Leslie Helm's Blog

June 16, 2023

Fukushima blog Yoichi Tao unlocks and raises the steel ba...

Fukushima blog

Yoichi Tao unlocks and raises the steel barrier blocking the dirt road. “This area Is off limits, but they let me have the keys,” he says. A few minutes’ drive through dense jungle where monkeys scamper across the road, we reach the hilltop home of the Iitate Planetary Radio Telescope. It was built in 2000 to measure solar flares. A massive radar shaped like a cupped hand still towers over the facility, but the telescope had to be moved in 2011, when radiation from the meltdown of three nuclear reactors along the coast drifted here, making it dangerous for scientists to continue their work here.

Tao pulls out his Geiger counter to show me that the radiation level remains high today 12 years later, because it snowed that day bringing the radiation down to the ground and into the region’s rivers and lakes. But Tao gets angry at those who say the region should be abandoned. Although mushrooms foraged in the surrounding forests still contain unhealthy amounts of radiation, vegetables, meat and other food products from the region are tested regularly and have been healthy to eat for years.

Tao is founder of the Fukushima Sansei no Kai, whose goal is to promote the revitalization of Fukushima. It’s a challenging task. On the one hand, he wants to lure people back to the sprawling village that has shrunk to less than 2,000, one third the size it was before the accident. On the other hand, he wants to underscore the harm the nuclear accident caused the entire region so that the government will spend more money to support efforts to revive the region.

Tao moved to the region in 2017, when the government announced it was safe to return. Tao who grew up in Hiroshima where the first atom bomb fell, says has felt a kinship to those in IItate whose lives have been disrupted by radiation. A former physics student who was expelled from Tokyo University for participating in demonstrations, and later became a top executive at Secom, the nation’s leading security services provider, Tao tapped his extensive contacts in Tokyo to help recruit health workers, scientists and agricultural experts to the region to help establish necessary facilities including equipment for testing food for radiation so villagers could feel safe eating the rice and vegetables they grew. Although such tests did find some elements of cesium in early tests, he says that with the exception of the food foraged in the forests, all food is grown in the region is now safe to eat.

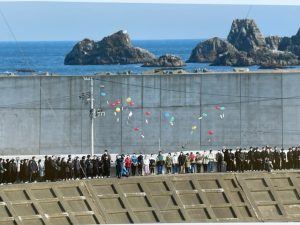

Tao says the nuclear meltdown should not be seen as an accident. It was the result of a series of poor decisions Japan made to prioritize rapid growth and heavy energy use over health and safety. The 2011 nuclear meltdown occurred when a massive earthquake launched a tsunami that flooded a nuclear facility along the shore cutting off its power supply. The backup generators for the plants had been placed in the facility’s basement in line with a General Electric design whose goal was to protect the power supply from tornados. There was little concern about tidal waves because the utilities believed any threat from the sea would be stopped by the 19-foot seawall they built nearby. They never expected there would ever be a 42-foot wave like the one that crashed over the seawall in in 2011, flooding the nuclear reactor, flooding the back-up power plants below, and making it impossible to shut down the plants in time to prevent three of six nuclear reactors in the facility from melting down. An emergency center established a few miles away was also cut off from power, leaving the center unable to access a special computer that was supposed to tell authorities in which direction the radiation would go.

As bad as the original design of the nuclear plant was, Japan’s response was equally poor. The tidal wave that washed over the sea wall and onto the nuclear power plants also swept through the nearby Ookawa Elementary School. Teachers at the school had received a tsunami warning but couldn’t make up their minds as to whether to evacuate. Their indecision contributed to the death of a 100 people, the first of some 2,000 people who would die as a direct result of the tsunami and the nuclear accident. The ravaged remains of the school have been preserved as a memorial to the students and a reminder of the many poor decisions that magnified the impacts of the Fukushima disaster.

In the first days after the disaster, neither the utilities nor the Japanese government shared with the public the extent of the danger they faced engendering deep distrust. And when the nuclear facility started releasing radiation to prevent the reactor from exploding, the Japanese government told residents to move away at first three miles, then 15 and finally 30 miles. Tens of thousands moved to distant towns and cities. But many residents initially evacuated to the hills in nearby Iitate, 15 miles away. Only later did they learn they had moved to the very area where the wind was taking the radiation.

“The radiation released by the nuclear plants was swept by the wind up here against the mountains,” says Tao. The snow then carried the poison cesium into the soil, the region’s rivers, and its lakes. “The government had supercomputers measuring the weather; they knew which direction the radiation was going,” says Tao. “They should have been warning people to avoid the Iitate area.”

Tao is one of dozens of idealists who have moved into the Fukushima area with the hope of bringing life back to a village that has shrunk to less than 2,000 residents, a third the population it had before the nuclear accident. Tao, who studied physics at Tokyo University, was expelled from the prestigious school for engaging in protests. Later he worked as a successful executive at Secom, Japan’s largest security services provider. Now he is using his vast contacts to bring scientists, medical personnel and activists to the village to help in the rebuilding effort.

While the government has poured tens of billions of dollars to help revive the region, as with so many government responses to crisis, much of Japan’s effort has focused on pouring concrete, including more than $12 billion on a massive new seawall that residents complain cuts them off from the sea on which they depend for fishing.

Although Iitate had three good schools and very few children, the government spent $40 million on a new elementary school. It now must bring children from distant villages to try to fill the classrooms, says Tao. Other pointless projects include a new town hall that holds 300 people. Japan tends to support large construction projects for the immediate jobs they create and because construction companies contribute campaign funds to politicians.

Similarly, the Japanese government has provided funds for a massive facility called the for testing robots, including drones with the hope that more robotics experts would move to the area allowing it to become a robotics center.

While the center hosted a robotics conference recently, and the facility has been used to test drones and other devices, but there is no evidence that robotics experts have any interest in doing any robotic research and development in the area.

While the center hosted a robotics conference recently, and the facility has been used to test drones and other devices, but there is no evidence that robotics experts have any interest in doing any robotic research and development in the area.

The Japanese government has also moved forward on some projects without consulting locals. They used heavy equipment to scrape radioactive soil from the fields, for example, crushing the network of clay pipes that are so critical to draining water from the fields. “You shouldn’t call them the Environmental Protection Agency; they are the environmental destruction agency.” The scraped radioactive soil from affected areas of Fukushima have been placed in one square meter black bags that each hold about 35 square feet (about the area of a queen-sized bed) of soil. There are an estimated 14 million of those bags scattered across the prefecture. The Japanese parliament passed a measure some time ago in which it agreed that the burden of storing those bags would be shared by the entire country with every prefecture taking their share. Understandably, the prefectures have refused to accept the bags, so Fukushima has no choice but to store them temporarily in trenches.

Where there has been limited success, it has been in some more distributed approaches that he supports. Under one program, for example, the government has offered $100,000 grants to young people with ideas for businesses. His daughter received one such grant. He takes me to a warehouse-like space in a former big-box store that his daughter is turning into a facility to encourage invention. “It’s like an inventor’s garage,” says Tao. There are various projects in the works, including one for a system to grow wasabi and another an approach to reusing waste products as insulation.

Odaka, a town closer to the nuclear disaster area, has developed an approach that has been successful in launching new businesses. Several young entrepreneurs participating in the “Next Commons Lab,” a venture capital group of sorts subsidized by the federal government.

It has launched startups including haccoba, which is successfully selling sake with unusual flavors. The company says it benefits from a law the requires sake brewers to stick to simple ingredients when making sake. By calling itself a “Craft sake brewery,” the company has the freedom to add other ingredients including hops, fig leaves and grape skins. The sake has proved so popular that several restaurants in Tokyo have become customers and the rest of the several hundred bottles per batch quickly sell out online. The company now plans to triple production.

It has launched startups including haccoba, which is successfully selling sake with unusual flavors. The company says it benefits from a law the requires sake brewers to stick to simple ingredients when making sake. By calling itself a “Craft sake brewery,” the company has the freedom to add other ingredients including hops, fig leaves and grape skins. The sake has proved so popular that several restaurants in Tokyo have become customers and the rest of the several hundred bottles per batch quickly sell out online. The company now plans to triple production.

One reason for the success of Odaka is its active local community. One center for that community is the Futabaya, an inn that suffered flooding from the 2011 Tsunami. Inn owner Tomoko Kobayashi and her husband had to leave the area following the nuclear meltdown, but returned in 2013, using government compensation to rebuild the inn, which reopened in 2016 when it quickly became a favorite hangout for researchers and activists.

As tragic and difficult as that period was, Kobayashi remembers it as an exciting time. “I felt so free,” she says. Every week she would have BBQs or dinners and everyone from aid workers to scientists would gather and talk about all the work that needed to be done.” When trains finally started to pass through the area again, it was Kobayashi who planted flowers in front of the train station to brighten up what had become a bleak landscape. Kobayashi has become a networker. She helped launch a museum in a home offered up by a friend where local artists could display their work.

Kobayashi felt a kinship to Ukraine, which had suffered from the Chernobyl nuclear meltdown. She visited Ukraine five times and came to develop many friends in the area. Now, despite the challenges that continue in her own hometown, she has worked with young people in the area to raise money to contribute to Ukraine’s war effort. A young man who would like to see the region’s watch-making expertise be better utilized, has started manufacturing a special watch. Earnings for the sale of the watch are donated to nonprofit groups operating in Ukraine. Meanwhile, her husband, Takenori, volunteers at a local fire station where equipment was installed to allow people to check food for radiation.

Others have also pitched in to bring life back to Odaka. Down the street from the Inn, Miri Yu, a Korean novelist and playwright born in Japan. She moved to Odaka in 2015 and launched a radio show to focus attention on the concerns of  residents in the community. In 2018, she remodeled her home to create a small bookstore and coffee shop called Full House that remains one of the few commercial establishments open in the neighborhood.

residents in the community. In 2018, she remodeled her home to create a small bookstore and coffee shop called Full House that remains one of the few commercial establishments open in the neighborhood.

