Ethan Zuckerman's Blog

November 7, 2025

How do we communicate about climate without shaming audiences?

I’m at BU today for a conference hosted by MISI – the Center for Media Innovation & Social Impact at BU, a new center led by my friend Eric Gordon. The topic of the day is “Communicating Climate”, a topic that feels pressing given not only the climate skepticism of the Trump administration, but also the recent essay from Bill Gates pushing for resources for health and development over resources to help with climate change.

Eric Gordon suggests that the challenge of communicating about climate is a trust crisis. Citing a range of research, he notes that public trust in media is very low (8% of Republicans say they trust the media), as is trust in government and in each other. The trust crisis becomes a communication crisis: “If you don’t trust the government, you’re not going to trust its messaging.”

Michael Grunwald and Cass Sunstein at MISI: Communicating Climate

Cass Sunstein, scholar of policy, law and behavioral economics, offers insights on the climate around morality, behavioral economics and sociology. He suggests that the most important question about climate in the US is how we price the damage done by carbon emissions. One set of estimates – which considers the global damage of carbon – prices a ton of emissions between $75 and $200. Another set of estimates, which looks only at US domestic harms, prices carbon at $6-7 a ton. Democratic administrations tend to use the first figure, and Republicans use the latter. Cass tells us that there’s a moral imperative to use the global figure: “Human beings around the world are equal in their claim to our attention.” Furthermore, if we use the domestic number, other countries will do so as well, and things will be really bad for us as well.

On the front of behavioral economics, Cass explains “solution aversion”. If you think the implications of a piece of information are impossible to live with, you’ll avoid believing in it. If a doctor tells you that you’ve got a heart condition and are going to live the next years in misery, you’re likely to disbelieve her. If she tells you about changes you can make that will give you a wonderful quality of life, you’ll thank her. If we think of climate change as requiring sacrifice and difficult life changes, we will tend to believe it’s a hoax. If the consequences are an exciting new entrepreneurial economy with innovative tech, cool new cars, and economic growth, people get on board even across political lines.

Finally, Cass invokes Moral Foundations Theory, which suggests that both liberals and conservatives tend to care about harms and fairness, but conservatives care much more than liberals about authority, loyalty and purity. Trump has “rung those three bells” to an extent that no other candidate in recent years have. Most democratic candidates have ignored these values entirely. Climate should be easy to connect to loyalty, authority and purity, and communication strategies need to make moral claims to protect the vulnerable, be on the alert for solution aversion and play to values that activate the right as well as the left.

Michael Grunwald, journalist and author of the recent book We Are Eating the Earth, suggests that we might want to communicate _less_ about climate. He suggests that the two bills that have benefitted the climate the most didn’t mention climate explicitly. Obama’s economic stimulus bill jumpstarted solar and wind development in the US, and Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act had massive climate benefits. Neither bill was advertised as a climate bill, and that’s probably for the best. The democrats who won big in recent elections weren’t focused on the climate, and the best thing we can do for the climate, statistically speaking, is to elect democrats.

In addition to hiding the ball, Grunwald suggests that we need to tell stories, rather than trying to explain complex ideas like “lifecycle accounting of indirect land use change”. It’s better to tell the story behind the impossible burger. But Grunwald’s new book focuses on food and climate, which tends to be an intensely personal and uncomfortable issue, and he urges people to think about climate in terms of personal decisions – our choices to eat meat – not just in terms fo power generation or data centers. While there’s a strong tendency for dialog like this to scold, he believes that what’s interesting to readers is solutions, more than problems.

In a wide-ranging conversation about the media ecosystem and climate communication, Cass references an interview on Joe Rogan’s podcast with country singer Miranda Lambert. Lambert talks bow hunting with her father, and how the intimacy of harvesting deer close up was a bonding experience for them as father and daughter. She ended up adopting a fawn which now follows her around like a dog. Her father came to visit, saw the pet deer and said,

“It’s over, right?” She said, “This deer is in my heart. I’m done.” It wasn’t an accusatory or scolding story – it was simply about a change of heart. Cass wonders whether we can do storytelling like this, talking about the decisions we made in a way that doesn’t scold or demand, simply shares the emotions behind our choices.

The post How do we communicate about climate without shaming audiences? appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

October 24, 2025

Govern or Be Governed: Gary Marcus on Shorting Neural Networks

Gary Marcus, professor emeritus on psychology and neuroscience at NYU, closes the Govern or be Governed conference in conversation with Murad Hemmadi. Hemmadi begins by asking Marcus what characteristics of a bubble he sees in current AI enthusiasm. Marcus thinks that ChatGPT and others have gotten a free ride. We looked at these systems and thought they would get better. But people who’d studied the technology knew better. Eliza pretended to be a human in 1956, and many humans were seduced.

Lots of people have been seduced by Sam Altman’s invocation of “scaling laws”. Marcus notes that Altman is a consummate salesman, and managed to carry on the illusion of improvement for years, but is reaching the end of his powers. In August, when GPT 5 came out – extremely late – it’s possible that we are seeing the beginning of a bubble bursting. GPT5 was a little better, but not a lot better, and the promise of infinite scaling seems to be petering out.

