Alan Moore's Blog

July 25, 2016

from support

Learning how to become open / engaged / empathetic

Practice:

Open Space and becoming present with 5 senses

The way of the Warrior of the Heart – (Check Bob’s website)

Appreciative inquiry

To engage with time the time it takes to become a craftsman / the time it takes to do a job well – time

Group polyphonic singing

Improv as creative practice

Learning the power of narrative

Collaborative prototyping

Discussion:

The Craftsman asks is what I create for the collective good / ethical nature of craftsmanship

Craftsmanship as an organisational culture

The crafted organisation – how could craftsmanship change the culture of organisations for the better discussion / facilitation.

Reflections:

What would your rules of a creative life be?

Reading:

Suggested reading material – we make 10 recommendations on craftsmanship, personal development, technological, ethical, organizational etc.,

The hand and mind of Craftsmanship

If you want to create the future you have to hack it

Techniques and process of craftsmanship (creative learning)

The process of adjancey (talk by artist / crafts person)

Systems thinking and design

Pattern recognition and building

Developing a new language and literacy to describe realistic alternatives

Rapid collaborative prototyping

Learning to design for multiple outcomes

Culture of openness from the first craftsman’s studio

The Tools of Craftsmanship

Hacking and making / command/shift control

3+ stories of crafting the new

Coding / programming (Johnny Lennon + Raspeberry Pi)

(Code in a day)

Deconstruct something

Build something : A car, a boat, a website,

Prototyping – 3D printing

July 21, 2015

i disrupts the future of work

The future work redefined by all things AI and machine to machine.

What does the future of work look like? Recent reports state that many jobs (42% in the USA) will disappear through machine to machine automation, IoT, and Artificial Intelligence. A terrible thing, or, a good thing? What we do see as The Atlantic states is the diminishment of human labor as a driver of economic growth. For example, Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman, economists at the University of Chicago, have estimated that almost half of the decline is the result of businesses’ replacing workers with computers and software. In 1964, the nation’s most valuable company, AT&T, was worth $267 billion in today’s dollars and employed 758,611 people. Today’s telecommunications giant, Google, is worth $370 billion but has only about 55,000 employees—less than a tenth the size of AT&T’s workforce in its heyday. A recent KPMG report supports this view from a less US centric perspective, suggesting over the next 10 years, the work of 110 million to 140 million knowledge workers around the globe may be handled by cognitive robotics technology.

Below a short interview with the author Derek Thompson

So there is no doubt that we will see a dramatic evolution in the nature of work, having a significant impact on politics, legislation, taxation and the redistribution of wealth (also political), and also human identity and wellbeing.

But perhaps argues The Atlantic, this offers us all a great opportunity to return to a way of existing, of unifying making and creating together for a more fulfilling life. Lawrence Katz, who specialises in the economy of labour writes, the factories that arose more than a century ago,

“could make Model Ts and forks and knives and mugs and glasses in a standardized, cheap way, and that drove the artisans out of business,” Katz told me. “But what if the new tech, like 3-D-printing machines, can do customized things that are almost as cheap? It’s possible that information technology and robots eliminate traditional jobs and make possible a new artisanal economy … an economy geared around self-expression, where people would do artistic things with their time.”

New tools for a new economy.

Journey further:

A world without work. (The Atlantic)

Arnold Heertje: humanising the economy (post)

The reformation of capitalism (post)

Cognitive robotic process automation poised to disrupt knowledge worker market (KPMG)

July 17, 2015

What's next for banking?

Crowdfunding one example of unbundling

I have enjoyed Mosaic Ventures view on the unbundling of the banks. Their observation that it is not a new bank that we need but a new way of banking. There is in my view an inevitability to the arrival of a new ecosystem, as our world evolves that will serve us even better. But to do so we have to have fundamental redesign of what a businesses looks like. Mostly its design is distributed, networked and peer to peer.

If we take Crowdfunding and peer to peer lending as one example, Toby Coppel writes,

In Europe, the regulatory environment is arguably more friendly for new entrants than in the US, and there are startups successfully attacking the banks at scale in lending (Funding Circle, Prét d’Union, Ratesetter, Zopa) and international FX transfers (TransferWise, World Remit). Other areas that provide sizeable profits to the banks are in the early phase of startup development, such as equity financing (Angellist, Crowdcube, OurCrowd, Seedrs), mortgages, payments (Adyen, iZettle, SumUp, Tipalti), personal financial management (e.g. Tink), pension and savings (e.g. Nutmeg, SavingGlobal), working capital finance (e.g. MarketInvoice, Novicap), and even core banking (current accounts e.g. Number26, Holvi).

This is a description of a new infrastructure forming. These infrastructures, unseen, unknown to many has a unique utility operating system, that provides tools to create new possibilities. And, it is the operating system unique in design which becomes the disruptor not the individual entity in itself. Carlota Perez argues in her book Technological Revolution and Financial Capital,

When the economy is shaken by a powerful set of new opportunities with the emergence of the next technological revolution, society is still strongly wedded to the old paradigm and its institutional framework. Suddenly in relation to the new technologies, the old habits and regulations become obstacles, the old services and infrastructures are found wanting, the old organisations and institutions inadequate. A new context must be created; a new ‘common sense’ must emerge and propogate.

