Victoria Wilcox's Blog

July 25, 2023

An Evening with Doc Holliday

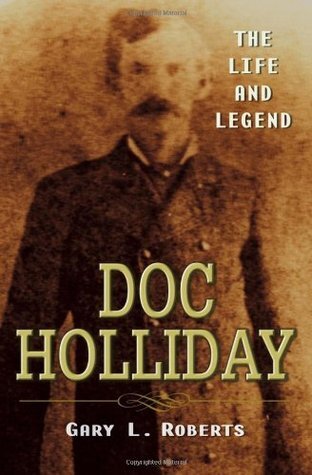

Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend

With Author Dr. Gary Roberts

When I first began researching and writing about Doc Holliday, I had the pleasure of being introduced by Doc’s family to historian Dr. Gary L. Roberts, then working on his own biography of the Western legend. Gary and I became good friends over the years as we shared our historical discoveries and discussed what each new bit of information meant in the context of Doc’s adventurous life. And although we were writing different sorts of books—Gary’s the scholarly biography Doc Holliday: The Life & Legend, and mine the historical novel trilogy The Saga of Doc Holliday—we were both working toward the same goal of bringing Doc’s true history to light, and I have appreciated Gary’s unfailing support of my own work.

In September of 2022, I had the privilege of hosting a long (nine hours!) interview with Gary in his hometown of Tifton, Georgia, where he was for years a professor of history at Abraham Baldwin College, named for another historic Georgia character and signer of the US Constitution. The event was produced by historian Eddie Lanham, and released as a series of nine video episodes on the Wild West History Association YouTube Channel. Titled “An Evening with Doc Holliday” and covering Doc’s life from his childhood in Civil War era Georgia to his last days in Colorado and beyond, the Doc Holliday interviews are both an in-depth exploration of Holliday’s life and a fascinating visit with a charming Southern gentleman.

Historic Menger Hotel

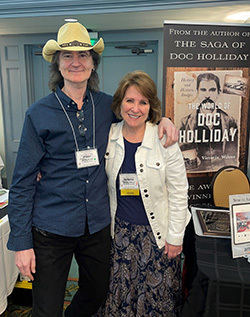

With Australian author Peter Brand at the WWHA Roundup

In July of 2023, the nine episodes of “An Evening with Doc Holliday” were recognized with a special award for contributions to Western history presented at the Wild West History Association Roundup in San Antonio, Texas. The event was held at the historic Menger Hotel across from the Alamo where Teddy Roosevelt recruited his Rough Riders during the Spanish American War, an appropriate place to honor a video series about Doc Holliday, as the hotel was already in operation when Doc himself passed through town. He may have even stopped by the Menger bar for a drink after a night of gaming in the saloons of San Antonio!

Wild West History Association Award

Menger Bar

Award plaques were presented to Dr. Gary Roberts, Eddie Lanham, and myself—a notable honor from an organization devoted to preserving and sharing the stories of Wild West history.

We are grateful!

WWHA YouTube Channel.

Fun Links:

Alamo

Menger Hotel

Roosevelt and the Rough Riders

Wild West History Association

The post An Evening with Doc Holliday appeared first on .

January 13, 2021

Leadville Takes a Shot

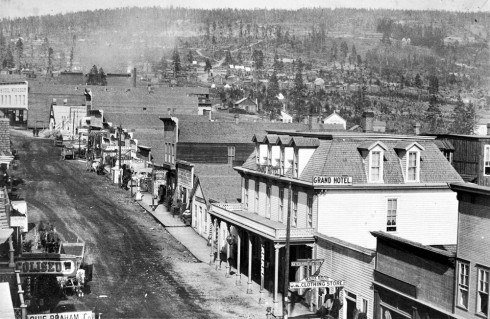

Leadville, Colorado circa 1882

Called the “Cloud City” because of its 10,000-foot elevation, Leadville, Colorado was both the highest city in the country and the richest silver camp in the world. By 1882, when Doc Holliday arrived, the Leadville mining district was producing $14 million worth of silver and the hills were warrened with mine shafts, cluttered with stamp mills, and overhung with the haze of smelters that never stopped burning. With all that money and a population of 40,000 and growing, Leadville seemed destined to take over Denver’s place as the state capital. The city’s main thoroughfare of Harrison Street was crowded day and night with coaches and carriages, ore wagons and delivery drays, foot traffic and fine horses and trains of burros bound for the mines. There were brick and stone sidewalks fronting tall business buildings, stores filled with every description of merchandise, a grand Opera House provided by Horace Tabor, and enough law offices to handle all the legal entanglements of claims and claim jumpers, mine deeds and multiple-owner partnerships. There were, in fact, nearly as many lawyers in Leadville as there were saloons—and there were nearly a hundred of those, making saloon-keeping the biggest business in town. And where there were saloons, there were all the lesser establishments that went along with them: gambling houses, dance halls, bordellos and opium dens.

Dr. Edward Jenner

1880’s Smallpox Victim

But the booming population also brought sickness, with pneumonia and smallpox stalking the city. There was no defense against pneumonia, which Doc caught twice during his Leadville winters, but there was a way to avoid catching the highly infectious smallpox that had killed millions around the world: vaccination, first introduced in 1796 by English doctor Edward Jenner. The doctor had observed that milkmaids who caught cowpox didn’t develop smallpox when exposed to that disease, and so worked to develop a method of inoculation that first used fluid from cowpox blisters and then from smallpox blisters (the term vaccination comes from the Latin word for cow, “vaca”). In 1853, England made vaccination for smallpox mandatory, saving the population from the symptoms of the dread disease: fever, headaches, nausea, searing pain in the back and raw sores in the throat, and eventually an infectious rash all over the body with blisters that stretched the skin to bursting. Unvaccinated, one third of victims died.

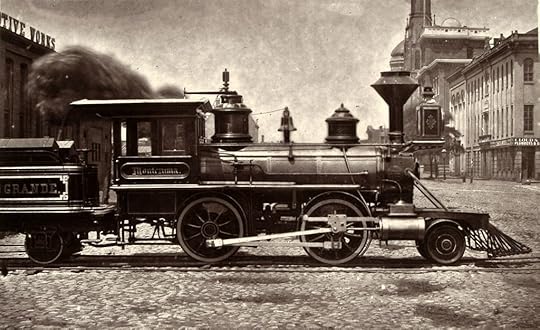

Denver & Rio Grande Locomotive

So, when a smallpox epidemic threatened Colorado in the winter of 1882-83, the answer was scientific: mass vaccination. At Leadville, the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad took on the job, holding a mandatory vaccination day for all railroad workers and offering free drinks for everyone who complied. The liquor clinched the deal, the workers rolled up their sleeves, and the spread of the smallpox slowed with only sixty-nine lives lost to the disease in Leadville that year.

19th Century Vaccination Kit

There is no record of whether Doc Holliday took advantage of the Denver & Rio Grande’s offer, but being a man of science himself as well as a gambler who liked to play the odds, he may very well have wagered on the vaccine. He later spoke of his two hard Leadville winters with pneumonia that left him weak and led to his only shooting affray in Colorado, but he never mentioned being ill with smallpox, the worldwide scourge that Dr. Jenner’s vaccine helped to eradicate.The post Leadville Takes a Shot appeared first on .

January 11, 2021

My Process

It’s the beginnings of things that interest me: Doc Holliday before he became a Western icon; a Caribbean pirate who started out as a wealthy plantation owner; a Native American Indian chief who was descended from Scots royalty. Then curiosity takes over and I become a researcher, digging into archives and visiting museums and libraries, interviewing family members and historians, traveling to the places where the characters lived and the action happened. As I study, the facts fall into something like a plot and a theme begins to appear. The information fills file cabinets and fleshes out a timeline of the character’s life. I turn the timeline into a skeletal chapter book, adding in my notes and the plot and action as far as I know it, so that before I begin the actual writing, there is something like a novel already waiting for me. You could print the pages and read through, and have a good idea of the storyline, the characterization, the ending. And then the real work starts.

Writing is a love-hate relationship for me. Sometimes it’s easy and the words flow and I love it. Sometimes I struggle for hours or days with a single paragraph and I hate it. I  never have classic writer’s block, running out of words. I have plot block, which is much worse, running out of story. It’s when I can’t figure out how to connect point A to point C that I really hate my life. And often it’s not just a leap from A to C that I have to maneuver, but from A to E by way of B, C, and D, which are the logical suppositions that take the story from the history we know at A to the history we know at E – everything along the way being only plausible conjecture. Being constrained by the history is often harder for me than having nothing but my imagination to guide the story. I can imagine all kinds of things. It’s imagining them within the confines of known history that is challenging. But somehow it all works out and the paragraphs turn into pages that turn into scenes that turn into chapters that turn into a book – or two or three.

never have classic writer’s block, running out of words. I have plot block, which is much worse, running out of story. It’s when I can’t figure out how to connect point A to point C that I really hate my life. And often it’s not just a leap from A to C that I have to maneuver, but from A to E by way of B, C, and D, which are the logical suppositions that take the story from the history we know at A to the history we know at E – everything along the way being only plausible conjecture. Being constrained by the history is often harder for me than having nothing but my imagination to guide the story. I can imagine all kinds of things. It’s imagining them within the confines of known history that is challenging. But somehow it all works out and the paragraphs turn into pages that turn into scenes that turn into chapters that turn into a book – or two or three.

