Hanne Blank's Blog

November 10, 2016

A Badly Broken (Ethical) Code: Thinking About Operational Medicine in a Post-9/11 USA

Since the infamous terror attacks on the United States of September 11, 2001, the US has been engaged in a protracted, haphazard, and complicated national conversation about the ethics of bodily treatment. This discourse has encompassed many aspects of how the bodies of others are and should be treated, among them racial/ethnic profiling, mandatory body scans or searches, apprehension of suspected terrorists, the holding and treatment of prisoners, and, perhaps most vividly, interrogation and torture. All of this has taken place in a time in which intense emotions of urgency, panic, xenophobia, and (nominally defensive) aggression have frequently gripped military leaders, legislators, and the public alike. Almost all of the discussion, for reasons which are intimately connected with the emotional and urgent tenor of the times, has been reactive, that is to say, it has centered around revelations of ethical and human rights abuses born of the reactive “war on terror” declared by former President George W. Bush. Amidst the headlines about waterboarding, “enhanced interrogation,” and the US’s global network of CIA “black sites” and military installations, however, are a set of crucial questions about the medical profession and its practitioners. They center specifically around the use of medical knowledge as “intelligence” in the pursuit of the politically motivated mistreatment of human beings, most pointedly with regard to torture.

These are not new questions; no questions about medical involvement in the inhumane treatment of human bodies can be considered so at least since the Holocaust and subsequent Nuremburg trials. But they are fiendishly persistent and seemingly resistant to resolution. International agreements and professional regulation have demonstrably failed to consistently create positive ethical responses among medical providers in “intelligence” and military or “national security” settings. New moves toward conceptualizing “operational” medicine and “dual loyalty” ethics are compromised from inception. What, if anything, can bioethics take from all this that might help ameliorate this profoundly unsettling and evidently wicked dilemma?

Let us begin at the top, as most pieces on the topic in the bioethical literature do: the United States has both robustly ignored and baldly circumvented international diplomatic agreements and regulatory guidelines about the treatment of bodies, particularly those of detainees. Particularly since the George W. Bush administration, the United States’ military and intelligence organizations have openly flouted the Geneva Conventions, World Medical Assembly guidelines (Declaration of Tokyo), and the United Nations Convention against Torture in any number of ways. Not least of these has been the audacious sophistry of creating a new category for “war on terror” prisoners, “unlawful combatants,” deliberately creating a method by which (suspected) members of groups not signatory to international conventions and treaties need not be treated by the terms of said agreements, thus removing the nominal barrier to human rights violations by medical personnel.

Despite our shock at these revelations there is little percentage, from a bioethics standpoint, in rehashing the particulars; that train has already left the proverbial station. Rather we might, in relation to this, consider the significant historical and political science literature on American exceptionalism and the century of precedent that begins with the Congressional refusal to permit the United States to become signatory to the League of Nations in the wake of World War I. American violation of international human rights agreements is often compared to that of Nazi Germany, but as Michael Ignatieff argues, the pattern of U.S. refusal of international pacts has a longer history of its own that continues to inform present-day practice and thus warrants a deep critique. Applied bioethics exists in culturally and historically specific contexts, not in the convenient and supposedly universal vacuum of philosophical thought experiments, and clearly no amount of high-minded and well-intentioned international treatymaking can make it otherwise. It seems reasonable in this arena to call on bioethics to expand its understanding of ways historical precedent shapes expectations of US participation in international agreements, and perhaps also influences a sense of indemnity, for some, in their nonparticipation.

The range of roles professional associations have played in this ongoing ethical failure similarly call on bioethicists to become cannier about Realpolitik. While it is of course the job of bioethics to try to evaluate and maintain normative – which is to say ideal – visions and versions of how bodies will be treated by individuals and institutions, the bioethics literature that commented on the now-infamous 2005 American Psychological Association ethical guidelines betrays some troublesome lack of discernment on the part of some bioethicists. To wit, although the problematically open-ended language of the APA’s 2005 ethical guidelines – created with the explicit input of important Department of Defense officials, as it turned out — attracted the critique of a few ethicists such as Kenneth Pope and Thomas Gutheil, who blasted them as overly permissive and devoid of enforceable restrictions in the September 2008 Psychiatric Times. Some, such as Harvard’s Mildred Solomon, went on the record describing the 2005 APA guidelines as “impressive” and “unambiguous.” On the heels of the 2015 Report to the Special Committee of the Board of Directors of the American Psychological Association: Independent Review Relating to APA Ethics Guidelines, National Security Interrogations, and Torture, which confirmed APA collusion with the Department of Defense to create loose ethical guidelines the Department of Defense could exploit, one is left combing the acknowledgements footnotes of bioethics papers, working out the presence of factions within the ranks of commentators. This seems, particularly given the fact that as of January 2016 the Pentagon has asked the APA to reconsider its post-expose ban on the involvement of psychologists in “national security” interrogations, to call for a vastly heightened awareness and watchfulness on the part of bioethicists of the political and disciplinary pressures potentially and actually being placed on healthcare practitioners.

Quis custiodiet ipsos custodies? becomes an even more important question for bioethicists in light of the developing literature on “dual loyalty.” There are of course multiple ways in which loyalty to the nation-state may complicate loyalties to professional and international humanitarian ethics: emotion, fear, economics, simple expedience. Dual loyalty scholarship, however, approaches this set of complications as if it were inevitable rather than an artifact of particular operations of the state. “Operational” psychology and medicine, a new way of describing practitioners who work “in support of national security, public safety, and corrections,” takes dual loyalty and a related concept, “mixed agency” (having professional obligations to two or more entities simultaneously, such as a branch of the military and also the American Psychological Association) as its baseline. The presumption that such dilemmas will inevitably exist for practitioners is an artifact of the Second World War and its Cold War aftermath, the institutionalization of social science and medical authority as part of both military-industrial machine and the welfare state. Given that this is an arguable reality for many practitioners, it seems reasonable to ask bioethicists to critically include both the presumption of plural loyalties and the acknowledgement of dual loyalty’s potentially irreconcilable demands. That this will inevitably generate criticisms of situational ethics cannot be helped, only clearly and uncompromisingly addressed: bioethics’ role as arbiter and provider of normative standards depends upon a willingness to aggressively seize that role in the face of acknowledged and explicated conflicted priorities.

