Zeynep Tufekci's Blog

February 4, 2023

Who should worry about H5N1?

My New York Times columns have returned to dealing with a range of topics, some I’d never have expected to write about, like the royals(!), and some of the usual such as software infrastructure and technical debt, generative artificial intelligence programs like ChatGPT, but a familiar one, too.

Emerging potential pandemics and how to stop them from being actual ones, namely the current H5N1 avian influenza outbreak—the biggest one historically. (Notice the price of eggs?)

Why write about it at all since the risk to humans is so low to be quite negligible at the moment? (Mostly: don’t pick up dead birds for the rest of us who don’t work on poultry or mink farms.)

Because something unprecedented happened — H5N1 infected minks, and then a mutant version likely spread among them. The first mammal-to-mammal transmission. That is a big deal.

The pace of developments has been disquieting. Until 2020, when the new H5N1 strain began to spread extensively among wild birds, most big outbreaks occurred among poultry. But now, with wild birds acting as conduits, it’s not just the biggest outbreak ever among poultry, causing the death of at least 150 million animals so far, but it is also steadily expanding its reach, including to mammal species like dolphins and bears.

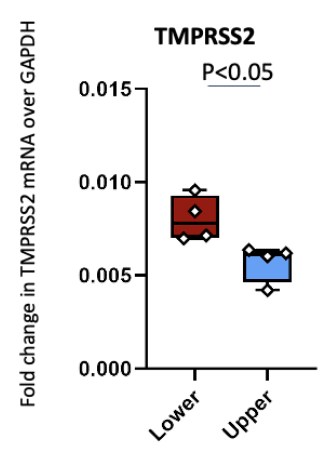

In 2006, when scientists discovered that H5N1 had not spread easily among humans because it settles deep in their lungs, Kuiken of Erasmus University Medical Center warned that if the virus evolved to bind to receptors in the upper respiratory tract — from which it could become more easily airborne — the risk of a pandemic among humans would rise substantially. The mink outbreak in Spain is a signal that we might be moving along exactly that path.

All this makes it time for the authorities to act really aggressively to counter this threat so that we don’t have to think about it, as ordinary people. Will they? I wish I could be confident they will quietly get the job done, and we don’t have to think about it at all.

Minks have an upper respiratory tract quite similar to humans, and their very close cousins, ferrets, are used as human proxies in experiments with respiratory viruses exactly for that reason. During the early days of the COVID pandemic, in 2020, before there was any new variant that had taken hold in the human population, minks in farms in Denmark got infected from humans, generated new variants which then found their way back into the human population: reverse zoonosis to minks to an uncontrollable spread which generated new variants and then zoonosis back to humans. Not good. Denmark quickly culled 17 million minks: another tragedy, really, on top of the tragedy of keeping otherwise solitary hunter carnivorous mammals — minks and ferrets aren’t rodents — in crowded, packed industrial facilities only to kill them at six months old for their fur. It’s bad enough to keep herd animals in industrial settings; it seems exceptionally cruel to keep solitary ones.

American Mink, by Akulatraxas, Creative Commons licensed

American Mink, by Akulatraxas, Creative Commons licensedYou can read the piece here, including about the state of vaccines for H5N1. We have them, which is great, but not in enough numbers for a serious outbreak. The plan is to mass produce them if and when there is one. Well, there is a twist, though.

Worryingly, all but one of the approved vaccines are produced by incubating each dose in an egg. The U.S. government keeps hundreds of thousands of chickens in secret farms with bodyguards. (It’s true!) But the bodyguards are presumably there to fend off terror attacks, not a virus. Relying on chickens to produce vaccines against a virus that has a 90 percent to 100 percent fatality rate among poultry has the makings of the most unfunny which-came-first, the-chicken-or-the-egg riddle.

The only company with an F.D.A.-approved non-egg-based H5N1 vaccine expects to be able to produce 150 million doses within six months of the declaration of a pandemic. But there are seven billion people in the world.

My piece was on what authorities should do about vaccinating poultry and pigs, shutting down mink farms, developing faster and non-egg based platforms for H5N1 vaccines, stepping up the surveillance globally to detect an outbreak quickly so we can crush it before it goes anywhere. The online commentary had a lot of people who wanted instead wanted to talk about… lockdowns, masks, social distancing, vaccine mandates, etc. etc.

Ouch. That feels like people wanting to yell at their TV because they were annoyed about how the weather reporters behaved during the last hurricane, even as a potential new one is bearing down. The new one doesn’t care.

One feedback I got was why I didn’t talk enough about the role vaccine hesitancy may play in a potential H5N1 pandemic. One key reason, of course, is space. Not everything fits into a single column.

But also there’s a reason why people who remember the pre-vaccine era — seniors — are so much friendlier to vaccination, even if they are not otherwise, say, liberals.

The H5N1 current fatality rate among known cases is 56% though it’s important to note an eventual human version (which I hope never comes around) would likely be much less. That number comes from the few hundred detected cases over the past two decades, and who knows how many we’re missing. The good news so far about H5N1 is that while people can get infected through very close contact with birds, often poultry workers in farms, but it doesn’t seem to go anywhere else. There may well have been many more cases, lowering that rate.

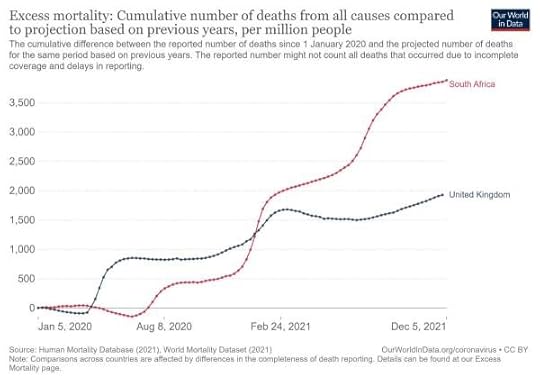

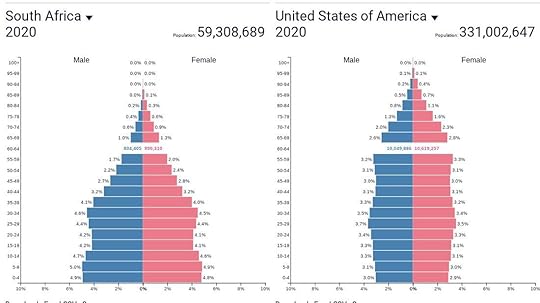

Still, though, lower than 56% has a long way to go before one can brush it off. The death rate among the infected minks was about 5%, a much lower number than 56% but… a catastrophic number, really. In Wuhan, without any treatment or vaccine, the initial case fatality rate was about 1.4%, and that was catastrophic. And that’s just deaths. In addition, COVID severity was exponential with age. Influenza is less steep a curve, even though it also tragically affects the elderly more. In addition influenza also tends to claim a lot more children. This isn’t downplaying one virus against the other, obviously, but the mortality rates and profiles do generate a different political space for the opportunists.

Many of the anti-vaccine players seem to be playing a game of lucrative grift usually via outright misrepresentation — and some are even MDs, which is atrocious. Some of this made possible by the fact that our vaccines are so, so good and most people are sensibly vaccinated — especially children against so many terrible childhood diseases. The resistance seems to be towards new vaccines, but it is slowly seeping into existing vaccines. If that spreads, the problem will likely be self-limiting in the sense that the catastrophic outcomes will quickly provide the corrective, but at a great cost. Same likely would happen with his, but again at a great human cost.

And, yes, I really did write about the brouhaha around Prince Harry’s memoirs — but it’s not about the royals, really. I wanted to counter the tendency to dismiss it as a mere celebrity kerfuffle when, in fact, it was an opportunity to talk about something quite insidious: the politically-influential British tabloids and their ugly but effective campaigns. It’s not just the UK, either.

Sometimes, it’s the famous people that provide insight into an important dynamic, and both the book and the documentary deal with a lot more substantial topics than media coverage would indicate — but yes, feel free to ignore the purely celebrity aspects which do get a lot of (boring to me) coverage.

So I wrote the piece because I think the case around Prince Harry and Meghan Markle provides an insight into much else, including Brexit.

The way the tabloids can spread unhinged claims, generating a sense of urgent threat to create a social frenzy, can be used for targets other than a stray royal.

During the run-up to the Brexit vote, among other outright big lies, British tabloids screeched that, thanks to a secret conspiracy being cooked up in Brussels, the European Union would allow hordes of Turks to invade Britain, commit crimes, have too many babies and bankrupt the social services. Turkey isn’t even a member of the E.U. and is nowhere near becoming one. Brexit narrowly won, with damaging consequences still unfolding for Britain.

