set of standardized AI Agent Design Patterns that link the conceptual levels of the agent spectrum to practical, reusable implementations. This article presents a catalog of such patterns.

The article’s unique value is in:

Providing decision-support guidance for pattern selection.Highlighting anti-patterns and common pitfalls.Showing the evolution pathways between patterns as agents increase in capability along our spectrum.The AI System Architect’s View: Adding the Design DimensionThe previous articles focused on two personas found in the AI-first company: the AI strategist and the AI system’s user. We now need to focus on the AI system architect whose responsibility is to design the agent-based system. To get everyone on the same page, let’s start by defining what we mean by “AI Agent Design Pattern.”

An AI Agent Design Pattern is a reusable, abstracted solution to designing, organizing, coordinating, or deploying agents that perform tasks within a system. It does not focus on specific implementations (e.g., which LLM or API to use), but on how agents are structured, interact, make decisions, and evolve across various contexts.

An AI Agent Design Pattern is defined by the following dimensions:

AI Agent Design Pattern Dimension Agent Role Autonomy Level See Agent Spectrum Intent What the agent does (e.g., execute a task, coordinate others) Interaction Model How the agent interacts with the world Control Architecture Centralized vs decentralized control State Management How the agent maintains, updates, and shares context Task Decomposition How the agent breaks down tasks (relates to autonomy level) Embodiment Software only or is physically embodied .wpdt-ff-000002 { font-family: Palatino Linotype, Book Antiqua, Palatino, serif !important;}.wpdt-fs-000014 { font-size: 14px !important;}For every AI agent level and associated user role, the AI system architect must address certain challenges. As the table below shows, design patterns address each of these challenges.

Agent Design Pattern Examples Agent Level User's Role Agent Capability AI System Architect Challenge Design Patterns 1 Operator Basic Automation Implementing deterministic logic: Creating rigid, predefined workflows and state transitions. • State Machine• Rule Engine• Sequential Executor 2 Guide Conversational Assistant Managing intent and dialogue: Parsing input, managing conversation state, and executing simple tools. • ReAct (Reason+Act) • Function Calling • Intent-Slot Filling 3 Supervisor Contextual Adaptive Architecting dynamic memory: Designing systems for storing and retrieving relevant context to alter behavior. • Memory Vectorization • Contextual Knowledge Graph • Dynamic Scaffolding 4 Orchestrator Coordinated Multi-Agent Defining roles & communication: Designing protocols and roles for multiple agents to collaborate on a task. • Hierarchical Model• Multi-Agent Debate• Publish & Subscribe 5 Architect Autonomous Learning Building self-improvement loops: Creating mechanisms for the agent to evaluate its own performance and modify its strategy. • Reflective Critic• Generative Feedback Loop• Explore/Exploit 6 Mission Strategist Emergent Collaborative Guiding collective intelligence: Setting ethical guardrails and high-level objectives for a system that learns its own collaborative strategies. • Constitutional AI• Swarm Intelligence• Dynamic Role Allocation .wpdt-ff-000002 { font-family: Palatino Linotype, Book Antiqua, Palatino, serif !important;}.wpdt-fs-000014 { font-size: 14px !important;}How to Use the Pattern CatalogAs the performance of foundation models begins to plateau, given the constraints of publicly available data, the performance of AI agents used in the enterprise will increasingly depend on the enterprise’s proprietary data, proprietary workflows, and domain-specific feedback loops. This shift has implications for design patterns: AI agents must be customized around the specific environments, interaction models, and governance constraints of each enterprise.

The Architect’s Challenge: From Generic Models to Enterprise-Specific AgentsThe literature on agent design patterns is already substantial, including for patterns tied to LLMs or multi-agent systems. Generic agent design knowledge is valuable. However, the AI architect’s primary challenge is to select and adapt design patterns to:

Integrate proprietary data securely and effectively.Embed within domain-specific workflows.Balance autonomy with the oversight models of the enterprise.This framing enables the AI architect to move beyond static pattern knowledge toward dynamic pattern orchestration, choosing the right approach for the current agent level while planning for future evolution.

Four Classes of AI Agent Design PatternsWe organized design patterns into four classes:

Foundational patterns (used for building reasoning agents and addressing situational adaptation).Organizational patterns (used for building various types of collaborating agents).Evolutionary patterns (used for building learning agents).Interface and Embodiment patterns (used for designing agents that interact physically with the world).Deconstructing a Pattern: A Practical ExampleBefore diving into the catalog, provided as an Appendix, it is important to see how the dimensions introduced in Section 2 map onto a real pattern. The example below uses the “Hierarchical Model” pattern from Level 4, Orchestrator, where the agent’s role is to delegate tasks to lower-level agents and coordinate workflows.