See e.g. M. Gregg Bloche and Jonathan Marks, “Doctors and Interrogators at Guantanamo Bay,” New England Journal of Medicine vol. 353 no. 1 (2005), 6-8; Peter Clark, “Medical Ethics at Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib: The Problems of Dual Loyalty” Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics (Fall 2006), 570-580; Vincent Iacopino and Stephen Xenakis, “Neglect of Medical Evidence of Torture in Guantanamo Bay: A Case Series” PLoS Medicine 8(4) (2011) doi:10.1371/ journal.pmed.1001027; Steven Miles, “Medical Ethics and the interrogation of Guantanamo 063” American Journal of Bioethics vol. 7 no. 4 (2007), 5-11; Jerome Singh, “American Physicians and Dual Loyalty Obligations in the ‘War on Terror’” BMC Medical Ethics vol. 4 no. 4 (2003), DOI: 10.1186/1472-6939-4-4.

Peter Clark, “Medical Ethics at Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib: The Problems of Dual Loyalty” Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics (Fall 2006), 572.

Michael Ignatieff, American Exceptionalism and Human Rights (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009).

Michael McCarthy, “American Psychology Association Colluded with Pentagon and CIA to Protect Interrogation Program, Report Finds” The British Medical Journal 351 (July 2015), doi:10.1136/bmj.j3805.

Kenneth Pope and Thomas Gutheil, response to “Detainee Interrogations: American Psychological Association Counters, but Questions Remain,” Psychiatric Times vol. 25 no. 10 (September 2008), 58-59.

Mildred Solomon, “Healthcare Professionals and Dual Loyalty: Technical Proficiency is Not Enough,” MedGenMed vol. 7 no. 3 (2005), 14.

David Hoffman, Danielle Carter, Cara Viglucci Lopez, et al., Report to the Special Committee of the Board of Directors of the American Psychological Association: Independent Review Relating to APA Ethics Guidelines, National Security Interrogations, and Torture (September 4, 2015). Accessed at http://www.apa.org/independent-review/revised-report.pdf, October 30, 2016.

To wit, Mildred Solomon thanks Stephen Behnke, sitting ethics director of the American Psychological Association at the time of the creation of the 2005 ethics guidelines, by name in one footnote. A footnote in Psychiatric Times, on the other hand, explains that Kenneth Pope resigned from the APA after the issuance of the 2005 guidelines after 29 years of membership, citing an inability to support the new guidelines in good conscience.

James Risen, “Pentagon Wants Psychologists to End Ban on Interrogation Role” New York Times (online) January 24, 2016. Accessed at http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/25/us/politics/pentagon-wants-psychologists-to-end-ban-on-interrogation-role.html?partner=bloomberg October 28, 2016.

Carrie Kennedy and Thomas Williams, eds., Ethical Practice in Operational Psychology: Military and National Intelligence Applications (Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2011)

Timothy Jeffrey, Robert Rankin, and Louise Jeffrey, “In Service of Two Masters: The Ethical-Legal Dilemma Faced by Military Psychologists,” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice vol. 23 no 1 (1992), 91-95; Frederick McGuire, Psychology Aweigh: A History of Clinical Psychology in the United States Navy, 1900-1988 (Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 1990).

October 26, 2016

What Gauge Needle Do You Like For Your Arthrocentesis? Expert Patients, Paternalism, and the Politics of Clinical Knowledge

Why do medical practitioners only very rarely ask patients about their desires in regard to the specific clinical details of treatment, and what does this have to do with the relationships of knowledge, legitimate medical authority, and medical paternalism? It is my contention that knowledge, both on the part of the patient and of the practitioner, is a central part of where lines between “paternalistic” and “legitimate” imposition of medical authority are drawn. The politics of knowledge, and their connections to issues like competency, oppression, status, and power, have an important but underexplored role in the discussion on paternalism. Considering the question of what thresholds medical practitioners expect to encounter when it comes to patients’ clinical knowledge provides us with a useful window into this issue.

For the purposes of this discussion I will first recognize that the definition of “paternalism” is contested, but also assume based on the historical evidence presented by the history of medicine as practiced in the US on the enslaved, women, children, LGBTQ individuals, African-Americans, and other politically and economically disenfranchised groups that Daniel Groll is correct in asserting that paternalism is not limited to cases in which one person exerts authority in order to act against the will of another. History shows that this “acting against” is not required for paternalism to take place. Rather I concur with Groff that person X acts paternalistically toward person Y when, for the sake of what X perceives to be Y’s good, X does not take Y’s will or desires into consideration or decides against those desires.

In examining the role of knowledge in determining where this line of consideration of Y’s wishes – Y in this case being the patient, X being the medical provider – I feel that it is instructive to look at the nature of informed consent as it is currently construed, and specifically, at the point(s) in the process of medical interactions consent is sought. The mundane reality is that despite our culture’s current foregrounding of informed consent, countless treatment decisions are routinely made by providers not only without considering patient desires but in fact without any patient input whatever. This authority is exerted on the basis of practitioners’ presumptions about the limits, whether actual or assumed or merely desired, of patients’ knowledge. Patients and practitioners alike, however, become aware of these presumptions about the limits of patients’ knowledge when the presumed knowledge boundary is breached. When this happens, it declares the existence of a real but typically unarticulated divide between a realm in which decisions where the imposition of medical authority in decision-making is presumed unproblematic and by definition uncompromised by potential paternalism, and a realm in which greater patient knowledge renders the imposition of practitioner authority a more complicated matter.