But at a human level, too, what has been happening to the couple is terrible, and inexcusable. The UK tabloids churn out awful multiple pieces about them, day-after-day, now for years. And also journalists who are treated as respectable ones also participate in this, in the most awful manner, often without any repercussions.

But, I must say there was something refreshing about the aftermath of that piece. It was a change of pace! No more discussions about legacy code or vaccines!

Instead, there was a huge amount of swirl, on social media and on Reddit, by monarchists and royalists —I suppose? — who decided I was evil incarnate for talking about the way the royal family and the British tabloids collude in a terrible manner, and that I was in the pay of Harry and Meghan (obviously 100% false), including very large numbers of people trying to carefully dig through my CV to prove my status as a puppet of the Duke and Duchess of Sussex. (The Markle-hate Reddit group where most of this took place had 40 thousand people in it!)

A bunch of them were expressing that they would carefully watch my future writings, and keep doing investigations to prove that I was in the pay of Big Montecito, I guess, where the couple now reside.

Anyway, I hope they enjoyed my next column, on H5N1.

And we shouldn’t farm minks, even if this threat passes. It’s cruel, unethical, unnecessary and dangerous.

Thanks for reading Insight! Subscribe for free to receive updates about my work.

October 16, 2022

On the Alex Jones Verdict: The Very, Very Lucrative World of Lying

My latest piece for the New York Times returns to a key question: how should we grapple with the current historic transformation of the public sphere? I focus on the Alex Jones trial and verdict, but my question is about the future: what can we do, what should we do, to prevent future cases?

I suggest that we take a closer look at money as an incentive, and also focus on friction as an answer.

Jones’ net worth was estimated during the trial to be anywhere between $135 to $270 million, and much of this comes from peddling dubious supplements, survivalist gear, flouride-free toothpaste, what-have-you. The trial revealed that his company makes many tens of millions of dollars each year from selling such merchandise, and that the Sandy Hook families reached out to him in anguish many times only to be rebuffed, according to the families, because the topic was so lucrative for his sales.

This type of money is a huge part of the incentive structure that shapes so much of our societal woes, and is often overlooked to the key role it plays.

It’s become so easy to lucratively lie to so many people, and we have few realistic and effective defenses against the harms of deceptions like these, not just to individuals but to our society.

“Good speech” isn’t going to push out lies when viewership is so fragmented, nor is the solution “fact checks” of various levels of quality by institutions already not trusted by many.

There have been campaigns to get major social media platforms to act more aggressively to get rid of liars, but why should we trust them to decide who should be banned? What if political winds shift?

What’s the solution? No society can be constantly pulled at its seams like this and escape unscathed. The recent Jones verdict certainly did some damage to the industry of lucrative lying, and perhaps few are as deserving of this result than he is. But laws written for a different era cannot resolve the problems of our current media ecology.

There are no easy, quick solutions, but perhaps a starting point would be to make it harder and less lucrative to lie to huge audiences. Rather than pursuing legally dubious and inadvisable efforts to ban speech or define and target misinformation, regulations should target the incentives for and the speed with which lies can be spread, amplified and monetized.

Plus, a lot of this lying is very cynical. Many have likely heard that Alex Jones has been ordered to pay about one billion to Sandy Hook families in two separate defamation lawsuits. But did you also know that his lawyers had pretty much said that he lies on purpose, that what he’s doing is “performance art”, of someone “playing a character”, comparing him to Jack Nicholson playing Joker on the move Batman:

Using Jones' on-air persona to evaluate his temperament as a father, Jones' attorney said in the pre-trial hearing, according to the Statesman, would be like judging Jack Nicholson based on his role as the Joker in "Batman."

Some Fox News hosts had taken to claiming that voting machine fraud had helped Joe Biden win the election. One voting machine company sent a legal letter in December of 2020, asking them to stop the “false and defamatory” statements, and clearly hinting at a lawsuit. Lo and behold, we witnessed a stunning Road to Damascus moment. The same Fox News host making these claims quickly created a lengthy fact-checking segment, debunking their own lies, and it was run on all the shows that had featured the lie and were named in the letter.

Interestingly, the companies are still going ahead with the lawsuit, rather than settling for some money as it is usually done, a clear sign that they likely think they can prove to the very high standards of US defamation law that the lying was knowingly done, and that they can show that in court—it other words, there is no ideological commitment here, just cynical lying. But, of course, the damage is done and can’t be easily reversed however the lawsuits may eventually conclude.

A street photo of the three card Monte con (source)

A street photo of the three card Monte con (source) None of this is without cost. As I write in my piece, Fox News itself had vaccine mandates and even masking rules. But you wouldn’t know that from their anti-vaccine and anti-masking content. Unfortunately, the damage is real. A recent study in Nature finds Fox News viewership was associated with lower vaccination rates, and not because of health care capacity or even Republican partisanship. It’s a great study, by the way, doing a lot of nice work to go beyond association, to show why this is likely a causal link — I especially liked how they used the cable lineup position, which arbitrarily varies geographically but can cause higher viewership for channels lister earlier, to strengthen their case.

A recent study in Nature found that areas with higher levels of Fox News viewership had lower Covid vaccination rates, which are associated with higher hospitalization and death rates. This impact of Fox News was independent of local health care capacity or even partisanship. Plus, much of this effect was concentrated on people younger than 65, who might have thought they were safer from Covid, the study authors noted, and perhaps more open to messages of vaccine hesitancy and refusal.

And who suffers? It’s rarely the cynical, wealthy liars and hypocrites:

Even foot soldiers of the movement who sincerely bought into the antivax nonsense, suffered. According to a report from The Boston Globe, at least five conservative radio talk show hosts who campaigned against the vaccines died from Covid-19 over just a few months in 2021.

The internet has brought about many positive changes that helped expand speech rights, not just in the United States but around the world, but no such historic transition is easy or uniformly good. In fact, such transitions are often deeply destabilizing, and accompanied by much suffering.

The printing press may have launched encyclopedias and the wonderful world of books, but as many historians point out, one of immediate downstream consequences was the Thirty Years War, dubbed a “media event” by historian Peter Wilson, which may have resulted in as much as 20% of Europe’s population perishing. Recognizing this is obviously not wishing we never got the printing press or books, but just that major historical transitions are often very, very painful.

Spread of other communication technologies hasn’t been all rosy either.

The 1915 silent film “Birth of a Nation”, for example, was heralded for its technical virtuosity — it’s also the first American 12-reel film — and it became a huge commercial success with its despicable and reprehensible racist storyline, which showed, among other things, black people stealing elections and blocking white people from voting unless held back via violence by the fictionalized Klan, which is portrayed as the heroic bulwark against black people portrayed as rapists and lowlifes. The film has been credited for helping inspire the rebirth of the actual Klan a few months later.

Hitler’s filmmaker, Leni Riefenstahl, was also quite talented, and has invented or refined many techniques of modern filmography while helping Hitler, whose persuasive gifts were more suited to the scale of the beer halls that he rose from, to appear charismatic and heroic to the broader masses through her films.

Obviously, this is not a call to suggest we ban films, or even wishing they didn’t exist. Clearly, a single movie doesn’t suddenly turn a nation otherwise devoted to racial equity into one where events on the scale of the Tulsa massacre would happen shortly afterwards.

But we should recognize that a constant barrage of lies and dehumanizing propaganda are often part and parcel of the road to mayhem and even large-scale violence, and each societal transition renews the challenge of finding better, updated ways to face this reality.

This is one big reason why every new communication milieu brought about by technological and political changes has to be grappled with, but without nostalgia — as the past is rarely perfect, but in any case it’s not coming back — or without sloganeering. Oft-repeated formulations like “let more speech counter bad speech” or “technology can be good or bad” don’t even begin to get at the current problems partly because they don’t even describe the current problems.

Is there an easy solution? Of course not. I outline some of what I think we can do in my piece — and, frankly, I find a lot of the current efforts on fact-checking or defining/targeting misinformation to be lacking, ineffective or even unadvisable — but I’ll be first to concede a problem of this magnitude will not lend itself to easy solutions.

I also think friction is underrated as a structural answer. Just like the important maxim from the field of complex systems that “More is Different”, it’s also important to recognize that Faster is Different. Slowing down the juggernaut through careful and considered mechanisms might go a long way, without either the governments or the social media companies having to be appointed as hasty arbiters of truth — something that we should approach with great caution.