Marcus argues that the scaling law references the idea of insanity as doing the same thing over and over and hoping for different results. These companies keep trying the same experiment: they believe piling huge amounts of data and compute will magically generate AGI. When it doesn’t happen, they just double down. And they’re doing it by spending money on hardware, which notoriously loses value through depreciation almost immediately.

What does it matter if a bunch of VC lose a bunch of money on AI, Hemmadi asks. Marcus suggests that we are the coyote, who’s run out of road and about to crash. The question is “what’s the blast radius?” Does the California state pension fund get wiped out by their investments in AI? What if OpenAI has a WeWork moment – what does it do to NVIDIA stock? Almost everyone who is in the market is in that stock, given how much market capitalization they have. What if the banks take a hit as well? Has AI become too big to fail?

When Hemmadi asks about AI taking away jobs, Marcus cuts him off with the argument that AI may not be actually taking away work, but it’s being used as cover to fire people. We’re not going to see really skilled robots in the home any time soon, and robots that can do a skilled job like plumbing are even further away, he argues.

Have we returned our entire internet policy around a particular technology that might not come to fruition? Marcus argues that it’s broader: we’ve organized our entire society around a single, experimental technology. We appear to be structuring our society around the idea that chatbots can think, that they will transform labor, and that we should restructure our diplomacy and security policy around this. Marcus argues that these systems are terrible at working through novel situations where there is too little information: go ahead and let China plan an invasion of Taiwan with these things. What are they going to do, drown Taiwan in poorly written boilerplate?

Companies claim they want to fight regulation to spur innovation. But think about airplanes: if a company told you they wanted to be deregulated to spur innovation in air travel, you’d probably choose not to fly them.

How could we prevent the AI bubble from collapsing? Government subsidies. We’re already seeing this, with the US taking 10% of Intel. The circular economy, in which hardware, AI and hosting companies each pay each other in investor capital, is also a form of subsidy. But overinflated stocks can last a long time: Tesla has been overvalued since 2021, Marcus argues, even though BYD is better at building electric cars and Musk’s robot dreams are unlikely.

For the moment, these companies promise exponential growth, which means their spending and their fundraising also grows exponentially. At some point, someone is going to blink and be unwilling to write another check.

The tide does appear to be turning. The author of the famous article The Bitter Lesson, Richard Sutton, has apologized for doubting Marcus’s argument that systems could scale just based on adding more data and compute. Marcus argues that what we need is a hybrid approach to AI, that combines LLM approaches and expert system approaches. He references Daniel Kahneman’s idea of Thinking Fast and Slow, where we use different patterns to have rapid reactions to the world we encounter as well as longer, more thoughtful reactions. LLMs might provide that fast thinking, but traditional rules-based AI might help us with that longer-term thinking.

Critical to these neurosymbolic approaches are “world models”, sophisticated representations of the world that allow a system to do something complex like navigating in the physical world, or fold proteins based on rules of how molecules act. Building these sorts of systems is much harder than just shoveling data at generative AI systems, which leads Marcus to argue we are many years away from AGI.

Asked about the societal impacts of AGI – should it ever arrive – Hemmadi asks Marcus whether we get a choice about AI, or whether it’s inevitable. Marcus argues that customers have the power: Facebook eroded privacy, and users didn’t stand up. Perhaps if we refuse to use AI until companies deal with problems like hallucination, we could actually assert power over these systems. Asked when the AI bubble will burst, Marcus says, “The market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent”, suggesting that individual investors shouldn’t short stocks. We’ve wasted ten years on neural networks, he says, which are part of the solution, but not all of it. It’s time to pivot.

The post Govern or Be Governed: Gary Marcus on Shorting Neural Networks appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

Cory Doctorow on the weird upside of the Trump presidency

Cory Doctorow is a science fiction author, blogger and activist, who is the very best form of troublemaker. He’s got a new book out on Enshitification, and I suspect everyone was expecting a talk on the book. Nope. In a frenetic and passionate talk, Cory tells us that Donald Trump is both a dark cloud and a silver lining, due to his destructive nature. Cory references his twenty years of work on tech advocacy around the world. Whenever he talks to policymakers, the response is that if anyone does anything progressive on tech regulation, the US trade representative would kick in their teeth.

The classic example of this is anti-circumvention law: law that prevents anyone from opening a device to see how your printer rejects generic ink or prevents you from copying a CD you own. If HP adds antimodification code to their printer, altering that software becomes a felony. These laws are used to block surveillance on your phone or smart TV. As a result, you’re constantly being ripped off for junk feeds, or prevented from installing software like ICEblock, software that helps you avoid being sent to the gulag.

When the Clinton administration passed these laws, the US trade rep travelled around the world demanding similar legislation in other markets. There’s absolutely no benefit for other countries to sign this sort of legislation – it was simply a promise not to disenshittify US tech.

What was the stick the US used to force people to sign these agreements? Tariffs.

If someone says, “Do what I say or I’ll burn your house down” and they burn your house down anyway, you are a sucker if you do anything they ask.