This is a separate problem in many ways from the problem of informed consent. Patients are usually involved in decisions about whether treatment will happen, and in a large-picture way about the kind of treatment that will be pursued. Because these are the customary realms in which informed consent is sought, these are also the customary realm in which patient knowledge is encouraged and provided. A patient with a potentially infected knee replacement might, for example, be asked whether she will consent to having the synovial fluid in the knee tapped and cultured, or whether she is content to simply begin a course of antibiotics and see whether the condition improves. Regardless of which path the patient chooses, however, the clinical particulars will not be up to her. Aside from checking her chart for possible allergies, she will not be asked her opinions on the type or dosage of drugs she might be prescribed. Nor, if she agrees to the arthrocentesis, will she be asked what gauge of needle she prefers for the aspiration. Why not? Because her knowledge and expertise on these matters is presumed to be limited or nonexistent. That is the doctor’s bailiwick. The tacit assumption is that there are aspects of medical care about which it is at least appropriate and possibly desirable that the patient have no opinion, with the result that the practitioner will have few to no barriers to imposing what they perceive to be an appropriate choice.

But some patients do have (and express) knowledgeable opinions about such issues. The patient with the knee problem might be a practicing nurse, or might be on her second knee replacement, or both, and have well-informed reasons for preferring one needle gauge over another for arthrocentesis on her own knee. Such high-knowledge patients, sometimes called “expert patients,” are virtually absent from the literature on doctor-patient communication, which tends to focus on patient information-seeking and the relationship of effective provider communications to patient compliance. Despite this lack of representation in the literature, some patients do become very well educated about their needs and preferences through extensive patient experience, clinical education programs, or self-directed research. Inevitably, some patients are themselves medical professionals. Some patients, like the friend whose knee and expertise I have metaphorically borrowed to illustrate this essay, are both medical professionals and patients with extensive personal experience of their medical condition(s) and past clinical interventions.

The limited body of research on high-knowledge patients confirms anecdotal reports that the “expert patient” upsets the presumed hierarchies of knowledge and authority in clinical settings, with adverse results to the patient and their quality of care. The answer to the question asked in the title of a BMJ Open study, “What happens when patients know more than their doctors?” appears to be not only social awkwardness, but the labeling of the “expert patient” as “noncompliant,” and sometimes to suboptimal or even dangerous outcomes including unnecessary hospitalizations and sudden changes to treatment regimens as medical practitioners seek to (re)establish what they feel is their rightful authority over the clinical situation.

There is, in short, an underdetermined but provably extant point at which it is presumed that patients will lack the knowledge to participate in medical interventions, allowing provider authority to take over, and this is perceived as appropriate and proper to the medical environment. When such a customary imposition of authority is made in regard to a patient whose knowledge exceeds the presumed norm, however, it may well be a paternalist move in actuality. A practitioner’s right to impose decisions is typically presumed in technical clinical contexts on the basis of the practitioner’s presumed superior knowledge. The oft-cited “reasonable patient standard” appears, in other words, to encompass a “reasonable” expectation of patient ignorance: a “reasonable patient” may know enough to consent to treatment and yet possess no knowledge specific enough to have formed desires about many aspects of that treatment. Customarily, practitioners are not obligated to ensure that patients acquire that level of knowledge or even to ask if the patient wishes to do so.

Thus, although it is customary to acknowledge “competence” as a baseline for a patient’s participation in medical decision-making, this primarily means competence to understand information one is given and to make decisions based on that information. But knowledge is literally power in contexts such as medicine wherein power is derived from expertise. Competence to receive and understand a limited subset of medical information is not – and cannot be permitted to masquerade as – the only knowledge dynamic in the examining room. When a patient’s lack of knowledge is to be remedied by the practitioner, the informing of a patient’s consent is necessarily one means by which practitioners may routinely retain and enhance authority. If the potential for abuse of authority is what concerns us about paternalism, then we must be concerned about this. But we must also be concerned, perhaps especially so, about what happens when a high-knowledge patient challenges the boundaries around territory that has been customarily the practitioner’s own.

This is particularly relevant given the multiple ways in which the politics of knowledge intersect with the politics of sociocultural, economic, and legislative enfranchisement and disenfranchisement. Suffice to say that the politics of knowledge at once undergird and reproduce the basis on which the desires, experiences, and knowledge of marginalized groups are routinely discounted, dismissed, and overridden: it is easier to behave paternalistically (and more probable that such paternalism will be overlooked) toward members of groups perceived as less likely to be competent, knowledgeable, or both. As a bellwether for the potential of problematic paternalism amongst medical practitioners, then, it may be that a practitioner’s ability to negotiate the challenge of the high-knowledge patient can tell us more than their performance as information supplier and consent broker with patients whose competence is stipulated but whose knowledge is no greater than the presumed norm.

Notes:

Daniel Groll, “Paternalism, Respect, and the Will,” Ethics 122, no. 4 (July 2012): 695.

For discussions of medical paternalism as practiced in regard to some of the groups mentioned please see e.g.: John C. Fout, ed. Forbidden History: The State, Society, and the Regulation of Sexuality in Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992); G. Sophie Harding, ed. Surviving In The Hour of Darkness: The Health and Wellness of Women of Colour and Indigenous Women (Calgary, Alberta: University of Calgary Press, 2005); John Hoberman, Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical Racism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012); Rosemary Pringle, Sex and Medicine: Gender, Power, and Authority in the Medical Profession (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Groll, 694.