It’s quite possible there will need to be repeated efforts, some of which may not work out and need to be modified, rollbacked and updated.

The work of civilization is not just discovering and unleashing new and powerful technologies, it is also regulating and shaping them, and crafting norms and values through education and awareness, that make societies healthier and function better. We are late to grapple with all of this, but late is better than never.

It’s not without hope — we’ve overcome many challenges before. But I’ll keep saying this: we have to try, rather than surrender to nihilism and just declare it’s too hard, and nothing can be done. To go back to my initial point: No society can make it so lucrative and so easy to be pulled at its seams like this and escape unscathed. We have to try.

Thanks for reading Insight! Subscribe for free to receive new posts.

August 25, 2022

Long Covid, The Long History Version

I spent most of my summer researching our Long Covid response. The first (I hope) of many pieces on this topic is out today, in the New York Times:

When the influenza pandemic of 1918-19 ended, misery continued.

Many who survived became enervated and depressed. They developed tremors and nervous complications. Similar waves of illness had followed the 1889 pandemic, with one report noting thousands “in debt and unable to work” and another describing people left “pale, listless and full of fears.”

The scientists Oliver Sacks and Joel Vilensky warned in 2005 that a future pandemic could bring waves of illness in its aftermath, noting “a recurring association, since the time of Hippocrates, between influenza epidemics and encephalitis-like diseases” in their wakes.

Then came the Covid-19 pandemic, the worst viral outbreak in a century, and when sufferers complained of serious symptoms that came after they had recovered from their initial illness, they were often told it was all in their head or unrelated to their earlier infection.

Of all the topics I’ve researched throughout the pandemic, none have left me more despairing, on behalf of the patients, but also captivated by the historic, scientific and human story—I knew a few broad outlines from before, but everywhere I looked, I saw hugely-important issues and dynamics that, to this day, are underappreciated.

This particular piece focused on our response, especially our inadequate and even confusing and poorly-done research efforts. But there’s so much more to cover.

To start with: how medicine dismisses things it doesn’t (yet) understand, and worse, refuses to learn from episodes that make the denial hard to maintain. Post-pandemic or post-epidemic discovery of complicated post-viral conditions occurs again and again in history, to be forgotten till the next time.

Post-viral ailments pop up in so many areas: cancers, neurogenerative disorders, chronic complex conditions and who knows what else, and yet, while the dots are hard to connect, and not enough is properly researched to begin with. Imagine trying to understand the connection between shingles in 50+ year-olds and childhood chickenpox, without even a proper germ theory of disease. That’s how some of this feels like.

Also: the way a forced, binary mind/body duality operates in both clinical medicine and scientific research is an important sociological and scientific story, both to be written more about but crucially, to address. This could impact everything from how we understand and approach conditions like depression and anxiety, as well as many chronic conditions. For all we know, there are deep dynamics that are mutual and multi-directional that connect all of this, and an integrated and humane approach to neuropsychiatry can bring so much benefit to so many.

And then the patients and the sufferers… Not just Long Covid, but many other chronic conditions that have long been ignored or denied. Historically, both multiple sclerosis and ulcers were once treated as “in your head” diseases, with patients blamed until the imaging showed the brain lesions, and the bacteria causing the ulcers was finally discovered. And again, we all would benefit from an integrated approach that uncovered more.

I also despair at how much poor research is being produced in this area—going viral on social media, uncritically amplified by traditional media as well, and some honest, rigorous scientists being incorrectly villified as minimizers or deniers when they are the ones doing the right thing, which is to try to bring rigor, science clarity to all this. If we chase away all the good scientists, who will work on this? Sympathy is great, but we need the highest levels of science to make progress. I think this stems from a combination of issues: weak, muddled definitions, inadequate data and researchers overselling their findings to gullible journalists.

I also think poor research has really, really hurt the effort to get this condition understood and recognized because many people look at the terrible, vague definitions and clearly implausible claims floating around and incorrectly decide it’s all fake.

Under the C.D.C. definition, someone with a single symptom just four weeks after illness can be lumped under the long Covid umbrella with someone bedbound for years.

And such vague definitions that don’t distinguish transient issues from chronic conditions, mild symptoms from debilitating ones, and different categories of illness from each other, impede research, treatment and acceptance.

The symptom descriptions for long Covid are too vague. Do “brain fog” and “fatigue” mean people don’t feel as sharp as they were and are a little off their jogging times, or are they experiencing a cognitive crisis so profound that they cannot find words and are so fatigued that brushing their teeth leaves them unable to get out of bed for the rest of the day? The latter has happened even to some people who had mild bouts of Covid-19.

Without clarity, how can we research or treat?

Existing definitions fail to capture the subcategories of long Covid, with different symptom clusters and levels of severity and persistence, creating an obstacle to research and treatments.

So my piece calls for a National Institute for Post-Viral Conditions. For real. We owe it to the many, many people suffering from a chronic, debilitating condition that they caught during a pandemic where the public health response was inadequate in many aspects.

But I mean this most sincerely: I think we all would benefit:

But solving this puzzle could be revolutionary, unlocking the door to understanding many conditions that cause much human suffering.

The 1971 National Cancer Act changed the way scientists deal with disease, pouring money into prevention, detection and research.

Scientists battling debilitating, chronic conditions like long Covid and other postviral conditions deserve this sort of commitment in leadership, funding and recruitment to get the best minds in the fight.

We need a National Institute for Postviral Conditions, similar to the National Cancer Institute, to oversee and integrate research. Neither academia — prone to silos and drawn to work that leads to notable publications, which can leave important questions underexplored — nor the private sector — focused on profits — is up to the task alone.

With such an initiative, we could honestly tell so many looking for answers that help is on the way.

The more one looks, the clearer it is that viruses are indeed “bad news wrapped in protein”, as two scientists memorably described them before. Developing more vaccines against more of them, and broadening how we understand, research, approach and, hopefully, treat these conditions is a very promising avenue for improving our well-being. Here’s to hoping for change, and soon.

June 19, 2022

Reprint: In Memory of My Grandmother

(I originally wrote this essay in 2016 for my old newsletter here, and made it public in 2019 after she passed away so some people may have seen it before. I’m including it here to keep it all in one place. The pandemic, tragically, had a lot of “debate” about the value of elderly life. My grandmother was very sober about aging—”when it’s my time, it’s my time”, she always said. But her last decade into her nineties was full of love and life, and I’m grateful for having the chance to share it with her.)

In Memory of my Grandmother: "Educate Your Girls, Cherish Your Good Memories"My beloved grandmother passed away last night, peacefully in her sleep. She had a stroke a few years ago and spent the last three years happy, but without being able to form significant new memories. … She was a remarkable woman, and changed so many lives besides mine. I will always hold her memory in my heart, and her example as one to live up to. -zeynep 5/5/2019

Lessons from my Grandmother: Educate Your Girls; Cherish Your Good Memories. By Zeynep Tufekci written on 11/17/2016I started writing this, my first newsletter, by my grandmother’s bedside, when I traveled to Istanbul, Turkey last week to visit her after she suffered from a stroke. She’s now 94, and she was born the very month the Republic of Turkey was declared, in 1923. Republic day (October 29th) is a national holiday in Turkey, as well as the day we celebrate my grandmother’s birthday since we don’t know the exact date.

This year feels like a turning point for both.

Turkey’s been in the news a lot lately. A bloody coup, barely averted. The state of journalism. Arrests. Internet shutdowns. Explosions. It’s also very difficult for me to truly follow and understand the news from Turkey in detail anymore—neither mass media nor social media seem reliable in conveying what’s truly going on.

I also cannot speak to my grandmother about her life stories anymore. The stroke in left temporal lobe has deeply affected her memory, and much is lost. She recognized me though, and immediately wanted to feed me—her deepest instinct, probably.

I told her that my forthcoming book—which includes parts of the story of her miraculous journey to get an education that I’m about to tell—was dedicated to her, and she was thrilled and emotional. She forgot about it in about five minutes. So I told her again, and she was just as thrilled and emotional. Then she forgot about it again, and I told her again. You got it: she was thrilled.

So we had a few days together last week, her asking me if I had enough to eat every five minutes, and me telling her that I dedicated my book to her every five minutes. It was difficult, and it was full of grief for me. But it was also joyful. She was not sad at all.

