Hugh Thomson's Blog

January 20, 2025

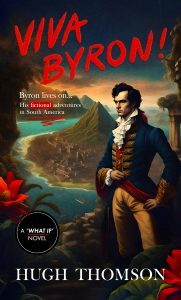

Viva Byron! published in both hardback and e-book

What would have happened if the poet Lord Byron had not died an early death in Greece?

But instead had lived – and then some – by doing what his letters show he always wanted to do: escape to South America with the great last love of his life, Countess Teresa Guiccioli, and help Simon Bolivar liberate it from the Spanish.

This great sweep of a novel imagines just that and takes the poet and his lover into a New World of the Americas where nothing is ever quite as they expect.

‘Bold, bewitching and a touch dangerous – like Lord Byron himself’ Benedict Allen

‘Hugh Thomson is a mesmerising storyteller’ Sara Wheeler

‘Literally fabulous! Unmissable…’ Joanna Lumley

So if anyone’s wondered what I’ve been doing during the extended radio silence it’s because I have determinedly not been doing any other activities other than getting this novel finished!

Which has involved travelling to Colombia to research it and the usual amount of concentrated work…

But I’m very pleased with the result and I hope that all my readers feel it’s been worth the wait.

The Kindle ebook version is available from Amazon.

The hardback versions is also available from Amazon and all good booksellers from January 2025.

June 19, 2024

My first novel – Viva Byron!

What would have happened if the poet Lord Byron had not died an early death in Greece?

But instead had lived – and then some – by doing what his letters show he always wanted to do.

Escape to South America with the great last love of his life, Countess Teresa Guiccioli, and help Simon Bolivar liberate it from the Spanish.

This great sweep of a novel imagines just that and takes the poet and his lover into a New World of the Americas where nothing is ever quite as they expect.

‘Bold, bewitching and a touch dangerous – like Lord Byron himself’ Benedict Allen

‘Hugh Thomson is a mesmerising storyteller’ Sara Wheeler

So if anyone’s wondered what I’ve been doing during the extended radio silence it’s because I have determinedly not been doing any other activities other than getting this novel finished!

Which has involved travelling to Colombia to research it and the usual amount of concentrated work…

But I’m very pleased with the result and I hope that all my readers feel it’s been worth the wait.

The ebook version is already available from Amazon.

While paperback and hardback versions will be available soon.

December 31, 2021

Best of 2021 – Movies, Music, Theatre, TV and Books

2021 a year when we all certainly needed some uplift –

My best movie by some way was Jane Campion’s The Power Of The Dog which shows her absolutely at the top of her game. I’ve always liked her work and thought her film on Keats, Bright Star, criminally underrated. It received no nominations at the time. Let’s hope she gets plenty for this.

Benedict Cumberbatch is at a career-best and superb performances by everybody else as well, including the Montana landscape and the cinematography. It also defies narrative expectations as the best drama should.

.

I also loved the energy of both Everybody’s Talking About Jamie and The Green Knight, very different British films – with the caveat that The Green Knight, despite an engaging performance by Dev Patel, has got huge narrative holes in it that could and should have been resolved.

Munich: The Edge Of War gets a sidebar prize for having the best Hitler I’ve seen; House Of Gucci for having the most enjoyable, over the top operatic acting, though far too long so you might want to build in your own interval; The Last Duel for having the best, uh, duel.

The last couple of years have seen the best feature documentaries being largely agitprop ones – like The Great Hack which blew the lid on Facebook so impressively – but the finest for me this year have been musical.

The Summer Of Soul was not just a labour of love – archived from ‘the black Woodstock’ festival of 1969 and fittingly subtitled ‘when the revolution was not televised’, as it is far less well-known – but made with a rigour lacking from most music documentaries. Worth it not just for the vibe but for the great Nina Simone’s upfront songs telling truth to power.

[image error]It makes a good pairing with the contemporary Get Back, Peter Jackson’s epic telling of The Beatles recording Let It Be, which has the leisurely pace almost of viewing rushes and is all the better for it – particularly as he doesn’t wheel on contemporary commentators to judge their legacy, in the usual lazy way of ‘white wine television’ documentaries on music. We are there in the room with them, and Billy Preston who drops in to add some unbelievably good improvised keyboards (on his day off from playing with Lulu!)

Get the sense there’s been a lot of good new music this year as artists retreated to the recording studio – slightly unexpected hits for me were Chrissie Hynde’s versions of Dylan on Standing In The Doorway and First Aid Kit likewise covering Leonard Cohen on Who By Fire.

Pharaoh Sanders is still, in his 80s, playing some wonderful and meditative jazz on Floating Points with the LSO. I listened with great pleasure to the remixes of John Lennon’s songs produced by Yoko and their son Sean, Gimme Some Truth. If only he were still around to address contemporary powermongers.

Yes I realise none of that is terribly contemporary – for which turn to St Vincent’s Daddy’s Home, The Weather Station (Ignorance) and Villagers (Fever Dreams), all of whom produced some of their best and most interesting work, with the common denominator that it was more soulful than their previous output. Maybe Billy Preston was in the room – or it was a time to be less cerebral and more emotional. And for something fun and silly, try Wet Leg’s ‘Chaise Longue’.

Best things on television were The White Lotus and Succession, both wicked and witty about the wealthy; the BBC had yet another disappointing year, although they did better on Radio 4, which is having a good moment.