Rosamund Snow, Charlotte Humphrey, Jane Sandall, “What Happens When Patients Know More Than Their Doctors? Experiences of Health Interactions After Diabetes Patient Education: A Qualitative Patient-Led Study” BMJ Open 2013; 3:e003583. Accessed 15 September, 2016. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013- 003583. See especially the discussion of “consequences,” pages 5-6. Additionally, see David Badcott’s “The Expert Patient: Valid Recognition or False Hope” Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy 8, no. 2 (2005): 173-178, in which Badcott dismisses (173) “the notion of ‘the expert patient’ as informed co-decisionmaker” as a “well-meaning but rather vacuous aspiration similar to that of informed consent.”

This post was originally written in the context of a bioethics seminar at the Emory University Center for Ethics. My thanks to Dr. Jonathan Crane and Kathy Kinlaw for their constructive feedback.

October 14, 2016

Doing Better with Disability Accommodations in the Higher Ed Classroom

Whether as a student or an educator, every semester that I’ve spent in the classroom has given me an opportunity to think a little bit more about the issue of disability in the classroom. I’ve watched instructors handle it poorly, I’ve seen them handle it well. I’ve listened to the complaints of fellow students about dismissiveness, hostility, inconsistency, and inappropriate demands for medical details from professors. I’ve certainly heard a few from fellow instructors about students abusing disability accommodations to try to get out of doing assignments and attending classes, and once in a blue moon even to try to bully instructors into grades changes.

One would like to think that disability accommodations in the college or university classroom would be a simple matter of a student presenting documentation of a disability and asking for particular reasonable accommodations to be made, and the instructor doing their best to make them. This is how it has largely been presented to me in teacher training seminars and in disability accommodations talks: a matter-of-fact transaction between a student and an instructor, both seeking the same goal of increasing accessibility to education and using clear, consistent, dependably functional channels for negotiating that access.

This is not always how it works. Students seeking accommodations are forced to reckon with the potential for stigma or bias that it creates to seek such a thing. Instructors are pushed to reconsider their classroom strategies, rethink their pedagogical default settings, and disrupt their own thinking about how they should be doing their jobs.

Accommodations may also, even when approached with the best of intentions by all parties, be not entirely adequate. Even a superlative notetaker cannot guess exactly which bits of a class discussion another person might choose to emphasize in their notes. An ASL interpreter can only interpret one person’s words at a time even when the discussion gets heated and many people are chiming in. In many ways trying to improve educational access for people with disabilities is as much an art as it is a set of policy decisions one can follow.

In my experience, making decisions about student disability accommodations in my classrooms has required five things, none of which have been part of my explicit training as an educator. Thus I list them here, in the hope that they will be helpful to my colleagues and to students with disabilities who need to know what they should be able to expect from their instructors.

Acknowledging a student-instructor relationship as separate and distinct from the patient-medical provider relationship, and respecting the difference. Students with documented disabilities have, by definition, an existence as patients: being a patient is how one acquires the diagnosis necessary for documenting the existence of a disability. But the educator is not the student’s medical care provider.

Instructors may be curious about the nature of the diagnosis that has occasioned the provision of a disability accommodation. It is human nature to wonder what someone else’s disability or difference is, what it is that puts them in this special category of persons entitled to accommodations. But curiosity doesn’t equate to a right to know what diagnosis a student has been given, or what therapies have been prescribed.

In fact, as an educator, you are entitled to none of that information and, should a student volunteer some, you are entitled to precisely zero opinions about it. This includes second-guessing whether a particular diagnosis “deserves” or “requires” a particular accommodation that has been allotted to the student: if someone who is the student’s medical provider has determined that the student needs that accommodation, our opinions as educators are irrelevant.

If a student does volunteer a diagnosis or other medical information, respect that you have been taken into confidence about what may be a deeply personal and vulnerable matter, and respect their privacy. If they don’t volunteer, don’t ask.

On a closely related note, don’t out your students. Sharing a student’s status as having a documented disability is a violation of privacy, just as a physician sharing your medical records would be. The individual — and not their doctor or their instructor — should always be allowed to choose whether and how they disclose their disability status or any other health status.

Maintaining clarity about the instructor’s role in determining appropriate accommodations. This is a subset of the above, part of acknowledging that your relationship with a student is unrelated to a student’s relationship to their healthcare provider(s). In many institutions, student requests for educational accommodations are channeled through an office for disability accommodations for precisely this reason. The instructor’s job is not to assess which disabilities deserve accommodation or which accommodations are appropriate for a specific disability. There is no reason to blur the line between the person whose job it is to educate (the instructor) and the people whose job it is to indicate what will make it easier for the student to receive education (the student, and their physician(s) or therapist(s)). The instructor’s job is to figure out how best to manage student requests for accommodation in order to facilitate the students’ access to education and ability to learn.

Maintaining clarity about what the bottom line is for your classes: what do you expect your students to get out of your class? Like most instructors, I often design classes with the assumption that all my students will be equally capable of performing all of the assignments, equally able to physically be present for all the classes, and equally able to negotiate the physical and emotional demands of both classroom presence and assignments. But these assumptions don’t always leave enough room for some of my students. This is unfair to my students with disabilities. It’s also unfair to me and the rest of my students, all of whom by rights ought to have the benefit of sharing a classroom with a wide diversity of students with a diverse set of backgrounds and lived experiences.

Thinking carefully about what the learning goals are for the class helps me to gauge how best to respond to disability accommodations. It might, for instance, help me identify which assigned readings are core readings and which might be less crucial, and thus possibly optional for students with reading-related disabilities.