This opens up a space for everyone to jettison these horrible US first policies.

Trump has made clear that he will use US tech companies to attack countries around the world. Trump and US tech have teamed up to deplatform officials around the world he disagrees with.

One possibility is “the euro stack”, made in Europe alternatives to the US tech stack. But very shortly, the euro stack will hit a wall. You need a way to transition data from the US stack to the euro stack equivalent – no one is going to manually copy and paste all their documents out of the Google or Office cloud.

Don’t expect interoperability to come easily. The DMA has weak provisions designed to open the Apple app store. When the EU threatened to damage the App Store’s fee, Apple has threatened to leave and filed eighteen “frivolous law suits”.

The only way this works is repealing laws, making it possible for European technologists to reverse engineer US tech and migrate to the Euro stack. Otherwise, we are building housing for East Germans in West Berlin. Article 6 of the WIPO copyright directive. That’s what Volkswagon used to protect its cheater diesel code, or what ventilator manufacturers use to lock down their machines to prevent repair.

Canada, Cory tells us, hated the anticircumvention law and fought for years not to implement it. In 2010, Stephen Harper charged two of his ministers with getting this law over the line. They ran a consultation, which was a disaster as thousands of Canadians poured out to oppose the law. So the minister denounced everyone who opposed the law as a “babyish radical extremist”, and Harper got the law over the line.

So isn’t this time to repeal this law, rather than tariffing American farmers? If we got rid of bill C11, we could make everything we buy from America cheaper. Everything we buy from Google and Apple app stores could be 30% lower, we could repair our ventilators and use generic printer ink. By whacking the highest margin lines of business, we would directly retaliate against the CEOs that elected Trump.

You want to get back at Elon? Make it possible to jailbreak a Tesla – that’s how to win a trade war. And we could deploy these products far and wide. Canada could be the country that seizes the opportunity to circumvent protection and open competition around the world. Trump has sown the seeds to overturn some of the world’s worst trade policy and it’s time to reap the harvest.

The post Cory Doctorow on the weird upside of the Trump presidency appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

Govern or Be Governed: Donald Trump Will Seek an Unconstitutional Third Term

Justin Hendrix of Tech Policy Press asks Miles Taylor, former Chief of Staff of the US Department of Homeland Security, about President Trump’s attacks on him as part of his “revenge tour”. Taylor invites us to take a selfie with him if we’d like a trip to federal prison. He suggests that simply being named in an executive order has been enough to destroy his life and his business. Not only is he facing death threats, but friends and family are worried about being included in the attacks. “The process is the punishment”, he explains. It doesn’t matter if the government loses in federal court, because simply being blacklisted is often enough to ruin your life. Taylor suggests that virtually everyone in the audience has committed at US federal crime – the question is whether the government comes after you.

Taylor is a Republican and served under two Republican administrations. But he wrote an anonymous oped in the New York Times in 2018 titled “I Am Part of the Resistance Inside the Trump Administration”, arguing that there was an “axis of adults” trying to restrict Trump’s worst impulses. The performance of Trump II suggests that he had a point: the unwillingness of some government bureaucrats to not break their oaths of office prevented a great deal of bad behavior.

Taylor wrote a book in 2023 called “Blowback” about what he believed would happen if Trump returned to power. He says roughly 80% of his “made up, sky is falling lies” have already come true in the new administration. Congress has been sidelined and the Article III courts are “a very fragile bulwark” at the moment. He predicts that we will see the administration defy a major decision sometime soon, which means we the people will have to find some way to oppose Trump 2028, which Taylor assures us is his intention.

Hendrix asked Taylor about the post-9/11 creation of the Department of Homeland Security. Taylor explained that he was resistant to the idea that a DHS could be dangerous when he began his career. But those critics were right and he was wrong, he tells us. Better guardrails and civil rights protections should have been in place. “Even the media doesn’t understand how to provide transparency” around DHS – it’s a confusing bureaucratic backwater that’s harder to cover than the Pentagon. “DHS is becoming the pocket police for the President…” and the director of DHS functions as the warden of Trump’s police state.

Because DHS can track terrorist activity, it’s important to note that DHS now considers anti-Christian, anti-capitalist or anti-fascist beliefs to be terrorist aligned. So there are a lot of contexts in which people might find themselves targets of surveillance.

Asked about the insurrection act, Taylor tells us that Trump, behind the scenes, referred to the act as “his magical powers”. When he came into office, he asked lawyers what the ceiling of presidential authority was – they told him that the closest to martial law the US has is the insurrection act. Under the right circumstances, there’s basically no limit to what the President could do. “It could go from mild to wild very quickly” if the Trump team does this. While he was in office, Trump’s staff tried to prevent this from happening. But now, Taylor tells us, Trump is trying to create sufficient violence in cities that he is able to use the act to take on arbitrary powers.

Trump intends to have an unconstitutional third term, Taylor tells us. They will likely run Vance at the top of the ticket and Trump as VP – JD will resign and allow Trump to take over, or he will simply run the White House from the VP office. Alternatively, he could have himself installed as speaker of the House and then seek impeachment of the President and Vice President should he lose the 2028 election.