Although Odaka has benefited from government compensation schemes, the subsidies have also had the perverse effect of discouraging people from returning and investing in their communities. Many prefer to continue to receive the government compensation rather than try to rebuild their businesses. Odaka’s population is now 3,000, down from 13,000 before the nuclear accident. In nearby Namie, the town has seen its population drop 90% to 2,000. Former residents who rebuilt their lives elsewhere don’t want to be uprooted again.

Although Futaba, in a different area from the Futaba Inn, opened to returnees in the summer of 2022, for example, it still has only 50 residents, down from 9,000 before the accident. Many homes in the neighborhood have caved in roofs  caused by the original 2011 earthquake. Even those returning to work at Futaba’s city hall are commuting from outside the area.

caused by the original 2011 earthquake. Even those returning to work at Futaba’s city hall are commuting from outside the area.

Although the land along the ocean has been scraped of topsoil and can now be farmed, many landowners are choosing instead to lease their land to utilities who are using the land for solar farms. Fukushima has decided to depend on renewable sources for 100 percent of its energy including solar power and hydrogen. But the rest of Japan, which had temporarily shut down its nuclear plants, is restarting them and is even planning to build two new nuclear facilities to the north in an area also famous for its earthquakes. One farmer, however, returned to his land and is growing flowers and vegetables. Although he might have made more money leasing the land for a solar farm, he says, “I want to move. I don’t want to sit around at home.”

Another problem with the way compensation was handled was that it was typically paid to the man in each family, many of whom squandered the money at pachinko parlors that were quickly established to suck up the large sums these men suddenly found themselves with, says Karin Taira, who works for “Real Fukushima” leading tours of the areas affected by the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown.

Another obstacle to development has been the high rents that remain in the region despite the many empty homes. Former residents are reluctant to rent out their homes in part because of a sense of obligation to their ancestral ties, but also because strict tenant protection rules make it difficult to evict tenants. Consequently, even if a new business does have a successful launch, the companies have trouble finding employees who are reluctant to move without affordable housing. Taira, the tour leader, says she was lucky that Kobayashi, the inn keeper, was willing to rent her space behind the inn.

Many efforts have fallen short. The notion of Futaba as an arts center isn’t anywhere close to being realized, though there are some interesting murals.  And the nuclear disaster museum offers a broad picture of the disaster, although it doesn’t do enough to pin the blame on bureaucrats and utilities officials who made bad decision. The government has spent far too much money on concrete and not enough on helping to make the affected areas better places to live. That’s the area in which community activists are hoping to make a difference.

And the nuclear disaster museum offers a broad picture of the disaster, although it doesn’t do enough to pin the blame on bureaucrats and utilities officials who made bad decision. The government has spent far too much money on concrete and not enough on helping to make the affected areas better places to live. That’s the area in which community activists are hoping to make a difference.

April 9, 2023

Helm Dock

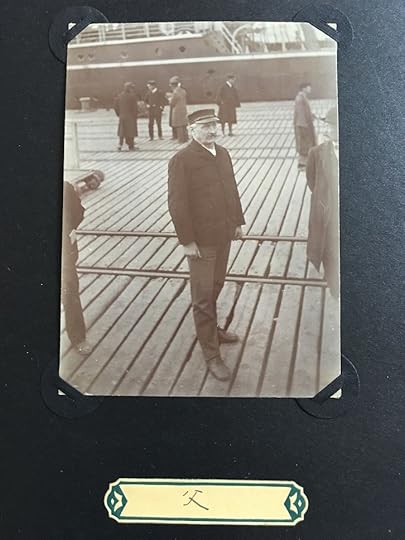

I had long heard stories about a site in Yokohama where Helm Brothers built its barges and tugboats. At the turn of the century, in the late 1800s or early 1900s, my great grandfather, Julius Helm, would go with the company’s carpenter into the woods outside of Yokohama to help him select the best trees to cut to build the ships.

Then some years ago, Toshiko, my father’s second wife, who lives near Negishi station in Yokohama, sent me a clipping about a sign on a bridge that marked the location of Helm Dock. The story didn’t say where the bridge was so I never bothered to follow up.

But then I came across some pictures my Uncle Ray had taken in the early 1950s when he had been stationed with the U.S. Army in South Korea and had visited my parents in Yokohama during a break.

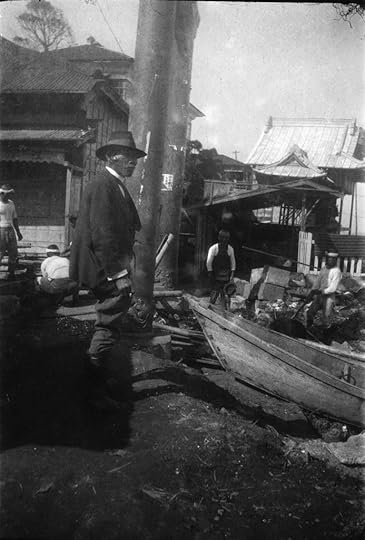

He had taken a picture of my grandfather, Julie Helm, looking on as a barge was under construction.

Now suddenly this picture of my mother made some sense. I had Long assumed she had visited some shipyard, but now it seems likely this picture was taken at Helm Dock.

Then something else slipped into place. When the Japanese version of my book came out, Joji Tsunoda reached out to me. I have written about him on this blog before. Joji told the story he heard from his uncle. Shortly before his father married, Joji’s uncle was walking passed the dock when he heard a large Danish gentleman screaming at some Japanese workers.

The Danish man, Wolff, had been Joji’s grandfather, who worked for Helm Brothers. Joji’s uncle went home and told his sister, who was engaged to be married to Joji’s father, that she was about the marry the son of a devil. At the time, seeing the picture above, I assumed that Wolf had managed Helm Brothers operations at Yokohama harbor, but Joji later told me that Wolff had been manager of Helm Dock. And as I was going through Joji’s father’s treasure trove of Yokohama pictures, I came across one taken about 1919 that I thought could be a picture in the vicinity of Helm Dock.

Now I was truly curious. I went through records of properties in Yokohama that the Helms had once owned. On the list was a very large property at 200 Takegashira, Negishi. That must be it, I thought. On this day, Japan was playing the United States in the World Baseball Classic. Everyone’s eyes would be glued to their television sets. It would be a good day to explore. I took the train to Negishi Station and asked a policeman for directions. Go to the river then turn right before crossing the bridge, he said. He warned me that Takegashira was on the other side of the river, but that there was no sidewalk on either side of the road and the traffic was heavy.

I thanked the kind policeman and walked the half a mile through a rather bleak landscape toward the river. Then I spotted a sembe, rice cracker, store. The lady was making her own rice crackers on an electric grill and they looked delicious. She said her husband used to make the crackers but she had taken over and was experimenting with different recipes. Fortunately most were the classic soy sauce and sesame sembe I like best. I wanted two gift boxes and she let me select my favorites for each box. I could tell she was listening to the baseball game on the radio. Every now and then she would go back into the store and pause for a couple of minutes. She was going to put my two gift boxes in two separate bags, but I asked her to consolidated them since I would be walking for a while. She folded up one of the bags and slipped it into the one bag with the two large boxes of sembe and I was on my way. She recommended that if I had time I should see the sakura at the park nearby. I thanked her and went on my way.

Carrying my large boxes of sembe I walked along that wide ride until I finally reached the river. I walked along the river, checking each bridge for signs that might say Helm Dock. There was nothing for two bridges. As I approached the third bridge, I looked across what the policeman had described as a river, but I now realized, was more like a canal. This is what I saw.

There was a tiny bridge, under which was a stone ramp–what could well be the remains of the Helm Dock. I crossed the canal, and walked along the side of the bridge looking for a Helm Dock sign. There was none. Meanwhile, big trucks were speeding past awfully close to the railing–one came within a few inches of me. I gave up on my search for the sign. Why would they put a sign in such a dangerous place anyway! I crossed a bridge and found a side entrance to the building sitting atop the bridge. I saw a lady with a bag of groceries headed for the apartment building. I told her I was looking for Helm Dock. “That’s it right there,” she said, pointing to the narrow space between the apartment building and the tiny bridge. The apartment building had been built right on top of where the ship-building site had once been. When I tried to ask more questions she shook her head: “The final game of the world baseball tournament is about to start. I nodded my head. I understood. The streets were empty and I had nobody else to ask. I didn’t know how to get to the hilltop park the sembe lady had recommended so instead I took a bus to Sankeien, a beautiful garden park in the neighborhood where my great grandfather had once summered. I still have a cousin who lives on what locals sometimes called Helm hill. I was hungry so I went into a soba shop in time to see the patrons celebrating Japan’s victory over the United States. Batting and pitching star Ohtani had come in a relief pitcher in the final inning to strike out his Angels teammate and the stadium had erupted with cheers. The old men in the soba shop quietly cheered too as the broadcast station kept repeating the best plays of the game. “Japan is not doing so well these days but at least were at the top of the world in baseball,” said one old man. You know, it’s not well known, but Ohtani’s father worked at a Mitsubishi Heavy factory in this neighborhood. Spread the word. He’s really one of ours.” I was happy for Japan, and happy that these men were adopting Ohtani as a local boy. The economy was weak, salaries had hardly budged in three decades and the recent Olympics had been a disaster. Now, finally, Japan had something to celebrate. Meanwhile, I was pleased by my own little discovery. I had found the Dock. On closer examination, it seems clear that the photo from Joji was taken from Helm Dock on the other side of the same bridge!