Evaluating what I expect students to get from doing individual assignments might allow me to decide that an exercise in interpreting a visual image such as a photograph or archival document is not crucial to a primary class goal and thus a student with visual disabilities might be exempted from doing it. Or perhaps I will determine that this exercise is crucial to what I want my students to learn, and I need to figure out if there might be a good way to adapt the assignment to the abilities of the student. This is a great time to talk to the disability accommodations office. They can help with brainstorming and strategy as well as resources.

One of the things I consider a crucial bottom line for the functioning of my classes is continuity and predictability. Therefore I typically indicate to students both orally and in the syllabus that there is a cutoff date (usually 3 weeks into the semester) past which I will deal with new accommodations requests only on an emergency basis. Everyone in my classroom, including me, deserves to be able to lean on dependable class routines wherever possible as we dig into the bulk of our semester’s work together.

Being willing to be creative and work with the student in choosing the best accommodations for that student. Meeting with a student to discuss accommodations is an important part of the process of creating access. Such a meeting is the place where an instructor might be able to ask a student for direction, offer some of their own thoughts about accommodations options, or both. Discussing available options, and being flexible and willing to help the student gain access to the tools they believe will be most helpful to them, is always appropriate. So is talking through planned accommodation(s) so that both of you have a good idea of what they will look like in practice.

Let’s say a student is requesting accommodation because their disability means they cannot always physically attend class. Let’s further stipulate that the instructor has designed a class in which reading and discussion are the backbones of the class: the instructor gauges students’ completion of the reading assignments by their participation in class discussion, and also grades them on the quality of their contributions to the discussions. Depending on the student’s sense of themselves and their needs, the two of you may conclude that a student who could not be in the classroom consistently could be accommodated with, for instance, occasional office hours or even phone meetings to check in and make sure the student is reading and understanding those assignments. But perhaps the student would also want to know if it is possible to have audio recordings of classes made and sent to the student, enabling them to hear the discussion when they can’t be in the classroom. As an instructor, this is a request that you can take to the disability services office on your campus, and find out what resources exist to make this happen. Working creatively with your institution as well as your student may be necessary to create the best outcomes.

Quality control, or checking in about access. Since college and university students are adults, and we expect them to be able to represent themselves and speak up when things are not going as they should be going, it’s easy to presume that everything is fine with classroom accessibility unless a student brings a problem to us. In my experience, many students with disabilities are aware that they have already asked to be treated differently, and are afraid of becoming burdensome if they bring up problems with access or accommodations.

The fact remains, however, that an accommodation is only worth the name if it actually provides accommodation. For instance, a common example of an “accommodation” that isn’t happens when an instructor, acting in good faith, provides a set of PDFs of reading material for a student without realizing that image-only PDFs cannot be read by screen readers. Checking in with the student is a quick, easy way to make sure that the accommodations that are in place are actually doing what they are supposed to do. (Click and scroll down to learn to make PDFs that can be read by screen readers.)

For me, this is one of the places where I find it consonant with the notion of “accommodation” to do a little off-label educating via checking in about access. By checking in with a student who uses disability accommodations, I can help teach them that educators have a vested interest in students having functional accommodations because it means they are better able to do their job (learning) and I am better able to do mine (teaching).

My thanks to Hannah Abrahamson, Anna Hull, Rachel Kolb, and several others who chose to remain anonymous for their input on an earlier draft of this post.

October 8, 2016

On the Implied Priorities of ‘Rape Kits’

Yesterday, President Obama signed the Sexual Assault Survivors’ Rights Act into law.

The Act focuses on so-called “rape kits,” an unfortunate monicker for something that is intended to help collect and preserve physical evidence of rape for use in prosecuting rapists. (No rapist needs a kit. I advise you not to do an image search on “rape kit” unless you want to find out what kinds of “rape kits” some misogynist violent scary would-be rapists appear to find hilariously funny.)

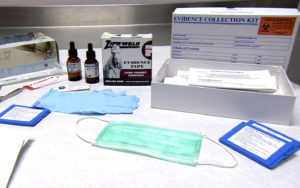

A representative sexual assault evidence collection kit.

A representative sexual assault evidence collection kit.There have been multiple issues with these evidence collection kits in the past, including jurisdictions refusing to have the medical examinations/evidence collections performed if a victim is not yet sure whether they wish to file a police report, jurisdictions charging victims fees in order to have those examinations/evidence collections performed, and hundreds of thousands of rape kits going untested and/or being discarded, possibly without ever notifying the victim.

The Act states that survivors of rape cannot be charged a fee for an evidence-gathering examination, or prevented from obtaining one. Once an evidence kit has been completed, the kits must be held in storage for the length of the term of limitations on the crime in question, at the expense of the state. Survivors of rape will have the option to request notification before the evidence kit is destroyed, the right to request that they be further preserved, and the right to be notified of any results of testing on the evidence collected.

It is a step in the right direction. And it is a step that has, like “rape kits” themselves, myriad problems.

Most rapes go unreported, for a variety of reasons including fears of being maltreated by police, reprisals from loved ones, being blamed for their own assaults, or simply not being taken seriously or believed. Living as we all do in a culture in which rape is both normalized and routinely silenced, survivors of rape may blame themselves, or otherwise find ways to rationalize the attack as being somehow their fault, and do not attempt to report. Additionally, many victims of rape experience an understandable reluctance to be intimately physically examined by a total stranger immediately after being raped. Or they may erroneously believe that if they have waited until the next day, for instance, or changed their clothes or taken a shower — two utterly normal things that also help to give a victim some psychological distance from an assault — that no physical evidence can be gathered and they may as well not bother.

