John Quiggin's Blog

October 12, 2025

The natural party of government

Labor looks like becoming the “natural party of government”, but in doing so, it is abandoning its traditional role as the party of initiative. In this post, I’ll discuss the first of these points

Labor as the natural party of government

Prediction in politics is always tricky, but it seems fair to say that Anthony Albanese is well on the way to realising his stated goal of making Labor the “natural party of government” in Australia. Assuming a continuation of the current party system, that leaves the LNP as a party of protest, the B-team which is elected only when Labor has been in too long, or stumbles really badly.

Indeed, this has arguably been the case for some time at the state level. The LNP has been out of office almost continuously since 2000 in Queensland, South Australia,Victoria, and the ACT. It took the truly spectacular corruption and incompetence of NSW Labor to give the LNP three terms there. In WA, they managed two terms on the back of Alan Carpenter’s bizarre decision to readmit allies of the notorious Brian Burke to the ministry.

Federally, however, the Liberals have been competitive until recently. Although it never seemed likely that they could win a majority at the 2025 election, a minority LNP government seemed possible until quite near election day. The disastrous outcome reflected two main factors. First, having campaigned against Albanese’s Voice referendum on the content-free but almost invariably successful slogan “If you don’t know, vote NO’, the LNP convinced themselves they had tapped the support of a silent majority of anti-woke Australians. Then, the horrific advent of the Trump regime made support for Trumpist policies untenable, a fact that was only realised too late.

But the result has only reinforced the shift that was already underway from rightwing neoliberalism to Trumpism. Neoliberalism in the Liberal Party was represented almost entirely by representatives of and candidates for metropolitan seats, nearly all of which have been lost to Labor and independent candidates. The result is a party whose members typical voters increasingly resemble those of One Nation – aggrieved low education voters from peri-urban and regional Australia. Having gained control of the party, it seems unlikely that they will hand it back to the urban upper-middle class that previously dominated it. That leaves the Liberals and Nationals fighting with One Nation and other rightwing parties for perhaps 40 per cent of the electorate.

Labor hasn’t gained the support of the remaining 60 per cent, but it doesn’t need to. The distance between the Greens (and, to a lesser extent, progressive independents) on one side and LNP/ONP on the other is such that Labor will usually get second preferences from both. So Labor will win unless its candidate finishes third in the first preference count or else so far behind that that the inevitable leakage of preferences is enough to produce a majority for the initial leader (or of course, where a non-Labor candidate wins a first-round majority, but that’s rare these days.

In the context of a single-member electorate, the usual outcome is the best reflection of the preferences of voters. If a Labor candidate beats, the LNP on preferences, that’s because a majority of voters preferred Labor to the LNP. And since the LNP candidate’s preferences would also have flowed to Labor, a different majority would have preferred Labor to Greens in a two-candidate race. In the jargon of voting theory, Labor is the Condorcet winner.

The difficulties arise when this outcome is repeated over many electorates. The effect of a single-member system is to magnify majorities, producing parliaments that are quite unrepresentative of the voters.

As we have seen, Labor can win a comfortable House of Representatives majority with 35 per cent first preference support, and could probably form a government even with a vote as low as 30 per cent, and the support of a few independents.

Fortunately for Australian democracy, the Senate is elected on a proportional representation basis, meaning that Labor can’t just push legislation through regardless of the merits. A shift to PR in the House of Representatives would be highly desirable, but it won’t happened until Labor loses its majority and (given that independents depend on localised support) probably not even then.

September 27, 2025

Paper reactors and paper tigers

The culmination of Donald Trump’s state visit to the UK was a press conference at which both American and British leaders waved pieces of paper, containing an agreement that US firms would invest billions of dollars in Britain.

The symbolism was appropriate, since a central element of the proposed investment bonanza was the construction of large numbers of nuclear reactors, of a kind which can appropriately be described as “paper reactors”.

The term was coined by US Admiral Hyman Rickover, who directed the original development of nuclear powered submarines.

Hyman described their characteristics as follows:

1. It is simple.

2. It is small.

3. It is cheap.

4. It is light.

5. It can be built very quickly.

6. It is very flexible in purpose (“omnibus reactor”)

7. Very little development is required. It will use mostly “off-the-shelf” components.

8. The reactor is in the study phase. It is not being built now.

But these characteristics were needed by Starmer and Trump, whose goal was precisely to have a piece of paper to wave at their meeting.

The actual experience of nuclear power in the US and UK has been an extreme illustration of the difficulties Rickover described with “practical” reactors. These are plants distinguished by the following characteristics:

1. It is being built now.

2. It is behind schedule

3. It requires an immense amount of development on apparently trivial items. Corrosion, in particular, is a problem.

4. It is very expensive.

5. It takes a long time to build because of the engineering development problems.

6. It is large.

7. It is heavy.

8. It is complicated.

The most recent examples of nuclear plants in the US and UK are the Vogtle plant in the US (completed in 2024, seven years behind schedule and way over budget) and the Hinkley C in the UK (still under construction, years after consumers were promised that that they would be using its power to roast their Christmas turkeys in 2017). Before that, the VC Summer project in North Carolina was abandoned, writing off billions of dollars in wasted investment.

The disastrous cost overruns and delays of the Hinkley C project have meant that practical reactor designs have lost their appeal. Future plans for large-scale nuclear in the UK are confined to the proposed Sizewell B project, two 1600 MW reactors that will require massive subsidies if anyone can be found to invest in them at all. In the US, despite bipartisan support for nuclear, no serious proposals for large-scale nuclear plants are currently active. Even suggestions to resume work on the half-finished VC Summer plant have gone nowhere.

Hope has therefore turned to Small Modular Reactors. Despite a proliferation of announcements and proposals, this term is poorly understood.

The first point to observe is that SMRs don’t actually exist. Strictly speaking, the description applies to designs like that of NuScale, a company that proposes to build small reactors with an output less than 100 MW (the modules) in a factory, and ship them to a site where they can be installed in whatever number desired. The hope is that the savings from factory construction and flexibility will offset the loss of size economies inherent in a smaller boiler (all power reactors, like thermal power stations, are essentially heat sources to boil water). Nuscale’s plans to build six such reactors in the US state of Utah were abandoned due to cost overruns, but the company is still pursuing deals in Europe.