Journey further

Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The dynamics of bubbles and golden ages. Carlotta Perez (book)

Crowdfunding, everyone funding startups (post)

Arnold Heertje: humanising the economy (post)

The reformation of capitalism (post)

Beauty in everything and why it matters (post)

January 9, 2015

Estonia pioneers transformational digital citizenship

E-stonia

How do you reengage a citizenry with the process of democracy? How do you enable better government and deliver better front lines services. Services that are higher performing but reduce the capital costs of running these services? How can openness offer new ways for countries to engage a local and a global citizenry? empowering both state and its populace?

Estonia it seems are doing just that by pioneering the concept and associated services of E-citizenship. Technological tools that can make life better for the everyday citizen and businesses. The concept is the first of its kind to bridge the “digital borders” of a country, giving “digital citizens” in other countries new rights in Estonia. In the early 90s, Estonia’s leaders were faced with a grim reality: theirs was a small country with a small population and few resources. If Estonia was to succeed, they knew, they had to find a way to push the country forward. With the digital technologies and the internet having just arrived on the world stage, leaders made a conscious decision to use it to build an open, e-society – a cooperative project involving government, business and citizens that would mold the nation’s path to the future.

In Estonia, the availability of integrated e-solutions has created an effective, convenient interface between citizens and government agencies. Using their eID, citizens can access the State Portal, a one-stop-shop for the dozens of state services connected by the X-Road. Here they can do everything from voting to updating their automobile registry to applying for universities. Each and every citizen is also given an e-mail address for official communication.

Estonia is however pioonering the idea of e-citizenship, Siim Sikkut, who is a member of the government’s strategy unit, explains in an interview:

The primary goal of the e-residency initiative has been straightforward: to make life and business easier for our international partners and non-resident foreigners who have a relation to Estonia – who invest, work or study here and do trade with us. General banking, government dealings, company management, contracts, medical visits; non-residents will have secure access to online services and ability to digitally sign in legally binding manner just like Estonians do. On 21 October, Estonia’s parliament unanimously voted to extend national digital e-residency rights to foreigners by the end of the year. With this e-residency programme, the least populous country in Europe, of 1.3 million people, intends to attract around 10 million “digital citizens” by 2025.

Why is this important? Clearly, by doing so, a small country can attract new revenue flows and commercial activity into its economy. What one might call nonlinear thinking. Estonia can grow its economy and intellectual capital both at the same time. Signalling a new collaborative economic system, it is the death knell of the vertically integrated organisation. Transformation often comes from the edge not the centre, Scotland take heart. In many ways, Estonia is becoming an open universal platform, in tech jargon, that allows the networked two way flows of information to freely flow. When this happens forward momentum is generated. Meaning, a more vibrant citizenry, and a more vibrant economy.

Journey further

i-voting: Internet voting, or ‘i-voting’, is a system that allows voters to cast their ballots from any internet-connected computer, anywhere in the world.

e-business: infrastructure X-Road and eID to create fast interaction and access needed to make commerce work. electronic tax filing, e-business registry and the availability of public records online have pared bureaucratic waste down to a bare minimum.e-oriented government makes an unprecedented amount of legal and tax information available on the web.

e-School system: parents have 24-hour online access to their children’s school activity data and can check everything from grades and attendance records to today’s homework assignment. Using the same system, teachers can do everything from plan curricula to send notes to parents, individual students or an entire class. Students can see their progress online, and even put their best work into a personalized e-portfolio. ProgeTiiger (CodeTiger) and TechSisters are two Estonian initiatives looking to discover techolgical prowess in children.

e-government: The e-government systems used in Estonia are breaking down the barriers between officials and the public, creating an atmosphere of openness and trust. Anyone can log into e-Law to see what their parliamentarians are doing with draft legislation, for example. Citizens can also log into the State Portal to see all of their own government-held records, check who has reviewed that data, and in some cases, set limits to access.

e-health: e-Prescription system (2010) is cutting down on paperwork and doctor visits, saving an untold amount of time and effort. Doctors can now prescribe medicine to their patients in an online environment, without having to physically meet them to write out a paper each time a refill is needed. The patient then simply goes to the pharmacy, presents his ID Card, and picks up the medicine

December 22, 2014

Jackson Pollock unlocking truths about us and our universe

Jackson Pollock. Inner and outer space

In the late 1980’s, my first proper job was working as a designer for the Anthony d’Offay Gallery. I remember the first time I went to the gallery on Dering Street for my interview. The artist exhibiting was Gerhard Richter. His show was made up of massive abstracts. These were made by layering different coloured oil paints onto a canvas and then dragging a silk screen squeegee across them.