(This is my desk at Mackinac Island, Michigan, where I hide away and write every fall. What you see is the total of my daily life on the island: a laptop and notes. Seems like a small world, until the story grows around me. I write in lots of places, but this is the coolest one!)

Because I write about historical characters I have the advantage of time, following the natural order of events. But although my storytelling is linear, in my mind the story is already a finished whole before I begin to write. It’s something like dropping a photograph into developing solution and watching it fade from nothing to everything all at once. It’s impossible to write everything all at once, however, so I put it down on paper chronologically, starting at the beginning while knowing what’s coming 200 pages from now, but having to wait until I can catch up with it. And it’s in the catching up that the magic happens, when the characters take on a life of their own and do things I hadn’t planned, where I find theme and symbolism and the spirit behind the action. I am often surprised while writing, sometimes laughing out loud, sometimes crying. There were many times I wanted to slap John Henry Holliday and tell him to grow up and act right. Then I wanted to turn to the other characters and explain him to them so they’d have some sympathy. When I write I am in the story myself, sometimes a participant, more often an interested observer taking notes.

characters take on a life of their own and do things I hadn’t planned, where I find theme and symbolism and the spirit behind the action. I am often surprised while writing, sometimes laughing out loud, sometimes crying. There were many times I wanted to slap John Henry Holliday and tell him to grow up and act right. Then I wanted to turn to the other characters and explain him to them so they’d have some sympathy. When I write I am in the story myself, sometimes a participant, more often an interested observer taking notes.

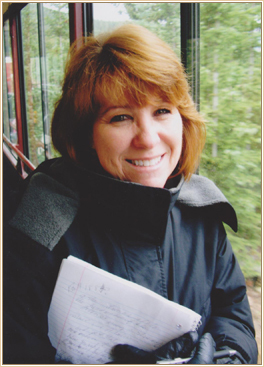

(This is me on the train to Leadville, Colorado. Note the spiral notebook in my hand. Can’t write well about a place until you’ve been there — and Leadville was a story-changer for me.)

And after years of research, writing, editing, and rewriting, I finally have a finished manuscript ready for submission. And then I start all over again on another book!

The post My Process appeared first on .

October 12, 2020

Designing Doc Holliday

One of the last—but most important—elements of book publishing is the design of the cover. A self published author may have complete control over cover design, while a traditionally published author (like yours truly) has a whole art and marketing department to do the work. With many creators taking part in the process, the final product may not reflect the author’s first intent, while still satisfying bookstore buyers and distributors.

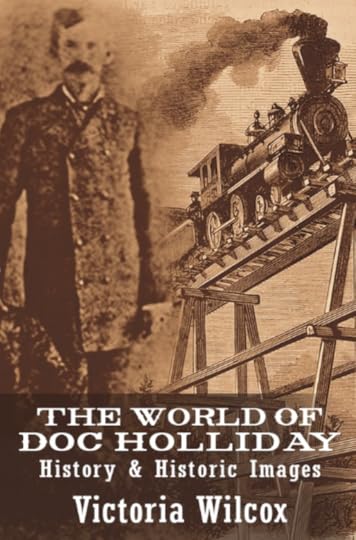

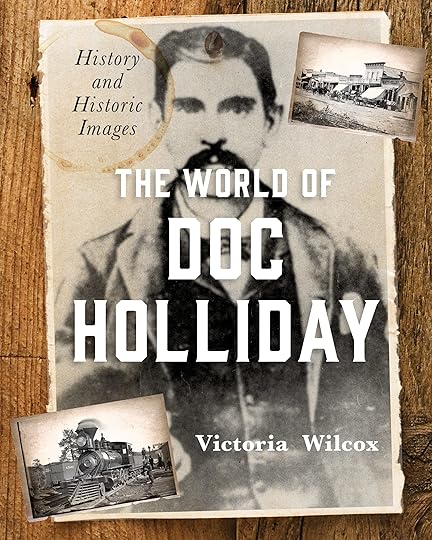

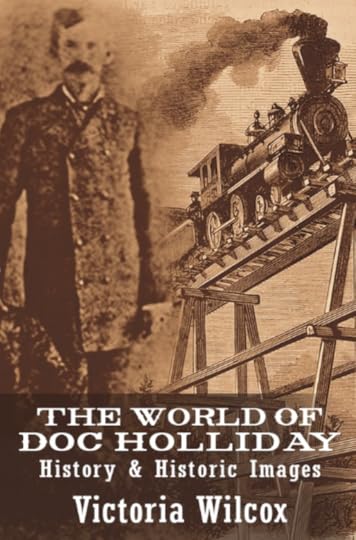

Such is the case in the cover of my new pictorial biography: The World of Doc Holliday: History & Historic Images. In my mind, since the book was inspired by Doc’s railroad travels across the country, a cover featuring an antique train would have been perfect. The first mock-up of my own suggested design combined both a train on a high trestle and a photo of Dr. John Henry Holliday taken in Prescott, Arizona, shortly before he moved to Tombstone, and sent to his family back home in Georgia—an elegant image of a traveling man in the era of the iron horse.

Such is the case in the cover of my new pictorial biography: The World of Doc Holliday: History & Historic Images. In my mind, since the book was inspired by Doc’s railroad travels across the country, a cover featuring an antique train would have been perfect. The first mock-up of my own suggested design combined both a train on a high trestle and a photo of Dr. John Henry Holliday taken in Prescott, Arizona, shortly before he moved to Tombstone, and sent to his family back home in Georgia—an elegant image of a traveling man in the era of the iron horse.

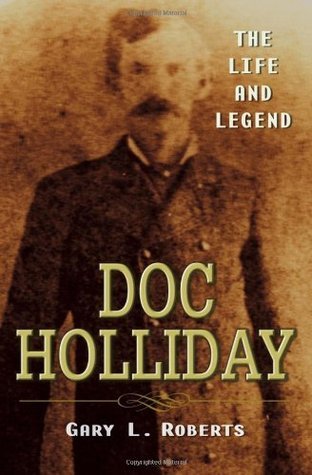

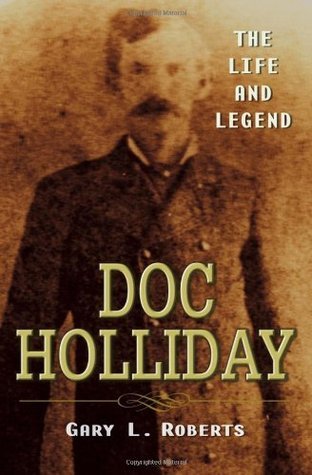

Only problem with my design suggestion was that the photo had already been prominently used on Dr. Gary Robert’s seminal and scholarly biography, Doc Holliday: The Life & Legend. The publisher didn’t want to confuse bookstore buyers or readers, so we had to let that great photo go. But what to use, instead?

Only problem with my design suggestion was that the photo had already been prominently used on Dr. Gary Robert’s seminal and scholarly biography, Doc Holliday: The Life & Legend. The publisher didn’t want to confuse bookstore buyers or readers, so we had to let that great photo go. But what to use, instead?

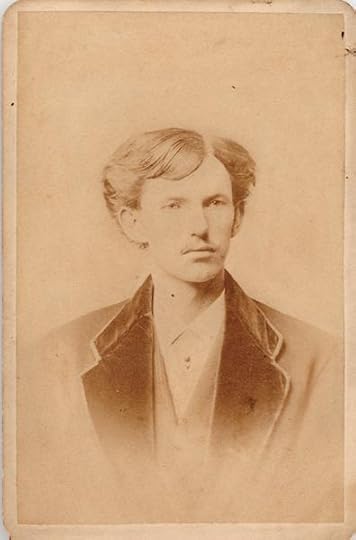

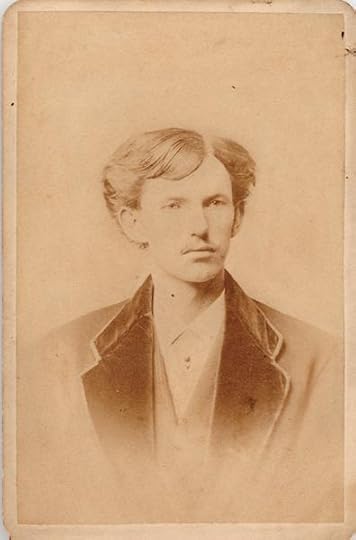

There are only a few well-documented photos of Doc, and none from his time in Tombstone or after. The only other family photo with clear provenance (trail of ownership) had been taken in Philadelphia when he was in dental school in 1871-72. Often referred to as the Graduation Photo, there is no actual indication of when during those years the photo was taken—it may have been when he first arrived in the city or anytime between then and when he left. And as a cover photo for this book about his adventures, he looks a little young and inexperienced for our well-traveled Doc.

There are only a few well-documented photos of Doc, and none from his time in Tombstone or after. The only other family photo with clear provenance (trail of ownership) had been taken in Philadelphia when he was in dental school in 1871-72. Often referred to as the Graduation Photo, there is no actual indication of when during those years the photo was taken—it may have been when he first arrived in the city or anytime between then and when he left. And as a cover photo for this book about his adventures, he looks a little young and inexperienced for our well-traveled Doc.