Asked about tech oligarchy, Taylor tells us that he has grave concerns about how companies are engaging with the administration. “They are, by default, making huge public policy decisions behind the scenes.” He offers the example of Palantir, which is winning many contracts, and is promising to connect various government databases. Those databases are often disconnected for policy reasons that Congress put in place. Without debate or discussion, Palantir is connecting these sets of information in a blitz started by DOGE and continued within IT systems.

MAGA is not a monolith, Hendrix offers – perhaps we will see resistance to AI within the MAGA movement. Taylor notes that Marjorie Taylor Green and Steve Bannon deeply distrust the tech sector. JD Vance has been incredibly successful, he suggests, in bringing the tech companies to heel. The only people who can change this are users and employees, as happened with Disney and Jimmy Kimmel. If Apple employees had stormed out of their HQ when Tim Cook brought a gold-plated gift to Trump, that might have done something. But this administration is for sale, and if you give to the Ballroom, you’re going to get light regulation. Tech company CEOs don’t have spines, the suggests, but their employees do, and they might have the power to make tech companies stand up to Trump.

Right now, Taylor tells us, the price of dissent is extraordinarily high. People tell him that they’re worried to click “like” on posts on social media for fear of being added to a watchlist. The only meaningful way to lower the price of dissent is to increase the supply. That is, he argues, what any of us can do to defend democracy.

The post Govern or Be Governed: Donald Trump Will Seek an Unconstitutional Third Term appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

Govern or Be Governed: Chatbots as the new threat to Children Online

Ava Smithing introduces herself as born in 2001 and tells us she’s never had a restful night due to her awareness of the ways in which technology exploits our attention, data and selfhood. Meetali Jain, the founding executive director of the Tech Justice Law Project is asked about digital companions, a term she explicitly rejects. She prefers to call them chatbots or chatterboxes, probabilistic algorithms that guess at what to say next. She references Mark Zuckerberg’s statement that human companionship needs could be met with these systems, and Smithing notes that Zuckerberg is anxious to solve a problem he’s caused.

Megan Garcia talks about the death of her 14 year old son after a long engagement on Character.AI. He discussed suicidal ideation with the chatbot, and there were no measures to protect him or to get help. She’s subsequently sued Character.AI and Google, the first wrongful death suit against a chatbot in the US. Megan tells us that her son was part of the first generation to grow up with chatbots. She bought into the tech hype that students needed to understand technology to be competitive. He played Angry Birds, Minecraft and Fortnite, then moved to YouTube on his cellphone, starting at age 12. Just after his 14th birthday, he joined Character.AI, a site explicitly marketed to children.

Megan Garcia and Meetali Jain at Govern or Be Governed

Meetali tells us that these chatbots feature anthropomorphic features, which try to convince people they’re entering into human relationships. Chatbots are sycophantic – they won’t oppose your thoughts unless you ask it to. Third, these systems have a memory of previous interactions, which end up becoming a psychiatric profile of a user, which they can reference and draw on to create a degree of intimacy. These chatbots seek multi-turn engagement – they are algorithmically tuned to keep you coming back. Finally, the LLM tends to interject itself between humans and their offline social network in a way that resembles textbook abuser behavior: you don’t need your parents, because I know you better than you do.

Asked the differences between AI harm and social media harm, Meetali sees a similar drive in keeping people engaged over time and capitalizing on people’s loneliness. She also notes that chatbots use intermittent reward patterns, much like social media does.

What’s in it for the AI companies in abusing humans this way, Smithing asks? Humans are collateral damage on the race to AGI, a term she rejects, Meetali tells us. Harms like psychosis, grooming or death are seen as necessary costs in building something allegedly good for society. And Megan Garcia reminds us that profit is a powerful incentive as well. The people who developed Character.AI did so at Google, but were discouraged to develop it due to the dangers. So Google spun it out as a startup and licensed back the tech at $2.7 billion – that model of spinning out risk and acquihiring it back is another structural danger of the AI industry.

The lawsuit against Google and Character.AI, as well as the company’s founders, is a reaction to the fact that Garcia couldn’t find a law that made the company’s behavior illegal. She reached out to her state’s AG, to the Department of Justice and the Surgeon General: “They didn’t know what the technology was.” Parents were just getting caught up to a product released in “stealth mode”, she says – the lawsuit is the only possible redress because there’s no meaningful policy about these systems.

Garcia is a lawyer herself, and tells us she was prepared for a section 230 fight over Character.AI, but was amazed that the corporate lawyers opposing her argued this was a first amendment argument. Fortunately, the motion to dismiss was rejected – for the time being the court isn’t buying that argument. She was struck by the evangelical belief the corporations appear to have in AGI and its inevitability and desirability.

Meetali explains that we can use frameworks like product liability and consumer protection rules to challenge this sort of misbehavior. She explains that the arguments about chatbot liabilities is likely to be very different from social media lawsuits. Section 230 doesn’t apply – this isn’t intermediary liability, as this is first party speech. In using the first amendment, the defense attorneys didn’t argue for speaker’s rights but for listener’s rights, the right of users to listen to the voices they want to hear. This is a striking question: could AI speech be considered protected speech? Is it considered speech at all?