There was no form or shape, other than to me that they looked like waterfalls – powerfully majestic, beautiful, crafted, poetic, transcendental. I ended up working with some of the great artists of the late 21st Century. I thought of this happy memory when reading Jonathan Jones article about Jackson Pollock and what abstract art can teach us Abstract art unlocks the truth about the universe.

He writes

It was Jackson Pollock. The first time I visited the Museum of Modern Art in New York, his paintings hit me like waves of power, truth and revelation. But a revelation of what? The unresolved nature of abstract painting is part of its authority. It intimates secrets that seem both personal and cosmic, but it does not spell everything out. His paintings are of inner and outer space. They intuit a complex reality that cannot be put into words. He spins out some delicate weft of insight, at once mystical, scientific and psychological. Abstract art is majestic. Mark Rothko’s paintings in Tate Modern prove that, as much as Pollock did.

And he summarizes

The discovery that truth is subjective is the root of abstract art. It is also a fundamental insight of modern physics. Perhaps that is why, in front of Pollock, I feel I am seeing the shape of the universe itself.

Looking at Pollocks work got me thinking about physicist Lee Smolin and wilderness writer Robert MacFarlane. Smolin writes, No living system is an isolated system. We all ride flows of matter and energy – flows driven ultimately by the energy from the sun. Once enclosed in a box (in a prefiguration of our eventual internment), we die. Macfarlane adds Natural forces – wild energies – often have the capacity to frustrate representation. Our most precise descriptive language, mathematics cannot fully account for or predict the flow of water down a stream, or the movements of a glacier, or the turbulent rush of wind across uplands. Such actions behave in such ways that they are chaotic: they operate to feedback systems of unresolvable delicacy and intricacy.

MacFarlane and Smolin also make the point that our natural world can also use order and repetition, but only when it makes sense, blending the two together, that can as MacFarlane says, lend a near mystical sense of organisation to a place. As a small aside there is a saying, when civilisations fall, the only thing left is art. What to make something that is resilient and enduring?

So what can Jackson Pollock teach us?

That our world is connected, interconnected and networked at a cosmological level.

Open systems thrive on diversity.

That our natural world can also use order and repetition, but only when it makes sense, so nature blends – depending what is needed.

The laws of nature are dynamic.

Real beauty endures not because it is attractive but because it is great work resolved at a macro and micro level.

Creativity is what brings the new into the world

These are design principles. So when thinking about what we create, design and make, then we should heed these principles. They may not be the hard edged tools of implementation, but we always need a set of guiding principles to frame what we believe and what is possible.

Journey Further:

Open systems evolve to states of higher organization

Living on the edge of chaos

Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems (Living Bibliography)

Yeo Valley Farms, a masterclass in business transformation (post)

Openness the new model for society (post)

On Beauty (post)

December 18, 2014

Mikko Hypponen on the failure of the NSA and the mass surveillance state

Your data with destiny

I met Mikko Hypponen when giving a keynote at and F-secure conference. It was a delight to watch his TEDx talk – and reflect on the truly significant implications of the role governments are now playing in monitoring us all. In chapter 5 of No Straight Lines I explored the realities and challenges of how our lives are transformed by data in its many varied forms, and, how this has significant political implications.

The introduction begins, as the shape of our world evolves, we are also in political transformation, both in terms of the political relationship between the individual and commercial organisations and the large Politics of how we organise and run our societies. What should government look like in a non-linear world? Are we creating and running the right systems in the right way? Why is it too many people are disengaged with the process of democracy and civil organisation?

An extract from the book

Data, democracy and identity: who would have thought even in 2005, that consumer politics and societal politics would revolve around data, who has it, who owns it and how it is used, combined with the legal frameworks that protect us as citizens.

Your destiny with data: What happens therefore to the data security, privacy and identity management once aggregated dynamic databases can be accessed and used? And the even bigger question is: how much of one’s identity do people want to display as they navigate the networked world and how much of their personal information will they be prepared to give away, or even reveal, to get something of value back in return?

From an individual perspective, we leave continuous trails of data, plumes of bits of information. It’s the personal exhaust from our digital interactions. These are the shadows and messy footprints of our daily lives. In the highly competitive world of marketing and commerce, this data is being recognised as increasingly important, with companies desperate to harvest, aggregate and refine it for commercial gain. Hal Varian, Google’s chief economist, published a paper in which his research found that the peaks and troughs of Google searches would be predictive in the demand for certain goods and services.

Yet our destiny with data is complex. There are legitimate concerns about who actually owns this information, and when our identities can be pieced together via data flows, privacy becomes a key battleground.

In this talk Hypponen explains why in the context of the NSA and GCHQ the monitoring of all citizens has real and lasting consequences to what we call democracy. The TEDx intro to Mikko’s talk states, recent events have highlighted, the fact that the United States is performing blanket surveillance on any foreigner whose data passes through an American entity — whether they are suspected of wrongdoing or not. This means that, essentially, every international user of the internet is being watched, says Mikko Hypponen. An important rant, wrapped with a plea: to find alternative solutions to using American companies for the world’s information needs.