In theatre, The Dante Project, which is currently streaming on the Royal Opera House website, brought together brilliantly diverse talents like Wayne McGregor, Thomas Adès and Tacita Dean and the final moving performance by veteran dancer Edward Watson as Dante himself. I ‘saw’ it on opening night, albeit from some last tickets high in the gods with obstructed vision, so grateful for a chance to see it properly – a triumph, given the potential pitfalls.

In theatre, The Dante Project, which is currently streaming on the Royal Opera House website, brought together brilliantly diverse talents like Wayne McGregor, Thomas Adès and Tacita Dean and the final moving performance by veteran dancer Edward Watson as Dante himself. I ‘saw’ it on opening night, albeit from some last tickets high in the gods with obstructed vision, so grateful for a chance to see it properly – a triumph, given the potential pitfalls.

Although it would have greatly helped if they had used the opera subtitling equipment to prompt the audience a little bit more about what was happening – an arrow in their quiver the ROH are surprisingly unwilling to use, given that it was hard to follow even for those who know The Inferno well.

For books, this was my round-up for the Spectator:

Francis Pryor is always good value. In Scenes From Prehistoric Life, he cherry-picks the most interesting recent discoveries about Britain’s past before the Romans and leaves out the dull bits for those academic surveys which give archaeology such a bad name.

For more recent history, Simon Jenkins’ 100 Best Cathedrals in Europe is impressive – having compiled lists of England’s best churches, houses and indeed views, it was inevitable that our finest contemporary gazetteer would move on to the ‘ships of heaven’. While he awards points more on the basis of architecture than atmosphere or location – both Ely and Palma get short-changed as a result – it is in the nature of such books to prompt debate.

And in the myriad of often plodding nature writing, one book stood out as superb – Charles Foster’s study of the swift, forever on the wing, in The Screaming Sky. Concise and beautifully written, it has a certain obsessive quality which is attractive and matches its subject.

That said, the best book I read all year was an old one, as often: Boswell’s Presumptuous Task by Adam Sisman which I missed when it first came out, as it followed hard upon another biography. It helped that I read it when in Skye, as the impetus for his biography of Johnson really followed on from their journey to that area of Scotland.

Looking forward to much more travelling when I can in this next year. And reading books in a Colombian hammock.

Best wishes for 2022!

November 13, 2021

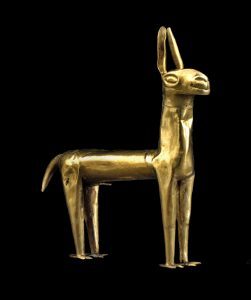

The new Peru Show at the British Museum is a Triumph. But…

A big new show about Peru has just opened at the British Museum to showcase the almost four millennia of Peruvian civilisation that preceded the destructive arrival of the Spanish.

A big new show about Peru has just opened at the British Museum to showcase the almost four millennia of Peruvian civilisation that preceded the destructive arrival of the Spanish.

It’s the first at the museum since almost the Second World War, so quite a moment to have a look at the Incas and their predecessors.

I’m pleased to report that thanks to energetic and intelligent curatorship from Jago Cooper (known to TV audiences for his work on presenting Latin American archaeology) and Cecilia Pardo, this is a triumphant success.

That said, the curators have their work cut out. Although using some of the central main space in the British Museum, it’s a smaller show than others have been, so needs to be concentrated.

And I know only too well from my Cochineal Red book – being sold alongside the exhibition – the challenges already involved in trying to present the huge span of Peruvian prehistory to an audience who may be unfamiliar with the route map of the rise and fall of its civilisations.

I like the way the curators have pitched this. It does not take the Ladybird ‘Peru is a country a long way away’ approach of some recent, painfully patronising shows. Item descriptions are precise and sophisticated. Nor is it painfully woke – although the attempt to suggest that Nasca women were being empowered towards the end of that civilisation because they were sometimes depicted underneath their men in the missionary position is perhaps an argument too far.

And while on gender representation, they have shied away from the more erotic of Moche ceramics (displayed in an adults-only gallery at one Lima Museum) in favour of a concentration on Moche sacrificial practices which while also good box office reminded me of Angela Carter’s line about one of her films – that she would have preferred ‘more sex and less violence’.

tunic stitched with hummingbird feathers

Still, some fabulous items have been cherrypicked: a tunic stitched with hummingbird feathers of the sort that Atahualpa may have worn; a necklace studded with gems made from conch shells (the ‘first contact’ the Spanish made with the Incas was when they encountered a boat looking for such valued shells in the Pacific); a pestle and mortar of the sort the Chavín shamen used to grind their hallucinogenic snuff, with jaguar motifs.

I particularly liked the witty inclusion of items like the Moche ceramic representation of a weaver holding up a cloth for inspection, as if to get it passed for approval. Most unusual of all are some wooden figures showing naked prisoners about to be sacrificed in the Moche style, which were recovered for the British Museum in the 19th century from a heap of guano, when the guano was being mined for fertiliser. The guano had preserved the wood in a way few other substances would.

The show draws on the recent triumphs of curatorship in Peru where museums like MALI have mounted some fabulous shows in Lima.

But while some objects have come from Peru, around 60% of the exhibits come from the basements of the British Museum and herein does lie a question (one I have asked before, ten years ago, to no great effect). Which is why the British Museum does not have a permanent gallery devoted to South America in the same way it does to Central America, North America and indeed just about every other continent?

But while some objects have come from Peru, around 60% of the exhibits come from the basements of the British Museum and herein does lie a question (one I have asked before, ten years ago, to no great effect). Which is why the British Museum does not have a permanent gallery devoted to South America in the same way it does to Central America, North America and indeed just about every other continent?