DimensionAgent Role

Autonomy LevelHigh in task execution, medium in goal settingIntentBreak complex problems into manageable subtasksInteraction ModelStructured inter-agent communicationControl ArchitectureHierarchical; top-level agent coordinates specialized agentsState ManagementShared state or blackboard for subtask progressTask DecompositionMulti-level, from broad objectives to atomic actionsEmbodimentSoftware-only or hybridThis example demonstrates how the dimensions provide a complete architectural profile of the pattern. The same approach is used in the Appendix to define each pattern in decision-support terms.

ConclusionAI agent design patterns are building blocks for enterprise capability growth. As AI-first enterprises expand their AI efforts from prompting foundation models toward developing proprietary agent-driven workflows, AI agent design patterns become the critical link between the conceptual levels of our agent spectrum to practical, reusable implementations of scalable, robust agents. Our decision-support framework offers the AI system architect a tool for navigating design trade-offs today while anticipating tomorrow’s enterprise demands.

Appendix: AI Agent Design Patterns with Selection Heuristics, Pitfalls, and Evolution PathsFoundational Patterns (Reasoning agents and situational adaptation)Agent LevelPattern NameWhen to UseCommon PitfallsNext Step in Evolution1State MachineTasks are deterministic, fully understood, and require predictable transitions (e.g., kiosk interfaces, process automation).Hardcoding too many states, making the system brittle; using it for environments that require adaptation or handling unseen inputs.Add contextual triggers or event-driven logic to transition toward an Interactive Agent.Rule EngineDecision-making can be captured as explicit if–then–else rules; easy for domain experts to modify.Rule explosion in complex domains: rules that conflict or lack a resolution mechanism.Introduce probabilistic or learning-based decision modules to move toward a Contextual Adaptive Agent.Sequential ExecutorLinear workflows that must execute in a fixed order without deviation (e.g., data ETL pipelines).Fragility when tasks fail mid-sequence; no provision for reordering or skipping steps.Wrap sequence steps in a planning module for flexibility and error handling.2ReActTasks require both reasoning & tool use, with transparency in intermediate steps.Over-reliance on LLM reasoning for domains requiring deterministic precision; verbosity in reasoning traces.Augment with persistent memory to transition into a Contextual Adaptive Agent.Function CallingAgent must integrate with external APIs/tools to perform actions based on user intent.Poor schema design for function inputs; too many functions causing intent confusion.Introduce intent recognition and context management for adaptive decision-making.Slot FillingStructured tasks where user intent maps to a fixed set of parameters (slots) before execution.Rigid slot definitions that fail when user requests don’t match; lack of disambiguation strategies.Expand to multi-intent handling and contextual slot adaptation.3Memory VectorizationThe agent must recall past events, conversations, or facts to influence current behavior.Storing irrelevant or low-quality context; vector search that returns noisy matches.Add semantic filtering and reasoning over memory for deeper adaptation.Contextual Knowledge GraphTasks require a structured, relational context for reasoning (e.g., linking entities, events, relationships).Out-of-date graph data; over-complication with unnecessary relationships.Pair with a planning module to drive multi-step reasoning.Dynamic ScaffoldingAgent dynamically creates or modifies its subroutines or reasoning paths.Poor constraint management leading to runaway complexity; unpredictable performance.Integrate scaffolding with coordinated multi-agent orchestration.Organizational Patterns (Collaboration between agents)Agent LevelPattern NameWhen to UseCommon PitfallsNext Step in Evolution4Hierarchical ModelClear task decomposition exists; tasks can be delegated to specialized agents.Single point of failure in top-level orchestrator; communication bottlenecks.Introduce decentralized role negotiation for autonomy.Multi-Agent DebateProblems require weighing multiple perspectives or expertise areasEndless debate loops without convergence; lack of scoring/ranking criteriaAdd consensus or voting mechanisms for faster decision resolutionPub/SubMultiple agents must react to shared events without tight couplingEvent overload causing performance issues; poorly defined event schemasLayer in priority or relevance filters to handle complex environments

Evolutionary Patterns (Learning and adaptation)Agent LevelPattern NameWhen to UseCommon PitfallsNext Step in Evolution5Reflective CriticTasks benefit from iterative self-evaluation and output refinement.Excessive self-critique loops; no grounding in objective performance metrics.Combine with multi-agent peer review to evolve toward collaborative systems.Generative Feedback LoopContinuous learning from both successes and failures is needed.Learning from biased or poor-quality feedback, drift from intended goals.Incorporate feedback from other agents to improve collaborative performance.Explore/ExploitAgent balances new strategies with exploiting known good onesOver-exploration wastes resources; over-exploitation misses innovation opportunitiesTransition to multi-agent learning where agents share discoveries.6Constitutional AIAI must align actions with predefined ethical or operational principles.Overly vague or conflicting constitutional rules; no enforcement mechanism.Embed constitutional constraints directly into emergent collaborative systems.Swarm IntelligenceLarge-scale coordination with no central controller; robustness through redundancy.Emergent behaviors misaligned with objectives; inability to debug.Add dynamic role allocation for adaptive swarm composition.Dynamic Role AllocationAgents in a collective must shift roles based on real-time needs.Excessive churn in roles causes instability; unclear role definition.Integrate with swarm frameworks to combine adaptability with robustness.