My grandmother repeatedly prayed in gratitude to three people in her life: Ataturk, the founder of the Republic of Turkey, her elementary school teacher who made her education possible, and Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone. I recounted her semi-miraculous story in my (forthcoming) book on networked social movements:

When my grandmother was about 13 years old and living in a small town near Mediterranean coast in Turkey, she won a scholarship to the most prestigious boarding school in Istanbul. Just two years earlier she had been told her formal education was over, after completing fifth grade. As far as her family was concerned, that was more than enough education for a girl. It was time for marriage, not geometry or history.

My grandmother didn’t know her exact birth date. Her mother had said she was born just as the grapes were being harvested and pressed into molasses in preparation for the upcoming winter, and just as word of the proclamation of the new Republic of Turkey reached her town. That would put her birthday in the fall of 1923, as the world struggled to emerge from the ruins of World War I. It was also a time of transition and change for Turkey, for her family, and for her. The new central government, born from the ashes of the crumbling Ottoman Empire, was intent on modernizing the country and emulating European systems. They made a push for spreading schools and standardized education. Teachers were appointed around the country, even to remote provinces. One of those teachers remembered a bright female pupil who had been yanked from school, and secretly entered her into a nation-wide scholarship exam to find and educate gifted girls.“And then, my name appeared in a newspaper,” my grandmother said. She told me the story often, tearing up each time.In a small miracle and a testament to the unsettled nature of the era, my grandmother’s teacher prevailed over her family, and she boarded a train to the faraway city of Istanbul to attend an elite school. [The teacher had also signed her documents, promising to pay all her educational costs were she to fail. In effect, the teacher had stepped up in lieu of a parent, at great financial risk to himself. My grandma’s family tried to prevent her from leaving, and her older brother almost blocked her path—an act he later apologized for many times. But the teacher persevered and succeeded—a dramatic act, changing someone’s life forever.]

My grandmother was joined by dozens of bright girls from around the country who had made similar, miraculous for the time, journeys. They all got a superb education. After she got her high school degree, my grandmother became a teacher: marrying a little too quickly as my grandfather pursued her aggressively, and she relented. She sometimes wondered what else she could have done. But she loved being an elementary school teacher.

My grandmother wasn’t just a great teacher in the formal classroom—her students always showed remarkable improvement in the years they had her—but she also basically became everyone’s teacher. She was the first person in her family to graduate from high school, let alone college. Practically every child, grandchild, nephew and niece after her ended up going to college and beyond, to a large degree because of her. She insisted that everyone go to school. She taught them how to navigate exams, how to pick majors, how to study, how to apply to schools and scholarships. When parents were reluctant to support their children in their education, my grandmother stepped in, using her authority as the elder of the family to overrule them. It was a delicious subversion of hierarchy—the youngest teaming up with the oldest to overrule the reluctant middle. If the parents wouldn’t pay for the children’s school, she would. If they needed a place to stay, she’d take them in.

This wasn’t limited to family. She informally “adopted” countless children—her own students, neighbors, distant relatives—and tutored them, guided them, paid for their tuition and school supplies. She convinced many parents to let girls continue on to high school or college.

When girls get married in Turkey, they are often gifted bracelets made of gold—to be used in emergencies or when savings are needed. My grandmother always said that education was the most important pair of “golden bracelets” that girls needed. “Get your golden bracelets” she would say all the girls she encountered, telling them that in a world dominated by men, women needed to make sure they could make a living if need be. To escape an abusive marriage. To support one’s own children. To deal with an illness. To be able to live a life on one’s own terms.

This is why educating girls is such strong leverage for social change: educated girls can grow into strong women who bring along and lead their families for generations, and can also shield and nurture their children and others as they can exercise choices. So my grandmother prayed to Ataturk and her teacher, the two people she believed made all this possible for her.

All three of her grandchildren moved abroad, something my grandmother greatly supported even as it caused her a lot of longing. She herself had worked for a telephone operator for a few years, and now the telephone became her most cherished possession, connecting her to us. She put her cellphone in a little pouch, and wore it as a necklace. In 2012, I had traveled to Kenya and visited some rural areas where I encountered elderly women with the same set-up: cell phones as necklaces. I asked one: “is this for your grandchildren?” She grinned. It was the same story: her grandchildren had migrated away searching a better life. She wanted them to go, but didn’t want to lose them. The telephone connected them.

After most phone conversations—which we had often, even as her memory failed—my grandmother would say, “May [Alexander Graham] Bell rest in peace. May he be accepted to the best corner of heaven. May his soul be blessed”, and so on. At first, she hadn’t wanted to talk on the phone much, thinking it was expensive. I finally convinced her how cheap it had become, and she took to it, chatting with me at length. She was enormously grateful, and she had a name to thank for all this: so Bell got all the blessings.

But we didn’t just talk on the phone, of course. In 2004, when I was finally graduating with my doctorate, I wanted to skip the ceremony—I had skipped every graduation ceremony before that. One friend said “this one is not for you; it’s for everyone who helped you along the way.” The phrase struck me hard it was the truest thing I had heard. I arranged for her to attend my dissertation defense as well as the graduation. I was nervous that it would be hard for her. I met her at the plane’s gate. She walked out of the jet bridge, chatting—somehow, in her broken English—with the cabin crew. She had apparently invited all of them to dinner. After educating people, she most loved feeding them.

By the time a Ph.D. student is allowed to defend, it is mostly understood that she should be able to pass, but the “oral examination” part is not just a rubber-stamp. It is a multiple- hour process in which the committee members grill the student. My defense was also scheduled right at lunch time. I didn’t really need to read the research to know that leaving your interrogators hungry was not the best idea.

My grandmother, now staying with me in the United States, had been itching to be useful. I asked her to cook some Turkish finger-food for my committee to eat during the defense. Not only would they not be hungry as they listened to my presentation of my dissertation, they would be eating afterwards. More chewing, less questioning.

So my grandmother sat through my defense which lasted maybe three hours or so, the many types of food she cooked on the table. She didn’t understand anything I was saying--she spoke only a few words of English. But she didn’t seem bored at all. A lot had happened along the way for her and for me to get here.

If it sounds like I’m drawing a picture of an ideal family—a lovely grandmother, a granddaughter who gets an education—the truth is far from it. It’s exactly because things went so wrong that my grandmother’s “golden bracelets” were so important.

My mother had been a non-functional alcoholic, and my father abandoned me and my brother to our alcoholic mother when we were young teens. Consequently, I was borderline to actual homeless throughout much of my teen years. It was a complicated crisis, and to allow my mother to have a house to live, my grandmother left hers to my mother, and moved into an assisted living facility. Hence, I could not live with my grandmother anymore, nor could I really live with my mother. It was a tough time, and grandma helped me immensely as I managed to ground myself, finding a job as a computer programmer and going on from there. Without her ability to help me and my brother through, we may never have made it out. My mother eventually died from her alcoholism. To great trauma to my grandmother, she was the one who found her daughter’s lifeless body. “I would not wish this upon the worst person in the world”, she said of her pain.

Addiction is a curse from hell, and I still have not fully grasped what happened. Neither has my grandmother. We just say she was ill with a fever we don’t understand. My mother struggled; she quit multiple times but always succumbed again. We watched her spiral down, and then we lost her. My mother saw me start my PhD, but didn’t make it to see me graduate.

My grandmother sat through my defense with an intense look on her face, beaming when anyone ate any of their food. I got asked fairly few questions, which I credit to her food.

After a defense, the standard procedure is to invite the doctoral candidate to step out and for the committee members to confer among each other whether she passed or not. The candidate is then invited back in, and the decision is announced. So I concluded my defense, the questioning ended, and we all stepped out.

The chair of my committee called us back, smiling, nodding approvingly. I smiled, too, and braced myself to accept the congratulations. He indeed said “congratulations”, but not to me. The whole committee turned to my grandmother, first congratulating her, and then standing up and applauding her. I was stunned: I had not set this up. I wish I could have been so smart and thoughtful to set it up. I had mentioned her story to a few people. To their credit, my committee had recognized the hero in the room. My grandmother, too, was stunned but she grasped that she was being recognized. Everyone went and hugged her as she wept.

For the rest of her life, my grandmother told this story to pretty much everyone she met. When I visited her at the assisted living facility for the next decade—where she loved living as it gave her independence—even the janitors would greet me as the granddaughter who had gone to the United States to get a doctorate, and whose committee had applauded my grandmother. She told this story to people she sat next to in the ferry; she told this to anyone who asked her about her life. I never tired of it; it was the only context in which being called a “doctor” meant something personal. I never use the title otherwise, except to joke in planes when they ask if there is a doctor on board. (“Not unless you need a literature review in aisle three.”)