Part of the answers is historical and administrative – many of the South American holdings were displayed in the old Museum of Mankind by Burlington Arcade and when that was dissolved, did not find a home. But let’s hope that this fabulous new exhibition will prompt a rethink at the highest echelons in the British Museum and a more dedicated and permanent display may be forthcoming.

Such a wealth of rich artefacts certainly deserves one and would bolster the museum’s claim to be a genuine museum of the world, not just of those areas where Britain held colonial interests.

.

The Exhibition runs until February 2022

.

.

wooden figures showing naked prisoners, which had been preserved in guano for over 1000 years

[image error]A Moche prisoner awaiting sacrifice

[image error]A weaver holding up a cloth for inspection

September 2, 2021

The Upsetter – Lee Perry remembered on a rare meeting in Kingston

(c) Hugh Thomson 1994. The photograph I took of Lee as he sang to me in the burnt out husk of the Black Ark studio.

“Who am I? I’m the Mystic Warrior. Because I am what I am, and I am he that I am. I am a technological man, I am not a reggae star, I am a technological star. I am [with an intense look past my shoulder] the Upsetter”.

When Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry granted me a rare interview on his first visit to Kingston in years, I always knew it would throw up surprises. Here, after all, was a man who had created some of the greatest and wildest reggae songs of all time and was considered eccentric to the point of insanity. A man who planted the records he made in his garden and watered them. A man who wore compact discs glued to his baseball cap and mirrors on his trainers so that he could reflect light back over walls to ‘own them’.

Lee had now chosen to live in Switzerland, and rarely, if ever, revisit Jamaica. This last fact was perhaps the most bizarre. Apart from the intriguing thought of quite what his Swiss hosts made of him, or he of them, he had married a Swiss wife some thirty years younger: an eminently sensible woman called Mireille who seemed in a state of mild shock throughout Lee’s return to Kingston after so many years.

For our first meeting, Lee wore a child’s Mickey Mouse stretch lycra trousers. My first thought was that to arrive in Kingston and spend time with Lee Perry was like stepping off a bus in Memphis and bumping into BB King. My next was that Lee was unusually small.

He only came up to my shoulder – and I’m not tall. So his intense creative aura radiated even more brightly, helped by those reflecting CDs on his baseball hat. He also never quite met anybody’s eyes, but looked over their shoulder, unnervingly, as if addressing an alien presence.

He had agreed that I could spend a week with him to give me the true story of his life and career, which he felt had been much maligned. It was by no stretch of the imagination a conventional conversation or interview. Because the whole time I spent with him traipsing around the back streets of Kingston to his old haunts, Lee never stopped singing at me in Jamaican patois. Often at the top of his voice. He loved an unexpected rhyme, like ‘Johnny Rotten / is not Joseph Cotten.’

“Slow down the music! If you don’t stop on and re-wind then you go far into an explosion so we take it back to slow march and then we incarnate it and reincarnate it to where the children of today wish it and want it. I am a servant of the children.”

Given that much of the week was also spent sampling Kingston’s finest homegrown, the whole experience took on a hallucinatory quality: Lee singing at me non-stop with his beatbox through the backstreets of the city, where it was rare not to hear gunshots at some stage in the proceedings; Rasta rude boys would come up to Lee and shout in his face when he would completely ignore them.

After a while, and when he had come to trust me – or just got used to me being around – Lee took me to the burnt-out husk of The Black Ark studio, in the back-garden of his old family house. This was a legendary place where from 1973 to 1983 he recorded classic albums like Heart of the Congos, War Ina Babylon and his own innovative dub classics. When we reached the studio, which Lee had not seen for some years, he wandered around the ruins as if lost until he reached his old producer’s desk with wires and burnt metal protruding from it.

Then he switched on the small Yamaha synthesiser he always carried and started singing again. He continued singing as he wandered round lighting small fires with newspapers. This was worrying. I knew he had already burned down the studio once before, in 1983 out of frustration at what he saw, with justification, as the inequities and frustrations of the Jamaican record business. Then he had gone into exile from Kingston.

Our interview of sorts continued. I lobbed questions into the middle of Lee’s singing and chanting to the Yamaha. We were alone in the blackened carcass of the old studio, in almost total darkness except for the small flames he had lit. This is where he had created some of his most extreme sounds in the seventies, punched out of a four-track with a bass that could melt a needle into the red and over-laid with sampled sounds from his TV or the bath.

I stood – as there were no chairs and the burnt out concrete looked uninviting – in the middle of the musicians’ area while Lee addressed me from the producer’s booth, which was positioned overhead, presumably so he could dominate the musical action. The roof behind him had long fallen in, so he was silhouetted by the backlight as he spoke for hour after hour of his troubles.

Some coherent patterns began to emerge. Lee disliked being pigeon-holed as ‘a reggae producer’, for he saw Jamaican reggae as parochial and himself as working best with artists from elsewhere. He was proud that he had worked with The Beastie Boys.

He also revealed a deep ambivalence about the Wailers, who he claimed had stolen the principles of his early work from him. ‘I and I made the music. All the music.’ That he had been a mentor to Marley in the early days before Black Ark, no one disputed. To many – like me – ‘Crazy Baldhead’ and the tracks before the Wailers went to Island and Chris Blackwell (‘a vampire’ according to Lee) are some of their finest.