Journey further:

The NSA files (The Guardian)

A Brief History of the Future: The origins of the internet (John Naughton)

If data is the new oil where are its wells? (post)

Are we naked with or without data? Edward Snowden asks a big question (post)

December 15, 2014

The Reformation of Capitalism

Peter Drucker

In June 2014, Clayton Christensen and Derek van Bever wrote in the June 2014 issue of Harvard Business Review (HBR). “The orthodoxies governing finance are so entrenched that we almost need a modern-day Martin Luther to articulate the need for change.” And they are not the only ones signalling we need a change of direction in how we think our economies work.

In Vienna this year the Global Peter Drucker Forum gathered together the great and the good to explore what next for Capitalism looks like. We have arrived at a turning point,” says the Forum’s abstract. “Either the world will embark on a route towards long-term growth and prosperity, or we will manage our way to economic decline.” The need to move from a linear way of thinking about what we make, how we make it and who we make it with. To a nonlinear economy that is regenerative, and restorative. Why? Because ‘Capitalists are capitalism’s worst enemy’, writes John Kay – ‘and particularly the market fundamentalist tendency which has been in the ascendant for the last 20 years.’ Kay adds: ‘Once we appreciate the historical anomaly of the post-war moment, we might see the capitalism of our own day in a proper light. With its imperious bosses, its overworked employees, and its benediction of uncomplaining servility to the prerogatives of money and power, the ‘new capitalism’ emerges as the same old monster it always was, just larger, faster, and colder at heart than ever’. Feeling chilly?

The reason why we need to transform

There is an urgent need to transform: Our institutions, organisations and economies were conceived, designed and built for a simpler more linear world. Overwhelmed by the dynamics of change, institutions, organisations and economies have become disrupted and unsustainable. There is an urgent need to transform our societies, organisations and economies by better design to thrive in what I call a “non-linear world”. A non-linear world has significant implications for leadership, strategy, and innovation – the design of organisations and economic models as a whole. But, Martin Wolf (Chief economics commentator, The Financial Times) argues there is not enough political traction to create the necessary conditions to bring real momentum to this need to transform. I am not entirely convinced about this. Because the middle ground, the middle class – the average person needs to feel that things are moving forward. It is when this fails real social and political unrest unfolds – as it is currently doing. (Read David Boyle’s book – Broke about the plight of the UK middle classes and its consequences).

Writing in Has Capitalism Reached A Turning Point? Steve Denning writes, This call for a Reformation comes from distinguished pro-business voices in the world—the heavy artillery of capitalism itself. The critiques and the calls for change are many and simultaneous. Big-gun broadsides are coming all at once. Third, these thought leaders are not speaking in euphemisms or hedging their bets. These are flat-out denunciations of, not just one firm, but the whole management culture that prevails in big business. Phrases like “stock price manipulation” (HBR), “corporate cocaine” (The Economist) and “zombie managers in the grip of management ideas that refuse to die” (Financial Times) are typical.

This is in fact requires some major re-engineering of how our economies and societies work. Business journalist Peter Day went to Vienna to speak to some of these leading thinkers about What Next for Business might look like. Here is the link to his radio show In Business. He asked the question, is Capitalism in crisis? Well according to the great and the good – it is. Martin Wolf arguing that the blame however is placed at the door of governments not corporations – who no matter how badly they fail then look to the tax payers to bail them out from their various moral and technical falls from grace.

Of particular interest from the interviews he conducted, the need for Pension Funds to become part of the solution demanding companies operate in certain ways, plus the need to encourage the creation of a new finance and banking system. My take on this is when institutions fail – people learn to get what they need from each other – maybe we are just at the point here where there is enough failure that we do start to conceive, then build a new financial system?

The systemic failure of metrics that only measure the short term: The next point was the failure of metrics that only look at the short term for innovation a metric dictated by the financial sector. Further short-termism results in business may be characterised both as a tendency to under-investment, whether in physical assets or in intangibles such as product development, employee skills and reputation with customers, and as hyperactive behaviour by executives whose corporate strategy focuses on restructuring, financial re-engineering or mergers and acquisitions at the expense of developing the fundamental operational capabilities of the business. (The short term myopia of equity markets).

Having worked on many large innovation projects I can fully appreciate this observation from first hand experience. The point is we need a metric that looks towards the longer term and not be bound by quarterly numbers.

From creating net value to trading net value: another market truth was this swing from creating net value to trading net value. In reality a zero sum game. A new product or service is conceived to serve the collective good – it generates revenue and creates employment vs. hedge fund managers trading value in a winner takes all game.

The end of command and control: listening to Vineet Nayar an Indian business executive, author and philanthropist. He is the former CEO of HCL Technologies, founder Sampark Foundation and author of a management book “Employees First, Customers Second: Turning Conventional Management Upside Down” (Harvard Business Press, June 2010).