Interface & Embodiment Patterns (Physical interaction, sensors, and actuation)Agent LevelPattern NameWhen to UseCommon PitfallsNext Step in Evolution1-3Subsumption ArchitectureEmbodied agents in dynamic, unpredictable environmentsRigid priority layers causing conflicts; difficulty adding new layersAdd contextual decision-making above reactive layers2-5Event-Driven AutonomyEnergy/resource-constrained agents that act only on relevant triggers.Missed events due to poor sensor coverage; event storms overloading the agent.Combine with predictive models for proactive behavior.3-6Digital Twin SynchronizationEmbodied agents requiring simulation-based planning or remote monitoring.Desynchronization between twin and physical system; computational cost of updates.

The post A Guide to AI Agent Design Patterns appeared first on Evangelos Simoudis.

August 5, 2025

Evolving the AI Agent Spectrum: From Software to Embodied AI

In the piece Agents in the AI-First Company I introduced a five-level spectrum for understanding software agents. The piece generated a strong response and valuable comments, for both of which I’m incredibly grateful.

Some readers questioned the original progression of the spectrum. They noted that developing agents that can collaborate based on pre-programmed rules is a distinct, and often simpler, challenge compared to creating a single agent that can truly learn and evolve on its own. Their argument was persuasive: we will likely develop and deploy systems of self-coordinating agents before mastering truly autonomous learning agents.

This insight doesn’t just swap two levels; it highlights the need for a more nuanced framework. Based on these discussions, I’ve added an extra level to the original spectrum to represent the real-world development of AI capabilities better.

An Updated 6-Level Agent SpectrumThe refined spectrum now distinguishes between systems of coordinating agents (Level 4) and single autonomous learning agents (Level 5), and assigns collaborating learning agents to a new Level 6, thereby creating a more logical and robust progression.

Level 1: Basic Automation. The agent follows predefined, deterministic rules to perform repetitive tasks. It does not learn from its environment or adapt its behavior.Example: A UiPath Robot executing a pre-defined workflow to process invoices.Level 2: Interactive Agent. The agent can understand input and generate relevant output for a single session. It lacks persistent memory and the ability to learn independently.Example: A basic FAQ chatbot on a website that responds to specific keywords without remembering the conversation.Level 3: Contextual Adaptive Agent. The agent maintains memory during a task and adjusts its actions in real-time. Its adaptation is situational and does not create general knowledge.Example: A chatbot like Gemini or ChatGPT that uses the history of the current conversation to provide a coherent, multi-turn dialogue.Level 4: Coordinated Multi-Agent System. A system of multiple Level 3 agents that work together based on pre-programmed, human-designed rules and communication protocols.Example: A Zapier- or MCP-based workflow where a new email in Gmail triggers agents to save an attachment to Dropbox and send a notification to Slack.Level 5: Autonomous Learning Agent. The agent learns from its actions by abstracting general principles from its experiences, allowing it to act effectively in novel situations and evolve its strategy over time.Example: DeepMind’s AlphaGo, which learned to play Go at a superhuman level by developing novel strategies through self-play.Level 6: Emergent Collaborative System. A system of multiple Level 5 agents that learn how to collaborate. The system’s collective strategy emerges from the agents’ interactions and shared learning.Example: Google DeepMind’s Composable Reasoning research, where multiple LLM agents learn to decompose complex problems and form dynamic teams to solve them.From Software to the Physical World: The Embodied AI SpectrumEmbodied AI refers to intelligent agents that possess a physical body. This allows them to perceive, reason about, and interact directly with the physical world. Unlike purely software-based AI agents, the intelligence of these agents is shaped by their physical experiences and sensory feedback. The agent spectrum extends naturally beyond software to the world of robotics.

Level 1: Basic Robotic Automation. Executes a fixed, pre-programmed set of physical movements without sensory input.Example: A CNC machine cutting a piece of metal.Level 2: Sensory-Responsive Robot. Modifies its routine based on simple, direct sensory input according to fixed rules.Example: An intelligent traffic light that adjusts its timing based on real-time data from sensors placed at an intersection.Level 3: Contextual Adaptive Robot. Utilizes its sensors and a user-defined geofence to construct a model of its environment, enabling it to operate autonomously and complete a specific task.Example: A robotic vacuum cleaner operating in a house, or a hospital robot delivering medicine to different departments.Level 4: Coordinated Robotic System. A system of multiple Level 3 robots working together based on human-designed coordination rules.Example: A warehouse robot fleet following centrally managed traffic rules.Level 5: Autonomous Learning Robot. A single robot that learns from its physical interactions by abstracting general principles (e.g., about physics, navigation) to handle novel situations.Example: A Waymo autonomous vehicle, whose driving model is continuously improved based on the collective experience of the entire fleet.Level 6: Emergent Collaborative Robotic System. A system of multiple Level 5 learning robots that learn to coordinate their physical actions and strategies collectively as a result of their shared experience.Example: A search-and-rescue drone swarm that learns the most effective patterns to accomplish relevant goals as a group.The updated agent spectrum is shown below

A critical distinction defines the jump from the lower levels to the higher ones. Agents at Level 3 are masters of situational adaptation. They can “copy” the context of a specific task, e.g., a robotic vacuum cleaner mapping a room, but they don’t learn from each such experience. If the context isn’t a near-exact match in the future, the experience is of little use.