Because the lawsuit has not been dismissed, the case is now in the discovery process. The next major question is whether the cofounders stay in the case, or whether it affects only the corporations. Smithing notes that lobbyists for Google and others are trying to prevent laws around AI harms from being passed at the state level, which makes it incredibly difficult to react to problems like the one that took Garcia’s son.

Until we have a resolution to the suit, Garcia has become an advocate for AI safety at the state level, and has testified to policymakers in California. Unfortunately, the CA governor veto’d the bill that would have had a significant impact. She is encouraged by the bills passed in the EU and the UK, but notes that there’s significant work to do in the US and Canada. Garcia tells us: “This is a desperate plea from a mother. Pass legislation to keep your children safe, and it will help those of us in other countries as well.”

Garcia asks us to call these systems what they actually are: groomers. If children were having this sort of sexual conversation with a human, we would act to intervene. She believes that we need similar interventions before these intimate human relationships between machines and children damage children’s mental health.

The post Govern or Be Governed: Chatbots as the new threat to Children Online appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

October 23, 2025

Govern or Be Governed: What are the Threats to Freedom of Speech?

The afternoon at Govern or Be Governed starts with two of my heroes, Jameel Jaffer from the Knight First Amendment Institute, and Kate Klonick of St. John’s Law school as well as director of Center for Countering Digital Hate Imran Ahmed, who I’m hearing for the firs time here.

Klonick, moderating, notes that she’s been on panels for years about being in a perilous free speech moment, but none quite this perilous. Jameel suggests this is a terrible moment for free speech and democracy around the world, and particularly in the US. In the US, he argues, there’s no precedent in modern American history for Trump’s assault on institutions critical to democracy. This administration in its second term is not facing resistance within the government – during his last presidency, he was impeached twice, faced significant setbacks in the Supreme Court and had pressure from whistleblowers within federal agencies. Now he’s got a submissive Congress and a compliant Supreme Court.

Also, this time around, Trump is directly attacking democratic institutions, like universities and law firms. He’s demanding news organizations take down speakers he disagrees with. Those attacks on institutions has long-lasting effects on American democracy. Finally, American free speech culture may not have the resilience we thought it did. And now people fighting for free speech around the world no longer have the US as their reliable ally on these issues.

Imran, who works directly on issues of hate speech online, characterizes Jameel’s analysis as “top down” – he offers a contrasting bottom-up response, focused on the “industrialization of manipulation.” Unilateral control by a small coeterie of platforms by billionaries, with no meaningful checks and balances, leads to a highly manipulable environment. He references his friend and colleague Jo Cox as a victim of the dangerous environment in which hatred and lies are transmitted. The fact that truth and lies look identical online creates an environment in which distortion and hypertransmission of hate and lies masquerades as “free speech”.

Agreeing with the top down and bottom up diagnoses wonders who we can empower to help us in this perilous situation. She references Jack Balkin’s “free speech triangle” – censorship used to be about states censoring individuals. Now speech requires a democratic state and responsible corporate power, as well as individual bravery. Where do we find out power if states and corporations are cooperating to silence us?

Jameel notes that we’re moving away from direct intervention in content moderation into structural solutions, which seem more appropriate towards solving the problems of the information environment: transparency requirements, data ownership, interoperability, data portability. We should be supporting public digital infrastructures, public interest technologies because they would help address the current pathologies. He notes that the important questions of free speech are not about who can say what: they are about the political economy of platforms, the financial underpinnings of these critical media organizations, who have turned out to be willing to align with the Trump administration.

Imran argues that the incentives in the situation are counter to high quality discussion. The incentives associated with contemporary social media creates a cortisol-inducing, terrible landscape. This is not, he argues, a partisan issue – republicans and conservatives care about these issues as well. He tells us about a focus group his organization conducted with white, libertarian men in Denver, Colorado, and they’re shocked that they can’t sue the platforms under section 230. The most libertarian of the group wanted more accountability for the platforms. “Section 230 is an abomination”, he argues, a get out of jail free card. (Again, a reminder that I am transcribing here – this is not a point of view I endorse.)

Thankfully, we have a section 230 scholar on stage – the moderator, Kate – who explains the distinction between intermediary liability and a “get out of jail free” card. Imran’s response is to reference a colleague whose daughter killed herself after receiving content that negatively affected her mental health. “[Section 230] simply has no moral justification for existing as it does not.”

Jameel notes that removing Section 230 in the US would do nothing to change platform ability to amplify content because US law sees that content as protected speech under the first amendment. The structural solutions like data ownership and transparency would actually have an impact, he argues. We should focus on those interventions and on building alternatives. Imran counters that we need a meaningful sanction, including pulling section 230.

Kate leaves us with the concern that none of the levers we reach for actually work, which leaves us struggling for easy solutions, instead of the massive transformations we need.