His observations on organisational performance, and therefore business performance by putting employees first before customers was illuminating and refreshing to hear. Nayar defied the conventional wisdom that companies must put customers first, then turned the hierarchical pyramid upside down by making management accountable to the employees, and not the other way around. By doing so, Nayar inspired and empowered employees and customers and set HCLT on a journey of transformation that has made it one of the fastest-growing and profitable global IT services companies and according to BusinessWeek, one of the twenty most influential companies in the world. His key points were,

Creating a sense of urgency by enabling the employees to see the truth of the company’s current state as well as feel the “romance” of its possible future state

Creating a culture of trust by pushing the envelope of transparency in communication and information sharing

Inverting the organizational hierarchy by making the management and the enabling functions accountable to the employee in the value zone

Unlocking the potential of the employees by fostering an entrepreneurial mind-set, decentralizing decision making, and transferring the ownership of “change” to the employee in the value zone

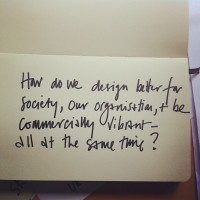

How Do We?

The freedoms of business are always socially negotiated: Gary Hamel argues that corporations have lost sight of this fact. And that when corporations refuse to see this as an absolute – one loses the trust of society. The question is – how far does trust need to break down until society turns its back forever on those institutions. My feeling is we are already there more or less. Hamel argues that today banking and the financial system are so interwoven with politics, business, media and power – they will refuse to see, accept, create and engineer and alternative way of doing things that is essentially fairer and more redistributive of wealth. It is as if the entire western world and then the rest is over the barrel of a financial system that politicians are afraid of Hamel argues. If one thinks about a broken middle class, a dysfunctional political system and an engourged financial system – we have the necessary conditions for disruptive change. Hamel goes so far to say that many businesses and financial institutions are making their money on the public dollar. And, that when power formulates business and governments homogeneously, the welfare of citizens does come foremost to their minds. It is a systemic problem and one that really is about the redistribution of power. This current power play is what Peter Day calls the new depressing normal.

So what to do? Remove the complexity in banking, and create new institutions and functionality in the banking system seems to be the overview. Rein in financial capitalism, and that is why the pension funds will have to play an important role in what next looks like. Because the pension funds support the short term aspirations of hedge funds and the stock market. Because pension funds control so much capital their intervention is a necessary requirement to begin to effect a new way of thinking within the existing system.

Empower and inspire employees with the view that shareholder value will go up, job longevity will go up, profits will go up, your bonus will go up, this will create and build growth. Nayar argues the future of companies is socially orientated, peer to peer and purpose driven. So leadership and management is more about stewardship – caring for the organisation.

Journey further:

Economics does it have any use? (book review)

Who are the real indoor pirates? (post)

Arnold Heertje humanizing the economy (video)

The UK’s social and economic design challenge (post)

The Truth About Markets: Their genius, their limits, their follies (Book)

Yeo Valley Farms, a masterclass in business transformation (post)

December 11, 2014

Yeo Valley Farms, a masterclass in business transformation

The challenge: How do we remove the acute volatility and therefore risk of running a farm? How can we become more resilient and get to a better future? Yeo Valley Farms is the largest organic dairy farm in the UK, and is a great example of how to deal with economic disruption and create lasting transformational change – that delivers better business, without damaging the natural environment.

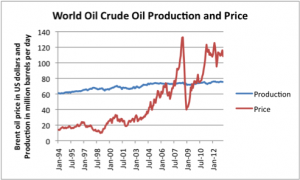

The inevitable rise of crude oil production

Disruption and no end in sight: Yeo Valley farm was faced with an uncertain future for two simple reasons: first, the volatility of running the farm on an oil-based economy (cost of fertilisers, pesticides, and fuel), and secondly, being too small to compete in the industrial supermarket economy. These two volatile variables pointed to a continuous unsustainable reality, and a most uncertain future. Yeo Valley existed in an ambiguous state. The need was to create a resilient sustainable business that could endure, but how to do it?

Thinking systemically: Tim Mead owner of Yeo Valley embraced this ambiguous situation, and explored the problem as a systems challenge. If the farm currently exists in a system that is economically hurting us, how do we deal with that? The answer was to go organic, to remove and reduce the impact of the external volatile forces over which they had no control.

We start with the challenges of farming in the UK over the last 100 years; many small holders were locked into an economic model and way of life that, from a UK perspective referenced against the industrial-scale farming in countries such as Canada, meant that shortly after the Second World War the UK was importing 60%+ of its grain, diary, meat and vegetables. Fuelled bizarrely by the left-over nitrogen stockpiled during the war for munitions, and re-created as a miracle grow fertiliser to exponentially increase agricultural output, but with a deadly endgame of extracting more of natures goodness than we could put back. Ultimately leaving the earth unable to give back what we currently take for granted.

We then get onto the economics of farming in the 21st century, the scale and volatility of the milk market (exacerbated by the financial meltdown of hikes in crude oil) and how one deals with such volatility without being beholden to the power and whimsy of the supermarkets. So part of the design challenge is independence, to be master and commander, as best as one can, of one’s own destiny. And in amongst all of that are the cows that are key to Yeo Valley’s success.