The revolutionary leap at Level 5 is the ability to abstract over context. While the ultimate goal is for agents to learn and generalize underlying principles through methods like deep reinforcement learning, the path to this level of autonomy is not all or nothing. We are likely to see significant near-term progress from agents that become exceptionally skilled at drawing from vast contextual histories to handle new situations, especially rare edge cases. This sophisticated form of pattern matching is a critical stepping stone, but the true paradigm shift remains the move from finding near-matches to developing genuine, abstract understanding.

A Note on Learning Architectures: Homogeneous vs. Personalized ModelsThe discussion of learning agents (Levels 5 and 6) brings up a critical design choice: how is the learning managed across many users or units? The answer depends entirely on the use case.

Homogeneous Fleets: For systems like Waymo’s autonomous vehicles or a factory’s fleet of autonomous robots, consistency and predictability are paramount. Here, every agent runs the same, centrally updated model. The agent’s capability is defined by the entire system, the vehicle collecting experiences, and the data center that processes those experiences to improve the models used by the fleet. The goal is to create a single, highly optimized “brain” that is deployed in increasingly complex environments, ensuring every unit behaves identically and benefits from the collective learning of the entire fleet.Personalized Ecosystems: In other scenarios, such as a personal software assistant, uniformity is undesirable. Each user has a unique context, private data, and specific needs. Here, each agent must be trained or fine-tuned differently. This introduces privacy and data containerization challenges, which are being solved by advanced methods like Federated Learning. This technique allows a global model to learn from the collective experience of all users without ever accessing their private data, enabling both personalization and shared intelligence.This distinction between uniform and personalized learning architectures is a crucial factor in the real-world deployment of advanced agents.

The Next Dimension: Human-Agent TeamingSo far, our framework has focused on the capabilities of agents and their relationship with a single human user. However, the future of work involves the increasing collaboration between humans and AI agents. This prospect raises a crucial question: What happens when teams of humans collaborate with agents to achieve a shared goal? This introduces a new dimension of complexity.

Shared Agent (One-to-Many): In this model, a single agent instance serves an entire team. The agent must not only understand the task but also the team’s social dynamics, manage shared context, and potentially mediate conflicting human inputs. This requires a high degree of contextual awareness, likely demanding Level 5 capabilities.Individual Agents (Many-to-Many): Each team member has their own agent. This leads to two distinct and powerful sub-cases:Homogeneous Teaming: Every team member uses the same type of agent (e.g., everyone has a “writing agent”). This creates an immediate need for the agents to coordinate, driving the development of Level 4 (programmed) and Level 6 (learned) collaboration.Heterogeneous Teaming: Team members use different, specialized agents (e.g., a writer with a “writing agent,” an editor with an “editing agent,” and a researcher with a “fact-checking agent”). This represents a true division of labor among the agents themselves, requiring them to be aware of each other’s roles and seamlessly hand off tasks. This is the ultimate vision for a Level 6 emergent collaborative system, creating a dynamic, self-optimizing digital assembly line.Understanding these teaming architectures is critical. The future of productivity will be defined not just by the power of individual agents, but by how they are woven into the fabric of human collaboration. The development of standardized communication protocols, such as Google’s Agent-to-Agent (A2A) protocol or Anthropic’s Model Context Protocol (MCP), will be a critical accelerator for creating these robust, heterogeneous agent teams at scale.

A New Path to Advanced Embodied AI: The Rise of Foundation ModelsRecent breakthroughs from Google, the Toyota Research Institute, and others demonstrate a revolutionary new method for creating advanced physical agents. This approach uses foundation models as the “brain” for a robot.

This development does not change the agent spectrum. Instead, it provides a powerful new pathway to achieving Level 5 capabilities. By pre-loading a robot with a foundation model, we give it a “common sense” understanding of the world. It doesn’t need to learn what an “apple” is from scratch; it inherits that abstract knowledge. As a result, the robot’s training can focus on connecting this vast knowledge to physical actions. This method is a massive accelerator for creating Level 5 agents that can generalize and act effectively in novel situations, perfectly aligning with the core definition of that level.

The post Evolving the AI Agent Spectrum: From Software to Embodied AI appeared first on Evangelos Simoudis.

July 8, 2025

Agents In the AI-First Company

AI agents are an important component of the transformation to become an AI-first company. Corporations undertaking this transformation must understand where and how to incorporate agents and which agent types to utilize in the AI-centric processes they establish and the organizational structures they adopt. The article presents AI agent types, outlines how corporations should think about “agentification” as they transform to become AI-first, and explains how our firm’s AI methodology fits agents into AI-first business processes.

