Azly Rahman's Blog

May 30, 2021

Grandma���s Gangsta Chicken Curry and Gangsta Stories from My Hippie Sixties by Azly Rahman

MY MEMOIR IS NOW AVAILABLE ON AMAZON!

In the following recollections, divided into several chapters, Azly Rahman presents a mixed-genre memoir-snippets of growing up in a world rooted in the pastoral-ness and ruralness of things. The world of his kampong or the Malay village. These are stories of separation ��� of a mind from the body. Of the body from consciousness. Of spiritual consciousness from the reality of things. In these lie the author���s story ��� of separation from his tribe, so to speak. Of culture, its constructions, and complexities. The strange and the familiar has become me. Of the anthropology of the self, globalized in all its absurdities. The central theme is ���growing up gangsta��� in a Malay village that offered the realism and the supernaturalism of things, seen through the lens of a boy in his early teens.

Through the shifting of the narration of the here and then, through poems, rapping verses, and ethnographic notes, he makes the stories accessible to readers of the English-speaking world, primarily in the United States where the author now resides and teaches. It is a story of ���boy meeting the strange part of his Malay world��� yet rooted in his mother���s love as an inner guide, and sanity.

Grandma’s Gangsta Chicken Curry and Gangsta Stories from My Hippie Sixties by Azly Rahman

MY MEMOIR IS NOW AVAILABLE ON AMAZON!

In the following recollections, divided into several chapters, Azly Rahman presents a mixed-genre memoir-snippets of growing up in a world rooted in the pastoral-ness and ruralness of things. The world of his kampong or the Malay village. These are stories of separation – of a mind from the body. Of the body from consciousness. Of spiritual consciousness from the reality of things. In these lie the author’s story – of separation from his tribe, so to speak. Of culture, its constructions, and complexities. The strange and the familiar has become me. Of the anthropology of the self, globalized in all its absurdities. The central theme is ‘growing up gangsta’ in a Malay village that offered the realism and the supernaturalism of things, seen through the lens of a boy in his early teens.

Through the shifting of the narration of the here and then, through poems, rapping verses, and ethnographic notes, he makes the stories accessible to readers of the English-speaking world, primarily in the United States where the author now resides and teaches. It is a story of ‘boy meeting the strange part of his Malay world’ yet rooted in his mother’s love as an inner guide, and sanity.

May 15, 2021

GRANDMA'S GANGSTA CHICKEN CURRY and STORIES OF MY HIPPIE SIXTIES: A REVIEW

The book is a project of retrospective narratives, searching for meanings between the overlapping union of Azly’s conflicting influences. There is also a backdrop of the flux and transformation of a new nation Malaysia – Malaysia’s disconnect with the past colonial master, Britain, harmonious multiracial communities under pressure by race riots, the beginnings of harsh Islamic doctrine taking root in the country, the plague of drugs, and influence of American ideals of the 60s and 70s through film, television, and music. The narratives took place at a time when there was no electricity, running water, and no internet in the kampong.

Hence, existential awareness was more tactile then, than the technological cyberworld of the present. When you order KFC, customers don’t experience the slaughter of the chicken and effort to prepare the food, unlike in the Malay kampong, where the chicken must be chosen, caught, slaughtered, and prepared. There is much more meaning with the mundane in the kampong.

Azly points out that our perception is situational. How we view Ryan O’Neil and Mia Farrow kissing on the big screen depends upon whether we walked out of a madrasa, or saw the film after listening to rock and roll and smoking ganja.

It has taken Azly more than 50 years to take this reflective journey back in time. One can certainly very easily see that his mirrors of reflection are severely tainted with years in the United States. The reflective narrative gives new meanings to events, people, time, and places, altering greatly any sense of reality Azly had at the time, in the best traditions of Paul Ricoeur’s approach to narrative.

As the title of the book indicates, Azly has qualified his whole retrospective with the attachment of his “gangsta” persona. Gangsta is a heavily weighted Black and Latino-American slang word of the “Bronx, New York City and East Los Angeles, rap-hip-hop milieu” indicating not necessarily the road to self-destruction but of coolness and realization of self-recognition at a higher plane. Thus, Azly’s book is a retrospective phenomenological adventure, which has thrown away Margaret Mead’s book “Coming of Age in Samoa”, and turned its back on the ethnographical purity of Clifford Geertz. Instead, Azly has followed Ralph Ellison’s murky sojourn within “The Invisible Man”, trying to find the reality he is immersed within.

One of Azly’s major frames is the challenge of being Malay. As he describes the routine day, things are secular at school in the morning, full of Islamic rituals and dogma during the afternoons, and escaping into rock and roll in the evenings.

Azly is concerned with accepting superstition, the supernatural, the need to submit to authority, being accosted with pedophilia and homophilia, the demands of being born a Muslim, and the temptation of drugs, so easily available in the kampong.

As Azly says within the forward of the book, he is in a quandary. “I sit here writing about a cultural separation, I long for a union.” However, Azly admits that American influence is so pervasive, so additive. This concept of separation is holographic for him. Separation is not just concerned with his sense of identity, when growing up, but also externally with social and political events of the time.

What shows out through the book is that Azly’s American bias still cannot outweigh the Malay soul inside him. The product of this is anguish about the prejudices and injustices going on around him in this new post-colonial world, which still seems to exist with local Rajas and politicians, rather than colonial leaders. Azly metaphorically describes the dirty town of Johor Bahru, to the dirty politics of the country. He talks of all this being made to disappear by giving the streets beautiful names after aromatic flowers, so the mental images of dirt can disappear from public awareness, through metaphorical “whitewashing”.

Azly often looks deeply, introspectively throughout the book. For example, Azly draws a parallel between an execution and being circumcised in adolescence, as is the Malay custom. He ponders the pain and anguish thinking about the time it will take place and the pain that will occur. Suffering comes from the mind, thinking about an event which hasn’t happened yet.

At a spiritual level, Azly forms the hypothesis that pain is associated with learning to be a good person. This theme of shedding something, or separation, so that one can progress to a new understanding reoccurs a number of times. It’s a phenomenon that can occur within one’s own soul, culturally, or indeed nationally – sort of a theory of everything – concerned about change.

This is the brilliance of the book. It postulates there are a number of levels of meaning and reality to all phenomena. There is plenty of captivating descriptive narrative that brings you to where Azly is visualising. This is accompanied by a commentary occasionally, where Azly straight out, takes a stand.

Then there is the cultural level, examining rites and rituals, the beliefs, and assumptions behind them. This is how ghosts and the supernatural can be explained – not within the scientific paradigm, but within a cultural frame.

Then there is inner identity, very unstable and dialectical. Maybe this shouldn’t be analysed too much, other than modifying the old idiom that “you can take the Malay out of the Kampong, but you can’t take the Malay out of the person.”

In the end, it’s the narrative and accompanying semantics that makes up the identity, Azly has been on a sojourn for. We have to go back to the elephant within the room, the gangsta chicken curry. The meaning is all there for Azly. Metaphorically, the dish is as rich as the herbs and spices his grandmother put into the curry. That culinary association sticks, and will always be remembered no matter where, and at period of life a person is passing through.

One of Azly’s projected examples of meaning is – a simple one – the old illegal Mercedes diesel taxies in Malaysia in the 1960s and 70s, are still with us as Ubers today. Meaning just needs reframing.

Azly acknowledges that American culture has changed over time, hinting meaning has been lost, at least meaning for himself. He gives the analogy through music, pointing to the deep meaning of the lyrics in some of the old classic rock and roll songs, versus contemporary songs. Maybe, deeper is Azly’s romantic view of America in the 60s and 70s, and his mourning for what used to be, the loss of rock and roll philosophy.

Finally, one cannot overlook the political commentator frame that Azly is so well known for, particularly in Malaysia. Through snippets, Azly has given reasons why Malaysia is dominated by a Malay narrative and polity today. His messages about racism, corruption, religious extremism, and royalty, are there throughout the book.

For Azly, this book was an almost therapeutic retrospective sense-making perspective of his childhood. For the reader, it’s a valuable retrospective narrative about the personal challenges for a Malay youth in the kampong, back in the 1960s and 70s. In many ways indicating, challenges haven’t changed much for this generation, compared to the generations before them.

In general, the book also provides some window into how an ethnic American person reconciles their cultural origins within their American existence. This will be valuable in contemporary cultural studies.