Most of the designs being sold as SMRs are not like this at all. Rather, they are cut-down versions of existing reactor designs, typically reduced from 1000MW to 300 MW. They are modular only in the sense that all modern reactors (including traditional large reactors) seek to produce components off-site. It is these components, rather than the reactors, that are modular. For clarity, I’ll call these smallish semi-modular reactors (SSMRs). Because of the loss of size economies, SMRs are inevitably more expensive per MW of power than the large designs on which they are based.

Over the last couple of years, the UK Department of Energy has run a competition to select a design for funding. The short-list consisted of four SSMR designs, three from US firms, and one from Rolls-Royce offering a 470MW output. A couple of months before Trump’s visit, Rolls-Royce was announced as the winner. This leaves the US bidders out in the cold.

So, where will the big US investments in SMRs for the UK come from? There have been a “raft” of announcements promising that US firms will build SMRs on a variety of sites without any requirement for subsidy. The most ambitious is from Amazon-owned X-energy, which is suggesting up to a dozen “pebble bed” reactors. The “pebbles” are mixtures of graphite (which moderates the nuclear reaction) and TRISO particles (uranium-235 coated in silicon carbon), and the reactor is cooled by a gas such as nitrogen.

Pebble-bed reactor designs have a long and discouraging history dating back to the 1940s. The first demonstration reactor was built in Germany in the 1960s and ran for 21 years, but German engineering skills weren’t enough to produce a commercially viable design. South Africa started a project in 1994 and persevered until 2010, when the idea was abandoned..Some of the employees went on to join the fledgling X-energy, founded in 2009. As of 2025, the company is seeking regulatory approval for a couple of demonstrator projects in the US.

Meanwhile, China completed a 10MW prototype in 2003 and a 250MW demonstration reactor, called HTR-PM in 2021. Although HTR-PM100 is connected to the grid, it has been an operational failure with availability rates below 25%. A 600MW version has been announced, but construction has apparently not started.

When this development process started in the early 20th century, China’s solar power industry was non-existent. China now has more than 1000 Gigawatts of solar power installed. New installations are running at about 300 GW a year, with an equal volume being produced for export. In this context, the HTR-PM is a mere curiosity.

This contrast deepens the irony of the pieces of paper waved by Trump and Starmer. Like the supposed special relationship between the US and UK, the paper reactors that have supposedly been agreed on are a relic of the past. In the unlikely event that they are built, they will remain a sideshow in an electricity system dominated by wind, solar and battery storage.

Optus’s triple zero debacle is further proof of the failure of the neoliberal experiment

The Optus triple zero disaster was a classic failure of neoliberal reform. In place of the single emergency call system that worked in the period before privatisation and liberalisation, we now have multiple networks, which are supposed to connect their calls to Telstra. Optus lobbying earlier this year successfully delayed a proposal(introduced in response to an earlier outage in 2023) for real-time information sharing on such outages.

Instead, calls reporting the most recent failure were directed to offshore call centres, where the operators failed to “escalate” them properly. The days-long delays in working out the extent of the problem reflect a corporate culture where triple zero calls are seen as an inconvenient cost burden rather than a vital community service. It’s the same culture that has seen Optus fined heavily for misleading consumers.

But until the recent spate of failures, telecommunications was seen as one of the increasingly rare sectors where privatisation and competition had produced improved outcomes for consumers. During the era of neoliberalism, the cost of telecommunications has plummeted, while the range of services has expanded massively. Whereas an international phone call cost more than a dollar a minute when telecoms were deregulated in the 1990s, they now cost only a cent or two per minute even on those plans that don’t include unlimited calls. As a result, telecommunications is regularly cited as an area where neoliberal reform has been successful.

A closer look at the record tells a different story. Technological progress in telecommunications produced a steady reduction in prices throughout the 20th century, taking place around the world and regardless of the organisational structure. The shift from analog to digital telecommunications accelerated the process. Telecom Australia, the statutory authority that became Telstra, recorded total factor productivity growth rates as high as 10% per year, remaining profitable while steadily reducing prices.

Optus claimed live updates on triple-zero outages would impose ‘huge burden’ months before outage

Optus claimed live updates on triple-zero outages would impose ‘huge burden’ months before outageBut for the advocates of neoliberal microeconomic reform, this wasn’t enough. They hoped, or rather assumed, that competition would produce both better outcomes for consumers and a more efficient rollout of physical infrastructure. Optus was an artificial creation of the reform process. In return for acquiring the publicly owned satellite network Aussat, Optus was given a regulatory head-start of six years, during which it was the only competitor to Telstra.

The failures emerged early. Seeking to cement their positions before the advent of open competition, Telstra and Optus spent billions rolling out fibre-optic cable networks. But rather than seeking to maximise total coverage, the two networks were virtually parallel, a result that is a standard prediction of economic theory. The rollout stopped when the market was fully opened in 1997, leaving parts of urban Australia with two redundant fibre networks and the rest of the country with none.

The next failure came with the rollout of broadband. Under public ownership, this would have been a relatively straightforward matter. But the newly privatised Telstra played hardball, demanding a system that would cement its monopoly position in fixed-line infrastructure. The end result was the need to return to public ownership with the national broadband network, while paying Telstra handsomely for access to ducts and wires that the public had owned until a few years previously.

Meanwhile the hoped-for competition in mobile telephony has failed to emerge. The near-duopoly created in 1991, with Telstra as the dominant player and Optus playing second fiddle, has endured for more than 30 years. The 2020 decision to allow a merger between the remaining serious competitors, TPG and Vodafone, was an effective admission that no more than three firms could survive. Unsurprisingly, prices have increased significantly since then.

And in crucial respects, three will soon become two. Optus and TPG now share their regional networks, a recognition of the fact that telecommunications infrastructure is a natural monopoly, and that the idea of “facilities-based competition” is an absurdity. If we are to have competition, the best model is that of the NBN. That is, a single wholesale “common carrier”, which allows retailers using its network to compete for customers.

But as we’ve learned with privatised electricity distribution businesses, privately owned monopolies are always looking for ways to increase profits at the expense of consumers. Regulation has proved ineffective, a fact that is unsurprising given the massive imbalance of resources between regulators and the companies they oversee.