But there is a larger and deeper issue with “rape kits.” Making the collection of physical bodily evidence central to prosecuting rape, a thing that the Act promotes, raises some questions about whose evidence we are willing to trust in cases of rape and sexual assault. It is not uncommon for survivors’ verbal testimony not to be taken terribly seriously, or to be viewed as merely part of a “he said / she said” that affords a problematic equality of moral authority to both rapists and their victims.

This is not to diminish the potential importance of physical evidence. Physical evidence can provide insight into the extent of physical injury, and it can enable positive identification with biological markers like DNA in ways that verbal testimony simply cannot. But prioritizing the use of physical evidence or considering it “superior” to or “more objective” than verbal evidence presents some logical and some ethical problems.

While we should — and I definitely do — applaud and thank President Obama, bill sponsor Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH), and Amanda Nguyen of Rise, whose experiences and activism as a survivor of rape led her to propose it, we might also want to ask whether “rape kits” mean that bodies are allowed to give testimony in a way that people are not.

What does it mean if we believe in the physical evidence collected from a sexual assault victim’s body but we do not believe the victim? It matters that we are prepared to believe in the reality and consequence of the injuries and substances that a rapist (usually but not always male) leaves on and in the body of a rape victim (usually but not always female) in a way that we are not prepared to believe in the reality and consequence of what a rape victim actually tells us.

What does it tell us that we have a legal and cultural preference for forensic evidence collected by a doctor or nurse when that evidence is essentially mute and momentary? Forensic evidence cannot tell us about pain, fear, panic, or humiliation. Nor do “rape kits” help us understand or even know about common sequelae of sexual assault like PTSD, sexually transmitted infection, or impregnation.

What does it tell us that we prefer evidence of a particular kind of rape? Kits are created to collect evidence of physical injury, samples of hair, blood, semen, and other bodily substances. Not all rapes leave this kind of evidence behind. The fact that we have a preference, now enshrined in law, for a form of sexual assault evidence that looks for these things as proof that rape occurred at all does two things. First, it establishes by implication that only rapes that provide this kind of evidence are really rapes. Second, the nature of the evidence that is preferred and prioritized serves to establish rape as an offense that exists only in the transient moment of its commission, when bruises (if any) are still fresh and the bodily fluids (if any) still detectable. Is this reasonable? Is it ethical? Is it even logical?

Let us hope that the Sexual Assault Survivors’ Rights Act will be expanded in future. Sexual assault survivors certainly should have the right to have physical evidence collected and handled with all due care and urgency, stored appropriately, and utilized correctly and well on behalf of the survivors. They — and really I should say “we” here — also deserve much, much more.

October 7, 2016

You Say “Abortion,” I Say Shenanigans

critical drug shortages in emergency rooms

the fact that many people *prefer* to use the ER as their primary medical care because the care access is so much better even post-ACA

and, oh yeah, the fact that the United States has the worst infant mortality rates in the developed world

…well, let’s just say I assume that they don’t actually care about medicine, they don’t care about ethics, and they don’t care about human lives or human suffering. What they care about, transparently, is forcing women to conform to a certain model of sexuality and procreation.

Because if you don’t care whether doctors are able to save lives or alleviate excruciating pain in an emergency room, and you don’t care whether people are forced into the emergency room in order to get access to reasonable healthcare, and you don’t care how many babies die before their first birthday… I’m calling shenanigans on your theatrics about the sanctity of human life.

Abortion is healthcare. Healthcare should be a human right, not a privilege. All healthcare should be accessible, affordable, and performed with care, compassion, and expertise. Now there’s a political subject I’d like to hear a meaningful discussion about during an election-season debate.

January 12, 2015

Reverse Engineering the Syllabus

Note: I’m reviving this blog as a catch-all for thoughts about graduate school and higher education/academia more generally. Updates will, I’m sure, be sporadic. — HB

A new semester is ramping up for me and as it does, I’ve been thinking about syllabi. Most students look at a course syllabus first and foremost as a to-do list, a roster of things that must be done and when they’re due. This is a perfectly reasonable and practical thing to do.

As it turns out, however, syllabi are like most texts in that they repay closer reading and more attention. In my experience, knowing how to read a syllabus closely and thoughtfully will help you understand the material better, do better on assignments, and become a far better participant in classroom discussions. A syllabus can tell you a great deal about your professor’s pedagogical leanings, about what they are trying to do with the course, and the ways you’re most likely to be successful in approaching the material.

The first thing I like to do with a new syllabus — after giving it a once-over and putting the relevant due dates into my calendar — is to look for clues as to how the professor is thinking about the class, both in terms of the subject and in terms of what the class meetings and discussions might be like.

For instance, how many texts are assigned? A syllabus with very few texts is likely to point toward a class in which each text will be dealt with in minute detail, while more texts means less class time per text. This is useful in helping you figure out how to prepare and how much material you should actually have in your hip pocket when you get to class, ready to bring it to the table. Bearing in mind that professors may choose to concentrate on one text only out of several that were assigned, there can be a big difference between a three-hour seminar with one text assigned per seminar and a seminar of similar length with four or five texts per class meeting. (You’ll get a feel as you go of whether your professor is the sort to concentrate on one text out of several or not, and can adjust accordingly)

Are the texts clustered in thematic groups? The syllabus may not indicate that they are, but they could be anyway. Figuring this out may require a quick library database search, and a light skim of a review or two of each of the assigned books.