Developing a thesis of a best possible future: Importantly Tim did this for hard headed rational economic reasons, And 25 years ago when Tim made this decision it was considered highly unorthodox. Organic large-scale farms? Culturally it was a bold move, it takes a strong presence of mind and deep conviction to not be swayed by fashionable thinking. Tim had looked far ahead, identifying a pattern that made sense even though the current ideology was to run farms like industrial machines. He sought the best possible long-term future of the farm. Yeo Valley encouraged more local farmers to become organic and form a cooperative, guaranteeing to buy their produce to cope with growing demand.

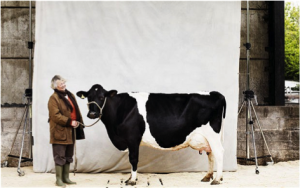

Quality milk requires quality ingredients

Quality of product and customer demand: Running a large farm organically requires some head scratching from time to time, but it is sustainable and Yeo Valley produces the best milk in the UK. He reduced the cost of his inputs, and increased the quality and quantity of his outputs. He created a greater demand for a superior quality product. Yeo Valley makes eight out of every 10 organic yogurts in the UK. Yeo Valley has recently been marketing not because they are a fan of marketing, perhaps quite the opposite, however the strategy of building a strong brand was that when a supermarket decided not to stock Yeo Valley products, customers would be demanding to know why? And supermarkets always respond to customer demand.

Working with the potential of nature: I asked Tim why an organic approach to farming inspired him; he responded by pointing out that to get the best out of nature, you need to respect nature. To do that one must understand it’s a fine balancing act to deliver yield performance of his diary herd and that of the land that supplies the nutrients to the cows to deliver that yield. ‘Push nature too hard’, says Tim, ‘and she will bite you back’, an observation that is so ingrained and implicit in Tim’s worldview, to him, that it’s blindingly obvious.

The Yeo Valley

In Tim’s description of how they farm it’s clear he sees the process of being a whole systems design problem. Tim believes cows perform best, producing greater quantities of, and better-quality milk, under certain conditions. The cows need great product, a wide variety of rich nutrients to eat, to do that requires some nuture and networked thinking about what the cows eat, how to give it to them, and how to keep that raw material coming at the highest-quality level all year round. It’s a complex operation, but when it’s explained it makes, to me at least, common sense. The cows have room to roam, their diet consisting of clover-rich grass grown without the use of artificial fertilisers and pesticides. Wildlife is encouraged to flourish and conservation of the land extends to rebuilding limestone walling and placing hedgerows. In an effort to reduce pollution and food miles, lorries transporting Yeo Valley yoghurts are double deckers. “Everybody who is a farmer deep down understands the balance of animals and nature and crops and rotations, and I think most farmers have an in-built sense of what is the right thing to do,” he says. Care for the land and the animals at Yeo Valley is a prime concern and all production sites are certified by the Soil Association.

Yeo Valley products

Yeo Valley produces over 2,000 tonnes of yogurt each week. The Yeo Valley Organic brand continues to grow and the range now includes: Yeogurt (fruity, low fat and Greek varieties), milk, children’s products (First Yeos, Little Yeos, Yeotubes and Smoothies), butter, cream, Frozen Yeogurt, ice cream, compote and rice pudding.

A cooperative business model: The farm and the business cannot run without people so people count too, as a working community, especially since they work as a cooperative. Yeo Valley understands what I would call true corporate social responsibility, which is about doing it because it is the right thing to do, and they are backing the people upon whom their business depends This was evident in the way Tim helped establish the Organic Milk Suppliers Co-operative (OMSCo).

Soil Association

Before 1994 all milk was sold by the Milk Marketing Board, but under deregulation of the sector farmers were left to sell direct to manufacturers and organic milk producers suffered from a shortage of buyers. “When organic farmers were looking for somebody to buy their milk, we encouraged them to get together and promised to buy their milk for a period,” says Tim Mead. Usually, manufacturers don’t like it when farmers get together because they don’t like the strength that working together gives them, but Tim encouraged organic milk farmers to set up a co-operative and promised support by giving them a guaranteed market. Yeo Valley Organic continues to take milk from around 100 OMSCo farmers in the South West to supplement the milk that they produce on site. But for Mead this is simply the logical way of running his business. “If things are not in balance or sustainable then they aren’t going to be there forever, are they?” he asks. “I think most farmers feel that they have to take care of the land and what they are farming, and I think most of them feel, financially, it is difficult because the returns from farming average at 1.5 to two per cent on capital over the last 50 years,” he says. He blames a distorted market for this low return.

A crisis of scale: “A true market consists of many buyers and sellers and a market price, but when it comes to the growth of multinational food processing companies, farming is something that just doesn’t scale up,” he explains. “Somebody is not just all of a sudden going to own 100 dairy farms because to look after dairy cows you have to be on the ball. So, taking dairy as an example, there are always going to be many farmers, but there are three or four companies that buy 80 or 90 per cent of milk.”

In search of authenticity: Yeo Valley Organic has become a market leader because it is a brand with authenticity. Organic is about buying into an ethos and a way of farming. A true organic consumer wants to buy from a credible outlet.