The likely outcome of the triple zero disaster will be the addition of some new patches in the regulatory quilt and the ritual defenestration of some senior executives. But what we actually need is a reassessment of the whole neoliberal experiment and an acceleration of the return to public ownership of infrastructure that is already under way.

September 21, 2025

Billion dollar boondoggle

The Tasmania Plannning Commission has recommended against the proposed Hobart AFL stadium, with a relentless demolition of the economic case put forward by the proponents and their consultant KPMG. You can read their report here , or my own earlier analysis below

A couple of observations on this.

First, this would be a huge opportunity for the Tasmanian Labor party to escape from its self-inflicted wounds and achieve a good policy outcome at the same time. A vote against the stadium would create huge problems for Liberal Premier Rockliff. Potentially, it would create a path to a Labor minority government. This would require willing to dump the absurd refusal of former leader Dean Winter (and the troglodytes in the party machine) to “do deals”. It ought to be obvious by now that, Labor will never again win a majority or find Green and independent willing to give them unconditional support.

Second, a point I’ve made before. If KPMG (or PwC Deloittes or Accenture) is willing to put their name to economically illiterate rubbish like the stadium business case, why should anyone believe them about anything?

My analysis from 2023The Albanese government’s announcement it will provide $240 million for a new stadium in Hobart has not had the favourable reception it might have hoped.

Those concerned with the proper operation of the federal system can point out that this kind of funding is the concern of state and local governments.

Twitter, CC BY

Twitter, CC BYConcerns about process are reinforced by the sorry history of “sports rorts”. Both Labor and Liberal federal governments have funded sports facilities to curry political favour.

To be fair, it is hard to see this project as targeted at a particular seat, but presumably the aim was to win support in Tasmania as a whole. Even compared with the dubious economics of sporting events such as the Formula 1 Grand Prix and the Olympic Games, stadium developments stand out as boondoggles.

Extensive research in the US is summarised by the conclusion that over the past 30 years, building sports stadiums has been a profitable undertaking for large sports teams, at the expense of the general public.

While there are some short-term benefits, the inescapable truth is the economic benefit of these projects for local communities is minimal. Indeed, they can be an obstacle to real development.

Making the business caseThe economic case for the Hobart Stadium is startlingly thin. The only clear-cut benefit attributable to the project is that the new Tasmanian AFL team will play its home games there, replacing the small number of AFL rounds played at Hobart’s existing stadium, Bellerive Oval.

In 2022, eight AFL men’s games were played in Tasmania – four at Bellerive, four at UTAS Stadium in Launceston. A local AFL team will play 11 home games.

Higginson/AAP

The state government’s business case estimates that 5,000 interstate visitors will attend seven matches a year. It seems safe to assume some will fly in and out on the same day, and that few will stay more than two nights.

If we allow an average of one night per visitor, that’s 35,000 bed nights, or an increase of about 0.3% in current visitor nights for Tasmania (about 11 million a year in 2022).

Against that must be offset the Tasmanians who will travel to Melbourne and elsewhere for away games.

What about housing?All of this is par for the course for projects of this kind. The big problem for both state and federal governments is that it comes at a time of a housing crisis.

The federal government’s press release contains some vague references to housing developments associated with the project. But this is little more than the sort of PR spin we’d expect from, for example, the proponents of a new coal mine.

The numbers here are quite startling. The centrepiece of federal Labor’s election platform was a $10 billion fund for housing, providing $500 million year to support social housing. (Labor’s bill is currently held up in the Senate, with the Coalition opposed, and the Greens demanding stronger action.)

If this $500 million were allocated proportionally by population, Tasmania would get about $10 million a year. The Commonwealth’s $240 million contribution to the stadium would cover this expenditure until nearly 2050. The total public outlay on the Hobart stadium (with $375 million from the Tasmanian government) would cover most of this century.

At a time of extreme fiscal stringency, such a massive outlay on a luxury project is very hard to justify.

What about job creation?No serious benefit-cost analysis of this project has been made. Instead, supporters have relied on announcing the number of jobs it will create – 4,200 jobs during construction and 950 jobs when operational.

Such numbers are questionable. To make them bigger, governments typically count on the “multiplier effect” of work created for suppliers of various kinds. This is a long-standing tradition taken to new heights by the Albanese government. The announcement of the AUKUS submarine project, for example, was all about the jobs it would create.

But wait a moment. At the same time as trumpeting the creation of jobs for construction workers, the government is seeking to solve Australia’s “skills shortage” arising from historically low unemployment.

Tasmania’s unemployment rate is 3.8%, marginally above the average for Australia, but lower than at any time since the economic crisis of the 1970s. This low rate represents a situation of full employment, where numbers of unemployed workers and job vacancies are roughly equal.

In such circumstances, creating a job means luring a worker away from another. If the new job is on a major construction project, that means one less worker available to build housing.

As I argue in my book, Economics in Two Lessons (Princeton University Press, 2019), the true costs of wasteful public expenditure are opportunity costs – the alternatives that are foregone.

Multiplier effects make opportunity costs even larger. The project diverts the workers employed directly, and takes all kinds of resources that could otherwise be used for socially useful purposes. This diversion of necessary resources is the truly pernicious aspect of publicly subsidising projects like the AFL stadium.

Tasmania, like the rest of Australia, does not need government action to create any more jobs, particularly in construction. It needs to ensure skilled workers are employed where they can be most valuable.

September 12, 2025

Is Deep Research deep? Is it research?

I’m working on a first draft of a book arguing against pro-natalism (more precisely, that we shouldn’t be concerned about below-replacement fertility). That entails digging into lots of literature with which I’m not very familiar and I’ve started using OpenAI’s Deep Research as a tool.

A typical interaction starts with me asking a question like “Did theorists of the demographic transition expect an eventual equilibrium with stable population”. Deep Research produces a fairly lengthy answer (mostly “Yes” in this case) and based on past interactions, produces references in a format suitable for my bibliographic software (Bookends for Mac, my longstanding favourite, uses .ris). To guard against hallucinations, I get DOI and ISBN codes and locate the references immediately. Then I check the abstracts (for journal articles) or reviews (for books) to confirm that the summary is reasonably accurate.

A few thoughts about this.