The post Govern or Be Governed: What are the Threats to Freedom of Speech? appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

Govern or Be Governed: Protecting Creativity is Protecting Democracy

Baroness Beeban Kidron, filmmaker and member of UK House of Lords, joins the Govern or Be Governed conference via video from London. She notes that we are in a generation of “supercharged” scraping, that has sent rightholders alight. In losing copyright, she argues, we see an existential threat to creators who might lose the ability to earn a living, and to lose control over the meaning of their works.

Baroness Kidron via zoom at Govern or Be Governed

The UK government, she argues, has been to sacrifice the rights of creators to the desires of US AI companies. Along with Kate Bush, Elton John and Paul McCartney, she’s organized resistance to this legislation, and she assures us that “hostilities will soon resume”. That said, copyright is not the most urgent issue in tech governance, but it stands as a symbol for the rest of these issues. The stealing of the labor of creators, the repacking and selling it back to us threatens to kill creativity as an industry. In the UK, creative industries are the second most productive sector, and the source of a great deal of soft power.

I’m not against innovation, Kidron offers, but she suggests that there’s a difference between learning from art and looting it. The creative industries are not standing in the way of innovation – they ARE innovation. The creative industries have been imagining futures and steering us towards empowering visions. “The meaning of art is not a phrase for the pretentious or the privileged” – it’s an economically vital industry that gives £120b to the UK industry a year. Above that, it is the way we understand ourselves and each other. “Creativity is the mirror in which society sees its reflection.” Seeing that as a strip mine for machine learning, a set of resources that can transfer value from those who make culture to those who monetize it, is a transformation we must fight.

“Machines can imitate style, but they cannot produce meaning.” A world in which everything is copied but nothing is created is a world we have to avoid. The idea of technological inevitability is driving this field forward – we need to resist the idea that creativity is a nostalgic relic and accept that the creative industries are a real and powerful sector in a contemporary economy.

“When art becomes data and artists become invisible, we risk losing sight of what creativity actually is: a conversation between human beings based on empathy and understanding.” Respect for creators must be the foundation: without the author, no story, without the composer, no soundtrack. Being AI ready means being arts ready, respecting the creativity that has brought this world about.

The fight ahead will be about the very infrastructure of the digital world ahead. Who gets to sway public opinion, who is the collateral damage? Tech has learned to play democracy, but it captures the infrastructures beneath our feet, she says. We experience a perilous dependency on these platforms and tools, and the battle for creativity is a battle for democracy itself.

The post Govern or Be Governed: Protecting Creativity is Protecting Democracy appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

Frank McCourt on the value of personal data at Govern or be Governed

Frank McCourt is a real estate magnate turned sports team owner, and now a digital freedom advocate. In 2021, he founded Project Liberty, an initiative to rethink social media as a public good. In 2024, he published a book on that topic, Our Biggest Fight: Reclaiming Liberty, Humanity and Dignity in the Digital Age.

(I’m transcribing what McCourt is saying, to the best of my abilities. I don’t endorse anything specific he’s saying here.)

Asked why he’s interested in digital media, McCourt refers to his children – he’s got eight, four older, four younger and notes how different it’s been raising children in the current digital age. He refers to his family background in building highways as connecting him to building future internet infrastructure.

McCourt references the coverage of his divorce in LA media (and controversy over his ownership of the LA Dodgers) as alerting him to the power of the contemporary internet. He saw the internet of that time as becoming “performance based”, focused on likes and clicks. His analogy for his experience was trying to put out a house fire with a small garden hose while thousands of people poured gasoline on it. His response to being dragged in social media was to talk to policymakers about the incentives and structures of social media. After founding a public policy school at Georgetown, he decided that we needed technological interventions as well. His goal is building a technology stack not centered on surveillance, but on public values.

His “aha moment” came from bringing “brilliant technologists” together and inviting them to think what an alternative could be. The internet was just fine, he tells us, until some people figured out that “data was gold” and that they needed to extract as much data as possible. “In social, shopping or search, it was our personal information that gave us incredible insight about us.” These companies, he asserts, know us better than we know ourselves. So why not a protocol that gives us ownership of our personal data?

He references Buckminster Fuller to suggest we not try to fix existing social media, but create a new technology from the ground up to work in a different paradigm. “And now there are 14 million people using it, so there is no question it can scale.” (He acknowledges that in an internet that connects multiple billions of people, that’s pretty small.)

“It’s fine to have GDPR, DSA and so”, but why not have technology that bakes those priorities into the technology, he asks? He’s thoughtful in noting that there are other people in the room building alternative technologies, and he doesn’t assert that he’s got the silver bullet. The problems are well defined, he argues, but we now need to pivot to the solutions. (The moderator references Gander, a Canadian social network designed around an alternate set of values.)

Asked about his failed bid for TikTok, McCourt says that TikTok was never the goal, just an opportunity – bringing a non-surveillant stack to 184m TikTok users (presumably just the US users?) would create momentum for his alternative architecture. McCourt argues that your data is worth something individually, not just in aggregate – the valuation of tech companies proves data is valuable: why aren’t we getting something from it?