The same skimming of reviews can also tell you whether the professor seems to be concentrating on a single approach to the topic or multiple ones. If there are multiple approaches in play, see if the order in which they come on the syllabus suggests that a particular underlying question or argument is implied. It is fairly common, for instance, for professors to assign books that “talk back” to other books assigned earlier in the semester, to give students a sense of what the larger academic conversation on a subject is like. Or they might assign a range of books that apply numerous different methodologies to a single general topic. If so, you can be sure that those things will be important to your in-class discussions, and you’ll want to be prepared to talk about them.

Next I like to look at the written assignments, presentations, and other things that I as a student will be asked to produce for the class. How are they spaced across the semester? Do you have a professor who has given you enough chances to produce that you’ll get written feedback and grades across the semester, thus letting you know how you’re doing along the way? Or do you have a professor who doesn’t expect a single page from you until the final paper is due, putting all your eggs into that one basket for you whether you like it or not? These things will help you strategize in terms of your schedule and how you spread out your work time across the semester, as well as about things like going to office hours to ask for some verbal feedback if you aren’t likely to be getting it from assignments.

Similarly, I pay attention to whether the assignments are all of the same type or whether they vary in nature. In graduate school, a course whose written assignments consist of five book reviews is not necessarily a poorly taught course with boring repetitive assignments. Your instructor may well be thinking about it as a course that is partly about teaching you to write academic book reviews. Even if they aren’t explicitly thinking this, you can be. Writing five book reviews will be more palatable if you have the perspective on the syllabus to look at the course as having a dual pedagogy — getting you to engage the topic, but also contributing to your professionalization by giving you practice at a common professorial form of writing that is useful for adding some meat to your CV.

By contrast, a course with multiple written assignments that are all of different types can teach you to engage a subject from multiple scholarly perspectives and in more than one academic performance style. If there are written assignments you’re not familiar with completing, reviewing the syllabus is a good time to mark them so you can leave yourself a little extra time to ask questions, seek out research help or hit the writing center, and otherwise help yourself learn how to do that particular type of assignment.

Finally, I reread the boilerplate and make sure I know how grades are calculated. If the syllabus does not make it crystal clear, at least I know to ask questions. Cynically but realistically, you at least need to know what the cost of doing business is when the inevitable happens and there is a class for which you have the choice of getting some sleep or trying to do some minimal class prep.

Basically, this is a process of reverse-engineering the syllabus. Your professor will have taken the time to put the syllabus together, and at least in theory will have reasons for making the decisions they made in terms of choosing texts, writing up assignments, distributing the workload, and so on. Part of the learner’s job, as I see it, is to figure out what the professor’s reasons are, and in so doing, to understand from the outset a little more about exactly what it is that you should be able to take away from the class.

As a bonus, you can learn a fair bit about putting together a syllabus by dissecting those written by your own professors… and never forget, even a bad example is a good example of a mistake you don’t want to make. It’s always nice to learn those things at someone else’s expense rather than your own.

September 1, 2013

I’m just going outside and may be some time…

I’ve become less and less of a blogger as time has gone on, which I think is probably self-evident.

I’ve also just gone back to school to get a history Ph.D., so the time I have in which to even think “you know, I should go resuscitate that poor moribund blog of mine” has just gone from “infrequent” to “nonexistent.”

So this is me, officially putting this blog on indefinite hiatus, lest you think I had gone all Antarctic explorer on you. (Google “Lawrence Scott” if you like.)

You can still find me writing at The Rumpus and various other places.

I’m on Facebook!

Less frequently you can find me Twittering.

I’m leaving the archives right where they are, for better or worse.

If you need me, email. Contact info’s on my contact info page.

Zey gesundt. See you in the funny papers.

May 30, 2013

It’s like science, only tastier!

As y’all know, I am in the final days of crowdfunding a very exciting 13-month serial cookbook/foodwriting project called A Girl’s Gotta Eat.

For more info on AGGE, or to support the project (please feel free!) please click here.

My funding period ends on June 1. Between June 2 and June 6, I will be accepting applications for recipe testers.

I am looking for 5 people who:

can each commit to testing at least 2 recipes from each issue

can commit to testing the recipes and giving me their notes on a relatively short turnaround (usually within 7-10 days)

can provide detailed feedback about their experience with a recipe, including any failures / necessary tweaks

are willing to work with me on retests if necessary, potentially on very short deadlines

Testers can live anywhere in the world, as the publishing end of this is all done electronically.

Testers are responsible for all expenses associated with recipe testing.

Testers can be people who have already supported the project, or those who for whatever reason haven’t had the ability to support the project but would like to support it by volunteering.

How To Apply:

Between June 2 and June 6 ONLY

send email to hanne dot blank at gmail dot com

with the subject line “recipe tester reporting for duty“

tell me where you live

tell me if you have food restrictions or allergies

tell me about a recipe you tried that did not work right, and what you did about it

tell me why you want to test recipes for A Girl’s Gotta Eat

Again, please send your application BETWEEN JUNE 2 and JUNE 6 2013. Applications received before or after these dates will be discarded.

Successful applicants will be informed via email on or around June 10.

Looking forward to hearing from you!

May 10, 2013

Big Fat Voices in Cambridge

Dear New England,

This will be my last appearance in Massachusetts for Some Time To Come. If you wanna get in on this action, here’s where you need to be and when.

Behold! Three fat superheroines in glorious eyeglasses swoop into Cambridge for one night to read from their own works. Let the skyline be illuminated by the brilliance of their cultural critique and honest words. Listen to their powerful fiction, memoir, and poetry pieces boom out. And be swept away on a cresting wave of fat activism, fat acceptance, and fat community.

Friday, May 24th

7:00pm-9:30pm

$10-$20* sliding scale at the door

Athenaeum Building

215 First St., Kendall Square, Cambridge, MA

Venue is accessible for people riding wheels & such.

Books for sale and to be signed by the authors.

Cash only!