He revealed a real love for techno, which he saw as derived from ska; and also an affection for the days of ‘the punky reggae party’ (and for the actual song which he recorded with Marley), even if he was hazy about actual details. It proved impossible to shake him from the conviction that Johnny Rotten was in The Clash. Indeed, over my many days with Lee, I came to realise that the recording switch inside his head was always set to output rather than input. He was not one of the world’s listeners.

One of the first things Lee had done when I met him was to open up his leather suitcase to show me the most important possessions he always carried around: pressings of his early records and a purple-caped Action Man, together with several changes of costume for it.

Now he started to take these out and line them along the graffitied walls of the Black Ark to ‘reclaim my music’, along with seven carefully arranged piles of stones. He positioned the Action Man on top of one of the piles of stones. His adult son, who still lived in the house, watched on, but Lee refused to talk to him and Mireille ended up trying to console the man, who not seen his father for many years.

Lee had made it clear over our many hours of conversation that he cared far more about music than people. He came up very close to me and looked at my ear.

‘So ya see, the drum represents the heart beat. The bass is the cut, the lion that flies, walking bass, talking bass come from here [he circled his head with his hand], that’s the brain. Boom, boom, is from here, the heart.’ And he clutched it.

I noticed that for the first time in hours he had stopped singing and gone quiet, so I took the opportunity to slip in a straight question.

“Lee, what do you make of Switzerland?”

He gave me a glare.

“I hate it.”

His eyes focused as if seeing me for the first time after the week we had spent together.

“And who are you?”

—————————————————

May 27, 2021

Nero – From Zero to Hero

Nero – one of the few statues to survive that didn’t get remodelled after his fall and disgrace – showing his fringed hairstyle that was even more influential than the Beatles

Another week, another fabulous British Museum show – they have been queueing up like buses during lockdown to arrive all at once.

There are similarities between the Nero show and the Becket show which they also asked me to review ahead of its opening.

Both deal with the rewriting of history. In Nero’s case, the argument cogently expressed by the curators goes, the history was written by his senatorial opponents, so blackened his image.

Nero did not fiddle while Rome burned – indeed helped rebuild it – and was as popular with the common people for his military and civic achievements as he was unpopular with the senators for, not to put too fine a point on it, showing off a lot. They particularly couldn’t stomach his penchant for appearing on stage, the first Emperor ever to do so, so he could appeal directly to the populace; the BM makes an analogy with Twitter. Blond, good looking and with a new hairstyle, Nero’s image swept the Empire.

That said, only so much revisionism is possible. This is after all a man who killed his mother, two wives and his brother, and did indeed send Christians to the Lions, so the whitewash only goes so far.

Heavy slave gang chain found in a lake in Anglesey, between 100 BC to 78 AD.

There’s a surprising amount about Britain, as Boudicca’s rebellion took place on Nero’s watch and he decided rather than abandoning the province to rebuild cities like London and Colchester which had been completely destroyed. Some striking artefacts are displayed, including a heavy slave chain found in Anglesey (we tend to ignore the extent of slavery in prehistoric Britain, although we almost certainly exported our own slaves during the Iron Age), which would have yoked five individuals uncomfortably together.

An intelligent decision has been made to hide most of the drab conference-centre atmosphere of the Sainsbury Wing at the British Museum by leaving it in the shadows and just spotlighting the exhibits dramatically. The way in which Nero’s statue was later reshaped after his disgrace and suicide to become Vespasian, using innovative graphics, is a model of intelligent museum curatorship – and a symbol of the historical revisionism that the show reveals.

Boris Johnson just needs to hope that Dominic Cummings isn’t writing his history, or he too will be portrayed as a Nero. But then, like his hero Churchill, he probably plans to write it himself, which is always the safest bet. Nero died before he got the chance.

May 17, 2021

‘Tuesday’s Child is Full of Grace’

[image error] The Thomas Becket exhibition at the British Museum

There are two interesting revelations at this intelligently curated show marking the 900th anniversary of Thomas Becket’s birth – well it would have been the 900th anniversary last year but the show got delayed due to corona. And it’s the death that gets all the attention.

.

The first is the extent to which Thomas’s murder at the order – or suggestion – of Henry II made him a European as well as an English martyr. Many of the objects on show, the reliquaries and statues, come from countries like Norway and Sweden where he was venerated; the Christian faithful from those countries arrived in large numbers and took the pilgrimage to Canterbury not from London, as Chaucer did, but from Southampton along the south coast, a longer route which would show they were more devout. It is a journey that the British Pilgrimage Trust is trying with some success to revive to emulate the Compostela pilgrimage in Spain, so popular for those of many faiths. They are calling it The Old Way.

.

[image error]The story of Thomas Becket erased from a book at Henry VIII’s orders

Why the traditional pilgrimage to Thomas Becket’s shrine ever died out in the first place is the second great revelation of this show. For 300 years, Becket‘s was one of the great pilgrimage routes of Europe, to equal Compostela and even Rome. It is estimated that millions of pilgrims took it over the centuries.

But then came Henry VIII and the Reformation. With the brute force that he was to show in so many religious matters, Henry VIII cancelled Thomas Becket. No one was allowed to follow the pilgrimage anymore; and Becket’s own memory was defamed. Some of the most moving of the exhibits are the books from which pages have either been removed or defaced to obliterate the story of ‘this troublesome priest’.