About Murray Hunter

Murray Hunter has been involved in Asia-Pacific business for the last 30 years as an entrepreneur, consultant, academic, and researcher. As an entrepreneur he was involved in numerous start-ups, developing a lot of patented technology, where one of his enterprises was listed in 1992 as the 5th fastest going company on the BRW/Price Waterhouse Fast100 list in Australia. Murray is now an associate professor at the University Malaysia Perlis, spending a lot of time consulting to Asian governments on community development and village biotechnology, both at the strategic level and “on the ground”. He is also a visiting professor at a number of universities and regular speaker at conferences and workshops in the region. Murray is the author of a number of books, numerous research and conceptual papers in referred journals, and commentator on the issues of entrepreneurship, development, and politics in a number of magazines and online news sites around the world. Murray takes a trans-disciplinary view of issues and events, trying to relate this to the enrichment and empowerment of people in the region.

March 22, 2021

Grandma’s Gangsta Chicken Curry and Gangsta Stories from My Sixties: My New Book from Penguin-Random House

by Azly Rahman

In the following recollections, divided into several chapters, Azly Rahman presents a mixed-genre memoir-snippets of growing up in a world rooted in the pastoral-ness and ruralness of things. The world of his kampong or the Malay village.

These are stories of separation – of a mind from the body. Of the body from consciousness. Of spiritual consciousness from the reality of things. In these lie the author’s story – of separation from his tribe, so to speak. Of culture, its constructions, and complexities. The strange and the familiar has become me. Of the anthropology of the self, globalized in all its absurdities.

The central theme is “growing up gangsta” in a Malay village that offered the realism and the supernaturalism of things, seen through the lens of a boy in his early teens.

Through the shifting of the narration of the here and then, through poems, rapping verses, and ethnographic notes, he makes the stories accessible to readers of the English-speaking world, primarily in the United States where the authors now resides and teaches. It is a story of “boy meeting the strange part of his Malay world” yet rooted in his mother’s love as an inner guide, and sanity.

https://penguin.sg/book/grandmas-gang...

March 7, 2021

Are MRSM (Maktab Rendah Sains MARA) schools a successful failure?

Are MRSM schools a successful failure?

After 50 years of the MARA Junior Science Colleges Project?

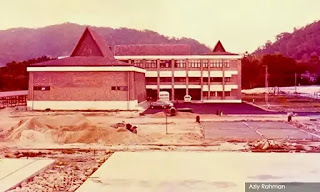

by Azly RahmanThis essay was written in 2010. Still relevant today, on March 9, 2021, an important date for the third MRSM (Kuantan)

As hypermodernising societies such as Malaysia progresses in syncrony with the advancement of capitalism, and as race and religion becomes the foundation for decision-making in education, especially in elitist well-funded schools, Malaysia is faced with another dilemma of education and national development.

Is this country creating sophisticated ethnocentrists that will continue to sustain race-based ideologies?

Maktab Rendah Sains Mara (Mara Junior Science College) schools, well-funded, well-staffed with advanced degree faculties, and well-taken care of by the Malay-centric government may be one example of a phenomena of a successful failure in the system's 50-year evolution.

The school system prides itself in innovative curricular experimentation drawn from best practice of schools, particularly those of the United States; as its original template was based upon.

What educationists will see in the list of innovations are merely aspects of the formal curriculum; upon further analysis lies the hidden and informal curriculum as perceived from curricular theory; hidden is the deeply racial socialisation aspect.

The overall picture lies in the impact of politics and education in the socialisaton of MRSM students. they parrot the teachers, the teachers parrot the politicians, politicians kowtow to money and power - that's an example of successful failure.

We are all economic beings, homo economicus undoubtedly but it is education and only education that is the best means to re-engineer, restructure, re-level, and redesign society.

It is the only means to sustain individual and social progress, as philosophers Dewey and Freire would argue.

Valueless ideologies

While the advanced nations are prioritising multiculturalism, honoring cosmopolitanism, and globalising education, Malaysians, through their endless fights over education are making many steps backwards. MRSM has produced a breed of sophisticated professionals to sustain ethnocentric valueless ideologies out of touch with current cultural realities.

Consider, in a similar vein, how much is spent and attention paid to on yet another high-priced elitist project such as the Pintar Permata at the expense of other schools in dire needs of even basic amenities such as those in Sabah and Sarawak or in many poor states - is that equity and equality for all races? Or is it a showcase based on ignorance of the meaning of equality and education?

With all due respect to the administrators, teachers, parents, and students, I must say about the MRSM school system.

With its insistence on being a Malay-centric, MRSM these days are not preparing children to survive in a multicultural, cosmopolitan, and ever-changing world that requires English as an important skill, and an outlook that is more open to learning about other cultures especially in the context of a rapidly changing Malaysia.

Those specialisations in each MRSM school are merely cliches filled with educational terminologies that are not fully understood but fully acceptable as a platform to appease the needs of the current regime.

Regimentation is necessary it seems to tune the mind of the monolithic mono-cultural students to accept governmental dictates making them in turn, one-dimensional beings.

Are any of those MRSMs suitable for Malaysian children? Or are they merely training and indoctrinating grounds to prop up yet another breed of leaders that will sustain the culture of blind following neo-feudalism of Ketuanan Melayu that itself is a dying specie?

Do parents know what goes on in the culture of the MRSM boarding schools and what goes on in the minds of your children?

In this context, we must look at the difference between education, schooling, indoctrination, mind-control, and liberation in thinking. I would say that the MRSM system is a successful failure.

Retrogressive ideologies

In MRSM, that predominantly Malay-elite secondary institution for the best and brightest young Malays, Malay-centric indoctrination work have been happening since the 1980s. Courses such as Kursus Kesedaran (Self Awareness Courses) are conducted to instill the questionable idea of Ketuanan Melayu, making the children afraid of "Malaysian bogeymen and bogeywomen" and their own shadows.

Open-mindedness is rarely encouraged and students take control over each others' lives transplanting retrogressive ideologies into each other's head, with the help of ultra-nationalist and anti-multiculturalist teachers.

Even if these children survive the ideological ordeal and experience 'tough love' and go on to get their degrees from top American and British universities, they will still be Malays with a shallow understanding of multiculturalism or become more sophisticated Malays with more complex arguments on Ketuanan Melayu.

They will then design policies to affect the needed sustenance of ideology in order to protect the interests of the few. Neo-feudalistic cybernetic Malays are then the new creations of the political-economic ruling class. They run the country and many are now running it down.

As an educator wishing to see Malays progress alongside in peace and prosperity with other races, I call upon us all to put a stop to all forms of indoctrination held especially by the BTN (Biro Tata Negara); an organisation that is of no value to the advancement of the Malays they claim to want to liberate.

It should be taken over by progressive Malaysians and replaced with a systematic effort to promote not only racial understanding through teaching respect and deep reflection on the cultures of the peoples of Malaysia, but also teach conflict resolution and mediation through cross-cultural perspectives. All must question the presence of BTN on campuses. All must reject BTN's programme for indoctrination.

Let us no longer allow any government body of that sort to set foot on our campuses or our schools. As Malaysians we have to demand an end to the further dissemination of racist ideologies.

Open up, not only institutions such as UiTM (Universiti Teknologi Mara) and MRSM but also Umno to more students of the major cultures. We will then have a great celebration of diversity and respect for human dignity in the decades to come.

We need to turn succesful failures such as MRSM into truly successful Malaysian educational ventures; an organic system able to prepare young Malaysian citizens for a diverse, multicultural, and rapidly challenging world - minus the cliches of educational innovation and blind nationalism that will be anti-national in character.

December 29, 2020

SLEEPING WITH GREAT BOOKS: A child remembers the early Seventies

SLEEPING WITH GREAT BOOKS: A child remembers the early Seventies

(excerpt from a forthcoming memoir)

If there were two very close friends in my life and especially during my childhood, they were: 1) An imaginary friend who had multiple personalities who lived on a tree I frequently climb, and 2) Great books I slept with.

I don’t know what fascinated me about the power of words and about imaginary friends I could run around with and have battles with behind locked doors. I will not talk about that imaginary friend for now.

Books, books, books... how great they are. I remember these friends of mine.

Early books

I slept with a world history book Sejarah Dunia, ‘Hikayat Bayan Budiman’ and ‘Hikayat Seribu Satu Malam’. I can still remember the delightfully musky smell of those classics. The history book was light green, the Hikayat Bayan Budiman light yellow, and the Hikayat Seribu Satu Malam was light brown... light reading there was not. Then there were also some bawdy Jawi magazines I found at home, called Mustika I secretly read. Scantily-clad Malay women “berkemban” adorned the cover page. They were not real photos but something that looked like water-color paintings.