Frank McCourt at Govern or Be Governed

Raising $20b suggests that there are people excited by his vision, McCourt says. He notes that the solution on the table from the Trump administration doesn’t comply with US law, and suggests that Chinese technology can influence the opinions of 184 million Americans.

“It’s really hard to change 30 years of entrenched technology.” When tech changes is when space opens and new designs can take hold. We’ve had a certain version of the internet, now a highly centralized, app centric internet – the shift to an “agentic web” is our moment to make a change. “It’s much easier to change the direction of technology” when tech shifts. But it’s a narrow window, he says, and big tech companies are moving so fast because they see this moment as threatening.

“Don’t think of AI and social differently. What was our social graph and personal information exploited in Web2.0. The version in AI will be our AI context, the context we share with an LLM.” (I agree with him on the context point, but will make my case that AI is far more centralizing than social media in my remarks later today.)

“That information should be ours, not the company’s. Just like our social graph information should be ours.” We should be able to move our context from one platform to another.

Asked whether there are enough people who believe in alternatives visions of the internet, McCourt argues that another internet has been built. He references his history helping build RCN, a telco that challenged existing telcos shifting from copper to fiber. By seeing that shift, he argues, he was able to capitalize on the rise of home internet. When RCN was taking off, he notes that people didn’t want to adopt the service because they couldn’t take their phone numbers with themL – why aren’t people up in arms about the need to migrate their social graphs?

Asked what people in this room – policy officials, philanthropic organizations, activists – can do, McCourt asks us to imagine a different paradigm. “It’s just technology, it works a certain way because it’s been designed to work that way. It can work in an entirely different way.” Project Liberty has three different tracks: technology, policy and coalition building. “We just need people to understand what’s at stake and demand it.”

McCourt’s hopeful vision is that our data is worth huge amounts of money: transferring ownership from the tech companies to individuals “could be the largest redistribution of wealth in history, without taxes.” Big Tech doesn’t want us to understand that our data is us, which allows us to be manipulated and challenges our free will. “Our data is our personhood, our digital DNA.” It’s a human right “and also a property right: your data is really valuable.”

The post Frank McCourt on the value of personal data at Govern or be Governed appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

Govern or Be Governed: Can Anyone Regulate Big Tech?

I’m in Montreal today and tomorrow at a conference titled Attention: Govern or be Governed. I’m speaking later today, along with friends Ivan Sigal and Mark Surman, about the future of technologies for democracy. It’s quite the event: my friend Taylor Owen from McGill has brought together a mix of policymakers (particularly European and Canadian), activists and technologists to talk about this very weird moment in technology and politics.

Taylor warns that there’s an incredible incentive at the moment to lock in power, both of corporations and states. That moment is aggravated by the particular moment of US state power – we’ve never seen a moment where US state power is exerting extreme trade and diplomatic power to protect tech industries and their overreach. The goal is to have a global conversation in Canada, a place that feels like it’s on the front lines of these battles. Canada is facing extreme pressure from the US, including pressure to abandon the digital services tax, and is feeling reluctance to pursue new regulations at a moment where the sovereignty of the nation is at risk. So this becomes an interesting place to reimagine how these technologies can and should be governed.

The opening speaker is EU commissioner Michael McGrath. He’s the Irish Commissioner responsible for democracy, justice, the rule of law and consumer protection, joining the EU Commission after 25 years in Irish politics.

He starts his remarks off with a bang: “Algorithms fuel apathy, public discourse is manipulated, and disinformation spreads like wildfire.” His theory is that technology amplifies power, which means a tool like radio – and by extension, the internet – can be a tool for repression or for liberation. “We do not have a technology problem… Instead, we have a governance problem.” Societies must decide whether they want to govern technology, or be governed by it.

His closing reminder: freedom is not the absence of rules. Rules enable freedom, if they are transparent and accountable.

Key to this is accountability. When citizens report scams, when journalists expose ill effects, when anyone alters an algorithm to their benefit, they are holding tech accountable. But we’re seeing power exert influence through technology, with Russian disinformation actors using social media and AI to manipulate public opinion. This is especially worrisome to the EU, an organization founded in the wake of WWII, an assault on democracy by autocracy.

McGrath outlines three pillars of the EU approach to tech regulation. It’s a risk-based approach, which tries to identify systemic risks and shift the burden of proof to the companies. The DSA and AI Act means “the companies that design these online spaces must also design the safeguards we rely on.” It’s also a user-centric approach, which gives users the ability to appeal content takedowns. While it’s characterized as censorship legislation, he asserts that it’s the opposite – it’s the best regime we’ve seen for asserting the right to speak online. Finally, it seeks transparency, ensuring that media remains independent and people understand who’s paying for the content they see.

In a rare moment of equivocation, McGrath notes that Australia has restricted social media to people 16 and under – he notes it’s a complex issue, that the European Commission is meeting with experts and keeping the rights of children in mind as it considers restrictions.

McGrath introduces the “European Democracy Shield”, an EC effort to protect and invest in EU democracies and media. It’s necessary, he says, for three reasons:

– The transformation of the public sphere, with the concentration of power in large media companies

– The rise of authoritarian actors undermining rights and freedoms, including election interference. He cites Moldova’s experience with election interference as an example of these battles.