Henry VIII had quite enough trouble on his hands from contemporary clergy like Thomas More; he didn’t want a dead one haunting his footsteps as well. Moreover Becket’s rich shrine could provide him with yet more pickings to add to those from the monasteries. He sent his men down to Canterbury in 1538 to enforce the destruction. They even destroyed Becket’s bones in their casket. The irony can not have been lost on Henry’s critics: again a king was taking it into his own hands to enforce religious observation.

.

[image error]I have a personal reason for being interested in the exhibition in that I proposed following the pilgrimage route along the South Downs as a radio series for BBC R4, with the help of Will Parsons, who has been one of the people instrumental in reviving the route. Sadly, we didn’t get to make the series, although we came close; but Will is in the process of writing a book which he will bring great charm and enthusiasm to, as with this essay. It was Will for instance who told me that Thomas Becket was born on a Tuesday which is why his life was so full of grace. See his website about wayfaring across Britain – and do also see this fine exhibition, which is an excellent way of reopening the British Museum after lockdown. Hats off to the curators for showing an entire stained glass window from Canterbury Cathedral as the stunning centrepiece.

May 6, 2021

Scotland leaving Britain – or Britain leaving Scotland?

Why the rest of Britain might want to leave Scotland

I was at dinner recently with a distinguished Fellow of All Souls who had served as a politician and is known for his incisive analysis. The conversation turned to Scotland and their forthcoming elections.

With some relish, my companion, English like me, listed the multiple reasons why the Scots should not want to leave the Union.

They would have problems with their currency. The Europeans would not want them back. Under current arrangements, they were considerable nett gainers from Westminster; independence would see their trade and incomes diminish. And would Shetland or Orkney then want to secede from Scotland? Or for that matter would some of the border constituencies reconstitute themselves, like the six counties of Northern Ireland, and want to reattach to the United Kingdom, with all the attendant tensions that have occurred in Ulster?

As much to stop him in his tracks as anything else, I asked him if he had ever turned the issue on its head. If the Scots enjoyed so many advantages by being part of the Union, what exactly did the rest of Britain gain by keeping them? If they wanted to go, and certainly if they voted to go, wouldn’t we be better off by just cutting them loose? Surely there was no logical or rational reason for wanting to keep Scotland in the Union, other than the very debatable merits of maintaining a nuclear base at Faslane?

He paused as if it was a question he had never considered. ‘Well, I suppose there is no logical or rational reason – but there is sentiment. We would feel diminished as a country. We would lose standing in the world. We would no longer be Great Britain.’

Really? And would that be such a bad thing? Given that a possible divorce is heading down the tracks at speed, perhaps it is worth examining this shibboleth in more detail.

Losing Scotland might be the best thing that’s ever happened to England (and perhaps Wales, although that’s a whole separate argument). As in any divorce, it might force us to re-evaluate and confront who we really are. That, let’s be honest, we no longer are Great Britain in anything but name. To stop pretending that we are an imperial power and one of the world’s policemen, who needs to launch aircraft cruisers when we don’t have enough planes to fill them, or patrol the Pacific as if we can possibly make any difference there whatsoever. To feel the need to be America’s bootboy in Afghanistan or Iraq.

And the rest of the world might respect us for having made that change. For looking forwards rather than constantly backwards to past glories. For being just ‘Britain’.

Instead we could concentrate on being a prosperous developed country that spends money on its healthcare and schools, like the Netherlands or Germany. A more modest country that lived within its means, but lives well, with less inequality. We still send far less of our GDP on such public spending than just about any of our neighbours. Germany had four times as many intensive care beds during the current covid crisis.

We would still have considerable critical mass. The population of Scotland is only 5.5 million compared to an overall UK population of 67.5 million. So losing Scotland would take just a little fat off the bone. Some at Westminster might argue excess fat, given both how much they pay to keep them in the Union and how roundly they get abused for their pains.

We would still have considerable critical mass. The population of Scotland is only 5.5 million compared to an overall UK population of 67.5 million. So losing Scotland would take just a little fat off the bone. Some at Westminster might argue excess fat, given both how much they pay to keep them in the Union and how roundly they get abused for their pains.

.

The left and the right of first Brexit and then the Corona crisis have already forced us to start thinking about what we really, really want in life. Maybe a divorce from Scotland will wake us up to the fact that rather than the long lingering post-imperial fantasies of grandeur, we’re just another European country.

One thing is also for sure. Nothing is messier than a contested divorce. If the Scots want to go, the rest of Britain should let them, indeed help them.

I asked my companion at dinner what would happen if the Scots gave a majority to those various parties proposing a referendum, and that Westminster then refused to give it to them. And suggested that we could easily see violence erupting on the streets of Glasgow and other Scottish cities as a result, as happens when a political voice is suppressed in a way that is seen to be unjust.

‘Well the British government would be perfectly within their rights to send in the troops,’ he said.

‘You mean just like they did in Ulster at the end of the 1960s? Which ended so well.’

‘We would be within our rights.’ And he clenched his jaw. It was a look that signalled that there would be arguments about the curtains, the second car, who got which paintings and that the whole thing would inevitably end up in court. Messily.’

‘We would be within our rights.’ And he clenched his jaw. It was a look that signalled that there would be arguments about the curtains, the second car, who got which paintings and that the whole thing would inevitably end up in court. Messily.’

As a leading divorce lawyer once told me, whatever the rights and wrongs, there comes a time just to walk away.

.