I read novels too. I found them in my mother’s closet or ‘gerobok’ as the Johoreans would call it. The novels were in Jawi, the Malay writing that uses Arabic scripts. My mother knew I loved reading and subscribed to Reader’s Digest for me to spend time in between eating, roaming the village, and playing soccer alone in the field across my kampong house. I looked forward to the postman delivering each issue of the book that opened windows to the American culture. I loved the feature sections as well as those that made me chuckle and laugh - ‘Humour in Uniform’ and ‘Laughter the Best Medicine’, and in general, what living in America is about.

We didn't have much in our house – not much “cargo” as the New Guinean Yali, in UCLA evolutionary biologist Jared Diamond’s study Guns Germs, and Steel called possessions -- just the basics of a family on the level of village poverty, but I had enough time and interest to read and be wealthy with myths, tales, legends, and stories. My best friends: words. That became flesh. And inscriptions. And installations of spaces of knowledge and power, as I later wrote about in my doctoral dissertation at Columbia University in the City of New York.

A book about a bloody riot

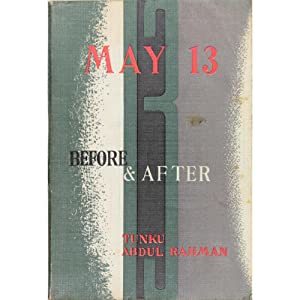

My fondest memory was reading a banned book: 13 Mei: Sebelum dan Selepas or May 13: Before and After, written by the first Prime Minister of Malaysia, Tunku Abdul Rahman. My mother told me it was “haram” to read it and the book was at home because my father who was a soldier in the Malay Regiment in Singapore was given a copy. He spent many years patrolling the jungles as far as Jesselton, Sabah, fighting the Communists who were keen on taking over Malaya and install a Mao-Leninist style rule. So, my father was in the then British Malaya Malay Regiment, though a mere prebet(private) trying to defend the country from Chin Peng, Rashid Mydin, Abdullah CD, Shamsiah Fakeh, and the merry band of Malayan Commies who knew only violence and terrorism to affect social change.

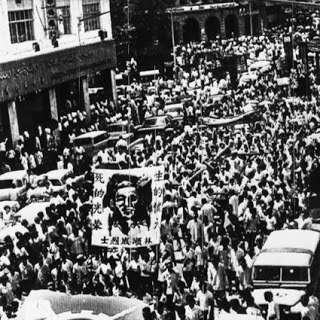

The banned book on the bloodiest incident in Malayan history were Malays fought and killed the Chinese especially in Kuala Lumpur, was about the prime minister blaming the “young Turk” Dr. Mahathir Mohamad for helping Tun Razak (Najib's father) to secure power because the young and ambitious leaders were feeling that the first prime minister was giving too much freedom for the Chinese to control the economy. Later I came across many stories concluding that Tun Razak planned the riots so that he could use the Emergency Rule to take over the country. A theory.

That’s the banned book I read when I was a kid. I was of course confused as to why there were also talks that Malay folks in my village were preparing themselves with martial arts skills and “magic powers” and with red headbands with the Arabic phrase “LailahailAllah” (There is no god but God) were getting ready to travel to the city of Kuala Lumpur in the village of Kampung Baru to do one thing: to “slaughter the Chinese”!

(Today, there is a revival of the ideology of Communism in Malaysia, amongst the leftist-activists in her public and private universities.)

Yes, May 13, 1969. What a horrifying memory of a child of perhaps 10 years old to have!

Before Google

I always had a pocket-sized encyclopedia in my schoolbag; one that has everything about serious and fun facts such as world’s longest, tallest, highest, lowest this and that, capital of cities, famous quotes of the English Language, and tons of information that I could ‘google’ by flipping the pages every time I want I would read the little encyclopedia I bought at an Indian bookstore in the Main Bazaar (Pasar Besar) of Johor Baru of the late sixties.

I was happy that I knew so many things and I could quiz my friends on and be able to answer end-of-day questions on general knowledge my teachers in school would ask the class, the reward for the correct answer was to leave the class five or ten minutes earlier than everybody else.

I could them start playing outside those extra minutes while waiting for my ride home. I could play my ‘bola chopping’, ‘sepak yem’, ‘gundu’, ‘superhero cards’, ‘chepeh’, or those games boys of that time played.

Later when I was sent off to a boarding school in the coastal town of Kuantan at a tender young age of 12, I was introduced to a good librarian (and a homeroom ‘mother’). It was said to be an experimental American school in Malaysia, modeled after the Bronx School of the Gifted in Science and the kids were openly called the “guinea pigs” by the educationists.

We were selected through nationwide IQ tests and most eligible were kids from very poor families who were padi planters, rubber tappers, shopkeepers, and fishermen. In my case, I was a child of a Malay Regiment army prebet (private) and a seamstress who later became an electronic factory worker, assembling microchips for Siemens, in Singapore, going to work at 5 in the morning and coming home on a bus at 7 at night. She raised the five of us with earnings from the two jobs.

Adult books

Coming from a kampong in Johor Baru and as a child getting chased out of bookstores almost daily for ‘just reading’ and not buying those ‘mini-encyclopedia’ from which I tried to memorize the interesting facts, the Kuantan school was like the Library of Congress! There I read an encyclopedia of Charles Manson cover to cover, a pictorial coffee-table book of ‘The Godfather’, world maps, American movies, the story of rock and roll, and The Beatles. Some of my favorite books I read at fifteen were A. S. Neill’s Summerhilland Dr. Spock’s Radical Child Rearing, and later ‘The Wanderers’.

And I fell in love with the Asterix and The King is a Fink series.

At the age of 12 or 13, too, I got hold of a book Education and Ecstasy by the American social reconstructionist in education, George Leonard. It was in my school's library. I liked it and read it twice and remembered the part where he discussed the importance of the child, with the help of adult members of the tribe, to speak about what he/she dreamt of as important data to help members of society to move on.

I thought the sight of children sitting in their little ‘chawat’ or tribal hot pants talking about their dreams to adults in bigger ‘chawat’ interpreting dreams was cool. I suppose George Leonard was very much influenced by the idea of the sixties of which Anthropology was beginning to a break-away from its colonial mode’ with actually the influence of Margaret Mead as a ‘spokesperson of the sixties’.

Later Mario Puzo’s The Godfather novel became a favorite, leading me to read more and more stuff from the gangster-movie genre; The Don is Dead, Omerta, Bonnie and Clyde, etc. Another favorite was Papillon, which was later made into a movie starring Steve McQueen.

It was always a pleasure to be in the library stocked with readings on American culture. Whether influential or not, I read Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People.

No, I was not interested in influencing anyone, not interested in girls, too, because then I thought they were strange annoying creatures, nor was I interested in becoming an influential politician. I was simply interested in the title of it! Sounded like how to see ghosts and communicate with them.

Hanging out, hanging around, and ‘chilling’ I was in that reading joint back in the day, listening to the teachers and the librarian gossiping too.

In my high school library

The library sometimes feels like a Barnes and Noble cafe in New York city - there would always be those little boarding school children hanging out, hanging around, and ‘chilling’ with the librarian-cum-homeroom mother and one of my favorite English teachers! May God bless her soul wherever she is. I will write about my other English teachers later. It was also a gossiping joint.

I continue to read Greek and Roman mythology and my World History book (in Malay) every time I go home. The library of Sultanah Aminah in Johor Baru was another place I loved best.

A deeply shining moment in one of my English teacher's effort to make teaching interesting was when she brought a friend of hers, I think from Universiti Malaya to our English Club meeting and performed this short existentialist play concerning a corpse that kept growing and growing out of the closet, maybe Eugene Ionesco’s short play ‘Amedee’. (Or How to Get Rid of It.)

It was such an effective two-woman performance by the duo Miss Rahmah and Miss Maznah that I got so scared towards the end and had a nightmare right there in the dorm.

That was one of the many moments of effective teaching. Later in life I became very interested in French existentialist literature, reading more Ionesco, and obsessed with Samuel Beckett, Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre and finally immersed myself in Existentialism. I went on to read the major classics of English and World Literature.