I didn’t know what I would find last week, after her stroke. It was not as bad as I had feared, but she had clearly lost a lot of her stories. She appeared to have forgotten my grandfather’s death. She’d ask where he was, and we’d say “oh, soccer match”—as my grandfather would often go to soccer matches—and she’d say “oh, okay.” It was sad, but it felt merciful.

I wasn’t as ready, though, when she asked where my mother was, apparently also forgotten her death. “She’s out shopping”, I stuttered. “Oh, okay”, my grandmother said, unperturbed.

She had forgotten the worst event of her life.

We chatted mostly about lighthearted topics, since her past was mostly gone. We chatted about her room, and how she liked her pillows. She wanted one more to be able to sit upright better, so I got her one. True to form, she worried when I left to fetch a pillow. She was always fine with me globetrotting, but if I were visiting her, she didn’t want me out of her sight. It was her quirk. We chatted about my brother, even arranged a video call with him, to my grandmother’s delight.

I brought up the story of my doctoral dissertation defense. I expected she would have forgotten it, too—if my mother’s death was forgotten, I assumed everything else must be gone, too.

Do you remember, I said, how you traveled to my defense, and how you cooked food, and how everyone loved eating it, and how everyone stood up and applauded you.

“And how I cried”, she responded, mimicking tears falling down her face with her fingers. She smiled at me, and said it had been wonderful. There was no mistaking it, somehow, that memory had survived.

Her room at the assisted living facility was just as I had seen it for the past few decades: pictures of Ataturk, the founder of the Republic of Turkey, adorned the walls. There were also lots of pictures of her grandchildren and her great-grandchildren. I saw her cell phone in its necklace pouch, hanging on the wall.

I also found lots of notebooks in her room, and realized that she had been writing a lot notes to herself as her memory had gradually failed, long before the stroke. There would be a date and an entry “My son went on a trip to Italy; he will be back on Wednesday” it would say. I knew she wrote that so she wouldn’t worry if he didn’t call. She noted when my brother or I called or visited her. She also collected clippings of my articles or interviews with me.

I flipped through the pages of her notebooks and saw an entry that was repeated, again and again, with some variation. “Zeynep became a professor” one said. “Zeynep was promoted to a professor.” “Zeynep is in the United States and she is a professor.” So it went. It was on many pages. It was on loose pieces of paper. It seemed to infuse the room.

I looked at dates and pieced together what must have happened. I called her quite often, and it seemed like she often wrote this down to herself every time after we chatted on the phone. She had gotten an education—against all odds—and had leveraged it to make a life as best she could for everyone she loved, and that was her achievement in life. She wasn’t just proud of me; she was proud of herself. She had deserved that applause, and she knew she deserved it.

Her notes to herself made sense in of what had happened: she didn’t dwell on the tragedies, and she hadn’t reinforced the painful memories. Instead, she had focused on the positives: her own education, her grandchildren. After phone conversations, she wrote reminders to herself: things had turned out okay.

I left Istanbul, relieved she was not unhappy or in pain, but also with a deep sense of loss. For the past decade, she had been preparing me: telling me that she was content, and ready for whatever came next.

The republic that her life was so intertwined with, too, is now undergoing a transformation, and one that I am increasingly disconnected from. It’s not possible to avoid the sense of loss, both personal and political.

But there are lessons, too, also for both.

Educate the girls. Call your elderly loved ones. And write down your good memories.

May 19, 2022

A move, some news, and a new essay on privacy and technology in a post-Roe America

A few quick updates. I have been granted tenure at Columbia, and decided to accept a job there. This is bittersweet, as it means I am leaving the University of North Carolina to become a professor at Columbia University. My experience at UNC was largely positive, and especially my colleagues at the School of Information and Library Science, as well as the The Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life (CITAP), have been wonderful.

I was also a Pulitzer finalist this year! That one was a surprise. I’m genuinly thrilled—it’s the first year I was ever nominated.

I’ve been doing some of my usual writing (can be found here) on many aspects of the pandemic, but I’ve also just written an essay about the many ways in which technology, privacy and reproductive rights will continue to intersect—especially in a post-Roe America.

This new piece is centered around the basic insight, over a century-old, that new technology requires updating our laws and regulations and norms, just to keep our foundational rights to liberty and privacy in place.

Over 130 years ago, a young lawyer saw an amazing new gadget and had a revolutionary vision — technology can threaten our privacy.

“Recent inventions and business methods call attention to the next step which must be taken for the protection of the person,” wrote the lawyer, Louis Brandeis, warning that laws needed to keep up with technology and new means of surveillance, or Americans would lose their “right to be left alone.”

Decades later the right to privacy discussed in that 1890 law review article and Brandeis’s opinions as a Supreme Court justice, especially in the context of new technology, would be cited as a foundational principle of the constitutional protections for many rights, including contraception, same-sex intimacy and abortion.

Now the Supreme Court seems poised to rule that there is no constitutional protection for the right to abortion. Surveillance made possible by minimally-regulated digital technologies could help law enforcement track down women who might seek abortions and medical providers who perform them in places where it would become criminalized. Women are urging one another to delete phone apps like period trackers that can indicate they are pregnant.

But frantic individual efforts to swat away digital intrusions will do too little. What’s needed, for all Americans, is a full legal and political reckoning with the reckless manner in which digital technology has been allowed to invade our lives. The collection, use and manipulation of electronic data must finally be regulated and severely limited. Only then can we comfortably enjoy all the good that can come from these technologies.

I found the graphic by Ard Su that accompanied the piece to be quite striking:

One particular reason I wrote a lengthy piece with many details is that I don’t think most people are aware of how much new technologies can do—and that none of the suggested options, like not using certain products, using phones behind, requiring anonymized datasets (they can often be de-anonymized to identify individuals!), having opt-out options, etc. work well in practice. Further, this kind of surveillance isn’t just available to law-enforcement: vigilantes, too, may well start hunting down women in states where abortion may soon be criminalized.

After the Supreme Court’s draft opinion that could overturn Roe was leaked, the Motherboard reporter Joseph Cox paid a company $160 to get a week’s worth of aggregate data on people who visited more than 600 Planned Parenthood facilities around the country. This data included where they came from, how long they remained and where they went afterward. The company got this location data from ordinary apps in people’s phones. Such data is also collected from the phones themselves and by cellphone carriers.

That this was aggregated, bulk data — without names attached — should be of no comfort. Researchers have repeatedly shown that even in such data sets, it is often possible to pinpoint a person’s identity — deanonymizing data — by triangulating information from different sources, like, say, matching location data on someone’s commute from home to work, or their purchases in stores. This also helps evade legal privacy protections that apply only to “personally identifiable information” — records explicitly containing identifiers like names or Social Security numbers.

For example, it was recently revealed that Grindr, the world’s most popular gay dating app, was selling data about its users. A priest resigned after the Catholic publication The Pillar deanonymized his data, identified him and then outed him by tracking his visits to gay bars and a bathhouse.

Phone companies were caught selling their customers’ real-time location data, and it reportedly ended up in the hands of bounty hunters and stalkers.

I think, in particular, the growing powers of machine learning, which can infer conclusions that aren’t explicitly in the data, are underestimated and not very-well understood.

For example, algorithmic interpretations of Instagram posts can effectively predict a person’s future depressive episodes — performing better than humans assessing the same posts. Similar results have been found for predicting future manic episodes and detecting suicidal ideation, among many other examples. Such predictive systems are already in widespread use, including for hiring, sales, political targeting, education, medicine and more.

Given the many changes pregnancy engenders even before women know about it, in everything from sleep patterns to diet to fatigue to mood changes, it’s not surprising that an algorithm might detect which women were likely to be pregnant. (Such lists are already collected and traded). That’s data that could be purchased by law enforcement agencies or activists intent on tracking possible abortions.

Many such algorithmic inferences are statistical, not necessarily individual, but they can narrow down the list of, well, suspects.

How does it work? Even the researchers don’t really know, calling it a black box. How could it be regulated? Since it’s different, it would need new thinking. As of yet, few to no laws regulate most of these novel advances, even though they are as consequential to our Fourth Amendment rights as telephones and wiretaps.

As usual, I remain an optimist that solutions exist, and are possible. I’m not as optimistic that we will do the required political and technical work necessary to make them a reality, but at least, we can try.