And if it’s sentiment that’s leading us – a dangerous guide at the best of times – you could argue that we would just be returning to a more natural state of England. If it was good enough for Elizabeth I, isn’t it good enough for us? The union with Scotland, precipitated by dynastic concerns and the accidents of hereditary, may just have been a temporary aberration. Both parties might be far better off going alone again. After all, we already have our own football teams. Although perhaps, given their respective records, that isn’t such a hopeful analogy.

————————

Hugh Thomson’s books include The Green Road Into The Trees: An Exploration Of England (Random House) which won the Wainwright Prize.

April 28, 2021

Neanderthal and Proud

A little while ago my brother decided to get a DNA test. So far, so good and why not. He discovered, and decided to share with his siblings, without necessarily asking us if we wanted him to, that we were all descended from a mix of the usual British suspects – a bit of Viking, Anglo-Saxon and Celt – and were predisposed to standard diseases and health risks.

A little while ago my brother decided to get a DNA test. So far, so good and why not. He discovered, and decided to share with his siblings, without necessarily asking us if we wanted him to, that we were all descended from a mix of the usual British suspects – a bit of Viking, Anglo-Saxon and Celt – and were predisposed to standard diseases and health risks.

But he kept one surprise back to the end. We had double the normal amount of Neanderthal in our genes.

For those who haven’t been keeping up, it’s now well established that we all have a small quantity of Neanderthal genes. This is the result of contact that occurred largely in the Middle East and Europe when homo sapiens arrived to find Neanderthals already there, sometime before 40,000 BC. And given that’s a fair while ago, there must been a great deal of what scientists genteelly call ‘interbreeding’ for even some of that still to survive diluted today.

But the amount my siblings and I had was way, way above average. Not to put too fine a point on it, twice as much. Which was impossible to ignore.

Reactions were, to say the least, mixed. My girlfriend declared she had suspected something of the sort for some time. My mother announced immediately that it must all come from my father’s side of the family. And it took a while to digest ourselves.

But then came help. I came across an attractive scholarly thesis which proposed that the Neanderthal element within homo sapiens was the bit that added interest – that was, so to speak, the little spike of mustard in the mix. The ‘genius gene’ that can give creative spark and has allowed us as a species sometimes to think out of the box. According to this thesis, the Neanderthal is the Mac component, with the design flair, while standard homo sapiens is boring old PC, plodding along on its mundane majority-gene tasks. Neanderthals were wilder, improvisational, free – and, the palaeontologists have shown, had bigger brains. The more you have of it within you, the more likely you are to break loose.

Most rock ‘n’ roll singers undoubtedly have a little bit of extra Neanderthal in their genome cocktail. No one can tell me that Iggy Pop is purebreed sapiens. While it goes without saying that they are likely to be better lovers (‘once you’ve had Neanderthal, there’s no going back’). The creative gene means it might not be long before the job spec for computer programmers, nuclear physicists or architects for an international commission contain the words ‘only those with high levels of Neanderthal need apply’. What’s not to like?

Most rock ‘n’ roll singers undoubtedly have a little bit of extra Neanderthal in their genome cocktail. No one can tell me that Iggy Pop is purebreed sapiens. While it goes without saying that they are likely to be better lovers (‘once you’ve had Neanderthal, there’s no going back’). The creative gene means it might not be long before the job spec for computer programmers, nuclear physicists or architects for an international commission contain the words ‘only those with high levels of Neanderthal need apply’. What’s not to like?

To say this came as a pleasurable hypothesis would be an understatement. Not only could I now frame myself as a proud Neanderthal, but as a middle-aged, middle-class white man living in the south of England, it could give me something I badly needed – some identity politics.

I realised that Neanderthals have been patronised and demonised for far too long. Some consciousness-raising is badly needed. Even President Biden, like so many of the woke, turned out to be just as prejudiced as those they seek to condemn when he made his cruel gibe that not wearing a mask was ‘Neanderthal thinking’.

I realised that Neanderthals have been patronised and demonised for far too long. Some consciousness-raising is badly needed. Even President Biden, like so many of the woke, turned out to be just as prejudiced as those they seek to condemn when he made his cruel gibe that not wearing a mask was ‘Neanderthal thinking’.

Really? I was personally offended and more than a little traumatised by his remark. Quite apart from the fact that he may have just dissed his entire political constituency (almost every American has a certain amount of Neanderthal in them – how else did Trump get elected?) Doesn’t he realise that back in the day, Neanderthals would probably have made their own masks long before homo sapiens even thought of it. Some remarkable archaeological discoveries over the last few years have shown that contrary to prejudice and expectations, Neanderthals were usually ahead of the curve: they were creating art, building boats to sail across waterways and making tools long before ‘we’ were. Sorry, ‘you’ were.

Of course some rebranding needs to be done. The word Neanderthal – from the German valley where the first remains were found – carries a pejorative overtone of some lunk-jawed caveman looking at a fire and not knowing how to light it. We need something new.

Perhaps ‘First Man’ would be good. I could imagine meeting somebody at a party and asking them politely how much ‘First Man’ they had in their makeup. Or of course ‘First Woman’ depending on how they gender-identified. Although I’ve noticed that women tend to think of being Neanderthal as purely a male preserve, even when, as with my sisters, they’ve got just as much of it in their DNA as I have.

There is also an argument that, although we may only slowly be absorbing it, the discovery we contain elements of another whole hominid species may mark a paradigm shift in our understanding of ourselves; just as when we realised that the sun did not revolve around an anthropocentric earth, or that we were as much animal as any of our Darwinian relations.