My English teacher taught me two words with which I can never forget how excited I was when I was in Form One; the words were ‘nocturnal incursion’. I got so obsessed with the words that they became part of me - I started sneaking out at, many nights and got myself free to roam the city of Kuantan at night and see what ‘nocturnal incursions’ means, and what freedom entails or escape from Alcatraz is about.

I read that novel Papillon, about life in a French prison, three times when I was in Form Three. I read ‘The Godfather’ novel five times. Later I found out that Saddam Hussein’s favorite movie was ‘The Godfather’!

She got us to read a novel, Istvan Zolda, about a soldier in Yugoslavia during the time of the war of the Partisans.

When I was in Form One she told me that I had “perfect English”. I was thrilled, excited, flattered. But I found out later that it was not true at all. I still work with brutal editors for all of my writings, while at the same time editing other people’s work.

May all the good work be blessed. Teachers like them are rare these days; they are now politicized.

My mother smarter than Paulo Freire

Such is the joy of reading back in the day - before Facebook, WhatsApp, iPads, and the culture of Mat and Minah Rempit, Jihadists. And terrorists by any name.

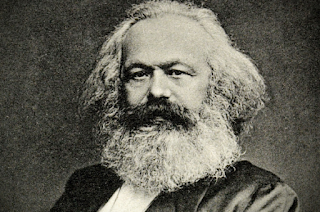

And bless my mother's soul for showing me the power of the word. With her schooling to only Primary Three (Darjah Tiga,) she was smarter than Paulo Freire, the Marxist-Leninist Brazilian educator, I presume. Certainly more peaceful than Marx, Engels, and Lenin combined.

She was my pedagogue. Of hope. And love.

And books? My dear friends they are.

December 27, 2020

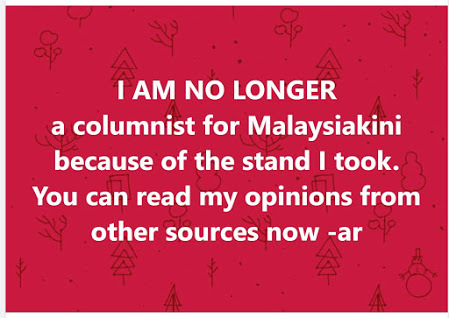

I AM NO LONGER A COLUMNIST for MALAYSIAKINI: June 2020

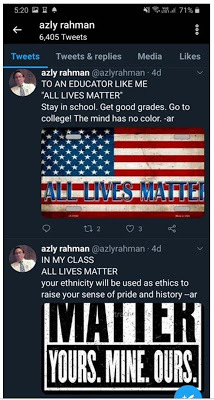

I DON'T SUPPORT THE BLM-VIOLENCE NETWORK. To me "AS EDUCATOR, ALL LIVES MATTER" then. now, and forever. This is my stand. And Violence begets violence. Nothing comes out of it. And I am not a supporter of any Bigot President either. Nor any form of racial supremacy — azly rahman

Below is what I tweeted, after watching the violence in June, 2020: the looting, the burning, the destruction of property and businesses, after the protests.

HERE IS MY RESPONSE TO THE ISSUE (Published in Eurasia Review, Oregon, USA)

The Price Of Not Tweeting Exclusively That ‘BlackLivesMatter’ – OpEd December 17, 2020 Dr. Azly Rahman 3 Comments

The Price Of Not Tweeting Exclusively That ‘BlackLivesMatter’ – OpEd December 17, 2020 Dr. Azly Rahman 3 CommentsFirst, my condolences to the family of George Floyd. And may justice be served on those responsible for his death. This has been a challenging two weeks for me: the end of semester wrap-ups, novel writing continuation, and handling a Gerakbudaya author-interview cancellation issue.

But let me share what transpired the day I tweeted what I believed in, as an educator for more than three decades.

‘Cancel culture story’I was invited to give a Zoom-talk by Gerakbudaya, my publisher of seven books, on apartheid and education in Malaysia, and in fact, I was the one who suggested the series of author-interviews, then “KABOOM!” a day before Saturday 13th, it was canceled. The reason: the editors were perhaps contacted by an academic from abroad and a human rights activist that I had tweeted and posted messages that are supposedly against BlackLivesMatter and therefore disrespectful to the movement and therefore I had to be “de-platformed” immediately.

Of course, things got out of hand and there began the controversy on how I should be behaving like a “progressive” as to how the BlackLivesMatter fanatics had wanted it to be. In short, their argument goes like this: if you are not promoting BlackLivesMatter you are a racist and a Trump supporter and a white supremacist. That’s how many Malaysians too think.

When you get the chance, you can go to the Gerakbudaya page and see my responses, including a letter of apology from the owner, I posted.

Now it seems some human rights activists in Malaysia, as well as academics, are suggesting that I continue to be “de-platformed” and my books taken off the shelves until I “revise my view” on BlackLivesMatter. I find this concerning. But this is Malaysia.

You may visit my Facebook page [https://www.facebook.com/azly.rahman] and have a sense of what matters to me as an educator and why I get turned off by hegemony, social projections, and the meaning of protests when one starts saying that “Until BlackLivesMatter all lives do not yet matter” Or — “PoliceLivesDon’tMatter” or “WhiteLivesDon’tMatter”. These, to me, are violent messages hash-tagged for maximum-viral impact.

“BlackLivesMatter Too BECAUSE AllLivesMatter” was my concluding post.

I also posted that “AllLivesMatter” is perfectly in agreement with what I have always championed for in all my writings: that “AllMalaysianLivesMatter” in a world in which the promotion of Malay Supremacy is ever-present.

So, these and the violence attached to the movement turned me off and I start to protest against the world. I am a teacher essentially and to me “AlLivesMatter” resonates with me better and if I have to chant “BlackLivesMatter” all my life, I might next start hating people of all color, especially the whites. It is a crystal-clear philosophical stand I am taking. Malaysians especially don’t like this stand because Philosophy can be worse than Zoom-Fatigue.

‘Symbols destroyed’Statues are now being brought down such as in Bristol and continuing in many parts of the world, I’d say that’s a natural progression of human action when freedom to destroy them go rampant. Lenin’s statue, Sadam Hussein’s, Leopold of Belgium’s, Columbus — all these symbols of oppression are targets. The French taught the modern world about destroying symbols, by first beheading Louis Capet and Mary Antoinette and today producing theories of deconstructionism. We moved from the physical to the intellectual.

The nature of Man perhaps to destroy as in the Shiva-Brahma-Vishnu in us (Preserver-Creator-Destroyer). But the Biblical stories too, the chosen peace messengers from Abraham to Muhammad destroyed symbols. So, it is part of the inner drive of the primordial self to destroy, I suppose.

BlackLivesMatter protests, triggered by the George Floyd event, gave the inspiration to destroy: from old paradigms of thinking to statues, to properties in the cities and businesses owned by peace-loving-law-abiding citizens. Anarchism seems to be an addiction of the youth these days. The Liberal Left bent on the ideas of change promoted by Communists – that violence is that way too – has possessed the mind of the young. Destruction is the modus operandi to feed the soul of the protester.

Yes, it’s all about inner and outer symbols: Of what one worships and destroys.

‘A symbol of violence?’Of course, the Covid-19 lockdown fermented the anger and sped up the destruction. Today, addiction to protests continue. The only difference is the burning and looting has stopped. Except in the latest case in Atlanta.

Of course, the Covid-19 lockdown fermented the anger and sped up the destruction. Today, addiction to protests continue. The only difference is the burning and looting has stopped. Except in the latest case in Atlanta.

The irony of BlackLivesMatter is that it looked like it worked in concert with looting and burning and destruction. As if planned. Man loves to see things burn when the language of reason fails, avenues for peace closed, and the view that the world is an oyster and the land of opportunities and not to create mayhem is lost. Those who love to burn the city down are merely feeding the Fire within. Whether a meaningful symbol such as BlackLivesMatter is attached to it or not.

I want to continue to spread the message that all lives matter: not the Trumpian of White Supremacy slogan but the very basic idea that we are all humans. There is no question of “timing” here that collides with BlackLivesMatter, nor the metaphor of the two houses, one burning that we ought to save.

This is what made people angry with me — that I refused to “revise my view” and I am not “repenting”. My response has always and will always be this: I am an educator and all lives matter to me. As soon as I step into my classroom, all those in it, to me, are human beings with unique cultures and talents and levels of motivation, ready to learn. My job is to see them only as my students of all shapes, sizes, colors, gender, race, and religious affiliations for me to not only teach – but to learn from.