IntroductionThe AI agent concept isn’t new. Research on AI agents began decades ago. As a young researcher at Digital Equipment Corporation’s R&D labs, I worked on intelligent agents and frameworks that enable different types of agents to collaborate during problem solving. The rise of generative AI gives us new ways to think about agents. Today, we use the term “agent” broadly to describe everything from simple chatbots to partly autonomous copilots. This lack of precision risks diluting what truly makes agents revolutionary in an AI-first company.

In a piece I wrote in August 2023, I provided my definition of an intelligent agent. Broadly, I explained that to be classified as an agent, a system must be able to receive input about a goal to be achieved, reason and develop a plan to address this goal using its understanding of the environment in which it operates and the knowledge it has access to, execute the plan, evaluate the results of its actions, and learn from the experience.

The Agency SpectrumMy definition outlines an ideal AI agent. Currently, few agents display this complete set of capabilities. However, even with fewer capabilities, agents remain a crucial part of the processes employed by AI-first enterprises. Moreover, they can also play vital roles in AI-enhanced processes utilized by other enterprises. Consequently, I view agency as a five-level spectrum.

Level 1: Basic Automation. A deterministic system that uses a set of predefined rules and instructions to execute specific, repetitive tasks without any deviation or learning. These cannot reason or adapt to changes in their environment. Example: Robotic Process Automation (RPA) scripts.Level 2: Conversational or Generative Assistant. An assistant agent accepts input, generates contextually relevant output, and can adapt flow within a single session, but lacks persistent memory or autonomous learning. Examples: LLM-based chatbots and various copilot types, e.g., e-commerce agents, and OpenAI’s Operator.Level 3: Contextual Adaptive Agent. Adaptive agents maintain local memory during tasks, reason about changing context, plan, and update actions in real time. These agents adapt to changing conditions. However, they confine their learning to the task at hand. Examples: A Waymo autonomous vehicle and Amazon’s AI-based robotic fleet management.Level 4: Autonomous Learning Agent. This agent adapts its plan in real time, learns from each executed plan, and incorporates that experience into future actions. Learning is persistent and allows the agent to evolve its strategies over time without direct human intervention. Examples: DeepMind’s AlphaGo and its successors (AlphaZero, MuZero) demonstrate how agents can improve policies through self-play and reinforcement learning. However, such systems remain experimental, bound to constrained domains and training contexts.Level 5: Collaborative Multi-Agent System. The system comprises multiple Level 4 agents that operate in a shared environment to achieve common or competing goals. Such a system exhibits collective intelligence. Agents can dynamically form teams, negotiate with one another, and resolve conflicts to optimize for a shared objective. Examples: Research labs are developing drone swarms to autonomously coordinate their actions for tasks like search and rescue. This is at the frontier of AI research.As we move from Level 1 to Level 5, human involvement transitions from full control to no control. Level 2 agents have a collaborative relationship with humans. Generative AI provides Level 2 AI agents with capabilities in natural language generation, knowledge synthesis, and certain types of reasoning. It expands their ability to communicate with humans and, potentially, with other agents. Level 3 agents utilize new post-training approaches and neurosymbolic computing extensively. With these agents, the human’s role is that of the governor and orchestrator. The human knows which agent to invoke for each task and in what sequence to invoke them. But once invoked, the Level 3 agent completes the entire task.

Deciding to Develop an Agent and Selecting Its LevelThe AI-first company formulates corporate strategy, business processes, and organizational structures around AI. As it relates to AI agents, corporations must make three deliberate design choices during their AI-first transformation:

Agentifying a task, or an entire process;Determining whether to develop the agent, or agents, or license third-party ones;Selecting the agent’s level.The corporation must make these choices through an agentification strategy. Developing an agent without having an overall strategy often leads to failure.

An agent should encapsulate a task, or an entire process, when autonomous decision-making is possible, or when the task’s completion at least requires input from a dynamically changing environment coupled with human oversight. For example, consider the task “Monitor issued purchase orders and work logs to validate what payments are due,” which is part of the AI-first vendor payment process I introduced in a previous piece. Furthermore, assume that the process is used by a construction company to pay its vendors. This is a task that can be performed autonomously and, therefore, can be agentified using a Level 3 agent. In this case, the human operator acts as a governor and orchestrator of the agents that are part of the business process.

Next, suppose that the same process is used by a retailer. The decision on whether to pay the vendor and how much may also depend not only on the number of items delivered by the vendor but also on how many of these items were returned by the retailer’s customers. As the number of returns changes dynamically, an agent can be retrieving return data and a human interpreting whether the data warrants full, partial, or no payment to be issued to the vendor. This implies that the task can still be agentified by a Level 2 agent. In this case, the human operator acts as a collaborator of the agents that are part of the business process.