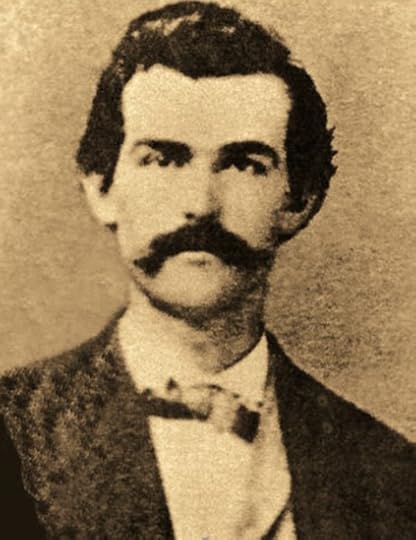

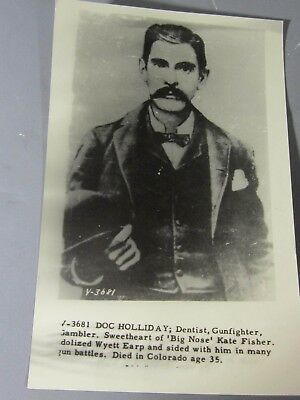

Another option might have been this photo that claims to be Doc in Dallas in 1873 and is one of my favorites: a much retouched and darkened image of a mustached man with the Holliday-family-trait attached earlobes and a penciled notation on the back, “J.H. Holliday, Dallas, 1873.” The photo comes from the Vincent Mercaldo (1850-1945) collection of more than 2,000 classic Western images, now housed in the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming. Mercaldo was an artist as well as a collector and could have done the retouching/darkening on this photo himself. The photo has no other provenance besides that penciled ID on the back, but was accepted for years and certainly could be him—though one family member declared that it positively was not Doc with no proof other than her own word for it, and she lived a couple of generations after him and never actually saw him.

Another option might have been this photo that claims to be Doc in Dallas in 1873 and is one of my favorites: a much retouched and darkened image of a mustached man with the Holliday-family-trait attached earlobes and a penciled notation on the back, “J.H. Holliday, Dallas, 1873.” The photo comes from the Vincent Mercaldo (1850-1945) collection of more than 2,000 classic Western images, now housed in the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming. Mercaldo was an artist as well as a collector and could have done the retouching/darkening on this photo himself. The photo has no other provenance besides that penciled ID on the back, but was accepted for years and certainly could be him—though one family member declared that it positively was not Doc with no proof other than her own word for it, and she lived a couple of generations after him and never actually saw him.

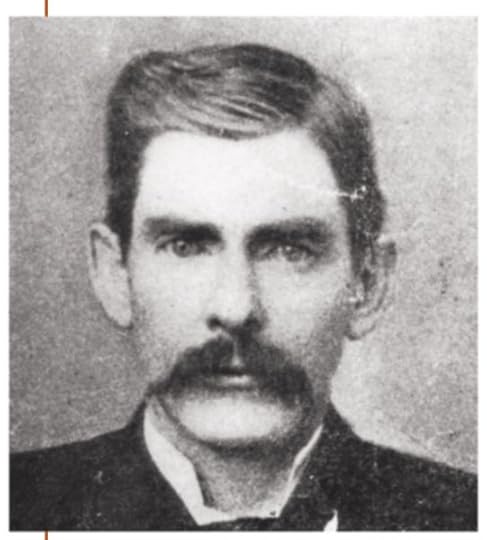

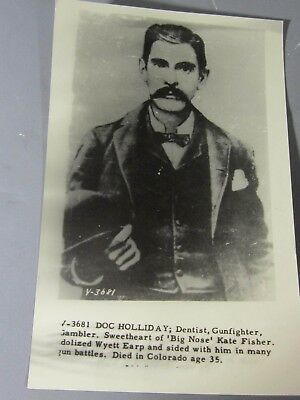

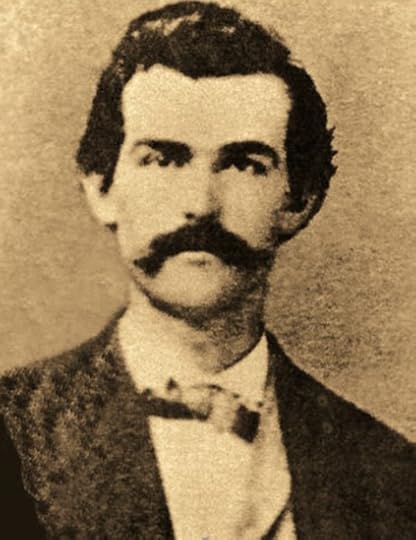

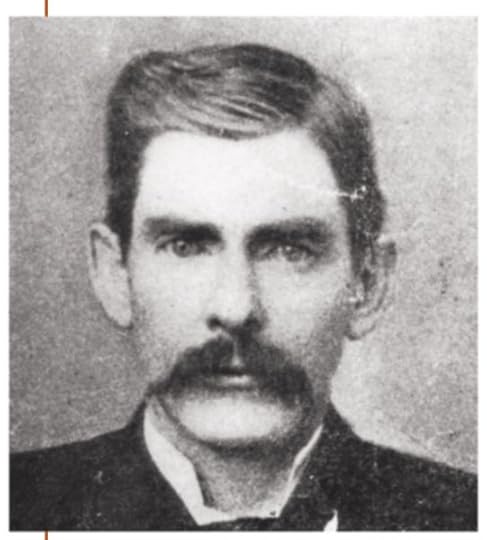

An image lacking provenance but with a good chance of being the real deal is this famous photo of a mustached man that appeared with a Bat Masterson article about Doc Holliday in “Human Life” Magazine in 1907. The photo appears to have been cropped for the article, and may have come from a larger, group photo. Wouldn’t it be interesting to know who was in that group? Unfortunately, we don’t know the whereabouts of the original, but the fact that Bat allowed its use with his article lends credence, and the fact that Wyatt’s later biographer, Stuart Lake, also used the photo in his Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, makes it even more likely. Lake captioned it: “This photograph, made by C. S. Fly in Tombstone, 1881, was the only one Doc Holliday ever had taken.” Lake may have been right about the Camillus Fly attribution (making the photo even more historic) but he was wrong about it being the only photo Doc ever had taken.

An image lacking provenance but with a good chance of being the real deal is this famous photo of a mustached man that appeared with a Bat Masterson article about Doc Holliday in “Human Life” Magazine in 1907. The photo appears to have been cropped for the article, and may have come from a larger, group photo. Wouldn’t it be interesting to know who was in that group? Unfortunately, we don’t know the whereabouts of the original, but the fact that Bat allowed its use with his article lends credence, and the fact that Wyatt’s later biographer, Stuart Lake, also used the photo in his Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, makes it even more likely. Lake captioned it: “This photograph, made by C. S. Fly in Tombstone, 1881, was the only one Doc Holliday ever had taken.” Lake may have been right about the Camillus Fly attribution (making the photo even more historic) but he was wrong about it being the only photo Doc ever had taken.