March 12, 2022

Sorry! Correction! 3/12

Apologies for cluttering your inbox. I’m on the road today and sent the wrong draft, thus did not include the link to my counterfactual pandemic piece and had a few typos. Sorry! 😬

Here’s the corrected opening paragraph:

For the second anniversary of the pandemic, I wrote a counterfactual history of some of the key early turning points: accepting transmission without symptoms, recognizing airborne spread, the importance of clusters, and the need to increase vaccine supply and distribute it equitably. There is, obviously, more but it’s already a lengthy article.

(Web link with the rest here).

Open Thread 3/12/22: Guns of August Edition

For the second anniversary of the pandemic, I wrote a counterfactual history of some of the key early turning points: accepting transmission without symptoms, recognizing airborne spread, the importance of clusters, and the need to increase vaccine supply and distribute it equitably.There is, obviously, more, but it’s already a lengthy article. Plus, early action obviously is crucial, as well as vaccination as fast and as widely as possible.

Why do this exercise and how does this differ from Monday Morning Quarterbacking, so to speak? Also, why not write more about the political and institutional dysfunction that made these outcomes happen?

We cannot step into the same river twice, the Greek philosopher Heraclitus is said to have observed. We’ve changed, the river has changed.

That’s very true, but it doesn’t mean we can’t learn from seeing what other course the river could have flowed. As the pandemic enters its third year, we must consider those moments when the river branched, and nations made choices that affected thousands, millions, of lives.

What if China had been open and honest in December 2019? What if the world had reacted as quickly and aggressively in January 2020 as Taiwan did? What if the United States had put appropriate protective measures in place in February 2020, as South Korea did?

To examine these questions is to uncover a brutal truth: Much suffering was avoidable, again and again, if different choices that were available and plausible had been made at crucial turning points. By looking at them, and understanding what went wrong, we can hope to avoid similar mistakes in the future.

I tried, as best I could, to provide real-time actual examples of countries that did act quickly and correctly based on emerging evidence—countries like Taiwan, South Korea, Japan and such.

Also, even though epidemics are easier to suppress with early action, it’s silent spread and superspreading that make a timely response even more important, as shown by South Korea’s early response.

South Korea experienced major superspreading events in February 2020, including one in a secretive church that accounted for more than 5,000 infections, with a single person suspected as the source. The country had the highest number of cases outside of China at that point.

South Korean officials sprang into action, rolling out a mass testing program — they had been readying their testing capacity since January — with drive-through options and vigorous contact tracing.

South Korea beat back that potentially catastrophic outbreak, and continued to greatly limit its cases. They had fewer than 1,000 deaths in all of 2020. In the United States, that would translate into fewer than 7,000 deaths from Covid in 2020. Instead, estimates place the number of deaths at more than 375,000.

The value of a counterfactual is that by showing a plausible, possible alternative path, it sets a goal and a path. I encounter a lot of “there isn’t anything else possible”—a limited imagination is a way of ensuring limited change. It fuels despair, understandably, when we should be outraged, but in a productive way. Outraged to change things.

On the political dysfunction: much has been written about it already, by many others. Occasionally, I do too. How to move forward despite it, and also while addressing it, is not an easy question whatsoever—and that is an understatement, obviously, to the depth of the challenge.

But there are two things to add here. One, Trump’s massive, negative impact on the first year of the pandemic in the United States is obvious. But it wasn’t just the United States that failed in ways, say, South Korea which was quite unlucky with early major superspreading events did not. Many countries, including many in Western Europe not ruled by incompetent wanna-be authoritarians failed in similar ways.

Plus, even in the United States, it wasn’t just Trump, as terrible as his administration was. It is a difficult truth, but many of our liberal institutions and key public health officials, many of whom did not work for Trump and thus were free to say what they wanted, made pronouncements and gave and promoted advice that turned out to be very wrong, and contrary to evidence. Were they well-meaning? I don’t doubt that part. We still need to do better, though. (Free article idea: tracing the first three-four months of the United States response, but not just Trump.)

Back to the counterfactual: the point is to figure out what was possible so that we can have a broader view of why those roads weren’t taken, exactly so that maybe, just maybe, we can learn and do better next time—not just for a pandemic, but clearly, the broad degradation of how our societies function. It’s so apparent over the past few decades: many things that became even more possible thanks to wealth, technology and science have become worse in their functioning. But that exact wealth, technology and science make it possible to turn this around.

Meanwhile, on a related note to this moment, I’m going to recommend two amazing books for this moment, both by the great historian Barbara Tuchman.

First is Guns of August: The Outbreak of World War I, tracing the initial month of World War One, setting in place dynamics that would define the first half of the 20th century, arguably also the 1918 pandemic. (Non-affiliate links).

The second one March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam, a history of societies that failed because the elites did not take actions that were plausible, available, rational and even in their self-interest.

My most sincere wish is that we stop writing an additional chapter to that book.

(Note: updated with link! Sorry, on the road today!)

January 5, 2022

Open Thread: Here's Hoping We Don't Need Luck As Much in 2022, 1/5/2022 edition.

It’s a new year! Let’s start with the good news!

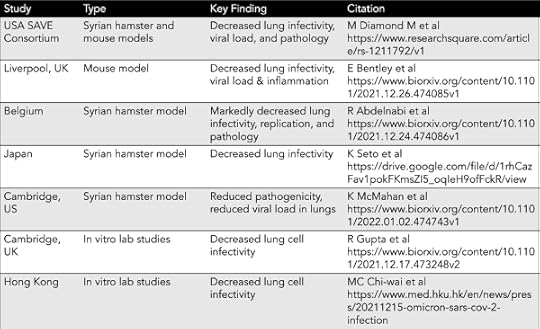

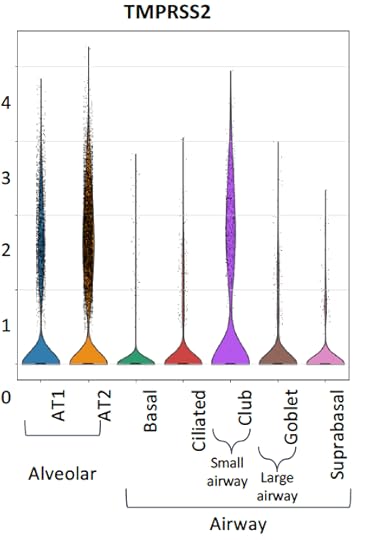

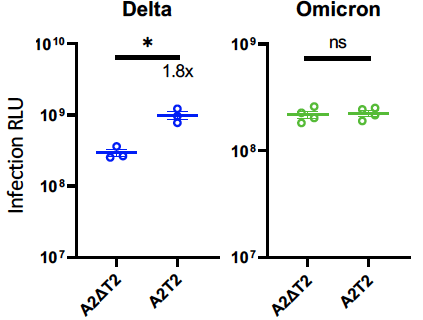

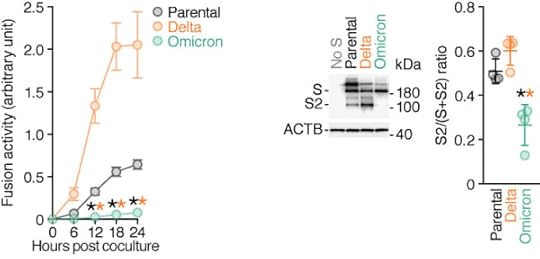

There are now seven independent lab studies showing that Omicron is less infective in the lower lungs. Here’s a compilation from Eric Topol (who is on substack!).

biorxiv.org/content/10.110… Updated summary table ","username":"EricTopol","name":"Eric Topol","date":"Tue Jan 04 18:10:44 +0000 2022","photos":[{"img_url":"https://pbs.substack.com/media/FIRuUc... Eric Topol @EricTopolNow 7 studies for Omicron's reduced lung infectivity, viral load, inflammation and overall pathogenicity (5 in vivo models, 2 lab). New in vivo model report link: biorxiv.org/content/10.110… Updated summary table

Eric Topol @EricTopolNow 7 studies for Omicron's reduced lung infectivity, viral load, inflammation and overall pathogenicity (5 in vivo models, 2 lab). New in vivo model report link: biorxiv.org/content/10.110… Updated summary table

January 4th 2022

651 Retweets2,031 LikesThat’s great news because low lung infectivity is associated with being less able to cause more severe disease.

And while this variant can clearly cause a lot of breakthrough symptoms, immunity from vaccines or prior infection is holding up very well, too. (This is something we’d expect, but we could have gotten really unlucky and had severity escape as well—so far, no such sign).