January 2, 2023

Three Gaijin Letters from Yokohama in the aftermath of WWII

Park Hotel, Gora, Hakone Japan Sept 15, 1945

Dear Brother John Kessler,

Finally the World War has ended, and we are all still alive. Who would have believed it? We are profiting by the kindness of Archbishop Spellman, Archbishop of New York, who honored us today with one of his pleasant visits, and who took it upon himself to carry our correspondence to America. Mail in Japan is not functioning as yet for foreigners. (Mssr. Spellman gave us a gift of $250 and instructed Captain Cyril Curtis, an Australian, to buy us supplies. It was this Captain who flew the Archbishop here. Incidentally, he is one of our old boys. And now I am going to begin to relate a few of the vicissitudes of war we underwent.

St. Joseph College, established 1901

St. Joseph College, established 1901In the month of September,1943, the 29th, I believe, the police came to tell us that all the foreigners on the Bluff in Yokohama must evacuate. We immediately searched for a desirable and convenient place. We discussed for quite some time whether should move to the seashore or take up new quarters somewhere on the Tokyo plain. Finally we decided, after the New Year 1944, to live in the mountains. We were able to rent St. Joseph’s College for 12,000 yen a month. This allowed us to move into the hotel in the Hakone mountains at the bottom of “Big Hell” [a hot spring.] We used thirty and a half trucks to transport the most necessary and important things to Gora. These trucks went irregularly from the 20th of February 1944 to the end of March. The first time I went along in a truck. I almost had an accident. The roads here, as you know, are very steep and our truck didn’t use gas. It was one of those charcoal burners you no doubt remember. Well, the one I was on stopped and almost rolled into a ravine.

Finally, one after another, we all arrived for good on the 17th of March. Living here was very trying because in the month of March it was very cold, with much snow, and there was no furnace installed. As the hotel had been neglected during the war, the windows and doors didn’t close very well. By the followings winter we were able to install a stove in the study room and it was O.K. One of the best things about the hotel was the fact that there were warm baths of mineral water coming from one side of Big Hell (which you know.) Unfortunately, it is only from time to time that we have this warm mineral water.

Toward the end of April 1944, we started school with seven pupils. Now we have forty boys and girls. At the present, I have 14 pupils taking music lessons, most of whom are girls. They are using three of our five pianos. I left one piano in Yokohama, taking a chance on it; the fifth was taken to Tokyo and fortunately was not burned. The little organ we had in the second parlor at Yokohama was sent to the Gyosei (Morning Star School) and burned there.

In Tokyo, the building at the Morning Star School was not bombed, but four buildings caught fire and burned. Fire from our neighbors spread to the large school constructed of reinforced concrete, then to the Brothers’ house then to the science building, and finally to the tailor shop, kitchen and refectory. We especially regret the loss of our rich and valuable library and the wonderful museum, which took go many years to develop.

At Kobe our school building was bombed and burned, but our Brothers had already moved to the country. Father Fage(Benefactor and Affiliated Member of the Society) was caught in his burning church and trapped by falling debris. He was burned to death while trying to save the Blessed Sacrament. What a beautiful death for a missionary after having been at the post in Kobe for fifty years.

At Osaka the Meisei (Bright Star School) suffered great damage due to incendiary bombs. All was burned except the building constructed of reinforced concrete.

At Nagasaki, the Kaisei (Star of the Sea School) suffered damages due to the atomic bomb, the new weapon which Hitler hoped to use to crush the allies.

Star School at Sapporo was spared as also our school at Yokohama. But our neighbor, the sisters [St. Maur’s], were burned out at Yokohama, Tokyo and Shizuoka. The third story of the main school building at Yokohama caught fire by accident, and that on Christmas Eve 1944. We still own our school in Yokohama and will come back if there are pupils. We will return there, soon, perhaps. In the meantime thieves have not scrupled to steal many things, among them curtains from the windows and the large drop on the stage in the auditorium. Today, two of our brothers , Bros. Crambach and Gessler, received an obedience to return to Yokohama to watch over St. Joseph College.

You did well to leave for America because the internees of your [American]concentration camp were moved to our old country house near Yamakita [in the mountains outside Yokohama.] They were not well treated especially towards the end. One man (Emery Jones) died of hunger. American fliers let fall 40 sacks of supplies for them. One sack went through the window of the old confession room.

Now you see, I am writing my old pupil and walking companion to return old favors and to acquaint you again with the French language. When are we going to take our next walk together. Here in the country near the Grand Fujiya Hotel it is very beautiful. The big shot of the American military authorities have taken over the Fujiya Hotel as their quarters. On the 6th of Sept we received our first visit from American soldiers and drank to their health. The next day they took many photographs and some movies of our Brothers and pupils for American papers. If you watch carefully you many see them. They also promised to send some to Dayton University. We are now 24 brothers. Bro. Gerome left here last spring to die in Tokyo of an ordinary sickness.

Bro. Bertrand.

2) Tales of a Mixed Race Teenage Survivor

Letter from John Schultz — Jan 8, 1946

Dear Ray[image error],

I thank you very much for your nice letter which I received it yesterday. I reached San Francisco on 18th of December last year. It was lucky for me that I have found two American Red Cross men on the ship. When the ship reached San Francisco, these two men brought me to the American Red Cross in the city. The lady in there was very kind to me. On the first day, I slept in the Y.M.C.A. But it is the first time for me in United States since 18 years that I don’t know where to go. I even don’t know how to go to the restaurant. So I did not eat anything on that day. The lady in the Red Cross worried [image error]about me and put me in the Buddhist Church in S.F. because there are lots of Japanese people, and I am used to it with Japanese character.

On the second day, I went to see Bro. Tribull. He was very glad when he saw me and at the same time he was laughing because she put the Catholic boy in the Buddhist Church.

At his place, I was told about your telephone number. So when I went back to Church, I have phoned you, but you were not there. I heard that you went to Jujitsu lessons. On the third day, I went to see him again and he introduced me to other brothers. I will tell you an interesting thing that those Japanese people in the Church don’t believe that Japan was really defeated. On the same day, at half past six, I took a train from Oakland and went to Corvallis, Oregon. It took me 21 hours. I met my father at Albany. He was very glad when he saw me. I went to my uncle’s house. I spent my Christmas at his house. After three days of staying in Corvallis,1 took a bus and came to Olympia. 0lympia is a small town, but it is very beautiful. Perhaps I can say that it is one of the most beautiful town I have ever seen since I came to United States. I used to live near the Capitol Bldg, but it was raining all day that I had no chance to go and see it. After three days I took a bus and came to Renton. First 1 got off at Seattle (my home town) and took another bus to

Renton. I am in my aunty,s house now. She is very kind to me. I am in here for ten days already. That means I have traveled three states in ten days. Even the circus cannot travel three states in ten days.

I am very glad to hear that you are attending to school. I have wasted three and half years of school, because when the war broke out, our source of money from America was cut off. Afterwards, Mr. Haegeli told me to come to school, so went, but two months after, school was closed because Bluff was in the fortified zone. After the school was closed, all the teachers went to Hakone and opened the school there, but the police did not permit me to go there.

When Japan declared war against America on 8th of December (7th in U.S.) I was only 15 years old, so the police did not say anything to me. But on the first and second day, I did not go out anywhere, because I was afraid of the police. 1 have gone to the school for a month after the war was started. After that, I went out to work in the typewriter company in [image error]Tokyo. They paid me only 15 yen ($1) per month. With that much money, I helped my mother.She was her very glad much when I sent so much with the money, but I helped her quite much with other thing, because I lived in Tokyo and ate the meals at the company.