First, this is a big time-saver compared to doing a Google Scholar search, which may miss out on strands of the literature not covered by my search terms, as well as things like UN reports. It’s great, but it’s a continuation of decades of such time-saving innovations, going back to the invention of the photocopier (still new-ish and clunky when I started out). I couldn’t now imagine going to the library, searching the stacks for articles and taking hand-written notes, but that was pretty much how it was for me unless I was willing to line up for a low-quality photocopy at 5 cents a page.

Second, awareness of possible hallucinations is a Good Thing, since it enforces the discipline of actually checking the references. As long as you do that, you don’t have any problems. By contrast, I’ve often seen citations that are obviously lifted from a previous paper. Sometimes there’s a chain leading back to an original source that doesn’t support the claim being made (the famous “eight glasses of water a day” meme was like this).

Third, for the purposes of literature survey, I’m happy to read and quote from the abstract, without reading the entire paper. This is much frowned upon, but I can’t see why. If the authors are willing to state that their paper supports conclusion X based on argument Y, I’m happy to quote them on that – if it’s wrong that’s their problem. I’ll read the entire paper if I want to criticise it or use the methods myself, but not otherwise. (I remember a survey in which 40 per cent of academics admitted to doing this, to which my response was “60 per cent of academics are liars”).

Fourth, I’ve been unable to stop the program pretending (even to describe this I need to anthropomorphise) to be a person. If I say “stop using first-person pronouns in conversation”, it plays dumb and quickly reverts to chat mode.

Finally, is this just a massively souped-up search engine, or something that justifies the term AI? It passes the Turing test as I understand it – there are telltale clues, but nothing that would prove there wasn’t a person at the other end. But it’s still just doing summarisation. I don’t have an answer to this question, and don’t really need one.

September 3, 2025

My submission to the National Electricity Market Review

The purpose of this submission is to respond to the National Electricity Market Wholesale Market Settings Review Draft Report, released in August 2025. The purpose of this submission is to argue that the ad hoc interventions seen so far should be replaced by centralised long-term planning of investment in both generation and transmission.

The National Electricity Market (NEM) was designed to combine day-to-day matching of electricity supply and demand with the provision of market incentives for efficient investment. As the draft report concedes, the NEM has failed in the second of these tasks. The report’s analysis of this central issue (pp 38–39) consists of two paragraphs, which may be quoted in full, along with the relevant figure

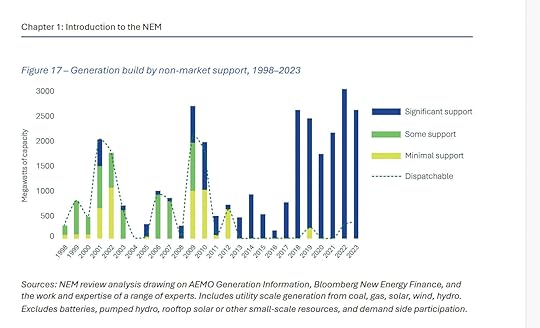

Investment in new generation in the NEM has been uneven – and in large part driven by specific policy measures. Investment in new generation in the NEM has fluctuated significantly over time, both in scale and by technology type. These shifts can be broadly grouped into three distinct periods since the market’s inception: a phase of growth driven primarily by rising peak demand (1998–2011); a period of oversupply and limited new investment outside of renewables mandated by the expanded Renewable Energy Target (2011–15); and the current phase of transition towards a low-emissions system (2015‑present) (see Figure 17).

Although the design of the NEM aimed to let market forces drive investment decisions, government policy support has been a significant driver of investment in new generation since its inception. The Panel notes that this has been a feature of most deregulated electricity markets, irrespective of the market design adopted. Almost all investment in new generation capacity in the NEM has received some form of government support, and there are very few examples of pure, market-only investments that were made entirely on the basis of expectations about future spot market revenues and forward derivatives markets. Emerging research suggests NEM spot prices and derivative markets on their own have not driven recent investment decisions in the NEM, in contrast to the strong role of policy support.

Given that it is investment decisions, rather than day to day market operations, which drive the energy transition, this outcome is entirely unsatisfactory.

The treatment of investment is further weakened by the exclusion of transmission from the scope of the report. However, the report correctly notes (p 36) “Centralised, long-term planning is essential to ensure transmission investment occurs in the right places, at the right scale and with sufficient lead time ”

The purpose of this submission is to argue that the ad hoc interventions seen so far should be replaced by centralised long-term planning of investment in both generation and transmission.

The dual roles of the National Electricity Market

The NEM was introduced in the 1990s, at a time when the primary sources of electrical generation were coal and gas. In the early years of the NEM, there was an oversupply of generation capacity as a result of expansion during the 1980s which was regarded, in retrospect, as excessive “gold plating”.

The NEM was designed to fulfil two purposes. First, on a day to day basis the NEM matched supply and demand in real time, using supply schedules submitted by generators. In this function it was reasonably successful until recently, although concerns were raised about strategic behaviour by suppliers with market power.

The second function was to promote efficient investment decisions. A sustained period of high prices would provide a signal to investors that construction of new power stations would be profitable. The design of the NEM was reasonably well suited to provide market signals for investment in “always-on” coal-fired power stations which would receive roughly the average daily price. In practice, however, new investment in the 1990s was limited except in Queensland, where the electricity industry remained publicly owned.

The design was much less satisfactory in relation to gas-fired power, which is best suited for “peaker” operation. This is because the NEM price is subject to a cap, originally referred to as the “value of lost load”, which was initially set at $5000/MWh. Although this might seem like a harmless restriction, the profitability of investments in peak capacity depends to a large extent on the relatively rare occasions when market demand exceeds supply even at such high prices.

The most important fault of the pricing system was that it made no allowance for carbon emissions, even though the introduction of the NEM coincided with the adoption of carbon emissions targets. The assumption, presumably, was that this issue would be addressed through some other policy, such as an economy-wide carbon price. In practice, however the only effective mechanism was the Renewable Energy Target (RET), the first of many adjustments bolted on to the simple design of the NEM.

Over time, as noted in the Review, the NEM has become less and less useful as a guide to investment. An electricity supply industry involving a mix of carbon-based and carbon-free suppliers raises a complex mix of issues including system stability, storage and access to transmission networks. The relationship between the prices set in the NEM and the incentives facing both utility scale investors and households regarding solar and wind investments are opaque to put it mildly.