I have been living with this credo and ethos as an educator since I started teaching 33 years ago. I can only promote the words “AllLivesMatter” however my critics wish to interpret it. I offer no apologies even though many have said that the timing is not right. How ridiculous!? But I respect their views and will defend their rights, although mine will be demolished, in many ways as I have been reading. I stand by what the French philosopher Voltaire would say about respecting and defending other people’s views.

I have been living with this credo and ethos as an educator since I started teaching 33 years ago. I can only promote the words “AllLivesMatter” however my critics wish to interpret it. I offer no apologies even though many have said that the timing is not right. How ridiculous!? But I respect their views and will defend their rights, although mine will be demolished, in many ways as I have been reading. I stand by what the French philosopher Voltaire would say about respecting and defending other people’s views.

Besides, I am no stranger to controversies and how people have been responding to what I stand for. I believe controversies are good especially when they are handled, as the Russian thinker Mikhail Bakhtin would call “dialogically” rather than be an avenue for name-calling, even (strangely) by aging academics who ought to have acquired the status of a Merlin the Magician or a Tolstoy or a Dame Agatha Christie or even a Harriet Tubman: wise old men and women.

‘Does race matter?’Besides the above on the nature of protestation and disagreements, first and foremost, I do not believe race is significant nor emphasizing it brings us any good. And what will violence achieve? What’s the point of chanting and screaming justice in the day and looting, burning, and threatening the lives of others at night—burning down the businesses of people whose lives depend on those.

I have been living with this credo and ethos as an educator since I started teaching 33 years ago. I can only promote the words “AllLivesMatter” however my critics wish to interpret it. I offer no apologies even though many have said that the timing is not right. How ridiculous!? But I respect their views and will defend their rights, although mine will be demolished, in many ways as I have been reading. I stand by what the French philosopher Voltaire would say about respecting and defending other people’s views.

Most of the businesses burned to the ground and looted empty are those family-owned by immigrants trying to survive in a land that is giving them hope to flourish, after escaping persecution. And each one of these people – the Italians, Irish, Armenians, Mexicans, Chinese, Jamaican, West Indian, Japanese, Jews, Turkish, Syrians, Somalians, Palestinians, Haitians, etc. — have had a long history of discrimination, persecution, and slavery too. We have not yet talked about the Native Americans! – in different context than those who lost their livelihood when businesses and neighborhoods get looted and burned to the ground!

So—to you my esteemed readers: what do you think? Which one is better: AllLivesmatter? Or BlackLivesMatter?

Or should race matter at all?

Dr. Azly Rahman

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show...

Dr. Azly Rahman

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show...

Dr. Azly Rahman is an educator, academic, international columnist, and author of eight books, namely Multiethnic Malaysia: Past, Present, Future (2009), Thesis on Cyberjaya: Hegemony and Utopianism in a Southeast Asian State (2012), The Allah Controversy and Other Essays on Malaysian Hypermodernity (2013), Dark Spring: Essays on the Ideological Roots of Malaysia's General Elections-13 (2013), a first Malay publication Kalimah Allah Milik Siapa?: Renungan dan Nukilan Tentang Malaysia di Era Pancaroba (2014), Controlled Chaos: Essays on Mahathirism, Multimedia Super Corridor and Malaysia's 'New Politics' (2014), One Malaysia under God, Bipolar (2015), and High Hopes Shattered Dreams: The Second Mahathirist Revolution (2020). Five of the books are available here. He grew up in Johor Bahru, Malaysia and holds a doctorate in International Education Development from Columbia University in the City of New York, and Master's degrees in six areas: education, international affairs, peace studies communication, fiction and non-fiction writing. He is a member of the Columbia University chapter of the Kappa Delta Pi International Honor Society in Education. He currently teaches courses in Global Politics, Cross-Cultural Studies, and Sustainability, in the United States. Twitter @azlyrahman. More writings here.

November 28, 2020

Chronicling mega changes in the portrait of modern Indonesia as prostitute.

by AZLY RAHMAN

I propose this is an aspect of the novel that is worth exploring as an instance wherein the author crafts the philosophical underpinning of the story of the birth and growth of Indonesia (see Appendix for a summary), a country sold into prostitution by the forces that march history, and how the worldview of the nation is shaped primarily by the pathological condition metaphored by prostitution.

In the protagonist Dewi Ayu the portrait of the new nation as a prostitute and in Conrad Kliwon (Chapter 7) the life force that tried to save the nation from being forever being a whore.

I find this notion of ethos and pathos “worldview of the tragic-existentialism” recurring, in a story elegantly waved with elements of mystical magical Javanese symbolism, well-controlled plot yet presented in the genre of Time-Space-collapse, inspired by the complexity of the sub-plots of the Ramayana and Mahabharatta, the elements of the Theatre of the Absurd or French surrealistic/symbolic/Absurdist theatre, some elements of Javanese syncretist thinking, and most importantly in the tradition of the spirit of Raden Adjeng Kartini the legendary feminist-educator-liberator of the mind, the voice given to women, perhaps true to the idea of “motherland” or “ibu pertiwi” in which women hold more than half of the Earth at every epoch in history — these are the broad techniques and themes employed in crafting “Beauty is a Wound.”

Indeed, I believe, the title signifies the pathos associated with being beautiful, or even exotically and ecstatically and even more so, in this story the exhilaratingly erotically beautiful, as beautiful as the prostitute Dewi Ayu, who, like young and prideful Java and later Indonesia was relegated to become a prostitute to the Dutch, and later to the Japanese, and later to her own “nationalists” and much later by the military-regime-turned civilian-rule of General Suharto. Thus, the portrait of Indonesia as a prostitute whose savior is Communism, the latter destroyed by the purge which saw the mass graves of hundreds of thousands of communists killed by the US-CIA backed General Suharto. So that colonialism can continue in a newer but less visible form. In the novel, pride led to the suicide of the communist leader, Comrade Kliwon.

In my close readings of this seminal chapter on the metaphoring and chronicling of the mega-change of Indonesia, albeit through the prostitutionalizing of the nation, I draw instances of Eka Kurniawan’s use of the philosophizing-chronolizing device, in characterizing Comrade Kliwon, as literary device and subtext.

Reminiscence of the writing of the once 14-year-imprisoned-50s-writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer (“Prem”) in seminal works such as Keluarga Gerilya, Bumi Manusia, Cerita dari Blora — those that presented the point of view of the revolutionary fighters of Indonesia a.k.a the “communists” — Eka Kurniawan’s characterization of Conrad Kliwon is one of sympathy in the tone of the Marxists and the Communists as if continuing the legacy of “Prem” or Pramodeya. Throughout, the classic arguments of the International Workers of the World and the Marxist-Leninist Third International are revisited, giving today’s readers a reminder of what was Indonesian history about and how the struggles between the natives, the nationalists, the communists, and even the Islamists, overseen like a panopticon and synopticon of imperialism (Dutch, Japanese American) continue to define the theme of emerging nation-states such as Indonesia. And like a cycle of human and social progress, there is the high and low tide of revolutionary waves of change in all its bloody and bloodless consequences.

Eka Kurniawan attempted to present a history lesson of the birth of Indonesia, as to how Salman Rushdie skillfully did with the birth of India and Pakistan in his novel Midnight’s Children. In Eka Kurniawan’s work, to be beautiful is to be cursed and raped as to be Indonesia is to be exploited and ravaged and raped as well. To be raped then leads to being giving birth to deformities and monstrosities, as in the march of history and the inevitability of the perpetual birth of civilizational insanity.

“No one knew how Comrade Kliwon ended up becoming a communist youth because even though he had never been rich, he’d always been a hedonist.” (pg. 161).

Herein lie the thesis of this chapter in Eka Kurniawan’s Beauty is a Wound that tells the story of Indonesia during the formative years of becoming a republic, of what I call “the portrait of modern Indonesia as a prostitute” (with apologies to James Joyce’s “portrait of the artist as a young man” and the Filipino playwright Nick Joaquin’s “portrait of the artist as Filipino.