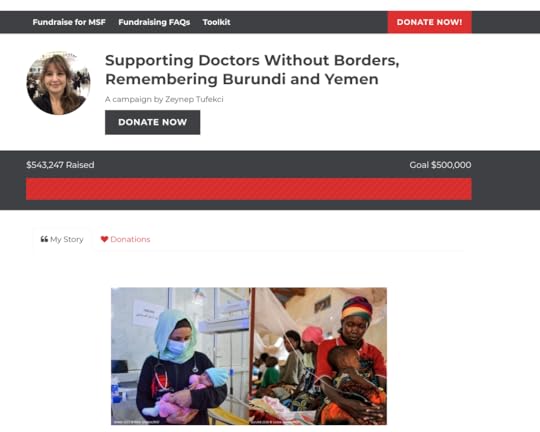

And in other good news, my Doctors Without Borders fundraiser supporting their work especially in places like Yemen and in Burundi managed to raise more than half a million dollars! So much gratitude to everyone who participated, but especially to healthcare workers around the world working so hard, often with too little, to help others.

a.image2.image-link.image2-879-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 120.74175824175823%; padding-bottom: min(120.74175824175823%, 879px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-879-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 879px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-879-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 120.74175824175823%; padding-bottom: min(120.74175824175823%, 879px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-879-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 879px; } Now the bad news.

First, we still need Doctors Without Borders fundraisers to deliver basic health-care and food-aid during a famine. I believe in fundraising because we must, but I yearn for a day this is seen as a quaint, weird hobby.

Second, we are still relying on getting lucky with variants to skate through the pandemic.

I examine all this in my column today in The New York Times, especially in the context of CDC’s zigzag around the rapid tests and N95s, where we see my least favorite friends from the first-year-of-pandemic make an appearance: namely, denigrating of usefulness of tools simply because we don’t have enough even though we should have, and waving around claims of false sense of security to justify not empowering the public.

Consider below comparing statements of CDC director Dr. Walensky made recently with those of the scientist and public health advocate Dr. Walensky of 2020:

“We opted not to have the rapid test for isolation because we actually don’t know how our rapid tests perform and how well they predict whether you’re transmissible during the end of disease,” Walensky said on Dec. 29. “The F.D.A. has not authorized them for that use.”

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the president’s chief medical adviser, argued the same, also on Dec. 29. Referring to antigen tests, he said, “If it’s positive, we don’t know what that means for transmissibility” and that these antigen tests aren’t as sensitive as P.C.R. tests.

Might the real reason be that rapid tests are hard to find and expensive here (while they are easily available and relatively cheap in other countries)?

Is it possible that rapid tests are a good way to see who is infectious and who can return to public life — and their lack of sensitivity to minute amounts of virus is actually a good thing? Let’s ask a brilliant scientist and public health advocate — Rochelle Walensky, circa 2020.

Walensky, who was then on the faculty of the Harvard Medical School and chief of the division of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital, was a co-author of a paper in September 2020 that declared that the “P.C.R.-based nasal swab your caregiver uses in the hospital does a great job determining if you are infected but it does a rotten job of zooming in on whether you are infectious.”

She was so on the money with every aspect of this that I can’t resist quoting even more from her 2020 article on all this:

That’s right, the key question is who is infectious, who can pass on the virus, not whether someone is still harboring some small amount of virus, or even fragments of it. P.C.R. tests can detect such tiny amounts of the virus that they can “return positives for as many as 6-12 weeks,” she pointed out. That’s “long after a person has ceased to pose any real risk of transmission to others.” P.C.R. tests are a bit like being able to find a thief’s fingerprints after he’s left the house.

So what did 2020 Walensky recommend? “The antigen test is ideally suited to yield positive results precisely when the infected individual is maximally infectious,” she and her co-author concluded.

The reason is that antigen tests respond to the viral load in the sample without biologically amplifying the amount and being able to detect even viral fragments, as P.C.R. tests do. So a rapid test turns positive if a sample contains high levels of virus, not nonviable bits or minute amounts — and it’s high viral loads that correlate to higher infectiousness.

What about the objection that rapid antigen tests don’t always detect infections as well as P.C.R. tests can?

The 2020 Walensky wrote that the F.D.A. shouldn’t worry about “false negatives” on rapid tests because “those are true negatives for disease transmission” — meaning that people are unlikely to spread the virus even if they have a bit of virus lingering. In other words, the fact that rapid tests are less likely to turn positive if the viral load isn’t high is a benefit, not a problem.

And here’s more on the false sense of security playing a role on all this—the idea that will not go away even if there is no evidence for it.

The threat of a “false sense of security” has been used against everything from seatbelts to teaching young kids how to swim (because that would supposedly encourage parents to stop watching their children in the water!). Research and common sense shows what one would expect: Safety measures make people safer and people who choose to use them are looking to be safer — if anything, they do more of everything. (Parents should watch their young children in the water, but kids who learn to swim are less likely to drown.)

That’s why it was extra disappointing to hear Walensky argue recently that “if you got a rapid test at five days and it was negative, we weren’t convinced that you weren’t still transmissible. We didn’t want to leave a false sense of security. We still wanted you to wear the mask.”

Ugh. All of this is so reminiscent of public health officials and health journalists claiming wearing masks would “cause” a false sense of security (and make people ignore washing their hands!) in 2020.

Aesop’s fable on the Fox and the Grapes has entered the chat, too!

Aesop's Fables: PhaedrusBook IV - III. De Vulpe et Vua (Perry 15)

Fame coacta uulpes alta in uinea

uuam adpetebat, summis saliens uiribus.

Quam tangere ut non potuit, discedens ait:

"Nondum matura es; nolo acerbam sumere."

Qui, facere quae non possunt, uerbis eleuant,

adscribere hoc debebunt exemplum sibi.

The Fox and the Grapes (trans. C. Smart)

An hungry Fox with fierce attack

Sprang on a Vine, but tumbled back,

Nor could attain the point in view,

So near the sky the bunches grew.

As he went off, "They're scurvy stuff,"

Says he, "and not half ripe enough--

And I 've more rev'rence for my tripes

Than to torment them with the gripes."

For those this tale is very pat

Who lessen what they can't come at.

The masks that we didn’t have enough of weren’t useful for the public anyway in 2020, and now it’s the tests we don’t have enough of which are suddenly sour and not that ripe!

I also want to highlight this bit from Katherine Eban’s excellent article in the Vanity Fair on why the White House rejected the proposal to acquire a large number of rapid tests in time for the holiday season, where a version of “false sense of security” rears its head again:

Three experts who interacted with the White House came to believe that the Biden administration had deprioritized rapid testing, partly out of concern that people would opt for that instead of getting vaccinated. As one expert put it, “It was clear they felt that people who didn’t want to get vaccinated might like no-strings-attached rapid testing.”

I have to say, this is more than a bit disappointing. We don’t have enough tests because someone bought into baseless pop-psychology on how better is worse?

Those who are looking for an excuse to avoid vaccination do exist, but there’s no reason to think they just won’t find yet another reason if rapid tests weren’t available to them, and absolutely no reason to deny the rest of us useful tools based on this kind of theorizing—I see no evidence to think this is even true.

So, here are my two proposed laws, going forward.

@murchiston @avizvizenilman Zeynep's law: Until there is substantial and repeated evidence otherwise, assume counterintuitive findings to be false, and second-order effects to be dwarfed by first-order ones in magnitude.","username":"zeynep","name":"zeynep tufekci","date":"Wed Jan 05 16:32:40 +0000 2022","photos":[],"quoted_tweet":{},"retweet_count":19,"like_count":88,"expanded_url":{},"video_url":null}"> zeynep tufekci @zeynep@murchiston @avizvizenilman Zeynep's law: Until there is substantial and repeated evidence otherwise, assume counterintuitive findings to be false, and second-order effects to be dwarfed by first-order ones in magnitude.

zeynep tufekci @zeynep@murchiston @avizvizenilman Zeynep's law: Until there is substantial and repeated evidence otherwise, assume counterintuitive findings to be false, and second-order effects to be dwarfed by first-order ones in magnitude.January 5th 2022

19 Retweets88 Likes zeynep tufekci @zeynepAka if your particle is going faster than light, check your cables first, and if you are arguing "what if better is worse", check your thinking and do some more research before doubling down.

zeynep tufekci @zeynepAka if your particle is going faster than light, check your cables first, and if you are arguing "what if better is worse", check your thinking and do some more research before doubling down. zeynep tufekci @zeynep

@murchiston @avizvizenilman Zeynep's law: Until there is substantial and repeated evidence otherwise, assume counterintuitive findings to be false, and second-order effects to be dwarfed by first-order ones in magnitude.January 5th 2022

19 Retweets110 LikesTreat the public like adults and partners, and work to empower them—even if some portion isn’t listening to the advice, or even if some are actively hostile. Seems straightforward enough, and yet we still struggle with it.

If anything, the existence of that hostile portion makes it even more important to empower and respect those of us looking to public health authorities for guidance, tools and infrastructure.

Here’s to hoping we will need less luck in 2022.

December 26, 2021

Convergent Evidence, Omicron Edition. Open Thread 26/12/2021

It's the holiday season for many people! I hope it is joyous and happy for you and yours..

This is the best Omicron update I have yet, but first, a brief announcement.

But if you don’t want to read all the way, here’s the two big items in tl;dr form.

I’m doing a Doctors Without Borders donation drive: I’m matching up to $20K, and others have stepped up so up to $58K in donations is matched! If you’d like to support it, here’s where to contribute: https://events.doctorswithoutborders....

There is convergent evidence that for vaccinated and or/prior infected people—the seropositives—the defenses against severe disease or worse for Omicron are holding up fairly well and that Omicron itself may be causing less severe disease, and is not as good at replicating in a manner that causes the illness to progress to severity and invade the lower respiratory system. (Note! These are two separate mechanisms! The news is encouraging on both fronts!) The first is a lot more firm, the second is emerging evidence, and neither means we can ignore the situation. IT IS STILL SERIOUS. But yes, I believe that more and more of the worst case scenarios are off the table.

Happy holidays! Now the details on both.

A few years ago, I did a donation drive for Doctors Without Borders, supporting their work in Yemen which was facing war, famine and disease at the same time—as it often happens.

@MSF_USA. events.doctorswithoutborders.org/campaign/zeynep ","username":"zeynep","name":"zeynep tufekci","date":"Fri Dec 16 22:25:00 +0000 2016","photos":[{"img_url":"https://pbs.substack.com/media/Cz1L0t... zeynep tufekci @zeynepYemen: Millions of children are at risk of starving. I'm fundraising—matching donations up to $15,000 for @MSF_USA. events.doctorswithoutborders.org/campaign/zeynep

zeynep tufekci @zeynepYemen: Millions of children are at risk of starving. I'm fundraising—matching donations up to $15,000 for @MSF_USA. events.doctorswithoutborders.org/campaign/zeynep

December 16th 2016

464 Retweets387 LikesI had a hand-me-down 2001 Honda Civic, so I put the money I had saved to replace it as a match for donations. The campaign generated almost $250K, as people stepped up both to increase the match, and to donate.

Well, my Civic made it to 2021! It had other advantages as well, besides being oblivious to new scratches (who could tell!): as a stick-shift, it seemed like it was theft-proof. Here it is back then, in 2016:

a.image2.image-link.image2-504-680 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 74.11764705882354%; padding-bottom: min(74.11764705882354%, 504px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-504-680 img { max-width: 680px; max-height: 504px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-504-680 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 74.11764705882354%; padding-bottom: min(74.11764705882354%, 504px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-504-680 img { max-width: 680px; max-height: 504px; } It may be that thieves these days can only drive automatics. I never locked it, though when I did put my bike on it, I think its value quadrupled.

Here it is more recently, about to quadruple in value (note the bike rack!):

a.image2.image-link.image2-583-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 80.08241758241759%; padding-bottom: min(80.08241758241759%, 583px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-583-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 583px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-583-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 80.08241758241759%; padding-bottom: min(80.08241758241759%, 583px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-583-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 583px; } So this year, I’m doing another campaign. I’m signing my Civic over to a friend’s son, and not replacing it. It still runs, at 200K+ miles. But I am in New York at the moment, and not only do I not need to own a car, trying to park that thing would probably cost more than the car each month.

I’m once again putting the replacement cash towards Doctors Without Borders. I’m thus matching $20K in donations to Doctors Without Borders, this time in support of their work in Yemen and Burundi.

If you want to donate, here’s the link. If you want to add to the match, you can put that in the note field, email me, or direct message me on Twitter. We are now up to $58K in matching donations!

https://events.doctorswithoutborders.org/campaign/zeynepmatch2021

Here’s one Twitter thread about it:

zeynep tufekci @zeynepA few years ago, we did a campaign to raise money in support of Doctors without Borders. I'm doing another one, supporting their work in Yemen and in Burundi. I'll match $20,000 in donations. Here's the link to donate, to join me or to raise the match!

zeynep tufekci @zeynepA few years ago, we did a campaign to raise money in support of Doctors without Borders. I'm doing another one, supporting their work in Yemen and in Burundi. I'll match $20,000 in donations. Here's the link to donate, to join me or to raise the match!

zeynep tufekci @zeynep

Yemen: Millions of children are at risk of starving. I'm fundraising—matching donations up to $15,000 for @MSF_USA. https://t.co/jQ8P9X6ANq https://t.co/SlMMtK8DO0December 23rd 2021

233 Retweets527 LikesAnd here’s another Twitter thread about why I do these fundraisers—and why I wish we didn’t have to.

@Craig_A_Spencer, who survived Ebola in 2014, is working tonight.\n\nI asked him for his pics from Burundi, for my MSF fundraiser.👇\n\nHere's why they sucked—and why that matters.🧵\nevents.doctorswithoutborders.org/campaign/zeyne…","username":"zeynep","name":"zeynep tufekci","date":"Sat Dec 25 02:11:45 +0000 2021","photos":[],"quoted_tweet":{},"retweet_count":72,"like_count":348,"expanded_url":{"url":"https://events.doctorswithoutborders.... Tufekci","description":"A fundraising page for Zeynep Tufekci","domain":"events.doctorswithoutborders.org"},"video_url":null}"> zeynep tufekci @zeynep'Twas the night before Christmas, and like many exhausted healthcare workers, @Craig_A_Spencer, who survived Ebola in 2014, is working tonight.I asked him for his pics from Burundi, for my MSF fundraiser.👇Here's why they sucked—and why that matters.🧵events.doctorswithoutborders.org/campaign/zeyne…

zeynep tufekci @zeynep'Twas the night before Christmas, and like many exhausted healthcare workers, @Craig_A_Spencer, who survived Ebola in 2014, is working tonight.I asked him for his pics from Burundi, for my MSF fundraiser.👇Here's why they sucked—and why that matters.🧵events.doctorswithoutborders.org/campaign/zeyne… Zeynep TufekciA fundraising page for Zeynep Tufekcievents.doctorswithoutborders.org

Zeynep TufekciA fundraising page for Zeynep Tufekcievents.doctorswithoutborders.orgDecember 25th 2021

72 Retweets348 LikesYemen has been suffering from profound hunger, a terrible war, and lack of healthcare for five years now, and now the effects of the pandemic. Only about 1% of the population is vaccinated, and COVID, as terrible as it is, is not the highest challenge they face. The UN Food Program just announced they are cutting food aid to the country—not enough money. Burundi faces similar challenges: the pandemic came at an already fragile moment, adding to their many crises. Doctors Without Borders is one of the organizations that is on the ground in many such places and employs a lot of local staff. Ideally, we would not need these life-vests, the NGO work—ideally, the boat would be built better so it wouldn’t sink. But once people are in the water, the only right thing to do is to respond, even if we work to make such interventions less necessary, in the future.

Onward to Omicron!

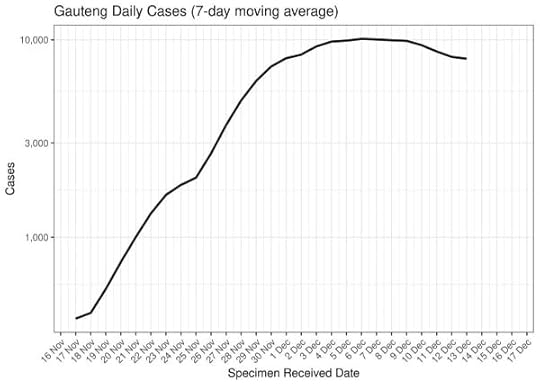

So, first: data from Gauteng, South Africa and the United Kingdom and Denmark, and the situation on-the-ground here in New York all add to the same picture. Omicron is wildly good at spreading, and will infect and re-infect many people who are vaccinated or had prior infections, but is not generating a proportional uptick in hospitalizations or death among populations with high combined vaccination rates and prior outbreaks. (The seropositives: people who had prior infections or vaccination!)