An alternative approach

Rather than continuing to tweak the parameters of the NEM in an effort to get investment decisions right, it would be better to confine the NEM to the function of setting wholesale electricity prices so as to equate supply and demand.

In the place of the NEM, the optimal solution is a publicly controlled National Grid responsible for planning and managing investment in generation, transmission and large-scale storage.

Investment would generate returns through a mixture of revenue from electricity sales on the NEM and capacity payments designed to ensure system stability. The planning authority would approval proposals put forward by investors, and would also identify unmet needs and call for tenders to meet them.

Exclusive reliance on private investment has been a failure, leading to the re-establishment of public enterprises in Victoria and NSW and the expansion of public investment into renewable energy through CleanCo in Queensland. The public role should be expanded further while allowing scope for private investment at utility scale and also for households to meet their own needs through rooftop solar, storage and potentially, virtual power planets at the local level.

August 31, 2025

The crash of 2026: a fiction

Looking at the facts, there’s no reasonable conclusion except that US democracy is done for. But rather than face facts, I’m turning to fiction. So, here’s a story about the collapse of Trumpism, crony capitalism and the AI/crypto bubble. Fiction is a relatively unfamilar mode of writing for me, so critique (on style and structure rather than plausibility) is most welcome.

The crash of 2026The crash of 2026 began with a literal crash. A Tesla robotaxi operating on an open highway for the first time, inexplicably swerved into the path of oncoming traffic. Coming in the other direction was a Cybertruck whose driver, relying on self-driving capabilities, was busy checking his investments on the phone. His instant death spared him from the knowledge of his impending bankruptcy.

Tragically, a school bus was following, and its brakes failed (the school district later blamed budget cuts for inadequate maintenance) The driver did her best to steer around the wreckage but the bus overturned and burst into flames. By the time the smoke cleared, there were six deaths, including the busdriver and two children, as well as the occupants of both Teslas. More then 30 schoolchildren were taken to hospital. The images of death and disaster ran on TV and social media for weeks.

The reaction was swift. By the end of the day, Tesla’s robotaxis had been taken off the road throughout the US, and demands for retribution were everywhere. Several Tesla dealerships were torched and others closed down. The situation wasn’t helped by a bizarre tweet from Elon Musk, appearing to suggest that the bus driver was a “crisis actor”.

By the time Wall Street opened the next day, the financial analysts had done their sums. The legal liability for the disaster would run into billions, enough to wipe out most of Tesla’s cash reserves. And with the robotaxi business gone, there was nothing to conceal the truth of Tesla’s situation: a company with declining sales and margins trading at more than 100 times its current earnings. With the prospect of massive short sales at the opening bell, trading in Tesla shares was suspended.

This was bad news for Musk, who faced margin calls and the loss of his holdings in X and SpaceX, both secured by his ownership of 16 per cent of Tesla. But as usual in such cases, he got off easily. Musk turned up soon afterwards on a Caribbean island he had bought through a shell company years previously, along with the government of the nation that supposedly ruled it. No longer the richest man in the world, and theoretically bankrupt, he nonetheless enjoyed the comforts of a mansion and a super-yacht, each with its fleet of servants.

The situation was rather different for the owners of the other 84 per cent of Tesla, who collectively faced the loss of nearly a trillion dollars. Those with diversified holdings and no debt took the loss philosophically, as an offset against the massive profits of recent years. But others, who had borrowed to buy both Tesla and crypto assets like Bitcoin, faced disaster, especially when rumors spread that Tesla was about to dump its own massive Bitcoin holding.

The price of Bitcoin fell 25 per cent overnight. Longstanding HODLers were not concerned, reminding themselves that Bitcoin had fallen many times before, and had always rebounded. But now that crypto-currencies were embedded into the financial system, there were plenty of players with a shorter-term perspective. They started talking to economists, who almost universally agreed that crypto-currencies were inherently worthless. Traders who had gone all in on crypto suddenly saw the merits of profit taking. Regulators, who had been quiet since the passage of the GENIUS Act, started asking questions.

The real disaster came with the exposure of large-scale fraud at Tether, the most prominent of the stablecoins, which were supposed to trade at exactly $1 US. As the volume of investors seeking to quit crypto increased, it emerged that the supposedly ironclad asset backing of Tether had been undermined by a complex web of derivative transactions, allegedly the doing of a “rogue trader”.

Once Tether “broke the buck” the run was on in earnest. Wall Street banks found that that they had significant direct exposure to crypto and even more through their counterparties. They went into lockdown, calling in whatever debts they could.

The realisation that the multi-trillion dollar valuations of Tesla and Bitcoin had been spun out of thin air led to a harder look at Wall Street’s “Magnificent Seven” now reduced to six. Claims that AI was about to generate massive wealth if only more billions were invested looked silly. Investment in data centers stopped abruptly.

Nvidia was the first casualty. Once orders for chips from the hyperscalers dried up, its business was over. The advertising businesses of Google and Meta, and the Amazon retail business, went next. There would be no growth in sales of consumer goods for some time to come. Microsoft and Apple, with real businesses and products, fared better, but their values, based on hyperbolic price-earnings ratios, fell drastically. Crowds of ruined investors, milling in the streets, became violent, and were suppressed by heavily armed and masked thugs, presumed to be ICE, with several deaths. Increasingly violent protests and even more violent suppression followed.

At this point, a global financial crisis similar to that of 2008 was now inevitable. There were loud calls for an internationally co-ordinated response. But such co-ordination, already inadequate in 2008, was non-existent this time. Fed Chair Kevin Hassett, appointed by Trump after the removal of Jerome Powell, couldn’t even get his global counterparts to pick up the phone.

With less direct exposure to the crisis, other countries sought to protect themselves, imposing exchange controls, and preventing repatriation of funds to the US. Crypto trading was banned in many jurisdictions, and holders of crypto were required to report their positions to regulators.

Taken collectively, these disasters threatened to wipe out the entire wealth of the Trump family. Naturally, Trump struck back, announcing the discovery that trillions of dollars in US foreign debt was fraudulent, and would be expropriated. The remaining US public debt, following the plans previously announced by Stephen Miran (chair of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers) would be forcibly converted into 100 year bonds, at rates to be set by the US. The EU and Canada reacted by freezing US-owned assets. Trading on major stock exchanges around the world was suspended.