Creating an Agent EcosystemAgentification does not stop at the enterprise boundary. Once an AI-first corporation deploys robust agents in critical workflows, it will increasingly require its key vendors, partners, or customers to expose agents that comply with shared protocols. This implies defining:

Minimum capabilities each external agent must have,Secure communication protocols for agent-to-agent negotiation,Governance procedures for onboarding, escalation, and exception handling.This ecosystem approach ensures that agent-to-agent interactions across organizational boundaries remain secure, auditable, and aligned with the corporation’s governance framework.

ConclusionEnterprises are actively experimenting with a variety of internally developed and third-party AI agents. Agents already deployed in production, from a Waymo vehicle to OpenAI’s Operator, show how far we have come, but also how far we still have to go. For the corporation, agentification is not a one-time decision; it is a maturity journey.

Using our methodology, we recommend that companies undertake the transition to become AI-first:

Start with AI-first processes that embed the right level of reasoning and autonomy for their current environment.Design modular architectures that enable the right levels of orchestration and governance, allowing agents to evolve.Create clear pathways for processes to progress from static automation to adaptive, learning, collaborative systems.By defining a clear transformation plan and timeline, AI-first companies lay the groundwork for the adaptive, learning agents that will power tomorrow’s distributed, intelligent enterprise, creating a competitive edge that is increasingly difficult to replicate.

The post Agents In the AI-First Company appeared first on Evangelos Simoudis.

June 30, 2025

The AI-First Company

In today’s corporate digital transformation landscape, “AI-first company” is emerging as a term that deserves real attention, not just another consultant’s buzzword. But can an incumbent truly transform to become AI-first, as Intuit is attempting, or must it be designed that way from inception, like Tesla? In my previous article, I defined the AI-first business process and contrasted it with AI-enhanced processes. This piece builds on that foundation to define what an AI-first company is, describe its defining characteristics, and provide examples of corporations undergoing this transformation.

AI-first is a company that centers its operations around AI, as opposed to a company that only occasionally incorporates AI into its operations. The decision-making, business processes, and team structures of the AI-first company are all driven by AI. Its employees work as AI agent orchestrators and feedback providers, and its systems adapt in real time. In AI-first companies, AI influences product development, enhances customer experiences, and impacts the overall business model. These companies are built from the ground up or undergo a complete transformation to become AI-first.

We expect AI-first companies to improve all their operational metrics. Their teams are smaller, and value is measured by how quickly insights from continuously analyzed data are turned into action.

Example AI-First CompaniesWe see this transformation not just among high-tech companies like Google, NVIDIA, or OpenAI, where technology is the product itself, but also among what we call tech-forward companies. These incumbents use technology as a differentiator, aggressively investing, building, acquiring, and adopting cutting-edge capabilities to reimagine their core businesses, which are in a non-tech sector (finance, retail, logistics, consumer goods, manufacturing, healthcare, etc.).

We have identified several tech-forward companies (Table 1 provides a sample) that are transforming to become AI-first. These companies are rethinking their processes, culture, and customer experience. They have moved beyond AI pilots and now deploy production AI systems, are retraining their staff, redefining governance, and viewing AI as a strategic asset rather than just an outsourced feature. This shows us that real AI success demands integrating culture, people, and business processes, not just technology and data.

Company

AI-first Transformations

Intuit

Reimagined core processes (e.g., TurboTax and QuickBooks), uses generative AI in customer and advisor interactions, a continuous experimentation mindset, internally developed AI platform.Tesla

AI-first products, manufacturing processes, and customer experiences.Visa

AI-first approach in every business line and business processes, including fraud detection, payment authorization, and real-time analytics.JPMorgan Chase

AI-first transformation of business processes, including risk, compliance, and trading. Generative AI-based new customer experience for wealth management.Morgan Stanley

AI-first transformation of its advisory and wealth management business lines.Walmart

AI-first transformation of its business processes, including supply chain management, pricing, and inventory management. Use of generative AI in customer experiences. Integrated copilots into employee workflows.GE HealthCare

AI-first transformation of clinical imaging, diagnostics, and device operation. Reinvention of both products and services.Schneider Electric

AI-first transformation in product design and internal operations (e.g., demand forecasting).Siemens

AI-first transformation of its cyber-physical systems business.Procter & Gamble

AI-first transformation of the product R&D, manufacturing, and marketing business processes. Internally developed AI platform.American Express

AI-first approach in business processes, including fraud detection, customer experience, and credit underwriting.Table 1: A small sample of AI-first companies

AI-First Company CharacteristicsAs mentioned in the previous article, we developed a methodology through which companies transform to become AI-first. Our methodology is based on the characteristics that define an AI-first company:

Culture and strategyPeopleBusiness processTechnologyData and knowledgeTable 2 maps these characteristics to real companies, showing how each one exemplifies different aspects of the AI-first transformation.