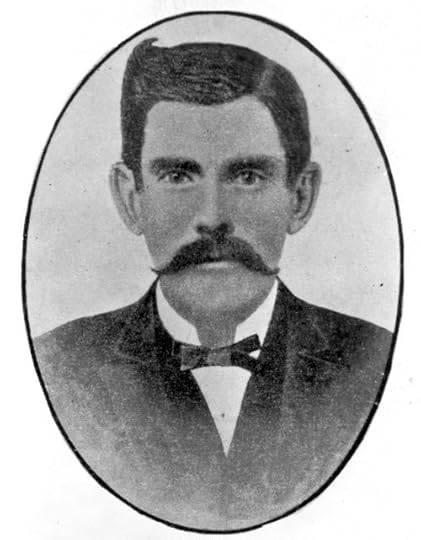

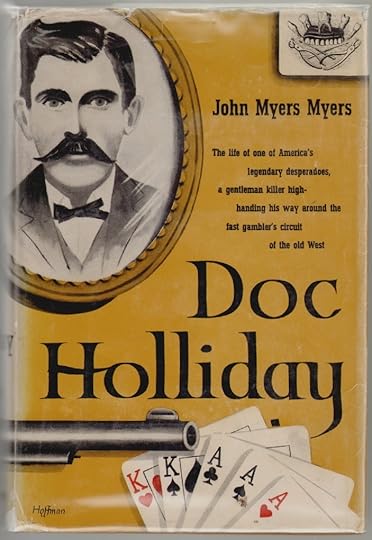

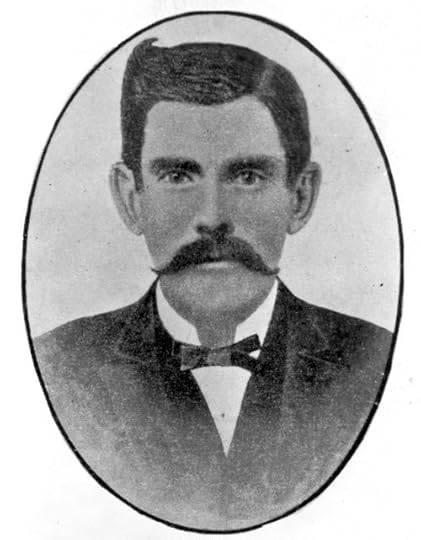

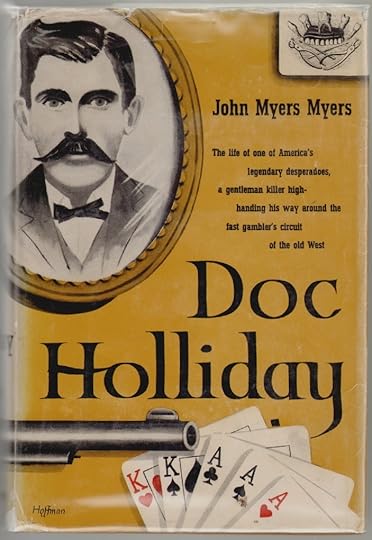

This retouched version of the C.S. Fly photo comes from the collection of Texas photographer Noah Rose (1874-1952) who made images of the people and places of the Southwest and added to his own work photos from other collections. By 1930, he was selling prints of his collection and supplying images to magazines. His Album of Gunfighters contained 300 pictures of outlaws and lawman of the West—including this image. Called the “Rose Photo,” it adds a curl to Doc’s now-dark hair, a narrow-trimmed mustache, and a drawn-in suitcoat. This is the image that inspired the cover of John Myers Myers 1955 bio, Doc Holliday.

This retouched version of the C.S. Fly photo comes from the collection of Texas photographer Noah Rose (1874-1952) who made images of the people and places of the Southwest and added to his own work photos from other collections. By 1930, he was selling prints of his collection and supplying images to magazines. His Album of Gunfighters contained 300 pictures of outlaws and lawman of the West—including this image. Called the “Rose Photo,” it adds a curl to Doc’s now-dark hair, a narrow-trimmed mustache, and a drawn-in suitcoat. This is the image that inspired the cover of John Myers Myers 1955 bio, Doc Holliday.

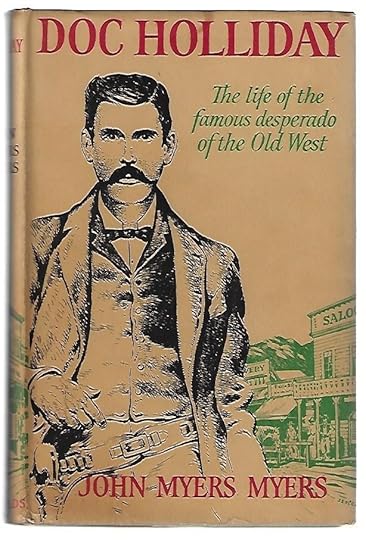

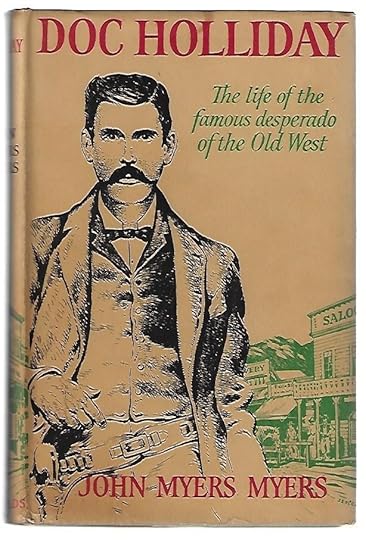

The English edition of Myers book, published in 1957, used an artist-drawn full-length version of the Rose Photo, with Doc wearing a side-slung holster and an ivory-handled pistol. Another artist-rendered version of the Rose photo shows him in the same pose as the English Myers book, but now holding a derby hat instead of fingering a pistol. And it was that drawing that my publisher’s design team chose for the cover of my new book, The World of Doc Holliday: History & Historic Images. Although it’s not a photograph of John Henry Holliday, as I would have preferred, the drawing was inspired by an actual photograph accepted by both Bat Masterson, who knew Doc personally, and by Wyatt Earp’s first biographer. So, with its own historical lineage, the image now seems a fitting choice for a bookfilled with historic images from the world of Doc Holliday. And, happily, the cover design still includes an antique train!

The English edition of Myers book, published in 1957, used an artist-drawn full-length version of the Rose Photo, with Doc wearing a side-slung holster and an ivory-handled pistol. Another artist-rendered version of the Rose photo shows him in the same pose as the English Myers book, but now holding a derby hat instead of fingering a pistol. And it was that drawing that my publisher’s design team chose for the cover of my new book, The World of Doc Holliday: History & Historic Images. Although it’s not a photograph of John Henry Holliday, as I would have preferred, the drawing was inspired by an actual photograph accepted by both Bat Masterson, who knew Doc personally, and by Wyatt Earp’s first biographer. So, with its own historical lineage, the image now seems a fitting choice for a bookfilled with historic images from the world of Doc Holliday. And, happily, the cover design still includes an antique train!

Interesting Links:

Buffalo Bill Historical Center: https://centerofthewest.org/

Doc Holliday by Bat Masterson: https://www.legendsofamerica.com/we-hollidaybymasterson/2/

Doc Holliday Live/Doc Photos: https://dochollidaylive.biz/doc-photos/

Camillus Fly: Frontier Photographer https://www.legendsofamerica.com/law-camillusfly/

The post Designing Doc Holliday appeared first on .

Images of Doc Holliday

One of the last—but most important—elements of book publishing is the design of the cover. A self published author may have complete control over cover design, while a traditionally published author (like yours truly) has a whole art and marketing department to do the work. With many creators taking part in the process, the final product may not reflect the author’s first intent, while still satisfying bookstore buyers and distributors.

Such is the case in the cover of my new pictorial biography: The World of Doc Holliday: History & Historic Images. In my mind, since the book was inspired by Doc’s railroad travels across the country, a cover featuring an antique train would have been perfect. The first mock-up of my own suggested design combined both a train on a high trestle and a photo of Dr. John Henry Holliday taken in Prescott, Arizona, shortly before he moved to Tombstone, and sent to his family back home in Georgia—an elegant image of a traveling man in the era of the iron horse.

Such is the case in the cover of my new pictorial biography: The World of Doc Holliday: History & Historic Images. In my mind, since the book was inspired by Doc’s railroad travels across the country, a cover featuring an antique train would have been perfect. The first mock-up of my own suggested design combined both a train on a high trestle and a photo of Dr. John Henry Holliday taken in Prescott, Arizona, shortly before he moved to Tombstone, and sent to his family back home in Georgia—an elegant image of a traveling man in the era of the iron horse.

Only problem with my design suggestion was that the photo had already been prominently used on Dr. Gary Robert’s seminal and scholarly biography, Doc Holliday: The Life & Legend. The publisher didn’t want to confuse bookstore buyers or readers, so we had to let that great photo go. But what to use, instead?

Only problem with my design suggestion was that the photo had already been prominently used on Dr. Gary Robert’s seminal and scholarly biography, Doc Holliday: The Life & Legend. The publisher didn’t want to confuse bookstore buyers or readers, so we had to let that great photo go. But what to use, instead?

There are only a few well-documented photos of Doc, and none from his time in Tombstone or after. The only other family photo with clear provenance (trail of ownership) had been taken in Philadelphia when he was in dental school in 1871-72. Often referred to as the Graduation Photo, there is no actual indication of when during those years the photo was taken—it may have been when he first arrived in the city or anytime between then and when he left. And as a cover photo for this book about his adventures, he looks a little young and inexperienced for our well-traveled Doc.

There are only a few well-documented photos of Doc, and none from his time in Tombstone or after. The only other family photo with clear provenance (trail of ownership) had been taken in Philadelphia when he was in dental school in 1871-72. Often referred to as the Graduation Photo, there is no actual indication of when during those years the photo was taken—it may have been when he first arrived in the city or anytime between then and when he left. And as a cover photo for this book about his adventures, he looks a little young and inexperienced for our well-traveled Doc.

Another option might have been this photo that claims to be Doc in Dallas in 1873 and is one of my favorites: a much retouched and darkened image of a mustached man with the Holliday-family-trait attached earlobes and a penciled notation on the back, “J.H. Holliday, Dallas, 1873.” The photo comes from the Vincent Mercaldo (1850-1945) collection of more than 2,000 classic Western images, now housed in the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming. Mercaldo was an artist as well as a collector and could have done the etouching/darkening on this photo himself. The photo has no other provenance besides that penciled ID on the back, but was accepted for years and certainly could be him—though one family member declared that it positively was not Doc with no proof other than her own word for it, and she lived a couple of generations after him and never actually saw him.

Another option might have been this photo that claims to be Doc in Dallas in 1873 and is one of my favorites: a much retouched and darkened image of a mustached man with the Holliday-family-trait attached earlobes and a penciled notation on the back, “J.H. Holliday, Dallas, 1873.” The photo comes from the Vincent Mercaldo (1850-1945) collection of more than 2,000 classic Western images, now housed in the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming. Mercaldo was an artist as well as a collector and could have done the etouching/darkening on this photo himself. The photo has no other provenance besides that penciled ID on the back, but was accepted for years and certainly could be him—though one family member declared that it positively was not Doc with no proof other than her own word for it, and she lived a couple of generations after him and never actually saw him.