At this point, global capitalism seemed doomed, along with democracy. But somehow things turned around. With their donors facing ruin, dozens of Republican Representatives and Senators switched sides, throwing control of Congress to the Democrats, who immediately announced impeachment proceedings against Trump. Trump called on JD Vance to expel the traitors from the Senate, but, sensing the ground shifting, Vance temporised.

Trump attempted to declare martial law, but was forestalled by Vance and the Cabinet, who invoked the 25th Amendment to remove him. At Trump’s urging, a MAGA mob, including dozens of the masked gunmen now ubiquitous on American streets, marched on the Capitol, planning a repeat of 2020. But this time they were met by the army, with fixed bayonets and machine-gun emplacements. After a brief exchange of fire, the crowd fled, leaving dozens of dead and wounded behind.

The Vance Administration lasted only a few days. After seeking assurances that he would not face prosecution, Vance resigned in favor of Jerome Powell, who had been hastily appointed as Vice-President and was seen as the technocrat most likely to restore faith in the US,

The fallout was rapid. Facing impeachment and likely criminal charges of corruption, Supreme Court justices Thomas and Alito resigned, while Gorsuch and Kavanaugh decided that their appointments had been improper all along. The five remaining members of the court unanimously overturned the previous finding of Trump’s presidential immunity, and discovered that participation in the January 6 insurrection was in fact treasonous.

Facing this catastrophic defeat, MAGA fragmented. A minority of Trump’s supporters genuinely repented of the disaster they had brought on their country and became zealous defenders of democracy. Another group pointed to the feeble statements they had made criticising Trump and tried, with varying degrees of success, to maintain a role in public life. Some of the MAGA base gave up on politics altogether, suddenly discovering that Trump was just as corrupt as the Democrats he had railed against. Others remained loyal to their fallen leader. Republican state governments collapsed as the party fragmented.

Trump’s trial proceeded rapidly this time, and he was sentenced to spend his remaining days in prison, along with many of his cronies. There were some scattered insurrections which were rapidly put down, with their participants held in the various detention centres conveniently created by Trump.

Now, in early 2028, the world economy is gradually climbing out of the pit created by the crisis. The financial sector, a shadow of its former self, remains largely nationalised, and the disastrous losses in the crypto sector have yet to be resolved. But AI technologies, now in the public domain after the collapse of the hyperscalars. have started deliver significant (though not stratospheric) productivity benefits. Continued declines in the cost of solar power and battery storage have dispelled concerns about shortages of electricity, and have supported new investments in rewiring the economy in the US and other countries.

The reconstruction of the US political system will take much longer. President Powell, virtually assured of re-election, has proposed a constitutional convention that would replace the failed two-party system. The first step, already implemented in most states, has been a shift to instant runoff voting in Congressional elections, along with the scrapping of the primary system. But a shift to full-scale proportional representation is expected, with the former Republican party splintering, and socialists gaining significant support in cities and even some rural areas.

There is, as Adam Smith observed, a great deal of ruin in a nation. It will take decades for Americans to repair all the damage done by their experiment with fascism. But America has huge resources, both human and natural, and (at least in this fictional account) the traditions of democracy are finally reasserting themselves.

August 14, 2025

If something can’t go on forever, it will stop

The most striking observation in Dean Spears and Michael Geruso’s new book, After the Spike, is summed up by the cover illustration, which shows a world population rising rapidly to its current eight billion before declining to pre-modern levels and eventually to zero. As the authors observe, this is the inevitable implication of the hypothesis that fertility levels will remain below replacement level indefinitely into the future.

Before looking at the argument in more detail, it’s worth recalling Stein’s Law: “If something can’t go on forever, it will stop.” If the world’s population was in danger of falling below the level needed to sustain civilisation (science fiction writer Charlie Stross has estimated 100 million) there would presumably be some kind of drastic action. Fortunately, this is unlikely to happen for another 1000 years or so. If we manage to leave the planet in a habitable condition so far into the future, we can leave population policy to our distant descendants.

Before looking to the future, Spears and Geruso consider the past. The most striking observation here is that fertility (the number of children per woman) has been declining on average ever since reliable records began several hundred years ago. This isn’t news to those who have followed the question closely.

While fertility declined steadily over centuries, infant mortality dropped drastically from the eighteenth century onwards, first in the West and then globally. While fewer children were born, more survived to adulthood.

In exploring these trends, demographers focus on the net reproduction rate, or NRR: the number of surviving daughters per woman. (We all became familiar with this number in a different context in the early days of the Covid pandemic.) When the rate is greater than 1, the population grows.

For a hundred years or so from the late nineteenth century, the NRR rose steadily, reaching a peak of 2.1 in the early 1960s. That’s enough to double the population every generation (or about every thirty-five years). Had that rate continued, the world population would now be around twenty billion. It was in this context that biologist Paul Ehrlich sounded the alarm with his bestseller The Population Bomb, which predicted global disaster as soon as the 1970s.

Spears and Geruso are justifiably critical of Ehrlich’s alarmism. In reality, they observe, we have been highly successful in feeding a growing world population. Nor have predictions of the exhaustion of mineral resources put forward by Ehrlich and dramatised by the Club of Rome been borne out.

But emissions of carbon dioxide have grown drastically, driven in part by the population growth of the late twentieth century. Spears and Geruso mention the issue, but don’t discuss the relationship to population except in the context of our present climate crisis, where (as they say) population is of secondary importance.

The big point Spears and Geruso could have made, but didn’t, is that Ehrlich was sounding the alarm just as the NRR was reaching an inevitable peak. By the 1960s child mortality rates had already been reduced to a level at which further reductions couldn’t outpace the steady decline in fertility that is the central theme of After The Spike. The NRR was bound to fall even without the drastic measures suggested by Ehrlich (and, in more extreme form, by overtly racist writers like Garret Hardin, in his Lifeboat Ethics).

Because the population boom produced a mostly young population, declining fertility didn’t immediately translate into a smaller number of babies. Concern about the possibility of a declining population emerged when the number of births peaked in 2012. This concern built on a much longer, and entirely misguided, tradition of worrying about the supposed dangers of an “ageing population.” Sensibly, Spears and Geruso downplay such concerns, observing: “Restructuring public benefit programs and retirement ages is a fast solution to balancing the books in an ageing population. Raising birth rates is a slow alternative to any of these.”