The government and the people were very kind to me at the beginning of the war, because they were winning all the time. But when they were defeated at the Island of Guadal Canar (crossed 1) and lost the way to go to Australia, the government began to talk bad thing about America to the people, and they forbade to use the enemy people in the company. So ten months after, I was out of job and I came back home again. After that, my uncle used to give us little money, and we made the farm on the back of our house to raise the vegetables. The government even tell the people to give out all the Jazz records. Persons who did not give out these records were be punished. They said that they cannot fight against America when they are listening to the American music. After I was back from Tokyo, I was at home for about ten months. Afterward, Mr. Haegeli told me to come to school, so I went into 1st High School class from Sept 16, 1943. It was too difficult for me and Mr. Grosser taught the Algebra, which we have to learn in one year, he taught in two months, so I don’t even know the addition of the algebra. The school was closed on the 22nd of Dec 43, and all the foreigners have to move out from the Bluff. Honmoku was also the fortified zone. It was lucky for us that we were out of the zone. After the school was closed, the government made more strict law against the American people who was not interned. I was not permitted to go out from my house unless if it is not necessary. Even they don’t permit me to go out to the town to buy something. I was only allowed to go around my house and I could go as far as Sagiyama. I was not permitted to pass the tunnel and go to the other side of the town. Once, I went to the shore, secret,and on the way back home, I was caught by the police. He took me to the police station, and did not let me go out for half a day (I was not in the jail) That day, I don’t know how many slaps and kicks I got. After I came back home in the evening, I got sick, and I went into the bed for eight days. Then I came back home and sat down,that was the end for me. I could not even stand up on account of the kicks I got. It was 15th of February 1944. I will never forget this day. This is secret to everybody except you. Even Donker doesn’t know about this. After that, I was strictly guarded by the police, I have to write the diary and bring to the police station every week. I have done this till the date of the air raid. After that, what I can do was just stay home and help my mother. When the B29 begin to appear on the sky of Tokyo, most of the rich Japanese and all the foreigners except the enemy people had gone to the country. We could not go because we are enemies of Japan. That is why, on 29th of May 1945, we were burnt out. Donker Curtius , Mr. Mayes, Eddie Duer, Bryden, Gomes, and rest of other enemy people were also burnt out. The air laid began at nine o t clock in the morning, and finished at eleven o’clock. Two hours after, there is no more fire. At the same time, there is no more Yokohama left. [image error] used to say “Gone with the fire” for Yokohama, Americans dropped average of two bombs to every people of Yokohama (including small and big bombs) Believe it or not, but it was written in the Japanese newspaper. For me I got one extra[image error] bomb than other people, we got three of hundred pounds incendiary bombs into our house, I think you know how small my house was. The air-raid siren alarmed, when I was still in bed. That time, the planes are over our house already. Whenever they bomb Tokyo, they use to fly over our house. That is why, [image error] thought they are going to bomb Tokyo again. I was counting the planes in the bed. First line was with ten planes, but they did not drop any bombs. Second line was twenty planes. Third was thirty three, fourth was fifty two. And with the fifth line of hundred one planes they dropped the bombs around your house and Honmoku. I will not forget that noise, when the bombs are coming down from the sky, I cannot remember anything but, when the bombs came into my house, it made a big noise, and at the same time, what I can see was only the black smoke and the red flames of the fire. At this time, I got a burn on my hand and on my leg. It was the hottest and the coldest day I ever had in Yokohama. During the fire it was very hot and in the evening it was very cold, because I have no more house and clothing, I came out with on gray short pants and one [image error]pink sweater. I came out with no underwear, no underpants, no shoes and no socks. I was wondering what shall I do this winter when the war does not finish: but luckily the war is over and we won the war, so the army supplied me with the clothing. After the air-raid, I walked around my house, but I could not find my mother and sister. On the next day, I found my mother and sister’s body in the canal. Both suffocated to death by smoke. That day, I can’t even understand what the people are talking about, because I lost my mother and sister at once, word that I cannot forget was: the neighbor told me that mother and sister must be glad because they were killed by the American bombs. Two days after, I made a small shack with burnt tin and burnt wire. During the war time, we could not get any wires and nails; but after the airlaid you could find the tins, wires, and nails in everywhere, but they are all burnt ones; I used to live in this small shack for two and half months. On 15th of August, Japan surrendered and there was a negotiation that the US Army is going to come into Japan on the 26th of August. But they postponed till 28th because there was a typhoon, my shack was blown away. After that I used to live in the air laid shelter, because even I rebuild my shack, it [image error]was in the typhoon season. Three days after, I met one captain and I begin to work for him as an interpreter. I worked for him for three weeks. After that I was sent to Manila as a recovered personnel. I got on C54 from Atsugi and went to Manila via Okinawa. It took only ten hours. I was in 29th Replacement Depot (25 miles south of Manila) for four weeks I used to get better food and better treatment than the ordinary soldiers, because I was a recovered person, I was in there from October 2nd to October 30th. Afterwards, they sent me back to Japan, because I was civilian. They told me to go to Tokyo and go through the American Consulate in Yokohama. It was not my fault. It was the army who made the mistake. I have landed on Atsugi Airfield on 1st of November. I was in Tokyo for one month. During that time I went through the American Consulate, and the army put me on the ship called LT. S.S. Leonard Wood. They know that I am going to Seattle, and they put me on the ship that goes to San Francisco. But it was lucky for me, because the ship that goes to Seattle left Yokohama game time with us, and this ship went into the storm and lost all the lifeboats and one man.

I left Yokohama on the 4th of Dec. and reached San Francisco on 18th. Donker Curtius was interned three days after the war started. When I went to his house to see Bouldwin and Henry on the 8th of Dec., he was very intoxicated, because he was so discouraged by the outbreak of war. But he came back from the camp in the end of 1944, because he got sick. After he came back, they have moved to the back side of the Honmoku middle school. During the war time, I did not visit him so many times, because we were both enemies of Japan. Maybe I didn’t even visit him ten times, after the war was started.

I myself was told by the police not to visit the enemy people of Japan. On 29th of May, he was also burnt out. His house was burnt and his neighbors were not burnt. Afterwards they have rent the room from the neighbor and they are still there. Since Jimmy and Joyce were Japanese citizen, they could go any place they want to go. His grandfather was interned when the war was started, but he came back home three weeks after, because he was too old. He died in 1942. After the school was closed, Jimmy was just playing around the house, but Joyce was attending to Koran Gakko till the date of air raid, Jimmy is still small but Joyce is very big now. She is only little bit smaller than I. On 29 of May, his house was also burnt down, and they are living in the air-raid shelter now. I saw both of them once after I came back from Manila. His father is working as an interpreter now. When 11th Airborne Division occupied Sendai, he also went to Sendai. He is still there now.

Japan had a short of food during the war time. I think you know that. The time when you left Japan, the sugar and the rice was already rationed. After the outbreak of war, the food condition became worse and worse. In 1942, even the fish and the vegetables became rationed. In the same year, the fuel like charcoal and wood became rationed. In 1943, they used to give us half of the food what we need. In 1945, we could not get anything. The fishermen does not go out to fish, because they were afraid of the submarine and the sea planes. After the air raid, the food what they gave me for 20 days was just enough for me for only four days. They used to give a little bit of rice and hard soy beans and some shoyu. They gave me only 2 sen worth of salt per month. Vegetables once in about three weeks; frozen fish, once in about three months. I did not see the meat for three years.After Saipan was taken by the Americans, we could not get any sugar. In 1945, eight pounds of sugar cost 5000 yen in the black market. So I got sick after U.S. soldiers came into Japan, because I took too much sweet at once. When the army came into Japan, I was weight only 85 lbs., (only three times as heavier as a turkey) and I am 135 lbs now. The day when I went to Manila, I weighed 110 lbs. That means I have gained 50 lbs in 4 months.

In Washington, we have “liquid sunshine” every day. These few days, we have frost in the morning, but usually it is very warm. (Much warmer than Yokohama) If it is fair weather, we could see Mt Rainier from our house.

I’ll close here, otherwise there will be no limit. Please give my best regards to your parents and Larry. Shultz

3)

Oct 24, 1945

Letter from Willie Helm, addressed to Mr. and Mrs. Julius Helm and Ray and Larry

533 Boulevard Way, Piedmont, Calif.

Authorities ordered all foreigners to clear out of Honmoku and Bluff. Most went to Hakone and Karuizawa orders came March 1944.

Willie’s family went to Karuizawa after having taken most of the clothing and some old furniture to Karuizawa. The good furniture as well as baby grand, phonograph, Frigidaire, washing machine, sun lamp, were placed in go-downs [warehouses] in the settlement no. 90. Which was burned down.

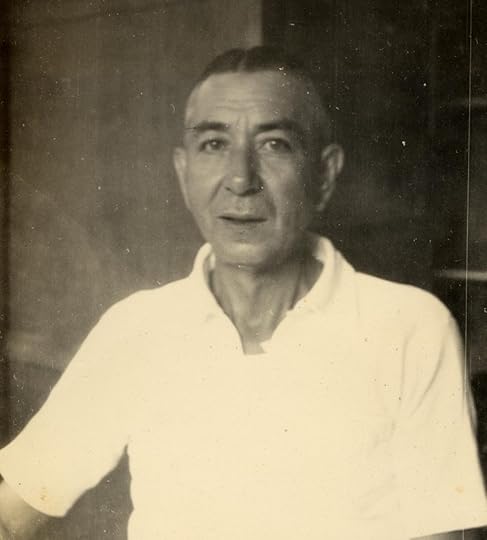

Willie Helm Born: Yokohama 1891; Died: Germany 1951

Willie Helm Born: Yokohama 1891; Died: Germany 1951Agnes, Veronica and Richard were in Karuizawa and still there.

Willie lived half time in Karuizawa and half time with Bud.

Bud purchased 804 [Julius’s house?] with all contents. We thought it a good idea instead of any Nip getting it. But now it’s no use as all burnt out together with contents.

In the excitement, Bud only rescued his tuxedo, swallow tail suit, hard form shirts, still with New York laundry labels and 85 cents alarm clock. All the rest of his stuff is gone.

Butter is now 100 to 150 yen a pound but impossible to get. Potatoes 20- 30 yen a kwan. Rice 60- 80 yen a sho. Agnes still has kidney trouble.

After the fire, Willie moved to a room in helm house. On the morning of the 29th of May practically all of Daijinguyama went up in smoke up to former mis ross’s house. Same day all of Motomachi, Isezakicho, Honomku were gone.

What is left of Honmoku near our place, just a couple of Japanese houses, all our houses—Willie’s Gomei, Bernard-Bells houses broken up through bombs.

Although [Japanese]soldiers are back it’s impossible to get carpenters.

The Nips seem to be dazed that they lost the war—how long they will be like that we do not know—they ought to work since they have no food to eat but even if they had money what could they buy.

When 804 burned on the 29th, Bud shared Willie’s room in the Helm House. Everybody being very nervous before they left Willie’s place. Agnes and they were no more on speaking terms—Willie also got somewhat fed up—outside of these there were another two burnt out people put into the house. Four guests at one time for such a long period was too much. (E+L

[sisters Eloise and Louisa] were staying there during that time)

On the 24th of August Nip authorities gave orders for all people living in Helm House to clear out within 24 hours as the place had to be made for sleeping quarters for U.S. officers. Nips would not even allow Bud and Willie to stay there so had to find quarters.

Katchan lost all her stuff, went to the country and now came back two weeks ago and working for Walter—she has only one dress what she has on. Walters leg at last better, had been bad for over two years.

Bernards living in servants rooms of Barney’s place, old man now 92 years old they were interned up to the end of war. Total eyesight, 98 percent hearing gone but brains working normal and good appetite.

Would appreciate very much if you could do something if any way possible—victuals as well as money—Willie will repay when he can—nothing can be done from here. Would be nice if they could be brought to your town.