AI-First Company Characteristic

Companies Exhibiting It

Establish culture and strategies around continuous experimentation and customer centricity that drive ongoing learning, and value exchange between the company and its customers. (Category 1)Intuit, Tesla, ServiceNow, JP Morgan, Morgan StanleyDefine the problems worth solving, engage employees and AI to solve them, and iterate rapidly while promoting agility and adaptability (Category 1)Intuit, Tesla, ServiceNowBreak organizational silos and establish inter-departmental partnerships so that they can quickly turn into action insights from continuously analyzed data torrents. (Category 2)Intuit, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, GE HealthCare, Schneider Electric, Siemens, WalmartNew and existing employees embrace AI. They contribute to and create AI innovations. (Category 2)Intuit, ServiceNow, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, Walmart, Siemens, Schneider ElectricRedesign processes from the ground up with AI at their core and feedback loops that can support iterative refinement (Category 3)Intuit, Tesla, ServiceNow, Morgan Stanley, SiemensDefine, implement, and monitor metrics to assess the effectiveness of each AI-first business process. (Category 3)Intuit, ServiceNow, JPMorgan ChaseSpend years experimenting with AI technologies and view data and AI models as key corporate IP. (Category 4)Tesla, JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley, Intuit, Siemens, ServiceNowCenter the system architectures around AI models, enabling composability, retraining, and real-time inference. (Category 4)Intuit, Tesla, ServiceNowEstablish ethics guardrails and develop tools and policies to detect, explain, and mitigate AI-generated inaccuracies and protect data privacy. (Category 4)Intuit, ServiceNow, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, GE HealthCare, Siemens, Visa, American ExpressDevelop or adopt systems that integrate structured and unstructured data, making them available to AI models.Intuit, Tesla, ServiceNow, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, Walmart, SiemensIntegrate AI model development, deployment, monitoring, and governance. (Category 4)Intuit, Tesla, ServiceNow, JPMorgan ChaseTreat data as a strategic asset essential to competitive differentiation and invest in scalable and real-time data infrastructure. (Category 5)Intuit, Tesla, ServiceNow, Visa, American Express, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, Walmart, SiemensTable 2: The characteristics of AI-first companies

In my book The Flagship Experience, I provide a blueprint of how automakers and their Tier 1 suppliers can use the transition to software-defined new energy vehicles to transform into AI-first companies and provide a new end-to-end customer experience. I describe the culture and people changes that will need to be adopted and how business processes will need to be redesigned. Incumbent automakers have embraced AI as an adjunct to their existing processes, rather than placing it at the core of redesigned processes. As a result, data and AI models, and by extension, software, are still not treated as key IP assets.

ConclusionBecoming AI-first is no longer optional for companies that want to maintain a competitive edge in the age of discriminative and generative AI and continuous digital reinvention. The AI-first transformation requires reimagining not just processes and technology stacks but also culture, talent models, and governance frameworks. The companies that undertake this transformation will define their plan and timeline to execute it. The examples shared here prove that even large incumbents can reinvent themselves if they treat data and AI as strategic assets and fully integrate them into every facet of their business.

The post The AI-First Company appeared first on Evangelos Simoudis.

June 24, 2025

Deciding Between AI-Enhanced and AI-First Business Processes

The business world is buzzing with AI experimentation. However, a structured approach for moving from experimentation to production, although necessary, is often lacking, which hinders AI’s transformative potential. This article introduces a decision-support framework, implemented as a decision tree, to help executives mitigate the risks associated with decisions relating to moving AI experiments to production, focusing on AI-enhanced vs AI-first business processes.

Introduction: The Need for a Structured AI StrategyThis is a pivotal year for AI in the enterprise. The pace of technology advances remains blistering. Cross-industry surveys (here and here) show that enterprises are experimenting with AI at an unprecedented level. The outcome of these experiments will determine whether AI finally becomes the transformative force envisioned since the 1950s, or remains a much-promising technology.

AI experimentation in the enterprise is often driven by technology groups that are testing the technology’s feasibility to address a stated problem. It lacks the decision-making rigor required for enterprise transformation. Based on our years of experience applying AI to address enterprise challenges, we recommend that business units exploring AI’s potential in their operations undertake five actions:

Set the innovation horizon. Ensure this period is sufficient for experimentation, solution development, deployment, and evaluation of outcomes.Align the AI strategy. Ensure the business unit’s AI strategy is consistent with the innovation horizon and the overall corporate AI strategy.Avoid common pitfalls. Resist the urge to start too many experiments or to experiment for too long before deciding how to proceed.Select and categorize processes. Choose the business processes for experimentation and determine whether to enhance them with AI or redesign them as AI-first.Lead a collaborative effort. Form a close partnership with HR and IT organizations, but lead the overall AI effort. The collaboration of these three groups enables AI adoption in ways that no single function can accomplish alone.We translated our experience that AI requires experimentation before scaling into a framework to help decision-makers in a structured manner, and de-risk these actions. In this article, we focus on the last two of the actions (process selection and collaborative organizational execution).