And what of the far future? Projections show that likely declines in fertility will halve the world population each century after 2100, falling to one billion around 2400. Would that be too few to sustain a modern civilisation ?

We can answer this pretty easily from past experience. In the second half of twentieth century, the modern economy consisted of the member countries of the Organisation For Economic Co-operation and Development. Originally including the countries of Western Europe and North America but soon extended to include Australia and Japan, the OECD countries were responsible for the great majority of the global industrial economy, including manufacturing, modern services and technological innovation.

Except for some purchases of raw materials from the Global South, the OECD, taken as a whole, was self-sufficient in nearly everything required for a modern economy. So the population of the OECD in the second half of last century provides an upper bound to the number of humans needed to sustain such an economy. That number did not reach a billion until 1980.

Things have changed since then with the modernisation of much of Asia and the rise of China as the manufacturing’s “workshop of the world.” But the history is still relevant.

We can also look at the United Sates. Even today, trade accounts for only around 20 per cent of US economic output. Given a US population of 400 million, it is reasonable to suppose that the production of goods and services elsewhere for export to the US might account for another 100 million people. Most of the needs of these people could be met from within the US economy, but let’s suppose that they employ another 100 million in their own countries. That’s still only about 600 million people who, between them, produce all the food they need, the manufactures that characterised the industrial economy of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, most of the information technology the world relies on, and a steady flow of technological and scientific innovation.

At the lower end of the scale, Stross’s estimated minimum requirement, 100 million people, might need to be higher in a society even more technologically complex than our own. But since current demographic trends won’t produce that number for nearly a millennium, we probably needn’t worry (unless we want to colonise space, the context of Stross’s estimate)

In other words, there is no reason to think a billion people would be too few to sustain a technological economy. But what would a world of a billion people look like?

It’s foolish to try to say much about life hundreds of years from now. What could a contemporary of Shakespeare have to say about the London of today? But we do know that London and other cities existed long before Shakespeare and seem likely to continue far into the future (if we can get there). And many of the services cities have always provided will be needed as long as people are people. So, it might be worth imagining how a world population of one billion might be distributed across cities, towns and rural areas.

Australia, with 5 per cent of the world’s land mass and a current population of twenty-five million, provides a convenient illustration. A billion people would populate forty Australias with twice Australia’s current population density. But around half of Australia is desert or semi-arid (estimates range from 18 to 70 per cent, depending on the classification) and not many people live there. So, the population density of a billion-person world would look pretty much like that of urban and regional Australia today.

Opinions in Australia (as elsewhere in the world) are pretty sharply divided as to whether a bigger population would be a good thing, but it’s unusual for anyone to suggest we are spread too thinly. On the contrary, congestion, sprawl and the conflict between environmental preservation and housing are seen as the price to be paid for a larger population.

A billion-person world could not support mega-cities with the current populations of Tokyo and Delhi. But it could easily include a city the size of London, New York, Rio or Seoul (around ten million each) on every continent, and dozens the size of Sydney, Barcelona, Montreal, Nairobi, Santiago or Singapore (around five million each). Such a collection of cities would meet the needs of even the most avid lovers of urban life in its various forms. Meanwhile, there would be plenty of space for those who prefer the county.

With only a billion people we wouldn’t need all the space in the world. The project of rewilding half the world, now a utopian dream, could be fulfilled while leaving more than enough room for farming and forestry, as well as whatever rural arcadias followers of the simple life could imagine and implement.

The final part of After the Spike looks at policies that might significantly increase fertility and finds, unsurprisingly, that there aren’t any or, at least, none that will make much difference. The negative example of South Korea shows that a combination of patriarchal social attitudes and large-scale female labour force participation can produce very low fertility. And the peculiar circumstances of Israel push rates just above replacement. But otherwise, the NRR in developed countries lies between 0.75 and 0.9, regardless of family policies.

It makes sense to adopt policies that make it easier to raise a family. But most of those policies also make other options easier, with the result that family size doesn’t grow. Having written an entire book on opportunity cost, I am happy to see Spears and Geruso using this concept to make this point.

The central reason for declining birthrates is that, as potential parents, most of us have decided that putting a lot of effort into raising one or two children is better than spreading those efforts over three, four or more. What is true for individual families is true for the world as a whole. Until we have the resources to properly feed and educate all our children, we shouldn’t worry that we are having too few. •

Stop the free ride: all motorists should pay their way, whatever vehicle they drive

\A new road charge is looming for electric vehicle drivers, amid reports Treasurer Jim Chalmers is accelerating the policy as part of a broader tax-reform push.

At a forum in Sydney this week, state and federal Treasury officials are reportedly meeting with industry figures and others to progress design of the policy, ahead of next week’s economic reform summit.

Much discussion in favour of the charge assumes drivers of electric and hybrid vehicles don’t “pay their way”, because they are not subject to the fuel excise tax.

This view is based on an economic misconception: that fuel taxes are justified by the need to pay for the construction and maintenance of roads.

This is incorrect. In a properly functioning economic system, fuel taxes should be considered a charge on motorists for the harmful pollution their vehicles generate.

That leaves the problem of paying for roads. To that end, a road-user charge should be applied to all motorists – regardless of the vehicle they drive – so no-one gets a free ride.

Real science from real scientists.

Get free newsletter

A road-user charge should be applied to all motorists. NSW governmentWhat is the fuel excise?

A road-user charge should be applied to all motorists. NSW governmentWhat is the fuel excise?The fuel excise in Australia is currently about 51 cents a litre and is rolled into the cost of fuel at the bowser.

Some, such as the Australian Automobile Association claim revenue from the excisepays for roads. But it actually goes into the federal government’s general revenue.

The primary economic function of the fuel tax is that of a charge on motorists for the harmful pollution their vehicles generate.

Fuel excise is rolled into the cost of fuel at the bowser. FLAVIO BRANCALEONE/AAPPaying the cost of pollution

Fuel excise is rolled into the cost of fuel at the bowser. FLAVIO BRANCALEONE/AAPPaying the cost of pollutionVehicles with internal combustion engines – that is, those that run on petrol or diesel – create several types of pollution.