He led a gang of marauding neighborhood kids, stealing whatever they could get their hands on for their own enjoyment: coconuts, logs, or a handful of cacao beans than could be eaten on the spot. One night before Eid, they would steal a chicken and roast it, and then the next day they would find the chicken’s owner to ask for forgiveness. (pg. 161)

There is a sense of foreshadowing of what the nature of transformation the young man, later Comrade Kliwon is to undergo, leading the way to his fascination with Marxism and later to be a member of the Indonesian Communist Party, the seeds of the metamorphosis could be shown in the idea that Kliwon is a thief yet with a conscience, in which perhaps in the idea of the march of socialism towards Communism via the global agenda of the Third International, the rationale of stealing from the rich and taking away their property is clear: destroy capitalism and say that it inevitable historical progress or the march of history for the perfect Communist state to emerge as a “kingdom of God”, a modern supra-trans-millinearistic movement guided by the Hegelian-philosophy- inverted, served by the philosophy of history conjured by Marx (and Engels). (see historical and dialectical materialism as fundamental twin concepts of Marxism and Praxis.) Here the author, Eka Kurniawan is giving the readers a history lesson on the influence of Communist ideas in Indonesia, at the onset of Independence.

His mother, Mina– not wanting the same thing to happen to him as had has happened to his father– tried to distance him from crazy Marxist ideas and anything associated with them, and didn’t care what he did as long as he didn’t end up communist. She sends him to the movies and music concerts, and let him get drunk at the beer garden and buy records, and was perfectly happy with him hanging out with a lot of young girls. She knew that her son has slept with them but she didn’t care. From her point of view, that was better than someday having to see him stand in front of a firing squad, about to be executed. ‘Even if he does become a communist, I want him to be a happy communist,’ said the mother. (pgs. 162-163)

I like the passage above. It is both hilarious and serious. There is so much detail on the process of social transformation embedded, from a Freudian psychoanalytical-ideological perspective. Kliwon’s mother, needless to say, is well versed with “how not to turn a child into a communist” and if one reads the underlying underpinning of the statements on the “hows” of cultural transformations, there are perspectives from Critical Theory in the tradition of the circa-Weimer-Republic Frankfurt School theorizing on society: of the work of Theodor Adorno on the cultural industry. on the fetishes of enslaved-originated-arts-form of jazz serving the bourgeoisie class, and the study of the authoritarian personality, of Jurgen Habermas’s one-dimensional man, on Althusser’s deconstructing of the state into “ideological apparatuses,” on the cultural analyses of Walter Benjamin and Raymond Williams — and so forth. These are the hidden theoretical-treasures of Marxist critique, the writer Eka Kurniawan is teasing the read of Beauty is a Wound with; a vast body of knowledge on the critique of capitalism and culture buried in that passage on saving Comrade Kliwon.

Kliwon was clever and sometimes his way of thinking could be surprising if not borderline insane. He once brought three of his friends to the whorehouse and they took turns sleeping with a prostitute. At first the whore encouraged them to climb up on the bed in pairs because as she said she had a hole in the front and in the back. But none of them wanted to share a hole with a piece of shit, so they just slept with her one by one. Kliwon showed himself to be a selfless leader, inviting his friends to sleep with the prostitute first, and taking the last turn. When the sex was over, the prostitute was met with the depressing sight of the three kids crashing through the door and vanishing without paying. … ‘I asked her if she liked having sex with us,’ Kliwon said recounting the story in the beer garden not long after, ‘and she said that she liked it. If she liked it and we liked it, then why should we have to pay?’ People often enjoyed hearing such stories from him. (pg.162)

Eka Kurniawan attempts to illustrate what the character morally stands for, even when doing business with a prostitute. Even in pleasure and the appeasement of lust and the commodification of passion and the turning of the body into a commodity to be exchanged as utilities in a capitalist economy, there is the dimension of justice in distributing pleasure. This is a deep-play analysis in the (Clifford) Geertzian sense of (anthropological sensibility) what it means to still, be human in a dehumanized world in which the voices of the oppressed — the slaves, the workers, the becak pullers, the padi farmers, the prostitutes — are loud and clear. That within the world of the silent reproduction of the human self, as it passes down the conveyor belt of colonial and post-colonial capitalism, lies a sense of humanism.

There is no moral argument here about prostitution and the patronaging of it but a higher moral standard presented by the character Kliwon. I am reminded by one of the greatest modern Indonesian poet WS Rendra’s poem “Prostitutes of Jakarta, Unite! / “Ayuh, bersatulah pelacur pelacur Jakarta, bersatulah” (echoing the Third International Marxist slogan of “workers of the world, unite) when we speak of the voice given to the voiceless. In larger context and a deeper analysis, herein is the idea, I propose, that the story of Dewi Ayu is the story of Indonesia as prostitute in all its glory and nobility.

In the seventeenth year … (t)he girls fell in love with him, and they showered him with gifts that piled up until the house began to resemble a junkyard. Thinking of nothing else, they held parties almost every night. His male friends also adored him, because he never kept the girls to himself. And that was how they lived. In those years, Kliwon and his friends probably had the happiest lives of anyone in the city. (pg. 163)

Herein lie the idea of hedonism and epicureanism emblematic of the decadent societies in which pluralism means the letting go of the masses to ravage each other sexually as long as the larger picture of exploitation is kept painted in newer colors of domination and in this case, characteristic of the life of Kliwon before he met Communism. I am reminded of the Roman empire and Caligula, with his orgies and feasts of splendor, albeit in this novel the scene of seventeen-year-old fornicating and living in the pleasure dome is nowhere extravagant, nonetheless symbolic of a life of conspicuous consumption.

Conclusion

In this brief writing about the craft of inventing a metaphor, I have focused on Chapter 7 of the novel (pgs. 161-188) on how the character Comrade Kliwon is created to chronicle the spiritual-ideological evolution of Indonesia as a nation-state that was struggling to be free from the shackles of colonialism. Eka Kurniawan’s novel, Beauty is a Wound is about Indonesia the prostitute and how, even in her existence as a whore, there is a deeper beauty of Fate and Free Will at play, of a curse she had to live by, and in the end, it is the morality of living as a prostitute that brings the best out of the theme of the story. This statement may seem to be deeply contradictory at many levels if one does not analyze deeper what the author wishes to convey. Only in the last sentence of the 470-page novel that Kurniawan revealed the reason behind the love for the ugliest human being in the town (pg. 470), Beauty her name. In the end, she is the only one who survived the epochal tragedy of epic proportion, paralleling the genealogical suffering of Indonesia as a prostitute for the more than 300 years leading to Independence.

How did Eka Kurniawan craft the novel to tell the story of the power of curse: of the natives on the Dutch, the latter the rapist, the sodomizer, the enslaver, and the breeder of prostitutes (of young Javanese girls) taken from the villages? Herein lie the theme of deconstructionism, Absurdism, irony, dark humor, satire, and a Quentin-Tarantino-Bakhtinian-Grotesque-carnivalesque style of crafting of the characters as well as the narrative arc.

Reference

Kurniawan, Eka. (2015). Beauty is a Wound. Translated by Annie Tucker. (New York: New Directions)

November 20, 2020

MY CLOSE READING of Haruki Murakami's Kafka on the Shore

AZLY RAHMAN

November 19, 2020

Because a serious work of literature must provoke the senses, agitate spiritual sensibility, and raise questions on the meaning of this and that, it ought to be conceived as a vehicle for philosophical discourse, alluring the reader into the world of linguistic and ideological tempestuality by playing with texture and (borrowing the term for the sixties art movement “Fluxus” meaning conceptual malleability,) the flux-ibility of text as reality, in the mind of the reader. In other words, beyond the physicality of the narrative arc, of interactions of characters, and the Aristotelian formula of story-telling, I believe engaging literature should present and next, possess the reader with metaphysical questions of the notions of beingness, Time and Space, Fate and Free Will, and phenomenology of existence, amongst others. It must do so to create in the reader-responder, the “swing of delight” of the cognitive beingness and must leave him/her with the thirst and hunger offered by the thematic temptations of Philosophy.

Two out of three plates of offerings in the Banquet of Abstract Thinking — Epistemology (Theory of Knowledge) and Ontology (Worldview) — might be worth savoring in one’s reading of a literary text borne out of the womb of Philosophy, be it Continental or Eastern. It is within this analytical framework that I discuss Haruki Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore as a “metaphysical novel”, specifically pointing out instances in which the author present teachable moments in Philosophy, particularly of Shinto-Buddhism.