An image lacking provenance but with a good chance of being the real deal is this famous photo of a mustached man that appeared with a Bat Masterson article about Doc Holliday in “Human Life” Magazine in 1907. The photo appears to have been cropped for the article, and may have come from a larger, group photo. Wouldn’t it be interesting to know who was in that group? Unfortunately, we don’t know the whereabouts of the original, but the fact that Bat allowed its use with his article lends credence, and the fact that Wyatt’s later biographer, Stuart Lake, also used the photo in his Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, makes it even more likely. Lake captioned it: “Thisphotograph, made by C. S. Fly in Tombstone, 1881, was the only one Doc Holliday ever had taken.” Lake may have been right about the Camillus Fly attribution (making the photo even more historic) but he was wrong about it being the only photo Doc ever had taken.

An image lacking provenance but with a good chance of being the real deal is this famous photo of a mustached man that appeared with a Bat Masterson article about Doc Holliday in “Human Life” Magazine in 1907. The photo appears to have been cropped for the article, and may have come from a larger, group photo. Wouldn’t it be interesting to know who was in that group? Unfortunately, we don’t know the whereabouts of the original, but the fact that Bat allowed its use with his article lends credence, and the fact that Wyatt’s later biographer, Stuart Lake, also used the photo in his Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, makes it even more likely. Lake captioned it: “Thisphotograph, made by C. S. Fly in Tombstone, 1881, was the only one Doc Holliday ever had taken.” Lake may have been right about the Camillus Fly attribution (making the photo even more historic) but he was wrong about it being the only photo Doc ever had taken.

This retouched version of the C.S. Fly photo comes from the collection of Texas photographer Noah Rose (1874-1952) who made images of the people and places of the Southwest and added to his own work photos from other collections. By 1930, he was selling prints of his collection and supplying images to magazines. His Album of Gunfighters contained 300 pictures of outlaws and lawman of the West—including this image. Called the “Rose Photo,” it adds a curl to Doc’s now-dark hair, a narrow-trimmed mustache, and a drawn-in suitcoat. This is the image that inspired the cover of John Myers Myers 1955 bio, Doc Holliday.

This retouched version of the C.S. Fly photo comes from the collection of Texas photographer Noah Rose (1874-1952) who made images of the people and places of the Southwest and added to his own work photos from other collections. By 1930, he was selling prints of his collection and supplying images to magazines. His Album of Gunfighters contained 300 pictures of outlaws and lawman of the West—including this image. Called the “Rose Photo,” it adds a curl to Doc’s now-dark hair, a narrow-trimmed mustache, and a drawn-in suitcoat. This is the image that inspired the cover of John Myers Myers 1955 bio, Doc Holliday.

The English edition of Myers book, published in 1957, used an artist-drawn full-length version of the Rose Photo, with Doc wearing a side-slung holster and an ivory-handled pistol. Another artist-rendered version of the Rose photo shows him in the same pose as the English Myers book, but now holding a derby hat instead of fingering a pistol. And it was that drawing that my publisher’s design team chose for the cover of my new book, The World of Doc Holliday: History & Historic Images. Although it’s not a photograph of John Henry Holliday, as I would have preferred, the drawing was inspired by an actual photograph accepted by both Bat Masterson, who knew Doc personally, and by Wyatt Earp’s first biographer. So, with its own historical lineage, the image now seems a fitting choice for a book

The English edition of Myers book, published in 1957, used an artist-drawn full-length version of the Rose Photo, with Doc wearing a side-slung holster and an ivory-handled pistol. Another artist-rendered version of the Rose photo shows him in the same pose as the English Myers book, but now holding a derby hat instead of fingering a pistol. And it was that drawing that my publisher’s design team chose for the cover of my new book, The World of Doc Holliday: History & Historic Images. Although it’s not a photograph of John Henry Holliday, as I would have preferred, the drawing was inspired by an actual photograph accepted by both Bat Masterson, who knew Doc personally, and by Wyatt Earp’s first biographer. So, with its own historical lineage, the image now seems a fitting choice for a book

filled with historic images from the world of Doc Holliday. And, happily, the cover design still includes an antique train!

[image error].

April 10, 2020

Talking Doc!

Thanks to author and radio host Doug Dahlgren for having me on his show on the Artist First Radio Network! We spent a lively hour discussing all things Doc Holliday, from his romantic connection to Gone with the Wind to who played the best Doc in the movies. Here’s some highlights, and a link to listen to the whole show!

“It was the greenest place I’d ever seen…” said Doc Holliday, reminiscing about his Georgia home in the film “Wyatt Earp.” How did a Georgia house lead to the writing of the Saga of Doc Holliday books?

“She was all I ever wanted…” said a dying Doc Holliday to Wyatt Earp on the film “Tombstone.” The girl he was talking about was his cousin, Mattie Holliday. What’s the truth behind the romantic story?

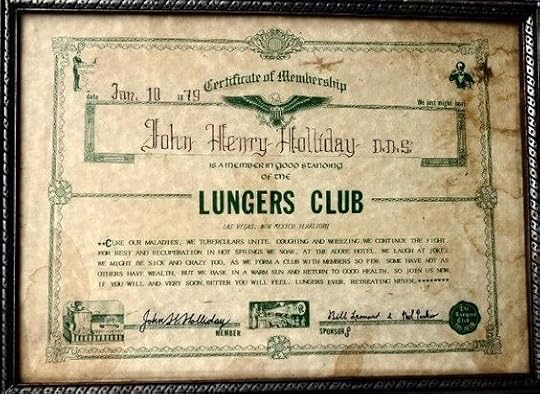

“You ain’t nothin’ but a skinny lunger…” said an angry Ed Bailey to a coughing Doc Holliday over a game of cards. What was Doc’s disease—and was it really the reason he left Georgia for the Wild West?

“I’m your Huckleberry…” said Doc Holliday to Johnny Ringo in the film “Tombstone.” Who played him best in the movies? And which movie script got closest to the real Doc Holliday?

Click here to listen to the whole show!

The post Talking Doc! appeared first on .

August 4, 2019

The Power of Point of View

(Guest Post on Sarah Johnson’s “Reading the Past” Blog 2013)

Sarah Johnson’s wonderfully written review of Inheritance, the first book in my historical novel trilogy, Southern Son: The Saga of Doc Holliday points out one of the challenges in writing fiction set during the American Civil War and Reconstruction: the difficulty of dealing with the “inherent racism” of the time. Although the Southern Confederacy was fighting for more than slavery in its war on the Federal government, the perpetuation of the “peculiar institution” was at the core of the fight. So a writer telling a story set in the Old South has to acknowledge the central issue of the era, even if that issue isn’t a central theme of the book.

It would be tempting to insert one’s modern perceptions into the narrative, commenting on or criticizing the racist attitudes of the times. Such editorial comment, however, puts a distance between the reader and the characters and detracts from the sense of time and place of the story. How, then, to accurately show the social ills of the Old South without seeming to approve of them? Without some negative commentary the story might seem to celebrate the institution of slavery.

My solution to this literary dilemma was found in telling the entire story of Southern Son in the Third Person Limited point of view, never leaving the mind of John Henry Holliday. The reader sees only what John Henry sees, hears, or learns, which means that there is no escape from witnessing, and being party to, his 19th-century attitudes. He doesn’t consider himself racist (the term may not even have existed in his vocabulary), and he offers no apology for having such thoughts—which the reader then has to share.

Of course this is sometimes uncomfortable, as it is meant to be. The narrator doesn’t need to tell us that John Henry’s attitudes are wrong, and the writer certainly doesn’t need to step in and make the point. The reader will draw those conclusions, being uncomfortable with the things John Henry says and does but unable to get away from those things. The effect is a very personal experience with the mind and heart of a 19th-century man in the last days of the Old South.

Yet, in spite of his many flaws or perhaps because of them, John Henry remains a very sympathetic character. When he does wrong, we want him to do right. When he fails, we want him to succeed. Such personal emotion for an imagined character is the power of the Third Person Limited point of view, putting us solely in the heart of the protagonist and no one else. We care about his life, because his life is all we have.

The second book in the trilogy, Gone West, introduces John Henry to the historical character of Barney Ford, a former runaway slave turned wealthy hotel owner. When Holliday unthinkingly comes to the man’s defense, it’s a telling action that his racial attitudes are changing. By the end of the third book, The Last Decision, Holliday himself comments on the racist attitudes of others, as he finally learns what the reader always knew. And through the Third Person Limited point of view, in the end, we share in his victories.

But Southern Son isn’t about race, any more than John Henry’s life was about racist thinking. It’s a story of heroes and villains, dreams lost and found, families broken and reconciled, of sin and recompense and the redeeming power of love—all seen through the eyes of an American legend.

The post The Power of Point of View appeared first on .

The End?

Finishing the manuscript is just the start of the Business of Writing. (From a blog post for Bookmasters.com)

So you’ve finally finished your masterpiece, read and edited and proofed and reread the carefully typed manuscript, and now it’s ready for the two most wonderful words in a writer’s vocabulary: The End! And soon, you’ll be querying agents and sending off submissions, receiving an offer of representation, and watching a bidding war between all the top publishers in your genre. Hey, it could happen!