Three Gaijin Letters from Yokohama after Japan’s Surrender

As I began scanning documents I gathered for my book Yokohama Yankee, I came across three letters that I reference in my book, but that I thought some Hamakko might find interesting. All three were written by Yokohama residents soon after Japan’s surrender following WWII, and describe their experiences during the war. Not surprisingly, they all reference the devastating impact of American fire bombing of Japanese cities. And, in a way only letters can do, they capture very personal reflections on the hard times each of them experienced in the past and, in all but one case, a sense of optimism about the future.

A Marianist Brother’s Perspective: The first letter is by Xavier Bertrand, a French teacher at the Marianist school, St. Joseph College, whose student body drew largely from the expatriate community as well as from among mixed-race families. St. Joseph and its faculty of Brothers avoided the worst of the war by moving the school into the mountains, although many other Marianist schools in Japan suffered much worse fates.2) A Teenage Survivor: The second letter is from John Schultz who had been a classmate of my Uncle Ray at St. Joseph until the war began and ended the flow of money from his father in the United States. He was 15-years old the time, and lived with his single mother and sister. It is hard not to be moved by his story.

3) Playboy of the Eastern World: The third letter is from Willie Helm, my grandfather Julie’s youngest brother. He was always one to take risks and somehow always ended up okay. He took his inheritance early and invested it in failed ventures in the Japanese colony of Manchukuo, yet when he returned, his oldest sister took pity on him and left him with her fortune. Although his mother was Japanese, during World War I he went to war to protect German’s Chinese colony from the Japanese army. He suffered a head wound but survived and was sent to a prisoner of war camp. When World War II began, my American grandfather had to leave Japan for California, so Willie, a German, was put in charge of the family company, Helm Brothers. Willie made a great deal of money working with the German navy, which was based in Helm House. It is said he operated a lucrative black market out of the apartment building’s basement. But when U.S. forces arrived after the Japanese surrender, Willie’s luck had run out. His assets were frozen by U.S. occupation forces, and not long after he wrote the letter, he was deported to Germany. Before the trip, Willie put all his family jewelry and other valuables in the safekeeping of a German diplomat. The valuables were never returned.

A Marianist Brother’s Perspective: This letter was written by Brother Francis Xavier Bertrand of Japanese vice province of the Society of Mary, and a French teacher at St. Joseph College, a Marianist school established on the Bluff in Yokohama in 1901 and closed in 2000. The letter, delivered “through the kindness of Archbishop Spellman” of News York, was translated from the French and distributed to friends and former students of St. Joseph in the United States, including my grandparents, then in Piedmont, California, who copied it and passed it on to friends and relatives on October 9, 1945Park Hotel, Gora, Hakone Japan Sept 15, 1945

Dear Brother John Kessler,

Finally the World War has ended, and we are all still alive. Who would have believed it? We are profiting by the kindness of Archbishop Spellman, Archbishop of New York, who honored us today with one of his pleasant visits, and who took it upon himself to carry our correspondence to America. Mail in Japan is not functioning as yet for foreigners. (Mssr. Spellman gave us a gift of $250 and instructed Captain Cyril Curtis, an Australian, to buy us supplies. It was this Captain who flew the Archbishop here. Incidentally, he is one of our old boys. And now I am going to begin to relate a few of the vicissitudes of war we underwent.

St. Joseph College, established 1901

St. Joseph College, established 1901In the month of September,1943, the 29th, I believe, the police came to tell us that all the foreigners on the Bluff in Yokohama must evacuate. We immediately searched for a desirable and convenient place. We discussed for quite some time whether should move to the seashore or take up new quarters somewhere on the Tokyo plain. Finally we decided, after the New Year 1944, to live in the mountains. We were able to rent St. Joseph’s College for 12,000 yen a month. This allowed us to move into the hotel at in the Hakone mountains at the bottom of “Big Hell” [a hot spring resort.] We used thirty and a half trucks to transport the most necessary and important things to Gora. These trucks went irregularly from the 20th of February 1944 to the end of March. The first time I went along in a truck. I almost had an accident. The roads here, as you know, are very steep, and our truck didn’t use gas. It was one of those charcoal burners you no doubt remember. Well, the one I was on stopped and almost rolled into a ravine.

Finally, one after another, we all arrived for good on the 17th of March. Living here was very trying because in the month of March it was very cold, with much snow, and there was no furnace installed. As the hotel had been neglected during the war, the windows and doors didn’t close very well. By the followings winter we were able to install a stove In the study room and it was O.K. One of the best things about the hotel was the fact that there were warm baths of mineral water coming from one side of Big Hell(which you know.) Unfortunately, it is only from time to time that we have this warm mineral water.

Toward the end of April 1944, we started school with seven pupils. Now we have forty boys and girls. At the present I have 14 pupils taking music lessons, most of whom are girls. They are using three of our five pianos. I left one piano in Yokohama, taking a chance on it; the fifth was taken to Tokyo and fortunately was not burned. The little organ we had in the second parlor at Yokohama was sent to the Gyosei (Morning Star School) and was burned there.

At Tokyo, the building at the Morning Star School were not bombed, but four buildings caught fire and were burned. Fire from our neighbors spread to the large school constructed of reinforced concrete, then to the Brothers’ house then to the science building, and finally to the tailor shop, kitchen and refectory. We especially regret the loss of our rich and valuable library and the wonderful museum, which took go many years to develop.

At Kobe our school building was bombed and burned but our Brothers had already moved to the country. Father Fage(Benefactor and Affiliated Member of the Society) was caught in his burning church and trapped by falling debris. He was burned to death while trying to save the Blessed Sacrament. What a beautiful death for a missionary after having been at the post in Kobe for fifty years.

At Osaka the Meisei (Bright Star School) suffered great damage due to incendiary bombs. All was burned except the building constructed in re-enforced concrete.

At Nagasaki, the Kaisei (Star of the Sea School)suffered damages due to the atomic bomb, the new weapon which Hitler hoped to use to crush the allies.

Star School at Sapporo was spared as also our school at Yokohama. But our neighbor, The sisters, were burned out at Yokohama, Tokyo and Shizuoka. The third story of the main school building at Yokohama caught fire by accident, and that on Christmas Eve 1944. We still own our school in Yokohama and will come back if there are pupils. We will return there, soon, perhaps. In the meantime thieves have not scrupled to steal many things, among them curtains from the windows and the large drop on the stage in the auditorium. Today, two of our brothers , Bros. Crambach and Gessler, received an obedience to return to Yokohama to watch over St. Joseph College.

You did will to leave for America because the internees of your [American]concentration camp were moved to our old country house near Yamakita. They were not well treated especially towards the end. One man (Emery Jones) died of hunger. American fliers let fall 40 sacks of supplies for them. One sack went through the window of the old confession room.

Now you see, I am writing my old pupil and walking companion to return old favors and to acquaint you again with the French language. When are we going to take our next walk together. Here in the country near the Grand Fujiya Hotel it is very beautiful. The big shot of the American military authorities have taken over the Fujiya Hotel as their quarters. On the 6th of Sep5t we received our first visit from American soldiers and drank to their health. The next day they took many photographs and some movies of our Brothers and pupils for American papers. If you watch carefully you many see them. They also promised to send some to Dayton University. We are now 24 brothers. Bro. Gerome left here last spring to die in Tokyo of an ordinary sickness.

Bro. Bertrand.

2) Tales of a Mixed Race Teenage Survivor

Letter from John Schultz — Jan 8, 1946

Dear Ray[image error],

I thank you very much for your nice letter which I received it yesterday. I reached San Francisco on 18th of December last year. It was lucky for me that I have found two American Red Cross men on the ship. When the ship reached San Francisco, these two men brought me to the American Red Cross in the city. The lady in there was very kind to me. On the first day, I slept in the Y.M.C.A. But it is the first time for me in United States since 18 years that I don’t know where to go. I even don’t know how to go to the restaurant. So I did not eat anything on that day. The lady in the Red Cross worried [image error]about me and put me in the Buddhist Church in S.F. because there are lots of Japanese people, and I am used to it with Japanese character.

On the second day, I went to see Bro. Tribull. He was very glad when he saw me and at the same time he was laughing because she put the Catholic boy in the Buddhist Church.

At his place, I was told about your telephone number. So when I went back to Church, I have phoned you, but you were not there. I heard that you went to Jujitsu lessons. On the third day, I went to see him again and he introduced me to other brothers. I will tell you an interesting thing that those Japanese people in the Church don’t believe that Japan was really defeated. On the same day, at half past six, I took a train from Oakland and went to Corvallis, Oregon. It took me 21 hours. I met my father at Albany. He was very glad when he saw me. I went to my uncle’s house. I spent my Christmas at his house. After three days of staying in Corvallis,1 took a bus and came to Olympia. 0lympia is a small town, but it is very beautiful. Perhaps I can say that it is one of the most beautiful town I have ever seen since I came to United States. I used to live near the Capitol Bldg, but it was raining all day that I had no chance to go and see it. After three days I took a bus and came to Renton. First 1 got off at Seattle (my home town) and took another bus to

Renton. I am in my aunty,s house now. She is very kind to me. I am in here for ten days already. That means I have traveled three states in ten days. Even the circus cannot travel three states in ten days.

I am very glad to hear that you are attending to school. I have wasted three and half years of school, because when the war broke out, our source of money from America was cut off. Afterwards, Mr. Haegeli told me to come to school, so went, but two months after, school was closed because Bluff was in the fortified zone. After the school was closed, all the teachers went to Hakone and opened the school there, but the police did not permit me to go there.