Hanne Blank is a fat queer femme writer, historian, and speaker who spends her time at the crossroads of bodies, self, and culture. Joyfully spanning the town/gown divide as well as the mind/body split, her books include the cult classic sex and body-acceptance books The Unapologetic Fat Girl’s Guide to Exercise and Other Incendiary Acts (Ten Speed Press, 2012), Big Big Love: A Sex and Relationships Guide for People of Size (and Those Who Love Them) (Celestial Arts, 2011), the histories Straight: The Surprisingly Short History of Heterosexuality (Beacon Press, 2012) and Virgin: The Untouched History (Bloomsbury, 2007), and numerous others. A new body-acceptance book, The Good Body Manifesto: A Guide To Radical Acceptance for Bodies and Those Who Have Them, is slated for 2014. Hanne lives in north-central Massachusetts and in Atlanta, Georgia.

Lesley Kinzel has been writing and activisting about body politics for most of her life, having helped lead the Fatshionista Livejournal community for several years and then moving on to her own blog, Two Whole Cakes. Lesley has also written a book, a manifesto-memoir also called Two Whole Cakes, published by The Feminist Press. It has cakes on the cover. These days you can find her writing about fattery and other subjects as Senior Editor on xoJane.com. Lesley currently lives in the Boston area with her husband and cat, where she is very fond of tea, and cardigans.

Susan Stinson is the award-winning author of the novels Fat Girl Dances With Rocks, Martha Moody and Venus of Chalk, as well as Belly Songs, a collection of poetry and lyric essays. In 2011, she was awarded the Outstanding Mid-Career Novelist Prize from the Lambda Literary Foundation. Writer in Residence at Forbes Library in Northampton, Massachusetts, she is also an editor and writing coach. Alice Sebold had said, “Susan Stinson is a novelist who translates a mundane world into the most poetic of possibilities. “ Spider in a Tree, her novel about eighteenth century Northampton, is forthcoming in October 2013 from Small Beer Press. She can be found online at www.susanstinson.net.

*10 $7 scholarship seats are available to those with limited ability to pay; please email theb...@gmail.com.

April 29, 2013

Who You’re Sitting Next To At This Dinner Party: Heidi Knabe

This year, I’ve decided to run a series of short interviews with some of the marvelous people I know or have worked with (or both), because I know far too many fascinating people not to share. Each person answers the same questions. All of them give thought-provoking, interesting, wonderful answers.

These are the people you’re sitting next to at this dinner party. Enjoy.

Heidi Knabe has been blogging at www.attackofthesugarmonster.com about life, fatness, and living with mental illness for over 10 years. In 2007 her guest post on Shapely Prose went viral and things haven’t been the same sense. In 2013 she appeared on the Fucking While Feminist podcast, talking about body acceptance, being naked on the internet, and why you should do the scariest things you can think of.

This is what gorgeous, relentless honesty looks like.

This is what gorgeous, relentless honesty looks like.

Please describe yourself in 25 words or less.

I’m an ugly, fat, bitch! Other labels include feminist, bleeding heart liberal, loyal, blindly optimistic, and compassionate, with a bit of kink thrown in for flavor.

What are three things about you that most people either don’t know or wouldn’t expect?

I ghost wrote one of the first pieces on Huffington Post.

I used to have a collection off eight Kenny Rogers paintings. I plan to, one day, get an epic tattoo of Kenny, with the words, “You gotta know when to hold ‘em” in fancy script.

I really want to learn how to: knit, play the violin, juggle, shoot a gun, breathe fire, and accept the love and help offered to me.

Of the things you’ve done in your life so far, what are you proudest of?

My blog. Hands down. As much hate and rage that’s been spewed at me – and believe me, it’s a lot – I can’t stop blogging. I won’t stop blogging. Because mixed into all that vitriol are people telling me they went on antidepressants because I talk so openly about my depression. They went sleeveless because of my blog. They discovered fat acceptance and Health at Every Size because of my blog. One email was from a man who admitted to having been disgusted by fat people, to seeing them as subhuman. But, because of my blog, he realized that fat people are real people and that they deserve respect. But the one that just… ripped my heart out was someone telling me that they were planning to kill themselves but stayed up all night reading all the posts in my “mental health” tag instead. They thanked me for preventing them from doing something they couldn’t undo.

Honestly, my blog started as as my journal and I still see it that way. Even though I know, logically, that people read me, in my mind my audience is a half dozen people. It’s just my diary. And the fact that writing about my life and being honest about EVERYthing has impacted people’s lives in such huge, real, positive way brings me to tears. And I’ll take every horrible, hateful message the internet has to offer if it means one person feels better about who they are because of something I wrote. Because, to me, it’s worth it.

What’s an as yet nonexistent thing about which you’ve thought “why hasn’t someone created that yet?”

I’d kill for a magical robot who gives deep tissue massage.

If you could get everyone who reads this to do one thing, just once, what would you get them to do?

Do something you’ve been afraid to do. Fuck with the lights on, cut off all your hair, ask your crush to go for coffee. And, once you have done that thing, regardless of whether or not it went the way you’d hoped, NEVER forget that you stepped outside of your comfort zone and the world didn’t come to end because of it. You did something terrifying and you SURVIVED. And know that I am so fucking proud of you.

* * * * *

Hey! If you like reading, and writing, and honesty, and beauty, and food… why not subscribe to my new project, A Girl’s Gotta Eat?

A Girl’s Gotta Eat is a cookbook for people who like to read, and food writing for people who like to eat, in the form of a 13-month serial… check it out! It’s over 1/3 funded, and when we get to the halfway mark, there’ll be a special bonus for every single backer!

Hanne Blank's Blog

- Hanne Blank's profile

- 121 followers