A values based approach: Tim Mead is big on values “Maybe we have started to learn lessons from the financial sector across other sectors. Maybe big is not always beautiful, maybe multinationals aren’t always the answer. If you are just doing things for profit, who are you serving? The shareholders or the people who buy your products?” Yeo Valley represents an ethical framework and values based approach to commercial and business practice, by asking – is what I create for the collective good?

Short term thinking can leave you vulnerable: In contrast, Tim believes that those agricultural companies completely dependent on an oil-based economy are in fact unsustainable, and vulnerable to a volatile global economy. He believes that his overall operation although organic, which does present its own unique challenges, is more enduring and economically viable. Nothing is wasted. It is also a fine balancing act between now, tomorrow and ten years time, but this constant headache means Yeo Valley Organic constantly invests in its future by investing in the whole ecosystem. It constantly invests in the quality of its soil, its herd, its manufacturing capability and its people. One simply cannot separate one from the other.

Yeo Valley key points:

1. Ambiguity: Tim Mead was prepared to look towards the long term future of the business. He was able to properly diagnose the underlying forces that were hurting Yeo Valley by thinking systemically. Some people and organisations become paralysed by fear when they face an uncertain world.

2. Adaptiveness: Tim was able to take that systemic diagnosis and was able to take and make decisions where he could explore alternative narratives for his Yeo Valley. Organic vs. oil based economy, scaling up Yeo Valley as a farm to be able to stand toe to toe with supermarkets that dominate our food economies. He also has this philosophy called Plan A, At Yeo Valley we have what we call plan A,” he says. “The A stands for again—every time you turn around a corner there is something new and you have to start all over again, so the plan changes every day.”

3. Openness is resilience: Yeo Valley produces a superior product, and has developed a thriving business by working with and respecting the diversity of nature, and its eco-system.

4. Participatory cultures: Yeo Valley works very hard with its local community, as the farm works a great deal of the YEO Valley so people and place are seen as critically important. Yeo Valley farms also does a great deal of educational work bringing children and adults onto its land to share its knowledge ways of working and philosophy. Lastly it cooperative model has proven to be highly effective.

5. Craftsmanship: Today Yeo Valley Organic is a well-known organic dairy company, with many awards for product quality and innovation, and a Queen’s Award for Enterprise presented in 2001 for the revolutionary way it worked with its farming suppliers, encouraging them to turn organic and giving them long-term ‘fair trade’ contracts. The firm won another Queen’s Award for Enterprise, for sustainable development, in 2006 for its “Approach to management with continuing support for sustainable UK organic farming thereby minimising environmental impact.

6. The gamer seeks and EPIC win: Yeo Valley Farm went from a small farm going out of business into a company that delivers great healthy products, is profitable and contributes to the health and wealth of the UK.

Journey further:

Myra Goodman on organic food systems as common sense (post)

If you want to create the future you have to hack it (excerpt from No Straight Lines)

Pasona, the vertical farm in Tokyo (external link)

John Mackey CEO of Whole Foods on Conscious Capitalism (video)

Joel Salatin on the potential of large scale organic farming (video)

The Ecology of Commerce: A Declaration of Sustainability (living bibliography)

November 30, 2014

What can we learn from Shaker design?

The People called Shakers. In search of the perfect society

William Morris once said, If there was ever a golden rule it was this. Have nothing in your house that was neither useful nor beautiful. These are the words of a Craftsman, dedicated to only bringing the good into the world. This quote came to my mind whilst looking recently at the elegance and craftsmanship of Shaker Design. The Shaker guiding principles were of simplicity, utility and honesty. Shaker design is so purposeful in concept and so economical in execution that is meets William Morris criteria perfectly. And also I believe we have much to learn from the underlying principles of Shaker design.

Consider a Shaker chair: four posts, three slats, a handful of stretchers, a few yards of of woolen tape for the seat. It could not be more simply made, but this is the work of a master craftsman – whose beliefs and purpose are manifest in the final product. It is the work of an unhurried and loving hand – the engaged craftsman is the committed craftsman.

What really distinguishes Shaker design is something that transcends utility, simplicity and perfection – a subtle beauty that relies almost wholly on proportion. There is harmony in the parts of a Shaker object. And in fact, there is harmony within and between all Shaker objects. Chairs, pails bonnets, a dwelling room, a barn, a kitchen garden, the land itself. Again, we return to purpose, the inner life and will that motivates one in their task at hand. The Shaker overriding belief was that the outward appearance of all things of the earth revealed their inner spirit. What is we could today create and inspire organisations to operate from the same defining belief. Perhaps not a religious one – but one where purpose, the work is in fact inspirational?

