Geoffrey Notkin's Blog - Posts Tagged "rock-star"

"Time Is An Illusion," Excerpt from Chapter Twenty of "Rock Star: Adventures of a Meteorite Man"

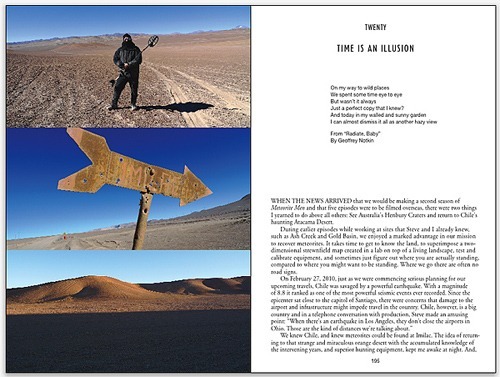

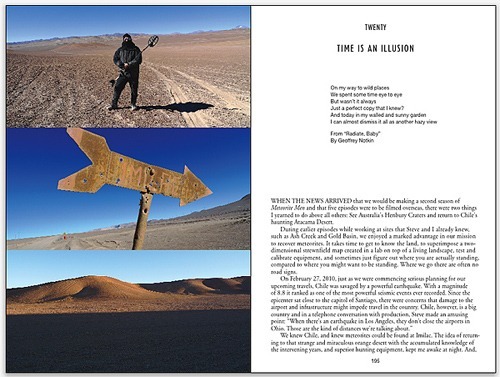

When the news arrived that we would be making a second season of Meteorite Men and that five episodes were to be filmed overseas, there were two things I yearned to do above all others: See Australia’s Henbury Craters and return to Chile’s haunting Atacama Desert.

During earlier episodes while working at sites that Steve and I already knew, such as Ash Creek and Gold Basin, we enjoyed a marked advantage in our mission to recover meteorites. It takes time to get to know the land, to superimpose a two-dimensional strewnfield map created in a lab on top of a living landscape, test and calibrate equipment, and sometimes just figure out where you are actually standing, compared to where you might want to be standing. Where we go there are often no road signs.

On February 27, 2010, just as we were commencing serious planning for our

upcoming travels, Chile was savaged by a powerful earthquake. With a magnitude

of 8.8 it ranked as one of the most powerful seismic events ever recorded. Since the epicenter sat close to the capitol of Santiago, there were concerns that damage to the airport and infrastructure might impede travel in the country. Chile, however, is a big country and in a telephone conversation with production, Steve made an amusing point: “When there’s an earthquake in Los Angeles, they don’t close the airports in Ohio. Those are the kind of distances we’re talking about.”

We knew Chile, and knew meteorites could be found at Imilac. The idea of returning to that strange and miraculous orange desert with the accumulated knowledge of the intervening years, and superior hunting equipment, kept me awake at night. And, perhaps, I would at last get to see Monturaqui Crater. I lobbied hard for Chile and, in the end, we were given the green light.

How Chile had changed, and yet, remained the same. Antofagasta, hardly

recognizable as the rundown outpost where we took shelter after our breakdown at La Pampa in 1997, now boasted modern hotels, rental car offices, chic restaurants, and a larger airport. We arrived in early August—which is winter in the Southern Hemisphere—and a bracing wind blew in from the frigid South Pacific. Seabirds called out as we drove along the rocky shore, and I felt as if I had slipped back into a happy and familiar dream.

Steve and I had aged since we said goodbye to Imilac; but when our trucks galloped up that long ochre slope once again and parked beside the old campsite, nothing had changed, nothing at all. The impossible sky remained the same enamel blue, and the hills to our west still slumped against the horizon like giant sleeping camels, far off in the clear and precise mountain air. I walked to the exact spot where I pitched my tent and tied it to our haggard Toyota in the ferocious wind, back when I was still thirty-six years old. I recalled exactly how my sun shade had been whipped away by that sudden gust—just over there, it was—and stared at my own footprints preserved, evidently forever, in the uncaring and impassive Atacama sand. While thirteen long and memory-filled years elapsed in our temporary and measurable lives, the hands of the great meteorite clock that remains hidden from the quotidian world of humans had moved forward, imperceptibly, about one minute.

The Imilac strewnfield is situated so far from civilization, camping with the entire crew became our only option. In addition to Steve and myself, our convoy consisted of senior producer Sonya Bourn, our director, two cameramen, two sound men, a camera tech, a mountaineering survival expert, a medic, a chef, and two drivers. In all of our travels it was one of only two times when we had a cook on staff, and I cannot state too strongly how reassuring it felt to have a real cooked dinner waiting for us after twelve hours of hiking, digging, and filming at 11,000 feet.