There is also an argument that, although we may only slowly be absorbing it, the discovery we contain elements of another whole hominid species may mark a paradigm shift in our understanding of ourselves; just as when we realised that the sun did not revolve around an anthropocentric earth, or that we were as much animal as any of our Darwinian relations.

I think it’s quite a liberating thought.

In his bestselling book Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari makes the counterintuitive point that the worst thing we ever did as a species was settle down and become agriculturists, with a dependence on a monotonous diet and a far more punishing work schedule than when we were hunter gatherers. The PC in us won out.

It’s about time we embraced our inner Neanderthal again and recognised that a little bit of gene diversity might be a good and creative thing. Get us out and about more. Loosen us up. Although obviously it helps if you have more of it in your genes to start with. Just saying.

—

March 25, 2021

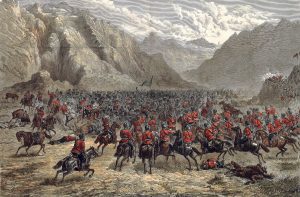

Afghanistan: No Interpreters and the Dangers of Ignorance

As the Americans prepare to leave Afghanistan and here in Britain we hold a Defence Review, have we learned the lessons of our own failures there?

As the Americans prepare to leave Afghanistan and here in Britain we hold a Defence Review, have we learned the lessons of our own failures there?

Lockdown has given me plenty of time to reflect and I’ve been thinking recently a great deal about Afghanistan – perhaps prompted by the fact that the Americans may be about to withdraw completely from that country after 20 years of largely unsuccessful occupation since the invasion.

I was in the country for a brief and intense time in 2007 when I was filming for Channel 4 Dispatches and CNN. We saw a country that had been brutalised for decades by the Russian occupation, the ensuing civil war and then the American carpet bombing to ensure that their troops met no resistance. And a country which was becoming restive as the Allies seemed increasingly unable to help them rebuild, or for that matter interested in doing so once they had been distracted by Iraq.

At the time it seemed a pivotable moment to be there and with hindsight it is even more clear that the country was at a tipping point. For the first five years after the 2001 invasion, only a handful of British troops had died in Afghanistan. This had bred complacency.

Tony Blair had then made a momentous decision not long before we started filming. To demonstrate British military efficiency and willingness, he volunteered British forces to take over in the rural south of Afghanistan, near the porous border with Pakistan where the Taliban had retreated. So in 2006, 5500 British troops were sent to the province of Helmand. Blair’s defence secretary, John Reid, made the blithe assertion that he hoped the troops would leave in three years time ‘without a shot being fired’. He was wrong on both counts: it was to be another eight years before British combat troops left Afghanistan, in 2014; and they were to suffer many casualties. Over 450 British personnel were to die in the conflict, and far more were left suffering life-changing injuries.

Tony Blair’s decision came at just the wrong time. The mood in Afghanistan was palpably changing. The American military had made no attempt to ‘nation-build’ after their remarkably quick and successful invasion. Donald Rumsfeld at the Pentagon had explicitly opposed it, hoping that the ragtag collection of Northern Alliance leaders presided over by Hamid Karzai would do the job for them– despite the fact that most were warlords and had singularly failed to do so during the earlier civil war.

The Afghan population, who at first had largely welcomed the outing of the unpopular Taliban, had begun to realise that while money was swilling into the country to aid agencies, not much was getting through to them – and that the allies simply did not understand how the complicated tribal system of councils, the jirgas and shuras, could not easily be bypassed by parachuting in governors. Nor did it help that after the Russians had destroyed much of the irrigation system as part of a scorched earth policy, the opium poppy was left as the easiest and most valuable crop to grow. And nowhere was more opium being grown than in Helmand, just to add to the problems being faced by the British.

But there was another difficulty waiting for them, along with the opium. Tony Blair had made a terrible miscalculation. If he had forgotten that the British were still more hated than any other nation in Helmand, the locals certainly hadn’t. The Battle of Maiwand had taken place nearby in 1880, which had brought to an abrupt end the last attempt the British had made to control Afghan affairs, as they had done consistently during the 19th century; and if there is one consistent factor in Afghan politics, it is that they bear a long grudge.

But there was another difficulty waiting for them, along with the opium. Tony Blair had made a terrible miscalculation. If he had forgotten that the British were still more hated than any other nation in Helmand, the locals certainly hadn’t. The Battle of Maiwand had taken place nearby in 1880, which had brought to an abrupt end the last attempt the British had made to control Afghan affairs, as they had done consistently during the 19th century; and if there is one consistent factor in Afghan politics, it is that they bear a long grudge.

Ashraf Ghani, then a finance minister and now Afghanistan’s president, was quoted at the time of the British redeployment as saying that ‘if there is one country that should not be involved in southern Afghanistan, it is the United Kingdom.’ But no one had asked him, as indeed was consistent with the Allies’ blundering approach in general.

The British arrived in Helmand badly under-resourced and ill prepared for what they were about to encounter. One reason they were so stretched is that at the same time as committing to Helmand, the British Army was trying to manage an increasingly volatile situation in Basra, in Iraq. Again they had been committed by a government with a dangerous need to try and show off British military capability, even if it wasn’t there. Resources were dangerously stretched between the two missions.

Despite that, their commanders in Helmand allowed ‘mission-creep’: they found themselves establishing vulnerable control posts in wild bandit towns like Sangin and Musa Qala, where the complexities of tribal conflicts bemused them. To say they were out of their depth would be to assume they were in a swimming pool when they were in the middle of an ocean. Not that they helped themselves: they had few political officers or interpreters, so that half the time they couldn’t work out whose face was behind the beard, Taliban or friend. The situation rapidly grew out of hand, with mounting casualties.