Each character an epistemology

Haruki Murakami’s 467-page-49-chapter Kafka on the Shore is an elegant translated from the Japanese prose of a hero’s journey of a fifteen-year-old boy from Tokyo who left his home not knowing that he is to embark on a pre-determined complex journey of “self-actualization” which included “killing his father, sleeping with his mother and his sister,” a prophecy that came true reminiscent of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex (pg. 199). Kafka Tamura, as he renamed himself, entered the battlefield of joy and suffering, of the Buddhist notion of samsara, of mediating the complex dilemma of Fate and Free Will, and resolving anger – these in an epic psychological drama of dream sequences of both deeply poetic-erotic and violent proportions (396-400). His quest is to break a curse of being in erotic love with his mother, Miss Saeki (438-444). After journeying through a web and labyrinth of mind-bending experiences as in Gilgamesh’s Enkidu, he resolved the issue of being abandoned by his mother by forgiving her.

How is Kafka on the Shore a metaphysical novel that teaches Philosophy, deliberately?

In this metaphorical and semiotic novel, Haruki uses his characters to impact philosophical themes familiar to Chaos Theorists and Shinto Buddhists. By the former I mean the philosophy characterized by the thinking that life, the universe, and everything is a matrix of patterned randomness and that any insignificant change in one aspect can, albeit in a non-causal way, through Time and Space bring about major systemic changes. What exists is an “everchanging present” in a complex network and weltanschauung of cause and effect (pg. 286-287). In Shinto-Buddhism, which I contend primarily informs this novel, a similar theme could be discerned: of life as the existence of consciousness, of causal relationships, and a reason for the Universe’s interplay between Determinism and Free Will, and that there is a fine line between Reality and the Dream World. There is a blurry notion of Evil but for lack of a better word, “inner demons” or “The Demon Mara” or “dark energy shrouding the path to enlightenment manifested in anger and the attachments to things,” (pgs. 451-452) – these are taught by Murakami through the characters in the novel.

Epistemologically, the main character fifteen-year-old Kafka is a voice for sense perception, discovery, and Enlightenment, as well as the will for a human being to be set free, Nakata the sixty-year-old idiot-savant the voice of the human being imbued by the spirit of Animism (he talks to cats and stones) (Chapter 10) and supernaturalism (he is a vehicle for prophecies), and twenty-five-year-old Hoshino (a truck driver who lectures Nakata on socialism and enjoys cigarillos, women, and liquor), a voice for Socialism and Epicureanism (pgs. 323-326), Oshima the transgendered thirty-five-year-old the voice for Liberal Humanist philosophy (he is a librarian who imparts great ideas and explains them to Kafka whenever he has the chance.) (pg. 181 and pgs. 315-316) These main characters of Kafka on the Shore embody the way human being acquires knowledge and impart them. The special character, a crow named “A Boy Named Crow” represents the powerful god-like inner voice symbolizing Fate and Determinism (pgs. 442 and 280-281), out to guide Kafka and to battle demons, at the end of the story (pgs. 431-434). Even a prostitute serving Hoshina spewed philosophical ideas, (quoting Henri Bergson and Hegel) when she was in the intense heat of serving her client (pgs. 273-274), by virtue of her role as a college student majoring in Philosophy, moonlighting as a hooker. Two characters were crafted from American popular culture: Colonel Sanders (pg. 271) and Johnnie Walker (pgs. 139-149); the fried chicken man and the whiskey guy, serving important roles in presenting the corporate capitalist epistemology slanted towards Pulp Fiction mannerisms, ala radical film-maker Quentin Tarantino’s Absurdist hyper-enhanced representation of characters (see Chapters 16 and 28).

In all these instances, Murakami uses all his characters as promoters of a variety of philosophical offerings, each as a strand of epistemology itself, a reservoir of how knowledge is acquired. Each character is not only memorable but a product crafted with such finesse’ that even challenging philosophical ideas get presented in a most naturalistic way by their actions and the predictability of how this and that person with this and that orientation would do and say. In other words, each of them embodies a strand of the theory of knowledge well, revealed gradually in his elegant way of creating the necessary suspense at end of each chapter, to have the reader savor the language style, and most importantly the philosophical trajectories of the story.

Kafka’s world an ontology

Naming oneself Kafka (pg. 32) evokes a philosophical aura of the world of the main character: of the absurd Man and how “God is dead” notion of life and the existential path one is to take will not only determine the end of the story but also perhaps, alter Fate. There is no higher power or a Moses-looking god as in many a monotheistic religion nor three-million-or-so pantheons and avatars of the manifestations of a monotheistic philosophy, such as Hinduism, in the world Murakami built. There is the world constructed out of the elegant bricolage of psycho-philosophy of consciousness. By this, I mean a world in which the inner and the outer self, if it is to be harmonizing and in a state of “boddhisatvic balance” ought to be a one in which the enlightened self understands the nature of the “inner labyrinth and outer labyrinth” one is in and how one’s existence is both a metaphor and the will to find meaning (pg. 416). Murakami is teaching the reader a basic lesson in Shintoism, I argue. Shintoism, though essentially a folk religion dear to the Japanese, has its influence in the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, or the “Buddha Maitreya” if one studied the genealogy of the two-thousand-year-old Indian philosophy of human consciousness.

The characters are locked in this spiritual-psychological ontology, or the world view in which the universe is conceived as a place fluctuations and metamorphoses of beingness and nothingness, good and bad karma, silence and screams of consciousness, prison-house of language and freedom through death, and the core of these lie in the idea that the root of suffering is the attachment of things. Therefore, at the journey, Kafka’s “reincarnation and the arrival of enlightenment” and the coming of age as the “toughest fifteen-year-old” (pg. 467) lie in “forgiving” his mother-cum-lover, Miss Saeki, and concluding the journey he crafted as a runaway clueless about where he is heading. In the end, his mother, upon accepting his son-lover’s forgiveness (pg. 442), lets go of her memories by burning her three-binder-filled life-long writing (391-392), before allowing Death to take her, in her ultimate goal, whether conscious or not, of leaving this world of things and memories for good (pg. 395)

Ecstasy and the brutal torture and anything in-between is the domains of the control of the Ruler of the Kingdom of Dreamscape, in a world of Freudian Philosophical problematique addressed nightly (or whenever one falls asleep,) should the occasion of dreaming arise (pgs. 386-388). At times, the dreamer wished the dreams to be real and at times wishing otherwise. Either way, life, whether conceived as an illusion or otherwise must continue until the conclusion to the world of “being-in-this-world” as Heidegger terms it — of a world of meaning-making, and of being able to feel the dualism of Mind and Body, as the mathematician and philosopher Rene’ Descartes called it, — either way a conclusion must be reached. Where one goes when consciousness dissipates into Nothingness is a perennial topic of Philosophical and Theological discourses since Man began to love talking about his love for wisdom. That activity is called philosophy or “philos and sofia” or the love for wisdom.

But what is a dream and what is wide awakeness but two circles without boundaries merging and metamorphosing, and a phenomenon conceived and debated amongst philosophers, theologians, and of late cognitive scientists and chaos theorists. This theme is also a feature of the psychology of Shinto-Buddhism addressed in Murakami’s novel.

Conclusion and Reflection

In crafting Kafka Tamura’s world, Haruki Murakami created a set of characters that speak the language of Philosophy, particularly of Shintoism, a folk religion influenced by Buddhism, whose core ideas and premises are similar to the modern-day field of study called Chaos or Complexity Theory. Murakami lets his characters live and breathe, and preach Philosophy. They become important subtexts to the grand narrative of Epistemology and Ontology called Kafka on the Shore. I contend that Haruki Murakami attempts to teach Philosophy deliberately through this novel.

The challenge of doing a reading of any “metaphysical novel” is the ability to deconstruct the text, approaching it from a meta-cognitive and meta-literary perspective, as well as ultimately doing a meta-reading of it. Seemingly, one needs to be equipped with a repertoire of knowledge of philosophical ideas employed by the author to construct his/her prose or poetry or personal narrative. A meta-reading is different, in that merely enjoying what one is reading, of which the aim is to find pleasure in responding to the text. The challenge, especially of reading a work of literature that weaves in key issues and propositions in both philosophies of the Ancients and the Moderns, to both, find extreme pleasure and ecstasy in being absorbed in the eroticism of the philosophical discourse skillfully sculptured into the text, in the process of its creation. It is not enough for literature to merely pleasure and entertain and bring joy and comfort in all its glory of crafting happy endings in the entire scheme of this ideological construct called “poetic justice” much in the tradition of Shakespearean Comedies or the plot of the Ramayana or The One Thousand and One Nights, not enough. More is needed in this world shaped by the interplay between Fate and Determinism, of the randomness of chaos, and the Bergsonian notion of multiplicity and multi-dimensionality of perspectives.