But before it does and before you type “The End” at the bottom of your final page, you’ve still got some work to do. Because finishing the manuscript is just the start of the business of writing. Now you have a synopsis to write, and you may find it even harder than writing the work on which it’s based. And doing it right may mean the difference between landing a book deal and languishing in the slush pile of an agent’s office. Even if you’re intent on self-publishing, a synopsis is elemental to the success of your book.

So what’s a synopsis? And how do you write one? And what do you do with it once it’s done?

According to Peter Rubie, CEO of Fine Print Literary in New York, “A synopsis is a narrative summation of your fiction, telling the story rather than showing it.” It’s your story as told to a child, a simple description of the beginning, middle, and end of the plot and how the characters make it happen. If your story were a house, a synopsis is the way it would look without all the décor, emptied of furniture and rugs and knickknacks until it’s nothing but walls and doors and a roof overhead.

But why build a house only to deconstruct it? Because those agents and editors that you hope to impress are looking for something more elemental than a beautiful writing style—they’re looking for a story they can sell and they don’t have much time to find it. With a synopsis, they can make a quick judgment about whether your book is the right fit for them. And for you as a writer, the benefit of gutting your careful construction down to its framing is that you can see where things are out of plumb or not nailed in just right. Are the plot progressions logical? Have you left a character with no way to get from point A to point C? Did the story in your head really make it onto paper? Without all the interior decorating, you can see where the house may have flaws—and fix them before you put it on the market.

Then once you’ve corrected the flaws and your book is signed and sold, the synopsis will serve another purpose, becoming the basis for book blurbs, press releases, and talking points for author interviews. The graphic artist will use it as inspiration for your cover design. The publisher and distributor will use it in their marketing to bookstores and libraries. For most of the publishing professionals who deal with your book, your synopsis IS your story. The same is true even if you choose to self-publish your work, as you will still need blurbs and press releases and talking points as you take on the tremendous task of doing your own marketing.

Publishing Consultant Jane Friedman has a good step-by-step on how to write a synopsis at https://www.janefriedman.com/how-to-write-a-novel-synopsis/. As you did with your book, take your time to do it well, and you’ll have finally earned the right to proudly say: “The End!”

The post The End? appeared first on .

August 1, 2019

The Power of Story

(Keynote Address at the Blue Ridge Writer’s Conference 2014)

He was Georgia’s best-known Western legend, infamous in his own time and famous in ours for the part he played in the Gunfight at the OK Corral, becoming a celebrity in literature and film, with his character featured in more than 70 movies and TV shows. She was Georgia’s first superstar, her every activity chronicled in newspapers and magazines, with crowds of admirers camping out on her lawn. At Davison’s Department Store, where she’d gone to buy a dress for a big premiere, she was followed into the dressing room by fans who pulled at her hair and tore off her clothes as souvenirs. Yet neither of them was looking for notoriety; they just wanted to live ordinary lives. It was the power of the story that make their lives extraordinary. And amazingly, Doc Holliday and Margaret Mitchell, author of Gone with the Wind had a family connection. And to explain that surprising bit of Georgia history, I first need to share some of my own history. You might call that the story behind the story.

And my story starts here with my own Mormon pioneer ancestors who crossed the Great Plains in covered wagons to settle the American West in the days of the real cowboys and Indians. One of my grandfathers became president of the Cattleman’s Association in Portland, Oregon. The other left the silver mines of Eureka, Utah behind to mine a different kind of fortune in early pioneer Hollywood. And that’s when my mother’s cousin came to stay with the family and became a film actress, costarring in a series of movie Westerns, like Silver on the Sage and Hidden Gold with cowboy actor Hopalong Cassidy. Her name was Ruth Rogers—that’s her on the right playing the pretty but plucky love interest. She even did a film with a young John Wayne in The Night Riders.

I grew up hearing stories of Ruth’s Hollywood career, and my favorite of those stories was one about her real-life suitor, the actor Errol Flynn, who was filming his own Hollywood Western, Dodge City, at the time. It was a lavish Technicolor production that featured a romance between Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland, who would later that year play Melanie in Gone with the Wind. But the real Errol Flynn wasn’t quite as upstanding as his movie hero character. One night after having had a few too many drinks at the bar, Errol came to my family’s home looking for Ruth, who was out for the evening—so he tried to pick up my mother, instead, who was barely into her teens at the time. She thought he was creepy! So, having that sort of back lot view of Hollywood, I didn’t have the same kind of movie star fascination that other young girls did, but I always loved big dramatic stories, especially those with a sense of history. So it’s likely not surprising that I started college as a history major before changing to English and making a career as a writer. But it was a move to the South that tied real history together with movie history for me, when my husband’s career took us to Georgia. “Go West, Young Man,” said Horace Greely. “Go South, Young Woman,” said Ron Wilcox, first to Atlanta for four years of dental school, then south to Fayette County where I found a Southern house with a Western history I had never heard before.

It was a classic Southern beauty, a white columned Greek Revival style mansion standing on a tree shaded street just off the Fayetteville town square. Although I didn’t know if it were actually historic—it could have been one of those mid-20th century colonial reproductions like the ones scattered around Los Angeles—somehow I knew from the first time I saw it that it was special and that someday I’d have something to do with it. Maybe I’d buy it and open a theme restaurant: “Belle Watling’s Place,” perhaps, playing on the Gone with the Wind look of it, although I don’t like to cook all that much and I never wanted to own a restaurant. And being a young mother back then, I didn’t really have time to pursue the thought. Then my parents came to Georgia for a visit and wanted to see something historic. I took them to see Macon and Savannah, both filled with wonderful old houses and lots of history. But my father wondered if there wasn’t something historic right there in Fayette County. So I made a phone call to the local historical society to ask about the white-columned house with the long windows and the wide veranda, and got the surprising answer that the house was not only authentically old, circa 1855, but was built by the uncle of the famous Doc Holliday, who used to play there as a child.

“You mean THE Doc Holliday?” I asked, amazed, “from the OK Corral?”

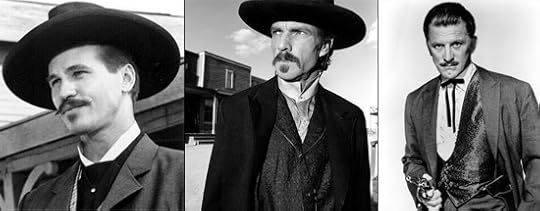

With my Western heritage and history background, I knew a little something of the dangerous dentist from Georgia who’d had his own Hollywood career in movies like the classic John Ford western My Darling Clementine with Henry Ford as lawman Wyatt Earp and Victor Mature as a hard-drinking medical doctor from Boston named Doc Holliday. Or the somewhat more factual Gunfight at the OK Corral, with Burt Lancaster as Wyatt Earp and a Southern Doc Holliday played by a young Kirk Douglas. Or the epic adventure Wyatt Earp, starring Kevin Costner with a very skinny Dennis Quaid as a very irritable, and irritating Doc Holliday (by the end of the movie I just wanted him to hurry up and die!). Or the fan favorite Tombstone, with Kurt Russell as Wyatt Earp and Val Kilmer as a dapper Doc Holliday. But if I ever gave Doc Holliday a thought beyond the movie images, it wasn’t set against the background of a white-columned mansion in Georgia. Yet there he was, a young boy during the Civil War, coming to visit with his Holliday cousins in Fayetteville, in a house that looked like it was right out of Gone with the Wind. Which, in fact, it was. Because for a time the house was used to board students of the local private school, the Fayetteville Academy, a school mentioned in the very first chapter of Gone with the Wind. According to Margaret Mitchell, “Scarlett…had not willingly opened a book since leaving the Fayetteville Academy…”

Of course, there were other Southern Belles who attended the Fayetteville Academy in those long-ago days, including a girl named Annie who was a whole lot like Scarlett O’Hara. Like Scarlett, Annie’s family lived on a big cotton plantation in neighboring Clayton County. Like Scarlett, Annie’s father was a feisty Irish immigrant named Gerald. Like Scarlett, Annie’s mother had green velvet drapes hanging in her parlor windows. And like Scarlett, Annie moved to Atlanta and survived the Civil War with a little bit of grace and a whole lot of gumption. Who does that sound like? Sounds like Scarlett! But there was one rather major difference between the two girls. Scarlett was fictional while Annie was real. Her father wasn’t Gerald O’Hara, but Phillip Fitzgerald, and her mother who owned those green velvet drapes wasn’t Ellen, but Eleanor—and she was Margaret Mitchell’s grandmother.

This is Margaret Mitchell at her writing desk here in the Atlanta apartment building where she wrote Gone with the Wind, and where she insisted that none of her characters were based on real people. And there’s a reason for that. Mitchell’s father was a copyright attorney, and he warned her that she was likely be sued by family members who didn’t like their stories being told. But although Mitchell was always careful to say that her characters were not based on real people, some of them were clearly inspired by real people. But there was one family member who was more than just inspiration. She was Annie Fitzgerald’s cousin, which made her Margaret Mitchell’s cousin twice removed. She was an elderly nun living in Atlanta when Mitchell went to visit her, asking permission to name a character in the book after her. “Just make her a nice person,” the nun said. And who’s the nicest person in Gone with the Wind? So now you know the cousin’s name: Sister Melanie, and the character named after her was Melanie Hamilton, Ashley Wilkes’ wife.