Rather than admitting they were overextended, the British doggedly soldiered on. Due to MOD ‘accounting errors’, there were not enough helicopters to support the increasingly far-flung control posts around Helmand – and as the Taliban gained in confidence and started using road-side bombs, not enough suitable vehicles to make the increasingly dangerous journeys overland, just as in Basra. The soft-shelled Land Rovers were dubbed ‘coffins on wheels’ by the soldiers.

While initially there had not been a strong Taliban presence in Helmand, the tribes’ desire to eject the meddling British allowed them in. The Paras who were stationed there were also a blunt instrument. They might have proudly pointed out to the Americans that they had experience in counterinsurgency from Northern Ireland (perhaps not mentioning Bloody Sunday); but understanding the complexities of Northern Irish politics was a piece of cake compared to those of the Afghan tribes, and Northern Ireland was, for better or divisive worse, home soil, with the same language spoken.

Thinking about Afghanistan now, I feel an enormous sorrow for the families of the brave British soldiers killed by this rash deployment, and for those of them who survive injured or traumatised; and also an anger at the blind stupidity of the politicians like Tony Blair who sent them there.

I also feel empathy for those Afghan civilians I met who had been so trampled by the decades of conflict: the widowed women huddled in burkas in the winter streets of Kabul, begging in the mud; the orphaned children in a remote village by the Tajik frontier, fending for themselves; at the other end of the country, a child bride on the outskirts of Herat living in a hut amongst the piles of old abandoned tanks and APC’s, showing us the legs she had burned with kerosene at 12 years old as the only way she could protest at the miseries of her own existence. There been over 45,000 civilian deaths since the invasion.

I also feel empathy for those Afghan civilians I met who had been so trampled by the decades of conflict: the widowed women huddled in burkas in the winter streets of Kabul, begging in the mud; the orphaned children in a remote village by the Tajik frontier, fending for themselves; at the other end of the country, a child bride on the outskirts of Herat living in a hut amongst the piles of old abandoned tanks and APC’s, showing us the legs she had burned with kerosene at 12 years old as the only way she could protest at the miseries of her own existence. There been over 45,000 civilian deaths since the invasion.

While the US contemplates leaving completely in May, whatever anarchy may then ensue – as it surely will – have we ourselves learned anything from Afghanistan? Given that as Andrew Marr once pointed out in an interview, no British politician has ever apologised for mistakes made there.

What led us to overcommit and then suffer casualties was a wilful determination to assert a power we no longer have; and a concomitant failure to understand the country we were dealing with. The same dangerous attitude is displayed in the current Defence Review, which wants us still to be a global player: to increase our nuclear warhead capacity by 40%; to be able to intervene even though we will have fewer troops and resources to do so. There is much loose talk of ‘new technology’, just as there was when replacing the Land Rovers; but as Michael Mullen, a former head of the US military, pointed out when asked about the forthcoming British troop cuts, it’s hard to use an app when you’re in the middle of a battlefield. What matters is the practical application of force on the ground to achieve measured objectives.

If we jump feet first into another conflict again, personally I would trust Boris “let’s wing it” Johnson even less than Tony Blair. Just what are we all trying to prove, particularly when there are schools, hospitals and nurses all needing money that would otherwise be spent on warheads?

The lesson from Afghanistan is that we should not try to punch above our weight. The British Empire ended over 50 years ago. Isn’t it time we stopped trying to be one of the world’s policemen? When we could do so much better by being one of the world’s interpreters and facilitators.

———————————————–

A modified version of this piece was published by the Spectator

Further reading

Christina Lamb’s excellent two books: The Sewing Circles Of Herat and Farewell Kabul.

Sarah Chayes, The Punishment Of Virtue. Sarah Chayes spent a decade from 2001 to 2011 in the Taliban heartland of Kandahar. As I reviewed it for the Independent; ‘This passionate and engaged dispatch from the field is in the best tradition of grass-roots reporting; it is, quite simply, the best book on Afghanistan since the invasion.’

Jack Fairweather, The Good War. Fairweather is a fine writer whose later The Volunteer rightly won the Costa Book Of The Year Award – this is one of the best, most straightforward accounts of the conflict up to 2014. A Million Bullets by James Ferguson is another, earlier one.

William Dalrymple, Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan, a brilliantly written account of the first 19th century British campaign in Afghanistan and its dramatic failure. What a shame it was only published in 2013, just as the British were leaving Afghanistan this time around, as it might have helped focus minds before they arrived.

James Meek, ‘Worse than a Defeat’, LRB : Wide-ranging review which covers Jack Fairweather’s book above, but extends wider.

Andrew Mackay’s ‘Afghanistan’s: The Lessons of War’, broadcast on BBC R4. As a former major general in Afghanistan, Andrew Mackay gives an interesting analysis which, while diplomatic as one might expect, also clearly recognises the problems the British Army encountered there.

And for completists, nothing beats reading the sobering House of Commons Review of the Afghan campaign. Like: ‘We subsequently asked other Ministry of Defence (MoD) witnesses on 10 November 2010 about the deployment to Helmand in 2006 including the size of the deployment and the intelligence on which it was based. The answers we received were far from satisfactory: we were left with the impression that the MoD intended to minimise what we were told about how decisions were made to deploy to Helmand in 2006 and then to expand the deployment.’