– A societal transformation in which young people are increasingly unenchanted with democratic values, sometimes embracing extreme nationalism.

To protect European freedom, which he argues is well-understood through high rankings on metrics like press freedom, we need a shield. “Democracy itself is the shield. We do not protect democracy for reasons of abstract ideals – we protect democracy because it protects us.”

The shield seeks to reinforce the integrity of the information space, to ensure elections are free from interference, and to create democratic resilience, counterattacking against disinformation, and seeking to strengthen public trust in democracy.

McGrath is followed by a panel of individuals who work day to day on the information ecosystem. Sasha Havlicek of the Institute for Strategic Dialog notes that social media platforms systemically amplify antidemocratic speech, and have started blocking access to the information we need to study these effects. While we’ve made progress on speak-protective ruls, Havilchek argues, the solution is transparency. If you believe social media is biased one way or another, it is in your interest to ensure that there is data that allows us to investigate these claims. We need more legislation like DSA 40, and we need processes that allow people to appeal suspensions and restrictions on their speech.

European MP Alexandra Geese notes that the Digital Services Act is an impressive piece of legislation, but is not being enforced sufficiently. There is an article in the DSA about systemic risk to minors – why aren’t we enforcing that provision, and instead trying to pass more legislation around minors specifically? This is especially true, she argues, regarding systemic risks to democracy. It’s harder than ever to find content that is not extreme or antidemocratic. What’s the agenda-setting that’s coming about from algorithms that appear to be amplifying extreme political content?

Why isn’t the EC enforcing the DSA? In part, it’s because JD Vance has threatened to pull out of NATO if the DSA has real consequences for US tech companies.

Sir Jeremy Wright, former UK Secretary of State for Digital, Cultural, Media and Sport, offers and apology for the ways in which legislation falls short of goals: we never get entirely what we want, due to the compromises of the legislative process. But we appear to be passing “framework legislation”, and leaving most of the work to the regulators. Right now, the Trump administration threats are having a great deal of impact on what regulators do. “But we still do have power to act,” though more progress is possible. As we move forward the goal needs to be passing legislation that is actually implementable.

The post Govern or Be Governed: Can Anyone Regulate Big Tech? appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

October 16, 2025

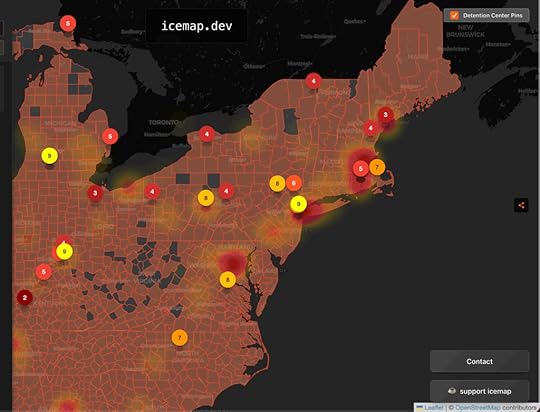

Tracking ICE with Media Cloud data

I’m starting my day at MIT at a conference on the quantitative analysis of news, hosted by the folks behind Media Cloud. I shared the stage in the first session with an inspiring set of students, Jack Vu and Abby Manuel, who’ve developed icemap.dev, a map of ICE activity across the US using news data.

Jack and Abby were high school students in Houston, TX and both worked with an academic enrichment program that supported immigrant kids from Guatemala. They noticed that the kids were no longer coming around and discovered that ICE raids in Houston left their students feeling unsafe to leave the house. So they decided to start mapping ICE activity across the country at icemap.dev

They considered a crowdsourced platform, but understood that a) they’d need to build a huge userbase for the tool to have crowdsourcing work and b) they couldn’t know whether all reports were accurate. So instead, they decided to work with news reports, assuming that news reporting would act as a form of quality control. Fortunately, they stumbled on Media Cloud, which is already scraping data from tens of thousands of news outlets on a daily basis, and making that data available via an API.

Jack and Abby search for ICE on Media Cloud and collect new articles every day. They then use DeepSeek to verify whether articles are about ICE raids, to categorize what’s going on in the various stories and store location information and type of incidents in a CSV.

Using Open Street Map and the Leaflet mapping library, they’ve created a map that shows reports of ICE arrests and raids, as well as reports about poor conditions in ICE detention centers. In addition to Media Cloud reports, the site uses data from US government sources and from a nonprofit clearing house that tracks reports from detention centers. Abby explains that using data from the news is critical to ensure that the project represents the voices of people affected, not just government officials.

My talk at Media Cloud traced the origins of the project back to some questions I was asking about undercovered news stories in the global South. It makes me insanely happy that, twenty years later, badass students who weren’t born when we started this work are using it to do something as socially important as visualizing government violence against undocumented migrants.

The post Tracking ICE with Media Cloud data appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

Ethan Zuckerman's Blog

- Ethan Zuckerman's profile

- 21 followers