The first is carbon dioxide emissions, which contribute to human-caused climate change. Others include local air pollution from particulates and exhaust pollution as well as noise pollution.

In economic terms, these effects are known as “negative externalities”. They arise when one party makes another party worse off, but doesn’t pay the costs of doing so.

How big are the costs to society imposed by polluting vehicles? Estimates vary widely. But they are almost certainly as large as, or larger than, the revenue generated from fuel excise.

Let’s tease that out.

A litre of petrol weighs about 0.74 kg. But when burned, it generates 2.3 kg of CO₂. That’s because when the fuel is combusted, the carbon combines with heavier oxygen atoms.

Before the re-election of United States President Donald Trump, the nation’s Environmental Protection Agency estimated the social cost of carbon dioxideemissions at about US$190 (A$292) per metric tonne.

So in Australian terms, that means CO₂ emissions from burning petrol costs about 67 cents a litre, more than the current excise of 51 cents per litre.

Even using a more conservative estimate of US$80 a metric tonne, CO₂ emissions generate costs of around 28 cents a litre, more than half the fuel excise.

A spotlight on health impactsMotor vehicles are a major cause of air pollution. Air pollution is causally linked to six diseases:

coronary heart diseasechronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)stroketype 2 diabeteslung cancerlower respiratory infections.Estimates of the deaths associated with air pollution in Australia range from 3,200 to more than 4,200 a year.

Even the lower end of that range is far more than the roughly 1,200 lives lost in car crashes annually.

University of Melbourne analysis in 2023 landed at an even higher figure. It suggested vehicle emissions alone may be responsible for more than 11,000 premature deaths in adults in Australia a year.

Putting a dollar value on life and health is difficult – but necessary for good policy making.

The usual approach is to examine the “statistical” reduction in deaths for a given policy measure. For example, a policy measure that eliminates a hazard faced by 1,000 people, reducing death risk by 1 percentage point, would save ten statistical lives.

The Australian government ascribes a value of $5.7 million per (statistical) life lost or saved. So, hypothetically, a saving of 2,000 lives a year would yield a benefit of more than $10 billion.

This is more than half the revenue collected in fuel excise each year.

Putting a dollar value on life and health is difficult – but necessary for good policy making. DIEGO FEDELE/AAPThe best road forward

Putting a dollar value on life and health is difficult – but necessary for good policy making. DIEGO FEDELE/AAPThe best road forwardGiven the harms caused by traditional vehicles, society should welcome the decline in fuel excise revenue caused by the transition to EVs – in the same way we should welcome declining revenue from cigarette taxes.

If we assume fuel excise pays for pollution costs, then who is paying for roads?

The cost of roads goes far beyond construction and maintenance. The capital and land allocated to roads represents a huge investment, on which the public, as a whole, receives zero return.

Vehicle registration fees make only a modest contribution to road costs. That’s why all motorists should pay a road-user charge.

The payment should be based on a combination of vehicle mass and distance travelled. That’s because damage to roads is overwhelmingly caused by heavy vehicles.

Then comes the question of Australia’s emissions reduction. The switch to electric vehicles in Australia is going much too slowly. A road user charge targeting only electric and hybrid vehicles would be a grave mistake, slowing the uptake further.

August 9, 2025

Mitigating the productivity damage from Covid-19: the case for improved ventilation standards

I wrote this for the Cleaner Air Collective, who used it as an input to their submission to the Productivity Roundtable

Given the purpose of the exercise, the discussion is framed in terms of productivity though many of the issues are broader

Covid-19 is a serious economic problem for Australia, not only as a major cause of death, but because of serious impacts in productivity.

Although most Covid-19 deaths occur among people over 80, there were over 200 deaths from Covid among people aged 40-64. This is a mortality rate comparable to that of road trauma (377 deaths in this age group in 2022) As of 2023, excess mortality remained high at 5 per cent

With the effective abandonment of most forms of reporting, it is hard to assess the prevalence and impact of Covid-related morbidity. However, there is substantial global evidence of increased worker absenteeism associated with both acute Covid-cases and post-Covid conditions (long Covid). Evidence also suggests cumulative damage to various organs associated with repeated infection.

The economic loss associated with Covid-related work absence and chronic illness is substantial. For example, Goda and Saltas (2023) found that workers with week-long Covid-19 absences are 7 percentage points less likely to be in the labor force one year later compared to otherwise-similar workers who do not miss a week of work for health reasons. Our estimates suggest Covid-19 absences have reduced the U.S. labor force by approximately 500,000 people (0.2 percent of adults). Konishi et al found substantial productivity reductions associated with long Covid.

Long Covid also generates substantial costs for the health system. Rafferty et al give estimates for Canada ranging from $CAD 8-50 billion in annual costs

(Source: Wall Street Journal)

As is now well understood, Covid-19 is an airborne virus. Transmission risk depends on primarily on time spent in environments with high virus loads. However, workplace health and safety policy has not adjusted significantly from the initial phase of the pandemic in which it was assumed that transmission was primarily via droplets. Posters giving advice based on this assumption are still present in many workplaces and other locations.

In the absence of appropriate measures to reduce the risk of Covid-19 transmission, employers are in breach of their legal obligation to maintain a safe working environment. With the abandonment of mask and vaccination requirements, improved air quality is the only practical option for reducing workplace transmission.

The formulation of appropriate ventilation standards is a complex issue, depending on the number of people occupying a given space, the prevalence of Covid-19 among them, and whether people are coming and going. The simplest measures relate to concentrations of CO2 in the indoor atmosphere.

Standards for CO2 concentrations developed prior to the Covid-19 pandemic typically suggested a threshold of 1000ppm. However, the increased danger associated with airborne Covid implies the desirability of a lower threshold.

The Association of Consulting Architects states “Outside air is 400–415 parts per million (ppm) CO2 and a well-ventilated indoor environment will be less than 800 ppm with best practice being around 600 ppm”.

Similarly, Wang et al, responding to evidence of airborne transmission, suggest a range of 700ppm to 800 ppm

In summary, continued endemic transmission of Covid-19 represents a serious threat to productivity in Australia. A sustained policy effort to improve ventilation in workplaces and other public buildings is one of the few remaining policy responses available to mitigate this threat.

John Quiggin's Blog

- John Quiggin's profile

- 19 followers