A Sisters gown

The purpose of work was as much to benefit the spirit as it was to produce goods. Mastery of craft was a partnership with tools, materials and processes: gaining experience in patience that served the craftsman in many other areas of life. This reminds me of a great teacher I had – who has sadly passed away – a carpenter by trade, who also worked with the ethos that a job well done was not based upon watching the clock or fighting time – but to give oneself to the task, to labour as in love, until he would say, that will do. The Shakers version of this mantra, was do all your work as though you had a thousand years to live, and as if you would die tomorrow. The result, an environment that was uniquely their own, colourful, graceful, efficient and indeed comfortable. Their work transformed common objects in works of uncommon grace. The effort of a Shaker craftsman was not dependent on style but ‘truth’.

Interestingly – there is little written about aesthetics or design in Shaker journals – it was the context and the culture they existed in that which was the invisible means that shaped their work. So, if organisations wish to create great work, to bring the new into the world in elegant and timeless ways they must first address the key issues of purpose, context and process.

What – passes as style, is interesting to reflect upon and that with great beauty endures. Just think 1980′s power suits, big hair, and jumpsuits. In 1842 Charles Dickens, mocked the Shakers, “stiff backed chairs,” Whilst a modish Englishwoman observed that a Shaker dress would, “disfigure the very Goddess of Beauty.” The important question to ask is what has endured? The Shakers did not reject not spurn beauty but they worked hard, labouring over reinventing it.

In praise of the craftsman

The Shakers also had one golden rule – back to William Morris, do not make that which is not useful. And so it was their interpretation that all useful things should be also beautiful. God, as Mies van der Rohe said, was in the details, and you never know an Angel may come one day and sit on that chair – it had to be worthy of such an event.

It is said that, the most appealing thing about Shaker design was its optimism. Those that would lavish care on a chair, a basket, a clothes hanger, or a wheelbarrow, clearly believed that life was and is worthwhile. And the use of every material – iron, wood silk, tin, wool, stone – reveals the same grace. The Shakers recognised no justifiable difference in the quality of workmanship for any object, no gradations in importance of the task. All, must be done equally well. Whether it was the laying of a stone floor in the cellar, the making of closet doors in the attic, or the building of a meeting house, the work required nothing less that the skill, purpose and dedication of the craftsman.

What can the Shakers teach us about Craftsmanship and cultures of creativity? Many things.

Journey further

The Craftsman (Richard Sennett)

Lessons in craftsmanship: Tashi Mannox – Tibetan Calligrapher

Crafting a new pursuit of happiness: re-ordering work and play

On beauty

Love your work

How to create an innovative and sustainable company

November 27, 2014

Peter Kropotkin, Mutual Aid and Darwin

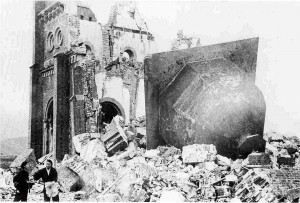

Urakami Tenshudo, formerly the largest cathedral in East Asia, and ground zero of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki.

From a talk by Patrick Bateson given at Kings College Chapel some 30 years ago. The insight to deep human wisdom and indeed life – is the power of cooperation.

He begins his talk thus I am disturbed by the way we have created a social environment in which so much emphasis is laid on competition – on forging ahead while trampling on others. The ideal of social cooperation has come to be treated as high-sounding flabbiness, while individual selfishness is regarded as the natural and sole basis for a realistic approach to life. The image of the struggle for existence lies at the back of it, seriously distorting the view we have of ourselves and wrecking mutual trust.

It was this quote that caught my full attention: The ideal of social cooperation has come to be treated as high-sounding flabbiness, while individual selfishness is regarded as the natural and sole basis for a realistic approach to life. Indeed, the idea that participatory cultures and tools could realistically provide better insights, ways of doing things, creating more stable political structures, health care systems (large and small) have been dismissed as whimsical, nostalgic, quaint, folksy, and down right stupid. Yet the truth is, that our capacity as a species to progress is based upon our extraordinary capacity to cooperate and collaborate. The 4th principle of No Straight Lines is Participatory Cultures and Tools. Partick Bateson continues,

At the turn of the 20th century an exiled Russian aristocrat and anarchist, Peter Kropotkin, wrote a classic book called Mutual Aid. He complained that, in the widespread acceptance of Darwin’s ideas, heavy emphasis had been laid on the cleansing role of social conflict and far too little attention given to the remarkable examples of cooperation. Even now, biological knowledge of symbiosis, reciprocity and mutualism has not yet percolated extensively into public discussions of human social behaviour.

..the appeal to biology is not to the coherent body of scientific thought that does exist but to a confused myth. It is a travesty of Darwinism to suggest that all that matters in social life is conflict. One individual may be more likely to survive because it is better suited to making its way about its environment and not because it is fiercer than others. Individuals may survive better when they join forces with others. By their joint actions they can frequently do things that one individual cannot do. Consequently, those that team up are more likely to survive than those that do not. Above all, social cohesion may become a critical condition for the survival of the society.

Journey further

True knowledge exists in a network

Systems change through people power (Stanford Social Innovation Review)

Humanness of network knowledge

What do we know about participatory cultures?

The promise of an open innovation platform

Ushahidi: a story of non-linear innovation

Cooperation (a selection)