When Japan declared war against America on 8th of December (7th in U.S.) I was only 15 years old, so the police did not say anything to me. But on the first and second day, I did not go out anywhere, because I was afraid of the police. 1 have gone to the school for a month after the war was started. After that, I went out to work in the typewriter company in [image error]Tokyo. They paid me only 15 yen ($1) per month. With that much money, I helped my mother.She was her very glad much when I sent so much with the money, but I helped her quite much with other thing, because I lived in Tokyo and ate the meals at the company.

The government and the people were very kind to me at the beginning of the war, because they were winning all the time. But when they were defeated at the Island of Guadal Canar (crossed 1) and lost the way to go to Australia, the government began to talk bad thing about America to the people, and they forbade to use the enemy people in the company. So ten months after, I was out of job and I came back home again. After that, my uncle used to give us little money, and we made the farm on the back of our house to raise the vegetables. The government even tell the people to give out all the Jazz records. Persons who did not give out these records were be punished. They said that they cannot fight against America when they are listening to the American music. After I was back from Tokyo, I was at home for about ten months. Afterward, Mr. Haegeli told me to come to school, so I went into 1st High School class from Sept 16, 1943. It was too difficult for me and Mr. Grosser taught the Algebra, which we have to learn in one year, he taught in two months, so I don’t even know the addition of the algebra. The school was closed on the 22nd of Dec 43, and all the foreigners have to move out from the Bluff. Honmoku was also the fortified zone. It was lucky for us that we were out of the zone. After the school was closed, the government made more strict law against the American people who was not interned. I was not permitted to go out from my house unless if it is not necessary. Even they don’t permit me to go out to the town to buy something. I was only allowed to go around my house and I could go as far as Sagiyama. I was not permitted to pass the tunnel and go to the other side of the town. Once, I went to the shore, secret,and on the way back home, I was caught by the police. He took me to the police station, and did not let me go out for half a day (I was not in the jail) That day, I don’t know how many slaps and kicks I got. After I came back home in the evening, I got sick, and I went into the bed for eight days. Then I came back home and sat down,that was the end for me. I could not even stand up on account of the kicks I got. It was 15th of February 1944. I will never forget this day. This is secret to everybody except you. Even Donker doesn’t know about this. After that, I was strictly guarded by the police, I have to write the diary and bring to the police station every week. I have done this till the date of the air raid. After that, what I can do was just stay home and help my mother. When the B29 begin to appear on the sky of Tokyo, most of the rich Japanese and all the foreigners except the enemy people had gone to the country. We could not go because we are enemies of Japan. That is why, on 29th of May 1945, we were burnt out. Donker Curtius , Mr. Mayes, Eddie Duer, Bryden, Gomes, and rest of other enemy people were also burnt out. The air laid began at nine o t clock in the morning, and finished at eleven o’clock. Two hours after, there is no more fire. At the same time, there is no more Yokohama left. [image error] used to say “Gone with the fire”for Yokohama, Americans dropped average of two bombs to every people of Yokohama (including small and big bombs) Believe it or not, but it was written in the Japanese newspaper. For me I got one extra[image error] bomb than other people, we got three of hundred pounds incendiary bombs into our house, I think you know how small my house was. The air-raid siren alarmed, when I was still in bed. That time, the planes are over our house already. Whenever they bomb Tokyo, they use to fly over our house. That is why, [image error] thought they are going to bomb Tokyo again. I was counting the planes in the bed. First line was with ten planes, but they did not drop any bombs. Second line was twenty planes. Third was thirty three, fourth was fifty two. And with the fifth line of hundred one planes they dropped the bombs around your house and Honmoku. I will not forget that noise, when the bombs are coming down from the sky, I cannot remember anything but, when the bombs came into my house, it made a big noise, and at the same time, what I can see was only the black smoke and the red flames of the fire. At this time, I got a burn on my hand and on my leg. It was the hottest and the coldest day I ever had in Yokohama. During the fire it was very hot and in the evening it was very cold, because I have no more house and clothing, I came out with on gray short pants and one [image error]pink sweater. I came out with no underwear, no underpants, no shoes and no socks. I was wondering what shall I do this winter when the war does not finish: but luckily the war is over and we won the war, so the army supplied me with the clothing. After the air-raid, I walked around my house, but I could not find my mother and sister. On the next day, I found my mother and sister’s body in the canal. Both suffocated to death by smoke. That day, I can’t even understand what the people are talking about, because I lost my mother and sister at once, word that I cannot forget was: the neighbor told me that mother and sister must be glad because they were killed by the American bombs. Two days after, I made a small shack with burnt tin and burnt wire. During the war time, we could not get any wires and nails; but after the airlaid you could find the tins, wires, and nails in everywhere, but they are all burnt ones; I used to live in this small shack for two and half months. On 15th of August, Japan surrendered and there was a negotiation that the US Army is going to come into Japan on the 26th of August. But they postponed till 28th because there was a typhoon, my shack was blown away. After that I used to live in the air laid shelter, because even I rebuild my shack, it [image error]was in the typhoon season. Three days after, I met one captain and I begin to work for him as an interpreter. I worked for him for three weeks. After that I was sent to Manila as a recovered personnel. I got on C54 from Atsugi and went to Manila via Okinawa. It took only ten hours. I was in 29th Replacement Depot (25 miles south of Manila) for four weeks I used to get better food and better treatment than the ordinary soldiers, because I was a recovered person, I was in there from October 2nd to October 30th. Afterwards, they sent me back to Japan, because I was civilian. They told me to go to Tokyo and go through the American Consulate in Yokohama. It was not my fault. It was the army who made the mistake. I have landed on Atsugi Airfield on 1st of November. I was in Tokyo for one month. During that time I went through the American Consulate, and the army put me on the ship called LT. S.S. Leonard Wood. They know that I am going to Seattle, and they put me on the ship that goes to San Francisco. But it was lucky for me, because the ship that goes to Seattle left Yokohama game time with us, and this ship went into the storm and lost all the lifeboats and one man.

I left Yokohama on the 4th of Dec. and reached San Francisco on 18th. Donker Curtius was interned three days after the war started. When I went to his house to see Bouldwin and Henry on the 8th of Dec., he was very intoxicated, because he was so discouraged by the outbreak of war. But he came back from the camp in the end of 1944, because he got sick. After he came back, they have moved to the back side of the Honmoku middle school. During the war time, I did not visit him so many times, because we were both enemies of Japan. Maybe I didn’t even visit him ten times, after the war was started.

I myself was told by the police not to visit the enemy people of Japan. On 29th of May, he was also burnt out. His house was burnt and his neighbors were not burnt. Afterwards they have rent the room from the neighbor and they are still there. Since Jimmy and Joyce were Japanese citizen, they could go any place they want to go. His grandfather was interned when the war was started, but he came back home three weeks after, because he was too old. He died in 1942. After the school was closed, Jimmy was just playing around the house, but Joyce was attending to Koran Gakko till the date of air raid, Jimmy is still small but Joyce is very big now. She is only little bit smaller than I. On 29 of May, his house was also burnt down, and they are living in the air-raid shelter now. I saw both of them once after I came back from Manila. His father is working as an interpreter now. When 11th Airborne Division occupied Sendai, he also went to Sendai. He is still there now.

Japan had a short of food during the war time. I think you know that. The time when you left Japan, the sugar and the rice was already rationed. After the outbreak of war, the food condition became worse and worse. In 1942, even the fish and the vegetables became rationed. In the same year, the fuel like charcoal and wood became rationed. In 1943, they used to give us half of the food what we need. In 1945, we could not get anything. The fishermen does not go out to fish, because they were afraid of the submarine and the sea planes. After the air raid, the food what they gave me for 20 days was just enough for me for only four days. They used to give a little bit of rice and hard soy beans and some shoyu. They gave me only 2 sen worth of salt per month. Vegetables once in about three weeks; frozen fish, once in about three months. I did not see the meat for three years.After Saipan was taken by the Americans, we could not get any sugar. In 1945, eight pounds of sugar cost 5000 yen in the black market. So I got sick after U.S. soldiers came into Japan, because I took too much sweet at once. When the army came into Japan, I was weight only 85 lbs., (only three times as heavier as a turkey) and I am 135 lbs now. The day when I went to Manila, I weighed 110 lbs. That means I have gained 50 lbs in 4 months.

In Washington, we have “liquid sunshine” every day. These few days, we have frost in the morning, but usually it is very warm. (Much warmer than Yokohama) If it is fair weather, we could see Mt Rainier from our house.

I’ll close here, otherwise there will be no limit. Please give my best regards to your parents and Larry. Shultz

3) Playboy of the Eastern World

Oct 24, 1945

Letter from Willie Helm, addressed to Mr. and Mrs. Julius Helm and Ray and Larry

533 Boulevard Way, Piedmont, Calif.

Willie Helm at center, a playboy and black sheep of the family.

Willie Helm at center, a playboy and black sheep of the family.Authorities ordered all foreigners to clear out of Honmoku and Bluff. Most went to Hakone and Karuizawa orders came March 1944.

Willie’s family went to Karuizawa after having taken most of the clothing and some old furniture to Karuizawa. The good furniture as well as baby grand, phonograph, Frigidaire, washing machine, sun lamp, were placed in go-downs [warehouses] in the settlement no. 90. Which was burned down.

Agnes, Veronica and Richard were in Karuizawa and still there.

Willie lived half time in Karuizawa and half time with Bud.

Bud purchased 804 [Julius’s house?] with all contents. We thought it a good idea instead of any Nip getting it. But now it’s no use as all burnt out together with contents.

In the excitement, Bud only rescued his tuxedo, swallow tail suit, hard form shirts, still with New York laundry labels and 85 cents alarm clock. All the rest of his stuff is gone.

Butter is now 100 to 150 yen a pound but impossible to get. Potatoes 20- 30 yen a kwan. Rice 60- 80 yen a sho. Agnes still has kidney trouble.