This is Melanie as portrayed by Olivia de Havilland in the film version of Gone with the Wind. And this is the real Sister Melanie before she became a nun and was known as Mattie Holliday. And amazingly, Mattie Holliday too had a connection to the white-columned Holliday House, as the owner was her uncle and she was one of the cousins who often visited there. And her favorite of those cousins was a boy named John Henry. According to family stories, he and his cousin Mattie were close as children and sweethearts when they were older. He was nineteen-years old when he went away to dental school in Philadelphia, and that’s where he got the nickname “Doc” Holliday. He practiced dentistry in and around Atlanta for awhile, then went West for reasons that are still uncertain. But some say it was a tragic love affair with his cousin Mattie that sent her to the convent and him running far from home and into a life of legendary Western adventures. So you might say that Melanie from Gone with the Wind was in love with Doc Holliday from the OK Corral, like the Old South meeting up with the Wild West and falling in love.

So if you think, like I did, that the Holliday House looks like something out of Gone with the Wind, you’re right. In fact, it looked so much like Gone with the Wind that Margaret Mitchell is said to have visited at the house and suggested it as a filming site for the movie. Of course, Hollywood wanted something grander, and came up with their own version of Scarlett O’Hara’s upcountry Georgia farmhouse and gave us this magnificent mansion, which was actually just a two-sided set piece with a pair of those native Georgia birds, the white peacock in the yard. But in spite of its literary and legendary connections, there was talk of tearing down the Holliday House to make way for that thing that all cities need: a new parking lot.

So I did what any lover of history and old houses does: I formed a community group and then a non-profit organization to save the Holliday House and turn it into a museum of history. And that’s how I became founding director of the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House Museum, named after the three famous Georgia families who lived there over the years. We opened to the public in July of 1996, on the day the Olympic torch came through Fayetteville on its long run toward Atlanta. And I learned how hard it is to run a small museum, using every creative opportunity for publicity and funding. My volunteers and I gave house tours and ladies’ group talks and cemetery walks. We put on Old South Balls and held auctions. We hosted spooky evenings of Southern ghost stories in the dark and unrestored rooms of the Holliday House. I wore my blue velvet hoop skirts so often that the children at our local elementary school thought I was Mother Goose. A clairvoyant who came to the house hoping to see dead people thought I was the ghost of the Holliday House. “The lady in blue!” she cried as I drifted down the staircase to the breezeway between the twin parlors. “That’s the woman who haunts the Holliday House!” She thought she’d made the paranormal discovery of the century. I thought, “Maybe someday. But I’m not dead yet!” And I still had work to do.

Part of that work was telling the story of the Holliday House everywhere I could: in interviews with newspaper and TV reporters, in local and Western magazines, at government meetings and other museums sites. And soon the story had grown into the start of a historical novel, and I knew just what it would be: part Gone with the Wind, part Lonesome Dove, the story of how a Southern boy became a Western legend. It would be Doc Holliday’s story the way his cousin Mattie might have told it, a Doc Holliday never seen before. For as Mattie said, “He was a much different man than the one of Western legend.” Only problem was, Mattie didn’t elaborate on her comment. How was he different than the legend? Why was he different? And what exactly was the legend?

Short story of the legend is this: Doc Holliday was a Georgia born dentist who was diagnosed with the fatal lung disease called consumption (tuberculosis) shortly after finishing dental school, and was told he had only a few months to live if he didn’t relocate to the high, dry plateau of the Western United States. So he packed his bags and took the train to Dallas, Texas, where he quickly tired of dentistry and made a new life as a gambling gunfighter. Depending on the who’s telling the story, he was either a great shot with a long list of dead men to his count, or a terrible shot who missed every enemy. Since there’s no record of those shootings, it’s anyone’s guess. But all the stories agree that his fatal diagnosis made him fearless, as he’d rather die in a gunfight with his boots on than die in bed. Meeting lawman Wyatt Earp was the high point of his Western life; taking up with a dance hall girl named Kate Elder was the low point. And fighting alongside the Earps in the famous gunfight at the OK Corral was the best thing he ever did. He and Wyatt were bosom buddies ever after, and Wyatt wrote a touching tribute to him before he died, not with his boots on, but in bed in a sanitarium in the Colorado mountains.

And almost everything I just told you turned out to be not true. But that was the legend and all I had to go on when I started writing. So I started there, planning to use the family history I’d learned at the Holliday House, along with some of the anecdotal information that couldn’t be proven, but seemed to fit. For his Western life, I’d just dramatize the legend as it was already told in several biographies. But I had barely gotten started when I came up against a problem. When I tried to make a timeline based on the several biographies about his life, I discovered that the lines on the timelines didn’t match, the facts didn’t agree—in fact, the facts likely weren’t facts at all. As Mattie had said, he was a much different man than the one of Western legend, and the legend was mostly wrong. And I came to the realization that if I were going to write about the real Doc Holliday—which was what I wanted to write, real history brought to life—I was going to have to find him first.

So thus began, not the couple of year of writing I had envisioned, but 18 years of research and writing as I followed Doc Holliday everywhere he went. First all over Georgia, from Griffin, where he was born in the last days before the Civil War; to Fayetteville, where his family gathered at the Holliday House; to Jonesboro, the setting of Gone with the Wind where Mattie’s family lived; to Valdosta, where his father refugeed ahead of the advancing Yankee army; to Atlanta, where he practiced dentistry after the War and lived in a big Victorian house with his Holliday cousins; to Savannah, where he took ship and sailed away to dental school. Then I followed Doc Holliday’s story across the country: to Philadelphia, St. Louis, Pensacola, Galveston, Dallas, Denver, Trinidad, Pueblo, Las Vegas, Prescott, Tombstone, Tucson, Leadville, New Orleans, Glenwood Springs. I went everywhere Doc Holliday had been and discovered that what Mattie had said of him was true: he was indeed a much different man than the one of Western legend. As he said in his own words, “Some few of us pioneers are entitled to credit for what we have done. We have been the fore runners of government. If it weren’t for me, and a few like me, there might never have been any government in some of these towns.”

By the time I was done writing his story, it filled three books, because his life was epic. It went from the Gone with the Wind territory of Civil War and Reconstruction to the Wild West and the edge of the modern era. And although the story is huge, it’s very personal, as well, the story of John Henry Holliday. And I was very honored to be named 50th Georgia Author of the Year for Inheritance, the first book in the saga. Gone West, the second book, came out last year and is doing well, and now I’m looking forward to the release of The Last Decision next month. Doc Holliday’s story has changed my life. But it’s also changed the towns where his story began.

This was the Holliday House in Fayetteville when I first saw it, an old dowager of a place with peeling paint and cracked windows, its history forgotten and its future looking bleak. Without the story it held of a Western legend and a relationship to Gone with the Wind, without the community interest those stories ignited, the house would likely not be standing still, and a Georgia historic site would be lost. But because of the story, this old house became this new museum, visited by history lovers from all over Georgia and around the world. Because of the story, the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House is now protected as a site on the National Register of Historic Places. And because the story had something to do with the old Fayetteville Cemetery there are now annual Cemetery walks and a project by the City of Fayetteville to beautify the cemetery grounds and the graves of the ancestors of Doc Holliday and Margaret Mitchell. Their story, the story that inspired my books, has changed Fayetteville. But it took someone telling the story to make it happen. And the same thing happened in his hometown of Griffin.

This is the Griffin building that was John Henry Holliday’s inheritance, and that inspired the title for the first book in the Southern Son trilogy. Old folks in town remembered hearing that his dental office space had been located on the second floor, with a painted sign in the window: J.H. Holliday, D.D.S. But because of the movies filled with images of gunfights and drunken brawls a more modern generation wasn’t interested in saving his history, and then just forgot his history, and the old building was just getting older. But as the story of Doc Holliday’s real life started to be told, things in Griffin started to change, and the old inheritance building was sold and restored and became first a club with a Wild West-style saloon in the basement, and now Doc Holliday’s, with a beautiful memorial plaque marking the site. It’s the first of six memorial plaques erected around the city, marking important places from the life of a historic Griffin character. I was in Griffin recently, doing some photography of the inheritance property, when a woman working in a store across the street got curious.

“What are taking pictures of?” she asked, as there didn’t seem to be anything special going on.

“Doc Holliday’s dental office,” I replied, and then told her about the building across the street from her store. She listened, and then said something extraordinary: “Wow! I’ll never look at that building the same way again. I won’t think of Griffin the same way again.” The story hadn’t just changed what she thought of Doc Holliday; it changed what she thought of the place where she lived. Because of the story, Doc Holliday’s hometown has changed its opinion of him, of their own history, of their own potential. Now, in addition to the memorials, there’s a bus tour and a proposed trolley to take visitors around. There’s a new festival in the planning, radio shows, newspaper articles. The stories we tell have power. Even, sometimes, the stories that aren’t true.