A Decision-Support Framework for AI TransformationWe implemented our framework as a decision tree. This implementation:

Reflects real-world complexity. AI adoption is not a single decision but a sequence of interdependent ones. Each node in the tree captures a critical juncture informed by cross-functional inputs.Provides structure. The tree is logical and repeatable, while remaining flexible enough to serve use cases from finance to manufacturing.Promotes organizational alignment. With clearly defined decision points, it fosters a shared language among business, IT, and HR leaders.Scales and is actionable. Each node is supported by detailed content that can be customized to specific domains or regulatory constraints.From Experimentation to ProductizationOne of the decisions in the tree involves identifying the business process experiments set. This set should include processes where the use of AI may (remember that we’re starting with hypotheses) significantly improve productivity, increase operational efficiency, or enhance customer experience. Selected processes must offer the opportunity to measure AI’s contribution, rely on data that is available or acquirable, and be situated in operational environments that allow for experimentation without unacceptable risk.

The experimentation’s results enable the business organization to determine which of the tested processes should transition to the productization set. These are the business processes where AI proved its value, the technical and organizational conditions for scaling exist, and there is a clear path to integration or redesign. Before embarking on productization, each process in this set must then be classified as one that can be AI-enhanced (infused with AI but maintaining its existing structure) or become AI-first (redesigned from the ground up with AI at the core).

AI-Enhanced vs. AI-First: A Practical ExampleTo make this distinction more concrete, consider the core finance operation of paying a vendor. This is a well-understood, standardized workflow (which we have further simplified for this article) that provides a useful lens through which to evaluate AI-enhanced versus AI-first transformation.

Consider the simplest form of the typical vendor payment process:

Receive invoiceVerify detailsMatch the invoice to the purchase orderRoute for approvalsSchedule the paymentArchive the documentsIn the AI-enhanced version, the existing process remains largely intact but is improved with AI at key steps:

Intelligent document processing automatically extracts and validates invoice data.AI models detect anomalies between invoices and purchase orders.Approvals are routed based on learned behavior and decision history.Payment timing is optimized to manage cash flow and capture early discounts.In contrast, the AI-first version reimagines the process, making AI the process’s engine:

AI systems proactively monitor issued purchase orders and work logs to validate what payments are due.Payments are triggered autonomously, based on system-level validation.AI continuously manages vendor relationships through performance tracking, payment optimization, and exception handling.The Decision Criteria: A Strategic ChoiceDeciding whether a process should be AI-enhanced or AI-first is not simply a technical call. It is a strategic decision shaped by business objectives, IT constraints, and workforce capabilities. The table below, whose contents are included in a node of our framework’s decision tree, outlines the logic applied to this decision.

CriterionAI-enhanced if…AI-first if…Strategic Significance & ImpactThe goal is incremental improvement or a quick win.The process is critical to competitive advantage; the goal is transformative improvement or to create new value propositions.Organizational Readiness & RiskThe organization opts for lower-risk implementations, has limited change capacity, or requires moderate workforce upskilling.The organization has a strong innovation appetite, accepts higher upfront risk, and has robust change management capabilities.Current Process EffectivenessThe process is sound but has identifiable bottlenecks.The process is obsolete or fails to meet future business needs.Frequency of Process InvocationThe process is used infrequently, unless the impact per instance is extremely high.The process is used frequently, is critical to transformation promises strong gains.AI’s Potential ContributionAI can automate discrete tasks, improve prediction/optimization within tasks, or provide localized insights.AI enables new ways to achieve the goal, unlocks transformative insights, or replaces large sections.Data Availability & PotentialQuality and labeled data exist for the process’s existing steps.New data sources are available and can be used effectively.Process Complexity & InterdependenciesThe process is highly dependent on legacy systems, where radical change is disruptive and risky.The process is self-contained, or interdependencies would also benefit from redesign.Modularity of Existing ProcessThe process is modular, allowing AI integration into specific segments with minimal disruption.The process is modular, enabling a phased module-by-module replacement.Resource AllocationResources (time, budget, talent) are constrained; enhancement offers quicker deployment with potentially less investment.Significant investment is available, the timeline allows for development, and necessary AI expertise can be secured.The Power of Cross-Functional CollaborationThe table presented in the previous section illustrates why a closely aligned partnership among the business, IT, and HR functions is essential.

The business unit assesses strategic significance and the current process’s role in competitive positioning.IT evaluates data availability, systems integration, and real-time capabilities to support redesign.HR determines whether the talent exists or can be developed to support the envisioned model.Many of the criteria for determining which processes to include in the experiments set, which to advance into productization, and which to enhance or redesign, cannot be evaluated by the business unit alone. For example, IT is best positioned to assess whether the data infrastructure, system architecture, and latency constraints can support AI-driven execution. HR must assess workforce readiness, change capacity, and whether reskilling or hiring is needed.

Without such collaboration, organizations risk deploying AI systems that are technically infeasible, culturally unsupported, or operationally unsustainable. When this triad—business, IT, and HR—is established early, organizations accelerate alignment, adoption, and long-term success.