After the fire, Willie moved to a room in helm house. On the morning of the 29th of May practically all of Daijinguyama went up in smoke up to former mis ross’s house. Same day all of Motomachi, Isezakicho, Honomku were gone.

What is left of Honmoku near our place, just a couple of Japanese houses, all our houses—Willie’s Gomei, Bernard-Bells houses broken up through bombs.

Although [Japanese]soldiers are back it’s impossible to get carpenters.

The Nips seem to be dazed that they lost the war—how long they will be like that we do not know—they ought to work since they have no food to eat but even if they had money what could they buy.

When 804 burned on the 29th, Bud shared Willie’s room in the Helm House. Everybody being very nervous before they left Willie’s place. Agnes and they were no more on speaking terms—Willie also got somewhat fed up—outside of these there were another two burnt out people put into the house. Four guests at one time for such a long period was too much. (E+L

[sisters Eloise and Louisa] were staying there during that time)

On the 24th of August Nip authorities gave orders for all people living in Helm House to clear out within 24 hours as the place had to be made for sleeping quarters for U.S. officers. Nips would not even allow Bud and Willie to stay there so had to find quarters.

Katchan lost all her stuff, went to the country and now came back two weeks ago and working for Walter—she has only one dress what she has on. Walters leg at last better, had been bad for over two years.

Bernards living in servants rooms of Barney’s place, old man now 92 years old they were interned up to the end of war. Total eyesight, 98 percent hearing gone but brains working normal and good appetite.

Would appreciate very much if you could do something if any way possible—victuals as well as money—Willie will repay when he can—nothing can be done from here. Would be nice if they could be brought to your town.

December 7, 2022

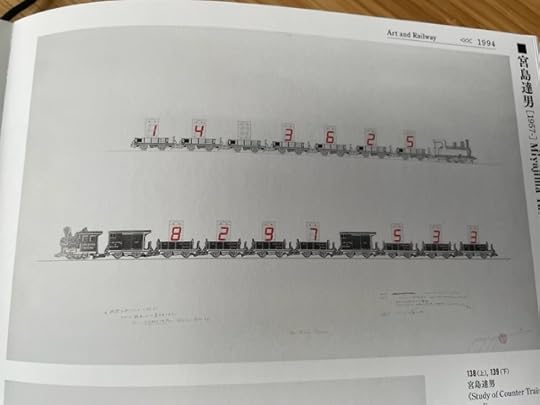

Art and Railway: Celebrating the150-year history of railroads in Japan

The Black Diamond and the Sunflower

The Black Diamond and the SunflowerI’ve never been much of a fan for art exhibits in Japan. Too often they throw together a bunch of stuff without any rhyme or reason. But this exhibit at the Tokyo Station Gallery uses woodblock prints, oil paintings, photographs, textiles and even an image of a bathtub installation to offer deep insights into the myriad of ways in which railroads have had a deep and enduring impact on Japanese culture, labor practices, social behavior and urban developments. Here are just a few examples.

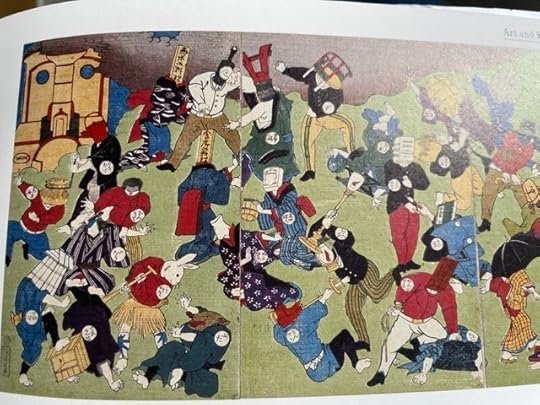

The Rise and Fall of a New Age by Shosai Ikkei

The Rise and Fall of a New Age by Shosai IkkeiThis image doesn’t contain any images of trains, but it established the context for the train’s introduction, by illustrating the many areas in which the arrival of westerners posed a challenge to Japanese tradition. The people in western dress are shown beating up on people in traditional dress. The heads represent the challenges. On the bottom right is brick, and to the left is a lamp. Further to the left is a rabbit, which is beating on a wild boar.

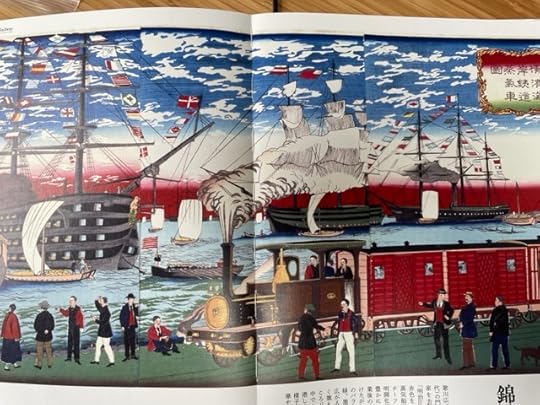

Steam locomotive in transit by Utagawa Yoshitora

Steam locomotive in transit by Utagawa YoshitoraThis is one of many classic woodblock prints that show “black ships,” which brought the westerners to Japan, and the trains hey introduced.

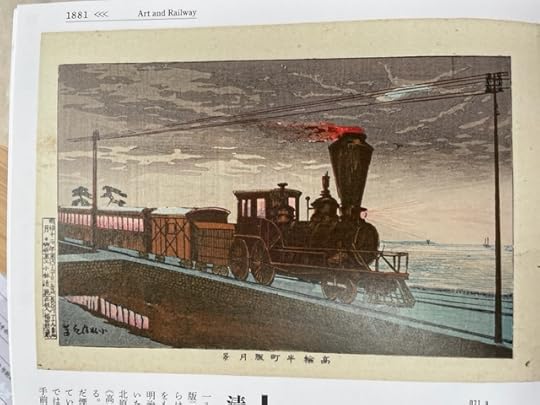

View of Takanawa Ushimachi beneath ashrouded moon.

View of Takanawa Ushimachi beneath ashrouded moon. This woodblock print by Kobayashi Kiyochika is from 1879. It’s only been seven years since the first train traveled from Yokohama to Shimbashi, but already the train, while fierce with flames coming from its locomative already seems somehow romantic and very much a part of the Japanese landscape.

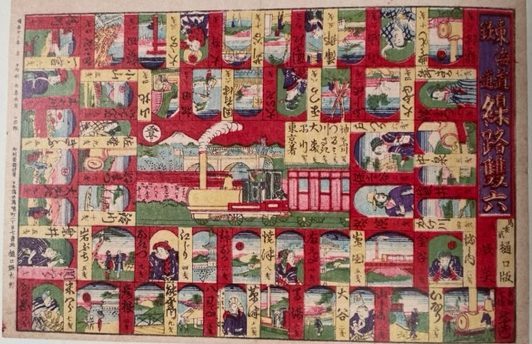

Tokaido Railway Board Game

Tokaido Railway Board GameRail lines are being laid at a furious pace along the Tokaido, long a traditional route to walk between Kyoto and Tokyo. In this traditional board game image created in 1889, each box represents a train station on the Tokaido Railway.

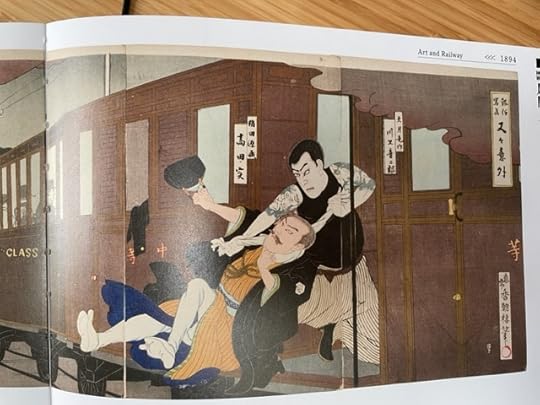

Murder on the orient express

Murder on the orient expressYou know trains have become a part of every day life when an image comes out illustrating a murder that took place on a trains, as was this 1994 image by Utagawa Kunisada III.

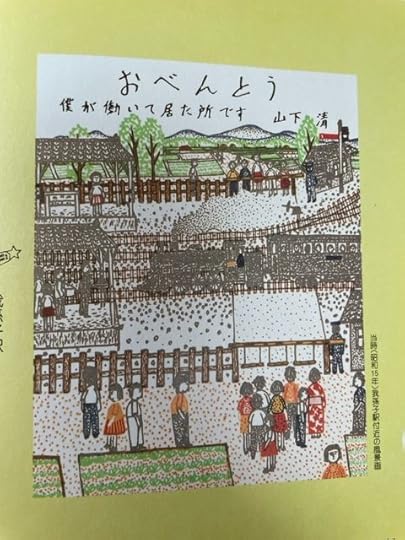

By 1940, the railroads are deeply imbedded in Japanese society and Japan is making its own contribution to train travel: bento boxes that include regional specialties. This is the light hearted side of the Japan experience, but there are many more dark images representing labor strife during the early 1930s. Their are designs for the special train cars built for occupation authorities after the war[

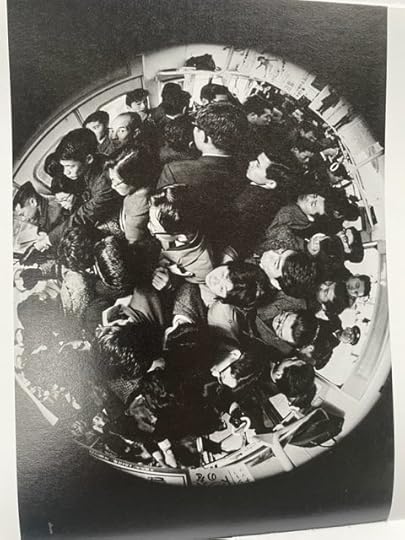

To many westerners, the image we have of Japan today are the faceless crowds best represented by images of people pouring into train stations. It sometimes feels as if that image of blank, inscrutable faces says something about the culture. But it’s easy to forget that this image, is to a great extent, a product of Japanese railways, not something that was part of traditional Japan. When you are crushed in a train, you need to put on that mask to hide yourself.