When I was directing the Holliday House, I got a phone call from a well-known folklorist and author of ghost story books. She was working on a new book about Georgia ghosts and wondered what stories I might have to share about the Holliday House. But although we did tours of the old cemetery and told literary ghost stories at Halloween, the Holliday House isn’t haunted, so I had nothing to tell her. Instead, I told her the real story of the house, of Doc Holliday and his cousin Mattie and their interesting relationship to Margaret Mitchell. We had a nice conversation, she thanked me, and that was the end of it. Or so I thought.

Until two years later, when I was in Savannah having dinner with my husband and friends at the historic old Pirate House restaurant. There in the gift shop I found the ghost-story author’s new book about Georgia ghosts, and hoping that I might find in it some new stories for our Halloween haunted tales, I bought it and eagerly started reading—and discovered to my surprise the story of the haunting of the Holliday House by the ghost of Doc Holliday, quoting me! Of course, I called the author and complained about how she’d used my name to make it look like I had told this completely make-believe story about the ghost of Doc Holliday.

“Oh that’s all right,” she said, “everybody knows ghost story books are just make-believe, anyhow. No one thinks they’re real hauntings!”

Really? Well, tell that that to the family that drove across the country from California just to see the ghost of Doc Holliday! I wasn’t happy having to explain to them that Doc didn’t haunt the Holliday House and hadn’t been back since he’d left as a child. But at least it was just a book, and eventually it would go out of print and be forgotten. But then came Amazon and Google, and now the story is all over the Internet: Doc Holliday haunts the Holliday House. I’ve tried to correct the misinformation, but I usually get an answer like, “You’re just not believer!” I’m the one the story started with or didn’t start with. But try as I might, I can’t make that story go away, and the Holliday House is now haunted by a story.

So what is it about stories that makes them so powerful, able to change people and places, and even sometimes, the truth? Stories are just words, after all, just creative writing. Right? But they’re more than that. According to recent breakthroughs in Neuroscience, the study of the brain, the stories we hear and read and tell actually change our brain chemistry. As Jonathan Gottschall, author of The Storytelling Animal notes, “The human mind was shaped for story, so that it could be shaped by story.” And some of the most powerful stories we tell are the ones we tell ourselves, whether they be memoirs of a painful past that we’re still holding onto, or hopeful romances, or fantasies of what might yet be. Since we are shaped for story, since the stories we tell ourselves can literally change us, we need to make sure that those stories are not only true, but useful—that we’re not driving across the country to see a ghost who doesn’t exist. Do the stories we tell ourselves hold us back, or push us forward in a good direction?

Take, for instance, the stories told by three writers who wanted to become authors—not just the stories in the books they wrote, but the stories they were telling themselves.

Let’s call the first writer Joanne. She started writing a book on a napkin in a restaurant, because she had an idea and it just had to get out. It took her five years to finish her story, and when she was done she had the good fortune of a good friend who was a book agent, and Joanne believed that her book would be published. But in spite of her friend’s honest efforts, the only publisher they could find was a small house that did mostly schoolbooks, and even that publisher would only print 500 paperback copies of the book, because most books don’t sell more than 500 copies. But Joanne still believed that her book could be a success.

John was another hopeful writer who had even worse luck finding a publisher. He couldn’t get anyone to look at his book, and finally had to pay to print it himself, the original self-publishing. But still believing that what he had was what people would want to read, he loaded his boxes of books in the back of his station wagon and drove them around to all the little bookstores he could find, begging them to take a few books on consignment. It wasn’t the big publishing deal he’d hoped for, and still believed he could land, but at least it was a start and he was willing to keep working at it.

Kathryn’s book was a memoir about her family’s life in the 1960’s, and though it was well-written, it just didn’t seem like the kind of thing the publishing world was waiting for. She kept a running total of the agents who rejected her query letter: sixty and counting. But the story she told herself was that she just needed to keep trying and eventually she’d be successful. And it’s a good thing she listened to her own story and didn’t give up, because agent #61 thought there might be something to the book and took her on as a client, and Kathryn Stockett’s The Help became a New York Times Bestseller and a major motion picture, winning an Academy Award for its leading lady.

As for John, he kept writing, and when his second novel found a publisher, his self-published first novel was picked up as well and became the New York Times #1 Bestseller: John Grisham’s A Time to Kill, then a major motion picture starring Sandra Bullock and Matthew McConaughey, and now a play on Broadway. He believed in his work, and it worked.

As for JoAnn, her little book of only 500 copies did a bit better than the publishers had thought it would, as the first of a young adult series that turned the world of publishing upside down and became J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter, and the Harry Potter movies, and “The Wizarding World of Harry Potter” at Universal Studios in Florida.

The point of all this isn’t that your book can or even should become a theme park or a hit movie. Or maybe it can. But it won’t happen if you don’t believe in your own story, both the one you’re writing and the one you’re living. So what’s your story? Is this the year you will TRY to finish that book, or the year you WILL finish it? Is this the year you will THINK about finding an agent or WISH you could find a publisher? Or is this the year you will do the WORK it takes to become a published author?

When I won the Georgia Author of the Year Award, someone asked me what had kept me writing for all those 18 years. The answer was, I kept writing because I had a story to tell and I knew how it ended, and I couldn’t stop until I got there. I believed in the story I was writing, and I believed in a story about myself, as well: that I had been given a gift and I was meant to use it. More than that, I was meant to write this particular story and my whole life had led me to it. In my family, we like to joke that my birthdate was a sign: I was born on November the 8th, Margaret Mitchell’s birthday and the date that Doc Holliday died.

You have stories to tell as a writer, but the most important story you will ever tell is the one you tell yourself about who you are and what you can accomplish. Believe in your gift, believe in yourself. Don’t let false stories hold you back or send you chasing ghosts. And don’t stop until you get to the end! Because THE END of a story is a very nice place to be!

The post The Power of Story appeared first on .

July 23, 2019

Why Doc Holliday Killed Johnny Ringo in “Tombstone”

Val Kilmer as Doc Holliday challenges Johnny Ringo in their last duel.

It’s the dramatic final duel between Doc Holliday and his alter-ego nemesis, Johnny Ringo, in the classic Western film “Tombstone,” as Doc shoots Ringo dead and comments wryly, “the strain was more than he could bear.” Although that’s not what really happened (Doc wasn’t even in Arizona when Ringo died), there’s a reason screenwriter Kevin Jarre wrote it that way: this is drama not documentary, and the rules of Westerns demand that the sort-of good guy kill the bad guy in the end.

Screenwriter Kevin Jarre and Val Kilmer

And in this Western, Doc Holliday and Johnny Ringo have not just one, but three duels—and all of them portray Doc as the defender of his one-true friend, Wyatt Earp.Screenwriter Kevin Jarre who wrote “Tombstone,” and Val Kilmer who made Jarre’s Doc Holliday character a movie Western icon. Read True West’s tribute to Jarre here .

DUEL #1: In the first duel, a faro-dealing Wyatt is threatened by the cowboys, until Doc steps in and bests Ringo in a fast-draw contest: Ringo’s gun versus the drunk dentist’s whiskey cup.

Lego version of the Doc and Ringo cup duel. Watch the scene here.

DUEL #2: In the second duel, a drunk Ringo challenges Wyatt on the streets of Tombstone, until Doc steps in and announces, “I’m your Huckleberry, fightin’s just my game,” and the cowboy backs down. For what the famous phrase means, see my blog post here.

Doc’s famous line, now appearing everywhere. Find this poster here.

DUEL #3: In the third and final duel, Wyatt is on his way to meet Ringo in a shooting match he will surely lose, until Doc steps in and finishes off the cowboy with one bullet to the head. Three times Doc Holliday has defended Wyatt Earp from Johnny Ringo, showing his loyalty, while fulfilling the “good guy kills the bad guy” rule of Westerns. And it’s only fair that Doc gets to kill Ringo, as Wyatt kills his own nemesis, the cowboy leader, Curly Bill Brocious.

Ike Clanton, the real boss of the cowboys.

But that, too, is just movie reel drama—in the real world, Ike Clanton was the cowboy leader (a much smarter man than the film’s character) while Curly Bill was just a junior associate. But Wyatt didn’t kill Ike (who got away to be killed another day by another man), he killed Curly Bill, so Kevin Jarre smartly made Curly Bill the head bad guy to be killed by head good guy Wyatt. Which is one of the reasons we all love “Tombstone”: it’s good literature as well as good drama, with all the characters doing just what we want them to do and right winning out in the end. “Tombstone” isn’t history; it’s Historical Fiction, a drama based on historical events but telling a literary story.

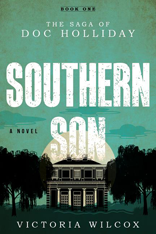

Which is also what Doc fans will find in my award-winning historical novel trilogy The Saga of Doc Holliday which dramatizes Doc Holliday’s life from his boyhood in the Civil War South to his dealings in Tombstone and beyond. It’s a history-based retelling of Doc’s adventures, bringing the past to life like “Tombstone” brought the events surrounding the O.K. Corral gunfight to life, becoming a classic Western. Isn’t that a daisy?

Read the “Tombstone” script here.

Order The Saga of Doc Holliday from your favorite bookseller.

Pre-Order Now!

Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Books•A•Million

Pre-Order Now!

Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Books•A•Million

Pre-Order Now!

Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Books•A•Million

The post Why Doc Holliday Killed Johnny Ringo in “Tombstone” appeared first on .