A huddle of abandoned and roofless miners’ cabins made of rough stones was

selected for base camp. We rushed to get tents set up before the blackest of nights descended upon us and by 9 p.m. the temperature had plummeted to 24 degrees below freezing. Standing beside a roaring fire on the stone floor of an ancient cottage, in the middle of the immense Atacama Desert, I looked at the huddled figures around me and had an epiphany: all of these people were here, and all of this time, effort, and money had been expended because of a dream I had as a child. I suddenly felt an intense camaraderie for this odd band of talented professionals, most of whom had traveled all the way from California because they believed in what Steve and I were doing.

We found plenty of meteorites, but most of them were small. Large meteorites, lying starkly on the surface, had been picked up long ago, but space gems still lay in the dusty earth and they looked exactly like the ones we had found in 1997. Again, I felt as if nothing had changed. I could have always been at Imilac, and the passage of time nothing but an illusion.

During earlier episodes while working at sites that Steve and I already knew, such as Ash Creek and Gold Basin, we enjoyed a marked advantage in our mission to recover meteorites. It takes time to get to know the land, to superimpose a two-dimensional strewnfield map created in a lab on top of a living landscape, test and calibrate equipment, and sometimes just figure out where you are actually standing, compared to where you might want to be standing. Where we go there are often no road signs.

On February 27, 2010, just as we were commencing serious planning for our

upcoming travels, Chile was savaged by a powerful earthquake. With a magnitude

of 8.8 it ranked as one of the most powerful seismic events ever recorded. Since the epicenter sat close to the capitol of Santiago, there were concerns that damage to the airport and infrastructure might impede travel in the country. Chile, however, is a big country and in a telephone conversation with production, Steve made an amusing point: “When there’s an earthquake in Los Angeles, they don’t close the airports in Ohio. Those are the kind of distances we’re talking about.”

We knew Chile, and knew meteorites could be found at Imilac. The idea of returning to that strange and miraculous orange desert with the accumulated knowledge of the intervening years, and superior hunting equipment, kept me awake at night. And, perhaps, I would at last get to see Monturaqui Crater. I lobbied hard for Chile and, in the end, we were given the green light.

How Chile had changed, and yet, remained the same. Antofagasta, hardly

recognizable as the rundown outpost where we took shelter after our breakdown at La Pampa in 1997, now boasted modern hotels, rental car offices, chic restaurants, and a larger airport. We arrived in early August—which is winter in the Southern Hemisphere—and a bracing wind blew in from the frigid South Pacific. Seabirds called out as we drove along the rocky shore, and I felt as if I had slipped back into a happy and familiar dream.

Steve and I had aged since we said goodbye to Imilac; but when our trucks galloped up that long ochre slope once again and parked beside the old campsite, nothing had changed, nothing at all. The impossible sky remained the same enamel blue, and the hills to our west still slumped against the horizon like giant sleeping camels, far off in the clear and precise mountain air. I walked to the exact spot where I pitched my tent and tied it to our haggard Toyota in the ferocious wind, back when I was still thirty-six years old. I recalled exactly how my sun shade had been whipped away by that sudden gust—just over there, it was—and stared at my own footprints preserved, evidently forever, in the uncaring and impassive Atacama sand. While thirteen long and memory-filled years elapsed in our temporary and measurable lives, the hands of the great meteorite clock that remains hidden from the quotidian world of humans had moved forward, imperceptibly, about one minute.

The Imilac strewnfield is situated so far from civilization, camping with the entire crew became our only option. In addition to Steve and myself, our convoy consisted of senior producer Sonya Bourn, our director, two cameramen, two sound men, a camera tech, a mountaineering survival expert, a medic, a chef, and two drivers. In all of our travels it was one of only two times when we had a cook on staff, and I cannot state too strongly how reassuring it felt to have a real cooked dinner waiting for us after twelve hours of hiking, digging, and filming at 11,000 feet.

A huddle of abandoned and roofless miners’ cabins made of rough stones was

selected for base camp. We rushed to get tents set up before the blackest of nights descended upon us and by 9 p.m. the temperature had plummeted to 24 degrees below freezing. Standing beside a roaring fire on the stone floor of an ancient cottage, in the middle of the immense Atacama Desert, I looked at the huddled figures around me and had an epiphany: all of these people were here, and all of this time, effort, and money had been expended because of a dream I had as a child. I suddenly felt an intense camaraderie for this odd band of talented professionals, most of whom had traveled all the way from California because they believed in what Steve and I were doing.

We found plenty of meteorites, but most of them were small. Large meteorites, lying starkly on the surface, had been picked up long ago, but space gems still lay in the dusty earth and they looked exactly like the ones we had found in 1997. Again, I felt as if nothing had changed. I could have always been at Imilac, and the passage of time nothing but an illusion.

[image error]

Published on July 26, 2012 21:02

•

Tags:

adventures-of-a-meteorite-man, geoff-notkin, geoffrey-notkin, meteorite-men, meteorites, rock-star