More than the claim above, a piece of work should shatter perceptions, beliefs, and stab and would and even maim the reader by the use of powerful words, sentences, passages, and ultimately elegant prose that carpet bombs the reader’s consciousness, leaving him or her undergoing a reader-response-linguistic karma of sort in the process and in the aftermath of devouring the piece of work. The piece of work must then be a teacher of Philosophy, whose lessons not only resonate in the reader but also render him/her stark naked and left to die on the shore, on tempestuous midnight. But where do we find such a piece that can also be metaphysically addictive and joyfully fatal, and like the Law of Manu destroys, constructs, and sustains this ephemerality called “consciousness” or memories that is said to dissipate upon death? In Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore, I’d say.

I end this brief essay with the words of Kafka Tamura’s inner guide, “A Boy Named Crow” who said at the beginning of the journey:

“… And once the storm is over, you won’t remember how you made it through, how you managed to survive. You won’t even be sure, whether the storm is really over. But one thing is certain. When you come out of the storm, you won’t be the same person who walked in. That’s what this storm’s all about. “(pg. 6)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Murakami, Haruki (2005). Kafka on the Shore. (New York: Vintage)

October 7, 2020

MY REVIEW of Salman Rushdie's Haroun and the Sea of Stories

by Azly Rahman

September 29, 2020

In my close reading of Salman Rushdie’s delightful work of magical realism, Haroun and the Sea of Stories, I focused on the philosophical seriousness, via characterization, of a work that reads like a fiction for young adults. Central to the novel, written in an easy-to-discern (Christopher) Voglerian 12-stage model of a hero’s journey, is Rushdie’s characterization of the key players in this great war of Grand versus Subaltern Narrative or the anti-foundational versus the foundational, and of critical dialogue versus controlling dogma. It is a story about storytelling and how Rushdie deconstructed the most fundamental issue of today’s writing: the danger of the single narrative.

I propose Rushdie's masterpiece, written after his controversial work The Satanic Verses, is essentially a critique of contemporary Wahhabi-Salafi-Saudi-and-Ayatollah-Khomeini-type of Islamism; a grand narrative of an ideology that is anti-story and counter-liberating to the celebration of multiple voices of the human experience, as well as an enemy of Liberalism and Humanism. The following instances in the novel suggest the theme of the author’s meta-story of the art of naming and story-telling. I will first provide its synopsis.

Salman Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories is a story of a young man Haroun Rashid searching for ways to bring back his mother Soraya who ran away with his neighbor Sengupta. His mother, a terrible singer, could no longer stand living with his father Rashid who makes up stories for a living. She preferred “just the facts”. She eloped with the fact-loving-clerkish-skinny-looking Sengupta. (pg. 21) From the ordinary world of urban India Haroun and his father, a prized storyteller-in-the-service-of-politicians (somewhat like the role of the liberal corporate or State-controlled media in endorsing politicians,) journeyed into a land of phantasmagoric proportions, beginning with a bus-ride uphill to Dull lake. This story is reminiscent of the Sufi author Sheik Fariduddin Attar’s The Conference of the Birds (a story about Sufism and the journey towards self-knowledge and enlightenment) to battle the evil kingdom of The Chapwalas, ruled by “Khattam Sud” (a metaphor of “The Last Revelation,” The Final Word”, The Ultimate Truth,” or “The Grandest of the Grand Narrative,”) – to set his mother free.

Haroun the protagonist, riding the “mechanical bird” Butt the Hoopoe (pgs. 67) is a metaphor the vehicle of human imagination as it is used to battle dogma, embodied in the character of the antagonist and arch-enemy of “General Kitab””, the grand vizier of (Herbert Marcusian) One-Dimensionalism named “Khattam-Shud”. Rushdie deployed Haroun not only as a metaphor of the glory of the once-world-renowned and revered–center-of-Islamic learning of Baghdad at the time of the Khalifah Haroun Al Rashid (pg. 216), but as a literary device to launch an attack on the walled-fortress-cum-gigantic ship of dogma that was producing “poisoned stories” (pg. 160) choking the life out of the ocean of stories, of the ocean of mercy, and narratives of multiplicities. Butt the Hoopoe, a metaphor of Simurgh – the king of birds who led other birds on a search of the true self in Attar’s Conference of the Birds– functions similarly as the Hindu god of Flight and Imagination, Indra (or Inner Sensibility,) or the Greek god of messages, Hermes, bringing Haroun to places in the battlefield of ideas in a dystopic world of where “sad stories” are mechanically produced. (pg. 15)

Religious doctrines consist of sea of stories of sadness and salvation and how the soul can be saved in the complex matrix of soteriological paradigm of the fate of the Human Self. Rushdie characterized this notion of Khattam-Shud’s world as anti-story and anathema to the realism of the human experience (pgs. 159-167) I recall William Blake’s notion of the superiority of human imagination over the certitude of dogma as he wrote about the senses five and the power of the sixth sense of human imagination in his poem The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Through Haroun’s collaboration with the mythical-mechanical bird, “Butt”, the notion of grand narration to be waged war against, until storytellers are liberated and the oceans are cleansed of the poisons of the single narrative.

In fighting dogma, it is the “General Kitab” that became Rushdie’s anchor point in his characterization of the semiotics of Liberal-Humanism in this great war with Ideology. The Arabic word for “scripture” is kitab and the general scripture signify, as I read it the sum total of the works of human creativity through the millions and billions of stories weaved from Time immemorial. Stories are what maketh the Universe, as Joseph Campbell might say in his study of myths and the structure of monomyths, making the world an ocean of stories. Essentially it is broad-based liberal education, framed by the foundation of “general kitabs/scriptures/great books,” I believe make the human mind alive and living in a sea of stories, rather than sad and gloomy living in a poisoned ocean of anti-stories filled with glum fish, in a land called Alifbay (pg. 15) or Alif-Ba-Ta or AlphaBeta or the Alphabet or in a land in which Creative and Critical Literacy reigns as how it ought to be. I believe this is another point made by Rushdie in deconstructing the reality of today’s ideological sensibility.

More examples abound in this engaging story of humorous proportion yet its hermeneutics can be applied to the study of the hegemony of the one-truth, all-encompassing, imperializing dogma inherent primarily in all mono-theistic religions — of those creations of Man, through the work of the priest-class, that hates the progress of innovation and creativity in human literary evolution. A key passage from Haroun’s story exemplified the importance of critical dialogue and the battle for ideas in order for a Marxist-type of dialectical-materialism to occur, as in the scene of the Guppees preparing for war with the Chupwalas:

The black-nosed Chupwala army, whose menacing silence hung over it like a fog, looked too frightening to lose. Meanwhile the Guppees were till busy arguing over every little detail. Every order sent down from the command hill had to be debated fully, with all its pros and cons, even if it came from General Kitab himself. … the Pages of Gup, now that they had talked through everything so fully, fought hard, remained united, supported each other when required to do so, and in general looked like a force with a common purpose. All the arguments and debates, all that openness had created such powerful bonds of fellowship between them. “(pgs. 184-185)

Such is Rushdie’s characterization of the importance of critical sensibility in bringing minds together – the essence of unity in diversity in a living democracy.

In conclusion, in deconstructing Rushdie’s notion of stories, the foregoing brief examples which barely touch the outer-crust of the layers of philological-philosophical depth of the author’s critique of Islamism ala’ Khomeini-Wahabbi Foundationalism, I proposed instances in which the author used names that signify the larger problematique of the art, science, and aesthetics of storytelling. Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories is not just a simple and immensely entertaining children’s story but a complex notion of conceptual confrontations cast in a world of consciousness of the importance of the celebration of human creativity through story-telling as an ancient enterprise of cognitive rejuvenations. It is about the need to celebrate the depth, breath, and the magic of multiple narratives to opposed the grand march of the hegemonic single-story jihadism. I end this brief close reading with a line of on an important philosophical argument between Haroun and his arch-enemy Khattam-Shud, the Author of the Ideology of the Single-Story Narrative, signifying the theme of the story:

“But why do you hate stories so much? Haroun blurted, feeling stunned. “Stories are fun

The world, however, is not for Fun, Khattam-Shud replied. The world is for Controlling.” (pg. 161)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Rushdie, Salman, (1990). Haroun and the Sea of Stories. (New York: GRANTA-Penguin Books)

SOURCE: https://www.politurco.com/myth-and-th...

LINK to BOOK: Haroun and the Sea of Stories

LINK to AUTHOR: