Adrian Tannock's Blog

December 19, 2016

Money Money Money

Dystopian fiction and money. The two go hand in glove. We’ll look at this in more detail. But first, a quick word from everybody’s favorite Professor, Stephen Hawking, in the press this week detailing his adventures in zero-gravity.

An adventurous soul, Hawking takes up daredevil opportunities whenever they arise. Variously, this has included visits to Antartica, traveling in a submarine, and even barreling‘down the steepest hills of San Francisco in my motorized wheelchair.’

Now there’s a Y...

November 28, 2016

Your Mind is Being HACKED (And There is Little You Can Do)

Science news. Researchers in Japan are working on a potential new treatment for phobias and PTSD. It’s pretty interesting. This new approach, called fMRI decoded neurofeedback (DecNef), uses computer algorithms to identify and desensitize traumatic memories.

How does it work? To begin, researchers installed traumatic memories into their subjects by associating certain colored shapes with unpleasant electric shocks. They would then, naturally, feel afraid when showed those images.

The subject...

November 21, 2016

Big Brother is Watching You (And Other Observations)

Big Brother is Watching You. Or at least, he soon will be. Here in the UK, Her Majesty’s Government has passed into law the Investigatory Powers Bill, otherwise known as the ‘Snooper’s Charter.’ It represents the largest expansion of surveillance powers in Western Europe, and according to Edward Snowden, it “It goes farther than many autocracies.”

The UK has just legalized the most extreme surveillance in the history of western democracy. It goes farther than many autocracies. https://t.co/y...

October 12, 2016

Monsters and Mayhem

In the swampland of darkest Denmark, a demon stirs. Its baleful eyes glow with malevolent light; its heart set on evil intent.

The monster storms the great mead hall, Heorot, ripping the door from its hinges. It tears one unfortunate limb from limb, devouring him ‘in huge mouthfuls, greedily gulping. In no time he has eaten him all, even the hands and feet.’

This demon stands impervious to ordinary swords. Only might – and a true heart – can defeat it. And only one man possesses such strengt...

September 28, 2016

What is Speculative Fiction?

When you think about it, the phrase speculative fiction seems quite redundant. After all, isn’t all fiction ‘speculative’? Even the most accurate historical novel, meticulously pieced together from surviving documents and photographs, must contain at least some speculation.

To some extent, the word ‘speculative’ sows the seeds of its undoing — it’s too ambiguous. Too open to interpretation. And, according to some, too pretentious. So, what does this all mean?

Speculative Fiction as a genre

As a genre definition, the term has been around for a long time. Author Robert A. Heinlein used it in the 1940s as synonymous with ‘science fiction.’ In the 1960s, a ‘New Wave’ of science fiction writers, keen to dissociate themselves from the so-called Sci-Fi Ghetto, started using it to describe their more experimental, literary work.

Over the years, speculative fiction has become an umbrella term for an array of speculative genres: science fiction, fantasy, horror; plus those sub-genres that combine elements of the above: dystopian, alternative history, historical fantasy, and similar.

(For a fuller discussion of which genres are and are not speculative fiction, try this post from author Annie Neugebauer. It has Venn diagrams and everything!)

The Anatomy of Speculative Fiction

While trying to get to grips with a term as ambiguous as this, it helps to recognize what isn’t considered speculative fiction. For instance, the submission guidelines for Third Person Press assert that stories which take place in the ‘real’ world as we know it, or an accepted historical past, it probably do not count. According to editor Sherry D. Ramsey, this stands true even if events ‘seem strange or supernatural but turn out to have a logical, scientific explanation.’

So speculative fiction cannot take place in the real world? Well, yes and no. Back to Annie Neugebauer, who gives this excellent example:

A movie in which two astronauts get lost in space isn’t speculative because it could really happen within the realm of our existing knowledge of the world, as terrifying as that may be. A movie in which a group of astronauts discover an alien life form is speculative because – according to our current knowledge – it couldn’t happen in real life, since we know of no other intelligent life forms. See the difference?

This is a great example because both scenarios are ostensibly ‘science fiction,’ but only one is speculative; only one demands the reader to transcend the possible and delve deeper into the human imagination. If fiction is about asking ‘what if?’ then speculative fiction is saying ‘yes, but really what if?’

What is Speculative Fiction good for?

Well, what is any fiction good for?

Is speculative fiction just a comforting fantasy? A way of self-medicating against the harsh realities of adulthood? Perhaps it can be, and there is nothing wrong with that. Who says we must lose our sense of wonder? Why must we meekly accept our tick-tock world of spreadsheets, responsibilities, and productivity?

Speculative fiction is a voyage into the impossible. It describes worlds that operate on different ‘laws’ to our own. The fully-realised world, customs, history, and language of Tolkien’s Middle Earth is written to be enchanting (although let’s not get into Tom Bombadil right now). It’s a workout for the imagination, and that can only be a good thing.

If you’ve ever read Iain M. Bank’s gnarly Culture novels, you’ll appreciate the humor and bombast of his settings. From cavernous spaceships, super-sized gas giants, and mind-expanding cities, it’s a place you would really enjoy exploring. Bank’s novels dazzle you with impossible detail; his imagination was incredible.

Even horror, which might not seem a natural environment for wonderment, can provoke this same sense of awe. Consider Pennywise, the antagonist from Steven King’s ‘It’. As you plumb the depths of depravity within this multidimensional creature, you can’t help but marvel at its abhorrent nature. Terrible, yes, but a marvel all the same.

It’s not all fun and games

However, speculative fiction isn’t just a playground for the imagination. Consider George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four; a classic dystopian novel published in 1949. Here, we’re invited to marvel at a different type of horror. Rather than stand aghast at an alien being, we’re confronted with humankind’s will to dominate all, no matter the cost.

In this world of doublethink — The Ministry of Peace orchestrates a perpetual war, The Ministry of Truth ‘rectifies’ history to support Big Brother’s narrative – the world around our protagonist reflects the conflict within us; our capacity for kindness, love, and compassion, but also hate, cruelty, and betrayal.

And this is a key point. Speculative fiction might create worlds that follow different rules to our own, and it might surprise us with the incredible and unexpected. But it also places us in front of a carnival mirror and asks us to consider our humanity. Speculative fiction asks hard questions. Who are we, really, and where are we heading?

Expand the parameters

All fiction is capable of asking hard questions, of course, but the questions – and answers — found in speculative fiction are rendered in stark, bold, and innovative ways. It is an exploration of the human imagination, splashed across the page in vivid temper. It allows us to plumb unimaginable depths – or soar to incredible highs – and consider the flaws, hopes, and dreams of ordinary people.

And, more often than not, we experience a damn good story in the process.

A fantastic journey

This fantastical journey into otherness is one of discovery. Like all heroic journeys, we arrive back home changed by our experience. Speculative fiction changes the way we understand the world — and ourselves. What stories have changed the way you look at yourself or the world around you? As Joseph Campbell wrote: ‘The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.’ And, in speculative fiction, that cave really is something to behold.

As Joseph Campbell wrote: ‘The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.’ And, in speculative fiction, that cave really is something to behold.

A request

Thoughts? Questions? Criticisms? Recommendations? If you have anything to add please submit your comment below. It’d be great to hear from you.

Also, if you enjoyed this post then please sign up for my VIP Reader’s club – you’ll get all the latest news, behind-the-scenes insights, exclusive offers, and more.

The post What is Speculative Fiction? appeared first on writezu.com.

September 7, 2016

Writing Scenes (Part 4) – Scene Structure

This series of posts explores all you need to know about writing scenes. We’ll consider topics such as Scene and Sequel*, cause and effect, scene goals, and more. Today’s post focuses on: scene structure.

* We’re using Scene and Sequel (capitalised, italics) when referring to these specific terms and ‘scene’ (no capitals or italics) to refer to scenes in general.

A recap on conflict…

We previously defined the term ‘scene’ by quoting author Jordan Rosenfeld: “Scenes are capsules in which compelling characters undertake significant actions in a vivid and memorable way that allows the events to feel as though they are happening in real time.”

This definition reminds us to slow things down, zoom in on the action, and savour the drama as presented on the page. Scenes are your story’s highlights. Maximise their impact.

The ‘microstructure’ of conflict

In the previous post, we looked at two different methods for organising the detail of conflict: Jack Bickham’s ‘Stimulus, Internalisation, and Response’ method, and Dwight Swain’s ‘Motivation – Reaction’ units. These patterns direct the reader’s focus in a logical way: something happens, a character processes it, and then reacts accordingly. This microstructure keeps things linear and organised and avoids confusing the reader.

For example, the following progression is flawed. The stimulus and response do not immediately make sense:

Mike entered.

(stimulus) John said, ‘hey, what’s up?’

(response) Mike hit John square on the nose.

Contrast this with Bickham’s method for organising conflict:

Mike entered.

(stimulus) John said, ‘hey, what’s up?’

(internalisation) I’ll show you what’s up, thought Mike.

(response) He hit John square on the nose.

Adding the ‘internalisation’ gives context to Mike’s actions. This helps with the flow of cause and effect, which, as we have seen, is woven through storytelling on every level. Paying attention to this keeps things organised.

Around in circles…

However, there’s more to conflict than the minutiae. If you’ve ever listened to an argument between children (or drunks! And if I’m honest I’m uncertain of the difference…) you’ll know how irritating circular ‘it’s your fault’ / ‘no it’s your fault’ conflict can be.

Organising the microstructure of conflict combats this to some extent, but we still need to make sure the conflict goes somewhere. Repetitive arguments are dull and pointless. Matters have to develop to a satisfying conclusion.

Let’s consider the bigger picture: how should your story ebb progress each scene?

The origins of the 3-act structure

In her excellent book ‘Secrets of Screenplay Structure’, Linda Cowgill traces our understanding of the three-act structure back to Aristotle’s work ‘The Poetics’. Although an essay on the Greek tragedy, these principles also apply to drama:

‘A whole is that which has a beginning, a middle, and a conclusion. A beginning is that which itself does not of necessity follow something else, but after which there naturally is, or comes into being, something else. A conclusion, conversely, is that which itself naturally follows something else, either of necessity or for the most part, but has nothing else after it. A middle is that which itself naturally follows something else, and has something else after it. Well-constructed plots should neither begin from a random point nor conclude from a random point, but should use elements we have mentioned (i.e., the beginning, middle and conclusion.)’

—Aristotle, Poetics (translated by Richard Janko).

It’s worth picking through this slab of text to understand it fully. Aristotle suggests a whole story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end, where one flows into the next. To Aristotle, events within a story should not be coincidental or irrelevant; they should build towards a dramatic and satisfying conclusion. This is cause and effect once more.

Rising tensions over three acts

To Cowgill, the journey from dramatic question to dramatic climax should be one of rising tension. To begin, then, you must first pose a dramatic question. Similarly, story beginnings often deliver exposition – the information we need to fully grasp the story. This is our starting point.

From there, we encounter what Aristotle called complications. This includes important plot moments such as the reversal and the recognition – those moments where the protagonist gains knowledge and insight, leading to love or enmity between the story’s players.

As we approach the end of the story, tensions and drama continue to rise, leading us to the story’s climax. The protagonist’s problems must be solved – or not – in a way which brings about a resolution to the story. The dramatic question is answered, one way or another.

As above, so below

This journey, as sketched out above, gives us a basic 3-act structure. John York, in his book Into the Woods (2013), argues that this structure of beginning, middle, and end is not only found across whole stories and acts, but also within scenes themselves. He writes that scenes “mimic exactly an archetypal story shape”, and contain a set-up, a crisis, a climax and resolution.

To give your scenes shape, and therefore avoid circular, repetitive conflict, it seems important to pay attention to scene structure. Let’s look at another way of organising this.

The 8 point arc

You always come into the scene at the last possible moment.” —WILLIAM GOLDMAN

Click To Tweet

The late Nigel Watts (Teach Yourself: Writing a Novel) steps out a slightly different way of organising story events. He called it ‘the eight-point arc’:

• Stasis: once upon a time

• Trigger: something out of the ordinary happens

• Quest: causing the protagonist to seek something

• Surprise: but things don’t go as expected

• Critical Choice: forcing the protagonist to make a difficult decision

• Climax: which has consequences

• Reversal: the result of which is a change in status

• Resolution: and they all lived happily ever after (or didn’t)

Watts, echoing York, suggest this arc can be found within scenes, acts, and whole stories. It does seem to correspond to the 3-act structure. We know that Scenes begin with the POV-character’s pursuit of their goal (the quest) and end with a turning point (the character makes a critical choice, which leads to the climax).

It makes sense that the cause and effect flow of conflict should progress along the following lines: a quest, a surprise, a choice, and a climax.

Hitting these points means you’ll create focused, linear conflict in your Scenes. Again, it’s a question of rising tension.

Come in late, get out early

Review the 8-point arc above, however, and you’ll see it doesn’t quite fit snugly into a typical scene. For instance, Scenes begin with a character who’s motivated to achieve their scene goal. The Stasis and Trigger elements of the arc have already happened, perhaps in the previous scene (or Sequel). As noted above, Scenes often end with a turning point or ‘tactical disaster’, meaning the Resolution – the moment where the protagonist’s circumstances are concluded – is likely to be deferred until the end of the story.

Remove these elements and scenes tend to follow this pattern:

• Quest: causing the protagonist to seek something.

• Surprise: but things don’t go as expected.

• Critical Choice: forcing the protagonist to make a difficult decision.

• Climax: which has consequences.

• Reversal: the result of which is a change in status.

Reversals, disasters, and turning points

Here, the ‘Reversal’ refers to the moment John Yorke describes as a turning point – an unexpected reaction that changes things. To Yorke, scenes exist to portray these moments of change. These are the moments that show our character’s progression and tell our stories. Jack Bickham would refer to this as the Scene Disaster, which is a dramatic title – but perhaps that’s the point!

A formula for scene structure

Quest, surprise, critical choice, dramatic climax, reversal… Steer your scenes through each of these points, and you’ll both avoid circular arguments and guide your conflict to a satisfactory climax. Of course, this is a guide – not a hard-and-fast template – but it is well worth considering as you refine and hone your scenes.

And as with any formula, you can confound your reader’s expectations. By altering the flow of conflict you can unsettle your reader and lead them to places they’ve never been before!

Five take home points

• According to Aristotle, events within a story should not be coincidental or irrelevant. Stories should build towards a dramatic and satisfying conclusion.

• To reach a dramatic conclusion you first must pose a dramatic question. Stories are linear, and the journey from question to climax is one of rising tension.

• Rising tension is organised along the lines of beginning, middle, and end. This is not only found across whole stories and acts but within scenes themselves.

• The late Nigel Watts (Teach Yourself: Writing a Novel) steps out what he calls ‘the eight-point arc’, which is another way of organising the flow of your story – and the flow of conflict within your scenes.

• Quest, surprise, critical choice, dramatic climax, and reversal. Steer your scenes through each of these points and you’ll both avoid circular arguments and guide your conflict to a satisfactory climax.

In the next post of this series, we’ll look at Scene Disasters.

Do you have any helpful tips or techniques for writing scenes? If so please share in the comments below. Comments are encouraged!

And if you enjoyed this post, then please share it – you will help get more people writing. I am grateful to you for that!

The post Writing Scenes (Part 4) – Scene Structure appeared first on writezu.com.

August 22, 2016

So You Want To Be A Writer?

Have you ever wanted something but failed to act? Most have had this unpleasant experience. It’s one of frustration, regret, and angst. Sometimes, the untold delay looms at the forefront of your mind. Sometimes it is more unconscious, revealed only be countless dreams of running late, getting nowhere, and arriving unprepared.

Ultimately, life is complicated and many people drift through it. We hope to realise some future ambition but instead live in a state of confusion and denial. So far, so mundane.

A Personal Story

I remember the moment I decided I was going to finally focus on writing fiction. I’d already written plenty of non-fiction, and I wanted to try my hand at a novel (obviously; rather than trying something sensible first – like short stories). Instead, I had a grandiose vision of writing a masterpiece. I’d been carrying around a novel idea, pun absolutely intended, for about ten years.

And, finally, now I was going to write it.

Except, I didn’t. I procrastinated endlessly. I talked about writing, thought about writing, dreamt about writing, but rarely got anything significant on the page. I tried to ‘work out the details’ in my mind. Planning rather than doing. In reality, I just needed to write the bastard thing.

Margaret Atwood

Margaret AtwoodMy frustrations grew each day. I succumbed to all of the distractions. Running errands or playing Football Manager or drinking endless cups of tea or going to the pub with friends or going to work to earn money – such a tawdry business – or sleeping or eating or exercising or watching Game of Thrones.

You get the idea.

Frustration and thinking are a toxic brew

As the frustration grew I found myself angry at all this wasted time. My thoughts became darker, self-critical and more chaotic. I’d go to bed tired, frustrated, and tense. I’d think and think and think, which, given that I’m a professional, experienced, and an excellent therapist – if you don’t mind me saying – came as a shock to me.

But then, anyone can succumb to these human flaws. Something had to change. Both within and without. And then something happened.

The power of pain

One day, seemingly out of nowhere, I found myself in a ditch and nursing a broken heart. Completely bewildered. Completely bereft. It felt like the worst experience of my adult life – and I consider myself to be pretty tough. Still, I’d been a fool and paid the price. All I could feel was pain.

Do not pray for an easy life, pray for the strength to endure a difficult one —BRUCE LEE

Click To Tweet

Character is found in our responses

Life is a series of problems. However, to me, the events that occur in our lives are not so important – it’s our reaction to them. Do we bounce back or do we sink into despondency and dank despair? There is no shame in being knocked into the dust. But, after a period, you have to pick yourself up.

So that’s what I did. At least, after an adequate period of getting drunk and crying into my beer, I picked myself up and took stock. Rebuilt myself. Refocused on the important things: sleep and exercise, hydration and nutrition, going out and having a laugh with friends. Combined, these elements created a platform for well-being. Like medicine.

Writing… lots of writing

Oh, and writing happened. Lots and lots of writing. I stopped the endless cycle of nibbling away at my dreams. Suddenly something seemed very clear: I’m either writing or I am not. Only one course of action will leave me going to bed happy. Clearly, I had to prioritise writing.

I set myself a target: 4000 words per day. High but achievable. I then made sure I wrote before doing anything else, barring exercise. No errands. No emails. No Game of Thrones. I had to overcome the procrastination habit, which – for me – involved meditating away the frustrations and fears. The writing flows when you’re relaxed. Writing is a form of meditation in itself.

So what changed? Well, two things.

On confidence and fear

Firstly, my confidence in my writing was low. This came as a surprise – I’m normally over confident! However, I hadn’t written anything significant for over two years, and I hadn’t attempted fiction since childhood.

The lesson? Don’t expect yourself to be confident before starting out. Allow confidence to build via action, reflection, and experience.

Secondly, I discovered that heartbreak is painful but not fatal. In fact, I found I could deal with it pretty well. Some long-held fears melted away: of failure. Of rejection. Of other people’s opinions. Could they be worse than a broken heart? If I can deal with that I can deal with anything.

Henry Ford

Henry FordBehind most procrastination lies the fear of not being good enough. Well, no more. I intended to do what I’d set out to do. Write. And then write some more. I will write what only I can write, and it’ll either be good enough or not.

Only time will tell.

The importance of taking risks

Success is a matter of risk. You have to look inside and be honest with yourself. Are you doing enough to make things happen? Are you too afraid? Do you have to make more time? Gather the resources you need? Recognise that any great undertaking, whatever it might be, will cost you in time and effort and uncertainty.

Be honest with yourself. Are you going to smash the hell out of it? Or are you going to take little dainty nibbles? The latter isn’t going to work out too well in my opinion.

You can't build a reputation on what you're going to do. —HENRY FORD

Click To Tweet

And it’s about application. You’re either writing or you’re not. Getting on with things or not. Whatever you’re trying to achieve in your life, create a measure of success and failure. A daily or weekly marker that you’re either hitting or not. I don’t always write 4000 words per day, but I aim to. That is good enough.

Whatever you want to achieve in life, my advice to you is this: look within. Appraise what you need. Be confident, and make a start. Your future self will thank you for it.

If you enjoyed this please share – that really helps!

The post So You Want To Be A Writer? appeared first on writezu.com.

June 8, 2016

Apocalyptic Short Story – Do You Remember

Apocalyptic Short Story – Do You Remember?

Apocalyptic Short Story – Do You Remember?RED

It’s always more dangerous at night.

She scrabbles in the blackened earth, working quickly. She doesn’t notice the smell of death anymore; her mind is focused solely on the dangers around her. Every clue is noted. Every sound is registered. There is no room for error. Not here.

A lightning flash catches her eye. She looks up, wary and breathless. What was that? She scans the horizon, squinting for movement in the shadows. But she sees only dead, frozen hills and scorched trees, and she feels alone in the creeping silence. Fine. Her imagination, then. She decides to keep digging.

The soil is gritty beneath her fingernails, and she’s briefly aware of its stench. She uncovers a buried grub and scoops it up. It’s fatty, segmented body spastic in her hands. As a child she wondered whether these grubs knew their fate. Now she just pops them in her mouth. Chews and swallows. She’s numb to the bitter, disgusting taste.

She wants to keep foraging but she’s afraid. Storm clouds, alive with thunder, boil their way across the red-scorched sky. She yearns to get back to her sanctuary. Back to safety. Away from Them.

But she’s also hungry. One grub is not enough and she knows it. She’s been getting weak lately. Slower, both physically and mentally. Hunger and fear compete in her stomach. All it will take is one false move, one mistake, and she’ll fall into their clutches. Miserable suffering. Rape. Violence. Death. Eaten alive by the reviled and unclean.

She scrabbles as she thinks, the flint soil scuffing her fingertips. The scratches. The pain. She watches Them take her parents. First her Mother. A blow to the head. Killed outright. Consumed in a mist of blood and guts and sinew. Father and I watching from the shadows. Cast-iron statues stood in silent horror.

And then Father. Her beloved father. Her protector. Her teacher. Her love. She remembers, and a solitary tear falls from her gray-blue eyes. The Earth swallows it with contempt, but she fails to notice.

Her digging reveals a shiny black beetle. She snatches at it, breaking two of its legs, and pops it into her mouth. Crunches. Crunches. Its liquid insides spew warmth and sourness into her mouth. She swallows without ceremony and winces as Father’s face swims through her mind. She imagines them raping him and eating him. She imagines him crying out in pain.

Another solitary teardrop. Perhaps she should just let Them take her too. Have it over and done with.

Never.

It’s ice cold beneath this cavernous, shit-streaked sky, and her breath is a mist of condensation. She should be shivering but she’s numb. She always is when she thinks about Father.

And then a sudden flash! She struggles blindly into the gloom, her night-vision wrecked. Some kind of meteor? Her vision returns and she traces its passage across the darkening sky. Its tail is tangerine and smoke, stretching for perhaps half a mile. The meteor head, which seems a living, pulsating thing, expands and contracts as it combusts across the sky. At one point she wonders if it might explode. Instead, it describes an elegant arc towards the horizon.

Shit. Shit! I’ve got to get moving.

She leaps up and is away. Agile footsteps carrying her home. Zigzagging from shadow to shadow; taking care on the uneven scrub. She pauses for a moment behind a wrecked concrete wall, listening for danger in the darkness, but all she can hear is the pounding of her own heart.

Her sanctuary is perhaps five minutes away. She moves quickly, but she’s never complacent. This land is treacherous and it would love to betray her. It’s caught her out several times in the past.

She arrives at the entrance to her home. It looks like an unremarkable clearing, cut into a forest of broken, dead trees. You could walk past it a million times unaware, because this entrance isn’t just a physical place. It’s more of a portal. To enter, you have to close your eyes, relax your mind, and step beyond your cascading experience of reality.

She’s sensed many such doorways, but this is the only one she’s ever dared try. She relaxes her thoughts and leaps into the infinite void.

SILVER

It’s like being in a cave that is illuminated by moonlight. She feels safe here.

In that other world, of fire streaked skies, of dead trees and grubs, she is now a mere suggestion. A blade of grass moving in the breeze. A hint of shadow in the gloam. But here, this place of moonlight and safe passage, she is real. At least, her soul makes it seem real. Her experiences seem real. And her safety is real. Were it not for the need to eat, she would never leave her sanctuary. She depends on it.

But then she realises. Something is wrong. Very wrong! She stops dead, frozen and terrified. Even her heart feels reluctant to beat. Somebody is here. Somebody is in her shelter. But how? And why? She feels violated. Excited. Dismayed. Intrigued. This is change. And change is rarely good.

At her feet stand twelve stone steps, leading down. No matter where she stands in her sanctuary, these steps are there if she so chooses. An image then flashes across her mind. The face of a man. Not Father, dear beloved Father, but somebody else. Somebody younger. Somebody new. Anxiety bites at her stomach and she wants to run away.

Be brave! This is your home. She wants to hesitate, but instead she starts down the stairs. Silent, barely capable of breathing, almost like she’s floating, or sinking, drifting deeper and deeper into her sanctuary with each step. Be brave, she reminds herself. Besides, where else could be safer? There can be no raping or killing here. No eating of flesh. Everything here is just a projection. Just energy and nothing more.

She arrives at the bottom of the stairs and stands by the door to her private room. She can sense his presence inside. She pushes the door open and peers into the cave-like room beyond. An expression of his body lies on the floor. Naked. Bruised. Bloodied and twisted. He’s calling for help, his voice barely audible. She pads towards him, across the cold, stone-hewed floor, like a cat inspecting a dead bird.

Except he is not dead. He groans and whispers for water. In this place, a place made entirely of thought, there is no water. But she sits beside him and imagines offering him water to sip. She imagines mopping his brow. She imagines cooling the heat of his broken body; easing the pain as he dances between life and death.

She lies on the floor beside him. Tentative. Cautious. She’s afraid to trust him, but in her heart she knows he is good. She watches him rest until, eventually, he opens his eyes. They’re deep green, like pools of water in the desert, alive with energy and movement and change. She feels herself flowing into him. A river running into the sea.

BLUE

She wakes on a beach, momentarily confused. The sand is cool and wet beneath her, and she hears the ocean washing against the shore; a rolling, pink noise that soothes and relaxes. She stretches and gazes towards the sky, transfixed by its cobalts and azures; its admirals and ceruleans. Where on Earth is this place?

And then there is the sun’s warmth against her skin. How is that even possible? She contrasts it against the cool sand beneath her, as if to test whether such warmth could be real. It makes her want to stretch and laze around. She imagines falling into the sky, through white, wispy cloud, and into whatever depths lie beyond.

Sudden alarm pricks at her. She’s not alone! She jumps up, spins around, and sees him. She’s relieved – for a moment she thought she was in danger. He’s gathering driftwood; it clatters as he piles it into a bonfire. He looks at her, smiles, and she realises they are both naked.

Still, she feels calm and relaxed. She sits near his unlit fire and inspects her sand-covered feet, amused by the shape of her toes. She finds herself laughing like the girl she used to be. Here, in this bright and sunny place she feels even more safe than in her sanctuary. Never had she imagined that possible. It’s like a dream from a long time ago.

He’s still busy with the fire and she steals glances at his body when he’s not looking. He’s dark and handsome, glistening with sweat, and deliberate in his movement. He smiles at her with his eyes and her insides melt. She feels content to rest and be still.

He wanders to a scrubby verge at the end of the beach and returns with clumps of dry grass. She watches, fascinated, as he strikes two flints together, repeatedly, methodically, until he eventually creates a spark. The dry grass becomes at first a smoking ball, and then a true-lit flame. He breathes life into the fire – while shielding it from the breeze – and encourages it along the bone dry driftwood.

They sit together in the falling dusk. The cobalt sky darkening towards navy; the roaring apricot flames dancing upward. It’s cooler now and she draws her body closer to him, enjoying the feel of his naked skin. She looks into his eyes, running her fingers across his chest, and then they kiss. Slowly at first, and then passionate and urgent and lustful.

He gently, firmly, pushes her onto her back, and she wraps her arms around him. Their kiss continues, tongues meeting in her mouth, and she forgets about the sand and the sky. Only the fire remains; its crackling heat a warming comfort. He lies on top of her. His hand stroking her body for the first time. His kisses move to her neck and earlobe, and she arches her back with pleasure.

He’s hard now. And she is wet. Yearning. But also anxious and afraid. All she knows of this is violence; of the death of her mother and her father. She wants to stop, but also to continue. To open her legs and let him touch her. For him to push himself inside of her. Gently at first, and then more forceful with each stroke. She kisses him deeply, her arms still wrapped around his neck, and she opens herself up to him.

He slides himself into her. Their bodies entwined, rhythmically pressing together. She drinks up the sensations; getting hotter and wetter. He becomes harder and more forceful. Their kisses more urgent and their rhythm quickening. She gasps at the white hot energy gathering between her legs. Volatile. Pulsing with each stroke. She wonders if she is about to explode and forgets to breathe.

He pushes himself deep into her. Powerful, last moments and then he tenses up. Convulsing. Burying his head into her shoulder. She feels this and explodes with her own energy. Hot, wet, fizzing and intoxicating, deep into her core. It’s a moment she wants to last forever.

*

She wakes, disoriented and upset, and untangles herself from his arms. This wasn’t supposed to happen.

Who is he? How did he find her? Why has he brought her to this place? Why give her something else to lose? Hasn’t she known enough pain already? She feels suddenly angry. Hateful even. Far better to pick through the shit-smelling landscape for grubs; at least you know what’s in store. Eat insects. Live as long as you can. And then join Mother and Father in the next world.

A solitary tear lets loose from her eye. It runs down her cheek, falls from her face, and splashes onto the cool sand below. She hadn’t asked for any of this. She screws her eyes tight and wishes it would just vanish.

*

DARKNESS

The door stood ajar so she peered into the gloomy room beyond. A little girl sat sobbing on the stone floor. Her cries felt like a stiletto blade to her heart, and tears ran from both their faces. She pushed the door open, and entered.

She asked the little girl what was wrong. The girl looked up and replied that her name was Maya. Her eyes glittered with a thousand lives and her voice seemed impossibly old.

Maya beckoned for her to sit down. She did so, despite feeling afraid, and asked the girl why she was crying.

When you look inside, said Maya, into the depth of your heart, you might see me. Sometimes I am happy and playful. Sometimes I am sad. Today I am alone.

She felt angry towards the little girl. But what do you want me to do? I cannot bear the pain of loss even one more time. They remembered Mother and Father, and sat in silence for a while.

Yes, but if you are afraid to take risks, replied Maya, fear will become your whole world. Dark thoughts will become prison walls, and freedom will become a mere dream.

She looked at Maya from the side of her eye. Curious little girl, she replied. How can you know of such matters?

Maya smiled with sparkling eyes. I only tell what you already know. What would you prefer? To live in the sunshine or exist in the shadows?

She knew the little girl was right. It was a question of courage, which she had. And a question of remembering what was important, which she now understood.

*

SUNSHINE

She snapped out of her daydream and looked around. Here, beneath this cavernous, shit-streaked sky. Her breath a mist of condensation. She should be shivering, but instead she feels numb. Disorientated. Like she’s forgotten something.

And then a sudden flash! She struggles blindly into the gloom, her night-vision wrecked. Some kind of meteor? Her vision returns and she traces its passage across the darkening sky. Its tail, tangerine and smoke, arcing towards the distant horizon.

Shit. Shit! I’ve got to get out of here.

But she freezes. There’s an itch in her mind. A nagging doubt that just won’t leave. What have I forgotten? She imagines golden sand beside the ocean. She feels… the sun? Ridiculous, but she remembers the sun warming her skin. And a roaring fire, stark against the navy sky. And then she sees him. His face, his green eyes. Their union. In that moment she remembers everything.

She watches the meteor plummet to the distant horizon, and knows precisely what she needs to do. She no longer feels afraid. She just hopes to reach him before They do.

The night sky is miserable with mahogany and blood, and she knows she must take care. Twice she stops and lurks in the shadows, hiding from groups of Them. Their grunting and snuffling disgusts her. Their dull red eyes, like embers of hatred. And their clawing, raping hands. Perversions of all that is good. She will not allow them to win.

She makes her way up a steep, rocky outcrop, near to where the meteor fell. She crawls on her belly and peeks over a stony ridge. In the distance, she sees his body lying in a shallow, smoking crater. He’s naked. Bruised. Bloodied and twisted. She knows, somehow, that he is alive. And she knows they will be drawn to his suffering.

And then her heart sinks. They’re already here. She sees six of Them. Seven. Eight. Lolloping their way towards him. She can make out their thick black hides, wrinkled and bristling with boils, open sores, and wiry hair. Their heavy slack jaws with protruding needle teeth, curved and razor sharp. She remembers how they fed on Mother’s remains. The foam spray of blood and their triumphant desire. Gleeful to destroy something beautiful.

And they’re moving in for the kill. She screws her eyes tight and starts to cry. Unable to watch. Maya’s voice appears in her mind. The little girl says: You can defeat them. You have the power to do so. Suddenly, she understands. She has more control than she thinks.

She takes a deep breath, slows down her thoughts, and becomes calm, relaxed and at peace. She watches the colour drain from the landscape around her, and feels the endless, intricate beat of reality slow down, as if to a mere single pulse. Time stops dead, or near enough, and They grind to a halt like hideous and misshapen statues in the dark. She seizes her moment and descends from the rocky outcrop, picking her way past their stench of shit and death. Their fractal-red eyes, dull with pain and violation. She hurries herself along to the smoking crater. They might appear as statues for now, but that won’t last forever.

She tries to lift his prone body, but he’s too heavy. She feels a rising panic. Relax, you can do this. She composes herself and focuses her determination. She takes him by the armpits and pulls at his dead weight. His legs drag uselessly and she wishes he’d wake up so they could run.

If I can just get him to the top of the outcrop… She’d sensed an entrance there, a portal to her sanctuary. It’s a risk; she’s only ever tried her own entrance before. What if this one works differently? She puts that thought out of her mind. Either way, it ends here tonight. She’d rather die than leave him to this fate.

She doubles her efforts, struggling backwards, dragging his unconscious body up the outcrop. But it’s heavy going, her arms are growing tired, and she stumbles with exhaustion. The land here is unyielding; it desires only blood and slaughter. And she’s aware that time is speeding back up, and that they are waking from their trance. They’ve started to follow her. Lolling up the outcrop. Gaining distance all the time. She smells their hatred and cruel hunger.

The closest of Them surges forward. It’s almost upon them. Hungry. Determined. Violent. She struggles on through tears of frustration. If only she could make it to the portal, at least they’d have a chance. But she has nothing left to give. She simply cannot drag him an inch further. She falls to the ground, defeated. There’s no question of leaving him. They’ll die here together. Side by side.

It won’t take long. The foul creature bares its teeth, a snarl of grey-yellow needles and black saliva. The stink of rotting flesh. Its eyes red with malice and its hide as black as tar. She’s been afraid of Them all her life. But now, at the last, her fear is no more. She closes her eyes and waits.

No! You do not have to accept this. To have found him, only to lose to this horror. You must not accept this face. There is another way…

She remembers their coming together, on that beach under the midnight sky. She remembers the energy she felt, and her true nature becomes clear in her mind. She is a child of God. Nothing less than the entirety of the Universe, and far more powerful than this dank place. Than these dank beings. Her mind feels alive with the heat of a billion suns. She is all things. Everything and nothing.

She opens her eyes and channels this truth into the creature’s hateful, lustful mind. Its red eyes suddenly glowing bright with alarm. You are nothing but hatred and filth. Begone! There is a moment of pure stillness, and then the outcrop is lost to a pure, blinding light. A thunderous crack! A sense of discontinuity. Time stands meaningless, and, when reality returns, all that remains of ‘It’ is a haze of vaporised carbon.

The others stop in their shuffling tracks. They stare amongst themselves, awash with terror.

She looks to the blood-streaked sky and screams. She remembers her beloved Mother and Father. Foraging for grubs and beetles. The endless running and hiding. She screams an endless cry that would shatter walls. They turn, scattering, shuffling, running away as quickly as they can. She is the Universe itself, and they are nothing but shadows.

Cowardly too, she observes. She blinks, just once, and each one vanishes from existence. They leave no trace in their wake.

All is silent, at least until her heaving sigh. She checks to make sure, but she already knows he didn’t make it. His chest is still. His face a peaceful, lifeless pallor. She kisses him, gently, just once, and yearns for it to revive him. But deep down she knows the truth. He is dead. They have won after all.

How could it all be in vain? How can she be expected to bear more loss? A solitary tear drops from her blue-gray eye and lands on his forehead. And, after a single, silent moment, he gasps his way back into this life. He sits up boltright, coughing and choking. Convulsions fit enough to expel death itself. And then, eventually, he rubs his face, regains his composure, and smiles at her.

Hello, he says.

Hello, she replies.

Still coughing, he staggers to his feet. She takes his hand and they make their unsteady way up the outcrop. They both sense the sanctuary portal, and they know what to do. They close their eyes, relax their minds, and leap into the infinite void.

BLISS

She hears the ocean washing against the shore; a rolling, pink noise that soothes and relaxes. She gazes at the sky, transfixed by its cobalts and azures; its admirals and ceruleans. And then there’s the sun’s warmth against her skin. It makes her want to stretch and laze around. She looks up and sees him gathering firewood.

He notices she’s awake and smiles. Her insides melt, and she knows she’s found an endless love. She stretches in the sunshine, and laughs.

The post Apocalyptic Short Story – Do You Remember appeared first on writezu.com.

March 9, 2016

Writing Scenes (Part 3) – Conflict in Writing

This series of posts will teach you all you need to know about writing scenes. We’ll consider topics such as Scene and Sequel*, cause and effect, scene goals, and the like. The aim is to build a comprehensive starting point for any new author. In this post we’ll focus on: conflict in writing.

* We’re using Scene and Sequel (capitalised, italics) when referring to these specific terms and ‘scene’ (no capitals or italics) to refer to scenes in general.

A recap…

We previously defined the term ‘scene’ by quoting author Jordan Rosenfeld: ‘Scenes are capsules in which compelling characters undertake significant actions in a vivid and memorable way that allows the events to feel as though they are happening in real time.’

This definition reminds us to slow things down, zoom in on the action, and savour the drama presented on the page. Scenes are your story’s highlights, and you should maximise their impact.

However, what do we mean by drama?

Scenes tell of thwarted desire

Scenes tell the story of your protagonist’s attempt to reach their goals. They are unlikely to prevail without a fight. They will be confronted by antagonistic forces that either want the same thing or, at least, to stop your protagonist from progressing. Either way, conflict will ensue.

To defend what you’ve written is a sign that you are alive. —WILLIAM ZINSSER

Click To Tweet

Scenes have a structure

Scenes are often described as mini-stories in themselves: they have start, a middle, and and end. Conflict in writing represents the middle, and this is where we risk getting bogged down. We need to be clear on what conflict is. So, let’s start with the obvious question:

What is conflict in writing?

According to dictionary.com, the noun conflict can mean:

1. A fight, battle, or struggle, especially a prolonged struggle; strife.

2. Controversy; quarrel: conflicts between parties.

3. Discord of action, feeling, or effect; antagonism or opposition, as of interests or principles: a conflict of ideas.

4. A striking together; collision.

5. Incompatibility or interference, as of one idea, desire, event, or activity with another: a conflict in the schedule.

6. Psychiatry. a mental struggle arising from opposing demands or impulses.

These definitions tell us plenty. Conflict describes disagreement and contradiction; it describes incompatibility; and it describes battle. Conflict is movement and struggle. It is a process that flows over time.

The blowing of the wind is action, even if it is only a breeze. And rain is action, even to its name. The verb and the noun are one. — Lajos Egri

In his seminal book, The Art of Dramatic Writing (1942), Lajos Egri notes that action cannot come of itself. He gives the example of the caveman who kills for food, self-defense, or glory. Killing, although action, is ‘the result of important factors.’ This is cause and effect once more. To Egri, everything is the result of something else, and results in something else.

Let’s put this under the microscope; the results should be revealing.

The flow of conflict

Characters, like people, don’t live in a vacuum. Nor are they static beings. Characters respond to everything within their environment according to circumstance.

To understand this fully, we can look at the following model from Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. (CBT is a type of psychotherapy that focuses on our thoughts, emotions, and actions):

Feelings, thoughts and behaviours.

Feelings, thoughts and behaviours.This diagram describes the relationship between our circumstances and our inner experience:

• Situation: our environment – the terrain, people, activity, and dynamic we find ourselves surrounded by.

• Thoughts: our cognitive experience – inner dialogue, mental imagery, memories and predictions.

• Feelings: our emotions – the experience of sadness, anger, hope, despair, etc.

• Physiology: bodily sensations and reactions – our heart rate, sweat response, involuntary jerks or spasms, blushing response, body temperature, etc.

• Behaviours: the things we say and the actions we take, including the involuntary (flinching, etc.) and habitual (e.g. mindlessly* opening Facebook when sitting at your computer).

* is there any other way to open Facebook?

This model is interesting because it describes how one thing influences another. If you’re angry then your thoughts and physiology will reflect that. You could then suppress that anger, or express it into your situation – either of which is a behaviour.

Fiction is the truth inside the lie. —STEPHEN KING

Click To Tweet

The opposite is also true. If you’re in a happy and relaxed situation, your thoughts, emotions, physiology and behaviour will reflect that. This exchange between environmental factors, inner experience, and action is another instance of cause and effect. It represents the heart of drama.

Stimulus, internalisation, and response

Jack Bickham, in his 1993 book (in his book Scene and Structure), introduces the concept of ‘stimulus’ and ‘response’:

Stimulus and response is cause and effect made specific and immediate. They function right in the story ‘now’ – this punch making the other man duck…or this question making the other person reply at once. —Jack Bickham

This is particularly helpful. It shows how a stimulus provokes changes to a character’s thoughts, feelings, physiology, and behaviour – just as the CBT model predicts.

Of course, compelling drama doesn’t stop there. The resulting dialogue or action will then influence the ‘situation’, in turn provoking more responses. It’s a chain of cause and effect.

To Bickham, conflict begins with an external stimulus – something that ‘could be witnessed if the transaction were on a stage.’ He argues that the response must also be external, and that it usually follows immediately after the stimulus. Let’s play around with this, and see how it looks.

Examples of stimulus and response in action:

1. The following example is flawed, because there’s no external stimulus to trigger Mike’s action:

Mike entered. He hit John.

(response) John said, ‘what the hell?’

2. Here, neither stimulus or response matches up (although the exchange does at least begin with an external stimulus):

Mike entered.

(stimulus) John said, ‘hey, what’s up?’

(response / stimulus) Mike hit John.

(response) John said, ‘fancy a beer later?’

3. Here, the response doesn’t immediately follow stimulus:

Mike entered, looking furious. (The ‘furiousness’ gives context for Mike’s subsequent response.)

(stimulus) John said, ‘hey, what’s up?’

(response / stimulus) Mike hit John.

(response) Six hours later, John shouted, ‘what the hell is wrong with you?’

4. Here, word order destroys the logical flow of things:

Mike entered, looking furious.

(stimulus) John said, ‘hey, what’s up?’

(response / stimulus) Mike hit John.

(response) John shouted, ‘what the hell is wrong with you?’ Pain stabbed at his bloodied nose.

That last line would make much more sense if it read: Pain stabbed at John’s bloodied nose. ‘What the hell is wrong with you?’ he shouted.

Ultimately, ‘stimulus’ and ‘response’ are just labels – a response can also be a stimulus. Similarly, you can describe bursts of stimuli before you get a response, or a chain of responses to a single stimulus… The labels aren’t so important, as long as the exchange of energy starts and ends with something external, and follows a logical progression in between.

Internalisation

Novels hold a significant advantage over other storytelling forms: they describe what a character is thinking and feeling.

Characters are not robots (unless you’re writing about robots, but let’s save that paradox for another time!)

Your characters have an inner world – their thoughts, feelings, impulses and involuntary responses. In fact, this inner landscape is often the most interesting aspect of a novel. It makes sense to describe it, especially in those moments where you might need to clarify or give context.

Here’s a speculative observation: some books spend less time describing internalisation. They tend to be plot driven and move along at a rate of knots. Other books seem to describe internalisation in much more detail, and tend to be slower ‘paced’.

Example of stimulus, internationalisation, and response:

Mike entered, looking furious.

(stimulus) John said, ‘hey, what’s up?’

(internalisation) Mike couldn’t believe what he was hearing. What’s up? I’ll show you what’s up! (response / stimulus) He hit John, square on the nose.

(response) John fell backwards. ‘What the hell’s wrong with you?’ he shouted.

Okay, I’m not expecting a call from my agent at any time soon – but you get the idea. To Bickham, the flow of stimulus, internalisation, and response is the fabric from which stories are woven. Orchestrate this incorrectly and confusion will reign.

In fact, Bickham advises playing with the order of these elements to create deliberate confusion should your scene call for it. It’s a question of what you’re trying to achieve.

Motivation reaction units

There is another way of organising the flow of conflict through your scenes. In her excellent 2013 book, Structuring Your Novel, author K.M. Weiland presents a clear and concise overview of Dwight Swain’s ‘Motivation-Reaction Units’.

In this approach, the cause and effect of drama flows precisely as described – via motivations and reactions.

Motivation

Motivating factors are found in the narrator’s description of events and surroundings, in the action and dialogue of non-POV characters, and in the narrator’s internal dialogue (this differs from Bickham’s ideas, where motivators are only found externally).

Reaction

In response to these motivators, your POV character will offer some kind of reaction. This could include thoughts, emotions, actions, or dialogue. Weiland notes that reactions tend to follow this order:

Feelings and/or thoughts.

Action (includes involuntary physical responses such as sweating or breathing hard).

Speech.

Having worked with the CBT model for many years, I’d say that was about right. Weiland points out that you don’t always need to describe the three layers of the reaction; sometimes just dialogue will do. She also notes, like Bickham, that you can play with the order of Motivation-Reaction to suit your needs.

We’re not creating machine-precision prose; we’re weaving tapestry. And it’s the flaws that make Persian rugs interesting.

And the difference between the two?

Very little – it’s all just cause and effect, and the labels are just labels.Use whichever approach feels intuitive to you.

Types of conflict

The scope for conflict in writing is as broad as the scope for conflict in life. As a general rule, conflict just means your protagonist is struggling to achieve their goal:

• Perhaps somebody stands in opposition to them. An antagonistic force either wants to stop your protagonist, or they want the same thing. This could be the case from the outset, or it might develop over the course of the scene. It could be direct and confrontational, or it might be subtle, e.g. being ignored, ridiculed, or via passive-aggressive behaviour.

• Perhaps something stands in their way. This could mean an environmental obstacle, a lack or abundance of something, or a clash: of views, of schedules, of interests, etc.

• Perhaps your protagonist is standing in their own way. Through our own weakness, fear, indecision, and hubris, we often defeat ourselves. This can be the most interesting conflict to read about.

For a full discussion of your options for conflict, take a look at this post on K.M. Weiland’s blog. Remember, whatever opposition you set up between your protagonist and the antagonistic forces they face, only one can win.

Keeping it real…

The scope for conflict in writing is pretty much infinite. However, it’s important to make it a) relevant, b) interesting, and c) proportionate. You want your conflict to move your story forward and in the right direction:

• Relevant: conflict should arise organically from your protagonist’s pursuit of their goal – and the the opposition that stands in their way. Your reader will easily see through contrived conflict, and it will cost you their trust.

• Interesting: some writers worry about inflicting pain and misery on their characters. Interesting fiction cannot be painless; even the blandest fantasy fulfilment must contain friction, pain, and upset. Don’t give your characters – or your readers – an easy ride.

• Proportionate: ramp up your conflict too dramatically, and you might spin things off in an unintentional direction. If your light-hearted heroine is struggling to beat her rival, do try to keep her away from the shuriken!

Raising the stakes

To stop conflict from feeling repetitive or dull, our task as writers is to find interesting ways of raising the stakes. If you find your conflict is flagging, this is the first point of call – but remember not to go straight to DEFCON 1, as that could have unintended consequences later in your story.

Five take home points

• Scenes are mini-stories in themselves, with a start, a middle, and an end. Conflict represents the middle, and this is where – as with all stories – we risk getting bogged down.

• Conflict is disagreement and contradiction; it is incompatibility; and it describes battle. Conflict can exist between various parties, ideas, principles, or interests and it can be found within.

• Characters are not static beings in a vacuum. They respond to their environment according to circumstance. Look into the Cognitive Behavioural Therapy model of psychotherapy for ideas on this.

• Use Jack Bickham’s stimulus, internalisation, response pattern, or Swain’s Motivation-Reaction units, to organise conflict into a logical flow. This will help move your story forward.

• The scope for conflict is pretty much infinite, but it’s important to keep conflict relevant, interesting, and proportionate.

In the next post of this series, we’ll look at the structure of scenes.

Do you have any helpful tips or techniques for writing scenes? If so please share in the comments below. Comments are encouraged!

And if you enjoyed this post, then please share it – you will help get more people writing. I am grateful to you for that!

The post Writing Scenes (Part 3) – Conflict in Writing appeared first on writezu.com.

March 2, 2016

Writing Scenes (Part 2) – All About Goals

This series of posts will teach you all you need to know about writing scenes. We’ll look at matters such as Scene and Sequel, scene structure, scene goals, and the like. The aim is to build a comprehensive starting point for any new author. In this post: scene goals.

A recap…

Previously, we defined the term ‘scene’ by quoting author Jordan Rosenfeld: ‘Scenes are capsules in which compelling characters undertake significant actions in a vivid and memorable way that allows the events to feel as though they are happening in real time.’

This definition is helpful: it reminds us to slow things down, zoom in on the action, and savour the significant drama presented on the page. Scenes are your story’s highlights.

We then went on to note the difference between the dramatic Scene*, which focuses on conflict, and the reactive Sequel*, which describe your character’s resulting dilemma. This is cause and effect in action – one thing leading to another.

* We’re using Scene and Sequel (capitalised, italics) to refer to these specific terms, and ‘scene’ (no capitals or italics) to refer to scenes in general.

The anatomy of a Scene

The dramatic Scene unfolds along the following lines:

A goal

Author Jack Bickham (in his book Scene and Structure) claims that Scenes should begin with your protagonist stating their intention. He refers to this as your protagonist’s ‘scene goal’. This prompts the question: will the protagonist achieve their goal? Posing this question creates suspense in your reader; they read on to find the answer.

Conflict

For the scene to be interesting, your protagonist can’t just achieve their goal straight away; someone – or something – must block their path. Generally, this means the protagonist is confronted with an equal and incompatible desire – an antagonistic force who wants the same thing or, at least, to stop your protagonist from progressing.

Your protagonist and antagonist each have their objectives, and only one can win. Matters unfold along the lines of action and counteraction, feint and counter-feint, until, your protagonist’s actions provoke an unexpected turn of events. In other words: a tactical disaster.

A tactical disaster

This is the moment where the ‘scene question’ is answered. Most likely, your protagonist will not achieve their goal. Or, if they do, it will lead only to further complications. The disaster you visit on your characters should hit hard, moving the story forward while setting the protagonist back.

These disasters are moments of change. John Yorke (In his excellent book Into The Woods: How Stories Work and Why We Tell Them) claims this is the real reason that scenes are chosen by the writer.

Mike Nichols

Mike NicholsSo, to deconstruct the dramatic Scene, we must first look at the issue of goals. Because, without goals, there simply cannot be a scene – or a story.

Let’s begin with:

What are scene goals?

Put simply, a goal is an outcome you’re going achieve with your action(s):

• I am going to lose weight.

• I am going to rob a bank.

• I am going to woo the girl next door.

• I am going to write an article on goals.

Note the commitment to action in these statements. Goals aren’t dreams (I’d like to lose weight) or pessimistic declarations (I wish I could lose weight); they’re specific statements of intent – aims that you intend to realise.

Why are goals important?

We previously noted Jack Bickham’s advice: make your protagonist’s goal evident from the outset. Otherwise, we’ll have no notion a) of what the protagonist is trying to achieve, and b) that we should be concerned with the outcome.

There are only three kinds of scenes: negotiations, seductions, and fights. —MIKE NICHOLS

Click To Tweet

Not only should the protagonist’s goal be clear, but it must relate to the plot. If you story is a hard-boiled thriller about corruption, it makes little sense to focus on your protagonist’s goal of stopping next door’s dog from chewing up his pogonias (unless this is a subplot, and the dog’s owner will prove relevant later on – but let’s save subplots for another day!)

Your protagonist may anticipate a hard time acquiring their goal, or they might be surprised to be blocked by antagonistic forces. In either case, achieving their goal cannot be a breeze – who’d want to read about that?

And this difficulty is your source of conflict. One character’s committed intention meeting an incompatible force. It is a game of high stakes. What happens if he fails? If he succeeds? His goal has to mean something. Otherwise, there is little chance of tension.

Generally speaking, your character’s goal will involve the acquisition of or an escape from something physical, emotional, or mental. This could require any action conceivable: finding, hiding, communicating, repairing, destroying, etc. For example:

• Physical goals: searching for a smoking gun; escaping from an enemy; destroying or repairing an object.

• Emotional goals: trying to win over a character’s affections; escaping from his father’s scorn.

• Mental goals: learning how to disarm an alarm; confronting a person about their behaviour.

Our goals are not random, and neither are your character’s. And this brings us to an obvious question: where do scene goals come from? To answer this, we need to zoom out and look at the big picture.

How do stories start?

Let’s recap on the basics. Stories introduce us to a protagonist. We’ll experience the story through their senses, their emotions, their thoughts and actions. They may be likeable – or not – but we’ll be invited to empathise with them. They are our gateway into another world.

Early in our story, something is likely to happen that throws the protagonist’s world out of balance; something which forces them to make a choice. It could be a mission, an opportunity, or a problem to solve. Whatever the circumstances, your protagonist will be given a goal to pursue – whether they like it or not.

This goal might remain consistent throughout the rest of the story, or it might evolve as things progress. Either way, if your protagonist is going to achieve this goal, they’re going to need a plan.

To understand this more thoroughly, let’s look at goal-setting in general.

How to set goals

You may have heard of SMART goals. It’s a system for making well-formed objectives, the aim being to foster focus, motivation and progress. There are different versions, but here’s my preferred take:

• Specific: the when, where, what, and why of the goal.

• Measurable: so you’ll know whether you are achieving your goal – or not.

• Achievable: the goal is not impossible our outlandish.

• Relevant: the goal is consistent with your needs, values, or circumstances.

• Time-based: there is a time-limit on your goal; it’s not just an open-ended dream with no urgency.

Some people think like this naturally; others think like this only in specific circumstances. Many of us rarely think like this at all. The SMART goal system helps those who lack motivation to think in goal-orientated terms.

How this helps your protagonist

As writers of fiction, we are advised: don’t write about wimps. Our stories can be about extraordinary people, or ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. These are people who are motivated – for whatever reason – and who feel ready to take action, even if reluctantly.

Of course, I’m not suggesting that your protagonist needs to sit down, at the start of their story, and hire a life coach! Rather, your story’s evolving circumstances will force your protagonist to start thinking in a goal orientated way. They need clarity – their goals can’t be fuzzy or nondescript.

A plan of action

Clear goals are all well and good, but to get anywhere you need some sense of the required steps. Otherwise, how will you know where to start?

In fiction, as in life, it’s not unusual for the protagonist to encounter a mentor figure – somebody to show them the way. Or perhaps your protagonist will set out to achieve their goal by themselves. In either case, they will have to break down their goal into a series of steps.

And these steps are the basis for our ‘scene goals’.

Example – Cool Runnings

Released in 1993, Cool Runnings is a feelgood Disney film based very loosely on a true story. It tells the story of Derice, who holds an ambition of being an Olympic champion – just like his father.

Things don’t pan out (they never do!) and he misses his chance at qualification. He begs for a chance to run again, which is turned down. Instead, he spies an opportunity to compete at the Winter Olympics in the bobsled competition. Unlikely as this goal is, his mind is set. He now has a series of tasks he must undertake.

Find the coach, Irv, and convince him to come out of retirement.

Recruit other members for the bobsled team and divide their responsibilities.

Learn how to drive a bobsled.

Raise the funds required to travel to Calgary for the Olympics.

Adapt to the cold and learn how to walk on the ice.

Qualify for main competition.

And so on… Derice’s main goal (compete at the Olympics) requires him to navigate a series of smaller goals (find and convince the coach, raise the funds, etc.) Some of these smaller goals can be achieved in one scene, whereas others take a few scenes to accomplish.

This is cause and effect in action once more: I want this, so I have to do that (and that, and that, and that). There might be wrong turns, false starts, defeats and reversals; but each step should contribute to the protagonist’s main aim in the story. It’s robots solving mazes.

Your protagonist’s goal could be anything – woo the girl, find the MacGuffin, become king of the world – just so long as it’s concrete. However, this gives rise to another question…

Why do heroes bother…

Why bother going to all this trouble? Why not just have a cup of tea and let somebody else get on with it?

Ultimately, the protagonist must feel they don’t have a choice. They may even try to refuse the call, but something will compel them to take action. Let’s look at the various influences on your character’s goals.

Self-concept

According to Jack Bickham, stories truly start when a significant change threatens the protagonist’s ‘self-concept’, which is our mental image of who we think we are. Bickham gives the example of ‘an efficient secretary’ (her self-concept) who’s feeling threatened by ‘new and confusing computer equipment’.

In this story, our secretary will try all kinds of tactics to regain her self-concept: learn the new systems, confront her boss, even quit her job. She will not, however, revise her self-concept to accommodate her new circumstances. Bickham writes: ‘self-concept is so deeply ingrained, and so devoutly protected, that most people will go to almost any lengths to protect it as it stands today.’

Somebody's got to want something, something's got to be standing in their way of getting it. —Aaron Sorkin

Click To Tweet

In this model, your protagonist’s goal is to ‘fix things’. This raises the ‘story question’: will your hero put things right? To Bickham, this is another source of tension. It is a question you answer only at the end of your story.

This idea of ‘fixing things’ is echoed by John Yorke. He writes, ‘when something happens to a hero at the beginning of a drama, [it] is a disruption to their perceived security. Duly alarmed, they seek to rectify their situation; their ‘want’ is to find that security once again.’

Perspectives on self-concept

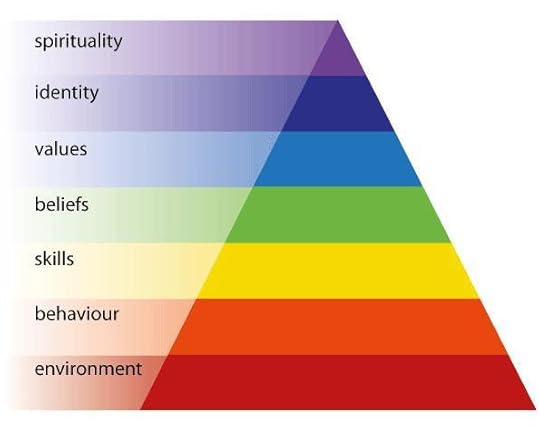

It’s interesting to look more deeply at the idea of a self-concept. One model from Neuro-linguistic Programming, the Neurological Levels model, describes it as having various levels:

Neurological Levels Model

Neurological Levels ModelBoth NLP and this model have their critics, but it’s useful from a story point of view. The basic premise is that each level is ‘organised’ by the level above it. So, our beliefs affect our skill, which affects our behaviour, which affects our environment, and so on…

Our self-concept can be threatened on various levels. Our environment could be changed, or our behaviour inhibited or controlled; our skills could be outlawed, or our beliefs and values challenged. Even our sense of identity could be under threat, as with Bickham’s efficient secretary. This model allows us to see the various perspectives involved.

Life Goals

KM Weiland notes that characters might possess life goals that are entirely separate from the immediate plot of the story. She writes: ‘Sometimes life goals don’t affect the plot at all. Other times, life goals can only be enabled if the plot goal is met. And, other times, life goals will stand in the way of the plot goal.’

An excellent example for the latter might be George Bailey in the 1946 film ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’. His life goal is to get out of Bedford Falls, because he holds an ambition: to do big things. (And of course, this ambition is realised later in the story, albeit in a different way.)

Wants versus needs

So, story is about a character’s pursuit of their goal? Not exactly (if anything, that seems to be a definition of ‘plot’). Yorke notes that ‘what a character thinks is good for them is often at odds with what actually is.’ This conflict gives rise to a battle between what the character wants and what they need.

Your protagonist won’t always achieve their goal, but – according to Yorke – they should get what they need. This is change, and change is what your story is actually about.

Five take home points

• Goals are a concrete outcomes you’re committed to achieving via your action(s). The best goals tend to be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-based (SMART goals).

• Early in your story, an event will occur, presenting your protagonist with a goal to pursue. It could be a mission, an opportunity, or a problem to solve. This is his ‘story goal’.

• To achieve this story goal, your protagonist will have to break it down into a series of steps. These steps are the basis for each of your protagonist’s ‘scene goals’.

• Protagonist’s are motivated to achieve their goals to protect their ‘self-concept’ – an ingrained self-image that people will often protect at any cost.

• Story is not just about a character’s pursuit of their goal. It is about the conflict between what the they want and what they need. Story is about change.

In the next post of this series, we’ll look at conflict. I look forward to it!

Do you have any helpful tips or techniques for writing scenes? If so please share in the comments below. Comments are encouraged!

And if you enjoyed this post, then please share it – you will help get more people writing. I am grateful to you for that!

The post Writing Scenes (Part 2) – All About Goals appeared first on writezu.com.