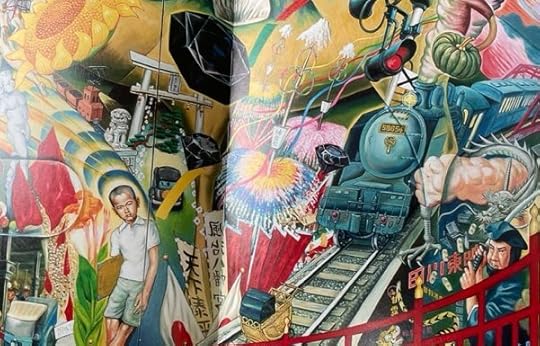

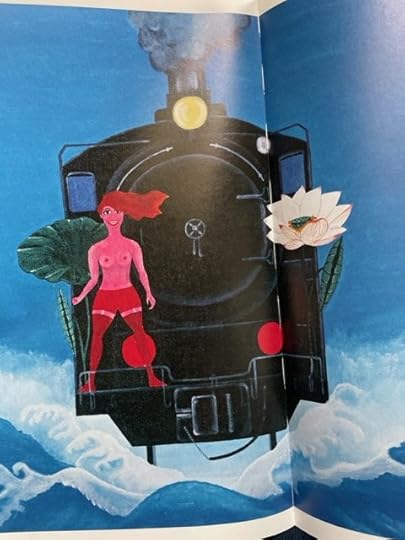

A comparison of Eros and Thanatos or “Aesthetics of the End” by Yokoo Tadanori 1966

A comparison of Eros and Thanatos or “Aesthetics of the End” by Yokoo Tadanori 1966Of course there are flights of fancy and other paintings that are Daliesque

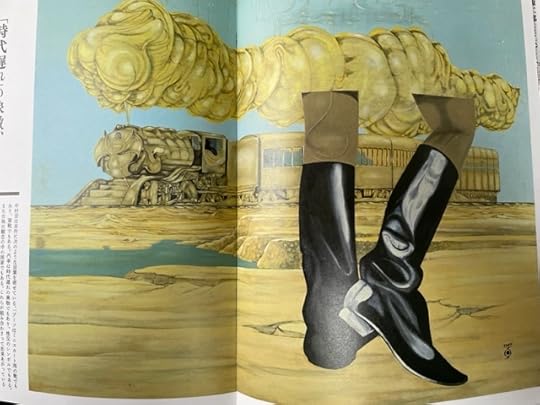

Trains as a metaphor for life moving in a single direction.

Trains as a metaphor for life moving in a single direction.

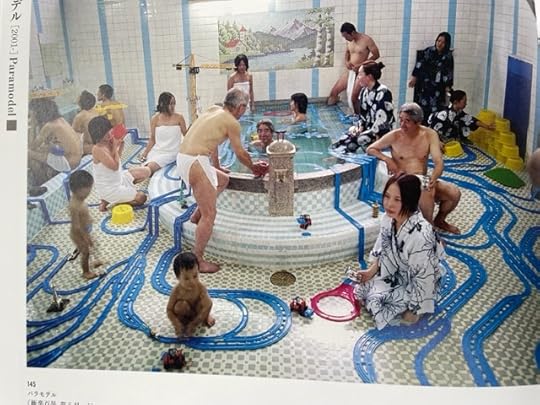

And then installations like this in 2007 that you just have to think about. There is just so much to love, think about and appreciate in this exhibit. Don’t miss it. It closes on January 9th.

And then installations like this in 2007 that you just have to think about. There is just so much to love, think about and appreciate in this exhibit. Don’t miss it. It closes on January 9th.

June 3, 2022

The Binswangers, Freud and my Jewish Ancestors

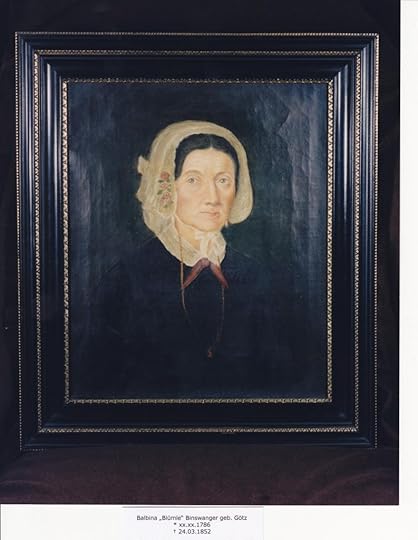

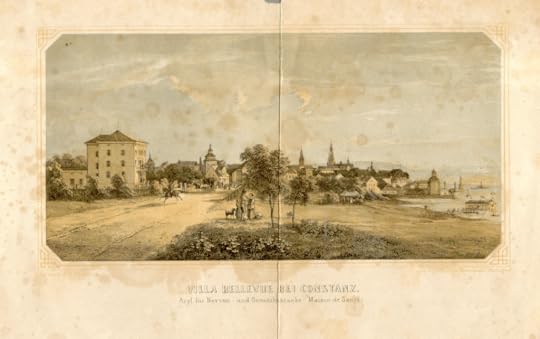

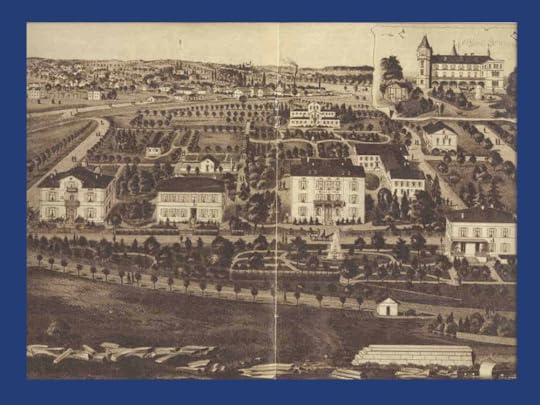

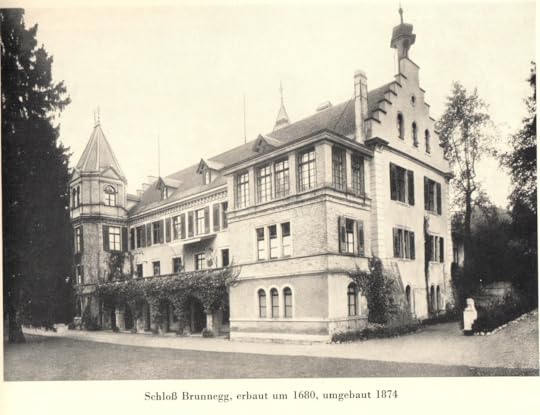

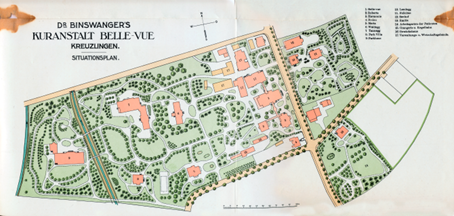

In 2016, I gathered in Kreuzlingen with some 120 relatives were from Britain, South Africa, Germany, Switzerland, the United States and Canada. We were there to hear about the history of the Swiss Binswangers, a family that for four generations operated the Bellevue Sanatorium that treated patients who could afford psychiatric treatment in a lavish environment.

Next week, I will visit Augsburg, Germany for a reunion not just of the Swiss Binswangers, who converted to Christianity about 1850, but of all the descendants of Moses Binswanger, our common ancestor.

In doing so, I came across an illustrated history of the Binswangers by Richard Binswanger that I will borrow heavily to talk about the history of this interesting family. I will also draw from extensive research provided by Andreas Binswanger, the family historian.

Moses Binswanger was a Jewish peddlar who was born in 1783 in Huerben, not far from Munich. His grandparents lived in Binswangen, 33 miles away, and they probably took the name of that village as their last name when they moved to Osterberg and then Huerben. Jews had lived in Huerben since 1518 when they had been driven out of Donauwoerth, where they had controlled much of the trade in salt.

In 1670, Count Maximilian of Liechtenstein asked the emperor for permission to expels the Jews from Huerben but his request was denied, and five years later the count allowed the construction of a synagogue and a house for the rabbi. Ritual slaughter of animals was allowed, and for each cow or large animal slaughtered, its tongue had to be delivered to the manor, although in 1717 a fee of 15 Kreutzer could be substituted for the tongue. For small animals, a fee of 5 Kreutzer was charged.

Moses married Bluemle Goetz from the village of Fischach, about 14 miles away. It was a town where Jews had lived since about 1570. The Jews of Fisbach were moneylenders and also traded horses and cattle. Farmers in the area today still tell stories of how the Jews were the most honest people. During the 30-years-war, which lasted until 1648, the Jews fled to Augsburg. Although they were allowed to return to Fisbach after the war, they were told they could only live in five houses. They moved in, and expanded each house until, by 1743, there were 113 people living in those five houses. Neighbors complain constantly and finally, in 1802, they were allowed to build more housing.

A Jewish synagogue was built in 1739, and a cemetery in 1774. Today, one memorial carries the inscription: “Dedicated to the victims of the racial persecution 1933-1945. In Memory of the Dead: An Admonishment for the Living.”

After Moses and Blumle married, they moved to Osterberg where Moses worked as a peddler selling textiles and glass door-to-door. He traveled to villages as much as 45 miles away, most likely on foot.